- Continue Shopping

- Your Cart is Empty

The mystique of the "salty cichlid", the Orange Chromide

No brackish water aquarium is complete without brackish-water fishes...And traditionally, that has been a bit of a challenge, in terms of finding some "different" fishes than we've previously associated with brackish aquariums. I think that this will continue to be a bit of a challenge, because some of the fishes that we want are still elusive in the hobby.

New brackish-water fishes will become more readily available when the market demand is there. In the mean time, we can focus on some of the cool fishes from these habitats which are currently available to us.

And there are a few!

They can be hard to find; however, I think the biggest challenge facing those of us who love brackish water aquariums is trying to separate aquarium "fact" from scientific fact! This is pretty fun to do, actually.

However, one of the things I've found is that you need to go beyond "what the hobby articles say" and look into actual information from scientific sources about the types of habitats our target fishes actually come from. There is still a surprisingly large amount of misinformation about there concerning fishes long thought to be "brackish", when the reality is that they are often found predominantly in non-brackish habitats, with perhaps only isolated populations of them being brackish fishes.

Like many hobbyists who play with brackish water tanks, I've found over the years that it's mighty tricky to source genuine brackish water fishes. Through lots of follow up and a bit of luck, I have managed to secure fishes from these types of habitats from time to time, which is, of course, paramount if you're trying to recreate one of these habitats in your aquarium!

As most of you know, I'm no huge cichlid fanatic, but there are some which have found their way into my heart over the decades. One of these is a genuine hobby legend, which just happens to be one of my fave all-time fishes: The venerable "Orange Chromide", Pseudetroplus maculatus - a cichlid with a very weird popular name.

Despite being a cichlid (😆), the Orange Chromide is a relatively easy-going fish that tops out at about 4" in size, which is a huge plus in my book. And, being one of the very few species of cichlids which comes from India, it's even more interesting. In fact, there are just three species which are native to India: Etroplus suratensis, Pseudetroplus maculatus, and the cool and hard-to-find Etroplus canarensis.

Oh, the name. It drives me crazy:

The official Meriam-Webster origin of the name is, "chromide, ultimately from Greek chromis, a sea fish"

A sea fish? WTF?

Yeah, not really satisfying. And it begged me to do little more digging, of course!

But I tried to find out more for you. Now, interestingly, the fish was originally described by the ichthyologist Bloch in 1795 as Chaetodon maculatus...and if this genus sounds familiar to us saltwater aquarium geeks, it should- that's the same genus in which many marine Butterflyfishes are found. And, the fish seems to bear at least a very superficial physical resemblance to a marine Butterflyfish of that genus at first glance...

So, the "Chromide" part of the popular name refers to it's appearance as a "sea fish", or chromis. And, to add a final note of confusion to this taxonomic/popular name scramble, Chromis is a popular genus of colorful marine Damselfishes... So the popular name of this fish is based on it being confusingly similar in appearance to a marine fish... Oh, weird, right?

Yeah, that's why common names are often fraught with problems, and for the ultimate in accuracy, we should at least have a working familiarity with the Latin species names of our fishes. Oh, and this little fish has been bounced around a few genera over the years, from Chaetodon to Etroplus, and finally to Pseudetroplus!

Okay, whatever you call it...This is a pretty interesting fish! Even if it IS a cichlid!😆

And, about that brackish-water thing...

The Orange Chromide endemic to freshwater and brackish streams, lagoons and estuaries in southern India and Sri Lanka. And of course, as soon as we in the hobby hear the word "brackish" when discussing some of the natural habitats in which the fish is found, it forever becomes a brackish water fish!

That's just how it goes in the aquarium hobby, right?

The reality is that the Orange Chromide is classified as a euryhaline fish, and mostly inhabits brackish estuaries, coastal lagoons and the lower reaches of rivers.

Euryhaline.

Damn, we've heard that term before, haven't we?

eu·ry·ha·line (yo͝or′ə-hā′līn′, -hăl′īn′) adj. - Capable of tolerating a wide range of salt water concentrations. Used of an aquatic organism.

That single definition seems to give us as hobbyists the freedom to label the fish as a brackish water fish, despite the fact that it has the ability to live in both pure freshwater and brackish water conditions.

It helps to know exactly where your specimens come from, right?

I was lucky when I sourced my specimens, as there was no ambiguity about what type of habitat they were originally from. Or should I say, where their parents came from. They were actually F1 from parents collected in a brackish water lagoon in the state of Karnataka in western India, so I was pretty happy to be able to keep them in a brackish aquarium and have the confirmation that they were only a generation removed from a natural brackish water habitat.

Okay, all well and good for me, but what if you're not so sure about where your Chromides come from? Well, as we discussed a minute ago, they are euryhaline fishes, and can adapt to brackish relatively easily. You just need to do it very gradually, like over a week or more.

Now, one thing I will tell you about these fishes is that, despite their peaceful reputation, and relatively they can be little shits among themselves. These guys are pretty social...but they also have a social order, which is maintained when feeding and even schooling. The "Alpha male" generally gets to eat first, followed by the less dominant specimens..and of course, he leads the "pack" when they school in the tank (and they do, which is pretty cool!).

And, yeah, the social order in a group of these guys is a big deal. The dominant fish WILL, indeed pick on the weakest ones. In fact, I lost a few over the years due to a super aggressive dominant male essentially bullying and beating the shit out of the subordinate ones in my group before I could remove them.

It sucks.

However, I will tell you to keep them in a group. Not only do they seem to be happier that way, but they display the most interesting behaviors- short of this harassment of the really weak ones. I'd love to tell you that, with a large enough tank, this won't be as big an issue, but I kept mine in a decent-sized tank with lots of hiding spaces and it still was an issue, so...

Another thing about these fishes that you will read is that they are relatively intolerant of poor water quality. Without sounding like an arrogant S.O.B., I'd have to tell you that I won't dispute this, but can't confirm it, because- like most of you- I maintain high water quality in my tanks! It's one of those things that I will just typically accept as a given.

Like many cichlids, spawning is typically a given, given the passage of time and under appropriate environmental conditions. (ie; being in water...)

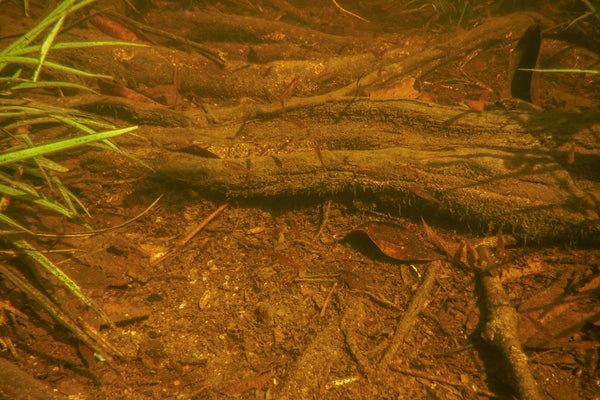

In the wild, the Orange Chromide spawns in shallow water, typically in a depression in the substrate excavated by both parents. What that tells you, BTW, is that this fish is best kept in a tank with sand, sediment, or other soft substrate materials if you intend to breed them.

It's time to play with dirt, soil, mud, silt, decomposing leaves, branches, marginal plants, roots...materials which replicate both the appearance and function of natural habitats from which many of our fishes come. And, if utilized skillfully and thoughtfully, can yield functionally aesthetic aquariums far different and unique from anything previously attempted in the aquarium hobby. Another call to the evolved, botanical-style brackish-water aquarium!

In Nature, Orange Chromides spawn twice a year, during the drier pre-monsoonal and monsoonal seasons, in which the salinity is slightly higher (an interesting takeaway for us!). During these times, the turbidity of the water is lower, and the parents can more easily construct their nests and maintain visual contact with their fry after they hatch.

