- Continue Shopping

- Your Cart is Empty

"The evolution will be managed..."

One of the things that's so fun about the hobby is the ability to "tweak" and even "evolve" tanks intentionally as the years go by. Of course, it's not a "given" that you have to. Yet, I think that if you poll a random sample of hobbyists, almost every single one would want another aquarium!

Now, not everyone can have another aquarium, right?

Yeah.

For many hobbyists, their one aquarium is the only one they can have- at least for now, but possibly forever. Space, economics, time, etc, all come into play, and there really isn't much you can do except work with the one you've got. I mean, it's a blessing to have even one...but to the serious fish geek, that desire to move on to a greener pasture (or should we say, "browner river?")-to just taste some new stuff- seldom retreats.

It builds. Inspiration is everywhere.

Yeah, we want to shake things up. Try something different...I occasionally go through such moments. Entertain such thoughts. I can't escape it!

You know- like, "Scott, it's been a while since you've changed up the 'theme' of your tank...Maybe you need to do something different!"

Can you relate?

It's a bit weird for me, because I have generally had an obsession with NOT changing my tanks up constantly.

Of course, there is a bit of a contradiction: After starting Tannin Aquatics in 2015, I realized that, in order to "spread the gospel" about this emerging botanical method thing, I needed to show a lot of tanks. And of course, that means one of three things: Either I needed to set up a lot of new aquariums myself, recruit a lot of fellow hobbyists to create and share botanical method aquariums, or...I could "iterate" my existing tanks more frequently.

Yet, I still need to project patience; it's a fundamental part of what we do.

I think- think- that it's often challenged by my desire as the Tannin "mothership" and a need to showcase new ideas and botanicals. Well, maybe that's an excuse.

But hey, we all love to try new stuff, right?

I know that I do.

And it's funny, because I think that even though I fancy myself as this restless "conceptual guy" who is constantly evolving his ideas, the reality is that my "makeovers" are seldom that radical; rather, their little iterations that represent incremental changes or improvements over previous designs.

I tend to "stay in my lane", and not stray all that far from it.

I almost envy those of you who can make completely radical changes at the spur of the moment without regret, or a whole lot of consideration. Like, how do you do that?

I often wonder why I play with such a tight set of characteristics- you know, certain wood types and arrangements, use of botanicals of specific textures, colors, etc. Maybe it's just that I've found what works for me?

Although I'm definitely prone to "over-analyzing" stuff at times, it's fun now and then to step out of my own mind and look at stuff as if I'm a "third party" of sorts. Shake things up.

It's led to some pretty cool tanks over the years.

Maybe I have that sort of "comfort zone" that I tend not to push myself out too far from. I mean, I operate in a pretty radical "sector" already- the blackwater/ botanical-method. It's not everyone's cup of tea, being pretty different from the conventional, "clear water", highly stylized aquariums we all know so well. I realized a long term ago that, when I make changes to my tanks, they are always more like "iterations" of the existing design.

Radical changes aren't my thing, I suppose.

I have learned over the years to give stuff time and space to evolve on its own a bit, without my intervention.

I know enough to understand a fundamental truth about botanical-method aquariums:

The way the tank is looking right now is NOT how it will look in a few weeks, or months.

I play a really long game.

One which acknowledges that the fact that our botanical-method aquariums evolve over very long periods of time, not reaching the state that we perhaps envisioned for many months. My actions reflect this mindset. Unless there is some major emergency (which I have yet to encounter, btw), about the only thing that I might do is to add a few more botanicals.

Just sort of "evolving" the aquarium a bit; making up for stuff that might break down.

Minor, small moves, if any.

That being said, the biggest hurdle to me in making changes to aquariums has always been the psychological one. The "shame" that I assigned in my own mind if I simply broke down tanks and "recycled" them time and time again. That being said, I slowly (yeah, emphasis on slowly) came around to the idea that this is an effective way to demonstrate new ideas to our growing community.

All the while, I'm keeping in mind that the system will change on its own without any intervention on my part. It will "get where it's going" on its own time. Adding a few botanicals or leaves along the way is simply what you do to keep the process going. And it's extremely analogous to what happens in Nature, as new materials fall into waterways throughout the year, while existing materials are carried off by currents or decompose completely.

Yeah, just like Nature.

We're going to revisit the topic of "getting started" far more often here, following what are turning into "best practices" and tips to get your botanical-method/blackwater aquarium off to a good start as Nature evolves it. It's so important.

I mean, this philosophy makes a lot of sense, because botanical-method tanks, in my opinion, don't even really hit their "stride" for at least 3-6 months. Yet, in the content-driven, Instagram-fueled, postmodern aquarium world, I know that we tend to show new looks fairly often, to give you lots of ideas and inspiration to embark on your own journeys.

And I suppose, that's a very cool thing. Yet, it's likely a "double-edged sword." It might give you the wrong impression.

Like so many things in the social media universe, the representation of today's aquarium world likely gives the (incorrect) impression that these tanks are sort of "pop-ups", set up for a photography session and broken down quickly. We are, regrettably, likely contributors to some of this misconception.

Because we play a long game. A really long game. And the tanks we present to you in our images and videos are typically many months along.

So, what am I usually doing with my botanical method tanks?

I'm holding.

I'm just going to do the "scheduled" tweaks that were in my plan. Add some elements as I intended as the tank breaks in further. But nothing more. No big switches. No radical maneuvers. Why hold? I mean, after a tank has been up for a few weeks, now would be the time, if a tank isn't when're you want it, right?

It's because I have faith in Nature. I know that She'll push things along correctly- because that's what She does.

And I know that to intervene now- to "edit" Her moves-at the time when the tank isn't looking it's "best" to me, yet it's progressing ecologically and biologically- would be a shame. It would be akin to selling off a stock just before it "breaks out", or to unload a property just before the market takes off...

It'd be a shame.

Because "as sure as day follows night', if you've laid the correct groundwork to be successful, and if the tank is "checking off" all of the proverbial basic "boxes", the tank WILL get to where you want it.

Really.

Sure, as I say all the time, there are no guarantees when working with Nature. She can (and will at times) kick your ass, even when you did everything right! However, there is something else. Something more visceral that you can take comfort in:

Patience.

And a certain objective realization that things ARE going well with your tank. And that they just need more time in order to fully attain the vision you had...or even exceed it.

Of course, we can manage the evolution of our tanks- by letting them do their thing.

The "mental stretches" that we talk about incessantly here are still occurring for me, years into this game. With each pic I see of the natural habitats we want to emulate, and every beautiful aquarium that I see come to life from our community, it's inspiring, interesting, and engaging.

I'm seeing and experiencing new things, coming up with new ideas, and trying to understand and embrace the processes and aesthetics in a whole new light.

I am happy to see many of you doing the same.

Stay bold. Stay creative. Stay curious. Stay patient...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Compensating Factors.

For years, I've played with all sorts of rather unconventional aquarium ideas. Pretty much all of them were attempts to simulate, on some level, aspects of wild aquatic habitats which caught my fancy.

Stuff like functional representations of a varzea grassland, an igapo flooded forest, a muddy brackish mangrove estuary, a rice paddy, etc.

NOT set up to just "look like" the habitat- not a "biotope aquairum" in that I was trying to create a primarily aesthetic recreation of the habitat in question. Rather, a functional, sustainable aquatic display which captured the essence of these habitats, intended to operate for extended periods of time.

Over the long term, how do you create and manage a stagnant poool habitat? An African savanna mud hole for killies?

You use what I call “creative compensation.”

"Huh? What's that Fellman- another one of your goofy expressions?"

Well, likely. But it sums up my approach pretty well, actually!

Here's essentially what it means:

If you're going to create an aquarium which attempts to mimic the function of an environment which is challenging ing to manage, you need to compensate with techniques or equipment to do so.

See- not exactly earth-shattering, I know. But something a lot of hobbyists don't do when pondering their "bucket list" aquarium ideas. Sadly, many give up on them too easily, IMHO.

Yet, in many cases, you simply need to come up with a different mind set- to make a "mental shift" to create and manage a system like this. You CAN execute it...you just need to re-think what's important.

For example, when I developed my "Urban Igapo" idea, I knew that, in order to run the tank for an indefinite period of time, it would become necessary to step up water exchanges or other nutrient export mechanisms in lieu of filtration in the small tanks I was working with. I mean, sure, I could have run a power filter, small internal filter, or even a canister, but the risk of disturbing the substrate indefinitely was too great.

When you play along the fringes of what's considered "normal" or even "acceptable" in the hobby, you need to compensate in some other ways...like devising alternative nutrient export mechanisms, stepped-up water exchanges, etc.

Compensating factors.

Now, most of the "compensating factors" which we need to embrace are mental.

We've talked about them so much over the years that I almost sound like a cheap cliche of myself sometimes! Yet, it's true...we have to compensate by mentally shifting to understand what's going on in our tanks. This is really not that difficult to understand, right?

And then there are those other factors- attributes that we acquire in our aquairum work, such as patience.

Patience was something that I've accumulated over a lifetime of Fishkeeping. It wasn't just something that I had, mind you. Rather, I think that the attribute of patience really arose when I was a young fish geek, with only one tank, limited funds, and a lot of "wants!" I had to move slowly, plan, save, and simply be patient.

When you can only afford a few fishes at a time, you learn to be patient!

A compensating factor, for sure!

When we compare our aquariums and their function to what happens in natural aquatic habitats, the "compensations" that we need to make are very obvious.

Seems like just about everything we do in aquarium keeping invloves some sort of understanding. And some sort of "right of passage", or "barrier to entry" before you achieve exactly what you want to achieve, right?

You know, a challenge or "gauntlet" that you need to get through somehow before ultimately getting to where you want to be. Like, it starts out easy, but after a short period of time- there IT is..Waiting for you. That challenge. And there is only one way to go if you want to progress: Forward.

Time to throw down.

I see this with crystal clarity with the botanical method aquariums we espouse so much here:

A week or two after completing your setup and getting your prepared botanicals into your aquarium, there come the biofilms and fungal growths. Of course, these will grow at a rate which is a bit unpredictable, yet often peak and either pass in a relatively short time, or wane to a more "tolerable" level.

Knowing that it will always be present in your botanical-style aquarium is a real "right of passage" for everyone involved in this game- requiring an adjustment to our expectations- a mental shift.

You just have to understand what these growths are, and why they form. And celebrate them instead of simply fear them.

You begin to understand and appreciate the biofilms, fungal growths, and decomposition and what they mean to the ecology of a closed aquatic ecosystem. And then, you accept and indeed, celebrate- the progression and the many unique characteristics of botanical method systems.

Your viewpoint has changed.

You've "compensated" by understanding.

In our world, it means understanding that the stuff you're seeing in your aquarium- the stuff which might freak you out a bit- is exactly what you see in Nature.

You've made a mental shift that will equip you well to advance in your journey with this type of aquarium.

You've "crossed the mental barrier" and came out on the other side.

It's an achievement worth celebrating, isn't it?

Breaking through barriers is part of the game in this hobby.

Yeah, the shit you have to go through before you get exactly what you want. Not always fun. Not always "pretty" to many of you. Often times, challenging and perhaps, annoying, to say the least. Only those aquarists who "prove their mettle" by not shirking from the challenges, or calling it quits, reap the ultimate rewards.

Our botanical method aquarium world asks much from the hobbyist.

I totally get it.

It requires an understanding. Compensating.

An understanding that what we celebrate as beautiful here is dramatically different than ANYTHING that the rest of the aquarium world even sees as remotely tolerable: Tinted, turbid water, stringy biofilm growths, sediment and detritus...stuff that makes most hobbyists cringe even at the thought of it in their tanks.

We're not afraid, because we look beyond the simple appearance...and we understand the function and benefits of such characteristics in our aquariums- and how they are so prevalent in Nature, too.

I hit on this theme over and over and OVER again because it's absolutely fundamental to the botanical-method aquarium. We're simply dealing with aesthetics and functions that have been shunned, vilified, and reviled by hobbyists for decades.

And look, it's okay.

My goal isn't to convince the entire hobby that a tinted, turbid, biofilm-and-detritus filled tank is the ultimate in beauty. I get it...Most aquarists simply can't wrap their minds around that and accept it as gorgeous in any way. It makes sense.

Of course, it's also possible to embrace many of the elements of our types of aquariums while still accepting a more traditional look. It's not all about the earthy, over-the-top, in-your-face natural look you see me rant about so often here.

It simply involves compensating...

Stay curious. Stay bold. Stay enthusiastic. Stay excited. Stay diligent...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Inspiration.

Not long ago, I was perusing a hobby forum on “blackwater aquariums” , and an aquarist was asking for “inspiration” for an “Amazonian-themed blackwater flooded forest aquarium.”

Okay, that's always cool...Anything "Amazon-themed" or "flooded forest" always sort of catches my attention! And "blackwater" kind of gets to me...

And, predictably, a bunch of hobbyists chimed in to help- because hobbyists are kind that way. They shared photos of a variety of what they called “Amazonian- themed blackwater” aquariums, which, sadly, not only didn’t have “blackwater”type conditions- they bore almost no resemblance to any actual natural aquatic habitat- blackwater flooded forest, or otherwise.

Some of the responses were downright boastful and seemingly authoritative, with more than one literally stating that, "...this is how you should do it if you want this type of tank..." And, they looked like all of the other other "Amazon-Themed" tanks you see on social media...Superficial at best...downright inaccurate at the worst.

Yup.

The effort by most of the respondents was sincere, but the tragedy in all of this was that no one thought to share a single picture of a natural Aquatic habitat.

Or even a recommendation to search Google for one! Virtually any pic of a natural (blackwater) habitat would provide endless inspiration. At the very least, it would have opened up more discussions; perhaps led to some different questions. Questions which could have led to some shared experiences, greater understanding, and maybe- some new ideas on how to execute an aquarium representing this amazing habitat.

Yet, it turned into the usual regurgitated copy-fest of assorted aquariums, and discussion on how to replicate the look of them. It was disappointing enough that none of the tanks in the discussion remotely "looked" like the wild habitat the questioner was intrigued by- and even more disappointing that the discussion was about how to replicate the tanks-not the habitat!

Yeah, a desire to replicate the look of an aquarium purportedly based upon a natural habitat (which it didn't really resemble at all, in form or function)? Like, WTF?!

How does this happen?

I think that it's because we as a hobby are, well- lazy.

Seriously. I know that sounds harsh, but it's true, IMHO.

With few exceptions, most hobbyists generally don't make the effort to do their own research- or any research, for that matter, other than asking for pics of someone else's tank. It's a real tragedy, because with minimal effort, even the visuals of a natural ecosystem could provide cues and topics to further research that will help hobbyists really understand what they're contemplating!

Now, I realize that this can easily turn into another "grumpy 'ol Scott rant telling the neighborhood kids to get off his lawn", but that's not the point. And, I do realize that not everyone wants to create an aquarium filled with leaves and soil and decomposing muck, and that not every aquarium representing one of these habitats has to be that way. However, the greater issue is when our hobby understanding of these habitats is based wholy on someone's aquarium, which may bare little, if any resemblance to the actual environment it intends to "replicate."

Then what happens is that we perpetuate misinformation- even when unintended. We continue to push dumbed-down or superficial information about these habitats and the practices required if we truly want replicate them functionally, not just aesthetically. I mean, enjoy the hobby hope you want to- but don't perpetuate the bad information that's already out there in the process.

I think we need to spend way more time as hobbyists actually looking at Nature for our inspiration- not only for the “aesthetics”- but to study and understand the function. To learn about why these habitats function and look the way they do. It’s the “unlock”- the key to everything!

Look, you may love the way they look, respect and understand the function- and still choose to create a tank "inspired" by them. And that's perfectly okay. I do it all the time. My tanks don't precisely replicate many of the habitats they represent. I don't want try to manage a 4.3pH ecosystem, despite how accurate it may be. I do, however, understand these systems on some levels, and I certainly make the effort to learn about, and replicate when possible, the ecology where they occur.

But I don't defectors declare my tanks as the ultimate representation ration of a specific habitat.

Maybe I "pick and choose"what I care to work with- which a lot of us do. And that's fine.

What I don't do-what NONE of us should do- is make declarative statements about my way being "the best" way or the "only" way to do something, and I don't espouse that any other approach is incorrect or "wrong"- that's just being an asshole.

It doesn't help anyone.

It's perfectly fine to do whatever you want and call your work whatever- I mean, if your tank has 6 different species of fishes from the Amazon, it's decidedly an "Amazon-themed" tank, but to literally imply that your work is the epitome of accuracy is just absurd. It's NOT fine when you're dogmatically telling people that your tank something that it's not, and inferring that if they don't replicate your work, they somehow "not doing things correctly."

It's important for us to refer to research and information from outside of the aquarium hobby. Otherwise, this just becomes an echo chamber where we keep bouncing around the same assertions, regardless of accuracy. Google Scholar and other scientific research aggregator sites are really helpful- and you'd be surprised just how much stuff there is on the most arcane topics that you're trying to learn about. I can't begin to tell you how many times I've made use of these priceless resources for my work!

Now sure, some of this stuff is often dry, filled with academic language and references, and might be difficult for us non-scientist to follow...But if you persevere and stay at it, you can uncover some real gems that will help you in ways you might not have thought about. An example for me was a paper containing the orginal description and type locality of Tucanoichthys tucano; a paper which gave me the information which I needed to create what I would proudly call one of my finest and most iconic aquairums (jokingly referred to as the "Tucano Tangle"- but the name sorta stuck, lol).

I've made this plea before- but I think it's vitally important to go beyond what's "easy."

I realize that finding your info on YouTube is convenient, and that there are some great channels out there- but more often, it's filled with inaccuracies and even vacuous drivel. You need to do a few more "technical" searches to see what I mean. Trust me- once you find one of those hidden gems in scholarly articles- it'll change the way you get your information!

Yeah, inspiration comes from all sorts of sources.

Some of them are just a bit more "original" than others.

Seek them out. Learn from them. Be inspired by them.

Stay curious. Stay diligent. Stay excited...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

How soon is...NOW?

We hear a lot of discussions about establishing botanical method aquariums, yet a lot fewer ones about running them over extended periods of time. Occasionally, someone will ask me when a botanical method aquarium is considered "mature" or "finished."

Like, how do you know, and how long should you expect it to take to get there? When can you declare, "NOW the tank is "finished!"

We need to know, apparently.

Now, the question pre-supposes two facts:

1) That there is a quantifiable point where an aquarium can be labeled "finished."

2) That there is even a definition for what "mature" or "finished" means in the aquarium context.

Of course, part of the "need to know" is actually based upon that human construct of impatience. We need to have something "finished" and not "evolving" or "under construction." This always amuses me, because, in my opinion, an aquarium is never actually "done." It will continue to change and evolve as long as it's kept going by you, the hobbyist.

And that's a key point: An aquarium keeps evolving as long as we let it...

I believe that part of the need to quantify a tank as "finished" or even "mature" is because we constantly see "professional" aquascapers and content creators setting up tanks, photographing/videoing them, or entering them in a contest, and then breaking them down.

These aquariums definitely have an "expiration date"- and it's due to a single factor:

Human intervention.

It has seeped into the popular perception in the hobby because of the frequent changes in aquariums which many content producers (we're guilty of it, too..) we share in our social media accounts. You set up a tank, get it looking really cool, photograph it ...and then you break it down...and move on to the next one.

A sort of creative "churn."

So yeah...It's done! Ready for the next big idea!

I believe that this constant demonstration of "churning" tanks has "poisoned the well" when it comes to developing patient hobbyists.

My personal assertion is that an aquarium is never "finished", just as the natural aquatic ecosystems of the world are never "finished", unless outside intervention occurs.

Why can't a YouTuber or "Influencer" set up an aquarium, and document its journey from day one. Just let it evolve? I mean, you can still set up 35 different trendy tanks in the mean time...just keep documenting the one tank as a "proof of concept" that patience, time, Nature, and leaving the tank alone actually works!

I think that audiences can actually handle it.

There are plenty of daily "new looks" in every botanical method aquarium when you leave it alone, trust me. It's constantly evolving and changing...just like in Nature.

IMHO, there is a certain absurdity about the way we document our tanks, anyways. We fail to realize that what many "content creators" often do is to simply glam up their tanks for a video or contest, and then just let the thing go. At best, even a "contest scape" or a video or social media post of an"influencer's" tank only captures a moment in time. it will literally continue to change and evolve even seconds following the photos are taken or the video images are filmed!

Now, I realize that an "aquascape" in aquarium parlance is a human construct, and can be defined as "finished" when you are satisfied with the configuration you've created and stop "tweaking" it. In other words, the hardscape (wood or rocks) will not change its configuration or structure on its own!

But that's not the entire story, right?

Nope.

When you throw living, growing elements like aquatic plants, or materials which decompose, such as leaves and botanicals, into the mix, the appearance of the "aquascape" keeps changing, both aesthetically- and more important- ecologically.

This is precisely why I constantly reiterate the fact that a botanical method aquarium is interesting and beautiful at every phase of its existence!

To be perfectly honest, the beauty of a botanical method aquarium is that it's never really finished. Each day, each month- the aquarium will continue to evolve and change physically and ecologically- and will do so indefinitely.

That's why we preach patience so much in our world. Patience to watch your tank go though its developmental changes and evolutions- and the patience to understand and savor each phase of its development. Patience to NOT intervene or interfere with this process.

And an understanding that Nature is "at the controls" for a lot of it...and that it's okay for us to "get out of the way" and let Her do the job, as she has for millennia in the wild aquatic habitats of the world.

Nature manages to work with all sorts of materials, conditions, and constraints, and somehow always finds a way to continue to evolve them in ways that assure its survival over the long term. Our aquariums- although artificial contracts- are still beholden to natural laws and influences, and will contuse to do the same until such time as we decide to break them down.

On the other hand, if you look at an aquarium as you would a garden- an organic, living, evolving, growing entity- then the need to see the thing "finished" becomes much less important. Suddenly, much like a "road trip", the destination becomes less important than the journey. It's about the experiences gleaned along the way.

Enjoyment of the developments, the process.

When it comes to leaves and seed pods, some will simply last longer than others. All will contribute to the richness and diversity in their own way. Some replace others over time as the more "dominant" component of your natural "hardscape", wether fostered intentionally by you replacing stuff, or by natural decomposition changing a botanical into a different form, which newly added ones take over. All form a part of the whole, rich, ever-evolving picture.

This is why I never get freaked out about cloudy water, tons of fungal growth on my wood or leaves, or other processes which impact the aesthetics of my tanks early on in their life. Just wait a while, it'll change. And rather than be reviled by all of those stringy fungal growths, think about why they appear, what they're doing, and how you see the same exact thing in the wild aquatic habitats we love so much.

An appreciation of where you are sort of blunts the need to have a "finish line", in my opinion.

It makes sense when you consider it in that context. Sure.

Yet, people new to our little hobby sector still often ask me, "When will my tank start looking more "broken in'?", or, "When can I add more fishes?", or, "When will the tank look more established?"

My answer to these kinds of questions is always the same: It takes a while.

Botanical-method aquariums, like any other, require biological processes to establish and "mature" the system. This takes more than a week, or two weeks- or even a month. Honestly, if you asked me, you're talking three to four months before any aquarium- especially a botanical-method one- hits that "stride" of stability and the "look" that comes from a more mature, established system.

Three to four months.

Like, one full season.

Can you handle that?

I mean, it's really not that long, right? Especially when you take into account that you can maintain a botanical-method aquarium continuously for years.

And we're not in this just to create a "look." The reality is that many botanical method aquariums, which embrace stuff like sediments and decaying leaves and such, look "mature" very early on.

But that's not the whole game here, right? It's one thing to look mature, another for an aquarium to be ecologically stable and diverse.

You can get there easily, really.

It just requires patience, a long-term vision, and a focus on the goal of establishing a healthy, naturally-functioning system over the long term. You can't rush stuff. You simply can't. And you really don't want to, anyways. Let it evolve naturally.

Stay the course.

Be patient.

One day, you'll look at your tank, and think to yourself, "THIS is what I envisioned!" And you might casually glance at the calendar and note that, sure enough- it's been about 3-4 months since you established your tank.

Not all that long, right?

It was a pretty enjoyable ride along the way, wasn't it? Yeah, when you liberate yourself from some artificially self-imposed timetable about "when" things will look/feel good, it's a lot easier.

Yeah, we're talking about the appearance- but it's also about the function, right?

And it all comes back to understanding and embracing the fundamentals.

I firmly believe that understanding and appreciating the fundamentals of the hobby- and the natural world- can yield the same results- or better- than tons of expensive gear and "stuff" when simply "thrown" at the situation without thought as to why..

It requires us to shift our minds to places that might be less comfortable for us...

It just is a lot less sexy than "gearing up" or blindly following someone else's "rules"- it requires us to open our minds up...It requires patience, process and personal observation. It requires eschewing more "instant" result for long-term function, stability, and benefits.

That mental shift is something, isn't it?

Although the "I want the tank to be 'done' NOW!" mindset- although still highly visible and perpetuated by numerous vapid, moronic posts on social media is still top of mind to many, there are signs that the greater hobby is waking up to the fact that you can't have an "instant awesome" established, ecologically rich aquarium in a matter of days.

I think the pendulum in the hobby is swinging back a bit.

Not "digressing", mind you. Evolving; with hobbyists starting to grasp that anyone can create an amazing aquarium- it's just that it takes some understanding and process..and time. And realization that every stage of an aquariums evolution can be compelling.

And I can feel that many hobbyists are switching back to a more "accepting" approach; taking our hands off...just a bit, and letting Nature do what She does so well without our "editing." Once again realizing that Nature knows best. Understanding that we can use technology and technique to work with Nature.

We are learning that the journey- the evolution- of an aquarium is the whole game here. And that the "finish line" is really an artificial construct...a figment of our imaginations.

So, IS there even a "finish line" to an aquarium? Is an aquarium ever "finished?"

Only if we make it that way.

Nature won't stop.

You shouldn't, either.

Stay patient. Stay thoughtful. Stay bold. Stay diligent...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Living Color

The other day, in our Instagram feed, we received what I felt was one of the most honest, amazing comments I'd ever seen. The commenter was acknowledging that, while he loved the tinted water which botanical-method aquariums yield, he was having a bit of a mental struggle at the dark water hiding some of the subtle colors in his fishes. He loved the look, but was bummed out that his colorful fishes weren't as discernible in the deeply tinted water. He was sort of torn...He wanted to know if I ever had a similar feeling.

Besides just loving the incredible honesty, the comment did make me think a bit.

Now, I can honestly say that it never actually bothered me. In fact, I DID have to think a lot about it- but it was mainly for the reason that I couldn't think of a time when it did! I guess I always was drawn so much to the habitat, that any perceived loss of color was a non issue. I think that I'm also naturally attracted to fishes which, although can be colorful, generally have more muted patterns intended to help them blend into their environment.

However, I do agree that the tinted waters which result when we add leaves, seed pods, soils, etc, into our aquariums definitely impact the "visuals" of our fishes, don't they? Anyone who's ever tried to take a pic or video of his or her botanical method aquarium can attest to this. It's hard to get a good pic showing all of the accurate colors of some of your fishes.

On the other hand, some fishes seem to take on an entirely new appearance in tinted water, and the function of the coloration makes more sense in this context.

There is a reason as to why this is...

From a paper by researcher Shiro Kohima about the coloration of none other than the blackwater-dwelling Neon Tetra, the conclusion was pretty darned clear:

"To clarify the ecological function of this coloration, we examined the appearance of living neon tetra. They changed color in response to lighting and background conditions, and became less conspicuous under each condition to the human eye. Although they appeared bright in colorless clear water, their stripes appeared darker in blackwater. In addition, the visible area of their stripes was small and their brightness decreased, unless they were observed within a limited viewing angle (approximately 30° above the horizon).

The results show that from the viewpoint of approaching submerged predators, a bright mirror image of the stripes is projected onto the underside of the water’s surface, providing a dramatic visual target while the real fish remains less conspicuous. Based on these results, we hypothesize that the neon tetra’s bright coloration is an effective predator evasion strategy that confuses predators using bright mirror images."

Scientists are aware that dissolved organic materials, such as tannins and lignins, which visually tint the water, also absorb all wavelengths of light, yielding that brownish color that we know so well.

So, yeah, some of the more subtly-colored patterns on fishes will be more difficult to discern in tinted water. What can we do about that? Can we do anything about it?

Well, for one thing, we can adjust the lighting within our aquariums, and simply ramp up color and intensity. This is where modern LED lighting fixtures work so very well. You'll have to do some experimentation, but the versatility of LED's makes it easy!

Remember, all of this revolves around the properties of the water itself. Indeed, in our tanks, the water itself becomes a part of the attraction, doesn't it? And it becomes a consideration if you're trying to keep aquatic plants. You simply need to ramp up intensity to assist with light penetration, as we recently discussed right here on "The Tint."

One of the big discussion points we have in our world is about the color and "clarity" of the water in our botanical method aquariums. We receive a significant amount of correspondence from customers who are curious how much "stuff" it takes to color up their water.

This is so far from "mainstream" aquarium hobby thinking that I just have to laugh sometimes. I mean, those of us in the community of blackwater, botanical-method aquarists seek out tint and "body" in our water...while the rest of the aquatic world- well, they just sort of... freak the fuck out about that, huh?

And beyond just the color, there are other factors to the water which impact the "visuals", right?

Our aesthetic "upbringing" in the hobby seems to push us towards "crystal clear water", regardless of whether or not it's "tinted" or not. And think about it: You can have absolutely horrifically toxic levels of ammonia, dissolved heavy metals, etc. in water that is "invisible", and have perfectly beautiful parameters in water that is heavily tinted and even a bit turbid.

(FYI, WIkipedia defines "turbidity" in part as, "...the cloudiness or haziness of a fluid caused by large numbers of individual particles that are generally invisible to the naked eye, similar to smoke in air.")

That's why the long-standing aquarium "mythology" which suggested that blackwater aquariums, or aquariums with tinted water were somehow "dirtier" than "blue water" tanks used to drive me crazy. The term "blackwater" describes a number of things; however, it's not a measure of the "cleanliness" of the water in an aquarium, is it?

Nope.

Chemical analysis of compounds like ammonia, nitrite, nitrate, and phosphate- and measurements of the conductivity/redox potential of the water are the indicators of its "cleanliness."

Color alone is not indicative of water quality for aquarium purposes, nor is "turbidity." Sure, by municipal drinking water standards, color and clarity are important, and can indicate a number of potential issues...But we're not talking about drinking water here, are we?

No, we aren't!

(And yes, aquariums with high quantities of organic materials breaking down in the water column add to the biological load of the tank, requiring diligent management. This is not shocking news. Frankly, I find it rather amusing when someone occasionally tells me that what we do as a community is "reckless", and that our tanks look "dirty."

As if we don't see that or understand why our tanks look the way they do? And we do know the color and visual characteristics of are water are the way they are for certain reasons- just NOT because the water is of "low quality."

There is a difference between "color" and "clarity."

The color is, as you know, a product of tannins and humic acids leaching into the water from wood, soils, and botanicals, and typically is not "cloudy." It's actually one of the most "natural-looking" water conditions around, as water influenced by soils, woods, leaves, etc. is ubiquitous around the world. Other than having that undeniable color, there is little that differentiates this water from so-called "crystal clear" water to the naked eye.

Of course, the water may have a lower pH and general hardness, but these factors have no bearing on the color or visual clarity of the water. And conversely, dark brown water isn't always soft and acidic. You can have very hard, alkaline water that, based on our hobby biases, looks like it should be soft and acid. Color is NO indicator of pH or hardness! Again, it's one of those things where we seem to ascribe some sort of characteristics to the water based solely on its appearance.

As I've mentioned before, a funny by-product of our more recent obsession with blackwater aquariums in the hobby is a concern about the "tint" of the water, and yeah, perhaps even the "flavor" of said water! A by-product of our acceptance of natural influences on the water, and a desire to see a more realistic representation of certain aquatic environments.

And that means that dark water we love so much.

Natural black waters typically arise from highly leached tropical environments where most of the soluble elements are rapidly removed by heavy rainfall. Materials such as soils are the primary influence on the composition of blackwater. Leaves and other materials contribute to the process in Nature, but are NOT the primary “drivers” of its creation and composition.

Okay, so there we had another discussion of the visual characteristics of water. It's a bit funny that we don't have to think much about water, in terms of "aesthetics" in most typical aquariums.

It's definitely a "botanical method thing."

Yet, it all boils down to the fact that, when we utilize botanical materials in our aquariums for the purpose of influencing the ecology, we also get the "collateral benefit" of tinted water. And in some instances, the tinted water can impact the appearance of the inhabitants.

We as aquarists need to get our heads around the idea, once again, that this type of more natural aquarium brings its own unique aesthetics. And we, as hobbyists can and should learn to embrace them. It's totally okay if we don't, but it's important to understand that what we see in our aquariums is perhaps the truest reflection of Nature.

Something to think about.

And Stay Wet.

Why you should be playing with "alternative substrate materials" in your aquariums...

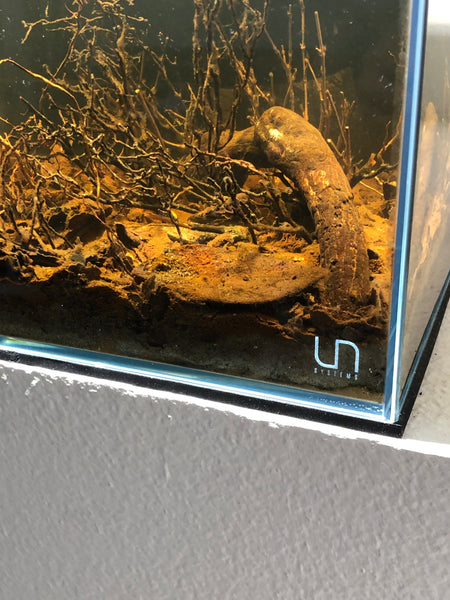

As followers of "The Tint" know, we've been on this heavy "alternative substrate" kick for about 4 years now, pushing out our ideas and creations, sharing the fruits of our research both practically, and by delving into scientific literature. And the result has been a steadily growing interest in creating and managing unique substrates within botanical method aquariums.

But the roots of our obsession with substrates goes back even farther- like to the earliest days of our company.

When we started Tannin, my fascination with the varied substrate materials of tropical ecosystems got me thinking about ways to more accurately replicate those found in flooded forests, streams, and diverse habitats like peat swamps, estuaries, creeks, even puddles- and other bodies of water, which tend to be influenced as much by the surrounding flora (mainly forests and jungles) as they are by geology.

Now, a unique class of substrate, the"Podzols"- soils characterized by a whitish-grey subsurface, bleached by organic acids- caught my attention early on, and it led to a lot of cool ideas here. They have an overlying dark accumulation of brown or black illuviated humus. These soils support the rainforests surrounding blackwater streams, yet are the most infertile soils in Amazonia.

Interesting.

And of course, my obsession with botanical materials to influence and accent the aquarium habitat caused me to look at the use of certain materials for what I call "substrate enrichment" - adding materials reminiscent of those found in the wild to augment the more "traditional" sands and other substrates used in aquariums.

And in some instances, to replace them entirely.

Think about what goes on in the benthic (bottom) regions in the natural habitats we love, and what benefits or support the materials which aggregate there provide for the organisms within the ecosystem.

Understand that the substrate is a dynamic, extremely important part of the aquarium, too. And what we construct our substrate with, and how we manage it, is of profound importance to our fishes!

Fostering fungal growth, as well as other microorganisms and small crustaceans, should be a huge component of the "why" we do this. These organisms, as we've discussed repeatedly, form a part of the "food chain" within our captive ecosystems, and offer huge benefits to the aquarium not only as potential supplemental nutrition for fishes, but as a means to process and export nutrients from within the botanical-method aquarium.

A combination of finely crushed leaves, bits of botanicals, small twigs, etc. can form the basis for a more "biologically active" and even productive substrate. As these materials break down, they are colonized by fungi and biofilms, and impart tannins, lignin, and other sources of carbon into the water to fuel a variety of microbial growth.

And of course, larger crustaceans and even fishes will consume the organisms which live in this "matrix", as well as possibly consuming some of the detritus from the decomposing leaves themselves. This is precisely what happens in natural systems.

I'm fascinated by the different types of soils or substrate materials which occur in blackwater systems, and how they influence the aquatic environment. Keep in mind that many of the habitats we obsess over, like Amazonian "igapos" and "igarapes" are seasonally-inundated forest-floor features, so it goes without saying that the terrestrial soil composition and associated biomass have significant influence on the aquatic environments that emerge during the wet season.

Its a very different looking- and functioning- substrate, for sure. And it can absolutely be replicated successfully in the aquarium. Adding materials reminiscent of those found in the wild to augment- or completely replace- the more "traditional" sands and other substrates used in aquariums is an easy "mental shift" that we can make and act upon.

With our embrace of "detritus" or "mulm" as a source of "fuel" for creating active biological systems within the confines of our aquariums, I think that the idea of an "enriched substrate," replete with botanical materials, will become an integral part of the overall ecosystems that we create. Considering the substrate as both an aesthetic AND functional component- especially in "non-plant-focused" aquariums, opens up a whole new area of aquarium "exploration."

I envision that the future of mainstream aquarium practice may include creating such a substrate as simply part of what we do. Adding a mix of botanical materials, live bacterial and small organism cultures, and even some "detritus" from healthy aquatic systems may become how we establish systems. For botanical-method aquariums, which tend to be less plant-focused, establishing the "ecosystem" is very important.

And the idea is not THAT crazy- it's long been practice to add some sand or filter media from established aquariums into new tanks to help "jump-start" necessary biological processes. It makes sense, and the overall concept is really not that difficult to grasp. And we probably shouldn't get too crazy into understanding every single aspect of this practice. Suffice it to say, something about this practice works, for reasons which we already tangentially understand.

In a strictly aesthetic sense, the bottom itself becomes a big part of the aesthetic focus of the aquarium as well, with the botanicals placed upon the substrate- or, in some cases, becoming the substrate. Okay, cool. What are some other materials you can play with to create these "alternative" substrates?

How about...twigs?

Twigs are really fascinating to me as a substrate, because not only do they create an interesting-looking substrate, they provide unique functional benefits as well. They create "interstitial spaces" (defined as "spaces between objects") which create areas for various fauna (small crustaceans, worms, and aquatic insects), as well as a surface for biofilm, algae, and fungal attachment and growth. The matrix offer protection for these organisms to grow.

Of course, it also provides a foraging area for the fishes. A place where they, too can shelter when needed. A place for them to spawn on and in.

And of course, a mixing of elements - sand, sediments, crushed botanicals, etc., is yet another approach that you can take to creating a very unique and highly functional substrate. Allowing natural processes of decomposition to take place in and on the substrate is considered "best practice" in this approach.

Why? Because if we try to remove the detritus or other "offensive" material from a substrate created for this purpose, we're effectively depriving "someone"- some beneficial organisms- of their food source. Thus, a slowdown- or even a complete breakdown- of the very processes we're trying to foster-occurs.

There is something incredibly beautiful and useful about utilizing these alternative materials in our substrates. They have created an incredible opportunity for us as hobbyists to forge new directions in the hobby. And as a brand, the idea has really pushed me to develop some "off-the-shelf" solutions for hobbyists to experiment with.

I envision that the future of mainstream aquarium practice may one day include creating such a substrate as simply part of what we do. . For botanical method aquariums, which tend to be less plant-focused, establishing the "ecosystem" is very important.

(The part where Scott bitches and "editorializes a bit...)

Now happily, there are a few manufacturers who are starting to release and talk about different types of substrates for use in aquariums other than planted systems.

It's a good start, helping to fill the gap in what has been a neglected hobby product sector (as we've been pointing out for years here), but it once again has resulted in some of these companies touting aesthetics above all, which, in my opinion, is not just disappointing, but a huge fail for the hobby. It keeps happing like this...

Why companies which tout themselves as "unique" or "progressive" continue to fall back on the vapid, vacuous "aesthetics first" mindset when creating and discussing what could be game-changing products if they just tweaked both the product and the messaging just a bit is beyond me. With the resources some of them have, it makes no sense to me to keep doing this.

Why do they do this?

I think they do it this way because it's "safe", "easy", and fast to market. When you don't have to educate people on anything more than color and texture choices, all it takes is some capital to acquire and package your product, do a few social media posts, and release it to the YouTube "influencer" crowd- and your an instant "player..."

Ouch. Unfair, perhaps? But entirely correct.

So, hit me up guys, if you need some "consultation", lol. I can get your straightened out... I know that you can do better!😎

Okay, off the well-worn soapbox for now.

To summarize, I think one of the most "liberating" things we've seen in the botanical-method aquarium niche is our practice of utilizing the substrate itself to become a feature in our aquariums, as well as a functional mechanism for the inhabitants.

In other words, if we do go down the road of looking at things in a strictly aesthetic sense, the bottom itself becomes a big part of the focus of the aquarium, with the botanicals placed upon the substrate- or, in some cases, becoming the substrate! These materials form an attractive, texturally varied "micro-scape" of their own, creating color, interest, and functions that we are just starting to appreciate.

In fact, I dare say that one of the next "frontiers" in our niche would be an aquarium which is just substrate materials, with minimal, if any, "vertical relief" provide by wood or rocks.

I've been beating that drum for a while now, huh?

I've executed quite a few aquariums based on this idea (specifically, with leaves), and I've been extremely happy with their long-term performance! Oh, and yeah-they kind of looked cool, too...

Nature provides no shortage of habitats with unusual substrate composition for inspiration. If we look at them in context of the surrounding terrestrial ecosystem, there are a lot of possible "functional takeaways" that we as hobbyists can apply to our aquarium work.

And the interesting thing about these features, from an aesthetic standpoint, is that they create an incredibly alluring look with a minimum of "design" required on the hobbyists' part. Remember, you can to put together a substrate with a perfect aesthetic mix of colors and textures, but that's about it.

We have to "cede" some of the "work" to Nature at that point!

Once your substrate is in place, Nature takes over and the materials develop that lovely "patina" of biofilms and microbial growth, and start breaking down. Some may be moved about by the grazing activities of resident fishes, or otherwise slowly redistributed around the aquarium. I suppose the degree to which this happens is dependent upon the type of substrate material you utilize.

This is not unlike what occurs in the wild habitats...newly inundated forest floors have a lot of leaf litter, seed pods, etc., and will be quite turbid for some time. If you understand the context for which they are intended, and the habitats which they help to replicate, this is perfectly acceptable and logical...Of course, you need to make that "mental shift", right?

Much like in Nature, the materials that we place on the bottom of the aquarium will become an active, integral part of the ecosystem. From a "functional" standpoint, bottoms comprised of substrates supplemented with a variety of botanical materials seem to form a sort of "in-tank refugium", which allows small aquatic crustaceans, fungi, and other microorganisms to multiply and provide supplemental food for the aquarium, as we've touched on before over the years here.

Let's keep on this stuff.

Let's keep questioning aquarium hobby dogma, but let's not become dogmatic ourselves. Let's call out shoddy work and b.s. when we see it, but not to the point of stifling anyone. Let the manufacturers know they should up their game (that includes me, too..)

And, if we're off on our assertions, let's figure out why, and see just what is actually happening in our tanks. If you haven't; figure this out by now, the whole world of botanical method aquariums is, in actuality, one big, grand experiment- and everyone is invited to play!

That means YOU!

Stay creative. Stay excited. Stay motivated. Stay curious. Stay unique. Stay observant. Stay diligent...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Leaves. Yet again.

One of the more satisfying things about working with the botanical aquarium method "movement" is that, over the years, we've seen our thoughts evolve from fringe ideas to interesting experiments to "best practices" as more and more hobbyists began to try them for themselves.

Pretty much the "foundational" piece to our methodology has been to employ leaves into our aquariums. We've been talking about this for 7 years now, and although it seems like a long time, not only weren't we the first people to suggest adding leaves to aquariums. I do, however, think that we were at least among the first to suggest that leaves be added to aquariums not simply to "tint the water" or "lower the pH", but to create a functional substrate which fosters a microbiome of organisms to support the aquarium. Yeah, it's about the function.

Long-held fears and concerns, such as overwhelming our systems with biological materials, and the overall "look" of decomposing leaves and botanicals in our tanks, have understandably led to this idea being relegated to "sideshow status" for many years. It's only been recently that we've started looking at them more objectively as ecological niches worth replicating in aquariums.

Yet, to this day, we see a lot of social media posts by both hobbyists (and distressingly) by some aquatic vendors/manufacturers waxing on about the aesthetics of adding leaves to your tank, and how they can create a "natural look." Yes, I cringe a bit when I see this- but don't get me wrong- adding leaves to your aquarium does create a cool "look". And it's pretty "natural", for sure!

However, to merely proffer adding leaves to your tank for their visual sexiness overlooks the amazing ecological benefits they provide. And, often these suggestions fail to mention the fact that, even if you want leaves in your tank just for the look- they WILL have some impact on the environment within it. And there are implications about how we manage aquariums with leaf litter present.

Yet, through it all, there is the irony that the function of the leaves creates an even sexier aesthetic- something that we'll touch on later.

So, I think today we'll focus on some of those functional and practical aspects of using leaves in your aquarium again today.

I suppose that there are occasional smirks and giggles from some corners of the hobby when they initially see our tanks, with some thinking, "Really? They toss in a few leaves and they think that the resulting sloppiness is "natural", or some evolved aquascaping technique or something?"

Funny thing is that, in reality, it IS a sort of evolution, isn't it?

I mean, sure, on the surface, this doesn't seem like much: "Toss botanical materials in aquariums. See what happens." It's not like no one ever did this before. And to make it seem more complicated than it is- to develop or quantify "technique" for it (a true act of human nature, I suppose) is probably a bit humorous.

On the other hand, as I just mentioned it's not just to create a cool-looking tank, or one which requires "less maintenance." We don't embrace the aesthetic of dark water, a bottom covered in decomposing leaves, and the appearance of biofilms and algae on driftwood because it allows us to be more "relaxed" in the care of our tanks.

I mean, we are doing this for a reason: To create more natural-functioning aquatic displays for our fishes, which just happen to look different (and attractive!) as well. To understand and acknowledge that our fishes and their very existence is influenced by the habitats in which they have evolved.

Wild tropical aquatic habitats are influenced greatly by the surrounding geography and flora of their region, which in turn, have considerable influence upon the population of fishes which inhabit them, and their life cycle. The simple fact of the matter is, when we add leaves and other botanical materials to an aquarium and accept what occurs as a result-regardless of wether our intent is just to create a different aesthetic, or perhaps something more- we are to a very real extent actually replicating the processes and influences that occur in wild aquatic habitats in Nature!

The presence of botanical materials such as leaves in these aquatic habitats is fundamental.

In the tropical species of trees, the leaf drop is important to the surrounding environment. The nutrients are typically bound up in the leaves, so a regular release of leaves by the trees helps replenish the minerals and nutrients which are typically depleted from eons of leaching into the surrounding forests.

Most tropical forest trees are classified as "evergreens", and don't have a specific seasonal leaf drop like the "deciduous" trees than many of us are more familiar with do...Rather, they replace their leaves gradually throughout the year as the leaves age and subsequently fall off the trees.

The implication here?

There is a more-or-less continuous "supply" of leaves falling off into the jungles and waterways in these habitats, which is why you'll see leaves at varying stages of decomposition in tropical streams. It's also why leaf litter banks may be almost "permanent" structures within some of these bodies of water!

In Nature, leaf litter zones comprise one of the richest and most diverse biotopes in the tropical aquatic ecosystem, yet they are seldom replicated in the aquarium. I think this has been due, in large part- to the lack of continuous availability of products for the hobbyist to work with, and a real understanding about what this biotope is all about- not to mention, the understanding of the practicality of creating one in the aquarium.

Fast-forward a few years, and many of us are playing with the idea of incorporating leaf litter into our tanks- something that was given little more than a passing bit of attention a few years ago, if that. This increased level of attention to this environmental niche among hobbyists is reaping benefits for those who have played with it.

Leaves are sort of the "gateway drug", if you will, into our world.

And it is a different world now.

We are collectively looking more seriously at the wild aquatic habitats from which our fishes come, and how they influence their lives and well-being. Looking at these habitats not only as something we'd like to replicate the look of in our aquariums, but the function- is a big evolution in the aquarium hobby, IMHO.

In the properly-constructed and managed botanical-method aquarium, I believe that leaf litter certainly performs a similar role in helping to sequester these materials. This is an exciting field of study for our community!

Back to Nature for a second. What happens when a leaf falls into the water?

At some point, the leaves of deciduous trees (trees which shed leaves annually) stop photosynthesizing in their structures, and other metabolic processes within the leaves themselves begin to shut down, which triggers a process in which the leaves essentially “pass off” valuable nitrogen and other compounds to storage tissues throughout the tree for utilization. Ultimately, the dying leaves “seal” themselves off from the tree with a layer of spongy tissue at the base of the stalk, and the dry skeleton falls off the tree.

As we know by now, when these leaves fall into the water, or are immersed following the seasonal rains, they form a valuable substrate for fungi to break down the remaining intact leaf structures. And the fungi population helps contribute to the bacterial population which creates the now-famous biofilms, which consist of sugars, vitamins, and various proteins which many fishes in both their juvenile and adult phases utilize for supplemental nutrition.

And of course, as the fishes eliminate their waste in metabolic products, this contributes further to the aquatic food chain. And yeah, it all starts with a dried up leaf!

Interesting semi-anecdotal observations from my friends in the know, suggest that the biofilms for decaying leaves form a valuable secondary food for the fry of fishes such as Discus, Uaru, (after they’re done feeding on their parent’s exuded slime coat) and even Loricariid catfishes. And of course, all sorts of other grazing fishes, like some characins and even Cyprinids, can derive some nutrition from the fungi, bacteria, and small crustaceans which live in, on, and among the leaf litter bed.

I’ve seen fishes such as Pencilfish (specifically, but not limited to N. marginatus ) spend large amounts of time during the day picking at leaf litter and the surfaces of decomposing botanicals, and maintaining girth during periods when I’ve been traveling or what not, which leads me to believe they are deriving at least part of their nutrition from the leaf litter/botanical bed in the aquarium.

In the aquarium, much like in the natural habitat, the layer of decomposing leaves and botanical matter, colonized by so many organisms, ranging from bacteria to macro invertebrates and insects, is a prime spot for fishes! The most common fishes associated with leaf litter in the wild are species of characins, catfishes and electric knife fishes, followed by our buddies the Cichlids (particularly Apistogramma, Crenicichla, and Mesonauta species)! Some species of RIvulus killies are also commonly associated with leaf litter zones, even though they are primarily top-dwelling fishes.

Leaf litter beds are so important for fishes, as they become a refuge for fish providing shelter and food from associated invertebrates!

WORKING WITH LEAVES: THE PREP PART.

The preparation of leaves is one of the few "controversies" in the botanical method aquarium world.

Why, Scott? Why do we boil this stuff?

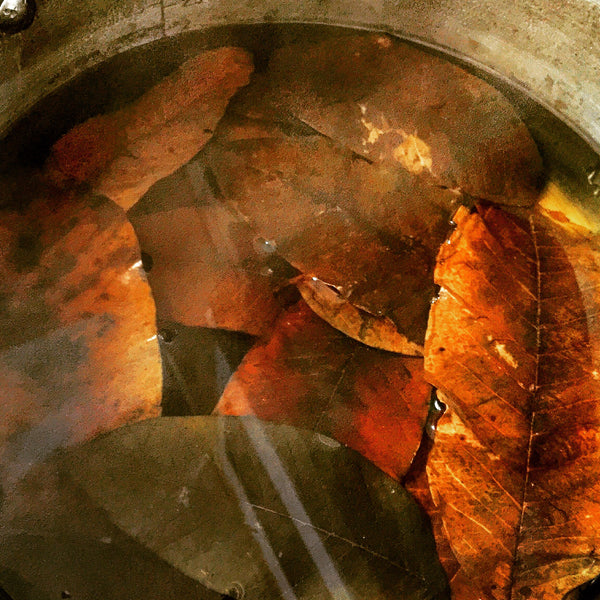

Well, to begin with, consider that boiling water is used as a method of making water potable by killing microbes that may be present. Most nasty microbes "check out" at temperatures greater than 60 °C (140 °F). For a high percentage of microbes, if water is maintained at 70 °C (158 °F) for ten minutes, many organisms are killed, but some are more resistant to heat and require one minute at the boiling point of water. (FYI the boiling point of water is 100 °C, or 212 °F)...But for the most part, most of the nasty bacteria that we don't want in either our tanks or our stomachs are eliminated by this simple process.

Ten minutes of boiling is "golden", IMHO. Of course, we boil for other reasons, as we'll touch on in a bit.

For one reason, we boil leaves and botanicals to kill any possible microorganisms which might be present on them. Leaves have been exposed to rain and dust and all sorts of things in the natural environment which, in the confines of an aquarium, could introduce unwanted organisms and contribute to the degradation of the water quality.

The surfaces and textures of many leaves lend themselves to retaining dirt, soot, dust, and other atmospheric pollutants that, although likely harmless in the grand scheme of things, are not stuff you want to start our with in your tank.

So, we give all of our stuff a good rinse.

Then we boil.

Boiling also serves to soften leaves and botanicals.

If you remember your high school Botany, leaves, for example, are surprisingly complex structures, with multiple layers designed to reject pollutants, facilitate gas exchange, drive photosynthesis, and store sugars for the benefit of the plant on which they're found. As such, it's important to get them to release some of the materials which might be bund up in the epidermis (outer layers) of the leaf. As we get deeper into the structure of a leaf, we find the mesophyll, a layer of tissue in which much of photosynthesis takes place.

We use only dried leaves in our botanical method aquariums, because these leaves from deciduous trees, which naturally fall off the trees in seasons of inclement weather, have lost most of their chlorophyll and sugars contained within the leaf structures. This is important, because having these compounds present, as in living leaves, contributes excessively to the bioload of the aquarium when submerged...

And I like to steep the leaves for a bit, too.

Overkill?

I don't think so, but that's just me.

The steep will help break down the tissues a bit to facilitate sinking, eliminate any surface contaminants, and help release some of the remaining sugars and initial tannins bound up in the leaf tissue. Of course, everyone asks if you're eliminating all of the beneficial tannins when you do this.

My answer: No. You re not. They will keep leaching out tannins for quite some time, even after this comprehensive prep process.

Everyone has a different opinion on this; that's just mine. Lately, I admit I've forgone the boiling water in favor of a room-temperature overnight soak, or sometimes, just a heavy rinse in tap water, and then added the leaves to my aquariums. I've encountered no problems, other than a slightly higher "buoyancy" with the non-steeped leaves.

Some people might say they last longer, too. Your call. In the interest of providing the most conservative advice for the greatest majority of hobbyists, I stand by my recommendations to employ some form of prep, as outlined here.

As far as "placement" and "depth of litter bed" is concerned, that's really up to you. I've gone over the possible issues with adding a proportionately large influx of fresh leaves and botanicals to an established aquarium at once, and I stand by my recommendation to go slowly.

As you are aware, rapidly adding a bunch of leaves to an established tank will contribute to the bioload of the aquarium, not to mention, potentially decrease the pH, Increase the CO2, and can have some serious consequences for the animals in your system.

Besides, part of the fun is watching the aquarium "evolve" over time. Test pH, ammonia, and nitrite regularly during the first few days after you've added the botanicals to an existing tank, and perhaps pH and nitrate/phosphate on the longer term, to establish "baseline" parameters and monitor any trends as your system matures. "Test, then tweak" is a favorite old aquarium adage of mine for a good reason.

Patience.

Depth-wise, it's your call, and wide open for experimentation. In a properly filtered, well-maintained aquarium, I see little reason why you couldn't create a very deep litter bed, approaching 8-10 inches (20.32-25.4 cm) deep- or more! In nature, leaf litter beds may be several meters deep!

Now, I realize that an aquarium is not an open-system like a stream, and that there are upper limits to what you can do, so the real takeaway here is that, with careful experimentation, observation, and a willingness to make "mid-course corrections", you as the hobbyist can try all sorts of things with regards to depth and composition of your leaf litter bed.

And of course, leaves decompose.

And my recommendation is always to leave them "in play" until they completely decompose.

Ahh, decomposition. It goes hand-in-hand with the application of leaves in aquariums...Let's ping-pong back to the wild for a second to talk about this.

Decomposition is an amazing process by which Nature processes materials for use by the greater ecosystem. It's the first part of the recycling of nutrients that were used by the plant from which the botanical material came from. When botanical material decays, it is broken down and converted into more simple organic forms, which become food for all kinds of organisms at the base of the ecosystem.

In aquatic ecosystems, much of the initial breakdown of botanical materials is conducted by detritivores- specifically, fishes, aquatic insects and invertebrates, which serve to begin the process by feeding upon the tissues of the seed pod or leaf, while other species utilize the "waste products" which are produced during this process for their nutrition.

In these habitats, such as streams and flooded forests, a variety of species work in tandem with each other, with various organisms carrying out different stages of the decomposition process.

Interestingly, in some wild aquatic habitats, such as the famous Peat swamps of Southeast Asia, the decomposition of leaves which fall into these waters is remarkably slow. In fact, ecologists have observed that the leaves typically do not break down.

Why?

It's commonly believed that these low nutrient waters, which are high in tannins, and highly acidic, seem to impede microbial activity. This is seemingly at odds with the understanding that passive leaching of dissolved organic compounds (DOC) from leaf litter has been found to be a major source of energy in tropical stream habitats, fueling the microbial food chains which we are so fascinated by.

No doubt the water parameters have something to do with this. These are unique habitats. Here are a few stats from the peat swamps in which some studies on leaf decomposition were conducted:

Water temperature: 25C/77F-32C/89F

pH: 2.6-3.8

TDS: 89-134mg/l

Nitrate: <0.-0.2mg/l

Dissolved oxygen: 1.8-16mg/l

In the studies, leaves of native species found along the swamps submerged in the waters of the swamps lost very little biomass, which other leaves from trees did break down more substantially. This tends to rule out the generally-held theory that ecologists have which postulates that the slow decomposition rate in the peat swamps is due to the extreme conditions. Rather, as mentioned above, it's believed that the resistance to decomposition is due to the physical and chemical properties of the leaves which are found right along the swamps.

(image by Marcel Silvius)

The reason? Well, think about it.

Leaf litter in tropical peat swamp forests builds up into peat many feet deep over thousands of years, and thus impedes nutrient cycling. And when you think about it, inputs of nutrients into most peat swamps come solely from rainfall, because rivers and streams in the region don't always flow into the swamps. In such nutrient poor, highly acidic conditions, it is more beneficial for plants to protect their leaves, rather than to replace them when subjected to elements like wind, and herbivore damage (mostly by insects) with new growth.

And interestingly, bacteria and fungi are known to be responsible for leaf breakdown in the peat swamps, because ecologists typically don't encounter aquatic invertebrates in the peat swamp which are known to ingest leaf material!

Our friends, the fungi!

Yeah, those guys again.

Fungi are regarded by biologists to be the dominant organisms associated with decaying leaves in streams, so this gives you some idea as to why we see them in our aquariums, right?

Here's a fascinating conclusion from a study by researchers Catherine M. Yule and Lalita N. Gomez on leaching of dissolved organic carbon (DOC) in the early stages of the leaf litter decomposition in these peat swamps:

"Most of the DOC appears to be leached within a few weeks of leaves falling into the swamp and thus it appears likely that the cycling of DOC is rapid, and occurs before the leaves become part of the peat deposits. This would further explain the presence of the thick, superficial root mat layer (also a response to waterlogging) that is a key feature of tropical peat forests, since the processes of nutrient cycling would occur in the upper leaf litter layer, rather than the deeper, waterlogged peat."

Okay, neat stuff. It kind of reminds me of those "bog mummies" from Europe, in which the ancient remains s of humans are very well preserved because of the acidic, oxygen-poor conditions of these bogs where the bodies are found.

During the wet season, the peat swamps are inundated with water, which slows down the aerobic decomposition which occurs in the substrate- conditions which facilitate the formation of peat. The breakdown of leaves in the wild is fascinating, as are the implications for the process in our aquariums.

This is a dynamic, fascinating process- part of why we find the idea of a natural, botanical-style system so compelling. Many of the organisms- from microbes to micro crustaceans to fungi- are almost never seen except by the most observant and keen-eyed hobbyist...but they're there- doing what they've done for eons. They work slowly and methodically over weeks and months, converting the botanical material into forms that are more readily assimilated by themselves and other aquatic organisms.

The real cycle of life!

And another reason why the surrounding tropical forests are so vital to life. The allochthonous leaf material from the riparian zone (ie; from the trees!) as a source of energy for stream invertebrates, insects and fishes can't be understated! When we preserve the rain forests and their surrounding terrestrial habitats, we're also preserving the aquatic life forms which are found there when the waters return.

In our aquariums, we're just beginning to appreciate the real benefits of using leaves and botanicals. Not just for cool aesthetics or to "tint" the water- but to create truly natural, ecologically stable aquatic systems for the health and well-being of the fishes we love so much!

There's a whole lot there to unpack about leaves in the aquairum- drawing from a variety of scientific fields, such as biology, chemistry, and ecology, as well as from our everyday practices as aquarists.

The next time you see a social media post by an "authority" or a brand waxing on about how cool and natural leaves look as aquascaping "props" in an aquarium, just remind yourself that there is so much more to them than that. Don't sell yourself- or the idea- short by touting only the "look."

Studying the influences of leaves on aquatic environments, and how to replicate and incorporate these influences into our aquariums is the key. Building a specialized aquatic microcosm in our tanks will unlock so many secrets and lead to amazing breakthroughs with our fishes- and a greater understanding of the precious natural habitats from which they come.

Stay curious. Stay resourceful. Stay diligent. Stay informed...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Twigs and tangles..

When we first started Tannin Aquatics, the goal was to offer all sorts of useful natural products, with the intention of creating a selection of materials which impact the aquairum environment in many different ways.