- Continue Shopping

- Your Cart is Empty

Streaming along...

There is a whole, fascinating science to river and stream structure, and with so many implications for understanding how these structures and mechanisms affect fish population, occurrence, behavior, and ecology, it's well worth studying for aquarium interpretation!

Leaf litter beds form in what stream ecologists call "meanders", which are stream structures that form when moving water in a stream erodes the outer banks and widens its "valley", and the inner part of the river has less energy and deposits silt- or in our instance, leaves.

Did you get that part where I mentioned that the lower-energy parts of the water courses tend to accumulate leaves and sediments and stuff?

It's logical, right? And it's also interesting, because, as we know, fishes and their food items tend to aggregate in these areas, and embracing the "theme" of a litter/botanical bed or even wood placement, in the context of a stream structure in the aquarium is kind of cool!

You could build upon, structure, and replace leaves and botanicals in this "framework"- like, indefinitely...sort of like what happens in the "meanders in streams!"

In Nature, the rain and winds also effect the depth and flow rates of many of the waters in this region, with the associated impacts mentioned above, as well as their influence on stream structures, like submerged logs, sandbars, rocks, etc.

Stuff gets redistributed constantly.

Is there an aquarium "analog" for these processes?

Sure!

We might move a few things around now and again during maintenance, or perhaps current or the fishes themselves act to redistribute and aggregate botanicals and leaves in different spots in our aquairums.

And how we structure the more "permanent" hardscape features in our tanks has a profound influence on how botanical materials can aggregate.

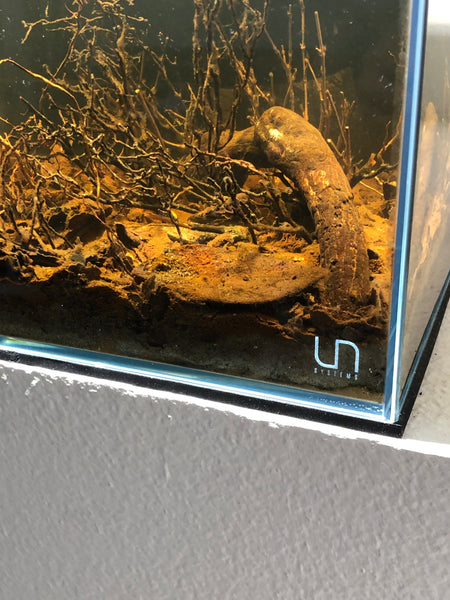

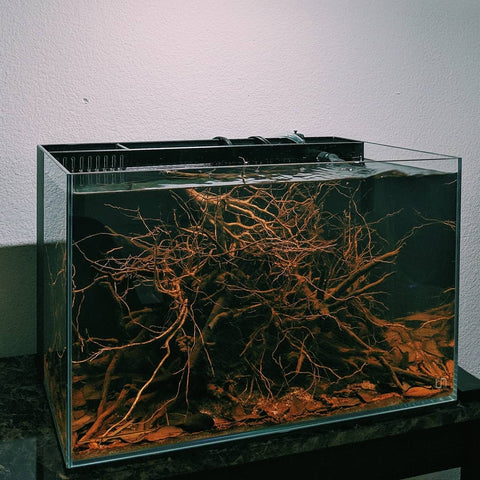

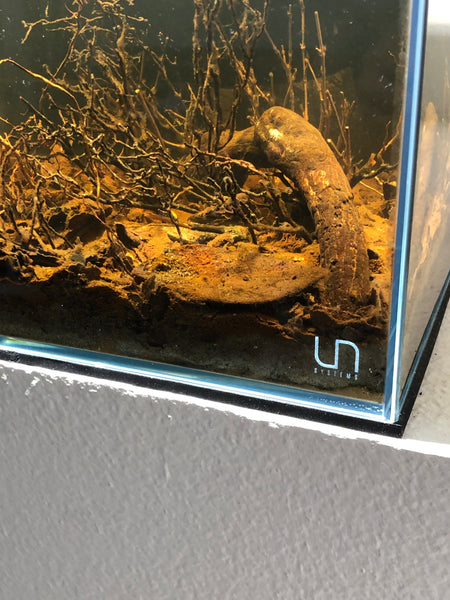

So, rather than covering the whole bottom of your tank with leaves, would it be cool to create some sort of hardscape structure- with driftwood, etc., to retain or keep these items in one place..to create a "framework" for a long-term, organized, specifically-placed litter bed.

The composition of bottom materials and the depth of the channel are always changing in response to the flow in a given stream, affecting the composition and ecology in many ways. I'll probably state this idea more than once in this piece, because it's really important:

Every stream is unique. Although there are standard structural or functional elements common to many streams, each stream is essentially a "custom response" to local ecological, topographical, meteorological, and biological factors.

Permanent streams will often have different volume and material composition (usually finely-packed sands and gravels, with lots of smooth stones) than more intermittent streams, which are the result of inundation caused by rain, etc., or even so-called "ephemeral" streams, often packed with leaves and lighter sediments, which typically occur only immediately after rain events (which means they usually don't have fish in them unless they are washed into them from more permanent watercourses).

The latter two stream types are typically more affected by leaves, botanical debris, branches, and other materials. Like the igarapes ("canoe ways") of Brazil...little channels and rivulets which come and go with the seasonal rains. And then, there's those flooded Igapo forests we obsess over.

In the overall Amazon region (you knew I was sort of headed back that way, right?), it sort of works both ways, with the rivers influencing the surrounding land...and then the land "giving" some of the materials back to the rivers...the extensive lowland areas bordering the river and its tributaries, known as varzeas (“floodplains”), are subject to annual flooding, which helps foster enrichment of the aquatic environment.

Much of them come from trees.

Yeah, trees.

The materials that comprise the tree are known in ecology as "allochthonous material"- something imported into an ecosystem from outside of it. (extra points if you can pronounce the word on the first try...) And of course, in the case of trees, this also includes includes leaves, fruits and seed pods that fall or are washed into the water along with the branches and trunks that topple into the stream.

You know, the stuff we obsess over around here!

Although many streams derive their food base from leaves and organic matter, there is a lot of other material present that contributes to its structure. Think along those lines when scheming your next aquarium. Ask yourself what factors would contribute to the bottom composition of the area you're taking inspiration from.

There seems to be a pervasive mindset within the botanical method aquarium hobby that you need to incorporate a wide variety of botanicals into every aquarium. I would like to go on record right now to state that this is simply untrue. You can use as little or as much diversity of materials as you'd like;

Nature doesn't have a "standard" for this!

It's a "guideline" which I believe vendors have placed into the collective consciousness of the hobby for reasons that are not entirely altruistic. Personally, I will only use a one or two types of botanical materials in a given aquarium. Maybe three, but that's typically it. This mindset was forged by both my aesthetic preferences and my studying of the characteristics of many of the natural habitats which we model our aquariums after.

They simply don't have an unlimited variety of materials present. Rather, the composition of the accumulated materials in most wild aquatic habitats is limited- often based upon the plants in the immediate vicinity, as well as other factors, like currents (when present) and winds. During storms, materials can be re-distributed from outside of the immediate environment, adding to the diversity of accumulation.

In general, one of the ecological roles of streams are to distribute materials throughout the greater ecosystem. Streams have interesting morphologies. It's interesting to consider the structural components of a stream, to get a better picture of how it forms and functions. What are the key components of streams?

Well, there is the top end of a stream, where its flow begins..essentially, its source. The "bottom end" of a stream is known as its "mouth." In between, the stream flows through its main course, also known as a "trunk." Streams gain their water through runoff, the combined input of water from the surface and subsurface.

Streams which flow over stony, open bottoms, free from natural obstacles like tree trunks and such, tend to develop a rich algal turf on their surfaces.

While not something a lot of hobbyists like to see in their tanks (with the exception of Mbuna guys and weirdos like me), algae-covered stones and rocks are entirely natural and appropriate for the bottom of many aquariums! (enter a tank with THAT in the next international aquascaping contest and watch the ensuing judge "freak-out" it causes! )

Grazing fishes, of course, will feed extensively on or among these algal films, and would be logical choices for a stony-bottom-themed aquarium. Like Labeo ("Sharks"), Darter characins, and barbs. When we think about the way natural fish communities are assembled in rivers and streams, it's almost always as a result of adaptations to the physical environment and food resources.

Now, not everyone wants to have algae-covered stones or a mass of decomposing leaves on the bottom of their aquarium. I totally get THAT! However, I think that considering the role that these materials play in the composition of streams and the lives of the fishes which inhabit them is important, and entirely consistent with our goal of creating the most natural, effective aquariums for the animals which we keep.

As a hobbyist, you can employ elements of these natural systems in a variety of aquariums, using any number of readily-available materials to do the job. And, let's face it; pretty much no matter how we 'scape a tank- no matter how much- or how little- thought and effort we put into it, our fishes will ultimately adapt to it.

They'll find the places they are comfortable hiding in. The places they like to forage, sleep and spawn. It doesn't matter if your 'scape consists of carefully selected roots, seed pods, rocks, plants, and driftwood, or simply a couple of clay flower pots and a few pieces of egg crate- your fishes will "make it work."

As aquarists, observing, studying, and understanding the specifics of streams is a fascinating and compelling part of the hobby, because it can give us inspiration to replicate the form and more important- the function- of them in our tanks!

Now, you're also likely aware of the fact that we're crazy about small, shallow bodies of water, right? I mean, almost every fish geek is like "genetically programmed" to find virtually any random body of water irresistible!

Especially little rivulets, pools, creeks, and the aforementioned forest streams. The kinds which have an accumulation of leaves and botanical materials on the bottom. Darker water, submerged branches- all of that stuff...

You know- the kind where you'll find fishes!

Happily, such habitats exist all over the world, leaving us no shortage of inspiring places to attempt to replicate. Like, everywhere you look!

In Africa for example, many of these little streams and pools are home to some of my fave fishes, killifish! This group of fishes is ecologically adapted to life in a variety of unusual habitats, ranging from puddles to small streams to mud holes. However, many varieties occur in those streams in the jungles of Africa.

And many of these little jungle streams are really shallow, cutting gently through accumulations of leaves and forest debris. Many are seasonal. The great killie documenter/collector, Col. Jorgen Scheel, precisely described the water conditions found in their habitat as "...rather hot, shallow, usually stagnant & probably soft & acid."

Ah-ah! We know this territory pretty well, right?

I think we do...and understanding this type of habitat has lots of implications for creating very cool biotope-inspired aquariums.

And why not make 'em for killifish?

So, yeah- we keep talking about "very shallow jungle streams." How shallow? Well, reports I've seen have stated that they're as shallow as 2 inches (5.08cm). That's really shallow. Seriously shallow! And, quite frankly, I'd call that more of a "rivulet" than a stream!

"Virtually still, with a barely perceptible current..." was one description. That kind of makes my case!

What does that mean for those of us who keep small aquariums?

Well, it gives us some inspiration, huh? Ideas for tanks that attempt to replicate and study these compelling shallow environments...

Now, I don't expect you to set up a tank with a water level that's 2 inches deep..And, although it would be pretty cool, for more of us, perhaps a 3.5"-4" (8.89-10.16cm) of depth is something that can work? Yeah. Totally doable. There are some pretty small commercial aquariums that aren't much deeper than 6"-8" (20.32cm).

We could do this with some of the very interesting South American or Asian habitats, too...Shallow tanks, deep leaf litter, and even some botanicals for good measure.

How about a long, low aquarium, like the ADA "60F", which has dimensions of 24"x12"x7" (60x30x18cm)? You would only fill this tank to a depth of around 5 inches ( 12.7cm) at the most. But you'd use a lot of leaves to cover the bottom...

Yeah, to me, one of the most compelling aquatic scenes in Nature is the sight of a stream meandering into the forest.

There is something that calls to me- beckons me to explore, to take not of its intricate details- and to replicate some of its features in an aquarium- sometimes literally, or sometimes,. just taking components that I find compelling and utilizing them.

An important consideration when contemplating such a replication in our tanks is to consider just how these little forests streams form. Typically, they are either a small tributary of a larger stream, with the path carved out by rain or erosion over time. In other situations, they may simply be the result of an overflowing tributary during the rainy season, and as the waters recede later in the year, they evolve into smaller streams meandering through vegetation.

Those little streams fascinate me.

In Brazil, they are known as igarape, derived from the native Brazilian Tupi language. This descriptor incorporates the words "ygara" (canoe) and "ape"(way, passage, or road) which literally translates into "canoe way"- a small body of water which forms a route navigable by canoes.

A literal path through the forest!

These interesting little tributaries areare shaded by trees at the margins, and often cut for many kilometers through dense rain forest. The bottoms of these tributaries- formerly forest floor- are often covered with seed pods, twigs, leaves, and other botanical materials from the vegetation above and surrounding them.

Although igapó forests are characterized by sandy acidic soils that have a low nutrient content, the tributaries that feed them are often found over a fine-grained, whitish sand, so as an aquarist, you a a lot of options for substrate!

In this world of decomposing leaves, submerged logs, twigs, and seed pods, there is a surprising diversity of life forms which call this milieu home. And each one of these organisms has managed to eke out an existence and thrive.

A lot of hobbyists not familiar with our aesthetic tastes will ask what the fascination is with throwing palm fronds and seed pods into our tanks, and I tell them that it's a direct inspiration from Nature! Sure, the look is quite different than what has been proffered as "natural" in recent years- but I'd guarantee that, if you donned a snorkel and waded into one of these habitats, you'd understand exactly what we are trying to represent in our aquariums in seconds!

Streams, rivulets...whatever they're called- they beckon us. Compel us. And challenge us to understand and interpret Nature in exciting new ways in our aquariums.

I think we're starting to see a new emergence of a more "holistic" approach to aquarium keeping...a realization that we've done amazing things so far, keeping fishes and plants in a glass or acrylic box with applied technique and superior husbandry...but that there is room to experiment and push the boundaries even further, by understanding and applying our knowledge of what happens in the real natural environment.

Think differently. Expand your horizons.

Stay curious. Stay creative. Stay brave. Stay studious...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Constantly Changing. Persistently Evolving...

I make it no secret that the botanical method aquarium is unlike almost any other approach to aquarium keeping currently practiced. Not better. Not the "coolest" (well, possibly...)- just different. To parse all of the many reasons why this approach is so different could literally take years...Oh, wait, it HAS..like 8 years, to be exact!

If you take this approach, you simply, literally- need to clear your mind of any preconceived notions that you have about what an aquarium should look like. The aesthetics are unlike anything that you've seen before in the hobby.

And, over the many years that I've been playing with botanicals, my approaches and processes have changed and evolved, based on my own experiences, and those of our community. The way I approach botanical method aquariums today is definitely a bit different than I have approached them previously.

And that's pretty cool..It's the by-product of years of playing with this stuff; modifying techniques, philosophies, and approaches based upon actual practice.

My practices are constantly changing...Persistently evolving.

Here are a few examples of the evolution of my practices and approaches over the years.

As a regular consumer of our content, you likely know of my obsession with varying substrate compositions and what I call "enhancement" of the substrate- you know, adding mixes of various materials to create different aesthetics and function.

Over the years, I've developed a healthy interest in replicating the function and form of substrates found in the wild aquatic habitats of the world. What we had to work with in years past in the hobby was simply based upon what the manufacturers had available. I felt that, although these materials are overall great, there was a lot of room for improvement- and some evolution based upon what types of materials are found in actual wild aquatic habitats.

My evolution was based upon really studying the wild habitats and asking myself how I can replicate their function in my tanks. A big chunk of this understanding came from studying how substrate materials in the wild aggregate and accumulate; where they come from, and what they do for the overall aquatic ecosystem.

I'm fascinated with this stuff partly because substrates and the materials which comprise them are so intimately tied to the overall ecology of the aquatic environments in which they are found. Terrestrial materials, like soils, leaves, and bits of decomposing botanical materials become an important component of the substrate, and add to the biological function and diversity.

Now, there is a whole science around aquatic substrates and their morphology, formation, and accumulation- I don't pretend to know an iota about it other than skimming Marine biology/hydrology books and papers from time to time. However, merely exploring the information available on the tropical aquatic habitats we love so much- even just looking long and hard at some good underwater pics of them- can give us some good ideas!

How do these materials find their way into aquatic ecosystems?

In some areas- particularly streams which run through rain forests and such, the substrates are often simply a soil of some sort. A finer, darker-colored sediment or soil is not uncommon. These materials can profoundly influence water chemistry, based on the ionic, mineral, and physical concentrations of materials that are dissolved into the water. And it varies based on water velocities and such.

Meandering lowland rivers maintain their sediment loads by continually re-suspending and depositing materials within their channels- a key point when we consider how these materials arrive-and stay- in the aquatic ecosystems.

Forest floors...Fascinating ecosystems in their own right, yet even more compelling when they're flooded.

And what accumulates on dry forest floors?

Branches, stems, and other materials from trees and shrubs. When the waters return, these formerly terrestrial materials become an integral part of the (now) aquatic environment. This is a really, really important thing to think of when we aquascape or contemplate who we will use botanical materials like the aforementioned stems and branches. They impact both function and aesthetics of an aquarium...Yes, what we call "functional aesthetics" rears its head again!

There is no real rhyme or reason as to why stuff orients itself the way it does. I mean, branches fall off the trees, a process initiated by either rain or wind, and just land "wherever." Which means that we as hobbyists would be perfectly okay just sort of tossing materials in and walking away! Now, I know this is actually aquascaping heresy- Not one serious 'scaper would ever do that...right?

I'm not so sure why they wouldn't. Look at Nature...

I mean, what's wrong with sort of randomly scattering stems, twigs, and branches in your aquascape? It's a near-perfect replication of what happens in Nature. Now, I realize that a glass or acrylic box of water is NOT nature, and there are things like "scale" and "ratio" and all of that "gobbldeygook" that hardcore 'scaping snobs will hit you over the head with...

But Nature doesn't give a shit about some competition aquascaper's "rules"- and Nature is pretty damn inspiring, right? There is a beauty in the brutal reality of randomness. I mean, sure, the position of stones in an "Iwagumi" is beautiful...but it's hardly what I'd describe as "natural."

We talk a lot about "microhabitats" in Nature; little areas of tropical habitats where unique physical, environmental and biological characteristics converge based on a set of factors found in the locale. Factors which determine not only how they look, but how they function, as well.

The complexity and additional "microhabitats" they create are compelling and interesting. And they are very useful for shelltering baby fishes, breeding Apistogramma, Poecilocharax, catfishes, Dicosssus, an other small, shy fishes which are common in these habitats.

Small root bundles and twigs are not traditionally items you can find at the local fish store or online. I mean, youcan, but there hasn't been a huge amount of demand for them in the aquascaping world lately...although my 'scape scene contacts tell me that twigs are becoming more and more popular with serious aquascapers for "detailed work"...so this bodes well for those of us with less artistic, more functional intentions!

Except we don't glue shit together.

When I see aquascapers glue wood together, it makes me want to vomit. I know, I'm an asshole for feeling that way, but it's incredibly lame IMHO. Just fit the shit together with leverage and gravity, like your grandparents did, or keep looking for that perfect piece. Seriously! You don't need to glue to make wood look "cool."

You're not a reefer gluing coral frags to rock. There is no "need" to do this.

Relax and just put it together as best as Nature will allow.

Okay, micro rant over!

Let's get back to discussing natural materials and how we've come to include them in our tanks just a bit more...

Like, roots.

In flooded forests, roots are generally found in the very top layers of the soil, where the most minerals are. In fact, in some areas, studies indicated that as much as 99% of the root mass in these habitats was in the top 20cm of substrate! Low nutrient availability in the Amazonian forests is partially the reason for this. And since much of that root mass becomes submerged during seasonal inundation, it becomes obvious that this is a unique habitat.

So, ecological reasons aside, what are some things we as hobbyists can take away from this?

We can embrace the fact that most of these finer materials will function in our aquairums as they do in Nature, sequestering sediments, retaining substrate, and recruiting epiphytic materials which fishes will forage, hide, and spawn among.

Functional aesthetics.

And let's talk about preparation a bit.

I'm at a phase in my aquarium "career" with regards to botanicals in which I feel it is less and less necessary to worry about extensively preparing my botanical materials for use in my tanks. In essence, my main preparation "technique" is to rinse the items briefly in freshwater, followed by a boil until they are saturated and stay submerged.

It's less and less about "cleaning them" and more and more about getting them to stay down in my aquairums. And to be perfectly honest, if the materials would actually sink immediately and stay down, I think my "preparation" would simply consist of a good rinse!

What's the reason for this "evolution" of my preparation technique? Well, part of it is because I've started to realize that virtually every botanical item which I use in my work is essentially "clean"- that is, not polluted or otherwise contaminated. Generally, most of the items I use may simply have some "dirt" on their surfaces. I typically will not use botanical items which have bird droppings, insect eggs, or other obvious contaminants present.

The reality is that, in over 20 years of playing with botanicals, I simply cannot attribute a single fish death to the use of improperly prepared botanical materials!

It's really more about the sourcing, to me.

Naturally collected materials, air or sun-dried over time are just not an issue. However, when you obtain materials from unvetted sources, you cannot be sure what her original intended use was. For years, the "hack" I've seen was hobbyists purchasing dried botanical materials from craft stores...And these are the people I've seen the most issues with.

The problem is that materials intended to be used in craft projects are typically chemically preserved or treated with varnishes or other materials...and these are simply deadly to aquatic life.

Feel free to experiment with all sorts of carefully collected natural materials, but I would simply avoid purchasing them from sources which you cannot thoroughly vet. The price of such "hacks" may be the deaths of your fishes.

Another reason I'm less "anal" about preparation of my botanicals and wood and such is that these materials contain a lot of organic materials which are likely "catalysts" for ecological processes. I know, that's vague and oddly unscientific, but it makes sense, when you think about it.

"Organics" are simply incorporated into the aqueous environment, and help foster the growth of a variety of organisms, from fungi to bacterial biofilms and more. IMHO, they are helpful to create an underwater ecology in your aquirium. It's no longer a concern of mine that botanicals being added to my aquairums need to be essentially "sterile."

Ecology is the primary motivation for me when it comes to adding botanicals to my tanks- specifically, helping to foster an underwater ecology which will provide the inhabitants with supplemental food and nutrient processing. So, trying to keep things impeccably clean when setting up an ecology first, botanical method aquarium is downright counterproductive, IMHO.

And I have a hunch that a lot of our fear of introducing extraneous "stuff" into our tanks via botanicals was as a result of my excessive paranoia back in 2015, in our earliest days- when I was very concerned about some hobbyist simply dumping a bunch of our fresh botanicals into his/her tank and ending up with...well, what?

A tank with a little bid of turbidity? Darkly tinted water? Some fungal and biofilm-encrusted seed pods and leaves? Detritus from their tissues?

All things that we've come to not only accept, but to expect and to even celebrate as a normal part of our practice. I mean, man, there is literally an explosion of hashtags used on instagram weekly celebrating shit that I used to have to beat you over the head about to convince you that these things were normal: "Detritus Thursday", "Fungal Friday", etc.

And, isn't this what you see in wild aquatic habitats?

None of these things are "bad." We're beyond these concerns that were partially rooted in fear, and the other part in our desire to fit in with the mainstream hobby crowd's aesthetic preferences. We've finally accepted that our "normal" is very different from almost every other hobby specialty's view of "normal."

My development, use, and marketing of our NatureBase line of sedimented substrates reflected another big step in my growing confidence about what is "normal: in our world. These substrates are filled with materials which will make your water turbid for a while...and we absolutely DON'T recommend any sort of preparation before using them.

Your tank WILL get cloudy for a few days...Absolutely part of the process. I remember a lot of sleepless nights, discussions with Johnny Citotti and Jake Adams before launching the product, and just convincing myself that it was okay to convince fellow hobbyists to...relax bit about this stuff and embrace it, in exchange for the manifold benefits of utilizing more truly natural substrate materials.

