- Continue Shopping

- Your Cart is Empty

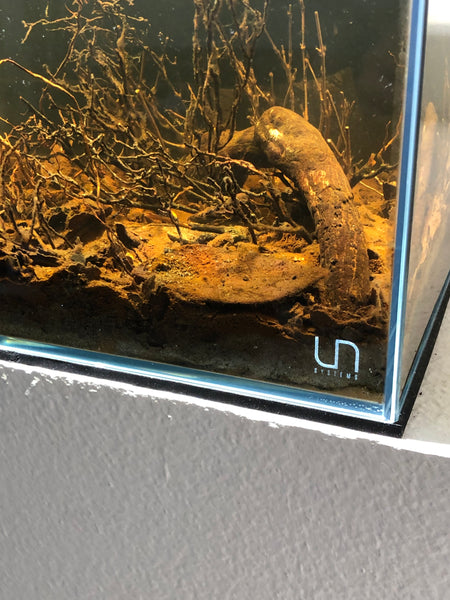

The Botanical-Style Aquarium: A "filter" of its own, and other biological musings...

A big thought about our botanical-style aquariums:

The aquarium-or, more specifically- the botanical materials which comprise the botanical-style aquarium "infrastructure" acts as a biological "filter system."

In other words, the botanical materials present in our systems provide enormous surface area upon which beneficial bacterial biofilms and fungal growths can colonize. These life forms utilize the organic compounds present in the water as a nutritional source.

Oh, the part about the biofilms and fungal growths sounds familiar, doesn't it?

Let's talk about our buddies, the biofilms, just a bit more. One more time. Because nothing seems as contrary to many hobbyists than to sing the praises of these gooey-looking strands of bacterial goodness!

Structurally, biofilms are surprisingly strong structures, which offer their colonial members "on-board" nutritional sources, exchange of metabolites, protection, and cellular communication. They form extremely rapidly on just about any hard surface that is submerged in water.

When I see aquarium work in which biofilms are considered a "nuisance", and suggestions that it can be eliminated by "reducing nutrients" in the aquarium, I usually cringe. Mainly, because no matter what you do, biofilms are ubiquitous, and always present in our aquariums. We may not see the famous long, stringy "snot" of our nightmares, but the reality is that they're present in our tanks regardless.

The other reality is that biofilms are something that we as aquarists typically fear because of the way they look. In and of themselves, biofilms are not harmful to our fishes. They function not only as a means to sequester and process nutrients ( a "filter" of sorts?), they also represent a beneficial food source for fishes.

Now, look, I can see rare scenarios where massive amounts of biofilms (relative to the water volume of the aquarium) can consume significant quantities of oxygen and be problematic for the fishes which reside in your tank. These explosions in biofilm growth are usually the result of adding too much botanical material too quickly to the aquarium. They're excaserbated by insufficient oxygenation/circulation within the aquarium.

These are very unusual circumstances, resulting from a combination of missteps by the aquarist.

Typically, however, biofilms are far more beneficial that they are reven emotely detrimental to our aquariums.

Nutrients in the water column, even when in low concentrations, are delivered to the biofilm through the complex system of water channels, where they are adsorbed into the biofilm matrix, where they become available to the individual cells. Some biologists feel that this efficient method of gathering energy might be a major evolutionary advantage for biofilms which live in particularly in turbulent ecosystems, like streams, (or aquariums, right?) with significant flow, where nutrient concentrations are typically lower and quite widely dispersed.

Biofilms have been used successfully in water/wastewater treatment for well over 100 years! In such filtration systems the filter medium (typically, sand) offers a tremendous amount of surface area for the microbes to attach to, and to feed upon the organic material in the water being treated. The formation of biofilms upon the "media" consume the undesirable organics in the water, effectively "filtering" it!

Biofilm acts as an adsorbent layer, in which organic materials and other nutrients are concentrated from the water column. As you might suspect, higher nutrient concentrations tend to produce biofilms that are thicker and denser than those grown in low nutrient concentrations.

Those biofilms which grow in higher flow environments, like streams, rivers, or areas exposed to wave action, tend to be denser in their morphology. These biofilms tend to form long, stringy filaments or "streamers",which point in the direction of the flow. These biofilms are characterized by characteristic known as "viscoelasticity." This means that they are flexible, and stretch out significantly in higher flow rate environments, and contract once again when the velocity of the flow is reduced.

Okay, that's probably way more than you want to know about the physiology of biofilms! Regardless, it's important for us as botanical-style aquarists to have at least a rudimentary understanding of these often misunderstood, incredibly useful, and entirely under-appreciated life forms.

And the whole idea of facilitating a microbiome in our aquariums is predicated upon supplying a quantity of botanical materials- specifically, leaf litter, for the beneficial organisms to colonize and begin the decomposition process. An interesting study I found by Mehering, et. al (2014) on the nutrient sequestration caused by leaf litter yielded this interesting little passage:

"During leaf litter decomposition, microbial biomass and accumulated inorganic materials immobilize and retain nutrients, and therefore, both biotic and abiotic drivers may influence detrital nutrient content."

The study determined that leaves such as oak "immobilized" nitrogen. Generally thinking, it is thought that leaf litter acts as a "sink" for nutrients over time in aquatic ecosystems.

Oh, and one more thing about leaves and their resulting detritus in tropical streams: Ecologists strongly believe that microbial colonized detritus is a more palatable and nutritious food source for detritivores than uncolonized dead leaves. The microbial growth which occurs on the leaves and their resulting detritus increases the nutritional quality of leaf detritus, because the microbial biomass on the leaves is more digestible than the leaves themselves (because of lignin, etc.).

Okay, great. I've just talked about decomposing leaves and stuff for like the 11,000th time in "The Tint"; so...where does this leave us, in terms of how we want to run our aquariums?

Let's summarize:

1) Add a significant amount of leaf litter, twigs, and botanicals to your aquarium as part of the substrate.

2) Allow biofilms and fungal growths to proliferate.

3) Feed your fishes well. It's actually "feeding the aquarium!"

4) Don't go crazy siphoning out every bit of detritus.

Let's look at each of these points in a bit more detail.

First, make liberal use of leaf litter in your aquarium. I'd build up a layer anywhere from 1"-4" of leaves. Yeah, I know- that's a lot of leaves. Initially, you'll have a big old layer of leaves, recruiting biofilms and fungal growths on their surfaces. Ultimately, it will decompose, creating a sort of "mulch" on the bottom of your aquarium, rich in detritus, providing an excellent place for your fishes to forage among.

Allow a fair amount of indirect circulation over the top of your leaf litter bed. This will ensure oxygenation, and allow the organisms within the litter bed to receive an influx of water (and thus, the dissolved organics they utilize). Sure, some of the leaves might blow around from time to time- just like what happens in Nature. It's no big deal- really!

The idea of allowing biofilms and fungal growths to colonize your leaves and botanicals, and to proliferate upon them simply needs to be accepted as fundamental to botanical-style aquarium keeping. These organisms, which comprise the biome of our aquariums, are the most important "components" of the ecosystems which our aquariums are.

I'd be remiss if I didn't at least touch on the idea of feeding your aquarium. Think about it: When you feed your fishes, you are effectively feeding all of the other life forms which comprise this microbiome. You're "feeding the aquarium." When fishes consume and eliminate the food, they're releasing not only dissolved organic wastes, but fecal materials, which are likely not fully digested. The nutritional value of partially digested food cannot be understated. Many of the organisms which live within the botanical bed and the resulting detritus will assimilate them.

Now, we could go on and on about this topic; there is SO much to discuss. However, let's just agree that feeding our fishes is another critical activity which provides not only for our fishes' well-being, but for the other life forms which create the ecology of the aquarium.

And, let's be clear about another thing: Detritus, the nemesis of many aquarists- is NOT our enemy. We've talked about this for several years now, and I cannot stress it enough: To remove every bit of detritus in our tanks is to deprive someone, somewhere along the food chain in our tanks, their nutritional source. And when you do that, imbalances occur...You know, the kinds which cause "nuisance algae" and those "anomalous tank crashes."

The definition of this stuff, as accepted in the aquarium hobby, is kind of sketchy in this regard; not flattering at the very least:

"detritus is dead particulate organic matter. It typically includes the bodies or fragments of dead organisms, as well as fecal material. Detritus is typically colonized by communities of microorganisms which act to decompose or remineralize the material."

Shit, that's just bad branding.

The reality is that this not a "bad" thing. Detritus, like biofilms and fungi, is flat-out misunderstood in the hobby.

Could there be some "upside" to this stuff?

Of course there is.

I mean, even in the above the definition, there is the part about being "colonized by communities of microorganisms which act to decompose or remineralize..."

It's being processed. Utilized. What do these microorganisms do? They eat it...They render it inert. And in the process, they contribute to the biological diversity and arguably even the stability of the system. Some of them are utilized as food by other creatures. Important in a closed system, I should think.

This is really important. It's part of the biological operating system of our botanical-style aquariums. I cannot stress this enough.

Now, I realize that the idea of embracing this stuff- and allowing it to accumulate, or even be present in your system- goes against virtually everything we've been indoctrinated to believe in about aquarium husbandry. Pretty much every article you see on this stuff is about its "dangers", and how to get it out of your tank. I'll say it again- I think we've been looking at detritus the wrong way for a very long time in the aquarium hobby, perceiving it as an "enemy" to be feared, as opposed to the "biological catalyst" it really is!

In essence, it's organically rich particulate material that provides sustenance, and indeed, life to many organisms which, in turn, directly benefit our aquariums.

We've pushed this narrative many times here, and I still think we need to encourage hobbyists to embrace it more.

Yeah, detritus.

Okay, I'll admit that detritus, as we see it, may not be the most attractive thing to look at in our tanks. I'll give you that. It literally looks like a pile of shit! However, what we're talking about allowing to accumulate isn't just fish poop and uneaten food. It's broken-down materials- the end product of biological processing. And, yeah, a wide variety of organisms have become adapted to eat or utilize detritus.

There is, of course, a distinction.

One is the result of poor husbandry, and of course, is not something we'd want to accumulate in our aquariums. The other is a more nuanced definition.

As we talk about so much around here- just because something looks a certain way doesn't mean that it alwaysa bad thing, right?

What does it mean? Take into consideration why we add botanicals to our tanks in the first place. Now, you don't have to have huge piles of the stuff littering your sandy substrate. However, you could have some accumulating here and there among the botanicals and leaves, where it may not offend your aesthetic senses, and still contribute to the overall aquatic ecosystem you've created.

If you're one of those hobbyists who allows your leaves and other botanicals to break down completely into the tank, what really happens? Do you see a decline in water quality in a well-maintained system? A noticeable uptick in nitrate or other signs? Does anyone ever do water tests to confirm the "detritus is dangerous" theory, or do we simply rely on what "they" say in the books and hobby forums?

Is there ever a situation, a place, or a circumstance where leaving the detritus "in play" is actually a benefit, as opposed to a problem?

I think so. Like, almost always.

Yes, I know, we're talking about a closed ecosystem here, which doesn't have all of the millions of minute inputs and exports and nuances that Nature does, but structurally and functionally, we have some of them at the highest levels (ie; water going in and coming out, food sources being added, stuff being exported, etc.).

There is so much more to this stuff than to simply buy in unflinchingly to overly-generalized statements like, "detritus is bad."

The following statement may hurt a few sensitive people. Consider it some "tough love" today:

If you're not a complete incompetent at basic aquarium husbandry, you won't have any issues with detritus being present in your aquarium.

Just:

Don't overstock.

Don't overfeed.

Don't neglect regular water exchanges.

Don't fail to maintain your equipment.

Don't ignore what's happening in your tank.

This is truly not "rocket science." It's "Aquarium Keeping 101."

And it all comes full circle when we talk about "filtration" in our aquariums.

People often ask me, "What filter do you use use in a botanical-style aquarium?" My answer is usually that it just doesn't matter. You can use any type of filter. The reality is that, if allowed to evolve and grow unfettered, the aquarium itself- all of it- becomes the "filter."

You can embrace this philosophy regardless of the type of filter that you employ.

My sumps and integrated filter compartments in my A.I.O. tanks are essentially empty.

I may occasionally employ some activated carbon in small amounts, or throw some "Shade" sachets in there if I am feeling it- but that's it. The way I see it- these areas, in a botanical-style aquarium, simply provide more water volume, more gas exchange; a place for bacterial attachment (surface area), and perhaps an area for botanical debris to settle out. Maybe I'll remove them, if only to prevent them from slowing down the flow rate of my return pumps.

But that's it.

A lot of people are initially surprised by this. However, when you look at it in the broader context of botanical style aquariums as miniature ecosystems, it all really makes sense, doesn't it? The work of these microorganisms and other life forms takes place throughout the aquarium.

I admit, there was a time when I was really fanatical about making sure every single bit of detritus and fish poop and all that stuff was out of my tanks. About undetectable nitrate. I was especially like that in my earlier days of reef keeping, when it was thought that cleanliness was the shit!

It wasn't until years into my reef keeping work, and especially in my coral propagation work, that I begin to understand the value of food, and the role the it plays in aquatic ecosystems as a whole. And that "food" means different things to different aquatic organisms. The idea of scrubbing and removing every single trace of what we saw as "bad stuff" from our grow-out raceways essentially deprived the corals and supporting organisms of an important natural food source.

We'd fanatically skim and remove everything, only to find out that...our corals didn't look all that good. We'd compensate by feeding more heavily, only to continue to remove any traces of dissolved organics from the water...

It was a constant struggle- the metaphorical "hamster wheel"- between keeping things "clinically clean" and feeding our animals. We were super proud of our spotless water. We had a big screen when you came into our facility showing the parameters in each raceway. Which begged the question: Were we interested in creating sterile water, or growing corals?

Eventually, it got through my thick skull that aquariums- just like the wild habitats they represent-are not spotless environments, and that they depend on multiple inputs of food, to feed the biome at all levels. This meant that scrubbing the living shit (literally) out of our aquariums was denying the very biotia which comprised our aquariums their most basic needs.

That little "unlock" changed everything for me.

Suddenly, it all made sense.

This has carried over into the botanical-style aquarium concept: It's a system that literally relies on the biological material present in the system to facilitate food production, nutrient assimilation, and reproduction of life forms at various trophic levels.

It's changed everything about how I look at aquarium management and the creation of functional closed aquatic ecosystems.

It's really put the word "natural" back into the aquarium keeping parlance for me. The idea of creating a multi-tiered ecosystem, which provides a lot of the requirements needed to operate successfully with just a few basic maintenance practices, the passage of time, a lot of patience, and careful observation.

It means adopting a different outlook, accepting a different, yet very beautiful aesthetic. It's about listening to Nature instead of the asshole on Instagram with the flashy, gadget-driven tank. It's not always fun at first for some, and it initially seems like you're somehow doing things wrong.

It's about faith. Faith in Mother Nature, who's been doing this stuff for eons.

It's about nuance.

It's about looking at things a bit different that we've been "programmed" to do in the aquarium hobby for so long. It's about not being afraid to question the reasons why we do things a certain way in the hobby, and to seek ways to evolve and change practices for the benefits of our fishes.

It takes time to grasp this stuff. However, as with so many things that we talk about here, it's not revolutionary...it's simply an evolution in thinking about how we conceive, set up, and manage our aquariums.

Sure, the aquairum is a "filter" of sorts, if you want to label it as such. However, it's so much more: A small, evolving ecosystem, relying on natural processes to bring it to life.

Wrap you head around that.

It might just change everything in the hobby for you.

