- Continue Shopping

- Your Cart is Empty

Streaming along...

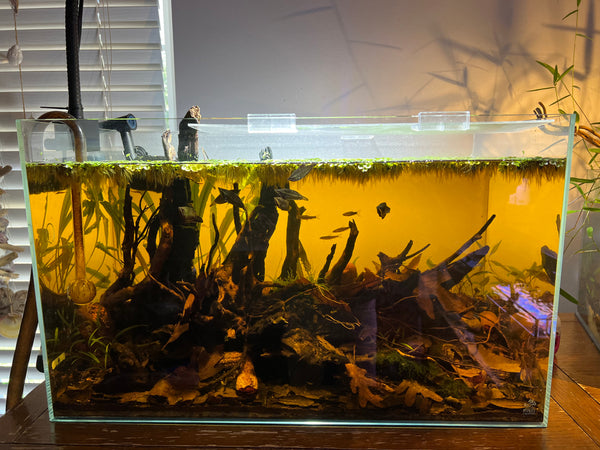

There is a whole, fascinating science to river and stream structure, and with so many implications for understanding how these structures and mechanisms affect fish population, occurrence, behavior, and ecology, it's well worth studying for aquarium interpretation!

Leaf litter beds form in what stream ecologists call "meanders", which are stream structures that form when moving water in a stream erodes the outer banks and widens its "valley", and the inner part of the river has less energy and deposits silt- or in our instance, leaves.

Did you get that part where I mentioned that the lower-energy parts of the water courses tend to accumulate leaves and sediments and stuff?

It's logical, right? And it's also interesting, because, as we know, fishes and their food items tend to aggregate in these areas, and embracing the "theme" of a litter/botanical bed or even wood placement, in the context of a stream structure in the aquarium is kind of cool!

You could build upon, structure, and replace leaves and botanicals in this "framework"- like, indefinitely...sort of like what happens in the "meanders in streams!"

In Nature, the rain and winds also effect the depth and flow rates of many of the waters in this region, with the associated impacts mentioned above, as well as their influence on stream structures, like submerged logs, sandbars, rocks, etc.

Stuff gets redistributed constantly.

Is there an aquarium "analog" for these processes?

Sure!

We might move a few things around now and again during maintenance, or perhaps current or the fishes themselves act to redistribute and aggregate botanicals and leaves in different spots in our aquairums.

And how we structure the more "permanent" hardscape features in our tanks has a profound influence on how botanical materials can aggregate.

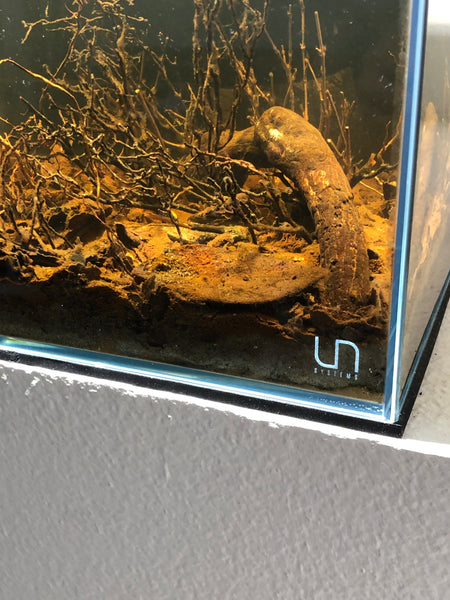

So, rather than covering the whole bottom of your tank with leaves, would it be cool to create some sort of hardscape structure- with driftwood, etc., to retain or keep these items in one place..to create a "framework" for a long-term, organized, specifically-placed litter bed.

The composition of bottom materials and the depth of the channel are always changing in response to the flow in a given stream, affecting the composition and ecology in many ways. I'll probably state this idea more than once in this piece, because it's really important:

Every stream is unique. Although there are standard structural or functional elements common to many streams, each stream is essentially a "custom response" to local ecological, topographical, meteorological, and biological factors.

Permanent streams will often have different volume and material composition (usually finely-packed sands and gravels, with lots of smooth stones) than more intermittent streams, which are the result of inundation caused by rain, etc., or even so-called "ephemeral" streams, often packed with leaves and lighter sediments, which typically occur only immediately after rain events (which means they usually don't have fish in them unless they are washed into them from more permanent watercourses).

The latter two stream types are typically more affected by leaves, botanical debris, branches, and other materials. Like the igarapes ("canoe ways") of Brazil...little channels and rivulets which come and go with the seasonal rains. And then, there's those flooded Igapo forests we obsess over.

In the overall Amazon region (you knew I was sort of headed back that way, right?), it sort of works both ways, with the rivers influencing the surrounding land...and then the land "giving" some of the materials back to the rivers...the extensive lowland areas bordering the river and its tributaries, known as varzeas (“floodplains”), are subject to annual flooding, which helps foster enrichment of the aquatic environment.

Much of them come from trees.

Yeah, trees.

The materials that comprise the tree are known in ecology as "allochthonous material"- something imported into an ecosystem from outside of it. (extra points if you can pronounce the word on the first try...) And of course, in the case of trees, this also includes includes leaves, fruits and seed pods that fall or are washed into the water along with the branches and trunks that topple into the stream.

You know, the stuff we obsess over around here!

Although many streams derive their food base from leaves and organic matter, there is a lot of other material present that contributes to its structure. Think along those lines when scheming your next aquarium. Ask yourself what factors would contribute to the bottom composition of the area you're taking inspiration from.

There seems to be a pervasive mindset within the botanical method aquarium hobby that you need to incorporate a wide variety of botanicals into every aquarium. I would like to go on record right now to state that this is simply untrue. You can use as little or as much diversity of materials as you'd like;

Nature doesn't have a "standard" for this!

It's a "guideline" which I believe vendors have placed into the collective consciousness of the hobby for reasons that are not entirely altruistic. Personally, I will only use a one or two types of botanical materials in a given aquarium. Maybe three, but that's typically it. This mindset was forged by both my aesthetic preferences and my studying of the characteristics of many of the natural habitats which we model our aquariums after.

They simply don't have an unlimited variety of materials present. Rather, the composition of the accumulated materials in most wild aquatic habitats is limited- often based upon the plants in the immediate vicinity, as well as other factors, like currents (when present) and winds. During storms, materials can be re-distributed from outside of the immediate environment, adding to the diversity of accumulation.

In general, one of the ecological roles of streams are to distribute materials throughout the greater ecosystem. Streams have interesting morphologies. It's interesting to consider the structural components of a stream, to get a better picture of how it forms and functions. What are the key components of streams?

Well, there is the top end of a stream, where its flow begins..essentially, its source. The "bottom end" of a stream is known as its "mouth." In between, the stream flows through its main course, also known as a "trunk." Streams gain their water through runoff, the combined input of water from the surface and subsurface.

Streams which flow over stony, open bottoms, free from natural obstacles like tree trunks and such, tend to develop a rich algal turf on their surfaces.

While not something a lot of hobbyists like to see in their tanks (with the exception of Mbuna guys and weirdos like me), algae-covered stones and rocks are entirely natural and appropriate for the bottom of many aquariums! (enter a tank with THAT in the next international aquascaping contest and watch the ensuing judge "freak-out" it causes! )

Grazing fishes, of course, will feed extensively on or among these algal films, and would be logical choices for a stony-bottom-themed aquarium. Like Labeo ("Sharks"), Darter characins, and barbs. When we think about the way natural fish communities are assembled in rivers and streams, it's almost always as a result of adaptations to the physical environment and food resources.

Now, not everyone wants to have algae-covered stones or a mass of decomposing leaves on the bottom of their aquarium. I totally get THAT! However, I think that considering the role that these materials play in the composition of streams and the lives of the fishes which inhabit them is important, and entirely consistent with our goal of creating the most natural, effective aquariums for the animals which we keep.

As a hobbyist, you can employ elements of these natural systems in a variety of aquariums, using any number of readily-available materials to do the job. And, let's face it; pretty much no matter how we 'scape a tank- no matter how much- or how little- thought and effort we put into it, our fishes will ultimately adapt to it.

They'll find the places they are comfortable hiding in. The places they like to forage, sleep and spawn. It doesn't matter if your 'scape consists of carefully selected roots, seed pods, rocks, plants, and driftwood, or simply a couple of clay flower pots and a few pieces of egg crate- your fishes will "make it work."

As aquarists, observing, studying, and understanding the specifics of streams is a fascinating and compelling part of the hobby, because it can give us inspiration to replicate the form and more important- the function- of them in our tanks!

Now, you're also likely aware of the fact that we're crazy about small, shallow bodies of water, right? I mean, almost every fish geek is like "genetically programmed" to find virtually any random body of water irresistible!

Especially little rivulets, pools, creeks, and the aforementioned forest streams. The kinds which have an accumulation of leaves and botanical materials on the bottom. Darker water, submerged branches- all of that stuff...

You know- the kind where you'll find fishes!

Happily, such habitats exist all over the world, leaving us no shortage of inspiring places to attempt to replicate. Like, everywhere you look!

In Africa for example, many of these little streams and pools are home to some of my fave fishes, killifish! This group of fishes is ecologically adapted to life in a variety of unusual habitats, ranging from puddles to small streams to mud holes. However, many varieties occur in those streams in the jungles of Africa.

And many of these little jungle streams are really shallow, cutting gently through accumulations of leaves and forest debris. Many are seasonal. The great killie documenter/collector, Col. Jorgen Scheel, precisely described the water conditions found in their habitat as "...rather hot, shallow, usually stagnant & probably soft & acid."

Ah-ah! We know this territory pretty well, right?

I think we do...and understanding this type of habitat has lots of implications for creating very cool biotope-inspired aquariums.

And why not make 'em for killifish?

So, yeah- we keep talking about "very shallow jungle streams." How shallow? Well, reports I've seen have stated that they're as shallow as 2 inches (5.08cm). That's really shallow. Seriously shallow! And, quite frankly, I'd call that more of a "rivulet" than a stream!

"Virtually still, with a barely perceptible current..." was one description. That kind of makes my case!

What does that mean for those of us who keep small aquariums?

Well, it gives us some inspiration, huh? Ideas for tanks that attempt to replicate and study these compelling shallow environments...

Now, I don't expect you to set up a tank with a water level that's 2 inches deep..And, although it would be pretty cool, for more of us, perhaps a 3.5"-4" (8.89-10.16cm) of depth is something that can work? Yeah. Totally doable. There are some pretty small commercial aquariums that aren't much deeper than 6"-8" (20.32cm).

We could do this with some of the very interesting South American or Asian habitats, too...Shallow tanks, deep leaf litter, and even some botanicals for good measure.

How about a long, low aquarium, like the ADA "60F", which has dimensions of 24"x12"x7" (60x30x18cm)? You would only fill this tank to a depth of around 5 inches ( 12.7cm) at the most. But you'd use a lot of leaves to cover the bottom...

Yeah, to me, one of the most compelling aquatic scenes in Nature is the sight of a stream meandering into the forest.

There is something that calls to me- beckons me to explore, to take not of its intricate details- and to replicate some of its features in an aquarium- sometimes literally, or sometimes,. just taking components that I find compelling and utilizing them.

An important consideration when contemplating such a replication in our tanks is to consider just how these little forests streams form. Typically, they are either a small tributary of a larger stream, with the path carved out by rain or erosion over time. In other situations, they may simply be the result of an overflowing tributary during the rainy season, and as the waters recede later in the year, they evolve into smaller streams meandering through vegetation.

Those little streams fascinate me.

In Brazil, they are known as igarape, derived from the native Brazilian Tupi language. This descriptor incorporates the words "ygara" (canoe) and "ape"(way, passage, or road) which literally translates into "canoe way"- a small body of water which forms a route navigable by canoes.

A literal path through the forest!

These interesting little tributaries areare shaded by trees at the margins, and often cut for many kilometers through dense rain forest. The bottoms of these tributaries- formerly forest floor- are often covered with seed pods, twigs, leaves, and other botanical materials from the vegetation above and surrounding them.

Although igapó forests are characterized by sandy acidic soils that have a low nutrient content, the tributaries that feed them are often found over a fine-grained, whitish sand, so as an aquarist, you a a lot of options for substrate!

In this world of decomposing leaves, submerged logs, twigs, and seed pods, there is a surprising diversity of life forms which call this milieu home. And each one of these organisms has managed to eke out an existence and thrive.

A lot of hobbyists not familiar with our aesthetic tastes will ask what the fascination is with throwing palm fronds and seed pods into our tanks, and I tell them that it's a direct inspiration from Nature! Sure, the look is quite different than what has been proffered as "natural" in recent years- but I'd guarantee that, if you donned a snorkel and waded into one of these habitats, you'd understand exactly what we are trying to represent in our aquariums in seconds!

Streams, rivulets...whatever they're called- they beckon us. Compel us. And challenge us to understand and interpret Nature in exciting new ways in our aquariums.

I think we're starting to see a new emergence of a more "holistic" approach to aquarium keeping...a realization that we've done amazing things so far, keeping fishes and plants in a glass or acrylic box with applied technique and superior husbandry...but that there is room to experiment and push the boundaries even further, by understanding and applying our knowledge of what happens in the real natural environment.

Think differently. Expand your horizons.

Stay curious. Stay creative. Stay brave. Stay studious...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

"Operating" our aquariums with seasonal and ecological practices.

One of the great joys in creating and working with botanical method aquairums is that we have such a wide variety of natural habitats to take inspiration from. And, as we've discussed here over the years, it's not just types of natural aquatic habitats or specific locales- it's seasons and cycles that we can emulate in our tanks as well.

I find it fascinating to think about how we can emulate the environmental characteristics of aquatic habitats during certain times of the year, such as the "wet" and "dry" seasons...and the idea of actually "operating" your aquarium to spur the environmental changes which take place during these transitions.

Do we create true seasonal variations for our aquariums? I mean, changing up lighting duration, intensity, angles, colors, increasing/decreasing water levels or flow?

With all of the high tech LED lighting systems, electronically controlled pumps; even programmable heaters- we can vary environmental conditions to mimic what occurs in our fishes' natural habitats during seasonal changes as never before. I think it would be very interesting to see what kinds of results we could get with our fishes if we went further into environmental manipulations than we have been able to before.

I mean, sure, hobbyists have been dropping or increasing temps for spawning fishes forever, and you'll see hobbyists play with light durations. Ask any Corydoras breeder. However, these are typically only in the context of defined controlled breeding experiments.

Why not simply research and match the seasonal changes in their habitat and vary them accordingly "just because", and see if you achieve different results?

We've examined the interesting Igapo and Varzea habitats of The Amazon for years now, and how these seasonally-inundated forest floors ebb and flow with aquatic life during various seasons.

And, with the "Urban Igapo", we've "operated" tanks on "wet season/dry season" cycles for a few years now, enjoying very interesting results.

I think it would be pretty amazing to incorporate gradual seasonal changes in our botanical method aquariums, to slowly increase/decrease water levels, temperature, and lighting to mimic the rainy/dry seasonal cycles which affect this habitat.

What secrets could be unlocked?

How would you approach this?

You'd need some real-item or historical weather data from the area which you're attempting to replicate, but that's readily available from multiple sources online. Then, you could literally tell yourself during the planning phases of your next tank that, "This aquarium will be set up to replicate the environmental conditions of the Igarape Panemeo in May"- and just run with it.

What are some of the factors that you'd take into account when planning such a tank? Here are just a few to get you started:

-water temperature

-ph

-water depth

-flow rate

-lighting conditions

-percentage of coverage of aquatic plants (if applicable)

-substrate composition and depth

-leaf litter accumulation

-density of fish population

-diversity of fish population

-food types

...And the list can go on and on and on. The idea being to not just "capture a moment in time" in your aquarium, but to pick up and run with it from there!

Yes, we love the concept of seasonality in our botanical method world- but not just because they create interesting aesthetic effects- but because replicating seasonal changes brings out interesting behaviors and may yield health benefits for our fishes that we may have not previously considered.

The implications of seasonality in both the natural environment- and, I believe- in our aquariums- can be quite profound.

Amazonian seasonality, for example, is marked by river-level fluctuation, also known as "seasonal pulses." The average annual river-level fluctuations in the Amazon Basin can range from approximately 12'-45' /4–15m!!! Scientists know this, because River-water-level data has been collected in some parts of the Brazilian Amazon for more than a century! The larger Amazonian rivers fall into to what is known as a “flood pulse”, and are actually due to relatively predictable tidal surge.

And of course, when the water levels rise, the fish populations are affected in many ways. Rivers overflow into surrounding forests and plains, turning the formerly terrestrial landscape into an aquatic habitat once again.

Besides just knowing the physical environmental impacts on our fishes' habitats, what can we learn from these seasonal inundations?

Well, for one thing, we can observe their impact on the diets of our fishes.

In general, fish/invertebrates, detritus and insects form the most important food resources supporting the fish communities in both wet and dry seasons, but the proportions of invertebrates, fruits, and fish are reduced during the low water season. Individual fish species exhibit diet changes between high water and low water seasons in these areas...an interesting adaptation and possible application for hobbyists?

Well, think about the results from one study of gut-content analysis form some herbivorous Amazonian fishes in both the wet and dry seasons: The consumption of fruits in Mylossoma and Colossoma species (big ass fishes, I know) was significantly less during the low water periods, and their diet was changed, with these materials substituted by plant parts and invertebrates, which were more abundant.

Tropical fishes, in general, change their diets in different seasons in these habitats to take advantage of the resources available to them.

Fruit-eating, as we just discussed, is significantly reduced during the low water period when the fruit sources in the forests are not readily accessible to the fish. During these periods of time, fruit eating fishes ("frugivores") consume more seeds than fruits, and supplement their diets with foods like leaves, detritus, and plankton.

Interestingly, even the known "gazers", like Leporinus, were found to consume a greater proportion of materials like seeds during the low water season.

The availability of different food resources at different times of the year will necessitate adaptability in fishes in order to assure their survival. Mud and algal growth on plants, rocks, submerged trees, etc. is quite abundant in these waters at various times of the year. Mud and detritus are transported via the overflowing rivers into flooded areas, and contribute to the forest leaf litter and other botanical materials, becoming nutrient sources which contribute to the growth of this epiphytic algae.

During the lower water periods, this "organic layer" helps compensate for the shortage of other food sources. And of course, this layer comprises an ecological habitat for a variety of organisms at multiple "trophic levels."

And of course, there's the "allochthonous input"- materials imported into the habitat from outside of it...When the water is at a high period and the forests are inundated, many terrestrial insects fall into the water and are consumed by fishes. In general, insects- both terrestrial and aquatic, support a large community of fishes.

So, it goes without saying that the importance of insects and fruits- which are essentially derived from the flooded forests, are reduced during the dry season when fishes are confined to open water and feed on different materials, as we just discussed.

And in turn, fishes feed on many of these organisms. The guys on the lower end of the food chain- bacterial biofilms, algal mats, and fungal growths, have a disproportionately important role in the food webs in these habitats! In fact, fungi are the key to the food chain in many tropical stream ecosystems. The relatively abundant detritus produced by the leaf litter is a very important part of the tropical stream food web.

Interestingly, some research has suggested that the decomposition of leaf litter in igapo forests is facilitated by terrestrial insects during the "dry phase", and that the periodic flooding of this habitat actually slows down the decomposition of the leaf litter (relatively speaking) because of the periodic elimination of these insects during the inundation.

And, many of the organisms which survive the inundation feed off of the detritus and use the leaf substratum for shelter instead of directly feeding on it, further slowing down the decomposition process.

AsI just touched on, much of the important input of nutrients into these habitats consists of the leaf litter and of the fungi that decompose this litter, so the bulk of the fauna found there is concentrated in accumulations of submerged litter.

And the nutrients that are released into the water as a result of the decomposition of this leaf litter do not "go into solution" in the water, but are tied up throughout in the "food web" comprised of the aquatic organisms which reside in these habitats.

This concept is foundational to our interpretation of the botanical method aquarium.

So I wonder...

Is part of the key to successfully conditioning and breeding some of the fishes found in these habitats altering their diets to mimic the seasonal importance/scarcity of various food items? In other words, feeding more insects at one time of the year, and perhaps allowing fishes to graze on detritus and biocover at other times?

And, you probably already know the answer to this question:

Is the concept of creating a "food producing" aquarium, complete with detritus, natural mud, and an abundance of decomposing botanical materials, a key to creating a more true realistic feeding dynamic, as well as an "aesthetically functional" aquarium?

Well, hell yes!

On a practical level, our botanical method aquariums function much like the habitats which they purport to represent, famously recruit biofilm and fungal growths, which we have discussed ad nasueum here over the years. These are nutritious, natural food sources for most fishes and invertebrates.

And of course, there are the associated microorganisms which feed on the decomposing botanicals and leaves and their resulting detritus.

Having some decomposing leaves, botanicals, and detritus helps foster supplemental food sources. Period.

And you don't need special botanicals, leaves, curated packs of botanicals, additives, or gear from us or anyone to create the stuff! Nature will do it all for you using whatever botanical materials you add to your aquarium!

Apparently, the years of us beating this shit into your head here on "The Tint" and elsewhere are finally striking a chord. There are literally people posting pics of their botanical method aquariums on social media every week with hashtags like #detriusthursday or whatever, preaching the benefits of the stuff that we've reviled as a hobby for a century!

That absolutely cracked me up the first time I saw people posting that. Five years ago, people literally called me an idiot online for telling hobbyists to celebrate the stuff...Now, it's a freaking hashtag. It's some weird shit, I tell you...gratifying to see, but really weird!

Now, we've briefly talked about how decomposing leaf litter and the resulting detritus it produces supports population of "infusoria"- a collective term used to describe minute aquatic creatures such as ciliates, euglenoids, protozoa, unicellular algae and small invertebrates that exist in freshwater ecosystems.

And there is much to explore on this topic. It's no secret, or surprise- to most aquarists who've played with botanicals, that a tank with a healthy leaf litter component is a pretty good place for the rearing of fry of species associated with blackwater environments!

It's been observed by many aquarists, particularly those who breed loricariids, gouramis, bettas, and characins, that the fry have significantly higher survival rates when reared in systems with leaves and other botanical present. This is significant...I'm sure some success from this could be attributed to the population of infusoria, etc. present within the system as the leaves break down.

And the insights gained by seeing first hand how fishes have adapted to the seasonal changes, and have made them part of their life cycle are invaluable to our aquarium practice.

It's an oft-repeated challenge I toss out to you- the adventurers, innovators, and bold practitioners of the aquarium hobby: follow Nature's lead whenever possible, and see where it takes you. Leave no leaf unturned, no piece of wood unstudied...push out the boundaries and blur the lines between Nature and aquarium.

Follow the seasons.

And place the aesthetic component of our botanical method aquarium practice at a lower level of importance than the function.

I'm fairly certain that this idea will make me even less popular with some in the aquarium hobby crowd who feel that the descriptor of "natural" is their exclusive purview, and that aesthetics reign supreme..Hey, I love the look of well-crafted tanks as much as anyone...but let's face it, a truly "natural" aquarium needs to embrace stuff like detritus, mud, decomposing botanical materials, varying water tint and clarity, etc.

Yes, the aesthetics of botanical method tanks might not be everyone's cup of tea, but the possibilities for creating more self-sustaining, ecologically sound microcosms are numerous, and the potential benefits for fishes are many.

It goes back to some of the stuff we've talked about before over the years here, like "pre-stocking"aquariums with lower life forms before adding your fishes- or at least attempting to foster the growth of aquatic insects and crustaceans, encouraging the complete decomposition of leaves and botanical materials, allowing biocover ("aufwuchs") to accumulate on rocks, substrate, and wood within the aquarium, utilization of a refugium, etc.during the startup phases of your tank.

All of these things are worth investigating when we look at them from a "functionality" perspective, and make the "mental shift" to visualize why a real aquatic habitat looks like this, and how its elegance and natural beauty can be every bit as attractive as the super pristine, highly-controlled, artificially laid out "plant-centric" 'scapes that dominate the minds of most aquarists when they hear the words "natural" and "aquarium" together!

Particularly when the "function" provides benefits for our animals that we wouldn't appreciate , or even see- otherwise.

At Tannin, we've pushed rather unconventional hobby viewpoints since our founding in 2015. As an aquarist, I've had these viewpoints on the hobby for decades. A desire to accept the history of our hobby, to understand how "best practices" and techniques came into being, while being tempered by a strong desire to question and look at things a bit differently. To see if maybe there's a different- or perhaps-better-way to accomplish stuff.

Most of my time in the hobby has been occupied by looking at how Nature works, and seeing if there is a way to replicate some of Her processes in the aquarium, despite the aesthetics of the processes involved, or even the results.

As a result, I've learned to appreciate Nature as She is, and have long ago given up much of my "aquarium-trained" sensibilities to "edit" or polish out stuff I see in my aquariums, simply because it doesn't fit the prevailing aesthetic sensibilities of the aquarium hobby. Now, it doesn't mean that I don't care how things look...of course not!

Rather, it means that I've accepted a different aesthetic- one that, for better or worse in some people's minds- more accurately reflects what natural aquatic habitats really look like.

And the idea of replicating the seasonal changes in our aquariums is driven not primarily from aesthetics- but from function.

To sort of put a bit of a bow on this now rather unwieldy discussion about fostering and managing our own versions of seasonal ecological systems in our aquariums, let's just revisit once again how botanical materials accomplish this in our aquariums.

The idea that we are adding these materials not only to influence the aquatic environment in our aquariums, but to provide food and sustenance for a wide variety of organisms, not just our fishes. The fundamental essence of the botanical-method aquarium is that the use of these materials provide the foundation of an ecosystem.

The essence.

Just like they are in Nature.

And the primary process which drives this closed ecosystem is... decomposition.

Decomposition of leaves and botanicals not only imparts the substances contained within them (lignin, organic acids, and tannins, just to name a few) to the water- it serves to nourish bacteria, fungi, and other microorganisms and crustaceans, facilitating basic "food web" within the botanical-method aquarium- if we allow it to!

Decomposition of plant matter-leaves and botanicals- occurs in several stages.

It starts with leaching -soluble carbon compounds are liberated during this process. Another early process is physical breakup or fragmentation of the plant material into smaller pieces, which have greater surface area for colonization by microbes.

And of course, the ultimate "state" to which leaves and other botanical materials "evolve" to is our old friend...detritus.

And of course, that very word- as we've mentioned many times here, including just minutes ago- has frightened and motivated many hobbyists over the years into removing as much of the stuff as possible from their aquariums whenever and wherever it appears.

Siphoning detritus is a sort of "thing" that we are asked about near constantly. This makes perfect sense, of course, because our aquariums- by virtue of the materials they utilize- produce substantial amounts of this stuff.

Now, the idea of "detritus" takes on different meanings in our botanical-method aquariums...Our "aquarium definition" of "detritus" is typically agreed to be dead particulate matter, including fecal material, dead organisms, mucous, etc.

And bacteria and other microorganisms will colonize this stuff and decompose/remineralize it, essentially "completing" the cycle.

And, despite their impermanence, these materials function as diverse harbors of life, ranging from fungal and biofilm mats, to algae, to micro crustaceans and even epiphytic plants. Decomposing leaves, seed pods, and tree branches make up the substrate for a complex web of life which helps the fishes that we're so fascinated by flourish throughout the various seasons.

And, if you look at them objectively and carefully, these assemblages-and the processes which form them- are beautiful. We would be well-advised to let them do their work unmolested.

On a purely practical level, these processes accomplish the most in our aquariums if we let Nature do her work without excessive intervention.

An example? How about our approach towards preparing natural materials for use in our tanks:

After decades of playing with botanical method aquariums, I'm thinking that we should do less and less preparation of certain botanical materials-specifically, wood- to encourage a slower breakdown and colonization by beneficial bacteria and fungal growths.

The "rap" on wood has always been that it gives off a lot of tint-producing tannins, much to the collective freak-out of non-botanical-method aquarium fans. However, to us, all those extra tannins are not much of an issue, right? Weigh down the wood, and let it "cure" in situ before adding your fishes!

And then there is the whole concept of getting fishes into the tank as quickly as possible.

Like, why?

We should slow our roll.

I've written and spoken about this idea before, as no doubt many of you have: Adding botanical materials to your tank, and "pre-colonizing"with beneficial life forms BEFORE you ever think of adding fishes. A way to sort of get the system "broken in", with a functioning little "food web" and some natural nutrient export processes in place.

A chance for the life forms that would otherwise likely fall prey to the fishes to get a "foothold" and multiply, to help create a sustainable population of self-generating prey items for your fishes.

And that's a fundamental thing for us "recruiting" and nurturing the community of organisms which support our aquariums. The whole foundation of the botanical-method aquarium is the very materials- botanicals, soils, and wood- which comprise the "infrastructure" of our aquariums.The botanicals create a physical and chemical environment which supports these life forms, allowing them to flourish and support the life forms above them.

From there, we can "operate" our aquariums in any manner of ways.

Nature provides some really incredible inspiration for this stuff, doesn't it? Marshland and flooded plains and forests along rivers are like the "poster children" for seasonal change in the tropics.

Flood pulses in these habitats easily enable large-scale "transfers" of nutrients and food items between the terrestrial and aquatic environment. This is of huge importance to the ecosystem. As we've touched on before, aquatic food webs in the Amazon area (and in other tropical ecosystems) are very strongly influenced by the input of terrestrial materials, and this is really an important point for those of us interested in creating more natural aquatic displays and microcosms for the fishes we wish to keep.

Because the aquatic ecology is driven by the surrounding terrestrial habitats seasonally, the impact of leaves which fall into the aquatic habitats is very important.

What makes leaves fall off the trees in the first place? Well, it's simple- er, rather complex...but I suppose it's simple, too. Essentially, the tree "commands" leaves to fall off the tree, by creating specialized cells which appear where the leaf stem of the leaves meet the branches. Known as "abscission" cells. for word junkies, they actually have the same Latin root as the word "scissors", which, of course, implies that these cells are designed to make a cut!

And, in the tropical species of trees, the leaf drop is important to the surrounding environment. The nutrients are typically bound up in the leaves, so a regular release of leaves by the trees helps replenish the minerals and nutrients which are typically depleted from eons of leaching into the surrounding forests.

And the rapid nutrient depletion, by the way, is why it's not healthy to burn tropical forests- the release of nutrients as a result of fire is so rapid, that the habitat cannot process it, and in essence, the nutrients are lost forever.

Now, interestingly enough, most tropical forest trees are classified as "evergreens", and don't have a specific seasonal leaf drop like the "deciduous" trees than many of us are more familiar with do...Rather, they replace their leaves gradually throughout the year as the leaves age and subsequently fall off the trees.

The implication here?

There is a more-or-less continuous "supply" of leaves falling off into the jungles and waterways in these habitats throughout the year, which is why you'll see leaves at varying stages of decomposition in tropical streams. It's also why leaf litter banks may be almost "permanent" structures within some of these bodies of water!

Here's an easy "seasonal" experiment for you to try:

Manage and replicate this in the aquarium by adding leaves at different times of the year..increasing the quantities in some months and backing off during others. It's a relatively simple process with possible profound implications for aquariums.

And it makes me wonder...

What if we stopped replacing leaves and even lowered water levels or decreased water exchanges in our tanks to correspond to, for example, the Amazonian dry season (June to December)? What would it do?

If you consider that many fishes tend to spawn in the "dry" season, concentrating in the shallow waters, could this have implications for breeding or growth in fishes?

I think so.

Just a few easy ideas...each with a promise and a potential to change the way we manage botanical method aquariums, and impact the way we look at so-called "natural" aquariums in the first place!

And, with all of the research data from the wild habitats of our fishes available easier than ever before, the time is right to start these bold experiments!

Obviously, there is still much to learn, and of course, the bigger question that many will ask, "What is the advantage?"

Well, that's all part of the fun...we can play a hunch, but we won't know for certain until we really delve into this stuff!

Who's in?

Stay thoughtful. Stay curious. Stay engaged. Stay innovative. Stay diligent...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

As the seasons pass...

Every Corydoras breeder knows something that we all should know:

Environmental manipulations create unique opportunities to facilitate behavioral changes in our fishes.

It's hardly an earth-shattering idea in the aquarium hobby, but I think that the concept of "seasonal" environmental manipulation deserves some additional consideration.

It's been known for decades that environmental changes to the aquatic environment caused by weather (particularly "wet" or "dry" seasons/events) can stimulate fishes into spawning.

As a fish geek keen on not only replicating the look of our fishes' wild habitats, but as much of the "function" as possible, I can't help myself but to ponder the possibilities for greater success by manipulating the aquarium environment to simulate what happens in the wild.

Probably the group of aquarists who has had the most experience and success at incorporating such environmental manipulations into their breeding procedures is Corydoras catfish enthusiasts!

Many hobbyists who have bred Corydoras utilize the old trick of a 20%-30% water exchange with water that is up to 10° F cooler (6.5° C) than the aquarium water is normally maintained at. It seems almost like one of those, "Are you &^%$#@ crazy- a sudden lowering of temperature?"

However, it works, and you almost never hear of any fishes being lost as a result of such manipulations.

I often wondered what the rationale behind such a change was. My understanding is that it essentially is meant to mimic a rainstorm, in which an influx of cooler water is a feature. Makes sense. Weather conditions are such an important part of the life cycle of our fishes.

Still others attempt to simulate a "dry spell" by allowing the water quality to "degrade" somewhat (what exactly that means is open to interpretation!), while simultaneously increasing the aquarium temperature a degree or two. This is followed by a water exchange with softer water (ie; pure RO/DI), and resetting the tank temp to the tank's normal range of parameters.

The "variation" I have heard is to do the above procedure, accompanied by an increase in current via a filter return or powerhead, which simulates the increased water volume/flow brought on by the influx of "rain."

Clever.

Many breeders will fast their fishes a few days, followed by a big binge of food after the temperature drop, apparently simulating the increased amount of food in the native waters when rains come.

Still other hobbyists will reduce the pH of their aquarium water to stimulate breeding. And I suppose the rationale behind this is once again to simulate an influx of water from rain or other external sources...

Weather, once again.

And another trick I hear from my Cory breeder friends from time to time is the idea of tossing in a few alder cones into the tank/vessel where their breeders' eggs are incubating.

This decades-old practice is justified by the assertion that the alder cones possess some type of anti-fungal properties...not entirely off base with some of the scientific research we've found about the allegedly anti-microbial/antifungal properties of catappa leaves and such...

And of course, I hear/read of recommendations to use the aforementioned catappa leaves, oak leaves, and Magnolia leaves for just this purpose...

Interesting.

Okay, cool.

Not really earth-shattering; however, it got me thinking about the whole idea of environmental manipulations as part of the routine "operation" of our botanical-mehtod aquariums.....Should we create true seasonal variations for our aquariums as part of our regular practice- not just when trying to spawn fishes? I mean, changing up lighting duration, intensity, angles, colors, increasing/decreasing water levels or flow?

With all of the high tech LED lighting systems, electronically controlled pumps; even advanced heaters- we can vary environmental conditions to mimic what occurs in our fishes' natural habitats during seasonal changes as never before. I think it would be very interesting to see what kinds of results we could get with our fishes if we went further into seasonal environmental manipulations than we have been able to before.

And of course, if we look at the natural habitats where many of our fishes originate, we see these seasonal changes having huge impact on the aquatic ecosystems. In The Amazon, for example, the high water season runs December through April.

And during the flooding season, the average temperature is 86 degrees F, around 12 degrees cooler than the dry season. And during the wet season, the streams and rivers can be between 6-7 meters higher on the average than they are during the dry season!

And of course, there are more fruits, flowers, and insects during this time of year- important food items for many species of fishes.

And the dry season? Well, that obviously means lower water levels, higher temperatures, and abundance of fishes, most engaging in spawning activity.

Mud and algal growth on plants, rocks, submerged trees, etc. is quite abundant in these waters at various times of the year. Mud and detritus are transported via the overflowing rivers into flooded areas, and contribute to the forest leaf litter and other botanical materials, coming nutrient sources which contribute to the growth of this epiphytic algae.

During the lower water periods, this "organic layer" helps compensate for the shortage of other food sources. When the water is at a high period and the forests are inundated, many terrestrial insects fall into the water and are consumed by fishes. In general, insects- both terrestrial and aquatic, support a large community of fishes.

So, it goes without saying that the importance of insects and fruits- which are essentially derived from the flooded forests, are reduced during the dry season when fishes are confined to open water and feed on different materials.

So I wonder...is part of the key to successfully conditioning and breeding some of the fishes found in these habitats altering their diets to mimic the seasonal importance/scarcity of various food items? In other words, feeding more insects at one time of the year, and perhaps allowing fishes to graze on detritus and biocover at other times?

And then, there are those fishes whose life cycle is intimately tied into the seasonal changes.

The killifishes.

Any annual or semi-annual killifish species enthusiast will tell you a dozen ways to dry-incubate eggs; again, a beautiful simulation of what happens in Nature...So much of the idea can be applicable to other areas of aquarium practice, right?

Yeah... I think so.

It's pretty clear that factors such as the air, water and even soil temperatures, atmospheric humidity, the water level, the local winds as well as climatic variables have profound influence on the life cycle and reproductive behavior on the fishes that reside in these dynamic tropical environments!

In my "Urban Igapo" experiments, we get to see a little microcosm of this whole seasonal process and the influences of "weather."

And of course, all of this ties into the intimate relationship between land and water, doesn't it?

There's been a fair amount of research and speculation by both scientists and hobbyists about the processes which occur when terrestrial materials like leaves and botanical items enter aquatic environments, and most of it is based upon field observations.

As hobbyists, we have a unique opportunity to observe firsthand the impact and affects of this material in our own aquariums! I love this aspect of our "practice", as it creates really interesting possibilities to embrace and create more naturally-functioning systems, while possibly even "validating" the field work done by scientists!

And of course, there are a lot of interesting bits of information that we can interpret from Nature when planning, creating, and operating our aquariums.

It goes without saying that there are implications for both the biology and chemistry of the aquatic habitats when leaves and other botanical materials enter them. Many of these are things that we as hobbyists observe every day in our aquariums!

Example?

A lab study I came upon found out that, when leaves are saturated in water, biofilm is at it's peak when other nutrients (i.e.; nitrate, phosphate, etc.) tested at their lowest limits. This is interesting to me, because it seems that, in our botanical method aquariums, biofilms tend to occur early on, when one would assume that these compounds are at their highest concentrations, right? And biofilms are essentially the byproduct of bacterial colonization, meaning that there must be a lot of "food" for the bacteria at some point if there is a lot of biofilm, right?

More questions...

Does this imply that the biofilms arrive on the scene and peak out really quickly; an indication that there is actually less nutrient in the water? Is the nutrient bound up in the biofilms? And when our fishes and other animals consume them, does this provide a significant source of sustenance for them?

Hmm...?

Oh, and here is another interesting observation:

When leaves fall into streams, field studies have shown that their nitrogen content typically will increase. Why is this important? Scientists see this as evidence of microbial colonization, which is correlated by a measured increase in oxygen consumption. This is interesting to me, because the rare "disasters" that we see in our tanks (when we do see them, of course, which fortunately isn't very often at all)- are usually caused by the hobbyist adding a really large quantity of leaves at once, resulting in the fishes gasping at the surface- a sign of...oxygen depletion?

Makes sense, right?

These are interesting clues about the process of decomposition of leaves when they enter into our aquatic ecosystems. They have implications for our use of botanicals and the way we manage our aquariums. I think that the simple fact that pH and oxygen tend to go down quickly when leaves are initially submerged in pure water during lab tests gives us an idea as to what to expect.

A lot of the initial environmental changes will happen rather rapidly, and then stabilize over time. Which of course, leads me to conclude that the development of sufficient populations of organisms to process the incoming botanical load is a critical part of the establishment of our botanical-method aquariums.

Fungal populations are as important in the process of breaking down leaves and botanical materials in water as are higher organisms, like insects and crustaceans, which function as "shredders." The “shredders” – the animals which feed upon the materials that fall into the streams, process this stuff into what scientists call “fine particulate organic matter.”

And that's where fungi and other microorganisms make use of the leaves and materials, processing them into fine sediments. Allochthonous material can also include dissolved organic matter (DOM) carried into streams and re-distributed by water movement.

And the process happens surprisingly quickly.

In studies carried out in tropical rainforests in Venezuela, decomposition rates were really fast, with 50% of leaf mass lost in less than 10 days! Interesting, but is it tremendously surprising to us as botanical-method aquarium enthusiasts? I mean, we see leaves begin to soften and break down in a matter of a couple of weeks- with complete breakdown happening typically in a month or so for many leaves.

And biofilms, fungi, and algae are still found in our aquariums in significant quantities throughout the process.

So, what's this all mean? What are the implications for aquariums?

I think it means that we need to continue to foster the biological diversity of animals in our aquariums- embracing life at all levels- from bacteria to fungi to crustaceans to worms, and ultimately, our fishes...All forming the basis of a closed ecosystem, and perhaps a "food web" of sorts for our little aquatic microcosms. It's a very interesting concept- a fascinating field for research for aquarists, and we all have the opportunity to participate in this on a most intimate level by simply observing what's happening in our aquariums every day!

We've talked about this very topic many times right here over the years, haven't we? I can't let it go.

Bioversity is interesting enough, but when you factor in seasonal changes and cycles, it becomes an almost "foundational" component for a new way of running our botanical-style aquariums.

Consider this:

The wet season in The Amazon runs from November to June. And it rains almost every day.

And what's really interesting is that the surrounding Amazon rain forest is estimated by some scientists to create as much as 50% of its own precipitation! It does this via the humidity present in the forest itself, from the water vapor present on plant leaves- which contributes to the formation of rain clouds.

Yeah, trees in the Amazon release enough moisture through photosynthesis to create low-level clouds and literally generate rain, according to a recent study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (U.S.)!

That's crazy.

But it makes a lot of sense, right?

Okay, that's a cool "cocktail party sound bite" and all, but what happens to the (aquatic) environment in which our fishes live in when it rains?

Well, for one thing, rain performs the dual function of diluting organics, while transporting more nutrient and materials across the ecosystem. What happens in many of the regions of Amazonia - and likewise, in many tropical locales worldwide-is the evolution of some of our most compelling environmental niches...

We've literally scratched the surface, and the opportunity to apply what we know about the climates and seasonal changes which occur where our fishes originate, and to incorporate, on a broader scale, the practices which our Corydoras-enthusiast friends employ on all sorts of fishes!

So much to learn, experiment with, and execute on.

Stay fascinated. Stay intrigued. Stay observant. Stay creative. Stay astute...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

For the love of weird substrates...

One of the "cornerstones" of our botanical-method aquarium practice is the use of substrate. Specifically, substrate materials which can influence- or make it easier to influence- water chemistry in the aquarium, as well as to help foster a "microbiome" of small organisms which will provide ecological diversity for the system.

Substrates, IMHO, are one of the most often-overlooked components of the aquarium. We tend to just add a bag of "_____________" to our tanks and move on to the "more exciting" stuff like rocks and "designer" wood. It's true! Other than planted aquarium enthusiasts, the vast majority of hobbyists seem to have little more than a passing interest in creating and managing a specialized substrate or associated ecology.

A real pity, especially for those of us who are interested in botanical-method aquariums, which replicate natural aquatic habitats where soils and geology play a HUGE role in influencing the environmental parameters of these ecosystems. And in the hobby, we've largely overlooked the benefits and possibilities which specialized substrates can offer.

So I started to experiment with materials to recreate some of the characteristics of wild aquatic habitats which fascinated me. And an obsession was born.

I started playing with substrates mainly because I couldn't find exactly what I was looking for on the market. This is not some indictment of the major substrate manufacturers out there...I LOVE almost all of them and use and happily recommend ones that I like. I'm obsessed with substrates. I think that the companies which produce them are among the coolest of the cool aquatics industry brands. If I wasn't doing this botanical thing with Tannin, I'd probably have started a company that specializes in substrates for aquariums. Seriously.

And the fact is, the major manufacturers need to market products that more than like 8 people are interested in. It's unreasonable to think that they'd devote precious resources to creating a product that would be geared to such a tiny target.

And of course, being one of those 8 people who are geeked-out about weird substrates, I decided that I'd "scratch my own itch" (as we did with the botanical thing..) and formulate and create some of my own. Thus, the NatureBase product line was born!

I realized that the specialized world which we operate in embraces some different ideas, unusual aesthetics, and is fascinated by the function of the environments we strive to replicate. These are important distinctions between what we are doing with substrates at Tannin, and what the rest of the aquarium hobby is doing.

Our NatureBase line is not intended to supersede or completely replace the more commonly available products out there as your "standard" aquarium substrate, because: a) they're more expensive, b) they're not specifically "aesthetic enhancements", c) they are not intended to be planted aquarium substrates, and d) because of their composition, they'll add some turbidity and tint to the aquarium water, at least initially (not everyone could handle THAT!)

So, right there, those factors have significantly segmented our target market...I mean, we're not trying to be the aquarium world's "standard substrate", they weren't formatted to grow aquatic plants, we're not marketing them just for the cool looks, and we can't emphasize enough that they will make your water a bit turbid when first submerged. If you have fishes which dig, or which like to "work" the substrate, you may see a near-continuous turbidity in your aquarium!

Oh, joy.

Those factors alone will take us out of contention for large segments of the market!

This is important to grasp.

I mean, these substrates are intended to be used in more natural, botanical-style/biotope-inspired aquariums. Our first two releases, "Igapo" and "Varzea", are specific to the creation of a type of "cyclical" terrestrial/aquatic feature. They do exactly what I wanted them to do, and they were specifically intended for use in specialized set ups, like the "Urban Igapo" idea we've been talking about for a long time here, as well as brackish water mangrove environments, etc.

Let's touch on the "aesthetic" part for a minute.

Most of our NatureBase substrates have a significant percentage of clays and sediments in their formulations. These materials have typically been something that aquarists have avoided, because they will cloud the water for a while, and often impart a bit of color. We also have some botanical components in a few of our substrates, because they are intended to be "terrestrial" substrates for a while before being flooded...and when this stuff is first wetted, some of it will float.

And that means that you're going to have to net it out, or let your filter take it out. You simply won't have that "issue" with your typical bag of aquarium sand!

Shit, you're probably just frothing right now, waiting to cloud and dirty up your aquariums with this stuff, huh?

No?

I can't for the life of me figure out why not? ;)

Remember, some of these substrates were formulated for a very specific purpose: To replicate the terrestrial soils which are seasonally inundated in the wild. As such, these products simply won't look or act like your typical aquarium substrate materials!

Scared off completely yet? I hope not.

Why include sediments and clays in our mixes?

Well, for one thing, sediments are an integral part of the natural substrates in the habitats from which our fishes come. So, they're integral to our line. In fact, I suppose you'd best classify NatureBase products as "sedimented substrates."

Think about this: Many of our favorite habitats are forest floors and meadows which undergo periodic flooding cycles in the Amazon, which results in the creation of aquatic habitats for a remarkable diversity of fish species.

Depending on the type of water that flows from the surrounding rivers, the characteristics of the flooded areas may vary. Another important impact is the geology of the substrates over which the rivers and streams pass. This results in differences in the physical-chemical properties of the water.

In the Amazon, areas flooded by rivers of black or clear waters, with acid pH and low sediment load, in addition to being nutritionally poor, are called “igapó."

The flooding often lasts for several weeks or even several months, and the plants and trees need special biochemical adaptations to be able to survive the lack of oxygen around their roots. We've talked about this a lot here over the years.

Forest floor soils in tropical areas are known by soil geologists as "oxisols", and have varying amounts of clay, sediments, minerals like quartz and silica, and various types of organic matter. So it makes sense that when flooded, these "ingredients" will have significant impact on the aquatic environment. This "recipe" is not only compositionally different than typical "off-the-shelf" aquarium sands and substrates- it looks and functions differently, too.

YOU DON'T RINSE THEM BEFORE USE!

You CAN wet them right away; you don't have to do a "wet/dry season" igapo-style tank with them. However, you should be ready for some cloudy water for a week or more! And again, if you have fishes which like to "work" the substrate, it will be a near-constant thing, the degree to which it will be is based on the habits of the fishes you keep.

And that's where a lot of people will metaphorically "leave the room."Turbid, darker water is a guaranteed "freak out" for a super-high high percentage of aquarists.

So, yeah, you'll have to make a mental shift to appreciate a different look and function.

And many hobbyists simply can't handle that. I've been extremely up front with this stuff since the introduction of these substrates, to ward off the, "I added NatureBase to my tank and it looks like a cloudy mess! This stuff is SHIT!" type of emails that inevitably come when people don't read up first before they purchase the stuff. (And trust me- the fact that you're even reading this blog, or listening to this podcast puts you in the tiniest minority of aquarium hobbyists!)

Let's talk a bit about how to "live" with these substrates.

There are a lot of different ways to use these substrates in all sorts of tanks. I mean, if you want some of the benefits and want to geek out and experiment with them, you can use a "sand cap" of whatever conventional substrate you prefer on top, and likely limit the turbidity somewhat, much like the practice of aquarists who employ "dirted" substrates do.

Oh, and the plant thing...

We're asked a LOT if these substrates can grow aquatic plants. Now, although they were intended to facilitate the growth of terrestrial plants, like grasses, the fact is, both our customers and ourselves have seen pretty damn good plant growth in tanks using this stuff!

Our Igapo and Varzea substrates mimic sandy acidic soils that have a low nutrient content. And, as you know, the color and acidity of the floodwater is due to the acidic organic humic substances (tannins) that dissolve into it. The acidity from the water translates into acidic soils, which makes sense, right?

Now, I admit, I am NOT a geologist, and I'm not expert in soil science. I know enough to realize that, in order to replicate the types of habitats I am fascinated with, it required different materials. If you ask me, "Will this fish do well with this materials?" or, "Can I grow "Cryptocoryne in this?", or "Does this make a good substrate for shrimp tanks?" I likely won't have a perfect answer. Sorry.

Periodically, plant enthusiasts will ask me about the "cation exchange capacity" of our substrate. Cation Exchange Capacity (CEC) is the ability of a material to absorb positively-charged nutrient ions. This means the substrate will hold nutrients and make them available for the plant roots, and therefore, plant growth. CEC measures the amount of nutrients, more specifically, positivity changed ions, which a substrate can hold onto/store for future use by aquatic plants.

Thus, a "high CEC" is important to many aquatic plant enthusiasts in their work. While it means that the substrate will hold nutrients and make them available for the plant roots. it doesn't indicate the amount of nutrients the substrate contains.

For reference, scientists measure cation exchange capacity (CEC) in milliequivalents per 100 grams ( meq/100g).

To really get "down and dirty" to analyze substrates scientifically, CEC determinations are often done by a process called "Method 9081A of EPA SW- 846." What the....? CEC extractions are often also analyzed on ICP-OES systems. A rather difficult and pretty expensive process, with equipment and methods that are not something casual hobbyists can easily replicate!

As you might suspect, CEC varies widely among different materials. Sand, for instance, has a CEC less than 1 meq/100 g. Clays tend to be over 30 meq/100 g. Stuff like natural zeolites are around 100 meq/100g! Soils and humus may have CEC up to 250 meq/100g- that's pretty serious!

What nutrients are we talking about here? The most common ones which come into play in the context of CEC are iron, potassium, calcium and magnesium. So, if you're into aquatic plants, high CEC is a good thing!

Of course, this is where the questions arise around the substrates we play with.

It makes sense, right?

Our "Nature Base" substrates do contain materials such as clays and silts, which could arguably be considered "higher CEC" materials, because they're really fine- and because higher surface area generally results in a higher CEC. The more surface area there is, the more potential bonding sites there are for the exchange to take place. Alas, nothing is ever exactly what we hope it should be in this hobby, and clays are often not all that high in their CEC "ratings."

Now, the "Nature Base" substrates are what we like to call “sedimented substrates”, because they are not just sand, or pellets of fired clays, etc. They are a mix of materials, and DO also have some terrestrial soils in the mix, too, which are also likely higher in CEC. And no, we haven't done CEC testing with our substrates...It's likely that in the future, some enthusiastic and curious scientist/hobbyist might just do that, of course!

Promising, from a CEC standpoint, I suppose!

However, again, I must emphasize that they were really created to replicate the substrate materials found in the igapo and varzea habitats of South America, and the overall habitat- more "holistically conceived"-not specifically for plant growth. And, in terrestrial environments like the seasonally-inundated igapo and varzea, nutrients are often lost to volatilization, leaching, erosion, and runoff..

So, it's important for me to make it clear again that these substrates are more representative of a terrestrial soil. Interestingly, the decomposition of detritus and leaves and such in our botanical-method aquariums and "Urban Igapo" displays is likely an even larger source of “stored” nutrients than the CEC of the substrate itself, IMHO. Thus, they will provide a home for beneficial bacteria- breaking down organics and helping to make them more available for plant growth.

Perhaps that's why aquatic plants grow so well in botanical-method aquariums?

Yeah, the stuff DOES grow aquatic and riparian plants and grasses quite well, in our experience! Yet, again- I would not refer to them specifically as "aquatic plant substrates." They're not being released to challenge or replace the well-established aquatic plant soils out there. They're not even intended to be compared to them!

Remember, our "Igapo" and "Varzea" substrates are intended to start out life as "terrestrial" materials, gradually being inundated as we bring on the "wet season." And because of the clay and sediment content of these substrates, you'll see some turbidity or cloudiness in the water. It won't immediately be crystal-clear- just like in Nature. That won't excite a typically planted aquarium lover, for sure.

I can't stress it often enough: With our emphasis on the "wholistic" application of our substrate, our focus is on the "big picture" of these closed aquatic ecosystems.

I'll be the first to tell you that, while I have experimented with many species of plants, inverts, and fishes with these substrates, I can't tell you that every single fish or plant will like them. You'll simply have to experiment!

Well, shit- that's not something that you typically hear an aquarium hobby brand tell you to do with their products every day, huh? Like, I'm not going to make all sorts of generalized statements about everything I think that these products can do. It would be very unhelpful. I'd rather focus on how they perform in the types of systems in which they were intended to work in, and what the possible downsides could be!

The whole point here is that these substrates are perfect for a whole range of applications. They're not "the greatest substrates ever made!" or anything like that. However, they are super useful for replicating the soils of some of our favorite aquatic habitats.

And for doing some of those geeky experiments that we love so much. So, that pretty much covers the "sedimented" substrate thing for now. Let's talk about "alternative" substrates for a bit...

PT.2 : "ALTERNATIVE SUBSTRATES" AND THE "DANGERS" FROM WITHIN?

In my experience, and in the reported experiences from hundreds of aquarists who play with botanical materials breaking down in and on their aquariums' substrates, undetectable nitrate and phosphate levels are typical for this kind of system. When combined with good overall husbandry, it makes for incredibly stable systems.

I've been thinking through further refinements of the "deep botanical bed"/sand substrate relationship. I've been spending a lot of time researching natural aquatic systems and contemplating how we can translate some of this stuff into our closed system aquaria.

Now, I realize, when contemplating really deep aggregations of substrate materials in the aquarium, that we're dealing with closed systems, and the dynamics which affect them are way different than those in Nature, for the most part.

And I realize that experimenting with these unusual approaches to substrates requires not only a sense of adventure, a direction, and some discipline- but a willingness to accept and deal with an entirely different aesthetic than what we know and love. And this also includes pushing into areas and ideas which might make us uncomfortable, not just for the way they look, but for what we are told might be possible risks.

One of the things that many hobbyists ponder when we contemplate creating deep, botanical-heavy substrates, consisting of leaves, sand, and other botanical materials is the possible buildup of hydrogen sulfide, CO2, and other undesirable compounds within the substrate.

Well, it does make sense that if you have a large amount of decomposing material in an aquarium, that some of these compounds are going to accumulate in heavily-"active" substrates. Now, the big "bogeyman" that we all seem to zero in on in our "sum of all fears" scenarios is hydrogen sulfide, which results from bacterial breakdown of organic matter in the total absence of oxygen.

Let's think about this for just a second.

In a botanical bed with materials placed on the substrate, or loosely mixed into the top layers, will it all "pack down" enough to the point where there is a complete lack of oxygen and we develop a significant amount of this reviled compound in our tanks? I just don't think so. I think that we're more likely to see some oxygen in this layer of materials, and I can't help but speculate- and yeah, it IS just speculation- that actual de-nitirifcation (nitrate reduction), which lowers nitrates while producing free nitrogen, might actually be able to occur in a "(deep) botanical" bed.

And it's certainly possible to have denitrification without dangerous hydrogen sulfide levels. As long as even very small amounts of oxygen and nitrates can penetrate into the substrate, this will not become an issue for most systems. I personally have yet to see a botanical-method aquarium where the material has become so "compacted" as to appear to have no circulation whatsoever within the botanical layer.

Now, sure, I'm not a scientist, and I base this on the management of, and close visual inspection of numerous aquariums, as well as the basic chemical tests I've run on my systems under a variety of circumstances. As one who has made it a point to keep my botanical-method aquariums in operation for very extended time frames, I think this is significant. The "bad" side effects we're talking about should manifest over these longer time frames...and they just haven't.

And then there's the question of nitrate.

Although not the terror that ammonia and nitrite are known to be, nitrate accumulation is something a lot of hobbyists are concerned with. As nitrate accumulates, fish will eventually suffer some health issues. Ideally, we strive to keep our nitrate levels no higher than 5-10ppm in our aquariums.

As a reef aquarist, I was always of the "...keep it as close to zero as possible." mindset, until I realized that corals just grow better with the presence of some nitrate! This was especially evident in my large scale coral grow-out raceways.

It seems that 'zero" nitrate is not always the most realistic or achievable target in a heavily-botanical-laden aquarium, although I routinely see undetectable nitrate reading in my tanks. You have a bit more "wiggle room", IMHO, however, before concern over fish health is a factor. Now, when you start creeping towards 50ppm, you're getting closer towards a number that should alert you.

It's not a big "stretch" from 50ppm to more potentially detrimental readings of 75ppm and higher...

And then you get towards the range where health issues could manifest themselves in your fishes. Now, many fishes will not show any symptoms of nitrate poisoning until the nitrate level reaches 100 ppm or more. However, studies have shown that long-term exposure to moderate concentrations of nitrate stresses fishes, making them more susceptible to disease, affecting their growth rates, and inhibiting spawning in many species.

At those really high nitrate levels, fishes will become noticeably lethargic, and may have other health issues that are obvious upon visual inspection, such as open sores or reddish patches on their skin. And then, you'd have those "mysterious deaths" and the sudden death (essentially from shock) of newly-added fishes to the aquarium, because they're not acclimated to the higher nitrate concentrations.

Okay, that's scary stuff. However, high nitrate concentrations are not only manageable- they're something that's completely avoidable in our aquairums.

Quite honestly, even in the most heavily-botanical-laden systems I've played with, I have personally never seen a higher nitrate reading than around 5ppm. Often, as I mentioned above, they're undetectibIe on hobby-level test kits. I attribute this to common sense stuff: Good quality source water (RO/DI), careful stocking, feeding, good circulation, not disturbing the substrate, and consistent basic aquarium husbandry practices (water exchanges, filter maintenance, etc.).

Now, that's just me.

I'm no scientist, certainly not a chemist, but I have a basic understanding of maintaining a healthy nitrogen cycle in the aquarium. And I am habitual-perhaps even obsessive- about consistent maintenance. Water exchanges are not a "when I get around to it" thing in my aquarium management "playbook"- they're "baked in" to my practice.

So yeah, although nitrate is something to be aware of in botanical-method aquariums, it's simply not an ominous cloud hanging over our success.

Relatively shallow sand or substrate beds seem to be optimal for denitrification, and many of us employ them for the aesthetics as well. Light "stirring" of the top layers, if you're concerned about any potential "dead spots" is something that is permissible, IMHO. Any debris stirred up can easily be removed mechanically by filtration, as mentioned above.

But that's it.

Of course, as we already discussed, you don't have to go crazy siphoning the shit (literally!) out of your sand every week, essentially decimating populations of beneficial microscopic infauna -or interfering with their function- in the process.

What I am starting to feel more and more confident about is postulating that some form of denitrification occurs in a system with a layer of leaves and botanicals as a major component of the tank.

Now, I know, I have little rigorous scientific information to back up my theory, other than anecdotal observations and even some assumptions. However, there is always an example to look at- Nature.

Of course, Nature and aquariums differ, one being a closed system and the other being "open." However, they both are beholden to the same laws, aren't they? And I believe that the function of the captive leaf litter bed and the wild litter beds are remarkably similar to a great extent.

The thing that fascinates me is that, in Nature, leaf litter beds perform a similar function; that is, fostering biodiversity, nutrient export, and yes- denitrification. Let's take a little look at a some information I gleaned from the study of a natural leaf litter bed for some insights.

In a slow-flowing wild Amazonian stream with a very deep leaf litter bed, observations were made which are of some interest to us. First off, oxygen saturation was 6.7 3 mg/L (about 85% of saturation), conductivity was 13.8 microsemions, and pH was 3.5.

Some of these parameters (specifically the very low pH) are likely difficult to obtain and maintain in the aquarium, but the interesting thing is that these parameters were stable throughout a months-long investigation.

Oxygen saturation was surpassingly low, given the fact that there was some water movement and turbulence when the study was conducted. The researchers postulated that the reduction in oxygen saturation presumably reflects respiratory consumption by the organisms residing in the litter, as well as low photosynthetic generation (which makes sense, because there is no real algae or plant growth in the litter beds).

And of course, such numbers are consistent with the presence of a lot of life in the litter beds.