- Continue Shopping

- Your Cart is Empty

"Operating our aquariums...Replicating Nature"

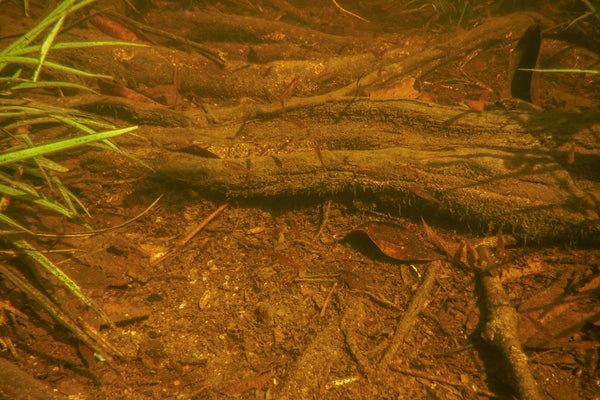

One of the real “frontiers” of the aquarium hobby is the practice of “operating” our tanks like the little microcosms that they are.

Attempting to replicate in our aquariums- on a number of levels- the processes and cycles which occur in Nature. We’re talking about things like seasonal weather cycles, water temperature, depth, nutrient levels, pH, current, photoperiod, food “pulsing”, etc.

Historically, hobbyists have been doing things like this to stimulate spawning in a wide variety of fishes over the years. This is really nothing new.

However, incorporating regular environmental manipulation for the routine maintenance of our fishes IS something a bit different. I'm not talking about "working" your tap water to achieve "blackwater" or "brackish" conditions in your aquarium. Rather, I'm suggesting that, once those "baseline" environmental parameters are set, that you "operate" your tank by trying to replicate some of the processes that we mentioned above.

And we're just scratching the surface here!

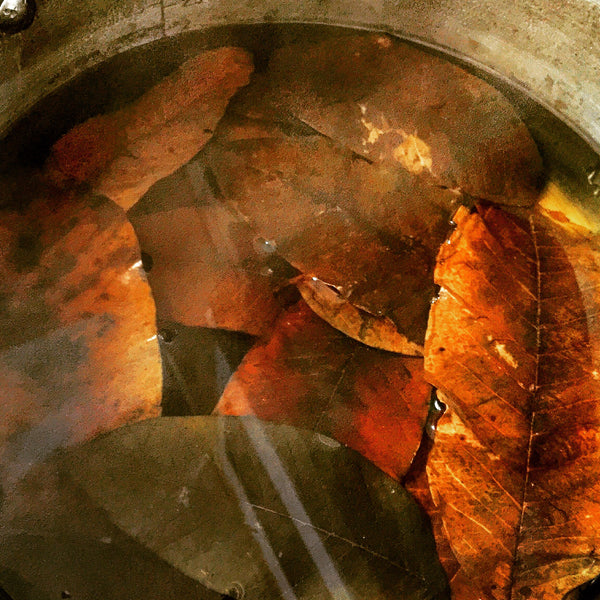

One easy "operation" that we can perform is the seasonal "pulsing" of leaves into our tanks. It's a process which can relatively easily simulate what occurs in Nature, when you think about it.

There is a more-or-less continuous "supply" of leaves falling off into the jungles and waterways in these habitats, which is why you'll see leaves at varying stages of decomposition in tropical streams. It's also why leaf litter banks may be almost "permanent" structures within some of these bodies of water!

And, for the fishes and other organisms which live in, around, and above the litter beds, there is a lot of potential food, which does vary somewhat between the "wet" and "dry" seasons and their accompanying water levels. The fishes tend to utilize the abundant mud, detritus, and epiphytic materials which accumulate in the leaf litter as food. During the dry seasons, when water levels are lower, this organic layer compensates for the shortage in other food resources.

During the higher water periods, there is a much greater amount of allochthonous input (remember that? I mean, on what other hobby-related site do they talk about THAT shit, huh?) from the surrounding terrestrial environment in the form of insects, fruits, and other plant material. I suppose that, in our aquariums, it's pretty much always the "wet season"in that regard, right?

We tend to top off and replace decomposing leaves and botanical more-or-less continuously, allowing materials to decompose and accumulate on top of one another. Very similar to what happens in Nature.

And it makes me wonder...

What if we stopped replacing leaves and even lowered water levels or decreased water exchanges in our tanks to correspond to, for example, the Amazonian dry season (June to December)...And if you consider that many fishes tend to spawn in the "dry" season, concentrating in the shallow waters, could this have implications for spawning our fishes?

I think it might.

In fact, I further proffer that we need to look a lot deeper into the idea of environmental manipulation for the purpose of getting our fishes to be healthier, more colorful. Now I know, the idea is nothing new on a "macro" level- we've been increasing and lowering temps in our aquariums, adjusting lighting levels, and tweaking stuff for a long time in attempts to breed them. That's kind of "Exhibit #1" in making the case that these types of processes work.

Killie keepers have played with this in drying and incubation periods in annual killifish eggs. However, I don't think we've been doing a lot of real hardcore manipulations...like adjusting water levels, increasing nutrient levels (ie; "pulsing" adding leaves and other botanicals), manipulating current, dissolved oxygen, food types, etc.

I think that there are so many different things that we can play with- and so many nuances that we can investigate and manipulate in our aquariums. What about the pulsing of leaf additions to correspond to the seasonal leaf drop?

I think that this could even add a new nuance to biotope aquarium simulation and the contest scene, such as creating an aquarium which simulates the actual functions- not just the "look"- of the "Preto da Eva River in Brazil in October", for example...with appropriate environmental conditions, such as water level, amounts of allochthonous material, etc. Show those hardcore contest biotope snobs what a real biotope aquarium is all about! 😆

The possibilities are endless here! And, as always, the aesthetics are a "collateral benefit" of the process.

So much to consider.

Of course, we're doing this stuff for a reason: To create more naturally-functioning, authentic-looking, aquatic displays for our fishes. To understand and acknowledge that our fishes and their very existence is influenced by the habitats in which they have evolved. To unravel the subtleties of the relationship between them on a deeper level.

Wild tropical aquatic habitats are influenced greatly by the surrounding geography and flora of their region, which in turn, have considerable influence upon the population of fishes which inhabit them, and their life cycle. The simple fact of the matter is, when we add botanical materials to an aquarium and accept what occurs as a result-regardless of wether our intent is just to create a different aesthetic, or perhaps something more, we are-to a very real extent-replicating the processes and influences that occur in wild aquatic habitats in Nature.

The presence of botanical materials such as leaves in these aquatic habitats is fundamental. They're part of Nature's "operating system."

In our little hobby sector, leaves are sort of the "gateway drug", if you will, into our world. Where you go from there depends upon what aspects of the "operating system" you're determined to play with!

The manipulation of other aspects of the aquarium environment, such as temperature, water current, and lighting is every bit as important as the the physical additions of botanical materials and leaves, when it comes to the impact that they have. Even factors such as "filling" a tank with more and more roots and other materials after it's "underway" is another simulation of Nature that we could play with.

Of course, even when "operating" our tanks, we need to deploy radical amounts of patience in our work.

Botanical-style aquariums typically require more time to evolve. This process can be "expedited" or manipulated a bit, bit to achieve truly meaningful and beneficial results, you just can't rush stuff!

You can't interrupt it, either.

When you do, as we've learned, results can be, well- "different" than they would be if you allow things to continue on at their own pace. Not necessarily "bad"- just not as good as what's possible if you relax and let Nature run Her course without interruption.

Patience is our guideline. Nature our inspiration. Experience and execution our teachers. We're on a mission...to share the benefits which can be gained by embracing and meeting Nature as She really is.

Give Her a chance. let's let Nature do her thing without interruption.

Trust me. She's awfully good at it.

In the confines of an aquarium, finding a "rhythm" that works for both us and our fishes is the key here. I mean, sure, if you want to really follow global weather patterns and do stepped-up water exchanges and botanical additions and removals to correspond with them, this would be a very cool experiment!

However, for most of us, simply establishing a routine of botanical additions and replenishment is a good idea. Removing them as they decompose, or leaving them in until they completely break down are both practices which form part of the "management"- the operating system- of our aquariums.

Change.

And consistency.

Working together in a most interesting way.

The more we look at Nature, the more we find that trying to model our aquariums aesthetically and functionally after Her processes is an amazing way to go!