Stay open-minded. Stay thoughtful. Stay bold. Stay curious. Stay diligent. Stay observant...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Evolving techniques

It's kind of fun to make little "tweaks" or adjustments to our aquarium methodology or approaches to how we do certain things. This is what pushes the state of the art in aquaristics further down the road. Now, not every one of these adjustments is a quantum leap forward, at least, not initially. Many are simply subtle iterations of things we've played with before.

An example?

One of our fave approaches, sort of derived out of our "Urban Igapo" work, has been to "dry set" the aquarium. A sort of technique I call the "transitional approach."

Basically, all you're doing is adding the prepared botanicals and leaves to your aquarium before it's filled, and spraying them down with water and our sprayable Purple Non-Sulphur bacterial inoculant, "Nurture" to kick-start the biological processes. Let it sit. Spray it down daily.

Then fill it.

Unlike in our "Urban Igapo" approach, you're not trying to grow terrestrial grasses or plants during the "dry phase." You're simply creating and managing what will ultimately be the submerged habitat in your aquarium for a while before filling it.

I've done this a number of times and had great results.

Stupidly simple. Yet, profoundly different.

Why?

Because, rather than our "traditional" approach of adding the botanicals and leaves to the aquarium after it's already filled, you're sort of replicating what happens in Nature in the wild when forest floors and other terrestrial environments are inundated by overflowing streams and rivers.

The thing I like about this approach (besides how it replicates what happens in the wild) is that it gives you the ability to really saturate and soften the botanicals and leaves, and to begin the process of decomposition and bacterial colonization before you add the water.

When do you fill the aquarium?

You can wait a few days, a week or two, or as long s you'd like, really. The idea is to get the materials physically placed, and to begin the process of colonization and "softening" by fungi and bacterial biofilms- known as "conditioning" by ecologists who study these habitats.

And of course, fishes and invertebrates which live amongst and feed directly upon the fungi and decomposing leaves and botanicals will contribute to the breakdown of these materials as well! Aquatic fungi can break down the leaf matrix and make the energy available to feeding animals in these habitats. And look at this little gem I found in my research:

"There is evidence that detritivores selectively feed on conditioned leaves, i.e. those previously colonized by fungi (Suberkropp, 1992; Graca, 1993). Fungi can alter the food quality and palatability of leaf detritus, aecting shredder growth rates. Animals that feed on a diet rich in fungi have higher growth rates and fecundity than those fed on poorly colonized leaves. Some shredders prefer to feed on leaves that are colonized by fungi, whereas others consume fungal mycelium selectively..."

"Conditioned" leaves, in this context, are those which have been previously colonized by fungi! They make the energy within the leaves and botanicals more available to higher organisms like fishes and invertebrates!

We've long maintained that the appearance of biofilms and fungi on your botanicals and wood are to be celebrated- not feared. They represent a burgeoning emergence of life -albeit in one of its lowest and most unpleasant-looking forms- and that's a really big deal.

"Oh shit, he's going to talk about biofilms AGAIN!"

Well, just for a second.

Biofilms, as we probably all know by now, form when bacteria adhere to surfaces in some form of watery environment and begin to excrete a slimy, gluelike substance, consisting of sugars and other substances, that can stick to all kinds of materials, such as- well- in our case, botanicals. It starts with a few bacteria, taking advantage of the abundant and comfy surface area that leaves, seed pods, and even driftwood offer.

The "early adapters" put out the "welcome mat" for other bacteria by providing more diverse adhesion sites, such as a matrix of sugars that holds the biofilm together. Since some bacteria species are incapable of attaching to a surface on their own, they often anchor themselves to the matrix or directly to their friends who arrived at the party first.

It's a literal explosion of life. It's a gift from Nature. And we can all receive it and benefit from it!

Another advantage of this approach? The traditional "cycling" time of a new tank seems to go much faster. Almost undetectable, in many of my experiments. I can only hypothesize and assume that it's likely a result of all of the bacterial growth in the "terrestrial" phase, and the concurrent "conditioning" of the botanical materials.

Tannin's creative Director, Johnny Ciotti, calls this period of time when the biofilms emerge, and your tank starts coming alive "The Bloom"- a most appropriate term, and one that conjures up a beautiful image of Nature unfolding in our aquariums- your miniature aquatic ecosystem blossoming before your very eyes!

The real positive takeaway here: Biofilms are really a sign that things are working right in your aquarium! A visual indicator that natural processes are at work, helping forge your tank's ecosystem.

So, what about the botanicals?

The idea of utilizing botanicals in the aquarium can be whatever you want, sure. However, if you ask me (and you likely didn't)- the idea of utilizing these materials in our tanks has always been to create unique environmental conditions and foster a biome of organisms which work together to form a closed microcosm. That is incredible to me.

And the idea of "dry setting" your botanical materials and sort of "conditioning" them before adding the water, this "transitional approach", while not exactly some "revolutionary" thing, IS an evolutionary step in the development of botanical-style aquarium keeping.

The "transitional approach" is definitely a bit different than what we've done in the past, and may create a more stable, more biologically diverse aquarium, because you're already fostering a biome of organisms which will make the transition to the aquatic habitat and "do their thing" that much more quickly.

This IS unique.

We're talking about actually allowing some of the decomposition to start before water is ever added to our tanks. It's a functional approach, requiring understanding, research, and patience to execute. There's really nothing difficult about it.

And the aesthetics? They're going to be different than what you're used to, no doubt. They will follow as a result of the process, and will resemble, on a surprisingly realistic level, what you see in Nature.

But the primary reason is NOT for aesthetics...

The interactions and interdependencies between terrestrial and aquatic habitats are manifold, beneficial, and quite compelling to us as hobbyists. To be able to study this dynamic first hand, and to approach it somewhat methodically, is a significant change in our technique.

And yeah, it's almost absurdly easy to do.

The hard part is that it requires a bit more patience; not everyone will see the advantages, or value, and the trade-off between waiting to fill your tank and filling it immediately. It may not be one that some are willing to make.

If you do, however, you will get to see, firsthand, the fascinating dynamic between the aquatic and the terrestrial environment in a most intimate way.

It could change your thinking about how we set up aquariums.

It could.

At the most superficial level, it's an acknowledgement that, after many decades, we as hobbyists are acknowledging and embracing this terrestrial-aquatic dynamic. It's a really unique approach, because it definitely goes against the typical "aquatic only" approach that we are used to.

When you consider that many aquatic habitats start out as terrestrial ones, and accumulate botanical materials and provide colonization points for various life forms, and facilitate biological processes like nutrient export and production of natural food resources, the benefits are pretty obvious. Again, the "different aesthetics" simply come along as "part of the package"- both in Nature and in the aquarium.

Replicating this process and managing it in the aquarium also provides us as hobbyists highly unique insights into the function of these habitats.

From a hobby perspective, evolving and managing a closed ecosystem is really something that we should take to easily.

Setting up an aquarium in this fashion also provides us with the opportunity to literally "operate" our botanical-style aquariums; that is, to manage their evolution over time through deliberate steps and practices is not entirely unknown to us as aquarium hobbyists.

It's not at all unlike what we do with planted aquarium or reef aquarium. In fact, the closest analog to this approach is the so-called "dry start" approach to planted aquariums, except we're trying to grow bacteria and other organisms instead of plants.

Yes, it's an evolution.

Simply, a step forward out of the artificially-induced restraints of "this is how it's always been done"- even in our own "methodology"- yet another exploration into what the natural environment is REALLY like, how it evolves, and how it works- and understanding, embracing and appreciating its aesthetics, functionality, and richness.

Earth-shattering? Not likely.

Educational? For sure.

Thought provoking and fun? Absolutely.

A simple, yet I think profound "tweak" to our approach.

Stay curious. Stay open-minded. Stay thoughtful. Stay observant. Stay creative.

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

What our fishes eat...The wonder of food webs.

Yes, I admit that we talk about some rather obscure topics around here. Yet, many of these topics are actually pretty well known, and even well-understood by science. We just haven't consciously applied them to our aquarium work...yet.

One of the topics that we talk about a lot are food webs. To me, these are fascinating, fundamental constructs which can truly have important influence on our aquariums.

So, what exactly is a food web?

A food web is defined by aquatic ecologists as a series of "trophic connections" (ie; feeding and nutritional resources in a given habitat) among various species in an aquatic community.

All food chains and webs have at least two or three of these trophic levels. Generally, there are a maximum of four trophic levels. Many consumers feed at more than one trophic level.

So, a trophic level in our case would go something like this: Leaf litter, bacteria/fungal growth, crustaceans...

In the wild aquatic habitats we love so much, food webs are vital to the organisms which live in them. They are an absolute model for ecological interdependencies and processes which encompass the relationship between the terrestrial and aquatic environments.

In many of the blackwater aquatic habitats that we're so obsessed with around here, like the Rio Negro, for example, studies by ecologists have determined that the main sources of autotrophic sources are the igapo, along with aquatic vegetation and various types of algae. (For reference, autotrophs are defined as organisms that produce complex organic compounds using carbon from simple substances, such as CO2, and using energy from light (photosynthesis) or inorganic chemical reactions.)

Hmm. examples would be phytoplankton!

Now, I was under the impression that phytoplankton was rather scarce in blackwater habitats. However, this indicates to scientists is that phytoplankton in blackwater trophic food webs might be more important than originally thought!

Now, lets get back to algae and macrophytes for a minute. Most of these life forms enter into food webs in the region in the form of...wait for it...detritus! Yup, both fine and course particular organic matter are a main source of these materials. I suppose this explains why heavy accumulations of detritus and algal growth in aquaria go hand in hand, right? Detritus is "fuel" for life forms of many kinds.

In Amazonian blackwater rivers, studies have determined that the aquatic insect abundance is rather low, with most species concentrated in leaf litter and wood debris, which are important habitats. Yet, here's how a food web looks in some blackwater habitats : Studies of blackwater fish assemblages indicated that many fishes feed primarily on burrowing midge larvae (chironomids, aka "Bloodworms" ) which feed mainly with organic matter derived from terrestrial plants!

And of course, allochtonous inputs (food items from outside of the ecosystem), like fruits, seeds, insects, and plant parts, are important food sources to many fishes. Many midwater characins consume fruits and seeds of terrestrial plants, as well as terrestrial insects.

Insects in general are really important to fishes in blackwater ecosystems. In fact, it's been concluded that the the first link in the food web during the flooding of forests is terrestrial arthropods, which provide a highly important primary food for many fishes.

These systems are so intimately tied to the surrounding terrestrial environment. Even the permanent rivers have a strong, very predictable "seasonality", which provides fruits, seeds, and other terrestrial-originated food resources for the fishes which reside in them. It's long been known by ecologists that rivers with predictable annual floods have a higher richness of fish species tied to this elevated rate of food produced by the surrounding forests.

And of course, fungal growths and bacterial biofilms are also extremely valuable as food sources for life forms at many levels, including fishes. The growth of these organisms is powered by...decomposing leaf litter!

Sounds familiar, huh?

So, how does a leaf break down? It's a multi-stage process which helps liberate its constituent compounds for use in the overall ecosystem. And one that is vital to the construction of a food web.

The first step in the process is known as leaching, in which nutrients and organic compounds, such as sugars, potassium, and amino acids dissolve into the water and move into the soil.The next phase is a form of fragmentation, in which various organisms, from termites (in the terrestrial forests) to aquatic insects and shrimps (in the flooded forests) physically break down the leaves into smaller pieces.

As the leaves become more fragmented, they provide more and more surfaces for bacteria and fungi to attach and grow upon, and more feeding opportunities for fishes!

Okay, okay, this is all very cool and hopefully, a bit interesting- but what are the implications for our aquariums? How can we apply lessons from wild aquatic habitats vis a vis food production to our tanks?

This is one of the most interesting aspects of a botanical-style aquarium: We have the opportunity to create an aquatic microcosm which provides not only unique aesthetics- it provides nutrient processing, and to some degree, a self-generating population of creatures with nutritional value for our fishes, on a more-or-less continuous basis.

Incorporating botanical materials in our aquariums for the purpose of creating the foundation for biological activity is the starting point. Leaves, seed pods, twigs and the like are not only "attachment points" for bacterial biofilms and fungal growths to colonize, they are physical location for the sequestration of the resulting detritus, which serves as a food source for many organisms, including our fishes.

Think about it this way: Every botanical, every leaf, every piece of wood, every substrate material that we utilize in our aquariums is a potential component of food production!

The initial setup of your botanical-style aquarium will rather easily accomplish the task of facilitating the growth of said biofilms and fungal growths. There isn't all that much we have to do as aquarists to facilitate this but to simply add these materials to our tanks, and allow the appearance of these organisms to happen.

You could add pure cultures of organisms such as Paramecium, Daphnia, species of copepods (like Cyclops), etc. to help "jump start" the process, and to add that "next trophic level" to your burgeoning food web.

In a perfect world, you'd allow the tank to "run in" for a few weeks, or even months if you could handle it, before adding your fishes- to really let these organisms establish themselves. And regardless of how you allow the "biome" of your tank to establish itself, don't go crazy "editing" the process by fanatically removing every trace of detritus or fragmented botanicals.

When you do that, you're removing vital "links" in the food chain, which also provide the basis for the microbiome of our aquariums, along with important nutrient processing.

So, to facilitate these aquarium food webs, we need to avoid going crazy with the siphon hose! Simple as that, really!

Yeah, the idea of embracing the production of natural food sources in our aquariums is elegant, remarkable, and really not all that surprising. They will virtually spontaneously arise in botanical-style aquariums almost as a matter of course, with us not having to do too much to facilitate it.

It's something that we as a hobby haven't really put a lot of energy in to over the years. I mean, we have spectacular prepared foods, and our understanding of our fishes' nutritional needs is better than ever.

Yet, there is something tantalizing to me about the idea of our fishes being able to supplement what we feed. In particular, fry of fishes being able to sustain themselves or supplement their diets with what is produced inside the habitat we've created in our tanks!

A true gift from Nature.

I think that we as botanical-style aquarium enthusiasts really have to get it into our heads that we are creating more than just an aesthetic display. We need to focus on the fact that we are creating functional microcosms for our fishes, complete with physical, environmental, and nutritional aspects.

Food production- supplementary or otherwise- is something that not only is possible in our tanks; it's inevitable.

I firmly believe that the idea of embracing the construction (or nurturing) of a "food web" within our aquariums goes hand-in-hand with the concept of the botanical-style aquarium. With the abundance of leaves and other botanical materials to "fuel" the fungal and microbial growth readily available, and the attentive husbandry and intellectual curiosity of the typical "tinter", the practical execution of such a concept is not too difficult to create.

We are truly positioned well to explore and further develop the concept of a "food web" in our own systems, and the potential benefits are enticing!

Work the web- in your own aquarium!

Stay curious. Stay observant. Stay creative. Stay diligent. Stay open-minded...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

The natural "intangibles" of botanical materials

Even with the exploding popularity of botanical-style aquariums, I still receive many questions from hobbyists unfamiliar with our practice, asking what the purpose or benefit is of utilizing these materials in our tanks. I find myself repeating the mantra that this is not purely an aesthetic statement.

Utilizing natural botanical materials in our aquariums is not an aquascaping style; rather, it's a methodology for creating and managing a biologically diverse closed aquatic ecosystem.

There is also something very different about the way that our fishes behave when they are living in an environment which has an abundance of natural materials present.

I know, it sounds a bit weird, but it's true! We receive lots of comments about this. It's sort of an "intangible" that comes with using them in our tanks. And I suppose it makes a lot of sense, as the fishes are utilizing them much as they do in their wild habitats, for shelter, grazing, and spawning.

Now sure, in a tank devoid of natural materials like botanicals, fishes will utilize whatever materials are available to shelter among, graze, and even spawn (hello, "spawning cones" and cracked flower pots!). Yet, there is a certain "something" that's different when you use botanicals. You can just see it.

Of course, with botanical materials, you have the added benefit that they are natural materials, consisting of substances like lignin, and they can impart other compounds stored in their tissues, such as tannin and humic substances, into the surrounding water column. And many fishes feed directly on the botanicals themselves, or remove "biocover" from their surfaces.

Yeah, think about it:

The texture and chemical composition of the botanicals' exteriors is really well-suited for the recruitment and growth of biofilms and fungal populations- important for the biological diversity and "operating system" of the aquarium, as we've talked about numerous times here. This is such an easily overlooked benefit of using natural materials in the aquarium.

And of course, as we know, terrestrial botanical materials, when submerged in water for extended periods of time, decompose. If there is one aspect of our botanical-style aquariums which fascinates me above almost anything else, it's the way they facilitate the natural processes of life- specifically, decomposition.

Decomposition is fundamental to the botanical style aquarium.

We use this term a lot around here...What, precisely does it mean?

de·com·po·si·tion- dēˌkämpəˈziSH(ə)n -the process by which organic substances are broken down into simpler organic matter.

A very apt descriptor, if you ask me!

We add leaves and botanicals to our aquariums, and over time, they start to soften, break up, and ultimately, decompose. Decomposition of leaves and botanicals not only liberates the substances contained within them (lignin, organic acids, and tannins, just to name a few) into the water- it serves to nourish bacteria, fungi, and other microorganisms and crustaceans, facilitating basic "food web" within the botanical-style aquarium, just like it does in Nature- if we allow it to!

PVC pipe sections, flower pots, and plastic plants can't do THAT!

Utilizing botanical materials and leaves in your tank, and leaving them in until they fully decompose is as much about your aesthetic preferences as it is long-term health of the aquarium.

It's a decision that each of us makes based on our tastes, management "style", and how much of a "mental shift" we've made into accepting the transient nature of materials in a botanical-style aquarium and its function. There really is no "right" or "wrong" answer here. It's all about how much you enjoy what happens in Nature versus what you can control in your tank. Nature will utilize them completely, as she does in the wild.

I tend to favor Nature, of course. But that's just me.

And of course, we can't ever lose sight of the fact that we're creating and adding to a closed aquatic ecosystem, and that our actions in how we manage our tanks must map to our ambitions, tastes, and the "regulations" that Nature imposes upon us.

Yes, anything that you add into your aquarium that begins to break down is bioload.

Everything that imparts proteins, organics, etc. into the water is something that you need to consider. However, it's always been my personal experience and opinion that, in an otherwise well-maintained aquarium, with regular attention to husbandry, stocking, and maintenance, the "burden" of botanicals in your water is surprisingly insignificant.

Even in test systems, where I intentionally "neglected" them by conducting sporadic water exchanges, once I hit my preferred "population" of botanicals (by buying them up gradually), I have never noticed significant phosphate or nitrate increases that could be attributed to their presence.

Understand that the process of decomposition is a fundamental, necessary function that occurs in our aquariums on a constant basis, and that botanicals are the "fuel" which drives this process. Realize that in the botanical-style aquarium, we are, on many levels, attempting to replicate the function of natural habitats- and botanical materials are just part of the equation.

And of course, these botanical materials not only offer unique natural aesthetics- they offer enrichment of the aquatic habitat through their release of tannins, humic acids, vitamins, etc. as they decompose- just as they do in Nature.

Leaves and such are simply not permanent additions to our 'scapes, and if we wish to enjoy them in their more "intact" forms, we will need to replace them as they start to break down. This is not a bad thing. It just requires us to "do some stuff" if we are expecting a specific aesthetic.

This is very much replicates the process which occur in Nature, doesn't it? Stuff like seed pods and leaves either remains "in situ" as part of the local habitat, or is pushed downstream by wind, current, etc. - and new materials continuously fall into the waters to replace the old ones.

Pretty much everything we do in a botanical-style blackwater aquarium has a "natural analog" to it!

Despite their impermanence, these materials function as diverse harbors of life, ranging from fungal and biofilm mats, to algae, to micro crustaceans and even epiphytic plants. Decomposing leaves, seed pods, and tree branches make up the substrate for a complex web of life which helps the fishes that we're so fascinated by flourish.

Intangibles? Perhaps. Yet, highly beneficial and consequential ones, indeed.

Stay persistent. Stay bold. Stay consistent. Stay observant...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Stuff we've been told to fear...

A couple of days back, I was chatting with a fellow hobbyist who wanted to jump in to something a bit different within the aquarium hobby, but was afraid of the possible consequences-both socially and in his aquariums. He feared criticism from "them", and that just froze him. I felt bad that he was so afraid of criticism from others should he question the "status quo" within the hobby.

Perhaps my story might be helpful to you if you're afraid of such criticisms.

For generations, we've been told in the aquarium hobby that we need to be concerned about the appearance of all kinds of stuff in our tanks, like algae, detritus, and "biocover".

For some strange reason, we as a hobby group seems emphasize stuff like understanding some biological processes, like the nitrogen cycle, yet we've also been told to devote a lot of resources to siphoning, polishing, and scrubbing our tanks to near sterility.

It's a strange dichotomy.

I remember the first few botanical-style tanks I created, almost two decades ago now, would hit that phase early on when biofilms and fungal growths began to appear, and I'd hear my friends telling me, "Yeah, your tank is going to turn into a big pile of shit. Told you that you can't put that stuff in there."

Because that's what they've been told. The prevailing mindset in the hobby was that the appearance of these organisms was an indication of an unsuitable aquarium environment.

Anyone who's studied basic ecology and biology understands that the complete opposite is true. The appearance of these valuable life forms is an indicator that your aquatic environment is ideal to foster a healthy, diverse community of aquatic organisms, including fishes!

Exactly like in Nature.

I remember telling myself that this is what I knew was going to happen. I knew how biofilms and fungal growths appear on "undefended" surfaces, and that they are essentially harmless life forms, exploiting a favorable environment. I knew that fungi appear as they help break down leaves and botanicals. I knew that these are perfectly natural occurrences, and that they typically are transitory and self-limiting to some extent.

Normal for this type of aquarium approach. I knew that they would go away, but I also knew that there would be a period of time when the tank might look like a big pool of slimy shit. Or, rather, it'd look like a pile of slimy shit to those who weren't familiar with these life forms, how they grow, and how the natural aquatic habitats we love so much actually function and appear!

To reassure myself, I would stare for hours at underwater photos taken in the Amazon region, showing decaying leaves, biofilms,and fungi all over the leaf litter. I'd read the studies by researchers like Henderson and Walker, detailing the dynamics of leaf litter zones and how productive and unique they were.

I'd pour over my water quality tests, confirming for myself that everything was okay. It always was. And of course I would watch my fishes for any signs of distress...

I never saw them.

I knew that there wouldn't be any issues, because I created my aquariums with a solid embrace of basic aquatic biology; an understanding that an aquarium is not some sort of underwater art installation, but rather, a living, breathing microcosm of organisms which work together to create a biome..and that the appearance of the aquarium only tells a small part of the story.

I knew that this type of aquatic habitat could be replicated in the aquarium successfully. I realized that it would take understanding, trial and error, and acceptance that the aquariums I created would look fundamentally different than anything I had experienced before.

I knew I might face criticism, scrutiny, and even downright condemnation from some quarters for daring to do something different, and then for labeling what most found totally distasteful, or have been conditioned by "the hobby" for generations to fear, as simply "a routine part of the process."

It's what happens when you venture out into areas of the hobby which are a bit untested. Areas which embrace ideas, aesthetics, practices, and occurrences which have existed far out of the mainstream consciousness of the hobby for so long. Fears develop, naysayers emerge, and warnings are given.

Yet, all of this stuff- ALL of it- is completely normal, well understood and documented by science, and in reality, comprises the aquatic habitats which are so successful and beneficial for fishes in both Nature and the aquarium. We as a hobby have made scant little effort over the years to understand it. And once you commit yourself to studying, understanding, and embracing life on all levels, the world of natural, botanical-style aquariums and its untapped potential opens upon to you.

Mental shifts are required. Along with study, patience, time, and a willingness to look beyond hobby forums, aquarium literature, and aquascaping contests for information. A desire to roll up your sleeves, get in there, ignore the naysayers, and just DO.

Don't be afraid of things because they look different, or somehow contrary to what you've heard or been told by others is "not healthy" or somehow "dangerous." Now sure, you can't obey natural "laws" like the nitrogen cycle, understanding pH, etc.

You can, however, question things you've been told to avoid based on superficial explanations based upon aesthetics.

Mental shifts.

Stuff that makes you want to understand how life forms such as fungi, for example, arise, multiply, snd contribute to the biome of your aquarium.

Let's think about fungi for a minute...a "poster child" for the new way of embracing Nature as it is.

Fungi reproduce by releasing tiny spores that then germinate on new and hospitable surfaces (ie, pretty much anywhere they damn well please!). These aquatic fungi are involved in the decay of wood and leafy material. And of course, when you submerge terrestrial materials in water, growths of fungi tend to arise. Anyone who's ever "cured" a piece of wood for your aquarium can attest to this!

Fungi tend to colonize wood because it offers them a lot of surface area to thrive and live out their life cycle. And cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, the major components of wood and botanical materials, are degraded by fungi which posses enzymes that can digest these materials! Fungi are regarded by biologists to be the dominant organisms associated with decaying leaves in streams, so this gives you some idea as to why we see them in our aquariums, right?

And of course, fishes and invertebrates which live amongst and feed directly upon the fungi and decomposing leaves and botanicals contribute to the breakdown of these materials as well! Aquatic fungi can break down the leaf matrix and make the energy available to feeding animals in these habitats. And look at this little gem I found in my research:

"There is evidence that detritivores selectively feed on conditioned leaves, i.e. those previously colonized by fungi (Suberkropp, 1992; Graca, 1993). Fungi can alter the food quality and palatability of leaf detritus, aecting shredder growth rates. Animals that feed on a diet rich in fungi have higher growth rates and fecundity than those fed on poorly colonized leaves. Some shredders prefer to feed on leaves that are colonized by fungi, whereas others consume fungal mycelium selectively..."

"Conditioned" leaves, in this context, are those which have been previously colonized by fungi! They make the energy within the leaves and botanicals more available to higher organisms like fishes and invertebrates!

The aquatic fungi which will typically decompose leaf litter and wood are the group known as “aquatic hyphomycetes”. Another group of specialists, "aero-aquatic hyphomycetes," colonize submerged plant detritus in stagnant and slow- flowing waters, like shallow ponds, puddles, and flooded forest areas. Fungal communities differ between various environments, such as streams, shallow lakes and wetlands, deep lakes, and other habitats such as salt lakes and estuaries.

And we see them in our own tanks all the time, don't we? Sure, it's easy to get scared by this stuff...and surprisingly, it's even easier to exploit it as a food source for your animals! We just have to make that mental shift... As the expression goes, "when life gives you lemons, make lemonade!"

I knew when I started Tannin that I had to "walk the walk." I had to explain by showing my tanks, my work, and giving fellow hobbyists the information, advice, and support they needed in order to confidently set out on their own foray into this interesting hobby path.

I'm no hero. Not trying to portray myself as a visionary.

The point of sharing my personal experience is to show you that trying new stuff in the hobby does carry risk, fear, and challenge, but that you can and will persevere if you believe. If you push through. IF you don't fear setbacks, issues, criticisms from naysayers.

You have to try. In my case, the the idea of throwing various botanical items into aquariums is not my invention. It's not a totally new thing. People have done what I've done before. Maybe not as obsessively or thoroughly presented (and maybe they haven't built a business around the idea!), but it's been done many, many times.

The fact is, we can and should all take these kinds of journeys.

Stay the course. Don't be afraid. Open your mind. Study what is happening. Draw parallels to the natural aquatic ecosystems of the world. Look at this "evolution" process with wonder, awe, and courage.

And know that the pile of decomposing leaves, fungal growth, and detritus that you're looking at now is just a steppingstone on the journey to an aquarium which embrace nature in every conceivable way.

Stay brave. Stay curious. Stay diligent. Stay observant...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

No expiration date.

We talk a lot about starting up and managing botanical-style aquariums. We have had numerous discussions about set up and the accompanying expectations of the early days in the life of the little ecosystems we've created. However, what about the long term..The really long term?

Like, how long can you maintain one of these aquariums?

Do they have an "expiration date? A point when the system no longer "grows" or thrives?

There is a term, sometimes used to describe the state of very old aquariums- "senescence." The definition is: "...the condition or process of deterioration with age." Well, that doesn't sound all that unusual, right? I mean, stuff ages, gets old, stops functioning well, and eventually expires...aquariums are no different, right?

Well, I don't think so.

Sometimes, this deterioration is referred to in the hobby by the charming name of "Old Tank Syndrome"

Now, on the surface, this makes some sense, right? I mean, if your tank has been set up for several years, environmental conditions will change over time. Among the many phenomenon brought up by proponents of this theory is the increase in nitrate levels. People who buy into "OTS" will tell you that nitrate levels will increase over time.

They'll tell you that phosphate, which typically comes into our tanks with food, will accumulate, resulting in excessive, perhaps rampant, algal growths. You know, the kind from which aquarium horror stories are made.

They will tell you that the pH of the aquarium will decline as a result of accumulating nitrate, with hydrogen ions utilizing all available buffers, resulting in a reduction of the pH below 6 (like, IS that a problem?), which supposedly results in the beneficial bacteria ceasing to convert ammonia into nitrite and nitrate and creating a buildup of toxic ammonia...

I mean, it's absolutely possible. We've talked about the potential cessation of the nitrogen cycle as we know it at low pH levels, and about the archaens which take over at these low pH levels. (That's a different "thing", though, and off topic ATM)

Of course, all of the bad things espoused by the OTS theorists can and will happen...If you never do any tank maintenance. If you simply abandon the idea of water exchanges, continue stocking and feeding your aquarium recklessly, and essentially abandon the basic tenants of aquarium husbandry.

The problem with this theory is that it assumes all aquarists are knuckleheads, refusing to perform water exchanges, while merrily going about their business of watching the pretty fishes swim. It seems to forecast some sort of inevitability that this will happen to every tank.

No way. Uh-uh. I call B.S. on this.

As someone who has kept all sorts of tanks (reef tanks, freshwater fish-only tanks, etc.) in operation for many years (my longest was 13 years, and botanical-style tanks going on 5 plus years), I can't buy into this idea. I mean, sure, if you don't set up a system properly in the first place, and then simply become lackadaisical about husbandry, of course your tank can decline.

But, here's the thing: It's not inevitable.

RULE OF THUMB: Do fucking maintenance, feed carefully, and don't overstock. This is not "rocket science!"

Rather than "Old Tank Syndrome"- a name which seems to imply that it's not our fault, and that it's like some unfortunate, random occurrence which befalls the unsuspecting-we should call it LAAP- "Lazy Ass Aquarists' Payback."

'Cause that's what it IS. It's entirely the fault of a lazy-ass aquarist. Preventable and avoidable.

Need more convincing that it's not some random "malady" that can strike any tank? That it's some "universal constant" which commonly occurs in all aquariums?

Think about the wild habitats which we attempt to model our aquariums after. Do these habitats decline over time for no reason? Generally, no. They will respond to environmental changes, like drought, pollution, sedimentation, etc. They will react to these environmental pressures or insults. They will evolve over time.

