- Continue Shopping

- Your Cart is Empty

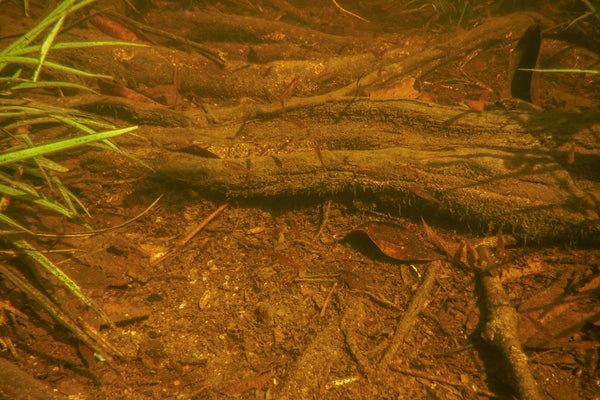

Keeping it together: The beauty of "buttress roots" and their function in the flooded forests...

There is something incredibly compelling about the way terrestrial trees and shrubs interact with the aquatic environment. This is a surprisingly dynamic, highly inter-dependent relationship which has rarely been discussed in aquarium circles.

Let's have that talk!

We have talked a lot about roots before...They are structures which are so important in so many ways to these ecosystems, in both their terrestrial and aquatic phases.

Not only do they help "secure the soils" from falling away, they foster epiphytic algae, fungal growth, and biofilms, which supplement the foods of the resident fishes. And of course, they provide a physical habitat for fishes to forage, seek shelter, and reproduce among. In short, these roots create a unique "microhabitat" which harbors a diversity of life.

And they look pretty aesthetically cool, too!

So yeah- this makes them an irresistible subject for a natural-looking- and functioning- aquascape!. And relatively easy to execute, too!

With a variety of interesting natural materials readily available to us as hobbyists, it's easier than ever to recreate these habitats in as detailed a version as you care to do.

As usual with my ramblings, this blog has become yet another homage to roots and other forest features, and how they function in the transitional aquatic habitats we love so much.

One of the foundational root types that we can replicate in or aquarium works what botanists call "buttress roots." Not only are these interesting structures to replicate in our aquariums, they are an important component of the ecosystems which make up the flooded forests, particularly in areas like Amazonia.

Buttress roots are large, very wide roots that help keep shallow-rooted forest trees from toppling over. They are commonly associated with nutrient-poor soils (you know, like the kinds you see in the igapo or varzea ecosytems). These roots also serve to take uptake nutrients are available in these podzolic soils.

The buttress roots of various species of forest trees often weave in and out of each other horizontally, and create a vast network which serves to keep many trees in the forest from toppling over. And since these habitats often flood during the rainy season, buttress roots help stabilize the trees and retain soils during this inundation.

Isn't that interesting? Even the trees have made adaptations over eons which allow them to survive under these harsh conditions! As you might suspect, the "white-water" flooded forests (Varzea) tend to be richer in species diversity and density than the less nutrient-dense blackwater-flooded Igapo forests. Seems like everything in these ecosystems is a function of nutrient availability, isn't it?

And the sandy soil which comprises these habitats is low in nutrients, such as phosphorus, potassium, calcium, and magnesium. Ecologists will tell you that the soil also has a "high infection rate", or density, of fungi, and consists of a lot of fine roots in the upper layer of the soil.

The network of fine roots helps these forests uptake nutrients in these nutrient- poor conditions. And even more interesting, studies have shown that decomposition of materials can take several years in the deep litter layer on the forest floor.

In addition to being nutrient poor, the sandy soil does not retain water very well, which can lead to drought after the inundation period is over. It's another example of the intricate relationship between land and water, and the way terrestrial and aquatic habitats work together.

Because the flood pulses are so predictable, eons of this process has led to adaptations by various forest trees to withstand them, as well as to depend upon various species of fishes ('frugivores") to help disperse seeds throughout the forest by consuming and pooping them out!

Ecologists have further determined that the distribution of various species of trees in these forests may be largely determined by the ability of their seedlings to tolerate periods of submergence and limited light that penetrates the canopy through the water column.

(Cariniana legalis tree. Image by mauroguanandi, used under CC BY 2.0)

In fact, in remarkable adaptation to this environment, seedlings may be completely submerged for several months, and many species can tolerate several weeks of complete submergence in a state of "rest." Most species in these forests tend to grow during the times year when the forests are flooded, and tend to bear fruit and flower when the waters start to recede.

It's all about adaptation to this incredible, highly variable habitat.

We talk a lot about food webs in these habitats and how to replicate some of their attributes in our aquariums. Here's another insight into the food webs of these flooded forest habitats to consider, from a paper I found by researcher Mauricio Camargo Zorro:

"Both algae and aquatic macrophytes enter in aquatic food webs mostly in form of detritus (fine and coarse particulate organic matter) or being transported by water flow and settling onto substrates (Winemiller 2004). Particulate organic matter in the stream of rapids and waterfalls is mostly associated with biofilm and epilithic diatoms that grow on rocks, submerged wood, and herbaceous plants and compose the main energy sources for macro invertebrates and other trophic links (Camargo 2009a)."

A lot there, I know. What this does is give us some ideas about facilitating the "in situ" production of supplementary food sources in our aquariums.

This was what inspired me in a recent home "planted" blackwater aquarium. The interaction between the terrestrial elements and the aquatic ones. Allowing terrestrial leaves to accumulate naturally among the "tree root structure" we have created fosters this more natural-functioning environment.

As these leaves begin to soften and ultimately break down, they foster microbial growth, biofilms, and fungal growths- all of which will provide supplemental foods for the resident fishes...just like what happens in Nature.

Facilitating these processes- allowing the materials to accumulate naturally and break down "in situ" is a key component of replicating and supporting these microhabitats in our aquariums. The typical aquarium hardscape- artistic and beautiful as it might be, generally replicates the most superficial aesthetic aspects of such habitats, and tends to overlook their function- and the reasons why such habitats form.

Replicating forest structures- like buttress roots and their functions- really helps facilitate more natural biological processes, functions, and behaviors in our fishes!

The possibilities are endless here! And, as always, the aesthetics are a "collateral benefit" of the process.

And of course, I think it's a call for us to employ some bigger, thicker pieces of wood in our tanks! Now, sure, I can hear some groans. I mean, big, heavy wood has some disadvantages in an aquarium. First, the damn things are...well- BIG- taking up a lot of physical space, and in our case, precious water volume. And the "scale" is a bit different. And, of course, a big, heavy piece of wood is kind of pricy. And physically cumbersome for some.

However, the use of larger pieces of wood- or several pieces of wood aggregated together- can create really interesting structures which can replicate the form and function of buttress roots in the aquarium.

At the very least, you can try a fairly large piece of aquatic wood (or several smaller pieces, aggregated to form one large piece) some time. I think you might find this sort of arrangement quite fascinating to play with!

Arrange the wood in such a way as to break up the tank space and give the impression that it simply rooted naturally. Let it create barriers for fishes to swim into, and disrupt water flow patterns. Allow it to "cultivate" fungal growth and biofilms on its surfaces, and small pockets where leaves, botanicals, substrate materials, and...detritus can collect.

This is exactly what happens in Nature.

It's fascinating and important for us to understand- at least on a superficial level- the concept of replicating some of the structures and features of these transitional habitats, such as flooded forest floors.

By understanding how these structures work, why the exist, and how they provide a benefit to the organisms which live among them, we will be in an excellent position to incorporate exciting features- such as buttress roots-into our future aquariums!

Stay inspired. Stay educated. Stay bold. Stay creative. Stay thoughtful...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Scott Fellman

Author