- Continue Shopping

- Your Cart is Empty

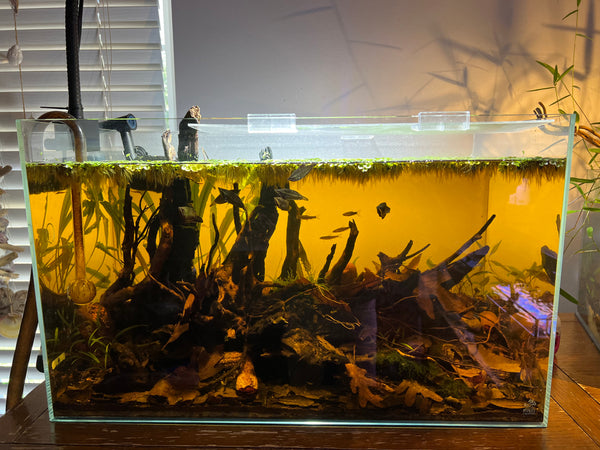

This is how I do it.. (pt.3)- Establishing a botanical method aquairum

Last year, I shared the first two installments of what I hope to be an evolving, semi-periodic look at the techniques I employ personally with my botanical method aquariums. I mean, we share all of that stuff now in our social media and blogs, but until this little "series" I've never been done it in a really concise manner. Many of you have asked for this type of piece in "The Tint", and, since Ive been creating some new tanks lately, it's time to get back at it!

Today, let's get back to a pretty fundamental look at what I do, and how I start my botanical method aquariums.The processes and practices, in particular. Remember, this is not the "ultimate guide" about how do to all of this stuff...It's a review of what I do with my tanks. It's not just a strict "how to", of course. It's more than that. A look at what goes through my mind. My philosophy, and the principles which guide my work with my aquariums. I hope you find it helpful.

First off, one of the main things that I do- what I believe most aquarists do- is to have a "theme"- an idea- in mind when I start my tanks. A "North Star", if you will. This is an essential thing; having a "track to run on" guides the entire project. It influences your material and equipment selections, your establishment timetables, and of course, your fish population.

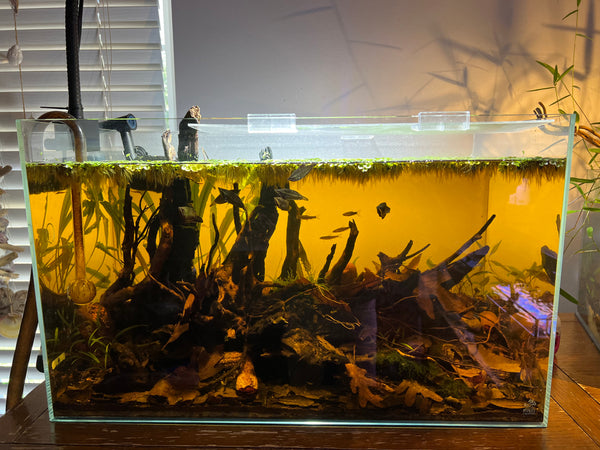

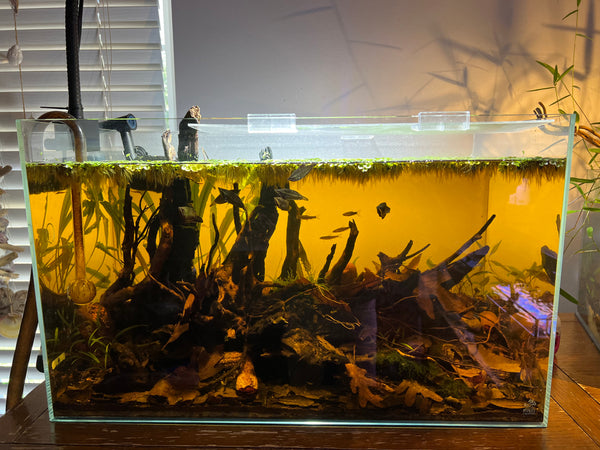

Let's look at my most recent botanical method aquarium as an example of my approach.

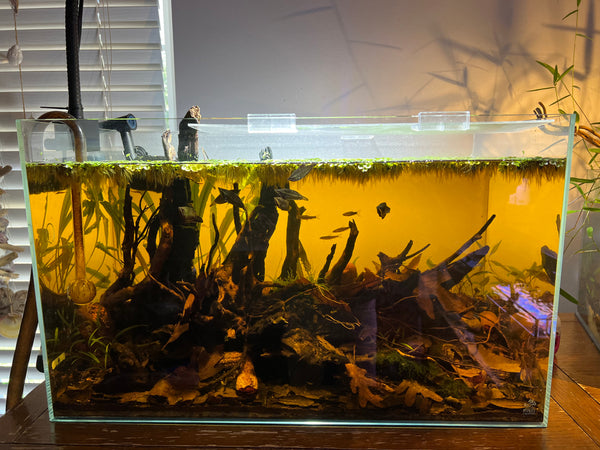

First off, I had a pretty good idea of the "theme" to begin with: A "wet season" flooded Amazonian forest. Now, I freely admit that I put a lot of thought into getting the characteristics of the environment and ecology down as functionally realistic as possible, but that the fish selection was far more "cosmopolitan"- consisting of characins- my fave fishes- some of which are found in such habitats, and some which are not. It was not intended to be some competition-minded, highly accurate biotope display.

Just a fun way to feature some of my fave fishes!

Since I was kid, I'd always dreamed of a medium-to-large-sized tank, filled with a large number of different Tetras. This tank would essentially be my "grown-up", more evolved version of my childhood "Tetra fantasy tank!"

The most basic of all "how I do it" lessons is to have some idea about what you're trying to accomplish before you start. In our game, since recreating the environment and ecology are paramount, this will impact every other decision you make.

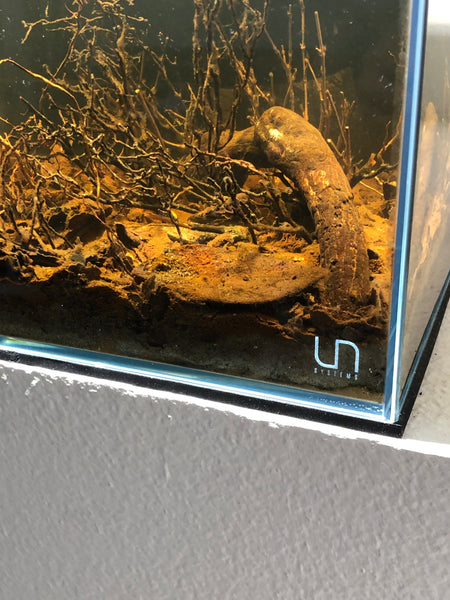

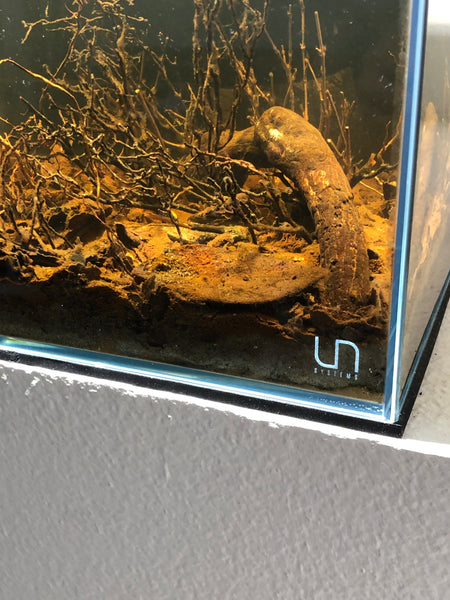

In this aquarium, the main "structure" of the ecosystem is comprised of a literal "hodgepodge" of "scrap" pieces of wood of different types and sizes that I had laying around. Very little thought was given to specific types or shapes. The idea was to create a representation of an inverted root section and tangle of broken branches from a fallen tree on the forest floor, which becomes an underwater feature during the "wet season."

It was simply a matter of assembling a bunch of smaller pieces to create the look of the inverted root that I had in my head. And once they are down and covered in that "patina" of biocover, it's hard to distinguish one from the other. It looks like one piece, really. Sure, it would have been easier to carefully select just one piece to do it all (would it, though?🤔), but it was more practical to "use what I had" and make it work!

So, another "how I do it" lesson is that you don't always have to incorporate a single specific wood type to have an incredible-looking, interesting physical aquascape. No chasing after the latest and creates trendy wood for me.

I use what I have, or what I like.

You should, too.

Since we're more about function than we are about aesthetics exclusively, which type of wood isn't as important as simply having any wood to complete the job. (and by extension, other "aquascaping materials"...)

After I get my wood pieces the way I like them, it's the usual stuff: Make sure that they stay down before you fill the tank all the way, etc. Nothing exotic here.

The next step is to fill the tank up. Again, there is no real magic here, except to note that, since we're often using sedimented substrate and bits of botanicals on the substrate, it's best to do this very slowly. I mean, your water is likely to be turbid for some time; it's what goes with the territory. However, no need to exacerbate it by rushing!

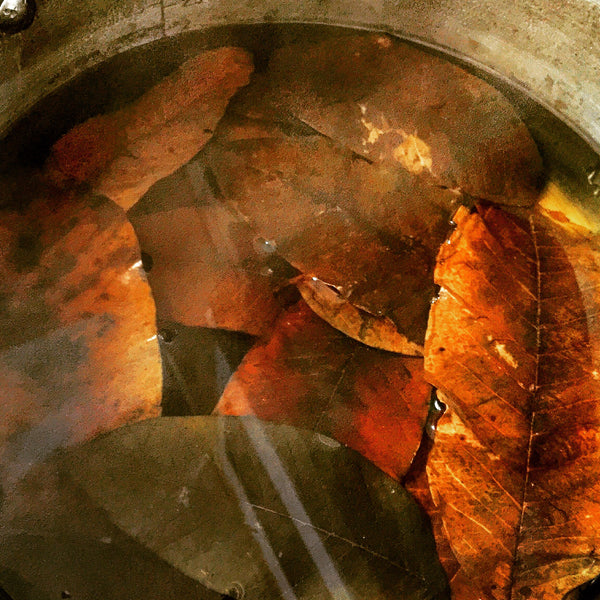

And, after the tank is about 1/3 full, I'll usually add all of my prepared leaves and botanicals. Why? Because I've found over the years, similar to planted tank enthusiasts, that it's much easier to get the leave and botanicals where you want them by working in a partially filled tank.

Another, hardly revolutionary approach, but one which I think makes perfect sense for what we do.

After the tank is fully filled...that's is where the real fun begins, of course...In our world, the "fun" includes a whole lot of watching and waiting...Waiting for the water to clear up (if you use sedimented substrates). Waiting for Nature to start Her work; to act upon the terrestrial materials that we have added to our tank.

And of course, this is the time when you're busy making sure that you did all of the right things to get the tank ready for "first water."

And of course, it's also the part where every hobbyist, experienced or otherwise, has those lingering doubts; asks questions- goes through the "mental gymnastics" to try to cope: "Do I have enough flow?" "Was my source water quality any good?" "Is it my light?"

And then- when the first fungal filaments or biofilms appear, some new to our specialty still doubt: "When does this shit go away?" "It DOES go away. I know it's just a phase." Right? "Yeah, it goes away..." "When?" "It WILL go away. Right?"

And then there is the realization that this is a BOTANICAL METHOD aquairum, and that you expect and WANT that stuff in your tank. And it will likely never fully "go away..."

But you know this. And yet, you still count a bit.

I mean, it's common with every new tank, really. The doubts. The worries....

The waiting. The not-being-able-to-visualize-a-fully-stocked tank "thing"...Patience-testing stuff. Stuff which I- "Mr. Tinted-water-biofilms-and-decomposing-leaves-and-botanicals-guy"- am pretty much hardened to by now. You will be, too. It's about graciously accepting a totally different "look." Not worrying about "phases" or the ephemeral nature of some things in my aquarium.

Yet, like anyone who sets up an aquarium, I admit that I still occasionally get those little doubts in the dim (tinted?) recesses of my mind now and then- the product of decades of doing fish stuff, yet wondering if THIS is the one time when things WON'T work out as expected...

I mean, it's one of those rights of passage that we all go through when we set up aquariums right? The early doubts. The questioning of ourselves. The reviewing of fundamental procedure and practice. Maybe, the need to reach out to the community to gain reassurance.

It's normal. It's often inevitable.

Do I worry about stuff?

Well, yeah. Of course.

However, it's not at the point in my tank's existence when you'd think that I'd worry. It's a bit later. And it's not about the stuff you might think. It's all about the least "natural" part of my aquariums: The equipment.

Yep.

Usually, for me, this worry manifests itself right around the first water exchange. By that time, you'll likely have learned a lot of the quirks and eccentricities of your new aquarium as it runs. You'll have seen how it functions in daily operation.

And then you do your first deliberate "intervention" in its function. You shut down the pumps for a water exchange.

That's when I clutch. I worry.

I always get a lump in my throat the first time I shut off the main system pump for maintenance. "Will it start right back up? Did I miscalculate the 'drain-down' capacity of the sump? Will this pump lose siphon?"

And so what the fuck if it DOES? You simply...fix the problem. That's what fish geeks do. Chill.

Namaste.

Yet, I worry.

That's literally my biggest personal worry with a new tank, crazy though it might sound. The reality, is that in decades of aquarium-keeping, I've NEVER had a pump not start right back up, or overflowed a sump after shutting down the pump...but I still watch, and worry...and don't feel good until that fateful moment after the first water change when I fire up the pump again, to the reassuring whir of the motor and the lovely gurgle of water once again circulating through my tank.

Okay, perhaps I'm a bit weird, but I'm being totally honest here- and I'm not entirely convinced that I'm the only one who has some of these hangups when dealing with a new tank! I've seen a lot of crazy hobbyists who go into a near depression when something goes wrong with their tanks, so this sort of behavior is really not that unusual, right?

However, our typical "worries" are less "worries" than they are little realizations about how stuff works in these tanks.

In a botanical method aquarium, you need to think more "holistically." You need to realize that these extremely early days are the beginning of an evolution- the start of a living microcosm, which will embrace a variety of natural processes.

But yeah, we know what to expect...We observe.

So, what exactly happens in the earliest days of a botanical method aquarium?

Well, for one thing, the water will gradually start to tint up...

Now, I admit that this is perhaps one of the most variable and unpredictable aesthetic aspects of these types of aquariums- yet one which draws in a lot of new hobbyists to our "tribe." The allure of the tinted water. Many factors, ranging from what kind (and how much) chemical filtration media you use, what types (and how much again!) of botanical materials you're using, and others, impact this. Recently, I've heard a lot of pretty good observation-based information from experienced plant enthusiasts that some plants take up tannins as they grow. Interesting, huh?

Stuff changes. The botanicals themselves begin to physically break down; the speed and the degree to which this happens depends almost entirely on processes and factors largely beyond your control, such as the ability of your microbial population to "process" the materials within your aquarium.

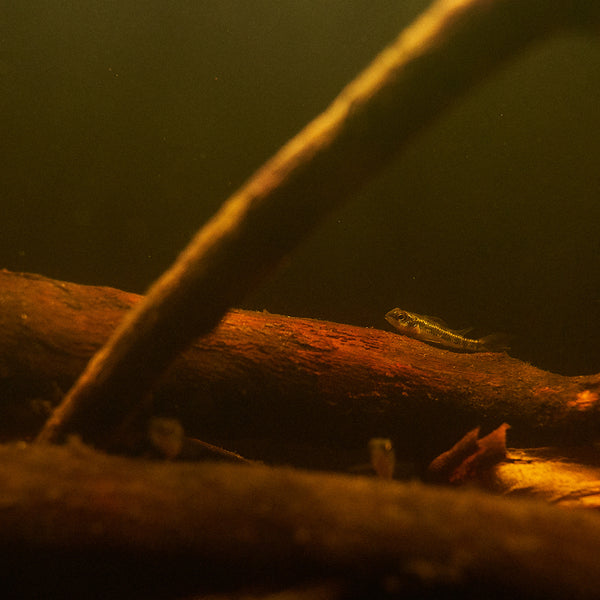

I personally feel that botanical-method aquariums always look better after a few weeks, or even months of operation. When they're new, and the leaves and botanicals are crisp, intact, and fresh-looking, it may have a nice "artistic" appearance- but not necessarily "natural" in the sense that it doesn't look established and alive.

The real magic takes place weeks later.

Things change a bit...

The pristine seed pods and leaves start "softening" a bit. And biofilms and fungal growths make their first appearances.

Mental shifts are required on your part.

Yup, the first mental shift that we have to make as lovers of truly natural style aquariums is an understanding that these tanks will not maintain the crisp, pristine look without significant intervention on our part. And, by "intervention", I mean scrubbing, rinsing, and replacing the leaves and botanicals as needed. I mean, sure- you can do that. I know a bunch of people who do.

They absolutely love super pristine-looking tanks.

Well, to each his own, I suppose. Yet, the whole point of a true botanical method aquarium is to accept the "less than pristine" look and the changes that occur within the system because of natural processes and functions.

I admit, I feel a bit sorry for people who can't make the mental shift to accept the fact that Nature does Her own thing, and that She'll lay down a "patina" on our botanicals, gradually transforming them into something a bit different than when we started.

When we don't accept this process, we sadly get to miss out on Nature guiding our tank towards its ultimate beauty- perhaps better than we even envisioned.

For some, it's really hard to accept this process. To let go of everything they've known before in the hobby. To wait while Nature goes through her growing pains, decomposing, transforming and yeah- evolving our aquascapes from carefully-planned art installations to living, breathing, functioning microcosms.

But, what about all of that decay? That "patina" of biofilm?

If you're struggling with accepting this, just remind yourself regularly that it's okay.

It's normal.

The whole environment of a more established botanical-method aquarium looks substantially different after a few weeks. While the water gradually darkens, those biofilms appear...it just looks more "earthy", mysterious, and alive.

It's a reminder of "Wabi-Sabi" again.

Something that's been on my mind a lot lately.

In it's most simplistic and literal form,the Japanese philosophy of "Wabi Sabi" is an acceptance and contemplation of the imperfection, constant flux and impermanence of all things.

This is a very interesting philosophy, one which was brought to our attention in the aquarium world by none other than the late, great, Takashi Amano, who proferred that a (planted) aquarium is in constant flux; constant transistion- and that one needs to contemplate, embrace, and enjoy the changes, and to relate them to the sweet sadness of the transience of life.

Many of Amano's greatest works embraced this philosophy, and evolved over time as various plants would alternately thrive, spread and decline, re-working and reconfiguring the aquascape with minimal human intervention. Each phase of the aquascape's existence brought new beauty and joy to those would observe them.

Yet, in today's contest-scape driven, break-down-the-tank-after-the-show world, this philosophy of appreciating change by Nature over time seems to have been tossed aside as we move on to the next one.

Sure, this may fit our human lifestyle and interest, but it denies Nature her chance to shine, IMHO. There is something amazing about this process of change; about the way our tanks evolve, and we should enjoy them at every stage.

And then, there is the human desire to "edit" stuff. People ask me all the time if I take stuff out of the system; if I make "edits" and changes to the tank as it breaks in, or as the botanicals start to decompose.

Well, I don't, for reasons we've discussed a lot around here:

Remember, one thing that's unique about the botanical-method approach is that we accept the idea of a microbiome of organisms "working" our botanical materials. We're used to decomposing materials accumulating in our systems. We understand that they act, to a certain extent, as "fuel" for the micro and macrofauna which reside in the aquarium.

I have long been one the belief that if you decide to let the botanicals remain in your aquarium to break down and decompose completely, that you shouldn't change course by suddenly removing the material all at once...

Why?

Well, I think my theory is steeped in the mindset that you've created a little ecosystem, and if you start removing a significant source of someone's food (or for that matter, their home!), there is bound to be a net loss of biota...and this could lead to a disruption of the very biological processes that we aim to foster.

Okay, it's a theory...

But I think it's a good one.

You need to look at the botanical-method aquarium (like any aquarium, of course) as a little "microcosm", with processes and life forms dependent upon each other for food, shelter, and other aspects of their existence. And I really believe that the environment of this type of aquarium, because it relies on botanical materials (leaves, seed pods, etc.), is more signficantly influenced by the amounts and composition of said material.

Just like in natural aquatic ecosystems...

The botanical materials are a real "base" for the little microcosm we create.

And of course, by virtue of the fact that they contain other compounds, like tannins, humic substances, lignin, etc., they also serve to influence the water chemistry of the aquarium, the extent to which is dictated by a number of other things, including the "starting point" of the source water used to fill the tank.

So, in summary- I think the presence of botanicals in our aquariums is multi-faceted, highly influential, and of extreme import for the stability, ecological balance, and efficiency of the tank. As a new system establishes itself, the biological processes adapt to the quantity and types of materials present- the nitrogen cycle and other nutrient-processing capabilities evolve over time as well.

Yes, establishing a botanical method aquarium is as much about making mental shifts and acquiring patience and humility as it is about applying any particular aquarium keeping skills. It's about growing as a hobbyist.

Having faith in yourself, your judgment, and, most important- in the role that Nature Herself plays in our tanks.

In seemingly no time at all, you're looking at a more "broken-in" system that doesn't seem so "clean", and has that wonderful pleasant, earthy smell- and you realize right then that your system is healthy, biologically stable, and functioning as Nature would intend it to. If you don't intervene, or interfere- your system will continue to evolve on a beautiful, natural path.

It's that moment- and the many similar moments that will come later, which makes you remember exactly why you got into the aquarium hobby in the first place: That awesome sense of wonder, awe, excitement, frustration, exasperation, realization, and ultimately, triumph, which are all part of the journey- the personal, deeply emotional journey- towards a successful aquarium- that only a real aquarist understands.

This is how I do it.

Stay excited. Stay bold. Stay observant. Stay brave. Stay curious. Stay patient...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Race to the bottom...

.

Substrates, IMHO, are one of the most often-overlooked components of the aquarium. We tend to just add a bag of "_____________" to our tanks and move on to the "more exciting" stuff like rocks and "designer" wood. It's true! Other than planted aquarium enthusiasts, the vast majority of hobbyists seem to have little more than a passing interest in creating and managing a specialized substrate or associated ecology.

And, when we observe natural aquatic ecosystems, I think we as a whole tend to pay scant little attention to the composition of the materials which form the substrate; how they aggregate, and what occurs when they do.

I'm obsessed with the idea of "functionally aesthetic" substrates in our botanical-style aquariums.

It's because I imagine the substrate as this magical place which fuels all sorts of processes within our aquariums, and that Nature tends to it in the most effective and judicious manner.

Yeah, I'm a bit of a "substrate romantic", I suppose.😆

I think a lot of this comes from my long experience with reef aquariums, and the so-called "deep sand beds" that were quite popular in the early 2000's.

A deep sand bed is (just like it sounds) a layer of fine sand on the bottom of the aquarium, intended to grow bacteria in the deepest layers, which convert nitrate or nitrite to nitrogen gas. This process is generically called "denitrification", and it's one of the benefits of having an undisturbed layer of substrate on the bottom of the aquarium.

Fine sand and sediment is a perfect "media" upon which to culture these bacteria, with its abundant surface area. Now, the deep sand bed also serves as a location within the aquarium to process and export dissolved nutrients, sequester detritus (our old friend), and convert fish poop and uneaten food into a "format" that is usable by many different life forms.

In short, a healthy, undisturbed sandbed is a nutrient processing center, a supplemental food production locale, and a microhabitat for aquatic organisms.

You probably already know most of this stuff, especially if you've kept a reef tank before. And of course, there are reefers who absolutely vilify sandbeds, because they feel that they "compete" with corals, and ultimately can "leach" out the unwanted organics that they sequester, back into the aquarium. I personally disagree with that whole thing, but that's another battle for another time and place!

Okay, saltwater diversion aside, the concept of a deep substrate layer in a botanical-style aquarium continues to fascinate me. I think that the benefits for our systems are analogous to those occurring in reef tanks- and of course, in Nature. In my opinion, an undisturbed deep substrate layer in the botanical-style aquarium, consisting of all sorts of materials, from sand/sediments to leaves to twigs and broken-up pieces of botanicals,can foster all sorts of support functions.

I've always been a fan of in my aquarium keeping work of allowing Nature to take its course in some things, as you know. And this is a philosophy which plays right into my love of dynamic aquarium substrates. If left to their own devices, they function in an efficient, almost predictable manner.

Nature has this "thing" about finding a way to work in all sorts of situations.

And, I have this "thing" about not wanting to mess with stuff once it's up and running smoothly... Like, I will engage in regular maintenance (ie; water exchanges, etc.), but I avoid any heavy "tweaks" as a matter of practice. In particular, I tend not to disturb the substrate in my aquariums. A lot of stuff is going on down there...

Amazing stuff.

I realize, when contemplating really deep aggregations of substrate materials in the aquarium, that we're dealing with closed systems, and the dynamics which affect them are way different than those in Nature, for the most part.

And I realize that experimenting with these unusual approaches to substrates requires not only a sense of adventure, a direction, and some discipline- but a willingness to accept and deal with an entirely different aesthetic than what we know and love. And this also includes pushing into areas and ideas which might make us uncomfortable, not just for the way they look, but for what we are told might be possible risks.

One of the things that many hobbyists ponder when we contemplate creating deep, botanical-heavy substrates, consisting of leaves, sand, and other botanical materials is the buildup of hydrogen sulfide, CO2, and other undesirable compounds within the substrate.

Well, it does make sense that if you have a large amount of decomposing material in an aquarium, that some of these compounds are going to accumulate in heavily-"active" substrates. Now, the big "bogeyman" that we all seem to zero in on in our "sum of all fears" scenarios is hydrogen sulfide, which results from bacterial breakdown of organic matter in the total absence of oxygen.

Let's think about this for just a second.

In a botanical bed with materials placed on the substrate, or loosely mixed into the top layers, will it all "pack down" enough to the point where there is a complete lack of oxygen and we develop a significant amount of this reviled compound in our tanks? I think that we're more likely to see some oxygen in this layer of materials, and I can't help but speculate- and yeah, it IS just speculation- that actual de-nitirifcation (nitrate reduction), which lowers nitrates while producing free nitrogen, might actually be able to occur in a "deep botanical" bed.

There is that curious, nagging "thing" I have in my head about the ability of botanical-influenced substrates to foster denitrification. With the diverse assemblage of microorganisms and a continuous food source of decomposing botanicals "in house", I can't help but think that such "living substrates" create a surprisingly diverse and utilitarian biological support system for our aquariums.

And it's certainly possible to have denitrification without dangerous hydrogen sulfide levels. As long as even very small amounts of oxygen and nitrates can penetrate into the substrate, this will not become an issue for most systems. I have yet to see a botanical-style aquarium where the material has become so "compacted" as to appear to have no circulation whatsoever within the botanical layer.

Now, sure, I'm not a scientist, and I base this on close visual inspection of numerous aquariums, and the basic chemical tests I've run on my systems under a variety of circumstances. As one who has made it a point to keep my botanical-method aquariums in operation for very extended time frames, I think this is significant. The "bad" side effects we're talking about should manifest over these longer time frames...and they just haven't.

And then there's the question of nitrate.

Although not the terror that ammonia and nitrite are known to be, nitrate is much less so. However, as nitrate accumulates, fish will eventually suffer some health issues. Ideally, we strive to keep our nitrate levels no higher than 5-10ppm in our aquariums. As a reef aquarist, I've always been of the "...keep it as close to zero as possible." mindset (that's evolved in recent years, btw), but that is not always the most realistic or achievable target in a heavily-botanical-laden aquarium. You have a bit more "wiggle room", IMHO. Now, when you start creeping towards 50ppm, you're getting closer towards a number that should alert you. It's not a big "stretch" from 50ppm to 75ppm and higher...

And then you get towards the range where health issues could manifest themselves in your fishes. Now, many fishes will not show any symptoms of nitrate poisoning until the nitrate level reaches 100 ppm or more. However, studies have shown that long-term exposure to concentrations of nitrate stresses fishes, making them more susceptible to disease, affecting their growth rates, and inhibiting spawning in many species.

At those really high nitrate levels, fishes will become noticeably lethargic, and may have other health issues that are obvious upon visual inspection, such as open sores or reddish patches on their skin. And then, you'd have those "mysterious deaths" and the sudden death (essentially from shock) of newly-added fishes to the aquarium, because they're not acclimated to the higher nitrate concentrations.

Okay, that's scary stuff. However, high nitrate concentrations are not only manageable- they're something that's completely avoidable in our aquairums.

Quite honestly, even in the most heavily-botanical-laden systems I've played with, I have personally never seen a higher nitrate reading than around 5ppm. I attribute this to common sense stuff: Good quality source water (RO/DI), careful stocking, feeding, good circulation, not disturbing the substrate, and consistent basic aquarium husbandry practices (water changes, filter maintenance, etc.).

Now, that's just me. I'm no scientist, certainly not a chemist, but I have a basic understanding of maintaining a healthy nitrogen cycle in the aquarium. And I am habitual-perhaps even obsessive- about consistent maintenance. Water exchanges are not a "when I get around to it" thing in my aquarium management "playbook"- they're "baked in" to my practice.

And I think that a healthy, ecologically varied substrate is one of the keys to a successful botanical method aquarium.

I'm really into creating substrates that are a reasonable representation of the bottom of streams, tributaries, and igapo, as found in the Amazon basin. Each one of these has some unique characteristics, and each one presents an interesting creative challenge for the intrepid hobbyist. Until quite recently, the most common materials we had to work with when attempting to replicate these substrates were sand, natural and colored gravels, and clay-comprised planted aquarium substrates.

I reiterate a "manifesto" of sorts that I played out in "The Tint" back in 2015:

"If I have something to say about the matter, you'll soon be incorporating a wide variety of other materials into your biotope aquarium substrate!"

Damn, did I just quote myself?

I did!

If you've seen pictures and videos taken underwater in tropical streams (again, I'm pulling heavily from the Amazonian region), you'll note that there is a lot of loose, soil-like material over a harder mud/sand substrate. Obviously, using an entirely soil-based substrate in an aquarium, although technically possible and definitely cool- could result in a yucky mess whenever you disturb the material during routine maintenance and other tasks. You can, however, mix in some of these materials with the more commonly found sand.

So, exactly what "materials" am I referring to here?

Well, let's look at Nature for a second.

Natural streams, lakes, and rivers typically have substrates comprised of materials of multiple "grades", including fine, medium, and coarse materials, such as pebbles, gravels, silty clays and sands. In the aquarium, we seem to have embraced the idea of a homogenous particle size for our substrates for many years. Now, don't get me wrong- it's aesthetically just fine, and works great. However, it's not always the most interesting to look at, nor is it necessarily the most biologically diverse are of the aquarium.

A lot of natural stream bottoms are complimented with aggregations of other materials like leaf litter, branches, roots, and other decomposing plant matter, creating a dynamic, loose-appearing substrate, with lots of potential for biological benefits. Of course, we need to understand the implications of creating such "dynamic" substrates in our closed aquariums.

When we started Tannin, my fascination with the varied substrate materials of tropical ecosystems got me thinking about ways to more accurately replicate those found in flooded forests, streams, and diverse habitats like peat swamps, estuaries, creeks, even puddles- and others which tend to be influenced as much by the surrounding flora (mainly forests and jungles) as it is by geology.

And of course, my obsession with botanical materials to influence and accent the aquarium habitat caused me to look at the use of certain materials for what I generically call "substrate enrichment" - adding materials reminiscent of those found in the wild to augment the more "traditional" sands and other substrates used in aquariums to foster biodiversity and nutrient processing functions.

Again, look to Nature...

If you've seen pictures and videos taken underwater in tropical streams (again, I'm pulling heavily from the Amazonian region), you'll note that there is a lot of loose, soil-like material over a harder mud/sand substrate. Obviously, using an entirely mud-based substrate in an aquarium, although technically possible- will result in a yucky mess whenever you disturb the material during routine maintenance and other tasks. You can, however, mix in some other materials with the more commonly found sand.

That was the whole thinking behind "Substrato Fino" and "Fundo Tropical", two of our most popular substrate "enrichment" materials. They are perfect for helping to more realistically replicate both the look and function of the substrates found in some of these natural habitats. They provide surface area for fungal and microbial growth, and interstitial spaces for smalll crustaceans and other organisms to forage upon.

Substrates aren't just "the bottom of the tank..."

Rather, they are diverse harbors of life, ranging from fungal and biofilm mats, to algae, to epiphytic plants. Decomposing leaves, seed pods, and tree branches compose the substrate for a complex web of life which helps the fishes were so fascinated by flourish. And, if you look at them objectively and carefully, they are beautiful.

I encourage you to study the natural environment, particularly niche habitats or areas of the streams, rivers, and lakes- and draw inspiration from the functionality of these zones. The aesthetic component will come together virtually by itself. And accepting the varied, diverse, not-quite-so-pritinh look of the "real thing" will give you a greater appreciation for the wonders of nature, and unlock new creative possibilities.

In regards to the substrate materials themselves, I'm fascinated by the different types of soils or substrate materials which occur in blackwater systems and their clearwater counterparts, and how they influence the aquatic environment.

For example, as we've discussed numerous times over the years, "blackwater" is not cased by leaves and such- it's created via geological processes.

In general, blackwaters originate from sandy soils. High concentrations of humic acids in the water are thought to occur in drainages with what scientists call "podzol" sandy soils. "Podzol" is a soil classification which describes an infertile acidic soil having an "ashlike" subsurface layer from which minerals have been leached.

That last part is interesting, and helps explain in part the absence of minerals in blackwater. And more than one hobbyist I know has played with the concept of "dirted" planted tanks, using terrestrial soils...hmmm.

Also interesting to note is that fact that soluble humic acids are adsorbed by clay minerals in what are known as"oxisol" soils, resulting in clear waters."Oxisol" soils are often classified as "laterite" soils, which some who grow plants are familiar with, known for their richness in iron and aluminum oxides. I'm no chemist, or even a planted tank geek..but aren't those important elements for aquatic plants?

Yeah.

Interesting.

Let's state it one more time:

We have the terrestrial environment influencing the aquatic environment, and fishes that live in the aquatic environment influencing the terrestrial environment! T

his is really complicated stuff- and interesting! And the idea that terrestrial environments and materials influence aquatic ones- and vice-versa- is compelling and could be an interesting area to contemplate for us hobbyists!

When ecologists study the substrate composition of aquatic habitats like those in The Amazon, they tend to break them down into several categories, broad though they may be: Rock, sand, coarse leaf litter, fine leaf litter, and branches, trunks and roots.

Studies indicate that terrestrial inputs from rainforest streams provide numerous benefits for fishes, providing a wide range of substrate materials that supported a wider range of fishes than can be found in non-forested streams. One study concluded that, "Inputs from forests such as woody debris and leaf litter were found to support a diversity of habitat niches that can provide nursing grounds and refuges against predators (Juen et al. 2016). Substrate size was also larger in forest stream habitats, adding to the complexity and variety of microhabitats that can accommodate a greater and more diverse range of fish species (Zeni et al. 2019)."

But wait- there's more! Rainforests create uniquely diverse aquatic habitats.

"Forests can further diversify and stabilize the types of food available for fish by supplying both allochthonous inputs from leaf litter and increased availability of terrestrial insects that fall directly into the water (Zeni and Casatti). Forest habitats can support a diverse range of trophic guilds including terrestrial insectivores and herbivores (Zeni and Casatti).

Riparian forests deliver leaf litter in streams attracting insects, algae, and biofilm, each of which may be vital for particular fish species (Giam et al., Juen et al. ). In contrast, nonforested streams may lack the allochthonous food inputs that support terrestrial feeding fish species..."

Leaf litter- yet again.

And then there are soils...terrestrial soils- which, to me, are to me the most interesting possible substrates in wild aquatic habitats.

So, the idea of a rich soil substrate that not only accommodates the needs of the plants, but provides a "media" in which beneficial bacteria can grow and multiply is a huge "plus" for our closed aquatic ecosystems. And the concepts of embracing Nature and her processes work really well with the stuff we are playing with.

As you've seen over the past few years, I've been focusing a lot on my long-running "Urban Igapo" idea and experiments, sharing with you my adventures with rich soils, decomposing leaf litter, tinted water, immersion-tolerant terrestrial plants, and silty, muddy, rich substrates. This is, I think, an analogous or derivative concept to the "Walstad Method", as it embraces a more holistic approach to fostering an ecosystem; a "functionally aesthetic" aquarium, rather than a pure aesthetic one.

The importance of incorporating rich soils and silted substrates is, I think, an entirely new (and potentially dynamic) direction for blackwater/botanical-style tanks, because it not only embraces the substrate not just as a place to throw seed pods, wood, rocks, and plants- but as the literal foundation of a stable, diverse ecosystem, which facilitates the growth of beneficial organisms which become an important and integral part of the aquarium.

And that has inspired me to spend a lot of time over the past couple of years developing more "biotope-specific" substrates to compliment the type of aquariums we play with.

When we couple this use of non-conventional (for now, anyways...) substrate materials with the idea of "seeding" our aquariums with beneficial organisms (like small crustaceans, worms, etc.) to serve not only as nutrient processing "assistants", but to create a supplementary food source for our fishes, it becomes a very cool field of work.

As creatures like copepods and worms "work" the substrate and aerate and mix it, they serve to stabilize the aquarium and support the overall environment.

Nutrient cycling.

That's a huge takeaway here. I'm sure that's perhaps the biggest point of it all. By allying with the benthic life forms which inhabit it, the substrate can foster decomposition and "processing"of a wide range of materials- to provide nutrition for plants- or in our case- for the microbiome of the overall system.

There is so much work to do in this area...it's really just beginning in our little niche. And, how funny is it that what seems to be an approach that peaked and fell into a bit of disfavor or perhaps (unintended) "reclassification"- is actually being "resurrected" in some areas of the planted aquarium world ( it never "died" in others...).

And a variation/application of it is gradually starting to work it's way into the natural, botanical-method aquarium approach that we favor.

Substrates are not just "the bottom."

They are diverse harbors of life, ranging from fungal and biofilm mats, to algae, to epiphytic plants. Decomposing leaves, seed pods, and tree branches compose the substrate for a complex web of life which helps the fishes we're so fascinated by to flourish.

And, if you look at them objectively and carefully, they are beautiful.

Stay curious. Stay ob servant. Stay thoughtful. Stay bold...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquaitcs

Serendipitous spawning? Or, simply approaching fish breeding from a different angle?

After years of playing with all sorts of aspects of botanical method aquariums, you start noticing patterns and "trends" in our little speciality world. And, observing your own niche closely makes you a more keen observer of other hobby specialities, too!

I've noticed a little "trend", if you will, in some specialized areas of the hobby, such as the cichlid world, for example, which is really interesting. It seems that there has been a sort of "mental shift" from keeping cichlids in more-or-less "utilitarian", almost "sterile" setups for breeding, to aquariums that more accurately reflect the habitats from which these fishes hail from in the wild, and just sort of letting them "do their thing" naturally.

I really like this, because it means that we're paying greater attention to the "big picture" of their husbandry- not just feeding, water chemistry, and providing spawning locations. Instead, we're providing all of these things within the context of a more natural display...and hobbyists are getting great results...and they're enjoying their tanks even more!

I think it's probably the hobby's worst kept "secret" that, even if it wasn't your ambition to do so- your fishes will often spawn in your tanks by simply providing them optimum environmental conditions.

I'm not saying that the bare breeding tank with a sponge filter and a flower pot is no longer the way to approach maintenance and breeding of fishes like cichlids. I am saying that I think there is a distinct advantage to the fish-and their owners- to keeping them in a setup that is more "permanent"- and more reflective of their natural environment from a physical/aesthetic standpoint.

I recall, many years ago, keeping killifish, such as Epiplatys, Pseudoepiplatys and some Fundulopanchax, in permanent setups with lots of plants, Spanish Moss., and leaves (yeah, even back in my teens I was into 'em..). And you know what? I Would get some good spawns, and it seems like I always had some fry coming along at various stages. I am sure that some might have been consumed by the older fishes or parents along the way, but many made it through to adulthood.

I had stable breeding populations of a variety of Epiplatys species in these kinds of tanks for years. Sure, if you are raising fishes for competition, trade, etc., you'd want to remove the juveniles to a operate tank for controlled grow out, or perhaps search for, and harvest eggs so that you could get a more even grow out of fry, but for the casual (or more than causal) hobbyist, these "permanent" setups can work pretty nicely!

This is not a new concept; however, I think the idea of setting up fishes permanently and caring for them, having them spawn, and rearing the fry in the same tanks is a lot more popular than it used to be. I realize that not all fishes can be dealt with like this, for a variety of reasons. Discus, fancy guppies, etc. require more "controlled" conditions...However, do their setups have to be so starkly...utilitarian all the time?

I was talking not too long ago with a fellow hobbyist who's been trying all sorts of things to get a certain Loricarid to spawn. He's a very experienced aquarist, and has bred many varieties of fishes...but for some reason, this one is just vexing to him! I suppose that's what makes this hobby so damn engaging, huh?

And of course, I was impressed by all of the efforts he's made to get these fish to spawn thus far...But I kept thinking that there must be something fundamental-something incredibly simple, yet important- that he was overlooking...

What exactly could it be? Hard to say, but it must be something- some environmental, chemical, or physical factor, which the fish are getting in the wild, but not getting in our aquariums.

It's all the more intriguing, I suppose...

Fish breeding requires us as hobbyists to really flex some skills and patience!

When I travel around the country on speaking engagements or whatever and have occasion to visit the fish rooms of some talented hobbyists, I never cease to be amazed at what we can do! We do an amazing job. And of course, being the thoughtful type, I always wonder if there is some key thing we're missing that can help us do even better.

Now, I realize that most fish breeders like to keep things controlled to a great extent- to be able to monitor the progress, see where exactly the fishes deposit their eggs, and to be able to remove the eggs and fry if/when needed.

Control.

I mean, we strive to create the water conditions (i.e.; temperature, pH, current, lighting, etc.) for our fishes to affect spawning, but we tend to utilize more "temporary" type, artificial-looking setups with equipment to actually facilitate egg-laying, fry rearing, etc.

Purely functional.

I often wonder what is wrong with the idea of a permanent setup- a setup in which the fishes are provided a natural setting, the proper environmental conditions, and left to their own devices to "do their thing..."

Now, I realize that a lot of hardcore, very experienced breeders will scoff at this- and probably rightly so. Giving up control when the goal is the reproduction of your fishes is not a good thing. Practicality becomes important- hence the employment of clay flowerpots, spawning cones, breeding traps, bare tanks to raise fry, etc.

What do the fishes think about this?

Sure, to a fish, a cave is a cave, be it constructed of ceramic or if it's the inside of a hollowed-out seed pod. To the fish, it's a necessary place to spawn quietly and provide a defensible territory to protect the resulting fry. In all likelihood, they couldn't care less what it is made of, right? And to the serious or professional breeder, viable spawns are the game.

I get that.

I guess my personal approach to fish breeding has always been, "If it happens, great...If not, I want the fishes to have an environment that mimics the one they're found in naturally." And that works to a certain extent, but I can see how many hobbyists feel that it's certainly not the practical way to do systematic, controlled breeding.

I can't help but ruminate about this "non-approach approach" (LOL)

Not a "better spawning cone", "breeding trap", or more heartily-enriched brine shrimp. Rather, a holistic approach featuring excellent food, optimum natural water conditions, and...a physical-chemical environment reminiscent of the one they evolved in over millennia.

Won't the fishes "figure it all out?"

Yeah, I think that they will. Just a hunch I have.

And my point here is not to minimize the work of talented fish breeders worldwide, or to over-simplify things ("Just add this and your fish will make babies by the thousands!").

Nope.

It's to continue to make my case that we should, at every opportunity, continue to aspire to provide our fishes with conditions that are reminiscent of those what the evolved under for eons. I think we should make it easier for the fishes- not easier for us.

Sure, Discus can spawn and live in hard, alkaline tap water. And I know that many successful, serious breeders and commercial ventures will make a strong and compelling case for why this is so, and why it's practical in most cases.

Yet, I'm still intrigued by the possibilities of maintaining (and hopefully) spawning species like this in aquariums approximating their natural conditions on a full time basis.

Maybe I'm wrong, but I can't help but wonder if it's really possible that a couple of dozen generations of captive breeding in "unnatural conditions" could undo millions of years of evolution, which has conditioned these fish to live, grow, and reproduce in soft, alkaline, tannin-stained waters, and that our tap water conditions are "just fine" for them?

I mean, maybe it's possible...Hey, I am no scientist, but I can't help but ask if there is a reason why these fishes have evolved under such conditions so successfully? And if embracing these conditions will yield even betterlong-term results for the fishes?

I just think that there's a good possibility that I'm kind of right about that.

So, again, I think it is important for those of us who are really into creating natural aquariums for our fishes to not lose sight of the fact that there are reasons why- and benefits to- fishes having evolved under these conditions. I think that rather than adapt them to conditions easier for us to provide, that we should endeavor to provide them with conditions that are more conducive to their needs- regardless of the challenges involved.

Something to think about, right?

And , isn't their something wonderful (for those of us who are not hell-bent on controlling the time and place of our fish's spawnings) to check out your tank one night and see a small clutch of Apisto fry under the watchful eye of the mother in a Sterculia pod or whatever? Perhaps not as predictable or controllable as a more sterile breeding tank, but nonetheless, exciting!

And of course, to the serious breeder, it's just as exciting to see a bunch of wriggling fry in a PVC pipe section as it is to see them lurking about the litter bed in the display tank. I suppose it's all how you look at it.

No right or wrong answer.

The one thing that I think we can all agree with is the necessity and importance of providing optimum conditions for our potential spawning pairs. There seems to be no substitute for good food, clean water, and proper environment. Sure, there are a lot of factors beyond our control, but one thing we can truly impact is the environment in which our fishes are kept and conditioned.

On the other hand, we DO control the environment in which our fishes are kept- regardless of if the tank looks like the bottom of an Asian stream or a marble-filled 10-gallon, bare aquarium, right?

And what about the "spontaneous" spawning events that so many of you tell us have occurred in your botanical method aquariums?

Over the decades, I've had a surprisingly large number of those "spontaneous" spawning events in botanical method tanks, myself. You know, you wake up one morning and your Pencilfishes are acting weird...Next thing you know, there are clouds of eggs flying all over the tank...

That sort of stuff.

And after the initial surprise and excitement, during my "postgame analysis", I'd always try to figure out what led to the spawning event...I concluded often that was usually pure luck, coupled with providing the fishes a good environment, rather than some intentionally-spawning-focused efforts I made.

Well, maybe luck was a much smaller contributor...

After a few years of experiencing this sort of thing, I began to draw the conclusion that it was more the result of going out of my way to focus on recreating the correct environmental conditions for my fishes on a full-time basis- not just for spawning- which led to these events occurring repeatedly over the years.

With all sorts of fishes, too.

When it happened again, a couple of years ago, in my experimental leaf-litter only tank, hosting about 20 Paracheirodon simulans ("Green Neon Tetras"), I came the conclusion, in a rather circuitous sort of way, that I AM a "fish breeder" of sorts.

Well, that's not fair to legit fish breeders. More precisely, I'm a "fish natural habitat replication specialist."

A nice way of saying that by focusing on the overall environmental conditions of the aquarium on a full time basis, I could encourage more natural behaviors- including spawning- among the fishes under my care. A sort of "by product" of my practices, as opposed to the strict, stated goal.

Additionally, I've postulated that rearing young fishes in the type of environmental conditions under which they will spend the rest of their lives just makes a lot of sense to me. Having to acclimate young fishes into unfamiliar/different conditions, however beneficial they might be, still can be stressful to them.

So, why not be consistent with the environment from day one?

Wouldn't a "botanical-,method fry-rearing system", with it's abundant decomposing leaves, biofilms, and microbial population, be of benefit?

I think so.

This is an interesting, in fact, fundamental aspect of botanical-style aquariums; we've discussed it many, many times here: The idea of "on board" food cultivation for fishes.

The breakdown and decomposition of various botanical materials provides a very natural supplemental source of food for young fishes, both directly (as in the case of fishes such as wood-eating catfishes, etc.), and indirectly, as they graze on algal growth, biofilms, fungi, and small crustaceans which inhabit the botanical "bed" in the aquarium.

And of course, decomposing leaves can stimulate a certain amount of microbial growth, with infusoria, forms of bacteria, and small crustaceans, becoming potential food sources for fry. I've read a few studies where phototrophic bacteria were added to the diet of larval fishes, producing measurably higher growth rates. Now, I'm not suggesting that your fry will gorge on beneficial bacteria "cultured" in situ in your blackwater nursery and grow exponentially faster.

However, I am suggesting that it might provide some beneficial supplemental nutrition at no cost to you!

It's essentially an "evolved" version of the "jungle tanks" I reared killies in when I was a teen. A different sort of look- and function! The so-called "permanent setup"- in which the adults and fry typically co-exist, with the fry finding food amongst the natural substrate and other materials present I the tank. Or, of course, you could remove the parents after breeding- the choice is yours.

While I believe that we can be "lucky" about having fishes spawn in our tanks when that wasn't the intent, I don't believe that fishes reproduce in our tanks solely because of "luck." I mean, sure you will occasionally happen to have stumbled n the right combination of water temp, pH, current, light, or whatever- and BLAM! Spawning.

However, I think it's more of a cumulative result of doing stuff right. For a while.

So, what is wrong with the idea of a permanent setup- a setup in which the fishes are provided a natural setting, and left to their own devices to "do their thing..?"

There really is nothing "wrong" with that.

It's about wonder. Awe. The happenstance of giving your fishes exactly what they need to react in the most natural way possible.

And that's pretty cool, isn't it?

Of course, there is more to being a "successful" breeder than just having the fishes spawn. You have to rear the resulting fry, right? Sure, half the battle is just getting the fishes to lay eggs in the first place- a conformation that you're doing something right to make them comfortable enough to want to reproduce! And there is a skill set needed to rear the fry, too.

Yet, I think that with a more intensive and creative approach, our botanical-style aquariums can help with the "rearing aspect", too. Sure, it's more "hands-off" than the traditional "keep-the-fry-knee-deep-in-food-at-all-times" approach that serious breeders employ...but my less deliberate, more "hands-off" approach can work. I've seen it happen many times in my "non-breeding" tanks.

We're seeing more and more reports of "spontaneous" spawnings of all sorts of different fishes associated with blackwater conditions.

Often, it's a group of fishes that the aquarist had for a while, perhaps with little effort put into spawning them, and then it just sort of "happened." For others, it is perhaps expected- maybe the ultimate goal as it relates to a specific species...but was just taking a long time to come to fruition.

I just wonder...being a lover of the more natural-looking AND functioning aquarium, if this is a key approach to unlocking the spawning secrets of more "difficult-to-spawn" fishes. Not a "better spawning cone" or breeding trap, or more enriched brine shrimp. Rather, a wholistic approach featuring excellent food, optimum natural water conditions, and a physical environment reminiscent of the one they evolved in over millennia.

Won't the fishes "figure it all out?"

And, I wonder if fry-rearing tanks can- and should- be natural setups, too- even for serious breeders. You know, lots of plants, botanical cover, whatever...I mean, I KNOW that they can...I guess it's more of a question of if we want make the associated trade-offs? Sure, you'll give up some control, but I wonder if the result is fewer, yet healthier, more vigorous young fish?

It's not a new idea...or even a new theme here in our blog.

Now, this is pretty interesting stuff to me. Everyone has their own style of fry rearing, of course. Some hobbyists like bare bottom tanks, some prefer densely planted tanks, etc. I'm proposing the idea of rearing young fishes in a botanical-method (blackwater?) aquarium with leaves, some seed pods, and rich soil; maybe some plants as well. The physically and "functionally" mimic, at least to some extent, the habitats in which many young fishes grow up in.

My thinking is that decomposing leaves will not only provide material for the fishes to feed on and among, they will provide a natural "shelter" for them as well, potentially eliminating or reducing stresses. In Nature, many fry which do not receive parental care tend to hide in the leaves or other "biocover" in their environment, and providing such natural conditions will certainly accommodate this behavior.

Decomposing leaves can stimulate a certain amount of microbial growth, with "infusoria" and even forms of bacteria becoming potential food sources for fry. I've read a few studies where phototrophic bacteria were added to the diet of larval fishes, producing measurably higher growth rates. Now, I'm not suggesting that your fry will gorge on beneficial bacteria "cultured" in situ in your blackwater nursery and grow exponentially faster. However, I am suggesting that it might provide some beneficial supplemental nutrition at no cost to you!

I occasionally think that, in our intense effort to achieve the results we want, we sometimes will overlook something as seemingly basic as this. I certainly know that I have. And I think that our fishes will let us know, too...I mean, those "accidental" spawnings aren't really "accidental", right? They're an example of our fishes letting us know that what we've been providing them has been exactly what they needed. It's worth considering, huh?

Nature has a way. It's up to us to figure out what it is. Be it with a ceramic flower pot or pile of botanicals...

Let's keep thinking about this. And let's keep enjoying our fishes by creating more naturalistic conditions for them in our aquariums.

Stay curious. Stay enthralled. Stay diligent. Stay methodical. Stay observant...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

"Operating" our aquariums with seasonal and ecological practices.

One of the great joys in creating and working with botanical method aquairums is that we have such a wide variety of natural habitats to take inspiration from. And, as we've discussed here over the years, it's not just types of natural aquatic habitats or specific locales- it's seasons and cycles that we can emulate in our tanks as well.

I find it fascinating to think about how we can emulate the environmental characteristics of aquatic habitats during certain times of the year, such as the "wet" and "dry" seasons...and the idea of actually "operating" your aquarium to spur the environmental changes which take place during these transitions.

Do we create true seasonal variations for our aquariums? I mean, changing up lighting duration, intensity, angles, colors, increasing/decreasing water levels or flow?

With all of the high tech LED lighting systems, electronically controlled pumps; even programmable heaters- we can vary environmental conditions to mimic what occurs in our fishes' natural habitats during seasonal changes as never before. I think it would be very interesting to see what kinds of results we could get with our fishes if we went further into environmental manipulations than we have been able to before.

I mean, sure, hobbyists have been dropping or increasing temps for spawning fishes forever, and you'll see hobbyists play with light durations. Ask any Corydoras breeder. However, these are typically only in the context of defined controlled breeding experiments.

Why not simply research and match the seasonal changes in their habitat and vary them accordingly "just because", and see if you achieve different results?

We've examined the interesting Igapo and Varzea habitats of The Amazon for years now, and how these seasonally-inundated forest floors ebb and flow with aquatic life during various seasons.

And, with the "Urban Igapo", we've "operated" tanks on "wet season/dry season" cycles for a few years now, enjoying very interesting results.

I think it would be pretty amazing to incorporate gradual seasonal changes in our botanical method aquariums, to slowly increase/decrease water levels, temperature, and lighting to mimic the rainy/dry seasonal cycles which affect this habitat.

What secrets could be unlocked?

How would you approach this?

You'd need some real-item or historical weather data from the area which you're attempting to replicate, but that's readily available from multiple sources online. Then, you could literally tell yourself during the planning phases of your next tank that, "This aquarium will be set up to replicate the environmental conditions of the Igarape Panemeo in May"- and just run with it.

What are some of the factors that you'd take into account when planning such a tank? Here are just a few to get you started:

-water temperature

-ph

-water depth

-flow rate

-lighting conditions

-percentage of coverage of aquatic plants (if applicable)

-substrate composition and depth

-leaf litter accumulation

-density of fish population

-diversity of fish population

-food types

...And the list can go on and on and on. The idea being to not just "capture a moment in time" in your aquarium, but to pick up and run with it from there!

Yes, we love the concept of seasonality in our botanical method world- but not just because they create interesting aesthetic effects- but because replicating seasonal changes brings out interesting behaviors and may yield health benefits for our fishes that we may have not previously considered.

The implications of seasonality in both the natural environment- and, I believe- in our aquariums- can be quite profound.

Amazonian seasonality, for example, is marked by river-level fluctuation, also known as "seasonal pulses." The average annual river-level fluctuations in the Amazon Basin can range from approximately 12'-45' /4–15m!!! Scientists know this, because River-water-level data has been collected in some parts of the Brazilian Amazon for more than a century! The larger Amazonian rivers fall into to what is known as a “flood pulse”, and are actually due to relatively predictable tidal surge.

And of course, when the water levels rise, the fish populations are affected in many ways. Rivers overflow into surrounding forests and plains, turning the formerly terrestrial landscape into an aquatic habitat once again.

Besides just knowing the physical environmental impacts on our fishes' habitats, what can we learn from these seasonal inundations?

Well, for one thing, we can observe their impact on the diets of our fishes.

In general, fish/invertebrates, detritus and insects form the most important food resources supporting the fish communities in both wet and dry seasons, but the proportions of invertebrates, fruits, and fish are reduced during the low water season. Individual fish species exhibit diet changes between high water and low water seasons in these areas...an interesting adaptation and possible application for hobbyists?

Well, think about the results from one study of gut-content analysis form some herbivorous Amazonian fishes in both the wet and dry seasons: The consumption of fruits in Mylossoma and Colossoma species (big ass fishes, I know) was significantly less during the low water periods, and their diet was changed, with these materials substituted by plant parts and invertebrates, which were more abundant.

Tropical fishes, in general, change their diets in different seasons in these habitats to take advantage of the resources available to them.

Fruit-eating, as we just discussed, is significantly reduced during the low water period when the fruit sources in the forests are not readily accessible to the fish. During these periods of time, fruit eating fishes ("frugivores") consume more seeds than fruits, and supplement their diets with foods like leaves, detritus, and plankton.

Interestingly, even the known "gazers", like Leporinus, were found to consume a greater proportion of materials like seeds during the low water season.

The availability of different food resources at different times of the year will necessitate adaptability in fishes in order to assure their survival. Mud and algal growth on plants, rocks, submerged trees, etc. is quite abundant in these waters at various times of the year. Mud and detritus are transported via the overflowing rivers into flooded areas, and contribute to the forest leaf litter and other botanical materials, becoming nutrient sources which contribute to the growth of this epiphytic algae.

During the lower water periods, this "organic layer" helps compensate for the shortage of other food sources. And of course, this layer comprises an ecological habitat for a variety of organisms at multiple "trophic levels."

And of course, there's the "allochthonous input"- materials imported into the habitat from outside of it...When the water is at a high period and the forests are inundated, many terrestrial insects fall into the water and are consumed by fishes. In general, insects- both terrestrial and aquatic, support a large community of fishes.

So, it goes without saying that the importance of insects and fruits- which are essentially derived from the flooded forests, are reduced during the dry season when fishes are confined to open water and feed on different materials, as we just discussed.

And in turn, fishes feed on many of these organisms. The guys on the lower end of the food chain- bacterial biofilms, algal mats, and fungal growths, have a disproportionately important role in the food webs in these habitats! In fact, fungi are the key to the food chain in many tropical stream ecosystems. The relatively abundant detritus produced by the leaf litter is a very important part of the tropical stream food web.

Interestingly, some research has suggested that the decomposition of leaf litter in igapo forests is facilitated by terrestrial insects during the "dry phase", and that the periodic flooding of this habitat actually slows down the decomposition of the leaf litter (relatively speaking) because of the periodic elimination of these insects during the inundation.

And, many of the organisms which survive the inundation feed off of the detritus and use the leaf substratum for shelter instead of directly feeding on it, further slowing down the decomposition process.

AsI just touched on, much of the important input of nutrients into these habitats consists of the leaf litter and of the fungi that decompose this litter, so the bulk of the fauna found there is concentrated in accumulations of submerged litter.

And the nutrients that are released into the water as a result of the decomposition of this leaf litter do not "go into solution" in the water, but are tied up throughout in the "food web" comprised of the aquatic organisms which reside in these habitats.

This concept is foundational to our interpretation of the botanical method aquarium.

So I wonder...

Is part of the key to successfully conditioning and breeding some of the fishes found in these habitats altering their diets to mimic the seasonal importance/scarcity of various food items? In other words, feeding more insects at one time of the year, and perhaps allowing fishes to graze on detritus and biocover at other times?

And, you probably already know the answer to this question:

Is the concept of creating a "food producing" aquarium, complete with detritus, natural mud, and an abundance of decomposing botanical materials, a key to creating a more true realistic feeding dynamic, as well as an "aesthetically functional" aquarium?

Well, hell yes!

On a practical level, our botanical method aquariums function much like the habitats which they purport to represent, famously recruit biofilm and fungal growths, which we have discussed ad nasueum here over the years. These are nutritious, natural food sources for most fishes and invertebrates.

And of course, there are the associated microorganisms which feed on the decomposing botanicals and leaves and their resulting detritus.

Having some decomposing leaves, botanicals, and detritus helps foster supplemental food sources. Period.

And you don't need special botanicals, leaves, curated packs of botanicals, additives, or gear from us or anyone to create the stuff! Nature will do it all for you using whatever botanical materials you add to your aquarium!

Apparently, the years of us beating this shit into your head here on "The Tint" and elsewhere are finally striking a chord. There are literally people posting pics of their botanical method aquariums on social media every week with hashtags like #detriusthursday or whatever, preaching the benefits of the stuff that we've reviled as a hobby for a century!

That absolutely cracked me up the first time I saw people posting that. Five years ago, people literally called me an idiot online for telling hobbyists to celebrate the stuff...Now, it's a freaking hashtag. It's some weird shit, I tell you...gratifying to see, but really weird!

Now, we've briefly talked about how decomposing leaf litter and the resulting detritus it produces supports population of "infusoria"- a collective term used to describe minute aquatic creatures such as ciliates, euglenoids, protozoa, unicellular algae and small invertebrates that exist in freshwater ecosystems.

And there is much to explore on this topic. It's no secret, or surprise- to most aquarists who've played with botanicals, that a tank with a healthy leaf litter component is a pretty good place for the rearing of fry of species associated with blackwater environments!

It's been observed by many aquarists, particularly those who breed loricariids, gouramis, bettas, and characins, that the fry have significantly higher survival rates when reared in systems with leaves and other botanical present. This is significant...I'm sure some success from this could be attributed to the population of infusoria, etc. present within the system as the leaves break down.

And the insights gained by seeing first hand how fishes have adapted to the seasonal changes, and have made them part of their life cycle are invaluable to our aquarium practice.

It's an oft-repeated challenge I toss out to you- the adventurers, innovators, and bold practitioners of the aquarium hobby: follow Nature's lead whenever possible, and see where it takes you. Leave no leaf unturned, no piece of wood unstudied...push out the boundaries and blur the lines between Nature and aquarium.

Follow the seasons.

And place the aesthetic component of our botanical method aquarium practice at a lower level of importance than the function.

I'm fairly certain that this idea will make me even less popular with some in the aquarium hobby crowd who feel that the descriptor of "natural" is their exclusive purview, and that aesthetics reign supreme..Hey, I love the look of well-crafted tanks as much as anyone...but let's face it, a truly "natural" aquarium needs to embrace stuff like detritus, mud, decomposing botanical materials, varying water tint and clarity, etc.

Yes, the aesthetics of botanical method tanks might not be everyone's cup of tea, but the possibilities for creating more self-sustaining, ecologically sound microcosms are numerous, and the potential benefits for fishes are many.

It goes back to some of the stuff we've talked about before over the years here, like "pre-stocking"aquariums with lower life forms before adding your fishes- or at least attempting to foster the growth of aquatic insects and crustaceans, encouraging the complete decomposition of leaves and botanical materials, allowing biocover ("aufwuchs") to accumulate on rocks, substrate, and wood within the aquarium, utilization of a refugium, etc.during the startup phases of your tank.

All of these things are worth investigating when we look at them from a "functionality" perspective, and make the "mental shift" to visualize why a real aquatic habitat looks like this, and how its elegance and natural beauty can be every bit as attractive as the super pristine, highly-controlled, artificially laid out "plant-centric" 'scapes that dominate the minds of most aquarists when they hear the words "natural" and "aquarium" together!

Particularly when the "function" provides benefits for our animals that we wouldn't appreciate , or even see- otherwise.

At Tannin, we've pushed rather unconventional hobby viewpoints since our founding in 2015. As an aquarist, I've had these viewpoints on the hobby for decades. A desire to accept the history of our hobby, to understand how "best practices" and techniques came into being, while being tempered by a strong desire to question and look at things a bit differently. To see if maybe there's a different- or perhaps-better-way to accomplish stuff.

Most of my time in the hobby has been occupied by looking at how Nature works, and seeing if there is a way to replicate some of Her processes in the aquarium, despite the aesthetics of the processes involved, or even the results.

As a result, I've learned to appreciate Nature as She is, and have long ago given up much of my "aquarium-trained" sensibilities to "edit" or polish out stuff I see in my aquariums, simply because it doesn't fit the prevailing aesthetic sensibilities of the aquarium hobby. Now, it doesn't mean that I don't care how things look...of course not!

Rather, it means that I've accepted a different aesthetic- one that, for better or worse in some people's minds- more accurately reflects what natural aquatic habitats really look like.

And the idea of replicating the seasonal changes in our aquariums is driven not primarily from aesthetics- but from function.

To sort of put a bit of a bow on this now rather unwieldy discussion about fostering and managing our own versions of seasonal ecological systems in our aquariums, let's just revisit once again how botanical materials accomplish this in our aquariums.

The idea that we are adding these materials not only to influence the aquatic environment in our aquariums, but to provide food and sustenance for a wide variety of organisms, not just our fishes. The fundamental essence of the botanical-method aquarium is that the use of these materials provide the foundation of an ecosystem.

The essence.

Just like they are in Nature.

And the primary process which drives this closed ecosystem is... decomposition.

Decomposition of leaves and botanicals not only imparts the substances contained within them (lignin, organic acids, and tannins, just to name a few) to the water- it serves to nourish bacteria, fungi, and other microorganisms and crustaceans, facilitating basic "food web" within the botanical-method aquarium- if we allow it to!

Decomposition of plant matter-leaves and botanicals- occurs in several stages.

It starts with leaching -soluble carbon compounds are liberated during this process. Another early process is physical breakup or fragmentation of the plant material into smaller pieces, which have greater surface area for colonization by microbes.

And of course, the ultimate "state" to which leaves and other botanical materials "evolve" to is our old friend...detritus.

And of course, that very word- as we've mentioned many times here, including just minutes ago- has frightened and motivated many hobbyists over the years into removing as much of the stuff as possible from their aquariums whenever and wherever it appears.

Siphoning detritus is a sort of "thing" that we are asked about near constantly. This makes perfect sense, of course, because our aquariums- by virtue of the materials they utilize- produce substantial amounts of this stuff.

Now, the idea of "detritus" takes on different meanings in our botanical-method aquariums...Our "aquarium definition" of "detritus" is typically agreed to be dead particulate matter, including fecal material, dead organisms, mucous, etc.

And bacteria and other microorganisms will colonize this stuff and decompose/remineralize it, essentially "completing" the cycle.

And, despite their impermanence, these materials function as diverse harbors of life, ranging from fungal and biofilm mats, to algae, to micro crustaceans and even epiphytic plants. Decomposing leaves, seed pods, and tree branches make up the substrate for a complex web of life which helps the fishes that we're so fascinated by flourish throughout the various seasons.

And, if you look at them objectively and carefully, these assemblages-and the processes which form them- are beautiful. We would be well-advised to let them do their work unmolested.

On a purely practical level, these processes accomplish the most in our aquariums if we let Nature do her work without excessive intervention.

An example? How about our approach towards preparing natural materials for use in our tanks:

After decades of playing with botanical method aquariums, I'm thinking that we should do less and less preparation of certain botanical materials-specifically, wood- to encourage a slower breakdown and colonization by beneficial bacteria and fungal growths.

The "rap" on wood has always been that it gives off a lot of tint-producing tannins, much to the collective freak-out of non-botanical-method aquarium fans. However, to us, all those extra tannins are not much of an issue, right? Weigh down the wood, and let it "cure" in situ before adding your fishes!

And then there is the whole concept of getting fishes into the tank as quickly as possible.

Like, why?

We should slow our roll.

I've written and spoken about this idea before, as no doubt many of you have: Adding botanical materials to your tank, and "pre-colonizing"with beneficial life forms BEFORE you ever think of adding fishes. A way to sort of get the system "broken in", with a functioning little "food web" and some natural nutrient export processes in place.

A chance for the life forms that would otherwise likely fall prey to the fishes to get a "foothold" and multiply, to help create a sustainable population of self-generating prey items for your fishes.