The entire botanical method aquarium movement has been, and likely will continue to be- an exercise in stepping out of our hobby "comfort zones" on a regular basis. Trying out ideas which have long been contrary to mainstream aquairum hobby practice and philosophy. Ideas and practices which question and challenge the "status quo", and seem to go against a century of aquarium work, in favor of embracing the way Nature has done things for eons.

It's a big "ask", but you keep accepting it...and we've all grown together as a result.

Another seismic shift (in my head, anyways...) is my acceptance that... leaves are leaves. Yeah, seriously. Wether they come from the rainforest of Borneo or the mountains of West Virginia, leaves are essentially similar to each other. Sure, soem look different, or perhaps might have different concentrations of compounds within their tissues...yet they're all fundamentally the same. They perform the same function for the tree, and "behave" similarly when submerged in water.

A Catappa leaf from Malaysia, Jackfruit leaf from India, or a Live Oak leaf from Southern California are more alike than they are dissimilar. Other than having slightly different concentrations of tannins (and even that is possibly minimal), a leaf is a leaf. To convene ourselves otherwise is kind of funny, actually.

I did for a long time. I was 100% convinced that the leaves I was painstakingly sourcing from remote corners of the globe were somehow better than our Native Magnolia or Live Oak or whatever. The reality is that, other than some exotic sounding names, a morphology that might be different, or a good story about where they come from, the "advantages" of most "exotic" leaves over "domestically sourced" leaves ( or leaves from wherever you come from) are really minimal at best.

Trust me- no Catappa leaves find their way into tributaries of the Orinoco river. It's Ficus, Havea leaves, various palms, etc.

But not Catappa, Guava, or Jackfruit.

And if they did, they likely impact the water chemistry or ecology no differently.

Leaves are leaves. In fact, ecologically, they all essentially do the same thing, just on a different "timetable." Trees in tropical deciduous forests lose their leaves in the dry season and regrow them in the rainy season, whereas, temperate deciduous forests, trees lose their leaves in the fall and regrow them in the spring.

In the moist forests close to the equator, the climate is warm and there is plenty of rainfall all year round. In this environment there is no reason for the trees to drop their leaves at any particular time of year, so the forest stays green year round.

Trees from temperate climate zones lose leaves regularly during certain times of the year and then regrow them., and must take a fairly precise cue from their environment. In the mid and high latitudes, if trees put the leaves out too early in the year, these may be damaged by frost and valuable nutrients lost, because the tree cannot easily reclaim nutrients from a frost-bitten leaf.

Yeah, leaves...They perform similar functions for their trees, regardless of where they come from.

The morphological differences are often subtle, and sometimes inconsistent:

It has long been recognized by science that tropical forests are dominated by evergreen trees that have leaves with "complete" margins, whereas trees of temperate forests tend to have deciduous leaves with toothed or lobed margins.

Maybe leaves from different habitats and environments look a bit different, and fall at different times...but that's really about it...

I'm sure that this is not an "absolute" sure- there ARE trees which have leaves with higher concentrations of tannins, etc than others...However, by and large, there are not all that many compelling arguments to favor "exotic" leaves from faraway places over the ones you can source locally!

Sure, soem botanist somewhere could school my on over-generalizing this, but in the aquairum world, I'm not certain one could successfully prove that you MUST use "Pango Pango leaves" from Cameroon to be successful with botanical method aquariums. Now, could one argue that there are some subtle chemical ben efiots to fishes from these regions by using "local" botanicals in their tanks? Maybe. But by and large, I just don't think so anymore.

So,as a hobbyist and vendor, I'm not completely engrossed by chasing every exotic sounding leaf out there anymore.

I may offer limited quantities of the "big three" in the future, but I feel less and less compelled to do so. Trying to be the aquarium world's "catalogue" of tropical leaves for aquariums long ago lost its luster, among the realities of supply chain issues, tariffs, and unreliable producers. Let other vendors chase the dollars. I'm going to chase my ideas...and use whatever materials I see fit for purpose- regardless of their origin.

Constantly changing. Persistently Evolving.

We're in an amazing time right now. For the first time in years, I personally feel that the idea of botanical method aquariums has moved out of it's obscure, "fringe-culture-like" parking spot in the fish world, and into the light of the mainstream.

And it's all because of YOU! Sure, many of you were playing with "blackwater" tanks before, but if your experience was anything like mine, you were sort of viewed as a mildly eccentric hobbyist playing with a little "side thing"- a passing fancy that you'd eventually "get over.."

Well, I think that is changing a lot now. We're seeing a community of what was once widely scattered hobbyists starting to come together and share ideas, technique, pictures, inspiration with other equally as obsessed hobbyists. This is an amazing thing to me, and to be able to witness it firsthand is incredible! It's been a renaissance of sorts for this once-neglected aspect of the hobby.

Another think that I think is interesting is that we, as a community, are viewing our aquariums as "habitats" more than ever before. We seem to have broken through the mindset of creating aquariums only based on an aesthetic WE like, and fitting the fishes into it, as opposed to creating aquariums with specialized habitats for specific fishes.

And we're not afraid to make little detours- small changes. And, not all of them need be intentional. Things happening in unexpected ways are what can propel the hobby forward.

Everything doesn't have to follow a plan.

A detour can be amazing.

However, if your looking for a specific result and go too far in a different direction, it's often a recipe for frustration for those of us not prepared of it. Sure, many of us can simply "go with the flow" and accept the changes we made as part of the process, but the aquarist with a very pure vision and course will work through such self-created deviations until he or she gets to the destination.

Many find this completely frustrating.

Others find this a compelling part of the creative process.

Pretty much every major breakthrough I've encountered in my hobby "practice" has been the result of me "breaking pattern" and trying something fairly radically new...You know, a big remake of an aquarium....Trying a new manipulation of the environment, etc.

And of course, the thing which maintains the "breakthrough?"

Well...

I've always had this thing about repetition and doing the same stuff over and over agin in my aquarium practice. It's one of the real "truisms", to me, about fish keeping: Once you've gotten in a groove, in terms of husbandry routines, it's great to just do the same thing over and over again.

Consistency.

Yes, I beat the shit out of that idea fairly regularly, right?

Now, notice that I'm not talking about doing the same thing over and over when it comes to ideas...Nope. I'm of the opinion that you should do all sorts of crazy things when it comes to concepts and experiments.

One thing that was sort of "experimental" for many years in my world was the idea of NOT removing decomposing botanical materials from my tanks. You know, flat-out siphoning stuff out, lest it do "something" to the water quality in my aquariums.

It was a big deal about 20 years ago...People thought I was crazy for talking about leaving leaves and botnaicals in the tank until they fully decomposed. I was told that if I didn't remove this stuff, all sorts of horrifying outcomes would ensue. Yet, in the back of my mind, I thought to myself, "If the whole idea of botanical method aquariums is to facilitate an ecosystem within the tank, wouldn't removing a significant source of the ecology (ie; decomposing leaves and botanical detritus) be MORE negative than leaving iot in the tank to be "worked" by the resident life forms at various levels?

So I left the stuff in...

Never had any "bad" results...

It really wasn't that surprising, in actuality.

I figured that this would actually be beneficial to the aquairum...My theory was steeped in the mindset that you've created a little ecosystem, and if you start removing a significant source of someone's food (or for that matter, their home!), there is bound to be a net loss of biota...and this could lead to a disruption of the very biological processes that we aim to foster.

Okay, it was a theory...But I think I am on to something, maybe? So, like here is my "theory" in more detail:

Simply look at the botanical-method aquarium (like any aquarium, of course) as a little "microcosm", with processes and life forms dependent upon each other for food, shelter, and other aspects of their existence. And, I really believe that the environment of this type of aquarium, because it relies on botanical materials (leaves, seed pods, etc.), is more signficantly influenced by the amount and composition of said material to "operate" successfully over time.

Just like in natural aquatic ecosystems...

Detritus...the nemesis of the hobby...not all that bad, really..

It's all about not simply accepting the generally held hobby "truisms" as "gospel" in EVERY situation. Experimenting and considering stuff in context is important.

Change and variation is inevitable and important in the hobby. Being open minded about things is vital.

The processes of evolution, change and disruption which occur in natural aquatic habitats- and in our aquariums- are important on many levels. They encourage ecological diversity, create new niches, and revitalize the biome. Changes can be viewed as frightening, damaging events...Or, we can consider them necessary processes which contribute to the very survival of aquatic ecosystems.

Think about that the next time you hesitate to experiment with that new idea, or play a hunch that you might have. Remember that there is always a bit of discomfort, trepidation, and risk when you make changes or conduct bold experiments.

Goes with the territory, really.

However, once you get out of that comfort zone, you're really living...and the fear will give way to exhilaration and maybe even triumph! Because in the aquarium hobby, the bleeding edge is when you're constantly changing, and patiently evolving.

Stay Brave. Stay persistent. Stay curious. Stay thoughtful. Stay creative...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Race to the bottom...

.

Substrates, IMHO, are one of the most often-overlooked components of the aquarium. We tend to just add a bag of "_____________" to our tanks and move on to the "more exciting" stuff like rocks and "designer" wood. It's true! Other than planted aquarium enthusiasts, the vast majority of hobbyists seem to have little more than a passing interest in creating and managing a specialized substrate or associated ecology.

And, when we observe natural aquatic ecosystems, I think we as a whole tend to pay scant little attention to the composition of the materials which form the substrate; how they aggregate, and what occurs when they do.

I'm obsessed with the idea of "functionally aesthetic" substrates in our botanical-style aquariums.

It's because I imagine the substrate as this magical place which fuels all sorts of processes within our aquariums, and that Nature tends to it in the most effective and judicious manner.

Yeah, I'm a bit of a "substrate romantic", I suppose.😆

I think a lot of this comes from my long experience with reef aquariums, and the so-called "deep sand beds" that were quite popular in the early 2000's.

A deep sand bed is (just like it sounds) a layer of fine sand on the bottom of the aquarium, intended to grow bacteria in the deepest layers, which convert nitrate or nitrite to nitrogen gas. This process is generically called "denitrification", and it's one of the benefits of having an undisturbed layer of substrate on the bottom of the aquarium.

Fine sand and sediment is a perfect "media" upon which to culture these bacteria, with its abundant surface area. Now, the deep sand bed also serves as a location within the aquarium to process and export dissolved nutrients, sequester detritus (our old friend), and convert fish poop and uneaten food into a "format" that is usable by many different life forms.

In short, a healthy, undisturbed sandbed is a nutrient processing center, a supplemental food production locale, and a microhabitat for aquatic organisms.

You probably already know most of this stuff, especially if you've kept a reef tank before. And of course, there are reefers who absolutely vilify sandbeds, because they feel that they "compete" with corals, and ultimately can "leach" out the unwanted organics that they sequester, back into the aquarium. I personally disagree with that whole thing, but that's another battle for another time and place!

Okay, saltwater diversion aside, the concept of a deep substrate layer in a botanical-style aquarium continues to fascinate me. I think that the benefits for our systems are analogous to those occurring in reef tanks- and of course, in Nature. In my opinion, an undisturbed deep substrate layer in the botanical-style aquarium, consisting of all sorts of materials, from sand/sediments to leaves to twigs and broken-up pieces of botanicals,can foster all sorts of support functions.

I've always been a fan of in my aquarium keeping work of allowing Nature to take its course in some things, as you know. And this is a philosophy which plays right into my love of dynamic aquarium substrates. If left to their own devices, they function in an efficient, almost predictable manner.

Nature has this "thing" about finding a way to work in all sorts of situations.

And, I have this "thing" about not wanting to mess with stuff once it's up and running smoothly... Like, I will engage in regular maintenance (ie; water exchanges, etc.), but I avoid any heavy "tweaks" as a matter of practice. In particular, I tend not to disturb the substrate in my aquariums. A lot of stuff is going on down there...

Amazing stuff.

I realize, when contemplating really deep aggregations of substrate materials in the aquarium, that we're dealing with closed systems, and the dynamics which affect them are way different than those in Nature, for the most part.

And I realize that experimenting with these unusual approaches to substrates requires not only a sense of adventure, a direction, and some discipline- but a willingness to accept and deal with an entirely different aesthetic than what we know and love. And this also includes pushing into areas and ideas which might make us uncomfortable, not just for the way they look, but for what we are told might be possible risks.

One of the things that many hobbyists ponder when we contemplate creating deep, botanical-heavy substrates, consisting of leaves, sand, and other botanical materials is the buildup of hydrogen sulfide, CO2, and other undesirable compounds within the substrate.

Well, it does make sense that if you have a large amount of decomposing material in an aquarium, that some of these compounds are going to accumulate in heavily-"active" substrates. Now, the big "bogeyman" that we all seem to zero in on in our "sum of all fears" scenarios is hydrogen sulfide, which results from bacterial breakdown of organic matter in the total absence of oxygen.

Let's think about this for just a second.

In a botanical bed with materials placed on the substrate, or loosely mixed into the top layers, will it all "pack down" enough to the point where there is a complete lack of oxygen and we develop a significant amount of this reviled compound in our tanks? I think that we're more likely to see some oxygen in this layer of materials, and I can't help but speculate- and yeah, it IS just speculation- that actual de-nitirifcation (nitrate reduction), which lowers nitrates while producing free nitrogen, might actually be able to occur in a "deep botanical" bed.

There is that curious, nagging "thing" I have in my head about the ability of botanical-influenced substrates to foster denitrification. With the diverse assemblage of microorganisms and a continuous food source of decomposing botanicals "in house", I can't help but think that such "living substrates" create a surprisingly diverse and utilitarian biological support system for our aquariums.

And it's certainly possible to have denitrification without dangerous hydrogen sulfide levels. As long as even very small amounts of oxygen and nitrates can penetrate into the substrate, this will not become an issue for most systems. I have yet to see a botanical-style aquarium where the material has become so "compacted" as to appear to have no circulation whatsoever within the botanical layer.

Now, sure, I'm not a scientist, and I base this on close visual inspection of numerous aquariums, and the basic chemical tests I've run on my systems under a variety of circumstances. As one who has made it a point to keep my botanical-method aquariums in operation for very extended time frames, I think this is significant. The "bad" side effects we're talking about should manifest over these longer time frames...and they just haven't.

And then there's the question of nitrate.

Although not the terror that ammonia and nitrite are known to be, nitrate is much less so. However, as nitrate accumulates, fish will eventually suffer some health issues. Ideally, we strive to keep our nitrate levels no higher than 5-10ppm in our aquariums. As a reef aquarist, I've always been of the "...keep it as close to zero as possible." mindset (that's evolved in recent years, btw), but that is not always the most realistic or achievable target in a heavily-botanical-laden aquarium. You have a bit more "wiggle room", IMHO. Now, when you start creeping towards 50ppm, you're getting closer towards a number that should alert you. It's not a big "stretch" from 50ppm to 75ppm and higher...

And then you get towards the range where health issues could manifest themselves in your fishes. Now, many fishes will not show any symptoms of nitrate poisoning until the nitrate level reaches 100 ppm or more. However, studies have shown that long-term exposure to concentrations of nitrate stresses fishes, making them more susceptible to disease, affecting their growth rates, and inhibiting spawning in many species.

At those really high nitrate levels, fishes will become noticeably lethargic, and may have other health issues that are obvious upon visual inspection, such as open sores or reddish patches on their skin. And then, you'd have those "mysterious deaths" and the sudden death (essentially from shock) of newly-added fishes to the aquarium, because they're not acclimated to the higher nitrate concentrations.

Okay, that's scary stuff. However, high nitrate concentrations are not only manageable- they're something that's completely avoidable in our aquairums.

Quite honestly, even in the most heavily-botanical-laden systems I've played with, I have personally never seen a higher nitrate reading than around 5ppm. I attribute this to common sense stuff: Good quality source water (RO/DI), careful stocking, feeding, good circulation, not disturbing the substrate, and consistent basic aquarium husbandry practices (water changes, filter maintenance, etc.).

Now, that's just me. I'm no scientist, certainly not a chemist, but I have a basic understanding of maintaining a healthy nitrogen cycle in the aquarium. And I am habitual-perhaps even obsessive- about consistent maintenance. Water exchanges are not a "when I get around to it" thing in my aquarium management "playbook"- they're "baked in" to my practice.

And I think that a healthy, ecologically varied substrate is one of the keys to a successful botanical method aquarium.

I'm really into creating substrates that are a reasonable representation of the bottom of streams, tributaries, and igapo, as found in the Amazon basin. Each one of these has some unique characteristics, and each one presents an interesting creative challenge for the intrepid hobbyist. Until quite recently, the most common materials we had to work with when attempting to replicate these substrates were sand, natural and colored gravels, and clay-comprised planted aquarium substrates.

I reiterate a "manifesto" of sorts that I played out in "The Tint" back in 2015:

"If I have something to say about the matter, you'll soon be incorporating a wide variety of other materials into your biotope aquarium substrate!"

Damn, did I just quote myself?

I did!

If you've seen pictures and videos taken underwater in tropical streams (again, I'm pulling heavily from the Amazonian region), you'll note that there is a lot of loose, soil-like material over a harder mud/sand substrate. Obviously, using an entirely soil-based substrate in an aquarium, although technically possible and definitely cool- could result in a yucky mess whenever you disturb the material during routine maintenance and other tasks. You can, however, mix in some of these materials with the more commonly found sand.

So, exactly what "materials" am I referring to here?

Well, let's look at Nature for a second.

Natural streams, lakes, and rivers typically have substrates comprised of materials of multiple "grades", including fine, medium, and coarse materials, such as pebbles, gravels, silty clays and sands. In the aquarium, we seem to have embraced the idea of a homogenous particle size for our substrates for many years. Now, don't get me wrong- it's aesthetically just fine, and works great. However, it's not always the most interesting to look at, nor is it necessarily the most biologically diverse are of the aquarium.

A lot of natural stream bottoms are complimented with aggregations of other materials like leaf litter, branches, roots, and other decomposing plant matter, creating a dynamic, loose-appearing substrate, with lots of potential for biological benefits. Of course, we need to understand the implications of creating such "dynamic" substrates in our closed aquariums.

When we started Tannin, my fascination with the varied substrate materials of tropical ecosystems got me thinking about ways to more accurately replicate those found in flooded forests, streams, and diverse habitats like peat swamps, estuaries, creeks, even puddles- and others which tend to be influenced as much by the surrounding flora (mainly forests and jungles) as it is by geology.

And of course, my obsession with botanical materials to influence and accent the aquarium habitat caused me to look at the use of certain materials for what I generically call "substrate enrichment" - adding materials reminiscent of those found in the wild to augment the more "traditional" sands and other substrates used in aquariums to foster biodiversity and nutrient processing functions.

Again, look to Nature...

If you've seen pictures and videos taken underwater in tropical streams (again, I'm pulling heavily from the Amazonian region), you'll note that there is a lot of loose, soil-like material over a harder mud/sand substrate. Obviously, using an entirely mud-based substrate in an aquarium, although technically possible- will result in a yucky mess whenever you disturb the material during routine maintenance and other tasks. You can, however, mix in some other materials with the more commonly found sand.

That was the whole thinking behind "Substrato Fino" and "Fundo Tropical", two of our most popular substrate "enrichment" materials. They are perfect for helping to more realistically replicate both the look and function of the substrates found in some of these natural habitats. They provide surface area for fungal and microbial growth, and interstitial spaces for smalll crustaceans and other organisms to forage upon.

Substrates aren't just "the bottom of the tank..."

Rather, they are diverse harbors of life, ranging from fungal and biofilm mats, to algae, to epiphytic plants. Decomposing leaves, seed pods, and tree branches compose the substrate for a complex web of life which helps the fishes were so fascinated by flourish. And, if you look at them objectively and carefully, they are beautiful.

I encourage you to study the natural environment, particularly niche habitats or areas of the streams, rivers, and lakes- and draw inspiration from the functionality of these zones. The aesthetic component will come together virtually by itself. And accepting the varied, diverse, not-quite-so-pritinh look of the "real thing" will give you a greater appreciation for the wonders of nature, and unlock new creative possibilities.

In regards to the substrate materials themselves, I'm fascinated by the different types of soils or substrate materials which occur in blackwater systems and their clearwater counterparts, and how they influence the aquatic environment.

For example, as we've discussed numerous times over the years, "blackwater" is not cased by leaves and such- it's created via geological processes.

In general, blackwaters originate from sandy soils. High concentrations of humic acids in the water are thought to occur in drainages with what scientists call "podzol" sandy soils. "Podzol" is a soil classification which describes an infertile acidic soil having an "ashlike" subsurface layer from which minerals have been leached.

That last part is interesting, and helps explain in part the absence of minerals in blackwater. And more than one hobbyist I know has played with the concept of "dirted" planted tanks, using terrestrial soils...hmmm.

Also interesting to note is that fact that soluble humic acids are adsorbed by clay minerals in what are known as"oxisol" soils, resulting in clear waters."Oxisol" soils are often classified as "laterite" soils, which some who grow plants are familiar with, known for their richness in iron and aluminum oxides. I'm no chemist, or even a planted tank geek..but aren't those important elements for aquatic plants?

Yeah.

Interesting.

Let's state it one more time:

We have the terrestrial environment influencing the aquatic environment, and fishes that live in the aquatic environment influencing the terrestrial environment! T

his is really complicated stuff- and interesting! And the idea that terrestrial environments and materials influence aquatic ones- and vice-versa- is compelling and could be an interesting area to contemplate for us hobbyists!

When ecologists study the substrate composition of aquatic habitats like those in The Amazon, they tend to break them down into several categories, broad though they may be: Rock, sand, coarse leaf litter, fine leaf litter, and branches, trunks and roots.

Studies indicate that terrestrial inputs from rainforest streams provide numerous benefits for fishes, providing a wide range of substrate materials that supported a wider range of fishes than can be found in non-forested streams. One study concluded that, "Inputs from forests such as woody debris and leaf litter were found to support a diversity of habitat niches that can provide nursing grounds and refuges against predators (Juen et al. 2016). Substrate size was also larger in forest stream habitats, adding to the complexity and variety of microhabitats that can accommodate a greater and more diverse range of fish species (Zeni et al. 2019)."

But wait- there's more! Rainforests create uniquely diverse aquatic habitats.

"Forests can further diversify and stabilize the types of food available for fish by supplying both allochthonous inputs from leaf litter and increased availability of terrestrial insects that fall directly into the water (Zeni and Casatti). Forest habitats can support a diverse range of trophic guilds including terrestrial insectivores and herbivores (Zeni and Casatti).

Riparian forests deliver leaf litter in streams attracting insects, algae, and biofilm, each of which may be vital for particular fish species (Giam et al., Juen et al. ). In contrast, nonforested streams may lack the allochthonous food inputs that support terrestrial feeding fish species..."

Leaf litter- yet again.

And then there are soils...terrestrial soils- which, to me, are to me the most interesting possible substrates in wild aquatic habitats.

So, the idea of a rich soil substrate that not only accommodates the needs of the plants, but provides a "media" in which beneficial bacteria can grow and multiply is a huge "plus" for our closed aquatic ecosystems. And the concepts of embracing Nature and her processes work really well with the stuff we are playing with.

As you've seen over the past few years, I've been focusing a lot on my long-running "Urban Igapo" idea and experiments, sharing with you my adventures with rich soils, decomposing leaf litter, tinted water, immersion-tolerant terrestrial plants, and silty, muddy, rich substrates. This is, I think, an analogous or derivative concept to the "Walstad Method", as it embraces a more holistic approach to fostering an ecosystem; a "functionally aesthetic" aquarium, rather than a pure aesthetic one.

The importance of incorporating rich soils and silted substrates is, I think, an entirely new (and potentially dynamic) direction for blackwater/botanical-style tanks, because it not only embraces the substrate not just as a place to throw seed pods, wood, rocks, and plants- but as the literal foundation of a stable, diverse ecosystem, which facilitates the growth of beneficial organisms which become an important and integral part of the aquarium.