Now, sure, seasonal desiccation and such result in radical environmental shifts in the the aquatic environment and a definite "expiration date"- but you seldom hear of aquatic habitats declining and disappearing or becoming otherwise uninhabitable to fishes without some significant (often human-imposed) external pressures- like pollution, ash from fires or volcanoes, deliberate diversion or draining of the water source (think "Rio Xingu"), logging operations, climate change, etc.

Of course, our aquariums are closed ecosystems. However, the same natural laws which govern the nitrogen cycle or other aspects of the system's ecology in Nature apply to our aquariums. The big difference is that our tanks are almost completely dependent upon us as aquarists applying techniques which replicate some of the factors and processes which apply in Nature. Stuff like water exchanges, etc.

So if we keep up the nutrient export processes, don't radically overstock our systems, feed appropriately, maintain filters, and observe them over time, there is no reason why we couldn't maintain our aquariums indefinitely.

There is no "expiration date."

And the cool thing about botanical-style aquariums is that part of our very "technique" from day one is to facilitate the growth and reproduction of beneficial microfauna, like bacteria, fungal growths, etc., and to allow decomposition to occur to provide them feeding opportunities.What this does is help create a microbiome of organisms which, as we've said repeatedly, form the basis of the "operating system" of our tanks.

Each one of these life forms supporting, to some extent, those above...including our fishes.

So, yeah- botanical-style aquariums are "built" for the long run. Provided that we do our fair share of the work to support their ecology. Just because we add a lot of botanical material, allow decomposition, and tend to look on the resulting detritus favorably doesn't mean that these are "set-and-forget" systems, any more than it means they're particularly susceptible to all of the problems we discussed previously.

Common sense husbandry and observation are huge components of the botanical-style aquarium "equation."

As part of our regular husbandry routine, we keep the ecosystem "stocked" with fresh botanicals and leaves on a continuous basis, to replenish those which break down via decomposition. This is perfectly analogous to the processes of leaf drop and the influx of allochthonous materials from the surrounding terrestrial habitat which occur constantly in the wild aquatic habitats which we attempt to replicate.

We favor a "biology/ecology first" mindset.

Replenishing the botanical materials provides surface area and food for the numerous small organisms which support our systems. It also provides supplemental food for our fishes, as we've discussed previously. It helps recreate, on a very real level, the "food webs" which support the ecology of all aquatic ecosystems.

And it sets up botanical-style aquariums to be sustainable indefinitely.

Radical moves and "Spring Cleanings" are not only unnecessary, IMHO- they are potentially disruptive and counter-productive. Rather, it's about deliberate moves early on, to facilitate the emergence of this biome, and then steady, regular replenishment of botanical materials to nourish and sustain the ecosystem.

My belief is steeped in the mindset that you've created a little ecosystem, and that, if you start removing a significant source of someone's food (or for that matter, their home!), there is bound to be a net loss of biota...and this could lead to a disruption of the very biological processes that we aim to foster.

Okay, it's a theory...But I think I might be on to something, maybe? So, like here is my theory in more detail:

Simply look at the botanical-style aquarium (like any aquarium, of course) as a little "microcosm", with processes and life forms dependent upon each other for food, shelter, and other aspects of their existence. And, I really believe that the environment of this type of aquarium, because it relies on botanical materials (leaves, seed pods, etc.), is significantly influenced by the amount and composition of said material to "operate" successfully over time.

No expiration date.

Personally, I don't think that botanical-style aquariums are ever "finished", BTW. They simply continue to evolve over extended periods of time, just like the wild habitats that we attempt to replicate in our tanks do.

The continuous change, development, and evolution of aquatic habitats is a fascinating, compelling area to study- and to replicate in our aquaria. I'm convinced more than ever that the secrets that we learn by fostering and accepting Nature's processes and dynamics are the absolute key to everything that we do in the aquarium.

The idea that your aquarium environment simply deteriorates as a result of its very existence is, in my humble opinion, wrong, narrow-minded, and outdated thinking. (Other than that, it's completely correct!😆).

Seriously, though...

"Old Tank Syndrome" is a crock of shit, IMHO.

Aquariums only have an "expiration date" if we don't take care of them. Period. No more sugar coating this.

If we look at them assume sort of "static diorama" thing, requiring no real care, they definitely have an "expiration date"; a point where they are no longer sustainable. When we consider our aquariums to be tiny, closed ecosystems, subject to the same "rules" which govern the natural environments which we seek to replicate, the parallels are obvious. The possibilities open up. And the potential to unlock new techniques, ideas, and benefits for our fishes is very real and truly exciting!

I'm not entirely certain how this approach to aquariums, and this idea of fostering a microbiome within our tank and caring for it has become a sort of "revolutionary" or "counter-culture" sort of thing in the hobby, as many fellow hobbyists have told me that they feel it is.

Label it what you want, I think that, if we make the effort to understand the function of our tanks as much as we do the appearance, then it all starts making sense. If you look at an aquarium as you would a garden- an organic, living, evolving, growing entity- one which requires a bit of care on our part in order to thrive-then the idea of an "expiration date" or inevitable decline of the system becomes much less logical.

Rather, it's a continuous and indefinite process.

No "end point."

Much like a "road trip", the "destination" becomes less important than the journey. It's about the experiences gleaned along the way. Enjoyment of the developments, the process. In the botanical-style aquarium, it's truly about a dynamic and ever-changing system. Every stage holds fascination.

Continuously.

An aquatic display is not a static entity, and will continue to encompass life, death, and everything in between for as long as it's in existence. There is no expiration date for our aquariums, unless we select one.

Take great comfort in that simple truth.

Stay grateful. Stay enthralled. Stay observant. Stay patient. Stay dedicated...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

It's about the microbiome...

As we've all started to figure out by now, our botanical-influenced aquariums are a lot more of a little slice of Nature that you're recreating in your home then they are just a "pet-holding container."

The botanical-style aquarium is a microcosm which depends upon botanical materials to impact the environment.

This microcosm consists of a myriad of life format all levels and all sizes, ranging from our fishes, to small crustaceans, worms, and countless microorganisms. These little guys, the bacteria and Paramecium and the like, comprise what is known as the "microbiome" of our aquariums.

A "microbiome", by definition, is defined as "...a community of microorganisms (such as bacteria, fungi, and viruses) that inhabit a particular environment." (according to Merriam-Webster)

Now, sure, every aquarium has a microbiome to a certain extent:

We have the beneficial bacteria which facilitate the nitrogen cycle, and play an indespensible role in the function of our little worlds. The botanical-style aquarium is no different; in fact, this is where I start wondering...It's the place where my basic high school and college elective-course biology falls away, and you get into more complex aspects of aquatic ecology in aquariums.

Yet, it's important to at least understand this concept as it can relate to aquariums. It's worth doing a bit of research and pondering. It'll educate you, challenge you, and make you a better overall aquarist. In this little blog, we can't possibly cover every aspect of this- but we can touch on a few broad points that are really fascinating and impactful.

So much of this proces-and our understanding starts with...botanicals.

With botanicals breaking down in the aquarium as a result of the growth of fungi and microorganisms, I can't help but wonder if they perform, to some extent, a role in the management-or enhancement-of the nitrogen cycle.

Yeah, you understand the nitrogen cycle, right?

How do botanicals impact this process? Or, more specifically, the microorganisms that they serve?

In other words, does having a bunch of leaves and other botanical materials in the aquarium foster a larger population of these valuable organisms, capable of processing organics- thus creating a more stable, robust biological filtration capacity in the aquarium?

I believe that they do.

With a matrix of materials present, do the bacteria (and their biofilms- as we've discussed a number of times here) have not only a "substrate" upon which to attach and colonize, but an "on board" food source which they can utilize as needed?

Facultative bacteria, adaptable organisms which can use either dissolved oxygen or oxygen obtained from food materials such as sulfate or nitrate ions, would also be capable of switching to fermentationor anaerobic respiration if oxygen is absent.

Hmm...fermentation.

Well, that's likely another topic for another time. Let's focus on some of the other more "practical" aspects of this "biome" thing.

Like...food production for our fishes.

In the case of our fave aquatic habitats, like streams, ponds, and inundated forests, epiphytes, like biofilms and fungal mats are abundant, and many fishes will spend large amounts of time foraging the "biocover" on tree trunks, branches, leaves, and other botanical materials.

The biocover consists of stuff like algae, biofilms, and fungi. It provides sustenance for a large number of fishes all types.

And of course, what happens in Nature also happens the aquarium- if we allow it to, right? And it can function in much the same way?

Yeah.

I am of the opinion that a botanical-style aquarium, complete with its decomposing leaves and seed pods, can serve as a sort of "buffet" for many fishes- even those who's primary food sources are known to be things like insects and worms and such. Detritus and the microorganisms within it can provide an excellent supplemental food source for our fishes!

Sustenence...from the microbiome.

It's well known that in many habitats, like inundated forests, etc., fishes will adjust their feeding strategies to utilize the available food sources at different times of the year, such as the "dry season", etc.

And it's also known that many fish fry feed actively on bacteria and fungi in these habitats...So I suggest once again that a botanical-style aquarium could be an excellent sort of "nursery" for many fish and shrimp species!

Again, it's that idea about the "functional aesthetics" of the, botanical-style aquariums. The idea which acknowledges the fact that the botanicals we use not only look cool, but they provide an important function (supplemental food production) as well. As we repeat constantly, the "look" is a collateral benefit of the function.

This is a profoundly important idea.

Perhaps arcane to some- but certainly not insignificant.

And of course, we've talked before about this "botanical nursery" concept- creating an aquarium for fish fry that has a large quantity of decomposing botanicals and leaves to foster the production of these materials, which serve as supplemental food for your fish fry. I have done this before myself and can attest to its viability. You fishes will have a constant supply of "natural" foods to supplement what you are feeding them in the early phases of their life.

Learn to make peace with your detritus! As always, look to the wild aquatic habitats of the world for an example of how this food source functions within the greater biome.

I'm fascinated by the "mental adjustments" that we need to make to accept the aesthetic and the processes of natural decay, fungal growth, the appearance of biofilms, and how these affect what's occurring in the aquarium. It's all a complex synergy of life and aesthetic.

And, in order to make the mental shifts which make this all work, we we have to accept Nature's input here.

Understand that, when we create a botanical-filled aquarium, not only do we have the opportunity to create an aquarium which differs significantly from those in years past- we have a unique window into the natural world and the role of these materials in the wild.

One thing that's very unique about the botanical-style approach is that we tend to accept the idea of decomposing materials accumulating in our systems. We understand that they act, to a certain extent, as "fuel" for the micro and macrofauna which reside in the aquarium, and that they perform this function as long as they are present in the system.

A profound mental shift...

And it's all about the microbiome. today's simple idea with enormous impact!

Stay curious. Stay thoughtful. Stay observant. Stay diligent...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

The Bloom.

It's not magic...It's Nature.

As anyone who ventures down our tinted road knows, one of the great "inevitable" of utilizing botanicals in our aquariums is the appearance of biofilms. You know, those scuzzy, nasty-looking threads of goo, which make their appearance in our tanks shortly after immersion of the botanicals (much to the chagrin of many).

Biofilm.

Even the word conjures up an image of something that you really don't want in your tank. Something dirty, yucky...potentially detrimental to your aquarium's health.

It's not.

However, let's be honest with ourselves here. The damn dictionary definition is not gonna win over many "haters":

We've long maintained that the appearance of biofilms and fungi on your botanicals and wood are to be celebrated- not feared. They represent a burgeoning emergence of life -albeit in one of its lowest and most unpleasant-looking forms- and that's a really big deal.

Biofilms form when bacteria adhere to surfaces in some form of watery environment and begin to excrete a slimy, gluelike substance, consisting of sugars and other substances, that can stick to all kinds of materials, such as- well- in our case, botanicals. It starts with a few bacteria, taking advantage of the abundant and comfy surface area that leaves, seed pods, and even driftwood offer.

The "early adapters" put out the "welcome mat" for other bacteria by providing more diverse adhesion sites, such as a matrix of sugars that holds the biofilm together. Since some bacteria species are incapable of attaching to a surface on their own, they often anchor themselves to the matrix or directly to their friends who arrived at the party first.

Tannin's creative Director, Johnny Ciotti, calls this period of time when the biofilms emerge, and your tank starts coming alive "The Bloom"- a most appropriate term, and one that conjures up a beautiful image of Nature unfolding in our aquariums- your miniature aquatic ecosystem blossoming before your very eyes!

The real positive takeaway here: Biofilms are really a sign that things are working right in your aquarium! A visual indicator that natural processes are at work, helping forge your tank's ecosystem.

I recently had a discussion with our friend, Alex Franqui (the guy who designs our cool enamel pins). His beautiful Igarape-themed aquairum pictured above, is starting to "bloom", with the biofilms and sediments working together to create a stunning, very natural look. Alex is a hardcore aquascaper, and to see him marveling and rejoicing in the "bloom" of biofilms in his tank is remarkable.

He gets it.

And it turns out that our love of biofilms is truly shared by some people who really appreciate them as food...Shrimp hobbyists! Yup, these people (you know who you are!) go out of their way to cultivate and embrace biofilms and fungi as a food source for their shrimp.

They get it.

And this makes perfect sense, because they are abundant in Nature, particularly in habitats where shrimp naturally occur, which are typically filled with botanical materials, fallen tree trunks, and decomposing leaves...a perfect haunt for biofilm and fungal growth!

Nature celebrates "The Bloom", too.

There is something truly remarkable about natural processes playing out in our own aquariums, as they have done for eons in the wild.

Remember, it's all part of the game with a botanical-influenced aquarium. Understanding, accepting, and celebrating "The Bloom" is all part of that "mental shift" towards accepting and appreciating a more truly natural-looking, natural-functioning aquarium. The "price of admission", if you will- along with the tinted water, decomposing leaves, etc., the metaphorical "dues" you pay, which ultimately go hand-in-hand with the envious "ohhs and ahhs" of other hobbyists who admire your completed aquarium when they see it for the first time.

.

The reality to us as "armchair biologists" is that the presence of these organisms in our aquariums is beautiful to us for so many reasons. It's not only a sign that our closed microcosms are functioning well, but that they are, in their own way, providing for the well- being of the inhabitants!

An abundance, created by "The Bloom."

The "mental stretches" that we ask you to make to accept these organisms and their appearance really require us to look at the wild habitats from which our fishes come, and reconcile that with our century-old aquarium hobby idealization of what Nature (and therefore our "natural" aquariums) actually look like.

Sure, it's not an easy stretch for most.

It's likely not everyone's idea of "attractive", and you'd no doubt freak out snobby contest judges with a tank full of biofilms and fungi, but to most of us, we should take great delight in knowing that we are providing our fishes with an extremely natural component of their ecosystem, the benefits of which have never really been studied in the aquarium in depth.

Why? Well, because we've been too busy looking for ways to remove the stuff instead of watching our fishes feed on it, and our aquatic environments benefit from its appearance!

We've had it all wrong, IMHO.

It's okay, we're starting to come around...

Welcome to Planet Earth.

Yet, there are always those doubts...and some are not willing to sit by and watch the "slime" take over...despite the fact that we know it's okay...

Celebrate "The Bloom."

Blurring the lines between Nature and the aquarium, from an aesthetic sense, at the very least- and in many respects, from a "functional" sense as well, proves just how far hobbyists have come...how good you are at what you do. And... how much more you can do when you turn to nature as an inspiration, and embrace it for what it is.