- Continue Shopping

- Your Cart is Empty

Race to the bottom...

.

Substrates, IMHO, are one of the most often-overlooked components of the aquarium. We tend to just add a bag of "_____________" to our tanks and move on to the "more exciting" stuff like rocks and "designer" wood. It's true! Other than planted aquarium enthusiasts, the vast majority of hobbyists seem to have little more than a passing interest in creating and managing a specialized substrate or associated ecology.

And, when we observe natural aquatic ecosystems, I think we as a whole tend to pay scant little attention to the composition of the materials which form the substrate; how they aggregate, and what occurs when they do.

I'm obsessed with the idea of "functionally aesthetic" substrates in our botanical-style aquariums.

It's because I imagine the substrate as this magical place which fuels all sorts of processes within our aquariums, and that Nature tends to it in the most effective and judicious manner.

Yeah, I'm a bit of a "substrate romantic", I suppose.😆

I think a lot of this comes from my long experience with reef aquariums, and the so-called "deep sand beds" that were quite popular in the early 2000's.

A deep sand bed is (just like it sounds) a layer of fine sand on the bottom of the aquarium, intended to grow bacteria in the deepest layers, which convert nitrate or nitrite to nitrogen gas. This process is generically called "denitrification", and it's one of the benefits of having an undisturbed layer of substrate on the bottom of the aquarium.

Fine sand and sediment is a perfect "media" upon which to culture these bacteria, with its abundant surface area. Now, the deep sand bed also serves as a location within the aquarium to process and export dissolved nutrients, sequester detritus (our old friend), and convert fish poop and uneaten food into a "format" that is usable by many different life forms.

In short, a healthy, undisturbed sandbed is a nutrient processing center, a supplemental food production locale, and a microhabitat for aquatic organisms.

You probably already know most of this stuff, especially if you've kept a reef tank before. And of course, there are reefers who absolutely vilify sandbeds, because they feel that they "compete" with corals, and ultimately can "leach" out the unwanted organics that they sequester, back into the aquarium. I personally disagree with that whole thing, but that's another battle for another time and place!

Okay, saltwater diversion aside, the concept of a deep substrate layer in a botanical-style aquarium continues to fascinate me. I think that the benefits for our systems are analogous to those occurring in reef tanks- and of course, in Nature. In my opinion, an undisturbed deep substrate layer in the botanical-style aquarium, consisting of all sorts of materials, from sand/sediments to leaves to twigs and broken-up pieces of botanicals,can foster all sorts of support functions.

I've always been a fan of in my aquarium keeping work of allowing Nature to take its course in some things, as you know. And this is a philosophy which plays right into my love of dynamic aquarium substrates. If left to their own devices, they function in an efficient, almost predictable manner.

Nature has this "thing" about finding a way to work in all sorts of situations.

And, I have this "thing" about not wanting to mess with stuff once it's up and running smoothly... Like, I will engage in regular maintenance (ie; water exchanges, etc.), but I avoid any heavy "tweaks" as a matter of practice. In particular, I tend not to disturb the substrate in my aquariums. A lot of stuff is going on down there...

Amazing stuff.

I realize, when contemplating really deep aggregations of substrate materials in the aquarium, that we're dealing with closed systems, and the dynamics which affect them are way different than those in Nature, for the most part.

And I realize that experimenting with these unusual approaches to substrates requires not only a sense of adventure, a direction, and some discipline- but a willingness to accept and deal with an entirely different aesthetic than what we know and love. And this also includes pushing into areas and ideas which might make us uncomfortable, not just for the way they look, but for what we are told might be possible risks.

One of the things that many hobbyists ponder when we contemplate creating deep, botanical-heavy substrates, consisting of leaves, sand, and other botanical materials is the buildup of hydrogen sulfide, CO2, and other undesirable compounds within the substrate.

Well, it does make sense that if you have a large amount of decomposing material in an aquarium, that some of these compounds are going to accumulate in heavily-"active" substrates. Now, the big "bogeyman" that we all seem to zero in on in our "sum of all fears" scenarios is hydrogen sulfide, which results from bacterial breakdown of organic matter in the total absence of oxygen.

Let's think about this for just a second.

In a botanical bed with materials placed on the substrate, or loosely mixed into the top layers, will it all "pack down" enough to the point where there is a complete lack of oxygen and we develop a significant amount of this reviled compound in our tanks? I think that we're more likely to see some oxygen in this layer of materials, and I can't help but speculate- and yeah, it IS just speculation- that actual de-nitirifcation (nitrate reduction), which lowers nitrates while producing free nitrogen, might actually be able to occur in a "deep botanical" bed.

There is that curious, nagging "thing" I have in my head about the ability of botanical-influenced substrates to foster denitrification. With the diverse assemblage of microorganisms and a continuous food source of decomposing botanicals "in house", I can't help but think that such "living substrates" create a surprisingly diverse and utilitarian biological support system for our aquariums.

And it's certainly possible to have denitrification without dangerous hydrogen sulfide levels. As long as even very small amounts of oxygen and nitrates can penetrate into the substrate, this will not become an issue for most systems. I have yet to see a botanical-style aquarium where the material has become so "compacted" as to appear to have no circulation whatsoever within the botanical layer.

Now, sure, I'm not a scientist, and I base this on close visual inspection of numerous aquariums, and the basic chemical tests I've run on my systems under a variety of circumstances. As one who has made it a point to keep my botanical-method aquariums in operation for very extended time frames, I think this is significant. The "bad" side effects we're talking about should manifest over these longer time frames...and they just haven't.

And then there's the question of nitrate.

Although not the terror that ammonia and nitrite are known to be, nitrate is much less so. However, as nitrate accumulates, fish will eventually suffer some health issues. Ideally, we strive to keep our nitrate levels no higher than 5-10ppm in our aquariums. As a reef aquarist, I've always been of the "...keep it as close to zero as possible." mindset (that's evolved in recent years, btw), but that is not always the most realistic or achievable target in a heavily-botanical-laden aquarium. You have a bit more "wiggle room", IMHO. Now, when you start creeping towards 50ppm, you're getting closer towards a number that should alert you. It's not a big "stretch" from 50ppm to 75ppm and higher...

And then you get towards the range where health issues could manifest themselves in your fishes. Now, many fishes will not show any symptoms of nitrate poisoning until the nitrate level reaches 100 ppm or more. However, studies have shown that long-term exposure to concentrations of nitrate stresses fishes, making them more susceptible to disease, affecting their growth rates, and inhibiting spawning in many species.

At those really high nitrate levels, fishes will become noticeably lethargic, and may have other health issues that are obvious upon visual inspection, such as open sores or reddish patches on their skin. And then, you'd have those "mysterious deaths" and the sudden death (essentially from shock) of newly-added fishes to the aquarium, because they're not acclimated to the higher nitrate concentrations.

Okay, that's scary stuff. However, high nitrate concentrations are not only manageable- they're something that's completely avoidable in our aquairums.

Quite honestly, even in the most heavily-botanical-laden systems I've played with, I have personally never seen a higher nitrate reading than around 5ppm. I attribute this to common sense stuff: Good quality source water (RO/DI), careful stocking, feeding, good circulation, not disturbing the substrate, and consistent basic aquarium husbandry practices (water changes, filter maintenance, etc.).

Now, that's just me. I'm no scientist, certainly not a chemist, but I have a basic understanding of maintaining a healthy nitrogen cycle in the aquarium. And I am habitual-perhaps even obsessive- about consistent maintenance. Water exchanges are not a "when I get around to it" thing in my aquarium management "playbook"- they're "baked in" to my practice.

And I think that a healthy, ecologically varied substrate is one of the keys to a successful botanical method aquarium.

