- Continue Shopping

- Your Cart is Empty

Transitional Habitats...A new aquarium hobby frontier?

We've spent a lot of time over the least several years talking about the idea of recreating specialized aquatic systems. We've talked a lot about transitional habitats- ecosystems which alternate between terrestrial and aquatic at various times of the year. These are compelling ecosystems which push the very limits of conventional aquarium practice.

As you know, we take a "function first" approach, in which the aesthetics become a "collateral benefit" of the function. Perhaps the best way to replicate these natural aquatic systems inner aquariums is to replicate the factors which facilitate their function. So, for example, let's look at our fave habitats, the flooded forests of Amazonia or the grasslands of The Pantanal.

To create a system that truly embraces this idea in both form and function, you'd start the system as a terrestrial habitat. In other words, rather than setting up an "aquarium" habitat right from the start, you'd be setting up what amounts to a terrarium. Soil/sand, terrestrial plants and grasses, leaves, seed pods, and "fallen trees/branches" on the "forest floor."

You'd run this system as a terrestrial display for some extended period of time- perhaps several weeks or even months, if you can handle it- and then you'd "flood" the terrestrial habitat, turning it into an aquatic one. Now, I'm not talking about one of our "Urban Igapo" nano-sized tanks here- I"m talking about a full-sized aquarium this time.

This is different in both scale and dynamic. After the "inundation", it's likely that many of the plants and grasses will either go dormant or simply die, adding other nutrient load in the aquarium.

A microbiome of organisms which can live in the aquatic environment needs to arise to process the high level of nutrients in the aquarium. Some terrestrial organisms (perhaps you were keeping frogs?) need to be removed and re-housed.

The very process of creating and populating the system during this transitional phase from terrestrial to aquatic is a complex, fascinating, and not entirely well-understood one, at least in the aquarium hobby. In fact, it's essentially a virtually unknown one. We simply haven't created all that many systems which evolve from terrestrial to aquatic.

Sure, we've created terrariums, paludariums, etc. We've seen plenty of "seasonally flooded forest" aquairums in biotope aquarium contests...But this is different. Rather than capturing a "moment in time", recreating the aquatic environment after the inundation, we're talking about recreating the process of transformation from one habitat to another.

Literally, creating the aquatic environment from a terrestrial one.

Psychologically, it would be sort of challenging!

I mean, in this instance, you've been essentially running a "garden" for several months, enjoying it and meeting the challenges which arise, only to embark several months later on a process which essentially destroys what you've created, forcing you to start anew with an entirely different environment, and contend with all of its associated challenges (the nitrogen cycle, nutrient control, etc.)

Modeling the process.

Personally, I find this type of approach irresistible. Not only do you get to enjoy all sorts of different aspects of Nature- you get to learn some new stuff, acquire new skills, and make observations on processes that, although common in Nature, were previously unrecorded in the aquarium hobby.

You'll draw on all of your aquarium-related skills to manage this transformation. You'll deal with a completely different aesthetic- I mean, flooding an established, planted terrestrial habitat filled with soils and plants will create a turbid, no doubt chaotic-looking aquascape, at least initially.

This is absolutely analogous to what we see in Nature, by the way.Seasonal transformations are hardly neat and tidy affairs.

Yes, we place function over form. However, that doesn't mean that you can't make it pretty! One key to making this interesting from an aesthetic perspective is to create a hardscape of wood, rocks, seed pods, etc. during the terrestrial phase that will please you when it’s submerged.

You'll need to observe very carefully. You'll need to be tolerant of stuff like turbidity, biofilms, algae, decomposition- many of the "skills"we've developed as botanical-style aquarists.You need to accept that what you're seeing in front of you today will not be the way it will look in 4 months, or even 4 weeks.

You'll need incredible patience, along with flexibility and an "even keel.”

We have a lot of the "chops" we'll need for this approach already! They simply need to be applied and coupled with an eagerness to try something new, and to help pioneer and create the “methodology”, and with the understanding that things may not always go exactly like we expect they should.

For me, this would likely be a "one way trip", going from terrestrial to aquatic. Of course, much like we've done with our "Urban Igapo" approach, this could be a terrestrial==>aquatic==>terrestrial "round trip" if you want! That's the beauty of this. You could do a complete 365 day dynamic, matching the actual wet season/dry season cycles of the habitat you're modeling.

Absolutely.

The beauty is that, even within our approach to "transformational biotope-inspired" functional ecosystems, you CAN take some "artistic liberties" and do YOU. I mean, at the end of the day, it's a hobby, not a PhD thesis project, right?

Yeah. Plenty of room for creativity, even when pushing the state of the art of the hobby! Plenty of ways to interpret what we see in these unique ecosystems.

Habitats which transition from terrestrial to aquatic require us to consider the entire relationship between land and water- something that we have paid scant little attention to in the aquarium hobby, IMHO.

And this is unfortunate, because the relationships and interdependencies between aquatic habitats and their terrestrial surroundings are fundamental to our understanding of how they evolve and function.

There are so many other ecosystems which can be modeled with this approach! Floodplain lakes, streams, swamps, mud holes...I could go on and on and on. The inspiration for progressive aquariums is only limited to the many hundreds of thousands of examples which Nature Herself has created all over the planet.

We should look at nature for all of the little details it offers. We should question why things look the way they do, and postulate on what processes led to a habitat looking and functioning the way it does- and why/how fishes came to inhabit it and thrive within it.

With more and more attention being paid the overall environments from which our fishes come-not just the water, but the surrounding areas of the habitat, we as hobbyists will be able to call even more attention to the need to learn about and protect them when we create aquariums based on more specific habitats.

The old adage about "we protect what we love" is definitely true here!

And the transitional aquatic habitats are a terrific "entry point"into this exciting new area of aquarium hobby work.

Stay inspired. Stay creative. Stay observant. Stay resourceful. Stay diligent...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

The Bloom.

It's not magic...It's Nature.

As anyone who ventures down our tinted road knows, one of the great "inevitable" of utilizing botanicals in our aquariums is the appearance of biofilms. You know, those scuzzy, nasty-looking threads of goo, which make their appearance in our tanks shortly after immersion of the botanicals (much to the chagrin of many).

Biofilm.

Even the word conjures up an image of something that you really don't want in your tank. Something dirty, yucky...potentially detrimental to your aquarium's health.

It's not.

However, let's be honest with ourselves here. The damn dictionary definition is not gonna win over many "haters":

We've long maintained that the appearance of biofilms and fungi on your botanicals and wood are to be celebrated- not feared. They represent a burgeoning emergence of life -albeit in one of its lowest and most unpleasant-looking forms- and that's a really big deal.

Biofilms form when bacteria adhere to surfaces in some form of watery environment and begin to excrete a slimy, gluelike substance, consisting of sugars and other substances, that can stick to all kinds of materials, such as- well- in our case, botanicals. It starts with a few bacteria, taking advantage of the abundant and comfy surface area that leaves, seed pods, and even driftwood offer.

The "early adapters" put out the "welcome mat" for other bacteria by providing more diverse adhesion sites, such as a matrix of sugars that holds the biofilm together. Since some bacteria species are incapable of attaching to a surface on their own, they often anchor themselves to the matrix or directly to their friends who arrived at the party first.

Tannin's creative Director, Johnny Ciotti, calls this period of time when the biofilms emerge, and your tank starts coming alive "The Bloom"- a most appropriate term, and one that conjures up a beautiful image of Nature unfolding in our aquariums- your miniature aquatic ecosystem blossoming before your very eyes!

The real positive takeaway here: Biofilms are really a sign that things are working right in your aquarium! A visual indicator that natural processes are at work, helping forge your tank's ecosystem.

I recently had a discussion with our friend, Alex Franqui (the guy who designs our cool enamel pins). His beautiful Igarape-themed aquairum pictured above, is starting to "bloom", with the biofilms and sediments working together to create a stunning, very natural look. Alex is a hardcore aquascaper, and to see him marveling and rejoicing in the "bloom" of biofilms in his tank is remarkable.

He gets it.

And it turns out that our love of biofilms is truly shared by some people who really appreciate them as food...Shrimp hobbyists! Yup, these people (you know who you are!) go out of their way to cultivate and embrace biofilms and fungi as a food source for their shrimp.

They get it.

And this makes perfect sense, because they are abundant in Nature, particularly in habitats where shrimp naturally occur, which are typically filled with botanical materials, fallen tree trunks, and decomposing leaves...a perfect haunt for biofilm and fungal growth!

Nature celebrates "The Bloom", too.

There is something truly remarkable about natural processes playing out in our own aquariums, as they have done for eons in the wild.

Remember, it's all part of the game with a botanical-influenced aquarium. Understanding, accepting, and celebrating "The Bloom" is all part of that "mental shift" towards accepting and appreciating a more truly natural-looking, natural-functioning aquarium. The "price of admission", if you will- along with the tinted water, decomposing leaves, etc., the metaphorical "dues" you pay, which ultimately go hand-in-hand with the envious "ohhs and ahhs" of other hobbyists who admire your completed aquarium when they see it for the first time.

.

The reality to us as "armchair biologists" is that the presence of these organisms in our aquariums is beautiful to us for so many reasons. It's not only a sign that our closed microcosms are functioning well, but that they are, in their own way, providing for the well- being of the inhabitants!

An abundance, created by "The Bloom."

The "mental stretches" that we ask you to make to accept these organisms and their appearance really require us to look at the wild habitats from which our fishes come, and reconcile that with our century-old aquarium hobby idealization of what Nature (and therefore our "natural" aquariums) actually look like.

Sure, it's not an easy stretch for most.

It's likely not everyone's idea of "attractive", and you'd no doubt freak out snobby contest judges with a tank full of biofilms and fungi, but to most of us, we should take great delight in knowing that we are providing our fishes with an extremely natural component of their ecosystem, the benefits of which have never really been studied in the aquarium in depth.

Why? Well, because we've been too busy looking for ways to remove the stuff instead of watching our fishes feed on it, and our aquatic environments benefit from its appearance!

We've had it all wrong, IMHO.

It's okay, we're starting to come around...

Welcome to Planet Earth.

Yet, there are always those doubts...and some are not willing to sit by and watch the "slime" take over...despite the fact that we know it's okay...

Celebrate "The Bloom."

Blurring the lines between Nature and the aquarium, from an aesthetic sense, at the very least- and in many respects, from a "functional" sense as well, proves just how far hobbyists have come...how good you are at what you do. And... how much more you can do when you turn to nature as an inspiration, and embrace it for what it is.

The same processes which occur on a grander scale in Nature also occur on a "micro-scale" in our aquariums. And we can understand and embrace these processes- rather than resist or even "revile" them- as an essential part of the aquatic environment.

Enjoy. Observe...Rejoice.

Celebrate "The Bloom."

Meet Nature where it is.

Stay excited. Stay bold. Stay inspired. Stay humble. Stay fascinated.

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Keeping it together: The beauty of "buttress roots" and their function in the flooded forests...

There is something incredibly compelling about the way terrestrial trees and shrubs interact with the aquatic environment. This is a surprisingly dynamic, highly inter-dependent relationship which has rarely been discussed in aquarium circles.

Let's have that talk!

We have talked a lot about roots before...They are structures which are so important in so many ways to these ecosystems, in both their terrestrial and aquatic phases.

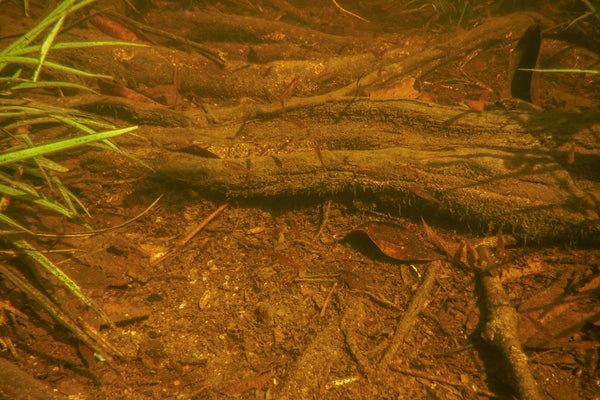

Not only do they help "secure the soils" from falling away, they foster epiphytic algae, fungal growth, and biofilms, which supplement the foods of the resident fishes. And of course, they provide a physical habitat for fishes to forage, seek shelter, and reproduce among. In short, these roots create a unique "microhabitat" which harbors a diversity of life.

And they look pretty aesthetically cool, too!

So yeah- this makes them an irresistible subject for a natural-looking- and functioning- aquascape!. And relatively easy to execute, too!

With a variety of interesting natural materials readily available to us as hobbyists, it's easier than ever to recreate these habitats in as detailed a version as you care to do.

As usual with my ramblings, this blog has become yet another homage to roots and other forest features, and how they function in the transitional aquatic habitats we love so much.

One of the foundational root types that we can replicate in or aquarium works what botanists call "buttress roots." Not only are these interesting structures to replicate in our aquariums, they are an important component of the ecosystems which make up the flooded forests, particularly in areas like Amazonia.

Buttress roots are large, very wide roots that help keep shallow-rooted forest trees from toppling over. They are commonly associated with nutrient-poor soils (you know, like the kinds you see in the igapo or varzea ecosytems). These roots also serve to take uptake nutrients are available in these podzolic soils.

The buttress roots of various species of forest trees often weave in and out of each other horizontally, and create a vast network which serves to keep many trees in the forest from toppling over. And since these habitats often flood during the rainy season, buttress roots help stabilize the trees and retain soils during this inundation.

Isn't that interesting? Even the trees have made adaptations over eons which allow them to survive under these harsh conditions! As you might suspect, the "white-water" flooded forests (Varzea) tend to be richer in species diversity and density than the less nutrient-dense blackwater-flooded Igapo forests. Seems like everything in these ecosystems is a function of nutrient availability, isn't it?

And the sandy soil which comprises these habitats is low in nutrients, such as phosphorus, potassium, calcium, and magnesium. Ecologists will tell you that the soil also has a "high infection rate", or density, of fungi, and consists of a lot of fine roots in the upper layer of the soil.

The network of fine roots helps these forests uptake nutrients in these nutrient- poor conditions. And even more interesting, studies have shown that decomposition of materials can take several years in the deep litter layer on the forest floor.

In addition to being nutrient poor, the sandy soil does not retain water very well, which can lead to drought after the inundation period is over. It's another example of the intricate relationship between land and water, and the way terrestrial and aquatic habitats work together.

Because the flood pulses are so predictable, eons of this process has led to adaptations by various forest trees to withstand them, as well as to depend upon various species of fishes ('frugivores") to help disperse seeds throughout the forest by consuming and pooping them out!

Ecologists have further determined that the distribution of various species of trees in these forests may be largely determined by the ability of their seedlings to tolerate periods of submergence and limited light that penetrates the canopy through the water column.

(Cariniana legalis tree. Image by mauroguanandi, used under CC BY 2.0)

In fact, in remarkable adaptation to this environment, seedlings may be completely submerged for several months, and many species can tolerate several weeks of complete submergence in a state of "rest." Most species in these forests tend to grow during the times year when the forests are flooded, and tend to bear fruit and flower when the waters start to recede.

It's all about adaptation to this incredible, highly variable habitat.

We talk a lot about food webs in these habitats and how to replicate some of their attributes in our aquariums. Here's another insight into the food webs of these flooded forest habitats to consider, from a paper I found by researcher Mauricio Camargo Zorro:

"Both algae and aquatic macrophytes enter in aquatic food webs mostly in form of detritus (fine and coarse particulate organic matter) or being transported by water flow and settling onto substrates (Winemiller 2004). Particulate organic matter in the stream of rapids and waterfalls is mostly associated with biofilm and epilithic diatoms that grow on rocks, submerged wood, and herbaceous plants and compose the main energy sources for macro invertebrates and other trophic links (Camargo 2009a)."

A lot there, I know. What this does is give us some ideas about facilitating the "in situ" production of supplementary food sources in our aquariums.

This was what inspired me in a recent home "planted" blackwater aquarium. The interaction between the terrestrial elements and the aquatic ones. Allowing terrestrial leaves to accumulate naturally among the "tree root structure" we have created fosters this more natural-functioning environment.

As these leaves begin to soften and ultimately break down, they foster microbial growth, biofilms, and fungal growths- all of which will provide supplemental foods for the resident fishes...just like what happens in Nature.

Facilitating these processes- allowing the materials to accumulate naturally and break down "in situ" is a key component of replicating and supporting these microhabitats in our aquariums. The typical aquarium hardscape- artistic and beautiful as it might be, generally replicates the most superficial aesthetic aspects of such habitats, and tends to overlook their function- and the reasons why such habitats form.

Replicating forest structures- like buttress roots and their functions- really helps facilitate more natural biological processes, functions, and behaviors in our fishes!

The possibilities are endless here! And, as always, the aesthetics are a "collateral benefit" of the process.

And of course, I think it's a call for us to employ some bigger, thicker pieces of wood in our tanks! Now, sure, I can hear some groans. I mean, big, heavy wood has some disadvantages in an aquarium. First, the damn things are...well- BIG- taking up a lot of physical space, and in our case, precious water volume. And the "scale" is a bit different. And, of course, a big, heavy piece of wood is kind of pricy. And physically cumbersome for some.

However, the use of larger pieces of wood- or several pieces of wood aggregated together- can create really interesting structures which can replicate the form and function of buttress roots in the aquarium.

At the very least, you can try a fairly large piece of aquatic wood (or several smaller pieces, aggregated to form one large piece) some time. I think you might find this sort of arrangement quite fascinating to play with!

Arrange the wood in such a way as to break up the tank space and give the impression that it simply rooted naturally. Let it create barriers for fishes to swim into, and disrupt water flow patterns. Allow it to "cultivate" fungal growth and biofilms on its surfaces, and small pockets where leaves, botanicals, substrate materials, and...detritus can collect.

This is exactly what happens in Nature.

It's fascinating and important for us to understand- at least on a superficial level- the concept of replicating some of the structures and features of these transitional habitats, such as flooded forest floors.

By understanding how these structures work, why the exist, and how they provide a benefit to the organisms which live among them, we will be in an excellent position to incorporate exciting features- such as buttress roots-into our future aquariums!

Stay inspired. Stay educated. Stay bold. Stay creative. Stay thoughtful...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

My Fave fish for botanical-style aquariums: Some long-overdue thoughts- Part 1 of many?

Of all of the topics we cover here in "The Tint", the one we discuss the least (rather shockingly, I might add) is the fishes that we keep in our tanks! Yeahs, I talk more about fungi, sediments, decomposition, and leaf litter than I do about fishes...

And of course, when someone hit me up the other day and asked, "Scott, what are your favorite fishes for botanical-style aquariums?" I was like, "Well, shit- I never even covered that!" I mean, we should have covered that before. It's a cool topic. I'm kind of unsure why, actually.

Probably because most of the articles on this topic are kind of...oh, crap, I'll say it- just boring. Ever read one of those "Top 10" listicle thingys about fishes? They usually-well, suck. Harsh, but they're kind of boring, IMHO. I mean, they talk about the size of the fish, what it eats, and what size tank you can keep it in. I mean, helpful, but..I dunno. Boring. Stuff you can pretty much find in any aquarium-related reference. You don't come here for that, I hope... So, we'll try to cover these fishes from "a slightly different perspective", as I like to say.

So, let's hit that topic today! Okay, let's hit some of it today...my list is longer than my patience to discuss them all in one piece! And I'll try my best not to do it the boring way...

Oh, damn, I might have a bunch of fishes...but I don't think I'm gonna cover all of them today...

Give me a break- it's a start, right?

Now, here's the thing- you'll find that my fish choices are as much based upon the habitats that they come from as they are about the fishes themselves..

Okay, so let's get this party started...

In no particular order ( well, maybe in a sort of order..):

Sailfin Characin (Crenuchus spilurus)

We've all had that ONE fish which just sort of occupies a place in our hearts and minds- a fish that-for whatever reason- bites you and never lets go, right? I think that every serious aquarist has at least one such a fish..

Here's mine...

Of course, it's also about the habitat which this fish lives in that's kept me under its spell for so long...

As a lover of leaf-litter in our natural, botanical-style aquariums, I am fascinated not only by this unique ecological niche, but by the organisms which inhabit it. I've went on and on and spoken at length about many of the microorganisms, fungi, insects, and crustaceans which add to the diversity of this environment. And of course, we've looked at some of the fishes which live there, too! Perhaps not enough, actually...

One of my all-time favorite fishes- and my absolute favorite characin is none other than the amazing "Sailfin Tetra", Crenuchus spilurus! This is a truly awesome fish- not only is it attractive and morphologically cool-looking, it has a great demeanor and behaviors which separate it from almost every other characin out there!

I first fell for this fish as a kid, when I saw a cool pic of it in my dad's well-worn copy of William T. Innes' classic book, Exotic Aquarium Fishes. The book that pretty much assured me from toddler days that I'd be a fish geek. I obsessed over the book before I could even read...

I was hooked from the start with Crenuchus, especially when reading about the romantic etymology of the name! And it just seemed so "mysterious" and unattainable, even in the 1930's...well, especially back in the 1930's, but it seemed downright exotic! To this day, it's one you just don't see too much of in the hobby. And then, tying it together with my love of those leaf-litter-strewn habitats, it was a combo which I couldn't resist!

I never got this fish out of my system, and it took me like 30-plus years of being a fish geek to find this fish in real life. And, you know that I jumped at the chance..It was so worth the wait!

It's almost "cichlid-like" in behavior: Intelligent, interactive, and endearing. It has social behaviors which will entertain and fascinate those who are fortunate enough to keep it.

Now, I admit, it's definitely NOT the most colorful characin on the planet. But there is more than this fish than meets the eye.

It all starts with its most intriguing name...

The Latin root of the genus Crenuchus means "Guardian of The Spring"- a really cool, even romantic-sounding name which evokes imagery-and questions! Does it mean the "protector" of a body of water, or some honorary homage to everyone's favorite season? Not sure, but you must agree that the name is pretty cool! In greek, it's krenoychos -"The God of running waters."

Yeah. That's the shit. I mean, do Latin names get any cooler than that?

The Crenuchidae (South American Darters) is a really interesting family of fishes, and includes 93 species in 12 genera throughout the Amazon region. Most crenuchids are- well, how do we put it delicately- "chromatically challenged" ( ie; grey-black-brown) fishes, which tend to lie in wait near the substrate (typically leaf litter or aggregations of branches), feeding on insects and micro invertebrates. And the genus Crenuchus consists of just one species, our pal Crenuchus spilurus, a fish which shares habits and a body shape that are more commonly associated with Cyprinids and...cichlids!

That's just weird.

Now, the relatively subdued coloration serves a purpose, of course. These fishes live among leaf litter, root tangles, and botanical debris..in tinted water...which demand (if you don't want to be food for bigger fishes and birds) some ability to camouflage yourself effectively.

The Sailfin is an exception to the "drab" thing, and it's remarkably attractive for a very "simple" benthic-living fish. Sure, on the surface, it's not the most exciting fish out there, especially when it's a juvenile...but it's a fish that you need to be patient with; a fish to search for, collect, hold onto, and enjoy as it matures and grows. As the fish matures, in true "ugly duckling"🐥 style, it literally "blossoms" into a far more attractive fish.

The males have an extended dorsal and anal fin, and are larger and more colorful than females. Yes, colorful is relative here, but when you see a group- you'll notice the sexual dimorphism right away, even among juveniles.

Individuals spend a lot of their time sheltered under dead leaves, branches, roots, and aquatic plants. They tend to "hover", and don't dart about like your typical Tetra would. In fact, their behavior reminds me of the Dartfishes of the marine aquarium world...They sort of sit and flick their fins, often moving in slow, deliberate motions. Communication? Perhaps.

The Sailfin feeds during the daylight hours, and spends much of its day sheltering under branches, leaves, and root tangles, and is a mid-water feeder, consuming particulate organic matter, such as aquatic invertebrates, insects, bits of flowers, and fruits- the cool food items from outside of the aquatic environment that form what ecologists call allochthonous input-materials from outside of the aquatic habitat, which are abundant in the terrestrial habitats surrounding the aquatic ones which we love to model our aquariums after.

Tucano Tetra (Tucanoichthys tucano)

You all know by now that my philosophy is to study and understand the environments from which our fishes come, and to replicate them in function and form as best as possible. It doesn't always mean exactly- but it's definitely NOT forcing them to adapt to our "local tap water "conditions without any attempt to modify them.

I have a very current "case study" of my own that sort of reflects the execution of my philosophy.

As many of you know, I've had a long obsession with the idea of root tangles and submerged accumulations of leaves, branches, and seed pods. I love the silty, sedimented substrates and the intricate interplay of terrestrial plant roots with the aquatic environment.

I was doing a geeky "deep dive" into this type of habitat in Amazonia one evening, and stumbled upon this gem from a scientific paper by J. Gery and U. Romer in 1997:

"The brook, 80-200cm wide, 50-100 cm deep near the end of the dry season (the level was still dropping at the rate of 20cm a day), runs rather swiftly in a dense forest, with Ficus trees and Leopoldina palms...in the water as dominant plants. Dead wood. mostly prickly trunks of palms, are lying in the water, usually covered with Ficus leaves, which also cover the bottom with a layer 50-100cm thick. No submerse plants. Only the branches and roots of emerge plants provide shelter for aquatic organisms.

The following data were gathered by the Junior author Feb 21, 1994 at 11:00AM: Clear with blackwater influence, extremely acid. Current 0.5-1 mv/sec. Temp.: Air 29C, water 24C at more than 50cm depth... The fish fauna seems quite poor in species. Only 6 species were collected I the brook, including Tucanoichthys tucano: Two cichlids, Nannacara adoketa, and Crenicichla sp., one catfish, a doradid Amblydoras sp.; and an as yet unidentified Rivulus, abundant; the only other characoid, probably syncopic, was Poecilocharax weitzmani."

Yeah, it turned out to be the ichthyological description of the little "Tucano Tetra", Tucanoichthys tucano, and was a treasure trove of data on both the fish and its habitat. I was taken by the decidedly "aquarium reproducible" characteristics of the habitat, both in terms of its physical size and its structure.

Boom! I was hooked.

I needed to replicate this habitat! And how could I not love this little fish? I even had a little aquarium that I had been dying to work with for a while.

It must have been "ordained" by the universe, right?

Now, I admit, I wasn't interested in, or able to safely lower the pH down to 4.3 ( which was one of the readings taken at the locale), and hold it there, but I could get the "low sixes" nailed easily! Sure, one could logically call me a sort of hypocrite, because I'm immediately conceding that I won't do 4.3, and I suppose that could be warranted...

However, there is a far cry between creating 6.2pH for my tank, which is easy to obtain and maintain for me, and "force-fitting" fishes to adapt to our 8.4pH Los Angeles tap water!

And of course, with me essentially trashing the idea of executing a hardcore 100% replication of such a specific locale, the idea was essentially to mimic the appearance and function of such an igarape habitat, replete with lots of roots and leaf litter.

And the idea of executing it in a nano-sized aquarium made the entire project more immediately attainable and a bit less daunting. I wanted to see if I could pull off a compelling biotope-inspired aquairum on a small scale.

That's where my real interest was.

So, even the "create the proper conditions for the fish instead of forcing them to adapt to what's easiest for us" philosophy can be nuanced! And it should! I don't want to mess with strong acids at this time. It's doable...a number of hobbyists have successfully. However, for the purposes of my experiment, I decided to happily abstain for now, lol.

And without flogging a dead horse, as the horrible expression goes, I think I nailed many of the physical attributes of the habitat of this fish. By utilizing natural materials, such as roots, which are representative of those found in the fish's habitat, as well as the use of Ficus and other small leaves as the "litter" in the tank, I think we created a cool biotope-inspired display for these little guys!

And man, I love this tank!

Being able to pull off many aspects of the look, feel and function of the natural habitat of the fish was a really rewarding experience. A real "case study" for my philosophy of fish selection and stocking.

Green Neon Tetra (Paracheirodon simulans)

Everyone knows the Neon Tetra, Paracheirodon inessi. It's a strong candidate for the title of "Official fish of the Aquarium Hobby!" Of course, there other members of the genus Paracheirodon which hobbyists have become enamored with, such as the diminutive, yet equally alluring P. simulans, the "Green Neon Tetra." Topping out at around 3/4" (about 2cm) in length, it's certainly deserving of the hobby label of "nano fish!"

You can keep these little guys in nice -sized aggregations..I wouldn't necessarily call them "schools", because, as our friend Ivan Mikolji beautifully observes, "In an aquarium P. simulans seem to be all over the place, each one going wherever it pleases and turning greener than when they are in the wild."

This cool little fish is one of my fave of what I call "Petit Tetras." Hailing from remote regions in the Upper Rio Negro and Orinoco regions of Brazil and Colombia, this fish is a real showstopper! According to ichthyologist Jacques Gery, the type locality of this fish is the Rio Jufaris, a small tributary of the Rio Negro in Amazonas State.

One of the rather cool highlights of this fish is that it is found exclusively in blackwater habitats. Specifically, they are known to occur in habitats called "Palm Swamps"( locally known as "campos") in the middle Rio Negro. These are pretty cool shallow water environments! Interestingly, P. simulans doesn't migrate out of these shallow water habitats (less romantically called "woody herbaceous campinas" by aquatic ecologists) like the Neon Tetra (P. axelrodi) does. It stays to these habitats for its entire lifespan.

These "campo" habitats are essentially large depressions which do not drain easily because of the elevated water table and the presence of a soil structure, created by our fave soil, hydromorphic podzol! "Hydromorphic" refers to s soil having characteristics that are developed when there is excess water present all or part of the time.

(Image by G. Durigan)

So, if you really want to get hardcore about recreating this habitat, you'd use immersion-tolerant terrestrial plants, such as Spathanthus unilateralis, Everardia montana, Scleria microcarpa, and small patches of shrubs such as Macairea viscosa, Tococa sp. and Macrosamanea simabifoli. And grasses, like Trachypogon.

Of course, our fave palm, Mauritia flexuosa and its common companion, Bactris campestris round out the native vegetation. Now, the big question is, can you find any of these plants? Perhaps...More likely, you could find substitutes.

Just Google that shit! Tons to learn about those plants!

These habitats are typically choked with roots and plant parts, and the bottom is covered with leaves and fallen palm fronds...This is right up our alley, right?

Of course, if you really want to be a full-on "baller" and replicate the natural habitat of these fishes as accurately as possible, it helps to have some information to go on! So, here are the environmental parameters from these "campo" habitats based on a couple of studies I found:

The dissolved oxygen levels average around 2.1 mg/l, and a pH ranging from 4.7-4.3. KH values are typically less than 20mg/L, and the GH generally less than 10mg/L. The conductivity is pretty low.

The water depth in these habitats, based on one study I encountered, ranged from as shallow as about 6 inches (15cm) to about 27 inches (67cm) on the deeper range. The average depth in the study was about 15" (38cm). This is pretty cool for us hobbyists, right? Shallow! I mean, we can utilize all sorts of aquariums and accurately recreate the depth of the habitats which P. simulans comes from!

We often read in aquarium literature that P. simulans needs fairly high water temperatures, and the field studies I found for this fish this confirm this.

Average daily minimum water temperature of P. simulans habitats in the middle Rio Negro was about 79.7 F (26.5 C) between September and February (the end of the rainy season and part of the dry season). The average daily maximum water temperature during the same period averaged about 81 degrees F (27.7 C). Temperatures as low as 76 degrees' (24.6 C) and as high as 95 degrees F (35.2 C) were tolerated by P. simulans with no mortality noted by the researchers.

Bottom line, you biotope purists? Keep the temperature between 79-81 degrees F (approx. 26 C-27C).

Researchers have postulated that a thermal tolerance to high water temperatures may have developed in P. simulans as these shallow "campos" became its only real aquatic habitat.

The fish preys upon that beloved catchall of "micro crustaceans" and insect larvae as its exclusive diet. Specifically, small aquatic annelids, such as larvae of Chironomidae (hey, that's the "Blood Worm!") which are also found among the substratum, the leaves and branches.

Now, if you're wondering what would be good foods to represent this fish's natural diet, you can't go wrong with stuff like Daphnia and other copepods. Small stuff makes the most sense, because of the small size of the fish and its mouthparts.

This fish would be a great candidate for an "Urban Igapo" style aquarium, in which rich soil, reminiscent of the podzols found in this habitat is use, along with terrestrial vegetation. You could do a pretty accurate representation of this habitat utilizing these techniques and substrates, and simply forgoing the wet/dry "seasonal cycles" in your management of the system.

There are a lot of possibilities here.

One of the most enjoyable and effective approaches I've taken to keeping this fish was a "leaf litter only" system (which we've written about extensively here. Not only did it provide many of the characteristics of the wild habitat (leaves, warm water temperatures, minimal water movement, and soft, acidic water).

So, maybe you've noticed a pattern to my love of certain fishes...so much is based upon the habitats that they come from. My love for the fishes was amplified when I studied and learned more about the unique habitats from which each of these fishes come. The idea of recreating various aspects of the habitat as the basis for working with these fishes is irresistible to me!

Diptail or Brown Pencilfish (Nanostomus eques)

This one really should have been the top choice if I were doing it in order. I LOVE everything about this fish. Well, almost everything.

Honestly, if a fish could earn the moniker "cool", this little guy would be it. It's absolutely not an overstatement to declare that these Pencilfishes have distinct personalities! They're not "mindless-drone, stupid schooling fishes", like some of the Tetras. (Sorry, my homies...Love ya' lots, but alas- you have no individual personalities...😂)

They are proud members of the family family Lebiasinidae. It was first described in 1876 by the legendary ichthyologist, Franz Steindachner. In fact, it was one of the first members of the genus Nanostomus to be discovered and described by science.

Cool, but that's not my main reason for loving this fish. There's a bunch of unique aspects to this fish's behavior which I find enormously compelling.

The Latin name of the species, eques, means "knight", "horseman", or "rider", in reference to this species’ unique oblique swimming angle.

Ah, that "oblique swimming angle" thing. Yeah, they swim at an angle of about 45 degrees facing upwards. This angle is thought to give them an advantage in feeding. They see insects and such that fall from overhanging vegetation better than their horizontally-oriented buddies do. They get more food that way. Simple.

(Image by Fajoe, used under CC BY-SA 3.0)

What I really love about these fish is that they are incredibly curious and obviously intelligent, checking out just about anything which goes on in their aquarium. You get the feeling when observing them that they are acutely aware of their surroundings, and once acclimated, are pretty much fearless. A fellow hobbyist once told me she thinks they're the freshwater equivalent of Pipefish...and that sounds about right..I agree with that 100%!

They're sociable, incredibly "chill" fish. Now, the thing about their ability to adeptly feed on allochthonous input into the aquatic environment makes them easy to feed. And it also gives you some clues as to the habitats they come from. Places where the food comes from the surrounding terrestrial environment.

Foods from the surrounding environment, such as flowers, fruits, terrestrial insects, etc. These are extremely important foods for many fish species that live in these habitats. We mimic this process when we feed our fishes prepared foods, as stuff literally "rains from the sky!" Now, I think that what we feed to our fishes directly in this fashion is equally as important as how it's fed.

The environments which provide this food abundance also provide lots of opportunities to replicate in our aquariums. I love that about this fish. They come from really cool, really inspiring habitats.

They are also really adept at picking on epiphytic materials in their botanical-style aquariums. It's an observation I've made many times with these fish.

Yeah, they seem to spend a large amount of time picking at biofilm and other material adhering to botanicals, and specifically, wood. They engage in this activity almost constantly throughout the day (between feedings, of course!). I am convinced that they are likely not specifically targeting the biofilm directly; rather, I think that they're looking for tiny crustaceans and other life forms that live in the matrix.

Nonetheless, their picking distrubs the films and puts it into suspension, where it can more easily be removed by filtration. This was an unexpected "plus" of this most beloved group of fishes. Now, I must warn you, biofilm haters- you shouldn't even consider Pencilfishes as a biofilm "control mechanism", but I suppose that to you heathens, the "collateral benefit" is nice.

They are very aware, very adept feeders...Always ready to pounce.

What's the thing I don't like about these fish?

Oh, they can be a bit skittish. Like, chill as they are, "stuff" just freaks them out.

They will, for seemingly no reason, launch themselves out of your open-top aquarium (well, those are the only types I keep...) with tremendous agility-sometimes landing a few inches away in the tank...Other times, completely leaving the tank, and well- usually this results in a very dried-out Pencilfish!

I guess the oblique swimming angle facilitates them reaching "escape velocity" rapidly. You get the feeling that they're always in "standby for launch!" mode. Like, full-on "defcon-5" mode.

Maybe, because they're always looking UP- the slightest disturbance from BELOW triggers a launch. I don't know, but it's as good a theory as any. And a 3-inch launch gets you away from a potential predator. A 6-inch launch lands you on the floor... Damn, a good adaptation for protection, this "launching" thing. But, like, who really wants to eat a Pencilfish, right? I guess the Pencilfish don't know that...They just jump. Millenia of genetic programming can't be overcome easily!

It sucks, but it's the downside to keeping them in open-top tanks. Lots of twisted branches and even floating plants DO help limit some of this "carpet surfing" behavior, but it's not a 100% perfect solution. I admit, These guys have, in the past played a central role in some of those "And then there were none" disappearing fish sagas that I've experienced over the years.

So, if you can keep them in a low- traffic area, employ lots of branches, and maybe some floating plants...maybe you'll avoid this.

I mean, these methods also occasionally work with Hatchetfishes...another fave of mine, but almost too suicidal, even for me. And that's why they are not in my top 10 list, if you're wondering..

Okay, I could probably do a top 10, or even a dozen- fave fishes, but I'd be writing all day on this topic. Honorable mention- The Checkerboard Cichlid (Dicrossus filamentosus)... My "go-to" cichlid for botanical-style tanks...I love them- even over Apistos...And, as one of my friends told me, "Of course you do Scott- they're fucking brown!"

Damn, my friends really know me well, huh?

Just try them in your next botanical-style aquarium. You won't regret it. Maybe we'll deep dive in the "Fellman style" on these guys next time...

Okay that's a start... I think I can safely employ the great line used by one of the aquarium hobby's great saltwater fish experts, Scott Michael, who, upon discussing such-and-such a fish would simply declare in a deadpan manner, "If you don't keep these fish, you're stupid.."

How can you argue with THAT kind of assertion? I totally relate to that. Well, shit- you asked me what my faves are...you knew I'd have some strong feelings about them, huh? 😆

Anyhow, I hope this little start gives you a look into the unorthodox way I think about the fish I select for my aquariums: So much of it is about studying a habitat I love, and then researching what fishes are found in it- and why. Then, creating the habitat for them. Like, "habitat-first." Totally works for me.

I hope it works for you too!

Until Next time...

Stay thoughtful. Stay curious. Stay bold. Stay diligent...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

New start. New approach.

One of the best things about not having a lot of tanks in operation at the moment (Wait, let's correct that...the ONLY good thing about not having a lot of tanks in operation at the moment...😆) is that it gives you the opportunity to plan, review, and plot your next moves.

I'm in such a phase at home, with my house undergoing a substantial remodel and all of my "full-size" tanks in storage for a couple more months. As I've told you previously, it's given me the opportunity to play with a lot of ideas quickly in "nano-sized" aquariums.

And of course, I've thought s lot about how I'm going to start up my next botanical-style tanks.

Here's an approach I'm trying on one of them. I call it the "transitional" approach.

Okay, we've tackled our "Urban Igapo" idea a bunch of times here, with the technique being described and studied quite a bit. Now, the repetition of wet and dry "seasonal cycles" in the aquarium, although fascinating and the most novel takeaway from this approach, is but one way to apply the idea of evolving a "dry forest floor" into an aquatic habitat.

This is one of the most incredible and fascinating ecological dynamics in Nature, and it's something that we as a hobby have not attempted to model to any extent, until we started messing around with the idea of replicating it around 2017. Again, we're not talking about replicating the 'look" of a flooded forest after it's been flooded...That has been done for years by hobbyists, particularly in biotope design contests. An "aquascaping" thing.

This is a bit different.

We're talking about actually replicating and flooding the damn forest floor! Replicating the cycle of inundation. It's a functional approach, requiring understanding, research, and patience to execute. And the aesthetics...They will follow, resembling what you see in Nature. But the primary reason is NOT for aesthetics...

So, the way this would work is to simply set up the tank like our "standard" approach to creating an "Urban Igapo"- utilizing a sedimented substrate (um, yeah, we make one....) to create a "forest floor." And then, you add leaves, botanicals, and perhaps, some terrestrial grass seeds, and even riparian plants.

You'd set whatever "hardscape" you want- driftwood, etc. in place. Of course, you'd have to water your little forest floor for some period of time, allowing the vegetation to sprout and grow. Based on the many times of played with the "Igapo" idea, this process typically takes around 2-3 months to establish the growth well.

And then what? Well, you'd flood it!

You could do this all at one time, or over the course of several days, depending upon your preference. I mean, you've waited a couple of months to add water to your tank...what's another few days? 😆 Now, sure, there's a difference between a 5-gallon tank and a 50- gallon tank, and it takes a lot longer to fill, so it's up to you how you want to approach this!

And what you'd initially end up with is a murky, tinted environment, with little bits of leaves, botanicals, and soil floating about. Sounds like a blast, huh? And when you think about it, this is not all that different, at least procedurally, from the "dry start" approach to a planted tank...except we're not talking about a planted tsmnk here.. I mean, you could do aquatic plants...but it's more of a "wholistic biome" approach...

The interesting thing about this approach is that you will see a tank which "cycles" extremely quickly, in my experience. In fact, Iv'e done many iterations of "Urban Igapo" tanks where there was no detectible "cycle" in the traditional sense. I don't have an explanation for this, except to postulate that the abundance of bacterial and microorganism growth, and other life forms, like fungal growths, etc., powered by the nutrients available to them in the established terrestrial substrate expedites this process dramatically.

That's my theory, of course, and I could be way, way off base, but it is based on my experience and that of others in our community over the past several years. I mean, there is a nitrogen cycle occurring in the dry substrate, so when it's inundated, do the bacteria make the transition, or do they perish, followed by the very rapid colonization by other species, or..?

An underwater biome is created immediately with this approach. Doing this type of "transition" is going to not only create a different sort of underwater biodiversity, it will have the "collateral benefit" of creating a very different aesthetic as well. And yeah, it's an aesthetic that will be dictated by Nature, and will encompass all of those things that we know and love- biofilms, fungal growth, decomposition, etc.

I've done this in aquariums up to 10 gallons so far, with great success, so I'm completely convinced that this process can be "scaled up" easily. The technique is the same.

Now, one fundamental difference between this approach and the more "traditional" "Urban Igapo" approach is that it's a "one way trip"- start our dry and take it to "wet", without going through repetitive dry cycles. The interesting thing to me about this approach is that you're going to have a very nutrient-rich aquarium habitat, with a big diversity of life from the start.

It's still early days.

ms.

There is so much to learn and experiment with. Every single one of us, when we embark on a botanical-style aquarium adventure- is playing a key role in contributing to the "state of the art" of the aquarium hobby! Everycontribution is important...

Enjoy the process!

Stay curious. Stay observant. Stay experimental. Stay bold...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Epiphytes, macrophytes, allochthonous input, and other "natural" fish foods...

As a hardcore enthusiast of the blackwater/botanical-style aquarium, you're more than well-attuned to the nuances involved in managing a system filled with decomposing leaves, seed pods, wood, etc. And you're keenly aware of many of the physiological/ecological benefits that have been attributed to the use of these materials in the aquarium. However, I am willing to bet that most of us have not really considered the "nutritional" aspects of both botanicals and the life forms they foster as an important part of the "functional/aesthetic" dynamic we've touched on before.

Let's consider some of the types of food sources that our fishes might utilize in the wild habitats that we try so hard to replicate in our aquariums, and perhaps develop a greater appreciation for them when they appear in our tanks. Perhaps we will even attempt to foster and utilize them to our fishes' benefits in unique ways?

One of the important food resources in natural aquatic systems are what are known as macrophytes- aquatic plants which grow in and around the water, emerged, submerged, floating, etc. Not only do macrophytes contribute to the physical structure and spatial organization of the water bodies they inhabit, they are primary contributors to the overall biological stability of the habitat, conditioning the physical parameters of the water. Of course, anyone who keeps a planted aquarium could attest to that, right?

One of the interesting things about macrophytes is that, although there are a lot of fishes which feed directly upon them, the plants themselves are perhaps most valuable as a microhabitat for algae, zooplankton, and other organisms which fishes feed on. Small aquatic crustaceans seek out the shelter of plants for both the food resources they provide (i.e.; zooplankton, diatoms) and for protection from predators (yeah, the fishes!).

So, plants in the aquarium have been valued by aquarists "since the beginning" for all sorts of benefits- that's not really groundbreaking. I personally think that one of the more interesting functions of plants in the aquarium is to serve as this sort of "feeding ground" for fishes in all stages of their existence. Oh, yeah, they look cool, too!

Perhaps most interesting to us blackwater/botanical-style aquarium people are epiphytes. These are organisms which grow on the surface of plants or other substrates and derive their nutrients from the surrounding environment. They are important in the nutrient cycling and uptake in both nature and the aquarium, adding to the biodiversity, and serving as an important food source for many species of fishes.

In the case of our aquatic habitats, like streams, ponds, and inundated forests, epiphytes are abundant, and many fishes will spend large amounts of time foraging the biocover on tree trunks, branches, leaves, and other botanical materials. Although most animals use leaves and tree branches for shelter and not directly as a food item, grazing on this epiphytic growth is very important. Some organisms, such as nematodes and chironomids ("Bloodworms!") will dig into the leaf structures and feed on the tissues themselves, as well as the fungi and bacteria found in and among them. These organisms, in turn, become part of the diet for many fishes.

And the resulting detritus produced by the "processed" and decomposing pant matter is considered by many aquatic ecologists to be an extremely significant food source for many fishes, especially in areas such as Amazonia and Southeast Asia, where the detritus is considered an essential factor in the food webs of these habitats. And of course, if you observe the behavior of many of your fishes in the aquarium, such as characins, cyprinids, Loricarids, and others, you'll see that in between feedings, they'll spend an awful lot of time picking at "stuff" on the bottom of the tank. In a botanical style aquarium, this is a pretty common occurrence, and I believe an important benefit of this type of system.

I am of the opinion that a botanical-style aquarium, complete with its decomposing leaves and seed pods, can serve as a sort of "buffet" for many fishes- even those who's primary food sources are known to be things like insects and worms and such. Detritus and the organisms within it can provide an excellent supplemental food source for our fishes! It's well known that in many habitats, like inundated forests, etc., fishes will adjust their feeding strategies to utilize the available food sources at different times of the year, such as the "dry season", etc. And it's also known that many fish fry feed actively on bacteria and fungi in these habitats...so I suggest one again that a blackwater/botanical-style aquarium could be an excellent sort of "nursery" for many fish species!

You'll often hear the term "periphyton" mentioned in a similar context, and I think that, for our purposes, we can essentially consider it in the same manner as we do "epiphytic matter." Periphyton is essentially a "catch all" term for a mixture of cyanobacteria, algae, various microbes, and of course- detritus, which is found attached or in extremely close proximity to various submerged surfaces. Again, fishes will graze on this stuff constantly.

And then, of course, there's the "allochthonous input" that we've talked about so much here: Foods from the surrounding environment, such as flowers, fruits, terrestrial insects, etc. These are extremely important foods for many fish species that live in these habitats. We mimic this process when we feed our fishes prepared foods, as stuff literally "rains from the sky!" Now, I think that what we feed to our fishes directly in this fashion is equally as important as how it's fed.

I'd like to see much more experimentation with foods like ants, fruit flies, and other winged insects. Of course, I can hear the protests already: "Not in MY house, Fellman!" I get it. I mean, who wants a plague of winged insects getting loose in their suburban home because of some aquarium feeding experiment gone awry, right?

That being said, I would encourage some experimentation with ants and the already fairly common wingless fruit flies. Can you imagine one day recommending an "Ant Farm" as a piece of essential aquarium food culturing equipment? Why not right?

As many of you may recall, I've often been amused by the concerns many hobbyists express when a new piece of driftwood is submerged in the aquarium, often resulting in an accumulation of fungi, algal growth and biofilm. I realize this stuff looks pretty shitty to most of us, particularly when we are trying to set up a super-cool aquascaped tank. That being said, I think we need to let ourselves embrace this. I think that those of us who maintain blackwater. botanical-style aquariums have made the "mental shift" to understand, accept, and even appreciate the appearance of this stuff.

When you start seeing your fishes "graze" casually on the materials that pop up on your driftwood and botanicals, you start realizing that, although it might not look like the aesthetics we had in mind, it is a beautiful thing to our fishes. And this made me think that an "evolved" preparation technique for driftwood might be to "age" it in a large aquarium that also serves as an acclimation system for certain fishes. For example, fishes like Headstanders (Chilodus punctatus) and various loaches, catfishes, and others, would be excellent additions to this "driftwood prep tank." You could get the benefit of having the gunky stuff accumulate on the wood outside of your main display (if it bothers you, of course), while helping acclimate some cool fishes to captivity!

Just throwing the idea out there.

And of course, we've talked before about the "botanical nursery" concept- creating an aquarium for fish fry that has a large quantity of decomposing botanicals and leaves to foster the production of these materials, which serve as supplemental food for your fish fry. I have done this before myself and can attest to its viability. You fishes will have a constant supply of "natural" foods to supplement what you are feeding them in the early phases of their life. Learn to make peace with your detritus!

This little discussion has probably not created any earth-shattering "new" developments, but I believe that it has at least looked at a few of the terms you see bandied about now and again in hobby literature, perhaps clarifying their significance to us. And I think it's really about us understanding what happens in nature and how we can work with it instead of against it, taking advantage of the food sources that she provides to our fishes when we don't rush off for the algae scraper and siphon hose before considering the upside!

Another "mental shift", I suppose...one which many of you have already made, no doubt. I certainly look forward to seeing many examples of us utilizing "what we've got" to the advantage of our fishes!

Stay bold. Stay open-mined. Stay interested. Stay creative. Stay engaged.

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics