- Continue Shopping

- Your Cart is Empty

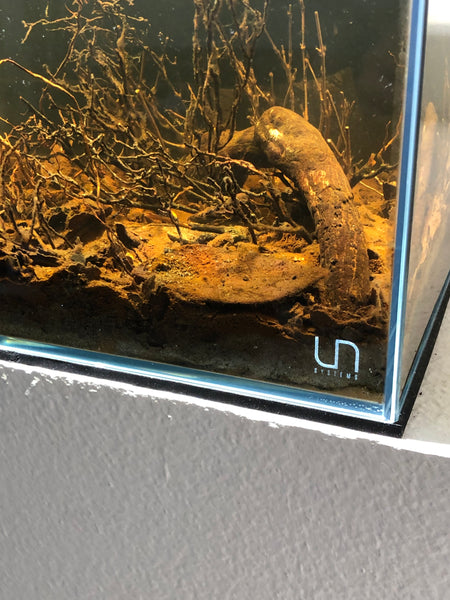

For the love of weird substrates...

One of the "cornerstones" of our botanical-method aquarium practice is the use of substrate. Specifically, substrate materials which can influence- or make it easier to influence- water chemistry in the aquarium, as well as to help foster a "microbiome" of small organisms which will provide ecological diversity for the system.

Substrates, IMHO, are one of the most often-overlooked components of the aquarium. We tend to just add a bag of "_____________" to our tanks and move on to the "more exciting" stuff like rocks and "designer" wood. It's true! Other than planted aquarium enthusiasts, the vast majority of hobbyists seem to have little more than a passing interest in creating and managing a specialized substrate or associated ecology.

A real pity, especially for those of us who are interested in botanical-method aquariums, which replicate natural aquatic habitats where soils and geology play a HUGE role in influencing the environmental parameters of these ecosystems. And in the hobby, we've largely overlooked the benefits and possibilities which specialized substrates can offer.

So I started to experiment with materials to recreate some of the characteristics of wild aquatic habitats which fascinated me. And an obsession was born.

I started playing with substrates mainly because I couldn't find exactly what I was looking for on the market. This is not some indictment of the major substrate manufacturers out there...I LOVE almost all of them and use and happily recommend ones that I like. I'm obsessed with substrates. I think that the companies which produce them are among the coolest of the cool aquatics industry brands. If I wasn't doing this botanical thing with Tannin, I'd probably have started a company that specializes in substrates for aquariums. Seriously.

And the fact is, the major manufacturers need to market products that more than like 8 people are interested in. It's unreasonable to think that they'd devote precious resources to creating a product that would be geared to such a tiny target.

And of course, being one of those 8 people who are geeked-out about weird substrates, I decided that I'd "scratch my own itch" (as we did with the botanical thing..) and formulate and create some of my own. Thus, the NatureBase product line was born!

I realized that the specialized world which we operate in embraces some different ideas, unusual aesthetics, and is fascinated by the function of the environments we strive to replicate. These are important distinctions between what we are doing with substrates at Tannin, and what the rest of the aquarium hobby is doing.

Our NatureBase line is not intended to supersede or completely replace the more commonly available products out there as your "standard" aquarium substrate, because: a) they're more expensive, b) they're not specifically "aesthetic enhancements", c) they are not intended to be planted aquarium substrates, and d) because of their composition, they'll add some turbidity and tint to the aquarium water, at least initially (not everyone could handle THAT!)

So, right there, those factors have significantly segmented our target market...I mean, we're not trying to be the aquarium world's "standard substrate", they weren't formatted to grow aquatic plants, we're not marketing them just for the cool looks, and we can't emphasize enough that they will make your water a bit turbid when first submerged. If you have fishes which dig, or which like to "work" the substrate, you may see a near-continuous turbidity in your aquarium!

Oh, joy.

Those factors alone will take us out of contention for large segments of the market!

This is important to grasp.

I mean, these substrates are intended to be used in more natural, botanical-style/biotope-inspired aquariums. Our first two releases, "Igapo" and "Varzea", are specific to the creation of a type of "cyclical" terrestrial/aquatic feature. They do exactly what I wanted them to do, and they were specifically intended for use in specialized set ups, like the "Urban Igapo" idea we've been talking about for a long time here, as well as brackish water mangrove environments, etc.

Let's touch on the "aesthetic" part for a minute.

Most of our NatureBase substrates have a significant percentage of clays and sediments in their formulations. These materials have typically been something that aquarists have avoided, because they will cloud the water for a while, and often impart a bit of color. We also have some botanical components in a few of our substrates, because they are intended to be "terrestrial" substrates for a while before being flooded...and when this stuff is first wetted, some of it will float.

And that means that you're going to have to net it out, or let your filter take it out. You simply won't have that "issue" with your typical bag of aquarium sand!

Shit, you're probably just frothing right now, waiting to cloud and dirty up your aquariums with this stuff, huh?

No?

I can't for the life of me figure out why not? ;)

Remember, some of these substrates were formulated for a very specific purpose: To replicate the terrestrial soils which are seasonally inundated in the wild. As such, these products simply won't look or act like your typical aquarium substrate materials!

Scared off completely yet? I hope not.

Why include sediments and clays in our mixes?

Well, for one thing, sediments are an integral part of the natural substrates in the habitats from which our fishes come. So, they're integral to our line. In fact, I suppose you'd best classify NatureBase products as "sedimented substrates."

Think about this: Many of our favorite habitats are forest floors and meadows which undergo periodic flooding cycles in the Amazon, which results in the creation of aquatic habitats for a remarkable diversity of fish species.

Depending on the type of water that flows from the surrounding rivers, the characteristics of the flooded areas may vary. Another important impact is the geology of the substrates over which the rivers and streams pass. This results in differences in the physical-chemical properties of the water.

In the Amazon, areas flooded by rivers of black or clear waters, with acid pH and low sediment load, in addition to being nutritionally poor, are called “igapó."

The flooding often lasts for several weeks or even several months, and the plants and trees need special biochemical adaptations to be able to survive the lack of oxygen around their roots. We've talked about this a lot here over the years.

Forest floor soils in tropical areas are known by soil geologists as "oxisols", and have varying amounts of clay, sediments, minerals like quartz and silica, and various types of organic matter. So it makes sense that when flooded, these "ingredients" will have significant impact on the aquatic environment. This "recipe" is not only compositionally different than typical "off-the-shelf" aquarium sands and substrates- it looks and functions differently, too.

YOU DON'T RINSE THEM BEFORE USE!

You CAN wet them right away; you don't have to do a "wet/dry season" igapo-style tank with them. However, you should be ready for some cloudy water for a week or more! And again, if you have fishes which like to "work" the substrate, it will be a near-constant thing, the degree to which it will be is based on the habits of the fishes you keep.

And that's where a lot of people will metaphorically "leave the room."Turbid, darker water is a guaranteed "freak out" for a super-high high percentage of aquarists.

So, yeah, you'll have to make a mental shift to appreciate a different look and function.

And many hobbyists simply can't handle that. I've been extremely up front with this stuff since the introduction of these substrates, to ward off the, "I added NatureBase to my tank and it looks like a cloudy mess! This stuff is SHIT!" type of emails that inevitably come when people don't read up first before they purchase the stuff. (And trust me- the fact that you're even reading this blog, or listening to this podcast puts you in the tiniest minority of aquarium hobbyists!)

Let's talk a bit about how to "live" with these substrates.

There are a lot of different ways to use these substrates in all sorts of tanks. I mean, if you want some of the benefits and want to geek out and experiment with them, you can use a "sand cap" of whatever conventional substrate you prefer on top, and likely limit the turbidity somewhat, much like the practice of aquarists who employ "dirted" substrates do.

Oh, and the plant thing...

We're asked a LOT if these substrates can grow aquatic plants. Now, although they were intended to facilitate the growth of terrestrial plants, like grasses, the fact is, both our customers and ourselves have seen pretty damn good plant growth in tanks using this stuff!

Our Igapo and Varzea substrates mimic sandy acidic soils that have a low nutrient content. And, as you know, the color and acidity of the floodwater is due to the acidic organic humic substances (tannins) that dissolve into it. The acidity from the water translates into acidic soils, which makes sense, right?

Now, I admit, I am NOT a geologist, and I'm not expert in soil science. I know enough to realize that, in order to replicate the types of habitats I am fascinated with, it required different materials. If you ask me, "Will this fish do well with this materials?" or, "Can I grow "Cryptocoryne in this?", or "Does this make a good substrate for shrimp tanks?" I likely won't have a perfect answer. Sorry.

Periodically, plant enthusiasts will ask me about the "cation exchange capacity" of our substrate. Cation Exchange Capacity (CEC) is the ability of a material to absorb positively-charged nutrient ions. This means the substrate will hold nutrients and make them available for the plant roots, and therefore, plant growth. CEC measures the amount of nutrients, more specifically, positivity changed ions, which a substrate can hold onto/store for future use by aquatic plants.

Thus, a "high CEC" is important to many aquatic plant enthusiasts in their work. While it means that the substrate will hold nutrients and make them available for the plant roots. it doesn't indicate the amount of nutrients the substrate contains.

For reference, scientists measure cation exchange capacity (CEC) in milliequivalents per 100 grams ( meq/100g).

To really get "down and dirty" to analyze substrates scientifically, CEC determinations are often done by a process called "Method 9081A of EPA SW- 846." What the....? CEC extractions are often also analyzed on ICP-OES systems. A rather difficult and pretty expensive process, with equipment and methods that are not something casual hobbyists can easily replicate!

As you might suspect, CEC varies widely among different materials. Sand, for instance, has a CEC less than 1 meq/100 g. Clays tend to be over 30 meq/100 g. Stuff like natural zeolites are around 100 meq/100g! Soils and humus may have CEC up to 250 meq/100g- that's pretty serious!

What nutrients are we talking about here? The most common ones which come into play in the context of CEC are iron, potassium, calcium and magnesium. So, if you're into aquatic plants, high CEC is a good thing!

Of course, this is where the questions arise around the substrates we play with.

It makes sense, right?

Our "Nature Base" substrates do contain materials such as clays and silts, which could arguably be considered "higher CEC" materials, because they're really fine- and because higher surface area generally results in a higher CEC. The more surface area there is, the more potential bonding sites there are for the exchange to take place. Alas, nothing is ever exactly what we hope it should be in this hobby, and clays are often not all that high in their CEC "ratings."

Now, the "Nature Base" substrates are what we like to call “sedimented substrates”, because they are not just sand, or pellets of fired clays, etc. They are a mix of materials, and DO also have some terrestrial soils in the mix, too, which are also likely higher in CEC. And no, we haven't done CEC testing with our substrates...It's likely that in the future, some enthusiastic and curious scientist/hobbyist might just do that, of course!

Promising, from a CEC standpoint, I suppose!

However, again, I must emphasize that they were really created to replicate the substrate materials found in the igapo and varzea habitats of South America, and the overall habitat- more "holistically conceived"-not specifically for plant growth. And, in terrestrial environments like the seasonally-inundated igapo and varzea, nutrients are often lost to volatilization, leaching, erosion, and runoff..

So, it's important for me to make it clear again that these substrates are more representative of a terrestrial soil. Interestingly, the decomposition of detritus and leaves and such in our botanical-method aquariums and "Urban Igapo" displays is likely an even larger source of “stored” nutrients than the CEC of the substrate itself, IMHO. Thus, they will provide a home for beneficial bacteria- breaking down organics and helping to make them more available for plant growth.

Perhaps that's why aquatic plants grow so well in botanical-method aquariums?

Yeah, the stuff DOES grow aquatic and riparian plants and grasses quite well, in our experience! Yet, again- I would not refer to them specifically as "aquatic plant substrates." They're not being released to challenge or replace the well-established aquatic plant soils out there. They're not even intended to be compared to them!

Remember, our "Igapo" and "Varzea" substrates are intended to start out life as "terrestrial" materials, gradually being inundated as we bring on the "wet season." And because of the clay and sediment content of these substrates, you'll see some turbidity or cloudiness in the water. It won't immediately be crystal-clear- just like in Nature. That won't excite a typically planted aquarium lover, for sure.

I can't stress it often enough: With our emphasis on the "wholistic" application of our substrate, our focus is on the "big picture" of these closed aquatic ecosystems.

I'll be the first to tell you that, while I have experimented with many species of plants, inverts, and fishes with these substrates, I can't tell you that every single fish or plant will like them. You'll simply have to experiment!

Well, shit- that's not something that you typically hear an aquarium hobby brand tell you to do with their products every day, huh? Like, I'm not going to make all sorts of generalized statements about everything I think that these products can do. It would be very unhelpful. I'd rather focus on how they perform in the types of systems in which they were intended to work in, and what the possible downsides could be!

The whole point here is that these substrates are perfect for a whole range of applications. They're not "the greatest substrates ever made!" or anything like that. However, they are super useful for replicating the soils of some of our favorite aquatic habitats.

And for doing some of those geeky experiments that we love so much. So, that pretty much covers the "sedimented" substrate thing for now. Let's talk about "alternative" substrates for a bit...

PT.2 : "ALTERNATIVE SUBSTRATES" AND THE "DANGERS" FROM WITHIN?

In my experience, and in the reported experiences from hundreds of aquarists who play with botanical materials breaking down in and on their aquariums' substrates, undetectable nitrate and phosphate levels are typical for this kind of system. When combined with good overall husbandry, it makes for incredibly stable systems.

I've been thinking through further refinements of the "deep botanical bed"/sand substrate relationship. I've been spending a lot of time researching natural aquatic systems and contemplating how we can translate some of this stuff into our closed system aquaria.

Now, I realize, when contemplating really deep aggregations of substrate materials in the aquarium, that we're dealing with closed systems, and the dynamics which affect them are way different than those in Nature, for the most part.

And I realize that experimenting with these unusual approaches to substrates requires not only a sense of adventure, a direction, and some discipline- but a willingness to accept and deal with an entirely different aesthetic than what we know and love. And this also includes pushing into areas and ideas which might make us uncomfortable, not just for the way they look, but for what we are told might be possible risks.

One of the things that many hobbyists ponder when we contemplate creating deep, botanical-heavy substrates, consisting of leaves, sand, and other botanical materials is the possible buildup of hydrogen sulfide, CO2, and other undesirable compounds within the substrate.

Well, it does make sense that if you have a large amount of decomposing material in an aquarium, that some of these compounds are going to accumulate in heavily-"active" substrates. Now, the big "bogeyman" that we all seem to zero in on in our "sum of all fears" scenarios is hydrogen sulfide, which results from bacterial breakdown of organic matter in the total absence of oxygen.

Let's think about this for just a second.

In a botanical bed with materials placed on the substrate, or loosely mixed into the top layers, will it all "pack down" enough to the point where there is a complete lack of oxygen and we develop a significant amount of this reviled compound in our tanks? I just don't think so. I think that we're more likely to see some oxygen in this layer of materials, and I can't help but speculate- and yeah, it IS just speculation- that actual de-nitirifcation (nitrate reduction), which lowers nitrates while producing free nitrogen, might actually be able to occur in a "(deep) botanical" bed.

And it's certainly possible to have denitrification without dangerous hydrogen sulfide levels. As long as even very small amounts of oxygen and nitrates can penetrate into the substrate, this will not become an issue for most systems. I personally have yet to see a botanical-method aquarium where the material has become so "compacted" as to appear to have no circulation whatsoever within the botanical layer.

Now, sure, I'm not a scientist, and I base this on the management of, and close visual inspection of numerous aquariums, as well as the basic chemical tests I've run on my systems under a variety of circumstances. As one who has made it a point to keep my botanical-method aquariums in operation for very extended time frames, I think this is significant. The "bad" side effects we're talking about should manifest over these longer time frames...and they just haven't.

And then there's the question of nitrate.

Although not the terror that ammonia and nitrite are known to be, nitrate accumulation is something a lot of hobbyists are concerned with. As nitrate accumulates, fish will eventually suffer some health issues. Ideally, we strive to keep our nitrate levels no higher than 5-10ppm in our aquariums.

As a reef aquarist, I was always of the "...keep it as close to zero as possible." mindset, until I realized that corals just grow better with the presence of some nitrate! This was especially evident in my large scale coral grow-out raceways.

It seems that 'zero" nitrate is not always the most realistic or achievable target in a heavily-botanical-laden aquarium, although I routinely see undetectable nitrate reading in my tanks. You have a bit more "wiggle room", IMHO, however, before concern over fish health is a factor. Now, when you start creeping towards 50ppm, you're getting closer towards a number that should alert you.

It's not a big "stretch" from 50ppm to more potentially detrimental readings of 75ppm and higher...

And then you get towards the range where health issues could manifest themselves in your fishes. Now, many fishes will not show any symptoms of nitrate poisoning until the nitrate level reaches 100 ppm or more. However, studies have shown that long-term exposure to moderate concentrations of nitrate stresses fishes, making them more susceptible to disease, affecting their growth rates, and inhibiting spawning in many species.

At those really high nitrate levels, fishes will become noticeably lethargic, and may have other health issues that are obvious upon visual inspection, such as open sores or reddish patches on their skin. And then, you'd have those "mysterious deaths" and the sudden death (essentially from shock) of newly-added fishes to the aquarium, because they're not acclimated to the higher nitrate concentrations.

Okay, that's scary stuff. However, high nitrate concentrations are not only manageable- they're something that's completely avoidable in our aquairums.

Quite honestly, even in the most heavily-botanical-laden systems I've played with, I have personally never seen a higher nitrate reading than around 5ppm. Often, as I mentioned above, they're undetectibIe on hobby-level test kits. I attribute this to common sense stuff: Good quality source water (RO/DI), careful stocking, feeding, good circulation, not disturbing the substrate, and consistent basic aquarium husbandry practices (water exchanges, filter maintenance, etc.).

Now, that's just me.

I'm no scientist, certainly not a chemist, but I have a basic understanding of maintaining a healthy nitrogen cycle in the aquarium. And I am habitual-perhaps even obsessive- about consistent maintenance. Water exchanges are not a "when I get around to it" thing in my aquarium management "playbook"- they're "baked in" to my practice.

So yeah, although nitrate is something to be aware of in botanical-method aquariums, it's simply not an ominous cloud hanging over our success.

Relatively shallow sand or substrate beds seem to be optimal for denitrification, and many of us employ them for the aesthetics as well. Light "stirring" of the top layers, if you're concerned about any potential "dead spots" is something that is permissible, IMHO. Any debris stirred up can easily be removed mechanically by filtration, as mentioned above.

But that's it.

Of course, as we already discussed, you don't have to go crazy siphoning the shit (literally!) out of your sand every week, essentially decimating populations of beneficial microscopic infauna -or interfering with their function- in the process.

What I am starting to feel more and more confident about is postulating that some form of denitrification occurs in a system with a layer of leaves and botanicals as a major component of the tank.

Now, I know, I have little rigorous scientific information to back up my theory, other than anecdotal observations and even some assumptions. However, there is always an example to look at- Nature.

Of course, Nature and aquariums differ, one being a closed system and the other being "open." However, they both are beholden to the same laws, aren't they? And I believe that the function of the captive leaf litter bed and the wild litter beds are remarkably similar to a great extent.

The thing that fascinates me is that, in Nature, leaf litter beds perform a similar function; that is, fostering biodiversity, nutrient export, and yes- denitrification. Let's take a little look at a some information I gleaned from the study of a natural leaf litter bed for some insights.

In a slow-flowing wild Amazonian stream with a very deep leaf litter bed, observations were made which are of some interest to us. First off, oxygen saturation was 6.7 3 mg/L (about 85% of saturation), conductivity was 13.8 microsemions, and pH was 3.5.

Some of these parameters (specifically the very low pH) are likely difficult to obtain and maintain in the aquarium, but the interesting thing is that these parameters were stable throughout a months-long investigation.

Oxygen saturation was surpassingly low, given the fact that there was some water movement and turbulence when the study was conducted. The researchers postulated that the reduction in oxygen saturation presumably reflects respiratory consumption by the organisms residing in the litter, as well as low photosynthetic generation (which makes sense, because there is no real algae or plant growth in the litter beds).

And of course, such numbers are consistent with the presence of a lot of life in the litter beds.

Microscopic investigation confirmed that the leaf litter was heavily populated with fungi and other microfauna. There was also a significant amount of fish life. Interestingly, the fish population was largely found in the top 12"/30cm of the litter bed, which was estimated to be about 18"/45cm deep. The food web in this type of habitat is comprised largely of fungal and bacterial growth which occurs in the decomposing leaf litter.

Okay, I"m throwing a lot of information here, and doing what I hope is a slightly better-than-mediocre attempt at tying it all together. The principal assertions I'm making are that, in the wild, the leaf litter bed is a very productive place, and has a significant impact on its surroundings, and that it's increasingly obvious to me that many of the same functions occur in an aquarium utilizing leaf litter and botanicals.

"Enriching" a substrate with botanicals, or composing an entire substrate of botanicals and leaves is a very interesting and compelling subject for investigation by hobbyists.

So, three areas of potential investigation for us:

*Use of botanicals and leaves to comprise a "bed" for bacterial growth and denitrification.

*Understanding the chemical/physical impact of the botanical "bed" on an aquarium. (ie, pH, conductivity, etc.)

*Utilization of a botanical bed to create a supplemental food source for the resident fishes.

We've also touched on the idea of a leaf litter/botanical bed as "nursery" for fry, something more and more hobbyists/breeders are confirming is a logical "go-to" thing for them.

Interesting semi-anecdotal observations from my friends in the know suggest that the biofilms for decaying leaves form a valuable secondary food for the fry of fishes such as Discus, Uaru, (after they’re done feeding on their parent’s exuded slime coat) and even Loricariid catfishes. And I've seen juvenile fishes of a variety of species "appear" from my botanical-rich aquariums over the years, fat and happy, apparently deriving some nutrition from the fungi, bacteria, and small crustaceans which live in, on, and among the leaf litter bed.

My own experience with creating leaf-litter-bed-focused aquariums has proven that supplemental food production for the resident fishes is a real "thing" that we need to consider. It's a valid and very exciting approach to creating a functional closed aquatic ecosystem.

We talk about the concept of "substrate enhancement" or "enrichment" a lot in the context of aquatic botanicals (we tend to use the two terms interchangeably).

Again, we're not talking about "enrichment" in the same context as say, planted aquarium guys, with materials put into the substrate specifically for the benefit of plants. However, the addition of botanical and other materials CAN create a sort of organic "mulch" which benefits many aquatic plants!

Rather, "enrichment" in our context refers to the addition of botanical materials for creating a more natural-appearing, natural-functioning substrate- one which provides a haven for microbial life, as well as for small crustaceans, biofilms, and even algae, to serve as a foraging area for our fishes and invertebrates.

We've found over the years of playing with botanical materials that substrates can be really dynamic places, and benefit from the addition of leaves and other materials. For many years, substrates in aquarium were really just sands and gravels. With the popularity of planted aquariums, new materials, like soils and mineral additives, entered into the fray.

With the botanical-method aquarium starting to gain in popularity, now you're seeing all sorts of materials added on and in the substrate...for different reasons of course.

I think the big takeaway is that we should not be afraid to experiment with the idea of mixing various botanical materials into our substrates, particularly if we continue to embrace solid aquarium husbandry practices.

In my opinion, richer, botanically-enhanced substrate provides greater biological diversity and stability for the closed system aquarium.

Is it for everyone?

Not for those not willing to experiment and be diligent about monitoring and maintaining water quality. Not for those who are superficially interested, or just in it for the unique aesthetics it affords.

However, for those of you who are adventurous, experimental, diligent, and otherwise engaged with managing and observing your aquariums, I think it offers amazing possibilities. Not only will you gain some fascinating insights and the benefits of "on-board" nutrient export/environmental "enrichment"- you will also get the aesthetics of a more natural-looking substrate as well.

Like so many things we do in our niche, the "weird" alternative and botanical-enriched substrate approaches are fascinating, dynamic, and potentially ground-breaking for the aquarium hobby. For the adventurous, diligent, and observant aquarist, they present numerous opportunities to learn, explore, and create amazing, function-first aquatic ecosystems.

Who's in?

Stay creative. Stay observant. Stay diligent. Stay thoughtful...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Anything goes? Well, sort of...

The garden suggests there might be a place where we can meet Nature halfway."-Michael Pollan

It's long been suggested that an aquarium is sort of like a garden, right? And, to a certain extent it is. Of course, we can also allow our tanks to evolve on a more-or-less "random" path than the word "garden" implies...

Perhaps one of the most liberating things about our botanical-method aquariums is that there is no set "style" that you have to follow to "arrange" botanical materials in your tank.

When you look at those amazing pictures of the natural habitats we love so much, you're literally bombarded with the "imperfection" and apparent randomness that is Nature. Yet, in all of the "clutter" of an igarape flooded forest, for example, there is a quiet elegance to it. There is a sense that everything is there for a reason- and not simply because it looks good. It IS perfect. Can't we bring this sense to our aquariums?

I think we can...simply by meeting Nature halfway.

To a certain extent, it's "anything goes" in terms of adding materials to represent the wild habitats. I mean, when you think about flooded forest floors and rainforest streams, you're talking about an aggregation of material from the forest that has accumulated via wind, rain, and current. The influences on the "design" are things like how something arrives into the water, and how it gets distributed by water movement.

Nature offers no "style guide."

Rather, she offers clues, based on her processes.

I mean, sure, you could and should certainly use some aesthetic thought in the concept, but when you're trying to recreate what in Nature is a more-or-less random thing, you probably don't want to dwell too much on the concept! You don't want to over-think "random" too much, right? Rather, put your effort into selecting suitable materials with which to do the job.

For a bit more context, just think for just a second, about the stems and branches that we love so much in our aquascaping. Those of us who obsessively study images of the wild tropical habitats we love so much can't help but note that many of the bodies of water which we model our aquariums after are filled with tree branches and stems.

Since many of these habitats are rather ephemeral in nature, they are only filled up with water part of the year. The remainder of the time, they're essentially dry forest floors.

And what accumulates on dry forest floors?

Branches, stems, leaves, and other materials from trees and shrubs. When the waters return, these formerly terrestrial materials become an integral part of the (now) aquatic environment. This is a really, really important thing to think of when we aquascape or contemplate how we will use botanical materials like the aforementioned stems and branches.

They impact both function and aesthetics of an aquarium...Yes, what we call "functional aesthetics" rears its head again!

There is no real rhyme or reason as to why stuff orients itself the way it does once submerged. There are numerous random factors involved.

I mean, branches fall off the trees, a process initiated by either rain or wind, and just land "wherever." Which means that we as hobbyists would be perfectly okay just literally tossing materials in and walking away! Now, I know this is actually aquascaping heresy- Not one serious 'scaper would ever do that...right?

On the other hand, I'm not so sure why they wouldn't!

I mean, what's wrong with sort of randomly scattering stems, twigs, and branches in your aquascape? It's a near-perfect replication of what happens in Nature. Now, I realize that a glass or acrylic box of water is NOT nature, and there are things like "scale" and "ratio" and all of that shit that hardcore 'scapers will hit you over the head with...

But Nature doesn't give a fuck about some competition's "rules"- and Nature is pretty damn inspiring, right? There is a beauty in the brutal reality of randomness. I mean, sure, the position of stones in an "Iwagumi" is beautiful...but it's hardly what I'd describe as "natural."

Natural looks...well, like what you'd see in Nature.

It's pretty hardcore stuff.

And it's all part of the reason that I spend so damn much time pleading with you- my fellow fish geeks- to study, admire, and ultimately replicate natural aquatic habitats as much as you do the big aquascaping contest winners' works. In fact, if every hobbyist spent just a little time studying some of these unique natural habitats and using them as the basis of their work, I think the hobby would be radically different.

When hobbyists interpret what they see in wild aquatic habitats stats more literally, the results are almost always stunning. And contest judges are starting to take notice...

I think that there would also be hobby success on a different level with a variety of fishes that are perhaps considered elusive and challenging to keep. Success based on providing them with the conditions which they evolved to live in over the millennia, not a "forced fit" its what works for us humans.

More awareness of both the function and the aesthetics of fascinating ecological niches, such as the aforementioned flooded forests, would drive the acceptance and appreciation of Nature as it is- not as we like to "edit" and "sanitize" it.

Taking this approach is actually a "stimulus" for creativity, perhaps in ways that many aquarists have not thought of.

There are a lot of aquatic habitats in Nature which are filled with tangles of terrestrial plant roots, emergent vegetation, fallen branches, etc., which fill small bodies of water almost completely.

These types of habitats are unique; they attract a large populations of smaller fishes to the protection of their vast matrix of structures. Submerged fallen tree branches or roots of marginal terrestrial plants provide a large surface area upon which algae, biofilm, and fungal growth occurs. This, in turn, attracts higher life forms, like crustaceans and aquatic insects. Sort of the freshwater version of a reef, from a "functionality" standpoint, right?

Can't we replicate such aquatic features in the aquarium?

Of course we can!

This idea is a fantastic expression of "functional aesthetics." It's a "package" that is a bit different than the way we would normally present an aquarium. Because we as hobbyists hesitate to densely pack an aquarium like this, don't we?

Why do you think this is?

I think that we hesitate, because- quite frankly- having a large mass of tangled branches or roots and their associated leaves and detritus in the cozy confines of an aquarium tends to limit the number, size, and swimming area of fishes, right? Or, because its felt that, from an artistic design perspective, something doesn't "jibe" about it...

Sure, it does limit the amount of open space in an aquarium, which has some tradeoffs associated with it.

On the other hand, I think that there is something oddly compelling, intricate, and just beautiful about complex, spatially "full" aquatic features. Though seldom seen in aquarium work, there is a reason to replicate these systems. And when you take into account that these are actually very realistic, entirely functional representations of certain natural habitats and ecological niches, it becomes all the more interesting!

What can you expect when you execute something like this in the aquarium?

Well, for on thing, it WILL take up a fair amount of space within the tank. Of course. Depending upon the type of materials that you use (driftwood, roots. twigs, or branches), you will, of course, displace varying amounts of water.

Flow patterns within the aquarium will be affected, as will be the areas where leaves, detritus and other botanical materials settle out. You'll need to understand that the aquarium will not only appear different- it'll function differently as well. Yet, the results that you'll achieve- the more natural behaviors of your fishes, their less stressful existence- will provide benefits that you might not have even realized possible before.

This is something which we simply cannot bring up often enough. It's transformational in our aquarium thinking.

The "recruitment" of organisms (algae, biofilms, epiphytic plants, etc.) in, on, and among the matrix of wood/root structures we create, and the "integration" of the wood into other "soft components" of the aquascape- leaves and botanicals is something which occurs in Nature as well as in the aquairum.

This is an area that has been worked on by hobbyists rather infrequently over the years- mainly by biotope-lovers. However, embracing the "mental shifts" we've talked about so much here- allowing the growth of beneficial biocover, decomposition, tinted water, etc.- is, in our opinion, the "portal" to unlocking the many secrets of Nature in the aquarium.

The extraordinary amount of vibrance associated with the natural growth on wood underwater is an astounding revelation. However, our aesthetic sensibilities in the hobby have typically leaned towards a more "sterile", almost "antispetic" interpretation of Nature, eschewing algae, biofilm, etc.

However, a growing number of hobbyists worldwide have began to recognize the aesthetic and functional beauty of these natural occurances, and the realism and I think that the intricate beauty of Nature is starting to eat away at the old "sterile aquascape" mindset just a bit!

And before you naysayers scoff and assert that the emerging "botanical method" aquarium is simply an "excuse for laziness", as one detractor communicated to me not too long ago, I encourage you once again to look at Nature and see what the world underwater really looks like. There is a reason for the diversity, apparent "randomness", and success of the life forms in these bodies of water.

What is it?

It's that these materials are being utilized- by an enormous community of organisms- for shelter, food, and reproduction. Seeing the "work" of these organisms, transforming pristine" wood and crisp leaves into softening, gradually decomposing material, is evidence of the processes of life.

When you accept that seed pods, leaves, and other botanical materials are somewhat ephemeral in nature, and begin to soften, change shape, accrue biofilms and even a patina of algae- the idea of "meeting Nature halfway" makes perfect sense, doesn't it?

You're not stressing about the imperfections, the random patches of biofilm, the bits of leaves that might be present in the substrate. Sure, there may be a fine line between "sloppy" and "natural" (and for many, the idea of stuff breaking down in any fashion IS "sloppy")- but the idea of accepting this stuff as part of the overall closed ecosystem we've created is liberating.

Sure, we can't get every functional detail down- every component of a food web- every biochemical interaction...the specific materials found in a typical habitat- we interpret- but we can certainly go further, and continue to look at Nature as it is, and employ a sense of "acceptance"- and randomness-in our work.

I'm not telling you to turn your back on the modern popular aquascaping scene; to disregard or dismiss the brilliant work being done by aquascapers around the world, or to develop a sense of superiority or snobbery, and conclude that everyone who loves this stuff is a sheep...

Noooooo.

Not at all.

I'm simply the guy who's passing along the gentle reminder from Nature that we have this great source of inspiration that really works! Rejoice in the fact that Nature offers an endless variety of beauty, abundance, and challenge- and that it's all there, free for us to interpret it as we like. Without aesthetic rules, rigid standards, and ratios. The only "rules" are those which govern the way Nature works with materials in an aquatic environment.

A botanical-method aquarium features, life, death, and everything in between.

It pulses with the cycle of life, beholden only to the rules of Nature, and perhaps, to us- the human caretakers who created it.

But mainly, to Nature.

The processes of life which occur within the microcosm we create are indifferent to our desires, our plans, or our aspirations for it. Sure, as humans, we can influence the processes which occur within the aquarium- but the ultimate outcome- the result of everything that we did and did not do- is based solely upon Nature's response.

In the botanical-style aquarium, we embrace the randomness and unusual aesthetic which submerged terrestrial materials impart to the aquatic environment. We often do our best to establish a sense of order, proportion, and design, but the reality is that Nature, in Her infinite wisdom borne of eons of existence, takes control.

It's a beautiful process. Seemingly random, yet decidedly orderly.

Think about that for a bit.

Stay curious. Stay bold. Stay creative. Stay thoughtful...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Form and function meet again...The call of the literal- and the weird.

Every once in a while, someone will ask me what my "style" of aquarium is. And it's a tough one to answer, because the aquariums I create are based less on aesthetics than the are on approach to interpreting natural aquatic habitats in different ways. So, not really a "style" in the conventional sense.

I see myself as a "function first" kind of guy, who's tanks happen look the way they do because they embrace aspects of Nature which create unique environmental conditions that are so compelling. And. to be honest, most aquarists historically haven't found them to be particularly attractive as subjects for aquariums!

This is always a bit sad to me, because some of these "unusual" aspects can create some of the most fascinating and ecologically successful aquariums imaginable, if we can overcome our programmed concerns about their "unconventional" (by hobby standards, anyways) appearance. And with so many super talented aquarists out there, the possibilities for "interpreting Nature more naturally" are endless, if they can get their heads out of the "aesthetics first" mindset!

Now I freely admit that not every aquatic habitat is perfect for replication in the aquarium, or even easy to recreate. Some create operational challenges and require modifications to the way we filter or otherwise manage aquariums. Soem require entirely rethinking how to recreate them in the aquarium. Like, trying to create a (stagnant) puddle seems like it would be pretty easy- and in theory, it is- just add water and mud...

However, in execution, what you often end up with is a stagnant container of water and mud...not particularly exciting or long-term sustainable...or, is it? Personally, I think it is possible. Perhaps you might be advised to "make a better mud hole" and add a few riparian plants to make it a longer-term manageable tank... Or not. That's the beauty...figure out how and you're golden!

I believe that we can do literal interpretations of natural habitats, based on how they form, and what makes them function. Now, maybe we could put a bit of artistic liberty into them, but that's it.

And I freely admit, it's not always easy figuring out how to take these ideas from the "idea phase" to the "set the dsmn thing up phase!" And, for every cool idea I've executed, I must have 5 that never made it out of the initial experimentation phase. And even more which never "made it out of the notebook" of ideas I keep on these things!

And that's okay, because each sort of "aborted" idea gets you closer to the execution of stuff you've really been trying to accomplish. The important takeaway here is to keep experimenting. Figuring out how to create viable aquarium versions of natural aquatic features is both rewarding and- yeah- beautiful!

I admit, it can be somewhat discouraging at times to be playing with all of these seemingly wacky ideas that you have in your head at times, especially when the world's adoring attention on social media are on these incredible, pristine-looking, high-concept planted tanks or whatever. I mean, you want to scream to everyone that this is not that difficult; that it's not "dangerous" or really that "weird"- and that they should give this approach a shot!

It's hard not to sometimes...

Yet, as a lover of truly natural aquariums and ways to interpret Nature in a little glass box of water, you put your head down and soldier on. You don't expect the adorations of others to motivate you.

I remember feeling this exact kind of "loneliness" earlier on in the existence of Tannin. I felt like I existed in this or of almost invisible, "parallel universe", where strange-looking tanks played out in my space, while artistic dreamscapes adorned my Instagram feed.

Yet, in my mind, I always saw the incredible beauty in these truly natural aquariums, supported by organisms and functions that many found extremely distasteful. It was certainly contrary to what all of the "cool kids" were doing! And the sort of jealousy I had for lack of attention dissipated while I kept my head down and simply enjoyed what I was playing with.

The biotope aquairum crowd were my closest comrades; yet even many of them were taking an "aesthetics over function" angle at the time, and it definitely felt a bit more "out there" to be me! All cool.

Again, If you have made the mental shifts to find stuff like decomposing leaves, brown water, detritus, and biofilms attractive and alluring, then it really doesn't matter to you. And it didn't to me. I just kept my head in my game and did my thing.

My work is not intended to be primarily "artistic" or aesthetically-focused, really. Rather, it's an interpretation of the function of the natural world. The form follows the function. I want to inspire others to look at the way natural aquatic habitats evolve and function, and try to replicate as many of the functional aspects of them as possible. If the tank just happens to look interesting- well, that's a sort of collateral benefit, right?

And, when we approach recreating some of these habitats from a "function forward" approach, as opposed to just trying to recreate the look, not only do you create interesting "operational parameters", you get many unusual benefits as well- some of which are analogous to those which the natural environment offers to the organisms which reside there.

And of course, the aesthetics often look substantially different than what you get when you just go "diorama mode." Nature goes to work and brings in Her own "finishing touches" that make it truly unique.

Multiple times in the course of a year, you'll hear me calling to you- our community (someone called it "Tint Nation" once, and I had to laugh) to really push it. I mean, to try stuff that's extremely unconventional; perhaps boundary-pushing...

Aesthetically uncomfortable...even unconvincing for some. But different. Functional. and yeah, I suppose, weird.

Stuff that pushes into "That's some strange shit!" territory. Stuff that, in previous years, would result in a lot of hobbyists telling you stuff like, "It can't work!" "You'll crash your tank!", "It can't be maintained long term!", etc., etc., etc. Stuff that, as a "disciple" of the natural, botanical-method aquarium, will leave (hopefully) asking these naysayers, "Why are you saying that? Because no one has done it before? Or, does the idea just not make sense to YOU?"

Yup. Pushing back on "conventionality" is often a good thing.

There is so much interesting stuff out there to study and replicate in our aquariums. Not just to "diorama it up" to win a biotope aquarium contest; no- but to replicate the form and function of these unique habitats. I say this over and over and over again, because it's a completely different mindset.

I think we need to spend much more time really trying to get our hands around why these natural habitats are the way they are. To understand why they formed, how they "operate", and what set of unique characteristics they possess which makes them home to our beloved fishes.

I feel like I have a "duty" to expose the aquarium world to these unusual aspects of Nature, because they just might lead to some "unlocks" about aspects of the aquatic world that will create beneficial outcomes for our captive fishes, too.

Not just because they're weird.

Not just because replicating them runs contrary to what we've been told is appropriate subject matter for an aquarium. In fact, not all of these things are "weird."Not all of them are impossible or "dangerous" to replicate in the aquarium. Some are simply ideas that have not been "played out" in the confines of an aquarium, for whatever reason.

These ideas-these habitats- are often simply overlooked.

Attempting to replicate the functional aspects of these habitats is simply a "due diligence" thing to me. It will force us to push our skills out a bit; learn something. These ideas are fascinating...

These ideas are cool.

I find it fascinating to consider that many natural habitats are things that not have considered replicating in the past simply because they seemed "dangerous" or "difficult to manage" in an aquarium. I suggest this: They were seen as "dangerous" or "difficult to manage' in an aquarium because we are evaluating them in the lens of conventional aquarium design and management.

When we evaluate unconventional ideas using a conventional mindset, of course they seem unachievable and unmanageable! We talk a lot about stuff like sedimented substrates, detritus, decomposition, turbid water, and it's important to remember that these things are common in many aquatic habitats around the world...things that we have typically not incorporated into aquariums before.

THAT to me is the next great challenge in the aquairum hobby: To create aquariums which are literal, functional interpretations of wild aquatic habitats. The neat thing is that, once we get a "handle" on keeping aquariums run with the botanical method, replete with decomposing leaves, fungal-covered branches, sediments, etc. successfully, the world literally opens up with possibilities.

Suddenly, that strange-looking flooded meadow with the epiphyte covered riparian plants and tons of Moenkhausia and other characins isn't so unachievable. It just takes a little study of the habitat, and some experience handling the "operation" of a botanical-method aquarium!

What kinds of unusual habitats or ecological niches would I like to see us play with? What about playing with more representations of unusual "niche" habitats, like vernal pools, flooded rice paddies, blackwater mangrove thickets, muddy streams, etc. I'll be doing my best to create more tangles of roots, detritus-filled tree stumps, sediment-encrusted branches, and all sorts of stuff that we see in various natural habitats.

The concept of creating aquariums to represent natural habitats in form is not a new thing in the hobby. However, what IS new is creating these aquariums to mimic the function of the habitats. To allow Nature to work Her magic on the "aquascaping materials" (ie; wood, roots, botanicals, plants, etc.) that we use, and to not try to "sanitize" everything along the way.

I personally am a little bored of seeing those "clinical" or "artistic" interpretations of "blackwater habitats" that are showing up on social media lately. There's more to it than simply "translating" a crystal-clear "Nature Aquarium"-style tank to one having some tinted water! The skill set most of those creators employ with those "Amano-esque" tanks would absolutely translate to this little niche. They just need to relax a bit on overly-stylizing things, that's all.

I think many are starting to see that it's entirely possible to have a more natural-functioning "Nature Aquairum Style" system, once which doesn't attempt to over-stylize and over-sanitize everything. It just takes a little time and experience with the botanical-method approach to get your head around it. I get it.

Re-thinking stuff like substrates, for example, is, in my opinion, another key to "unlocking" this new way of thinking. When we stop thinking about substrates as just "decoration", or even "A place to grow aquatic plants", we can approach things a bit differently. We need to examine wild aquatic habitats a bit more closely, and go beyond just thinking about how the "look" would translate into a cool aquascape.

Yeah, I think that we should look at substrates in our aquariums as more than just "the bottom" or "a place to put rocks and wood and plants"- but rather, as a dynamic, living, integral component of a balanced closed ecosystem. A place to culture supplemental food organisms, facilitate reproduction of fishes (I'm thinking soil-spawning killies here again), and impact the chemical composition of our water.

It would be great to apply as much emphasis to substrate in this vein as we do to other components of the aquarium. It's about more of those mental shifts; re-thinking the "how's" and "why's" of what we've done for so long.

A "substrate" can be- should be- way more than gravel or plain old sand.

And if we have our say in the matter, it will be!

And of course, if we dip back into Nature for some inspiration- as we should- there is an amazing amount of ideas to take away..

Consider so-called "vernal pools"- temporary (ephemeral) or seasonal aquatic habitats where killifish come from. They don't just have a certain "look" to them- they have a functional spect which affects the very life cycle of the organisms which reside there.

Vernal pools are generally found on plains or grasslands, and are typically small bodies of water- often just a few meters wide. The origin of the name, "vernal" refers to the Spring season. And, this makes a lot of sense, because most of these ephemeral habitats are at their maximum water depth during the Spring!

Vernal pools are typically found in areas comprised of various soil types that contain clays, sediments and silts. They can develop into what geologists call "hydric soils", which are defined as, “...a soil that formed under conditions of saturation, flooding, or ponding long enough during the growing season to develop anaerobic conditions in the upper part.”

That's interesting!

A unique part of the vernal pools is what is an essentially impermeable layer of substrate called "clay pan." These substrates are hugely important to the formation of these habitats, as the clay soils bind so closely together that they become impermeable to water. Thus, when it rains, the water percolates until it reaches the "claypan" and just sits there, filling up with decaying plant material, loose soils, and water.

So, yeah- the substrate is of critical importance to the aquatic life forms which reside in these pools! Let's talk killies for a second! One study of the much-loved African genus Nothobranchius indicated that the soils are "the primary drivers of habitat suitability" for these fish, and that the eggs can only survive the embryonic period and develop in specific soil types containing alkaline clay minerals, known as "smectites", which create the proper soil conditions for this in desiccated pool substrates.

The resulting "mud-rich" substrate in these pools has a low degree of permeability, which enables water to remain in a given vernal pool even after the surrounding water table may have receded! And, of course, a lot of decaying materials, like plant parts and leaf litter is present in the water, which would impact the pH and other characteristics of the aquatic habitat.

Interestingly, it is known by ecologists that the water may stay alkaline despite all of this stuff, because of the buffering capacity of the alkaline clay present in the sediments!

And, to literally "cap it off"- if this impermeable layer were not present, the vernal pools would desiccate too rapidly to permit the critical early phases of embryonic development of the Nothobranchius eggs to occur. Yes, these fishes are tied intimately to their environment.

(Image by Andrew Bogott, used under CC BY-S.A. 4.0)

Now, that is likely a deeper dive than you might have wanted to take on the vernal pool habitat, but it's just one example of what's "out there" in Nature, waiting for us to study and replicate in functional detail in our aquariums! The embrace of the function of natural habitats and the aquariums which represent them is, IMHO, the current 'bleeding edge" of freshwater aquarium practice.

And of course, it's not just the deeply-tinted waters of the world that were talking about. For example, our friend, Thomas Minesi, has spent years exploring the widely varied habitats of his native Democratic Republic of Congo, studying clearwater habitats, such as the River Fwa- which are ripe for replication in aquariums in function and form. He's discussed these habitats on "The Tint" podcast a few times- well worth another listen.

So I suppose the "literal" interpretations of natural aquatic ecosystems are so exciting to me because of the sheer variety which exists! You could literally spend a lifetime just trying to replicate a fraction of them. There is literally something for everyone out there!

We just have to look, and dive a little deeper.

Get out there! (Literally and metaphorically)

Stay curious. Stay thoughtful. Stay adventurous. Stay creative...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

The beauty of the "ignorance bubble..."

I've been in the aquairum hobby practically since I could walk. And as a "lifer", I am obsessed with virtually every aspect of the hobby. I am a voracious reader of hobby information, in print and online, and ion course, in person with fellow fish geeks when possible.

I love to research stuff.

That being said, I think that I also tend to take in "too much" information at times. In other words, overly researching and analyzing almost every aspect of an idea that I have.

And that can be a problem.

Yeah.

You WERE a beginner at one point. You didn't know anything about keeping tropical fish, except maybe that you were drawn to them somehow. And that is not neccasarilly a bad thing. Sometimes, NOT knowing-or being aware of everything- is a good thing.

Yeah, outright beginners might have it pretty good in the aquarium hobby.

Despite everything being new to them, they don't have the "burden of experience" holding them back.

We do.

And that can be a problem at times.

Perhaps the beginner knows something we don't? And that's to not sweat it so much. To educate yourself to the best of your ability...and then to just DO.

I often think that we- that is, more "advanced" hobbyists...know too much. We've "seen it all", know what to expect, and we let this guide- or perhaps, taint- our experiences... We often overthink, or over-analyze stuff.

Seriously.

And, just maybe...as a result of doing this incredible thing we do regularly...we know too much.

Yes.

We understand all of this stuff. Well, most of it, anyways. Enough to think about multiple angles and concerns...Enough to be hesitant when maybe- just maybe- we shouldn't be.

Sometimes, our experience holds us back from growing and learning more in the hobby.

Think about the advice we give to novices in the hobby. Much of it is simply based one having been through it ourselves many times. Yeah, we've experienced I algae blooms or whatever many times over the years, and have watched- and even reassured- others that "All of this is normal" and instruct them often to "...just be patient and it will pass..."

You know- "aquarium stuff."

Outright beginners actually have it much easier in this regard, I think.

I mean, when just having a glass or acrylic box of freshwater or saltwater in your home is a novelty- a cause for rejoicing! You tend to live in a bubble of gentle "ignorance" (eeehw- that's kind of harsh)- okay, let's call it "blissful lack of awareness about some things" that some of this stuff really sucks...

And that's actually a beautiful thing- because a beginner is taken by the sheer wonder- and joy of it all.

They don't stress out about stuff like algal films, detritus on the substrate, micro bubbles and the occasional falling piece of wood in their aquascape the way many "advanced" hobbyists do. And beginners in our little speciality? They're not worried about that "yucky biofilm" or water moment or any other of a dozen minutiae like we are, because they don't KNOW...or CARE- that it can linger a long, long time. They may our may not grasp that it's "part of the game."

And they likely don't care.

They're not "handcuffed" by their past experiences and the knowledge of having set up dozens of tanks over the years. Nor are they thinking that they have some kind of "luck." Rather, they're just stoked as hell by the thought of Glowlight Tetras, Amano Shrimp, Glass Catfish, and "ultra-common" Bettas taking up residence in the new little utopian microhabitat they just set up in their New York City apartment!

What could be more awesome?

I sometimes find myself in that same "ignorance bubble."

Happily, too.

Like, as most of you know, my knowledge of, and experience with aquatic plants is remarkably limited. I can barely identify more than a dozen species of plants, and I am not exactly well-versed on what they need to grow, outside of the basic stuff I learned in school.

Yet, there are times when I play with plants in my tanks. I have certain aquatic plants that appeal to me for various reasons, and from time to time, I'll incorporate them into one of my displays.

Yet, the fact of the matter is, I don't really know much about plants at all. I just research what I need to know about them and work with them. To the aquatic plant purists, no doubt my applications (or, mis-applications, as the case may be!) are horrifying, laughable or just mildly amusing, at best. I barely know what I'm doing with my aquatic plants, but I have a lot of fun with them when I do play with them...I exist in an aquatic plant "ignorance bubble."

I suppose the term, "ignorance" is a bit harsh...But it is a sort of a "blissful unawareness..." Like, I get it. I don't really know- or, for that matter, care- that I may not be utilizing the optimal lighting, fertilization regimen, or other best practices for my aquatic plants, to make them to grow like mad...

All I care about is that they are healthy, look nice, and enhancing the tank that they're in. That's good enough for me.

It's a pretty fun feeling, too.

Just embracing the sheer joy of being a beginner at something again. Enjoying what's happening in your aquarium NOW- rather than worrying about it; impatiently "tweaking" stuff to get "somewhere else."

Sounds like fun to me!

And look- if the bug bites, and you really want to just go "full ham" on a topic and become a specialist- you can. That's the beauty.

But you have to start. And that sometimes means taking a different mindset.

I think it's entirely possible to release ourselves from the "burden" of our own experience, and to allow ourselves to enjoy every aspect of this great hobby, free from preconception or prejudices. To just make decisions based on what our research- gut, or yeah- I suppose, experience- tells us is the "right" thing to do, then simply letting stuff happen.

In other words, taking control of the influence that our own experience provides, rather than allowing it to taint our whole journey with doubt, dogma, second-guessing, and over-analysis of every single aspect.

The key, or the "un lock", is to try something that's new to you. Move into unknown territory. Learn what you can, and then go for it. Don't be shy, or try to protect your ego. The simple fact is that, no matter where you are now in your hobby "career"- you had to start somewhere, right?

Yeah.

You WERE an absolute beginner in the aquarium hobby at one point.

We all have things we know, and things that we're clueless about.

And THAT is super exciting to me. Too step outside of what we know; to move into uncharted waters...to learn by doing.

Jump....

Stay curious. Stay resourceful. Stay bold. Stay...blissfully unaware of some stuff...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

On to the next?

Okay, I know it's a bit weird to say it, but as fish geeks, I think we're never completely satisfied with our aquariums. I mean, yeah, we love them, and we pour everything we've got into them (literally and figuratively!),

One of the things I've found it hardest to do as an aquarist who owns a company in recent years is to speed up the creation of new aquariums. The reality is that my whole aquarium "career" has been geared towards being able to s-l-o-w d-o-w-n and establish aquariums over long periods of time, allowing them to evolve.

This doesn't always square well with the "get more ideas out there YESTERDAY!" mindset that you seem to need to have in today's social media fueled hobby. I watch some YouTubers just crashing through every barrier in a frantic pace to get to the next project as quickly as possible. It's like, "Can't stand still for a second, or..!"

Or what, exactly?

Do "creators" really think that they're going to lose a substantial percentage of their followers just because it's Wednesday, they're still stabilizing their African river tank, and they didn't get to the 240-gallon Pirahna tank just yet?

Really?

I mean, it's kind of crazy. However, I DO understand the mindset behind it to a certain extent.

Yeah. Like, when you see part of your responsibility being to inspire others through your ideas and work, you want to show as much as possible, as frequently as possible. But, does that mean constantly creating some new setup to follow whatever the hot thing is at the moment? It gets ridiculous after a while ("If it's Thursday, it's time for the Rainbowfish biotope tank...Or was it the macro algae tank? Or maybe it's the Swordtail tank...")

Again, I suppose part of me understands.

"Creators" feel that they need to...create. But why does it always have to be a new tank? Why not produce content focusing on evolving and perfecting the existing tanks? Why not discuss the current challenges, status, and progress on the tank you just started? Some creators do this, and it's great content! Now, I understand, some professionals can show new tanks every week because that's what they do!

But hobbyists shouldn't feel that there is some "pressure" to constantly feature new stuff. Because there isn't. But the pressure is there, sure.

I could have easily succumbed to this perceived urgent "need" to crank out a rapid succession of tanks. After all, it's been almost 18 months since I was able to have a meaningful home aquarium, I've got a ton of ideas, my wife is all for it, and I feel good about all of the projects I've got planned...Full speed ahead, right?

Where's the fun in THAT?

Yeah, I've purposely kept myself on a "hobbyist footing", and am trying to simply play with each tank and work on the challenges that arise with them in a manageable, logical pace. I want to fully ENJOY each one for what it is. And I've been sharing what's been going on with them. Maybe it's not as exciting as me setting up two more cool new tanks, but it feels much more "honest" to me.

I've made the effort to document and discuss the progress with my brackish water mangrove tank. I've spent a lot of time sharing images and social media posts on the progress of the mangroves. As I mentioned a bunch of times, mangroves do not like being transplanted, and they shock out and take some time to recover. It was real touch and go there for a while; I thought I might lose all of my two and a half year old seedlings.

Fortunately, I've taken my time to let them come around and revive, and had some great discussions with fellow mangrove geeks about them. It's been really gratifying to see them come back, and it's been fun to share the progress. And to talk about the fact that my aggressive handling of the transplant almost killed them. To share the good, the bad, and the downright ugly with fellow hobbyists is the name of the game here.

But this piece isn't just about creating content for social media or whatever. It's about the mindset that you should cultivate to slow down and enjoy every aspect of what you're doing. I'm all about "deferred gratification"- or more realistically- gratification from every stage of the aquarium journey.

I think it's just more fun to "work through" a tank evolution. Yeah, I've had times when I've killed a project really quickly; changed my mind on something and just ended it. However, that's almost never happened when I've been working with a project that I put a lot of thought into.

Case in point is the simple, small botanical-method tank that I started a couple of months back. I had in my mind the desire to create a tank for some Asian blackwater fishes, utilizing the approach of "leaf litter"only", and then gradually evolving the tank into something a bit more diverse. A lot of people asked me to do another tank like this, to sort of show how a leaf litter only system can be set up and managed.

I've done this type of tank a few times before, so it wasn't exactly breaking new ground for me, but it was fun to document the process. I felt- and still feel- that the leaf-litter-only approach is one of the easiest, if not THE easiest, botanical-method aquariums to run. And of course, I wanted to work on that longer-term theme of heavy leaf litter, twigs, and easy epiphytic plants in the display, so the process was sped up considerably to begin evolving it towards that. The "leaf litter only" phase was just a sort of "waypoint" in a journey.

A journey...Because that's what each aquarium we create really is, right?

Yet, I can't help but wonder why it is that, in the aquarium world we seem to feel the need to get to something that we can call "finished"- and quickly, at that.

I wonder if it has to do with some inherent impatience that we have as aquarists- or perhaps as humans in general-a desire to see the "finished product" as soon as possible; a sort of "goal oriented" mindset- something like that. And there is nothing at all wrong with that, I suppose. I just kind of wonder what the big rush is?

I guess, when we view an aquarium in the same context as a dental procedure, tax return preparation, or folding laundry, I can see how rush would take on a greater significance!

On the other hand, if you look at an aquarium as you would a garden- an organic, living, evolving, growing entity- and something enjoyable-then the need to see the thing "finished" becomes much less important. Suddenly, much like a "road trip", the destination becomes less important than the journey. It's about the experiences gleaned along the way. Enjoyment of the developments, the process. In the botanical-style aquarium, it's truly about a dynamic and ever-changing system. Every stage holds fascination.

IS there even a "finish line" to an aquarium?

Does it ever reach "finished?" Does Nature? Of course not! Rather, it's continuous evolution, in which there might be some competition between fishes, plants, or corals ( in a reef tank, of course) that results in one or more species dominating all of the rest. Maybe. Or, perhaps diversity continues to win, with lots of different life forms eaking out an existence in your artificial microcosm, just as they have managed to do for eons in Nature?

We don't have all of the answers.

And that's okay. That's part of the fun, too.

And we also should enjoy those times when our tanks are doing their thing...evolving...

Which is... every single day.

Yet, there is an apparent disconnect in the general aquarium hobby. A desire to get to "finished"- whatever that actually IS- as quickly and easily as possible. Like, why are we in such a damn rush? What's the point of trying to quickly get through all of the amazing stages of aquarium development, en route to some strange and seemingly enigmatic destination called "finished?"

I personally think that our social-media-fueled hobby era has continued to push this narrative, to the detriment of the hobby. ("There he goes again, hating on social media!" ) I'm NOT hating social media- it's one of the greatest facilitators of human communication in history. However, I am criticizing the behavior of humans who use it. We want to show only the best side of everything; we seem to want to create an aura of excitement, energy, and momentum, I guess.

Just glossing over the daily progress in order to show the "finished product", overlooks the evolution, the experiences, and the little bits of knowledge gleaned along the way. Enjoyment of the developments, the process.

Botanical method aquariums pretty much demand that you slow down. Since the very nature of utilizing materials such as leaves and botanicals will result in them gradually decomposing in water, and not only changing in appearance, but influencing the water chemistry and physical environment of the aquarium to a varying degree, we as lovers of botanical-style aquariums view every aquarium as an evolving entity.

And, as an evolving entity, a botanical aquarium requires some understanding and patience, and the passage of time...

You can't rush this process and expect good results.

t's why we literally pound it into your head over and over here that you not only shouldn't try to circumvent these processes and occurrences- you should embrace them and attempt to understand exactly what they mean for the fishes that we keep.

They're a key part of the functionality.

I've always been fanatical about NOT taking shortcuts in the hobby. In fact, I've probably avoided shortcuts- to the point of making things more difficult for myself at times! Over the years, I have thought a lot about how we as botanical-method aquarium enthusiasts gradually build up our systems, and how the entire approach is about creating a biome-Just like what Nature does.

It works exactly the same in an aquarium...If we let Nature do her work without excessive intervention.

Just be patient. Really patient.

The lack of patience in the hobby is often reflected in social media posts, especially many of the so-called "tank build threads."

I see these in reef-keeping forums constantly, and sadly, they often follow a very predictable path. They start out innocently and exciting enough- the tank concept is highlighted, the acquisition of (usually expensive) equipment is documented, and the build begins. The pace quickens. The urgency to “get the livestock in the tank asap” is palpable. Soon, pretty large chunks of change are dropped on some of the most trendy, expensive coral frags- or worse yet- colonies- available.

Everyone “oohs and ahhs” over the additions. Those who understand the processes involved- and really think about it- begin to realize that this is going too fast…that the process is being rushed…that shortcuts and “hacks” are cherished more than the natural processes required for success.

Sure enough, within a month or so, frantic social media and forum posts are written by the builder, asking for help to figure out why his/her expensive corals are “struggling”, despite the amount spent on high-tech equipment, additives, and said corals from reputable vendors.

When suggestions are offered by members of the community, usually they’re about correcting some aspect of the nitrogen cycle or other critical biological function that was bypassed or downplayed by the aquarist. Usually, the “fixes” involve “doubling back” and spending more time to “re-boot” and do things more slowly. To let the system sort of evolve (oh- THAT word!)

And, then, the “yeah, I know, but..” type of responses- the ones that deflect responsibility- start piling up from the hobbyist. Often, the tank owner will apply some misplaced blame to the equipment manufacturer, the livestock vendor, the LFS employee…almost anyone but himself/herself. And soon after, the next post is in the forum’s “For Sale” section, selling off components of a once-ambitious aquarium.

Another hobbyist lost to lack of patience.

We have to overcome this phobia that we have collectively developed which says, "I can only share my best work!" or, "I need to get it to some point where I'm comfortable showing it off.."

Why?

Because people might see that your tank had to start somewhere? Because you might have some algae in there? Because you haven't yet arrived at the final wood configuration? Don't have all of the leaf litter in place?

For every excuse, I can think of several reasons why you should share.

Everything.