Interestingly, in Nature, when Orange Chromide pairs spawn in isolation, they tend to construct nests in areas of dense aquatic vegetation or root systems, which provide a lot of camouflage. Ecologists also have noted that during the month of July, which is their peak breeding season, Chromides will construct their nests in areas that are rather sparsely filled with vegetation, roots, etc.- a sort of compromise between fry survival and foraging opportunities for the adults.

Other, non-spawning fishes will also make use of these areas, increasing the threat to the broods of fry which emerge after hatching. Under these conditions, most Orange Chromides nest in colonies, which is believed to help decrease predation.

Hmm, breeding colonies? Interesting!

About 200 eggs are laid in a typical event, according to just about every source you'll find in the aquarium world. Of course, the largest batch I ever counted was around 100 or so eggs. The eggs hatch after about 5 days, during which time the parents tend to, and fan them.

In typical cichlid fashion, one parent will always remain with the eggs while the other goes out and forages for food. The fry of Orange Chromides feed on the mucus secreted onto the skin of their parents, like Discus or Uaru do. This form of feeding is called "contacting" by biologists. And perhaps most interesting, the good-sized fry are guarded by parents until they almost reach sexual maturity and are almost the size of the parents! Like, a pretty long time! This is a very unique behavior in cichlids!

It is known that immunoglobulin concentrations are higher in the breeding fish than they are in non-breeding ones, and are highest in wild breeding individuals. Biologists are curious to ascertain whether this immunoglobulin is passed on to the contacting fry in the same concentrations as it is found in the mucus. If it is, the big question is how does the increased amount of immunoglobulin affect the growth and survival of these fry?

Neat stuff.

Want a final bit of unusual trivia on this fish?

They're cleaners!

Yeah, it's been documented by researchers Richard L. Wyman and Jack A. Ward that the young of Pseudetroplus maculatus actively clean the related species, Etroplus suratensis (the "Green Chromide") when they occur together. .E. suratensis are naturally inhibited from attacking small fish, in case you are wondering!

Much like what you see in the ocean, with Wrasses or Shrimp cleaning territories are established by the young Orange Chromides, and the "shop hours"seem to follow a daily circadian rhythm. This is a unique, almost symbiotic kind of behavior, in which removal of fungus from fins and tail of the E. suratensis appears to be an important adaptive function of this symbiosis.

Interestingly, it's thought by researchers that the "contact feeding" behavior in Orange Chromide fry during parental care may have aided in the evolution of this cleaning relationship. This represents the first report of a cleaning symbiosis involving cichlid fish.

So, yeah, there is much more to this "old hobby favorite" than we might first imagine!

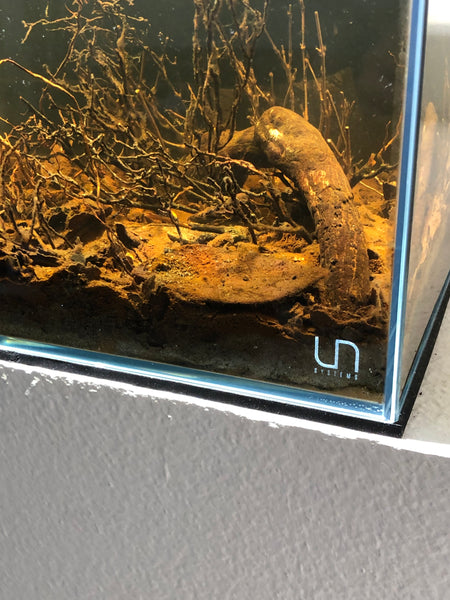

So, what would be some cool ways to keep this fish? Well, to begin with, you should definitely keep them in an aquarium with a fair amount of substrate, roots, and perhaps even a few aquatic plants. Now, if you're aiming to go brackish, it brings up the usual "What plants can grow in brackish water?" discussions...And yeah, there are a few, and you'll need to research that. (Hint: Cryptocoryne ciliata )

Or, you could keep it simple and go for something like a tangled hardscape, with wood and roots, mixed with sand and small quantities of rubble. This would be a very interesting representation of the monsoonal conditions.

Or, you could simply do a "proper" brackish water aquarium with my fave all time plant, the Red Mangrove (Rhizophora mangle). This would be a very rewarding way to keep these fishes, as I can attest!

Yes, new brackish-water fishes will become more readily available when the market demand is there. In the mean time, we can focus on some of the cool fishes from these habitats which are currently available to us, like our pal the Orange Chromide. And the brackish water habitats are as interesting, dynamic, and bountiful as any on the planet.

There is still a surprisingly large amount of misinformation about there concerning fishes long thought to be "brackish", when the reality is that they are often found predominantly in non-brackish habitats, with perhaps only isolated populations of fishes being brackish fishes.

Fortunately for us, our friend the Orange Chromide is one of those which you can do the research on and find a surprisingly large amount of interesting, scholarly information out there.

You just have to be willing to look.

Stay motivated. Stay curious. Stay excited. Stay diligent. Stay persistent...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Stuff we've been told to fear...

A couple of days back, I was chatting with a fellow hobbyist who wanted to jump in to something a bit different within the aquarium hobby, but was afraid of the possible consequences-both socially and in his aquariums. He feared criticism from "them", and that just froze him. I felt bad that he was so afraid of criticism from others should he question the "status quo" within the hobby.

Perhaps my story might be helpful to you if you're afraid of such criticisms.

For generations, we've been told in the aquarium hobby that we need to be concerned about the appearance of all kinds of stuff in our tanks, like algae, detritus, and "biocover".

For some strange reason, we as a hobby group seems emphasize stuff like understanding some biological processes, like the nitrogen cycle, yet we've also been told to devote a lot of resources to siphoning, polishing, and scrubbing our tanks to near sterility.

It's a strange dichotomy.

I remember the first few botanical-style tanks I created, almost two decades ago now, would hit that phase early on when biofilms and fungal growths began to appear, and I'd hear my friends telling me, "Yeah, your tank is going to turn into a big pile of shit. Told you that you can't put that stuff in there."

Because that's what they've been told. The prevailing mindset in the hobby was that the appearance of these organisms was an indication of an unsuitable aquarium environment.

Anyone who's studied basic ecology and biology understands that the complete opposite is true. The appearance of these valuable life forms is an indicator that your aquatic environment is ideal to foster a healthy, diverse community of aquatic organisms, including fishes!

Exactly like in Nature.

I remember telling myself that this is what I knew was going to happen. I knew how biofilms and fungal growths appear on "undefended" surfaces, and that they are essentially harmless life forms, exploiting a favorable environment. I knew that fungi appear as they help break down leaves and botanicals. I knew that these are perfectly natural occurrences, and that they typically are transitory and self-limiting to some extent.

Normal for this type of aquarium approach. I knew that they would go away, but I also knew that there would be a period of time when the tank might look like a big pool of slimy shit. Or, rather, it'd look like a pile of slimy shit to those who weren't familiar with these life forms, how they grow, and how the natural aquatic habitats we love so much actually function and appear!

To reassure myself, I would stare for hours at underwater photos taken in the Amazon region, showing decaying leaves, biofilms,and fungi all over the leaf litter. I'd read the studies by researchers like Henderson and Walker, detailing the dynamics of leaf litter zones and how productive and unique they were.

I'd pour over my water quality tests, confirming for myself that everything was okay. It always was. And of course I would watch my fishes for any signs of distress...

I never saw them.

I knew that there wouldn't be any issues, because I created my aquariums with a solid embrace of basic aquatic biology; an understanding that an aquarium is not some sort of underwater art installation, but rather, a living, breathing microcosm of organisms which work together to create a biome..and that the appearance of the aquarium only tells a small part of the story.

I knew that this type of aquatic habitat could be replicated in the aquarium successfully. I realized that it would take understanding, trial and error, and acceptance that the aquariums I created would look fundamentally different than anything I had experienced before.

I knew I might face criticism, scrutiny, and even downright condemnation from some quarters for daring to do something different, and then for labeling what most found totally distasteful, or have been conditioned by "the hobby" for generations to fear, as simply "a routine part of the process."

It's what happens when you venture out into areas of the hobby which are a bit untested. Areas which embrace ideas, aesthetics, practices, and occurrences which have existed far out of the mainstream consciousness of the hobby for so long. Fears develop, naysayers emerge, and warnings are given.

Yet, all of this stuff- ALL of it- is completely normal, well understood and documented by science, and in reality, comprises the aquatic habitats which are so successful and beneficial for fishes in both Nature and the aquarium. We as a hobby have made scant little effort over the years to understand it. And once you commit yourself to studying, understanding, and embracing life on all levels, the world of natural, botanical-style aquariums and its untapped potential opens upon to you.

Mental shifts are required. Along with study, patience, time, and a willingness to look beyond hobby forums, aquarium literature, and aquascaping contests for information. A desire to roll up your sleeves, get in there, ignore the naysayers, and just DO.

Don't be afraid of things because they look different, or somehow contrary to what you've heard or been told by others is "not healthy" or somehow "dangerous." Now sure, you can't obey natural "laws" like the nitrogen cycle, understanding pH, etc.

You can, however, question things you've been told to avoid based on superficial explanations based upon aesthetics.

Mental shifts.

Stuff that makes you want to understand how life forms such as fungi, for example, arise, multiply, snd contribute to the biome of your aquarium.

Let's think about fungi for a minute...a "poster child" for the new way of embracing Nature as it is.

Fungi reproduce by releasing tiny spores that then germinate on new and hospitable surfaces (ie, pretty much anywhere they damn well please!). These aquatic fungi are involved in the decay of wood and leafy material. And of course, when you submerge terrestrial materials in water, growths of fungi tend to arise. Anyone who's ever "cured" a piece of wood for your aquarium can attest to this!

Fungi tend to colonize wood because it offers them a lot of surface area to thrive and live out their life cycle. And cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, the major components of wood and botanical materials, are degraded by fungi which posses enzymes that can digest these materials! Fungi are regarded by biologists to be the dominant organisms associated with decaying leaves in streams, so this gives you some idea as to why we see them in our aquariums, right?

And of course, fishes and invertebrates which live amongst and feed directly upon the fungi and decomposing leaves and botanicals contribute to the breakdown of these materials as well! Aquatic fungi can break down the leaf matrix and make the energy available to feeding animals in these habitats. And look at this little gem I found in my research:

"There is evidence that detritivores selectively feed on conditioned leaves, i.e. those previously colonized by fungi (Suberkropp, 1992; Graca, 1993). Fungi can alter the food quality and palatability of leaf detritus, aecting shredder growth rates. Animals that feed on a diet rich in fungi have higher growth rates and fecundity than those fed on poorly colonized leaves. Some shredders prefer to feed on leaves that are colonized by fungi, whereas others consume fungal mycelium selectively..."

"Conditioned" leaves, in this context, are those which have been previously colonized by fungi! They make the energy within the leaves and botanicals more available to higher organisms like fishes and invertebrates!

The aquatic fungi which will typically decompose leaf litter and wood are the group known as “aquatic hyphomycetes”. Another group of specialists, "aero-aquatic hyphomycetes," colonize submerged plant detritus in stagnant and slow- flowing waters, like shallow ponds, puddles, and flooded forest areas. Fungal communities differ between various environments, such as streams, shallow lakes and wetlands, deep lakes, and other habitats such as salt lakes and estuaries.

And we see them in our own tanks all the time, don't we? Sure, it's easy to get scared by this stuff...and surprisingly, it's even easier to exploit it as a food source for your animals! We just have to make that mental shift... As the expression goes, "when life gives you lemons, make lemonade!"

I knew when I started Tannin that I had to "walk the walk." I had to explain by showing my tanks, my work, and giving fellow hobbyists the information, advice, and support they needed in order to confidently set out on their own foray into this interesting hobby path.

I'm no hero. Not trying to portray myself as a visionary.

The point of sharing my personal experience is to show you that trying new stuff in the hobby does carry risk, fear, and challenge, but that you can and will persevere if you believe. If you push through. IF you don't fear setbacks, issues, criticisms from naysayers.

You have to try. In my case, the the idea of throwing various botanical items into aquariums is not my invention. It's not a totally new thing. People have done what I've done before. Maybe not as obsessively or thoroughly presented (and maybe they haven't built a business around the idea!), but it's been done many, many times.

The fact is, we can and should all take these kinds of journeys.

Stay the course. Don't be afraid. Open your mind. Study what is happening. Draw parallels to the natural aquatic ecosystems of the world. Look at this "evolution" process with wonder, awe, and courage.

And know that the pile of decomposing leaves, fungal growth, and detritus that you're looking at now is just a steppingstone on the journey to an aquarium which embrace nature in every conceivable way.

Stay brave. Stay curious. Stay diligent. Stay observant...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Transitional Habitats...A new aquarium hobby frontier?

We've spent a lot of time over the least several years talking about the idea of recreating specialized aquatic systems. We've talked a lot about transitional habitats- ecosystems which alternate between terrestrial and aquatic at various times of the year. These are compelling ecosystems which push the very limits of conventional aquarium practice.

As you know, we take a "function first" approach, in which the aesthetics become a "collateral benefit" of the function. Perhaps the best way to replicate these natural aquatic systems inner aquariums is to replicate the factors which facilitate their function. So, for example, let's look at our fave habitats, the flooded forests of Amazonia or the grasslands of The Pantanal.

To create a system that truly embraces this idea in both form and function, you'd start the system as a terrestrial habitat. In other words, rather than setting up an "aquarium" habitat right from the start, you'd be setting up what amounts to a terrarium. Soil/sand, terrestrial plants and grasses, leaves, seed pods, and "fallen trees/branches" on the "forest floor."

You'd run this system as a terrestrial display for some extended period of time- perhaps several weeks or even months, if you can handle it- and then you'd "flood" the terrestrial habitat, turning it into an aquatic one. Now, I'm not talking about one of our "Urban Igapo" nano-sized tanks here- I"m talking about a full-sized aquarium this time.

This is different in both scale and dynamic. After the "inundation", it's likely that many of the plants and grasses will either go dormant or simply die, adding other nutrient load in the aquarium.

A microbiome of organisms which can live in the aquatic environment needs to arise to process the high level of nutrients in the aquarium. Some terrestrial organisms (perhaps you were keeping frogs?) need to be removed and re-housed.

The very process of creating and populating the system during this transitional phase from terrestrial to aquatic is a complex, fascinating, and not entirely well-understood one, at least in the aquarium hobby. In fact, it's essentially a virtually unknown one. We simply haven't created all that many systems which evolve from terrestrial to aquatic.

Sure, we've created terrariums, paludariums, etc. We've seen plenty of "seasonally flooded forest" aquairums in biotope aquarium contests...But this is different. Rather than capturing a "moment in time", recreating the aquatic environment after the inundation, we're talking about recreating the process of transformation from one habitat to another.

Literally, creating the aquatic environment from a terrestrial one.

Psychologically, it would be sort of challenging!

I mean, in this instance, you've been essentially running a "garden" for several months, enjoying it and meeting the challenges which arise, only to embark several months later on a process which essentially destroys what you've created, forcing you to start anew with an entirely different environment, and contend with all of its associated challenges (the nitrogen cycle, nutrient control, etc.)

Modeling the process.

Personally, I find this type of approach irresistible. Not only do you get to enjoy all sorts of different aspects of Nature- you get to learn some new stuff, acquire new skills, and make observations on processes that, although common in Nature, were previously unrecorded in the aquarium hobby.

You'll draw on all of your aquarium-related skills to manage this transformation. You'll deal with a completely different aesthetic- I mean, flooding an established, planted terrestrial habitat filled with soils and plants will create a turbid, no doubt chaotic-looking aquascape, at least initially.

This is absolutely analogous to what we see in Nature, by the way.Seasonal transformations are hardly neat and tidy affairs.

Yes, we place function over form. However, that doesn't mean that you can't make it pretty! One key to making this interesting from an aesthetic perspective is to create a hardscape of wood, rocks, seed pods, etc. during the terrestrial phase that will please you when it’s submerged.

You'll need to observe very carefully. You'll need to be tolerant of stuff like turbidity, biofilms, algae, decomposition- many of the "skills"we've developed as botanical-style aquarists.You need to accept that what you're seeing in front of you today will not be the way it will look in 4 months, or even 4 weeks.

You'll need incredible patience, along with flexibility and an "even keel.”

We have a lot of the "chops" we'll need for this approach already! They simply need to be applied and coupled with an eagerness to try something new, and to help pioneer and create the “methodology”, and with the understanding that things may not always go exactly like we expect they should.

For me, this would likely be a "one way trip", going from terrestrial to aquatic. Of course, much like we've done with our "Urban Igapo" approach, this could be a terrestrial==>aquatic==>terrestrial "round trip" if you want! That's the beauty of this. You could do a complete 365 day dynamic, matching the actual wet season/dry season cycles of the habitat you're modeling.

Absolutely.

The beauty is that, even within our approach to "transformational biotope-inspired" functional ecosystems, you CAN take some "artistic liberties" and do YOU. I mean, at the end of the day, it's a hobby, not a PhD thesis project, right?

Yeah. Plenty of room for creativity, even when pushing the state of the art of the hobby! Plenty of ways to interpret what we see in these unique ecosystems.

Habitats which transition from terrestrial to aquatic require us to consider the entire relationship between land and water- something that we have paid scant little attention to in the aquarium hobby, IMHO.

And this is unfortunate, because the relationships and interdependencies between aquatic habitats and their terrestrial surroundings are fundamental to our understanding of how they evolve and function.

There are so many other ecosystems which can be modeled with this approach! Floodplain lakes, streams, swamps, mud holes...I could go on and on and on. The inspiration for progressive aquariums is only limited to the many hundreds of thousands of examples which Nature Herself has created all over the planet.

We should look at nature for all of the little details it offers. We should question why things look the way they do, and postulate on what processes led to a habitat looking and functioning the way it does- and why/how fishes came to inhabit it and thrive within it.

With more and more attention being paid the overall environments from which our fishes come-not just the water, but the surrounding areas of the habitat, we as hobbyists will be able to call even more attention to the need to learn about and protect them when we create aquariums based on more specific habitats.

The old adage about "we protect what we love" is definitely true here!

And the transitional aquatic habitats are a terrific "entry point"into this exciting new area of aquarium hobby work.

Stay inspired. Stay creative. Stay observant. Stay resourceful. Stay diligent...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Someplace like...home?

Like so many of you, I am utterly awed by the sheer variety of tropical fish species that we've managed to breed in our aquariums over the decades. This is a testimony to the skill set and dedication of talented hobbyists and commercial breeders worldwide. And with obvious implications for some wild populations of fishes whose habitats arena danger, the idea of breeding fishes is a timely one.

Of course, there are absolutely benefits to a well-managed wild fishery, too, including protection of resources, economic benefits to indigenous peoples, and the preservation of wild populations. Programs like Project Piaba in Brazil have shown the tangible benefits to the people, environment, and the fishes that may be had with a properly-managed program of sourcing wild-caught fishes.

And, when it comes to the way we keep our fishes in the hobby on an everyday basis, I find a very interesting dichotomy here...

Have you ever thought about the way we've "domesticated" the fishes that we keep in our aquariums? I mean, the way we have sort of categorically "made" fishes more accommodating of the environmental conditions that we would like to provide them with in our aquariums? For example, we've proudly advertised that fishes like Discus don't require soft, acidic water to thrive and reproduce. In fact, a number of breeders spawn and rear them in harder, more alkaline conditions.

This is interesting and makes me think about this from multiple angles...good and bad.

As you know, I tend to spend a fair amount of time snooping around the scientific literature online, looking for tidbits of information that might fit nicely into our fascination and evolving technique with natural blackwater and brackish- aquariums.

It's a pretty fun, albeit geeky- pastime, really- and quite educational, too!

And one of the interesting things about sifting through much of the scientific stuff is that you can occasionally find bits and pieces of information which may not only confirm a "hunch" that you have had about something- these data can sometimes send you into an entirely new direction! (I know that it can, lol!)

As a lover of brackish-water habitats, I've spent a lot time over the years researching suitable fishes and other aquatic organisms from this environment for aquarium keeping. I've made a lot of interesting discoveries about brackish water habitats and the fishes which supposedly occur in them.

Notice I use the term "supposedly..?"

Interestingly, many of the fishes that we in the hobby have assigned the "brackish" moniker to are actually seldom found in these types of habitats. Perhaps some small populations of some of these fishes might be from mildly brackish environments, but many of them are primarily found in pure freshwater.

Perhaps through a combination of misinformation, assumption, and successful practice by a few hobbyists over the years, we've sort of attached the "brackish water fish" narrative to them in general.

Now, sure, many fishes can adapt to brackish water conditions, but I'm more fascinated by the fishes which are actually found naturally in these environments. And it's always interesting when you can find out that a fish which you have previously dismissed as not having typically come from this environment actually does come from it naturally!

It's like a little discovery!

One of those happy "surprises" is our good friend, the "Endler's Livebearer", Poceilia wingei. Many of you love this fish and keep it extensively.

This popular fish is widely kept under "typical livebearer conditions" in the aquarium ( higher pH and harder water).

However, there are a number of wild populations form their native Venezuela which inhabit mildly brackish water coastal lagoons and estuaries, for example, Laguna de los Patos, near Cumana, which has definite ocean influence, although it is far less salty than researchers thought it may have been in the past. And the wild populations residing there might very well be considered "endangered", or at least, limited.

Now, this kind of stuff is not "revolutionary" from a hobby standpoint, as it seems like we've known this for some time. And although the fish are very adaptable, we don't hear all that much about keeping them in what we'd call "brackish" conditions (like typically SG of 1.003-1.005, although I like to push it a bit higher, lol). It's just interesting to ponder and kind of get your head around.

And with all of the popularity of this fish, it seems to me like the brackish water habitat for this species has not been embraced much from a hobby standpoint.

And I suppose it makes sense- it's far easier to simply give fishes harder, alkaline water than to "mess with adding salt" to their tanks for a lot of hobbyists. In addition, wild populations of these fishes are scant, as is natural habitat data, so indeed confirming with any great certainty that they are even still occurring in these types of habitats is sketchy.

And often, so-called 'populations" of fishes in these specialized habitats might have been distributed as a result of actions by man, and are not even naturally occurring there- further confounding things!

In general, the question about adding salt to livebearer tanks has been debated for a long time, and there are many views on the subject. Obviously, the ultimate way to determine if you should or should not add salt to an Endler's or other livebearer tank would be to consider the natural habitats of the population you're working with.

Easier said than done, because the vast majority of them are now commercially or hobbyist bred for generations- especially Endler's- and wild collection data is not always easy to obtain.

I think the debate will go on for a long time!

Yet, with the increasing popularity of brackish water aquariums, we're hoping to see more experiments along this line for many different species! I was recently very happy to secure some specimens of the miserably-named "Swamp Guppy", Micropoceilia picta, a fish which absolutely does come from brackish water. And I have no intention of ever "adapting" them to environmental conditions which are more "convenient" for us hobbyists!

Now, you know I've always been a fan of sort of "re-adapting" or "re-patriating" even captive-bred specimens of all sorts of fishes (like "blackwater-origin" characins, cichlids, etc.) to more "natural" conditions (well, "natural" from perhaps a few dozen generations back, anyhow). I am of the opinion that even "domesticated" fishes can benefit from providing them with conditions more reminiscent of those from the natural habitats from which they originated.

Although I am not a geneticist or biological ethicist, I never will buy into the thought that a few dozen captive generations will "erase" millions of years of evolutionary adaptation to specific habitats, and that re-adapting them to these conditions is somehow "detrimental" to them. Something just seems "off" to me about that thinking.

I just can't get behind that.

Now, even more compelling "proof" of that it's not so "cut-and-dry" is that many of the recommended "best practices" of breeding many so-called "adaptable" species are to do things like drop water temperatures, adjust lighting, or perform water exchanges with peat-influenced water, etc....stuff intended to mimic the conditions found in the natural habitats of the fishes...

I mean...WTF? Right?

Like, only give the fishes their "natural" conditions when we want to breed them? Really? That mindset just seems a bit odd to me...

Of course, there are some fishes for which we don't really make any arguments against providing them with natural-type environmental conditions, such as African rift lake Cichlids.

I find this absolutely fascinating, from a "hobby-philosopher" standpoint!

And then, there are those fishes which we have, for various reasons (to minimize or prevent the occurrence of diseases) arbitrarily decided to manipulate their environment deliberately away from the natural characteristics under which they evolved for specific reasons. For example, adding salt to the water for fishes that are typically not known to come from brackish habitats.

Examples are annual Killifishes, such as Nothobranchius, which in many cases don't come from brackish environments naturally, yet we dutifully add salt to their water as standard practice. The adaptation to a "teaspoon of salt per gallon" or so environment is done for prophylactic reasons, rather than what's "convenient" for us- a rather unique case, indeed...and again, something that I find fascinating to look at objectively.

Is salt simply the easiest way to prevent parasitic diseases in these fishes, or are there other ways which don't require such dramatic environmental manipulations?

And then, of course, there are those unexpected populations of fishes, like various Danios and Gold Tetras, for example, which are found in mildly brackish conditions...Compelling, interesting...yet we can't conclude that all Gold Tetras will benefit from salt in their water, can we?

And, as we evolved to a more sustainable hobby, with greater emphasis on captive -bred or carefully-sourced wild fishes, and as more wild habitats are damaged or lost, will we also lose valuable data about the wild habitats of the fishes we love so much?

Data which will simply make the "default" for many fishes to be "tap water?"

I hope not.

Is it possible, though, that we've been so good at "domesticating" our fishes to our easier-to-provide tap water conditions- and our fishes so adaptable to them- that the desire to "repatriate" them to the conditions under which they've evolved is really more of a "niche" thing for geeky hobbyists, as opposed to a "necessary for success" thing?

I mean, how many Discus are now kept and bred exclusively in hard, alkaline water- markedly different than the soft, acid blackwater environmental conditions under which they've evolved for eons? Am I just being a dreamer here, postulating without hard data that somehow the fishes are "missing something" when we keep and breed them in conditions vastly different than what the wild populations come from?

Do the same genetics which dictate the color patterns and fin morphology also somehow "cancel out" the fish's "programming" which allows them to be healthiest in their original native conditions?

How do we reconcile this concept?

In the end, there are a lot of variables in the equation, but I think that the Endler's discussion is just one visible example of fishes which could perhaps benefit from experimenting with "throwback" conditions. I'm by no means anything close to an expert on these fish, and my opinions are just that- opinions. Commercially, it may not be practical to do this, but for the hobbyist with time, resources, and inclination, it would be interesting to see where it takes you.

Like, would the same strain kept in both brackish and pure freshwater habitats display different traits or health characteristics?

Would there even be any marked differences between specimens of certain fishes kept under "natural" versus "domesticated" conditions? Would they show up immediately, or would it become evident only after several generations? And again, I think about brackish-water fishes and the difficulty of tracing your specimens to their natural source, which makes this all that much more challenging!

I look forward to many more such experiments- bringing natural conditions to "domesticated" fishes, and perhaps unlocking some more secrets...or perhaps simply acknowledging what we all know:

That there truly is "no place like home!"

Stay observant. Stay curious. Stay adventurous. Stay resourceful. Stay experimental. Stay relentless...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

No expiration date.

We talk a lot about starting up and managing botanical-style aquariums. We have had numerous discussions about set up and the accompanying expectations of the early days in the life of the little ecosystems we've created. However, what about the long term..The really long term?

Like, how long can you maintain one of these aquariums?

Do they have an "expiration date? A point when the system no longer "grows" or thrives?

There is a term, sometimes used to describe the state of very old aquariums- "senescence." The definition is: "...the condition or process of deterioration with age." Well, that doesn't sound all that unusual, right? I mean, stuff ages, gets old, stops functioning well, and eventually expires...aquariums are no different, right?

Well, I don't think so.

Sometimes, this deterioration is referred to in the hobby by the charming name of "Old Tank Syndrome"

Now, on the surface, this makes some sense, right? I mean, if your tank has been set up for several years, environmental conditions will change over time. Among the many phenomenon brought up by proponents of this theory is the increase in nitrate levels. People who buy into "OTS" will tell you that nitrate levels will increase over time.

They'll tell you that phosphate, which typically comes into our tanks with food, will accumulate, resulting in excessive, perhaps rampant, algal growths. You know, the kind from which aquarium horror stories are made.

They will tell you that the pH of the aquarium will decline as a result of accumulating nitrate, with hydrogen ions utilizing all available buffers, resulting in a reduction of the pH below 6 (like, IS that a problem?), which supposedly results in the beneficial bacteria ceasing to convert ammonia into nitrite and nitrate and creating a buildup of toxic ammonia...

I mean, it's absolutely possible. We've talked about the potential cessation of the nitrogen cycle as we know it at low pH levels, and about the archaens which take over at these low pH levels. (That's a different "thing", though, and off topic ATM)

Of course, all of the bad things espoused by the OTS theorists can and will happen...If you never do any tank maintenance. If you simply abandon the idea of water exchanges, continue stocking and feeding your aquarium recklessly, and essentially abandon the basic tenants of aquarium husbandry.

The problem with this theory is that it assumes all aquarists are knuckleheads, refusing to perform water exchanges, while merrily going about their business of watching the pretty fishes swim. It seems to forecast some sort of inevitability that this will happen to every tank.

No way. Uh-uh. I call B.S. on this.

As someone who has kept all sorts of tanks (reef tanks, freshwater fish-only tanks, etc.) in operation for many years (my longest was 13 years, and botanical-style tanks going on 5 plus years), I can't buy into this idea. I mean, sure, if you don't set up a system properly in the first place, and then simply become lackadaisical about husbandry, of course your tank can decline.

But, here's the thing: It's not inevitable.

RULE OF THUMB: Do fucking maintenance, feed carefully, and don't overstock. This is not "rocket science!"

Rather than "Old Tank Syndrome"- a name which seems to imply that it's not our fault, and that it's like some unfortunate, random occurrence which befalls the unsuspecting-we should call it LAAP- "Lazy Ass Aquarists' Payback."

'Cause that's what it IS. It's entirely the fault of a lazy-ass aquarist. Preventable and avoidable.

Need more convincing that it's not some random "malady" that can strike any tank? That it's some "universal constant" which commonly occurs in all aquariums?

Think about the wild habitats which we attempt to model our aquariums after. Do these habitats decline over time for no reason? Generally, no. They will respond to environmental changes, like drought, pollution, sedimentation, etc. They will react to these environmental pressures or insults. They will evolve over time.

Now, sure, seasonal desiccation and such result in radical environmental shifts in the the aquatic environment and a definite "expiration date"- but you seldom hear of aquatic habitats declining and disappearing or becoming otherwise uninhabitable to fishes without some significant (often human-imposed) external pressures- like pollution, ash from fires or volcanoes, deliberate diversion or draining of the water source (think "Rio Xingu"), logging operations, climate change, etc.

Of course, our aquariums are closed ecosystems. However, the same natural laws which govern the nitrogen cycle or other aspects of the system's ecology in Nature apply to our aquariums. The big difference is that our tanks are almost completely dependent upon us as aquarists applying techniques which replicate some of the factors and processes which apply in Nature. Stuff like water exchanges, etc.

So if we keep up the nutrient export processes, don't radically overstock our systems, feed appropriately, maintain filters, and observe them over time, there is no reason why we couldn't maintain our aquariums indefinitely.

There is no "expiration date."

And the cool thing about botanical-style aquariums is that part of our very "technique" from day one is to facilitate the growth and reproduction of beneficial microfauna, like bacteria, fungal growths, etc., and to allow decomposition to occur to provide them feeding opportunities.What this does is help create a microbiome of organisms which, as we've said repeatedly, form the basis of the "operating system" of our tanks.

Each one of these life forms supporting, to some extent, those above...including our fishes.

So, yeah- botanical-style aquariums are "built" for the long run. Provided that we do our fair share of the work to support their ecology. Just because we add a lot of botanical material, allow decomposition, and tend to look on the resulting detritus favorably doesn't mean that these are "set-and-forget" systems, any more than it means they're particularly susceptible to all of the problems we discussed previously.

Common sense husbandry and observation are huge components of the botanical-style aquarium "equation."

As part of our regular husbandry routine, we keep the ecosystem "stocked" with fresh botanicals and leaves on a continuous basis, to replenish those which break down via decomposition. This is perfectly analogous to the processes of leaf drop and the influx of allochthonous materials from the surrounding terrestrial habitat which occur constantly in the wild aquatic habitats which we attempt to replicate.

We favor a "biology/ecology first" mindset.

Replenishing the botanical materials provides surface area and food for the numerous small organisms which support our systems. It also provides supplemental food for our fishes, as we've discussed previously. It helps recreate, on a very real level, the "food webs" which support the ecology of all aquatic ecosystems.

And it sets up botanical-style aquariums to be sustainable indefinitely.

Radical moves and "Spring Cleanings" are not only unnecessary, IMHO- they are potentially disruptive and counter-productive. Rather, it's about deliberate moves early on, to facilitate the emergence of this biome, and then steady, regular replenishment of botanical materials to nourish and sustain the ecosystem.

My belief is steeped in the mindset that you've created a little ecosystem, and that, if you start removing a significant source of someone's food (or for that matter, their home!), there is bound to be a net loss of biota...and this could lead to a disruption of the very biological processes that we aim to foster.

Okay, it's a theory...But I think I might be on to something, maybe? So, like here is my theory in more detail:

Simply look at the botanical-style aquarium (like any aquarium, of course) as a little "microcosm", with processes and life forms dependent upon each other for food, shelter, and other aspects of their existence. And, I really believe that the environment of this type of aquarium, because it relies on botanical materials (leaves, seed pods, etc.), is significantly influenced by the amount and composition of said material to "operate" successfully over time.

No expiration date.

Personally, I don't think that botanical-style aquariums are ever "finished", BTW. They simply continue to evolve over extended periods of time, just like the wild habitats that we attempt to replicate in our tanks do.

The continuous change, development, and evolution of aquatic habitats is a fascinating, compelling area to study- and to replicate in our aquaria. I'm convinced more than ever that the secrets that we learn by fostering and accepting Nature's processes and dynamics are the absolute key to everything that we do in the aquarium.

The idea that your aquarium environment simply deteriorates as a result of its very existence is, in my humble opinion, wrong, narrow-minded, and outdated thinking. (Other than that, it's completely correct!😆).

Seriously, though...

"Old Tank Syndrome" is a crock of shit, IMHO.

Aquariums only have an "expiration date" if we don't take care of them. Period. No more sugar coating this.

If we look at them assume sort of "static diorama" thing, requiring no real care, they definitely have an "expiration date"; a point where they are no longer sustainable. When we consider our aquariums to be tiny, closed ecosystems, subject to the same "rules" which govern the natural environments which we seek to replicate, the parallels are obvious. The possibilities open up. And the potential to unlock new techniques, ideas, and benefits for our fishes is very real and truly exciting!

I'm not entirely certain how this approach to aquariums, and this idea of fostering a microbiome within our tank and caring for it has become a sort of "revolutionary" or "counter-culture" sort of thing in the hobby, as many fellow hobbyists have told me that they feel it is.

Label it what you want, I think that, if we make the effort to understand the function of our tanks as much as we do the appearance, then it all starts making sense. If you look at an aquarium as you would a garden- an organic, living, evolving, growing entity- one which requires a bit of care on our part in order to thrive-then the idea of an "expiration date" or inevitable decline of the system becomes much less logical.

Rather, it's a continuous and indefinite process.

No "end point."

Much like a "road trip", the "destination" becomes less important than the journey. It's about the experiences gleaned along the way. Enjoyment of the developments, the process. In the botanical-style aquarium, it's truly about a dynamic and ever-changing system. Every stage holds fascination.

Continuously.

An aquatic display is not a static entity, and will continue to encompass life, death, and everything in between for as long as it's in existence. There is no expiration date for our aquariums, unless we select one.

Take great comfort in that simple truth.

Stay grateful. Stay enthralled. Stay observant. Stay patient. Stay dedicated...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Great...Expectations?

By now, this whole idea of adding botanical materials to our aquariums for the purpose of helping create the physical, biological, and chemical environment of our aquariums is becoming way more familiar. Yet, no matter how many times you've created a botanical-influenced natural aquarium, the experience seems new and somehow different.

Expectations are funny things, aren't they?

There is something very pure and evocative-even a bit "uncomfortable" about utilizing botanical materials in the aquarium. Selecting, preparing, and utilizing them is more than just a practice- it's an experience. A journey. One which we can all take- and all benefit from.

Right along with our fishes, of course!

And yeah, it can even be seen as a bit of a spiritual journey, too- leading to some form of enlightenment and education about Nature, from a totally unique perspective.

The energy and creativity that you bring with you on the journey tends to become amplified during the experience. As you work with botanicals in your aquariums, your mind takes you to different places; new ideas for how your aquarium's microcosm can evolve start flooding your mind. Every tank- like every hobbyist- is different- and different inspirations arise. We don’t want everyone walking away feeling the same thing, quite the opposite actually.

That uniqueness is a large part of the experience.

The experience is largely about discovery. And today's piece is a bit about some of the interesting discoveries- expectations, and revelations that we as a community have learned along the way during our experiences working with botanicals in our aquariums.

Our aquariums evolve, as do the materials within them. We've discussed this concept many times, but it's one that we keep coming back to.

If we think of an aquarium as we do a natural aquatic ecosystem, it's certainly realistic to assume that some of the materials in the ecosystem will change, re-distribute, or completely decompose over time.

Botanicals are not "forever" aquascaping materials. We consider them ephemeral in nature. They will soften, break down, and otherwise decompose over time. Some materials, like leaves- particularly Catappa and Guava, will break down more rapidly than others, and if you're like our friend Jeff Senske of Aquaiuim Design Group, and like the look of intact leaves versus partially decomposed ones, you'll want to replace them more frequently; typically on the order of every three weeks or so, in order to have more-or-less "intact" leaves in your tank.

On the other hand, if you're like me, and enjoy the more natural look that occurs as the leaves break down, just keep 'em in. You may need to remove some materials if you find fungal growth, biofilm, or other growth unsightly or otherwise untenable, or if material gets caught up in filter inlets, etc. However, "operational concerns" aside, and if you've made that "mental shift" and can tolerate the stuff decomposing, just let them be and enjoy!

Botanicals like the really hard seed pods (Sterculia Pods", "Cariniana Pods", "Afzelia Pods"), etc., can last for many, many months, and generally will soften on their interiors long before any decomposition occurs on the exterior "shell" of he botanical. In fact, they'll typically recruit biofilms, which almost seem to serve as a sort of "protective cover" that preserves them.

Often times, fishes like Plecos, Otocinculus catfish, loaches, Headstanders, and bottom-dwelling fishes will rasp or pick at the decomposing botanicals, which further speeds up the process. Others, like Caridina shrimp, Apistos, characins, and others, will pick at biofilms covering the interior and exterior of various botanicals, as well as at the microfauna which live among them, just as they do in Nature.

Sometimes, the fishes will use botanical materials for a spawning site.

We receive a lot of questions about which botanicals will "tint the water the darkest" or whatever. Cool questions. Well, here's the deal: Virtually all botanical materials will impact the color of the water. You'll find, as we have, that different materials will impart different colors into the water. It will typically be clear, but with a golden, brownish, or perhaps a slight reddish tint.

The degree of tint imparted will be determined by various factors, such as how much of the materials you use in your tank, how long they were boiled and soaked during the preparation process, if you're using activated carbon or other chemical filter media, and how much water movement is in your system. However, rest assured, almost any botanical materials you submerge in your tank will impart some color to the water.

Unfortunately, since botanicals are natural materials, there is no "recipe'; no formula with a set "X number of leaves/pods per ___ gallons of aquarium capacity", and you'll have to use your judgement as to how much is too much! It's as much of an "art" as it is a "science!"

Now, If you really dislike the tinted water, but love the look of the botanicals you can mitigate some of this by employing a lmuch onger "post-boil" soaking period- like over a week. Keep changing the water in your soaking container daily, which will help eliminate some of the accumulating organics, as well as to help you to determine the length of time that you need to keep soaking the botanicals to minimize the tint.

Of course, it's far easier to simply employ chemical filtration media, such as activated carbon, and/or synthetic adsorbents such as Seachem Purigen, to help eliminate a good portion of the excess discoloration within the display aquarium where the botanicals will ultimately "reside."

Another interesting phenomenon about "living with your botanicals" is that they will "redistribute" throughout the aquarium. They're being moved around by both current and the activities of fishes, as well as during our maintenance activities, etc. This is, not surprisingly, very similar to what occurs in Nature, where various events carry materials like seed pods, branches, leaves, etc. to various locales within a given body of water.

In our opinion, this movement of materials, along with the natural and "assisted" decomposition that occurs, will contribute to a surprisingly dynamic environment!

Your aquarium water may appear turbid at various times. We are pretty comfortable with this idea; however, some of you may not be. As bacteria act to break down botanical materials, they may impart a bit of "cloudiness" into the the water. Also, materials such as lignin and good old terrestrial soils/silt find their way into our tanks at times.

Some of these inputs, such as soils- are intentional! Others are the unintended by-product of the materials we use, The look is definitely different than what we as aquarists have been indoctrinated to accept as "normal." One of my good friends, and a botanical-style aquarium freak, calls this phenomenon "flavor"- and we see it as an ultimate expression of a truly natural-looking aquarium.

Yeah, the water itself becomes part of the attraction. The color, the "texture", and the clarity of the water are as engrossing and fascinating as the materials which affect it. It's something that you either love or simply hate...everyone who ventures into this method of aquarium keeping needs to make their own determination of wether or not they like it.

Need a bit more convincing to embrace the charm of the water itself in botanical-style aquariums?

Simply look at a natural underwater habitat, such as an igapo or flooded varzea grassland, and see for yourself the allure of these dynamic habitats, and how they're ripe for replication in the aquarium. You'll understand how the terrestrial materials impact the now aquatic environment- the function AND the aesthetic-fundamental to the philosophy of the botanical-style aquarium.

Speaking of the impact of terrestrial materials on the aquatic habitat- remember, too, that just like in Nature, if new botanicals are added into the aquarium as others break down, you'll have more-or-less continuous influx of materials to help provide enrichment to the aquarium environment. This type of "renewal" creates a very dynamic, ever-changing physical environment, while helping keep water chemistry changes to a minimum.

This is the perfect analog to the concept of "allochthonous input" which occurs in wild aquatic habitats- materials from outside the aquatic environment- such as the surrounding forest- entering and influencing the aquatic environment.

The fishes in your system may ultimately display many interesting behaviors, such as foraging activities, territorial defense, and even spawning, as a result of this regular influx of "fresh" aquatic botanicals. You could even get pretty creative, and attempt to replicate seasonal "wet" and "dry" times by adding new materials at specified times throughout the year...The possibilities here are as diverse and interesting as the range of materials that we have to play with!

Go into this with the expectation that you might get to experience an entirely different way of looking at aquariums- and the natural environments we try to replicate- and you'll never be disappointed.

It's all a part of your "life with botanicals"- an ever-changing, always interesting dynamic that can impact your fishes in so many beneficial ways.

Stay dedicated. Stay excited. Stay engaged. Stay resourceful...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

It's about the microbiome...

As we've all started to figure out by now, our botanical-influenced aquariums are a lot more of a little slice of Nature that you're recreating in your home then they are just a "pet-holding container."

The botanical-style aquarium is a microcosm which depends upon botanical materials to impact the environment.

This microcosm consists of a myriad of life format all levels and all sizes, ranging from our fishes, to small crustaceans, worms, and countless microorganisms. These little guys, the bacteria and Paramecium and the like, comprise what is known as the "microbiome" of our aquariums.

A "microbiome", by definition, is defined as "...a community of microorganisms (such as bacteria, fungi, and viruses) that inhabit a particular environment." (according to Merriam-Webster)

Now, sure, every aquarium has a microbiome to a certain extent:

We have the beneficial bacteria which facilitate the nitrogen cycle, and play an indespensible role in the function of our little worlds. The botanical-style aquarium is no different; in fact, this is where I start wondering...It's the place where my basic high school and college elective-course biology falls away, and you get into more complex aspects of aquatic ecology in aquariums.

Yet, it's important to at least understand this concept as it can relate to aquariums. It's worth doing a bit of research and pondering. It'll educate you, challenge you, and make you a better overall aquarist. In this little blog, we can't possibly cover every aspect of this- but we can touch on a few broad points that are really fascinating and impactful.

So much of this proces-and our understanding starts with...botanicals.

With botanicals breaking down in the aquarium as a result of the growth of fungi and microorganisms, I can't help but wonder if they perform, to some extent, a role in the management-or enhancement-of the nitrogen cycle.

Yeah, you understand the nitrogen cycle, right?

How do botanicals impact this process? Or, more specifically, the microorganisms that they serve?

In other words, does having a bunch of leaves and other botanical materials in the aquarium foster a larger population of these valuable organisms, capable of processing organics- thus creating a more stable, robust biological filtration capacity in the aquarium?

I believe that they do.

With a matrix of materials present, do the bacteria (and their biofilms- as we've discussed a number of times here) have not only a "substrate" upon which to attach and colonize, but an "on board" food source which they can utilize as needed?

Facultative bacteria, adaptable organisms which can use either dissolved oxygen or oxygen obtained from food materials such as sulfate or nitrate ions, would also be capable of switching to fermentationor anaerobic respiration if oxygen is absent.

Hmm...fermentation.

Well, that's likely another topic for another time. Let's focus on some of the other more "practical" aspects of this "biome" thing.

Like...food production for our fishes.

In the case of our fave aquatic habitats, like streams, ponds, and inundated forests, epiphytes, like biofilms and fungal mats are abundant, and many fishes will spend large amounts of time foraging the "biocover" on tree trunks, branches, leaves, and other botanical materials.

The biocover consists of stuff like algae, biofilms, and fungi. It provides sustenance for a large number of fishes all types.

And of course, what happens in Nature also happens the aquarium- if we allow it to, right? And it can function in much the same way?

Yeah.

I am of the opinion that a botanical-style aquarium, complete with its decomposing leaves and seed pods, can serve as a sort of "buffet" for many fishes- even those who's primary food sources are known to be things like insects and worms and such. Detritus and the microorganisms within it can provide an excellent supplemental food source for our fishes!

Sustenence...from the microbiome.

It's well known that in many habitats, like inundated forests, etc., fishes will adjust their feeding strategies to utilize the available food sources at different times of the year, such as the "dry season", etc.

And it's also known that many fish fry feed actively on bacteria and fungi in these habitats...So I suggest once again that a botanical-style aquarium could be an excellent sort of "nursery" for many fish and shrimp species!

Again, it's that idea about the "functional aesthetics" of the, botanical-style aquariums. The idea which acknowledges the fact that the botanicals we use not only look cool, but they provide an important function (supplemental food production) as well. As we repeat constantly, the "look" is a collateral benefit of the function.

This is a profoundly important idea.

Perhaps arcane to some- but certainly not insignificant.

And of course, we've talked before about this "botanical nursery" concept- creating an aquarium for fish fry that has a large quantity of decomposing botanicals and leaves to foster the production of these materials, which serve as supplemental food for your fish fry. I have done this before myself and can attest to its viability. You fishes will have a constant supply of "natural" foods to supplement what you are feeding them in the early phases of their life.

Learn to make peace with your detritus! As always, look to the wild aquatic habitats of the world for an example of how this food source functions within the greater biome.

I'm fascinated by the "mental adjustments" that we need to make to accept the aesthetic and the processes of natural decay, fungal growth, the appearance of biofilms, and how these affect what's occurring in the aquarium. It's all a complex synergy of life and aesthetic.

And, in order to make the mental shifts which make this all work, we we have to accept Nature's input here.

Understand that, when we create a botanical-filled aquarium, not only do we have the opportunity to create an aquarium which differs significantly from those in years past- we have a unique window into the natural world and the role of these materials in the wild.

One thing that's very unique about the botanical-style approach is that we tend to accept the idea of decomposing materials accumulating in our systems. We understand that they act, to a certain extent, as "fuel" for the micro and macrofauna which reside in the aquarium, and that they perform this function as long as they are present in the system.

A profound mental shift...

And it's all about the microbiome. today's simple idea with enormous impact!

Stay curious. Stay thoughtful. Stay observant. Stay diligent...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

The Bloom.

It's not magic...It's Nature.

As anyone who ventures down our tinted road knows, one of the great "inevitable" of utilizing botanicals in our aquariums is the appearance of biofilms. You know, those scuzzy, nasty-looking threads of goo, which make their appearance in our tanks shortly after immersion of the botanicals (much to the chagrin of many).

Biofilm.

Even the word conjures up an image of something that you really don't want in your tank. Something dirty, yucky...potentially detrimental to your aquarium's health.

It's not.

However, let's be honest with ourselves here. The damn dictionary definition is not gonna win over many "haters":

We've long maintained that the appearance of biofilms and fungi on your botanicals and wood are to be celebrated- not feared. They represent a burgeoning emergence of life -albeit in one of its lowest and most unpleasant-looking forms- and that's a really big deal.

Biofilms form when bacteria adhere to surfaces in some form of watery environment and begin to excrete a slimy, gluelike substance, consisting of sugars and other substances, that can stick to all kinds of materials, such as- well- in our case, botanicals. It starts with a few bacteria, taking advantage of the abundant and comfy surface area that leaves, seed pods, and even driftwood offer.

The "early adapters" put out the "welcome mat" for other bacteria by providing more diverse adhesion sites, such as a matrix of sugars that holds the biofilm together. Since some bacteria species are incapable of attaching to a surface on their own, they often anchor themselves to the matrix or directly to their friends who arrived at the party first.

Tannin's creative Director, Johnny Ciotti, calls this period of time when the biofilms emerge, and your tank starts coming alive "The Bloom"- a most appropriate term, and one that conjures up a beautiful image of Nature unfolding in our aquariums- your miniature aquatic ecosystem blossoming before your very eyes!

The real positive takeaway here: Biofilms are really a sign that things are working right in your aquarium! A visual indicator that natural processes are at work, helping forge your tank's ecosystem.

I recently had a discussion with our friend, Alex Franqui (the guy who designs our cool enamel pins). His beautiful Igarape-themed aquairum pictured above, is starting to "bloom", with the biofilms and sediments working together to create a stunning, very natural look. Alex is a hardcore aquascaper, and to see him marveling and rejoicing in the "bloom" of biofilms in his tank is remarkable.

He gets it.

And it turns out that our love of biofilms is truly shared by some people who really appreciate them as food...Shrimp hobbyists! Yup, these people (you know who you are!) go out of their way to cultivate and embrace biofilms and fungi as a food source for their shrimp.

They get it.

And this makes perfect sense, because they are abundant in Nature, particularly in habitats where shrimp naturally occur, which are typically filled with botanical materials, fallen tree trunks, and decomposing leaves...a perfect haunt for biofilm and fungal growth!

Nature celebrates "The Bloom", too.

There is something truly remarkable about natural processes playing out in our own aquariums, as they have done for eons in the wild.

Remember, it's all part of the game with a botanical-influenced aquarium. Understanding, accepting, and celebrating "The Bloom" is all part of that "mental shift" towards accepting and appreciating a more truly natural-looking, natural-functioning aquarium. The "price of admission", if you will- along with the tinted water, decomposing leaves, etc., the metaphorical "dues" you pay, which ultimately go hand-in-hand with the envious "ohhs and ahhs" of other hobbyists who admire your completed aquarium when they see it for the first time.

.

The reality to us as "armchair biologists" is that the presence of these organisms in our aquariums is beautiful to us for so many reasons. It's not only a sign that our closed microcosms are functioning well, but that they are, in their own way, providing for the well- being of the inhabitants!

An abundance, created by "The Bloom."

The "mental stretches" that we ask you to make to accept these organisms and their appearance really require us to look at the wild habitats from which our fishes come, and reconcile that with our century-old aquarium hobby idealization of what Nature (and therefore our "natural" aquariums) actually look like.

Sure, it's not an easy stretch for most.

It's likely not everyone's idea of "attractive", and you'd no doubt freak out snobby contest judges with a tank full of biofilms and fungi, but to most of us, we should take great delight in knowing that we are providing our fishes with an extremely natural component of their ecosystem, the benefits of which have never really been studied in the aquarium in depth.

Why? Well, because we've been too busy looking for ways to remove the stuff instead of watching our fishes feed on it, and our aquatic environments benefit from its appearance!

We've had it all wrong, IMHO.

It's okay, we're starting to come around...

Welcome to Planet Earth.

Yet, there are always those doubts...and some are not willing to sit by and watch the "slime" take over...despite the fact that we know it's okay...

Celebrate "The Bloom."

Blurring the lines between Nature and the aquarium, from an aesthetic sense, at the very least- and in many respects, from a "functional" sense as well, proves just how far hobbyists have come...how good you are at what you do. And... how much more you can do when you turn to nature as an inspiration, and embrace it for what it is.

The same processes which occur on a grander scale in Nature also occur on a "micro-scale" in our aquariums. And we can understand and embrace these processes- rather than resist or even "revile" them- as an essential part of the aquatic environment.

Enjoy. Observe...Rejoice.

Celebrate "The Bloom."

Meet Nature where it is.

Stay excited. Stay bold. Stay inspired. Stay humble. Stay fascinated.

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Natural processes and the mental shifts we need to make...

We so often discuss natural processes and features in our aquarium work.

There are a lot of interesting pieces of information that we can interpret from Nature when planning, creating, and operating our aquariums. The idea of replicating natural processes and occurrences in the confines of our aquariums, by simply setting up the conditions necessary for them to occur is fundamental to our botanical-oriented approach.

It goes without saying that there are implications for both the biology and chemistry of the aquatic habitats when leaves and other botanical materials enter them. Many of these are things that we as hobbyists observe every day in our aquariums!

Example?

Well, let's talk about our old friend and sometimes nemesis, biofilm.

A lab study I came upon found out that, when leaves are saturated in water, biofilm is at its peak when other nutrients (i.e.; nitrate, phosphate, etc.) tested at their lowest limits. Hmm...This is interesting to me, because it seems that, in our botanical-style aquariums, biofilms tend to occur early on, when one would assume that these compounds are at their highest concentrations, right? And biofilms are essentially the byproduct of bacterial colonization, meaning that there must be a lot of "food" for the bacteria at some point if there is a lot of biofilm, right?

More questions...

Does this imply that the biofilms arrive on the scene and peak out really quickly; an indication that there is actually less nutrient in the water? Is the nutrient bound up in the biofilms? And when our fishes and other animals consume them, does this provide a significant source of sustenance for them? Can you have water with exceedingly low nutrient levels, while still having an abundant growth of biofilms?

Hmm...?

Oh, and here is another interesting observation: