- Continue Shopping

- Your Cart is Empty

Like what Nature Does.

I think that there is something inherently wonderful about doing the aquairum hobby on a "basic" level. You know, real simple approaches. One of these is the idea that excessively intervening in your tank's function, or even looking at every deviation from what you'd consider to be "acceptable" is somehow a "problem" that we need to jump on and solve immediately.

We worry about the danger of letting things "spin out of control..."

The reality is, Nature is in control- even when things seem contrary to what we want. It's not always a "problem" just because your tank doesn't appear the way you want it to. We look for all sorts of "solutions" and "fixes" to our "problems"...And the reality is, in many cases, we don't have to do all that much.

Nature's got this...

Nature eventually sorts it out.

We need to be patient and rational, not impulsive and upset.

Again, this mindset of "zen-like patience" and confidence in Nature "figuring shit out" is but one way of looking at and managing things- and admittingly, it's not for everyone.

Control freaks and obsessive "tinkerers" need not apply.

Intervention, in this case, is more mental than actual. We need to change our thinking! Not every process has- or needs- a "workaround."

The "workaround" is to understand what you're doing, what could happen, WHY it happens, and what the upside/downside of rapidly "correcting it" can be. The key, typically, as with most things in the aquarium world, is to simply be patient.

Despite our best efforts to "fix" stuff- Nature almost always "sorts it out"- and does it way better than we can.

Think about the bane of most hobbyists' existence- So-called "nuisance algae."

It's a "nuisance" to us because it looks like shit.

To us.

It derails our dreams of a pristine aquarium filled with spotless plants, rocks, coral, etc. Despite all of the knowledge we have about algae being fundamental for life on earth, it bothers the shit out of us because we think that it looks "bad."

And collectively as hobbyists, we freak the fuck out about it when it appears.

We panic; do stupid things to get rid of it as quickly as possible. We address its appearance in our tanks. Seldom do we make the effort to understand why it appeared in the first place and to address the circumstances which caused it to proliferate so rapidly. And of course, in our haste to rid our tanks of it, we often fail to take into account how it actually grows, and what benefits it provides for aquatic ecosystems.

Big blooms of algae are simply indicative of a life form taking advantage of an abundance of resources available to it in our tanks.

Algae will ultimately exhaust the available excess nutrients which caused it to appear in the first place, if you take steps to eliminate "re-supplying" them, and if you wait for it to literally "run its course" after these issues have been addressed.It will never fully go away- you don't WANT it to. It will, however, simply reach more "aesthetically tolerable" levels over time.

We've seen this in the reef aquarium world for a generation now. It happens typically in new tanks- a "phase" popularly called "the uglies"- before your tank's ecology sorts itself out. And the reality is, these big algal blooms almost always pass-once we address the root cause and allow it to play out on Nature's time frame.

Of course, as fish geeks, we want stuff to happen fast, so hundreds of products, ranging from additives to filter media, and exotic techniques, such as dosing chemicals, etc. have been developed to "destroy" algae. We throw lots of money and product at this "problem", when the real key would have been to address what causes it in the first place, and to work with that.

Yeah, the irony is that algae is the basis of all life. You don't ever want to really "destroy" the stuff...to do so is folly- and can result in the demise of your entire aquarium ecosystem.

In a reef tank (or freshwater tank, really) it's a necessary component of the ecosystem. And hobbyists will often choose the quick fix, to eradicate it instead of looking at the typical root causes- low quality source water (which would require investing in an RO/DI unit or carbon block to solve), excess nutrients caused by overfeeding/overcrowding, or poor husbandry (all of which need to be addressed to be successful in the hobby,always...), or simply the influx of a large quantity of life forms (like fresh "live rock", substrate, botanicals, corals, fishes, etc...) into a brand new tank with insufficient biological nutrient export mechanisms evolve to handle it.

And often, a "quick kill" upsets the biological balance of the tank, throwing it into a further round of chaos which takes...even longer to sort itself out!

And it will sort itself out.

It could take a very long time. It could result in a very "unnattractive" tank for a while. It could even kill some fishes or plants. I mean, Nature "mounts a comeback" at nuclear test sites and oil spill zones! You don't think that She could bring back your tank from an overdose of freaking algicide?

She can. And She will.

In due time.

If you let Her.

Once these things are understood, and the root causes addressed, the best and most successful way to resolve the algae issue long-term is often to simply be patient and wait it out.

Wait for Nature to adjust on her terms. On her time frame.

She seeks a balance.

Waiting it out is one of the single best "approaches" that you can take for aquariums.

So, it's really about making the effort to understand stuff.

To "buy in" to a process.

Nature's process...

To have reasonable expectations of how things work, based on the way Nature handles stuff- not on our desire to have a quick "#instafamous" aquascape filled with natural-looking, broken-in botanicals two weeks after the tank is first set up, or whatever. It's about realizing that the key ingredients in a successful hobby experience are usually NOT lots of money and flashy, expensive gear- they're education, understanding, and technique, coupled with a healthy dose of patience and observation.

Doing things differently requires a different mental approach.

We work with Nature by attempting to understand her.

By accommodating HER needs, not forcing Her to conform to OURS. Which she won't do in a manner that we'd want, anyways.

Nature will typically "sort stuff out" if we make the effort to understand the processes behind her "work", and if we allow her to do it on HER time frame, not ours. Again, intervention is sometimes required on our part to address urgent matters, like disease, poisoning, etc. in closed systems.

However, for many aquarium issues, simply educating ourselves well in advance, having proper expectations about what will happen, and (above all) being patient while Nature "works the issues" is the real "cure.

So yeah, in our world, it's never a bad idea to let Nature "sort it out."

She's done a pretty good job for billions of years. No sense in bailing out on her now, right?

As we've all started to figure out by now, our botanical-influenced aquariums are a lot more of a little slice of Nature that you're recreating in your home then they are just a "pet-holding container."

The botanical-method aquarium is a microcosm which depends upon botanical materials to impact the environment.

This microcosm consists of a myriad of life forms all levels and all sizes, ranging from our fishes, to small crustaceans, worms, and countless microorganisms. These little guys, the bacteria and Paramecium and the like, comprise what is known as the "microbiome" of our aquariums.

A "microbiome", by definition, is defined as "...a community of microorganisms (such as bacteria, fungi, and viruses) that inhabit a particular environment." (according to Merriam-Webster)

Now, sure, every aquarium has a microbiome to a certain extent:

We have the beneficial bacteria which facilitate the nitrogen cycle, and play an indespensible role in the function of our little worlds. The botanical-method aquarium is no different; in fact, this is where I start wondering...It's the place where my basic high school and college elective-course biology falls away, and you get into more complex aspects of aquatic ecology in aquariums.

Yet, it's important to at least understand this concept as it can relate to aquariums. It's worth doing a bit of research and pondering. It'll educate you, challenge you, and make you a better overall aquarist. In this little blog, we can't possibly cover every aspect of this- but we can touch on a few broad points that are really fascinating and impactful.

So much of this proces-and our understanding starts with...botanicals.

With botanicals breaking down in the aquarium as a result of the growth of fungi and microorganisms, I can't help but wonder if they perform, to some extent, a role in the management-or enhancement-of the nitrogen cycle.

Yeah, you understand the nitrogen cycle, right?

How do botanicals impact this process? Or, more specifically, the microorganisms that they serve?

In other words, does having a bunch of leaves and other botanical materials in the aquarium foster a larger population of these valuable organisms, capable of processing organics- thus creating a more stable, robust biological filtration capacity in the aquarium?

I believe that they do.

With a matrix of natural materials present, do the bacteria (and their biofilms- as we've discussed a number of times here) have not only a "substrate" and surface area upon which to attach and colonize, but an "on board" food source which they can utilize as needed?

Facultative bacteria, adaptable organisms which can use either dissolved oxygen or oxygen obtained from food materials such as sulfate or nitrate ions, would also be capable of switching to fermentation-or anaerobic respiration- if oxygen is absent.

Hmm...fermentation.

Well, that's likely another topic for another time. Let's focus on some of the other more "practical" aspects of this "biome" thing.

Like...food production for our fishes.

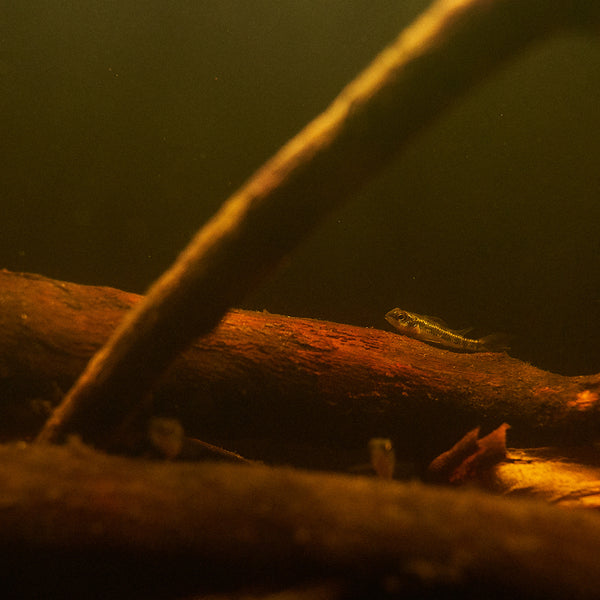

In the case of our fave aquatic habitats, like streams, ponds, and inundated forests, epiphytes, like biofilms and fungal mats are abundant, and many fishes will spend large amounts of time foraging the "biocover" on tree trunks, branches, leaves, and other botanical materials.

The biocover consists of stuff like algae, biofilms, and fungi. It provides sustenance for a large number of fishes all types.

And of course, what happens in Nature also happens the aquarium- if we allow it to, right? And it can function in much the same way?

Yeah. I think that it can.

I think this means that we need to continue to foster the biological diversity of animals in our aquariums- embracing life at all levels- from bacteria to algae to fungi to crustaceans to worms, and ultimately, our fishes...All of which form the basis of a closed ecosystem, and perhaps a "food web" of sorts for our little aquatic microcosms.

It's a very interesting concept- a fascinating field for research for aquarists, and we all have the opportunity to participate in this on a most intimate level by simply observing what's happening in our aquariums every day!

And facilitating this process is remarkably easy. It can be summarized easily in a few points. :

*Approach building an aquarium as if you are creating a biome.

*Foster the growth and development of a community of organisms at all levels.

*Allow these organisms to grow and multiply.

*Don't "edit" the growth of biofilms, fungal growths, and detritus.

Make mental shifts.

These mental shifts require us to embrace these steps, and the occurrences which happen as a result. Understanding that the botanicals and leaves which we add to our aquariums are not "aquascaping set pieces"; but rather that they are "biological facilitators"for the closed ecosystems we are creating is fundamental. These materials are being utilized and assimilated by the organisms which comprise the biome of our aquarium.

By accepting and embracing these changes and little "evolutions", we're helping to create really great functional representations of the compelling wild systems we love so much!

Leaf litter beds, in particular, tend to evolve the most, as leaves are among the most "ephemeral" or transient of botanical materials we use in our aquariums. This is true in Nature, as well, as materials break down or are moved by currents, the structural dynamics of the features change.

New materials arrive constantly.

We have to adapt a new mindset when "aquascaping" with leaves- that being, the 'scape will "evolve" on its own and change constantly...Other than our most basic hardscape aspects- rocks and driftwood- the leaves and such will not remain exactly where we place them.

To the "artistic perfectionist"-type of aquarist, this will be maddening.

To the aquarist who makes the mental shift and accepts this "wabi-sabi" idea (yeah, I'm sort of channeling Amano here...) the experience will be fascinating and enjoyable, with an ever-changing aquarium that will be far, far more "natural" than anything we could ever hope to conceive completely by ourselves.

Change. Evolution. Ecological diversity.

Accepting how various organisms look and function in our tanks. Letting Nature take the lead in your aquarium is vital.

It's not something to freak out about.

Rather, it's something to celebrate! Life, in all of it's diversity and beauty, still needs a stage upon which to perform...and you're helping provide it, even with this "remodeling" of your aquascape taking place daily. Stuff gets moved. Stuff gets covered in biofilm.

Stuff breaks down. In our aquariums, and in Nature.

With botanicals breaking down in the aquarium as a result of the growth of fungi and microorganisms, I can't help but wonder if they perform, to some extent, a role in the management-or enhancement-of the nitrogen cycle.

Yeah, you understand the nitrogen cycle, right?

Okay, I know that you do.

If you really understand how it works, you won't try to beat it; circumvent it.

You won't want to.

Aquarium hobbyists have (by and large) collectively spent the better part of the century trying to create "workarounds" or "hacks", or to work on ways to circumvent what we perceive as "unattractive", "uninteresting", or "detrimental." And I have a theory that many of these things- these processes- that we try to "edit", "polish", or skip altogether, are often the most important and foundational aspects of botanical-method aquarium keeping!

It's why we literally pound it into your head over and over here that you not only shouldn't try to circumvent these processes and occurrences- you should embrace them and attempt to understand exactly what they mean for the fishes that we keep.

They're a key part of the functionality.

Now, I've had a sort of approach to creating and managing botanical method aquariums that has drawn from a lifetime of experience in my other aquarium hobby "disciplines", such as reef keeping, breeding killifish and other more "conventional" hobby areas of interest. And my approach has always been a bit of an extension of the stuff I've learned in those areas.

I've always been fanatical about NOT taking shortcuts in the hobby. In fact, I've probably avoided shortcuts- to the point of making things more difficult for myself at times! Over the years, I have thought a lot about how we as botanical-method aquarium enthusiasts gradually build up our systems, and how the entire approach is about creating a biome- a little closed ecosystem, which requires us to support the organisms which comprise it at every level.

Just like what Nature does.

Stay observant. Stay curious. Stay diligent. Stay bold. Stay patient...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Fixes for a common botanical method aquarium "issue..?"

If you've been in this game long enough, you've likely seen some stuff which leaves you frustrated/baffled/confused, or some combination of the above! And I'm here to tell you that you're not alone in your frustrations. Today, lets look at one of the more common "issues" reported by hobbyists with botanical method aquariums and how to address it...

One of the things I alternately love and loathe about the aquarium hobby is that, no matter what you do; no matter how carefully you plan- no matter how carefully you execute- stuff canc out differently than you might expect.

Why?

Well, the same "variable" which we have come to extoll, emulate, and adore- Nature, of course!

Yeah, Her.

She'll entice, challenge, reward, and punish you- sometimes in the same day! Nature can be wildly unpredictable, yet often thoroughly logical at the same time. You can do everything "right"- and Nature will think of some way to throw a proverbial "wrench" into your plans.

She operates at Her own pace, with Her own rules, indifferent to you or your ideas, practices, and motivations.

Things can even "go sideways" sometimes.

Yet, with all of Her wild and unpredictable actions, it's never a bad idea to show some deference to Her, is it?

With our heavy emphasis on utilizing natural botanical materials in our aquairums, I can't help but think about the long-term of their function and health. Specifically, the changes that they go through as they evolve into little microcosms.

As we've discussed before, a botanical-method aquarium has a “cadence” of its own, which we can facilitate when we set up- but we must let Nature dictate the timing and sequencing. We can enjoy the process- even control some aspects of it...Yet underneath it all, She's in charge from the beginning. She creates the path...

And along this path, you'll encounter some stuff. I get questions...

"Scott, the water in my tank is kind of cloudy..."

Okay, this is one of those topics which can go in a lot of different directions. And we will...

For a lot of reasons, the aquarium hobby has celebrated crystal clear, colorless water as the standard of excellence for generations.

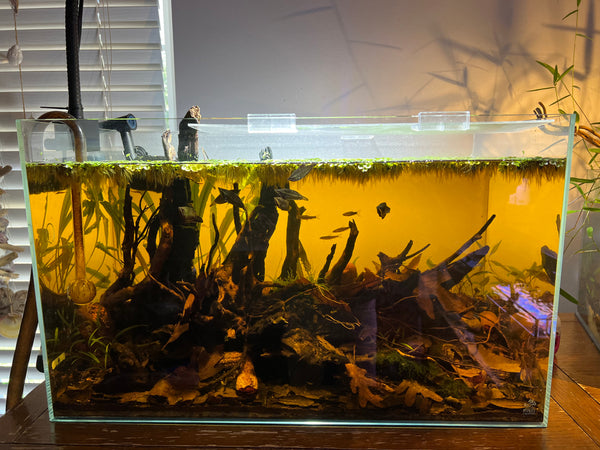

Our colored, often turbid-looking water is a stark contrast to what most hobbyists consider "acceptable" and "healthy."

We just see colored, slightly turbid water and think, "That shit's dirty!"

And of course, this is where we need to attempt to separate the two factors:

Cloudiness and "color" are generally separate issues for most hobbyists, but they both seem to cause concern. Cloudiness, in particular, may be a "tip off" to some other issues in the aquarium.

And, as we all know, cloudiness can usually be caused by a few factors:

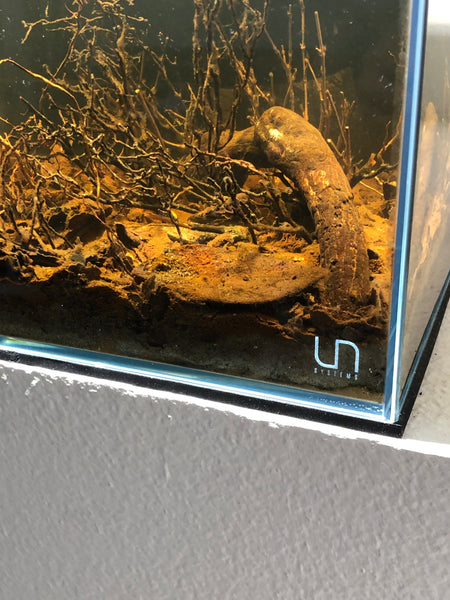

1) Improperly cleaned substrate or decorative materials, such as driftwood, etc. (creating a "haze" of micro-sized dust particles, which float in the water column).

2) Bacterial blooms (typically caused by a heavy bioload in a system not capable of handling it. Ie; a new tank with a filter that is not fully established and a full compliment of livestock).

3) Algae blooms which can both cloud AND color the water (usually caused by excessive nutrients and too much light for a given system).

4) Poor husbandry, which results in heavy decomposition, and more bacterial blooms and biological waste affecting water clarity. This is, of course, a rather urgent matter to be attended to, as there are possible serious consequences to the life in your system.

Those are the typical "players" in most "cloudy water" scenarios, right? Yet, in the botanical method aquarium, the very nature of its existence includes stuff like sedimented substrates, decomposing leaf litter, botanicals, and twigs.

If you place a large quantity of just about anything that can decompose in water, the potential for cloudy water caused by a bloom of bacteria, or even simple "dirt" exists. The reality is, if you don't add 3 pounds of botanicals to your 20 gallon tank, you're not likely to see such a bloom. It's about logic, common sense, and going slowly.

A bit of cloudiness from time to time is actually normal in the botanical-method aquarium.

And, of course, what we label as "normal" in our botanical-method aquarium world has always been a bit different from the hobby at large.

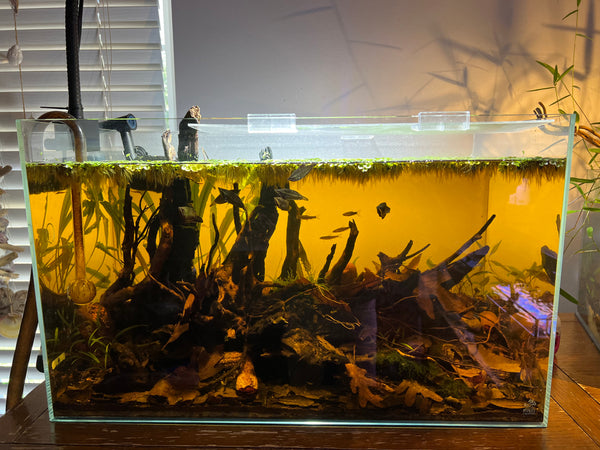

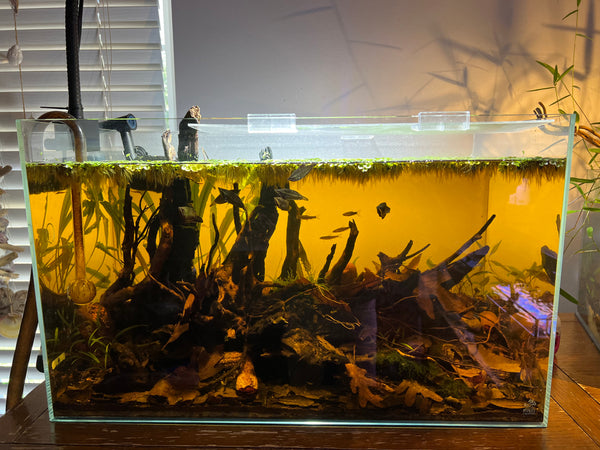

In my home aquariums, and in many of the really great natural-looking blackwater aquariums I see from other hobbyists, the water is dark, almost turbid or "soupy" as one of my fellow blackwater/botanical-style aquarium geeks refers to it. You might see the faintest hint of "stuff" in the water...perhaps a bit of fines from leaves breaking down, some dislodged biofilms, pieces of leaves, etc. Just like in Nature. Chemically, it has undetectable nitrate and phosphate..."clean" by aquarium standards.

Sure, by municipal drinking water standards, color and clarity are important, and can indicate a number of potential issues...But we're not talking about drinking water here, are we?

"Turbidity." Sounds like something we want to avoid, right? Sounds dangerous...

On the other hand, "turbidity", as it's typically defined, leaves open the possibility that it's not a negative thing:

"...the cloudiness or haziness of a fluid caused by large numbers of individual particles that are generally invisible to the naked eye, similar to smoke in air..."

What am I getting at?

Well, think about a body of water like an igapo off of the Rio Negro. This water is of course, "tinted" because of the dissolved tannins and humic substances that are present due to decaying botanical materials.

That's different from "cloudy" or "turbid", however.

It's a distinction that neophytes to our world should make note of. The "rap" on blackwater aquariums for some time was that they look "dirty"- and this was largely based on our bias towards what we are familiar with. And, of course, in the wild, there might be some turbidity because of the runoff of soils from the surrounding forests, incompletely decomposed leaves, current, rain, etc. etc.

None of the possible causes of turbidity mentioned above in these natural watercourses represent a threat to the "quality", per se. Rather, they are the visual sign of an influx of dissolved materials that contribute to the "richness" of the environment. It's what's "normal" for this habitat. It's the arena in which we play in our botanical-method aquariums, as well.

You've got a lot of "stuff" dissolving in the water.

Mental shift required.

Obviously, in the closed environment that is an aquarium, "stuff" dissolving into the water may have significant impact on the overall quality. Even though it may be "normal" in a wild blackwater environment to have all of those dissolved leaves and botanicals, this could be problematic in the closed confines of the aquarium if nitrate, phosphate, and other DOC's contribute to a higher bioload, bacteria count, etc.

Again, though, I think we need to contemplate the difference between water "quality" as expressed by the measure of compounds like nitrate and phosphate, and visual clarity.

And, curiously enough, the "remedy" for "cloudy water" in virtually every situation is similar: Water changes, use of chemical filtration media (activated carbon, etc.), reduced light (in the case of algal blooms), improved husbandry techniques (i.e.; better feeding practices and more frequent maintenance), and, perhaps most important- the passage of time.

So, yeah, clarity of the water in our case is usually directly related to the physical dissolution of "stuff" in the water, and is influenced-and mitigated by- a wide-range of factors. And, don't forget that the botanical materials will impact the clarity of the water as they begin to decompose and impart the lignin, tannins, and other compounds from their physical structure into the water in our aquariums.

This happens indefinitely.

A lot of botanical-method aquariums start out with a little cloudiness. It's often caused by the aforementioned lignin, as well as by a burstsof microbial life which feeds upon these and other constituents of botanicals.

Once this initial "microbial haze phase" passes, there are other aspects to the water clarity which will continue to emerge. And I think that these aspects are similar to what we observe in Nature.

And in many cases, the water will never be "crystal clear" in botanical-influenced aquariums. It will have some "turbidity"-or as one of my friends likes to call it, "flavor."

Remember, just because the water in a botanical-influenced aquarium system is brownish, and even slightly hazy, it doesn't mean that it's of low quality, or "dirty", as we're inclined to say. It simply means that tannins, humic acids, and other substances are leaching into the water, creating a characteristic color that some of us geeks find rather attractive. And the "cloudiness" comes with the territory.

If you're still concerned, monitor the water quality...perform a nitrate or phosphate test; look at the health of your animals. These factors will tell the true story.

You need to ask yourself, "What's happening in there?"

I won't disagree that "clear" water is nice. I like it, too...However, I make the case that "crystal clear" water is: a) not always solely indicative of "healthy" or "optimum" , and b) not always what fishes encounter in Nature.

I believe that a lot of what we perceive to be "normal" in aquarium keeping is based upon artificial "standards" that we've imposed on ourselves over a century of modern aquarium keeping. Everyone expects water to be as clear and colorless as air, so any deviation from this "norm" is cause for concern among many hobbyists.

Natural aquatic ecosystems typically look nothing like what we'd call a "healthy" aquarium.

Yet, many of us don't think about that, or even look objectively about what wild aquatic ecosystems actually look like.

And so we panic and do massive water exchanges, add carbon , or reach for a bottle of...something...to "fix" the "problem...often creating a bigger (and more problematic) PROBLEM than what we were trying to remedy in the first place!

Relax.

Even if your cloudiness is caused by a bloom of bacteria, perhaps from too much botanical materials being added to rapidly to the tank, or simply by overfeeding, it's not a disaster- if you understand it. Knowing what caused it is half of the battle, right? The "fixes" become obvious.

If you're overfeeding, just chill out on the food, right? If you added too much botanical material at one time, stop fucking adding botanicals for a while! You could do some stepped-up water exchanges...or you could just "wait it out", and let Nature catch up.

Often times, it simply takes time for these things to clear up.

Just like in nature.

Chemically, my water typically has virtually undetectable nitrate and phosphate levels...A solid "clean" by aquarium standards.

But, yeah- it's "soupy"-looking...

Other times, it can be crystal clear.

Both are just fine, as long as you're paying attention to the fundamentals of water quality.

Again, in Nature, we see these types of water characteristics in a variety of habitats. While they may not conform to everyone's idea of "beauty", there really IS an elegance, a compelling vibe, and a function to this.

Fish don't care that their water is tinted, a bit turbid, and sometimes downright cloudy.

As we've discussed a lot lately, we're absolutely obsessed with the natural processes and aesthetics of decomposing materials and sediments in our aquariums. And of course, this comes with the requirement of us to accept some unique aesthetic characteristics, of course!

We have, as a community, taken our first tentative footsteps beyond what has long been accepted and understood in the hobby, and are starting to ask new questions, make new observations, and yeah- even a few discoveries- which will evolve the aquarium hobby in the future.

And that means understanding why aquatic habitats look and function the way they do, and embracing things in our aquariums which simply might frighten others...

It's definitely a contrarian thought process, at least. Is it rebellious, even?

Maybe.

I've occasionally had to re-examine my own relationship with my love of unedited Nature, as it relates to the "business" side of things.

Our original mission at Tannin was to share our passion for the reality and function of "unedited" Nature, in all of its murky, brown, fungal-patina-enhanced glory. And I started to realize that a while back, we were starting to fall dangerously into that noisy, (IMHO) absurd, mainstream aquascaping world. Pressing our dirty faces against the pristine glass, we were sort of outsiders looking in...the awkward, different new kid on the block, wanting to play with the others.

Then, the realization hit that we never really wanted to play like that. It's not who we are.

Fuck that.

We are not going to play there.

We're going to keep doing what we're doing. To "double down" in our dirty, tinted, turbid, decomposing, inspired-by Nature world.

We all have to have some understanding about what's "normal" when we try to replicate Nature in our tanks in a more literal manner...

And the "fixes" for stuff like..."cloudiness"... are often two things: Acceptance, and the passage of time. Core tenants of our botanical method aquarium game.

Patience. Observation. Objectivity. Mental Shifts.

Thanks for being a part of this exciting, ever-evolving, tinted world!

Stay level-headed. Stay creative. Stay engaged. Stay excited. Stay studious. Stay rebellious!

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Grand experiments? Or, just the way our aquariums are "filtered?"

As a lifelong hobbyist, devoted to natural aquarium systems, the idea of outfitting or setting up my aquariums to facilitate biological processes is second nature. With botanicals in play, the concept of them serving as a medium for biological support is "baked in" to our processes.

And you don't need to invest in all sorts of plastic filter media, blocks, beads, "noodles", etc. to facilitate biological filtration in your botanical method aquarium. I use a lot of "all-in-one" aquariums in my work; that is, aquariums with a rear compartment housing the return pump/heater, with space intended to hold biological media.

I run them empty.

Why?

Because the aquarium itself-or, more specifically- the botanical materials which comprise the botanical-method aquarium "infrastructure" act as a biological "filter system."

In other words, the botanical materials present in our systems provide enormous surface area upon which beneficial bacterial biofilms and fungal growths can colonize. These life forms utilize the organic compounds present in the water as a nutritional source.

Oh, the part about the biofilms and fungal growths sounds familiar, doesn't it?

Let's talk about our buddies, the biofilms, just a bit more. One more time. Because nothing seems as contrary to many hobbyists than to sing the praises of these gooey-looking strands of bacterial goodness!

Structurally, biofilms are surprisingly strong structures, which offer their colonial members "on-board" nutritional sources, exchange of metabolites, protection, and cellular communication. An ingenious natural design. They form extremely rapidly on just about any hard surface that is submerged in water.

When I see aquarium work in which biofilms are considered a "nuisance", and suggestions that it can be eliminated by "reducing nutrients" in the aquarium, I usually cringe. Mainly, because no matter what you do, biofilms are ubiquitous, and always present in our aquariums.

We may not see the famous long, stringy "snot" of our nightmares, but the reality is that they're present in our tanks regardless. Inside every return hose, filter compartment, and powerhead. On every surface, every rock, or piece of wood.

The other reality is that biofilms are something that we as aquarists typically have feared because of the way they look. In and of themselves, biofilms are not harmful to our fishes. They function not only as a means to sequester and process nutrients ( a "filter" of sorts), they also represent a beneficial food source for fishes.

Now, look, I can see rare scenarios where massive amounts of biofilms (relative to the water volume of the aquarium) can consume significant quantities of oxygen and be problematic for the fishes which reside in your tank. These explosions in biofilm growth are usually the result of adding too much botanical material too quickly to the aquarium. They're excaserbated by insufficient oxygenation/circulation within the aquarium.

These are very unusual circumstances, resulting from a combination of missteps by the aquarist.

Typically, however, biofilms are far more beneficial that they are reven emotely detrimental to our aquariums.

Nutrients in the water column, even when in low concentrations, are delivered to the biofilm through the complex system of water channels, where they are adsorbed into the biofilm matrix, where they become available to the individual cells. Some biologists feel that this efficient method of gathering energy might be a major evolutionary advantage for biofilms which live in particularly in turbulent ecosystems, like streams, (or aquariums, right?) with significant flow, where nutrient concentrations are typically lower and quite widely dispersed.

Biofilms have been used successfully in water/wastewater treatment for well over 100 years! In such filtration systems the filter medium (typically, sand) offers a tremendous amount of surface area for the microbes to attach to, and to feed upon the organic material in the water being treated. The formation of biofilms upon the "media" consume the undesirable organics in the water, effectively "filtering" it!

Biofilm acts as an adsorbent layer, in which organic materials and other nutrients are concentrated from the water column. As you might suspect, higher nutrient concentrations tend to produce biofilms that are thicker and denser than those grown in low nutrient concentrations.

it's pretty much a "given" that any botanicals or leaves that you drop into your aquarium will, over time, break down. Wood, too. And typically, before they break down, they'll "recruit" (a fancy word for "acquire') a coating of some rather unsightly-looking growth. Well, "unsightly" to those who have not been initiated into our little world of decomposition, fungal growth, biofilms, tinted water, etc., and maintain that an aquarium by definition is a pristine-looking place without a speck of anything deemed "aesthetically unattractive" by the masses!

And then, of course, there are our other rather slimy-looking friends- the fungi.

Yeah, the stringy stuff that you'll see covering the leaves, botanicals, and wood that you place into your aquarium. Let's talk about why you actually WANT the stuff there in the first place.

The fungi known as aquatic hyphomycetes produce enzymes which break down botanical materials in water. Essentially, they are primary influencers of leaf maceration. They're remarkably efficient at what they do, too. In as little as 3 weeks, as much as 15% of the decomposing leaf biomass in many aquatic habitats is "processed" by fungi, according to one study I found!

Aquatic hyphomycetes play a key role in the decomposition of plant litter of terrestrial origin- an ecological process in rain forest streams that allows for the transfer of energy and nutrients to higher trophic levels.

This is what ecologists call "nutrient cycling", folks.

These fungi colonize leaf litter and twigs and such soon after they're immersed in water. The fungi mineralize organic carbon and nutrients and convert coarse particulate matter into...wait for it...fine particulate organic matter. They also increase leaf litter palatability to shredding organisms (shrimp, insects, some fishes, etc.), which help further facilitate physical fragmentation.

Fungi tend to colonize wood and botanical materials because they offer them a lot of surface area to thrive and live out their life cycle. And cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin- the major components of wood and botanical materials- are easily degraded by fungi, which posses enzymes that can digest and assimilate these materials and their associated organics!

Fungi are regarded by biologists to be the dominant organisms associated with decaying leaves in streams, so this gives you some idea as to why we see them in our aquariums, right?

In aquarium work, we see fungal colonization on wood and leaves all the time. Most hobbyists will look on in sheer horror if they saw the same extensive amount of fungal growth on their carefully selected, artistically arranged wood pieces as they would in virtually any aquatic habitat in Nature!

Yet, it's one of the most common, elegant, and beneficial processes that occurs in natural aquatic habitats!

It's everywhere.

Of course, fungal colonization of wood and botanicals is but one stage of a long process, which occurs in Nature and our aquariums. And, as hobbyists, once we see those first signs of this stuff, the majority of us tend to reach for the algae scraper or brush and remove as much of it as possible- immediately! And sure, this might provide some "aesthetic relief" for some period of time- but it comes right back...because these materials will provide a continuous source of food and colonization sites for fungal growths for some time!

I know that the idea of "circumventing" this stuff is appealing to many, but the reality is that you're actually interrupting an essential, ecologically beneficial natural process. And, as we know, Nature abhors a vacuum, and new growths will return to fill the void, thus prolonging the process.

You want this stuff in your aquariums.

Again, think about the role of aquatic hyphomycetes in Nature.

Fungal colonization facilitates the access to the energy trapped in deciduous leaves and other botanical materials found in tropical streams for a variety of other organisms to utilize.

As we know by now, fungi play a huge role in the decomposition of leaves, both in the wild and in the aquarium. By utilizing special enzymes, aquatic fungi can degrade most of the molecular components in leaves, such as cellulose,, hemicelluloses, starch, pectin and even lignin.

Fungi, although not the most attractive-looking organisms, are incredibly useful...and they "play well" with a surprisingly large number of aquatic life forms to create substantial food webs, both in the wild and in our aquariums!

And it all comes full circle when we talk about "filtration" in our aquariums. Let's come back to this one more time.

People often ask me, "Scott, what filter do you use use in a botanical-method aquarium?" My answer is usually that it just doesn't matter. You can use any type of filter. The reality is that, if allowed to evolve and grow unfettered, the aquarium itself- all of it- becomes the "filter."

You can embrace this philosophy regardless of the type of filter that you employ.

Yeah, my sumps and integrated filter compartments in my A.I.O. tanks are essentially empty.

I may occasionally employ some activated carbon in small amounts, if I'm feeling it- but that's it. The way I see it- these areas, in a botanical-method aquarium, simply provide more water volume, more gas exchange; a place forever more bacterial attachment (surface area), and perhaps an area for botanical debris to settle out. Maybe I'll remove them, if only to prevent them from slowing down the flow rate of my return pumps.

But that's it.

A lot of people are initially surprised by this. However, when you look at it in the broader context of botanical method aquariums as miniature ecosystems, it all really makes sense, doesn't it? The work of these microorganisms and other life forms takes place throughout the aquarium.

The aquarium is the "filter."

The biomass of lifeforms in the aquarium comprise the ecology and physical structure as well.

I recall an experiment I did about 12 years ago; another exploration into letting the ecology within the aquarium- and the aquarium itself- become the "filter."

My dear friend, the late Jake Adams of Reef Builders, came up with what he called the “EcoReef Zero” concept; essentially an approach to keeping coral that eschews the superfluous- gear, live rock, macroalage, sand, etc., in favor of using the coral biomass and the physical aquarium itself as the "filter."

After seeing Jake's work in this area, and lots of discussions with him, I immediately realized that this approach was philosophically unlike anything I had ever attempted before. Yet, it somehow resonated for reasons I could not entirely put together. This approach was developed to focus on creating an excellent environment for corals, providing them with everything that they needed to assure growth and health, and nothing that they didn’t, while keeping things as simple and uncomplicated as possible- aquatic minimalism, if you will.

While in principle the concept of the Zero Reef is ridiculously simple and almost mundane, if you follow the history of modern “reefing” technique, it’s downright “revolutionary” from a philosophical standpoint. So much energy and effort has been expended in recent years attempting to keep corals in high biodiversity, multi-faceted “reef” systems, with all of their competing life forms, that anything else seems on the surface to be almost heretical!

I think a proper description for the approach would be something like “Minimal Diversity Coral Husbandry”. Jake called it “Reduced Ecology Reefing”. It’s sort of the “anti-reef” approach, if you will.

The "Zero Reef" approach essentially distills coral keeping down to its most basic and simple elements, and utilizes minimal technology and energy to achieve success. The premise is simple: Do away with the unnecessary “distractions” of conventional reef aquaria- live rock, sandbeds, macroalage, large fish populations, “cleanup crews”, extensive equipment, etc., and focus solely on the coral, with the bulk of the biomass in the system being contained in the coral tissue itself.

What I only half-jokingly referred to as “revolutionary” about the approach is really the mindset you need to adapt- a reliance on your intuition, a trust in the most basic of skills as a marine aquarist. This differs from the modern convention significantly, because this philosophy really focuses on one element of marine aquarium keeping: The needs of your coral. Indeed, on the coral itself. While there is nothing “wrong” with other, more traditional approaches, by their very nature, they tend to shift focus off of the true “stars” of the aquarium- the corals.

What you want in the "Zero Reef "approach are the beneficial bacterial populations to help break down metabolic waste products, without a huge diversity of other life form to burden the system in any way. In essence, what you’re looking at is a “Petri dish” for coral culture, or the equivalent of a flower in a vase – totally different than any other saltwater experience I’ve ever had.

It is to a conventional reef aquarium what haute couture is to ready-to-wear clothing in the fashion industry: An individual, special aquarium conceived to experiment with simplified coral husbandry. It’s not “your father’s frag tank”. And, it was pretty interesting from an aesthetic standpoint, too! And I think that it's scaleable.

For my “Zero Reef”, I decided to utilize a 4- gallon aquarium, with one side and the bottom painted flat black for aesthetics. My Eco Reef was located on my desk in my office, where I was able to enjoy it all day, every day! The aquarium was equipped with a simple internal filter with media removed, a heater and seven paltry watts of 6700K LED lighting. The setup of the system could not have been easier:

Literally pour water in the aquarium, plug everything in, and you’re under way.

The coral specimen was mounted on a single piece of slate.

Slate was used because the Eco Reef “philosophy” postulates that the porosity of live rock, coupled with the “on board” life that accompanies it, places an excessive burden on a system solely designed to grow coral, and thus detracts from the needs of the corals in the aquarium. Slate has minimal pore structure, primarily on the surface, and does not provide a matrix of nooks and crannies for detritus and nutrients to accumulate. It’s essentially inert, and has little, if any measurable impact on water parameters. Quite frankly, I could have just placed the coral right on the bottom of the aquarium, but the slate does provide a bit of aesthetic interest. I mean, I can’t totally depart from my principles, right?

It really doesn’t get any easier than this: I topped off for evaporation (mere ounces in this 4-gallon aquarium) as needed, and changed 100% of the water every Thursday (not a water exchange, mind you- this was a complete replacement of all of the water in the tank). The maintenance process literally took 5 minutes, and most of that was consumed by putting a towel around the aquarium so I didn't spill on my desk! I fed the coral small quantities of frozen mysis every Tuesday and Wednesday, or when I had the chance.

Probably the most difficult decision of the whole project was deciding what coral to use to serve as the primary inhabitant for the aquarium. The candidate coral had to be one that is fleshy, voluminous, and can safely be placed in a system without sand or rocks. After much consideration, I decided upon a specimen of Green Bubble Coral (Plerogyra simplex) for my test subject.

The piece of coral was approximately 4 inches in length when I started the experiment. Bubble Coral has a reputation for being relatively easy to keep, yet it’s not without its challenges, too. Although Jake recommended Euphyllia, various Faviids, Wellsophyllia, and other corals as ideal candidates for this type of system, I forged ahead with Bubble Coral for the simple reason that I like the way it looks!

The coral’s feeding reactions were immediate- and impressive! The feeding schedule was consistent with the protocol that Jake and I discussed: Feed the coral a couple of days before a water change. This allowed the coral to process and eliminate waste products during that time period, and for me to export as much of the metabolic waste as possible, as quickly as possible.

Being a habitual water changer and nutrient export fiend since my early days in the hobby was a huge asset to me with this approach. Water changes are of critical importance, because they not only export metabolites from this system, but they “reset” the trace elements, minerals, etc. that the coral needs for long-term growth and health. I didn’t dose anything, nor did I test, which was another radical departure from my habits developed over the decades.

Rather, I let the coral “talk” to me, and observed its health carefully. Despite my religious devotion to water testing in reef tanks, I’ve secretly long believed that corals will "tell" you when they are happy, and this approach validated my belief. I can honestly say that I’d never developed such an intimate “relationship” with an individual coral before!

I'd like to try this approach soon with my all-time favorite coral, Pocillopora.

Sure, the "Zero Reef" approach is not the single best way to keep every coral or anemone, and every bare-bottomed, low-diversity aquarium that comes along is not to be enshrined as an affirmation that this is "the best way to keep marine life." In fact, it may not work for some species. The point is, it’s worth investigating and experimenting with. It’s always a good thing to try new technique, new avenues. No matter how simple, or how elementary the approach seems.

I find different ecological approaches to aquarium keeping fascinating. It took a lot of years off observing Nature from not just a "how it looks" standpoint- but from how it works...and synthesizing this information has made me a better hobbyist.

The botanical "method" aquarium is really not a "method." It's literally just Nature, doing Her thing...and us keeping our grubby little hands off of the process!

Eventually, it got through my thick skull that aquariums- just like the wild habitats they represent- have an ecology comprised of countless organisms doing their thing. They depend on multiple inputs of food, to feed the biome at all levels. This meant that scrubbing the living shit (literally) out of our aquariums was denying the very biotia which comprised our aquariums their most basic needs.

That little "unlock" changed everything for me.

Suddenly, it all made sense.

This has carried over into the botanical-method aquarium concept: It's a system that literally relies on the biological material present in the system to facilitate food production, nutrient assimilation, and reproduction of life forms at various trophic levels.

It's changed everything about how I look at aquarium management and the creation of functional closed aquatic ecosystems.

It's really put the word "natural" back into the aquarium keeping parlance for me. The idea of creating a multi-tiered ecosystem, which provides a lot of the requirements needed to operate successfully with just a few basic maintenance practices, the passage of time, a lot of patience, and careful observation.

"Unlocks" are everywhere...the products of our experience, acquired skills, and grand experiments. Stuff that, although initially seemingly trivial, serves to "move the needle" on aquarium practice and shift minds over time,

It's my sincere hope that you will open your mind to the process of experimentation, and share your results with fellow hobbyists as you take your first steps into previously uncharted territory.

Stay bold. Stay provacative. Stay undeterred. Stay curious. Stay humble. Stay diligent...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

This is how I do it.. (pt.3)- Establishing a botanical method aquairum

Last year, I shared the first two installments of what I hope to be an evolving, semi-periodic look at the techniques I employ personally with my botanical method aquariums. I mean, we share all of that stuff now in our social media and blogs, but until this little "series" I've never been done it in a really concise manner. Many of you have asked for this type of piece in "The Tint", and, since Ive been creating some new tanks lately, it's time to get back at it!

Today, let's get back to a pretty fundamental look at what I do, and how I start my botanical method aquariums.The processes and practices, in particular. Remember, this is not the "ultimate guide" about how do to all of this stuff...It's a review of what I do with my tanks. It's not just a strict "how to", of course. It's more than that. A look at what goes through my mind. My philosophy, and the principles which guide my work with my aquariums. I hope you find it helpful.

First off, one of the main things that I do- what I believe most aquarists do- is to have a "theme"- an idea- in mind when I start my tanks. A "North Star", if you will. This is an essential thing; having a "track to run on" guides the entire project. It influences your material and equipment selections, your establishment timetables, and of course, your fish population.

Let's look at my most recent botanical method aquarium as an example of my approach.

First off, I had a pretty good idea of the "theme" to begin with: A "wet season" flooded Amazonian forest. Now, I freely admit that I put a lot of thought into getting the characteristics of the environment and ecology down as functionally realistic as possible, but that the fish selection was far more "cosmopolitan"- consisting of characins- my fave fishes- some of which are found in such habitats, and some which are not. It was not intended to be some competition-minded, highly accurate biotope display.

Just a fun way to feature some of my fave fishes!

Since I was kid, I'd always dreamed of a medium-to-large-sized tank, filled with a large number of different Tetras. This tank would essentially be my "grown-up", more evolved version of my childhood "Tetra fantasy tank!"

The most basic of all "how I do it" lessons is to have some idea about what you're trying to accomplish before you start. In our game, since recreating the environment and ecology are paramount, this will impact every other decision you make.

In this aquarium, the main "structure" of the ecosystem is comprised of a literal "hodgepodge" of "scrap" pieces of wood of different types and sizes that I had laying around. Very little thought was given to specific types or shapes. The idea was to create a representation of an inverted root section and tangle of broken branches from a fallen tree on the forest floor, which becomes an underwater feature during the "wet season."

It was simply a matter of assembling a bunch of smaller pieces to create the look of the inverted root that I had in my head. And once they are down and covered in that "patina" of biocover, it's hard to distinguish one from the other. It looks like one piece, really. Sure, it would have been easier to carefully select just one piece to do it all (would it, though?🤔), but it was more practical to "use what I had" and make it work!

So, another "how I do it" lesson is that you don't always have to incorporate a single specific wood type to have an incredible-looking, interesting physical aquascape. No chasing after the latest and creates trendy wood for me.

I use what I have, or what I like.

You should, too.

Since we're more about function than we are about aesthetics exclusively, which type of wood isn't as important as simply having any wood to complete the job. (and by extension, other "aquascaping materials"...)

After I get my wood pieces the way I like them, it's the usual stuff: Make sure that they stay down before you fill the tank all the way, etc. Nothing exotic here.

The next step is to fill the tank up. Again, there is no real magic here, except to note that, since we're often using sedimented substrate and bits of botanicals on the substrate, it's best to do this very slowly. I mean, your water is likely to be turbid for some time; it's what goes with the territory. However, no need to exacerbate it by rushing!

And, after the tank is about 1/3 full, I'll usually add all of my prepared leaves and botanicals. Why? Because I've found over the years, similar to planted tank enthusiasts, that it's much easier to get the leave and botanicals where you want them by working in a partially filled tank.

Another, hardly revolutionary approach, but one which I think makes perfect sense for what we do.

After the tank is fully filled...that's is where the real fun begins, of course...In our world, the "fun" includes a whole lot of watching and waiting...Waiting for the water to clear up (if you use sedimented substrates). Waiting for Nature to start Her work; to act upon the terrestrial materials that we have added to our tank.

And of course, this is the time when you're busy making sure that you did all of the right things to get the tank ready for "first water."

And of course, it's also the part where every hobbyist, experienced or otherwise, has those lingering doubts; asks questions- goes through the "mental gymnastics" to try to cope: "Do I have enough flow?" "Was my source water quality any good?" "Is it my light?"

And then- when the first fungal filaments or biofilms appear, some new to our specialty still doubt: "When does this shit go away?" "It DOES go away. I know it's just a phase." Right? "Yeah, it goes away..." "When?" "It WILL go away. Right?"

And then there is the realization that this is a BOTANICAL METHOD aquairum, and that you expect and WANT that stuff in your tank. And it will likely never fully "go away..."

But you know this. And yet, you still count a bit.

I mean, it's common with every new tank, really. The doubts. The worries....

The waiting. The not-being-able-to-visualize-a-fully-stocked tank "thing"...Patience-testing stuff. Stuff which I- "Mr. Tinted-water-biofilms-and-decomposing-leaves-and-botanicals-guy"- am pretty much hardened to by now. You will be, too. It's about graciously accepting a totally different "look." Not worrying about "phases" or the ephemeral nature of some things in my aquarium.

Yet, like anyone who sets up an aquarium, I admit that I still occasionally get those little doubts in the dim (tinted?) recesses of my mind now and then- the product of decades of doing fish stuff, yet wondering if THIS is the one time when things WON'T work out as expected...

I mean, it's one of those rights of passage that we all go through when we set up aquariums right? The early doubts. The questioning of ourselves. The reviewing of fundamental procedure and practice. Maybe, the need to reach out to the community to gain reassurance.

It's normal. It's often inevitable.

Do I worry about stuff?

Well, yeah. Of course.

However, it's not at the point in my tank's existence when you'd think that I'd worry. It's a bit later. And it's not about the stuff you might think. It's all about the least "natural" part of my aquariums: The equipment.

Yep.

Usually, for me, this worry manifests itself right around the first water exchange. By that time, you'll likely have learned a lot of the quirks and eccentricities of your new aquarium as it runs. You'll have seen how it functions in daily operation.

And then you do your first deliberate "intervention" in its function. You shut down the pumps for a water exchange.

That's when I clutch. I worry.

I always get a lump in my throat the first time I shut off the main system pump for maintenance. "Will it start right back up? Did I miscalculate the 'drain-down' capacity of the sump? Will this pump lose siphon?"

And so what the fuck if it DOES? You simply...fix the problem. That's what fish geeks do. Chill.

Namaste.

Yet, I worry.

That's literally my biggest personal worry with a new tank, crazy though it might sound. The reality, is that in decades of aquarium-keeping, I've NEVER had a pump not start right back up, or overflowed a sump after shutting down the pump...but I still watch, and worry...and don't feel good until that fateful moment after the first water change when I fire up the pump again, to the reassuring whir of the motor and the lovely gurgle of water once again circulating through my tank.

Okay, perhaps I'm a bit weird, but I'm being totally honest here- and I'm not entirely convinced that I'm the only one who has some of these hangups when dealing with a new tank! I've seen a lot of crazy hobbyists who go into a near depression when something goes wrong with their tanks, so this sort of behavior is really not that unusual, right?

However, our typical "worries" are less "worries" than they are little realizations about how stuff works in these tanks.

In a botanical method aquarium, you need to think more "holistically." You need to realize that these extremely early days are the beginning of an evolution- the start of a living microcosm, which will embrace a variety of natural processes.

But yeah, we know what to expect...We observe.

So, what exactly happens in the earliest days of a botanical method aquarium?

Well, for one thing, the water will gradually start to tint up...

Now, I admit that this is perhaps one of the most variable and unpredictable aesthetic aspects of these types of aquariums- yet one which draws in a lot of new hobbyists to our "tribe." The allure of the tinted water. Many factors, ranging from what kind (and how much) chemical filtration media you use, what types (and how much again!) of botanical materials you're using, and others, impact this. Recently, I've heard a lot of pretty good observation-based information from experienced plant enthusiasts that some plants take up tannins as they grow. Interesting, huh?

Stuff changes. The botanicals themselves begin to physically break down; the speed and the degree to which this happens depends almost entirely on processes and factors largely beyond your control, such as the ability of your microbial population to "process" the materials within your aquarium.

I personally feel that botanical-method aquariums always look better after a few weeks, or even months of operation. When they're new, and the leaves and botanicals are crisp, intact, and fresh-looking, it may have a nice "artistic" appearance- but not necessarily "natural" in the sense that it doesn't look established and alive.

The real magic takes place weeks later.

Things change a bit...

The pristine seed pods and leaves start "softening" a bit. And biofilms and fungal growths make their first appearances.

Mental shifts are required on your part.

Yup, the first mental shift that we have to make as lovers of truly natural style aquariums is an understanding that these tanks will not maintain the crisp, pristine look without significant intervention on our part. And, by "intervention", I mean scrubbing, rinsing, and replacing the leaves and botanicals as needed. I mean, sure- you can do that. I know a bunch of people who do.

They absolutely love super pristine-looking tanks.

Well, to each his own, I suppose. Yet, the whole point of a true botanical method aquarium is to accept the "less than pristine" look and the changes that occur within the system because of natural processes and functions.

I admit, I feel a bit sorry for people who can't make the mental shift to accept the fact that Nature does Her own thing, and that She'll lay down a "patina" on our botanicals, gradually transforming them into something a bit different than when we started.

When we don't accept this process, we sadly get to miss out on Nature guiding our tank towards its ultimate beauty- perhaps better than we even envisioned.

For some, it's really hard to accept this process. To let go of everything they've known before in the hobby. To wait while Nature goes through her growing pains, decomposing, transforming and yeah- evolving our aquascapes from carefully-planned art installations to living, breathing, functioning microcosms.

But, what about all of that decay? That "patina" of biofilm?

If you're struggling with accepting this, just remind yourself regularly that it's okay.

It's normal.

The whole environment of a more established botanical-method aquarium looks substantially different after a few weeks. While the water gradually darkens, those biofilms appear...it just looks more "earthy", mysterious, and alive.

It's a reminder of "Wabi-Sabi" again.

Something that's been on my mind a lot lately.

In it's most simplistic and literal form,the Japanese philosophy of "Wabi Sabi" is an acceptance and contemplation of the imperfection, constant flux and impermanence of all things.

This is a very interesting philosophy, one which was brought to our attention in the aquarium world by none other than the late, great, Takashi Amano, who proferred that a (planted) aquarium is in constant flux; constant transistion- and that one needs to contemplate, embrace, and enjoy the changes, and to relate them to the sweet sadness of the transience of life.

Many of Amano's greatest works embraced this philosophy, and evolved over time as various plants would alternately thrive, spread and decline, re-working and reconfiguring the aquascape with minimal human intervention. Each phase of the aquascape's existence brought new beauty and joy to those would observe them.

Yet, in today's contest-scape driven, break-down-the-tank-after-the-show world, this philosophy of appreciating change by Nature over time seems to have been tossed aside as we move on to the next one.

Sure, this may fit our human lifestyle and interest, but it denies Nature her chance to shine, IMHO. There is something amazing about this process of change; about the way our tanks evolve, and we should enjoy them at every stage.

And then, there is the human desire to "edit" stuff. People ask me all the time if I take stuff out of the system; if I make "edits" and changes to the tank as it breaks in, or as the botanicals start to decompose.

Well, I don't, for reasons we've discussed a lot around here:

Remember, one thing that's unique about the botanical-method approach is that we accept the idea of a microbiome of organisms "working" our botanical materials. We're used to decomposing materials accumulating in our systems. We understand that they act, to a certain extent, as "fuel" for the micro and macrofauna which reside in the aquarium.

I have long been one the belief that if you decide to let the botanicals remain in your aquarium to break down and decompose completely, that you shouldn't change course by suddenly removing the material all at once...

Why?

Well, I think my theory is steeped in the mindset that you've created a little ecosystem, and if you start removing a significant source of someone's food (or for that matter, their home!), there is bound to be a net loss of biota...and this could lead to a disruption of the very biological processes that we aim to foster.

Okay, it's a theory...

But I think it's a good one.

You need to look at the botanical-method aquarium (like any aquarium, of course) as a little "microcosm", with processes and life forms dependent upon each other for food, shelter, and other aspects of their existence. And I really believe that the environment of this type of aquarium, because it relies on botanical materials (leaves, seed pods, etc.), is more signficantly influenced by the amounts and composition of said material.

Just like in natural aquatic ecosystems...

The botanical materials are a real "base" for the little microcosm we create.

And of course, by virtue of the fact that they contain other compounds, like tannins, humic substances, lignin, etc., they also serve to influence the water chemistry of the aquarium, the extent to which is dictated by a number of other things, including the "starting point" of the source water used to fill the tank.

So, in summary- I think the presence of botanicals in our aquariums is multi-faceted, highly influential, and of extreme import for the stability, ecological balance, and efficiency of the tank. As a new system establishes itself, the biological processes adapt to the quantity and types of materials present- the nitrogen cycle and other nutrient-processing capabilities evolve over time as well.

Yes, establishing a botanical method aquarium is as much about making mental shifts and acquiring patience and humility as it is about applying any particular aquarium keeping skills. It's about growing as a hobbyist.

Having faith in yourself, your judgment, and, most important- in the role that Nature Herself plays in our tanks.

In seemingly no time at all, you're looking at a more "broken-in" system that doesn't seem so "clean", and has that wonderful pleasant, earthy smell- and you realize right then that your system is healthy, biologically stable, and functioning as Nature would intend it to. If you don't intervene, or interfere- your system will continue to evolve on a beautiful, natural path.

It's that moment- and the many similar moments that will come later, which makes you remember exactly why you got into the aquarium hobby in the first place: That awesome sense of wonder, awe, excitement, frustration, exasperation, realization, and ultimately, triumph, which are all part of the journey- the personal, deeply emotional journey- towards a successful aquarium- that only a real aquarist understands.

This is how I do it.

Stay excited. Stay bold. Stay observant. Stay brave. Stay curious. Stay patient...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

When we start...

Starting a new botanical method aquarium is an exciting, fun, and interesting time. And the process of creating your aquarium is shockingly easy, decidedly un-stressful, and extremely engaging.

The main ingredients that you need are vision, a bit of knowledge, and... patience.

Bringing your tank from a clean, dry,"static display" to a living, breathing microcosm, filled with life is an amazing process. This, to me is really the most exciting part of keeping botanical method aquariums.

And how do we usually do it?

I mean, for many hobbyists, we've been more or less indoctrinated to rinse the substrate material, age water, arrange wood and rocks, add plants (if that's in your plans), and add fishes. Something like that. And that works, of course. It's the basic "formula" that we've used for over a century in the hobby .

Yet, I'm surprised how we as a hobby have managed to turn what to me is one of the most inspiring, fascinating, and important parts of our aquarium hobby journey into what is more-or-less a "checklist" to be run through- an "obstacle", really- to our ultimate enjoyment of our aquarium.

When you think about it, setting the stage for life in our aquariums is the SINGLE most important thing that we do. If we utilize a different mind set, and deploy a lot more patience for the process, we start to look at it a bit differently.

I mean, sure, you want to rinse sand as clean as possible. You want make sure that you have a piece of wood that's been soaked for a while, and..

Wait, DO you?

I mean, sure, if you don't rinse your sand carefully, you'll get some cloudy water for weeks...no argument there.

And if you don't clean your driftwood carefully, you're liable to have some soil or other "dirt" get into your system, and more tannins being released, which leads to...well, what does it lead to?

Does it lead to some kind of disaster? Does having "dirt" in your tank spell doom for the aquarium?

I mean, an aquarium is not a "sterile" habitat. Let's not fool ourselves.

The natural aquatic habits which we attempt to emulate, although comprised of many millions of times the volumes of water volume and throughput that we have in our tanks- are also typically not "pristine"- right? I mean, soils from the surrounding terrestrial environment carry with them decomposing matter, leaves, etc, all of which impact the chemistry, oxygen-carrying capacity, biological activity, and of course, the visual appearance of the water.

And that's kind of what our whole botanical-method aquarium adventure is all about- utilizing the "imperfect" nature of the materials at our disposal, and fostering and appreciating the natural interactions between the terrestrial and aquatic realms which occur.

Now, granted, the wild aquatic habitats benefit from the dissolution of millions of gallons/liters of throughput, but the processes which impact closed systems are essentially the same ones that influence the wild ecosystems.

Of course, much like Nature, our botanical-method aquariums make use of the "ingredients" found in the abundant materials which comprise the environment. And the "infusion" of these materials into the water, and the resulting biological processes which occur, are what literally make our tanks "come alive."

And yeah, it all starts with the nitrogen cycle...

We can embrace the mindset that every leaf, every piece of wood, every bit of substrate in our aquariums is actually a sort of "catalyst" for sparking biodiversity, function, and yeah, sure- a new view of aesthetics in our aquariums.

I'm not saying that we should NOT rinse sand, or soak wood before adding it to our tanks. What I AM suggesting is that we don't "lose our shit" if our water gets a little bit turbid because we didn't "sterilize" it before adding it, or if there is a bit of botanical detritus accumulating on the substrate in our tank over time. And guess what?

We don't have to start a tank with brand new, right-from-the-bag substrate.

Of course not.

We can utilize some old substrate from another tank (we have done this as a hobby for years for the purpose of "jump starting bacterial growth") for the purpose of providing a different aesthetic as well.

And, you can/should take it further: Use that slightly fungal-covered piece of driftwood or algae-encrusted rock in our brand new tank...This helps foster a habitat more favorable to the growth of the microorganisms, fungi, and other creatures which comprise an important part of our closed aquarium ecosystems.

In fact, in a botanical-method aquarium, facilitating the rapid growth of such biotia is foundational. It's something that we should simply view as an essential part of the startup process.

And from a purely "aesthetic" stanpoint- It's okay for your tank to look a bit "worn" right from the start. This is a definite version of the Amano-embraced Japanese concept of "wabi-sabi"- the acceptance of transience and imperfection.

In fact, I think most of us actually would prefer that! It's okay to embrace this. From a functional AND aesthetic standpoint. Employ good husbandry, careful observation, and common sense when starting and managing your new aquarium.

But don't obsess over "pristine." Especially in those first hours and days.

The aquarium still has to clear a few metaphorical "hurdles" in order to be a stable environment for life to thrive.

I am operating on the assumption (gulp) that most of us have a basic understanding of the nitrogen cycle and how it impacts our aquariums. However, maybe we don’t all have that understanding. My ramblings have been labeled as “moronic” by at least one “critic” before, however, so it’s no biggie for me as said “moron” to give a very over-simplified review of the “cycling” process in an aquarium, so let’s touch on that for just a moment!

During the "cycling" process, ammonia levels will build and then suddenly decline as the nitrite-forming bacteria multiply in the system. Because nitrate-forming bacteria don't appear until nitrite is available in sufficient quantities to sustain them, nitrite levels climb dramatically as the ammonia is converted, and keep rising as the constantly-available ammonia is converted to nitrite.

Once the nitrate-forming bacteria multiply in sufficient numbers, nitrite levels decrease dramatically, nitrate levels rise, and the tank is considered “fully cycled.”

And of course, the process of creating and establishing your aquarium's ecology doesn't end there.

With a stabilized nitrogen cycle in place, the real "evolution" of the aquarium begins. This process is constant, and the actions of Nature in our aquariums facilitate changes.

And our botanical-method systems change constantly.

They change over time in very noticeable ways, as the leaves and botanicals break down and change shape and form. The water will darken as tannins are released. Often, there may be an almost "patina" or haziness to the water along with the tint- the result of dissolving botanical material and perhaps a "bloom" of microorganisms which consume them.

This is perfectly analogous to what you see in the natural habitats of the fishes that we love so much. As the materials present in the flooded forests, ponds, and streams break down, they alter it biologically, chemically, and even physically.

It's something that we as aquarists have to accept in our tanks, which is not always easy for us, right? Decomposition, detritus, biofilms- all that stuff looks, well- different than what we've been told over the years is "proper" for an aquarium. And, it's as much a perception issue as it is a husbandry one. I mean, we're talking about materials from decomposing botanicals and wood, as opposed to uneaten food, fish waste, and such.

I love that more and more hobbyists are grasping this concept. What's really cool about this is that, in our community, we aren't seeing hobbyists freak out over some of the aesthetics previously associated with "dirty!"

It's fundamental.

The understanding that we are helping to foster an ecosystem- not just "setting up an aquarium" changes your perspective entirely.

And soon after your tank begins operation, you'll see the emergence of elegant, yet simple life forms, such as bacterial biofilms and fungal growths. We've long maintained that the appearance of biofilms and fungi on your botanicals and wood are to be celebrated- not feared. They represent a burgeoning emergence of life -albeit in one of its lowest and (to some) most unpleasant-looking forms- but that's a really big deal!

Biofilms form when bacteria adhere to surfaces in some form of watery environment and begin to excrete a slimy, gluelike substance, consisting of sugars and other substances, that can stick to all kinds of materials, such as- well- in our case, botanicals. It starts with a few bacteria, taking advantage of the abundant and comfy surface area that leaves, seed pods, and even driftwood offer.

The "early adapters" put out the "welcome mat" for other bacteria by providing more diverse adhesion sites, such as a matrix of sugars that holds the biofilm together. Since some bacteria species are incapable of attaching to a surface on their own, they often anchor themselves to the matrix or directly to their friends who arrived at the party first.

We've long called this period of time when the biofilms emerge, and your tank starts coming alive "The Bloom"- a most appropriate term, and one that conjures up a beautiful image of Nature unfolding in our aquariums- your miniature aquatic ecosystem blossoming before your very eyes!

We see this "bloom" of life in botanical method aquariums, and we also see it in my beloved reef tanks as well...a literal explosion of lower life forms, creating the microcosm which supports all of the life in the aquairum.

The real positive takeaway here:

Biofilms are really a sign that things are working right in your aquarium! A visual indicator that natural processes are at work, helping forge your tank's ecosystem.