- Continue Shopping

- Your Cart is Empty

The color of water...

One of the most common misconceptions about botanical-method aquariums is that they must absolutely be filled with deeply tinted water and replete with fungal-and-biofilm-encrusted decomposing leaves, twigs and seed pods.

Remember, this is a methodology, not a "style of aquascaping", and the reality is that you can have an aquarium which fully embraces the ecological aspects of natural aquatic systems and have clear, slightly tinted, or even turbid water. It's not a "prerequisite" to have that dark brown water. Quite honestly, we see the tinted water as a "collateral" aesthetic benefit of embracing this approach- not the main reason to do it.

The hobby has somehow latched on to the most superficial aspect of blackwater- the look- and in the social media landscape, the appearance of blackwater has led to a tremendous confusion about what it actually is.

As we've mentioned hundreds of times here, the aquairum definition of "blackwater" seems to apply to any tank which has less than crystal-clear, blue-white water. Remember, in Nature, the term "blackwater" applies to water with a very specific set of chemical characteristics; the color of the water is a result of the presence of various compounds in the water. The visuals may play a huge role in our "interpretation" of what we think "blackwater" is- but the reality is that it's much more of a "chemical soup" which makes it so.

Although the three "classical water types" (white, black and clear) are used by science to describe many of these habitats, aquarists tend to classify water as "blackwater" or "clearwater", which, although not scientifically "pure", tends to make our understanding and discussions easier!

And the reality is that there are many, many habitats throughout the world which have tons (literally) of botanical materials in them, yet have relatively clear water. It's certainly not a given that the presence of leaves, wood, and other botanical materials in a given body of water will result in brown water and low pH. Rivers like the Juruá, Japurá, Purus, and Madeira) are turbid, with water transparency that varies, and they transport large amounts of nutrient-rich sediments from The Andes. Their waters have near- neutral pH and relatively high concentrations of dissolved solids.

The Rio Xingu and Tapajós are classic examples of "clearwater" rivers. One of the largest tributaries of the Amazon, the "Xingu" has an abundance of rock, and a higher content of dissolved minerals than a blackwater habitat like the Rio Negro. There is not much suspended matter because the rock formations which the river courses through are ancient and no longer erode in the current. The pH varies between 6 and 7.

And, for almost as long as hobbyists have been playing around with "blackwater aquairums", there has been confusion, fear, misunderstanding, and downright misinformation on almost every aspect of them! We’re still seeing a lot of that confusion. It’s important to really understand the most simple of questions- like, what exactly is “blackwater”, anyways?

A scientist will tell you that blackwater is created by draining from older rocks and soils (in Amazonia, look up the “Guyana Shield”), which result in dissolved fulvic and humic substances, present small amounts of suspended sediment, and characterized by lower pH (4.0 to 6.0) and dissolved elements, yet higher SiO2contents. Tannins are imparted into the water by leaves and other botanical materials which accumulate in these habitats.

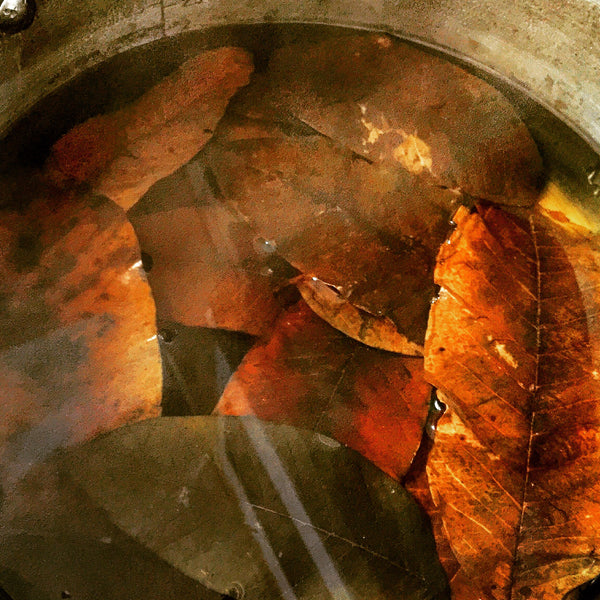

The action of water upon fallen leaves and other botanical-derived materials leaches various compounds out of them, creating “black-water.” Indeed, this leaching process is analogous to boiling leaves for tea. The leached compounds are both organic and inorganic, and include things like tannin, carbohydrates, organic acids, pectic compounds, minerals, growth hormones, alkaloids, and phenolic compounds.

In summary, natural black waters typically arise from highly leached tropical environments where most of the soluble elements are rapidly removed by heavy rainfall. Materials such as soils are the primary influence on the composition of blackwater. Leaves and other materials contribute to the process in Nature, but are NOT the primary “drivers” of its creation and composition.

So, right from the start, it’s evident that natural blackwater is “all about the soils…” Yeah, it’s more a product of geology than just about anything else.

More confusing, recent studies have found that most of the acidity in black waters can be attributed to dissolved organic substances, and not to dissolved carbonic acid. In other words, organic acids from compounds found in soil and decomposing plant material, as opposed to inorganic sources. Blackwaters are almost always characterized by high percentages of organic acids.

Interestingly, however, these waters are surprisingly low in dissolved organic compounds (DOC). In fact, Rio Negro black waters are theorized to have low DOC concentrations because of the diluting effect of significant amounts of rainfall, and because they are diluted by clear waters from nearby systems low in dissolved organic compounds.

Sort of self-regulating, to an extent, right?

In the podzolic soil where blackwater originates, most of the of the extractable substances in the surface litter layer are humic acids, typically coming from decaying plant material. Scientists have concluded that greater input of plant litter leads to greater input of humic substances into ground water.

In other words, those leaves that accumulate on the substrate are putting out significant amounts of humic acids, as we've talked about previously! And although humic substances, like fulvic acid, are found in both blackwater and clear water habitats, the organic detritus (you know, from leaves and such) in blackwater contains more extractable fulvic acid than in clearwater habitats, as one might suspect!

The Rio Negro, for example, contains mostly humic acids, indicating that suspended sediment selectively adsorbs humic acids from black water. The low concentration of suspended sediments in rivers like the Rio Negro is one of the main reasons why high concentrations of humic acids are maintained. With little to no suspended sediment, there is no "adsorbent surface" (other than the substrate of the river, upon which these acids can be taken hold of (adsorb).

When you think about it, all of this this kind of contributes to why blackwater has the color that it does, too. Blackwater in the Amazon basin is colored reddish-brown. Why? Well, it has those organic compounds dissolved in it, of course. And most light absorbtion is in the blue region of the spectrum, and the water is almost transparent to red light, which explains the red coloration of the water!

As we've mentioned many times, water color, although helpful to us aquarists in some respects, is not an absolutely reliable indicator of the pH or ionic composition of the water! There is no substitute for good, old-fashioned water testing!

Remember, just because the water in a botanical-influenced aquarium system is brownish, or has a bit of noticeable "turbidity", it doesn't mean that it's of low quality, or "dirty", as we're inclined to say. I can't stress it often enough. It simply means that tannins, humic acids, and other substances are leaching into the water, creating a characteristic color that some of us geeks find rather attractive. If you're still concerned, monitor the water quality...perform a nitrate test; look at the health of your animals.

Interestingly (and perhaps, confusingly) the lower section of some Amazonian black-water rivers such as the Rio Negro, Tefé, Uatumã and Urubu in Brazil; Nanay in Peru and some streams in Colombia can have ionic composition and/or pH-values similar to the white water rivers, and not like the typical Amazonian blackwater rivers. It is though by researchers that low electrical conductivity values can be responsible for this phenomenon.

In addition, it's though that many rivers and streams have to be considered as “mixed waters” resulting from the influence of tributaries with different physical and chemical properties of their waters.

As if we don't need more confusion, right? Talk about "muddy waters!"

So, for us aquarists, the arguments and discussions can rage on and on and on, and aquarists who have been to various parts of these rivers may observe somewhat different characteristics than others...and be 100% accurate in their findings! Generalizations, although often a "no- no", may actually be useful to us. (gulp)

One of the big discussion points we have in our world is about the color and "clarity" of the water in our blackwater aquariums. We receive a significant amount of correspondence from customers who are curious how much "stuff" it takes to color up their water.

Those of us in the community of blackwater, botanical-method aquarists seek out tint and "body" in our water...while the rest of the aquatic world- well, they just sort of... freak the fuck out about that, huh?

Our aesthetic "upbringing" in the hobby seems to push us towards "crystal clear water", regardless of whether or not it's "tinted" or not. And think about it: You can have absolutely horrifically toxic levels of ammonia, dissolved heavy metals, etc. in water that is "invisible", and have perfectly beautiful parameters in water that is heavily tinted and even a bit turbid.

(FYI, WIkipedia defines "turbidity" in part as, "...the cloudiness or haziness of a fluid caused by large numbers of individual particles that are generally invisible to the naked eye, similar to smoke in air.")

That's why the aquarium "mythology" which suggested that blackwater aquairums, or aquariums with tinted water were somehow "dirtier" than "blue water" tanks used to drive me crazy. The term "blackwater" describes a number of things; however, it's not a measure of the "cleanliness" of the water in an aquarium, is it?

Nope.

Color alone is not indicative of water quality for aquarium purposes, nor is "turbidity." Sure, by municipal drinking water standards, color and clarity are important, and can indicate a number of potential issues...But we're not talking about drinking water here, are we?

No, we aren't!

(And yes, aquariums with high quantities of organic materials breaking down in the water column add to the biological load of the tank, requiring diligent management. This is not shocking news. Frankly, I find it rather amusing when someone tells me that what we do as a community is "reckless", and that our tanks look "dirty."

As if we don't see that or understand why our tanks look the way they do.)

There is a difference between "color" and "clarity."

The color is, as you know, a product of tannins leaching into the water from wood, soils, and botanicals, and typically is not "cloudy." It' actually one of the most natural-looking water conditions around, as water influenced by soils, woods, leaves, etc. is ubiquitous around the world. Other than having that undeniable color,there is little that differentiates this water from so-called "crystal clear" water to the naked eye.

Of course, the water may have a lower pH and general hardness, but these factors have no bearing on the color or visual clarity of the water. And conversely, dark brown water isn't always soft and acidic. You can have very hard, alkaline water that, based on our hobby biases, looks like it should be soft and acid. Color is NO indicator of pH or hardness! Again, it's one of those things where we ascribe some sort of characteristics to the water based solely on its appearance.

As I've mentioned before, a funny by-product of our more recent obsession with blackwater aquariums in the hobby is a concern about the "tint" of the water, and yeah, perhaps even the "flavor" of said water! A by-product of our acceptance of natural influences on the water, and a desire to see a more realistic representation of certain aquatic environments.

And that means that dark water we love so much.

Yeah, we now see posts and discussions by hobbyists lamenting the fact that their aquarium water is not "tinted" enough. A lot of hobbyists have "bought in" to those mental shifts we keep talking about...

You sort of have to smile a bit, right?

Total mental shift, huh?

We impart color-producing tannins into the water in our aquariums by utilizing leaves and other botanical materials, like seed pods, cones, bark, and even wood. Confusingly, you can achieve the look of blackwater habitats even with relatively hard, alkaline water. Of course, there is more than just the aesthetics, right? Many of these materials will also impart complex compounds, like polyphenols, polysaccharides, lignin, and other substances into the water as well, which can have positive influences on fish health, and the overall aquarium environment.

So, the approach to create “aquarium quality” blackwater is surprisingly simple, really. Start with high quality RO/DO water, add some botanical materials like leaves, bark or seed pods, and in theory, you’ve created the aquarium equivalent of “blackwater.” I mean, it’s not quite that simple, as the easy process belies the complex chemical interactions that take place in the water to create these conditions, but for most of us, that’s kind of how it works on a superficial level.

it IS important for us to not delude ourselves into thinking that just tossing some leaves into an aquarium and admiring the tinted color gives us a "blackwater aquarium," like you see in a lot of the so-called "influencer" videos on social media that pop up regularly now. Just sort of "mailing it in" by touching on the most superficial aspects of the concept.

If we throw around ideas like, "The tank in this video represents a blackwater river in Amazonia" or some other such grandiose pronouncement, we owe it to our audience to either try to explain what this means, what the characteristics of a natural blackwater habitat are, or why our tank, filled with lots aquatic plants, gravel, a few leaves, and water of unspecified chemical characteristics isn't "blackwater." It perhaps, superficially, mimics some aspects of the blackwater environment. It's "inspired by..."

But that's it.

And that's okay, but we have a responsibility to our fellow hobbyists to explain this.

To NOT be more accurate in our description about what we do in this sector-to just "cliche" it and label any tank with tinted water a "blackwater aquarium" runs the risk of simply "dumbing down" what we do, and working against the efforts and progress made by so many hobbyists to create a proper, replicable, and consistent methodology to creating botanical-style aquariums. And it displays a fundamental ignorance of the work of many researchers and scientists, who help classify and study these habitats.

Botanical-method aquariums. Tanks which incorporate botanical materials to influence some aspects of the water chemistry and biology. That's what we play with. Many times, the result is an aquarium with water that has a brownish tint, perhaps a slightly reduced pH, and an array of decomposing leaves and seed pods.

It's a methodology to create more natural functioning aquariums. It just happens to result in aquariums which look different- perhaps, superficially like blackwater habitats.

And of course, it's perfectly okay and easy to have an aquarium filled with all of these tannin-producing materials and to render the water crystal clear with activated carbon or other chemical filtration media!

And understanding the interactions of these materials with water and the overall aquatic environment in our tanks AND in Nature, have enormous implications for the future of our hobby.

Water is a sort of "blank canvas"- a starting point...a "media" for our work. So many possibilities...That's the allure of water!

The beauty of an aquarium is that you can either remove or contribute to the color and clarity characteristics of your water if you don't like 'em, by simply utilizing technique- ie; mechanical and chemical filtration, water changes, etc.

The color of water. It's that simple.

Stay engaged. Stay curious. Stay observant. Stay thoughtful...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Changes...

One of the cool things about our hobby is that we can switch stuff up.

For months, I've been kicking around ideas for my next new aquarium. Well, for a new concept within one of the existing aquariums I have. It gets stronger every day. And it's a normal sort of thing...At least, I tell myself that it is!

I mean, we all do this...like, constantly, right? Edit. Ideate. Iterate.

Yeah.

It's not a bad idea to evolve existing tanks.

Sometimes, it's a little "adjustment" to an existing system.

Incremental changes or aesthetic tweaks that get you into a different "groove."

Other times, you get the call in your mind to just "erase" and start fresh. Sometimes, it's for specific reasons: the current setup isn't working well for you or your fishes. It's tough to maintain, or difficult to keep up with.

Or maybe, just maybe- you're a bit "over" it.

You know, ready for something totally new.

Those of us who are limited in the number of aquariums that they have (or want to have, as in my case!) are often faced with a dilemma of sorts: We want to try different things, and the only way to do it... is to break apart one of the current aquariums that we have going, and to re-do it.

That kind of sucks...but in a way, this sort of compromise is part of being a hobbyist, right?

Tinkering. Tweaking. "Playing" with stuff.

You can call it something fancy, like "iterating"- but in the end, it's really about tearing up your current aquarium and re-doing it in some different way.

And that's just part of the game, right?

Not everyone can have 30, 12, or even 4 aquariums in their home, shitty though that might be! Yet, many of us have big ideas, unique plans, and strong aspirations...lots of 'em- and the only way to execute is to do these "makeovers" on a regular basis...

Or at least, when the "muse" hits!

I don't know about you, but it's always been a bit of a "guilt-inducer" for me to do that. I mean, you've got this aquarium that is (hopefully) all that you expected it would be. Looks great, functions awesomely, and has been perfectly manageable. And then, in the middle of this wonderful endeavor, you have the urge- or perhaps the inspiration- to try something totally different.

And you break out the metaphorical "eraser" and just wipe the slate clean; start fresh.

Wow.

It was never easy for me to do this.

I mean, I'm the guy that would keep tanks set up for years with only minor aesthetic/fish population tweaks along the way. Patient. Stable. Consistent.

I was always kind of proud of that.

I used to think that it was kind of weird how those competitive aquascaper people who you see on Instagram and YouTube could just tear down an amazing tank and start all over after just a few months, seemingly without a care in the world.

How could they just do that?

And then, the ideas came.

As the owner of what people tell me has become a sort of niche-centric, progressive, creativity-enabling/inspiring company, I realized that I needed to show some different "looks" that I myself, or my colleagues have done- on a semi-regular basis...to sort of "keep it real" for me and to inspire our customers. Perhaps it can be seen as an excuse of sorts, but there is some legit rationale behind it!

I mean, I receive lots and lots of pics from talented hobbyists worldwide each week, showing their amazing botanical-method aquarium work- but it is also important to show my own stuff. It keeps me in touch with the "craft"; the reality of what we do. And let's face it- it's more authentic when you're a "doer"- not just a "talker."

Yup.

And still, for a long time- I'd wonder just how these competition 'scapers could pull this off (at least mentally)- re-doing tanks so frequently. I mean, they have the talent...It's the mindset that eludes me.

What is it?

And then I began to understand: It's about this need to "continue."

An urge to create, expand horizons...

And when you're space-limited (or, "tank-limited") the only way forward is to break down the current tank and start working your new idea.

I've finally gotten myself to that place after decades...

It becomes more of a process...Or maybe, a progression of sorts.

And after psyching myself up...the day comes, and I dive right in.

Out go the fishes, re-housed to a different tank (if keeping different fishes is part of the plan, that is), and the "remodeling" process happens.

And, for about the first hour, I usually feel guilty that I broke apart something cool. Something really nice. Special, even. I worry about the well-being of the animals, fist and foremost...but only for a little bit, because I know that wherever I house them, it will be in optimum conditions for them...('cause that's how I roll!)

So, then the guilt gives way to a tinge of nostalgia...Remembering how nice it was to take the tank from idea on a piece of paper to full-fledged miniature ecosystem. I recall the challenges, obstacles, and triumphs...

Deep breaths.

Within two hours, I'm back to being excited again, staring at a now empty tank- you know, the proverbial "blank canvas" that we all drool over. Aquarists love this sort of stuff! We LIVE for it! At that point, it's all about the possibilities. The chance to do something really special "this time."

Can you relate to this process? This mindset? I suppose if you have 45 tanks in your basement, this manifests itself differently, but to those of us with a handful- or less- the process takes on a far more "sacred", almost ritualistic meaning.

Yet, we do it.

We plunge forward. And we realize that the best part of being an aquarium hobbyist...is being an aquarium hobbyist. Regardless of what we're doing at any given moment.

I mean, if you're satisfied with the tank you've got the way it is- mazeltov! Good for you. If you're not...or if you just feel the urge to do something different...Do it.

Don't feel guilty like I do sometimes. Feel excited. Motivated. Stoked.

Know that you're at another fork in the road on your aquatic journey. And it's totally okay to go in whatever direction you want.

And that's pretty damn cool, if you ask me.

I hope that the story of my little epiphany about this subject has struck a chord within you.

Keep moving forward...push the outside of the envelope. Run down that dream. Scratch the itch.

Stay forward-thinking. Stay creative. Stay relentless. Stay engaged...

Function, form, and the call of "microhabitats" and niches...

One of the most nitrating things about our era of aquarium keeping is that we have access to an enormous amount of information about the wild habitats of our fishes. If you make the effort, you can find scientific research papers on just about any fish, locale, and habitat you can think of. With all of this information available, the sheer number of habitats which you can replicate in an aquarium is mind boggling!

And it's not just habitats, per se- it's little ecological niches within the habitats- known to ecologists as "microhabitats" -defined as habitats which are small or limited in their extent, and which differ in character from some surrounding more extensive habitat.

These can be both compelling and rewarding to use as an aquarium subject! And, not surprisingly, these may encompass simple materials which we as botanical-method aquarium enthusiasts are quite familiar with! In many natural aquatic habitats, fallen tree branches, twigs, and leaves, form a valuable and important part of the ecosystem.

The complexity and additional "microhabitats" they create are very useful for protecting baby fishes, breeding Apistogramma, maintaining Poecilocharax, catfishes, Dicosssus, and other small, shy fishes which are common in these locales. They provide foraging areas, as well as locations to sequester detritus, sediments, and nutrients for the benefit of the surrounding ecosystems.

It would be remarkably easy- and interesting- to replicate these habitats within the confines of the aquarium. The mind-blowing diversity of Nature is comprised of millions of these little "scenes", all of which are the result of various factors coming together.

As aquarists, observing, studying, and understanding the specifics of microhabitats is a fascinating and compelling part of the hobby, because it can give us inspiration to replicate the form and more important- the function- of them in our tanks!

We spend a lot of time discussing and considering the various components and interactions of water and terrestrial habitats, and I think that if WE haven't made a compelling case, our Nature will!

Consider the "karsts..."

A karst is an area of land made up of limestone. Limestone, also known as chalk or calcium carbonate, is a soft rock that dissolves in water. This process produces geological features like ridges, towers, fissures, sinkholes and other characteristic landforms. Many of the world’s largest caves and underground rivers are located in karstlands.

(Karstic terrain. Image by Jan Nyssen used under CC BY-SA 4.0)

The porous limestone rock holds a lot of groundwater, ponds, and streams, sometimes located underground. And those cool structures known as cenotes (closed basins)! Yeah, we'll revisit those some other time.

Karsts are characterised by the presence of caves, sink holes, dry valleys and "disappearing" streams. These landscapes are known for their groundwater flow and efficient drainage of surface water through a wide network of subterranean conduits, fractures and caves.

Karst are found throughout the world, including France, China, the Yucatán Peninsula; South America, and parts of the United States.

In typical karstic habitats, the water is very clear, becoming turbid after heavy rains. Flash floods occur several times during the rainy season. In this period the stream width increases, making available habitats to be colonized, called "temporary stretches".

Are you thinking what I'm thinking? Yeah, these could be interesting aquarium subjects!

Yeah. And since a bunch of 'em occur in South America, where some of our fave fishes come from...this could be really interesting!

A fascinating neotropical karst landscape is located in the São Francisco River basin, Minas Gerais State, in Brazil. The fish diversity in these waters is significant. One study that I stumbled upon identified 28 species distributed in 3 orders and 9 families in this one locale alone!

The pH values in the South American karst habitats I found studies on range from 6.3 to 8.2, and averaged around 7.2 (slightly alkaline). Water temperatures average around 75 degrees F ( 23.8C), conductivity averages .30mS/cm, and the ORP averages 178 mv. (lower than one might expect, right? In reef keeping, we shoot for around 300 mv, so...) It's thought that the low levels of ORP can be associated with environmental pollution and/or high concentrations of ions, which is consistent in waters with karstic origins.

From an aquarist's perspective, karstic habitats should be pretty easy to replicate in the aquarium, right? Lots of smooth stone and sand, with a scattering of leaves and a few branches. This is one instance where I'd tell you to use plenty of activated carbon or other chemical media, to keep the water more or less clear. I mean, in some locales, as we mentioned previously, it's crystal clear!

Lots of epiphytic algal growth, some broken up leaves, aggregations of rocks...sand...I mean, this is like aquarist paradise! You can pretty much use every trick in the book and still come up with a reasonably faithful biopic representation- functionally aesthetic, no less! And, for some of you, not to have to deal with super acidic water and dark tint could be a real win, huh?

This is the most cursory description of karsts- but I hope it whets your appetite to learn more about them! Dig deeper, and you'll find a remarkable amount of information about them.

And of course, I can't just discuss one interesting habitat without mentioning another, right?

Among the richest habitats for fishes in streams and rivers are so-called "drop-offs", in which the bottom contour takes a significant plunge and increase in depth. These are often caused by current over time, or even the accumulation of rocks and fallen trees, which "dam up" the stream a bit. (extra- you see this in Rift Lakes in Africa, too...right? Yeah.)

Fishes are often found in drop offs in significant numbers, because these spots afford depth (which thwarts the hunting efforts those pesky birds), typically slower water movement, numerous "nooks and crannies" in which to forage, hide, or spawn, and a more restive "dining area" for fishes without strong currents. They are typically found near the base of tree roots...From an aquascaping perspective, replicating this aspect of the underwater habitat gives you a lot of cool opportunities.

And of course, these types of habitats are perfect subjects for aquarium representation, aren't they?

If you're saddled with one of those seemingly ridiculously deep tanks, a drop-off could be a perfect subject to replicate. And there are even commercially-made "drop-off" tanks now! Consider how a drop-off style encompasses a couple of different possible niches in the aquarium as it does in Nature!

Overhanging trees and other forms of vegetation are common in jungle/forest areas, as we've discussed many times. Fishes will tend to congregate under these plants for the dimmer lighting, "thermal protection", and food (insects and fruits/seeds) that fall off the trees and shrubs into the water. (allochthonous input- we've talked about that before a few times here!) And of course, if you're talking about a "leaf litter" or botanically-influenced aquascape, a rather dimly-lit, shallow tank could work out well.

And of course, in the areas prone to seasonal inundation, you'll often see trees and shrubs partially submerged, or with their branch or root structures projecting into the water. Imagine replicating THIS look in an aquarium. Contemplate the behavioral aspects in your fishes that such a feature will foster!

Lots of leaves, small pieces of wood, and seed pods on the substrtae- doing what they do- breaking down-would complete a cool look. For a cool overall scene, you could introduce some riparian plants to simulate the bank as well. A rich habitat with a LOT of opportunities for the creative 'scaper!

Why not create an analogous stream/river feature that is known as an "undercut?" Pretty much the perfecthiding spot for fishes in a stream or river, and undercuts occur where the currents have cut a little cave-like hole in the rock or substrate material near the shore.

Not only does this feature provide protection from birds and other above-water predators, it gives fishes "express access" to deeper water for feeding and escaping in-water predators!

Trees growing nearby add to the attractiveness of an undercut for a fish (for reasons we just talked about), so subdued lighting would be cool here. You can build up a significant undercut with lots of substrate, rocks, and some wood. Sure, you'd have some reduced water capacity, but the effect could be really cool.

Yeah, I could go on and on with all sorts of ideas about how to recreate all sorts of microhabitats in the aquarium- because there are a seemingly limitless number of them to explore and replicate!

There is a reason why all of these unique environments are successful, and why life exists- and indeed- thrives- in them. And there are reasons why we're starting to see incredible results when replicating some of the functional aspects of these environments in a more faithful manner than may have been attempted before.

And we have all of the "tools" that we need to do this:

Patience. A long-term view. Information. Observation. Understanding.

You've got this.

Stay creative. Stay enthusiastic. Stay observant. Stay patient. Stay excited...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Random, or not?

I'm a big fan of some of the aquatic features that you see in Nature. The seemingly random, unusual, and almost "disorderly" appearance of many aquatic features is really inspiring. I mean, Nature takes all of these random elements, and combines them in amazing ways.

And when you consider that virtually all freshwater fishes come into contact with some botanical materials throughout their existence, it opens your mind to the possibilities. In virtually every body of water, you'll find some sunken branches, tree trunks, leaves, roots, seed pods, etc.- stuff which can create really interesting features to support all sorts of fishes.

And this doesn't require us to do tremendous amount of "aquascaping" in the traditional hobby sense. Rather, it's more about seeing how Nature does it...

Huh?

Think about this: We as hobbyists spend an enormous amount of energy and effort creating meticulous wood arrangements and rockwork in our aquariums, trying to achieve some sort of perfectly-radioed, artistic layout.

Personally, I'd like to see us apply the same level of dedication to really understanding and replicating the "function" of Nature in relation to its appearance, and embracing the random nature of its structure in our tanks.

When you look at those amazing pictures of the natural aquatic habitats we love so much, you're literally bombarded with the "imperfection" and randomness that is nature. Yet, in all of the "clutter" of an igarape flooded forest, for example, there is a quiet "elegance" to it.

There is a sense that everything is there for a reason- and not simply because it looks good. It IS perfect. Can't we bring this sense to our aquariums? I think we can...simply by meeting nature halfway.

Is there not also beauty in "randomness", despite our near-obsessive pursuit of rules, such as "golden ratio", color aggregating, etc? Just because last year's big 'scaping contest winner had the "perfect" orientation, ratios, and alignment of the (insert this year's trendiest wood here) branch within the tank, doesn't mean it's a real representation of Nature, let alone, the natural functionality of "randomness."

In other words, just because it looks good, it doesn't mean it's what Nature looks like. That's perfectly okay, of course, except when you're blabbing on and on about how your tank is a "beautiful recreation of Nature", as hobbyists tend to do online!

I think it's perfectly okay for hobbyists to simply say that they have created a beautiful, artistic, nature-inspired arrangement in their tanks! A beautiful tank is a beautiful tank- regardless of how you label it. It's that misappropriation of the term "Nature" or "Natural" that drives me crazy.

There's a disconnect, of sorts- and I think it starts with our collective failure as hobbyists to take into account how materials like branches, leaves, twigs, and seed pods arrive in their positions within an aquatic habitat. These factors have a huge influence on the way these habitats form and function.

When you think about how materials "get around" in the wild aquatic habitats, there are a few factors which influence both the accumulation and distribution of them. In many topical streams, the water depth and intensity of the flow changes during periods of rain and runoff, creating significant re-distribution of the materials which accumulate on the bottom, such as branches, leaves, seed pods, and the like.

Larger, more "hefty" materials, such as submerged logs, etc., will tend to move less frequently, and in many instances, they'll remain stationary, providing a physical diversion for water as substrate materials accumulate around them.

Most of the smaller materials, like branches, seed pods, and leaves may tend to move around quite a bit before ultimately settling and accumulating in a specific area-perhaps one with less flow, natural barriers like branches or fallen trees, a different bottom "topography", and other structural aspects, like bends and riffles.

Sometimes, seasonal flooding or overflowing streams run through previously terrestrial habitats, with the water moving materials around considerably. One might say that the "material changes" to the environments created by this movement of materials can have significant implications for fishes. In the wild, they follow the food, often existing in, and subsisting off of what they can find in these areas.

Yeah...They tend to be attracted to areas where food supplies are relatively abundant, requiring little expenditure of energy in order to satisfy their nutritional needs. Insects, crustaceans, and yeah- tiny fishes- tend to congregate and live around floating plants, masses of algae, and fallen botanical items (seed pods, leaves, etc.), so it's only natural that our subject fishes would be attracted to these areas...I mean, who wouldn't want to have easy access to the "buffet line", right?

Right there, you can see that there is some predictability and utility in the "random" nature of aquatic habitats. They provide enormous support for life forms at many levels.

Any random stream in Nature contains inspiration and ideas which we can apply to our aquascapes, without having to overthink it. Sure, even the simple act of placing a piece of wood in our tanks requires someconsideration...

However, it think a lot of it boils down to what we are placing the emphasis on as aquarists. Perhaps it's less about perfect placement of materials for artistic purposes, and more about placing materials to facilitate more natural function and interactions between fishes and their environment.

We make those "mental shifts" and accept the dark water, the accumulation of leaves and botanicals, the apparent "randomness" of their presence. We study the natural habitats from which they come, not just for the way they look- but for WHY they look that way, and for how the impacts of the surrounding environments influence them in multiple ways.

It goes beyond just finding that perfect-looking branch or bunch of leaves to capture a "look." We've already got that down. We can go further...

Sure, embracing some different aesthetics can seem a bit- well, intimidating at first, but if you force yourself beyond just the basic hobby-oriented mindset out there on these topics, there is a whole world of stuff you can experience and learn about!

And the information you can gain from this process just might have an amazing impact on your aquarium practice; that might just lead to some remarkable breakthroughs that will forever change the hobby!

There is a tremendous amount of academic material out there for those willing to "deep dive" into this. And a tremendous amount to unravel and apply to our aquarium practices! We're literally just scratching the surface. We're making the shifts to accept the true randomness of Nature as it is. We are establishing and nurturing the art of "functional aesthetics."

I suppose that there are occasional smirks and giggles from some corners of the hobby when they initially see our tanks, with some thinking, "Really? They toss in a few leaves and they think that the resulting sloppiness is "natural", or some evolved aquascaping technique or something?"

Funny thing is that, in reality, it IS a sort of evolution, isn't it?

I mean, sure, on the surface, this doesn't seem like much: "Toss botanical materials in aquariums. See what happens." It's not like no one ever did this before. And to make it seem more complicated than it is- to develop or quantify "technique" for it (a true act of human nature, I suppose) is probably a bit humorous.

On the other hand, most of us already know that it's not just to create a cool-looking tank. It's not purely about aesthetics. The aesthetics are a "by-product" of the function we push for. And, another thing We don't embrace the dark, often turbid water, substrates covered in decomposing leaves and twigs, and the appearance of biofilms and fungal growths on driftwood because it allows us to be more "relaxed" in the care of our tanks, or because we think we're so much smarter than the underwater-diorama-loving, hype-mongering competition aquascaping crowd.

Well, maybe we are? 😆

Look, we are doing this for a reason: To create more authentic-looking, natural-functioning aquatic displays for our fishes. To understand and acknowledge that our fishes and their very existence is influenced by the habitats in which they have evolved.

Wild tropical aquatic habitats are influenced greatly by the surrounding geography, flora, and weather of their region, which in turn, have considerable influence upon the population of fishes which inhabit them, and their life cycle. It may appear to be a completely random process, but the reality is that it's surprisingly predictable, often tied into seasonal flood pulses and meteorological cycles.

It's something that we can recreate, to a certain extent- in our aquariums.

And, think about this: When we add botanical materials to an aquarium and accept what occurs as a result-regardless of wether our intent is just to create a different aesthetic, or perhaps something more- we are to a very real extent replicating the processes and influences that occur in wild aquatic habitats in Nature.

The presence of terrestrial botanical materials such as leaves, seed pods, and twigs in these aquatic habitats is fundamental to both these wild aquatic habitats, and to the aquariums we create to replicate them.

Random?

Maybe.

An aquarium is not just a glass or plastic box filled with water, sand, plants, wood, leaves, seed pods, and fishes.

It's not just a disconnected, clinical, static display containing a collection of aquatic materials.

It's a microcosm.

A vibrant, dynamic, interconnected ecosystem, influenced by the materials and life forms-seen and unseen- within it, as well as the external influences which surround it.

An aquarium features, life, death, and everything in between.

It pulses with the cycle of life, beholden only to the rules of Nature, and perhaps, to us- the human caretakers who created it.

But mainly, to Nature.

The processes of life which occur within the microcosm we create are indifferent to our desires, our plans, or our aspirations for it. Sure, as humans, we can influence the processes which occur within the aquarium- but the outcome- the result- is based solely upon Nature's response.

In the botanical-method aquarium, we embrace the randomness and unusual aesthetic which submerged terrestrial materials impart to the aquatic environment. We often do our best to establish a sense of order, proportion, and design, but the reality is that Nature, in Her infinite wisdom borne of eons of existence, takes control.

We have two choices: We can resist Nature's advances, attempt to circumvent or thwart her processes, such as decomposition, growth, or evolution.

Or, we can scrape away "unsightly" fungal growth and biocover on rocks and wood, remove detritus, algae, replace our leaves, and trim our plants to look neat and orderly.

Or, we can embrace Her seemingly random, relentless march, and reap the benefits of Her wisdom.

Stay thoughtful. Stay resourceful. Stay curious. Stay observant. Stay diligent...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Just...maintain! A little review on the maintenance of botanical-method aquariums.

One of the more common questions we receive here at Tannin, and via our social media accounts, is, "How do you maintain one of these (botanical method) aquariums?"

It really is a great question, because, although we've talked about it quite a bit over the last several years, it's a very fundamental item which we haven't talked about in detail recently... So, why not revisit it today?

As we've talked about before, for the longest time, there seemed to have been a perception among the mainstream aquarium hobby that tanks with lots of botanical materials were delicate, tricky-to-maintain systems, fraught with potential disaster; a soft-water, acidic environment which could slip precipitously into some sort of environmental "free fall" without warning. And there was the matter of that "dark brown water..."

And the aquairum hobby has, for decades, equated brown water with "dirty", "dangerous", and "non-sustainable..."

Perceptions which require a bit of examination and understanding of before we can successfully navigate the world of botanical method aquairums.

Yeah, like so many things in our little hobby speciality, it's a matter of understanding exactly what you're getting into. I think that the most difficult aspect of a botanical method aquarium is to understand exactly what it is, why it's set up the way it is, and how it actually works. The fundamentals are everything here.

So, how do we keep these aquariums running for extended periods of time? Through continuous, regular maintenance, of course! Let's talk about some of the "best practices" that we engage in to keep these tanks running and looking their best.

It starts with the way you set up your botanical method aquarium, and how it relies on natural processes to function.

If you're "converting" an existing aquarium, start slowly, gradually building up your quantities of botanical materials over a period of weeks, or even months, until you reach a level that you like aesthetically, and which provides the type of manageable environmental parameters you and your fishes are comfortable with. This is essential, because how we start our aquariums dictates how they will run over the longer term.

And of course, you'll need to understand the progression of things that happen as your tank establishes itself. And, perhaps most important, you'll need to make some mental "adjustments" to accept and appreciate this different function and aesthetic.

Also, you'll have to get used to a certain amount of material breaking down in your tank. It's natural, and part of the function... and the aesthetic. Accepting the fact that you'll see biofilms, fungal growth, detritus, and even some algae in your system is something that many aquarists have a difficult time with. As we've discussed numerous times here, it goes against our "aesthetic upbringing" with regards to what an "attractive, healthy-looking tank" is!

We have learned to understand and appreciate this stuff, and that accepting these things is not an excuse to develop or accept lax maintenance practices! It's understanding that this is part of the normal function of Nature. It's a "call to awareness" that there is probably nothing wrong with your system when you see this stuff. It's quite contrary to the way we've been "trained" to evaluate the aesthetics of a typical aquarium.

Okay, let's talk aesthetics, one more time...Watch some underwater videos and study photos of environments such as the Amazonian region, etc., and you'll see that your tank is a much closer aesthetic approximation of Nature than almost any other type of system you've worked with before, in both form and function.

This is a significant thing, really!

And, to your comfort, you'll find that botanical method aquariums are as stable as any other if you follow regular maintenance and good old common sense.

So, what are we talking about, in regards to regular maintenance?

Well, for one thing, water exchanges. Because the topic is so well discussed in the aquarium world, I'll keep it relatively brief on this topic:

What’s a good water-exchanging regimen?

I’d love to see you employ 10% per week...It’s what I’ve done for decades, and it’s served me- and my animals- very well! Regardless of how frequently you exchange your water, or how much of it you exchange- just do them consistently. And of course, as previously discussed, don't go crazy siphoning every bit of detritus out during the process.

Remember, that in an aquarium which encourages the growth of bacteria, fungi, copepods, etc., the organic material contained in detritus becomes part of the "food web." And everybody up the food chain can benefit from the stuff.

So, by going "full ham" and siphoning every last speck of detritus in your tank, you're essentially breaking this chain, and denying organisms at multiple levels the chance to benefit from it! Yeah, over-zealously siphoning this material from your tank effectively destroys an established community of microorganisms which serve to maintain high water quality in the closed environment of an aquarium!

This is a super-important point to remember!

In an ironic twist, I believe that it's far more common for those "anomalous" ammonia spikes and such that aquarists report periodically, to have their origin in over-zealous cleaning of aquariums and filter media, as opposed to the accumulation of detritus itself. So, yeah-taking out all of the "fish shit" is actually removing a complex microbiome that's keeping your tank healthy!

Even something as seemingly "mundane" as the way we maintain our botanical-method aquariums requires us to make some "mental shifts" to appreciate our methodology more thoroughly, doesn't it?

Now, during water exchanges, it's almost inevitable that some stuff gets shifted around. Leaves and seed pods are pretty lightweight materials, and as they decompose, they're even more lightweight and "mobile."

And that's not necessarily a bad thing. Don't get stressed if you stir some stuff up. Your tank will be fine.

Think about the natural leaf litter beds, and the processes which influence their composition, structure and resilience. Many litter beds are long-term "static" features in their natural habitats. Almost like reefs in the ocean, actually. Yet, there is a fair amount of material being shifted around constantly by current, rain, flooding, and the activities of fishes.

Yeah, stuff does get disturbed and redistributed.

The organisms which reside in these systems deal with these dynamics effectively. They have for eons.

The benthic microfauna which our fishes tend to feed on also are affected by this phenomenon, and as mentioned above, the fishes tend to "follow the food", making this a case of the fishes learning (?) to adapt to a changing environment.

And perhaps...maybe...the idea of fishes sort of having to constantly adjust to a changing physical (note I didn't say "chemical") environment could be some sort of "trigger", hidden deep in their genetic code, that perhaps stimulates overall health, immunity or spawning?

Something in their "programing" that says, "You're at home...the season has changed, because there's an influx of new water...leaves are rolling around..." Perhaps not as "specific", but something like that, which can trigger specific adaptive behaviors?

I find this possibility fascinating, because we can learn more about our fishes' behaviors, and create really interesting habitats for them, simply by adding botanicals to our aquariums and allowing them to "do their own thing"- to break apart as they decompose, move about as we change water or conduct maintenance activities, or to be added to from time to time.

Well, I mentioned the whole "breaking down" part about botanicals here, so I should say a little about that.

As we have discussed for years, botanical materials break down and start decomposing as soon as they are added to your aquarium. It's normal. It's natural. It's to be expected. Some materials, like the harder seed pods, last a very long time- almost indefinitely- before they finally are broken down by biological activity. Other stuff, like softer seed pods and leaves, tend to break down much more quickly.

Yeah, leaves should be considered the most "temporary" or ephemeral items we utilizing in our botanical method tanks, requiring replacement regularly. Those seed pods and stems tend to last longer and it's personal preference to leave them in, or remove as desired.

So, DO you remove the botanical materials from your aquarium as they break down?

For reasons I've touched on numerous time here in "The Tint", I personally like to leave all of these materials in the aquarium until they completely break down, which I believe facilitates the very ecological processes which help the ecosystem of our aquariums run. And, leaving the material "in situ" while it breaks down does NOT "pollute" the aquarium, if it's otherwise well managed (ie; if you conduct regular water exchanges, filter media replacements, feed carefully, and stock sensibly, etc.).

I think that we need to look beyond the simple "aesthetic" of the leaves and other botanicals in our tanks, and consider them more than just hardscape "props." Rather, they are functional materials, which perform biological, environmental, and physical/structural roles in the aquarium- just as they do in Nature.

The same processes and functions which govern what happens to these materials in the wild occur in our aquariums. And, if we reject our initial instinct to "edit" what Nature does, the aquarium takes on a look and vibrancy that only She can create. It's that simple. "For best results, don't fuck with it!"

I wouldn't get too carried away with trying to remove any of it, really.

Remember, most of this "stuff"- the broken-down botanical and the resulting detritus and such- is utilized by organisms throughout the food chain in your tank...and as such, is a "fuel" for the biological processes we are so interested in.

No sense disrupting them, right?

What goes down...doesn't always have to come up.

Take care of your tank by taking care of the enormous microcosm which supports its form and function. And that means, not removing all of this material as it decomposes. I know, I've said it several times already in this one piece, and countless times in "The Tint" and elsewhere, but it's really a fundamental part of the botanical method of aquarium keeping.

One physical maintenance task that I have found to be continuous and necessary is the cleaning of filter intakes, mechanical filter media, and water pumps. With a constantly-decomposing array of botanical materials streaming into the water column, lots of small debris tend to get sucked into filter intakes, pumps, and of course, mechanical filter media. These need to be cleaned/replaced on a regular basis; perhaps even more frequently than other maintenance tasks.

It's simply part of the game when working with a botanical-method aquarium!

There are other "tricks" to maintaining environmental consistency in botanical method aquariums, which we can re-visit in future installments. The bottom line here, though, is that these aquariums are no more difficult to maintain than any other type of system we work with in the hobby. They simply require a basic understanding of ecological/biological processes, and how they play out in our tanks. It requires patience, consistency, and execution- attributes which are ideal for any hobbyist to possess.

Our idea of what a beautiful, healthy aquarium is may vary substantially from the "mainstream" aesthetically- but you won't be able to make that argument from a functional perspective when you employ common, well-known aquarium maintenance practices.

Just remember that the long term success of botanical method aquariums requires a mix of knowledge and action...nothing all that different from what you've already come to understand in the aquarium hobby.

Just..maintain. Literally!

Stay persistent. Stay observant. Stay curious. Stay thoughtful. Stay patient...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Transitioning a botanical method aquarium: A Case Study

One of the best things about a botanical-method aquairum is that it is a dynamic, evolving, and, well "flexible" environment to work with. By its very nature, the botanical-method aquarium changes- and can be changed- with relatively little effort on our part, while still embracing natural processes.

Case in point has been the little tank we've featured recently- a deliberate attempt to highlight this "pivotable" nature of botanical method aquariums. It started life as one of our "classic" configurations- a leaf litter habitat. A simple aquarium, which consists of a sprinkling of sand, a bunch of leaves, and a few twigs.

Botanical method aquarium-keeping at its most simple and elegant.

As you know, we've done a number of aquariums like this over the years, and they have been among our favorites. They're easy to create, really easy to manage, and teach you almost everything you need to know about running a botanical-method aquarium. You will learn about preparation of the materials, how they interact with water, and what life forms colonize them (ie; biofilms and fungal growths).

This configuration is a perfect "testbed" for the idea that botanical method aquariums can generate their own supplemental food sources for their inhabitants, if allowed to develop undisturbed for a while.

It's also a great "foundation" for other experiments with botanical method aquariums, as we'll discuss shortly.

One of the things that I love the most about this approach is that you can use such a small variety of materials, yet achieve a dramatic, ecologically rich aquarium with ease. The most important task is to prepare the leaves in order for them to sink and be able to recruit biofilms and fungal growths quickly, and ultimately decompose.

Then, it's really a matter of simply waiting for the "bloom" of biological activity. You also have the option of "inoculating" your tank with bacterial supplements or cultures of microorganisms, like Paramecium, etc., as well as copepods or organisms like Daphnia or Cyclops. These are fun little experiments that can really help you create a functional little ecosystem from the outset, and help provide some supplemental food sources for your fishes when they're added.

The idea couldn't be more simple. The execution is really easy. The environmental evolution which arises couldn't be more interesting! Yeah, easy. In fact, it was really a matter of setting in the leaves and twigs, and...doing nothing. Fungal growths form. Biofilms are recruited. Leaves soften and ultimately decompose...Stuff that will happen without any real intervention on your part...

This is really easy.

From an aesthetic perspective, this type of aquarium, by virtue of the fact that it uses a large amount of botanical materials, achieves a sort of "established" look very quickly. And from a functional standpoint, I find that these "leaf-litter-centric" systems seem to "settle down" and stabilize rather quickly, too. Very little fluctuation in the water parameters seems to occur after the initial setup, if lthey're eft undisturbed.

I could have managed this tank much like I had managed leaf litter systems in the past...Indefinitely letting it evolve, occasionally topping off with new leaves. Making few, if any changes of any kind.

Yet, that was not the destiny I had in mind for this tank.

The idea behind this tank was to demonstrate that you could create a heavily botanically-influenced aquarium, yet "transition" if you want, and easily keep and grow aquatic plants in the system as well. The "transitional" part was when I added aquatic plants.

Taking this aquarium from a "hardscape" ( to steal an aquascaping term) to a "quasi-biotopic" planted aquarium was a fun! I envisioned a section of a Southeast Asian stream, where the epiphytic Microsorum is growing on some submerged twigs and branches near the shoreline.

I've seen videos of this feature a few times, and was always taken by the extremely luxurious growth of Java Fern right over and into a section of terrestrial material. The dark water, lighter colored sand, and mass of decomposing leaves and branches made this too irresistible to overlook!

Once again, the interplay of the terrestrial and the aquatic habitats is incredible and alluring to me. And, since there was little substrate in this tank, keeping regionally appropriate rooted plants, like Cryptocoryne, was not possible from the outset. The epiphytic nature of Java Fern made it a perfect plant for this tank!

The idea wasn't just to place a few specimens of Microsorum here and there on the wood. Rather, it was to pack it heavily with them, creating a lush, overgrown look immediately. I'd rather be in the position of having to thin out and prune a slow-growing plant in a few weeks than be waiting for a few specimens of said slow-growing plant to cover a large surface area!

(See- I can be impatient!)

The idea of a dark, earthy, yet lushly planted aquarium has always appealed to me. Yeah, even though I'm not known for my use of plants in my work, I have been a fan of this "jungle"-type of approach to aquatic plants for many years. Interestingly, when I peruse images of the "Nature Aquarium" style aquairums, it's always the more lush, almost "overgrown"-looking tanks that catch my eye.

I am a firm believer in Takashi Amano's embrace of the Japanese philosophy of "Wabi-Sabi"- an acceptance of the transient nature of things, and their natural imperfections. And the approach I took with this tank- creating an evolving, semi-ephemeral "hardscape" of leaves and twigs, utilizing a significant quantity of just one species of plant, and allowing it to grow extensively in the tank, is as close to wabi-sabi as you'll ever see me deliberately come!

Now, one thing I did was to "corral" most of the leaf litter into and among the matrix of branches. I did this because I wanted to see some exposed substrate for contrast, and wanted to emulate and emphasize the way leaf litter accumulates among submerged roots in Nature.

The inhabitants had to be a species of Rasbora, (R. hengeli) and one of my long-coveted fishes, Vaillant's Chocolate Gourami", Sphaerichthys vaillanti. This fish is an idea candidate for such a tank. Not only is the tank reasonably small, so I could actually see this shy fish now and again- it has deeply tinted water, and is further darkened with the thick matrix of branches and dense aquatic vegetation- a perfect representation of their wild habitat!

I really want to impress upon you how easy this aquairum is to equip, set up, run, and manage. You could easily get by with less "gear" than I used.

Let's do a quick "recap" of the materials used for this setup:

EQUIPMENT

Aquarium: Ultum Nature Systems "60S" (23.62'x14.17"x7.09")- 10 U.S. Gallons

Filter: Aqueon "Quietflow AT10" Internal Filter

NATURAL MATERIALS

Substrate: CaribSea "Sunset Gold" sand, Tannin NatureBase "Varzea" sedimented substrate (Substrate materials were mixed together to create a substrate layer approximately 1/4"-1/2" inch (.635- 1.27cm) deep ).

Live Oak Leaf Litter

Large Oak Twigs

A few pieces of Borneo Catappa Bark

Java Fern "Narrow Mini"

And that's it...

Now, these are the things that I used...You can certainly set up similar tank utilizing different equipment and materials. A lot of hobbyists would have used a canister filter, which I've done in the past. However, as you know, I pretty much despise all cannister filters for reasons I can't always quite articulate, so I opted for the small internal filter. And you don't have to use a surface skimmer, but I hate surface film, so in non-overflow-equipped tanks, it's a "necessary evil" for me.

Yes, the equipment is visible unless you go to some lengths to hide it (part of the reason why everyone loves canisters!), but my "upside" is that I don't have to deal with that damn "glassware" (one of the most awful, shortsighted inventions in the history of aquarium keeping, IMHO. Absolutely stupid, overpriced, fragile, and shitty, in case you had doubts as to my position about glassware! 😆).

Deep breath, Scott...

So, it was sort of a "lesser of two evils" thing for me!

Personally, if a decent "all-in-one" aquarium with similar dimensions were available, I would have grabbed one in a heartbeat! An AIO aquarium can have surface skimming, "filtration", and a place to hide the heater all in one convenient, aesthetically clean design.

IMHO, the lack of AIO's with more interesting dimensions and sizes is one of the great missed opportunities in the aquarium industry. I think they'd be "smash-hit" sellers...Someone needs to take the chance and step up! Better yet- some manufacturer needs to consult with me on this....😆

Oh, but this piece isn't about my rantings against the aquarium industry, so let's get back to the topic.

So, managing this aquarium really couldn't be easier. My maintenance procedure includes exchanging 1 gallon/4L of water a week, cleaning the surface skimmer, and wiping away any algae I might encounter on the front glass (since the tank gets partial sun at certain times of the day, once little section of the glass occasionally gets. little algae film).

And that's it. Easy. Literally, this tank is on cruise control. Oh , I do add .50ml of Seachem Flourish Excel three times a week. I have yet to need to "top off" the leaves in the tank, as oak is pretty durable and tends to hang around a very long time before completely breaking down.

One of the cool things about a botanical method aquarium like this one is that you can observe the fungal bloom and gradual decline among the leaves, and upon the oak branches. Initially, there was significant fungal growth among the leaf litter, in particular.

However, as always occurs in botanical method aquariums, the initial significant bloom of fungal growth always subsides to a vary manageable, more "aesthetically pleasing" level, and remains that way for the duration of the aquariums existence.

It's yet another one of those "mental shifts" we ask you to make as a botanical method aquarium keeper. Being patient with your aquarium as it evolves. And the beautiful thing is that, when you do this, the aquarium often becomes something better than you initially envisioned.

The beauty of an aquarium like this one is that you can make a few "tweaks" to the theme along the way without issues, as we've discussed many times. This type of "baseline" "leaf-litter-centric" tank gives you a track to run on, and then you can make subtle changes without impacting the "operating system" of the aquarium.

In the end, living with your botanical method aquarium isn't just about a new aesthetic approach. It's about understanding and processing what's happening in the little aquatic ecosystem you've created. It's about asking questions, modifying technique, and playing hunches- all skills that we as hobbyists have practiced for generations.

When you distill it all- we're still just "keeping an aquarium"...but one that I feel embraces a far more natural, dynamic, and potentially game-changing methodology for the hobby.

Stay creative. Stay flexible. Stay excited. Stay bold. Stay curious...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

The process: The "How and Why?" of Botanical Preparation...

Some 7 years into the adventure that is Tannin Aquatics, and the world of botanical method aquariums seems to be exploding! There are more hobbyists creating these types of aquariums than ever before, more vendors offering botanical materials, and more information!

And of course, there is lingering confusion and even mis-information. The kind of stuff that can confuse any newcomer to our little sector, and actually prevent many people from succeeding with these types of aquariums. There is a surprisingly large amount of bad information out there on some of the most basic processes we employ.

To this end, I think it's time for me to do a periodic review of some of the fundamentals of our practice and processes. Let's start with one of the most basic- the art and science of botanical preparation.

"Preparation required..."

Words you've heard us utter again and again; precautions you've seen us advise you to take. You see it on our packaging, hear it discussed on "The Tint" podcast, and read about it in articles we publish here and elsewhere. Yet, there appears to be some confusion about what exactly we mean by "preparation."

Yeah, it's not a secret that, before you throw those seed pods and leaves into your aquarium, you need to do some preparation.

Why?

And why are we talking about this again?

Well, seriously, I still receive about 3-4 emails every single week from customers of ours (and from others, apparently!) asking what to do with botanicals after they receive them...So, it's obvious to me that some people just aren't seeing this stuff, hearing it, reading our instructional cards, social media posts, etc., or not getting advice from the people they purchased their leaves, or whatever from. (Isn't EBay great! What a resource for serious hobbyists!)

Really?

Yup.

I know, it's starting to sound a bit repetitive...

However, with the world botanical-style aquariums growing at an exponential rate, and more and more hobbyists entering into the fray- many of whom are enamored by the beautiful aesthetics of these tanks, it's important-well, actually essential- to revisit this stuff again and again.

And really, because most of the new vendors into our market space simply appropriate much of the information we put out to help the community, and use it to push their products, let's at least give those lazy-ass motherfuckers something useful to share (and since they're not bothering to provide this information, themselves...)!

Okay, mini-hate-rant over. For now.

"So, you're really into boiling and steeping botanical, huh?

Yes. I am. That's my thing.

"Why do you do that?"

Consider that boiling water is used as a method of making water potable by killing microbes that may be present. Most nasty microbes essentially "check out" at temperatures greater than 60 °C (140 °F). For a high percentage of microbes, if water is maintained at 70 °C (158 °F) for ten minutes, many organisms are killed, but some are more resistant to heat and require one minute at the boiling point of water. (FYI the boiling point of water is 100 °C, or 212 °F)...But for the most part, most of the nasty bacteria that we don't want in either our tanks or our stomachs are eliminated by this simple process.

So, wouldn't it make sense to boil, or at least steep, our botanicals before we dump them into our aquariums?

Yeah, it would.

Ten minutes of boiling is "golden" to assure a "good kill", IMHO. Of course, we boil for other reasons, too-as we'll touch on in a bit.

The most important reason that we boil botanicals is to kill any possible microorganisms which might be present on them. Leaves, seed pods, etc. have been exposed to rain and dust and all sorts of things in the natural environment which, in the confines of an aquarium, could introduce unwanted organisms and contribute to the degradation of the water quality.

And, the surfaces and textures of many botanical items, such as leaves and seed pods lend themselves to retaining dirt, soot, dust, and other atmospheric pollutants that, although quite likely harmless in the grand scheme of things, are not stuff you want to start our with in your tank!

So, we give all of our botanicals a good rinse with fresh water.

Then we boil them.

Boiling also serves to soften botanicals. This is important to do for a number of reasons...

Well, the most obvious to us is thats it helps saturate the tissues of the botanicals and make them sink. I mean, who wants a bunch of floating seed pods and leaves in their aquairum? Wait, don't tempt me here...

If you remember your high school Botany (I actually do!), leaves, for example, are surprisingly complex structures, with multiple layers designed to reject pollutants, facilitate gas exchange, drive photosynthesis, and store sugars for the benefit of the plant on which they're found. As such, it's important to get them to release some of the materials which might be bund up in the epidermis (outer layers) of the leaf. As we get deeper into the structure of a leaf, we find the mesophyll, a layer of tissue in which much of photosynthesis takes place.

We use only dried leaves in our botanical style aquariums, because these leaves from deciduous trees, which naturally fall off the trees in seasons of inclement weather, have lost most of their chlorophyll and sugars contained within the leaf structures. This is important, because having these compounds present, as in living leaves, contributes excessively to the bioload of the aquarium when submerged...

Personally, I feel that we have enough bioload going into our tanks, so why add to it by using freshly-fallen leaves with their sugars and such still largely present, right? I mean, it's definitely something worth experimenting with in controlled circumstances, but for most of us botanical method aquarium geeks, naturally fallen, dried leaves are the way to go.

The analogs to processes which occur in wild aquatic habitats are incredible, and part of the reason why, if left to "do their thing", that botanical method aquariums run in such a stable manner.

When leaves are placed into the water, they release some of the remaining "solutes" (substances which dissolve in liquids- in this instance, sugars, carbohydrates, tannins, etc.) in the leaf tissues rather quickly. Interestingly, this "leaching" is known by science to be more of an artifact of lab work (or, in our case, aquarium work!) which utilizes dried leaves, as opposed to fresh ones.

The most important part of the process of utilizing botanicals in leaves in aquariums is analogous to the natural process of decomposition, which ecologists call the "conditioning phase", during which microbial colonization on the leaf takes place. Bacteria begin to consume some of the tissues of the leaf- at least, softening it up a bit and making it more palatable to fungi.

This is, IMHO, the most important part of the process. It's the "main event"- the part which we as hobbyists embrace, because it leads to the development of a large population of organisms which, in addition to processing and exporting nutrients, also serve as supplemental food for our fishes!

The botanical material is broken down into various products utilized by a variety of other life forms. The particles are then distributed throughout the aquairum by the currents and are available for consumption by a variety of organisms which comprise aquatic food webs.

Six primary breakdown products are considered in the decomposition process: bacterial, fungal and shredder biomass; dissolved organic matter; fine-particulate organic matter; and inorganic mineralization products such as CO2, NH4+ and PO43-.

This is exactly what happens in Nature. And that's why we prepare our botanicals- because "prepared" botanical materials literally "kick start" the ecology of the aquarium!

An interesting fact: In tropical streams, a high decomposition rate has been related to high fungal activity...these organisms accomplish a LOT!

So, yeah, that's perhaps the biggest reason why we prepare leaves for aquarium use!

Are there variations on this prep theme?

Well, sure. Of course!

Many hobbyists rinse, then steep their leaves in boiling water, rather than a prolonged boil, for the simple fact that exposure to the newly-boiled water will accomplish the potential "kill" of unwanted organisms, which at the same time softening the leaves by permeating the outer tissues. This way, not only will the "softened" leaves "go to work" right away, releasing the beneficial tannins and humic substances bound up in their tissues, they will sink, too!

And of course, I know many who simply "rinse and drop", and that works for them, too! And, I have even played with "microwave boiling" some stuff (an idea forwarded on to me a few years back by aquascaper Cory Hopkins). It does work, and it makes your house smell pretty nice, too!

It's not a perfect science- this leaf preparation "thing."

And I admit, I've changed some of my approaches over the years...I'd be foolish not to.

Of course, the fundamental idea behind preparation of botanicals hasn't really changed too much. And the underlying rationale hasn't changed, either.

Leaf preparation has evolved quite a bit, actually! Many aquarists have developed simple approaches to leaf prep that work with a high degree of reliability. Now, there are some leaves, such as Magnolia, which take a longer time to saturate and sink because of their thick, waxy cuticle layer. And there are others, like Loquat, which can be undeniably "crispy", yet when steeped begin to soften and work just fine.

There is no 100% guaranteed way to perfectly prep every botanical or leaf the same way every single time.

You have to be flexible and adaptable.

So why do we soak after boiling?

Well, it's really a personal preference thing.I suppose one could say that I'm excessively conservative, really. Do you HAVE to?

No. However....

I feel that it releases any remaining pollutants and undesirable organics that might have been bound up in the leaf tissues and released by boiling, which is certainly arguable, but is also, IMHO, a valid point. And since we're a company dedicated to giving our customers the best possible outcomes- we recommend being conservative and employing the post-boil soak.

The soak could be for a half an hour, an hour or two, or even overnight...no real "science" to it. Some aquarists would argue that you're wasting all of those valuable tannins and humic substances when you soak the leaves overnight after boiling. I call total bullshit on that. My response has always been that you might lose some, but since the leaves have a "lifespan" of weeks, even months, and since you'll see tangible results from them (i.e.; tinting of the water) for much of this "operational lifespan", an overnight soak is no big deal in the grand scheme of things.

So don't stress over that, okay?

Do what's most comfortable for you- and okay for your fishes.