- Continue Shopping

- Your Cart is Empty

Leaves. Yet again.

One of the more satisfying things about working with the botanical aquarium method "movement" is that, over the years, we've seen our thoughts evolve from fringe ideas to interesting experiments to "best practices" as more and more hobbyists began to try them for themselves.

Pretty much the "foundational" piece to our methodology has been to employ leaves into our aquariums. We've been talking about this for 7 years now, and although it seems like a long time, not only weren't we the first people to suggest adding leaves to aquariums. I do, however, think that we were at least among the first to suggest that leaves be added to aquariums not simply to "tint the water" or "lower the pH", but to create a functional substrate which fosters a microbiome of organisms to support the aquarium. Yeah, it's about the function.

Long-held fears and concerns, such as overwhelming our systems with biological materials, and the overall "look" of decomposing leaves and botanicals in our tanks, have understandably led to this idea being relegated to "sideshow status" for many years. It's only been recently that we've started looking at them more objectively as ecological niches worth replicating in aquariums.

Yet, to this day, we see a lot of social media posts by both hobbyists (and distressingly) by some aquatic vendors/manufacturers waxing on about the aesthetics of adding leaves to your tank, and how they can create a "natural look." Yes, I cringe a bit when I see this- but don't get me wrong- adding leaves to your aquarium does create a cool "look". And it's pretty "natural", for sure!

However, to merely proffer adding leaves to your tank for their visual sexiness overlooks the amazing ecological benefits they provide. And, often these suggestions fail to mention the fact that, even if you want leaves in your tank just for the look- they WILL have some impact on the environment within it. And there are implications about how we manage aquariums with leaf litter present.

Yet, through it all, there is the irony that the function of the leaves creates an even sexier aesthetic- something that we'll touch on later.

So, I think today we'll focus on some of those functional and practical aspects of using leaves in your aquarium again today.

I suppose that there are occasional smirks and giggles from some corners of the hobby when they initially see our tanks, with some thinking, "Really? They toss in a few leaves and they think that the resulting sloppiness is "natural", or some evolved aquascaping technique or something?"

Funny thing is that, in reality, it IS a sort of evolution, isn't it?

I mean, sure, on the surface, this doesn't seem like much: "Toss botanical materials in aquariums. See what happens." It's not like no one ever did this before. And to make it seem more complicated than it is- to develop or quantify "technique" for it (a true act of human nature, I suppose) is probably a bit humorous.

On the other hand, as I just mentioned it's not just to create a cool-looking tank, or one which requires "less maintenance." We don't embrace the aesthetic of dark water, a bottom covered in decomposing leaves, and the appearance of biofilms and algae on driftwood because it allows us to be more "relaxed" in the care of our tanks.

I mean, we are doing this for a reason: To create more natural-functioning aquatic displays for our fishes, which just happen to look different (and attractive!) as well. To understand and acknowledge that our fishes and their very existence is influenced by the habitats in which they have evolved.

Wild tropical aquatic habitats are influenced greatly by the surrounding geography and flora of their region, which in turn, have considerable influence upon the population of fishes which inhabit them, and their life cycle. The simple fact of the matter is, when we add leaves and other botanical materials to an aquarium and accept what occurs as a result-regardless of wether our intent is just to create a different aesthetic, or perhaps something more- we are to a very real extent actually replicating the processes and influences that occur in wild aquatic habitats in Nature!

The presence of botanical materials such as leaves in these aquatic habitats is fundamental.

In the tropical species of trees, the leaf drop is important to the surrounding environment. The nutrients are typically bound up in the leaves, so a regular release of leaves by the trees helps replenish the minerals and nutrients which are typically depleted from eons of leaching into the surrounding forests.

Most tropical forest trees are classified as "evergreens", and don't have a specific seasonal leaf drop like the "deciduous" trees than many of us are more familiar with do...Rather, they replace their leaves gradually throughout the year as the leaves age and subsequently fall off the trees.

The implication here?

There is a more-or-less continuous "supply" of leaves falling off into the jungles and waterways in these habitats, which is why you'll see leaves at varying stages of decomposition in tropical streams. It's also why leaf litter banks may be almost "permanent" structures within some of these bodies of water!

In Nature, leaf litter zones comprise one of the richest and most diverse biotopes in the tropical aquatic ecosystem, yet they are seldom replicated in the aquarium. I think this has been due, in large part- to the lack of continuous availability of products for the hobbyist to work with, and a real understanding about what this biotope is all about- not to mention, the understanding of the practicality of creating one in the aquarium.

Fast-forward a few years, and many of us are playing with the idea of incorporating leaf litter into our tanks- something that was given little more than a passing bit of attention a few years ago, if that. This increased level of attention to this environmental niche among hobbyists is reaping benefits for those who have played with it.

Leaves are sort of the "gateway drug", if you will, into our world.

And it is a different world now.

We are collectively looking more seriously at the wild aquatic habitats from which our fishes come, and how they influence their lives and well-being. Looking at these habitats not only as something we'd like to replicate the look of in our aquariums, but the function- is a big evolution in the aquarium hobby, IMHO.

In the properly-constructed and managed botanical-method aquarium, I believe that leaf litter certainly performs a similar role in helping to sequester these materials. This is an exciting field of study for our community!

Back to Nature for a second. What happens when a leaf falls into the water?

At some point, the leaves of deciduous trees (trees which shed leaves annually) stop photosynthesizing in their structures, and other metabolic processes within the leaves themselves begin to shut down, which triggers a process in which the leaves essentially “pass off” valuable nitrogen and other compounds to storage tissues throughout the tree for utilization. Ultimately, the dying leaves “seal” themselves off from the tree with a layer of spongy tissue at the base of the stalk, and the dry skeleton falls off the tree.

As we know by now, when these leaves fall into the water, or are immersed following the seasonal rains, they form a valuable substrate for fungi to break down the remaining intact leaf structures. And the fungi population helps contribute to the bacterial population which creates the now-famous biofilms, which consist of sugars, vitamins, and various proteins which many fishes in both their juvenile and adult phases utilize for supplemental nutrition.

And of course, as the fishes eliminate their waste in metabolic products, this contributes further to the aquatic food chain. And yeah, it all starts with a dried up leaf!

Interesting semi-anecdotal observations from my friends in the know, suggest that the biofilms for decaying leaves form a valuable secondary food for the fry of fishes such as Discus, Uaru, (after they’re done feeding on their parent’s exuded slime coat) and even Loricariid catfishes. And of course, all sorts of other grazing fishes, like some characins and even Cyprinids, can derive some nutrition from the fungi, bacteria, and small crustaceans which live in, on, and among the leaf litter bed.

I’ve seen fishes such as Pencilfish (specifically, but not limited to N. marginatus ) spend large amounts of time during the day picking at leaf litter and the surfaces of decomposing botanicals, and maintaining girth during periods when I’ve been traveling or what not, which leads me to believe they are deriving at least part of their nutrition from the leaf litter/botanical bed in the aquarium.

In the aquarium, much like in the natural habitat, the layer of decomposing leaves and botanical matter, colonized by so many organisms, ranging from bacteria to macro invertebrates and insects, is a prime spot for fishes! The most common fishes associated with leaf litter in the wild are species of characins, catfishes and electric knife fishes, followed by our buddies the Cichlids (particularly Apistogramma, Crenicichla, and Mesonauta species)! Some species of RIvulus killies are also commonly associated with leaf litter zones, even though they are primarily top-dwelling fishes.

Leaf litter beds are so important for fishes, as they become a refuge for fish providing shelter and food from associated invertebrates!

WORKING WITH LEAVES: THE PREP PART.

The preparation of leaves is one of the few "controversies" in the botanical method aquarium world.

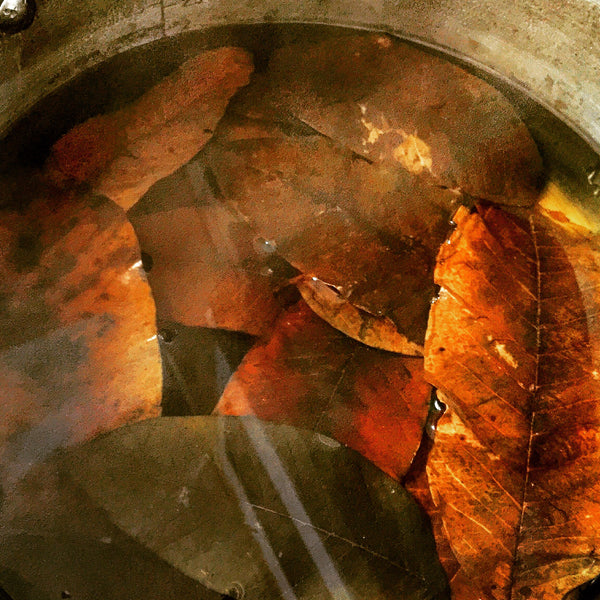

Why, Scott? Why do we boil this stuff?

Well, to begin with, consider that boiling water is used as a method of making water potable by killing microbes that may be present. Most nasty microbes "check out" at temperatures greater than 60 °C (140 °F). For a high percentage of microbes, if water is maintained at 70 °C (158 °F) for ten minutes, many organisms are killed, but some are more resistant to heat and require one minute at the boiling point of water. (FYI the boiling point of water is 100 °C, or 212 °F)...But for the most part, most of the nasty bacteria that we don't want in either our tanks or our stomachs are eliminated by this simple process.

Ten minutes of boiling is "golden", IMHO. Of course, we boil for other reasons, as we'll touch on in a bit.

For one reason, we boil leaves and botanicals to kill any possible microorganisms which might be present on them. Leaves have been exposed to rain and dust and all sorts of things in the natural environment which, in the confines of an aquarium, could introduce unwanted organisms and contribute to the degradation of the water quality.

The surfaces and textures of many leaves lend themselves to retaining dirt, soot, dust, and other atmospheric pollutants that, although likely harmless in the grand scheme of things, are not stuff you want to start our with in your tank.

So, we give all of our stuff a good rinse.

Then we boil.

Boiling also serves to soften leaves and botanicals.

If you remember your high school Botany, leaves, for example, are surprisingly complex structures, with multiple layers designed to reject pollutants, facilitate gas exchange, drive photosynthesis, and store sugars for the benefit of the plant on which they're found. As such, it's important to get them to release some of the materials which might be bund up in the epidermis (outer layers) of the leaf. As we get deeper into the structure of a leaf, we find the mesophyll, a layer of tissue in which much of photosynthesis takes place.

We use only dried leaves in our botanical method aquariums, because these leaves from deciduous trees, which naturally fall off the trees in seasons of inclement weather, have lost most of their chlorophyll and sugars contained within the leaf structures. This is important, because having these compounds present, as in living leaves, contributes excessively to the bioload of the aquarium when submerged...

And I like to steep the leaves for a bit, too.

Overkill?

I don't think so, but that's just me.

The steep will help break down the tissues a bit to facilitate sinking, eliminate any surface contaminants, and help release some of the remaining sugars and initial tannins bound up in the leaf tissue. Of course, everyone asks if you're eliminating all of the beneficial tannins when you do this.

My answer: No. You re not. They will keep leaching out tannins for quite some time, even after this comprehensive prep process.

Everyone has a different opinion on this; that's just mine. Lately, I admit I've forgone the boiling water in favor of a room-temperature overnight soak, or sometimes, just a heavy rinse in tap water, and then added the leaves to my aquariums. I've encountered no problems, other than a slightly higher "buoyancy" with the non-steeped leaves.

Some people might say they last longer, too. Your call. In the interest of providing the most conservative advice for the greatest majority of hobbyists, I stand by my recommendations to employ some form of prep, as outlined here.

As far as "placement" and "depth of litter bed" is concerned, that's really up to you. I've gone over the possible issues with adding a proportionately large influx of fresh leaves and botanicals to an established aquarium at once, and I stand by my recommendation to go slowly.

As you are aware, rapidly adding a bunch of leaves to an established tank will contribute to the bioload of the aquarium, not to mention, potentially decrease the pH, Increase the CO2, and can have some serious consequences for the animals in your system.

Besides, part of the fun is watching the aquarium "evolve" over time. Test pH, ammonia, and nitrite regularly during the first few days after you've added the botanicals to an existing tank, and perhaps pH and nitrate/phosphate on the longer term, to establish "baseline" parameters and monitor any trends as your system matures. "Test, then tweak" is a favorite old aquarium adage of mine for a good reason.

Patience.

Depth-wise, it's your call, and wide open for experimentation. In a properly filtered, well-maintained aquarium, I see little reason why you couldn't create a very deep litter bed, approaching 8-10 inches (20.32-25.4 cm) deep- or more! In nature, leaf litter beds may be several meters deep!

Now, I realize that an aquarium is not an open-system like a stream, and that there are upper limits to what you can do, so the real takeaway here is that, with careful experimentation, observation, and a willingness to make "mid-course corrections", you as the hobbyist can try all sorts of things with regards to depth and composition of your leaf litter bed.

And of course, leaves decompose.

And my recommendation is always to leave them "in play" until they completely decompose.

Ahh, decomposition. It goes hand-in-hand with the application of leaves in aquariums...Let's ping-pong back to the wild for a second to talk about this.

Decomposition is an amazing process by which Nature processes materials for use by the greater ecosystem. It's the first part of the recycling of nutrients that were used by the plant from which the botanical material came from. When botanical material decays, it is broken down and converted into more simple organic forms, which become food for all kinds of organisms at the base of the ecosystem.

In aquatic ecosystems, much of the initial breakdown of botanical materials is conducted by detritivores- specifically, fishes, aquatic insects and invertebrates, which serve to begin the process by feeding upon the tissues of the seed pod or leaf, while other species utilize the "waste products" which are produced during this process for their nutrition.

In these habitats, such as streams and flooded forests, a variety of species work in tandem with each other, with various organisms carrying out different stages of the decomposition process.

Interestingly, in some wild aquatic habitats, such as the famous Peat swamps of Southeast Asia, the decomposition of leaves which fall into these waters is remarkably slow. In fact, ecologists have observed that the leaves typically do not break down.

Why?

It's commonly believed that these low nutrient waters, which are high in tannins, and highly acidic, seem to impede microbial activity. This is seemingly at odds with the understanding that passive leaching of dissolved organic compounds (DOC) from leaf litter has been found to be a major source of energy in tropical stream habitats, fueling the microbial food chains which we are so fascinated by.

No doubt the water parameters have something to do with this. These are unique habitats. Here are a few stats from the peat swamps in which some studies on leaf decomposition were conducted:

Water temperature: 25C/77F-32C/89F

pH: 2.6-3.8

TDS: 89-134mg/l

Nitrate: <0.-0.2mg/l

Dissolved oxygen: 1.8-16mg/l

In the studies, leaves of native species found along the swamps submerged in the waters of the swamps lost very little biomass, which other leaves from trees did break down more substantially. This tends to rule out the generally-held theory that ecologists have which postulates that the slow decomposition rate in the peat swamps is due to the extreme conditions. Rather, as mentioned above, it's believed that the resistance to decomposition is due to the physical and chemical properties of the leaves which are found right along the swamps.

(image by Marcel Silvius)

The reason? Well, think about it.

Leaf litter in tropical peat swamp forests builds up into peat many feet deep over thousands of years, and thus impedes nutrient cycling. And when you think about it, inputs of nutrients into most peat swamps come solely from rainfall, because rivers and streams in the region don't always flow into the swamps. In such nutrient poor, highly acidic conditions, it is more beneficial for plants to protect their leaves, rather than to replace them when subjected to elements like wind, and herbivore damage (mostly by insects) with new growth.

And interestingly, bacteria and fungi are known to be responsible for leaf breakdown in the peat swamps, because ecologists typically don't encounter aquatic invertebrates in the peat swamp which are known to ingest leaf material!

Our friends, the fungi!

Yeah, those guys again.

Fungi are regarded by biologists to be the dominant organisms associated with decaying leaves in streams, so this gives you some idea as to why we see them in our aquariums, right?

Here's a fascinating conclusion from a study by researchers Catherine M. Yule and Lalita N. Gomez on leaching of dissolved organic carbon (DOC) in the early stages of the leaf litter decomposition in these peat swamps:

"Most of the DOC appears to be leached within a few weeks of leaves falling into the swamp and thus it appears likely that the cycling of DOC is rapid, and occurs before the leaves become part of the peat deposits. This would further explain the presence of the thick, superficial root mat layer (also a response to waterlogging) that is a key feature of tropical peat forests, since the processes of nutrient cycling would occur in the upper leaf litter layer, rather than the deeper, waterlogged peat."

Okay, neat stuff. It kind of reminds me of those "bog mummies" from Europe, in which the ancient remains s of humans are very well preserved because of the acidic, oxygen-poor conditions of these bogs where the bodies are found.

During the wet season, the peat swamps are inundated with water, which slows down the aerobic decomposition which occurs in the substrate- conditions which facilitate the formation of peat. The breakdown of leaves in the wild is fascinating, as are the implications for the process in our aquariums.

This is a dynamic, fascinating process- part of why we find the idea of a natural, botanical-style system so compelling. Many of the organisms- from microbes to micro crustaceans to fungi- are almost never seen except by the most observant and keen-eyed hobbyist...but they're there- doing what they've done for eons. They work slowly and methodically over weeks and months, converting the botanical material into forms that are more readily assimilated by themselves and other aquatic organisms.

The real cycle of life!

And another reason why the surrounding tropical forests are so vital to life. The allochthonous leaf material from the riparian zone (ie; from the trees!) as a source of energy for stream invertebrates, insects and fishes can't be understated! When we preserve the rain forests and their surrounding terrestrial habitats, we're also preserving the aquatic life forms which are found there when the waters return.

In our aquariums, we're just beginning to appreciate the real benefits of using leaves and botanicals. Not just for cool aesthetics or to "tint" the water- but to create truly natural, ecologically stable aquatic systems for the health and well-being of the fishes we love so much!

There's a whole lot there to unpack about leaves in the aquairum- drawing from a variety of scientific fields, such as biology, chemistry, and ecology, as well as from our everyday practices as aquarists.

The next time you see a social media post by an "authority" or a brand waxing on about how cool and natural leaves look as aquascaping "props" in an aquarium, just remind yourself that there is so much more to them than that. Don't sell yourself- or the idea- short by touting only the "look."

Studying the influences of leaves on aquatic environments, and how to replicate and incorporate these influences into our aquariums is the key. Building a specialized aquatic microcosm in our tanks will unlock so many secrets and lead to amazing breakthroughs with our fishes- and a greater understanding of the precious natural habitats from which they come.

Stay curious. Stay resourceful. Stay diligent. Stay informed...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Scott Fellman

Author