And that has inspired me to spend a lot of time over the past couple of years developing more "biotope-specific" substrates to compliment the type of aquariums we play with.

When we couple this use of non-conventional (for now, anyways...) substrate materials with the idea of "seeding" our aquariums with beneficial organisms (like small crustaceans, worms, etc.) to serve not only as nutrient processing "assistants", but to create a supplementary food source for our fishes, it becomes a very cool field of work.

As creatures like copepods and worms "work" the substrate and aerate and mix it, they serve to stabilize the aquarium and support the overall environment.

Nutrient cycling.

That's a huge takeaway here. I'm sure that's perhaps the biggest point of it all. By allying with the benthic life forms which inhabit it, the substrate can foster decomposition and "processing"of a wide range of materials- to provide nutrition for plants- or in our case- for the microbiome of the overall system.

There is so much work to do in this area...it's really just beginning in our little niche. And, how funny is it that what seems to be an approach that peaked and fell into a bit of disfavor or perhaps (unintended) "reclassification"- is actually being "resurrected" in some areas of the planted aquarium world ( it never "died" in others...).

And a variation/application of it is gradually starting to work it's way into the natural, botanical-method aquarium approach that we favor.

Substrates are not just "the bottom."

They are diverse harbors of life, ranging from fungal and biofilm mats, to algae, to epiphytic plants. Decomposing leaves, seed pods, and tree branches compose the substrate for a complex web of life which helps the fishes we're so fascinated by to flourish.

And, if you look at them objectively and carefully, they are beautiful.

Stay curious. Stay ob servant. Stay thoughtful. Stay bold...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquaitcs

Perpetual darkness...

Okay, that was an admittedly "dark"-sounding title, but it's perfectly appropriate for today's topic...How to get- and keep- your water as tinted as possible. Or, at least, what materials would do the best job in terms of "color production."

We as a group are kind of obsessed with this.

And yeah, it's a good question!

Now, first off- let's all remember that the color of the water has absolutely NO relationship to its pH or carbonate hardness. It just doesn't. You can have water that looks super dark brown, yet has a pH of 8.5 or whatever. And conversely, it's just as possible to have crystal clear blue-white water that's soft, and has a pH of 4.5. We have to get beyond the social media-style "blackwater" definition, which seems to be, "If the water is tinted, it's a blackwater aquarium!"

Now, look, if you just want the nice color but could care less about the pH and hardness, that's fine. For the benefit of the hobby as a whole, please don't perpetuate the confusing narrative about blackwater aquariums by telling others that you have "blackwater." You have a "tinted" aquairum.

And that's just fine.

So, yeah-I'm not going to launch into a long drawn out description today about how ecologists define "blackwater" and what specific chemical characteristics make it up- we've covered it enough over the years...you can deep dive here or elsewhere to get that.

Okay, micro-rant over. Let's get back to the topic.

Remember, this piece is not about how to make blackwater...It's a little more superficial than that...it's about creating an aquarium with color and maintaining it.

First off, one of the "keys" to getting your color that lovely brown is to select the right types and quantities of botanical materials to assist. Now, I'll be the very first to raise my hand and call BS on anyone who claims to have a perfect "recipe" for how many Catappa leaves per liter or whatever you must use to achieve a specific color. Sure, you could come up with some generic recommendations, but they're not always applicable to every tank or situation.

Yes...there are simply so many variables in the equation- many which we probably haven't even considered yet-that it would be simply guessing. Just like Nature, to some extent...

What I can do is recommend some materials which we have found over the years to generally impart the most reliable and significant color to water. In no particular order, I'll give you my thought on a few of my personal faves. There are a lot more, but these are some that consistently show up on my "fave" list.

Wood

Yep, you heard me. One of the very best sources of tint-producing tannins in our aquariums is wood. I've told you many times, wood imparts tannins, lignin, and all sorts of other "stuff" from the exterior surfaces and all of those nooks and crannies that we love so much into the water.

Ahh...the tannins.

Now, I don't know about you, but I'm always amused (it's not that hard, actually) by the frantic posts on aquarium forums from hobbyists that their water is turning brown after adding a piece of wood. I mean- what's the big deal?

Oh, yeah, not everyone likes it...I forgot that. 😂

The reality, though, as you probably have surmised, is that wood will continue to leach tannins to a certain extent pretty much for as long as it's submerged. As a "tinter", I see this as a great advantage in helping establish and maintain the blackwater look, and to impart humic substances that are known to have health benefits for fishes.

Some wood types, like Mangrove ( a wood we don't have at the moment), tend to release more tannins than others over long periods of time. Other types, like "Spider Wood", will release their tannins relatively quickly, in a big burst. Some, such as Manzanita wood, seem to be really "dirty", and release a lot of materials over long periods of time. All will recruit fungal growths and bacterial biofilms.

And the biocover on the wood is a unique functional aesthetic, too, as we rant on and on about here!

Bark

I'm a huge fan of tree bark to impart not only color, but beneficial tannins into the water. Because of its composition and structure, bark tends to last a very long time when submerged, and tends to impart a lot of color to the water over the long term.

And to be quite honest, almost all of the bark products we've played with over the years seem to work equally as well. The real difference in bark is the "form factor" (appearance) and the color that they impart to the water over time. Some, such as Red Mangrove bark or Cutch bark, will impart a much deeper, reddish-brown tint to the water than say, an equal quantity of catappa bark. And our soon-to-be-released Ichnocarpus bark really packs in this reddish brown color! You're gonna love this stuff!

Ounce for ounce, gram for gram, I've always felt that various types of bark always impart the most color to the water over almost any other materials.

"Skyfruit Pods"

These are very interesting, woody pods, derived from the outer "valve" of the fruit of the Swietenia macrophylla tree, which hails from a wide range of tropical locales (although native to Brazil), and are just the sort of thing you'd find floating or submerged in a tropical jungle stream. Often called "Skyfruit" by locals in the regions in which they're found because they hang from the trees- a name we fell in love with!

These botanicals can leach a terrific amount of tannins, akin to a similar-sized piece of Mopani wood or other driftwood. They are known to be full of flavonoids, saponins, and other humic substances, which have known positive health effects on fishes. Like bark, it lasts a good long time and recruits some biofilms and fungal growths for good measure.

Live Oak Leaves/Magnolia Leaves

Despite their humble North American origins, these leaf types impart more color, ounce per ounce, than just about any of our fave tropical leaves. And they both last very long time...Like, I've had specimens of live oak leaves stay intact for several months!

It's really important to think of leaves as not just a "coloring agent" for your water, but as a sort of biological support mechanism for your burgeoning ecosystem. They actively recruit fungi, bacterial biofilms, and other microorganisms which enrich the overall aquatic environment in your tank.

Cones

Alder cones (Aalnus glutinosa and Alnus incana) and Birch cones (Betula occidentalis), have been widely utilized by aquarium hobbyists in Europe for some time. Betta and ornamental shrimp breeders are fond of the tannins released into the water by these cones, and their alleged anti fungal and antibacterial properties. There has also been much study by hobbyists about the pH reduction attributes of these cones, too.

A study done a few years back by a Swedish hobbyist using from one to six cones in a glass containing about 10 ounces of tap water, with a starting ph of around 8.12, was able to affect a drop to 6.74 with one cone after about two weeks, 4.79 with 2 cones after two weeks, and an amazing 3.84 with 6 cones after the same time period! The biggest part of the drop in pH occurred in the first 12 hours after immersion of the cones!

Now, I'm the last guy to tell you that a bunch of cones is the perfect way to lower pH, but this and other hobby-level studies seem to have effectively have demonstrated their ability to drive pH down in "malleable" (soft) water...

Coconut-based products (Coco Curls, "Fundo Tropical", "Substrato Fino")

There's something about coconuts...The materials which are derived from the husks of coconuts seem to produce a significant amount of tannins and impart color to the water. Of course, "Substrate Fino" and "Fundo Tropical" are smaller, or finer-textured materials which work primarily as "substrate enhancers", and not strictly as "color-producing agents", because there is an initial "burst", which subsides over time.

Now, one of the novel applications for these finer botanical materials to take advantage of their color producing ability is to place them in a fine mesh filter bag and allow water to flow around or through them, like filter media. Essentially, a more sustainable alternative to the old peat moss trick...

Oak Twigs

For an interesting look and some nice color, I'm a big fan of oak twigs. Oak has a nice bark which imparts a deep brownish/yellow color to the water and it's quite distinctive. There is a reason why our "Twenty Twigs" packs are pretty popular, and it's not just because you get a bunch of cool sticks!

When mixed with leaves and/or other botanical materials, not only do you get an incredible "framework" for a cool ecosystem, you get an incredible aesthetic as well!

Now, this is an absolutely cursory list.. I could have easily listed 10 or more items. No doubt, some of you hardcore enthusiasts are screaming at your screens now: "WTF Fellman, you didn't include_______!"

And of course, that's the beauty of natural materials...There are numerous options!

Another note on the colors to expect from various botanical materials. As you might suspect, many of the lighter colored ones will impart a correspondingly lighter tint to the water. And, some leaves, such as Guava or Loquat, also impart a more yellowish or golden color to the water, as opposed to the brownish color which Jackfruit and Catappa are known for.

A lot of you ask about things that impact how long the water retains it's tint.

This kind stuff is a big deal for us- I get it! Many hobbyists who have perhaps added some catappa leaves, "blackwater extracts", or rooibos tea to their water contact me asking stuff like why the water doesn't stay tinted for more than a few days. Now, I'm flattered to be a sort of "clearing house" for this stuff, but I must confess, I don't have all the answers.

So, "Why doesn't my water stay tinted, Scott?"

Well, I admit I don't know. Well, not for certain, anyways!

I do, however, have some information, observations, and a bunch of ideas about this- any of which might be literally shot to pieces by someone with the proper scientific background. However, I can toss some of these seemingly uncoordinated facts out there to give our community some stuff to "chew on" as I offer my ideas up.

Now, perhaps it starts with the way we "administer" the color-producing tannins.

Like, I personally think that utilizing leaves, bark, and seed pods is perhaps the best way to do this. I'm sure that you're hardly surprised, right? Well, it's NOT just because I sell these material for a living...It's because they are releasing tannins, humic substances, and other compounds into the water "full time" during their presence in the aquarium as they break down. A sort of "on-board" producer of these materials, with their own "half life" (for want of a better term!).

And, they also perform an ecological role, providing locations for numerous life forms (like fungal growths) surface area upon which to colonize. They become part of the ecosystem itself. A few squirts of "blackwater extracts" won't do that, right?

The continuous release of tint-producing compounds from botanical materials keeps things more-or-less constant. And, if you're part of the "school" which leaves your botanicals in your aquarium to completely break down, you're certainly getting maximum value out of them! And if you are continuously adding/replacing them with new ones as they completely or partially break down, you're actively replenishing and adding additional "tint-producing" capabilities to your system, right?

There is another way to "keep the tint" going in your tanks, and it's pretty easy. Now, those of you who know me and read my rambling or listen to "The Tint" podcast regularly know that I absolutely hate shortcuts and "hacks" in the aquarium hobby. I preach a long, patient game and letting stuff happen in its own time...

Nonetheless, there ARE some that you can employ that don't make you a complete loser, IMHO.😆

When you prepare your water for water changes, it's typically done a few days to a week in advance, so why not use this time to your advantage and "pre-tint" the water by steeping some leaves in it? Not only will it keep the "aesthetics" of your water ( can you believe we're even talking about "the aesthetics of water?") consistent (i.e.; tinted), it will already have humic substances and tannins dissolved into it, helping you keep a more stable system.

Obviously, you'd still check your pH and other parameters, but the addition of leaves to your replacement water is a great little "hack" that you should take advantage of. (Shit, I just recommended a "hack" to you...)

It's also a really good way to get the "look" and some of the benefits of blackwater for your system from the outset, especially for those of you heathens that like the color of blackwater and despise all of the decomposing leaves and seed pods and stuff!

So, if you're just setting up a brand new aquarium, and have some water set aside for the tank, why not use the time while it's aging to "pre-tint" it a bit, so you can have a nice dark look from day one? It's also great if you're setting up a tank for an aquascaping contest or other same-day club event that would make it advantageous to have a tinted tank immediately.

I must confess that yet another one of the more common questions we receive here from hobbyists is, "How can I get the tint in my tank more quickly?"- and this is definitely one way!

How many botanicals to use to accomplish this?

Well, that's the million dollar question.

Who knows?

It all gets back to the (IMHO) absurd "recommendations" that have been proffered by vendors over the years recommending using "x" number of leaves, for example, per gallon/liter of water. There are simply far, far too many variables- ranging from starting water chem to pH to alkalinity, and dozens of others- which can affect the "equation" and make specific numbers unreliable at best.

We did, too, in the early days of Tannin. And it was kind of stupid really. There just is no hard-and-fast answer to this. Every situation is different. You need to kind of go with your instinct. Go slowly. Evaluate the appearance of your water, the behaviors of the fishes...the pH, hardness, TDS, nitrate, phosphate, or other parameters that you like to test for.

It's really a matter of experimentation.

I'm a much bigger fan of "tinting" the water based on the materials in the aquarium. Letting Nature have at it. The botanicals will release their "contents" at a pace dictated by their environment. And, when they're "in situ", you have a sort of "on board" continuous release of tannins and humic substances based upon the decomposition rate of the materials you're using, the water chemistry, etc.

Replacement of botanicals, or addition of new ones, as we've pointed out many times, is largely a subjective thing, and the timing, frequency, and extent to which materials are removed or replaced is dependent upon multiple factors, ranging from base water chemistry to temperature, to the types of aquatic life you keep in the tank (ie; xylophores like certain Plecos, or strongly grazing fishes, like Headstanders, will degrade botanicals more quickly than in a tank full of characins and such).

(The part where Scott bashes the shit out of the idea of using "blackwater extracts" and Rooibos tea. This could get nasty!)

If you haven't heard of it before, there is this stuff called Rooibos tea, which, in addition to bing kind of tasty, has been a favored "tint hack" of many hobbyists for years. Without getting into all of the boring details, Rooibos tea is derived from the Aspalathus linearis plant, also known as "Red Bush" in South Africa and other parts of the world.

(Rooibos, Aspalathus linearis. Image by R.Dahlgr- used under CC-BY S.A. 2.5)

It's been used by fish people for a long time as a sort of instant "blackwater extract", and has a lot going for it for this purpose, I suppose. Rooibos tea does not contain caffeine, and and has low levels of tannin compared to black or green tea. And, like catappa leaves and other botnaicals, it contains polyphenols, like flavones, flavanols, aspalathin, etc.

Hobbyists will simply steep it in their aquariums and get the color that they want, and impart some of these substances into their tank water. I mean, it's an easy process. Of course, like any other thing you add to your aquarium, including leaves and botanicals, it's never a bad idea to know the impact of what you're adding.

Like using botanicals, utilizing Rooibos tea bags in your aquarium requires some thinking, that's all.

The things that I personally dislike about using tea or so-called "blackwater extracts" are that you are simply going for an effect, without getting to embrace the functional aesthetics imparted by adding leaves, seed pods, etc. to your aquarium as part of its physical structure and ecology, and that there is no real way to determine how much you need to add to achieve______.

Obviously, the same could be said of botanicals, but we're not utilizing botanicals simply to create brown water or to target specific pH parameters, etc. We're trying to create an ecology that is similar to what you'd see in such habitats in Nature.

Yet, with tea or commercial blackwater extracts, you sort of miss out on replicating a little "slice of Nature" in your aquarium. The building of an ecosystem. Which is why we call this the botanical method. It's not a "style" of aquascaping! And of course, it's fine if your goal is just to color the water, but it's more of an aesthetically-focused aquarium at that point.

I also understand that some people, like fish breeders who need bare bottom tanks or whatever- like to condition water without all of the leaves and twigs and nuts we love. They want the humic substances and tannins, but really don't need/want the actual leaves and other materials in their tanks.