- Continue Shopping

- Your Cart is Empty

Transitional Habitats...A new aquarium hobby frontier?

We've spent a lot of time over the least several years talking about the idea of recreating specialized aquatic systems. We've talked a lot about transitional habitats- ecosystems which alternate between terrestrial and aquatic at various times of the year. These are compelling ecosystems which push the very limits of conventional aquarium practice.

As you know, we take a "function first" approach, in which the aesthetics become a "collateral benefit" of the function. Perhaps the best way to replicate these natural aquatic systems inner aquariums is to replicate the factors which facilitate their function. So, for example, let's look at our fave habitats, the flooded forests of Amazonia or the grasslands of The Pantanal.

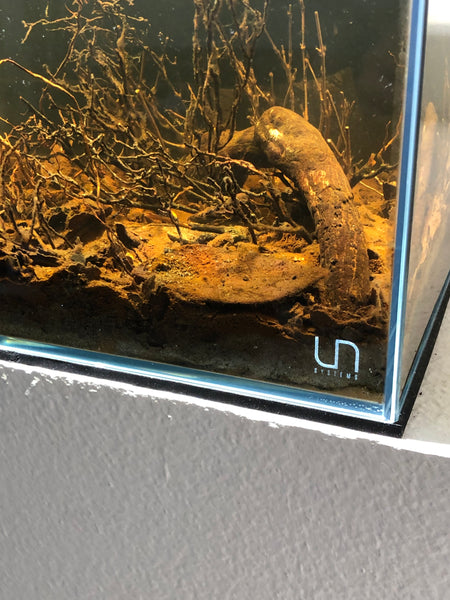

To create a system that truly embraces this idea in both form and function, you'd start the system as a terrestrial habitat. In other words, rather than setting up an "aquarium" habitat right from the start, you'd be setting up what amounts to a terrarium. Soil/sand, terrestrial plants and grasses, leaves, seed pods, and "fallen trees/branches" on the "forest floor."

You'd run this system as a terrestrial display for some extended period of time- perhaps several weeks or even months, if you can handle it- and then you'd "flood" the terrestrial habitat, turning it into an aquatic one. Now, I'm not talking about one of our "Urban Igapo" nano-sized tanks here- I"m talking about a full-sized aquarium this time.

This is different in both scale and dynamic. After the "inundation", it's likely that many of the plants and grasses will either go dormant or simply die, adding other nutrient load in the aquarium.

A microbiome of organisms which can live in the aquatic environment needs to arise to process the high level of nutrients in the aquarium. Some terrestrial organisms (perhaps you were keeping frogs?) need to be removed and re-housed.

The very process of creating and populating the system during this transitional phase from terrestrial to aquatic is a complex, fascinating, and not entirely well-understood one, at least in the aquarium hobby. In fact, it's essentially a virtually unknown one. We simply haven't created all that many systems which evolve from terrestrial to aquatic.

Sure, we've created terrariums, paludariums, etc. We've seen plenty of "seasonally flooded forest" aquairums in biotope aquarium contests...But this is different. Rather than capturing a "moment in time", recreating the aquatic environment after the inundation, we're talking about recreating the process of transformation from one habitat to another.

Literally, creating the aquatic environment from a terrestrial one.

Psychologically, it would be sort of challenging!

I mean, in this instance, you've been essentially running a "garden" for several months, enjoying it and meeting the challenges which arise, only to embark several months later on a process which essentially destroys what you've created, forcing you to start anew with an entirely different environment, and contend with all of its associated challenges (the nitrogen cycle, nutrient control, etc.)

Modeling the process.

Personally, I find this type of approach irresistible. Not only do you get to enjoy all sorts of different aspects of Nature- you get to learn some new stuff, acquire new skills, and make observations on processes that, although common in Nature, were previously unrecorded in the aquarium hobby.

You'll draw on all of your aquarium-related skills to manage this transformation. You'll deal with a completely different aesthetic- I mean, flooding an established, planted terrestrial habitat filled with soils and plants will create a turbid, no doubt chaotic-looking aquascape, at least initially.

This is absolutely analogous to what we see in Nature, by the way.Seasonal transformations are hardly neat and tidy affairs.

Yes, we place function over form. However, that doesn't mean that you can't make it pretty! One key to making this interesting from an aesthetic perspective is to create a hardscape of wood, rocks, seed pods, etc. during the terrestrial phase that will please you when it’s submerged.

You'll need to observe very carefully. You'll need to be tolerant of stuff like turbidity, biofilms, algae, decomposition- many of the "skills"we've developed as botanical-style aquarists.You need to accept that what you're seeing in front of you today will not be the way it will look in 4 months, or even 4 weeks.

You'll need incredible patience, along with flexibility and an "even keel.”

We have a lot of the "chops" we'll need for this approach already! They simply need to be applied and coupled with an eagerness to try something new, and to help pioneer and create the “methodology”, and with the understanding that things may not always go exactly like we expect they should.

For me, this would likely be a "one way trip", going from terrestrial to aquatic. Of course, much like we've done with our "Urban Igapo" approach, this could be a terrestrial==>aquatic==>terrestrial "round trip" if you want! That's the beauty of this. You could do a complete 365 day dynamic, matching the actual wet season/dry season cycles of the habitat you're modeling.

Absolutely.

The beauty is that, even within our approach to "transformational biotope-inspired" functional ecosystems, you CAN take some "artistic liberties" and do YOU. I mean, at the end of the day, it's a hobby, not a PhD thesis project, right?

Yeah. Plenty of room for creativity, even when pushing the state of the art of the hobby! Plenty of ways to interpret what we see in these unique ecosystems.

Habitats which transition from terrestrial to aquatic require us to consider the entire relationship between land and water- something that we have paid scant little attention to in the aquarium hobby, IMHO.

And this is unfortunate, because the relationships and interdependencies between aquatic habitats and their terrestrial surroundings are fundamental to our understanding of how they evolve and function.

There are so many other ecosystems which can be modeled with this approach! Floodplain lakes, streams, swamps, mud holes...I could go on and on and on. The inspiration for progressive aquariums is only limited to the many hundreds of thousands of examples which Nature Herself has created all over the planet.

We should look at nature for all of the little details it offers. We should question why things look the way they do, and postulate on what processes led to a habitat looking and functioning the way it does- and why/how fishes came to inhabit it and thrive within it.

With more and more attention being paid the overall environments from which our fishes come-not just the water, but the surrounding areas of the habitat, we as hobbyists will be able to call even more attention to the need to learn about and protect them when we create aquariums based on more specific habitats.

The old adage about "we protect what we love" is definitely true here!

And the transitional aquatic habitats are a terrific "entry point"into this exciting new area of aquarium hobby work.

Stay inspired. Stay creative. Stay observant. Stay resourceful. Stay diligent...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

No expiration date.

We talk a lot about starting up and managing botanical-style aquariums. We have had numerous discussions about set up and the accompanying expectations of the early days in the life of the little ecosystems we've created. However, what about the long term..The really long term?

Like, how long can you maintain one of these aquariums?

Do they have an "expiration date? A point when the system no longer "grows" or thrives?

There is a term, sometimes used to describe the state of very old aquariums- "senescence." The definition is: "...the condition or process of deterioration with age." Well, that doesn't sound all that unusual, right? I mean, stuff ages, gets old, stops functioning well, and eventually expires...aquariums are no different, right?

Well, I don't think so.

Sometimes, this deterioration is referred to in the hobby by the charming name of "Old Tank Syndrome"

Now, on the surface, this makes some sense, right? I mean, if your tank has been set up for several years, environmental conditions will change over time. Among the many phenomenon brought up by proponents of this theory is the increase in nitrate levels. People who buy into "OTS" will tell you that nitrate levels will increase over time.

They'll tell you that phosphate, which typically comes into our tanks with food, will accumulate, resulting in excessive, perhaps rampant, algal growths. You know, the kind from which aquarium horror stories are made.

They will tell you that the pH of the aquarium will decline as a result of accumulating nitrate, with hydrogen ions utilizing all available buffers, resulting in a reduction of the pH below 6 (like, IS that a problem?), which supposedly results in the beneficial bacteria ceasing to convert ammonia into nitrite and nitrate and creating a buildup of toxic ammonia...

I mean, it's absolutely possible. We've talked about the potential cessation of the nitrogen cycle as we know it at low pH levels, and about the archaens which take over at these low pH levels. (That's a different "thing", though, and off topic ATM)

Of course, all of the bad things espoused by the OTS theorists can and will happen...If you never do any tank maintenance. If you simply abandon the idea of water exchanges, continue stocking and feeding your aquarium recklessly, and essentially abandon the basic tenants of aquarium husbandry.

The problem with this theory is that it assumes all aquarists are knuckleheads, refusing to perform water exchanges, while merrily going about their business of watching the pretty fishes swim. It seems to forecast some sort of inevitability that this will happen to every tank.

No way. Uh-uh. I call B.S. on this.

As someone who has kept all sorts of tanks (reef tanks, freshwater fish-only tanks, etc.) in operation for many years (my longest was 13 years, and botanical-style tanks going on 5 plus years), I can't buy into this idea. I mean, sure, if you don't set up a system properly in the first place, and then simply become lackadaisical about husbandry, of course your tank can decline.

But, here's the thing: It's not inevitable.

RULE OF THUMB: Do fucking maintenance, feed carefully, and don't overstock. This is not "rocket science!"

Rather than "Old Tank Syndrome"- a name which seems to imply that it's not our fault, and that it's like some unfortunate, random occurrence which befalls the unsuspecting-we should call it LAAP- "Lazy Ass Aquarists' Payback."

'Cause that's what it IS. It's entirely the fault of a lazy-ass aquarist. Preventable and avoidable.

Need more convincing that it's not some random "malady" that can strike any tank? That it's some "universal constant" which commonly occurs in all aquariums?

Think about the wild habitats which we attempt to model our aquariums after. Do these habitats decline over time for no reason? Generally, no. They will respond to environmental changes, like drought, pollution, sedimentation, etc. They will react to these environmental pressures or insults. They will evolve over time.

Now, sure, seasonal desiccation and such result in radical environmental shifts in the the aquatic environment and a definite "expiration date"- but you seldom hear of aquatic habitats declining and disappearing or becoming otherwise uninhabitable to fishes without some significant (often human-imposed) external pressures- like pollution, ash from fires or volcanoes, deliberate diversion or draining of the water source (think "Rio Xingu"), logging operations, climate change, etc.

Of course, our aquariums are closed ecosystems. However, the same natural laws which govern the nitrogen cycle or other aspects of the system's ecology in Nature apply to our aquariums. The big difference is that our tanks are almost completely dependent upon us as aquarists applying techniques which replicate some of the factors and processes which apply in Nature. Stuff like water exchanges, etc.

So if we keep up the nutrient export processes, don't radically overstock our systems, feed appropriately, maintain filters, and observe them over time, there is no reason why we couldn't maintain our aquariums indefinitely.

There is no "expiration date."

And the cool thing about botanical-style aquariums is that part of our very "technique" from day one is to facilitate the growth and reproduction of beneficial microfauna, like bacteria, fungal growths, etc., and to allow decomposition to occur to provide them feeding opportunities.What this does is help create a microbiome of organisms which, as we've said repeatedly, form the basis of the "operating system" of our tanks.

Each one of these life forms supporting, to some extent, those above...including our fishes.

So, yeah- botanical-style aquariums are "built" for the long run. Provided that we do our fair share of the work to support their ecology. Just because we add a lot of botanical material, allow decomposition, and tend to look on the resulting detritus favorably doesn't mean that these are "set-and-forget" systems, any more than it means they're particularly susceptible to all of the problems we discussed previously.

Common sense husbandry and observation are huge components of the botanical-style aquarium "equation."

As part of our regular husbandry routine, we keep the ecosystem "stocked" with fresh botanicals and leaves on a continuous basis, to replenish those which break down via decomposition. This is perfectly analogous to the processes of leaf drop and the influx of allochthonous materials from the surrounding terrestrial habitat which occur constantly in the wild aquatic habitats which we attempt to replicate.

We favor a "biology/ecology first" mindset.

Replenishing the botanical materials provides surface area and food for the numerous small organisms which support our systems. It also provides supplemental food for our fishes, as we've discussed previously. It helps recreate, on a very real level, the "food webs" which support the ecology of all aquatic ecosystems.

And it sets up botanical-style aquariums to be sustainable indefinitely.

Radical moves and "Spring Cleanings" are not only unnecessary, IMHO- they are potentially disruptive and counter-productive. Rather, it's about deliberate moves early on, to facilitate the emergence of this biome, and then steady, regular replenishment of botanical materials to nourish and sustain the ecosystem.

My belief is steeped in the mindset that you've created a little ecosystem, and that, if you start removing a significant source of someone's food (or for that matter, their home!), there is bound to be a net loss of biota...and this could lead to a disruption of the very biological processes that we aim to foster.

Okay, it's a theory...But I think I might be on to something, maybe? So, like here is my theory in more detail:

Simply look at the botanical-style aquarium (like any aquarium, of course) as a little "microcosm", with processes and life forms dependent upon each other for food, shelter, and other aspects of their existence. And, I really believe that the environment of this type of aquarium, because it relies on botanical materials (leaves, seed pods, etc.), is significantly influenced by the amount and composition of said material to "operate" successfully over time.

No expiration date.

Personally, I don't think that botanical-style aquariums are ever "finished", BTW. They simply continue to evolve over extended periods of time, just like the wild habitats that we attempt to replicate in our tanks do.

The continuous change, development, and evolution of aquatic habitats is a fascinating, compelling area to study- and to replicate in our aquaria. I'm convinced more than ever that the secrets that we learn by fostering and accepting Nature's processes and dynamics are the absolute key to everything that we do in the aquarium.

The idea that your aquarium environment simply deteriorates as a result of its very existence is, in my humble opinion, wrong, narrow-minded, and outdated thinking. (Other than that, it's completely correct!😆).

Seriously, though...

"Old Tank Syndrome" is a crock of shit, IMHO.

Aquariums only have an "expiration date" if we don't take care of them. Period. No more sugar coating this.

If we look at them assume sort of "static diorama" thing, requiring no real care, they definitely have an "expiration date"; a point where they are no longer sustainable. When we consider our aquariums to be tiny, closed ecosystems, subject to the same "rules" which govern the natural environments which we seek to replicate, the parallels are obvious. The possibilities open up. And the potential to unlock new techniques, ideas, and benefits for our fishes is very real and truly exciting!

I'm not entirely certain how this approach to aquariums, and this idea of fostering a microbiome within our tank and caring for it has become a sort of "revolutionary" or "counter-culture" sort of thing in the hobby, as many fellow hobbyists have told me that they feel it is.

Label it what you want, I think that, if we make the effort to understand the function of our tanks as much as we do the appearance, then it all starts making sense. If you look at an aquarium as you would a garden- an organic, living, evolving, growing entity- one which requires a bit of care on our part in order to thrive-then the idea of an "expiration date" or inevitable decline of the system becomes much less logical.

Rather, it's a continuous and indefinite process.

No "end point."

Much like a "road trip", the "destination" becomes less important than the journey. It's about the experiences gleaned along the way. Enjoyment of the developments, the process. In the botanical-style aquarium, it's truly about a dynamic and ever-changing system. Every stage holds fascination.

Continuously.

An aquatic display is not a static entity, and will continue to encompass life, death, and everything in between for as long as it's in existence. There is no expiration date for our aquariums, unless we select one.

Take great comfort in that simple truth.

Stay grateful. Stay enthralled. Stay observant. Stay patient. Stay dedicated...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Great...Expectations?

By now, this whole idea of adding botanical materials to our aquariums for the purpose of helping create the physical, biological, and chemical environment of our aquariums is becoming way more familiar. Yet, no matter how many times you've created a botanical-influenced natural aquarium, the experience seems new and somehow different.

Expectations are funny things, aren't they?

There is something very pure and evocative-even a bit "uncomfortable" about utilizing botanical materials in the aquarium. Selecting, preparing, and utilizing them is more than just a practice- it's an experience. A journey. One which we can all take- and all benefit from.

Right along with our fishes, of course!

And yeah, it can even be seen as a bit of a spiritual journey, too- leading to some form of enlightenment and education about Nature, from a totally unique perspective.

The energy and creativity that you bring with you on the journey tends to become amplified during the experience. As you work with botanicals in your aquariums, your mind takes you to different places; new ideas for how your aquarium's microcosm can evolve start flooding your mind. Every tank- like every hobbyist- is different- and different inspirations arise. We don’t want everyone walking away feeling the same thing, quite the opposite actually.

That uniqueness is a large part of the experience.

The experience is largely about discovery. And today's piece is a bit about some of the interesting discoveries- expectations, and revelations that we as a community have learned along the way during our experiences working with botanicals in our aquariums.

Our aquariums evolve, as do the materials within them. We've discussed this concept many times, but it's one that we keep coming back to.

If we think of an aquarium as we do a natural aquatic ecosystem, it's certainly realistic to assume that some of the materials in the ecosystem will change, re-distribute, or completely decompose over time.

Botanicals are not "forever" aquascaping materials. We consider them ephemeral in nature. They will soften, break down, and otherwise decompose over time. Some materials, like leaves- particularly Catappa and Guava, will break down more rapidly than others, and if you're like our friend Jeff Senske of Aquaiuim Design Group, and like the look of intact leaves versus partially decomposed ones, you'll want to replace them more frequently; typically on the order of every three weeks or so, in order to have more-or-less "intact" leaves in your tank.

On the other hand, if you're like me, and enjoy the more natural look that occurs as the leaves break down, just keep 'em in. You may need to remove some materials if you find fungal growth, biofilm, or other growth unsightly or otherwise untenable, or if material gets caught up in filter inlets, etc. However, "operational concerns" aside, and if you've made that "mental shift" and can tolerate the stuff decomposing, just let them be and enjoy!

Botanicals like the really hard seed pods (Sterculia Pods", "Cariniana Pods", "Afzelia Pods"), etc., can last for many, many months, and generally will soften on their interiors long before any decomposition occurs on the exterior "shell" of he botanical. In fact, they'll typically recruit biofilms, which almost seem to serve as a sort of "protective cover" that preserves them.

Often times, fishes like Plecos, Otocinculus catfish, loaches, Headstanders, and bottom-dwelling fishes will rasp or pick at the decomposing botanicals, which further speeds up the process. Others, like Caridina shrimp, Apistos, characins, and others, will pick at biofilms covering the interior and exterior of various botanicals, as well as at the microfauna which live among them, just as they do in Nature.

Sometimes, the fishes will use botanical materials for a spawning site.

We receive a lot of questions about which botanicals will "tint the water the darkest" or whatever. Cool questions. Well, here's the deal: Virtually all botanical materials will impact the color of the water. You'll find, as we have, that different materials will impart different colors into the water. It will typically be clear, but with a golden, brownish, or perhaps a slight reddish tint.

The degree of tint imparted will be determined by various factors, such as how much of the materials you use in your tank, how long they were boiled and soaked during the preparation process, if you're using activated carbon or other chemical filter media, and how much water movement is in your system. However, rest assured, almost any botanical materials you submerge in your tank will impart some color to the water.

Unfortunately, since botanicals are natural materials, there is no "recipe'; no formula with a set "X number of leaves/pods per ___ gallons of aquarium capacity", and you'll have to use your judgement as to how much is too much! It's as much of an "art" as it is a "science!"

Now, If you really dislike the tinted water, but love the look of the botanicals you can mitigate some of this by employing a lmuch onger "post-boil" soaking period- like over a week. Keep changing the water in your soaking container daily, which will help eliminate some of the accumulating organics, as well as to help you to determine the length of time that you need to keep soaking the botanicals to minimize the tint.

Of course, it's far easier to simply employ chemical filtration media, such as activated carbon, and/or synthetic adsorbents such as Seachem Purigen, to help eliminate a good portion of the excess discoloration within the display aquarium where the botanicals will ultimately "reside."

Another interesting phenomenon about "living with your botanicals" is that they will "redistribute" throughout the aquarium. They're being moved around by both current and the activities of fishes, as well as during our maintenance activities, etc. This is, not surprisingly, very similar to what occurs in Nature, where various events carry materials like seed pods, branches, leaves, etc. to various locales within a given body of water.

In our opinion, this movement of materials, along with the natural and "assisted" decomposition that occurs, will contribute to a surprisingly dynamic environment!

Your aquarium water may appear turbid at various times. We are pretty comfortable with this idea; however, some of you may not be. As bacteria act to break down botanical materials, they may impart a bit of "cloudiness" into the the water. Also, materials such as lignin and good old terrestrial soils/silt find their way into our tanks at times.

Some of these inputs, such as soils- are intentional! Others are the unintended by-product of the materials we use, The look is definitely different than what we as aquarists have been indoctrinated to accept as "normal." One of my good friends, and a botanical-style aquarium freak, calls this phenomenon "flavor"- and we see it as an ultimate expression of a truly natural-looking aquarium.

Yeah, the water itself becomes part of the attraction. The color, the "texture", and the clarity of the water are as engrossing and fascinating as the materials which affect it. It's something that you either love or simply hate...everyone who ventures into this method of aquarium keeping needs to make their own determination of wether or not they like it.

Need a bit more convincing to embrace the charm of the water itself in botanical-style aquariums?

Simply look at a natural underwater habitat, such as an igapo or flooded varzea grassland, and see for yourself the allure of these dynamic habitats, and how they're ripe for replication in the aquarium. You'll understand how the terrestrial materials impact the now aquatic environment- the function AND the aesthetic-fundamental to the philosophy of the botanical-style aquarium.

Speaking of the impact of terrestrial materials on the aquatic habitat- remember, too, that just like in Nature, if new botanicals are added into the aquarium as others break down, you'll have more-or-less continuous influx of materials to help provide enrichment to the aquarium environment. This type of "renewal" creates a very dynamic, ever-changing physical environment, while helping keep water chemistry changes to a minimum.

This is the perfect analog to the concept of "allochthonous input" which occurs in wild aquatic habitats- materials from outside the aquatic environment- such as the surrounding forest- entering and influencing the aquatic environment.

The fishes in your system may ultimately display many interesting behaviors, such as foraging activities, territorial defense, and even spawning, as a result of this regular influx of "fresh" aquatic botanicals. You could even get pretty creative, and attempt to replicate seasonal "wet" and "dry" times by adding new materials at specified times throughout the year...The possibilities here are as diverse and interesting as the range of materials that we have to play with!

Go into this with the expectation that you might get to experience an entirely different way of looking at aquariums- and the natural environments we try to replicate- and you'll never be disappointed.

It's all a part of your "life with botanicals"- an ever-changing, always interesting dynamic that can impact your fishes in so many beneficial ways.

Stay dedicated. Stay excited. Stay engaged. Stay resourceful...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

It's about the microbiome...

As we've all started to figure out by now, our botanical-influenced aquariums are a lot more of a little slice of Nature that you're recreating in your home then they are just a "pet-holding container."

The botanical-style aquarium is a microcosm which depends upon botanical materials to impact the environment.

This microcosm consists of a myriad of life format all levels and all sizes, ranging from our fishes, to small crustaceans, worms, and countless microorganisms. These little guys, the bacteria and Paramecium and the like, comprise what is known as the "microbiome" of our aquariums.

A "microbiome", by definition, is defined as "...a community of microorganisms (such as bacteria, fungi, and viruses) that inhabit a particular environment." (according to Merriam-Webster)

Now, sure, every aquarium has a microbiome to a certain extent:

We have the beneficial bacteria which facilitate the nitrogen cycle, and play an indespensible role in the function of our little worlds. The botanical-style aquarium is no different; in fact, this is where I start wondering...It's the place where my basic high school and college elective-course biology falls away, and you get into more complex aspects of aquatic ecology in aquariums.

Yet, it's important to at least understand this concept as it can relate to aquariums. It's worth doing a bit of research and pondering. It'll educate you, challenge you, and make you a better overall aquarist. In this little blog, we can't possibly cover every aspect of this- but we can touch on a few broad points that are really fascinating and impactful.

So much of this proces-and our understanding starts with...botanicals.

With botanicals breaking down in the aquarium as a result of the growth of fungi and microorganisms, I can't help but wonder if they perform, to some extent, a role in the management-or enhancement-of the nitrogen cycle.

Yeah, you understand the nitrogen cycle, right?

How do botanicals impact this process? Or, more specifically, the microorganisms that they serve?

In other words, does having a bunch of leaves and other botanical materials in the aquarium foster a larger population of these valuable organisms, capable of processing organics- thus creating a more stable, robust biological filtration capacity in the aquarium?

I believe that they do.

With a matrix of materials present, do the bacteria (and their biofilms- as we've discussed a number of times here) have not only a "substrate" upon which to attach and colonize, but an "on board" food source which they can utilize as needed?

Facultative bacteria, adaptable organisms which can use either dissolved oxygen or oxygen obtained from food materials such as sulfate or nitrate ions, would also be capable of switching to fermentationor anaerobic respiration if oxygen is absent.

Hmm...fermentation.

Well, that's likely another topic for another time. Let's focus on some of the other more "practical" aspects of this "biome" thing.

Like...food production for our fishes.

In the case of our fave aquatic habitats, like streams, ponds, and inundated forests, epiphytes, like biofilms and fungal mats are abundant, and many fishes will spend large amounts of time foraging the "biocover" on tree trunks, branches, leaves, and other botanical materials.

The biocover consists of stuff like algae, biofilms, and fungi. It provides sustenance for a large number of fishes all types.

And of course, what happens in Nature also happens the aquarium- if we allow it to, right? And it can function in much the same way?

Yeah.

I am of the opinion that a botanical-style aquarium, complete with its decomposing leaves and seed pods, can serve as a sort of "buffet" for many fishes- even those who's primary food sources are known to be things like insects and worms and such. Detritus and the microorganisms within it can provide an excellent supplemental food source for our fishes!

Sustenence...from the microbiome.

It's well known that in many habitats, like inundated forests, etc., fishes will adjust their feeding strategies to utilize the available food sources at different times of the year, such as the "dry season", etc.

And it's also known that many fish fry feed actively on bacteria and fungi in these habitats...So I suggest once again that a botanical-style aquarium could be an excellent sort of "nursery" for many fish and shrimp species!

Again, it's that idea about the "functional aesthetics" of the, botanical-style aquariums. The idea which acknowledges the fact that the botanicals we use not only look cool, but they provide an important function (supplemental food production) as well. As we repeat constantly, the "look" is a collateral benefit of the function.

This is a profoundly important idea.

Perhaps arcane to some- but certainly not insignificant.

And of course, we've talked before about this "botanical nursery" concept- creating an aquarium for fish fry that has a large quantity of decomposing botanicals and leaves to foster the production of these materials, which serve as supplemental food for your fish fry. I have done this before myself and can attest to its viability. You fishes will have a constant supply of "natural" foods to supplement what you are feeding them in the early phases of their life.

Learn to make peace with your detritus! As always, look to the wild aquatic habitats of the world for an example of how this food source functions within the greater biome.

I'm fascinated by the "mental adjustments" that we need to make to accept the aesthetic and the processes of natural decay, fungal growth, the appearance of biofilms, and how these affect what's occurring in the aquarium. It's all a complex synergy of life and aesthetic.

And, in order to make the mental shifts which make this all work, we we have to accept Nature's input here.

Understand that, when we create a botanical-filled aquarium, not only do we have the opportunity to create an aquarium which differs significantly from those in years past- we have a unique window into the natural world and the role of these materials in the wild.

One thing that's very unique about the botanical-style approach is that we tend to accept the idea of decomposing materials accumulating in our systems. We understand that they act, to a certain extent, as "fuel" for the micro and macrofauna which reside in the aquarium, and that they perform this function as long as they are present in the system.

A profound mental shift...

And it's all about the microbiome. today's simple idea with enormous impact!

Stay curious. Stay thoughtful. Stay observant. Stay diligent...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Natural processes and the mental shifts we need to make...

We so often discuss natural processes and features in our aquarium work.

There are a lot of interesting pieces of information that we can interpret from Nature when planning, creating, and operating our aquariums. The idea of replicating natural processes and occurrences in the confines of our aquariums, by simply setting up the conditions necessary for them to occur is fundamental to our botanical-oriented approach.

It goes without saying that there are implications for both the biology and chemistry of the aquatic habitats when leaves and other botanical materials enter them. Many of these are things that we as hobbyists observe every day in our aquariums!

Example?

Well, let's talk about our old friend and sometimes nemesis, biofilm.

A lab study I came upon found out that, when leaves are saturated in water, biofilm is at its peak when other nutrients (i.e.; nitrate, phosphate, etc.) tested at their lowest limits. Hmm...This is interesting to me, because it seems that, in our botanical-style aquariums, biofilms tend to occur early on, when one would assume that these compounds are at their highest concentrations, right? And biofilms are essentially the byproduct of bacterial colonization, meaning that there must be a lot of "food" for the bacteria at some point if there is a lot of biofilm, right?

More questions...

Does this imply that the biofilms arrive on the scene and peak out really quickly; an indication that there is actually less nutrient in the water? Is the nutrient bound up in the biofilms? And when our fishes and other animals consume them, does this provide a significant source of sustenance for them? Can you have water with exceedingly low nutrient levels, while still having an abundant growth of biofilms?

Hmm...?

Oh, and here is another interesting observation:

When leaves fall into streams, field studies have shown that their nitrogen content typically will increase. Why is this important? Scientists see this as evidence of microbial colonization, which is correlated by a measured increase in oxygen consumption. This is interesting to me, because the rare "disasters" that we see in our tanks (when we do see them, of course, which fortunately isn't very often at all)- are usually caused by the hobbyist adding a really large quantity of leaves at once, resulting in the fishes gasping at the surface- a sign of...oxygen depletion?

Makes sense, right?

These are interesting clues about the process of decomposition of leaves when they enter into our aquatic ecosystems. They have implications for our use of botanicals and the way we manage our aquariums. I think that the simple fact that pH and oxygen tend to go down quickly when leaves are initially submerged in pure water during lab tests gives us an idea as to what to expect.

A lot of the initial environmental changes will happen rather rapidly, and then stabilize over time. Which of course, leads me to conclude that the development of sufficient populations of organisms to process the incoming botanical load is a critical part of the establishment of our botanical-style aquariums.

Fungal populations are equally important in the process of breaking down leaves and botanical materials in water as are higher organisms, like insects and crustaceans, which function as "shredders." So the “shredders” – the animals which feed upon the materials that fall into the streams, process this stuff into what scientists call “fine particulate organic matter.”

And that's where fungi and other microorganisms make use of the leaves and materials, processing them into fine sediments. Allochthonous material can also include dissolved organic matter (DOM) carried into streams and re-distributed by water movement.

And the process happens surprisingly quickly, too.

In experiments carried out in tropical rainforests in Venezuela, decomposition rates were really fast, with 50% of leaf mass lost in less than 10 days! Interesting, but is it tremendously surprising to us as botanical-style aquarium enthusiasts? I mean, we see leaves begin to soften and break down in a matter of a couple of weeks- with complete breakdown happening typically in a month or so for many leaves. And biofilms, fungi, and algae are still found in our aquariums in significant quantities throughout the process.

So, what's this all mean? What are the implications for aquariums?

I think it means that we need to continue to foster the biological diversity of animals in our aquariums- embracing life at all levels- from bacteria to fungi to crustaceans to worms, and ultimately, our fishes...All of which form the basis of a closed ecosystem, and perhaps a "food web" of sorts for our little aquatic microcosms.

It's a very interesting concept- a fascinating field for research for aquarists, and we all have the opportunity to participate in this on a most intimate level by simply observing what's happening in our aquariums every day!

And facilitating this process is remarkably easy:

*Approach building an aquarium as if you are creating a biome.

*Foster the growth and development of a community of organisms at all levels.

*Allow these organisms to grow and multiply.

*Don't "edit" the growth of biofilms, fungal growths, and detritus.

By accepting and embracing these changes and little "evolutions", we're helping to create really great functional representations of the compelling wild systems we love so much!

Leaf litter beds, in particular, tend to evolve the most, as leaves are among the most "ephemeral" or transient of botanical materials we use in our aquariums. This is true in Nature, as well, as materials break down or are moved by currents, the structural dynamics of the features change.

We have to adapt a new mindset when aquascaping with leaves- that being, the 'scape will "evolve" on its own and change constantly...Other than our most basic hardscape aspects- rocks and driftwood- the leaves and such will not remain exactly where we place them.

To the "artistic perfectionist"-type of aquarist, this will be maddening.

To the aquarist who makes the mental shift and accepts this "wabi-sabi" idea (yeah, I'm sort of channeling Amano here...) the experience will be fascinating and enjoyable, with an ever-changing aquascape that will be far, far more "natural" than anything we could ever hope to conceive completely by ourselves.

It's not something to freak out about.

Rather, it's something to celebrate! Life, in all of it's diversity and beauty, still needs a stage upon which to perform...and you're helping provide it, even with this "remodeling" of your aquascape taking place daily. Stuff gets moved. Stuff gets covered in biofilm.

Stuff breaks down. In our aquairums, and in Nature.

Some people cannot fully grasp that.

Recently, I had a rather one-sided "discussion" (actually, it was mostly him attacking) with a "fanboy" of a certain style of aquarium keeping, who seemed to take a tremendous amount of pleasure in telling me that "our interpretation of Nature" and our embrace of decomposing leaves, biofilms, detritus, and such is a (and I quote) "...setback for the hobby of aquascaping..." (which, those of you who know me and my desire to provoke reactions, understand that I absolutely loved hearing!) and that "it's not possible to capture Nature" with our approach... (an ignorant, almost beyond stupid POV. I mean, WTF does "capture Nature" mean? Word salad.)

I was like, "C'mon, dude. Really? This is NOT a style of aquascaping!"

We repeat this theme a million times a year here: Nature is really not always clean and tidy. In fact- most of the time, it isn't. And if you buy into the head-scratching hobby narrative that every pristine "high-concept" contest aquarium is somehow what Nature "looks like", you're simply fooling yourself.

Sure, there are some really clear, sparkling habitats out there in the world, but they represent the exception, really.

Additionally, I'll go out on a limb and suggest that none of them have tidy rows of symmetrically trimmed, color- balanced plants, or neatly arranged rocks of related size and proportion. 😆

This is directed at a small, but vocal, and apparently misinformed crowd, but I can't stress this enough:

If you really want to understand the natural aquatic habitats of our fishes, some of you have to get out of the idealized aquascaping mindset for a bit and stop dissing everything that doesn't fit your idea of the way the world should be, and just accept the realities which Nature presents...

I am actually surprised we still get the occasional DM like this.

So I occasionally push back a bit.

Unfiltered Nature.

Okay, I'm not bragging that our avant-garde love of dirty, often chaotic-looking aquariums makes us cooler than the "sterile glass pipe-loving aquascaping crowd. It's not really even a comparison, but its typically that crowd which hurls the insults at our approach, so...😆

However, I do want everyone to understand the degree to which we love the concept of Nature in it's most compelling form, and how strongly we feel that we, as a global community of hobbyists need to look beyond what's regularly presented to us as a "natural aquarium" and really give this stuff some thought. We CAN and SHOULD interpret natural aquatic features more literally in our aquairums.

Now, not all of Nature requires us to make extreme aesthetic preference shifts in order to love it.

Well, maybe not all. A lot of it, though.

It's a very different type of "aesthetic beauty" than we are used to. It's an elegant, remarkably complex microhabitat which is host to an enormous variety of life forms. And it's a radical departure from our normal interpretation of how a tank should look. It challenges us, not only aesthetically- it challenges us to appreciate the function it can provide if we let it.

"Functional aesthetics." Again.

Our "movement" believes in representing Nature as it exists in both form and function, without "editing" the very attributes of randomness and resulting function that make it so amazing.

And it all starts with understanding and facilitating natural processes without "editing" them to meet some ingrained aesthetic preferences.

Can you do that? Can you make that mental shift?

I hope so. We'd love to have you here!

Stay bold. Stay curious. Stay patient. Stay observant. Stay creative. Stay enthralled...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Epiphytes, macrophytes, allochthonous input, and other "natural" fish foods...

As a hardcore enthusiast of the blackwater/botanical-style aquarium, you're more than well-attuned to the nuances involved in managing a system filled with decomposing leaves, seed pods, wood, etc. And you're keenly aware of many of the physiological/ecological benefits that have been attributed to the use of these materials in the aquarium. However, I am willing to bet that most of us have not really considered the "nutritional" aspects of both botanicals and the life forms they foster as an important part of the "functional/aesthetic" dynamic we've touched on before.

Let's consider some of the types of food sources that our fishes might utilize in the wild habitats that we try so hard to replicate in our aquariums, and perhaps develop a greater appreciation for them when they appear in our tanks. Perhaps we will even attempt to foster and utilize them to our fishes' benefits in unique ways?

One of the important food resources in natural aquatic systems are what are known as macrophytes- aquatic plants which grow in and around the water, emerged, submerged, floating, etc. Not only do macrophytes contribute to the physical structure and spatial organization of the water bodies they inhabit, they are primary contributors to the overall biological stability of the habitat, conditioning the physical parameters of the water. Of course, anyone who keeps a planted aquarium could attest to that, right?

One of the interesting things about macrophytes is that, although there are a lot of fishes which feed directly upon them, the plants themselves are perhaps most valuable as a microhabitat for algae, zooplankton, and other organisms which fishes feed on. Small aquatic crustaceans seek out the shelter of plants for both the food resources they provide (i.e.; zooplankton, diatoms) and for protection from predators (yeah, the fishes!).

So, plants in the aquarium have been valued by aquarists "since the beginning" for all sorts of benefits- that's not really groundbreaking. I personally think that one of the more interesting functions of plants in the aquarium is to serve as this sort of "feeding ground" for fishes in all stages of their existence. Oh, yeah, they look cool, too!

Perhaps most interesting to us blackwater/botanical-style aquarium people are epiphytes. These are organisms which grow on the surface of plants or other substrates and derive their nutrients from the surrounding environment. They are important in the nutrient cycling and uptake in both nature and the aquarium, adding to the biodiversity, and serving as an important food source for many species of fishes.

In the case of our aquatic habitats, like streams, ponds, and inundated forests, epiphytes are abundant, and many fishes will spend large amounts of time foraging the biocover on tree trunks, branches, leaves, and other botanical materials. Although most animals use leaves and tree branches for shelter and not directly as a food item, grazing on this epiphytic growth is very important. Some organisms, such as nematodes and chironomids ("Bloodworms!") will dig into the leaf structures and feed on the tissues themselves, as well as the fungi and bacteria found in and among them. These organisms, in turn, become part of the diet for many fishes.

And the resulting detritus produced by the "processed" and decomposing pant matter is considered by many aquatic ecologists to be an extremely significant food source for many fishes, especially in areas such as Amazonia and Southeast Asia, where the detritus is considered an essential factor in the food webs of these habitats. And of course, if you observe the behavior of many of your fishes in the aquarium, such as characins, cyprinids, Loricarids, and others, you'll see that in between feedings, they'll spend an awful lot of time picking at "stuff" on the bottom of the tank. In a botanical style aquarium, this is a pretty common occurrence, and I believe an important benefit of this type of system.

I am of the opinion that a botanical-style aquarium, complete with its decomposing leaves and seed pods, can serve as a sort of "buffet" for many fishes- even those who's primary food sources are known to be things like insects and worms and such. Detritus and the organisms within it can provide an excellent supplemental food source for our fishes! It's well known that in many habitats, like inundated forests, etc., fishes will adjust their feeding strategies to utilize the available food sources at different times of the year, such as the "dry season", etc. And it's also known that many fish fry feed actively on bacteria and fungi in these habitats...so I suggest one again that a blackwater/botanical-style aquarium could be an excellent sort of "nursery" for many fish species!

You'll often hear the term "periphyton" mentioned in a similar context, and I think that, for our purposes, we can essentially consider it in the same manner as we do "epiphytic matter." Periphyton is essentially a "catch all" term for a mixture of cyanobacteria, algae, various microbes, and of course- detritus, which is found attached or in extremely close proximity to various submerged surfaces. Again, fishes will graze on this stuff constantly.

And then, of course, there's the "allochthonous input" that we've talked about so much here: Foods from the surrounding environment, such as flowers, fruits, terrestrial insects, etc. These are extremely important foods for many fish species that live in these habitats. We mimic this process when we feed our fishes prepared foods, as stuff literally "rains from the sky!" Now, I think that what we feed to our fishes directly in this fashion is equally as important as how it's fed.

I'd like to see much more experimentation with foods like ants, fruit flies, and other winged insects. Of course, I can hear the protests already: "Not in MY house, Fellman!" I get it. I mean, who wants a plague of winged insects getting loose in their suburban home because of some aquarium feeding experiment gone awry, right?

That being said, I would encourage some experimentation with ants and the already fairly common wingless fruit flies. Can you imagine one day recommending an "Ant Farm" as a piece of essential aquarium food culturing equipment? Why not right?

As many of you may recall, I've often been amused by the concerns many hobbyists express when a new piece of driftwood is submerged in the aquarium, often resulting in an accumulation of fungi, algal growth and biofilm. I realize this stuff looks pretty shitty to most of us, particularly when we are trying to set up a super-cool aquascaped tank. That being said, I think we need to let ourselves embrace this. I think that those of us who maintain blackwater. botanical-style aquariums have made the "mental shift" to understand, accept, and even appreciate the appearance of this stuff.

When you start seeing your fishes "graze" casually on the materials that pop up on your driftwood and botanicals, you start realizing that, although it might not look like the aesthetics we had in mind, it is a beautiful thing to our fishes. And this made me think that an "evolved" preparation technique for driftwood might be to "age" it in a large aquarium that also serves as an acclimation system for certain fishes. For example, fishes like Headstanders (Chilodus punctatus) and various loaches, catfishes, and others, would be excellent additions to this "driftwood prep tank." You could get the benefit of having the gunky stuff accumulate on the wood outside of your main display (if it bothers you, of course), while helping acclimate some cool fishes to captivity!

Just throwing the idea out there.

And of course, we've talked before about the "botanical nursery" concept- creating an aquarium for fish fry that has a large quantity of decomposing botanicals and leaves to foster the production of these materials, which serve as supplemental food for your fish fry. I have done this before myself and can attest to its viability. You fishes will have a constant supply of "natural" foods to supplement what you are feeding them in the early phases of their life. Learn to make peace with your detritus!

This little discussion has probably not created any earth-shattering "new" developments, but I believe that it has at least looked at a few of the terms you see bandied about now and again in hobby literature, perhaps clarifying their significance to us. And I think it's really about us understanding what happens in nature and how we can work with it instead of against it, taking advantage of the food sources that she provides to our fishes when we don't rush off for the algae scraper and siphon hose before considering the upside!

Another "mental shift", I suppose...one which many of you have already made, no doubt. I certainly look forward to seeing many examples of us utilizing "what we've got" to the advantage of our fishes!

Stay bold. Stay open-mined. Stay interested. Stay creative. Stay engaged.

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics