- Continue Shopping

- Your Cart is Empty

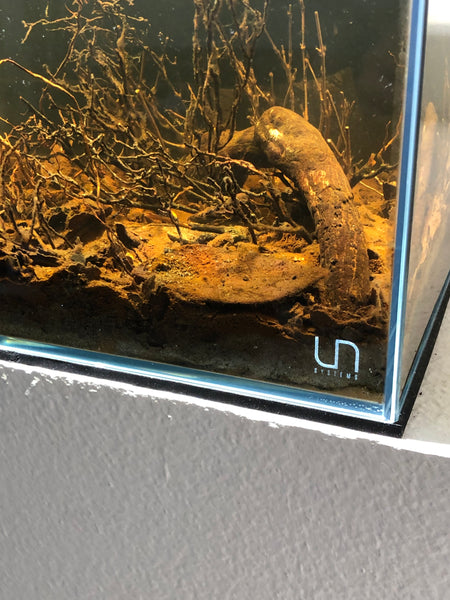

Behind the dynamics of the "Urban Igapo"

I've always been fascinated by environments which transform from dry, terrestrial ones to lush aquatic ones during the course of the year. I remember as a kid visiting a little depression in a field near my home , which, every spring, with the rains would turn into a little pond, complete with frogs, Fairy Shrimp, and other life forms. I used to love exploring it, and was utterly transfixed by the unique and dynamic seasonal transition.

The thrill and fascination of seeing that little depression in the ground, which I later learned was called a "vernal" or "temporal" pool by ecologists, never quite left me. As a fish geek, I knew that one day I'd be able to incorporate what I had seen into my fish keeping hobby...somehow.

About 5 years ago, I got a real "bug up my ass", as they say, about the flooded forests of South America. There is something alluring to me about the way these habitats transition between terrestrial and aquatic at certain times of the year. The migration of fishes and the emergence of aquatic life forms in a formerly terrestrial environment fascinates me- as does the tenacity of the terrestrial organisms which hang on during these periods of inundation.

So, I began playing with aquariums configured to replicate the function and form of these unique habitats. I spent a lot of time studying the components of the Igapo and Varzea environments- the soils, plants, fauna, etc., and learning the influences which lead to their creation and function.

Once I had a grasp of the way these dynamic ecologies work, the task of attempting to recreate them in the aquarium became more realistic and achievable. I realized that, although hobbyists have created what they call "Igapo" simulations in biotope contests for years, for example, it was always a representation of the "wet" season. Essentially a living "diorama" of sorts. Not really a true simulation of the seasonal dynamics which create these habitats.

They were cool, but something was somehow missing to me. With those representations, you throw in some leaves, twigs, and seed pods, maybe a few plants, and call your tank a "flooded forest." I mean, essentially a botanical-style aquairum, although the emphasis was on appearance, not function. That wasn't really that difficult to do, nor much of a advancement in the current state of the art of aquarium keeping. I could do that already. Rather, I wanted to recreate the process- all of it- or as much as possible- in my aquariums.

Thus, the idea of the "Urban Igapo"- a functional representation of a transitional aquatic habitat was born.

The concept behind the "Urban Igapo" is pretty straightforward:

The idea is to replicate to a certain extent, the seasonal inundation of the forests and grasslands of of Amazonia by starting the tank in a 'terrestrial phase", then slowly inundating it with water over a period of weeks or more; then, running the system in an "aquatic phase" for the duration of the 'wet season", then repeating the process again and again.

Because you can do this in the comfort of your own home, we called the concept the "Urban Igapo." About 2 years ago, we went more in depth with some of the procedures and techniques that you'd want to incorporate into your own executions of the idea.

As with so many things in the modern aquarium hobby, there is occasionally some confusion and even misunderstandings about why the hell we do this in the first place!

Well, that's a good question! I mean, the whole idea of this particular approach is to replicate as faithfully as possible the seasonal wet/dry cycles which occur in these habitats. It starts with a dry or terrestrial environment, managed as such for an extended period of time, which is gradually flooded to simulate inundation which occurs when the rainy season commences and swollen rivers and streams overflow into the forest or grassland.

Sure, you can replicate the "wet season" only- absolutely. I've seen tons of tanks created by hobbyists to do this. However, if you want to replicate the seasonal cycle- the real magic of this approach- you'll find as I did that it's more fun to do the "dry season!"

Think of it in the context of what the aquatic environment is- a forest floor or grassland which has been flooded. If you develop the "hardscape" (gulp) for your tank with that it mind, it starts making more sense. What do you find on a forest floor or grassland habitat? Soil, leaf litter, twigs, seed pods, branches, grasses, and plants.

Just add water, right?

Well, sort of.

Now, recently, one of my friends who was presenting his experiences with this approach was just getting pounded on a forum by some, well- let's nicely call them "skeptics"- you know, the typical internet-brave "armchair expert" types- about why you'd do this and how it can't lead to a stable aquarium and how it's "not a blackwater aquarium" (okay, it wasn't presented as such, but it could be...) and that it's just a "dry start" (Well, sort of, but you have to understand the concept behind it, dude), and that you don't need to do it this way and...well- that kind of stuff.

I mean, the full compliment of negative, ignorant, questions by people clearly frightened about someone trying to do something a little differently. In a typical display of online-warrior hypocrisy, one particularly nasty hack did not even bother to research the idea or think about what it was really trying to do before laying into my friend.

Apparently, for these people, there was a lot to unpack.

I mean, first of all, the idea was not intended to be a "dry start" planted tank. It just wasn't. I mean, it starts out "dry", but that's where the similarity ends. This ignorant comment is a classic example of the way some hobbyists make assumptions based on a superficial understanding of something.

We aren't trying to grow aquatic plants here. It's about creating a habitat of terrestrial plants snd grasses, allowing them to establish, snd then inundating the display. Most of the terrestrial grasses will simply not survive extended periods of time submerged. Now, you COULD add adaptable aquatic plants- there are no "rules"- but the intention was to replicate a seasonal dynamic.

The other point, which is utterly lost on some people, is that establishing a "transitional" environment in an aquarium takes time and patience. One dummy literally called the process "complete nonsense" and a "waste of time." This is exactly the kind of self-righteous, ignorant hobbyist who will never get it. In fact, I'm surprised guys like that actually have any success at anything in the hobby.

Such a dismissive and judgmental attitude.

The wet season in The Amazon runs from November to June. And it rains almost every day. And what's really interesting is that the surrounding Amazon rain forest is estimated by some scientists to create as much as 50% of its own precipitation! Think about THAT for a minute. It does this via the humidity present in the forest itself, from the water vapor present on plant leaves- which contributes to the formation of rain clouds.

Yeah, trees in the Amazon release enough moisture through photosynthesis to create low-level clouds and literally generate rain, according to a recent study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (U.S.)!

That's crazy.

But it makes a lot of sense, right?

Yet another reason why we need to protect these precious habitats. You cut down a tree in the Amazon- you're literally reducing the amount of rain that can be produced.

It's that simple.

That's really important. It's more than just a cool "cocktail party sound bite."

So what happens to the (aquatic) environment in which our fishes live in when it rains? What does the rain actually do?

Well, for one thing, rain performs the dual function of diluting organics, while transporting more nutrient and materials across the ecosystem. What happens in many of the regions of Amazonia, for example- is the evolution of our most compelling environmental niches. The water levels in the rivers rise significantly. often several meters, and the once dry forest floor fills with water from the torrential rain and overflowing rivers and streams.

The Igapos are formed.

Flooded forest floors.

The formerly terrestrial environment is now transformed into an earthy, twisted, incredibly rich aquatic habitat, which fishes have evolved over eons to live in and utilize for food, protection, and spawning areas.

All of the botanical material-shrubs, grasses, fallen leaves, branches, seed pods, and such, is suddenly submerged; often, currents re-distribute the leaves and seed pods and branches into little pockets and "stands", affecting the (now underwater) "topography" of the landscape.

Leaves begin to accumulate.

Soils dissolve their chemical constituents- tannins, and humic acids- into the water, enriching it. Fungi and micororganisms begin to feed on and break down the materials. Biofilms form, crustaceans multiply rapidly. Fishes are able to find new food sources; new hiding places..new areas to spawn.

Life flourishes.

So, yeah, the rains have a huge impact on tropical aquatic ecosystems. And it's important to think of the relationship between the terrestrial habitat and the aquatic one when visualizing the possibilities of replicating nature in your aquarium in this context.

It's an intimate, interrelated, "codependent" sort of arrangement!

To replicate this process is really not difficult. The challenging part is to separate what we are trying to do here from our preconceptions about how an aquarium should work. To understand that the resulting aquatic display won't initially look or function like anything that we're already familiar with.

While it superficially resembles the "dry start" method that many aquatic plant enthusiasts play with, it's important to remember that our goal isn't to start plants for a traditional aquarium. It's to establish terrestrial growth and to facilitate a microbiome of organisms which help create this habitat. It's to replicate, on some levels, the year-round dynamic of the Amazonian forests. We favor terrestrial plants- and grasses-grown from seed, to start the "cycle."

So, those of you who are ready to downplay the significance of experimenting with this stuff because "people have done 'dry start' planted tanks for years", take comfort in the fact that I recognize that, and acknowledge that we're taking a slightly different approach here, okay?

You'll need to create a technical means or set of procedures to gradually flood your "rainforest floor" in your tank, which could be accomplished manually, by simply pouring water into the vivarium over a series of days; or automatically, with solenoids controlling valves from a reservoir beneath the setup, or perhaps employing the "rain heads" that frog and herp people use in their systems. This is all very achievable, even for hobbyists like me with limited "DIY" skills.

You just have to innovate, and be willing to do a little busy work. You can keep it incredibly simple, and just utilize a small tank.

You must be patient.

And of course, there are questions. Here are some of the major/common ones we receive about this concept:

Does the grass and plants that you've grown in the "dry season" survive the inundation?

A great question. Some do, some don't. (How's that for concise info!). I've played with grasses which are immersion tolerant, such as Paspalum. This stuff will "hang around" for a while while submerged for about a month and a half to two months, in my experience, before ultimately succumbing. Sometimes it comes back when the "dry season" returns. However, when it doesn't survive, it decomposes in the now aquatic substrate, and adds to the biological diversity by cultivating fungi and bacteria.

You can use many plants which are riparian in nature or capable of growing emmersed, such as my fave, Acorus, as well as all sorts of plants, even aquatics, like Hydrocotyle, Cryptocoryne, and others. These can, of course, survive the transition between aquatic and "terrestrial" environments.

How long does the "dry season" have to last?

Well, if you want to mimic one of these habitats in the most realistic manner possible, follow the exact wet and dry seasons as you'd encounter in the locale you're inspired by. Alternatively, I'd at least go 2 months "dry" to encourage a nice growth of grasses and plants prior to inundation.

And of course, you cans do this over and over again! If you're trying to keep fishes like annual killifishes, the "dry season" could be used on the incubation period of their eggs.

When you flood the tank, doesn't it make a cloudy mess? Does the water quality decline rapidly?

Sure, when you add water to what is essentially a terrestrial "planter box", you're going to get cloudiness, from the sediments and other materials present in the substrate. You will have clumps of grasses or other botanical materials likely floating around for a while.

Surprisingly, in my experience, the water quality stays remarkably good for aquatic life. Now, I'm not saying that it's all pristine and crystal clear; however, if you let things settle out a bit before adding fishes, the water clears up and a surprising amount of life (various microorganisms like Paramecium, bacteria, etc.) emerges.

Curiously, I personally have NOT recorded ammonia or nitrite spikes following the inundation. That being said, you can and should test your water before adding fishes. You can also dose bacterial inoculants, like our own "Culture" or others, into the water to help. The Purple Non-Sulphur bacteria in "Culture" are extremophiles, particularly well adapted to the dynamics of the wet/dry environment.

Should I use a filter in the "wet season?"

You certainly can. I've gone both ways, using a small internal filter or sponge filter in some instances. I've also played with simply using an air stone. Most of the time, I don't use any filtration. I just conduct partial water exchanges like I would with any other tank- although I take care not to disturb the substrate too much if I can. When I scaled up my "Urban Igapo" experiments to larger tanks (greater than 10 gallons), Il incorporated a filters with no issues.

A lot of what we do is simply letting Nature "take Her course."

Ceding a lot of the control to Nature is hard for some to quantify as a "technique" or "method", so I get it. At various phases in the process, our "best practice" might be to simply observe...

And with plant growth slowing down, or even going completely dormant while submerged, the utilization of nutrients via their growth diminishes, and aquatic life forms (biofilms, algae, aquatic plants, and various bacteria, microorganisms, and microcrustaceans) take over. There is obviously an initial "lag time" when this transitional phase occurs- a time when there is the greatest opportunity for one life form or another (algae, bacterial biofilms, etc.) to become the dominant "player" in the microcosm.

It's exactly what happens in Nature during this period, right?

And there are parallels in the management of aquariums.

In our aquarium practice, it's the time when you think about the impact of technique-such as water exchanges, addition of aquatic plants, adding fishes, reducing light intensity and photoperiod, etc. and (again) observation to keep things in balance- at least as much as possible. You'll question yourself...and wonder if you should intervene- and how..

It's about a number of measured moves, any of which could have significant impact- even "take over" the system- if allowed to do so. This is part of the reason why we don't currently recommend playing with the Urban Igapo idea on a large-tank scale just yet. (that, and the fact that we're not going to be geared up to produce thousands of pounds of the various substrates just yet! 😆)

Until you make those mental shifts to accept all of this stuff in one of these small tanks, the idea of replicating this in 40-50, or 100 gallons is something that you may want to hold off on for just a bit.

Or not.

I mean, if you understand and accept the processes, functions, and aesthetics of this stuff, maybe you wouldwant to "go big" on your first attempt. However, I think you need to try it on a "nano scale" first, to really "acclimate" to the idea.

The idea of accepting Nature as it is makes you extremely humble, because there is a realization at some point that you're more of an "interested observer" than an "active participant." It's a dance. One which we may only have so much control- or even understanding of! That's part of the charm, IMHO.

These habitats are a remarkable "mix" of terrestrial and aquatic elements, processes, and cycles. There is a lot going on. It's not just, "Okay, the water is here- now it's a stream!"

Nope. There is a lot of stuff to consider.

In fact, one of the arguments one could make about these "Urban Igapo" systems is that you may not want to aggressively intervene during the transition, because there is so much going on! Rather, you may simply want toobserve and study the processes and results which occur during this phase. Personally, I've noticed that the "wet season" changes in my UI tanks generally happen slowly, but you will definitely notice them as they occur.

After you've run through two or three complete "seasonal transition cycles" in your "Urban Igapo", you'll either hate the shit out of the idea- or you'll fall completely in love with it, and want to do more and more work in this alluring little sub-sector of the botanical-style aquarium world.

The opportunity to learn more about the unique nuances which occur during the transition from a terrestrial to an aquatic habitat is irresistible to me. Of course, I'm willing to accept all of the stuff with a very open mind. Typically, it results in a fascinating, utterly beautiful, and surprisingly realistic representation of what happens in Nature.

It's also entirely possible to have your "Urban Igapo" turn into an "Urban Algae Farm" if things get out of balance. Yet, it can "recover" from this. Again, even the fact that a system is "out of balance" doesn't mean that it's a failure. After all, the algae is thriving, right? That's a success. Life forms have adapted. A cause to celebrate.

It happens in Nature, too!

So, that's a brief rundown on the dynamics and challenges of the "Urban Igapo" concept. It will be exciting to see how each of us evolves the idea further!

Stay creative. Stay thoughtful. Stay bold. Stay curious...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Movement...

One of the things that drives most hobbyists crazy is when "stuff" gets blown around, covered or moved about in the aquarium. It can be because of strong current, the activity of fishes, or simply overgrown by plants. I understand the annoyance that many hobbyists feel; I recall this same aggravating feeling in many reef tanks where I had high flow and sand on the bottom- almost always a combination for annoyance!

I mean, I get it. We have what feel is a carefully thought-out aquascape, looking exactly how we expected it would after setup. Yet, despite our ideas and thoughts, stuff moves around in the aquarium. It's something we can either accept, or modify in our aquariums, depending upon our preferences.

Yet, movement and "covering" of various materials by sediments, biofilms, etc., which accumulate on the substrate in natural habitats are everyday occurrences, and they help forge a very dynamic ecosystem. And they are constantly creating new opportunities for the fishes which reside in them to exploit.

When you think about how materials "get around" in the wild aquatic habitats, there are a few factors which influence both the accumulation and distribution of them. In many topical streams, the water depth and intensity of the flow changes during periods of rain and runoff, creating significant re-distribution of the materials which accumulate on the bottom, such as leaves, branches, seed pods, and the like.

Larger, more "hefty" materials, such as branches, submerged logs, etc., will tend to move less frequently, and in many instances, they'll remain stationary, providing a physical diversion for water as substrate materials accumulate around them.

A "dam", of sorts, if you will.

And this creates known structures within streams in areas like Amazonia, which are known to have existed for many years. Semi-permanent aquatic features within the streams, which influence not only the physical and chemical environment, but the very habits and abundance of the fishes which reside there.

Most of the small stuff, like leaves, tend to move around quite a bit... One might say that the "material changes" created by this movement of materials can have significant implications for fishes. As we've talked about before, they follow the food, often existing in, and subsisting off of what they can find in these areas.

New accumulations of leaves, detritus, and other materials benefit the entire ecosystem.

In the case of our aquariums, this "redistribution" of material can create interesting opportunities to not only switch up the aesthetics of our tanks, but to provide new and unique little physical areas for many of the fishes we keep.

And yeah, the creation of new feeding opportunities for life forms at all levels is a positive which simply cannot be overstated! As hobbyists, we tend to lament changes to the aquascape of our tanks caused by things outside of our control, and consider them to be a huge inconvenience, when in reality, they're not only facsimile of very natural dynamic processes-they are fundamental to their evolution.

The benthic microfauna which our fishes tend to feed on also are affected by this phenomenon, and as mentioned above, the fishes tend to "follow the food", making this a case of the fishes adapting to a changing environment. And perhaps...maybe...the idea of fishes sort of having to constantly adjust to a changing physical environment could be some sort of "trigger", hidden deep in their genetic code, that perhaps stimulates overall health, immunity or spawning?

Something in their "programing" that says, "You're at home..." Perhaps something which triggers specific adaptive behaviors?

I find this possibility fascinating, because we can learn more about our fishes' behaviors, and create really interesting habitats for them simply by adding botanicals to our aquariums and allowing them to "do their own thing"- to break apart as they decompose, move about as we change water or conduct maintenance activities, or add new pieces from time to time.

Again, just like Nature.

We just need to "get over ourselves" on this aesthetic thing!

Another mental shift? Yeah, it is. An easy one, but one that we need make, really.

Like any environment, botanical/ leaf litter beds have their own "rhythm", fostering substantial communities of fishes. The dynamic behind this biotope can best be summarized in this interesting excerpt from an academic paper on blackwater leaf-litter communities by biologist Peter Alan Henderson, that is useful for those of us attempting to replicate these communities in our aquaria:

"..life within the litter is not a crowded, chaotic scramble for space and food. Each species occupies a sub-region defined by physical variables such as flow and oxygen content, water depth, litter depth and particle size…

...this subtle subdivision of space is the key to understanding the maintenance of diversity. While subdivision of time is also evident with, for example, gymnotids hunting by night and cichlids hunting by day, this is only possible when each species has its space within which to hide.”

In other words, different species inhabit different sections of the leaf litter beds. As aquarists, we should consider this when creating and stocking our botanical-style aquariums.

It just makes sense, right?

So, when you're attempting to replicate such an environment, consider how the fishes would utilize each of the materials you're working with. For example, leaf litter areas would be an idea shelter for many juvenile fishes, catfishes, and even young cichlids to shelter among.

Submerged branches, larger seed pods and other botanicals provide territory and areas where fishes can forage for macrophytes (algal growths which occur on the surfaces of these materials). Fish selection can be influenced as much by the materials you're using to 'scape the tank as anything else, when you think about it!

And it's not just fishes, of course. It's a multitude of life forms.

There are numerous life forms which are found on ad among these materials as well, such as fungal growths, bacterial biofilms, etc. which we likely never really consider, yet are found in abundance in nature and in the aquarium, and perform vital roles in the function of the aquatic habitat.

Perhaps most fascinating and rarely discussed in the hobby, are the unique freshwater sponges, from the genus Spongilla. Yes, you heard. Freshwater sponges! These interesting life forms attach themselves to rocks and logs and filter the water for various small aquatic organisms, like bacteria, protozoa, and other minute aquatic life forms. Some are truly incredible looking organisms!

(Spongilla lacustris Image by Kirt Onthank. Used under CC-BY SA 3.0)

Unlike the better-known marine sponges, freshwater sponges are subjected to the more variable environment of rivers and streams, and have adapted a strategy of survival. When conditions deteriorate, the organisms create "buds", known as "gemmules", which are an asexually reproduced mass of cells capable of developing into a new sponge! The Gemmules remain dormant until environmental conditions permit them to develop once again!

Oh, cool!

To my knowledge, these organisms have never been intentionally collected for aquariums, and I suspect they are a little tricky to transport (despite their adaptability), just ike their marine cousins are. One species, Metania reticulata, is extremely common in the Brazilian Amazon. They are found on rocks, submerged branches, and even tree trunks when these areas are submerged, and remain in a dormant phase in the aforementioned gemmules during periods of desiccation!

Now, I'm not suggesting that we go and collect freshwater sponges for aquarium use, but I am curious if they occur as "hitchhikers" on driftwood, rocks or other materials which end up in our aquariums. When you think about how important sponges are as natural "filters", one can only wonder how they might perform this beneficial role in the aquarium as well!

We've encountered them in reef tanks for many years...I wonder if they could ultimately find their way into our botanical-style aquariums as well? Perhaps they already have. Have any of you encountered one before in your tanks?

The big takeaway from all of this: A botanical bed in our aquariums and in Nature is a physical structure, ephemeral though it may be- which functions just like an aggregation of branches, or a reef, rock piles, or other features would in the wild benthic environment, although perhaps even "looser" and more dynamic.

Stuff gets redistributed, covered, and often breaks down over time. Exactly like what happens in Nature.

Think about the possibilities which are out there, under every leaf. Every sunken branch. Every root. Every rock.

It's all brought about by the dynamic process of movement.

Perhaps instead of looking at the movement of stuff in our tanks as an annoyance, we might enjoy it a lot more if we look at it as an opportunity! An opportunity to learn more about the behaviors and life styles of our fishes and their ever-changing environment.

Stay observant. Stay creative. Stay excited. Stay open-minded...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

The slow(er) road to success with fish stocking...

One of the questions which we are asked less and less these days is, 'What kinds of fishes are suitable for a botanical-style aquarium?" I think that after 6 years of pounding all of these ideas into your heads about all of the strange nuances of botanical-style aquariums, it's almost universally understood that pretty much any fishes can live in them.

On the other hand, when it comes to how we stock our tanks, nothing has really changed...however, it could. And it should, IMHO.

We spend a pretty good amount of time studying, scheming, and pondering how to create a compatible, interesting, and attractive community of fishes within our aquariums.

It's probably among the most enjoyable things that we do in the hobby, right?

As a somewhat eccentric philosopher of all things fish, one of my favorite things to ponder is stuff that we do while creating our aquariums which is- intentionally or otherwise- analogous to the factors in Nature that result in the environments and fish populations that we find so compelling.

If you're like me, you likely spend a little too much time pondering all sorts of arcane aspects of the hobby...Okay, so maybe you're NOT like me, but you probably have a rather keen interest in the way Nature operates in the wild aquatic systems of the world, and stock your aquariums accordingly.

As one who studies a lot of details about some of the habitats from which our fishes come, I can't help but occasionally wonder exactly what it is that brings fishes to a given location or niche within a environment?

Now, the first answer we're likely to proffer is the most apparent...right? I mean, they follow the food!

Fishes tend to move into new areas in search suitable food sources as part of their life cycle. And food sources often become available in habitats such as flooded forest areas after the rains come, when decomposing leaves and botanical materials begin to create (or re-activate, as the case may be) "food webs", attracting ever more complex life forms into the area.

When we create our aquariums, we take into consideration a lot of factors, ranging from the temperament and size of our fish selections, to their appearance, right? These are all important factors. However, have you ever considered what the factors are in nature which affect the composition of a fish community in a given habitat?

Like, why "x" fish is living in a particular habitat?

What adaptations has the fish made that make it uniquely suitable for this environmental niche? Further, have you thought about how we as hobbyists replicate, to some extent, the actual selection processes which occur in Nature in our quest to create the perfect community aquarium?

Now, if you're an African Cichlid lover or reef hobbyist, I'm sure you have!

Social hierarchies, spatial orientations, and allopathic processes are vital to success in those types of aquariums; you typically can't get away with just throwing in a random fish or coral and hoping it will just mix perfectly.

However, for many hobbyists who aim to construct simple "community tanks", it isn't that vital to fill specific niches and such...we probably move other factors to the forefront when thinking about possible additions to our community of fishes: Like, how cool the fish looks, how large it grows, if it has a peaceful temperament, etc. More basic stuff.

However, in the end, we almost always make selections based upon factors which we deem important...again, a sort of near-mimicry of natural processes- and how the fishes work in the habitat we've created for them.

"Unnatural selection?" Or...Is it essentially what nature's does for eons?

Oh, and what exactly is an "aquatic habitat", by the way? In short, you could say that an aquatic habitat is the physical, chemical, and biological characteristics which determine the suitability for habitation and reproduction of fishes.

Of course, these characteristics can determine which fishes are found in a given area in the wild- pretty much without exception. It's been happening for eons.

Approaching the stocking of an aquarium by determining which fishes would be appropriate for the physical characteristics of the tank is not exactly groundbreaking stuff.

However, when we evaluate this in the context of "theme", and what fish would be found within, say, an Amazonian Igarape stream or a Southeast Asian peat swamp, the idea of adding fishes to "exploit" the features of the habitat we've created is remarkably similar to the processes which occur in Nature that determine what fish are found there, and it's the ultimate expression of good tank planning, IMHO.

It's just kind of interesting to think about in that context, right?

Competition is another one of the important factors in determining how fish populations in the wild. Specifically, competition for space, resources (e.g.; food) and mates are prevalent. In our aquariums, we do see this to some extent, right? The "alpha male" cichlid, the Pleco that gets the best cave, and the Tetra which dominates his shoal.

How we create the physical space for our fishes can have significant impact on this behavior. When good hiding spaces are at a premium, as are available spawning partners, their will be some form of social hierarchy, right?

Other environmental factors, such as water movement, dissolved oxygen, etc. are perhaps less impactful on our community once the tank is established. However, these factors figure prominently in our decisions about the composition of, or numbers or fishes in the community, don't they?

For example, you're unlikely to keep Hillstream loaches in a near stagnant, blackwater swamp biotope aquarium, just like you'd be unlikely to keep Altum Angelfish in a fast-moving stream biotope representation. And fishes which shoal or school will, obviously, best be kept in numbers.

"Aquarium Keeping 101", again.

One factor that we typically don't have in our aquaria is predation. I know very few aquarists who would be sadistic enough to even contemplate trying to keep predators and prey in the same tank, to let them "have at it" and see what happens, and who comes out on top!

I mean, there is a lot to this stuff, isn't there?

Again, the idea of creating a tank to serve the needs of certain fishes isn't earth-shattering. Yet, the idea of stocking the tank based on the available niches and physical characteristics is kind of a cool, educational, and ultimately very gratifying process. I just think it's truly amazing that we're able to actually do this these days.

And the sequence that you stock your tank in is extremely pertinent.

I think that you could literally create a sort of "sequence" to stocking various types of fishes based on the stage of "evolution" that your aquarium is in, although the sequence might be a bit different than Nature in some cases. For example, in a more-or-less brand new aquarium, analogous in this case to a newly-inundated forest floor, their might be a lot less in the way of lower life forms, such as fungi and bacteria, until the materials begin breaking down. You'd simply have an aggregation of fresh leaves, twigs, seed pods, soils, etc. in the habitat.

So, if anything, you're likely to see fishes which are much more dependent upon allochthonous input...food from the terrestrial environment. This is a compelling way to stock an aquarium, I think. Especially aquarium systems like ours which make use of these materials en masse.

Right from the start (after cycling, of course!), it would not be unrealistic to add fishes which feed on terrestrial fruits and botanical materials, such as Colossoma, Arowanna, Metynis, etc. Fishes which, for most aquarists of course, are utterly impractical to keep because of their large adult size and/or need for physical space!

(Pacu! Image by Rufus46, used under CC BY-SA 3.0)

Now, a lot of smaller, more "aquarium suited" fishes will also pick at these fruits and seeds, so you're not totally stuck with the big brutes if you want to go this route! Interestingly, the consumption and elimination of fruits by fishes is thought to be a major factor in the distribution of many plants in the region.

Do a little research here and you might be quite surprised about who consumes what in these habitats!

More realistically for most aquarists, I'd think that you could easily stock first with fishes like surface-dwelling (or near surface-dwelling) species, like hatchetfishes and some Pencilfishes, which are largely dependent upon terrestrial insects such as flies and ants, in Nature. In other words, they tend to "forage" or "graze" little, and are more opportunistic, taking advantage of careless insects which end up in the water of these newly-inundated environs.

I've read studies where almost 100 species were documented which feed near-exclusively on insects and arthropods from terrestrial sources in these habitats! As I mention often, if you dive a bit deeper than the typical hobbyist writings, and venture into scholarly materials and species descriptions, you'll be fascinated to read about the gut-content analysis of fishes, because they give you a tremendous insight about what to feed in the aquarium!

Continuing on, it's easy to see that, as the environments evolve, so does the fish population. And the possibilities for simulating this in the aquarium are many and are quite interesting!

Later, as materials start to decompose and are acted on by fungi and bacteria, you could conceivably add more of the "grazing" type fishes, such as Plecos, small Corydoras, Headstanders, etc.

As the tank ages and breaks in more, this would be analogous to the period of time when micro-crustaceans and aquatic insects are present in greater numbers, and you'd be inclined to see more of the "micropredators" like characins, and ultimately, small cichlids.

Interestingly, scientists have postulated that evolution favored small fishes like characins in these environments, because they are more efficient at capturing small terrestrial insects and spiders in these flooded forests than the larger fishes are!

And it makes a lot of sense, if you look at it strictly from a "density/variety" standpoint- lots of characins call these habitats home!

Then there are detritivores.

The detrivorus fishes remove large quantities of this material from submerged trees, branches, etc. Now, you might be surprised to learn that, in the wild, the gut-content analysis of almost every fish indicates that they consume organic detritus to some extent! And it makes sense...They work with the food sources that are available to them!

At different times of the year, different food sources are easier to obtain.

And, of course, all of the fishes which live in these habitats contribute to the surrounding forests by "recycling" nutrients locked up in the detritus. This is thought by ecologists to be especially important in blackwater inundated forests and meadows in areas like The Pantanal, because of the long periods of inundation and the nutrient-poor soils as a result of the slow decomposition rates.

All of this is actually very easy to replicate, to a certain extent, when stocking our aquaria. Why would you stock in this sort of sequence, when you're likely not relying on decomposing botanicals and leaves and the fungal and microbial life associated with them as your primary food source?

Well, you likely wouldn't be...However, what about the way that the fishes, when introduced at the appropriate "phase" in the tank's life cycle- adapt to the tank? Wouldn't the fishes take advantage of these materials as a supplement to the prepared foods that you're feeding them? Doesn't this impact the fishes' genetic "programming" in some fashion? Can it activate some health benefits, behaviors, etc?

I believe that it can. And I believe that this type of more natural feeding ca profoundly and positively impact our fishes' health.

I’m no genius, trust me. I don’t have half the skills many of you do but I have succeeded with many delicate “hard-to-feed” fishes over my hobby “career.”

Why?

Because I'm really patient.

Success with this approach is simply a result of deploying "radical patience." The practice of just moving really slowly and carefully when adding fishes to new tanks.

It's a really simple concept.

The hard part is waiting longer to add fishes.

Wait a minimum of three weeks—and even up to a month or two if you can stand it, and you will have a surprisingly large population of micro and macro fauna upon which your fishes can forage between feedings.

Having a “pre-stocked” system helps reduce a considerable amount of stress for new inhabitants, particularly for wild fishes, or fishes that have reputations as “delicate” feeders.

And think about it. This is really a natural analog of sorts. Fishes that live in inundated forest floors (yeah, the igapo again!) return to these areas to "follow the food" once they flood.

It just takes a few weeks, really. You’ll see fungal growth. You'll see some breakdown of the botanicals brought on by bacterial action or the feeding habits of small crustaceans and fungi. If you "pre-stock", you might even see the emergence of a significant population of copepods, amphipods, and other creatures crawling about, free from fishy predators, foraging on algae and detritus, and happily reproducing in your tank.

We kind of know this already, though- right?

This is really analogous to the tried-and-true practice of cultivating some turf algae on rocks either in or from outside your tank before adding herbivorous, grazing fishes, to give them some "grazing material."

Radical patience yields impressive results.

It’s not always easy to try something a little out of the ordinary, or a bit against the grain of popular practice, but I commend you for even thinking about the idea. At the very least, it may give you pause to how you stock your tank in the future, like "Herbivores first, micro predators last", or whatever thought you subscribe to.

Allow your system to mature and develop at least some populations of fauna for these fishes to supplement their diets with. You’ll develop a whole new appreciation for how an aquarium evolves when you take this long, but very cool road.

Stay patient. Stay observant. Stay creative. Stay studious. Stay resourceful...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Botanical materials in the wild...and in the aquarium: Influences and Impacts.

As you know, we've spent the better part of the past 6 years talking about every aspect of the botanical-style aquarium that we can think of. We've talked about techniques, approaches, ideas, etc. And we've spent a lot of time sharing information about wild aquatic habitats that we might be interested in replicating in both form and function.

However, I think we haven't spent as much time as we should talking about how botanicals "behave" in wild aquatic habitats. Much of this stuff has implications for those of us who are interested in replicating these habitats in our aquariums. So, let's dive in a bit more on this topic today!

Among the trees of the flooded forests, after the fruits mature (which occurs at high water levels), seeds will fall into the water and may float on the surface or be submerged for a number of weeks. Ecologists believe that the seed production of the trees coincides with the flood pulses, which facilitates their dispersal by water movement, and by the actions of fish.

Interestingly, scientists postulate that these floating or sinking seeds, which germinate and establish seedlings after the flood waters recede, do very well, sprouting and establishing themselves quickly, and are not severely affected by waterlogging in most species.

So, within their cycle of life, the trees take advantage of the water as part of their ecological adaptation. Trees in these areas have developed specialized morphologies, such as advantageous roots, butress systems and stilt roots.

In a lot of wild aquatic habitats where leaf litter and other allochthonous materials accumulate, there are a number of factors which control the density, size, and type of materials which are deposited in streams and such. The flow rate of the water within these habitats determines a lot of things, such as the size of the leaves and other botanical materials and where in the stream they are deposited.

I often wonder how much the fallen leaves and seed pods impact the water chemistry in a given stream, pond, or section of an Amazonian flooded forest. I know that studies have been done in which ecologists have measured dissolved oxygen and conductivity, as well as pH. However, those readings only give us so much information.

We hear a lot of discussion about blackwater habitats among hobbyists, and the implications for our aquariums. And part of the game here is understanding what it is that makes this a blackwater river system to begin with. We often hear that blackwater is "low in nutrients."

What exactly does this mean?

One study concluded that the Rio Negro is a blackwater river in large part because the very low nutrient concentrations of the soils that drain into it have arisen as a result of "several cycles of weathering, erosion, and sedimentation." In other words, there's not a whole lot of minerals and nutrients left in the soils to dissolve into the water to any meaningful extent!

Black-waters, drain from older rocks in areas like the Negro river, result from dissolved fulvic and humic substances, present small amounts of suspended sediment, lower pH (4.0 to 6.0) and dissolved elements. Yes, highly leached tropical environments where most of the soluble elements are quickly removed by heavy rainfall.

Perhaps...another reason (besides the previously cited limitation of light penetration) why aquatic plants are rather scare in these waters? It would appear that the bulk of the nutrients found in these blackwaters are likely dissolved into the aquatic environment by decomposing botanical materials, such as leaves, branches, etc.

Why does that sound familiar?

Besides the color, of course, the defining characteristics of blackwater rivers are pH values in the range of 4-5, low electrical conductivity, and minimal mineral content. Dissolved minerals, such as Ca, Mg, K, and Na are negligible. And with these low amounts of dissolved minerals come unique challenges for the animals who reside in these systems.

How do fishes survive and thrive in these rather extreme habitats?

It's long been known that fishes are well adapted to their natural habitats, particularly the more extreme ones. And this was borne out in a recent study of the Cardinal Tetra. Lab results suggest that humic substances protect cardinal tetras in the soft, acidic water in which they resides by preventing excessive sodium loss and stimulating calcium uptake to ensure proper homeostasis.

This is pretty extraordinary, as the humic substances found in the water actually enable the fishes to survive in this highly acidic water which is devoid of much mineral content typically needed for fishes to survive!

And of course, botanicals, leaves, and wood typically have an abundance of these humic substances, right? They are useful for more than just an interesting and unique aesthetic effect! There is a lot of room for research about influencing the overall environment in our aquariums here! I think we've barely scratched the surface of the potential for utilizing botanicals in our aquariums.

This is another one of those foundational aspects of the natural style of aquarium that we espouse. The understanding that processes like decomposition and physical transformation of the materials that we utilize our tanks are normal, expected, and beautiful things requires us to make mental shifts.

Botanical materials don't have nearly as much impact on the water parameters (other than say, conductivity and dissolved oxygen) as the soils do. These waters have high concentrations of humic and fulvic acids derived from sandy "hydromorphic podsols" prevalent in the region. However, these allochthonous materials have huge impact on the ecology of these systems!

Leaf litter, as one might suspect, is of huge importance in these ecosystems. Especially in smaller tributaries. In one study which I came across, it was concluded that, "The smaller the stream, the more dependent the biota is on leaf litter habitats and allocthonous energy derived directly or indirectly from the forest." (Kemenes and Forsberg)

From the same study, it was concluded that the substrate of the aquatic habitat had significant influence on the feeding habits of the fishes which resided in them:

"The biomass of allocthonous insectivore increased in channels with a higher percentage of sandy bottom substrate. Detritivorous insectivore biomass, in contrast, increased significantly in channels with a higher percentage of leaf substrate. General insectivores tended to increase in streams with higher proportions of leafy substrate, too.

Whats the implication for us as hobbyists? Well, for one thing, we can set up the benthic environment in our tanks to represent the appropriate environment for the fishes which we want to keep in them. Simple as that!

t's as much about function as anything else. And, about pushing into some new directions. The unorthodox aesthetics of these unusual aquariums we play with just happen to be an interesting "by-product" of theirfunction.

I personally think that almost every botanical-style aquarium can benefit from the presence of leaves. As we've discussed numerous times, leaves are the "operating system" of many natural habitats (ecology-wise), and perform a similar role in the aquarium.

The presence of botanical materials such as leaves in these aquatic habitats is fundamental. Leaves and other botanicals are extremely pervasive in almost every type of aquatic habitat.

In the tropical species of trees, the leaf drop is important to the surrounding environment. The nutrients are typically bound up in the leaves, so a regular release of leaves by the trees helps replenish the minerals and nutrients which are typically depleted from eons of leaching into the surrounding forests.

Now, interestingly enough, most tropical forest trees are classified as "evergreens", and don't have a specific seasonal leaf drop like the "deciduous" trees than many of us are more familiar with do...Rather, they replace their leaves gradually throughout the year as the leaves age and subsequently fall off the trees.

The implication here?

There is a more-or-less continuous "supply" of leaves falling off into the jungles and waterways in these habitats, which is why you'll see leaves at varying stages of decomposition in tropical streams. It's also why leaf litter banks may be almost "permanent" structures within some of these bodies of water!

Our botanical-style aquariums are not "set-and-forget" systems, and require basic maintenance (water exchanges, regular water testing, filter media replacement/cleaning), like any other aquarium. They do have one unique "requirement" as part of their ongoing maintenance which other types of aquariums seem to nothave: The "topping off" of botanicals as they break down.

The "topping off" of botanicals in your tank accomplishes a number of things: first, it creates a certain degree of environmental continuity- keeping things consistent from a "botanical capacity" standpoint. Over time, you have the opportunity to establish a "baseline" of water parameters, knowing how many of what to add to keep things more-or-less consistent, which could make the regular "topping off" of botanicals a bit more of a "science" in addition to an "art."

In addition, it keeps a consistent aesthetic "vibe" in your aquarium. Consistent, in that you can keep the sort of "look" you have, while making subtle- or even less-than-subtle "enhancements" as desired.

Yeah, dynamic.

And, of course, "topping off" botanicals helps keeps you more intimately "in touch" with your aquarium, much in the same way a planted tank enthusiast would by trimming plants, or a reefer while making frags. When you're actively involved in the "operation" of your aquarium, you simply notice more. You can also learn more; appreciate the subtle, yet obvious changes which arise on an almost daily basis in our botanical-style aquariums.

I dare say that one of the things I enjoy doing most with my blackwater, botanical-style aquariums (besides just observing them, of course) is to "top off" the botanical supply from time to time. I feel that it not only gives me a sense of "actively participating" in the aquarium- it provides a sense that you're doing something nature has done for eons; something very "primal" and essential. Even the prep process is engaging.

Think about the materials which accumulate in natural aquatic habitats, and how they actually end up in them, and it makes you think about this in a very different context. A more "holistic" context that can make your experience that much more rewarding. Botanicals should be viewed as "consumables" in our hobby- much like activated carbon, filter pads, etc.- they simply don't last indefinitely.

Many seed pods and similar botanicals contain a substance known as lignin. Lignin is defined as a group of organic polymers which are essentially the structural materials which support the tissues of vascular plants. They are common in bark, wood, and yeah- seed pods, providing protection from rotting and structural rigidity.

In other words, they make seed pods kinda tough.

Yet, not permanent.

That being said, they are typically broken down by fungi and bacteria in aquatic environments. Inputs of terrestrial materials like leaf litter and seed pods into aquatic habitats can leach dissolved organic carbon (DOC), rich in lignin and cellulose. Factors like light intensity, mineral hardness, and the composition of the aforementioned bacterial /fungal community all affect the degree to which this material is broken down into its constituent parts in this environment.

Hmm...something we've kind of known for a while, right?

So, lignin is a major component of the "stuff" that's leached into our aquatic environments, along with that other big "player"- tannin.

Tannins, according to chemists, are a group of "astringent biomolecules" that bind to and precipitate proteins and other organic compounds. They're in almost every plant around, and are thought to play a role in protecting the plants from predation and potentially aid in their growth. As you might imagine, they are super-abundant in...leaves. In fact, it's thought that tannins comprise as much as 50% of the dry weight of leaves!

Whoa!

And of course, tannins in leaves, wood, soils, and plant materials tend to be highly water soluble, creating our beloved blackwater as they decompose. As the tannins leach into the water, they create that transparent, yet darkly-stained water we love so much!

In simplified terms, blackwater tends to occur when the rate of "carbon fixation" (photosynthesis) and its partial decay to soluble organic acids exceeds its rate of complete decay to carbon dioxide (oxidation).

Chew on that for a bit...Try to really wrap your head around it...

And sometimes, the research you do on these topics can unlock some interesting tangential information which can be applied to our work in aquairums...

Interesting tidbit of information from science: For those of you weirdos who like using wood, leaves and such in your aquariums, but hate the brown water (yeah, there are a few of you)- you can add baking soda to the water that you soak your wood and such in to accelerate the leaching process, as more alkaline solutions tend to draw out tannic acid from wood than pH neutral or acidic water does. Or you can simply keep using your 8.4 pH tap water!

"ARMCHAIR SPECULATION": This might be a good answer to why some people can't get the super dark tint they want for the long term...If you have more alkaline water, those tannins are more quickly pulled out. So you might get an initial burst, but the color won't last all that long...

I think just having a bit more than a superficial understanding of the way botanicals and other materials interact with the aquatic environment, and how we can embrace and replicate these systems in our own aquariums is really important to the hobby. The real message here is to not be afraid of learning about seemingly complex chemical and biological nuances of blackwater systems, and to apply some of this knowledge to our aquatic practice.

It can seem a bit intimidating at first, perhaps even a bit contrarian to "conventional aquarium practice", but if you force yourself beyond just the basic hobby-oriented material out there on these topics (hint once again: There aren't many!), there is literally a whole world of stuff you can learn about!

It starts by simply looking at Nature as an overall inspiration...

Wondering why the aquatic habitats we're looking at appear the way they do, and what processes create them. And rather than editing out the "undesirable" (by mainstream aquarium hobby standards) elements, we embrace as many of the elements as possible, try to figure out what benefits they bring, and how we can recreate them functionally in our closed aquarium systems.

There are no "flaws" in Nature's work, because Nature doesn't seek to satisfy observers. It seeks to evolve and change and grow. It looks the way it does because it's the sum total of the processes which occur to foster life and evolution.

We as hobbyists need to evolve and change and grow, ourselves.

We need to let go of our long-held beliefs about what truly is considered "beautiful." We need to study and understand the elegant way Nature does things- and just why natural aquatic habitats look the way they do. To look at things in context. To understand what kinds of outside influences, pressures, and threats these habitats face.

And, when we attempt replicate these functions in our aquariums, we're helping to grow this unique segment of the aquarium hobby.

Please make that effort to continue to educate yourself and get really smart about this stuff...And share what you learn on your journey- all of it- the good and the occasional bad. It helps grow the hobby, foster a viable movement, and helps your fellow hobbyists!

Stay studious. Stay thoughtful. Stay inquisitive. Stay creative. Stay engaged...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

What our fishes eat...The wonder of food webs.

Yes, I admit that we talk about some rather obscure topics around here. Yet, many of these topics are actually pretty well known, and even well-understood by science. We just haven't consciously applied them to our aquarium work...yet.

One of the topics that we talk about a lot are food webs. To me, these are fascinating, fundamental constructs which can truly have important influence on our aquariums.

So, what exactly is a food web?

A food web is defined by aquatic ecologists as a series of "trophic connections" (ie; feeding and nutritional resources in a given habitat) among various species in an aquatic community.

All food chains and webs have at least two or three of these trophic levels. Generally, there are a maximum of four trophic levels. Many consumers feed at more than one trophic level.

So, a trophic level in our case would go something like this: Leaf litter, bacteria/fungal growth, crustaceans...

In the wild aquatic habitats we love so much, food webs are vital to the organisms which live in them. They are an absolute model for ecological interdependencies and processes which encompass the relationship between the terrestrial and aquatic environments.

In many of the blackwater aquatic habitats that we're so obsessed with around here, like the Rio Negro, for example, studies by ecologists have determined that the main sources of autotrophic sources are the igapo, along with aquatic vegetation and various types of algae. (For reference, autotrophs are defined as organisms that produce complex organic compounds using carbon from simple substances, such as CO2, and using energy from light (photosynthesis) or inorganic chemical reactions.)

Hmm. examples would be phytoplankton!

Now, I was under the impression that phytoplankton was rather scarce in blackwater habitats. However, this indicates to scientists is that phytoplankton in blackwater trophic food webs might be more important than originally thought!

Now, lets get back to algae and macrophytes for a minute. Most of these life forms enter into food webs in the region in the form of...wait for it...detritus! Yup, both fine and course particular organic matter are a main source of these materials. I suppose this explains why heavy accumulations of detritus and algal growth in aquaria go hand in hand, right? Detritus is "fuel" for life forms of many kinds.

In Amazonian blackwater rivers, studies have determined that the aquatic insect abundance is rather low, with most species concentrated in leaf litter and wood debris, which are important habitats. Yet, here's how a food web looks in some blackwater habitats : Studies of blackwater fish assemblages indicated that many fishes feed primarily on burrowing midge larvae (chironomids, aka "Bloodworms" ) which feed mainly with organic matter derived from terrestrial plants!

And of course, allochtonous inputs (food items from outside of the ecosystem), like fruits, seeds, insects, and plant parts, are important food sources to many fishes. Many midwater characins consume fruits and seeds of terrestrial plants, as well as terrestrial insects.

Insects in general are really important to fishes in blackwater ecosystems. In fact, it's been concluded that the the first link in the food web during the flooding of forests is terrestrial arthropods, which provide a highly important primary food for many fishes.

These systems are so intimately tied to the surrounding terrestrial environment. Even the permanent rivers have a strong, very predictable "seasonality", which provides fruits, seeds, and other terrestrial-originated food resources for the fishes which reside in them. It's long been known by ecologists that rivers with predictable annual floods have a higher richness of fish species tied to this elevated rate of food produced by the surrounding forests.

And of course, fungal growths and bacterial biofilms are also extremely valuable as food sources for life forms at many levels, including fishes. The growth of these organisms is powered by...decomposing leaf litter!

Sounds familiar, huh?

So, how does a leaf break down? It's a multi-stage process which helps liberate its constituent compounds for use in the overall ecosystem. And one that is vital to the construction of a food web.

The first step in the process is known as leaching, in which nutrients and organic compounds, such as sugars, potassium, and amino acids dissolve into the water and move into the soil.The next phase is a form of fragmentation, in which various organisms, from termites (in the terrestrial forests) to aquatic insects and shrimps (in the flooded forests) physically break down the leaves into smaller pieces.

As the leaves become more fragmented, they provide more and more surfaces for bacteria and fungi to attach and grow upon, and more feeding opportunities for fishes!

Okay, okay, this is all very cool and hopefully, a bit interesting- but what are the implications for our aquariums? How can we apply lessons from wild aquatic habitats vis a vis food production to our tanks?

This is one of the most interesting aspects of a botanical-style aquarium: We have the opportunity to create an aquatic microcosm which provides not only unique aesthetics- it provides nutrient processing, and to some degree, a self-generating population of creatures with nutritional value for our fishes, on a more-or-less continuous basis.

Incorporating botanical materials in our aquariums for the purpose of creating the foundation for biological activity is the starting point. Leaves, seed pods, twigs and the like are not only "attachment points" for bacterial biofilms and fungal growths to colonize, they are physical location for the sequestration of the resulting detritus, which serves as a food source for many organisms, including our fishes.

Think about it this way: Every botanical, every leaf, every piece of wood, every substrate material that we utilize in our aquariums is a potential component of food production!

The initial setup of your botanical-style aquarium will rather easily accomplish the task of facilitating the growth of said biofilms and fungal growths. There isn't all that much we have to do as aquarists to facilitate this but to simply add these materials to our tanks, and allow the appearance of these organisms to happen.

You could add pure cultures of organisms such as Paramecium, Daphnia, species of copepods (like Cyclops), etc. to help "jump start" the process, and to add that "next trophic level" to your burgeoning food web.

In a perfect world, you'd allow the tank to "run in" for a few weeks, or even months if you could handle it, before adding your fishes- to really let these organisms establish themselves. And regardless of how you allow the "biome" of your tank to establish itself, don't go crazy "editing" the process by fanatically removing every trace of detritus or fragmented botanicals.

When you do that, you're removing vital "links" in the food chain, which also provide the basis for the microbiome of our aquariums, along with important nutrient processing.

So, to facilitate these aquarium food webs, we need to avoid going crazy with the siphon hose! Simple as that, really!

Yeah, the idea of embracing the production of natural food sources in our aquariums is elegant, remarkable, and really not all that surprising. They will virtually spontaneously arise in botanical-style aquariums almost as a matter of course, with us not having to do too much to facilitate it.

It's something that we as a hobby haven't really put a lot of energy in to over the years. I mean, we have spectacular prepared foods, and our understanding of our fishes' nutritional needs is better than ever.

Yet, there is something tantalizing to me about the idea of our fishes being able to supplement what we feed. In particular, fry of fishes being able to sustain themselves or supplement their diets with what is produced inside the habitat we've created in our tanks!

A true gift from Nature.

I think that we as botanical-style aquarium enthusiasts really have to get it into our heads that we are creating more than just an aesthetic display. We need to focus on the fact that we are creating functional microcosms for our fishes, complete with physical, environmental, and nutritional aspects.

Food production- supplementary or otherwise- is something that not only is possible in our tanks; it's inevitable.

I firmly believe that the idea of embracing the construction (or nurturing) of a "food web" within our aquariums goes hand-in-hand with the concept of the botanical-style aquarium. With the abundance of leaves and other botanical materials to "fuel" the fungal and microbial growth readily available, and the attentive husbandry and intellectual curiosity of the typical "tinter", the practical execution of such a concept is not too difficult to create.

We are truly positioned well to explore and further develop the concept of a "food web" in our own systems, and the potential benefits are enticing!

Work the web- in your own aquarium!

Stay curious. Stay observant. Stay creative. Stay diligent. Stay open-minded...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

The natural "intangibles" of botanical materials

Even with the exploding popularity of botanical-style aquariums, I still receive many questions from hobbyists unfamiliar with our practice, asking what the purpose or benefit is of utilizing these materials in our tanks. I find myself repeating the mantra that this is not purely an aesthetic statement.

Utilizing natural botanical materials in our aquariums is not an aquascaping style; rather, it's a methodology for creating and managing a biologically diverse closed aquatic ecosystem.

There is also something very different about the way that our fishes behave when they are living in an environment which has an abundance of natural materials present.

I know, it sounds a bit weird, but it's true! We receive lots of comments about this. It's sort of an "intangible" that comes with using them in our tanks. And I suppose it makes a lot of sense, as the fishes are utilizing them much as they do in their wild habitats, for shelter, grazing, and spawning.

Now sure, in a tank devoid of natural materials like botanicals, fishes will utilize whatever materials are available to shelter among, graze, and even spawn (hello, "spawning cones" and cracked flower pots!). Yet, there is a certain "something" that's different when you use botanicals. You can just see it.

Of course, with botanical materials, you have the added benefit that they are natural materials, consisting of substances like lignin, and they can impart other compounds stored in their tissues, such as tannin and humic substances, into the surrounding water column. And many fishes feed directly on the botanicals themselves, or remove "biocover" from their surfaces.

Yeah, think about it:

The texture and chemical composition of the botanicals' exteriors is really well-suited for the recruitment and growth of biofilms and fungal populations- important for the biological diversity and "operating system" of the aquarium, as we've talked about numerous times here. This is such an easily overlooked benefit of using natural materials in the aquarium.

And of course, as we know, terrestrial botanical materials, when submerged in water for extended periods of time, decompose. If there is one aspect of our botanical-style aquariums which fascinates me above almost anything else, it's the way they facilitate the natural processes of life- specifically, decomposition.

Decomposition is fundamental to the botanical style aquarium.

We use this term a lot around here...What, precisely does it mean?

de·com·po·si·tion- dēˌkämpəˈziSH(ə)n -the process by which organic substances are broken down into simpler organic matter.

A very apt descriptor, if you ask me!

We add leaves and botanicals to our aquariums, and over time, they start to soften, break up, and ultimately, decompose. Decomposition of leaves and botanicals not only liberates the substances contained within them (lignin, organic acids, and tannins, just to name a few) into the water- it serves to nourish bacteria, fungi, and other microorganisms and crustaceans, facilitating basic "food web" within the botanical-style aquarium, just like it does in Nature- if we allow it to!

PVC pipe sections, flower pots, and plastic plants can't do THAT!

Utilizing botanical materials and leaves in your tank, and leaving them in until they fully decompose is as much about your aesthetic preferences as it is long-term health of the aquarium.

It's a decision that each of us makes based on our tastes, management "style", and how much of a "mental shift" we've made into accepting the transient nature of materials in a botanical-style aquarium and its function. There really is no "right" or "wrong" answer here. It's all about how much you enjoy what happens in Nature versus what you can control in your tank. Nature will utilize them completely, as she does in the wild.

I tend to favor Nature, of course. But that's just me.

And of course, we can't ever lose sight of the fact that we're creating and adding to a closed aquatic ecosystem, and that our actions in how we manage our tanks must map to our ambitions, tastes, and the "regulations" that Nature imposes upon us.

Yes, anything that you add into your aquarium that begins to break down is bioload.

Everything that imparts proteins, organics, etc. into the water is something that you need to consider. However, it's always been my personal experience and opinion that, in an otherwise well-maintained aquarium, with regular attention to husbandry, stocking, and maintenance, the "burden" of botanicals in your water is surprisingly insignificant.

Even in test systems, where I intentionally "neglected" them by conducting sporadic water exchanges, once I hit my preferred "population" of botanicals (by buying them up gradually), I have never noticed significant phosphate or nitrate increases that could be attributed to their presence.

Understand that the process of decomposition is a fundamental, necessary function that occurs in our aquariums on a constant basis, and that botanicals are the "fuel" which drives this process. Realize that in the botanical-style aquarium, we are, on many levels, attempting to replicate the function of natural habitats- and botanical materials are just part of the equation.

And of course, these botanical materials not only offer unique natural aesthetics- they offer enrichment of the aquatic habitat through their release of tannins, humic acids, vitamins, etc. as they decompose- just as they do in Nature.

Leaves and such are simply not permanent additions to our 'scapes, and if we wish to enjoy them in their more "intact" forms, we will need to replace them as they start to break down. This is not a bad thing. It just requires us to "do some stuff" if we are expecting a specific aesthetic.

This is very much replicates the process which occur in Nature, doesn't it? Stuff like seed pods and leaves either remains "in situ" as part of the local habitat, or is pushed downstream by wind, current, etc. - and new materials continuously fall into the waters to replace the old ones.

Pretty much everything we do in a botanical-style blackwater aquarium has a "natural analog" to it!

Despite their impermanence, these materials function as diverse harbors of life, ranging from fungal and biofilm mats, to algae, to micro crustaceans and even epiphytic plants. Decomposing leaves, seed pods, and tree branches make up the substrate for a complex web of life which helps the fishes that we're so fascinated by flourish.

Intangibles? Perhaps. Yet, highly beneficial and consequential ones, indeed.

Stay persistent. Stay bold. Stay consistent. Stay observant...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Stuff we've been told to fear...

A couple of days back, I was chatting with a fellow hobbyist who wanted to jump in to something a bit different within the aquarium hobby, but was afraid of the possible consequences-both socially and in his aquariums. He feared criticism from "them", and that just froze him. I felt bad that he was so afraid of criticism from others should he question the "status quo" within the hobby.

Perhaps my story might be helpful to you if you're afraid of such criticisms.

For generations, we've been told in the aquarium hobby that we need to be concerned about the appearance of all kinds of stuff in our tanks, like algae, detritus, and "biocover".

For some strange reason, we as a hobby group seems emphasize stuff like understanding some biological processes, like the nitrogen cycle, yet we've also been told to devote a lot of resources to siphoning, polishing, and scrubbing our tanks to near sterility.

It's a strange dichotomy.

I remember the first few botanical-style tanks I created, almost two decades ago now, would hit that phase early on when biofilms and fungal growths began to appear, and I'd hear my friends telling me, "Yeah, your tank is going to turn into a big pile of shit. Told you that you can't put that stuff in there."

Because that's what they've been told. The prevailing mindset in the hobby was that the appearance of these organisms was an indication of an unsuitable aquarium environment.

Anyone who's studied basic ecology and biology understands that the complete opposite is true. The appearance of these valuable life forms is an indicator that your aquatic environment is ideal to foster a healthy, diverse community of aquatic organisms, including fishes!

Exactly like in Nature.

I remember telling myself that this is what I knew was going to happen. I knew how biofilms and fungal growths appear on "undefended" surfaces, and that they are essentially harmless life forms, exploiting a favorable environment. I knew that fungi appear as they help break down leaves and botanicals. I knew that these are perfectly natural occurrences, and that they typically are transitory and self-limiting to some extent.

Normal for this type of aquarium approach. I knew that they would go away, but I also knew that there would be a period of time when the tank might look like a big pool of slimy shit. Or, rather, it'd look like a pile of slimy shit to those who weren't familiar with these life forms, how they grow, and how the natural aquatic habitats we love so much actually function and appear!

To reassure myself, I would stare for hours at underwater photos taken in the Amazon region, showing decaying leaves, biofilms,and fungi all over the leaf litter. I'd read the studies by researchers like Henderson and Walker, detailing the dynamics of leaf litter zones and how productive and unique they were.

I'd pour over my water quality tests, confirming for myself that everything was okay. It always was. And of course I would watch my fishes for any signs of distress...

I never saw them.

I knew that there wouldn't be any issues, because I created my aquariums with a solid embrace of basic aquatic biology; an understanding that an aquarium is not some sort of underwater art installation, but rather, a living, breathing microcosm of organisms which work together to create a biome..and that the appearance of the aquarium only tells a small part of the story.

I knew that this type of aquatic habitat could be replicated in the aquarium successfully. I realized that it would take understanding, trial and error, and acceptance that the aquariums I created would look fundamentally different than anything I had experienced before.