- Continue Shopping

- Your Cart is Empty

Where the magic lies...

The botanical method aquarium niche is a bit weird, isn't it? Collectively, companies in our space tend to speculate a lot.

We make claims.

And we make recommendations..

And at best, they’re subjective guesses. Based upon our personal experince and perhaps the experiences of others.

Yet, wherever you turn in the botanical method aquarium world, speculation and generalizations are, well- rampant. How much tannin or other compounds are in a given botanical is, without very specific bioassays and highly specialized equipment- simply a guess on our part.

There is absolutely no proof or quantification of these assertions that is grounded in hard facts or rigorous, scientific research. I think about it a lot..For us to make recommendations based on concentrations of various compounds in a given botanical is simply irresponsible and not grounded in fact.

There is a lot of speculation. So-called "experts" in our area of specialization have, in all likelihood, done little beyond use the materials avialbel to us in aquairums. I'm not aware of anyone in our niche who runs a lab, or has performed disciplined scientific analysis on any of the materials that we as a hobby use every day.

This is not an "indictment" or secret reveal about our industry...it's just the way things are.

One of the things that we assert the most is "how much tannins" are in a given material. Okay...What is this based upon?

Generally, it's based upon the admittedly superficial observations that we make as hobbyists and "power users" of botanical materials. There are not awhole lot of other, more insightful observations that we CAN make, right?

Sure, we could tell you that, based upon our experience, a given wood type or seed pod will color the water a darker color than another.. but what does that mean, really?

Not that much.

I mean color of the water is absolutely not an indication of anything- other than the fact that tint producing types of tannins are present. It doesn’t tell you what the pH, dKH, or TDS of the water.. let alone, how much of what tannins are present…

Now, sure, it’s arguably correct that “tannins” are present in many botanical materials. However, the degree to which the tannins present in a given botanical or leaf can influence water chemistry is really speculative. Quite honestly, other than staining the water a distinctive brown color, it’s actually not entirely known by science what other influences that specific tannins impart to water.

So, to be quite honest, when we make general statements like “contains a lot of tannins” or “can lower pH”, many times we’re simply “spitballing…” Guessing. Assuming.

Now, don't get me wrong. I'm not trying to trash the many responsible, experienced vendors in our space. I am, however, attempting to make the point that a large part of what we assert about the materials we work with and sell is, well- speculative.

We make claims.

And we make recommendations..

I think the main thing which keeps the idea from really developing more in the hobby- knowing exactly how much of what to add to our tanks, specifically to achieve "x" effect- is that we as hobbyists simply don't have the means to test for many of the compounds which may affect the aquarium habitat.

At this point, it's really as much of an "art" as it is a "science", and more superficial observation- at least in our aquariums- is probably almost ("almost...") as useful as laboratory testing is in the wild. Even simply observing the effects upon our fishes caused by environmental changes, etc. is useful to some extent.

At least at the present time, we're largely limited to making these sort of "superficial" observations about stuff like the color a specific botanical can impart into the water, etc. It's a good start, I suppose.

Of course, not everything we can gain from this is superficial...some botanical materials actually do have scientifically confirmed impacts on the aquarium environment.

In the case of catappa leaves, for example, we can at least infer that there are some substances (flavonoids, like kaempferol and quercetin, a number of tannins, like punicalin and punicalagin, as well as a suite of saponins and phytosterols) imparted into the water from the leaves- which do have scientifically documented affects on fish health and vitality.

So, there's that.

The one area that we are not speculating or guessing is the ecology part. How botanical materials interact with the aquatic environment to form an ecosystem of organisms. And the most fundamental, most important "driver" of the whole thing is the process of decomposition.

Decomposition is how Nature processes botanical materials for use by the greater aquatic ecosystem. It's the first part of the recycling of nutrients that were used by the plant from which the botanical material came from. When a botanical decays, it is broken down and converted into more simple organic forms, which become food for all kinds of organisms at the base of the ecosystem.

In aquatic ecosystems, much of the initial breakdown of botanical materials is conducted by detritivores- specifically, fishes, aquatic insects and invertebrates, which serve to begin the process by feeding upon the tissues of the seed pod or leaf, while other species utilize the "waste products" which are produced during this process for their nutrition.

In these habitats, such as streams and flooded forests, a variety of species work in tandem with each other, with various organisms carrying out different stages of the decomposition process.

And it all is broken down into three distinct phases identified by ecologists.

It goes something like this:

A leaf falls into the water.

After it's submerged, some of the "solutes" (substances which dissolve in liquids- in this instance, sugars, carbohydrates, tannins, etc.) in the leaf tissues rather quickly. Interestingly, this "leaching stage" is known by science to be more of an artifact of lab work (or, in our case, aquarium work!) which utilizes dried leaves, as opposed to fresh ones.

Fresh leaves tend to leach these materials over time during the breakdown/decomposition process. It makes sense, because freshly fallen or disturbed leaves will have almost their full compliment of chlorophyll, sugars, and other compounds present in the tissues. (Hmm, a case for experimenting with "fresh" leaves? Perhaps? We've toyed with the idea before. Maybe we'll re-visit it?)

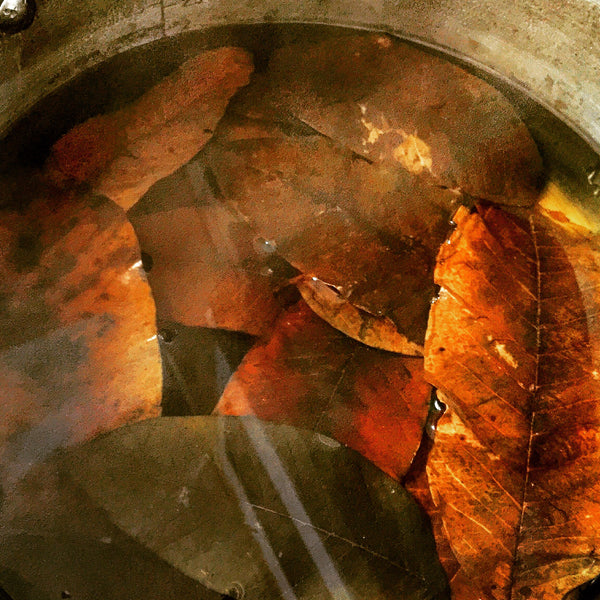

Cool experiments aside, this is yet another reason why it's not a bad idea to prep your leaves, because it will help quickly leach out many of the remaining sugars and such which could degrade water quality a bit in closed systems.

The second stage of the process is called the "conditioning phase", in which microbial colonization on the leaf takes place. They begin to consume some of the tissues of the leaf- at least, softening it up a bit and making it more palatable for the aforementioned detritivores. This is, IMHO, the most important part of the process. It's the "main event"- the part which we as hobbyists embrace, because it leads to the development of a large population of organisms which, in addition to processing and exporting nutrients, also serve as supplemental food for our fishes!

The last phase, "fragmentation", is exactly what it sounds like- the physical breakdown of the leaf by various organisms, ranging from small crustaceans and shrimp to fungi- and even fishes, collectively known as "shredders." It has been suggested by some ecologists that microbes might be more important than "shredders" in tropical streams.

Fauna composition differs between habitats, yet most studies I've found will tell you that Chironomidae ( insect larvae-think Bloodworms!) are the most abundant in many streams, pools, flooded forests, and "riffles" in the initial period of leaf breakdown!

The botanical material is broken down into various products utilized by a variety of life forms. The particles are then distributed downstream by the current and are available for consumption by a variety of organisms which comprise aquatic food webs.

Six primary breakdown products are considered in the decomposition process: bacterial, fungal and shredder biomass; dissolved organic matter; fine-particulate organic matter; and inorganic mineralization products such as CO2, NH4+ and PO43-.

An interesting fact: In tropical streams, a high decomposition rate of terrestrial materials has been correlated to high fungal activity...these organisms accomplish a LOT!

Interestingly, scientists have noted that the leaves of many tropical plant species tend to have higher concentrations of secondary compounds and more recalcitrant compounds than do leaves of temperate species. Why do you suppose this is?

Also, some researchers hypothesized that high concentrations of secondary compounds (like tannins) in many tropical species inhibit leaf breakdown rates in tropical streams...that may be why you see leaf litter beds that last for many years and become known features in streams and river tributaries!

There's a whole lot of stuff going on in the litter beds of the world, huh?

Of course, fungal colonization of wood and botanicals is but one stage of a long process, which occurs in Nature and our aquariums. And, for many hobbyists, once we see those first signs of fungal growths or biofilms, the majority of us tend to reach for the algae scraper or brush and remove as much of it as possible- immediately! And of course, this provides some "aesthetic relief" for some period of time- but it comes right back...because botanical materials will provide a continuous source of food and colonization sites for fungal growths!

And the idea of "circumventing" this stuff is appealing to many, but the reality is that you're actually interrupting the process. It's not a "phase" that your botanical method aquarium goes through. Rather, it's how the aquarium functions on a continuous basis. Siphon the stuff out- and it comes right back. Nature abhors a vacuum, and new growths will return to fill the void, thus prolonging the process.

Why fight it?

Alteration of the botanicals durning the decomposition process is done chemically via this microbial action; ultimately, the components of the botanicals/leaves (lignin, cellulose, etc.) are broken down near completely. In aquatic environments, photosynthetic production of oxygen ceases in plants, and organic matter and nutrients are released back into the aquatic environment.

All of these organisms work together- in essence, supporting each other via the processes which they engage in.

And, decomposition is a dynamic, fascinating process- part of why we find the idea of a natural, botanical-method system so compelling. Many of the organisms- from microbes to micro crustaceans to fungi- are almost never seen except by the most observant and keen-eyed hobbyist...but they're there- doing what they've done for eons.

They work slowly and methodically over weeks and months, converting the botanical material into forms that are more readily assimilated by themselves and other aquatic organisms.

The real cycle of life!

The ultimate result is the transformation to what ecologists call "coarse particulate organic matter" (C.P.O.M.) into "fine particulate organic matter" (F.P.O.M.), which may constitute an important food source for other organisms we call “deposit feeders” (aquatic animals that feed on small pieces of organic matter that have drifted down through the water and settled on the substrate) and “filter feeders” (animals that feed by straining suspended organic matter and small food particles from water).

And yeah, insect larvae, fishes and shrimp help with this process by grazing among or feeding directly upon the decomposing botanical materials..So-called "shredder" invertebrates (shrimps, etc.) are also involved in the physical aspects of leaf litter breakdown.

There's a lot of supplemental food production that goes on in leaf litter beds and other aggregations of decomposing botanical materials. It's yet another reason why we feel that aquariums fostering significant beds of leaves and botanicals offer many advantages for the fishes which reside in them!

The biggest allies we have in the process of decomposition of our botanicals in the aquarium are the smallest organisms: Microbes (bacteria, fungi, and protozoa, specifically)!

Interestingly, in some wild aquatic habitats, such as the famous Peat swamps of Southeast Asia, the decomposition of leaves which fall into these waters is remarkably slow. In fact, ecologists have observed that the leaves typically do not break down.

Why?

It's commonly believed that these low nutrient waters, which are high in tannins, and highly acidic, seem to impede microbial activity. This is seemingly at odds with the understanding that passive leaching of dissolved organic compounds (DOC) from leaf litter has been found to be a major source of energy in tropical stream habitats, fueling the microbial food chains which we are so fascinated by.

No doubt the water parameters have something to do with this. These are unique habitats. Here are a few stats from the peat swamps in which some studies on leaf decomposition were conducted:

Water temperature: 25C/77F-32C/89F

pH: 2.6-3.8

TDS: 89-134mg/l

Nitrate: <0.-0.2mg/l

Dissolved oxygen: 1.8-16mg/l

In the studies, leaves of native species found along the swamps submerged in the waters of the swamps lost very little biomass, which other leaves from trees did break down more substantially. This tends to rule out the generally-held theory that ecologists have which postulates that the slow decomposition rate in the peat swamps is due to the extreme conditions. Rather, as mentioned above, it's believed that the resistance to decomposition is due to the physical and chemical properties of the leaves which are found right along the swamps.

(image by Marcel Silvius)

The reason? Well, think about it.

Leaf litter in tropical peat swamp forests builds up into peat many feet deep over thousands of years, and thus impedes nutrient cycling. And when you think about it, inputs of nutrients into most peat swamps come solely from rainfall, because rivers and streams in the region don't always flow into the swamps. In such nutrient poor, highly acidic conditions, it is more beneficial for plants to protect their leaves, rather than to replace them when subjected to elements like wind, and herbivore damage (mostly by insects) with new growth.

And interestingly, bacteria and fungi are known to be responsible for leaf breakdown in the peat swamps, because ecologists typically don't encounter aquatic invertebrates in the peat swamp which are known to ingest leaf material!

Our friends, the fungi!

Yeah, those guys again. Yet, there just one group of a diverse biome of organisms which contribute to the function of our botanical method aquariums.

By studying and encouraging the growth of this diversity of organisms, and creating a multi-faceted microcosm of life in our tanks, I believe that we are contributing to an exciting progression of the art and science of aquarium keeping!

I'm fascinated by the "mental adjustments" that we need to make to accept the aesthetic and the processes of natural decay, fungal growth, the appearance of biofilms, and how these life forms affect what's occurring in the aquarium.

It's all a complex synergy of life and aesthetic.

And we have to accept Nature's input here.

Nature dictates the speed by which this decomposition process occurs. We set the stage for it- but Nature is in full control.

Nuance. Art. Challenge. Fascination.

Beyond the pretty looks. That's where the real magic lies.

Stay engaged. Stay curious. Stay dedicated. Stay observant. Stay open-minded...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

It's not "dirty"- it's perfect.

We receive a lot of questions about the maintenance of botanical-method aquariums. And it makes a lot of sense, because the very nature of these aquariums is that they are stocked, chock-full of seed pods and leaves, all of which contribute to the bio load of the aquarium- all of which are in the process of breaking down and decomposing to some degree at any given moment.

It's not so much if you have to pay attention to maintenance with these tanks- it's more of a function of how you maintain them, and how often. Well, here's the "big reveal" on this:

Keep the environment stable.

Environmental stability is one of the most important- if not THE most important- things we can provide for our fishes! To me, it's more about doing something consistently than it is about some unusual practice done once in a while.

Like, ya' know- water exchanges.

Obviously, water exchanges are an important part of any aquarium husbandry regimen, and I favor a 10% weekly exchange. Iit's the regimen I've stuck with for decades, and it's never done me wrong. I think that with a botanical influenced aquarium, you've got a lot of biological material in there in addition to the fishes (you know, like decomposing leaves and softening seed puds- stuff like that), and even in well-managed, biologically-balanced aquarium, you still want to minimize the effects of any organics accumulating in a detrimental manner.

This piece is not really about water changes, and frankly, you can utilize whatever schedule/precentage works for you. The 10% weekly has worked for me; you may have some other schedule/percentage. My advice: Just do what works and adjust as needed.

Enough said.

Of course, the other question I receive all the time about botanical method aquairums is, "Do you let the leaves decompose completely in your tank, or do you remove them?"

I have always allowed leaves and botanicals to remain in my system until they completely decompose.

This is generally not a water-quality-affecting issue, in my experience, and the decision to remove them is more a matter of aesthetic preferences than function. There are likely times when you'll enjoy seeing the leaves decompose down to nothing, and there are other times when you might like a "fresher" look and replace them with new ones relatively soon.

It's your call.

However, I believe that the benefits of allowing leaves and botanicals to remain in your aquariums until they fully decompose outweigh any aesthetic reservations you might have. A truly natural functioning-and looking- botanical method aquarium has leaves decomposing at all times. There are, in my opinion, no downsides to keeping your botanical materials "in play" indefinitely.

I have never had any negative side effects that we could attribute to leaving botanicals to completely break down in an otherwise healthy, well-managed aquarium.

And from a water chemistry perspective?

Many, many hobbyists (present company included) see no detectable increases in nitrate or phosphate as a result of this practice.