And I think that our fishes will let us know, too...I mean, those "accidental" spawnings aren't really "accidental", right? They're an example of our fishes letting us know that what we've been providing them has been exactly what they needed.

It's worth considering, huh?

Stay creative. Stay observant. Stay diligent. Stay persistent. Stay patient...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

The Urban Igapo in practice...

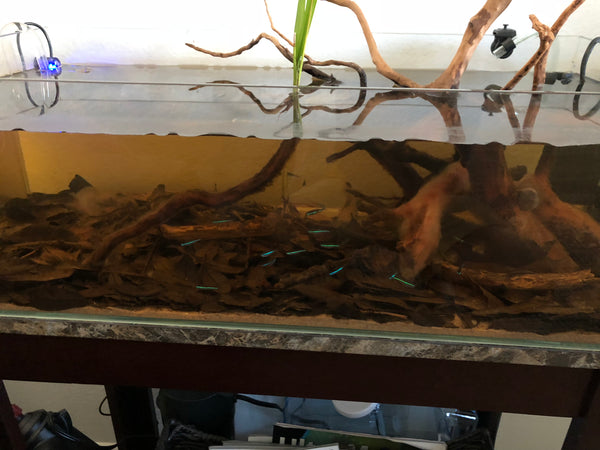

It's been about 4 years since we first presented our idea for replicating the flooded forests and meadows of South America (Igapo and Varzea).

In a fun homage to the hobby, we called the concept the "Urban Igapo." About 2 years ago, we went more in depth with some of the procedures and techniques that you'd want to incorporate into your executions of the idea.

Here are some answers to a few of the most common questions we receive on the idea.

Do I have to have a "dry season?"

Well, that's a good question! I mean, the whole idea of this particular approach is to replicate as faithfully as possible the seasonal wet/dry cycles which occur in these habitats. It starts with a dry or terrestrial environment, managed as such for an extended period of time, which is gradually flooded to simulate inundation which occurs when the rainy season commences and swollen rivers and streams overflow into the forest or grassland.

Sure, you can replicate the "wet season" only- absolutely. I've seen tons of tanks created by hobbyists to do this. However, if you want to replicate the seasonal cycle- the real magic of this approach- it's more fun to do the "dry season!"

Think of it in the context of what the aquatic environment is- a forest floor or grassland which has been flooded. If you develop the "hardscape" (gulp) for your tank with that it mind, it starts making more sense. What do you find on a forest floor or grassland habitat? Soil, leaf litter, twigs, seed pods, branches, grasses, and plants.

Just add water, right?

What size aquarium do you need?

You can use just about any size of aquarium. Most of my executions have been in smaller tanks (1-10 U.S. gallons). Of course, you can scale this up to medium and large aquariums. The concept is the same.The execution is the same. The biggest challenge, in my opinion, is embracing the fact that you might set up a large tank which may not have any fishes in it for months. Patience! It's a mental shift; a commitment to following though on an idea that is rather "alien" to most aquarists.

Does the grass and plants that you've grown in the "dry season" survive the inundation?

Another great question. Some do, some don't. (How's that for concise info!). I've played with grasses which are immersion tolerant, such as Paspalum. This stuff will "hang around" for a while while submerged for about a month and a half to two months, in my experience, before ultimately succumbing. Sometimes it comes back when the "dry season" returns. However, when it doesn't survive, it decomposes in the now aquatic substrate, and adds to the biological diversity by cultivating fungi and bacteria.

You can use many plants which are riparian in nature or capable of growing emmersed, such as my fave, Acorus, as well as all sorts of plants, from Hydrocotyle, Cryptocoryne, and others. These can, of course, survive the transition between aquatic and "terrestrial" environments.

How long does the "dry season" have to last?

Well, if you want to mimic one of these habitats in the most realistic manner possible, follow the exact wet and dry seasons as you'd encounter in the locale you're inspired by. Alternatively, I'd at least go 2 months "dry" to encourage a nice growth of grasses and plants prior to inundation.

And of course, you cans do this over and over again!

When you flood the tank, doesn't it make a cloudy mess? Does the water quality decline rapidly?

Sure, when you add water to what is essentially a terrestrial "planter box", you're going to get cloudiness, from the sediments and other materials present in the substrate. You will have clumps of grasses or other botanical materials likely floating around for a while.

Surprisingly, in my experience, the water quality stays remarkably good for aquatic life. Now, I'm not saying that it's all pristine and crystal clear; however, if you let things settle out a bit before adding fishes, the water clears up and a surprising amount of life (various microorganisms like Paramecium, bacteria, etc.) emerges. Curiously, I personally have NOT recorded ammonia or nitrite spikes following the inundation. That being said, you can and should test your water before adding fishes. You can also dose bacterial inoculants, like our own "Culture" or others, into the water to help.

Should I use a filter in the "wet season?"

You certainly can. I've gone both ways, using a small internal filter or sponge filter in some instances. I've also played with simply using an air stone. Most of the time, I don't use any filtration. I just conduct partial water exchanges like I would with any other tank- although I take care not to disturb the substrate too much if I can. When I scale up my "Urban Igapo" experiments to larger tanks (greater than 10 gallons), I will incorporate a filter.

What kinds of fishes can you keep in these systems?

I've played with a lot of different types of fishes. Particularly annual killifishes, small characins (like Red Phantom Tetras, Neons, and others), Gouramis, and Bettas. Lots of possibilities!

Okay, let's wrap this for today...A lot of orders to ship!

We will re-visit this topic again in the near future; it's becoming a very popular idea, and there are a lot more questions!

And we're excited to see it develop more!

Stay excited. Stay innovative. Stay curious. Stay observant. Stay patient...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tanni nAquatics

Behind the Botanical: There's something "fruity" about this one- Meet the "Calotropis Pod"

It's been a while since I've tackled one of our "Behind the Botanical" close-ups of some of the materials we play with in our tanks- so let's give it another go today!

As botanicals go, there are ones that are earthy-looking, durable, filled with tint-producing tannins, creating unique aesthetics in the aquarium, and there are others which are more appropriate for use as supplemental food, biofilm recruitment, etc..."environmental enrichment"; a more "utilitarian" application, if you will.

Our friend the Calotropis Pod definitely falls into this latter category. Unfortunately, it tends to get overlooked a lot. Much like the Dysoxylum pod, it's one of this botanicals that you're likely not going to add to your tank just to create a specific "look"; rather, it's one that will prove really popular if you keep ornamental shrimp or are looking to create a "botanical-style fry-rearing system." (we'll talk about that idea some other time!)

Hailing from the family Asclepiadaceae (say that 5 times fast!), Calotropis gigantea, is a unique-looking, almost "flower-petal-like" botanical is native to Southeast Asia- Malysia, Indonesia, Thailand, and Tamil Nadu, India, where our supplier is.

We call it a "pod", but it's actually the fruit of a large shrub, which is a form of...wait for it...Milkweed!

The Latifolia tree grows abundantly in the wild in dry deciduous forests in Bihar and Madhya Pradesh, India. The ripe fruit and seed kernel are eaten by humans in their native locales, specifically in India, where it is also known as "Chironjee" or "Cuddapah Almond." It's also used as a cooking spice, and in Ayurveda health, an aphrodisiac, and a "cardiac tonic"- although we advise to avoid ingesting this stuff! In some scientific studies, an extract of Latifolia seeds "stimulated both cell-mediated immunity and hormonal immunity in mice."

So, yeah- I'm not exactly certain what that means, but I believe it has some medicinal properties to it.

For humans. Don't get it twisted.

What I do know is that fish love them! (and shrimp, too...in fact- probably more than the fishes!) They pick at these pods relentlessly. These botanicals soften up nicely after preparation and submersion, and they provide not only some grazing surfaces, but an opportunity for biofilms and fungal growths to propagate as well.

So, what should you expect to happen with this botanical when it's submerged? Well, for one thing, it'll start softening and breaking down pretty quickly after it's submerged in your tank. This makes them very easy for fishes and/or shrimp to graze on them or even consume them directly. It may impart a bit of color to the water, too, because its derail layers DO have some tannins in them. However, the color that you should expect is not like what you'd see from leaves and such...

The Calotropis pod is, in my humble opinion, one of the best botanicals to use in your tank when you're interested in the "food production" part, because of its soft tissues, and easy accessibility for biofilm and fungal colonization. This is one that you aren't really going to use in large quantities to create some sort of "look." Rather, it's perhaps one of the more "functional" botanicals you can use!Mixed in with other materials, it's a really cool "accessory" for your botanical-style tank.

The Calotropis pod definitely represents the allochthonous input of materials from the terrestrial environment that find their way into the aquatic habitats we admire so much. And of course, the fishes will respond to them in the aquarium as they would in their wild environments...Like, fishes such as Pencilfish and various characins really seem to go crazy for these guys, picking at them continuously- apparently consuming not only the biofilms and fungal growth on their tissues, but the botanicals themselves.

A real "win" for us!

Preparation for this botanical is pretty straightforward- a boil or steep in boiling water for around 20-30 minutes (or whatever it takes to get them to sink), and three ready to go. Not exactly long-lasting in our tanks- but we're talking about a botanical which we're primarily using for supplemental food or food production, so it's a pretty good trade-off, right?

We think so!

You keep experimenting, and we'll keep searching for new and interesting botanical materials for a variety of purposes in our aquairums.

Until next time...

Stay curious. Stay resourceful. Stay creative. Stay innovative...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Challenge

Over the years here at Tannin, we've presented some of the work that we feel has pushed our hobby experience forward, challenged our skills, and questioned the status quo.

Here are a few ideas and their accompanying benefits that YOU can boldly run with and continue the work we started; take it to new levels and unlock some new secrets.

In no particular order:

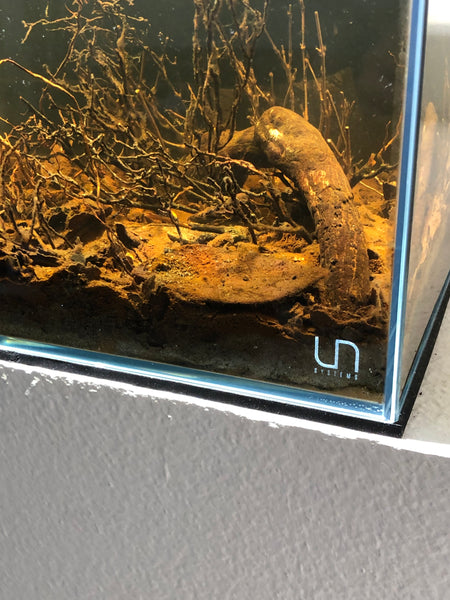

LEAF LITTER ONLY (LLO) AQUARIUMS

Things to explore: Supplemental/primary food production, denitrification/nutrient export, pH management, fish behavior and spawning, rearing of fry.

The idea here is really not all that complex! In fact, this approach is probably one of the easiest kinds of specialized tanks to create. You set up your aquarium with little to no substrate (if you're going to use substrate, we're talking 1/2"/1.27cm of sand), and add a layer of your fave leaves on top. We're talking anywhere from 1"/2.54cm- 6"/15.24cm deep.

And that's it. Nothing else.

Oh, sure, you could toss a piece of wood in there if you need some "vertical relief" for your aesthetic sensibilities. It's not mandatory, of course. It's purely an aesthetic thing, or perhaps it's something you might want if you're keeping skittish fishes.

However, the main idea is to make the leaf litter the whole "scape"- the entire habitat within the aquarium. In fact, it's less about the "look" than it is about the execution of a concept that can perhaps teach us a few things. By doing this, you're creating an aquarium which mimics the appearance and more important, much of the function of natural leaf litter habitats.

"Extra Credit"- Try "pre-stocking" your tank with organisms like Paramecium, Cyclops, Gammarus, Daphnia, and worms.

"URBAN IGAPO" (IGAPO/VARZEA SIMULATIONS)

Things to explore: Seasonal wet/dry cycles and their influence on fishes, the relationship between terrestrial and aquatic habitats, substrate composition, marginal plant and grass growth, food production

The amazing habitat and it's seasonal inundation cycle has been begging to be replicated in the aquarium for decades. In 2018, I decided to go for it.

In many of the regions of Amazonia, for example-the water levels in the rivers rise significantly during the rainy season often several meters, and the once dry forest floor fills with water from the torrential rain and overflowing rivers and streams.

The Igapos are formed.

Flooded forest floors.

The formerly terrestrial environment is transformed into an earthy, twisted, incredibly rich aquatic habitat, which fishes have evolved over eons to live in and utilize for food, protection, and spawning areas.

To replicate this process in the aquarium is really not difficult. It superficially mimics aspects of the "dry start" method that many aquatic plant enthusiasts play with. Except our goal isn't to start plants for a traditional aquarium. It's to replicate, on some levels, the year-round dynamic of the Amazonian forests.

It starts with a substrate which replicates the composition of the Igapo and Varzea soils of this region. (and yes, we offer them for sale...😆)

Add seed from terrestrial grasses to start the "cycle."

After a few weeks, the seeds should sprout. Once you have a nice growth of grasses, it's up to you as to when to bring on the inundation. At that point, just add water.

And of course, you can add fishes, too. I've experimented with small characins and annual South American killifishes! In fact, the concept lets itself very well to killies. When you're ready to bring on the "dry season again", you simply remove the water gradually. This replicates the desiccation which occurs as the rainy season fades. It's once again a terrestrial habitat.

In fact, in one of my "Varzea" simulations, I'm on my third generation of fishes derived from this wet/dry cycle! (Yes, I remove the adults when Im ready to drain the tank!)

I am personally going to scale this up to a larger (50 US gal) tank soon. There's a lot to learn here. But you have to be really patient, accept some unusual aesthetics, and be willing to do things way differently than you have in the past.

Things to explore: Impact on pH, fostering biofilms and fungal growths, supplemental "grazing" areas for fishes, spawning sites for cichlids and some characins, "nursery" area for fry, nutrient export processes.

they do in Nature.

The idea here is that the substrate becomes a dynamic part of the aquatic ecosystem. Over time, this stuff breaks down and becomes the perfect "microhabitat" for beneficial organisms, like crustaceans, fungal growth, worms, etc.

In other words, in a strictly aesthetic sense, the bottom itself becomes a big part of the aesthetic focus of the aquarium, with the botanicals placed upon the substrate- or, in some cases, becoming the substrate! These materials form an attractive, texturally varied "micro-scape" of their own, creating color, interest, and functions that we are just starting to appreciate.

And the botanical materials in the substrate act, to a certain extent, as "fuel" for the micro and macrofauna which reside in the aquarium, and that they perform this function as long as they are present in the system

Extra-credit- Another one to try pre-stocking with crustaceans and other microorganism cultures. A neat one to attempt spawning of egg-scattering fishes in...Will this matrix of material provide a "built-in" first food source for fry? Maybe?

Things to explore: Utilization of very rich substrate materials, decomposing leaf litter, live mangroves, simulation of food webs, alternative aesthetics.

Our focus is on trying to replicate and understand the complex web of life that occurs in brackish water habitats, and we've started to evolve the practice and appreciation of this unique niche just like we've all done with blackwater. In fact, the approach that we take to brackish is unlike what has previously been taken before, but one that is incredibly familiar to you as "tint enthusiasts."

And of course, there are a few components which, in our opinion, "power" the brackish water, botanical-style system: Mud, leaf litter...and mangroves. A more realistic and functional representation of this ecological niche.

And once again, it starts with the substrate. A richer, muddier, more sedimented material; one which fosters microbial life and decomposition of botanical materials. The idea being to help develop a "food web" which can provide supplemental nutrition for the fishes. One which will foster strong growth of mangroves.

Encouraging- rather than discouraging- leaf litter accumulation and it's resulting detritus is something that we feels sets this approach apart from the sterile "grey/white sand and rock" approach which has been proffered for decades.

As in- not your father's brackish-water aquarium. It's not about limestone rocks, quartz sand, and pieces of coral skeleton. Rather, we use combinations of fine sands, muds, leaf litter, and other materials to create a rich, dark, sediment-filled substrate. Possibly creating higher nutrient conditions than typically associated with brackish tanks, yet far closer in step with the rich estuary habitats we're interested in replicating.

Yeah, leaf litter. We all know a bit about that, huh?

And of course, the water will take on a tinted look in many cases, because of the leaves and mangrove bark which accumulate within the aquarium. The aesthetics are a radical departure from the conventional brackish tank- but the goal is, too. In this case, it's to foster a more dynamic ecosystem, to explore the unique relationship between substrate, plants, and water.

Applying the lessons we've learned in the freshwater botanical-style aquarium and using them in this different milieu is exciting and perhaps even a bit challenging. It requires mental shifts to embrace decomposition, detritus, etc. All things which can help us create a radically different type of brackish water aquarium than we have in the past.

Extra Credit- Creating "tidal shifts" via pumps and solenoids, growing intertidal salt-tolerant marginal plants, culturing shrimp and other crustaceans within the leaf litter bed, varying specific gravity over time to full-strength marine water, seagrass propagation (in marine water versions).

So, that's a few of the cool areas we as a community can work with. A few of the challenges we can take on. There are many, many more, of course.

There is so much interesting stuff out there to study and replicate in our aquariums. Not just to "diorama it up" to win a biotope aquarium contest; no- but to replicate the form and function of these unique habitats. I say this over and over and over again, because it's a completely different mindset.

I think we need to spend much more time really trying to get our hands around why natural habitats are the way they are. To understand why they formed, how they "operate", and what set of unique characteristics they possess which makes them home to our fishes.

Trying these alternative approaches and ideas- taking on the challenges- will only serve to advance our skills, benefit the hobby at larger, and help us as a community stay at the bleeding edge of aquarium practice for years to come.

What challenges will you take on in 2021?

Stay brave. Stay creative. Stay curious. Stay motivated...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Nature's got our back

The term "Nature" is really used a lot in the aquarium hobby. It's important that we recognize Nature as the ultimate inspiration for our tanks.

Nature, however, can be a rough place. The natural aquatic world doesn't take lightly to those who seek to edit it, parse it, or circumvent it.

It's true.

We know this, because when we try to "beat the system" by skipping a step, wishing things away, or ignoring Nature's "rules", bad outcomes usually follow.

But, here's the thing...

Even when we cheat; even when we take a shortcut; even when we fly in Her face- after the "ass kicking" - She's got our back...

For example, when you aggressively siphon your sand, interrupting Her process by removing the bulk of the detritus, biofilms, or other organics, not to mention the organisms which utilize them, there might be consequences like a temporary ammonia or nitrite spike.

However, after the spike, if you are patient, keep feeding your tank, and don't do anything stupid, like adding more fishes- your tank will recover. Beneficial bacteria and microorganisms populations will re-establish themselves.

Our aquariums are a lot more resilient than we give them credit for.

The passage of time and a "hands-off" approach to this recovery is crucial. Nature is oddly forgiving in this regard. We simply have to give Her the opportunity to continue on, as She has for eons, without our continued interference.

As we've mentioned repeatedly, Nature "does Her thing" regardless of what we think. Algal blooms appear because the conditions favoring their growth- light and nutrient loads, favor their establishment and growth. And they'll continue to do so as long as these factors remain in play. If we back off the light and continue regular nutrient export processes, at some point, the algae bloom will fade to a more "tolerable" level.

Now, sure- some of Nature's processes require us to make "mental shifts" to accommodate.

Biofilms and fungal growths- as objectionable in appearance though they may be to us as aquarists- perform vital functions in Nature and in the aquairum. They are not only normal- they're beneficial. They are something that we have been indoctrinated to loathe; to fear.

Why? Largely because they look "yucky." Because they tear at our aesthetic sensibilities. They go against everything that we've been told is "healthy"- when the reality is that the appearance of these life forms is your confirmation from Nature that everything is functioning as it should.

We can benefit enormously as aquarists by embracing Nature in its most unedited, literal form.

And that is something that we understand is not appealing to everyone. And sort of "sticking it in everyone's face" and suggesting that a truly "natural" aquarium requires the acceptance of a very polarizing aesthetic certainly can turn off some people.

I do get it.

However, I see little downside to studying Nature as it is.

It's very important, IMHO, to at least have a cursory understanding of how these habitats have come to be; what function they perform for the piscine inhabitants who reside there, and why they look the way they do. Even if you simply despise the types of aquariums we love here!

Why?

Because in the process of learning about Nature as it is, and the uniqueness and fragility of the habitats we love, we become more attuned to the way aquatic ecosystems function, and the threats these wild systems face. And when we have a greater understanding of the habitats themselves, we have a greater understanding of how to replicate their form and function in the aquarium.

Simply copying exactly every beautiful aquarium you see here, or elsewhere online deprives us of the amazing opportunity to study and be inspired by the wonders of Nature as it is.

Nature. Unedited.

A confluence of terrestrial and aquatic elements, working together to create a unique and inspiring habitat. By selecting to replicate, at least on some level, an "unedited" interpretation of these habitats, we open up new aesthetic possibilities, foster breakthroughs in aquatic husbandry, and further the state of the art of the aquarium hobby.

Having a certain degree of faith in Nature is extremely important for us as hobbyists. Understanding that, as our botanical-style aquariums evolve, we can benefit by not panicking; not rushing to "fix" every little "bump in the road" which we encounter.

Sometimes, it's best to do nothing...To let Nature perform the correction Herself.

She's damn good at it!

Obviously, you need to obey all of the common best practices of aquarium management, in terms of nitrogen cycle management, water quality testing, nutrient export, etc. in a natural, botanical-style aquarium (blackwater or otherwise). However, you have to also apply a healthy dose of the above-referenced "emotional element" into your regimen as well!

Going with your feelings is not always such crazy notion. Learning to have faith in Nature and her work isn't so bad, either. Nature always finds a way, right? Nature can correct many of the problems we create in our aquariums.

We talk a ton about the "aquarium as a microcosm" thing.

And don't forget- although aquariums are closed ecosystems, they are still subject to Nature's rules and processes.

Remember, anything you add into an aquarium- wood, sand, botanicals, and of course- livestock- is part of the "bioload", and will impact the function and environment of your aquarium. Even materials like rock and substrate add to the chemical dance occurring in our aquariums and have their own set of impacts.

Nothing we add to our systems has no consequences -either good or bad- attached to it.

Aquariums are living, breathing entities. They are influenced by a large number of internal and external factors- just like the wild aquatic habitats which they represent. Giving them a certain amount of "space" to "be" is really important. Constant "tweaks" and "adjustments"- well-intentioned though they might be- are stressful for the miniature ecosystems we create.

Rapid, dramatic environmental shifts are never a good thing for any type of aquarium, and a system like we run, with lots of organic material present, is just as susceptible to "insults" from big, poorly thought-out moves as any other. Perhaps even more, because by its very nature, our style of aquarium is based upon lots of natural materials which impact the environment on multiple fronts.

We need to remember this.

We need to observe our systems keenly- test when we can, and always apply common sense to any move we make.

Nature's got our back- provided that we do our part.

there is no "plug and play" formula to follow- only procedure. Only recommendations for how to approach things. Only common sense and the wisdom gained by doing. We sound a bit repetitive at times; however, like so many things in aquarium-keeping, our "best practices" are few, simple and need to be repeated until they simply become habit:

1) Prepare all botanicals prior to adding them to your aquarium.

2) Add botanical materials slowly and gradually, assessing the impact on your aquarium environments and inhabitants.

3) Either remove botanical materials as they break down (if that's your aesthetic preference), or replace them when they reach a point where they are no longer providing the aesthetic and environmental conditions that you desire.

4) Observe your aquarium continuously.

Specifically, observe the changes that your aquarium goes through as it evolves into a little microcosm.

Do you really want to "prove" to yourself that Nature's got your back?

Leave your tank to "fend for itself" for a while.

How much more will things change by simply delaying water exchanges for several weeks? By not siphoning detritus at all? Will this really become some sort of problem? Or, will the bacteria, fungal growths, and other microorganisms and crustacean life living in our botanical substrates continue to do what they do- break down organic waste and reproduce?

Yeah, they will.

It's what Nature does.

I'm 100% convinced that a natural, botanical-style aquarium can better handle a period of "benign neglect" than almost any other type of aquarium can. systems...Not that you'd want to do this, mind you... Although, I tried it as a sort of "experiment." Yeah-I'm a fairly diligent/borderline obsessive maintenance guy. I love my weekly water exchanges. But I did it.

And my tank ran just fine.

And that shouldn't really be a surprise, when you think about it.

The natural, botanical-style botanical aquarium is sort of set up to replicate a habitat where all of this stuff is taking place already. Leaves, seed pods, etc. are more-or-less ephemeral in nature, and are constantly breaking down in these environments. Decomposition, accumulation of epiphytic growth, and colonization of various life forms is continuous.

And I think to myself often, "How strange is it that we spend so much concern, time, money, and effort trying to eradicate some of the very things which our fishes have embraced for eternity?"

And further, I can't help but consider what audacity we have as humans to feel the need to "edit" nature to fit our own aesthetic "sensibilities!"

Sure, we can't get every functional detail of Nature down- every single component of a food web- every biochemical interaction...the exact materials found in every tropical aquatic habitat- we interpret- but we can certainly go further, and continue to work with Nature, and employ a sense of "acceptance"- and awe-in our work.

Embrace Nature. Understand how our closed systems are still little "microcosms", subject to the rules laid down by the Universe. Realize that sometimes- more often than you might think- it's a good idea to "leave well enough alone!"

Because Nature's got our back.

Stay calm. Stay inspired. Stay open-minded. Stay bold...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

This is How I do It (Pt. 2)

So, apparently, my first "installment" of "This is How I do It" proved to be pretty popular. I have literally had non-stop emails and dm's from people asking for more. I guess I may as well continue, huh?

Yeah.

So, let's talk about how I use botanicals in MY tanks.

Not, which ones I use, although I can give you my two cents on that topic- but more on how I use them. How I prepare them, how many I tend to use, etc.

We can start with my thoughts on selection.

That's the "million dollar question", because it varies. I have personal tastes and ideas behind my selections. Many hobbyists choose specific botanicals because they offer shelter or hiding spaces for fishes, or help create spawning sites, foraging areas, etc., etc., etc. So, it's impossible for me to say that I use a specific botanical in every tank I play with.

Yeah, it varies.

Okay, here's one generality: Personally, I do like smaller botanicals in most of my tanks. I tend to select smaller ones, because they provide a sense of scale. Larger botanicals just look better in larger tanks, IMHO.

I like the smaller stuff, because it better fits most of the "themes" I play with. It fits the "scale" of the tanks I work with.

The other thing I typically tend to do is utilize a relatively small diversity of materials in any given tank. It's a personal preference thing based upon my tastes, but people ask a lot. So, for example, I may choose only one or two types of seed pods in a given tank.

Now, with leaf litter beds, I'm a big fan of diversity! In most of the leaf litter beds I've been to and seen in Nature, there is a fair amount of diversity. It's a good model for us.

Yet, there are certainly other times when a wide variety of stuff is important. It's part of the big idea, so I totally get this. It's subjective for sure. And, as is demonstrated by great aquascapers like our friend Cory Hopkins, it's beautiful to adeptly and beautifully blend many different materials into one cohesive scape.

And of course, in some of my scopes, like my "Igapo" and "Varzea" concepts, I will typically use a lot of different stuff.

And then there's the surprisingly "controversial" process of preparation. I get a lot of questions about this. Even after five years of trying to elevate the art and science, there's still confusion, misunderstanding, and even some "regurgitation" of "recommendations" proffered by people who have never even tried this stuff.

It's weird.

"Fellman, you're really into boiling and stepping them, huh?"

Yes. I am.

"Why do you do that?"

Botanicals and leaves are collected from various locations around the world; typically as naturally fallen and dried. When these materials fall on the ground, they can be exposed to stuff like spiders and their webs, bird droppings, dust, and good old-fashioned dirt.

Look, I'm big on utilizing all sorts of stuff in my tanks to foster biodiversity and bacterial growth, etc., but I don't want bird shit and spider webs in my tank! This is stuff which, in the confines of an aquarium, could introduce unwanted organisms and contribute to the degradation of the water quality.

So I give my botanicals a good rinse. Then I boil or steep them.

"Isn't that overkill?"

I don't think so.

Consider that boiling water is used as a method of making water potable by killing microbes that may be present. Most nasty microbes "check out" at temperatures greater than 60 °C (140 °F). For a high percentage of microbes, if water is maintained at 70 °C (158 °F) for ten minutes, many organisms are killed, but some are more resistant to heat and require one minute at the boiling point of water. (FYI the boiling point of water is 100 °C, or 212 °F)...But for the most part, most of the nasty bacteria that we don't want in either our tanks or our stomachs are eliminated by this simple process.

So, wouldn't it make sense to boil our botanicals before we dump them into our aquariums?

Yeah, it would.

Ten minutes of boiling is "golden", IMHO. Of course, we boil for other reasons, too-as we'll touch on now.

Boiling also serves to soften botanicals. Softening them helps them sink more quickly in our aquariums. No one seems to like a bunch of leaves and seed pods floating around, right?

If you remember your high school Botany (I actually do!), leaves, for example, are surprisingly complex structures, with multiple layers designed to reject pollutants, facilitate gas exchange, drive photosynthesis, and store sugars for the benefit of the plant on which they're found.

As such, it's important to get them to release some of the materials which might be bound up in the epidermis (outer layers) of the leaf. Boiling or steeping facilitates this. As we get deeper into the structure of a leaf, we find the mesophyll, a layer of tissue in which much of photosynthesis takes place.

We use only dried leaves in our botanical style aquariums, because these leaves from deciduous trees, which naturally fall off the trees in seasons of inclement weather, have lost most of their chlorophyll and sugars contained within the leaf structures. This is important, because having these compounds present, as in living leaves, contributes excessively to the bioload of the aquarium when submerged...

Personally, I feel that we have enough bioload going into our tanks, so why add to it by using freshly-fallen leaves with their sugars and such still largely present, right? Although- I think I'll experiment with various "fresh" leaves down the road to see what happens in certain circumstances.

Are there variations on this prep theme?

Well, sure. Of course!

Many hobbyists rinse, then steep their leaves in boiling water, rather than a prolonged boil, for the simple fact that exposure to the newly-boiled water will accomplish the potential "kill" of unwanted organisms, which at the same time softening the leaves by permeating the outer tissues. This way, not only will the "softened" leaves "go to work" right away, releasing the beneficial tannins and humic substances bound up in their tissues, they will sink, too!

And of course, I know many who simply "rinse and drop", and that works for them, too! And, I have even played with "microwave boiling" some stuff (an idea forwarded on to me by Cory Hopkins!). It does work, and it makes your house smell pretty nice, too!

It's not a perfect science- this leaf preparation "thing."

And I admit, I've changed some of my approaches over the years...I'd be foolish not to.

And of course, one of the common followup questions I get is, "Doesn't all of this boiling and steeping release all of the tannins in the leaves and seed pods? Seems counter-productive to boil them!"

It isn't.

If you've played with leaves and botanicals long enough, you'll realize that botanical materials will continue to leach out some water-coloring tannins over an extended period of time- even after they were boiled or steeped. And my tanks are as deeply tinted as anyone else's that I know, trust me!

The amount of tint-producing tannins that you will lose as a result of preparation is insignificant, especially when you take into account the benefits realized by this process.

Final words on prep:

I do what I recommend.

Like so many things in our evolving "practice" of perfecting the botanical-style aquarium, developing, testing, and following some basic botanical preparation "protocols" is never a bad thing. And understanding some of the "hows and whys" of the process- and the reasons for embracing it-will hopefully instill into our community the necessity- and pleasures- of going slowly, taking the time, observing, tweaking, and evolving our "craft"- for the benefit of the entire aquarium community.

And the other question I receive from our community in regards to botanicals is do I leave them in until they completely decompose, or do I remove them?

I leave them in.

Decomposition is something to be embraced in the botanical-style aquarium world.

Decomposition is an amazing process by which Nature processes materials for use by the greater ecosystem. In Nature, it's the first part of the recycling of nutrients that were used by the plant from which the botanical material came from. When a botanical decays, it is broken down and converted into more simple organic forms, which become food for all kinds of organisms at the base of the ecosystem.

This is a dynamic, fascinating process- part of why we find the idea of a natural, botanical-style system so compelling.

Many of the organisms- from microbes to micro crustaceans to fungi- are almost never seen except by the most observant and keen-eyed hobbyist...but they're there- doing what they've done for eons. They work slowly and methodically over weeks and months, converting the botanical material into forms that are more readily assimilated by themselves and other aquatic organisms.

I am of the opinion that, when we remove partially decomposed botanicals from our systems, we're interrupting a process- denying these beneficial organisms access to their primary food sources. And, as we've discussed before, these organisms also serve as supplemental food sources for our fishes.

In our aquariums, we're just beginning to appreciate the real benefits of using leaves and botanicals. Not just for cool aesthetics or to "tint" the water- but to create truly natural, ecologically stable aquatic systems for the health and well-being of the fishes we love so much!

It's important to remember that leaves and such are simply not permanent additions to our 'scapes, and if we wish to enjoy them in their more "intact" forms, we will need to replace them as they start to break down.

This is not a bad thing.

For most of us- those of us who've made that mental shift- we let Nature dictate the evolution of our tanks. We understand that the processes of biofilm recruitment, fungal growth, and decomposition work on a timeline, and in a manner that is not entirely under our control.

So, yeah- there IS a lot to consider when utilizing botanical materials in your aquarium. It's far, far beyond the idea of just "dumping and praying" that has been an unfortunate "model" for how to utilize them in our aquariums for many years. It's more than just aesthetics alone...the "functional aesthetic" mindset- accepting the look and the biological processes which occur when terrestrial materials are added to our tanks is a fundamental shift in hobby thinking.

Until next time...

Stay informed. Stay curious. Stay diligent. Stay creative. Stay observant...

And Stay Wet.

Why it's okay to go slowly.

If there is one thing I have learned in a lifetime in the hobby, it's that you need to deploy massive amounts of patience for real, long-term success. Sure, you can take shortcuts, employ "hacks" or "workarounds" or whatever and speed stuff up a bit. Sometimes you can push too hard, and get from "Point A" to "Point C" without hitting "Point B"- but the results over the long term almost always are not quite as good as when you "slow your roll" a bit.

Sure, many will argue with this point.

And this isn't the first time we've talked about this stuff- and definitely will not be the last. Yet, it's so important- so fundamental to our practice-that it deserves mention yet again. When I see the questions we receive, and the questions asked on various online forums daily, which seem to question the need to understand processes and deploy patience when establishing botanical-style tanks, it's obvious that it needs to be reinforced from time to time.

Patience and allowing the space and time for our aquariums to "breathe" and "evolve", much like they do in Nature.

Yet, when we think about our aquariums and the processes which we employ to create them in this way, the parallels are striking, aren't they?

Let's examine these again, so we can illustrate this. The evolution of many aquatic habitats that we model goes something like this:

A tree falls in the (dry) forest.

Wind and gravity determine it's initial resting place (you play around with positioning your wood pieces until you get 'em where you want, and in a position that holds!).

Next, other materials, such as leaves and perhaps a few rocks become entrapped around the fallen tree or its branches (we set a few "anchor" pieces of hardscaping material into the tank).

Then, the rains come; streams overflow, and the once-dry forest floor becomes inundated (we fill the aquarium with water).

It starts to evolve. To come alive in a new way.

The action of water and rain help set the final position of the tree/branches, and wash more materials into the area influenced by the tree (we place more pieces of botanicals, rocks, leaves, etc. into place). The area settles a bit, with occasional influxes of new water from the initial rainfall (we make water chemistry tweaks as needed).

Fungi, bacteria, and insects begin to act upon the wood and botanicals which have collected in the water (kind of like what happens in our tanks, huh? Biofilms and fungal growths are beautiful...).

Gradually, the first fishes begin to follow the food and populate the area (we add our first fish selections based on our stocking plan...).

Okay, you get the idea. The stuff we do when we establish our aquariums mimics-on a surprising number of levels- the processes which occur as natural aquatic habitats evolve. It's not always a fast process.

And the thing we must deploy at all times in this process is patience.

"Radical patience!"

What's 'radical" about patience? Well, these days, it seems that we tend to celebrate "finished" more than the process to get there, which is, IMHO, kind of sad. So, apparently, patience has become a sort of radical departure from the "new normal" in then hobby. Ironically (?), the real "magic" and fascination- is the evolution of an aquarium ecosystem.

It's as much about common sense as anything, actually.

Yeah, common sense.

That is- not jumping right to "finished"...or trying to. Rather, it's about taking a bit of time- or even a long time- to allow your aquariums to "run in" and develop before pushing them along. To allow the population of the "supporting cast" of microorganisms to evolve and multiply. It's actually a surprisingly interesting time.

Just because your tank doesn't have fishes swimming around in it doesn't mean that it's not compelling or engaging. I mean, why are we always in such a hurry to get fishes in, everything set perfectly, and the tank "Instagram ready?"

I think it's because we have historically not celebrated the process of an aquarium establishing itself as a closed ecosystem.

If we make an effort to understand how aquatic systems establish themselves and function, we develop an appreciation for each and every step in the process, and how it will influence the overall "tempo" and ultimate success of the aquarium we are creating.

Suddenly, "speed" is secondary to process.

When we take the view that we are not just creating an aquatic display, but a simulation of a diverse, functioning habitat for a variety of aquatic life forms, we tend to look at it as much more of an evolving process than some sort of recipe- or a step-by-step "procedure" for getting somewhere.

Taking the time to consider, study, and savor each phase is such an amazing thing, and I'd like to think- that as students of this most compelling aquarium hobby niche, that we can appreciate the evolution as much as the "finished product" (if there ever is such a thing in the aquarium world).

It all starts with an idea...and continues with a little bit of a "waiting game..." and a belief in Nature; a trust in the natural processes which have guided our planet and its life forms for eons.

The appreciation of this process is a victory, in and of itself, isn't it? The journey- the process- is every bit as enjoyable as the destination, I should think.

In the botanical-style aquarium game, rushing stuff for the sake of "getting finished" or whatever is simply not advisable.

Here's why:

The way we have embraced the botanical-style aquarium, it's not just about achieving a certain "look." Now, yeah, we celebrate the "look" as much as anyone can. Yet, botanical-style tanks are not really a "style", they're a type of approach to creating and managing an aquarium. And what we need to celebrate is the creation- the "evolution" of a small microcosm, complete with the many life forms which encompass it.

This takes some time. Populations of these organisms can only grow and multiply as fast as the resources are available to them. Shortcuts really don't make much sense. Now sure, you can- and should- consider "jump starting" your miniature ecosystem with bacterial and microorganisms cultures, to help get these valuable organisms into the system as early as possible.

But you can't do this with the intention of "rushing" the process. It doesn't work that way.

It takes time.

The bacteria, fungi, and other organisms which serve to "process" botanicals and nutrients within our aquariums take a while to establish themselves. Much like establishing the nitrogen cycle itself, botanical-style aquariums require us to be patient while these secondary organisms arrive, grow, and multiply to sufficient populations capable of fulfilling this role within the closed ecosystem we are establishing.

The pace and duration of this process is dictated by the availability of numerous factors, including food resources, temperature, and perhaps- most important- our ability to keep our "hands off" during this time.

It's okay to go slowly.

In addition to allowing microorganism populations time to multiply the other benefit of patience when establishing a botanical-style aquarium is that it gives you time to "get in tune" with your aquarium- to observe it, understand its "baseline" operating parameters, and to make "tweaks" and "edits" to the equipment, hardscape, lighting, etc. A chance for you to get to know your new aquarium...A pretty exciting time, really.

And think about this concept which we discuss a lot around here:

As botanicals begin to break down in the aquarium, they themselves and the organisms which feed upon them become, in turn, supplemental food resources for the higher life forms- our fishes. Yeah, fish spend most of the waking hours of aquatic animals are devoted to acquiring food and reproducing, right? They need to have some food sources available to "hunt and graze" for.

That’s reality.

So why not think about this time while the tank is establishing itself as a time to help accommodate our your animals’ nutritional needs?

And in our world, that might mean allowing some breakdown of the botanicals, or time for wood or other botanicals to recruit some biofilms, fungi- even turf algae on their surfaces before adding the fishes to the aquarium.

That process- or the time frame it takes to establish. It can't be rushed.

The very process of creating a botanical-style aquarium lends itself to this "on board supplemental food production" concept. The establishment of a sort of "food web" that's pretty analogous to those found in Nature, right?

And it plays right into the work that we regularly do as botanical aquarium fans... Hardly a radical concept in our world; merely a simple "mental shift" that we can in the way we look at our typical way of establishing an aquarium.

Sure, short cuts are exciting...appealing, even- if we look at the whole goal as achieving some pre-ordained "checkpoint" in our aquarium's lifespan. However, we need to look at them for what they really are.

They are band aids, props…”hacks”, if you will.

But they are not the key to establishing a successful long-term-viable botanical-style aquarium. Ultimately, Nature, the ultimate "editor"- has to “approve” and work with any of the “boosts” we offer.

Nature dictates the pace.

We simply follow her lead.

We employ practices, such as preparation and placement of our botanicals- because they are measured steps on a long road.

We see that people come in to our little niche with some expectations of glorious finished products- achieving a certain "look", based on the tanks they see. Human nature, for sure. However, the best thing we can do for them-and their fishes- is to see that they succeed.

We love new tanks, just starting the journey, because we know how they progress if they are left to do what nature wants them to do. We understand as a community that it takes time. It takes patience. And that the evolution is the part of the experience that we can savor most of all…because it’s continuous.

Yet, in our little niche, we stress the aesthetics of the tank during the “evolution” as part of the function, too. We celebrate biofilms, brown water, and decomposition, not just for how they look- but for what they do- and what they mean to the establishment and function of our little closed ecosystems.

Tune out all of the noise and outside voices telling you to "level up" your tank. It's not a competition. It's a journey. A really, really long and enjoyable one, in which every phase is amazing. One that rushing through will never bring you the results- or satisfaction- that a deliberate, measured pace can.

And that's why it's okay to go slowly.

Stay observant. Stay studious. Stay excited. Stay engaged. Stay patient...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Fun with water chemistry, Pt. 1,500...

We talk about a lot of the environmental benefits of botanicals and leaves and stuff. I've went on and on and on about the way a bunch of botanical materials in your aquarium can help foster a diverse and vibrant "microbiome." I think that this ability to foster such a population of organisms within the aquarium may be the top benefit of this approach.

Nonetheless, we receive a lot of questions on various water chemistry topics. Stuff that, although less exciting to me, is important for us to have at least a rudimentary working knowledge of as we venture into the realm of lower pH and tinted water, right?

Admittedly, I've spent a lot less time talking about the chemical benefits of utilizing botanicals in our tanks. Largely, it's because my limited understanding of chemistry is far less than my limited understanding of biology! And it's hard to explain some of this stuff coherently with that "handicap."

Nonetheless, I have been able to do a fair amount of research on some chemistry topics related to our botanical-style aquarium obsession. There's a lot of good academic stuff out there, if you care to dig and study. Let's tackle a couple of topics which come up frequently in discussion with other botanical-style aquairum geeks...

Let's start with "humic substances", okay?

One of the buzzy "catch words" we use a lot is "humic substances." What exactly are those, and why should you even care about them?

I mean, you probably just want to sit back and watch your tank fro ma comfy perch, not ponder the mysteries of water chemistry, right? I can't say that I blame you, but it IS kind of cool to learn a bit about this stuff.

Let's get to it really quickly, and you can get back to your coffee...

"Humic substances" are produced by biodegradation of plant and/or animal materials. Does that include botanicals and leaves? From everything I can find, it does.

Typical humic substances fall into three categories: humic acids, fulvic acids, and Humin (carbon-based "macromolecular substances" found in soils). I know, your head is already spinning. Interestingly, humic acids are insoluble in water with an acidic pH. Fulvic acids, on the other hand, which are also derived from humic substances, are soluable in water under a wide range of pH levels.

Confused yet?

I am. But that's really nothing new...

Up until the last decade, science considered any influence of humic substances on aquatic life as “anecdotal”. However, a lot of research conducted within the last decade or so has demonstrated that humic substances have an important direct physiological influence on aquatic life, including of course, fishes! In extreme blackwater conditions, they are known to be what makes it possible for fishes to survive in pH as low as 3.9!

In less extreme conditions, we are just now beginning to understand the role they play. However, they have been documented to play a major role in the functionality of a fish’s immune system, influence growth, improve lifespan, prevention of oxidative DNA damage, detoxification of heavy metals and organic pollutants, suppression of cyanobacteria, regulation of gill function, protection of fish from environmental physiological stress (low oxygen levels, temperature swings, pH shifts, TDS changes, Ammonia, Nitrite, etc…) and faster recovery from these environmental stressors.

Humic substances have also proven to possess antifungal, antiparastic, and antibacterial properties, inhibiting the growth of nasties, like Aeromonas hydrophila, A. sobria, and Escherichia coli, just to name drop a few.

You can do a lot more research on this stuff if you're willing to dig a bit. I do recommend that, if you're interested.

Another question we get a lot is about the "water-softening capability of botanicals", to which I respond almost reflexively, "There is none." However, it is known that our old and controversial friend, peat moss, has demonstrated some capacity to conduct ion exchange ( a process in which which unwanted dissolved ions in water are exchanged for other ions with a similar charge.) Ions are atoms or molecules containing a total number of electrons that are not equal to the total number of protons.

Peat softens water by exchanging humic acids for magnesium and calcium.

It's actually true.

Peat effectively binds calcium and magnesium ions, while simultaneously releasing tannic and other acids into the water. These acids "work" the bicarbonates in the water, reducing the carbonate hardness and pH to some extent. And it will tint the water, as well!

Interesting, right? However, you can't just drop some peat into your tank and expect "Instant Amazon." This process requires "active peat filtration" (the water passing over over the peat itself) to make this happen.

Now, of course, being the curious and occasionally reckless fish geek that I am, I played around with this idea once, to try to see if this does, indeed work.

And, well, it does sort of work.

It took a shitload of peat and a fair amount of time to reduce my Los Angeles tap water, with hardness exceeding ~240ppm and ph of 8.4 down to "workable parameters" of 6.4ph and a hardness level of around 40ppm. How much are we talking? It took a full 2-cubic-foot bag of peat, added to a 30-gallon plastic trash can, filled with with my tap water, over 8 days in order to achieve these parameters.

So, yeah. The idea does work. Is it efficient?

Um, not in my humble opinion.

By comparison, my SpectraPure 4 stage RO/DI unit cranks out 80+ gallons of zero TDS, zero carbonate hardness water in a day. Now, one could argue that the rejection rate of RO/DI makes it less efficient- but hell, I water my garden with the reject water! And yeah, a unit like mine retails for around $300 plus USD, more than a 2-cubic foot bag of peat, but the long-term, consistent efficiency and reliability is pretty obvious to me. All in all, for maximum efficiency, consistency, and control, just invest in an RO/DI unit and you'll create soft water with little effort and no mess.

Yeah, it IS a bit pricy to purchase an RO/DI unit, but well worth it.

But yes, you CAN soften water with peat to some extent if you're put to it, have the means to do it, and test. I've long ago lost that thrill that some people get from these types of "money-saving DIY" methods. To me, I simply decided to forgo other indulgences, save my money for a while, and invest in the RO/DI unit and call it a day.

You should, too.

Okay, well that's a quick summary on a couple of "water chemistry" topics that come up frequently around here. No doubt, as we have in the past, we'll continue to tackle others.

We welcome your stories, input, and suggestions in this wide-open, yet well-trodden arena within the hobby.

In the mean time, I'm going to expend more effort on studying decomposing leaves, sediments, and the microbiome they support...'cause I'm that kind of geek. (Besides, it's a bit more exciting to me, lol 😆)

Stay engaged. Stay experimental. Stay curious. Stay bold...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

This is how I do it. Part I: Substrates.

Okay, this is likely the most literal title to any blog I've ver written. Yet, it occurred to me that in over 5 years of writing "The Tint" blog and doing the podcast, I've never had a piece about how I would start a botanical-style aquairum from scratch. If I had a dollar for every time I have been asked what my personal approach to this stuff is..well- you get the idea!

Now, look, there are as many ways to start the type of aquarium as there are aquarists, and I've varied my "techniques" over the years. The focus here will simply be on my fave way to start a botanical-syle aquairum; an approach that, despite all of my experimental "detours", I keep migrating back to again and again- because it works for ME.

This is not the "ultimate guide" to starting a botanical-style tank. The entire body of work on "The Tint" is your guide if you want it...And of my "life's work" on the topic, really, lol. Rather, this is a more concise bit on how I start most of my botanical-style aquairums. Not the more specialized "Urban Igapo" approach, or brackish, or any of the other weird ideas we toss around here...Just a good, "old-fashioned" botanical-style aquarium.

We could go into insane detail on every aspect of my approach- and likely have in the past, and will again- in this blog/podcast! Let's just keep it kind of concise and simple today! We'll start with soem of the components of a botanical-style tank and how I approach it.

Now, sure, because it's what I use, I might drop some "Tannin brand" products or mention various botanicals or leaves that we carry. Of course, you can collect your own stuff, or purchase from other vendors or guys on e-Bay or whatever (I mean, really...why would you? I give you the ideas- and they get your business? How DO you sleep at night?😆).

So, let's get to it.

First off, a word on tanks.

It starts with the type of aquarium you're using. Duh. I mean, You can use any sized tank you want. Lately, I've been relegated to "nano-sized" tanks (10 U.S. gallons or less) because of my home renovation, but typically, I like 40-50 gallon tanks when possible. I like the size, scale, and of course, the stability that they afford. But yeah- regardless of if you're starting with a 2-gallon tank or a 200-gallon tank, I'd recommend pretty much the same approach. Seriously.

My approach starts with the bottom. Literally. Let's go to that.

You have many ways to go when selecting substrates these days. The way I see it, you have four general choices:

"Traditional Sands": My go to's? I have a few...Fine white silica, CaribSea "Sunset Gold" or CaribSea "Crystal RIver", all of which mimic, in a very accurate manner, the look and texture of the substrates you see in many tropical aquatic ecosystems. They're clean, high quality substrates that can be used in all sorts of tanks.

I would certainly rinse these materials thoroughly, per the manufacturer's recommendations. No mystery there, right? And then, you simply add whatever botanical materials you want to use right on top.

"Sedimented Substrates": Yeah, that'd be ours. NatureBase "Igapo", "Varzea", and the upcoming "Mangal" are examples of substrates which have a lot of sediments and clays in their formulation. These substrates realistically replicate the composition, function, and look of soils which are found in many tropical aquatic habitats.

In fact, most of our NatureBase substrates have a significant percentage of clays and sediments in their formulations. These materials have typically been something that aquarists have avoided, because they will cloud the water for a while, and often impart a bit of color. Like, that's a problem? We also have some botanical components in a few of our substrates, because they are intended to be "terrestrial" substrates for a while before being flooded...and when this stuff is first wetted, some of it will float. And that means that you're going to have to net it out, or let your filter take it out.

You simply won't have that "issue" with your typical bag of aquarium sand!

You can mix them with any of the above-mentioned commercially-available sands, or use them alone. You can gradually add water (as in our "Urban Igapo" concept), or simply fill your tank form day one. Expect significant cloudiness for several days as the materials settle out, though. Don't rinse these substrates...just put them to work right away.

Now, although you can (and should) play with these substrates "wet" from the start, I'd be remiss if I didn't remind you again that the igapo and varzea substrates were initially intended to be "terrestrial" for a period of time, to get the grasses and plants going, and then inundated.

So, yeah, you'll have to make a mental shift to appreciate a different look and function. And many hobbyists simply can't handle that. We're being up front with this stuff, to ward off the, "I added NatureBase to my tank and it looks like a cloudy mess! This stuff is SHIT!" type of emails that inevitably come when people don't read up first before they purchase the stuff.

"Fusion Substrates": This is a fun approach, too! Mix crushed leaves, twigs, botanicals, "used" material from "Shade" "Substrato Fino" or "Fundo Tropical" with sand or NatureBase materials to create your own dynamic, botanical substrates.

The possibilities here are endless.

In my experience, and in the reported experiences from hundreds of aquarists who play with botanical materials breaking down in and on their aquariums' substrates, undetectable nitrate and phosphate levels are typical for this kind of system. When combined with good overall husbandry, it makes for incredibly stable systems.

I've been thinking through further refinements of the "deep botanical bed"/sand substrate relationship. I've been spending a lot of time researching natural aquatic systems and contemplating how we can translate some of this stuff into our closed system aquaria.

One of the most common questions we get about mixing stuff into the substrate is, "Doesn't this harbor dangerous hydrogen sulfide pockets when all of this stuff breaks down?"

Yeah, the big "bogeyman" that we all seem to zero in on in our "sum of all fears" scenarios is hydrogen sulfide, which results from bacterial breakdown of organic matter in the total absence of oxygen.

Let's think about this for just a second.

In a botanical bed with materials placed on the substrate, or loosely mixed into the top layers, will it all "pack down" enough to the point where there is a complete lack of oxygen and we develop a significant amount of this reviled compound in our tanks? I think that we're more likely to see some oxygen in this layer of materials, and I can't help but speculate- and yeah, it IS just speculation- that actual de-nitirifcation (nitrate reduction), which lowers nitrates while producing free nitrogen, might actually be able to occur in a "deep botanical" bed.

And it's certainly possible to have denitrification without dangerous hydrogen sulfide levels. As long as even very small amounts of oxygen and nitrates can penetrate into the substrate, this will not become an issue for most systems. I have yet to see a botanical-style aquarium where the material has become so "compacted" as to appear to have no circulation whatsoever within the botanical layer.

Now, sure, I'm not a scientist, and I base this on close visual inspection of numerous aquariums, and the basic chemical tests I've run on my systems under a variety of circumstances. As one who has made it a point to keep my botanical-style aquariums in operation for very extended time frames, I think this is significant. The "bad" side effects we're talking about should manifest over these longer time frames...and they just haven't.

So, yeah, I personally am totally okay with that stuff.

"Alternative Substrates": An even more fun approach! No sand or sedimented stuff for you- just add a layer of leaves, twigs, or crushed botanicals. That's your whole substrate. This is perhaps, one of the coolest approaches you can take. Over time, this stuff breaks down and becomes the perfect "microhabitat" for beneficial organisms, like crustaceans, fungal growth, worms, etc.

In other words, in a strictly aesthetic sense, the bottom itself becomes a big part of the aesthetic focus of the aquarium, with the botanicals placed upon the substrate- or, in some cases, becoming the substrate! These materials form an attractive, texturally varied "micro-scape" of their own, creating color, interest, and functions that we are just starting to appreciate.

In fact, I dare say that one of the next "frontiers" in our niche would be an aquarium which is just substrate materials, without any "vertical relief" provide by wood or rocks. I've executed many aquariums based on this idea (specifically, with leaves), and I've been extremely happy with their long-term performance! Oh, and they kind of looked cool, too...

Always remember, the substrate is not just a thing you toss on the bottom of the tank, or some strictly decorative product. Rather, it's a habitat- a place where the extraordinary organisms which comprise the microbiome of our aquariums reside and multiply.

Now, one thing that's unique about the botanical-style approach is that we tend to accept the idea of decomposing materials accumulating in and among the substrates within our aquariums. We understand that botanical materials in the substrate act, to a certain extent, as "fuel" for the micro and macrofauna which reside in the aquarium, and that they perform this function as long as they are present in the system.

So, yeah, in summary- the substrate plays a huge role in the function of a botanical-style aquarium. We can create a "facility" with substrate materials which provides not only unique aesthetics- it provides priceless benefits: Production of supplemental nutrition for our fishes, and nutrient processing via a self-generating population of creatures that compliment, indeed, create the biodiversity in our systems on a more-or-less continuous basis.

True "functional aesthetics!"

Consider that the next time you think of tossing some sand into your aquarium and calling it a day! Make mental shifts.

This is "how I do it!"

Remember, the substrate you select is not just a decoration. It's part of a living, breathing biome, which provides incalculable benefits to the entire aquarium. And it's every bit as compelling as any other aspect of our hobby- the we look at it this way!

We'll keep going with this periodic "How I do it" series...A lot to cover, I think!

Stay creative. stay curious. Stay thoughtful. Stay innovative. Stay observant...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Literal interpretations...

Tinted, turbid water. Sediment, biofilm. Decomposing botanical materials. Soil. A random scattering of branches covered in fungal growth.

Stuff that has made aquarists' heads collectively spin for years. Stuff that is, by many hobbyists's standards, "sloppy, undesirable...even, gross!"

To me, it's freaking gorgeous. The idea of these things popping up and growing naturally in our tanks- as they do in Nature, is simply beyond anything I've ever seen intentionally done in any aquarium anywhere on planet Earth.

Unfiltered Nature. Powerful. Compelling. Raw. Real.

Okay, I'm not mentioning this to brag about how our seemingly avant-garde love of dirty, often chaotic-looking aquatic features in our tanks and in the wild makes us somehow cooler than the glassware loving, stupidly-named aquascaping stone crowd, or something like that. 😆 (well, possibly, but..)