- Continue Shopping

- Your Cart is Empty

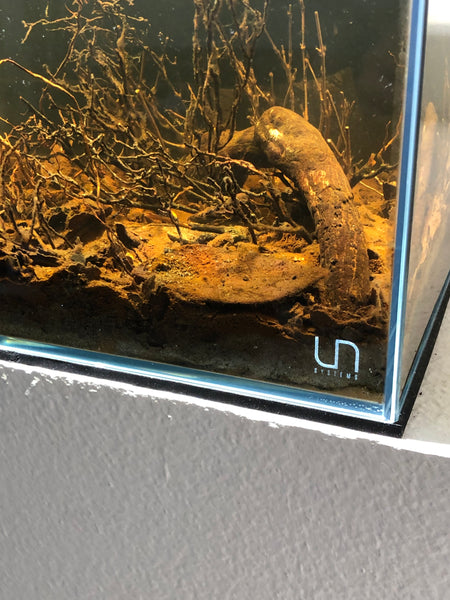

Hell? Or high water? Questions and answers on "The Urban Igapo" Concept...

Q- Hey Scott, LOVE the "Urban Igapo" idea, and have been doing a few of my own. Question, though, which I think about a lot...When do you know it's time to add water? Do you add it all at one time, or gradually? Thanks for all you do! -Rex

A- Thanks for the kind words, Rex! So, here's the deal: There is no real exact optimum time to flood your "igapo" or "varzea" setup. I suppose, if pressed, I'd tell you a good time is when the grassland terrestrial plants are growing at their strongest, with fairly dense coverage over the substrate, and when any terrestrial plants you've added are showing good growth.

If you want to mimic a natural cycle, you could do a bit of research on actual weather patterns in your target area..For example, The wet season in The Amazon runs from November to June. And it rains almost every day. So, you could add a little water every day, starting in November, and continuing on from there, right?

With grasses, like our beloved Paspalum, I wait until I have a pretty dense "carpet of the stuff, because it tends to fare better when submerged if it's growing strongly before I add the water.

I tend to add the water over the course of a few days (like 3-4), before reaching the desired depth. For whatever reason, I've found over the years that the grass tends to hang on longer under inundation when you add the water gradually. Maybe it gives the grass some time to "acclimate"; maybe it's just in my head, lol!

Q- Hi Scott! Having fun with the "igapo" thing, and loving "NatureBase!" Question for ya: How ya'll filter your tanks after you flood them? Can you get along without one? Curious! -Bridgett

A- Good one, Bridgett! Most of my "Urban Igapo" tanks tend to be smaller, "nano-sized" affairs, 5 U.S. gallons or less. The options are to use a small hang-on power filter, a sponge filter, or...wait for it...NO FILTER!

Think about it: We have a tank filled with rich soil, good grass or marginal plant growth (like my fave, Acorus), and typically in good light. It's entirely possible to manage the system without filtration. Depending upon the fishes you will add to the tank, it's not usually a problem. For example, I tend to play with a lot of annual or bottom-spawning killiefish in my "Urban Igapo" systems. These guys are traditionally kept, bred, and reared in small tanks, bowls, or other containers, without filtration. They're perfect for this sort of thing.

Of course, you can keep other fishes, like Anabantids, which can be kept similarly (albeit in slightly warmer water), or even small characins, which also can do just fine in tanks with no filters for periods of time.

The key is to conduct regular water exchanges, don't overstock, and feed carefully.

Now, one caveat about filters in smaller "igapo" tanks: Because we tend to use sediment snd soil-based substrates, which can blow around a bit, be careful where you direct return flow, and how strong the return might be. Otherwise, you end up with a constantly turbid display, which might be annoying to some of you!

Q- Hey Scott. Really love the whole "flooded forest" idea, but I'm not sure if I want to do the whole "cycle" thing. Is it hard? And can I run mine differently?- Ray

Hello, Ray. Of course you can do it differently! There area lot of ideas to play with.

Now, it's been incredibly fun for me, sort of attempting to simulate some of the processes which happen seasonally in Nature. With the technology, materials, and information available to us today, the capability of creating a true "year-round" habitat simulation in the confines of an aquarium/vivarium setup has never been more attainable.

Now, that's all well-and-good. We've kind of figured out how this wet-and-dry cycle can be managed in these types of systems. We're starting to really get this thing down, and it's easily replicated by the patient aquarist. We have a lot of blog posts and podcasts about the process, and we've even developed a line of substrates just for these types of systems!

However, let's think about simulating the "inundation season" as the aquarium. Let's assume that you're kind of not into doing the whole "start with a dry habitat, plant some grasses and terrestrial plants, and gradually inundate it with water, then gradually dry it out again" thing that is the crux "Urban Igapo" idea.

You want to do things bait different. That's okay... There are lot of interesting possibilities for you.

By regularly wetting these materials- the substrate, leaves, botanicals, and wood- down for a few days, and letting them saturate, it's entirely possible to go from "terrestrial" to "aquatic" in a very short period of time, and getting the cool effect- and indeed, part the function (a burst of microbial life, biofilms, fungal growths, and release of tannin and humic substances) of this system from the start.

At the risk of sounding crassly commercial, I'd recommend some sort of bacterial inoculant, such as our spray- on Purple Non-Sulphur Bacteria inoculant, "Nurture".-to "kick start" the biological processes in your system before it's inundated with water.

I think that this step of "bacterial inoculation" is such a fundamental part of the botanical-style aquarium approach. I see it as much less of a "hack" to kick-start the nitritogen cycle (it will help do that...) and more of a way to provide an initial population of life forms which help assimilate some of the botanical materials and make the many organic (and other) compounds and substances locked in their tissues (tannins, humic substances, lignin, sugars, etc.) available to other life forms within the evolving microcosm you're creating.

So, yeah...I got a bit carried away there, but you CAN take some different approaches to this stuff...It's all very "ground floor",with lotto learn and do!

I hope that these selections from our email will answer some of your questions on this fun and exciting new way to run a unique and dynamic aquarium!

Stay excited. Stay creative. Stay observant. Stay bold...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

The contrarian embrace of decomposing stuff in our tanks..

The world of botanical style aquariums is exploding.

Someone asked me recently about how I feel about having botanicals completely beak down in my aquarium. As in, just leaving them in until they're essentially inert.

My responses it has been for years, is that I'm perfectly fine with just leaving them in! The reality, as I see it, is that there is simply nothing wrong with this. I know, I know-it sort of goes against many years of aquarium hobby doctrine, which suggests that it's a bad idea to allow materials to decompose in your tank.

Now, of course, this is not bad advice, in general. We've been admonished to remove stuff like uneaten food, fish poop, dead plant leaves, deceased fishes, etc. from our tanks. The rationale, for years, has been that the breakdown of organic materials can lower the pH of the aquarium water by releasing carbon dioxide, which is converted to carbonic acid in water. This carbonic acid, in turn, can rapidly drop the pH, and...

Okay...

Of course, in addition to the potential to drop the pH of your tank quickly, the decomposition of stuff like uneaten food has historically been implicated in the clogging of filter media, reducing flow through the aquarium, which, in theory, may result in a lower dissolved oxygen content, a drop in pH, a rise in ammonia and nitrite levels...you know, the usual bad stuff.

So, is there any difference between uneaten fish food and allowing your botanical materials to break down fully in situ?

Well, not necessarily. The process is the process, right?

Sure.

Of course, fish foods are high in compounds like phosphate, which can lead to excessive algae growth if left unchecked. So, yeah, you HAVE to embrace basic husbandry (like water exchanges, good filtration, etc.) in your aquarium work. This is nothing new. Don't overfeed, and don't let vast amounts of uneaten food accumulate in your tank. Do regular water exchanges. "Aquarium Keeping 101."

However, the difference is that we, as lovers of natural, botanical-style aquariums are more thoughtful and deliberate about fostering that ol' microbiome- the vast community of organisms which reside our tanks and process the available nutrients. We don't spend our days fanatically "editing" Nature's real "cleanup crew" of fungal growths, bacterial biofilms, etc.

By actually embracing these organisms and encouraging them to grow and reproduce in our tanks, we're creating a vast nutrient export capability...One which utilizes materials like botanicals and leaves for "fuel", liberating nutrients and serving, on occasion, as a supplemental food source- part of the "food web"-in our aquariums.

I think that what's different is that we are now accepting the use of these materials for a combination of reasons- what we call "functional aesthetics"- the ability of a material to influence the look and the function of the aquarium environment simultaneously.

A real "mental shift..."

And of course, there are aesthetic components to this...

Some hobbyists have commented that, as their leaves and botanicals break down the scape as initially presented changes significantly over time. Wether they know it or not, they are grasping "Wabi-Sabi"...sort of. One must appreciate the beauty at various phases to really grasp the concept and appreciate it. To find little vignettes- little moments- of fleeting beauty that need not be permanent to enjoy.

And, despite their impermanence, these materials function as diverse harbors of life, ranging from fungal and biofilm mats, to algae, to micro crustaceans and even epiphytic plants. Decomposing leaves, seed pods, and tree branches make up the substrate for a complex web of life which helps the fishes that we're so fascinated by, flourish.

And, if you look at them objectively and carefully, these assemblages are beautiful.

This is not something "new" or previously unconsidered by the hobby, but it's something we don't give much thought to, I think. Of course, when we look at natural ecosystems where leaves and other botanical materials collect, the parallels in look and function become far more obvious!

Understanding the transient nature of botanical materials is absolutely essential for the botanical-style aquarium enthusiast. There are many who prefer a crisp, clean collection of botanicals and leaves in their tanks, and go to great effort to keep them that way...They will remove any leaf that starts to break down or recruit biofilms, and replace them with new ones. Cool, I suppose, but it's sort of the "aesthetics over function" mindset that currently dominates aquarium keeping...It also denies these organisms the ability to process these materials, right?

For most of us- those of us who've made that mental shift- we let Nature dictate the evolution of our tanks. We understand that the processes of biofilm recruitment, fungal growth, and decomposition work on a timeline, and in a manner that is not entirely under our control. We leave these materials in, and embrace Nature's work.

Decomposition is an amazing function, in which Nature process materials for use by the greater ecosystem. It's the first part of the recycling of nutrients that were used by the plant from which the botanical material came from. When a botanical decays, it is broken down and converted into more simple organic forms, which become food for all kinds of organisms at the base of the ecosystem.

In aquatic ecosystems, much of the initial breakdown of botanical materials is conducted by detritivores- specifically, fishes, aquatic insects and invertebrates, which serve to begin the process by feeding upon the tissues of the seed pod or leaf, while other species utilize the "waste products" which are produced during this process for their nutrition.

In these habitats, such as streams and flooded forests, a variety of species work in tandem with each other, with various organisms carrying out different stages of the decomposition process.

Some organisms, such as nematodes and chironomids ("Bloodworms!") will dig into the leaf structures and feed on the tissues themselves, as well as the fungi and bacteria found in and among them. These organisms, in turn, become part of the diet for many fishes.

And the resulting detritus produced by the "processed" and decomposing pant matter is considered by many aquatic ecologists to be an extremely significant food source for many fishes, especially in areas such as Amazonia and Southeast Asia, where the detritus is considered an essential factor in the food webs of these habitats.

And of course, if you observe the behavior of many of your fishes in the aquarium, such as characins, cyprinids, Loricarids, and others, you'll see that in between feedings, they'll spend an awful lot of time picking at "stuff" on the bottom of the tank. In a botanical style aquarium, this is a pretty common occurrence, and I believe an important benefit of this type of system.

I am of the opinion that a botanical-style aquarium, complete with its decomposing leaves and seed pods, can serve as a sort of "buffet" for many fishes- even those who's primary food sources are known to be things like insects and worms and such. Detritus and the organisms within it can provide an excellent supplemental food source for our fishes!

Just like in Nature.

That being said, I think we need to let ourselves embrace this stuff and celebrate it for what it is: Life. Sustenance. Diversity. Foraging. I think that those of us who maintain botanical-style aquariums who have made the "mental shift" to understand, accept, and even appreciate the appearance of this stuff, just look at things differently.

Natural habitats are absolutely filled with this stuff...in every nook and cranny. It's like the whole game here- an explosion of life-giving materials, free for the taking...

It's not everyone's idea of beauty. It requires us to let go...embrace something that seems so contrarian...yet is so elegant, beneficial, and remarkably reliable.

A true gift from Nature.

Yet, for a century or so in the hobby, our first instinct is to reach for the algae scraper or siphon hose, and lament our misfortune with our friends.

It need not be this way. Its appearance in our tanks is a blessing.

A truly "natural" aquarium is not sterile. It encourages the accumulation of organic materials and other nutrients- not in excess, of course. Biofilms, fungi, algae...detritus...all have their place in the aquarium. Not as an excuse for lousy or lazy husbandry- no- but as a means to process nutrients, and to provide supplemental food sources to power the life in our tanks.

Contrarian?

Maybe not.

Stay curious. Stay thoughtful. Stay bold. Stay observant. Stay consistent...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Blowing up The Barbs: The most under appreciated aquarium fishes?

"Hey, I'm thinking of getting some cool Barbs for my awesome new blackwater, botanical-style aquairum!" SAID NO ONE EVER.

Let's face it, with all of the amazing fishes available to the hobby, some get more favorable treatment than others. Some are simply loved more. Some get all of the "good press", and others get a bad reputation.

Example?

Well, Barbs...

Take this little quiz:

Quick- Which is the first word that comes to your mind when a fish geek says "Barbs?"

1) meh

2) mean

3) big

4) messy

5) dull

6) meh

Sensing a theme here?

I think so.

I think my "theme" is admittedly based on equal parts childhood experiences, fish store "chatter", outdated information, and good old lack of experience with them over the years. The same kind of lack of experience which has resulted in so much bad, third-hand, and regurgitated information in a lot of hobby sectors (even in ours, thanks to some arrogant, self-proclaimed "experts" who aren't!)

It shouldn't be this way, but I'm pretty certain, just based on conversations that I have with fellow hobbyists, that, if you poll a random group of hobbyists (and I have), you see this exact sort of response.

And any time "meh" comes up twice in a few seconds when talking about a group of fishes, you know that there are equal parts of inexperience and a sprinkling of ignorance mixed in there somewhere!

Yup.

Barbs are "old school" fishes, for sure.

I mean, even the name "Barb" is sort of "old school" sounding- like a name origin lost in the thick mists of aquarium history..a haze of metal-framed aquariums, "nylon filter floss", and "air-powered outside filters..."

Even the name "Barb"- sort of reeks of that "big, gnarly PROBLEM fish" label, right? I mean, they're called freakin' "BARBS?" Really?

The family Cyprinidae needs to hire a new marketing agency, like pronto!

According to the venerable Wikipedia, The root of the group, "Barb" is "common in cyprinid names of European languages", derived from the Latin word, "barba"- a humble reference to the "barbels" which are prominently seen around the mouth of many fishes we classify as "barbs".

Old school.

Yeah. Sounds really "1950's" to me. And that means it's a group of fishes that's ready for a new look.

Okay, I'll admit it, for all to hear:

I consider myself an "advanced" hobbyist, but I'm shockingly ignorant about Barbs.

Perfect time for me to write something about some fishes I know so little about! What could go wrong? 😆

And it's not like Barbs are obscure fishes, kept only by highly advanced specialists or ignorant beginners. Nope. They're really considered one of the "cornerstone" groups of aquarium fishes...well, sort of...Right?

I think so.

And I fully admit, I'm downright lacking in my knowledge of them as compared to fishes like characins and killies and such. I'm going to be a bit arrogantly presumptuous for a moment and suggest that many of you might be, too!

I mean, I can identify some of the more popular members of the group. I can hold my own in a very lightweight conversation on them with general hobbyists. However, once you get beyond, "Which do you like better: The 'classic' Tiger Barb, or the 'Moss Green' Tiger Barb?" my lack of current knowledge is "front and center!"

Yet, when you think about "Barbs"- that's like IT, right? I mean, "Tiger Barb", "Cherry Barb", "Tinfoil Barb", and...um, well...uhh...?

Not only am I sort of ignorant about 'em...I never even really gave them a fair shake over the past- oh, like 25 years or so...

And that's a real shame. They're kind of- well, cool!

It's hard to imagine being this ignorant or at least, indifferent- about a group of fishes that are so pervasive in the hobby, but I simply think it's because I just haven't played with them as much as other fishes. When I was a kid, I always had a few Cherry Barbs or Tiger Barbs; maybe a "Gold Barb" or two- in my tanks- but was always held back from trying others by what "the books" said about them. I was literally scared away from them:

"Aggressive!" "Metallic." (aquarium hobby code word for "butt-ass ugly", BTW) "May eat aquatic plants!" "Produce copious amounts of metabolic waste", "Attain 5 inches in length!"

Shit. That's some bad PR, huh? I mean, hardly makes them "aspirational" when you are a kid with a 10-gallon community tank.

I was doomed from the earliest days in my hobby "career" to simply smile as I walked by tanks filled with them at the LFS...

Literally, they're "typecast" as mean, ugly, tropical versions of Goldfish!

"Barb bashing" is like a "given" in our hobby for some reason.. So sad. And so common...

So, I was like a classic example of someone who was simply "programmed" by the popular opinions of the day, and it sort of shut me down on this large and diverse group of fishes for decades! And you wonder why now, in my ripe old middle age, I've become the aquarium world's "pied piper" of, "Question everything again!"

I think that it's time to re-think these fishes. Yeah, we all need to look at them yet again. Ignorance, or simply accepting the most basic dismissals of them without further consideration is no longer acceptable!

Now, I'm certain that I'm the ONLY one who was sort of "chased off" by the popular sentiment regarding these guys! Think about it: Why is it that we have all sorts of Cichlid clubs, Killie clubs, Betta clubs, Guppy Clubs, even Catfish clubs and Shrimp clubs, but NO "Cyprinid clubs" ("Okay, you can say the same about characins, too...but let's stick to the Barbs here, Fellman" )?

Curious.

Maybe what's not helping these guys is that, taxonomically, they're heaped into the family Cyprinidae, which also includes such notable big, messy, butt-ugly and non-aquarium-friendly fishes as...Carps and Minnows...Yeah.

Damn taxonomists!

Now, in defense, the family Cyprinidae also includes the ultra-cool Danios and the popular "Sharks", not to mention, the rad group of fishes that we collectively refer to as Rasbora...

So, we can't categorically "dis" the whole group...but man- the "poster children" of the family are, well...pretty much everything our forefathers in the aquarium world told us: Big, ugly, gluttonous fishes that would pretty much lay to waste any well-managed aquarium in minutes!

(Cyprus carpio- Latin for "Big fuckng ugly fish?" Well, it scared me off! Pic by Kapr Obecny-Used under CC BY SA-3.)

Or we hear of pretty, yet mass-bred, genetically-weak, mankind-exploited versions of these fishes, damning the marketplace for years with their general "non-vigorousness..." So, the caveats about this group of fishes DO become ingrained into our collective fish-geek psyche from an early age, don't they?

But then again, if you're a kid, looking for active, cool fishes for your first 20-gallon tank, the Tiger Barb (currently Systomus tetrazona, I think) and it's relatives are sort of hard to turn away from...Of course, until said Tiger Barb and its pals starts beating the shit out of your Neons in your small "community" tank, that is.

Yet, that's not really the fish's fault, right?

(The "classic" Tiger Barb. Pic by Anandarajkumar -used under CC-BY-SA 3.0)

The reality is that many, many of these guys DO make cool aquarium fish, particularly if your tank is large enough to keep a school, and to provide enough room for the other inhabitants to "get out of the way" when the barbs start partying. I mean, "relentlessly active" doesn't always translate into "aggressive", right?

Especially when they're maintained in a tank set up for their needs.

Stuff we need to research, think about, and prepare for before we purchase. Otherwise, the "hate cycle" continues forever, as the fish live up to our very lowest base expectations of them.

And yes, speaking of needs- there are a ton of Barbs that come from tinted, acidic waters in Southeast Asia- perfect for what we do.

And perfect for a well-researched "biotope-inspired" aquarium, right? Yeah. I think this is another group of fishes that could benefit from being maintained under conditions more closely representing their natural habitats...which are both interesting and attractive aquarium subjects.

(Yeah, the "Siamese Tiger Barb", Putnigrus partipentazona...Hello, Asian biotope aquarium!)

Can you imagine a Barb "biotope" tank? One which "riffs" on some of the sexy botanical-laden blackwater habitats from which many come from?

Oh, yeah. I can!

Jungle streams, filled with leaves, seed pods, interesting rocks, plants...the sort of habitats that make even the most jaded fish geek sit up and give them a second look.

Well, wait just a minute...Seems as though we've been down this road before.

Remember our video, "The Tint Meets The Aquascaper", by the legendary George Farmer, which we featured a few years back?

What fish did George choose to "star" in this awesome blackwater aquarium?

Why, Puntius pentazona, which look incredibly sexy when given the proper environment, don't they? And when an aquarium personality with the extraordinary taste and talent of George-freaking-Farmer chooses to feature them in one of his videos, you'd think it would open up the floodgates to a new era of popularity for these seemingly forgotten fishes...

Nope.

Nothing.

Zilch.

Crickets.

I haven't seen a "barb-centric" display since that one. Not even a request to do an "Enigma Pack" for a Barb tank.

Nada.

A tank that nice, by a hobbyist that famous, with fish this cool- should have definitely helped change some minds about this diverse group of fishes. And yet...I still cannot recall off the top of my head if, to date, I have received a pic of a single tank from a member of our community, inspired by George's tank, set up exclusively for- or even simply featuring-Barbs!

No respect.

So we'll keep forging ahead...

Hoping to undo a century or so of "bad programming" that we and hobbyists worldwide have been exposed to, telling us to approach them with extreme caution...If at all.

Counter-programming is necessary. An "aquairum intervention" of sorts!

We had to do a little of it ourselves...We featured a sexy, Asian-themed botanical-style tank from Johnny Ciotti absolutely "starred" Barbs- specifically, a group of Desmopuntius omboocellatus- the "Snakeskin Barb" from Mike Tuccinardi-one of THE coolest barbs you'll ever see. They're flat-out awesome in this tank. And peaceful. And they don't eat aquatic plants.

Our Barb "Anti-Hero" had arrived!

Social media freaked the fuck out...And, then?

Crickets.

Oddly familiar.

That tank had everything going for it: Size, style, environment, plants, tinted water...

Yeah, you almost never see Barbs kept in a proper context like this, IMHO. And context, as we know, can make a big difference in perception of a given species within the aquarium hobby.

But it takes repetition, I suppose.

Even I, finally disgruntled by the lack of respect these fishes receive from the hobby, and eager to set up an aquairum which replicated some aspects of their habitat, decided to feature those same "Snakeskin Barbs" in my "Asian-inspired" tank. It was hard, because as you know, I have a bit of a South American "bias" and this was a bit out of my area of expertise...

Yet, I dutifully executed.

The fish were surprisingly shy, hiding a lot of the day (maybe 'cause I had so damn many small Rasbora in there?), but coming to life daily during feeding. And yeah, the predictable happened: A whole lot of "WOW! Those fish are HOT! What are they?" comments on Instagram- lots of 💕, and yet, I never saw nor heard of anyone else ever setting up a tank with them for themselves, inspired by our efforts...

Sigh.

So we've seen and presented few "modern twists" on the idea of Barbs in an aquarium conceived around them...

And still...the sound of silence.

Weird, huh?

I mean, they truly look amazing in blackwater! What's the deal here?

Hello?

Really, what IS it that keeps these fishes from exploding with popularity?

I'm at a loss, here.

Work with me, people...

I really do think that this is a group that truly suffered/suffers from the cumulative effects of "bad press" they've received over the decades, warning us about the general need for "large tanks", "hefty filters", "tough tank mates", etc. I totally fell for this stuff, when the reality is that, as that a group, many of these guys don't seem all that much more aggressive than a bunch of rowdy Apistos, if you ask me.

And they're not nearly as touchy!

Yes, there are some aggressive ones. There are some huge ones. There are some which poop like mad. And yeah, there are some which tear up live plants.

So, simple solution: We can just avoid these pain-in-the-ass species, right?

Easy.

Yeah...totally.

I think that we can collectively blow up the popularity of Barbs by maintaining the most "aquarium-friendly" species under the most appropriate possible conditions. Study the natural habitats where they come from (Google!). Employ botanicals. Select the correct plants. Follow rigorous husbandry regimens.

Nothing different here than we've done for so many other varieties of fishes, right?

The fact that they are so diverse, generally hardy (with the possible exception of the damn Cherry Barb for many of us-perhaps because it's a victim of lowest-common-denominator "commoditized breeding", rather than any fault of the fish itself), and typically rather easy to breed, makes the "disrespect" they have received by the general hobby all that much more perplexing.

And interestingly, Barbs do have a certain "character" that many of the shoaling fishes we keep (like my beloved Tetras) seem to lack. Maybe it's because many of them are "larger" fishes by aquarium hobby standards- 3" (7.62cm) or so on the average, and almost seem to have individual "personalities.." A far cry from my little mindless, "micro-drone" Tetras, I think.

That's a pretty cool thing, right?

They do have that sort of "It factor" going for them... Sure, some WILL tear up plants...some will get a bit rambunctious at times..but I mean, c'mon...plants or fishes? And, what's wrong with a little "spirit" now and then? Really. I mean, tons of people love fucking Eartheaters, right? Like, why?

Seriously, though- you CAN compromise. And there are some damn good "compromises" from which to choose!

(The undeniably sexy Black Ruby Barb (Puntius nigrofasciatus), captured by my mentor, the late, great Bob Fenner!)

There are numerous relatively modest-sized species, which, when placed in an aquarium designed to highlight them and accommodate their needs, can create a vibe and aesthetic that are truly second to none. We know that "subtle" coloration is not a "nonstarter" for a fishes kept in a botanical-style, blackwater aquarium.

The right conditions can really highlight a fish in a very special way!

Of course, in a blog piece of this necessary brevity, we can scarcely scratch the surface of this topic, short of giving everyone a little shove to research more about them and consider them for inclusion in your next tank!

I know that I will.

With sufficient swimming space, water chemistry, and oh...aquatic plants and botanicals- what kinds of fascinating results are possible? Perhaps a break in the "meh cycle," which has unfairly plagued these fishes for decades in the hobby.

Barbs, like so many of the fishes we play with in our aquariums, benefit- and suffer- from the perceptions and "misconceptions" they dealt with for years.

Yeah, not all of them are aggressive, mean bastards that nip fins and eat Bucephelandra, so maybe we need to give 'em yet another look...and cut 'em some slack?

I think we do...

Perhaps, looking more closely at Barbs can help us improve in other areas, too? Perhaps there is a lesson to be learned that can be applied to the hobby, or even life in general? By giving them the respect and consideration they deserve, we can absolutely "de-program" ourselves from the (unfair) biases of our own making, avoiding the over-generalization and stereotyping which sours so many things in our culture, right?

Damn. I'm feeling like Barbs can change the world!

Well, maybe they can change the hobby!

Let's start by seeing if they can change a few minds, first, right?

Let's take the "blah" out of the "Barb equation", okay?

Let's just do it!

Yeah! Sure, some can get big. Some are nasty at times. Some do destroy plants.

Not all of them, though.

Do some research..Perhaps other than the general hobby stuff? Scholarly articles on fishes can yield tons of good stuff that's actually factual! Yeah, some of it is dry and dull, so roll up your sleeves, mix a cocktail, and just deal. You'll find some cool stuff out there, trust me!

Break out the leaf litter, line up some dark substrate material...Set up that 55-gallon tank you've been itching to play with...and, this time...add a group of Barbs to it!

You can do it!

As always...Stay excited. Stay thoughtful. Stay open-minded. Stay curious. Stay excited...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Life in the litter beds

It would hardly be a stretch to state that we're about as geeked-out about leaf litter habitats, and creating aquariums that replicate this unique habitat. And of course, when you're creating such a habitat in your aquarium, it makes sense that you'd want to give a lot of thought to how to do this first. I know that we've talked about it before, but there's so much interest in this idea that I just HAD to bring it up once again!

First off, a quick review. As you recall, leaf litter beds are found throughout tropical rivers, streams, flooded forest floors, and other watercourses around the world, from South America, to Asia, and Africa, to name just a few regions. They are remarkably productive habitats, because they offer not only shelter for their inhabitants, but food items, an area to reproduce, and function as a "nursery" of sorts for larval fishes to shelter and feed in. They are among the most productive environments in the wild.

Leaf litter comes from a variety of trees in the rainforests of the tropical world. There is a near constant leaf drop occurring, which continuously “refreshes” the supply. In monsoonal climates, large quantities of leaves will drop during the dry season, and many will find their way into streams which run through the rain forest. In other habitats, such as the igapo forests of Amazonia,, the leaves fall onto the forest floor and accumulate, and are seasonally-inundated during the rainy season, creating an extremely diverse and compelling environment that we love so much around here!

The leaf litter in an igapo when inundated can be as much as 3 feet (1 meter) or more deep, with a huge amount of surface area available to bacteria (which create biofilms) and are often home to surprisingly large populations of fishes like Apistogramma, which use the shelter and “on-board” food offered by these habitats- to their advantage. And they’re vital to some of the small Elacocharax and other “Darter Tetras” which live almost exclusively in these niche habitats. Oh, and shrimp, too!

Suffice it to say, the leaf litter bed is a surprisingly dynamic, and one might even say "rich" little benthic biotope, contained within the otherwise "impoverished" waters. And, as we've discussed before on these pages, it should come as no surprise that a large and surprisingly diverse assemblage of fishes make their homes within and closely adjacent to, these litter beds. These are little "food oasis" in areas otherwise relatively devoid of food.

The fishes are not there just to look at the pretty leaves!

I'm obsessed with leaf litter in the wild and in the aquarium. I think it's because it's literally an oasis of life. Compelling, diverse, and productive.

Many tropical rivers and streams are characterized by large quantities of leaf litter and decaying botanicals on the bottom, with typically clear (but tinted) water. As discussed many times in this column, leaf litter is used as shelter, spawning ground, feeding area, and in some instances, as supplemental food itself. This is a highly productive habitat in nature that also just happens to look really cool in our aquariums, performing exactly the same function!

And fish population density is often correlated with the availability of food resources- and, as we've discussed many times here, leaf litter beds are highly productive food resources!

In wild habitats, there have been many instances where researchers have counted literally hundreds of fishes per square foot inhabiting the matrix of botanical materials on the bottom of stream beds, which consists primarily of leaf litter. As dead leaves are broken down by bacterial and fungal action, they develop biofilms and associated populations of microorganisms ("infusoria", etc.) that are an ideal food source for larval fishes.

When you take into account that blackwater environments typically have relatively small populations of planktonic organisms that fish can consume, it makes sense that the productive leaf litter zones are so attractive to fishes! That being said, leaf litter beds are most amicable to a diversity of life forms These life forms, both planktonic and insect, tend to feed off of the leaf litter itself, as well as fungi and bacteria present in them as they decompose.

The leaf litter bed is a surprisingly dynamic, and one might even say "rich" little benthic biotope, contained within the otherwise "impoverished" waters. And, as we've discussed before on these pages, it should come as no surprise that a large and surprisingly diverse assemblage of fishes make their homes within and closely adjacent to, these litter beds. These are little "food oasis" in areas otherwise relatively devoid of food.

Can we replicate this "food production" concept in our aquariums?

Yeah, we can!

And this aquarium ran incredibly successfully!

Like, super successfully...and easy.

And it was interesting too, from an aquarium function perspective. There was virtually no traditional "cycle time"-curiously. And even more interesting, the tank stayed super "clean" in appearance. It did recruit some visible biofilm on the leaf surfaces, although it never really "bloomed" significantly after the first few weeks, and waned on its own in less than a month.

My goal was quite bold: To run an aquarium without any supplemental feeding of the resident fishes.

And it worked fabulously. (if I say so, myself!)

Of course, despite my successful experiments In this "no-supplemental-feeding" realm, I have no illusions that the idea of just tossing fishes into an aquarium and letting them fend for themselves is some panacea and "ultimate" way to keep fishes. Nope. And, I did perform routine weekly water exchanges and regular filter cleanings (I used an Ehiem 2211).

Nothing crazy there, really. And certainly not anything that would even qualify as "benign neglect", either. There was definitely not anything close to that. Interestingly, there was no detectible nitrate and phosphate in this aquarium during the entire operational lifespan of the system.

Much like in Nature, if properly conceived and populated with an initial population of live food sources, I believe that an aquarium can be configured to create a productive, biologically-sustainable system, requiring little to no supplemental food input on the part of the aquarist to function successfully for extended periods of time.

Of course, it is significantly different than a natural, fully-open system in many ways. And this is not a "revolutionary" statement or pronunciation, or some "breakthrough" in the art of aquarium keeping.

No.

It is just an idea that- like so many we encourage here- replicates some aspects of natural aquatic systems. With responsible management and continued experimentation, I really see no reason why this concept couldn't be done on a larger scale with the same great success.

My next iteration of this experiment will be to apply this idea to a tank with a significantly deeper leaf litter bed- something like 3"-4" (7.62cm-10.16cm), to see if there are different possible outcomes with a greater leaf biomass. I am very curious to see if a deeper leaf litter bed functions similarly to the shallow type if regular maintenance is employed.

I suspect there will be not much difference in "performance."

There's so much to learn from these sorts of fun experiments...both about the natural leaf litter beds of the world, and the ability to recreate their function in our aquariums...Let's see some more work in this cool little speciality sector of the botanical-style aquarium!

Stay creative. Stay curious. Stay Excited. Stay diligent. Stay observant...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Great...Expectations?

By now, this whole idea of adding botanical materials to our aquariums for the purpose of helping create the physical, biological, and chemical environment of our aquariums is becoming way more familiar. Yet, no matter how many times you've created a botanical-influenced natural aquarium, the experience seems new and somehow different.

Expectations are funny things, aren't they?

There is something very pure and evocative-even a bit "uncomfortable" about utilizing botanical materials in the aquarium. Selecting, preparing, and utilizing them is more than just a practice- it's an experience. A journey. One which we can all take- and all benefit from.

Right along with our fishes, of course!

And yeah, it can even be seen as a bit of a spiritual journey, too- leading to some form of enlightenment and education about Nature, from a totally unique perspective.

The energy and creativity that you bring with you on the journey tends to become amplified during the experience. As you work with botanicals in your aquariums, your mind takes you to different places; new ideas for how your aquarium's microcosm can evolve start flooding your mind. Every tank- like every hobbyist- is different- and different inspirations arise. We don’t want everyone walking away feeling the same thing, quite the opposite actually.

That uniqueness is a large part of the experience.

The experience is largely about discovery. And today's piece is a bit about some of the interesting discoveries- expectations, and revelations that we as a community have learned along the way during our experiences working with botanicals in our aquariums.

Our aquariums evolve, as do the materials within them. We've discussed this concept many times, but it's one that we keep coming back to.

If we think of an aquarium as we do a natural aquatic ecosystem, it's certainly realistic to assume that some of the materials in the ecosystem will change, re-distribute, or completely decompose over time.

Botanicals are not "forever" aquascaping materials. We consider them ephemeral in nature. They will soften, break down, and otherwise decompose over time. Some materials, like leaves- particularly Catappa and Guava, will break down more rapidly than others, and if you're like our friend Jeff Senske of Aquaiuim Design Group, and like the look of intact leaves versus partially decomposed ones, you'll want to replace them more frequently; typically on the order of every three weeks or so, in order to have more-or-less "intact" leaves in your tank.

On the other hand, if you're like me, and enjoy the more natural look that occurs as the leaves break down, just keep 'em in. You may need to remove some materials if you find fungal growth, biofilm, or other growth unsightly or otherwise untenable, or if material gets caught up in filter inlets, etc. However, "operational concerns" aside, and if you've made that "mental shift" and can tolerate the stuff decomposing, just let them be and enjoy!

Botanicals like the really hard seed pods (Sterculia Pods", "Cariniana Pods", "Afzelia Pods"), etc., can last for many, many months, and generally will soften on their interiors long before any decomposition occurs on the exterior "shell" of he botanical. In fact, they'll typically recruit biofilms, which almost seem to serve as a sort of "protective cover" that preserves them.

Often times, fishes like Plecos, Otocinculus catfish, loaches, Headstanders, and bottom-dwelling fishes will rasp or pick at the decomposing botanicals, which further speeds up the process. Others, like Caridina shrimp, Apistos, characins, and others, will pick at biofilms covering the interior and exterior of various botanicals, as well as at the microfauna which live among them, just as they do in Nature.

Sometimes, the fishes will use botanical materials for a spawning site.

We receive a lot of questions about which botanicals will "tint the water the darkest" or whatever. Cool questions. Well, here's the deal: Virtually all botanical materials will impact the color of the water. You'll find, as we have, that different materials will impart different colors into the water. It will typically be clear, but with a golden, brownish, or perhaps a slight reddish tint.

The degree of tint imparted will be determined by various factors, such as how much of the materials you use in your tank, how long they were boiled and soaked during the preparation process, if you're using activated carbon or other chemical filter media, and how much water movement is in your system. However, rest assured, almost any botanical materials you submerge in your tank will impart some color to the water.

Unfortunately, since botanicals are natural materials, there is no "recipe'; no formula with a set "X number of leaves/pods per ___ gallons of aquarium capacity", and you'll have to use your judgement as to how much is too much! It's as much of an "art" as it is a "science!"

Now, If you really dislike the tinted water, but love the look of the botanicals you can mitigate some of this by employing a lmuch onger "post-boil" soaking period- like over a week. Keep changing the water in your soaking container daily, which will help eliminate some of the accumulating organics, as well as to help you to determine the length of time that you need to keep soaking the botanicals to minimize the tint.

Of course, it's far easier to simply employ chemical filtration media, such as activated carbon, and/or synthetic adsorbents such as Seachem Purigen, to help eliminate a good portion of the excess discoloration within the display aquarium where the botanicals will ultimately "reside."

Another interesting phenomenon about "living with your botanicals" is that they will "redistribute" throughout the aquarium. They're being moved around by both current and the activities of fishes, as well as during our maintenance activities, etc. This is, not surprisingly, very similar to what occurs in Nature, where various events carry materials like seed pods, branches, leaves, etc. to various locales within a given body of water.

In our opinion, this movement of materials, along with the natural and "assisted" decomposition that occurs, will contribute to a surprisingly dynamic environment!

Your aquarium water may appear turbid at various times. We are pretty comfortable with this idea; however, some of you may not be. As bacteria act to break down botanical materials, they may impart a bit of "cloudiness" into the the water. Also, materials such as lignin and good old terrestrial soils/silt find their way into our tanks at times.

Some of these inputs, such as soils- are intentional! Others are the unintended by-product of the materials we use, The look is definitely different than what we as aquarists have been indoctrinated to accept as "normal." One of my good friends, and a botanical-style aquarium freak, calls this phenomenon "flavor"- and we see it as an ultimate expression of a truly natural-looking aquarium.

Yeah, the water itself becomes part of the attraction. The color, the "texture", and the clarity of the water are as engrossing and fascinating as the materials which affect it. It's something that you either love or simply hate...everyone who ventures into this method of aquarium keeping needs to make their own determination of wether or not they like it.

Need a bit more convincing to embrace the charm of the water itself in botanical-style aquariums?

Simply look at a natural underwater habitat, such as an igapo or flooded varzea grassland, and see for yourself the allure of these dynamic habitats, and how they're ripe for replication in the aquarium. You'll understand how the terrestrial materials impact the now aquatic environment- the function AND the aesthetic-fundamental to the philosophy of the botanical-style aquarium.

Speaking of the impact of terrestrial materials on the aquatic habitat- remember, too, that just like in Nature, if new botanicals are added into the aquarium as others break down, you'll have more-or-less continuous influx of materials to help provide enrichment to the aquarium environment. This type of "renewal" creates a very dynamic, ever-changing physical environment, while helping keep water chemistry changes to a minimum.

This is the perfect analog to the concept of "allochthonous input" which occurs in wild aquatic habitats- materials from outside the aquatic environment- such as the surrounding forest- entering and influencing the aquatic environment.

The fishes in your system may ultimately display many interesting behaviors, such as foraging activities, territorial defense, and even spawning, as a result of this regular influx of "fresh" aquatic botanicals. You could even get pretty creative, and attempt to replicate seasonal "wet" and "dry" times by adding new materials at specified times throughout the year...The possibilities here are as diverse and interesting as the range of materials that we have to play with!

Go into this with the expectation that you might get to experience an entirely different way of looking at aquariums- and the natural environments we try to replicate- and you'll never be disappointed.

It's all a part of your "life with botanicals"- an ever-changing, always interesting dynamic that can impact your fishes in so many beneficial ways.

Stay dedicated. Stay excited. Stay engaged. Stay resourceful...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

The joys of randomness...

I don't know about you, but I find myself coming up with new aquariums ideas all the time.

Now, I'm not talking about new "aquascapes", mind you. Rather, I"m talking about different ideas for recreating various features I see in the wild habitats; figuring out how to model their function as well as their form, in the most realistic way possible.

I'm a big fan of some of the more obscure features that you see in Nature. And when you consider that virtually all freshwater fishes come into contact with some botanical materials throughout their existence, it opens your mind to the possibilities. In virtually every body of water, you'll find some sunken branches, tree trunks, leaves, roots, seed pods, etc.- stuff which can create really interesting features to support all sorts of fishes.

And this doesn't require us to do tremendous amount of "aquascaping" in the traditional hobby sense. Rather, it's more about seeing how Nature does it...

Huh?

As aquarists, we put an amazing amount of time into trying to achieve a perfect placement for wood, when the reality is that, in Nature, it's decidedly random. Is there not beauty in "randomness", despite our pursuit of the "Golden Ratio", etc?

There is. Think about it.

Just because last year's big 'scaping contest winner had the "perfect" orientation, ratios, and alignment of wood and stones within the tank, doesn't mean it's a real representation of the natural functionality of "randomness."

What dictates how and why stuff is distributed in Nature.

When you think about how materials "get around" in the wild aquatic habitats, there are a few factors which influence both the accumulation and distribution of them. In many topical streams, the water depth and intensity of the flow changes during periods of rain and runoff, creating significant re-distribution of the materials which accumulate on the bottom, such as leaves, seed pods, and the like.

Larger, more "hefty" materials, such as submerged logs, etc., will tend to move less frequently, and in many instances, they'll remain stationary, providing a physical diversion for water as substrate materials accumulate around them.

Most of the small materials, like branches, seed pods, and leaves may tend to move around quite a bit before ultimately settling and accumulating in a specific area. One might say that the "material changes" created by this movement of materials can have significant implications for fishes. In the wild, they follow the food, often existing in, and subsisting off of what they can find in these areas.

Now, in the case of our aquariums, this "redistribution" of material can create interesting opportunities to not only switch up the aesthetics of our tanks, but to provide new and unique little physical areas for many of the fishes we keep. So-called "microhabitats" that facilitate interesting behaviors and habits in our fishes, while supporting their grazing and spawning activities.

Fishes taking advantage of a niches you can create in your system is super important. Not exactly novel, but often overlooked. The kinds of "niches" you offer can have profound positive impact on the lives of your fishes. And the reality is that, even if we don't intentionally create them, we will see these little microhabitats in our botanical-style aquariums.

That's part of the reason why I like more delicately-branching pieces of wood snd roots for my tanks...They open up many possibilities... And they serve an identical set of functions in the aquarium as they do in Nature.

Some of the best tanks I think I've personally ever created have embraced the random placement of these kinds of roots to create sort of intricate, effortless, slightly chaotic, yet utterly natural look.

And there is that whole dynamic between the aquatic environment and the terrestrial one.

The interaction between the terrestrial elements and the aquatic ones is really interesting, because it presents unique opportunity to observe how these combinations of materials foster our fishes' natural behaviors in the aquarium.

Allowing terrestrial leaves to accumulate naturally among the "tree root structure" we have created fosters this more natural-functioning environment. As these leaves begin to soften and ultimately break down, they will foster microbial growth, biofilms, and fungal growths- all of which will provide supplemental foods for the resident fishes...just like what happens in Nature.

Taking a more "functional" approach to creating our aquariums and their aquascapes is something that I think we need to spend more "mental capital" on. The typical aquarium hardscape- artistic and beautiful as it might be- generally replicates the most superficial aesthetic aspects of such habitats, and tends to overlook their function- and the reasons why such habitats form.

And sometimes, this "functionally aesthetic" approach requires that we embrace bit of randomness. Not just in our designs, but in the function of our aquariums.

At almost any stage in an aquarium’s life, there are seemingly random little niches and evolving environmental changes within the system that you can use to your advantage by “planting” aquascaping props (seed pods, leaves, wood, etc.) appropriate for the given niche.

It even goes beyond planned aesthetics (ie; “That piece of wood would look awesome there!”) and, much like happens in the natural environment- plants grow and fishes gather where conditions are appropriate. Fishes take opportunities to live among the debris on newly-inundated forest floors...

Reminds me of the little weeds that just seem to pop up out of the cracks in the sidewalk pavement…you can’t help but admire the resourcefulness and tenacity of life. If you do, you'll find many times that, not only has the weed utilized this little niche- so has a small "ecosystem" of other plants and insects.

It's quite amazing, actually.

It's a process which continuously occurs in natural aquatic habitats…and our aquariums. Those small details which create amazing functional components within our aquariums.

When you're checking out your tank, don’t just look for what you might think is the "prime" viewing spot. Look for the “cracks in the pavement", in your tanks, too. Those little details- those unique places where fishes can hide, forage among, and spawn.

Embrace the more relaxed, yet complex, and fully random aspects of your aquascape.

Your fishes certainly will.

Stay observant. Stay creative. Stay excited. Stay curious...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Absolutely...Not?

The aquarium hobby is exploding with talent, ideas, and progress. Yet, it still has some dark areas which can hold back the progression.

One of the more annoying things to me in the hobby is hearing other hobbyists- or so-called "experts"- telling you stuff like, "No. You can't do that!" Or, "It won't work!" with almost no explanation-or perhaps a "regurgitated" answer...You know, one of those "second or third-hand" answers, with perhaps little (or worse) NO personal experience behind them.

Absolutes which can be frightfully damaging to the hobby, because they discourage executing new ideas.

Now, look, personal opinions/warnings/recommendations based upon your experience, and that of a number of others are very helpful. However, what I'm concerned with here is the stuff you see a lot out there: People out on the hobby forums, websites, conferences, and blogs, passing on “wisdom” that might be of dubious accuracy and origin- or, at the very least, information that may be overly-generalized and passed on without experience in the given area.

That's just nuts, IMHO.

Classic examples of this are "absolutes" like, “You can’t keep_______ alive in an aquarium!”, or “If you use that product, you’ll have this major algae problem in your tank”, etc. Often, the advice is dispensed with such authority and confidence that a typical hobbyist will not even question it. Some of it is really negative. Some of it is simply based on one bad personal experience, and context is not given, giving everyone the impression that if you do "X", then"Y" will absolutely happen.

I heard this a lot in the context of botanical-focused aquariums when Tannin was first starting out. A lot of hobbyists felt that the ideas that I was sharing and philosophies which I was espousing were a radical departure from the comfort zone which has been established in the hobby for decades. And I think that angered some people, and possibly even scared others.

Now, it's not like I go out of my way to try to counter every single piece of solid aquarium doctrine snd wisdom that's been metered out over the years "just because." Much of it IS quite good. It's just that I've explored ways of doing things differently...and that there are other ways todo stuff successfully. I am open to looking at the function of wild habitats and how we might be able to interpret their function in the aquarium.

Re-examining some of what we do is important. Other practices are justifiably followed without much disagreement.

If you’ve been “around the block” a few times in this hobby, you’ll hear fellow hobbyists dispensing words of aquatic wisdom to anyone who needs it. You know, the usual stuff, like, “You need to quarantine new animal purchases”, “Use common sense when stocking tanks”, "Perform regular water changes”, etc.

This stuff forms the “religion" of our hobby: Core beliefs -or unshakable truths- which we pass on to all those who join our ranks. Fundamental, knowledge which we all feel that you need to have at least a working knowledge of to attain success in the hobby. It’s beautiful that most hobbyists are so willing to help out their fellow fish geeks by sharing this acquired wisdom- a true testimony to the quality of people in the aquatic world.

It's all good. It can evolve over time, too.

However, the scary stuff is that some “advice” on very specific topics is dispensed by a casual hobbyist with limited-or even no- experience in the given area. Sure, the intent might be to "pass along" information that is helpful in some way; however, without that personal experience with which to provide context it's just problematic.

Examples?

Advice based on third-party experiences without all of the details (“Don’t keep that cichlid. This guy up in New York had one of those and said that it nuked his tank with ich." ), sweeping generalizations (“You can't run aquariums at a low pH-it will crash your tank”), dogmatic human-imposed "rules" (You need to balance that rock formation with 3 smaller groupings or it's not the authentic _____ style."), anecdotal evidence ("Garlic 'cures' ich in saltwater fish"), and outright absurdity, ("You can’t keep plants alive long term in blackwater aquariums”) are just a few examples that we've heard over the years, and they can really do harm to the hobby, in my opinion, discouraging progression and the desire to try new things.

I've written about this negativity stuff before a few years back, and still bring it up in in my lectures, because it's an issue that doesn't seem to go away. It's like there are some people who simply feel compelled to "sabotage" the well-intentioned, yet progressive efforts of others. It's like they're afraid to see others succeed or change what's comfortable to them.

Them.

I have a distinct dislike for "them"- those people in the aquarium world who feel it necessary to discourage others from breaking new ground and doing things that are a bit different; those who love to preach and regurgitate the rhetoric of "because this is how it's done." I hate "keyboard warriors" who foment the criticism of anyone who dares to try something others have dismissed without ever even trying for themselves. There is a certain dogma to discouraging others that I find repulsive.

This discouragement from trying new ideas is a problem, IMHO. Sometimes, we just have to be brave and forge ahead with our seemingly "wacky" idea, because it's our truth. You need to have the courage of your convictions. You might have to be the person out on "point", who has to whip out the machete, hack down the vines, and be first to see what's in that seemingly impenetrable forest.

Living your life based on the judgement of others is the absolute recipe for unhappiness- both in life and in the aquarium hobby.

It seems like,whenever you see something becoming an emerging "trend" (Urghhh.. I HATE that word when used in the context of an aquarium topic!), you will see hobbyists making incorrect assumptions, having general misconceptions, and occasionally, unintentionally spreading wrong information about stuff. You know, regurgitating outdated or erroneous information that's been floating around out there on line for decades...

It's often a function of the fact that some of this stuff has been either under-utilized, completely misunderstood, or simply not appreciated for so long, that we've simply not really considered the dynamics involved in this context.

Totally understandable, really.

And there is always someone who has to be the first to accomplish something great. Someone who can overlook the negativity and "smack talk", to fly in the face of convention while taking that road less traveled. Someone with a belief so strong in their idea that they're willing to face the naysayers and the criticism and do their thing. Humility and tenacity- in equal proportions.

This is how we progress. This is how we will continue to progress in the hobby.

And more important, this is how we inspire a new generation of hobbyists to follow our lead, for the benefit of both the hobby and the animals that we enjoy. We simply can't dispense advise to fellow hobbyists with a dogmatic attitude that discourages progress and responsible experimentation any more.

It will just stagnate the progress of the hobby we all love.

Is there a downside to pushing the boundaries?

Well, sure. Bad shit can happen. The inevitable chorus of "I told you so" form the naysayers who tried to discourage you from trying in the first place is not fun to hear for many. However, that's no reason NOT to try to progress.

Yeah. Because the cost of not progressing might be far higher:

The loss of countless species in the wild whose habitats are being destroyed, while those of us with some skills, dreams and respect for the animals sit by idly -watching them perish, failing to even attempt captive husbandry and propagation for fear of criticism and failure from the masses. The opportunity to gain more insight about how some of these unusual aquatic habitats operate, just to name a few things.

Who knows what discoveries might be missed if we fail to persue our goals and try them in our aquariums?

We (and by “we” I mean every one of us in the hobby) should encourage fellow hobbyists who want to experiment and question conventional wisdom to follow their dreams. If someone has an idea- a theory, and some good basic hobby experience, there is certainly nothing wrong with that. Yes, there is the sad fact that some animals might be lost in the process. It sucks. It’s hard to reconcile that…and harder to stand by it when animals are dying.

I Get it. It sucks.

However, that may be the cost of progress.

And taking a position of "Absolutely not!" instead is not a good tradeoff.

Replace fear with work.

Criticism will always be there.

You don't have to run screaming into the night and abandon your idea because a few people tell you it can't work. And remember, it doesn't make it "unwise" or an act of "tempting fate" just because it's something no one has tried before, or if it cannot be done by a large number of hobbyists just yet.

Really.

Pushing the boundaries is hard. But doable.

It requires work. Discipline. Observation. Diligence.

Effort.

And understanding.

We all know that a glass or acrylic box in our living room is not Lake Tanganyika or The Orinoco River...But the laws which govern Nature in the wild govern Nature in the aquarium, too. Those are "absolutes" which are important to embrace and understand.

You need to understand the consequences of the choices you make in building and populating your aquarium. And you need to face your ideas' vulnerabilities and potential misunderstandings that may arise, head-on.

I know this from personal experience.

As one of the leading proponents (and arguably, one of the more visible and one of the freaking LOUDEST) of botanical-influenced natural aquarium keeping, I know that I have an obligation to the hobby community to provide correct information and clarification whenever possible, and to advise when I think something that's bandied about might be incorrect.

And, when these incorrect assumptions are becoming "fact" in our discussions, we do need to address them from time to time.

Of course, one of the best ways to "keep it real" and address this kind of stuff is simply...to tell it like it is! All the time. And if we aren't sure about something that we're working on- don't have all of the answers-we can say it. It's okay.

It's an exciting, evolving time in the hobby, breaking new ideas out of the shadows of misconception and obscurity. Going beyond just the more superficial aspects of things in the hobby. We as hobbyists need to get better and better at sharing actual experiences with this stuff, rather than simply "regurgitating" second-hand information and throwing up roadblocks, as is so common in the hobby these days.

We need to keep doing what we're doing.

Like everything else, this type of evolution takes time. It takes patience. It takes understanding...and lots of sharing of firsthand information.

Are you up for it?

I think you are.

Stay tenacious. Stay diligent. Stay bold. Stay observant. Stay original...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

It's about the microbiome...

As we've all started to figure out by now, our botanical-influenced aquariums are a lot more of a little slice of Nature that you're recreating in your home then they are just a "pet-holding container."

The botanical-style aquarium is a microcosm which depends upon botanical materials to impact the environment.

This microcosm consists of a myriad of life format all levels and all sizes, ranging from our fishes, to small crustaceans, worms, and countless microorganisms. These little guys, the bacteria and Paramecium and the like, comprise what is known as the "microbiome" of our aquariums.

A "microbiome", by definition, is defined as "...a community of microorganisms (such as bacteria, fungi, and viruses) that inhabit a particular environment." (according to Merriam-Webster)

Now, sure, every aquarium has a microbiome to a certain extent:

We have the beneficial bacteria which facilitate the nitrogen cycle, and play an indespensible role in the function of our little worlds. The botanical-style aquarium is no different; in fact, this is where I start wondering...It's the place where my basic high school and college elective-course biology falls away, and you get into more complex aspects of aquatic ecology in aquariums.

Yet, it's important to at least understand this concept as it can relate to aquariums. It's worth doing a bit of research and pondering. It'll educate you, challenge you, and make you a better overall aquarist. In this little blog, we can't possibly cover every aspect of this- but we can touch on a few broad points that are really fascinating and impactful.

So much of this proces-and our understanding starts with...botanicals.

With botanicals breaking down in the aquarium as a result of the growth of fungi and microorganisms, I can't help but wonder if they perform, to some extent, a role in the management-or enhancement-of the nitrogen cycle.

Yeah, you understand the nitrogen cycle, right?

How do botanicals impact this process? Or, more specifically, the microorganisms that they serve?

In other words, does having a bunch of leaves and other botanical materials in the aquarium foster a larger population of these valuable organisms, capable of processing organics- thus creating a more stable, robust biological filtration capacity in the aquarium?

I believe that they do.

With a matrix of materials present, do the bacteria (and their biofilms- as we've discussed a number of times here) have not only a "substrate" upon which to attach and colonize, but an "on board" food source which they can utilize as needed?

Facultative bacteria, adaptable organisms which can use either dissolved oxygen or oxygen obtained from food materials such as sulfate or nitrate ions, would also be capable of switching to fermentationor anaerobic respiration if oxygen is absent.

Hmm...fermentation.

Well, that's likely another topic for another time. Let's focus on some of the other more "practical" aspects of this "biome" thing.

Like...food production for our fishes.

In the case of our fave aquatic habitats, like streams, ponds, and inundated forests, epiphytes, like biofilms and fungal mats are abundant, and many fishes will spend large amounts of time foraging the "biocover" on tree trunks, branches, leaves, and other botanical materials.

The biocover consists of stuff like algae, biofilms, and fungi. It provides sustenance for a large number of fishes all types.

And of course, what happens in Nature also happens the aquarium- if we allow it to, right? And it can function in much the same way?

Yeah.

I am of the opinion that a botanical-style aquarium, complete with its decomposing leaves and seed pods, can serve as a sort of "buffet" for many fishes- even those who's primary food sources are known to be things like insects and worms and such. Detritus and the microorganisms within it can provide an excellent supplemental food source for our fishes!

Sustenence...from the microbiome.

It's well known that in many habitats, like inundated forests, etc., fishes will adjust their feeding strategies to utilize the available food sources at different times of the year, such as the "dry season", etc.

And it's also known that many fish fry feed actively on bacteria and fungi in these habitats...So I suggest once again that a botanical-style aquarium could be an excellent sort of "nursery" for many fish and shrimp species!

Again, it's that idea about the "functional aesthetics" of the, botanical-style aquariums. The idea which acknowledges the fact that the botanicals we use not only look cool, but they provide an important function (supplemental food production) as well. As we repeat constantly, the "look" is a collateral benefit of the function.

This is a profoundly important idea.

Perhaps arcane to some- but certainly not insignificant.

And of course, we've talked before about this "botanical nursery" concept- creating an aquarium for fish fry that has a large quantity of decomposing botanicals and leaves to foster the production of these materials, which serve as supplemental food for your fish fry. I have done this before myself and can attest to its viability. You fishes will have a constant supply of "natural" foods to supplement what you are feeding them in the early phases of their life.

Learn to make peace with your detritus! As always, look to the wild aquatic habitats of the world for an example of how this food source functions within the greater biome.

I'm fascinated by the "mental adjustments" that we need to make to accept the aesthetic and the processes of natural decay, fungal growth, the appearance of biofilms, and how these affect what's occurring in the aquarium. It's all a complex synergy of life and aesthetic.

And, in order to make the mental shifts which make this all work, we we have to accept Nature's input here.

Understand that, when we create a botanical-filled aquarium, not only do we have the opportunity to create an aquarium which differs significantly from those in years past- we have a unique window into the natural world and the role of these materials in the wild.

One thing that's very unique about the botanical-style approach is that we tend to accept the idea of decomposing materials accumulating in our systems. We understand that they act, to a certain extent, as "fuel" for the micro and macrofauna which reside in the aquarium, and that they perform this function as long as they are present in the system.

A profound mental shift...

And it's all about the microbiome. today's simple idea with enormous impact!

Stay curious. Stay thoughtful. Stay observant. Stay diligent...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

The Bloom.

It's not magic...It's Nature.

As anyone who ventures down our tinted road knows, one of the great "inevitable" of utilizing botanicals in our aquariums is the appearance of biofilms. You know, those scuzzy, nasty-looking threads of goo, which make their appearance in our tanks shortly after immersion of the botanicals (much to the chagrin of many).

Biofilm.

Even the word conjures up an image of something that you really don't want in your tank. Something dirty, yucky...potentially detrimental to your aquarium's health.

It's not.

However, let's be honest with ourselves here. The damn dictionary definition is not gonna win over many "haters":

We've long maintained that the appearance of biofilms and fungi on your botanicals and wood are to be celebrated- not feared. They represent a burgeoning emergence of life -albeit in one of its lowest and most unpleasant-looking forms- and that's a really big deal.

Biofilms form when bacteria adhere to surfaces in some form of watery environment and begin to excrete a slimy, gluelike substance, consisting of sugars and other substances, that can stick to all kinds of materials, such as- well- in our case, botanicals. It starts with a few bacteria, taking advantage of the abundant and comfy surface area that leaves, seed pods, and even driftwood offer.

The "early adapters" put out the "welcome mat" for other bacteria by providing more diverse adhesion sites, such as a matrix of sugars that holds the biofilm together. Since some bacteria species are incapable of attaching to a surface on their own, they often anchor themselves to the matrix or directly to their friends who arrived at the party first.

Tannin's creative Director, Johnny Ciotti, calls this period of time when the biofilms emerge, and your tank starts coming alive "The Bloom"- a most appropriate term, and one that conjures up a beautiful image of Nature unfolding in our aquariums- your miniature aquatic ecosystem blossoming before your very eyes!

The real positive takeaway here: Biofilms are really a sign that things are working right in your aquarium! A visual indicator that natural processes are at work, helping forge your tank's ecosystem.

I recently had a discussion with our friend, Alex Franqui (the guy who designs our cool enamel pins). His beautiful Igarape-themed aquairum pictured above, is starting to "bloom", with the biofilms and sediments working together to create a stunning, very natural look. Alex is a hardcore aquascaper, and to see him marveling and rejoicing in the "bloom" of biofilms in his tank is remarkable.

He gets it.

And it turns out that our love of biofilms is truly shared by some people who really appreciate them as food...Shrimp hobbyists! Yup, these people (you know who you are!) go out of their way to cultivate and embrace biofilms and fungi as a food source for their shrimp.

They get it.

And this makes perfect sense, because they are abundant in Nature, particularly in habitats where shrimp naturally occur, which are typically filled with botanical materials, fallen tree trunks, and decomposing leaves...a perfect haunt for biofilm and fungal growth!

Nature celebrates "The Bloom", too.

There is something truly remarkable about natural processes playing out in our own aquariums, as they have done for eons in the wild.

Remember, it's all part of the game with a botanical-influenced aquarium. Understanding, accepting, and celebrating "The Bloom" is all part of that "mental shift" towards accepting and appreciating a more truly natural-looking, natural-functioning aquarium. The "price of admission", if you will- along with the tinted water, decomposing leaves, etc., the metaphorical "dues" you pay, which ultimately go hand-in-hand with the envious "ohhs and ahhs" of other hobbyists who admire your completed aquarium when they see it for the first time.

.