Of course, this has prompted me to postulate that perhaps they form a sort of natural "biological filtration media" and actually foster some dentritifcation, etc. I have no scientific evidence to back up this theory, of course (like most of my theories, lol), other than my results, but I think there might be a grain of truth here!

Remember: A truly "Natural" aquarium is not sterile. It encourages the accumulation of organic materials and other nutrients- not in excess, of course.

The love of pristine, sterile-looking tanks is one of the biggest obstacles we need to overcome to really advance in the aquarium hobby, IMHO. Stare at a healthy, natural aquatic habitat for a bit and tell me that it's always "pristine-looking..."

Lose the "clean is the ultimate aesthetic" mindset. Please.

"Aesthetics first" has created this weird dichotomy in the hobby.

Like, people on social media will ooh and awe when pics of beautiful wild aquatic habitats- many of which absolutely looked nothing like what we do in aquariums- are shared. They'll comment on how amazing Nature is, and admire the leaf litter and tinted water and stuff.

Yet, when it comes time to create an aquarium, they'll almost always "opt out" of attempting to create such a tank in their own home, and instead create a surgically-sterile aquatic art piece instead.

Like, WTF?

Why is this?

I think it's because we've been convinced by...well, almost everybody in the hobby- that it's not advisable or practical- or even possible- to create a truly functional natural aquarium system. It's easier to look for the sexiest named rock and designer wood and mimic some "award winning" 'scape instead.

Ouch.

I think that many hobbyists have lost sight of the fact that there are enormous populations of organisms which reside in their aquariums which process, utilize, and assimilate the waste materials that everyone is so concerned about. We eschew natural methods in place of technology, because it's in our minds that "natural methods" = "aesthetically challenged."

So we go for expensive filters...We've become convinced that technology is our salvation.

The reality is that a convergence of simple technology and embracing of fundamental ecology is what make successful aquariums- well-successful. In many cases (notice the caveat "many"...) you don't need a huge-capacity, ultra-powerful high-priced filter to keep your tank healthy. You don't need massive water exchanges and ultra meticulous water exchange/siphoning sessions to sustain your aquarium for indefinite periods of time.

What you need is a combination of a decent filter system, a regular schedule of small simple water exchanges, and a healthy and unmolested microbiome of beneficial organisms within your aquarium.

Let Nature do Her thing.

Biofilms, fungi, algae...detritus...all have their place in the aquarium. Not as an excuse for lousy or lazy husbandry- but as supplemental food sources which also happen to "power" the ecology in our tanks.

Let's just focus on our BFFs, the fungi, for a few more minutes. We've given them love for years here...long before hashtags like "#fungal Friday "or whatever became a "thing" on The 'Gram.

And of course, as we've discussed many times here, fungi are actually an important food item for other life forms in the aquatic environments tha we love so much! In one study I stumbled across, gut content of over 100 different aquatic insects collected from submerged wood and leaves showed that fungi comprised part of the diet of more than 60% of them, and, in turn, aquatic fungi were found in gut content analysis of many species of fishes!

One consideration: Bacteria and fungi that decompose decaying plant material in turn consume dissolved oxygen for respiration during the process.

This is one reason why we have warned you for years that adding a huge amount of botanical material at one time to an established, stable aquarium is a recipe for disaster. There is simply not enough fungal growth or bacteria to handle it. They reproduce extremely rapidly, consuming significant oxygen in the process.

Bad news for the impatient.

So just be patient. Learn. Embrace this stuff.

Support. Co-dependency. Symbiosis. Whatever you want to call it- the presence of fungi in aquatic ecosystems is extremely important to other organisms.

You can call it free biological filtration for your aquarium!

In the botanical-method aquarium, ecology is 9/10's of the game. Think about this simple fact:

The botanical materials present in our systems provide enormous surface area upon which beneficial bacterial biofilms and fungal growths can colonize. These life forms utilize the organic compounds present in the water as a nutritional source.

GREAT news for the patient, the studious, and the accepting.

Think about this: These life forms arrive on the scene in Nature, and in our tanks, to colonize appropriate materials, to process organics in situ on the things that they're residing upon (leaves, twigs, branches, seed pods, wood, etc.).

So removing it is, at best, counterproductive.

Yeah, if you intervene by removing stuff, bad things can happen. Like, worse things than just a bunch of gooey-looking fungal and biofilm threads on your wood. Your aquarium suddenly loses its capability of processing the leaves and associated organics, and- who's there to take over?

Okay, I'm repeating myself here- but there is so much unfounded fear and loathing over aquatic fungi that someone has to defend their merits, right? Might as well be me!

My advice; my plea to you regarding fungal growth in your aquarium? Just leave it alone. It will eventually peak, and ultimately diminish over time as the materials/nutrients which it uses for growth become used up. It's not an endless "outbreak" of unsightly (to some) fungal growth all over your botanicals and leaves.

It goes away significantly over time, but it's always gonna be there in a botanical method aquarium.

"Over time", by the way is "Fellman Speak" for "Please be more fucking patient!"

Seriously, though, hobbyists tend to overly freak out about this kind of stuff. Of course, as new materials are added, they will be colonized by fungi, as Nature deems appropriate, to "work" them. It keeps going on and on...

It's one of those realities of the botanical-method aquarium that we humans need to wrap our heads around. We need to understand, lose our fears, and think about the many positives these organisms provide for our tanks. These small, seemingly "annoying" life forms are actually the most beautiful, elegant, beneficial friends that we can have in the aquarium. When they arrive on the scene in our tanks, we should celebrate their appearance.

Why?

Because their appearance is yet another example of the wonders of Nature playing out in our aquariums, without us having to do anything of consequence to facilitate their presence, other than setting up a tank embracing the botanical method in the first place. We get to watch the processes of colonization and decomposition occur in the comfort of our own home. The SAME stuff you'll see in any wild aquatic habitat worldwide.

Amazing.

And the end result of the work of fungal growths, bacteria, and grazing organisms?

Detritus.

"Detritus is dead particulate organic matter. It typically includes the bodies or fragments of dead organisms, as well as fecal material. Detritus is typically colonized by communities of microorganisms which act to decompose or remineralize the material." (Source: The Aquarium Wiki)

Well, shit- that sounds bad!

It's one of our most commonly used aquarium terms...and one which, well, quite frankly, sends shivers down the spine of many aquarium hobbyists. And judging from that definition, it sounds like something you absolutely want to avoid having in your system at all costs. I mean, "dead organisms" and "fecal material" is not everyone's idea of a good time, ya know?

Literally, shit in your tank, accumulating. Like, why would anyone want this to linger- or worse- accumulate- in your aquarium?

Yet, when you really think about it and brush off the initial "shock value", the fact is that detritus is an important part of the aquatic ecosystem, providing "fuel" for microorganisms and fungi at the base of the food chain in aquatic environments. In fact, in natural aquatic ecosystems, the food inputs into the water are channeled by decomposers, like fungi, which act upon leaves and other organic materials in the water to break them down.

And the leaf litter "community" of fishes, insects, fungi, and microorganisms is really important to these systems, as it assimilates terrestrial material into the blackwater aquatic system, and acts to reduce the loss of nutrients to the forest which would inevitably occur if all the material which fell into the streams was simply washed downstream!

That sounds all well and good; even grandiose, but what are the implications of these processes- and the resultant detritus- for the closed aquarium system?

Is there ever a situation, a place, or a circumstance where leaving the detritus "in play" is actually a benefit, as opposed to a problem?

I think so. Like, almost always.

In years past, aquarists who favored "sterile-looking" aquaria would have been horrified to see this stuff accumulating on the bottom, or among the hardscape. Upon discovering it in our tanks, it would have taken nanoseconds to lunge for the siphon hose to get this stuff out ASAP!

In our world, the reality is that we embrace this stuff for what it is: A rich, diverse, and beneficial part of our microcosm. It provides foraging, "Aquatic plant "mulch", supplemental food production, a place for fry to shelter, and is a vital, fascinating part of the natural environment.

It is certainly a new way of thinking when we espouse not only accepting the presence of this stuff in our aquaria, but actually encouraging it and rejoicing in its presence!

Why?

Well, it's not because we are thinking, "Hey, this is an excuse for maintaining a dirty-looking aquarium!"

No.

We rejoice because our little closed microcosms are mimicking exactly what happens in the natural environments that we strive so hard to replicate. Granted, in a closed system, you must pay greater attention to water quality, but accepting decomposing leaves and botanicals as a dynamic part of a living closed system is embracing the very processes that we have tried to nurture for many years.

And it all starts with the 'fuel" for this process- leaves and botanicals. As they break down, they help enrich the aquatic habitat in which they reside. Now, in my opinion, it's important to add new leaves as the old ones decompose, especially if you like a certain "tint" to your water and want to keep it consistent.

However, there's a more important reason to continuously add new botanical materials to the aquarium as older ones break down:

The aquarium-or, more specifically- the botanical materials which comprise the botanical-method aquarium "infrastructure" acts as a biological "filter system."

In other words, the botanical materials present in our systems provide enormous surface area upon which beneficial bacterial biofilms and fungal growths can colonize. These life forms utilize the organic compounds present in the water as a nutritional source.

Think about that concept for a second.

It's changed everything about how I look at aquarium management and the creation of functional closed aquatic ecosystems.

It's really put the word "natural" back into the aquarium keeping parlance for me. The idea of creating a multi-tiered ecosystem, which provides a lot of the requirements needed to operate successfully with just a few basic maintenance practices, the passage of time, a lot of patience, and careful observation.

It takes a significant mental shift to look at some of this stuff as aesthetically desirable; I get it. However, for those of you who make that mental shift- it's a quantum leap forward in your aquarium experience.

It means adopting a different outlook, accepting a different, yet very beautiful aesthetic. It's about listening to Nature instead of the asshole on Instagram with the flashy, gadget-driven tank. It's not always fun at first for some, and it initially seems like you're somehow doing things wrong.

It's about faith. Faith in Mother Nature, who's been doing this stuff for eons. Mental "unlocks" are everywhere...the products of our experience, acquired skills, and grand experiments. Stuff that, although initially seemingly trivial, serves to "move the needle" on aquarium practice and shift minds over time.

A successful botanical method aquarium need not be a complicated, technical endeavor; rather, it should rely on a balanced combination of knowledge, skill, technology, and good judgement. Oh- and a bunch of "mental shifts!"

Take away any one of those pieces, and the whole thing teeters on failure.

Utilize all of these things to your advantage and enjoy your hobby more than ever!

Remember, your botanical method aquarium isn't "dirty."

It's perfect.

Just like Nature intended it to be.

Stay bold. Stay grateful. Stay thoughtful. Stay curious. Stay diligent...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Something old. Something new. Something gone.

Over the years, I've revisited a lot of old ideas.

Sometimes, my mindset deviates from long-held beliefs. Sometimes, it's a permanent shift. Other times, it's just long enough to realize that my new-found love for something just isn't me being my "authentic self."

Rather, an infatuation of sorts, based on an idea that doesn't; really represent what I believe in.

One of our recent products which really brings this idea home was sachets of selected, crushed botanicals, intended to create some of the effects of a botanical method aquarium without the "hassle" of using actual botanicals in your tanks. It was different than the usual teabag-type products out there because our formulation was from botanical materials, not simply crushed leaves like everyone else did.

It seemed like a good idea at the time. A lot of hobbyists wanted a "tinted aquairum" without the decomposing botanicals and all that their use entails. We had very sexy packaging and a great name for it, "Shade."

It sold out quickly several times. Our supplier in Southeast Asia who made it for us was thrilled. Stores wanted to stock it. As a marketer, I was pleased...But something about it always sort of bothered me. It somehow felt "dirty" to me. I mean, it was a cool product, I guess- but it kind of went against some of the very principles I have preached for years...And because ours was made form botanicals, not leaves, like everyone else's, the "results" (ie; color effects) were highly variable and rather inconsistent from batch to batch. Too inconsistent for a product designed to be a "quick fix" should be.

And why the hell was I offering a "quick fix" product, anyways?

So, the last time it sold out, I decided to wait on restocking it...and wait even longer.

Then I really thought about it during my "sabbatical."

And I decided to retire it. Kill it.

Why?

It was a "hack."

You know that, historically, I have a great disdain for "hacks" in our hobby...

Sometimes, our shared progression and experience even makes me think about my own personal "rules" and directives. Pushing outwards has really helped me grow in the hobby.

Every once in a while, I'll have a friend contact me about something that I'm "missing out on" or some new "thing" that will "change the game" and perhaps be an "existential threat" to Tannin Aquatics. I certainly appreciate that, but it's okay. (As I've learned over the years- particularly in recent months-the biggest threat to Tannin, really, is me, lol.)

Of course, as part of my "due diligence" as a business owner, I DO take note and check out the "thing" which is pointed out to me -whatever it might be-and see what it's all about.

And, to be honest, like 9 times out of 10, it's usually a link to a a new vendor who sells some of the same materials that we do, yet making outrageous claims about what they do, or link to a forum discussion about people collecting their own botanicals (which I've encouraged from day one of our existence and still do...), or a discussion about using some "extract" or "solution" to create "blackwater" easily as an alternative to leaves or what not. A "hack" of some sort.

Hacks. Yuck.

And the products? Usually, they're nothing that novel. Same stuff. Just perhaps, with a cool name or packaging (ya know...like "Shade" 😂)

Of course, these "products"-often "extracts" and "additives"- almost always tend to be derivations of things we've done for a generation or two in the hobby, and are no better-or worse- than the idea of tossing leaves and botanicals in the aquarium, in terms of what they appear to do on the surface.

And it almost always seems to me that these "solutions" are simply an alternative of sorts; generally one which requires less effort or process to get some desired result. Of course, they also play into one of the great aquarium hobby "truisms" of the 21st century:

We hate waiting for stuff. We love "hacks" and shortcuts. We're impatient.

Me? I'm about the process. My philosophy is that the "aesthetics" always follow the function of what we do in the botanical method.

And I'm really fucking patient.

I've had tanks sit with leaves and substrate for months before adding the fishes I've been looking for. I've also "pre-stocked" botanical method and reef tanks with microorganism cultures and let them stay "fishless" for months while a population assembled itself.

I'm okay with that.

I'm not impatient.

Impatience is, I suppose, part of being human, but in the aquarium hobby, it occasionally drives us to do things that, although are probably no big deal- can become a sort of "barometer" for other things which might be of questionable value or risk. ("Well, nothing bad happened when I did THAT, so, if I do THIS...") Or, they can cumulatively become a "big deal", to the detriment of our tanks. Others are simply alternatives, and are no better or worse than what we're doing with botanicals, at least upon initial investigation.

Yeah, most of these solutions and teas and teabags (like "Shade!")- although I suppose seen by many as an "alternative"- are hacks.

Now, for a lot of reasons, I fucking hate most "hacks" that we use in the hobby.

To many, "hacking" it implies a sort of "inside way" of doing stuff...a "work-around" of sorts. A term brought about by the internet age to justify doing things quickly and to eliminate impatience because we're all "so busy." I think it's a sort of sad commentary on the prevailing mindset of many people.

We all need stuff quickly...We want a "shortcut to our dream tank. "Personally, I call it "cheating."

Yes.

With what we do, a "hack" really is trying to cheat Nature. Speed stuff up. Make nature work on OUR schedules. We justify it by saying that it's an alternative, or by reminding ourselves (as we did with "Shade") that it's "made from natural materials..."

Anything to make ourselves feel better about trying to do an "end run" around Nature.

Bad idea, if you ask me.

Of course, there are some hacks, like the one we're discussing here, which aren't necessarily "bad" or harmful- just different. There is absolutely nothing wrong with doing them. Yet, they deny us some pleasures and opportunities to learn more about the way Nature works. And we can't fool ourselves into believing that they are some panacea, either.

The idea just doesn't resonate with some of us. Like the use of botanical sachets such as "Shade" or whatever.

The other one that seems to come up at least a few times a year in discussion, and is often proferred to me as rendering the botanical-method aquarium "obsolete" is the use of...tea.

Like, legit, human-consumable tea.

If you haven't heard of it before, there is this stuff called Rooibos tea, which, in addition to bing kind of tasty, has been a favored "tint hack" of many hobbyists for years. Without getting into all of the boring details, Rooibos tea is derived from the Aspalathus linearis plant, also known as "Red Bush" in South Africa and other parts of the world.

(Rooibos, Aspalathus linearis. Image by R.Dahlgr- used under CC-BY S.A. 2.5)

It's been used by fish people for a long time as a sort of instant "blackwater extract", and has a lot going for it for this purpose, I suppose. Rooibos tea does not contain caffeine, and and has low levels of tannin compared to black or green tea. And, like catappa leaves and other botnaicals, it contains polyphenols, like flavones, flavanols, aspalathin, etc.

It's kind of tasty, too!

Hobbyists will simply steep it in their aquariums and get the color that they want, and impart some of these substances into their tank water. I mean, it's an easy process. Of course, like any other thing you add to your aquarium, it's never a bad idea to know the impact of what you're adding.

Like using botanicals, utilizing tea bags in your aquarium requires some thinking, that's all.

The things that I personally dislike about using tea or so-called "blackwater extracts"or even botanical tea bags like "Shade" or the numerous other "teabag" products out there is that you are mainly going for an effect, without getting to embrace the functional aesthetics imparted by adding leaves, seed pods, etc. to your aquarium as part of its physical structure, as well as the ecological support they offer to the microcosm that is your aquarium. I mean, sure, you're likely imparting some of the beneficial compounds we talk about into your water.

And, despite anyone's recommendation, they're remarkably "improvisational" products. There is no real way to determine how much you need to add to achieve______. Like, what concentration do they impart what compounds into the water at? And at what rate?

Obviously, the same could be said of botanicals, but we're not utilizing botanicals simply to create brown water or specific pH parameters, etc. We're using them to foster an underwater ecology...The "tint" part is a "collateral" aesthetic benefit. Nature Herself determines how much of what compound actually leaches into the water from the botanicals as they break down.

Yes, with tea, teabags, or extracts, you sort of miss out on replicating a little slice of Nature in your aquarium. And of course, it's fine if your goal is just to color the water, or to impart some compounds into the water, I suppose. And I understand that some people, like fish breeders who need bare bottom tanks or whatever- like to "condition water" without all of the leaves and twigs and seed pods that we love.

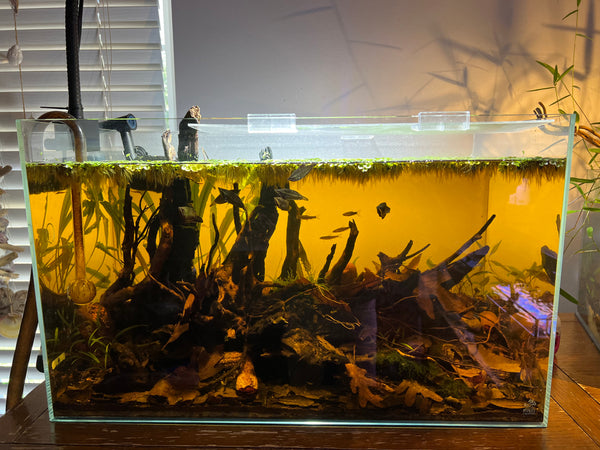

On the other hand, if you're trying to replicate the look and function (and maybe some of the parameters) of THIS:

You won't achieve it by using THIS:

It's simply a shortcut.

And look, I understand that we are all looking for the occasional shortcuts and easier ways to do stuff. And I realize that none of what we proffer here at Tannin is an absolute science. It's an art at this point, with a bit of science and speculation mixed in. There is no current way available to the hobby to test for "x" types or amounts of tannins (of which there are hundreds) or humid substances in aquariums.

I have not yet found a study thus far which analyzed wild habitats (say, Amazonia) for tannin concentrations and specific types, so we have no real model to go on.

The best we can do is create a reasonable facsimile of Nature.

We have to understand that there are limitations to the impacts of botanicals, tea, wood, etc. on water chemistry. Adding liter upon liter of "extract", or bag after bag of tea to your aquarium will have minimal pH impact if your water is super hard. When you're serious about trying to create more natural blackwater conditions, you really need an RO/DI unit to achieve "base water" with no carbonate hardness that's more "malleable" to environmental manipulation. Tea, twigs, leaves- none will do much unless you understand that.

There really is no "Instant Amazon" bottled solution that you just add to tap water and your Rio Nanay Angels will just spontaneously spawn!

Again, lest you feel that I'm trashing on the industry or product manufactueres- I'm not. I'm merely getting back to what made me fall in love with this stuff in the first place- the process. I'm sharing with you how I feel about this. And being authentic to myself and my philosophies on botanical method aquariums. You know, the ideas that many of you share...the ones that brought you to our community some 7 plus years ago!

I'm pretty adamant about it when I assure you that I won't stray off course again like I did with "Shade." I won't pander to the mass market, or try to jump on some "trend" And I will no longer offer a product which represents a shortcut; an abandonment of the process. It's not true to me.

I'm not trying to throw a wet blanket on any ideas we might have. Not trashing on anyone else's products. I'm not feeling particularly "defensive" about using tea or other "extracts" because I sell botanical materials for a living. It's sort of apples and oranges, really.

The hobby need not be an excercise in misery or toil or doing things the hard way.

And hey, the whole idea of utilizing concentrated extracts of stuff is something I've looked on with caution for a long time, and we've discussed here before. I'm an "equal opportunity critic"- I'll jump on our community for stuff we do, too! I'll even get on my own case, as I have about "Shade!"🤬

Yes- one of the things that I DO have an issue with in our little hobby sector is the desire by many "tinters" to make use of the water in which the initial preparation of our botanicals takes place in as a form of "blackwater tea" or "blackwater extract."

Now, while on the surface, there is nothing inherently "wrong" with the idea, I think that in our case, we need to consider exactly why we boil/soak our botanicals before using them in the aquarium to begin with.

I discard the "tea" that results from the initial preparation of botanicals- and I recommend that you do, too.

Here's why:

As I have mentioned many times before, the purpose of the initial "boil and soak" is to release some of the pollutants (dust, dirt, etc.) bound up in the outer tissues of the botanicals. It's also to "soften" the leaves/botanicals that you're using to help them absorb water and sink more easily. As a result, a lot of organic materials, in addition tannins and other substances are released.

So, why would you want a concentrated "tea" of dirt, surface pollutants, and other organics in your aquarium as a "blackwater extract?" And how much do you need? I mean, what is the "concentration" of desirable materials in the tea relative to the water? Like with teabags, it's not an easy, quick, clean thing to figure, right?

There is so much we don't know.

A lot of hobbyists tell me they are concerned about "wasting" the concentrated tannins from the prep water. I get it. However, trust me- the leaves and botanicals will continue to release the tannins and humic substances (with much less pollutants!) throughout their "useful lifetimes" when submerged, so you need not worry about discarding the initial water that they were prepared in.

Is it worth polluting your aquarium for this?

I certainly don't think so!

Do a lot of hobbyists do this and get away with this? Sure. Am I being overly conservative? No doubt. In Nature, don't leaves, wood, and seed pods just fall into the water? Of course.

However, in most cases, Nature has the benefit of dissolution from thousands of gallons/litres of water, right? It's an open system, for the most part, with important and export processes far superior and efficient to anything we can hope to do in the confines of our aquariums!

Okay, I think I beat that horse up pretty good!

How much botanical materials to use to get "tint effects?"

Well, that's the million dollar question.

Who knows?

I spent a lot of years right here perpetuating this absurdity, myself. So I'm at least partially to blame. But it's not just me...

There are (IMHO) absurd "recommendations" that have been proffered by vendors over the years recommending using "x" number of leaves, for example, per gallon/liter of water. We used to do it, too...It's kind of stupid, actually.

There are simply far, far too many variables- ranging from starting water chem to pH to alkalinity, and dozens of others- which can affect the "equation" and make specific numbers unreliable at best.

Personally, if I recommend certain quantities of leaves or whatever, its more based upon my concern of not overloading an existing aquarium with excessive amounts of materials which can decompose and create environmental issues, more than any concern over making your water too dark.

How do you determine how much stuff you should add, then?

This might shock you:

You need to kind of go with your instinct. Go slowly. Evaluate the appearance of your water (if that WAS your main goal, lol), the behaviors of the fishes...the pH, alkalinity, TDS, nitrate, phosphate, or other parameters that you like to test for. It's really a matter of experimentation.

An understanding of aquatic ecology and basic aquarium water chemistry is invaluable if you're into this sort of stuff, trust me. And you likely won't get it from a cute 5 minute YouTube video or a hashtag-ridden Instagram post by me or anyone else. You'll need to do old-fashioned research. Trust me, it's not that difficult- and it's totally worth it!

Am I a fan of intentionally "tinting" the water at ALL? Well, of course! I mean, this blog is called "The Tint", right? And my company is called "Tannin Aquatics!"

However...

I'm a much bigger fan of "tinting" the water based on the materials I incorporate into the aquarium's ecology. The botanicals will release their "contents" at a pace dictated by their environment. And, when they're "in situ", you have a sort of "on board" continuous release of tannins and other substances based upon the decomposition rate of the materials you're using, the water chemistry, etc.

And most important, they become "fuel" for biological processes and the colonization of fungal and bacterial growths.

Of course, you can still add too many botanicals too fast to an established tank, as we've mentioned numerous times. Learning how much to use is all about developing your own practices based on what works for you...In other words, incorporating them in your tank and evaluating their impact on your specific situation. It's hardly an exact science. Much more of an "art" or "best guess" thing than a science..at least right now.

That being said, I think that our entire botanical-method aquarium approach needs to be viewed as just that- an approach. A way to use a set of materials, techniques, and concepts to achieve desired results consistently over time. An approach that tends to eschew short-term "fixes" in favor of long-term technique.

In my opinion, this type of "short-term, instant-result" mindset has made the reef aquarium hobby of late more about adding that extra piece of gear or specialized chemical additive as means to get some quick, short term result than it is a way of taking an approach that embraces learning about the entire ecosystem we are trying to recreate in our tanks and facilitating long-term success.

Yeah, once again- the "problem" with Rooibos or blackwater extracts and teabags as I see it is that they encourage a "Hey, my water is getting more clear, time to add another tea bag or a teaspoon of extract..." mindset, instead of fostering a mindset that looks at what the best way to achieve and maintain the desired environmental results naturally on a continuous basis is.

A sort of symbolic manifestation of encouraging a short-term fix to a long-term concern.

Again, there is no "right or wrong" in this context- it's just that we need to ask ourselves why we are utilizing these products, and to ask ourselves how they fit into the "big picture" of what we're trying to accomplish. And we shouldn't fool ourselves into believing that you simply add a drop of something- or even throw in some Alder Cones or Catappa leaves- and that will solve all of our problems.

Are we fixated on aesthetics, or are we considering the long-term impacts on our closed system environments?

Sure, I can feel cynicism towards my mindset here. I understand that. This is part of my personal journey, and like everything else, I'm sharing it with you. These things just don't feel "good" to me.

I'm not going to take Tannin into directions that don't feel good to me. Our "refresh" is going to be very different- perhaps slightly disorienting to some- yet it will be much, much more devoted to our founding principles and mindset. A lot more about the process and how to achieve our goals than simply a huge array of every seed pod and leaf on the market. Been there, done that.

Rather, it will be as much a celebration of the art and science of botanical method aquariums as it will be an outlet to purchase stuff.

Oh, I'm straying off topic..sort of. Let's get back to the "meat" of this...

Now, if we look at the use of extracts and additives, and additional botanicals- for that matter- as part of a "holistic approach" to achieving continuous and consistent results in our aquariums, that's a different story altogether.

Yes, one of the things I've often talked about over the years here is the need for us as hobbyists to deploy patience, observation, and testing when playing with botanical materials in our aquariums.

I've eschewed, even vilified "hacks" and "shortcuts"...I felt (and continue to feel, really), that trying to circumvent natural processes in order to arrive at some "destination" faster is an invitation to potential problems over the long term, and at the very least, a way to develop poor skills that will work to our detriment.

Obviously, I'm not saying that the botanical-method aquarium approach should be all drudgery and ceaseless devotion to a series of steps and guidelines issued by...someone. I'm not saying that every "teabag" product is a big joke, and a rip off designed for suckers, etc...NO! That's even more frightening to me than the idea of "shortcuts" and "hacks!" Dogma sucks.

And guess what? Ideas and practices DO evolve over time as we learn more about what we're doing and accumulate more experience.

It's why I though that "Shade" might have been a good idea at the time...

It makes a lot more sense to learn a bit more about how natural materials influence the wild blackwater habitats of the world, and to understand that they are being replenished on a more or less continuous basis, then considering how best to replicate this in our aquariums consistently and safely.

So, enjoy your teabags. Prep your botanicals. Replace your leaves. Observe, study, inquire. Read. Share.

Remember, it's a hobby. You're building up an ecosystem. It's a marathon, not a sprint. And to truly understand what goes on in Nature, it's never a bad idea to replicate Nature to the best extent possible- even if it's not a "hack" sometimes.

"Shade" won't be coming back. But the lessons that it taught me will stick around for a long time.

RIP, "Shade." It was good to know you... And you looked pretty sexy while you were here!

Stay studious. Stay devoted. Stay authentic...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

How much of...what? And what are the implications? The benefits and downsides to "Speculative biochemistry"

Assumptions about various things in the aquarium hobby are quite pervasive. Especially assumptions based on aesthetics or appearances. For example, our hobby seems to place a heavy emphasis on the color of the water in botanical method aquariums.

The deeply tinted water in many of the fantastic aquariums we see shared on social media seems to imply to many that these "tinted" aquariums feature "soft, acidic" water conditions as a matter of course- something that we erroneously assume.

And a fair number of hobbyists, upon embarking on their first adventure with botanical materials, express frustration, confusion, and dismay that their hard, alkaline tap water is still, hard and alkaline! This type of confusion in likely cause by a lack of understanding of the fundamentals of aquarium water chemistry, and what exactly "blackwater" is.

Understand that, as we've said many times here, botanicals (AKA "expensive botanicals" as one armchair expert referred to them recently) will not create soft, acidic "blackwater conditions" without other measures being taken by the hobbyist.

Yes, the water color is a cool “collateral benefit” and worthy of celebration - but it doesn’t really mean all THAT much, in actuality, does it? Sure- it means that leaves, seed pods, etc. have imparted their color-producing tannins into the water…but, which ones (there are hundreds!), and in what concentration? And what does it mean to your fishes?

Color alone is not an indication of the pH, dKH, or TDS of your water.. It's not an indicator of water quality. In actuality, it’s little more than an indicator that some of these materials are dissolving into the water.

Yet, we in the hobby make claims.

And we make recommendations based off of them...

And at best, they’re subjective guesses. How much tannin or other compounds are in a given botanical is, without very specific bioassays and highly specialized equipment- simply a guess on our part.

I think about it a lot..

For us to make "dosing" recommendations based on theoretical concentrations of various compounds thought to be present in a given botanical is simply irresponsible and not grounded in fact. Sure, we tell you that, based upon our experience, a given wood or seed pod, or leaf will color the water a darker color than another...but, again, what does that mean, really?

Not that much.

Again, the color of the water is absolutely not an indication of anything- other than the fact that tint producing types of tannins are present. It's an "aesthetic factor"- that's it. It doesn’t tell you what the pH, dKH, or TDS of the water are.. let alone, how much of what types and forms of tannins are present…

Yet, we in the hobby are continuously making this "crossover assumption," if not in our minds, on our social media feeds and ads as vendors. It's another example of us dumbing shit down to make things more "accessible" to hobbyists. How does dumbing stuff down make things more "accessible?" Is that what the hobby needs: Marginally educated, yet highly "entertained" hobbyists, with their eager minds filled with drivel and supposition instead of some of the "boring" stuff, then continuing to dutifully pass it along to fellow hobbyists as if it means something...

Ya know, ignoring facts?

Final thoughts on the "water color" thing:

What does the color of the water mean, from an environmental standpoint?

Quite honestly, we don’t really know! We need more information. That’s where the power of our observations and experiences can help fill in some of the mystery. Advanced water testing and monitoring will also help.. however, the reality is that we have more questions than answers, and likely will for some time!

There is nothing wrong with speculation, and researching stuff to attempt to validate or disprove our theories...as long as we're open-minded and follow the facts, whenever possible.

Sleuthing as a hobbyist is cool.

I went through this phase myself...And, being the geek that I am, I went to extraordinary lengths to try to correlate specific environmental conditions, or the presence of specific compounds in the water with the use of botanical materials in our tanks. A few years back, I was really "hair-on-fire" about this. It was a real area of "speculative science"...not exactly scholarly, but fun for a hobbyist, sure.

Here's a story that might interest you:

I was visiting a killifish forum on Facebook one night, and one of the participants was discussing some new fishes he obtained. One was from a rare genus called Episemion. Weird, because it is a fish that falls genetically halfway between Epiplatys and Aphyosemion.

Even more interesting to me was the discussion that it's notoriously difficult to spawn, and that it is only found in a couple of places in The Congo.

And even more interesting was that it is in a region known for high levels of selenium in the soil...And that's VERY interesting. Selenium is known to be nutritionally beneficial to higher animals and humans at a concentration of 0.05-0.10ppm. It's an essential component of many enzymes and proteins, and deficiencies are known to cause diseases.

One of its known health benefits for animal is that it plays a key role in immune and reproductive functions!

Okay, that perhaps helps explain the "difficult to breed" part? Sounds like the fishes need higher levels of selenium than we generally provide in aquarium water, right?

Selenium occurs in soil associated with sulfide minerals. It's found in plants at varying concentrations which are dictated by the pH, moisture content, and other factors of the soil they reside in. Soils which contain high concentration of selenium are found in greater concentration certain tropical regions.

Interesting...

But, how much do we need to provide our Episemion in order for them to reproduce more easily...or DO we, even need them? And how do we provide elevated selenium levels in the aquarium?

Now, soil is perhaps one way, right? Yet, I'm doubtful that we know the specific concentrations of selenium in many of the planted aquarium substrates out on the market, and most hobbyists aren't just throwing in that "readily available" tropical Congo soil that you can pick up at any LFS in their tanks, right? 😜

So, how would we get more selenium into our tanks for our killies?

Que speculation...

My thought was that perhaps botanicals could be one way. I rationalized that maybe decomposing botanicals from plants known to contain higher levels of selenium in them could impart this compound into the water! What botanical comes from a plant which is known to have elevated levels of selenium?

The Brazil nut is known to have selenium. It comes from a botanical that we are familiar with in the botanical aquarium world...

The "Monkey Pot!"

Yes- it's technically a fruit capsule, produced from the abundant tree, Lecythis pisonis, native to South America -most notably, the Amazonian region. Astute, particularly geeky readers of "The Tint" will recognize the name as a derivative of the family Lecythidaceae, which just happens to be the family in which the genus Cariniana is located...you know, the "Cariniana Pod." Yeah...this family has a number of botanical-producing trees in it, right?

Yes.

Hmm...Lecythidae...

Ahh...it's also known as the taxonomic family which contains the genus Bertholletia- the genus which contains the tree, Bertholletia excelsa- the bearer of the "Brazil Nut." You know, the one that comes in the can of "mixed nuts" that no one really likes? The one that, if you buy it in the shell, you need a freakin' sledge hammer to crack?

Yeah. That one.

(Craving more useless Brazil Nut trivia?

Check this out: Because of their larger size size, they tend to rise to the top of the can of mixed nuts from vibrations which are encountered during transport...this is a textbook example of the physics concept of granular convection- which for this reason is frequently called...wait for it...the "Brazil Nut effect." (I am totally serious!)

Okay, anyways...I went way too far off course here.)

So, yeah, I thought I was on to something...

I was wondering it would be possible to somehow utilize the "Monkey Pot" in a tank with these fishes to perhaps impart some additional selenium into the water? Okay, this begs additional questions? How much? How rapidly? In what form? Wouldn't it be easier to just grind up some Brazil nuts and toss 'em in? Or would the fruit capsule itself have a greater concentration of selenium? Would it even leach into the water?

Where the ---- am I going with my sharing of my exercise?

I'm just sort of taking you out on the ledge here; demonstrating how the idea of making speculations can potentially yield some practical solutions, if you can actually verify through testing or practical experimentation. However, we can't "default" assume that "Monkey Pots in aquarium= Elevated selenium levels". We can only speculate, in the absence of proper, legit lab tests. Perhaps we can find anecdotal evidence to support our theories, but that's often about all we can do.

But we can't dumb it down by making our speculations "factual"...

We talk a lot here about utilizing botanicals to provide "functional aesthetics" at the every least, a possibility to help solve some potential challenges in the hobby. THAT is a good start. It's kind of a safe "catch all", which leaves open the possibility of proving or disproving more intensive assumptions, though. It doesn't really adamantly assume anything that cannot be proven through observation.

Yet, we in the hobby and industry (present company included) have continuously spouted speculation on the various "other benefits" of botanical materials as if they are a given. Like, this is something that we have done with Catappa leaves forever. You've seen my blogs questioning the carte blanche accessions that we in the industry heap on to vendors' assertions about the alleged health benefits that they are purported to offer fishes. Some is pure marketing bullshit. Some of it IS perhaps, legit, proven in lab experiments.

Yet, I think it's worth continuously investigating this stuff; experimenting on a practical level as hobbyists-"end users"- when possible, to see if there is some merit to these claims...right?

We need to connect observation and investigation with the practical application of patience.

Yeah, our old friend, patience. Patience is simply fundamental in the botanical-method aquarium world, and it can truly make the difference between success and failure.

Observation and attempting to ascertain what's going on in your tank "real time" are key practices that we need to embrace in order to determine what, if any benefits botanicals are bringing to the fight.

Yes, I know, we talk a lot about patience here, especially in the context of working with our botanical-style blackwater aquariums. We've pretty much "force-fed" you the philosophy of not rushing the evolution of your aquarium, of hanging on during the initial breakdown of the botanicals, not freaking out when the biofilms and fungal growths appear...

Patience.

Embracing the process.

Not giving in to preconceived notions about we're told should happen in our tanks, one way or another.

What goes hand-in-hand with patience is the concept of...well, how do I put it eloquently...leaving "well enough alone"- not messing with stuff. In the context of trying to get fishes to breed, this is always a bit of a challenge, isn't it?

Yeah, just not intervening in your aquarium when no intervention is really necessary is not easy for many aspiring hobbyists. I mean, sure, it's important to take action in your aquarium when something looks like it's about to "go south", as they say- but the reality is that good things in an aquarium happen slowly, and if things seem to be moving on positive arc, you need not "prod" them any further.

I think this is one of the most underrated mindsets we can take as aquarium hobbyists. Now, mind you- I'm not telling you to take a laissez-faire attitude about managing your aquariums. However, what I am suggesting is that pausing to contemplate what will happen if you intervene is sometimes more beneficial than just "jumping in" and taking some action without considering the long-term implications of it. It's one thing to be "decisive"- quite another to be "overreactive!"

However, it's easy to forget when its "your babies", right? Online aquarium forums are filled with frantic questions from members about any number of "problems" happening in their aquariums, a good percentage of which are nothing to worry about. You see many of these hobbyists describe "adding 100 mg of _______ the next day, but nothing changed..." (probably because nothing was wrong in the first place!).

Now, sure, sometimes there ARE significant problems that we freak out about, and should jump on-but we have to "pick our battles", don't we? Otherwise, every time we see something slightly different in our tank we'd be reaching for the medication, the additives, or adding another gadget (a total reefer move, BTW), etc.

Let Nature take Her course on some things.

Understand that our closed systems are still little "microcosms", subject to the rules laid down by the Universe. Realize that sometimes- more often than you might think- it's a good idea to "leave well enough alone!" Make good hypothesis, but don't push out highly speculative over generalizations as "the gospel" on something...

And circling back- we as hobbyists should hesitate to make quick, unverifiable assumptions based only on aesthetics.. We can and should enjoy them, but we need to think about how the aesthetics are kind of a “byproduct” of some sort of biochemical process.. it’s all a grand experiment, and we’re all a part of it!

We can do better. And we should want to... Studying what actually occurs in our tanks is not that hard! And in fact, you'll find that the pretty pics of tanks we all love some much will take on so much more meaning when we understand the function- and some of the science behind them.

Stay educated. Stay informed. Stay curious. Stay diligent. Stay enthusiastic...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Inception.

We've had a lot of requests lately to discuss how we start up our botanical method aquariums. Now sure, we've covered this topic before over the years; yet, as our practices have evolved, so has our understanding about why we do things the way that we do- and why it works.

Establishing a new botanical method aquarium is an exciting, fun, and interesting time. And the process of creating your aquarium is shockingly easy, decidedly un-stressful, and extremely engaging.

The main ingredients that you need are vision, a bit of knowledge, and... patience.

Bringing your tank from a clean, dry,"static display" to a living, breathing microcosm, filled with life is an amazing process. This, to me is really the most exciting part of keeping botanical method aquariums.

And how do we usually do it? I mean, for many hobbyists, we've been more or less indoctrinated to clean the sand, age water, add wood, arrange plants, and add fishes. And that works, of course. It's the basic "formula" we've used for over a century.

Yet, I'm surprised how we as a hobby have managed to turn what to me is one of the most inspiring, fascinating, and important parts of our aquarium hobby journey into what is more-or-less a "checklist" to be run through- an "obstacle", really- to our ultimate enjoyment of our aquarium.

When you think about it, setting the stage for life in our aquariums is the SINGLE most important thing that we do. If we utilize a different mind set, and deploy a lot more patience for the process, we start to look at it a bit differently.

I mean, sure, you want to rinse sand as clean as possible. You want make sure that you have a piece of wood that's been soaked for a while, and..

Wait, DO you?

I mean, sure, if you don't rinse your sand carefully, you'll get some cloudy water for weeks...no argument there.

And if you don't clean your driftwood carefully, you're liable to have some soil or other "dirt" get into your system, and more tannins being released, which leads to...well, what does it lead to?

I mean, an aquarium is not a "sterile" habitat. Let's not fool ourselves.

The natural aquatic habits which we attempt to emulate, although comprised of many millions of times the volumes of water volume and throughput that we have in our tanks- are typically not "pristine"- right? I mean, soils from the surrounding terrestrial environment carry with them decomposing matter, leaves, etc, all of which impact the chemistry, oxygen-carrying capacity, biological activity, and of course, the visual appearance of the water.

And that's kind of what our whole botanical-method aquarium adventure is all about- utilizing the "imperfect" nature of the materials at our disposal, and fostering and appreciating the natural interactions between the terrestrial and aquatic realms which occur.

Of course, much like Nature, our botanical-method aquariums make use of the "ingredients" found in the abundant materials which comprise the environment. And the "infusion" of these materials into the water, and the resulting biological processes which occur, are what literally make our tanks come alive.

And yeah, it all starts with the nitrogen cycle...

We can embrace the mindset that every leaf, every piece of wood, every bit of substrate in our aquariums is actually a sort of "catalyst" for sparking biodiversity, function, and yes- a new view of aesthetics in our aquariums.

I'm not saying that we should NOT rinse sand, or soak wood before adding it to our tanks. What I AM suggesting is that we don't "lose our shit" if our water gets a little bit turbid or there is a bit of botanical detritus accumulating on the substrate. And guess what? We don't have to start a tank with brand new, right-from-the-bag substrate.

Of course not.

We can utilize some old substrate from another tank (we have done this as a hobby for decades for the purpose of "jump starting" bacterial growth) which also has the side benefit of providing a different aesthetic as well!

And, you can/should take it further: Use that slightly algal-covered piece of driftwood or rock in our brand new tank...This gives a more "broken-in look", and helps foster a habitat more favorable to the growth of the microorganisms, fungi, and other creatures which comprise an important part of our closed aquarium ecosystems.

In fact, in a botanical-method aquarium, facilitating the rapid growth of such biotia is foundational.

It's perfectly okay for your tank to look a bit "worn" right from the start. Functional aesthetics once again! the look results from the function.

In fact, I think most of us actually would prefer that! It's okay to embrace this. From a functional AND aesthetic standpoint. Employ good husbandry, careful observation, and common sense when starting and managing your new aquarium.

So don't obsess over "pristine." Especially in those first hours.

The aquarium still has to clear a few metaphorical "hurdles" in order to be a stable environment for life to thrive.

I am operating on the assumption (gulp) that most of us have a basic understanding of the nitrogen cycle and how it impacts our aquariums. However, maybe we don’t all have that understanding. My ramblings have been labeled as “moronic” by at least one “critic” before, however, so it’s no biggie for me as said “moron” to give a very over-simplified review of the “cycling” process in an aquarium, so let’s touch on that for just a moment!

During the "cycling" process, ammonia levels will build and then suddenly decline as the nitrite-forming bacteria multiply in the system. Because nitrate-forming bacteria don't appear until nitrite is available in sufficient quantities to sustain them, nitrite levels climb dramatically as the ammonia is converted, and keep rising as the constantly-available ammonia is converted to nitrite.

Once the nitrate-forming bacteria multiply in sufficient numbers, nitrite levels decrease dramatically, nitrate levels rise, and the tank is considered “fully cycled.”

And of course, the process of creating and establishing your aquariums ecology doesn't end there.

With a stabilized nitrogen cycle in place, the real "evolution" of the aquarium begins. This process is constant, and the actions of Nature in our aquariums facilitate changes.

And our botanical-method systems change constantly.

They change over time in very noticeable ways, as the leaves and botanicals break down and change shape and form. The water will darken. Often, there may be an almost "patina" or haziness to the water along with the tint- the result of dissolving botanical material and perhaps a "bloom" of microorganisms which consume them.

This is perfectly analogous to what you see in the natural habitats of the fishes that we love so much. As the materials present in the flooded forests, ponds, and streams break down, they alter it biologically, chemically, and even physically.

It's something that we as aquarists have to accept in our tanks, which is not always easy for us, right? Decomposition, detritus, biofilms- all that stuff looks, well- different than what we've been told over the years is "proper" for an aquarium. And, it's as much a perception issue as it is a husbandry one. I mean, we're talking about materials from decomposing botanicals and wood, as opposed to uneaten food, fish waste, and such.

What's really cool about this is that, in our community, we aren't seeing hobbyists freak out over some of the aesthetics previously associated with "dirty!"

It's seen as a fundamental part of the evolution of the tank.

And soon, you'll see the emergence of elegant, yet simple life forms, such as bacterial biofilms and fungal growths. We've long maintained that the appearance of biofilms and fungi on your botanicals and wood are to be celebrated- not feared. They represent a burgeoning emergence of life -albeit in one of its lowest and (to some) most unpleasant-looking forms- and that's a really big deal.

Biofilms, as we've discussed ad nauseam here, form when bacteria adhere to surfaces in some form of watery environment and begin to excrete a slimy, gluelike substance, consisting of sugars and other substances, that can stick to all kinds of materials, such as- well- in our case, botanicals. It starts with a few bacteria, taking advantage of the abundant and comfy surface area that leaves, seed pods, and even driftwood offer.

The "early adapters" put out the "welcome mat" for other bacteria by providing more diverse adhesion sites, such as a matrix of sugars that holds the biofilm together. Since some bacteria species are incapable of attaching to a surface on their own, they often anchor themselves to the matrix or directly to their friends who arrived at the party first.

Tannin's creative Director, Johnny Ciotti, calls this period of time when the biofilms emerge, and your tank starts coming alive "The Bloom"- a most appropriate term, and one that conjures up a beautiful image of Nature unfolding in our aquariums- your miniature aquatic ecosystem blossoming before your very eyes!

The real positive takeaway here: