- Continue Shopping

- Your Cart is Empty

What's the big deal about substrates?

Of all the fun topics in botanical-style aquarium keeping, few hold my interest as much as substrates.

I imagine the substrate as this magical place which fuels all sorts of processes within our aquariums, and that Nature tends to it in the most effective and judicious manner.

Yeah, I'm a bit of a "substrate romantic", I suppose.😆

Particularly in transitional habitats, like flooded forests, etc. the composition and characteristics of the substrate plays a huge role in the ecology of the aquatic habitat. The presence of a lot of soils, clays, and sediments in these substrates, as opposed to just sand, creates a habitat which provides a lot of opportunity for organisms to thrive.

The substrates are not just "the bottom."

They are diverse harbors of life, ranging from fungal and biofilm mats, to algae, to epiphytic plants. Decomposing leaves, seed pods, and tree branches compose the substrate for a complex web of life which helps the fishes we're so fascinated by to flourish. And, if you look at them objectively and carefully, they are beautiful.

Detritus ("Mulm") located in the sediments is the major source of energy and/or nutrients for many of these dynamic aquatic habitats. The bacteria which perform all the important chemical reactions, such as converting ammonia to nitrite, nitrates to nitrogen, releasing bound-up nutrients, neutralizing hydrogen sulfide, etc. will obtain essential nutrients from the detritus (this is what autotrophic bacteria that metabolize ammonia/ammonium or hydrogen sulfide for energy do).

These bacteria may also "harvest" those nutrients, as well as metabolize (aerobically or anaerobically) the organic compounds present in the detritus for energy, just like heterotrophs do.

The processing of nutrients in the aquarium is a fascinating one; a real "partnership" between a wide variety of aquatic organisms.

Yes, there is a lot of amazing biological function occurring in these layers. And of course, fostering this dynamic in the aquarium is one of the things we love the most. It's all part of our vision for the modern, botanical-style aquarium.

Now, hobbyists have played with deep sand beds and mixes of various materials in aquariums for many years, and knowledgable proponents of natural aquarium management, such as Diane Walstad, have discussed the merits of such features in far more detail, and with a competency that I could only dream of! That being said, I think the time has never been better to experiment with this stuff!

Again, we're talking about utilizing a wider variety of materials than just sand, so the dynamics are quite different, offering unique functions, processes, and potential benefits.

I've been thinking through further refinements of the "deep botanical bed"/sand substrate relationship. I've been spending a lot of time over the years researching natural aquatic systems and contemplating how we can translate some of this stuff into our closed system aquaria.

Before we talk about the actual substrate materials again, let's think about the processes that we would like to foster in a substrate, and the potential negatives that may be of concern to those of us who play with botanicals in our substrate configurations

One of the things that many hobbyists ponder when we contemplate creating deep, botanical-heavy substrates, consisting of leaves, sand, and other botanical materials is the buildup of hydrogen sulfide, CO2, and other undesirable compounds within the substrate.

Well, it does make sense that if you have a large amount of decomposing material in an aquarium, that some of these compounds are going to accumulate in heavily-"active" substrates. Now, the big "bogeyman" that we all seem to zero in on in our "sum of all fears" scenarios is hydrogen sulfide, which results from bacterial breakdown of organic matter in the total absence of oxygen.

Let's think about this for just a second.

In a botanical bed with materials placed on the substrate, or loosely mixed into the top layers, will it all "pack down" enough to the point where there is a complete lack of oxygen and we develop a significant amount of this reviled compound in our tanks? I think that we're more likely to see some oxygen in this layer of materials, and I can't help but speculate- and yeah, it IS just speculation- that actual de-nitirifcation (nitrate reduction), which lowers nitrates while producing free nitrogen, might actually be able to occur in a "deep botanical" bed.

And it's certainly possible to have denitrification without dangerous hydrogen sulfide levels. As long as even very small amounts of oxygen and nitrates can penetrate into the substrate, this will not become an issue for most systems. I have yet to see a botanical-style aquarium where the material has become so "compacted" as to appear to have no circulation whatsoever within the botanical layer.

Now, sure, I'm not a scientist, and I base this on close visual inspection of numerous aquariums, and the basic chemical tests I've run on my systems under a variety of circumstances. As one who has made it a point to keep my botanical-style aquariums in operation for very extended time frames, I think this is significant. The "bad" side effects we're talking about should manifest over these longer time frames...and they just haven't.

We need to look at substrates literally as an aquatic organism. And, like aggregations of organisms, they may be diverse, both morphologically and ecologically. They're a dynamic, functional part of the miniature ecosystems we create in our aquariums. We've used the "basic" stuff for a generation. It's time to open up our minds to a few new ideas. To rethink substrate. To reconsider why we incorporate substrate, and what we use.

What kinds of materials can we employ to create more "functional" substrates (which just happen to look cool, too?). What kinds of functions and benefits can we hope to recreate in the confines of our aquariums?

First off, think beyond just sands...or anything resembling "conventional" aquarium substrate. Think about what goes on in the benthic (bottom) regions in the natural habitats we love, and what benefits or support the materials which aggregate there provide for the organisms within the ecosystem.

Understand that the substrate is a dynamic, extremely important part of the aquarium, too. And what we construct our substrate with, and how we manage it, is of profound importance to our fishes!

Fostering fungal growth, as well as other microorganisms and small crustaceans, should be a huge component of the "why" we do this. These organisms, as we've discussed repeatedly, form a part of the "food chain" within our captive ecosystems, and offer huge benefits to the aquarium not only as potential supplemental nutrition for fishes, but as a means to process and export nutrients from within the botanical-style aquarium.

So, yeah, in summary- the substrate plays a huge role in the function of a botanical-style aquarium. We can create a "facility" with substrate materials which provides not only unique aesthetics- it provides priceless benefits: Production of supplemental nutrition for our fishes, and nutrient processing via a self-generating population of creatures that compliment, indeed, create the biodiversity in our systems on a more-or-less continuous basis.

True "functional aesthetics!"

A combination of finely crushed leaves, bits of botanicals, small twigs, etc. can form the basis for a more "biologically active" and even productive substrate. As these materials break down, they are colonized by fungi and biofilms, and impart tannins, lignin, and other sources of carbon into the water to fuel a variety of microbial growth.

As you might have gathered by now, we are an advocate of some rather "unconventional" substrate materials, particularly a classification what we call "Sedimented Substrates."

Yeah, that'd be ours. NatureBase "Igapo", "Varzea", and the upcoming "Mangal", "Floresta" and "Selagor", are examples of substrates which have a lot of sediments and clays in their formulation. These substrates realistically replicate the composition, function, and look of soils which are found in many tropical aquatic habitats.

In fact, most of our NatureBase substrates have a significant percentage of clays and sediments in their formulations. These materials have typically been something that aquarists have avoided, because they will cloud the water for a while, and often impart a bit of color. Like, that's a problem? We also have some botanical components in a few of our substrates, because they are intended to be "terrestrial" substrates for a while before being flooded...and when this stuff is first wetted, some of it will float. And that means that you're going to have to net it out, or let your filter take it out.

You simply won't have that "issue" with your typical bag of aquarium sand!

You can mix them with any of the above-mentioned commercially-available sands, or use them alone. You can gradually add water (as in our "Urban Igapo" concept), or simply fill your tank form day one. Expect significant cloudiness for several days as the materials settle out, though. Don't rinse these substrates...just put them to work right away.

Now, although you can (and should) play with these substrates "wet" from the start, I'd be remiss if I didn't remind you again that the igapo and varzea substrates were initially intended to be "terrestrial" for a period of time, to get the grasses and plants going, and then inundated.

So, yeah, you'll have to make a mental shift to appreciate a different look and function. And many hobbyists simply can't handle that. We've been up front with this stuff since these products were released, to ward off the, "I added NatureBase to my tank and it looks like a cloudy mess! This stuff is SHIT!" type of emails that inevitably come when people don't read up first before they purchase the stuff.

And the warning and mental shift indoctrinations have worked. No one has freaked out.

Instead, we're hearing how incredibly natural these aquariums look, and how the biological diversity and stability of these tanks are.

What goes on in an aquarium with sediments, botanicals- or leaves, in this instance as the total "substrate" or "hardscape", as the case may be, is that they become the basis for biological activity in the tank. As we have discussed a million times here, as botanicals break down, they recruit bacteria, fungi, and other organisms on their surfaces.

That's the "big deal" about substrates.

Mix it up. Play with sediments, crushed leaves, broken bits of botanicals..All sorts of natural "stuff" which would previously have been considered "dirty" and "bad for long term maintenance" in almost anyone's book. Look at the advantages that can be realized, instead of the potential risks involved in experimenting.

Open your mind up to accept the look and function- and the "aesthetic challenges" of using non-traditional materials in your substrates.

Stay creative. Stay excited. Stay bold. Stay studious...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Risk.

One of the toughest things in the aquarium hobby is to face the possibility of losing fishes. When you think about it, the idea of keeping live tropical fishes in an aquarium is pretty incredible to begin with. What we take on isn't necessarily "difficult" in many instances. The techniques have been known and shared in the hobby for generations. However, the awesome thing is that we are able to obtain and maintain these organisms in the first place, right?

And when you add into the equation that are completely responsible for creating essentially the entire environment in which they reside, it becomes even more incredible, right? What we do is pretty special.

However, unlike keeping many other animals as"pets", like dogs, cats, hamsters, rabbits, etc., we have the unique ability to create representations- functional and aesthetic-of the natural habitats from which they come. We can do all sorts of environmental manipulations, and embrace all sorts of evolutions within their aquariums to represent aspects of their natural habitats.

And this ability brings with it a lot of opportunity to innovate, as well as the assumption of some risk.

Yeah, the process of creating, optimizing and managing a specialized aquatic habitat is subject to risk, whether we expect it or not.

Risk.

The risk that we might not have acclimated our fishes correctly to the new environment that we have created. Risk that our management of the environment may not be be as controlled, consistent, or appropriate for the long-term health of the fishes.

This is not unique to the botanical-style aquarium, of course. It's something that we run into with all types of aquariums and fish-keeping endeavors, from the most basic goldfish bowl (arrghh!😂) to the most sophisticated reef aquarium system.

Risk permeates this hobby. It's something that is almost never discussed, but it is at the forefront of almost everything do. Risk abounds. We take risks every single time we purchase fish. And the responsibility to manage the risk- to mitigate any potential bad outcomes-lies squarely on our shoulders as hobbyists.

A classic, easy example? When repurchase that new fish, we immediately have to chose whether or not we will quarantine it before placing it into our tank. If we don't, we run the risk of introducing illness to our other healthy fishes. And, when we do quarantine (yay!),we STILL risk the possibility that the fish might not make it through. That it might not eat, or that a disease (the very reason you quarantine in the first place!) may manifest itself and possibly kill the fish in the quarantine system.

Risk.

When we first started Tannin Aquatics, the idea of utilizing seed pods, bark, leaves, branches and stuff in aquariums to manipulate the environmental conditions wasn't completely unknown. Hobbyists have been doing it for generations to some extent. However, when we embarked on our mission to curate, test, and ultimately introduce new and different botanical materials into the hobby, we know it was a risk.

Some might have proven to be toxic to fishes. Some might have been collected from polluted environments that had noxious chemicals. Some might have been intended for other purposes, and sold to us by unscrupulous suppliers, who had them treated with laquers or other industrial chemicals. We found this out the hard way a few times, killing fishes in our test tanks in the process.

Horrible to lose innocent animals, but part of the challenge we accepted when we intended to become leaders in this new arena. Releasing untested materials to fellow fish keepers and killing them was not an option. We had to assume the risk of testing ourselves. Vetting of suppliers was, and continues to be, crucial. Good quality source material doesn't guarantee success- but it does mitigate some of the risk.

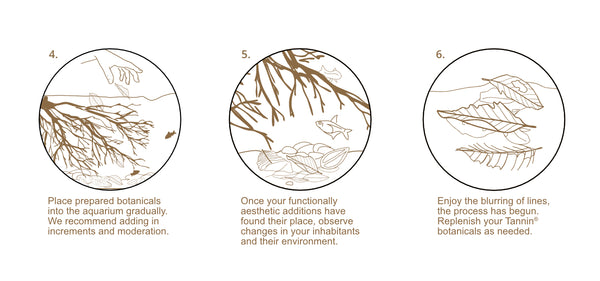

When we developed techniques for the preparation of botanicals for aquarium use, it was to help mitigate some of the risks that are inherent when you place natural terrestrial materials into a closed aquatic environment.

Yet, even with the development of "best practices" and recommended approaches and technique for safely utilizing botanicals in our aquariums, we knew that there was an even bigger, more ominous risk out there...Human nature.

Yes, when I started playing with botanicals in my aquariums almost two decades ago, I made a fair number of mistakes. Sometimes, they cost the lives of my fishes.

And killing fishes sucks.

Some mistakes were caused by my lack of familiarity with using various materials. Most were caused by not understanding fully the impact of adding botanical materials to a closed aquatic ecosystems. All were mitigated by taking the time to learn from them and honestly asses the good, the bad, and the practical aspects of using them in our aquariums.

And that meant developing "best practices" to help mitigate or eliminate issues as much as possible, even though the "practices" may not be the easiest, most convenient, or expedient way to proceed.

I KNEW that there would be people who might kill their fishes by adding lots of botanicals to their established systems without reading and following the instructions concerning preparation, cadence, and what to expect. I knew there would be people who would criticize the idea, "edit" the processes or recommended "best practices", talk negatively about the approach and generally scoff and downplay what they didn't know, understand, or do.

It's human nature whenever you give people something a bit different to play with...They want to go from 0-100 in like one day. And I knew that some of these people would go out on social media and attempt to trash the whole idea after they failed. This, despite all of our instructions, information, and pleas to follow the guidelines we suggested.

After more than six years of running Tannin, I have pretty much identified the two most common concerns we have for customers associated with utilizing botanicals in their aquariums. Curiously, our two biggest concerns revolve around our own human impatience and mindset- not the botanical materials themselves.

The first is... preparation.

We are often asked why we don't feel that you can, without exception, just give any of your botanicals "a quick rinse" and toss them into your aquarium.

After all, this is what happens in nature, right? Well, shit- yes...but remember, in most cases, there is a significant "dilution factor" caused by larger water volumes, currents, biologically-rich substrates, etc. that you encounter in natural aquatic systems. Even in smaller bodies of water, you have very "mature" nutrient export systems and biological equilibriums established over long periods of time which handle the influx and export of organic materials.

However, even in Nature, things go awry, and you will occasionally see bodies of water "fouled" by large, sudden influxes of materials (often leaves, grass clippings, etc.)- sometimes after rain or other weather events- and the result is usually polluted water, large algal blooms, and a pretty nasty smell!

In the aquarium, of course, you have a closed system with a typically much smaller water volume, limited import of fresh water, limited filtration (export) capacity, and in many cases, a less robust ecological microcosm to handle a large influx of nutrients quickly.

So you know where I'm going with this:

Fresh botanical materials, even relatively "clean" ones, are often still "dirty", from collection, storage, etc. They may have dust, airborne pollutants, soil or silt (depending upon where they were collected), even cobwebs, bird droppings, and dead insects (yuck!).

Natural materials accumulate "stuff." They're not sterile; made in some high tech "clean room" in a factory in Switzerland, right?

So," just giving botanicals a quick rinse" before tossing them in your tank is simply not good procedure, IMHO- even for stuff you collect from your own backyard. It's more risk to take on. At the very least, a prolonged (30 to 60 minute) steep in boiling hot water will serve to "sterilize" them to a certain extent. Follow it with a rinse to remove any lingering dirt or other materials trapped in the surfaces of your botanicals.

Now, I don't recommend this process simply because I want to be a pain in the ass. I recommend it because it's a responsible practice that, although seemingly "overkill" in some people's minds- increases the odds for a better outcome.

It reduces some of the risk.

The crew up in the cockpit on your flight from L.A. to New York know every system of the Boeing 737Max9 that they fly. But guess what? They still complete the pre-flight checklist each and every time they hop in the plane.

Because it can save lives.

Why should we be any different about taking the time to prepare botanicals? I know it sounds harsh; however, if you skip this step and kill your fishes- it's on you.

Period.

Why would you skip this, other than simply being impatient?

Could you get away with NOT doing this?

Sure. Absolutely. Many people likely do.

But for how long? When will it catch up with you? Maybe never...I know I'll get at least one email or comment from a hobbyist who absolutely doesn't do any of this and has a beautiful healthy tank with no problems.

Okay, good for you. I'm still going to recommend that, like I do- that you embrace a preparation process for every botanical item that you add to your aquariums.

Boiling/steeping also serves a secondary, yet equally important purpose: It helps soften and even break down the external tissues of the botanical, allowing it to leach out any remaining subsurface pollutants, sugars, or other undesirable organics to the greatest extent possible. And finally, it allows them to better absorb water, which makes them sink more easily when you place them in your aquarium.

Yes, it's an extra step.

Yes, it takes time.

However, like all good things in nature and aquariums, taking the time to go the extra mile is never a bad thing. And really, I'm trying to see what possible "benefit" you'd derive by skipping this preparation process?

Oh, let me help you: NONE.

None.

There is simply no advantage to rushing stuff.

Like all things we do in our aquariums, the preparation of materials that we add to them is a process, and Nature sets the pace. The fact that we may recommend 30 minutes or more of boiling is not of concern to Nature. It may take an hour or more to fully saturate your Sterculia Pods before they sink.

So be it.

Relax.

Savor the process. Enjoy every aspect of the experience. And don't you love the earthy scent that botanicals exude when you're preparing them?

And the shittiest thing? Even if you do all this prep, there is STILL risk that you will kill your fishes.

Yep.

Damn, I'm not ever gonna make it as salesman, huh?

How much to use?

Well, that's the million dollar question.

Who knows? Even that is a guess and decidedly unscientific at best!

It all gets back to the (IMHO) absurd "recommendations" that have been proffered by vendors over the years recommending using "x" number of leaves, for example, per gallon/liter of water. There are simply far, far too many variables- ranging from starting water chem to pH to alkalinity, and dozens of others- which can affect the "equation" and make specific numbers unreliable at best.

Now, nothing is perfect.

Nothing we can tell you is an absolute guarantee of perfect results...You're dealing with natural materials, and the results you'll see are governed by natural processes that we can only impact to a certain extent by preparation before use. But it's a logical, responsible process that you need to embrace for long-term success.

It reduces some of the risk.

And, when it comes time to adding your botanicals to your aquarium, the second "tier" of this process is to add them to your aquarium slowly. Like, don't add everything all at once, particularly to an established, stable aquarium. Think of botanicals as "bioload", which requires your bacterial/fungal/microcrusacean population to handle them.

Bacteria, in particular, are your first line of defense.

If you add a large quantity of any organic materials to an established system, you will simply overwhelm the existing beneficial bacterial population in the aquarium, which will likely result in a massive increase in ammonia, nitrite, and organic pollutants. At the very least, it will leave oxygen levels depleted, and fishes gasping at the surface as the bacteria population struggles to catch up to the large influx of materials.

This is not some sort of esoteric concept, right? I mean, we don't add 25 3-inch fishes at once to an established, stable 10-gallon aquarium and not expect some sort of negative environmental consequence, right? So why would adding bunch of leaves, botanicals, wood, or other materials containing organics be any different?

It wouldn't.

So please, PLEASE add botanicals to your established aquarium gradually, while observing your fishes' reactions and testing the water parameters regularly during and after the process. Take measured steps.

There is no rush.

There shouldn't be.

It's interesting how the process of selecting, preparing and adding botanical materials to our aquariums has evolved over the time since we've been in business. Initially, as I discussed previously, it was all about trying to discover what materials weren't "toxic" in some way!

Then, it was about figuring out ways to prepare them and make sure that they don't pollute the aquarium. Finally, it's been about taking the time to add them in a responsible, measured matter.

I think our biggest "struggle" in working with botanicals is a mental one that we have imposed upon ourselves over generations of aquarium keeping: The need to control our own natural desire to get stuff moving quickly; to hit that "done" thing...fast.

And the reality, as we've talked about hundreds of times here and elsewhere, is that there really is no "finished", and that the botanical-style aquarium is about evolution. This type of system embraces continuous change and requires us to understand the ephemeral nature of botanicals when immersed in water.

I know I may be a bit "blunt" when it comes to these topics of preparation, practices, and patience- but they are critical concepts for us to wrap our heads around and really embrace in order to be successful with this stuff. And they are absolutely tied to the idea of reducing risk to the greatest extent possible.

All caveats and warnings aside, the art and evolving "science" of utilizing natural botanical materials for the purpose of enriching and influencing the environment of the aquarium is an exciting one, promising benefits and breakthroughs that we may not have even thought about yet!

It's okay to experiment...If we are willing to accept the additional risk.

We stress these points over and over an over, because I get questions every day from hobbyists asking if they really need to prepare their botanicals, and if it's safe to use "_____" in their tanks, etc.

This is indicative, to me, of larger problem in the aquarium hobby.

In a world where people are supposedly not able to retain more than 280 characters of information, and where there is a apparently a "hack" for pretty much everything, I wonder if have we simply have lost the ability to absorb information on things that are not considered “relevant” to our immediate goal. I say this not in a sarcastic manner, but in a thoughtful, measured one.

I'm baffled by hobbyists who want to try something new and simply do next to no research or self-education prior to trying it.

Like, WTF?

When you read some of the posts on Facebook or other sites, where a hobbyist asks a question which makes it obvious that they failed to grasp even the most fundamental aspects of their "area of interest", yet jumped in head-first into this "new thing", it just makes you wonder! I mean, if the immediate goal is to have "...a great looking tank with botanicals...", it seems to me that some hobbyists apparently don’t want to take the time to learn the groundwork that it takes to get there and to sustain the system on a long-term basis.

I suppose that it’s far more interesting- and apparently, immediately gratifying- for some hobbyists to learn about what gadgets or products can get us where we want, and what fishes are available to complete the project quickly.

This is a bit of a problem. It demonstrates a fundamental impatience, an unwillingness to learn, and a lack of desire to assume some responsibility or risk. The desire to pass the responsibility on to someone- or something- else when shit goes wrong.

And the reality is that it's really all on us.

When it comes to using botanicals- or, for that matter, embarking upon any aquarium-related speacialties, it's really important to contemplate them from the standpoint of reducing and accepting some risk. We, as aquarium hobbyists, are 100% responsible for the lives of the animals under our care. If we don't like the idea of accepting this responsibility, then we should consider another hobby. Simple as that.

I can talk about the "best practices" in our hobby until my face turns green. I can point out the benefits of making mental shifts and being patient endlessly. However, it's up to each one of us to accept- or reject- these ideas, and to accept the outcomes-positive or negative- of our choices about how we embrace-or reject-this stuff.

And, based on what I'm seeing and hearing, a lot of hobbyists simply don't feel that this applies to them.

Okay, I’m sounding very cynical. And perhaps I am. But the evidence is out there in abundance…and it’s kind of discouraging at times.

Look, I’m not trying to be the self-appointed "guardian of the hobby." I’m not calling us out. I’m simply asking for us to look at this stuff realistically, however. To question our habits. To accept responsibility for our actions. No one has a right to tell anyone that what they are doing is not the right way, but we do have to instill upon the newbie the importance of understanding the basics of our craft.

I'm super-proud that we've consistently elevated realistic discussions about unpopular topics related to our hobby sector. Yeah, we literally have blog and podcast titles like, "How to Avoid Screwing Up Your Tank and Killing all of Your Fishes with Botanicals" , or "There Will be Decomposition", or "Celebrating The Slimy Stuff."

If we are worried about risk, we need to take as many steps as possible to understand it. To mitigate it. Some steps are tedious. Unglamorous. Time consuming. Not very fun.

However, they are all steps that we need take to create better outcomes, and to help advance the state of the art of the aquarium hobby- for the benefit of us all.

Risk is part of the hobby. How we accept it, and take it on, is also part of the hobby. It doesn't have to be a dark cloud hanging over everything that we do. Rather, it should be a motivator, an opportunity to improve, and a means to grow.

Stay responsible. Stay curious. Stay engaged. Stay observant...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Movement...

One of the things that drives most hobbyists crazy is when "stuff" gets blown around, covered or moved about in the aquarium. It can be because of strong current, the activity of fishes, or simply overgrown by plants. I understand the annoyance that many hobbyists feel; I recall this same aggravating feeling in many reef tanks where I had high flow and sand on the bottom- almost always a combination for annoyance!

I mean, I get it. We have what feel is a carefully thought-out aquascape, looking exactly how we expected it would after setup. Yet, despite our ideas and thoughts, stuff moves around in the aquarium. It's something we can either accept, or modify in our aquariums, depending upon our preferences.

Yet, movement and "covering" of various materials by sediments, biofilms, etc., which accumulate on the substrate in natural habitats are everyday occurrences, and they help forge a very dynamic ecosystem. And they are constantly creating new opportunities for the fishes which reside in them to exploit.

When you think about how materials "get around" in the wild aquatic habitats, there are a few factors which influence both the accumulation and distribution of them. In many topical streams, the water depth and intensity of the flow changes during periods of rain and runoff, creating significant re-distribution of the materials which accumulate on the bottom, such as leaves, branches, seed pods, and the like.

Larger, more "hefty" materials, such as branches, submerged logs, etc., will tend to move less frequently, and in many instances, they'll remain stationary, providing a physical diversion for water as substrate materials accumulate around them.

A "dam", of sorts, if you will.

And this creates known structures within streams in areas like Amazonia, which are known to have existed for many years. Semi-permanent aquatic features within the streams, which influence not only the physical and chemical environment, but the very habits and abundance of the fishes which reside there.

Most of the small stuff, like leaves, tend to move around quite a bit... One might say that the "material changes" created by this movement of materials can have significant implications for fishes. As we've talked about before, they follow the food, often existing in, and subsisting off of what they can find in these areas.

New accumulations of leaves, detritus, and other materials benefit the entire ecosystem.

In the case of our aquariums, this "redistribution" of material can create interesting opportunities to not only switch up the aesthetics of our tanks, but to provide new and unique little physical areas for many of the fishes we keep.

And yeah, the creation of new feeding opportunities for life forms at all levels is a positive which simply cannot be overstated! As hobbyists, we tend to lament changes to the aquascape of our tanks caused by things outside of our control, and consider them to be a huge inconvenience, when in reality, they're not only facsimile of very natural dynamic processes-they are fundamental to their evolution.

The benthic microfauna which our fishes tend to feed on also are affected by this phenomenon, and as mentioned above, the fishes tend to "follow the food", making this a case of the fishes adapting to a changing environment. And perhaps...maybe...the idea of fishes sort of having to constantly adjust to a changing physical environment could be some sort of "trigger", hidden deep in their genetic code, that perhaps stimulates overall health, immunity or spawning?

Something in their "programing" that says, "You're at home..." Perhaps something which triggers specific adaptive behaviors?

I find this possibility fascinating, because we can learn more about our fishes' behaviors, and create really interesting habitats for them simply by adding botanicals to our aquariums and allowing them to "do their own thing"- to break apart as they decompose, move about as we change water or conduct maintenance activities, or add new pieces from time to time.

Again, just like Nature.

We just need to "get over ourselves" on this aesthetic thing!

Another mental shift? Yeah, it is. An easy one, but one that we need make, really.

Like any environment, botanical/ leaf litter beds have their own "rhythm", fostering substantial communities of fishes. The dynamic behind this biotope can best be summarized in this interesting excerpt from an academic paper on blackwater leaf-litter communities by biologist Peter Alan Henderson, that is useful for those of us attempting to replicate these communities in our aquaria:

"..life within the litter is not a crowded, chaotic scramble for space and food. Each species occupies a sub-region defined by physical variables such as flow and oxygen content, water depth, litter depth and particle size…

...this subtle subdivision of space is the key to understanding the maintenance of diversity. While subdivision of time is also evident with, for example, gymnotids hunting by night and cichlids hunting by day, this is only possible when each species has its space within which to hide.”

In other words, different species inhabit different sections of the leaf litter beds. As aquarists, we should consider this when creating and stocking our botanical-style aquariums.

It just makes sense, right?

So, when you're attempting to replicate such an environment, consider how the fishes would utilize each of the materials you're working with. For example, leaf litter areas would be an idea shelter for many juvenile fishes, catfishes, and even young cichlids to shelter among.

Submerged branches, larger seed pods and other botanicals provide territory and areas where fishes can forage for macrophytes (algal growths which occur on the surfaces of these materials). Fish selection can be influenced as much by the materials you're using to 'scape the tank as anything else, when you think about it!

And it's not just fishes, of course. It's a multitude of life forms.

There are numerous life forms which are found on ad among these materials as well, such as fungal growths, bacterial biofilms, etc. which we likely never really consider, yet are found in abundance in nature and in the aquarium, and perform vital roles in the function of the aquatic habitat.

Perhaps most fascinating and rarely discussed in the hobby, are the unique freshwater sponges, from the genus Spongilla. Yes, you heard. Freshwater sponges! These interesting life forms attach themselves to rocks and logs and filter the water for various small aquatic organisms, like bacteria, protozoa, and other minute aquatic life forms. Some are truly incredible looking organisms!

(Spongilla lacustris Image by Kirt Onthank. Used under CC-BY SA 3.0)

Unlike the better-known marine sponges, freshwater sponges are subjected to the more variable environment of rivers and streams, and have adapted a strategy of survival. When conditions deteriorate, the organisms create "buds", known as "gemmules", which are an asexually reproduced mass of cells capable of developing into a new sponge! The Gemmules remain dormant until environmental conditions permit them to develop once again!

Oh, cool!

To my knowledge, these organisms have never been intentionally collected for aquariums, and I suspect they are a little tricky to transport (despite their adaptability), just ike their marine cousins are. One species, Metania reticulata, is extremely common in the Brazilian Amazon. They are found on rocks, submerged branches, and even tree trunks when these areas are submerged, and remain in a dormant phase in the aforementioned gemmules during periods of desiccation!

Now, I'm not suggesting that we go and collect freshwater sponges for aquarium use, but I am curious if they occur as "hitchhikers" on driftwood, rocks or other materials which end up in our aquariums. When you think about how important sponges are as natural "filters", one can only wonder how they might perform this beneficial role in the aquarium as well!

We've encountered them in reef tanks for many years...I wonder if they could ultimately find their way into our botanical-style aquariums as well? Perhaps they already have. Have any of you encountered one before in your tanks?

The big takeaway from all of this: A botanical bed in our aquariums and in Nature is a physical structure, ephemeral though it may be- which functions just like an aggregation of branches, or a reef, rock piles, or other features would in the wild benthic environment, although perhaps even "looser" and more dynamic.

Stuff gets redistributed, covered, and often breaks down over time. Exactly like what happens in Nature.

Think about the possibilities which are out there, under every leaf. Every sunken branch. Every root. Every rock.

It's all brought about by the dynamic process of movement.

Perhaps instead of looking at the movement of stuff in our tanks as an annoyance, we might enjoy it a lot more if we look at it as an opportunity! An opportunity to learn more about the behaviors and life styles of our fishes and their ever-changing environment.

Stay observant. Stay creative. Stay excited. Stay open-minded...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

The slow(er) road to success with fish stocking...

One of the questions which we are asked less and less these days is, 'What kinds of fishes are suitable for a botanical-style aquarium?" I think that after 6 years of pounding all of these ideas into your heads about all of the strange nuances of botanical-style aquariums, it's almost universally understood that pretty much any fishes can live in them.

On the other hand, when it comes to how we stock our tanks, nothing has really changed...however, it could. And it should, IMHO.

We spend a pretty good amount of time studying, scheming, and pondering how to create a compatible, interesting, and attractive community of fishes within our aquariums.

It's probably among the most enjoyable things that we do in the hobby, right?

As a somewhat eccentric philosopher of all things fish, one of my favorite things to ponder is stuff that we do while creating our aquariums which is- intentionally or otherwise- analogous to the factors in Nature that result in the environments and fish populations that we find so compelling.

If you're like me, you likely spend a little too much time pondering all sorts of arcane aspects of the hobby...Okay, so maybe you're NOT like me, but you probably have a rather keen interest in the way Nature operates in the wild aquatic systems of the world, and stock your aquariums accordingly.

As one who studies a lot of details about some of the habitats from which our fishes come, I can't help but occasionally wonder exactly what it is that brings fishes to a given location or niche within a environment?

Now, the first answer we're likely to proffer is the most apparent...right? I mean, they follow the food!

Fishes tend to move into new areas in search suitable food sources as part of their life cycle. And food sources often become available in habitats such as flooded forest areas after the rains come, when decomposing leaves and botanical materials begin to create (or re-activate, as the case may be) "food webs", attracting ever more complex life forms into the area.

When we create our aquariums, we take into consideration a lot of factors, ranging from the temperament and size of our fish selections, to their appearance, right? These are all important factors. However, have you ever considered what the factors are in nature which affect the composition of a fish community in a given habitat?

Like, why "x" fish is living in a particular habitat?

What adaptations has the fish made that make it uniquely suitable for this environmental niche? Further, have you thought about how we as hobbyists replicate, to some extent, the actual selection processes which occur in Nature in our quest to create the perfect community aquarium?

Now, if you're an African Cichlid lover or reef hobbyist, I'm sure you have!

Social hierarchies, spatial orientations, and allopathic processes are vital to success in those types of aquariums; you typically can't get away with just throwing in a random fish or coral and hoping it will just mix perfectly.

However, for many hobbyists who aim to construct simple "community tanks", it isn't that vital to fill specific niches and such...we probably move other factors to the forefront when thinking about possible additions to our community of fishes: Like, how cool the fish looks, how large it grows, if it has a peaceful temperament, etc. More basic stuff.

However, in the end, we almost always make selections based upon factors which we deem important...again, a sort of near-mimicry of natural processes- and how the fishes work in the habitat we've created for them.

"Unnatural selection?" Or...Is it essentially what nature's does for eons?

Oh, and what exactly is an "aquatic habitat", by the way? In short, you could say that an aquatic habitat is the physical, chemical, and biological characteristics which determine the suitability for habitation and reproduction of fishes.

Of course, these characteristics can determine which fishes are found in a given area in the wild- pretty much without exception. It's been happening for eons.

Approaching the stocking of an aquarium by determining which fishes would be appropriate for the physical characteristics of the tank is not exactly groundbreaking stuff.

However, when we evaluate this in the context of "theme", and what fish would be found within, say, an Amazonian Igarape stream or a Southeast Asian peat swamp, the idea of adding fishes to "exploit" the features of the habitat we've created is remarkably similar to the processes which occur in Nature that determine what fish are found there, and it's the ultimate expression of good tank planning, IMHO.

It's just kind of interesting to think about in that context, right?

Competition is another one of the important factors in determining how fish populations in the wild. Specifically, competition for space, resources (e.g.; food) and mates are prevalent. In our aquariums, we do see this to some extent, right? The "alpha male" cichlid, the Pleco that gets the best cave, and the Tetra which dominates his shoal.

How we create the physical space for our fishes can have significant impact on this behavior. When good hiding spaces are at a premium, as are available spawning partners, their will be some form of social hierarchy, right?

Other environmental factors, such as water movement, dissolved oxygen, etc. are perhaps less impactful on our community once the tank is established. However, these factors figure prominently in our decisions about the composition of, or numbers or fishes in the community, don't they?

For example, you're unlikely to keep Hillstream loaches in a near stagnant, blackwater swamp biotope aquarium, just like you'd be unlikely to keep Altum Angelfish in a fast-moving stream biotope representation. And fishes which shoal or school will, obviously, best be kept in numbers.

"Aquarium Keeping 101", again.

One factor that we typically don't have in our aquaria is predation. I know very few aquarists who would be sadistic enough to even contemplate trying to keep predators and prey in the same tank, to let them "have at it" and see what happens, and who comes out on top!

I mean, there is a lot to this stuff, isn't there?

Again, the idea of creating a tank to serve the needs of certain fishes isn't earth-shattering. Yet, the idea of stocking the tank based on the available niches and physical characteristics is kind of a cool, educational, and ultimately very gratifying process. I just think it's truly amazing that we're able to actually do this these days.

And the sequence that you stock your tank in is extremely pertinent.

I think that you could literally create a sort of "sequence" to stocking various types of fishes based on the stage of "evolution" that your aquarium is in, although the sequence might be a bit different than Nature in some cases. For example, in a more-or-less brand new aquarium, analogous in this case to a newly-inundated forest floor, their might be a lot less in the way of lower life forms, such as fungi and bacteria, until the materials begin breaking down. You'd simply have an aggregation of fresh leaves, twigs, seed pods, soils, etc. in the habitat.

So, if anything, you're likely to see fishes which are much more dependent upon allochthonous input...food from the terrestrial environment. This is a compelling way to stock an aquarium, I think. Especially aquarium systems like ours which make use of these materials en masse.

Right from the start (after cycling, of course!), it would not be unrealistic to add fishes which feed on terrestrial fruits and botanical materials, such as Colossoma, Arowanna, Metynis, etc. Fishes which, for most aquarists of course, are utterly impractical to keep because of their large adult size and/or need for physical space!

(Pacu! Image by Rufus46, used under CC BY-SA 3.0)

Now, a lot of smaller, more "aquarium suited" fishes will also pick at these fruits and seeds, so you're not totally stuck with the big brutes if you want to go this route! Interestingly, the consumption and elimination of fruits by fishes is thought to be a major factor in the distribution of many plants in the region.

Do a little research here and you might be quite surprised about who consumes what in these habitats!

More realistically for most aquarists, I'd think that you could easily stock first with fishes like surface-dwelling (or near surface-dwelling) species, like hatchetfishes and some Pencilfishes, which are largely dependent upon terrestrial insects such as flies and ants, in Nature. In other words, they tend to "forage" or "graze" little, and are more opportunistic, taking advantage of careless insects which end up in the water of these newly-inundated environs.

I've read studies where almost 100 species were documented which feed near-exclusively on insects and arthropods from terrestrial sources in these habitats! As I mention often, if you dive a bit deeper than the typical hobbyist writings, and venture into scholarly materials and species descriptions, you'll be fascinated to read about the gut-content analysis of fishes, because they give you a tremendous insight about what to feed in the aquarium!

Continuing on, it's easy to see that, as the environments evolve, so does the fish population. And the possibilities for simulating this in the aquarium are many and are quite interesting!

Later, as materials start to decompose and are acted on by fungi and bacteria, you could conceivably add more of the "grazing" type fishes, such as Plecos, small Corydoras, Headstanders, etc.

As the tank ages and breaks in more, this would be analogous to the period of time when micro-crustaceans and aquatic insects are present in greater numbers, and you'd be inclined to see more of the "micropredators" like characins, and ultimately, small cichlids.

Interestingly, scientists have postulated that evolution favored small fishes like characins in these environments, because they are more efficient at capturing small terrestrial insects and spiders in these flooded forests than the larger fishes are!

And it makes a lot of sense, if you look at it strictly from a "density/variety" standpoint- lots of characins call these habitats home!

Then there are detritivores.

The detrivorus fishes remove large quantities of this material from submerged trees, branches, etc. Now, you might be surprised to learn that, in the wild, the gut-content analysis of almost every fish indicates that they consume organic detritus to some extent! And it makes sense...They work with the food sources that are available to them!

At different times of the year, different food sources are easier to obtain.

And, of course, all of the fishes which live in these habitats contribute to the surrounding forests by "recycling" nutrients locked up in the detritus. This is thought by ecologists to be especially important in blackwater inundated forests and meadows in areas like The Pantanal, because of the long periods of inundation and the nutrient-poor soils as a result of the slow decomposition rates.

All of this is actually very easy to replicate, to a certain extent, when stocking our aquaria. Why would you stock in this sort of sequence, when you're likely not relying on decomposing botanicals and leaves and the fungal and microbial life associated with them as your primary food source?

Well, you likely wouldn't be...However, what about the way that the fishes, when introduced at the appropriate "phase" in the tank's life cycle- adapt to the tank? Wouldn't the fishes take advantage of these materials as a supplement to the prepared foods that you're feeding them? Doesn't this impact the fishes' genetic "programming" in some fashion? Can it activate some health benefits, behaviors, etc?

I believe that it can. And I believe that this type of more natural feeding ca profoundly and positively impact our fishes' health.

I’m no genius, trust me. I don’t have half the skills many of you do but I have succeeded with many delicate “hard-to-feed” fishes over my hobby “career.”

Why?

Because I'm really patient.

Success with this approach is simply a result of deploying "radical patience." The practice of just moving really slowly and carefully when adding fishes to new tanks.

It's a really simple concept.

The hard part is waiting longer to add fishes.

Wait a minimum of three weeks—and even up to a month or two if you can stand it, and you will have a surprisingly large population of micro and macro fauna upon which your fishes can forage between feedings.

Having a “pre-stocked” system helps reduce a considerable amount of stress for new inhabitants, particularly for wild fishes, or fishes that have reputations as “delicate” feeders.

And think about it. This is really a natural analog of sorts. Fishes that live in inundated forest floors (yeah, the igapo again!) return to these areas to "follow the food" once they flood.

It just takes a few weeks, really. You’ll see fungal growth. You'll see some breakdown of the botanicals brought on by bacterial action or the feeding habits of small crustaceans and fungi. If you "pre-stock", you might even see the emergence of a significant population of copepods, amphipods, and other creatures crawling about, free from fishy predators, foraging on algae and detritus, and happily reproducing in your tank.

We kind of know this already, though- right?

This is really analogous to the tried-and-true practice of cultivating some turf algae on rocks either in or from outside your tank before adding herbivorous, grazing fishes, to give them some "grazing material."

Radical patience yields impressive results.

It’s not always easy to try something a little out of the ordinary, or a bit against the grain of popular practice, but I commend you for even thinking about the idea. At the very least, it may give you pause to how you stock your tank in the future, like "Herbivores first, micro predators last", or whatever thought you subscribe to.

Allow your system to mature and develop at least some populations of fauna for these fishes to supplement their diets with. You’ll develop a whole new appreciation for how an aquarium evolves when you take this long, but very cool road.

Stay patient. Stay observant. Stay creative. Stay studious. Stay resourceful...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Letting go...

So, you have this idea for an aquarium.

You kind of see it in your head...you've assembled the materials, got it sort of together.

You add water.

Then, you walk in the room one day, look at it and- you just HATE it.

Like, you're done with it. Like, no re-hab on the design. No "tweaking" of the wood or whatever...You're just over the fucking thing. Ever felt that?

What do you do?

Well, I had this idea for a nano tank a while back. It seemed good in my head...I had it up for a nanosecond.

Even memorialized it with some Instagram Stories posts. Doing that is almost always the sort of thing that forces me to move on something...I mean, if you lay down a public "marker", you've got to go, right?

I thought that the tank would be a sort of "blank canvas" for an idea I had...I liked the idea, in principle.

But I didn't see a way forward with this one. I even took the extraordinary step of removing one element of the tank (the wood) altogether, in the hope of perhaps pivoting and just doing my "leaf only scape V3.0"- but I wasn't feeling it.

Nope.

A stillborn idea. A tank not capable of evolving to anything that interested me at this time.

So...I let it go.

Yeah, made away with it. Shut it down. Terminated it...

Whatever you want to call it.

That's really a kind of extraordinary step for me. I mean, I'm sort of the eternal optimist. I try to make almost everything work if I can...

I mean, some of my favorite tanks evolved out of this mindset of sticking with something...We'll come back to that in bit.

Not this time, however.

I killed it.

Now, in the hours after the aborted aquarium move, I was actually able to gain some clarity about why I did it.

What made me do it?

I almost always do a sort of "post mortem" analysis when I abort on an idea, and this time was no different. It was pretty obvious to me...the "writing was on the wall" with this one!

I think it centered around two things that I simply can't handle in aquariums anymore.

Don't laugh:

1) I absolutely can't stand aquariums which don't have some sort of background- be it opaque window tint, photo paper, or paint. This tank had no background. You could see the window behind it, and the trees outside on the street, and...yeah.

2) I disdain seeing filters or other equipment in my aquariums. Like, I hate it more than you can ever even imagine. With really few exceptions, I simply hate seeing filters and stuff. It's only in recent years that I've been able to tolerate seeing filter returns in my all-in-one tanks...and just barely. Now, this nano had a little hang-on-the-back outside power filter...Which I not only saw from the top, but from behind...because-you got it- I didn't have a goddam background on the tank, yes.

I mean, am I that much of a primadonna that I can't handle that? I mean, maybe, but I like to think of it as a situation where I have simply developed an aesthetic sense that just can't tolerate some stuff anymore. I have good ideas, and then I get to equipment...and it sort of "stifles" them a bit.

This is weird.

Okay, yeah, maybe I am prima donna.

What could I have done to salvage this tank? Add a background?

Use a canister filter and glassware, you say?

Oh, sure. That's easy, right? I mean, all you see in the tank are these elegant curves of "lily pipes" and intakes...Maybe a surface skimmer...You just take 'em out and bleach 'em every once in a while and they stay nice and clean, and..

Okay, yeah. Great. On paper, anyways.

IMHO, glassware isn't the "organic art" that everyone seems to place on some lofty pedestal in the hobby. It reminds me of high school chemistry lab (which I think I got a C minus in, so some residual trauma there, no doubt). You think it's beautiful...I think it's simply dreadful.

It's another piece of equipment, which you see on the outside of the tank, too, with its "umbilical" of return lines shooting up along the sides. Now sure, I know these were developed to make an obvious, visible necessity (filter returns) more elegant and beautiful...However, to me, they're just that- obvious, visible, distracting...and ugly.

Hell, I've even made crazy efforts to hide the canister filters beneath my tanks before, when I couldn't hide them within the tank. It's like, I had to do something!

I know, I'm being waaaaay too stupid about this.

Because, really, with a lot of my reef aquarium work, and for that matter, some of my fave botanical-style tanks, you can see some of this stuff. When you see my next reef tank, you might see couple of submersible pumps in the tank , low and deep behind the rock work.

Yeah.

For some reason, it doesn't completely fry my brain in every single situation. I suppose it's a hypocritical thing, but man, sometimes it freaks me out and sometimes I can give it a pass.

Weird, huh?

Like, why do some tanks get a pass, and others just freak me out with this stuff.

I think, maybe, it's about the "concept"of the tank. Or the context. Like, some of my fave ever tanks, like my leaf-litter-only tanks, typically will have some equipment evident, because they are essentially a "zero-releaf" aquascape, with nothing that you can hide this stuff behind, like wood or rocks, or whatever. It's as "honest" as it gets. If you want to filter and heat the tank, you only have few options.

It never bothered me all that much in those types of tanks.

Yet, in other tanks? Just fugettaboutit!

Yeah, it MUST be about the concept of the tank. Not only will I forgive the visible equipment, sometimes I'll forgive myself the entire poor execution, too. Because, when I look back at some of the stuff I've done, that was definitely the mindset. Like, I was just happy to sort of pull it off, despite how crappy it looked, as this little gem from 2004 graphically illustrates:

Now that I look back on it, there were actually tons of times when I just let a tank evolve, unmolested and unhurried, because something spoke to me...no matter how weird or seemingly dumb the concept may have initially appeared. There was something about it that I believed in...

And occasionally, I'll try something, tear it down, and just regret it. Like, I'll realize, too late, that there was something I liked about the idea, and that I should have kept at it; let it do it's thing.

Like, what IF I kept it in play for little longer?

I mean, could it have evolved into something cool?

Maybe.

I recall a particular experiment I did with Spider Wood, which I let go very early in the game. The arrangement was almost a "reef like" concept...It didn't look right at the time, so I killed it way too early.

Like, a few tweaks to the wood stack, a buildup of substrate in the back of it, a buildup of some leaves and maybe some plants in the back, and it could have been a respectable recreation of the banks of some of the forest floor streams that I've seen in South America.

Yeah, I'd love to try that one again.

Then there were others which I had great faith in right from the start. Even though they looked a bit weird initially, I knew that they'd evolve into something special if I let them be.

Some just hit the right note, despite a possibly shaky start. Just knew that the idea was so special, that given the space and time, they'd eventually hit the right notes...And they did.

And, then, there were those ideas which, despite their unconventional appearance, were iconic to me, because they represented the culmination of although experiment; a transformation from research to idea to reality. Stuff which created a real transformation in the way I look at aquariums. The "Urban Igapo" style aquairums that many of us execute now, arose from just such an idea.

Sometimes, you just know it. You just feel that letting go of your preconceptions, doubts, and fears, rather than letting go of the tank-is just the right move.

Regardless of the idea, or the appearance of your tank, if there is any way to salvage what you feel is a great idea- even if it means just waiting it out for awhile- do it.

You just never know if that one "not so good"idea will turn out to be the one that changes everything for you, and inspires others in the process. Your "fail" might be the unlock- the key- for someone else who was about give up, and then suddenly saw something in your work, and created a tank based on your "failed" concept- executed on an idea-which truly touched others in ways you might not have even thought of.

So, yeah- let go...in the right way.

Stay bold. Stay patient. Stay creative. Stay optimistic. Stay enthusiastic. Stay persistent...

And Stay Wet.

The Botanical-Style Aquarium: A "filter" of its own, and other biological musings...

A big thought about our botanical-style aquariums:

The aquarium-or, more specifically- the botanical materials which comprise the botanical-style aquarium "infrastructure" acts as a biological "filter system."

In other words, the botanical materials present in our systems provide enormous surface area upon which beneficial bacterial biofilms and fungal growths can colonize. These life forms utilize the organic compounds present in the water as a nutritional source.

Oh, the part about the biofilms and fungal growths sounds familiar, doesn't it?

Let's talk about our buddies, the biofilms, just a bit more. One more time. Because nothing seems as contrary to many hobbyists than to sing the praises of these gooey-looking strands of bacterial goodness!

Structurally, biofilms are surprisingly strong structures, which offer their colonial members "on-board" nutritional sources, exchange of metabolites, protection, and cellular communication. They form extremely rapidly on just about any hard surface that is submerged in water.

When I see aquarium work in which biofilms are considered a "nuisance", and suggestions that it can be eliminated by "reducing nutrients" in the aquarium, I usually cringe. Mainly, because no matter what you do, biofilms are ubiquitous, and always present in our aquariums. We may not see the famous long, stringy "snot" of our nightmares, but the reality is that they're present in our tanks regardless.

The other reality is that biofilms are something that we as aquarists typically fear because of the way they look. In and of themselves, biofilms are not harmful to our fishes. They function not only as a means to sequester and process nutrients ( a "filter" of sorts?), they also represent a beneficial food source for fishes.

Now, look, I can see rare scenarios where massive amounts of biofilms (relative to the water volume of the aquarium) can consume significant quantities of oxygen and be problematic for the fishes which reside in your tank. These explosions in biofilm growth are usually the result of adding too much botanical material too quickly to the aquarium. They're excaserbated by insufficient oxygenation/circulation within the aquarium.

These are very unusual circumstances, resulting from a combination of missteps by the aquarist.

Typically, however, biofilms are far more beneficial that they are reven emotely detrimental to our aquariums.

Nutrients in the water column, even when in low concentrations, are delivered to the biofilm through the complex system of water channels, where they are adsorbed into the biofilm matrix, where they become available to the individual cells. Some biologists feel that this efficient method of gathering energy might be a major evolutionary advantage for biofilms which live in particularly in turbulent ecosystems, like streams, (or aquariums, right?) with significant flow, where nutrient concentrations are typically lower and quite widely dispersed.

Biofilms have been used successfully in water/wastewater treatment for well over 100 years! In such filtration systems the filter medium (typically, sand) offers a tremendous amount of surface area for the microbes to attach to, and to feed upon the organic material in the water being treated. The formation of biofilms upon the "media" consume the undesirable organics in the water, effectively "filtering" it!

Biofilm acts as an adsorbent layer, in which organic materials and other nutrients are concentrated from the water column. As you might suspect, higher nutrient concentrations tend to produce biofilms that are thicker and denser than those grown in low nutrient concentrations.

Those biofilms which grow in higher flow environments, like streams, rivers, or areas exposed to wave action, tend to be denser in their morphology. These biofilms tend to form long, stringy filaments or "streamers",which point in the direction of the flow. These biofilms are characterized by characteristic known as "viscoelasticity." This means that they are flexible, and stretch out significantly in higher flow rate environments, and contract once again when the velocity of the flow is reduced.

Okay, that's probably way more than you want to know about the physiology of biofilms! Regardless, it's important for us as botanical-style aquarists to have at least a rudimentary understanding of these often misunderstood, incredibly useful, and entirely under-appreciated life forms.

And the whole idea of facilitating a microbiome in our aquariums is predicated upon supplying a quantity of botanical materials- specifically, leaf litter, for the beneficial organisms to colonize and begin the decomposition process. An interesting study I found by Mehering, et. al (2014) on the nutrient sequestration caused by leaf litter yielded this interesting little passage:

"During leaf litter decomposition, microbial biomass and accumulated inorganic materials immobilize and retain nutrients, and therefore, both biotic and abiotic drivers may influence detrital nutrient content."

The study determined that leaves such as oak "immobilized" nitrogen. Generally thinking, it is thought that leaf litter acts as a "sink" for nutrients over time in aquatic ecosystems.

Oh, and one more thing about leaves and their resulting detritus in tropical streams: Ecologists strongly believe that microbial colonized detritus is a more palatable and nutritious food source for detritivores than uncolonized dead leaves. The microbial growth which occurs on the leaves and their resulting detritus increases the nutritional quality of leaf detritus, because the microbial biomass on the leaves is more digestible than the leaves themselves (because of lignin, etc.).

Okay, great. I've just talked about decomposing leaves and stuff for like the 11,000th time in "The Tint"; so...where does this leave us, in terms of how we want to run our aquariums?

Let's summarize:

1) Add a significant amount of leaf litter, twigs, and botanicals to your aquarium as part of the substrate.

2) Allow biofilms and fungal growths to proliferate.

3) Feed your fishes well. It's actually "feeding the aquarium!"

4) Don't go crazy siphoning out every bit of detritus.

Let's look at each of these points in a bit more detail.

First, make liberal use of leaf litter in your aquarium. I'd build up a layer anywhere from 1"-4" of leaves. Yeah, I know- that's a lot of leaves. Initially, you'll have a big old layer of leaves, recruiting biofilms and fungal growths on their surfaces. Ultimately, it will decompose, creating a sort of "mulch" on the bottom of your aquarium, rich in detritus, providing an excellent place for your fishes to forage among.

Allow a fair amount of indirect circulation over the top of your leaf litter bed. This will ensure oxygenation, and allow the organisms within the litter bed to receive an influx of water (and thus, the dissolved organics they utilize). Sure, some of the leaves might blow around from time to time- just like what happens in Nature. It's no big deal- really!

The idea of allowing biofilms and fungal growths to colonize your leaves and botanicals, and to proliferate upon them simply needs to be accepted as fundamental to botanical-style aquarium keeping. These organisms, which comprise the biome of our aquariums, are the most important "components" of the ecosystems which our aquariums are.

I'd be remiss if I didn't at least touch on the idea of feeding your aquarium. Think about it: When you feed your fishes, you are effectively feeding all of the other life forms which comprise this microbiome. You're "feeding the aquarium." When fishes consume and eliminate the food, they're releasing not only dissolved organic wastes, but fecal materials, which are likely not fully digested. The nutritional value of partially digested food cannot be understated. Many of the organisms which live within the botanical bed and the resulting detritus will assimilate them.

Now, we could go on and on about this topic; there is SO much to discuss. However, let's just agree that feeding our fishes is another critical activity which provides not only for our fishes' well-being, but for the other life forms which create the ecology of the aquarium.

And, let's be clear about another thing: Detritus, the nemesis of many aquarists- is NOT our enemy. We've talked about this for several years now, and I cannot stress it enough: To remove every bit of detritus in our tanks is to deprive someone, somewhere along the food chain in our tanks, their nutritional source. And when you do that, imbalances occur...You know, the kinds which cause "nuisance algae" and those "anomalous tank crashes."

The definition of this stuff, as accepted in the aquarium hobby, is kind of sketchy in this regard; not flattering at the very least:

"detritus is dead particulate organic matter. It typically includes the bodies or fragments of dead organisms, as well as fecal material. Detritus is typically colonized by communities of microorganisms which act to decompose or remineralize the material."

Shit, that's just bad branding.

The reality is that this not a "bad" thing. Detritus, like biofilms and fungi, is flat-out misunderstood in the hobby.

Could there be some "upside" to this stuff?

Of course there is.

I mean, even in the above the definition, there is the part about being "colonized by communities of microorganisms which act to decompose or remineralize..."

It's being processed. Utilized. What do these microorganisms do? They eat it...They render it inert. And in the process, they contribute to the biological diversity and arguably even the stability of the system. Some of them are utilized as food by other creatures. Important in a closed system, I should think.

This is really important. It's part of the biological operating system of our botanical-style aquariums. I cannot stress this enough.

Now, I realize that the idea of embracing this stuff- and allowing it to accumulate, or even be present in your system- goes against virtually everything we've been indoctrinated to believe in about aquarium husbandry. Pretty much every article you see on this stuff is about its "dangers", and how to get it out of your tank. I'll say it again- I think we've been looking at detritus the wrong way for a very long time in the aquarium hobby, perceiving it as an "enemy" to be feared, as opposed to the "biological catalyst" it really is!

In essence, it's organically rich particulate material that provides sustenance, and indeed, life to many organisms which, in turn, directly benefit our aquariums.

We've pushed this narrative many times here, and I still think we need to encourage hobbyists to embrace it more.

Yeah, detritus.

Okay, I'll admit that detritus, as we see it, may not be the most attractive thing to look at in our tanks. I'll give you that. It literally looks like a pile of shit! However, what we're talking about allowing to accumulate isn't just fish poop and uneaten food. It's broken-down materials- the end product of biological processing. And, yeah, a wide variety of organisms have become adapted to eat or utilize detritus.

There is, of course, a distinction.

One is the result of poor husbandry, and of course, is not something we'd want to accumulate in our aquariums. The other is a more nuanced definition.

As we talk about so much around here- just because something looks a certain way doesn't mean that it alwaysa bad thing, right?

What does it mean? Take into consideration why we add botanicals to our tanks in the first place. Now, you don't have to have huge piles of the stuff littering your sandy substrate. However, you could have some accumulating here and there among the botanicals and leaves, where it may not offend your aesthetic senses, and still contribute to the overall aquatic ecosystem you've created.

If you're one of those hobbyists who allows your leaves and other botanicals to break down completely into the tank, what really happens? Do you see a decline in water quality in a well-maintained system? A noticeable uptick in nitrate or other signs? Does anyone ever do water tests to confirm the "detritus is dangerous" theory, or do we simply rely on what "they" say in the books and hobby forums?

Is there ever a situation, a place, or a circumstance where leaving the detritus "in play" is actually a benefit, as opposed to a problem?

I think so. Like, almost always.

Yes, I know, we're talking about a closed ecosystem here, which doesn't have all of the millions of minute inputs and exports and nuances that Nature does, but structurally and functionally, we have some of them at the highest levels (ie; water going in and coming out, food sources being added, stuff being exported, etc.).

There is so much more to this stuff than to simply buy in unflinchingly to overly-generalized statements like, "detritus is bad."

The following statement may hurt a few sensitive people. Consider it some "tough love" today:

If you're not a complete incompetent at basic aquarium husbandry, you won't have any issues with detritus being present in your aquarium.

Just:

Don't overstock.

Don't overfeed.

Don't neglect regular water exchanges.

Don't fail to maintain your equipment.

Don't ignore what's happening in your tank.

This is truly not "rocket science." It's "Aquarium Keeping 101."

And it all comes full circle when we talk about "filtration" in our aquariums.

People often ask me, "What filter do you use use in a botanical-style aquarium?" My answer is usually that it just doesn't matter. You can use any type of filter. The reality is that, if allowed to evolve and grow unfettered, the aquarium itself- all of it- becomes the "filter."

You can embrace this philosophy regardless of the type of filter that you employ.

My sumps and integrated filter compartments in my A.I.O. tanks are essentially empty.

I may occasionally employ some activated carbon in small amounts, or throw some "Shade" sachets in there if I am feeling it- but that's it. The way I see it- these areas, in a botanical-style aquarium, simply provide more water volume, more gas exchange; a place for bacterial attachment (surface area), and perhaps an area for botanical debris to settle out. Maybe I'll remove them, if only to prevent them from slowing down the flow rate of my return pumps.

But that's it.

A lot of people are initially surprised by this. However, when you look at it in the broader context of botanical style aquariums as miniature ecosystems, it all really makes sense, doesn't it? The work of these microorganisms and other life forms takes place throughout the aquarium.

I admit, there was a time when I was really fanatical about making sure every single bit of detritus and fish poop and all that stuff was out of my tanks. About undetectable nitrate. I was especially like that in my earlier days of reef keeping, when it was thought that cleanliness was the shit!