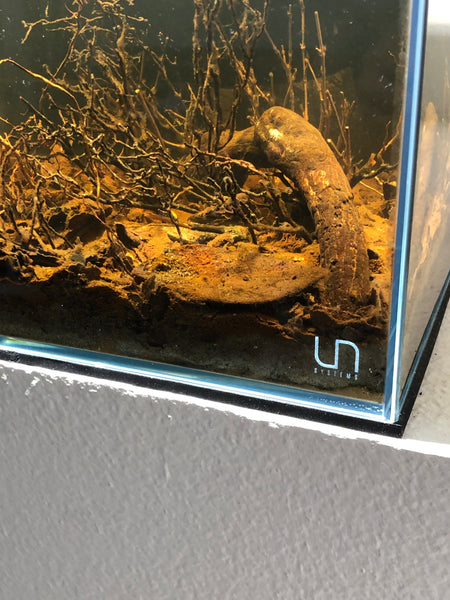

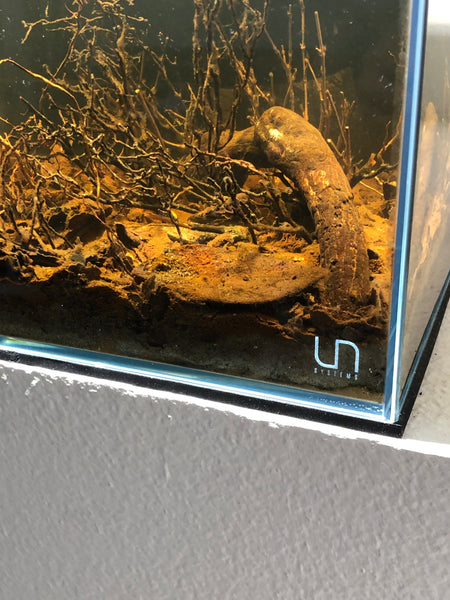

I'm really into creating substrates that are a reasonable representation of the bottom of streams, tributaries, and igapo, as found in the Amazon basin. Each one of these has some unique characteristics, and each one presents an interesting creative challenge for the intrepid hobbyist. Until quite recently, the most common materials we had to work with when attempting to replicate these substrates were sand, natural and colored gravels, and clay-comprised planted aquarium substrates.

I reiterate a "manifesto" of sorts that I played out in "The Tint" back in 2015:

"If I have something to say about the matter, you'll soon be incorporating a wide variety of other materials into your biotope aquarium substrate!"

Damn, did I just quote myself?

I did!

If you've seen pictures and videos taken underwater in tropical streams (again, I'm pulling heavily from the Amazonian region), you'll note that there is a lot of loose, soil-like material over a harder mud/sand substrate. Obviously, using an entirely soil-based substrate in an aquarium, although technically possible and definitely cool- could result in a yucky mess whenever you disturb the material during routine maintenance and other tasks. You can, however, mix in some of these materials with the more commonly found sand.

So, exactly what "materials" am I referring to here?

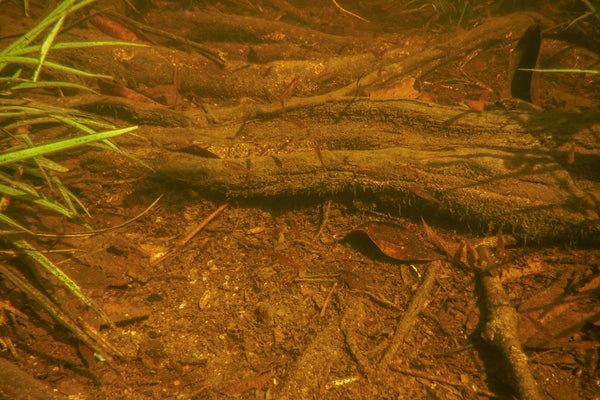

Well, let's look at Nature for a second.

Natural streams, lakes, and rivers typically have substrates comprised of materials of multiple "grades", including fine, medium, and coarse materials, such as pebbles, gravels, silty clays and sands. In the aquarium, we seem to have embraced the idea of a homogenous particle size for our substrates for many years. Now, don't get me wrong- it's aesthetically just fine, and works great. However, it's not always the most interesting to look at, nor is it necessarily the most biologically diverse are of the aquarium.

A lot of natural stream bottoms are complimented with aggregations of other materials like leaf litter, branches, roots, and other decomposing plant matter, creating a dynamic, loose-appearing substrate, with lots of potential for biological benefits. Of course, we need to understand the implications of creating such "dynamic" substrates in our closed aquariums.

When we started Tannin, my fascination with the varied substrate materials of tropical ecosystems got me thinking about ways to more accurately replicate those found in flooded forests, streams, and diverse habitats like peat swamps, estuaries, creeks, even puddles- and others which tend to be influenced as much by the surrounding flora (mainly forests and jungles) as it is by geology.

And of course, my obsession with botanical materials to influence and accent the aquarium habitat caused me to look at the use of certain materials for what I generically call "substrate enrichment" - adding materials reminiscent of those found in the wild to augment the more "traditional" sands and other substrates used in aquariums to foster biodiversity and nutrient processing functions.

Again, look to Nature...

If you've seen pictures and videos taken underwater in tropical streams (again, I'm pulling heavily from the Amazonian region), you'll note that there is a lot of loose, soil-like material over a harder mud/sand substrate. Obviously, using an entirely mud-based substrate in an aquarium, although technically possible- will result in a yucky mess whenever you disturb the material during routine maintenance and other tasks. You can, however, mix in some other materials with the more commonly found sand.

That was the whole thinking behind "Substrato Fino" and "Fundo Tropical", two of our most popular substrate "enrichment" materials. They are perfect for helping to more realistically replicate both the look and function of the substrates found in some of these natural habitats. They provide surface area for fungal and microbial growth, and interstitial spaces for smalll crustaceans and other organisms to forage upon.

Substrates aren't just "the bottom of the tank..."

Rather, they are diverse harbors of life, ranging from fungal and biofilm mats, to algae, to epiphytic plants. Decomposing leaves, seed pods, and tree branches compose the substrate for a complex web of life which helps the fishes were so fascinated by flourish. And, if you look at them objectively and carefully, they are beautiful.

I encourage you to study the natural environment, particularly niche habitats or areas of the streams, rivers, and lakes- and draw inspiration from the functionality of these zones. The aesthetic component will come together virtually by itself. And accepting the varied, diverse, not-quite-so-pritinh look of the "real thing" will give you a greater appreciation for the wonders of nature, and unlock new creative possibilities.

In regards to the substrate materials themselves, I'm fascinated by the different types of soils or substrate materials which occur in blackwater systems and their clearwater counterparts, and how they influence the aquatic environment.

For example, as we've discussed numerous times over the years, "blackwater" is not cased by leaves and such- it's created via geological processes.

In general, blackwaters originate from sandy soils. High concentrations of humic acids in the water are thought to occur in drainages with what scientists call "podzol" sandy soils. "Podzol" is a soil classification which describes an infertile acidic soil having an "ashlike" subsurface layer from which minerals have been leached.

That last part is interesting, and helps explain in part the absence of minerals in blackwater. And more than one hobbyist I know has played with the concept of "dirted" planted tanks, using terrestrial soils...hmmm.

Also interesting to note is that fact that soluble humic acids are adsorbed by clay minerals in what are known as"oxisol" soils, resulting in clear waters."Oxisol" soils are often classified as "laterite" soils, which some who grow plants are familiar with, known for their richness in iron and aluminum oxides. I'm no chemist, or even a planted tank geek..but aren't those important elements for aquatic plants?

Yeah.

Interesting.

Let's state it one more time:

We have the terrestrial environment influencing the aquatic environment, and fishes that live in the aquatic environment influencing the terrestrial environment! T

his is really complicated stuff- and interesting! And the idea that terrestrial environments and materials influence aquatic ones- and vice-versa- is compelling and could be an interesting area to contemplate for us hobbyists!

When ecologists study the substrate composition of aquatic habitats like those in The Amazon, they tend to break them down into several categories, broad though they may be: Rock, sand, coarse leaf litter, fine leaf litter, and branches, trunks and roots.

Studies indicate that terrestrial inputs from rainforest streams provide numerous benefits for fishes, providing a wide range of substrate materials that supported a wider range of fishes than can be found in non-forested streams. One study concluded that, "Inputs from forests such as woody debris and leaf litter were found to support a diversity of habitat niches that can provide nursing grounds and refuges against predators (Juen et al. 2016). Substrate size was also larger in forest stream habitats, adding to the complexity and variety of microhabitats that can accommodate a greater and more diverse range of fish species (Zeni et al. 2019)."

But wait- there's more! Rainforests create uniquely diverse aquatic habitats.

"Forests can further diversify and stabilize the types of food available for fish by supplying both allochthonous inputs from leaf litter and increased availability of terrestrial insects that fall directly into the water (Zeni and Casatti). Forest habitats can support a diverse range of trophic guilds including terrestrial insectivores and herbivores (Zeni and Casatti).

Riparian forests deliver leaf litter in streams attracting insects, algae, and biofilm, each of which may be vital for particular fish species (Giam et al., Juen et al. ). In contrast, nonforested streams may lack the allochthonous food inputs that support terrestrial feeding fish species..."

Leaf litter- yet again.

And then there are soils...terrestrial soils- which, to me, are to me the most interesting possible substrates in wild aquatic habitats.

So, the idea of a rich soil substrate that not only accommodates the needs of the plants, but provides a "media" in which beneficial bacteria can grow and multiply is a huge "plus" for our closed aquatic ecosystems. And the concepts of embracing Nature and her processes work really well with the stuff we are playing with.

As you've seen over the past few years, I've been focusing a lot on my long-running "Urban Igapo" idea and experiments, sharing with you my adventures with rich soils, decomposing leaf litter, tinted water, immersion-tolerant terrestrial plants, and silty, muddy, rich substrates. This is, I think, an analogous or derivative concept to the "Walstad Method", as it embraces a more holistic approach to fostering an ecosystem; a "functionally aesthetic" aquarium, rather than a pure aesthetic one.

The importance of incorporating rich soils and silted substrates is, I think, an entirely new (and potentially dynamic) direction for blackwater/botanical-style tanks, because it not only embraces the substrate not just as a place to throw seed pods, wood, rocks, and plants- but as the literal foundation of a stable, diverse ecosystem, which facilitates the growth of beneficial organisms which become an important and integral part of the aquarium.

And that has inspired me to spend a lot of time over the past couple of years developing more "biotope-specific" substrates to compliment the type of aquariums we play with.

When we couple this use of non-conventional (for now, anyways...) substrate materials with the idea of "seeding" our aquariums with beneficial organisms (like small crustaceans, worms, etc.) to serve not only as nutrient processing "assistants", but to create a supplementary food source for our fishes, it becomes a very cool field of work.

As creatures like copepods and worms "work" the substrate and aerate and mix it, they serve to stabilize the aquarium and support the overall environment.

Nutrient cycling.

That's a huge takeaway here. I'm sure that's perhaps the biggest point of it all. By allying with the benthic life forms which inhabit it, the substrate can foster decomposition and "processing"of a wide range of materials- to provide nutrition for plants- or in our case- for the microbiome of the overall system.

There is so much work to do in this area...it's really just beginning in our little niche. And, how funny is it that what seems to be an approach that peaked and fell into a bit of disfavor or perhaps (unintended) "reclassification"- is actually being "resurrected" in some areas of the planted aquarium world ( it never "died" in others...).

And a variation/application of it is gradually starting to work it's way into the natural, botanical-method aquarium approach that we favor.

Substrates are not just "the bottom."

They are diverse harbors of life, ranging from fungal and biofilm mats, to algae, to epiphytic plants. Decomposing leaves, seed pods, and tree branches compose the substrate for a complex web of life which helps the fishes we're so fascinated by to flourish.

And, if you look at them objectively and carefully, they are beautiful.

Stay curious. Stay ob servant. Stay thoughtful. Stay bold...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquaitcs

"Operating" our aquariums with seasonal and ecological practices.

One of the great joys in creating and working with botanical method aquairums is that we have such a wide variety of natural habitats to take inspiration from. And, as we've discussed here over the years, it's not just types of natural aquatic habitats or specific locales- it's seasons and cycles that we can emulate in our tanks as well.

I find it fascinating to think about how we can emulate the environmental characteristics of aquatic habitats during certain times of the year, such as the "wet" and "dry" seasons...and the idea of actually "operating" your aquarium to spur the environmental changes which take place during these transitions.

Do we create true seasonal variations for our aquariums? I mean, changing up lighting duration, intensity, angles, colors, increasing/decreasing water levels or flow?

With all of the high tech LED lighting systems, electronically controlled pumps; even programmable heaters- we can vary environmental conditions to mimic what occurs in our fishes' natural habitats during seasonal changes as never before. I think it would be very interesting to see what kinds of results we could get with our fishes if we went further into environmental manipulations than we have been able to before.

I mean, sure, hobbyists have been dropping or increasing temps for spawning fishes forever, and you'll see hobbyists play with light durations. Ask any Corydoras breeder. However, these are typically only in the context of defined controlled breeding experiments.

Why not simply research and match the seasonal changes in their habitat and vary them accordingly "just because", and see if you achieve different results?

We've examined the interesting Igapo and Varzea habitats of The Amazon for years now, and how these seasonally-inundated forest floors ebb and flow with aquatic life during various seasons.

And, with the "Urban Igapo", we've "operated" tanks on "wet season/dry season" cycles for a few years now, enjoying very interesting results.

I think it would be pretty amazing to incorporate gradual seasonal changes in our botanical method aquariums, to slowly increase/decrease water levels, temperature, and lighting to mimic the rainy/dry seasonal cycles which affect this habitat.

What secrets could be unlocked?

How would you approach this?

You'd need some real-item or historical weather data from the area which you're attempting to replicate, but that's readily available from multiple sources online. Then, you could literally tell yourself during the planning phases of your next tank that, "This aquarium will be set up to replicate the environmental conditions of the Igarape Panemeo in May"- and just run with it.

What are some of the factors that you'd take into account when planning such a tank? Here are just a few to get you started:

-water temperature

-ph

-water depth

-flow rate

-lighting conditions

-percentage of coverage of aquatic plants (if applicable)

-substrate composition and depth

-leaf litter accumulation

-density of fish population

-diversity of fish population

-food types

...And the list can go on and on and on. The idea being to not just "capture a moment in time" in your aquarium, but to pick up and run with it from there!

Yes, we love the concept of seasonality in our botanical method world- but not just because they create interesting aesthetic effects- but because replicating seasonal changes brings out interesting behaviors and may yield health benefits for our fishes that we may have not previously considered.

The implications of seasonality in both the natural environment- and, I believe- in our aquariums- can be quite profound.

Amazonian seasonality, for example, is marked by river-level fluctuation, also known as "seasonal pulses." The average annual river-level fluctuations in the Amazon Basin can range from approximately 12'-45' /4–15m!!! Scientists know this, because River-water-level data has been collected in some parts of the Brazilian Amazon for more than a century! The larger Amazonian rivers fall into to what is known as a “flood pulse”, and are actually due to relatively predictable tidal surge.

And of course, when the water levels rise, the fish populations are affected in many ways. Rivers overflow into surrounding forests and plains, turning the formerly terrestrial landscape into an aquatic habitat once again.

Besides just knowing the physical environmental impacts on our fishes' habitats, what can we learn from these seasonal inundations?

Well, for one thing, we can observe their impact on the diets of our fishes.

In general, fish/invertebrates, detritus and insects form the most important food resources supporting the fish communities in both wet and dry seasons, but the proportions of invertebrates, fruits, and fish are reduced during the low water season. Individual fish species exhibit diet changes between high water and low water seasons in these areas...an interesting adaptation and possible application for hobbyists?

Well, think about the results from one study of gut-content analysis form some herbivorous Amazonian fishes in both the wet and dry seasons: The consumption of fruits in Mylossoma and Colossoma species (big ass fishes, I know) was significantly less during the low water periods, and their diet was changed, with these materials substituted by plant parts and invertebrates, which were more abundant.

Tropical fishes, in general, change their diets in different seasons in these habitats to take advantage of the resources available to them.

Fruit-eating, as we just discussed, is significantly reduced during the low water period when the fruit sources in the forests are not readily accessible to the fish. During these periods of time, fruit eating fishes ("frugivores") consume more seeds than fruits, and supplement their diets with foods like leaves, detritus, and plankton.

Interestingly, even the known "gazers", like Leporinus, were found to consume a greater proportion of materials like seeds during the low water season.

The availability of different food resources at different times of the year will necessitate adaptability in fishes in order to assure their survival. Mud and algal growth on plants, rocks, submerged trees, etc. is quite abundant in these waters at various times of the year. Mud and detritus are transported via the overflowing rivers into flooded areas, and contribute to the forest leaf litter and other botanical materials, becoming nutrient sources which contribute to the growth of this epiphytic algae.

During the lower water periods, this "organic layer" helps compensate for the shortage of other food sources. And of course, this layer comprises an ecological habitat for a variety of organisms at multiple "trophic levels."

And of course, there's the "allochthonous input"- materials imported into the habitat from outside of it...When the water is at a high period and the forests are inundated, many terrestrial insects fall into the water and are consumed by fishes. In general, insects- both terrestrial and aquatic, support a large community of fishes.

So, it goes without saying that the importance of insects and fruits- which are essentially derived from the flooded forests, are reduced during the dry season when fishes are confined to open water and feed on different materials, as we just discussed.

And in turn, fishes feed on many of these organisms. The guys on the lower end of the food chain- bacterial biofilms, algal mats, and fungal growths, have a disproportionately important role in the food webs in these habitats! In fact, fungi are the key to the food chain in many tropical stream ecosystems. The relatively abundant detritus produced by the leaf litter is a very important part of the tropical stream food web.

Interestingly, some research has suggested that the decomposition of leaf litter in igapo forests is facilitated by terrestrial insects during the "dry phase", and that the periodic flooding of this habitat actually slows down the decomposition of the leaf litter (relatively speaking) because of the periodic elimination of these insects during the inundation.

And, many of the organisms which survive the inundation feed off of the detritus and use the leaf substratum for shelter instead of directly feeding on it, further slowing down the decomposition process.

AsI just touched on, much of the important input of nutrients into these habitats consists of the leaf litter and of the fungi that decompose this litter, so the bulk of the fauna found there is concentrated in accumulations of submerged litter.

And the nutrients that are released into the water as a result of the decomposition of this leaf litter do not "go into solution" in the water, but are tied up throughout in the "food web" comprised of the aquatic organisms which reside in these habitats.

This concept is foundational to our interpretation of the botanical method aquarium.

So I wonder...

Is part of the key to successfully conditioning and breeding some of the fishes found in these habitats altering their diets to mimic the seasonal importance/scarcity of various food items? In other words, feeding more insects at one time of the year, and perhaps allowing fishes to graze on detritus and biocover at other times?

And, you probably already know the answer to this question:

Is the concept of creating a "food producing" aquarium, complete with detritus, natural mud, and an abundance of decomposing botanical materials, a key to creating a more true realistic feeding dynamic, as well as an "aesthetically functional" aquarium?

Well, hell yes!

On a practical level, our botanical method aquariums function much like the habitats which they purport to represent, famously recruit biofilm and fungal growths, which we have discussed ad nasueum here over the years. These are nutritious, natural food sources for most fishes and invertebrates.

And of course, there are the associated microorganisms which feed on the decomposing botanicals and leaves and their resulting detritus.

Having some decomposing leaves, botanicals, and detritus helps foster supplemental food sources. Period.

And you don't need special botanicals, leaves, curated packs of botanicals, additives, or gear from us or anyone to create the stuff! Nature will do it all for you using whatever botanical materials you add to your aquarium!

Apparently, the years of us beating this shit into your head here on "The Tint" and elsewhere are finally striking a chord. There are literally people posting pics of their botanical method aquariums on social media every week with hashtags like #detriusthursday or whatever, preaching the benefits of the stuff that we've reviled as a hobby for a century!

That absolutely cracked me up the first time I saw people posting that. Five years ago, people literally called me an idiot online for telling hobbyists to celebrate the stuff...Now, it's a freaking hashtag. It's some weird shit, I tell you...gratifying to see, but really weird!

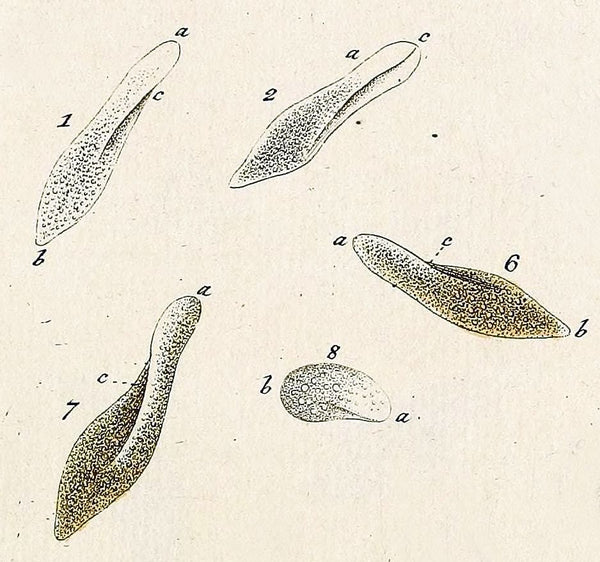

Now, we've briefly talked about how decomposing leaf litter and the resulting detritus it produces supports population of "infusoria"- a collective term used to describe minute aquatic creatures such as ciliates, euglenoids, protozoa, unicellular algae and small invertebrates that exist in freshwater ecosystems.

And there is much to explore on this topic. It's no secret, or surprise- to most aquarists who've played with botanicals, that a tank with a healthy leaf litter component is a pretty good place for the rearing of fry of species associated with blackwater environments!

It's been observed by many aquarists, particularly those who breed loricariids, gouramis, bettas, and characins, that the fry have significantly higher survival rates when reared in systems with leaves and other botanical present. This is significant...I'm sure some success from this could be attributed to the population of infusoria, etc. present within the system as the leaves break down.

And the insights gained by seeing first hand how fishes have adapted to the seasonal changes, and have made them part of their life cycle are invaluable to our aquarium practice.

It's an oft-repeated challenge I toss out to you- the adventurers, innovators, and bold practitioners of the aquarium hobby: follow Nature's lead whenever possible, and see where it takes you. Leave no leaf unturned, no piece of wood unstudied...push out the boundaries and blur the lines between Nature and aquarium.

Follow the seasons.

And place the aesthetic component of our botanical method aquarium practice at a lower level of importance than the function.

I'm fairly certain that this idea will make me even less popular with some in the aquarium hobby crowd who feel that the descriptor of "natural" is their exclusive purview, and that aesthetics reign supreme..Hey, I love the look of well-crafted tanks as much as anyone...but let's face it, a truly "natural" aquarium needs to embrace stuff like detritus, mud, decomposing botanical materials, varying water tint and clarity, etc.

Yes, the aesthetics of botanical method tanks might not be everyone's cup of tea, but the possibilities for creating more self-sustaining, ecologically sound microcosms are numerous, and the potential benefits for fishes are many.

It goes back to some of the stuff we've talked about before over the years here, like "pre-stocking"aquariums with lower life forms before adding your fishes- or at least attempting to foster the growth of aquatic insects and crustaceans, encouraging the complete decomposition of leaves and botanical materials, allowing biocover ("aufwuchs") to accumulate on rocks, substrate, and wood within the aquarium, utilization of a refugium, etc.during the startup phases of your tank.

All of these things are worth investigating when we look at them from a "functionality" perspective, and make the "mental shift" to visualize why a real aquatic habitat looks like this, and how its elegance and natural beauty can be every bit as attractive as the super pristine, highly-controlled, artificially laid out "plant-centric" 'scapes that dominate the minds of most aquarists when they hear the words "natural" and "aquarium" together!

Particularly when the "function" provides benefits for our animals that we wouldn't appreciate , or even see- otherwise.

At Tannin, we've pushed rather unconventional hobby viewpoints since our founding in 2015. As an aquarist, I've had these viewpoints on the hobby for decades. A desire to accept the history of our hobby, to understand how "best practices" and techniques came into being, while being tempered by a strong desire to question and look at things a bit differently. To see if maybe there's a different- or perhaps-better-way to accomplish stuff.

Most of my time in the hobby has been occupied by looking at how Nature works, and seeing if there is a way to replicate some of Her processes in the aquarium, despite the aesthetics of the processes involved, or even the results.

As a result, I've learned to appreciate Nature as She is, and have long ago given up much of my "aquarium-trained" sensibilities to "edit" or polish out stuff I see in my aquariums, simply because it doesn't fit the prevailing aesthetic sensibilities of the aquarium hobby. Now, it doesn't mean that I don't care how things look...of course not!

Rather, it means that I've accepted a different aesthetic- one that, for better or worse in some people's minds- more accurately reflects what natural aquatic habitats really look like.

And the idea of replicating the seasonal changes in our aquariums is driven not primarily from aesthetics- but from function.

To sort of put a bit of a bow on this now rather unwieldy discussion about fostering and managing our own versions of seasonal ecological systems in our aquariums, let's just revisit once again how botanical materials accomplish this in our aquariums.

The idea that we are adding these materials not only to influence the aquatic environment in our aquariums, but to provide food and sustenance for a wide variety of organisms, not just our fishes. The fundamental essence of the botanical-method aquarium is that the use of these materials provide the foundation of an ecosystem.

The essence.

Just like they are in Nature.

And the primary process which drives this closed ecosystem is... decomposition.

Decomposition of leaves and botanicals not only imparts the substances contained within them (lignin, organic acids, and tannins, just to name a few) to the water- it serves to nourish bacteria, fungi, and other microorganisms and crustaceans, facilitating basic "food web" within the botanical-method aquarium- if we allow it to!

Decomposition of plant matter-leaves and botanicals- occurs in several stages.

It starts with leaching -soluble carbon compounds are liberated during this process. Another early process is physical breakup or fragmentation of the plant material into smaller pieces, which have greater surface area for colonization by microbes.

And of course, the ultimate "state" to which leaves and other botanical materials "evolve" to is our old friend...detritus.

And of course, that very word- as we've mentioned many times here, including just minutes ago- has frightened and motivated many hobbyists over the years into removing as much of the stuff as possible from their aquariums whenever and wherever it appears.

Siphoning detritus is a sort of "thing" that we are asked about near constantly. This makes perfect sense, of course, because our aquariums- by virtue of the materials they utilize- produce substantial amounts of this stuff.

Now, the idea of "detritus" takes on different meanings in our botanical-method aquariums...Our "aquarium definition" of "detritus" is typically agreed to be dead particulate matter, including fecal material, dead organisms, mucous, etc.

And bacteria and other microorganisms will colonize this stuff and decompose/remineralize it, essentially "completing" the cycle.

And, despite their impermanence, these materials function as diverse harbors of life, ranging from fungal and biofilm mats, to algae, to micro crustaceans and even epiphytic plants. Decomposing leaves, seed pods, and tree branches make up the substrate for a complex web of life which helps the fishes that we're so fascinated by flourish throughout the various seasons.

And, if you look at them objectively and carefully, these assemblages-and the processes which form them- are beautiful. We would be well-advised to let them do their work unmolested.

On a purely practical level, these processes accomplish the most in our aquariums if we let Nature do her work without excessive intervention.

An example? How about our approach towards preparing natural materials for use in our tanks:

After decades of playing with botanical method aquariums, I'm thinking that we should do less and less preparation of certain botanical materials-specifically, wood- to encourage a slower breakdown and colonization by beneficial bacteria and fungal growths.

The "rap" on wood has always been that it gives off a lot of tint-producing tannins, much to the collective freak-out of non-botanical-method aquarium fans. However, to us, all those extra tannins are not much of an issue, right? Weigh down the wood, and let it "cure" in situ before adding your fishes!

And then there is the whole concept of getting fishes into the tank as quickly as possible.

Like, why?

We should slow our roll.

I've written and spoken about this idea before, as no doubt many of you have: Adding botanical materials to your tank, and "pre-colonizing"with beneficial life forms BEFORE you ever think of adding fishes. A way to sort of get the system "broken in", with a functioning little "food web" and some natural nutrient export processes in place.

A chance for the life forms that would otherwise likely fall prey to the fishes to get a "foothold" and multiply, to help create a sustainable population of self-generating prey items for your fishes.

And that's a fundamental thing for us "recruiting" and nurturing the community of organisms which support our aquariums. The whole foundation of the botanical-method aquarium is the very materials- botanicals, soils, and wood- which comprise the "infrastructure" of our aquariums.The botanicals create a physical and chemical environment which supports these life forms, allowing them to flourish and support the life forms above them.

From there, we can "operate" our aquariums in any manner of ways.

Nature provides some really incredible inspiration for this stuff, doesn't it? Marshland and flooded plains and forests along rivers are like the "poster children" for seasonal change in the tropics.

Flood pulses in these habitats easily enable large-scale "transfers" of nutrients and food items between the terrestrial and aquatic environment. This is of huge importance to the ecosystem. As we've touched on before, aquatic food webs in the Amazon area (and in other tropical ecosystems) are very strongly influenced by the input of terrestrial materials, and this is really an important point for those of us interested in creating more natural aquatic displays and microcosms for the fishes we wish to keep.

Because the aquatic ecology is driven by the surrounding terrestrial habitats seasonally, the impact of leaves which fall into the aquatic habitats is very important.

What makes leaves fall off the trees in the first place? Well, it's simple- er, rather complex...but I suppose it's simple, too. Essentially, the tree "commands" leaves to fall off the tree, by creating specialized cells which appear where the leaf stem of the leaves meet the branches. Known as "abscission" cells. for word junkies, they actually have the same Latin root as the word "scissors", which, of course, implies that these cells are designed to make a cut!

And, in the tropical species of trees, the leaf drop is important to the surrounding environment. The nutrients are typically bound up in the leaves, so a regular release of leaves by the trees helps replenish the minerals and nutrients which are typically depleted from eons of leaching into the surrounding forests.

And the rapid nutrient depletion, by the way, is why it's not healthy to burn tropical forests- the release of nutrients as a result of fire is so rapid, that the habitat cannot process it, and in essence, the nutrients are lost forever.

Now, interestingly enough, most tropical forest trees are classified as "evergreens", and don't have a specific seasonal leaf drop like the "deciduous" trees than many of us are more familiar with do...Rather, they replace their leaves gradually throughout the year as the leaves age and subsequently fall off the trees.

The implication here?

There is a more-or-less continuous "supply" of leaves falling off into the jungles and waterways in these habitats throughout the year, which is why you'll see leaves at varying stages of decomposition in tropical streams. It's also why leaf litter banks may be almost "permanent" structures within some of these bodies of water!

Here's an easy "seasonal" experiment for you to try:

Manage and replicate this in the aquarium by adding leaves at different times of the year..increasing the quantities in some months and backing off during others. It's a relatively simple process with possible profound implications for aquariums.

And it makes me wonder...

What if we stopped replacing leaves and even lowered water levels or decreased water exchanges in our tanks to correspond to, for example, the Amazonian dry season (June to December)? What would it do?

If you consider that many fishes tend to spawn in the "dry" season, concentrating in the shallow waters, could this have implications for breeding or growth in fishes?

I think so.

Just a few easy ideas...each with a promise and a potential to change the way we manage botanical method aquariums, and impact the way we look at so-called "natural" aquariums in the first place!

And, with all of the research data from the wild habitats of our fishes available easier than ever before, the time is right to start these bold experiments!

Obviously, there is still much to learn, and of course, the bigger question that many will ask, "What is the advantage?"

Well, that's all part of the fun...we can play a hunch, but we won't know for certain until we really delve into this stuff!

Who's in?

Stay thoughtful. Stay curious. Stay engaged. Stay innovative. Stay diligent...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

As the seasons pass...

Every Corydoras breeder knows something that we all should know:

Environmental manipulations create unique opportunities to facilitate behavioral changes in our fishes.

It's hardly an earth-shattering idea in the aquarium hobby, but I think that the concept of "seasonal" environmental manipulation deserves some additional consideration.

It's been known for decades that environmental changes to the aquatic environment caused by weather (particularly "wet" or "dry" seasons/events) can stimulate fishes into spawning.

As a fish geek keen on not only replicating the look of our fishes' wild habitats, but as much of the "function" as possible, I can't help myself but to ponder the possibilities for greater success by manipulating the aquarium environment to simulate what happens in the wild.

Probably the group of aquarists who has had the most experience and success at incorporating such environmental manipulations into their breeding procedures is Corydoras catfish enthusiasts!

Many hobbyists who have bred Corydoras utilize the old trick of a 20%-30% water exchange with water that is up to 10° F cooler (6.5° C) than the aquarium water is normally maintained at. It seems almost like one of those, "Are you &^%$#@ crazy- a sudden lowering of temperature?"

However, it works, and you almost never hear of any fishes being lost as a result of such manipulations.

I often wondered what the rationale behind such a change was. My understanding is that it essentially is meant to mimic a rainstorm, in which an influx of cooler water is a feature. Makes sense. Weather conditions are such an important part of the life cycle of our fishes.

Still others attempt to simulate a "dry spell" by allowing the water quality to "degrade" somewhat (what exactly that means is open to interpretation!), while simultaneously increasing the aquarium temperature a degree or two. This is followed by a water exchange with softer water (ie; pure RO/DI), and resetting the tank temp to the tank's normal range of parameters.

The "variation" I have heard is to do the above procedure, accompanied by an increase in current via a filter return or powerhead, which simulates the increased water volume/flow brought on by the influx of "rain."

Clever.

Many breeders will fast their fishes a few days, followed by a big binge of food after the temperature drop, apparently simulating the increased amount of food in the native waters when rains come.

Still other hobbyists will reduce the pH of their aquarium water to stimulate breeding. And I suppose the rationale behind this is once again to simulate an influx of water from rain or other external sources...

Weather, once again.

And another trick I hear from my Cory breeder friends from time to time is the idea of tossing in a few alder cones into the tank/vessel where their breeders' eggs are incubating.

This decades-old practice is justified by the assertion that the alder cones possess some type of anti-fungal properties...not entirely off base with some of the scientific research we've found about the allegedly anti-microbial/antifungal properties of catappa leaves and such...

And of course, I hear/read of recommendations to use the aforementioned catappa leaves, oak leaves, and Magnolia leaves for just this purpose...

Interesting.

Okay, cool.

Not really earth-shattering; however, it got me thinking about the whole idea of environmental manipulations as part of the routine "operation" of our botanical-mehtod aquariums.....Should we create true seasonal variations for our aquariums as part of our regular practice- not just when trying to spawn fishes? I mean, changing up lighting duration, intensity, angles, colors, increasing/decreasing water levels or flow?

With all of the high tech LED lighting systems, electronically controlled pumps; even advanced heaters- we can vary environmental conditions to mimic what occurs in our fishes' natural habitats during seasonal changes as never before. I think it would be very interesting to see what kinds of results we could get with our fishes if we went further into seasonal environmental manipulations than we have been able to before.

And of course, if we look at the natural habitats where many of our fishes originate, we see these seasonal changes having huge impact on the aquatic ecosystems. In The Amazon, for example, the high water season runs December through April.

And during the flooding season, the average temperature is 86 degrees F, around 12 degrees cooler than the dry season. And during the wet season, the streams and rivers can be between 6-7 meters higher on the average than they are during the dry season!

And of course, there are more fruits, flowers, and insects during this time of year- important food items for many species of fishes.

And the dry season? Well, that obviously means lower water levels, higher temperatures, and abundance of fishes, most engaging in spawning activity.

Mud and algal growth on plants, rocks, submerged trees, etc. is quite abundant in these waters at various times of the year. Mud and detritus are transported via the overflowing rivers into flooded areas, and contribute to the forest leaf litter and other botanical materials, coming nutrient sources which contribute to the growth of this epiphytic algae.

During the lower water periods, this "organic layer" helps compensate for the shortage of other food sources. When the water is at a high period and the forests are inundated, many terrestrial insects fall into the water and are consumed by fishes. In general, insects- both terrestrial and aquatic, support a large community of fishes.

So, it goes without saying that the importance of insects and fruits- which are essentially derived from the flooded forests, are reduced during the dry season when fishes are confined to open water and feed on different materials.

So I wonder...is part of the key to successfully conditioning and breeding some of the fishes found in these habitats altering their diets to mimic the seasonal importance/scarcity of various food items? In other words, feeding more insects at one time of the year, and perhaps allowing fishes to graze on detritus and biocover at other times?

And then, there are those fishes whose life cycle is intimately tied into the seasonal changes.

The killifishes.

Any annual or semi-annual killifish species enthusiast will tell you a dozen ways to dry-incubate eggs; again, a beautiful simulation of what happens in Nature...So much of the idea can be applicable to other areas of aquarium practice, right?

Yeah... I think so.

It's pretty clear that factors such as the air, water and even soil temperatures, atmospheric humidity, the water level, the local winds as well as climatic variables have profound influence on the life cycle and reproductive behavior on the fishes that reside in these dynamic tropical environments!

In my "Urban Igapo" experiments, we get to see a little microcosm of this whole seasonal process and the influences of "weather."

And of course, all of this ties into the intimate relationship between land and water, doesn't it?

There's been a fair amount of research and speculation by both scientists and hobbyists about the processes which occur when terrestrial materials like leaves and botanical items enter aquatic environments, and most of it is based upon field observations.

As hobbyists, we have a unique opportunity to observe firsthand the impact and affects of this material in our own aquariums! I love this aspect of our "practice", as it creates really interesting possibilities to embrace and create more naturally-functioning systems, while possibly even "validating" the field work done by scientists!

And of course, there are a lot of interesting bits of information that we can interpret from Nature when planning, creating, and operating our aquariums.

It goes without saying that there are implications for both the biology and chemistry of the aquatic habitats when leaves and other botanical materials enter them. Many of these are things that we as hobbyists observe every day in our aquariums!

Example?

A lab study I came upon found out that, when leaves are saturated in water, biofilm is at it's peak when other nutrients (i.e.; nitrate, phosphate, etc.) tested at their lowest limits. This is interesting to me, because it seems that, in our botanical method aquariums, biofilms tend to occur early on, when one would assume that these compounds are at their highest concentrations, right? And biofilms are essentially the byproduct of bacterial colonization, meaning that there must be a lot of "food" for the bacteria at some point if there is a lot of biofilm, right?

More questions...

Does this imply that the biofilms arrive on the scene and peak out really quickly; an indication that there is actually less nutrient in the water? Is the nutrient bound up in the biofilms? And when our fishes and other animals consume them, does this provide a significant source of sustenance for them?

Hmm...?

Oh, and here is another interesting observation:

When leaves fall into streams, field studies have shown that their nitrogen content typically will increase. Why is this important? Scientists see this as evidence of microbial colonization, which is correlated by a measured increase in oxygen consumption. This is interesting to me, because the rare "disasters" that we see in our tanks (when we do see them, of course, which fortunately isn't very often at all)- are usually caused by the hobbyist adding a really large quantity of leaves at once, resulting in the fishes gasping at the surface- a sign of...oxygen depletion?

Makes sense, right?

These are interesting clues about the process of decomposition of leaves when they enter into our aquatic ecosystems. They have implications for our use of botanicals and the way we manage our aquariums. I think that the simple fact that pH and oxygen tend to go down quickly when leaves are initially submerged in pure water during lab tests gives us an idea as to what to expect.

A lot of the initial environmental changes will happen rather rapidly, and then stabilize over time. Which of course, leads me to conclude that the development of sufficient populations of organisms to process the incoming botanical load is a critical part of the establishment of our botanical-method aquariums.

Fungal populations are as important in the process of breaking down leaves and botanical materials in water as are higher organisms, like insects and crustaceans, which function as "shredders." The “shredders” – the animals which feed upon the materials that fall into the streams, process this stuff into what scientists call “fine particulate organic matter.”

And that's where fungi and other microorganisms make use of the leaves and materials, processing them into fine sediments. Allochthonous material can also include dissolved organic matter (DOM) carried into streams and re-distributed by water movement.

And the process happens surprisingly quickly.

In studies carried out in tropical rainforests in Venezuela, decomposition rates were really fast, with 50% of leaf mass lost in less than 10 days! Interesting, but is it tremendously surprising to us as botanical-method aquarium enthusiasts? I mean, we see leaves begin to soften and break down in a matter of a couple of weeks- with complete breakdown happening typically in a month or so for many leaves.

And biofilms, fungi, and algae are still found in our aquariums in significant quantities throughout the process.

So, what's this all mean? What are the implications for aquariums?

I think it means that we need to continue to foster the biological diversity of animals in our aquariums- embracing life at all levels- from bacteria to fungi to crustaceans to worms, and ultimately, our fishes...All forming the basis of a closed ecosystem, and perhaps a "food web" of sorts for our little aquatic microcosms. It's a very interesting concept- a fascinating field for research for aquarists, and we all have the opportunity to participate in this on a most intimate level by simply observing what's happening in our aquariums every day!

We've talked about this very topic many times right here over the years, haven't we? I can't let it go.

Bioversity is interesting enough, but when you factor in seasonal changes and cycles, it becomes an almost "foundational" component for a new way of running our botanical-style aquariums.

Consider this:

The wet season in The Amazon runs from November to June. And it rains almost every day.

And what's really interesting is that the surrounding Amazon rain forest is estimated by some scientists to create as much as 50% of its own precipitation! It does this via the humidity present in the forest itself, from the water vapor present on plant leaves- which contributes to the formation of rain clouds.

Yeah, trees in the Amazon release enough moisture through photosynthesis to create low-level clouds and literally generate rain, according to a recent study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (U.S.)!

That's crazy.

But it makes a lot of sense, right?

Okay, that's a cool "cocktail party sound bite" and all, but what happens to the (aquatic) environment in which our fishes live in when it rains?

Well, for one thing, rain performs the dual function of diluting organics, while transporting more nutrient and materials across the ecosystem. What happens in many of the regions of Amazonia - and likewise, in many tropical locales worldwide-is the evolution of some of our most compelling environmental niches...

We've literally scratched the surface, and the opportunity to apply what we know about the climates and seasonal changes which occur where our fishes originate, and to incorporate, on a broader scale, the practices which our Corydoras-enthusiast friends employ on all sorts of fishes!

So much to learn, experiment with, and execute on.

Stay fascinated. Stay intrigued. Stay observant. Stay creative. Stay astute...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Behind the dynamics of the "Urban Igapo"

I've always been fascinated by environments which transform from dry, terrestrial ones to lush aquatic ones during the course of the year. I remember as a kid visiting a little depression in a field near my home , which, every spring, with the rains would turn into a little pond, complete with frogs, Fairy Shrimp, and other life forms. I used to love exploring it, and was utterly transfixed by the unique and dynamic seasonal transition.

The thrill and fascination of seeing that little depression in the ground, which I later learned was called a "vernal" or "temporal" pool by ecologists, never quite left me. As a fish geek, I knew that one day I'd be able to incorporate what I had seen into my fish keeping hobby...somehow.

About 5 years ago, I got a real "bug up my ass", as they say, about the flooded forests of South America. There is something alluring to me about the way these habitats transition between terrestrial and aquatic at certain times of the year. The migration of fishes and the emergence of aquatic life forms in a formerly terrestrial environment fascinates me- as does the tenacity of the terrestrial organisms which hang on during these periods of inundation.

So, I began playing with aquariums configured to replicate the function and form of these unique habitats. I spent a lot of time studying the components of the Igapo and Varzea environments- the soils, plants, fauna, etc., and learning the influences which lead to their creation and function.

Once I had a grasp of the way these dynamic ecologies work, the task of attempting to recreate them in the aquarium became more realistic and achievable. I realized that, although hobbyists have created what they call "Igapo" simulations in biotope contests for years, for example, it was always a representation of the "wet" season. Essentially a living "diorama" of sorts. Not really a true simulation of the seasonal dynamics which create these habitats.

They were cool, but something was somehow missing to me. With those representations, you throw in some leaves, twigs, and seed pods, maybe a few plants, and call your tank a "flooded forest." I mean, essentially a botanical-style aquairum, although the emphasis was on appearance, not function. That wasn't really that difficult to do, nor much of a advancement in the current state of the art of aquarium keeping. I could do that already. Rather, I wanted to recreate the process- all of it- or as much as possible- in my aquariums.

Thus, the idea of the "Urban Igapo"- a functional representation of a transitional aquatic habitat was born.

The concept behind the "Urban Igapo" is pretty straightforward:

The idea is to replicate to a certain extent, the seasonal inundation of the forests and grasslands of of Amazonia by starting the tank in a 'terrestrial phase", then slowly inundating it with water over a period of weeks or more; then, running the system in an "aquatic phase" for the duration of the 'wet season", then repeating the process again and again.

Because you can do this in the comfort of your own home, we called the concept the "Urban Igapo." About 2 years ago, we went more in depth with some of the procedures and techniques that you'd want to incorporate into your own executions of the idea.

As with so many things in the modern aquarium hobby, there is occasionally some confusion and even misunderstandings about why the hell we do this in the first place!

Well, that's a good question! I mean, the whole idea of this particular approach is to replicate as faithfully as possible the seasonal wet/dry cycles which occur in these habitats. It starts with a dry or terrestrial environment, managed as such for an extended period of time, which is gradually flooded to simulate inundation which occurs when the rainy season commences and swollen rivers and streams overflow into the forest or grassland.

Sure, you can replicate the "wet season" only- absolutely. I've seen tons of tanks created by hobbyists to do this. However, if you want to replicate the seasonal cycle- the real magic of this approach- you'll find as I did that it's more fun to do the "dry season!"

Think of it in the context of what the aquatic environment is- a forest floor or grassland which has been flooded. If you develop the "hardscape" (gulp) for your tank with that it mind, it starts making more sense. What do you find on a forest floor or grassland habitat? Soil, leaf litter, twigs, seed pods, branches, grasses, and plants.

Just add water, right?

Well, sort of.

Now, recently, one of my friends who was presenting his experiences with this approach was just getting pounded on a forum by some, well- let's nicely call them "skeptics"- you know, the typical internet-brave "armchair expert" types- about why you'd do this and how it can't lead to a stable aquarium and how it's "not a blackwater aquarium" (okay, it wasn't presented as such, but it could be...) and that it's just a "dry start" (Well, sort of, but you have to understand the concept behind it, dude), and that you don't need to do it this way and...well- that kind of stuff.

I mean, the full compliment of negative, ignorant, questions by people clearly frightened about someone trying to do something a little differently. In a typical display of online-warrior hypocrisy, one particularly nasty hack did not even bother to research the idea or think about what it was really trying to do before laying into my friend.

Apparently, for these people, there was a lot to unpack.

I mean, first of all, the idea was not intended to be a "dry start" planted tank. It just wasn't. I mean, it starts out "dry", but that's where the similarity ends. This ignorant comment is a classic example of the way some hobbyists make assumptions based on a superficial understanding of something.

We aren't trying to grow aquatic plants here. It's about creating a habitat of terrestrial plants snd grasses, allowing them to establish, snd then inundating the display. Most of the terrestrial grasses will simply not survive extended periods of time submerged. Now, you COULD add adaptable aquatic plants- there are no "rules"- but the intention was to replicate a seasonal dynamic.

The other point, which is utterly lost on some people, is that establishing a "transitional" environment in an aquarium takes time and patience. One dummy literally called the process "complete nonsense" and a "waste of time." This is exactly the kind of self-righteous, ignorant hobbyist who will never get it. In fact, I'm surprised guys like that actually have any success at anything in the hobby.

Such a dismissive and judgmental attitude.

The wet season in The Amazon runs from November to June. And it rains almost every day. And what's really interesting is that the surrounding Amazon rain forest is estimated by some scientists to create as much as 50% of its own precipitation! Think about THAT for a minute. It does this via the humidity present in the forest itself, from the water vapor present on plant leaves- which contributes to the formation of rain clouds.

Yeah, trees in the Amazon release enough moisture through photosynthesis to create low-level clouds and literally generate rain, according to a recent study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (U.S.)!

That's crazy.

But it makes a lot of sense, right?

Yet another reason why we need to protect these precious habitats. You cut down a tree in the Amazon- you're literally reducing the amount of rain that can be produced.

It's that simple.

That's really important. It's more than just a cool "cocktail party sound bite."

So what happens to the (aquatic) environment in which our fishes live in when it rains? What does the rain actually do?

Well, for one thing, rain performs the dual function of diluting organics, while transporting more nutrient and materials across the ecosystem. What happens in many of the regions of Amazonia, for example- is the evolution of our most compelling environmental niches. The water levels in the rivers rise significantly. often several meters, and the once dry forest floor fills with water from the torrential rain and overflowing rivers and streams.

The Igapos are formed.

Flooded forest floors.

The formerly terrestrial environment is now transformed into an earthy, twisted, incredibly rich aquatic habitat, which fishes have evolved over eons to live in and utilize for food, protection, and spawning areas.

All of the botanical material-shrubs, grasses, fallen leaves, branches, seed pods, and such, is suddenly submerged; often, currents re-distribute the leaves and seed pods and branches into little pockets and "stands", affecting the (now underwater) "topography" of the landscape.

Leaves begin to accumulate.

Soils dissolve their chemical constituents- tannins, and humic acids- into the water, enriching it. Fungi and micororganisms begin to feed on and break down the materials. Biofilms form, crustaceans multiply rapidly. Fishes are able to find new food sources; new hiding places..new areas to spawn.

Life flourishes.

So, yeah, the rains have a huge impact on tropical aquatic ecosystems. And it's important to think of the relationship between the terrestrial habitat and the aquatic one when visualizing the possibilities of replicating nature in your aquarium in this context.

It's an intimate, interrelated, "codependent" sort of arrangement!

To replicate this process is really not difficult. The challenging part is to separate what we are trying to do here from our preconceptions about how an aquarium should work. To understand that the resulting aquatic display won't initially look or function like anything that we're already familiar with.

While it superficially resembles the "dry start" method that many aquatic plant enthusiasts play with, it's important to remember that our goal isn't to start plants for a traditional aquarium. It's to establish terrestrial growth and to facilitate a microbiome of organisms which help create this habitat. It's to replicate, on some levels, the year-round dynamic of the Amazonian forests. We favor terrestrial plants- and grasses-grown from seed, to start the "cycle."

So, those of you who are ready to downplay the significance of experimenting with this stuff because "people have done 'dry start' planted tanks for years", take comfort in the fact that I recognize that, and acknowledge that we're taking a slightly different approach here, okay?

You'll need to create a technical means or set of procedures to gradually flood your "rainforest floor" in your tank, which could be accomplished manually, by simply pouring water into the vivarium over a series of days; or automatically, with solenoids controlling valves from a reservoir beneath the setup, or perhaps employing the "rain heads" that frog and herp people use in their systems. This is all very achievable, even for hobbyists like me with limited "DIY" skills.

You just have to innovate, and be willing to do a little busy work. You can keep it incredibly simple, and just utilize a small tank.

You must be patient.

And of course, there are questions. Here are some of the major/common ones we receive about this concept:

Does the grass and plants that you've grown in the "dry season" survive the inundation?

A great question. Some do, some don't. (How's that for concise info!). I've played with grasses which are immersion tolerant, such as Paspalum. This stuff will "hang around" for a while while submerged for about a month and a half to two months, in my experience, before ultimately succumbing. Sometimes it comes back when the "dry season" returns. However, when it doesn't survive, it decomposes in the now aquatic substrate, and adds to the biological diversity by cultivating fungi and bacteria.

You can use many plants which are riparian in nature or capable of growing emmersed, such as my fave, Acorus, as well as all sorts of plants, even aquatics, like Hydrocotyle, Cryptocoryne, and others. These can, of course, survive the transition between aquatic and "terrestrial" environments.

How long does the "dry season" have to last?

Well, if you want to mimic one of these habitats in the most realistic manner possible, follow the exact wet and dry seasons as you'd encounter in the locale you're inspired by. Alternatively, I'd at least go 2 months "dry" to encourage a nice growth of grasses and plants prior to inundation.

And of course, you cans do this over and over again! If you're trying to keep fishes like annual killifishes, the "dry season" could be used on the incubation period of their eggs.

When you flood the tank, doesn't it make a cloudy mess? Does the water quality decline rapidly?

Sure, when you add water to what is essentially a terrestrial "planter box", you're going to get cloudiness, from the sediments and other materials present in the substrate. You will have clumps of grasses or other botanical materials likely floating around for a while.

Surprisingly, in my experience, the water quality stays remarkably good for aquatic life. Now, I'm not saying that it's all pristine and crystal clear; however, if you let things settle out a bit before adding fishes, the water clears up and a surprising amount of life (various microorganisms like Paramecium, bacteria, etc.) emerges.

Curiously, I personally have NOT recorded ammonia or nitrite spikes following the inundation. That being said, you can and should test your water before adding fishes. You can also dose bacterial inoculants, like our own "Culture" or others, into the water to help. The Purple Non-Sulphur bacteria in "Culture" are extremophiles, particularly well adapted to the dynamics of the wet/dry environment.

Should I use a filter in the "wet season?"

You certainly can. I've gone both ways, using a small internal filter or sponge filter in some instances. I've also played with simply using an air stone. Most of the time, I don't use any filtration. I just conduct partial water exchanges like I would with any other tank- although I take care not to disturb the substrate too much if I can. When I scaled up my "Urban Igapo" experiments to larger tanks (greater than 10 gallons), Il incorporated a filters with no issues.

A lot of what we do is simply letting Nature "take Her course."

Ceding a lot of the control to Nature is hard for some to quantify as a "technique" or "method", so I get it. At various phases in the process, our "best practice" might be to simply observe...

And with plant growth slowing down, or even going completely dormant while submerged, the utilization of nutrients via their growth diminishes, and aquatic life forms (biofilms, algae, aquatic plants, and various bacteria, microorganisms, and microcrustaceans) take over. There is obviously an initial "lag time" when this transitional phase occurs- a time when there is the greatest opportunity for one life form or another (algae, bacterial biofilms, etc.) to become the dominant "player" in the microcosm.

It's exactly what happens in Nature during this period, right?

And there are parallels in the management of aquariums.

In our aquarium practice, it's the time when you think about the impact of technique-such as water exchanges, addition of aquatic plants, adding fishes, reducing light intensity and photoperiod, etc. and (again) observation to keep things in balance- at least as much as possible. You'll question yourself...and wonder if you should intervene- and how..

It's about a number of measured moves, any of which could have significant impact- even "take over" the system- if allowed to do so. This is part of the reason why we don't currently recommend playing with the Urban Igapo idea on a large-tank scale just yet. (that, and the fact that we're not going to be geared up to produce thousands of pounds of the various substrates just yet! 😆)

Until you make those mental shifts to accept all of this stuff in one of these small tanks, the idea of replicating this in 40-50, or 100 gallons is something that you may want to hold off on for just a bit.

Or not.

I mean, if you understand and accept the processes, functions, and aesthetics of this stuff, maybe you wouldwant to "go big" on your first attempt. However, I think you need to try it on a "nano scale" first, to really "acclimate" to the idea.

The idea of accepting Nature as it is makes you extremely humble, because there is a realization at some point that you're more of an "interested observer" than an "active participant." It's a dance. One which we may only have so much control- or even understanding of! That's part of the charm, IMHO.

These habitats are a remarkable "mix" of terrestrial and aquatic elements, processes, and cycles. There is a lot going on. It's not just, "Okay, the water is here- now it's a stream!"

Nope. There is a lot of stuff to consider.

In fact, one of the arguments one could make about these "Urban Igapo" systems is that you may not want to aggressively intervene during the transition, because there is so much going on! Rather, you may simply want toobserve and study the processes and results which occur during this phase. Personally, I've noticed that the "wet season" changes in my UI tanks generally happen slowly, but you will definitely notice them as they occur.

After you've run through two or three complete "seasonal transition cycles" in your "Urban Igapo", you'll either hate the shit out of the idea- or you'll fall completely in love with it, and want to do more and more work in this alluring little sub-sector of the botanical-style aquarium world.

The opportunity to learn more about the unique nuances which occur during the transition from a terrestrial to an aquatic habitat is irresistible to me. Of course, I'm willing to accept all of the stuff with a very open mind. Typically, it results in a fascinating, utterly beautiful, and surprisingly realistic representation of what happens in Nature.