- Continue Shopping

- Your Cart is Empty

I did a thing..

I did something the other day that a lot of people might think is kind of crazy.

I declined tp judge one of the Country's most prestigious aquascaping contests. I mean, yeah, it was a real honor being asked, and I was in some good company. I initially gave a sort of uncomfortable, almost tacit agreement to take part. And then, after literally wrestling with it for several nights, I woke up one early morning and was like, "What the fuck are you doing, Fellman? You can;'t judge a contest. It's not who you are, or what you even believe in!"

Yeah, I realized that, despite the great honor of being asked to judge a contest, that it's simply not what I am made of to be a judge. I have spent the better part of the last 20 years encouraging and cajoling hobbyists to be their best- to express their individuality, enthusiasm, and love for the hobby in ways that make their hearts sing.

I'm a cheerleader. A provocateur. An instigator, a motivator, and a fan. And apparently, an irreverent maverick of sorts, right?

I'm not judge material.

So why the hell would I want to stare at a bunch of people's hard work, dedication, and emotion, created with love and hope- and then pronounce judgment upon them...As if I have some divine authority; or as if I'm some anointed arbiter of taste.

I'm not. I feel bad that I even sort of nodded to the idea.

I spend much time on this blog and elsewhere railing on aquascaping contests, decrying the format, arrogance of the judges, the contest "culture", and the very notion that certain people are "winners", while others are not.

Yeah, I despise contests and contest culture. I'd definitely but heads with the other judges. I hate rules. It would have made me wildly unpopular. It would have been really ugly. What the fuck was I thinking even entertaining the idea? It was uncool of me, and intellectually dishonest, at the very least.

Now, let me be clear about something:

Now sure, I see a lot of aquariums that I like. And I see things that make me want to laugh, or worse.If people ask for constructive criticism, I'll give it to them, but it's based upon MY personal tastes, experience, and philosophies.

Judging a contest, to me, goes one step further than I'd like. A huge step, really. It's using some arbitrary rules to declare that someone else's work is better than..someone else's.

I was to judge a biotope division. That's like having a vegetarian judging a barbecue contest.

You know how I feel about biotope contests, in particular. And you know my thinking about function of an aquarium over aesthetics and almost everything else. I'd likely cause huge friction between myself and fellow judges, and piss off a lot of entrants. Why? Because I'd be a lot more excited by the lady who's tank has a pile of detritus and decomposing leaves over her driftwood, than I would about the brilliantly crafted, highly stylized, intricately researched, yet (IMHO) oddly pretencious aquariums which seem to dominate that scene.

I would truly be the odd man out.

"We get it. You didn't;'t want to do the contest. You don't like them. Okay. Then bow out gracefully, Fellman, and shut the fuck up already!"

Fair point. However, you can simply navigate away from this page if you don[t want to read more. This is THERAPY for me, okay?

We've been talking a bout a contest for years. The problem is, I hate them. Our contest would be specialized, and more of an exhibition than anything else. I suppose I'd rather have our community decide on things like, "Most inspirational", "Most Unique", "Most representative of a functional natural habitat", "Longest Continuous setup", "stuff like that. No 1st, 2nd, 3rd place.

That's not me.

Would I have some standards?

Of course. One would be that if you give a name to your work, you'd be banned for life from entering our exhibition! No "Fresh Wind of Spring" or "Mountains of Life." This is not a goddam piece of art. It's not a diorama. It's an aquarium.

And no fucking essay on the geographic coordinates of the place your replicating ion your tank. No highbrow video production of the fish dancing through leaf litter necessary. How does your tank run? Are the fishes happy? What kinds of function do you embrace? What ideas can you share? How will this inspire others?

Alright, I'm literally beating the shit out of this. I'm coming across kind of angry and weird, lol.

But it feels really good to get this off my chest. Thanks for listening!

Gotta think of some ideas for MY next tank...just because!

Yeah, I'm no judge.

I'm a fish geek. That's all I am. And damn proud of it.

SO, I did a thing. And bowed out, to do what I think I do best.

That's something for me to celebrate.

Stay true to yourselves. Stay brave. Stay creative. Stay supportive. Stay inspirational...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

A rebel without a clue?

One of the more satisfying side benefits of creating Tannin Aquatics is that I have been able to share my ideas with a pretty wide audience via this blog, the podcast, club speaking engagements, and magazine articles. It's neat to share my point of view and philosophy on the aquarium hobby!

Now, something that I hear a lot is that I am sort of a "rebel" or even a "maverick" of sorts, giving my opinion on ideas, and questioning things that we've taken for granted in the hobby for generations; compelling others to try new and different approaches, and to lead by example.

I hardly see that as "rebellious."

I had a most "conventional" aquarium hobby pedigree. My dad was a fish geek, who was obsessed with guppies. I had my aquarium when I was around 4 years old. My dad was a product of the "Golden Age" of the aquarium hobby, having gotten his start in the early sixties. I learned to read by picking through my dad's dog-eared copies of Innes' Exotic Aquarium Fishes, Guppies by Axelrod, Wiltern et al., and lots of other classic books on guppies and aquarium care. I was obsessed with them!

There was- and IS- enormous wisdom in those classic books. I spend many happy hours playing with all sorts of "old school" ideas gleaned from those books. I loved the romantic descriptions of fishes and aquarium ideas in Innes' book and in the writings of Axelrod and others. As I accumulated my own library over the years, it was filled with a lot of those classics and more, with widely varying ideas.

So, where did the "rebel" part come in?

I'm not sure.

I think that it came to being because, after decades in the hobby, I saw that some things were being done "just because", without questioning, modifying, or expanding. The hobby seemed to be stagnating in some areas. And I spoke about them. ruminated about ways to move things along. To improve stuff. Offer different ways of doing things.

Is that really "rebelliousness?"

I don't know.

I admit that we do push some unusual ideas now and again...but they're inspired by Nature as it is, not by some fanciful, curated, sterilized, and "pasteurized" version that we have in our fantasies.

What I do know is the I was sick and tired of seeing really talented hobbyists simply "mailing it in", and doing stuff a certain way without question, simply because "that's the way it is done- and it works." And then, being downright arrogant and, dare I say, "asshole-ish" about it. Like, declaring that there way was THE only way, and that anything against their way of thinking was some sort of transgression....because it works. Why question it? Dogmatic to the extreme.

THAT is exactly whyI question stuff. I hate arrogance for the sake of being arrogant.

And you should, too.

When we started Tannin in 2015, the first order of business was to quantify the very thing that we believed in, and worked with. We utilized the term "botanical-style" to describe the top of aquariums that we favor. It was important to give this approach a descriptor.

As many of you have pointed out, if you search prior to 2015, the term "botanical" was simply not used to describe this stuff. You had "blackwater aquariums", which was a rather tightly focused descriptor, and it only describes some of what we do.

That was just the start.

Our brand colors are browns and golds and earth tones. We eschew the usual "web vomit" rainbow hues found in most aquarium branding, because that's only part of what Nature offers up.

Is THAT rebellious?

I don't think so.

We embrace leaves, wood, substrate, and the impact on the water that they bring...Earthy ambience, as opposed to crystal clear, prismatic brightness. A different look, too.

Is That being rebellious?

Nah.

We had to share our ideas, techniques, and educate. A huge responsibility. We all bear this. And of course, the idea of dispelling misinformation about this approach occupied- and STILL occupies- a large amount of our focus. There's so much misinformation and even lack of information out there. And the idea of pushing back against misinformation actually labeled me a "rebel" in some corners- which makes me laugh.

We have to question ideas and technique.

We HAVE to start looking at Nature AS IT REALLY IS as an influence. It's easy to fall in love with a look- we all have. But when we simply look at stuff from such a superficial lens, it sells us short. And I hate the hobby selling itself short. I hate us falling back on, "We do this because that's the way it's been done. And it works."

Of course, it works. But can't it work better?

Can't we look at stuff like detritus, biofilms, turbidity, and tint- and understand exactly how this stuff is not only beautiful to look at, but elegant and efficient in its function. And how we can't be afraid of stuff because it looks contrary to what we've been taught in the hobby to be "healthy."

It's what Nature does. And has done for untold eons.

Look closely at Nature, and ask why things are the way they are. And attempt to replicate Her processes; the "look", different as it may be- will follow.

Thinking that way is not "rebellious."

It's simply progressive. It's evolutionary.

And look, some ideas or approaches that you explore and share are not well received. Or perhaps, just maybe- they're wrong. Accept that snd move on. Part of being a progressive person in the hobby is to accept that you might be incorrect, or that your ideas might be "off" now and then. I'm okay with that. You should be, too.

Humility is a good thing to embrace in the hobby.

Don't be close minded. Look at things that are done a certain way, and if you see a better way- a more beneficial way- experiment, improve upon them, and share. And accept the good and the bad. Embrace the ephemeral.

We push a lot of unusual ideas and approaches here at Tannin Aquatics. They're not the best way- but they are a different way. And often, they fly in the face of the existing, commonly accepted way of doing stuff. Their look and function defy convention at times. And other times, they embrace things hobbyists have done for generations; perhaps stuff forgotten or dismissed in their day.

Is that being rebellious?

No.

It's not rebellious to look at things differently. To question the status quo for the sake of moving the state of the art forward. It's not rebellious to look to our hobby's glorious past to evolve it to a new and exciting future.

So, if you're labeled a rebel or "disruptor" or whatever because you look at stuff differently, perhaps because you try a slightly different approach- and believe in what you do enough to take the criticisms- just put your head down and keep doing what you believe in.

Push the hobby forward by doing. Differently.

Share. Educate. Experiment. Question. Accept blame when it's deserved, don't get too high on any accolades you might receive along the way.

And if maybe, at some point, you want to be just a bit provocative from time to time- to make some noise...Raise a bit of hell- I say go for it. 😆

The hobby needs some of that, too.

Is THAT being rebellious?

Well, maybe. But it's also kind of fun.

Okay, I might be a rebel. But I'm clueless about that part. You should be, too. Just be you. Celebrate, create. Love.

Stay curious. Stay thoughtful. Stay bold. Stay generous...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Stay

Back to the "C" word...

Our world of botanical-style aquariums is evolving rapidly. Techniques are being refined, ideas are being executed, and exciting results are becoming commonplace.

We receive a lot of questions about what sort of ongoing maintenance procedures are necessary, and what sort of challenges you face, longer-term, with these tanks...We could probably write many blog posts about this interesting topic (and we will!), but an initial "quick hit" today will hopefully jump-start the discussion! (oh, and maybe answer some questions along the way!)

As we've talked about before, for the longest time, there seemed to have been a perception among the mainstream hobby that blackwater aquariums were delicate, tricky-to-maintain systems, fraught with potential disaster; a soft-water, acidic environment which could slip precipitously into some sort of environmental "free fall" without warning.

And there was the matter of that "dark brown water..."

Not only was the tinted water considered "the whole distinction" between these types of systems and more "conventional" aquariums, it was cause for fear, misunderstanding, and "myths."

Happily, this perception seems to be eroding, as a new generation of aquarists (hey, that's YOU guys!) has taken the torch and ran with it, taking a slightly different approach- and a vastly different attitude- and is perfecting the techniques required to maintain blackwater/botanical-style aquariums for the long term.

And the "long term" is where my interest lies.

The longest I've personally maintained such a system has been about 5.5 years, and the only reason I broke down that aquarium was because of a home remodel that required the removal of everything from the space in which the aquarium was located. I set it up again shortly after the work was completed. The reality, though, is that I could have kept this system going indefinitely.

As most of you who work with these aquariums know, the key to long-term success with them is to go slowly, deploying massive amounts of patience, consistent, common-sense husbandry, monitoring of environmental parameters, and careful stocking management. Not really much different from what you'd need to do to successfully maintain ANY type of aquarium for the long haul.

Yeah, real "news flash" there, right?

Consistency above almost all else. And not taking shortcuts.

Now, with the release of "Culture", our Purple Non Sulfur Bacterial inoculant, we've received a lot of questions from fellow hobbyists, many of whom were asking about how this product will...wait for it...help them avoid water exchanges!

Are you fucking kidding me? Really?

NOOOOOOOO!

Have we taught you nothing?

Nothing- no product, additive, gadget- will make up for consistent, thoughtful maintenance practices in your aquarium...and that includes regular water exchanges.

Although "Culture" is a remarkable product- a culture of the very hardworking Rhodopseudomonas palustris, it won't eliminate the need for regular water exchanges or other maintenance activities in your aquarium. These little bacterium- capable and remarkable as they are- can't do it alone.

They consume organic wastes while inhabiting moderately illuminated and poorly oxygenated microhabitats (patches of detritus, leaf litter beds, shallow depths of substrate, deeper pores of expanded clay filter media, etc.). However, they don't eliminate the need for regular water exchanges or other husbandry tasks. Period. They're not a "miracle elixir" or "additive" that can do everything.

So, get that shit out of your head right now, okay?

Seriously, beyond my initial scolding of you for even thinking about stuff like that, I have to implore you to deploy absurd amounts of patience and to employ "radical cal consistency" in your maintenance efforts. "Radical" in the sense that you simply have to become fanatical. Consistency meaning you do it regularly. Not sometimes, or when it feels right- but regularlary. Always.

Consistent habits create consistent environmental parameters, without a doubt.

As you've heard me mention ad nauseum here, natural rivers, lakes, and streams, although subject to seasonal variations and such, are typically remarkably stable physical environments, and fishes and plants, although capable of adapting to surprisingly rapid environmental changes, have really evolved over eons to grow in consistent, stable conditions.

Consistency.

In the botanical-influenced, low alkalinity/low pH blackwater environment, consistency is really important. Although these tanks are surprisingly easy to manage and run over the long haul, consistency is a huge part of what keeps these speciality systems running healthily and happily for extended periods of time. It wouldn't take too much beginning neglect or even a little sloppiness in husbandry to start a march towards increasing nitrate, phosphate, and their associated problems, like nuisance algae growth, etc.

Consistency. Regular maintenance. Scheduled water changes. The usual stuff. Nothing magic here. Nothing that a sexy $24.00 bottle of bacterial culture is going to replace.

Nothing that you, as an experienced hobby don't already know. Right?

Just looking at your tank and its inhabitants will be enough to tell you if something is amiss. More than one advanced aquarist has only half-jokingly told me that he or she can tell if something is amiss with his/her tank simply by the "smelI!" get it- excesses of biological activities do often create conditions that are detectible by scent!

It's as much about consistency-consistency in practices and procedures- as it is about hitting those "target numbers" of pH, nitrate, etc. If you ask a lot of successful aquarists how they accomplish this-or-that, they'll usually point towards a few things, like regular water changes, good food, and adhering to the same practices over and over again.

Consistency = Stability.

Sure, there might be times you deliberately manipulate the environment fairly rapidly, like a temperature change to stimulate spawning, etc., but for the most part, the successful aquarist plays a consistent game. Most fishes come from environments that vary only slightly during he course of a day, and many only seasonally, so stability is at the heart of "best practice" for aquarists.

So, without further beating the shit out of this, I think we can successfully make the argument that consistency in all manner of aquarium-keeping endeavors can only help your animals. Keeping a stable environment is not only humane- it's playing into the very strength of our animals, by minimizing the stress of constantly having to adapt to a fluctuating environment. As one of our local reef hobbyists likes to say, "Stability promotes success."

Who could argue with that?

I'm sure that you can think of tons of ways that consistency in our fish-keeping habits can help promote more healthy, stable aquariums. Don't obsess over this stuff, but do give some thought to the discussion here; think about consistency, and how it applies to your animals, and what you do each day to keep a consistent environment in your systems.

And don't be fucking lazy.

Don't look for magic potions, shortcuts, or hacks. Good stuff takes time to achieve.

Stay observant. Stay methodical. Stay diligent. Stay grounded. Stay consistent...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

The smallest allies...

In the botanical-style aquarium, we embrace so many previously under-appreciated and seldom-discussed (in aquarium circles, anyways) aspects of Nature. None to me is more profound than the way in which we as an aquarium movement have come to appreciate the "microbiome"- defined as a community of microorganisms (such as bacteria, fungi, and biofilms) that inhabit a particular environment.

In our case, the environment is our botanical-style aquariums.

And that's a fundamental thing for us- "recruiting" and nurturing the community of organisms which support our aquariums. In fact, one could safely assert that the whole basis of the botanical-style aquarium is the very materials- botanicals, soils, and wood- which comprise the "infrastructure" of our aquariums. Not only do the botanicals create a physical and chemical environment which supports these life forms, it allows them to flourish and support the life forms above them.

It all starts with bacteria.

We have the beneficial bacteria which facilitate the nitrogen cycle, and play an indespensible role in the function of our little worlds. The botanical-style aquarium is no different; in fact, this is where I start wondering...It's the place where my basic high school and college elective-course biology falls away, and you get into more complex aspects of aquatic ecology in aquariums.

Yet, it's important to at least understand this concept as it can relate to aquariums. It's worth doing a bit of research and pondering. It'll educate you, challenge you, and make you a better overall aquarist. In this little blog, we can't possibly cover every aspect of this- but we can touch on a few points that are really fascinating and impactful.

Many of us are even moving beyond just the pretty look of the botanical-style aquarium, and moving into a deeper stage of understanding how our aquariums function as miniature ecosystems.

And there are other bacteria which we feel will become even more and more important in botanical-style/blackwater/brackish aquairums:

Enter Rhodopseudomonas palustris.

This is an amazing species of what biologists call Purple Non-Sulfur Bacteria (PNSB).

PNSB consume carbon/nutrients in anaerobic environments, thereby competing with microbes that produce toxic metabolites (e.g. hydrogen sulfide). Unlike nitrifying and denitrifying bacteria, they are capable of performing photosynthesis. In addition, they have been demonstrated repeatedly to possess strong probiotic properties that promote the health of diverse aquatic species.

PNSB is found in freshwater, marine and brackish environments (in the water column, the sediments and even in the guts of animals such as corals). This highly adaptive photosynthetic bacterium balances nutrient cycling in all types of aquatic and terrestrial systems. This bacterium is an efficient biodegradation catalyst in both aerobic and anaerobic environments.

Like nitrifying bacteria, PNSB metabolize ammonium and nitrite and nitrate. And they're not just important to the nitrogen cycle. They're also capable of aerobic organoheterotrophy - a process of removing dissolved organics from the water column- just like other microbes!

They're the basis of our latest products, "Culture" and "Nurture'- giving you the biological advantage you need for a successful, biologically diverse botanical-style aquarium.

PNSB are useful for their ability to carry out a particularly unusual mode of metabolism: anaerobic photoheterotrophy. In this process, they consume organic wastes while inhabiting moderately illuminated and poorly oxygenated microhabitats (patches of detritus, leaf litter beds, shallow depths of substrate, deeper pores of expanded clay media, etc.). By competing with other anaerobes such as methanogenic archaeans and sulfate-reducing bacteria for food, these voracious "sludge-eaters" significantly reduce the production of toxic byproducts such as methane and hydrogen sulfide!

PNSB have been used to remediate water quality in highly intensive aquaculture operations for many years. They are increasingly being used to amend soils (particularly soils burnt by chemical fertilizers) in horticultural applications. Their probiotic qualities serve to suppress disease in numerous cultured species.

PNSB absolutely love living as epiphytes on aquatic plants! Specifically, they consume organic waste products that are secreted by the plant. And the plants love them back! PNSB fertilize host plants with their surpluses of fixed nitrogen.

And, perhaps of major interest to those who play with aquatic plants, PNSB is also known to form direct, beneficial associations with the root systems of both terrestrial and aquatic plants!

Ultimately, as they are consumed by bacterivores (protozoa, rotifers, copepods, sponges, etc.). PNSB pass essential biomatter (proteins, vitamins and pigments) along the food chain.

The food chain...As in, "helping to a establish a food chain" in our aquariums. An amazing, fascinating, possibly game-changing embrace of biology in our aquariums.

Food chains. Food production from within the aquarium and its closed ecosystem.

Food production?

Yes, food production.

I mean, it's not really a crazy idea, right? For decades in aquariums, fishes- or more specifically, fish fry- have found sustenance in aquariums, poking around plants and leaves and such as they hide from predators, often hanging on until we net them out to a rearing tank. I'm thinking about the deliberately overgrown "jungle tanks" of my childhood...

And in the botanical-style aquarium, it's even more obvious, as you see adult fishes doing the same thing. Yeah, if you really observe your tank closely- and I'm sure that you do- you'll see your fishes foraging on the botanicals and wood...picking off something.

I've noticed, during times when I've traveled extensively and haven't been around to feed my fishes, that they're not even slightly slimmer upon my return, despite not being fed for days sometimes...

And of course, I've shared with you ad nauseam the deliberate aquariums I've set up to test this theory.

What are they eating in my absence?

Well, there are a number of interesting possibilities.

Well, bacteria and biofilms, for one thing. And then, there are fungi.

Yeah, you heard me. Fungi.

"THOSE guys again?"

Yup. THOSE guys.

Fungi reproduce by releasing tiny spores that then germinate on new and hospitable surfaces (ie, pretty much anywhere they damn well please!). These aquatic fungi are involved in the decay of wood and leafy material. And of course, when you submerge terrestrial materials in water, growths of fungi tend to arise.

And of course, fishes and invertebrates which live amongst and feed directly upon the fungi and decomposing leaves and botanicals contribute to the breakdown of these materials as well! Aquatic fungi can break down the leaf matrix and make the energy available to feeding animals in these habitats.

Fungi tend to colonize wood because it offers them a lot of surface area to thrive and live out their life cycle. And cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin- the major components of wood and botanical materials- are degraded by fungi which posses enzymes that can digest these materials! Fungi are regarded by biologists to be the dominant organisms associated with decaying leaves in streams, so this gives you some idea as to why we see them in our aquariums, right?

And of course, it goes beyond even that...

Because of the very "operating system" of our tanks, which features decomposing leaves, botanicals, soils, roots, etc., we are able to create a remarkably rich and complex population of creatures within them.

This is one of the most interesting aspects of a botanical-style aquarium: We have the opportunity to create an aquatic microcosm which provides not only unique aesthetics- it provides some supplemental nutritional value for our fishes, and perhaps most important- nutrient processing- a self-generating population of creatures that compliment, indeed, create the biodiversity in our systems on a more-or-less continuous basis.

True "functional aesthetics", indeed!

We're really excited to be introducing "Culture" and "Nurture"- products which we feel will have a profound influence on the way we start, maintain, and evolve botanical-style aquariums naturally.

In my opinion, no other hobby speciality is poised to study, appreciate, and embrace the vast diversity and process of Nature like we are in the botanical-style aquarium community.

It's incredibly exciting and humbling to realize that the mental shifts that our community has taken- going beyond just the aesthetics- and really working with Nature, as opposed to fighting Her- will likely yield some of the most important breakthroughs in the history of the aquarium hobby.

And it starts by embracing new ideas, old concepts, and different applications...It starts by embracing the smallest allies...

Stay creative. Stay resourceful. Stay enthralled. Stay excited...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Holding the line... Simple thoughts on evaporation and strategies to counter it.

One of the things I've been obsessive about with my botanical-style aquariums is water exchanges. To me, the one single most important thing we can do as aquarists is to exchange water. And of course, the whole idea of water exchanges is to create stability in your aquarium's environment. This is pretty much "Aquarium Keeping 101", and we all know this, right?

And then there is what happens between water exchanges: Evaporation...and how we manage it...

Evaporation is a pretty big deal. And it has immediate impact on the environmental stability of our aquariums. Dissolved solids, minerals, organics, and salt ( when present) do not evaporate. When evaporation occurs in your aquarium, the concentration of substances in the water actually increases as the water volume decreases.

This is important to many fishes, which require stable environmental conditions in order to achieve optimal health.

In marine and brackish water aquariums, the specific gravity of the water can increase significantly as a result of evaporation, if fresh water is not added in an equal volume to replace it. This obviously has health implications for the animals which reside in the aquarium.

Of course, in our botanical-style, blackwater aquariums, evaporation concentrates substances dissolved in the water, changing the environmental parameters over time. Now, we could argue, with our emphasis on experimentation and recreating the shifting water levels of say, African forest streams, rain puddles, and vernal pools, or Brazilian igarape, that water depth varies, and organic substances in the water concentrate, and that this is something our fishes can tolerate.

However, in my opinion, this would be a weaker argument for a closed system aquarium, because there is simply not the volume of flow-through, or even nutrient export processes occurring in our tanks that there happens in Nature, even in all but the tiniest, most stagnant bodies of water (yeah, this little puddles where you find annual killies or wild bettas come to mind).

Now, these gross water-level changes typically occur over longer periods of time in natural systems than they do in the confines of a small aquarium. Rain, atmospheric conditions, runoff, and other phenomenon affect this. And in this instance, the words "tolerate" versus "thrive" are sort of at odds with each other, I think.

All that stuff being equal, the one thing that I am a big believer in with every aquarium that I keep is environmental stability.

Not the mindset of "pegging the pH at 6.3 without any fluctuation", mind you- No, rather, I proffer a stability within a small range. With evaporation, the "range" can become a lot broader, and the fluctuations can happen a lot faster than we'd like. In our aquariums with concentrations of botanicals, the ratio of" pH-reducing/organic input-capable materials" to water obviously increases as the water level decreases.

It's not one of those, "Ohmigod, my tank is going to crash if I don't do something about this right now!" sort of things, but dealing with regular evaporation in the botanical (or brackish) aquarium is an important consideration in the context of environmental stability. Stress from constant environmental fluctuation is a longer-term thing with fishes, yet it can lead to very tangible health issues over time if not addressed.

How much a given aquarium evaporates is based on a myriad of factors, such as the ambient humidity/temperature of the room it's kept in, the time of the year, how wide of an opening the tank has, etc., etc. There is no real "standard formula" of how much a given aquarium will evaporate in a specified amount of time. I've had 300 gallon aquariums that lost 4-5 gallons a week to evaporation, and much smaller tanks that lost that much in a day!

Obviously, in smaller aquariums, the affects of evaporation are more impactful and serious, and some means to address the issue should be considered above and beyond the routine weekly water exchanges.

The easiest way to deal with evaporation is to simply add more water (fresh water in the brackish or marine tank, as the salt concentration will increase as water evaporates). "Well, NO SHIT, SCOTT!"

I'm a freaking genius, I know.

Kind of common sense, but something to think about, right? I'd go so far as to say that some regular "top-off" with freshwater is absolutely vital for the brackish tank, and fairly important for the lower pH, botanical/blackwater aquarium. And of course, we'll no doubt have many heated discussion on the merits of using "pre-tinted" tipoff water versus simply pure RO/DI water in botanical/blackwater tanks..

Keeping track of how much to add isn't particularly difficult, either, as you might guess. Liek, seriously low tech.

You can simply mark the side of your aquarium with a line in an inconspicuous place with permanent marker, and make sure that the water level never decreases below the line during normal operations. This simple and crude visual gives you a decent guide as to how much your water is evaporating on a regular basis. You can even get fancy and use the old standby math formula to determine how many gallons a given measure of water level loss represents (Sorry, metric users, I don't have the exact numbers for the conversion at the top of my head, but it's easy enough to do):

Multiply length by width by height of the tank and divide by 231.

Thusly, if you have a tank that's 48"x14"x20", the product is 13,440. Divide this number by 231 and you get 58.18 gallons. So, if you lost, say, 1/2" inch of height in the water column due to evaporation, that works out to 48x14x.5 = 336. Divide by 231 and you get 1.45 gallons. So...one half of an inch of water loss is equivalent to about 1.5 gallons of water.

Fairly significant, right?

I promise never to demonstrate math again in this blog. I think that is literally the only "formula" I've ever memorized (used to concoct "fantasy fish tanks" in my head for decades!), and I know some math whiz out there is going to be like, "Um, excuuuuuse meee- there is a better way to do this..." So forgive my remedial math skills!

But you get the idea, right?

The simplest way to combat the evaporation issue in the aquarium is to add a little water every day to "hold the line" in your tank. The visual marker makes it easy. However, this simple methodology only works if you're around to do it. Go away on vacation for a week or two, and you're unattended tank will definitely fall behind. Now, will this spell disaster? Likely not, unless you have an overflow weir in the aquarium or rely on a specific water level to keep pumps and heater submerged (and if there is little room for evaporation in this regard).

Yet, again, it's about stability. It's just a "thing" I have. Anything I can do to keep stability in my systems is a good practice. Good habits are always nice to acquire.

Today's ridiculously simple thought, with important impacts.

Stay observant. Stay curious. Stay proactive. Stay engaged...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Eschewing the prep process, and the sheer audacity of being stubborn

As the botanical-style/blackwater aquarium world evolves, we've seen a lot of changes in practices, procedures, and techniques. Here at Tannin, we've spent the better part of the past 5 years attempting to dispel old, outmoded ideas, second-hand "facts", and outright myths in our little niche.

And the battle continues. It's an old hobby story which never really ends. For whatever reason, there are factions within the hobby who imply refuse to accept any idea, practice, or approach which contradicts "long-settled" aquarium hobby thinking. It's almost sort of strange. And shockingly predictable. We've all seen this many times.

You develop an idea or approach, experiment with it, perfect it, have fellow hobbyists replicate it, and there are STILL huge areas of resistance or the perpetuating of misinformation ( largely unintentional, but harmful nonetheless). For whatever reason, a lot of longtime hobbyists simply LOVE to trash on new ideas. Like, really aggressively. And a lot of times, these people are just flat out wrong in their steadfast adherence to (often) outmoded thinking.

Not everyone, of course, but quite a few.

IMHO, it's not just because they're "angry" or whatever...It's because many of these long-established practices WORK. And they work just fine.

Yeah. They do.

However, the real annoying part is that there is a lot of reluctance in some areas to simply consider the potential benefits of a new idea or approach. Couple that with the dogmatic attitude of "your new idea is wrong" and you simply create two hobby communities: One that is open-minded and values new approaches and ideas, and the other which is stubbornly- audaciously- holding on to the past.

In our little niche, for example, there was the perception for decades that blackwater aquariums (I really didn't use the term "botanical-style" here because that's another level of nuance on top of this) were somehow dirty, dangerous, even foolhardy attempts at trying to replicate more natural environmental conditions in the aquarium.

And I admit, the vendors or experts who navigated these waters over the years did little to earn the confidence of the hobby community. Poorly explained rationales for the new approaches, products with very vague descriptions or efficacy, and a lot of "trust me" sort of stuff.

I think the resistance that we initially encountered to the version of the blackwater/ brackish, botanical-style aquarium that we push here is part the result of some of the incomplete work of those who came before us, and the general stubbornness of some of the loudest corners of he mainstream aquarium world.

When we burst forth on the scene, we made the deliberate decision to share our ideas and our approach even before we started offering products. We felt it necessary to explain our philosophy and the rationale for why we advocate the ideas that we do. It made for a much, much slower growth and market penetration for Tannin Aquatics ; however, those of you who follow us should have no confusion as to where we stand, why we favor the approaches that we do, and what we believe in as a brand.

Now, let me be clear- there were a LOT of people doing stuff the right way. Plenty of open-minded, detail-oriented hobbyists sharing their ideas on this speciality, refusing to be shouted down by the louder, more stubbornly resistant factions in the hobby.

I still see so much stubbornness and confusion sowed by those who simply refuse to do the research, either by themselves, or through studying the vast body of free information that's now out there. Now, Im not saving that MY ways is the only way, or even the BEST way...however, I think it's a pretty GOOD way! Recently, I saw a post on a forum where hobbyists were debating the merits of preparation of botanicals...an absolutely fundamental aspect of the botanical-style aquarium approach.

Even within our movement, there is stubbornness, opinion, and misinformation.

There was a surprisingly large amount of responses which simply indicated that you should just "dump stuff in", or if you DO prep, that you could "use the water you boiled the botanicals in as a home made blackwater extract..." Stuff that we've talked about so much here- and so clearly stated our rationale for our approach- that it's almost fun that people still ask us our position on it.

Of course, it's worth covering this topic one more (hopefully not agonizing) time:

Why, Scott? Why do we recommend boiling or steeping this stuff?

Well, to begin with, consider that boiling water is used as a method of making water potable by killing microbes that may be present. Most nasty microbes "check out" at temperatures greater than 60 °C (140 °F). For a high percentage of microbes, if water is maintained at 70 °C (158 °F) for ten minutes, many organisms are killed, but some are more resistant to heat and require one minute at the boiling point of water. (FYI the boiling point of water is 100 °C, or 212 °F)...But for the most part, most of the nasty bacteria that we don't want in either our tanks or our stomachs are eliminated by this simple process.

Ten minutes of boiling is "golden", IMHO. Of course, we boil for other reasons, as we'll touch on in a bit.

For one reason, we boil botanicals to kill any possible microorganisms which might be present on them. And of course, there's the simple reason that...they're dirty. Why the fuck do you want "dirt" or pollutants" in your aquarium? To provide some point t? To be "rebellious?" I have no idea.

Leaves, seed pods, etc. have been exposed to rain and dust and all sorts of things in the natural environment which, in the confines of an aquarium, could introduce unwanted organisms and contribute to the degradation of the water quality.

The surfaces and textures of many botanical items, such as leaves and seed pods lend themselves to retaining dirt, soot, dust, and other atmospheric pollutants that, although likely harmless in the grand scheme of things, are not stuff you want to start our with in your tank.

So, we give all of our botanicals a good rinse.

Then we boil.

Boiling also serves to soften botanicals.

If you remember your high school Botany, leaves, for example, are surprisingly complex structures, with multiple layers designed to reject pollutants, facilitate gas exchange, drive photosynthesis, and store sugars for the benefit of the plant on which they're found. As such, it's important to get them to release some of the materials which might be bund up in the epidermis (outer layers) of the leaf. As we get deeper into the structure of a leaf, we find the mesophyll, a layer of tissue in which much of photosynthesis takes place.

We use only dried leaves in our botanical style aquariums, because these leaves from deciduous trees, which naturally fall off the trees in seasons of inclement weather, have lost most of their chlorophyll and sugars contained within the leaf structures. This is important, because having these compounds present, as in living leaves, contributes excessively to the bioload of the aquarium when submerged...

Are there variations on this theme?

Well, sure.

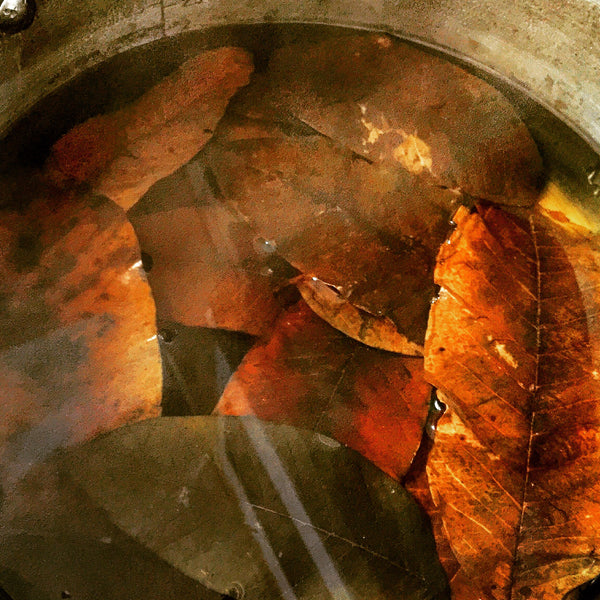

Many hobbyists rinse, then steep their leaves rather than a prolonged boil, for the simple fact that exposure to the newly-boiled water will accomplish the potential "kill" of unwanted organisms, which at the same time softening the leaves by permeating the outer tissues. This way, not only will the "softened" leaves "go to work" right away, releasing the beneficial tannins and humic substances bound up in their tissues, they will sink, too!

And of course, I know many who simply "rinse and drop", and that works for them, too! And, I have even played with "microwave boiling" some stuff (an idea forwarded on to me by Cory Hopkins!). It does work, and it makes your house smell pretty nice, too!

It's not a perfect science- this botanical preparation "thing."

However, over the years, aquarists have developed simple approaches to leaf prep that work with a high degree of reliability. Now, there are some leaves, such as Magnolia, which take a longer time to saturate and sink because of their thick waxy cuticle layer. And there are others, like Loquat, which can be undeniably "crispy", yet when steeped begin to soften and work just fine.

So why do we soak after boiling?

Well, it's really a personal preference thing.I suppose one could say that I'm excessively conservative, really.

I feel that it releases any remaining pollutants and undesirable organics that might have been bound up in the leaf tissues and released by boiling, which is certainly arguable, but is also, IMHO, a valid point. And since we're a company dedicated to giving our customers the best possible outcomes- we recommend being conservative and employing the post-boil soak.

The soak could be for an hour or two, or overnight...no real "science" to it. Some aquarists would argue that you're wasting all of those valuable tannins and humic substances when you soak the leaves overnight after boiling. My response has always been that, sure, you might lose some, but since the leaves have a "lifespan" of weeks, even months, and since you'll see tangible results from them (i.e.; tinting of the water) for much of this "operational lifespan, an overnight soak is no big deal in the grand scheme of things.

Besides, do we even have a way to measure how much of the "good stuff"- and what it is- that we are both receiving or potentially losing- by doing this?

We don't.

So, rather than being a total ass, my advice to you is simply to do what's most comfortable for you- and what you feel is best for your fishes.

When it comes to to other botanicals, such as seed pods, the preparation is very similar. Again, most seed pods have tougher exterior features, and require prolonged boiling and soaking periods to release any surface dirt and contaminants, and to saturate their tissues to get them to sink when submerged!

And quite simply, each botanical item "behaves" just a bit differently, and many will require slight variations on the theme of "boil and soak", some testing your patience as they may require multiple "boils" or prolonged soaking in order to get them to saturate and sink.

Yeah, those damn things can be a pain!

However, I think the effort is worthwhile.

Now, sure, I hear tons of arguments which essentially state that "...these are natural materials, and that in Nature, stuff doesn't get boiled and soaked before it falls into a stream or river."

Well, shit, how can I argue with that?

The only counterargument I have is that these are open systems, with far more water volume and throughput than our tanks, right? Dilution. Nature might have more efficient, evolved systems to handle some forms of nutrient excesses and even pollution. It's a delicate balance, of course.

In the end, preparation techniques for aquatic botanicals are as much about prevention as they are about "preparation."

By taking the time to properly prepare your botanical additions for use in the aquarium, you're doing all that you can to exclude unwanted bacteria and microorganisms, surface pollutants, excess of sugars and other unwelcome compounds, etc. from entering into your aquarium.

Another component of the prep process- and one of the things that I have an issue with in our little hobby sector is the desire by many "tinters" to make use of the water in which the initial preparation of our botanicals takes place in as a form of "blackwater tea" or "blackwater extract."

Now, while on the surface, there is nothing inherently "wrong" with the idea, I think that in our case, we need to consider exactly why we boil/soak our botanicals before using them in the aquarium to begin with.

I personally discard the "tea" that results from the initial preparation of botanicals- and I recommend that you do, too. Here's why:

As I have mentioned many times before, the purpose of the initial "boil and soak" is to release some of the pollutants (dust, dirt, etc.) bound up in the outer tissues of the botanicals. It's also to "soften" the leaves/botanicals that you're using to help them absorb water and sink more easily. As a result, a lot of organic materials, such as lignin, proteins, and other stuff, in addition tannins and humic substances- are released.

"Hey, that's the stuff that adds the tint to our tanks, right?"

Well, yeah. However...

It's also filled with a complex "brew" of other stuff. Stuff that you likely don't want in your aquarium.

So, why the hell would you want a concentrated "tea" of dirt, surface pollutants, and other organics in your aquarium as a home-brewed "blackwater extract?" And how much do you add? I mean, what is the "concentration" of desirable materials in the tea relative to the water? I mean, it's not an easy, quick, clean thing to figure, right?

There is so much we don't know. We're just learning how to utilize the botanicals themselves correctly and safely; is it wise to use concentrated waste extract to our tanks?

Again, a lot of hobbyists tell me they are concerned about "wasting" the concentrated tannins from the prep water. Trust me, the leaves and botanicals will continue to release the tannins and humic substances (with much less pollutants!) throughout their "useful lifetimes" when submerged, so you need not worry about discarding the initial water that they were prepared in.

In my opinion, it's kind analogous to adding the "skimmate" (the nasty concentrated organics removed by your protein skimmer via foam fractionation in your marine aquarium) back into your aquarium because you don't want to lose the tiny amount of valuable salt or some "trace elements" that are removed via this process.

Is it worth polluting your aquarium for this?

I certainly don't think so!

It isn't. We need not be stubborn about this stuff.

The simple truth about using botanicals is that you're adding natural terrestrial materials that, when acted upon by bacteria, break down in your aquarium, increasing the bioload of the system. We've said it thousands of times over the past few years, and we'll say it again here- you need to add botanical materials to your aquarium slowly, over a period of days or weeks. You have to be careful. You have to observe, test, and adjust.

Think about it: It's not really a revelation. Adding large quantities of ANYTHING in a short period of time into your established aquarium could cause some issues.

Like so many things in our evolving "practice" of perfecting the blackwater, botanical-style aquarium, developing, testing, and following some basic "protocols" is never a bad thing.

Being open-minded isn't a bad thing. Niether is being critical when it something sounds a bit off.

And understanding some of the "hows and whys" of the process- and the reasons for embracing it-will hopefully instill into our community the necessity- and pleasures- of going slow, taking the time, observing, tweaking, and evolving our "craft"- for the benefit of the entire aquarium community.

We need to remain open to new ideas...and even stubborn guys like me need to be able to take criticism and consider revising our positions when we're wrong. However, being stubborn just for the sake of being stubborn is simply not being "smart."

It's audacious.

Something to think about, right?

Stay open-minded. Stay thoughtful. Stay curious. Stay bold. Stay informed...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Under "cover..."

A funny thing happens when terrestrial materials make contact with water: They start to recruit "stuff" on their surfaces. Scientists refer to this "stuff" as "periphyton." Periphyton is a mix of algae, heterotrophic microbes, detritus, and cyanobacteria growths that is attached to submerged surfaces in aquatic ecosystems.

In the hobby, we tend to give it the rather user-friendly moniker of "biocover."

Like it or not, it's found in Nature and in the aquarium almost universally. It's not a reflection on your tank maintenance capabilities, or an indication that your tank is somehow "dirty." Rather, it's an important foundation for food sources, recycling and assimilation of nutrients, and the physical removal of detritus and other particulate matter.

Of course, to many hobbyists, it's considered "unsightly" or "sloppy." To the enlightened, botanical-style aquarium enthusiast, "biocover" is a thing of beauty...an indicator that Nature is doing what she's supposed to do to take advantage of the resources available to Her within the ecosystem, for the benefit of all the organisms which reside there.

Some of the most compelling things in natural aquatic habitats- and in the aquariums which we create to represent them- are large branches, fallen trees, logs, and roots extending from the terrestrial habitat below the waterline.

The result of a tree, branch, or root system which finds its way into the water is a physical, environmental, and water-flow-dynamic-changing feature in the habitat.

I love fallen trees and branches.

I love what they can do. What they can bring to an aquatic environment.

I love how they inspire us.

I love the idea of doing an aquarium in which the primary feature is a big old piece of wood, covered in biofilm, algae, and other life forms.

Notice I didn't say "aquatic moss?" Why? Well, besides the fact that it's sort of an aquascaping contest cliche by now, I don't think it looks all that "authentic." Although I like the look of these features, personally, I have yet to see a moss-covered log in the Amazon region, or in an Asian blackwater swamp, and we need to accept- not fight- some of what really happens in Nature, and readjust our aesthetic sensibilities to understand what is really natural beauty.

It's not all neat and orderly and crisp green on brown.

It's just not.

As we've mentioned numerous times here, Nature is not exactly a neat and tidy, perfectly-ratioed place. Rather it's often a world of chaos, randomness, detritus, biofilms, and fungal growth.

I think we have to sort of "desensitize" ourselves from the stigma of "biocover" on our wood. Now, I know, this idea undermines a century of aquarium-keeping/aquascaping dogma, which suggests that wood in the aquarium must be pristine, and without anything going on it (outside of the aforementioned mosses, in the last decade or so). As hobbyists, we often obsessively remove this stuff as fast as it appears- not only denying Nature a chance to appear in Her most raw and elegant state- we're also simultaneously removing a critical microhabitat which provides environmental stability.

And of course, that's really sort of antithetical to what happens in Nature!

When terrestrial materials fall into the water, opportunistic life forms, ranging from algae to fungi to bacteria- even sponges-will colonize the available space, eking out a living as they compete for resources. In addition to helping to break down some of these terrestrial materials, the life forms that inhabit submerged tree branches and such reproduce rapidly, providing forage for insects and aquatic crustaceans, which, in turn are preyed upon by fishes.

Yeah, a food chain...started by a piece of tree that fell in the forest, and was covered by water during periods of inundation.

If you look at the way the "biocover" grows on these materials, it's obvious that it does so in a manner which helps it absorb light, dissolved oxygen, and nutrients from the water column. The largest, broadest surfaces are covered.

These mats of periphyton- what many hobbyists would characterize as "unsightly growth" are some of Nature's most beautiful and elegant systems, optimized to exploit the dynamic environment in which they are situated. An enormous abundance of life is present, if we just take a few minutes to look for it, and appreciate it.

I think that we can "ease into" appreciating the periphyton by setting up aquariums to provide optimum conditions for them to appear and multiply...and then leaving them undisturbed. That is, a system with lots of different exposed woodsurfaces and a network of roots. An irresistible subject for a natural-looking- and functioning- aquascape!

And relatively easy to execute, too!

With a variety of interesting natural materials readily available to us, it's easier than ever to recreate these habitats in as detailed a version as you care to do.

And the inspiration is literally everywhere in Nature. All you need to do is open your eyes, and instead of "mentally editing" all of the "unsightly" growth, embrace what it looks like sand think about its function and the benefits it brings.

A good starting point on your road to appreciating the periphyton is to consider the very structure of the aquatic habitats that we are inspired by, and thinking about what forces and circumstances helped create them- and why fishes are attracted to them. Look at the way rocks, soil and branches come together in Nature to form interesting physical spaces that fishes utilize for protection, foraging, and reproduction.

By replicating the complex look and physical attributes of these features, including rich substrate, roots of various thickness, and leaves, we offer our fishes all sorts of potential microhabitats. In the aquarium, we tend to focus on the "macro" level- creating a nice wood stack, perhaps incorporating some rock- but we seldom see the whole picture allowed to come together in a more natural way.

This was what has inspired me in most of my latest iterations of my home aquariums. The interaction between the terrestrial elements and the aquatic ones is so compelling. Allowing terrestrial leaves to accumulate naturally among the "tree root structures" that I have created fosters this more natural-functioning environment.

As the leaves and roots begin to soften and ultimately break down, they will foster microbial growth, biofilms, and fungal growths- all of which will provide supplemental foods for the resident fishes...just like what happens in Nature.

Facilitating these processes- allowing the materials to accumulate naturally and break down "in situ" is a key component of replicating and supporting these microhabitats in our aquariums. The typical aquarium hardscape- artistic and beautiful as it might be, generally replicates the most superficial aesthetic aspects of such habitats, and tends to overlook their function- and the reasons why such habitats form.

We can- and should- go further.

Now, we see many aquariums which feature wood and leaves, of course. However, I think we don't see a tremendous use of smaller branches, roots, and "twig-sized" pieces, and I think that is something we would definitely like to see more of in our aquariums. There is something remarkably realistic about the presence of these smaller materials in an aquarium.

A throwback to simplicity?

I think about the idea of simplicity in our aquariums quite bit.

Not just the idea of less "gear", but a more simplistic means of operating an aquarium. Relying on Nature to do more of the work..Rather than trying to circumvent or skip processes altogether, I think that we can lean on Nature more than we have been doing in recent years.

We can return to simplicity- even while trying to recreate some of Nature's most elegant and complex habitats in our aquariums.

Now, sure, this is hardly a revolutionary concept. It's not some "new idea", of course. In the modern aquarium hobby's earliest days, filters and heaters were uncommon, if available at all, to most hobbyists. It really wasn't until the 20th century that such technological means to keep aquariums was commonplace. Of course, the simple reality was that most hobbyists relied more on the "balanced aquarium" concept.

The "balanced aquarium" idea was really the first sort of application of the aquarium as a microcosm" concept. Back in the Victorian era, the balanced aquaria was viewed as a system in which plants and fish could live for years in the same water as long as the ratio of plants and fish were “balanced.”

Now, the whole idea of no water changes is, IMHO, an absurd exercise in laziness. Eventually, that kind of laissez faire approach will come back to bite you on the ass. So, that part of the "equation" is a big NO, IMHO.

I suppose a more modern definition of the idea of a "balanced aquarium" is an approach in which plants and animals interact within the confines of the aquarium to produce a stable environment. Okay, that was a really "weak sauce" definition by me, but the point of this piece is not to re-hash this well-trodden idea. It's to discuss the idea of running a botanical-style aquarium in a more simple manner.

Now, there is another part of the "balanced aquarium" idea that I can get on board with: It's the idea that the aquarium should provide a significant amount of surface area. In a perfect world, the width of the aquarium should be equal to, and the length double at least of the depth to provide a surface area adequate for gas exchange to take place in an efficient manner.

I think that is applicable to almost any type of aquarium, really.

Okay, let me just cut to the chase...

I think that the botanical-style aquarium can be run with a minimal amount of technical gear.

I think you need the aforementioned gas exchange, facilitated by an aquarium with sufficient surface area. That's a given.

You'd probably want some water movement, and maybe just a bit of surface agitation. I think you could facilitate this water movement and surface agitation with a little surface skimmer, like the ones made by Eheim, Ultum Nature Systems, and Azoo, just to name a few. These are super-cool little devices, as they help remove the surface film caused by an organic-protein layer, facilitating gas exchange. As a plus, the return form these skimmers provide a little bit of water movement.

I'm currently running an ADA 60F (24"x12"x7"/ 60x30x18cm) aquarium, which is about 8.6 U.S. gallons in capacity, solely with one of these devices. It works great!! My previous iteration, the (now famous, to readers of this blog) "leaf litter only" Paracheirodon simulans tank, ran for over a year like this with tremendous success.

Short of not having any device at all, this is likely as simple as I'd run a botanical-style aquarium. Maybe an auto top-off, but nothing else.

Simple.

In a botanical-style aquarium run in this manner, you do have some challenges, of course. You need to stock carefully, being sure not to over-stock your system with fishes- or botanicals- at least, not at once, and not while up and running. We've already talked about the perils of going too fast, too soon. Going slowly and patiently is a long-known key to success with botanical-style aquariums.

Now, nothing is perfect.

Nothing we can tell you is an absolute guarantee of perfect results...You're dealing with natural materials, and the results you'll see are governed by natural processes that we can only impact to a certain extent by applying logic and common sense.

And when it comes time to adding your botanicals to your aquarium, the second "tier" of this process is to add them to your aquarium slowly. Like, don't add everything all at once, particularly to an established, stable aquarium. Think of botanicals as "bioload", which requires your bacterial/fungal/microcrustacean population to handle them.

Bacteria, in particular, are your first line of defense.

If you add a large quantity of any organic materials to an established system, you will simply overwhelm the existing beneficial bacterial population in the aquarium, which will likely result in a massive increase in ammonia, nitrite, and organic pollutants. At the very least, it will leave oxygen levels depleted, and fishes gasping at the surface as the bacteria population struggles to catch up to the large influx of materials.

This is not some sort of esoteric concept, right? I mean, we don't add 25 3-inch fishes at once to an established, stable 10-gallon aquarium and not expect some sort of negative consequence, right? So why would adding bunch of leaves, botanicals, wood, or other materials containing organics be any different?

It wouldn't.

And then there's that whole idea of the botanicals themselves functioning as the "filter" of the system, specifically in botanical or leaf litter beds.

I've had some conversations with more science-minded botanical aquarists who postulate about the possibilities of fostering some form of denitrification in deeper botanical beds, and it is interesting! One of the questions that seems to come up a lot in this context is the extent to which hydrogen sulfide or other undesirable compounds can build up in a deep bed of compacted botanical materials.

In a botanical bed with materials placed on the substrate, or loosely mixed into the top layers, will it all "pack down" enough to the point where there is a complete lack of oxygen and we develop a significant amount of hydrogen sulfide or other nasty compounds in our tanks?

I think that we're more likely to see some oxygen in this layer of materials, and I can't help but speculate that actual de-nitirifcation (nitrate reduction), which lowers nitrates while producing free nitrogen, might actually occur in a "deep botanical" bed.

And it's certainly possible to have denitrification without dangerous hydrogen sulfide levels. As long as even very small amounts of oxygen and nitrates can penetrate into the substrate this will not become an issue for most systems. I have yet to see a botanical-style aquarium where the material has become so "compacted" as to appear to have no circulation whatsoever within the botanical layer.

Now, I base this on visual inspection of numerous tanks, and the basic chemical tests I've run on my systems under a variety of circumstances. I could still be wrong.

There is so much we don't know about running our botanical-style aquariums in a variety of formats. The one thing that we DO know is that they require us to make a certain mental shift.

And managing a botanical-style aquarium system at it's most simple requires discipline.

Yeah, it IS cool to toss in leaves and seed pods and soil and such, and allow them to break down in an aquarium- but that doesn't lead to an easy path to success for a lot of people. It's reproducible- but only to those who practice more careful, consistent husbandry, observation, and possess- or acquire- extreme patience. Only to those who putter faith in Nature and her smallest organisms, like bacteria, fungal growths, and biofilms.

So, while it seems like it would be nothing but fun to embrace the ultra simplicity of a minimally-equipped botanical-style aquarium, it's important to remember that experimentation on. simple systems requires us to engage with, and at least attempt to understand complex ideas.

I personally think that's kind of fun!

Stay intrigued. Stay engaged. Stay excited. Stay curious...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Pushing through...

There seems to be a stage in all types of aquariums where stuff sort of “challenges” you in some way…Maybe the tank is settling in and showing signs of algae growth. Perhaps, as in our case, there is a lot of biofilm or fungal growth starting to show. Stuff which challenges our aesthetic preferences, or makes us doubt the validity of our plans..

These are things that make or break our hobby...those things which challenge our fortitude. And how we face them...how we deal with them, or accept them- is where the magic lies.

In botanical-style aquariums, we see this a lot.

Almost all of of my botanical-style aquariums hit a stage, early on in their evolution, in which the tank looked...well, kinda bad.

What we expect in our world is that stuff will start out with lots of cloudiness, turbidity, and fungal growths. And it's a bit nerve-wracking to see your perfectly-thought-out display starting out as a cloudy, biofilm-and-fungal-growth-wracked ecosystem.

It takes time. And patience.

Two factors which aquarists are always seemingly challenged by. Remember, botanical-style aquariums are not static. They are NOT like planted aquariums, in which you can achieve a near-desired result from day one, by simply packing your tank with plants of the type and size that you're envisioning in your finished product.

Rather, these systems take weeks, even months, before they start looking like we might envision them. You need to take a very long term view.

And it's easy to think about this as you would a natural aquatic system. Remember, natural systems are constantly changing and evolving as external factors, such as weather, additions of materials from the surrounding terrestrial environment, and internal ones, such as the migration of fishes into and out of them, or the growth of biofilms and other epiphytic life forms. The fundamental changes which occur as terrestrial habitats transform into aquatic ones are also responsible for so many changes.

It's easy to lose sight of the fact that many of the "barriers" which challenge us, and often even leave us discouraged- are but mere "stepping stones" on the long journey towards a stable, attractive, ecologically diverse closed ecosystem.

Yet, we see those things happen in our tanks, and we worry. And occasionally, we doubt ourselves.

I believe that every hobbyist, experienced or otherwise, has those doubts; asks questions- goes through the "mental gymnastics" to try to cope: "Do I have enough flow?" "Was my source water quality any good?" "Is it my light?" "When does this shit go away?" "It DOES go away. I know it's just a phase." Right? "Yeah, it goes away?" "When?" "It WILL go away. Right?"

I mean, it's common with every new tank, really.

The waiting. The "not being able to visualize a fully-stocked tank "thing"...Patience-testing stuff. Stuff which I- "Mr. Tinted-water-biofilms-and-decomposing-leaves-and-botanicals-guy"- am pretty much hardened to by now. Accepting a totally different look. Not worrying about "phases" or the ephemeral nature of some things in my aquarium.

Because I know. I've made the mental shits. I accept what happens. And I understand that it's often "just a phase"- part of the process. And I enjoy watching Nature do her work.

You should, too.

Make it a point, when you start out with a botanical-style aquarium, to understand what to expect. Consider what happens in Nature, and use that as your "barometer."

Enjoy every phase.

Push through early doubts.

Todays simple, but easy-to-forget idea that we all need to remind ourselves about from time to time.

Stay resilient. Stay brave. Stay engaged. Stay creative...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Mixing it up: Going against what we know and love.. "Substrate Edition"

As you know by now, I have an obsession with substrates. Maybe even a fetish of sorts. Like, I really am into them.

And one of the thing I’m into is “sediments.”

Yeah, I've always looked substrate materials the way other people look at cocktails: It's about mixing stuff. Yeah, seriously. That was sort of the genesis for our soon-to-be-released“NatureBase” substrates.

A mind set.

Now, in Nature, there are numerous factors which contribute to the composition of substrates in wild aquatic habitats, including geology, the flow velocities of the body of water, the surrounding topography, the seasonal variations in water level (ie; inundation/dessication cycles), and accumulation of materials from the surrounding terrestrial environment.

So, why do we as hobbyists, who want to create the most realistic approximations of wild habitats possible, just "mail it in" when it comes to substrate? I mean, just open a bag of _____________ sand or whatever, and call it a day and move on to he more "exciting" parts of our tank?

I think we just rely on the commercially available stuff and that's that.

Sad.

Now, in defense of the manufacturers of sands and gravels for aquarium use- I love what they do, and what they have available. These items are of generally excellent quality, provide a wide range of choices for a variety of applications, and are readily available.

However, IMHO, they are a great "starting point" for creating more dynamic substrates for our aquariums. Kind of like tomato puree is to pasta sauce...a beginning! Sure, you can use just the puree and enjoy your sauce, but isn't it always better to add a bit of this and that and build on the "base"to create something better?

Totally.

Or, you could use some of the stuff we've been playing with.

Of course, here's a little advice: The "NatureBase" substrates are not your typical aquarium substrates.

The idea of they were really created to replicate the substrate materials found in the igapo and varzea habitats of South America, and the overall habitat- more "holistically conceived"-not specifically for aquatic plant growth. And, in terrestrial environments like the seasonally-inundated igapo and varzea, nutrients are often lost to volatilization, leaching, erosion, and runoff..

So, it's important for me to make it clear again that these substrates are more representative of a terrestrial soil, and are not specifically formulated to grow aquatic plants luxuriously. Interestingly the decomposition of detritus and leaves and such in our botanical-style aquariums and "Urban Igapo" displays is likely an even larger source of “stored” nutrients than the CEC of the substrate itself, IMHO.

An added benefit of these types of substrates is that they will provide a home for beneficial bacteria- breaking down organics and helping to make them more available for plant growth.

That being said, the stuff DOES grow aquatic and riparian plants and grasses quite well, in our experience! Yet, I would not refer to them specifically as "aquatic plant substrates." They're not being released to challenge or replace the well-established aquatic plant soils out there. They're not even intended to be compared to them!

Remember, our substrates are intended to start out life as "terrestrial" materials, gradually being inundated as we bring on the "wet season." And because of the clay and sediment content of these substrates, you'll see some turbidity or cloudiness in the water. Like, for weeks. It won't immediately be crystal-clear- just like in Nature. That won't excite a typically planted aquarium lover, for sure. And no, we haven't done CEC testing with our substrates...It's likely that in some future, some enthusiastic and curious scientist/hobbyist might just do that, of course!

Takeaway: These substrates, because of their unique composition, will create highly cloudy water if you flood it immediately before a "terrestrial" phase. It will take weeks of submersion before you achieve that sort of crystal clarity which we love so much.

I can't stress it often enough: With our emphasis on the "wholistic" application of our substrate, our focus is on the "big picture"- not specifically aquatic plant growth. Yet, hobbyists being hobbyists, I'm sure that they will evaluate them based upon this ability, so I felt that I should at least address this topic at this juncture.

And the whole thing about "soupy" water, with some turbidity and even a bit of cloudiness to it, is part of the game. It's also very similar to the conditions you see in recently flooded forest floors and meadows.

A whole part of the use of different substrate materials borders on the same mindset we embrace with botanical-style blackwater aquariums in general: The acceptance of natural aquatic systems as they really appear- not as we would like them to appear.

It's tough to stomach this stuff sometimes. It goes against the way we look at stuff as hobbyists. It goes agains the "norms" in a big way...I mean, why would you knowingly put stuff in your aquarium which makes it look less like this?

And more like this?

Well, because it's more like what Nature really looks like.

In many aquatic systems, you'll not only see the turbidity caused by sediments and mud, you'll see a lot of "humus" and coverage created by decomposing grasses and tangles of submerged terrestrial plant roots.

Algal mats which arise from these decomposing materials trees form an important food source and grazing area for many fishes.

And the fine particulate matter which accumulates in the sediment layer is used for sustenance by a huge variety of organisms, some which feed directly on it, and others which filter it from the water or accessing it in the sediments that result. These allochthonous materials support a diverse food chain that's almost entirely based on our old friend, detritus!

The idea of a substrate forming a dynamic basis for an underwater habitat of diverse life forms is a fundamental difference as compared to approaches that we've embraced in decades past. We're pretty excited to see many hobbyists running with this idea, going with mixes of different terrestrial materials in and on the substrate to more realistically represent Natural habitats in their aquariums.

It's an exciting shift in thinking and tactics!

It's something that I keep coming back to, because the idea of utilizing botanical materials in your aquarium substrate keeps tantalizing me with its performance and potential benefits.

I've worked with this stuff for a long time, and I'm super excited about this approach.

As I've obsessively reported to you, I recently ran a small tank in my office for the sole purpose of doing damn near the entire substrate with leaves and twigs- sort of like in nature. There was less than approximately 0.25"/0.635cm of sand in there. That was the whole "scape." What we in the reef world call a "no scape."

Leaves and a shoal of Parachierdon simulans.

Nothing else.