- Continue Shopping

- Your Cart is Empty

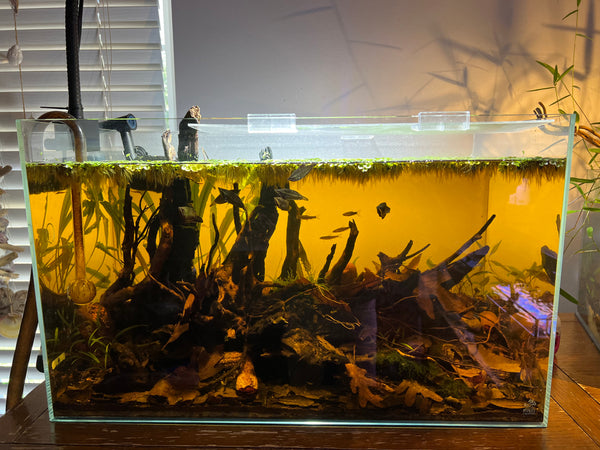

Grand experiments? Or, just the way our aquariums are "filtered?"

As a lifelong hobbyist, devoted to natural aquarium systems, the idea of outfitting or setting up my aquariums to facilitate biological processes is second nature. With botanicals in play, the concept of them serving as a medium for biological support is "baked in" to our processes.

And you don't need to invest in all sorts of plastic filter media, blocks, beads, "noodles", etc. to facilitate biological filtration in your botanical method aquarium. I use a lot of "all-in-one" aquariums in my work; that is, aquariums with a rear compartment housing the return pump/heater, with space intended to hold biological media.

I run them empty.

Why?

Because the aquarium itself-or, more specifically- the botanical materials which comprise the botanical-method aquarium "infrastructure" act as a biological "filter system."

In other words, the botanical materials present in our systems provide enormous surface area upon which beneficial bacterial biofilms and fungal growths can colonize. These life forms utilize the organic compounds present in the water as a nutritional source.

Oh, the part about the biofilms and fungal growths sounds familiar, doesn't it?

Let's talk about our buddies, the biofilms, just a bit more. One more time. Because nothing seems as contrary to many hobbyists than to sing the praises of these gooey-looking strands of bacterial goodness!

Structurally, biofilms are surprisingly strong structures, which offer their colonial members "on-board" nutritional sources, exchange of metabolites, protection, and cellular communication. An ingenious natural design. They form extremely rapidly on just about any hard surface that is submerged in water.

When I see aquarium work in which biofilms are considered a "nuisance", and suggestions that it can be eliminated by "reducing nutrients" in the aquarium, I usually cringe. Mainly, because no matter what you do, biofilms are ubiquitous, and always present in our aquariums.

We may not see the famous long, stringy "snot" of our nightmares, but the reality is that they're present in our tanks regardless. Inside every return hose, filter compartment, and powerhead. On every surface, every rock, or piece of wood.

The other reality is that biofilms are something that we as aquarists typically have feared because of the way they look. In and of themselves, biofilms are not harmful to our fishes. They function not only as a means to sequester and process nutrients ( a "filter" of sorts), they also represent a beneficial food source for fishes.

Now, look, I can see rare scenarios where massive amounts of biofilms (relative to the water volume of the aquarium) can consume significant quantities of oxygen and be problematic for the fishes which reside in your tank. These explosions in biofilm growth are usually the result of adding too much botanical material too quickly to the aquarium. They're excaserbated by insufficient oxygenation/circulation within the aquarium.

These are very unusual circumstances, resulting from a combination of missteps by the aquarist.

Typically, however, biofilms are far more beneficial that they are reven emotely detrimental to our aquariums.

Nutrients in the water column, even when in low concentrations, are delivered to the biofilm through the complex system of water channels, where they are adsorbed into the biofilm matrix, where they become available to the individual cells. Some biologists feel that this efficient method of gathering energy might be a major evolutionary advantage for biofilms which live in particularly in turbulent ecosystems, like streams, (or aquariums, right?) with significant flow, where nutrient concentrations are typically lower and quite widely dispersed.

Biofilms have been used successfully in water/wastewater treatment for well over 100 years! In such filtration systems the filter medium (typically, sand) offers a tremendous amount of surface area for the microbes to attach to, and to feed upon the organic material in the water being treated. The formation of biofilms upon the "media" consume the undesirable organics in the water, effectively "filtering" it!

Biofilm acts as an adsorbent layer, in which organic materials and other nutrients are concentrated from the water column. As you might suspect, higher nutrient concentrations tend to produce biofilms that are thicker and denser than those grown in low nutrient concentrations.

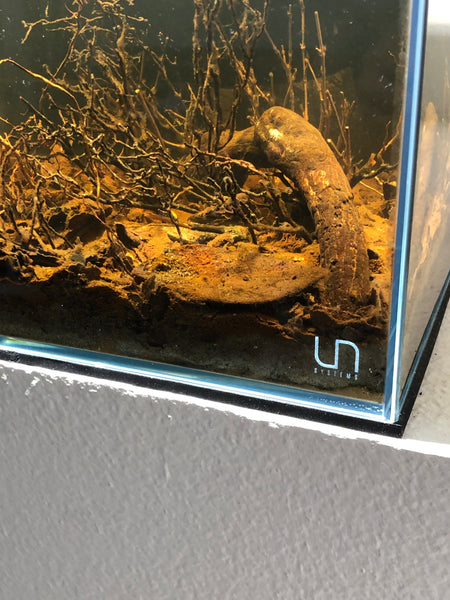

it's pretty much a "given" that any botanicals or leaves that you drop into your aquarium will, over time, break down. Wood, too. And typically, before they break down, they'll "recruit" (a fancy word for "acquire') a coating of some rather unsightly-looking growth. Well, "unsightly" to those who have not been initiated into our little world of decomposition, fungal growth, biofilms, tinted water, etc., and maintain that an aquarium by definition is a pristine-looking place without a speck of anything deemed "aesthetically unattractive" by the masses!

And then, of course, there are our other rather slimy-looking friends- the fungi.

Yeah, the stringy stuff that you'll see covering the leaves, botanicals, and wood that you place into your aquarium. Let's talk about why you actually WANT the stuff there in the first place.

The fungi known as aquatic hyphomycetes produce enzymes which break down botanical materials in water. Essentially, they are primary influencers of leaf maceration. They're remarkably efficient at what they do, too. In as little as 3 weeks, as much as 15% of the decomposing leaf biomass in many aquatic habitats is "processed" by fungi, according to one study I found!

Aquatic hyphomycetes play a key role in the decomposition of plant litter of terrestrial origin- an ecological process in rain forest streams that allows for the transfer of energy and nutrients to higher trophic levels.

This is what ecologists call "nutrient cycling", folks.

These fungi colonize leaf litter and twigs and such soon after they're immersed in water. The fungi mineralize organic carbon and nutrients and convert coarse particulate matter into...wait for it...fine particulate organic matter. They also increase leaf litter palatability to shredding organisms (shrimp, insects, some fishes, etc.), which help further facilitate physical fragmentation.

Fungi tend to colonize wood and botanical materials because they offer them a lot of surface area to thrive and live out their life cycle. And cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin- the major components of wood and botanical materials- are easily degraded by fungi, which posses enzymes that can digest and assimilate these materials and their associated organics!

Fungi are regarded by biologists to be the dominant organisms associated with decaying leaves in streams, so this gives you some idea as to why we see them in our aquariums, right?

In aquarium work, we see fungal colonization on wood and leaves all the time. Most hobbyists will look on in sheer horror if they saw the same extensive amount of fungal growth on their carefully selected, artistically arranged wood pieces as they would in virtually any aquatic habitat in Nature!

Yet, it's one of the most common, elegant, and beneficial processes that occurs in natural aquatic habitats!

It's everywhere.

Of course, fungal colonization of wood and botanicals is but one stage of a long process, which occurs in Nature and our aquariums. And, as hobbyists, once we see those first signs of this stuff, the majority of us tend to reach for the algae scraper or brush and remove as much of it as possible- immediately! And sure, this might provide some "aesthetic relief" for some period of time- but it comes right back...because these materials will provide a continuous source of food and colonization sites for fungal growths for some time!

I know that the idea of "circumventing" this stuff is appealing to many, but the reality is that you're actually interrupting an essential, ecologically beneficial natural process. And, as we know, Nature abhors a vacuum, and new growths will return to fill the void, thus prolonging the process.

You want this stuff in your aquariums.

Again, think about the role of aquatic hyphomycetes in Nature.

Fungal colonization facilitates the access to the energy trapped in deciduous leaves and other botanical materials found in tropical streams for a variety of other organisms to utilize.

As we know by now, fungi play a huge role in the decomposition of leaves, both in the wild and in the aquarium. By utilizing special enzymes, aquatic fungi can degrade most of the molecular components in leaves, such as cellulose,, hemicelluloses, starch, pectin and even lignin.

Fungi, although not the most attractive-looking organisms, are incredibly useful...and they "play well" with a surprisingly large number of aquatic life forms to create substantial food webs, both in the wild and in our aquariums!

And it all comes full circle when we talk about "filtration" in our aquariums. Let's come back to this one more time.

People often ask me, "Scott, what filter do you use use in a botanical-method aquarium?" My answer is usually that it just doesn't matter. You can use any type of filter. The reality is that, if allowed to evolve and grow unfettered, the aquarium itself- all of it- becomes the "filter."

You can embrace this philosophy regardless of the type of filter that you employ.

Yeah, my sumps and integrated filter compartments in my A.I.O. tanks are essentially empty.

I may occasionally employ some activated carbon in small amounts, if I'm feeling it- but that's it. The way I see it- these areas, in a botanical-method aquarium, simply provide more water volume, more gas exchange; a place forever more bacterial attachment (surface area), and perhaps an area for botanical debris to settle out. Maybe I'll remove them, if only to prevent them from slowing down the flow rate of my return pumps.

But that's it.

A lot of people are initially surprised by this. However, when you look at it in the broader context of botanical method aquariums as miniature ecosystems, it all really makes sense, doesn't it? The work of these microorganisms and other life forms takes place throughout the aquarium.

The aquarium is the "filter."

The biomass of lifeforms in the aquarium comprise the ecology and physical structure as well.

I recall an experiment I did about 12 years ago; another exploration into letting the ecology within the aquarium- and the aquarium itself- become the "filter."

My dear friend, the late Jake Adams of Reef Builders, came up with what he called the “EcoReef Zero” concept; essentially an approach to keeping coral that eschews the superfluous- gear, live rock, macroalage, sand, etc., in favor of using the coral biomass and the physical aquarium itself as the "filter."

After seeing Jake's work in this area, and lots of discussions with him, I immediately realized that this approach was philosophically unlike anything I had ever attempted before. Yet, it somehow resonated for reasons I could not entirely put together. This approach was developed to focus on creating an excellent environment for corals, providing them with everything that they needed to assure growth and health, and nothing that they didn’t, while keeping things as simple and uncomplicated as possible- aquatic minimalism, if you will.

While in principle the concept of the Zero Reef is ridiculously simple and almost mundane, if you follow the history of modern “reefing” technique, it’s downright “revolutionary” from a philosophical standpoint. So much energy and effort has been expended in recent years attempting to keep corals in high biodiversity, multi-faceted “reef” systems, with all of their competing life forms, that anything else seems on the surface to be almost heretical!

I think a proper description for the approach would be something like “Minimal Diversity Coral Husbandry”. Jake called it “Reduced Ecology Reefing”. It’s sort of the “anti-reef” approach, if you will.

The "Zero Reef" approach essentially distills coral keeping down to its most basic and simple elements, and utilizes minimal technology and energy to achieve success. The premise is simple: Do away with the unnecessary “distractions” of conventional reef aquaria- live rock, sandbeds, macroalage, large fish populations, “cleanup crews”, extensive equipment, etc., and focus solely on the coral, with the bulk of the biomass in the system being contained in the coral tissue itself.

What I only half-jokingly referred to as “revolutionary” about the approach is really the mindset you need to adapt- a reliance on your intuition, a trust in the most basic of skills as a marine aquarist. This differs from the modern convention significantly, because this philosophy really focuses on one element of marine aquarium keeping: The needs of your coral. Indeed, on the coral itself. While there is nothing “wrong” with other, more traditional approaches, by their very nature, they tend to shift focus off of the true “stars” of the aquarium- the corals.

What you want in the "Zero Reef "approach are the beneficial bacterial populations to help break down metabolic waste products, without a huge diversity of other life form to burden the system in any way. In essence, what you’re looking at is a “Petri dish” for coral culture, or the equivalent of a flower in a vase – totally different than any other saltwater experience I’ve ever had.

It is to a conventional reef aquarium what haute couture is to ready-to-wear clothing in the fashion industry: An individual, special aquarium conceived to experiment with simplified coral husbandry. It’s not “your father’s frag tank”. And, it was pretty interesting from an aesthetic standpoint, too! And I think that it's scaleable.

For my “Zero Reef”, I decided to utilize a 4- gallon aquarium, with one side and the bottom painted flat black for aesthetics. My Eco Reef was located on my desk in my office, where I was able to enjoy it all day, every day! The aquarium was equipped with a simple internal filter with media removed, a heater and seven paltry watts of 6700K LED lighting. The setup of the system could not have been easier:

Literally pour water in the aquarium, plug everything in, and you’re under way.

The coral specimen was mounted on a single piece of slate.

Slate was used because the Eco Reef “philosophy” postulates that the porosity of live rock, coupled with the “on board” life that accompanies it, places an excessive burden on a system solely designed to grow coral, and thus detracts from the needs of the corals in the aquarium. Slate has minimal pore structure, primarily on the surface, and does not provide a matrix of nooks and crannies for detritus and nutrients to accumulate. It’s essentially inert, and has little, if any measurable impact on water parameters. Quite frankly, I could have just placed the coral right on the bottom of the aquarium, but the slate does provide a bit of aesthetic interest. I mean, I can’t totally depart from my principles, right?

It really doesn’t get any easier than this: I topped off for evaporation (mere ounces in this 4-gallon aquarium) as needed, and changed 100% of the water every Thursday (not a water exchange, mind you- this was a complete replacement of all of the water in the tank). The maintenance process literally took 5 minutes, and most of that was consumed by putting a towel around the aquarium so I didn't spill on my desk! I fed the coral small quantities of frozen mysis every Tuesday and Wednesday, or when I had the chance.

Probably the most difficult decision of the whole project was deciding what coral to use to serve as the primary inhabitant for the aquarium. The candidate coral had to be one that is fleshy, voluminous, and can safely be placed in a system without sand or rocks. After much consideration, I decided upon a specimen of Green Bubble Coral (Plerogyra simplex) for my test subject.

The piece of coral was approximately 4 inches in length when I started the experiment. Bubble Coral has a reputation for being relatively easy to keep, yet it’s not without its challenges, too. Although Jake recommended Euphyllia, various Faviids, Wellsophyllia, and other corals as ideal candidates for this type of system, I forged ahead with Bubble Coral for the simple reason that I like the way it looks!

The coral’s feeding reactions were immediate- and impressive! The feeding schedule was consistent with the protocol that Jake and I discussed: Feed the coral a couple of days before a water change. This allowed the coral to process and eliminate waste products during that time period, and for me to export as much of the metabolic waste as possible, as quickly as possible.

Being a habitual water changer and nutrient export fiend since my early days in the hobby was a huge asset to me with this approach. Water changes are of critical importance, because they not only export metabolites from this system, but they “reset” the trace elements, minerals, etc. that the coral needs for long-term growth and health. I didn’t dose anything, nor did I test, which was another radical departure from my habits developed over the decades.

Rather, I let the coral “talk” to me, and observed its health carefully. Despite my religious devotion to water testing in reef tanks, I’ve secretly long believed that corals will "tell" you when they are happy, and this approach validated my belief. I can honestly say that I’d never developed such an intimate “relationship” with an individual coral before!

I'd like to try this approach soon with my all-time favorite coral, Pocillopora.

Sure, the "Zero Reef" approach is not the single best way to keep every coral or anemone, and every bare-bottomed, low-diversity aquarium that comes along is not to be enshrined as an affirmation that this is "the best way to keep marine life." In fact, it may not work for some species. The point is, it’s worth investigating and experimenting with. It’s always a good thing to try new technique, new avenues. No matter how simple, or how elementary the approach seems.

I find different ecological approaches to aquarium keeping fascinating. It took a lot of years off observing Nature from not just a "how it looks" standpoint- but from how it works...and synthesizing this information has made me a better hobbyist.

The botanical "method" aquarium is really not a "method." It's literally just Nature, doing Her thing...and us keeping our grubby little hands off of the process!

Eventually, it got through my thick skull that aquariums- just like the wild habitats they represent- have an ecology comprised of countless organisms doing their thing. They depend on multiple inputs of food, to feed the biome at all levels. This meant that scrubbing the living shit (literally) out of our aquariums was denying the very biotia which comprised our aquariums their most basic needs.

That little "unlock" changed everything for me.

Suddenly, it all made sense.

This has carried over into the botanical-method aquarium concept: It's a system that literally relies on the biological material present in the system to facilitate food production, nutrient assimilation, and reproduction of life forms at various trophic levels.

It's changed everything about how I look at aquarium management and the creation of functional closed aquatic ecosystems.

It's really put the word "natural" back into the aquarium keeping parlance for me. The idea of creating a multi-tiered ecosystem, which provides a lot of the requirements needed to operate successfully with just a few basic maintenance practices, the passage of time, a lot of patience, and careful observation.

"Unlocks" are everywhere...the products of our experience, acquired skills, and grand experiments. Stuff that, although initially seemingly trivial, serves to "move the needle" on aquarium practice and shift minds over time,

It's my sincere hope that you will open your mind to the process of experimentation, and share your results with fellow hobbyists as you take your first steps into previously uncharted territory.

Stay bold. Stay provacative. Stay undeterred. Stay curious. Stay humble. Stay diligent...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Scott Fellman

Author