- Continue Shopping

- Your Cart is Empty

Roads Less Travelled: A different take on "the same old thing..."

We cover a lot of ground here at Tannin.

Not just in the blackwater/botanical-style arena, but in the overall "natural" approach to creating captive aquatic ecosystems. That approach often involves embracing ideas, aesthetics, and environmental characteristics which run somewhat contrary to what we've been indoctrinated to believe are "proper" aquarium conditions.

Yeah, we've talked about this stuff before.

However, as the hobby speciality evolves more, it's important to re-visit this idea repeatedly, lest we paint ourselves into a metaphorical "corner", unwilling to try some new things for fear of "violating" what one could call "conventional" aquarium keeping ideas.

And of course, it always goes back to Nature...

A high percentage of the natural habitats from which many of our fishes hail are perhaps not even all that "conventional" by aquarium/aquascaping standards. Often, it's a sediment-filled tangle of twigs and leaves...not everyone's idea of "attractive" for aquarium purposes- but it's very, very authentic in many cases. And I think it's one of those things that you have to actually execute to appreciate.

Of course, there ARE many habitats which seem to play right into our long-held beliefs of just how a "healthy, attractive aquarium" should look. Nature offers a "prototype" for just about anything we want- if we look hard enough!

Of course, Nature also has habitats which, from an aesthetic standpoint, are remarkably "simple", yet bely a complexity of biology, geology, and environmental interdependencies. Habitats which, if we are willing to consider replicating in our aquariums, could provide remarkable insights and "unlocks" into the lifestyles and reproductive habits of our fishes.

I believe that experiments with alternative substrate materials, use of different wood or root-like materials, and even simple elements such as twigs, can help open up new discoveries in the aquarium hobby realm.

Of course, the "roads less travelled" include those habitats which consist of the flooded meadows/forests, and muddy ditches which we've talked about so much here. Again, the idea of land taken over by water yields a host of possibilities and unusual opportunities to explore the life cycles of many unique fishes.

And of course, utilizing these materials to create more realistic approaches to habitat replication involves accepting stuff like tint and our old apparent foe, turbidity.

Our aesthetic "upbringing" in the hobby seems to push us towards "crystal clear water", regardless of whether or not it's "tinted" or not! For some reason, we blindly associate "clear" water with "cleanliness" in our aquariums, and in Nature.

Think about this: You can have absolutely horrifically toxic levels of ammonia, dissolved heavy metals, etc. in water that is "invisible", and have perfectly beautiful parameters in water that is heavily tinted and even a bit turbid.

We need to stop thinking about perfectly clear water (tinted or otherwise) as an absolute indicator of cleanliness and suitability for tropical fishes.

(FYI, WIkipedia defines "turbidity" in part as, "...the cloudiness or haziness of a fluid caused by large numbers of individual particles that are generally invisible to the naked eye, similar to smoke in air.")

That's why the aquarium "mythology" which suggested that blackwater tanks were somehow "dirtier" than "blue water" tanks used to drive me crazy. The term "blackwater" describes a number of things; however, it's not a measure of the "cleanliness" of the water in an aquarium, is it?

Nope. It sure isn't.

Color alone is not indicative of water quality for aquarium purposes, nor is "turbidity." Sure, by municipal drinking water standards, color and clarity are important, and can indicate a number of potential issues...But we're not talking about drinking water here, are we?

No, we aren't!

There is a difference between "color" and "clarity."

Like many of the ideas about aquariums we proffer here, you'll need to make some mental shifts to enjoy this look. You'll likely face the usual criticisms from dark corners of the Internet, criticizing your use of alga and detritus-filled hardscape as "the result of lackadaisical husbandry practices" and "low standards of cleanliness..."

Been there, heard that shit.

Right?

And sure, perhaps you will have to point to videos and photos of the many wild habitats which reflect these features in order to "vindicate" yourself among your peers.

Taking the roads less travelled in the aquarium hobby is not only fascinating and educational, it's seen as a bit "rebellious", so you'll need to have a thick skin. Perhaps you'll have to swallow your pride and eat some shit now and again if your experiment doesn't quite live up to your expectations...

Surprisingly, you'll find that most of your experiments with these unique types of habitats will not only meet your expectations- they'll often exceed them significantly!

Despite what the "experts" tell you.

The beauty of taking the "roads less travelled" in the aquarium hobby is that you'll almost always gain something from the journey- be it insights into a unique habitat you've been drooling over, or success with fishes that you've previously been stymied by.

Embrace the unusual.

You never know where it might take you.

Stay observant. Stay creative. Stay bold. Stay inspired...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

"Flexible" aspirations?

One of the great things about botanical-style aquariums is that you can have a fully thought-out plan for your aquarium, start your tank, and ultimately end up with something completely different than what you intended. "Perfect ideas" are often those which allow for such evolution and change over time.

In our wold, Nature does much of the work...if we trust Her and allow her to do so!

Do you have one of those "perfect ideas" for a tank floating around in your head? The kind which, although not necessarily crazy difficult/expensive to do- just something that you've been itching to try. Something aspirational, or otherwise goal-worthy..that kind of stuff?

If you do, be flexible about it.

Ideas are cool. And they're the easy part.

Seems like I'm always coming up with "perfect ideas" for crazy displays- you know, like biotope-inspired themes, specialized systems for particular fishes, etc....but I never seem to get to all of them. I don't think I'm at all unique in that regard. I think a lot of us have that "perfect tank" in our heads, and we're waiting for factors like time, money, or the right livestock to come our way in order to execute them.

As a young hobbyist, I never could afford anything, so I would fall asleep scheming up these dream tanks in my head...Some of these ideas were insane. Just impossible to execute, Others were very realistic, and as I grew older and had the capability, I was able to build them them.

And often, when I was finally able to build the damn thing, it would come to pass that I didn't enjoy having the tank as much as I enjoyed scheming it!

Why is that?

Some dreams are just meant to be...dreamed, I suppose. Right?

And then there was blackwater.

For some reason, this type of tank really resonated in me. Since I was a kid.

It was so...weird- I mean, a tank with water so dark that you couldn't always see the fishes clearly. It seemed so "anti-establishment" for this teenage fish geek...Maybe that was the start of my experimentation with these kinds of tanks. I began with peat moss in my killie tanks, then played around with sticks and leaves and before you know it, I had Neon Tetras spawning- stuff like that!

And even then, I realized that I had to be flexible in my thinking. The "random" successful spawning of "not beginner" fishes that I would experience were not necessarily the result of my skill and planning- they were the result of embracing less traditional processes, and ceding some of that work to Nature. Allowing my ideas to be guided by Her.

Sounds sort of elegant, romantic- probably a bit naive.

However, it's actually a great strategy.

Set the stage, allow things to "breathe" just a bit. And you'll often reap the rewards.

Oh, and you have to make the effort to understand what's happening in your aquarium. It's important to not buy into the hype and B.S. that's been pushed around online for decades about natural, botanical-style blackwater aquariums, and the materials that we use to create them. Now, there is a lot of good information out there, too.

There have been some studies, which we've discussed over the years here, which indicated that materials such as catappa leaves do indeed provide some potential anti fungal/antimicrobial benefits because of the compounds they contain, but I would certainly not use this "disease prevention" thing as the sole justification for utilizing botanicals and creating blackwater systems. That is a whole lot of marketing bullshit, IMHO.

Rather, I'd make the argument that, when coupled with good overall husbandry, a well-managed blackwater aquarium can provide environment which is more consistent with that which many of the fishes we keep have evolved to live in over eons, and that this is a generally healthy way to keep them. Humic substances and other compounds released by botanicals are thought by scientists to be essential for the health of many fishes, and in blackwater aquariums, there are significant concentrations of these compounds present at all times.

Our blackwater/botanical-style aquariums cannot be called the "the best option" for many fishes- just a really good option- one worth investigating more!

Maybe it's time for us to once and for all accept that things are not aesthetically "perfect" in nature, in the sense of being neat and orderly/ratio-adherent from a "design" aspect. Understanding that in Nature, you have branches, leaves, rocks, and botanicals materials scattered about on the bottom of streams in a seemingly random, disorderly pattern.

Or are they? Could it be that current, weather events, and wind distribute materials the way they do for a reason? Could our fishes benefit from replicating this dynamic in our aquariums?

And, is there not incredible beauty in that apparent "randomness?"

Now, I realize that a glass box is NOT a flooded Amazonian forest, mangrove estuary, or Asian peat bog. I realize that we're constrained by size and water volume. We've touched on that hundreds of times here over the years. However, it can look and function like one to some degree, right?

The same processes which occur on a grander scale in Nature also occur on a "micro-scale" in our aquariums. And we can understand and embrace these processes- rather than resist or even "revile" them- as an essential part of the aquatic environment.

All of these things are amazing and helpful.

If we're patient, creative, and flexible about our aspirations. If were willing to accept the changes that Nature brings to our ideas- the possibilities for enjoyment, success- even breakthroughs- are too exciting to resist.

Stay creative. Stay inspired. Stay observant. Stay...flexible...

And Stay Wet.

The "Terrestrial Approach": A different sort of start?

If you think a bout it, the typical aquarium startup is to add some sand, add some wood, maybe plants, and...BOOM! Aquarium.

Okay, here is more to it than that; however, it's interesting to me that little consideration is played to the idea of starting an aquarium in a more functional way...Like, yeah, the basic essential tasks are pretty straightforward, yet the idea of creating a functional ecosystem from the ground up is almost a bit of an afterthought, IMHO. It seems to take a back seat to the "structural" aspects.

SO, I thought a lot about ways to start up a new botanical-style aquarium. And I think it for of dovetails nicely with my philosophies, and my experiences with my "Urban Igapo" setups. I think it's important to set up an aquarium-particularly a botanical-style aquarium- by taking a "terrestrial approach."

Huh?

Well, this kind of builds upon a lot of the things we've talked about here.

One underlying theme is that aquatic environments are profoundly influenced by- or even formed by- the terrestrial habitats which surround them. Sure, the flooded forest floors, subjected to seasonal inundation from overflowing rivers and streams are the "classic" example. However, there are other influences, some less directly obvious, yet every bit as important.

For example, as we've discussed repeatedly here, soils and geology in general are very influential on the surrounding aquatic habitats. We know that blackwater environments are created partially from the surrounding soils, rich in fulvic and humic acids, as well as the rock strata from which the source waters flow (like, I the Andes, for example).

Remember our little foray into soils and how they influence aquatic habitats?

Perhaps it's time for a refresher...😱

In general, blackwaters originate from sandy soils.

High concentrations of humic acids in the water are thought to occur in drainages with what scientists call "podzol" sandy soils from which minerals have been leached. That last part is interesting, and helps explain in part the absence of minerals in blackwater.

Blackwater rivers, like the Rio Negro, for example, originate in areas which are characterized by the presence of the aforementioned podzols.

Podzols are soils with whitish-grey color, bleached by organic acids. They typically occur in humid areas like the Rio Negro and in the northern upper Amazon Basin. And the Rio Negro and other blackwater rivers, which drain the pre-Cambrian "Guiana and Brazilian shields" of geology, can in part attribute the dark color of their waters to high concentrations of dissolved humic and fulvic acids!

Although they are the most infertile soils in Amazonia, much of the nutrients are extracted from the abundant plant growth that takes place in the very top soil layers, as virtually no plant roots are observed in the mineral soil itself.

One study concluded that the Rio Negro is a blackwater river in large part because the very low nutrient concentrations of the soils that drain into it have arisen as a result of "several cycles of weathering, erosion, and sedimentation." In other words, there's not a whole lot of minerals and nutrients left in the soils to dissolve into the water to any meaningful extent!

Okay, that's a pretty roundabout way of re-explaining that various soils contribute to the water chemistry of the aquatic habitats which cover them. So, what are the implications for us as aquarists?

For one thing, perhaps your next botanical-style aquarium needs to have more of a "terrestrial influence" from day one.

In other words, incorporate some soil or other materials into your substrate. Yeah, I know, it's the part where you trash me again for teasing about our "Nature Base" sedimented substrates, long overdue...they're coming! Yet, that's what I'm getting at here: Set up your aquarium with some other materials besides just clean while sand.

We'll help you with that, promise.

These interdependencies are really complicated- and really interesting!

And it just goes to show you that some of the things we could do in our aquariums (such as utilizing alternative substrate materials, botanicals, and perhaps even submersion-tolerant terrestrial plants) are strongly reminiscent of what happens in the wild.

We know this, because we see their impact on natural aquatic systems all the time, don't we? Every flooded forest, inundated Terre Firme grassland, every overflowing stream- provides a perfect example for us to study.

The land influences the water.

Each component of the terrestrial habitat has some unique impact on the aquatic habitat. Not really difficult to grasp, when you think about it in the context of stuff we know and love in other areas of life.

The "Urban Igapo" idea we've been pushing here for well over two years now is just one way to play with this stuff and study these unique interdependencies.

Sure, we typically don't maintain completely "open" systems, but I wonder just how much of the ecology of these fascinating habitats we can replicate in our tanks-and what potential benefits may be realized?

That's my continuing challenge to our community... We'll be talking a lot more about this in coming months.

This is the most superficial look at this idea, but the point is to look at the influences of the land and how they affect aquatic habitats, and try to replicate them and their processes.

It's easy to do...

Just look around.

Stay inspired. Stay creative. Stay thoughtful. Stay motivated...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Variety: The stuff of...confusion?

Okay, I must admit...When I first started Tannin Aquatics, it was my intent to offer the widest possible variety of botanical materials for everyone to have the most varied "palette" to work with. I was (and still am) very enamored with the huge variety of natural materials available to us to use to influence aquatic environments.

I had been playing with seed pods, twigs, and leaves for decades, and I figured that it would make sense to offer the stuff I'd used for such a long time to all of our customers.

When we launched in 2015, we offered a lot of different stuff..

And it's just gotten more and more complex...And the interesting thing is that, when I first started, it was mostly about...paranoia...Seriously! I wanted to make sure (how foolish and petty of me..) that no one would come into the space and have "more stuff" than Tannin..

I mean, what LAME rationale for a widely varied inventory, right? A sign of insecurity, more than anything, right? I mean, thinking that the key to thought leadership in my little hobby sector was having more seed pods than some other guy....STUPID!

It's still stupid.

It took me a few years to realize that it really went against my philosophy of offering the best items and inspiration- and developing products based on how we think we can move the hobby forward.

The new businesses which come into our market space do this all the time- they feel compelled to offer everything under the sun. It's like chasing a unicorn, IMHO. I mean, if the pandemic taught me one thing, it's that managing a vast global supply chain is quite challenging...The more different items you offer, the more difficult it is to keep them in inventory consistently. You're bound to have some of your key suppliers unable to ship, or influenced by other factors, like weather, regulations, etc.

It's challenging!

I know my international suppliers very well for years now, and it's challenging for ME. I can imagine how difficult it must be for newcomers!

So, yeah, it was actually a weird "disconnect" between how I function as a hobbyist and what I really needed to do as a business. As we move forward, I'm going to let them enjoy the headaches of juggling all of that stuff. We'll be editing our offerings to more accurately reflect our beliefs, practices, techniques, and philosophies. Tannin is moving in some really exciting, unique directions in 2021..

Stay tuned!

So, yeah, an enormous variety of stuff in one tank is simply of contrary to how I typically run my botanical-style aquariums...

If you study pics and videos of our tanks that we feature in our videos and social media posts, you'll notice that we almost always use just a few different types of botanicals per tank. Sometimes, just one or two. Why is this?

Several reasons, really.

The first reason is the most shallow, but it's true: It's about the visuals! There is something chaotic about seeing too many different types of materials in a confined space, at least to me. And quite honestly, you can achieve a pretty complex look with just a few different items.

I suppose it's a little funny, when we curate your "Enigma Pack", we try to offer more of a variety of stuff- partially, because it brings you more value, and also because it exposes you to a wider variety of materials. However, if you prefer a more limited selection of items in your pack, let us know!

Does that make sense? Need more convincing?

And then, there's our absolute favorite muse- Nature.

It looks like Nature often accumulates a seemingly large amount of mixed-up materials in relatively small spaces. However, if you examine some of these locales closely, you'll see that they are often comprised of large quantities of just a few different things: Mainly leaves, some seed pods, and a lot of twigs and other branch-like materials.

And it makes sense, right?

When streams flow through forests, or forest floors flood, the materials which fall are limited to the materials which are present in the terrestrial environment. Now, in the case of streams, rivers, and even inundated forest floors, you'll often see materials from other areas distributed by currents or torrents.

However, for the bulk of the habitats we observe for inspiration, the amount of materials visible is limited to those found in the immediate vicinity. And often, they come from just a few sources. So, if the goal is to accurately reflect a natural habitat, it might make more sense to really study it very closely. You'll be surprised by what you see!

Now, don't get me wrong. It would be easy for some to misconstrue that I think having a wide variety of materials in a botanical-style aquarium is a bad thing- setting you up for...what? Failure? Disaster?

Of course not.

See, it's really not a "bad thing. It's just an opinion. A preference.

Some people love the visuals of lots of different stuff. Some, like me, take delight in the endless variety which Nature offers. However, I just personally find that too much variety in one tank to be a bit overwhelming to my sense of aesthetics.

Again, you'd be surprised just how much complexity you can achieve with just a few elements. The "Tucano Tangle" pictured above, arguably one of our most popular creations, relied on three selections: Melastoma root over a base of "Spider Wood", and a layer of Live Oak Leaf litter. Three things.

Root tangles and fallen tree branches are among my most loved natural inspirations. The complexity created by a mere assemblage of branches, tree trunks, roots, and a little bit of leaves and sediments is incredible.

One of my favorite aquariums that I've ever done was inspired by this very habitat- complex, yet remarkably simple. Interpreting such a habitat is not only aesthetically enjoyable, it creates a functional environment for a huge variety of different fishes to feel right at home!

Nature works with whatever She is offered to create amazing underwater habitats, And we can, too.

Even if it's just using a few things.

And this "less is more" philosophy can be taken to it's ultimate in functional aesthetic simplicity...Consider my other fave personal tank- my Paracheridon simulans "no scape" leaf-litter-only setup from last year. Probably THE single most realistic, functional, and successful habitat simulation I've ever done, and it looked amazing (to me, anyways...)

And it consisted of NOTHING but leaves!

I could go on and on and on, musing about all sorts of lower-variety botanical-style tanks and sharing successful systems. And, I can show you some incredible, highly diverse botanical-style thanks that would blow your mind, too! In the end, it's about personal preference, taste, and philosophy. And hell, if your concept calls for 23 different seed pods in one tank, so be it!

DO what moves YOU.

Variety in our world doesn't mean "confusion" or "chaos", really. Rather, it's a gift from Nature- a call to utilize many different materials to create beautiful, functional, highly unique aquarium displays. We may be doing some editing- and you might see US play with just a few different materials in our tanks,; however, if our reverence of Nature has taught us anything, it's that there is endless variety and limitless possibilities to use her offerings in any number of amazing ways.

And Stay Wet.

To stay or not to stay?

One of the most commonly discussed and hotly debated topics among those of us into botanical-style aquarium lovers is the decision to remove leaves and botanicals from our aquariums as they break down, or to leave them in place.

It’s a pretty fundamental aspect of our aquarium practice, yet it sort of flies in the face of “conventional” aquarium keeping practices for many years. We have collectively embraced and almost “clinical sterility” in our aquariums, eschewing anything which seems to fly in the face of our aesthetic sensibilities and

The definition of “decompositon” is pretty concise:

de·com·po·si·tion- dēˌkämpəˈziSH(ə)n -the process by which organic substances are broken down into simpler organic matter.

We add leaves and botanicals to our aquariums, and over time, they start to soften, break up, and ultimately, decompose. This is a fundamental part of what makes our botanical-style aquariums work. Decomposition of leaves and botanicals not only imparts the substances contained within them (lignin, organic acids, and tannins, just to name a few) to the water- it serves to nourish bacteria, fungi, and other microorganisms and crustaceans, facilitating basic "food web" within the botanical-style aquarium- if we allow it to!

In an aquarium set up to take advantage of these materials and their function, the leaves and botanicals begin to soften and ultimately break down, they will foster microbial growth, biofilms, and fungal growths- all of which will provide supplemental foods for the resident fishes...just like what happens in Nature.

Again, this is a step that we need to take- an understanding that we need to have- that botanical-style aquariums are more than just some style of aquascaping. They are closed aquatic ecosystems, set up to optimize natural processes, while providing a wide variety of benefits for their inhabitants.

Facilitating these processes- allowing the materials to accumulate naturally and break down "in situ" is a key component of replicating and supporting these functional microhabitats in our aquariums. The typical aquarium hardscape- artistic and beautiful as it might be, generally replicates the most superficial aesthetic aspects of such habitats, and tends to overlook their function- and the reasons why such habitats form in the first place in Nature.

Of course, accepting this process in our aquariums means that we need to embrace an entire compliment of organisms and their “work” within our aquariums.

Decomposers, which include bacteria, fungi, and other microorganisms, are the other major group in the food web. They feed on the remains of other aquatic organisms and plants, and in doing so, break down or decay organic matter, returning it to an inorganic state.

Some of the decayed material is subsequently recycled as nutrients, like phosphorus (in the form of phosphate, PO4-3) and nitrogen (in the form of ammonium, NH4+) which are readily available for plant growth. Carbon is released largely as carbon dioxide that acts to lower the pH of the aquarium water.

We need to get over the "block" which has espoused a sanitized version of Nature. I hit on this theme again and again and again, because I feel like globally, our community is like 75% "there"- almost entirely "bought in" to the idea of really naturally-appearing and functioning aquarium systems.

Understanding that stuff like the aforementioned decomposition of materials, and the appearance of biofilms- comprise both a natural and functional part of the microcosms we create in our tanks.

This is true in both the wild habitats and the aquarium, of course.

The same processes and function which govern what happens to these materials in the wild occur in our aquariums. And, if we reject our initial instinct to "edit" what Nature does, the aquarium takes on a look and vibrancy that only She can create.

Embrace, don't edit.

Leave the stuff in there until it decomposes.

Stay open-minded. Stay thoughtful. Stay creative. Stay observant...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

And still, I worry..

The world of blackwater, botanical-style aquariums is really expanding. I mean, it's been a "thing" in the aquarium hobby for many decades; it's just that it's been rapidly emerging from the shadows, so to speak, at an accelerating pace over the past few years.

A very exciting thing.

So many new converts to this hobby specialty. More sharing of ideas, techniques, and experiences. There must be 6-8 forums on Facebook alone covering blackwater. It shouldn't be that difficult to get some solid information on this stuff.

And still, I worry.

Huh?

I worry, because I still see a lot of discussions and questions on how to do "hacks" or "shortcuts" to create a blackwater aquarium. I still see the emphasis placed on aesthetics over function and ecology. I see a lot of sharing of inspiring tanks- which is great- but little substantive information on how the tank was created, how it's managed, and what the water parameters are...Stuff which can truly help others decide if this speciality is for them.

As we've said repeatedly over the last 5 years or so, blackwater, botanical-style aquariums are more than just a "look." Theyre not an "aquascaping style." They're about an aquarium environment which provides optimum conditions for fishes which are accustomed to blackwater environments. They incorporate "functional aesthetics" over mere aesthetics.

Now, I'm not the undisputed authority on this stuff. News flash.

However, I'm not just a "bystander", either.

And, since a lot of questions and observations and ideas about this stuff seem to come my way- and Tannin's way- over time, I figure that I have at least something interesting to say now and then about blackwater, botanical-style aquarium keeping. Maybe I've become a sort of "clearing house" for this stuff.

Not sure.

Regardless, I think it's my obligation-as it is all of ours- to speak out and let our opinions be known when we see something that we can be helpful with. And right now, I think it's time once again for me to speak up about a little concern that I have about our little sector of the hobby.

I think we are seeing ga lot of people leaping into this stuff, enticed by the look, without a basic understanding of the chemistry, ecology, and function of the wild habitats that these aquariums purport to mimic. I see questions so basic that it makes me wonder if someone simply saw a pic of a cool blackwater tank on The 'Gram, filled an aquarium, brewed up some Roobois tea, threw in some Cardinals, and figured that they had a "blackwater aquarium."

Okay, I know, I sound bitter (like the tea, perhaps?).

However, this is a potential problem in the making. I've seen this before. Just like we saw in the reef aquarium world years ago, you can't simply jump in, enticed by a "look", without doing the most fundamental research on this stuff and expect everything to be smooth sailing. The results are almost always underwhelming at best- and disastrous at worst.

As we know by now, success with blackwater, botanical-style aquariums isn't a sure thing. You can do most everything "correctly" and still make a seemingly "innocent" mistake and kill your whole aquarium. That's why we need to go deeper and share the good, the bad, and the ugly of this stuff, as we've done here for years. We need to share our failures as much as we do our successes. We need to share our out-of-control biofilm blooms as much as we do our crystal-clear, sexy blackwater tanks.

We have to really understand the "why" of the unusual aesthetics of blackwater, botanical-style aquariums, and what the benefits are.

We need to go deeper. Share more. Discuss more "nuts and bolts" stuff.

This is how we all learn.

We need to stop regurgitating stuff- regardless of source (yeah, even if it's us) without "vetting" the information ourselves. It's better to say, "I don't know" than "I've heard that..." We need to do more of the decidedly non-sexy research and getting a grasp of the fundamentals of the hobby, particularly as it pertains to our specialty.

We need to stop looking for shortcuts and cheap ways to do everything in this hobby. I'm not saying just spend tons of money and do everything the hard way. I AM saying that we occasionally have to do things in a more roundabout, more costly way, simply because these are sometimes the best ways to do it. We need to always place the welfare of our animals ahead of our desire to get what we want as quickly and inexpensively as possible.

We must always, ALWAYS preach patience. We need to continue to demonstrate and discuss that these types of aquariums are the result of embracing patience, process, diligence, and self-education.

Yeah these are really important things that we need to work on.

We're seeing some amazing blackwater, botanical-style aquariums. Some really cool ideas being acted upon by all sorts of hobbyists. Some spectacular successes with spawning fishes that were previously considered "difficult." We're seeing a sort of "enlightenment" in this speciality.

Things are progressing nicely.

And still, I worry.

I mean, someone has to, right?

Might as well be me.

Yeah. I think we can do even better. Let's do that.

And then I can stop worrying. I mean, I really shouldn't, right?

Stay diligent. Stay educated. Stay informed. Stay observant. Stay diligent. Stay patient...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

From "idea mode" to the long term..

I'm in a very interesting phase in my personal part of the hobby. Autumn is right here...the official start (IMHO, anyways) of "aquarium season!"- time to start a bunch of new tanks!

It's also time to reflect on the way I ideate and manage aquariums for the long run.Oh, did you catch that? "Long term." When thinking of the ideas for our new tanks, I think we should focus on setting them up to run effectively for a very long time. Not just to "...get the pic for the 'Gram..."

Fuck that shit.

I've recently moved into my new home, and I'm in that "Evaluate where you are and figure out how many tanks you want to set up" mode. (Seriously, there IS a mode for that). I've been staring at the room where my home office and aquarium will be, thinking about all of those important (to a fish geek) factors, like, where the electrical outlets are, how much room here is for various sized aquariums, where on the walls they'll be located, etc.

Of course, the most important (and fun) part is trying to figure out what "themes" I'm going to be exploring with my new tanks. I think that some of the ideas of been playing with are starting to coalesce a bit in my head. I mean, there will definitely be an igapo and a varzea setup- no questions there. Smaller (like 3-5 U.S. gallon) tanks. And likely, one or two really "out there" ideas (in terms of exploring new ecological niches), and then of course, a brackish tank and a moderately-sized (50 gallon or so) "classic" blackwater aquarium.

For me, it's always important to play with the materials that we offer our customers- before we release them for sale, of course!

Now, one of the things I've done a lot in recent years is to keep the substrate layers from my existing tanks and "build on them."

In other words, I'm taking advantage of the well-established substrate layers, complete with their sediments, decomposing leaves and bits of botanicals, and simply building upon them with some additional substrate and leaves. I've done this many times over the years- it's hardly a "game-changing" practice, but it's something not everyone recommends or does.

I believe that preserving and building upon an existing substrate layer provides not only some biological stability (ie; the nitrogen cycle), but it has the added benefit of maintaining some of the ecological diversity and richness created by the beneficial fuana and the materials present within the substrate. I know many 'hobby old timers" might question the safety- or the merits-of this practice, mentioning things like "disturbing" the bacterial activity" or "releasing toxic gasses", etc. I simply have never experienced any issues of this nature from this practice. Well maintained systems generally are robust and capable of evolving from such disturbances.

I see way more benefits to this practice than I do any potential issues.

Since I tend to manage the water quality of my aquariums well, I have never had any issues, such as ammonia or nitrite spikes, by doing this- in fresh or saltwater systems. It's a way of maintaining stability- even in an arguably disruptive and destabilizing time!

This idea of "perpetual substrate"- keeping the same substrate layer "going" in successive aquarium iterations- is just one of those things I believe that we can do to replicate Nature in an additional way. Huh? Well, think about it for just a second. In Nature, the substrate layer in rivers, streams, and yeah, flooded forests and pools tends to not completely wash away during wet/dry or seasonal cycles.

Oh sure, some of the material comprising the substrate layer may get carried away by currents or other weather dynamics, but for the most part, a good percentage of the material- and the life forms within it- remains when the water recedes.

So, by preserving the substrate from pre-existing aquairums, and "refreshing" it a bit with some new materials (ie; sand, sediment, gravel, leaves, and botanicals), you're essentially mimicking some aspects of the way Nature functions in these wild habitats.

And, from an aquarium management perspective, consider the substrate layer a living organism (or "collective" of living organisms, as it were), and you're sure to look at things a bit differently next time you re-do a tank!

Of course, perpetuating the substrate is almost like persuing "eternal youth"- it's not entirely possible to achieve, but you can easily embrace the idea of renewal and continuity within your aquarium.

Things change in Nature, but other things are also preserved. Nothing goes to waste.

And yet, as alluded to above, the one concept about botanical-style aquariums that I can't seem to bring up enough is the idea that many of the habitats we like to represent in our tanks- and the materials which we utilize to 'scape them, are ephemeral. Typically, they are not "permanent" features, in the same way a rock or a piece of wood is-instead, breaking down and decomposing following long-term submersion.

It's about the long term, for sure. Well, long term, in terms of keeping the "lifetime" of an aquarium.

How long do you keep your botanical-style aquariums up and running?

A few months? A year? Several years?

As self-appointed "thought leaders" of the botanical-style natural aquarium movement, we spend an enormous amount of time talking about how to select botanicals, prepare them, and utilize them in aquariums. We talk about what happens when you place these terrestrial materials in water, and how botanical-style aquariums "evolve" over time...

All well and good...

However, we've probably talked a lot less about the idea of keeping these aquariums over the very long term.

And, I'd define "very long-term" as a year or more.

I mean, this makes a lot of sense, because botanical-style tanks, in my opinion, don't even really hit their "stride" for at least 3-6 months. Yet, in the content-driven, Instagram-fueled, postmodern aquarium world, I know that we tend to show new looks fairly often, to give you lots of ideas and inspiration to embark on your own journeys.

And I suppose, that's a very cool thing. Yet, it's likely a "double-edged sword."

Like so many things in the social media representation of today's aquarium world likely gives the (incorrect) impression that these tanks are sort of "pop-ups", set up for a photography session and broken down quickly.

We at Tannin are, regrettably, likely contributors to some of this misconception!

I think we, as those "thought leaders", need to do more to share the process of establishing, evolving, and maintaining a botanical-style aquarium over the long term. To that end, we're going to do a lot more documentation of the entire process in months to come- documenting the journey from "new" to "mature"-sharing the ups, downs, and processes along the way.

Now seems like a a perfect time for me to really act on this!

The surest path to success with botanical-style, natural aquariums, as we've stressed repeatedly, is to move slowly and incrementally.

Sure, once you gain experience, you'll know how far you can "push it", but, quite frankly- Nature doesn't really care about your "experience"- if the conditions aren't right and the bacteria in your system cannot accommodate a rapid, significant increase in bioload, she'll kick your ass like a personal trainer!

It's important to take a really long-term view here.

Do that right from "idea mode", and I think you'll be good.

Stay thoughtful. Stay curious. Stay bold. Stay resourceful...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

The real "live stream..."

Ever thought of this: What is your aquarium "idea" based upon/inspired by? A big body of water? Some sort of meandering, flowing habitat, or just a more "static" body of water?

When you think about it, we tend to "model" our aquariums off of only a few types of aquatic features found in Nature...I'm willing to bet that they're typically lakes, rivers, and streams.

We as a group should give a bit more mental energy to thinking about these habitats...there's more there than meets the eye!

It's only been recently that I really gave more than a passing thought to what goes on "down there" in Nature, especially in streams. It's a lot more interesting, when you examine the subject more closely- especially from the perspective of how these structures came to be, and what implications they have for fish populations...cool stuff like that!

Now, sure, you know of my obsession with varying substrate compositions and enhancement of the substrate...You've likely seen my recent work with with different materials, like leaves, botanicals, clays, and sediments that I've shared with you here and elsewhere. It's an idea that I just can't get away from!

The physical composition of the substrate materials is but one fascinating aspect of these diverse aquatic systems. There is a lot more going on "down there" than meets the eye. When you take into account just how these habitats came into existence, and what processes create and sustain them, the dynamic gets really interesting!

Stream and river bottom composition is affected by things like regional weather, current, geology, the surrounding terrestrial ecosystem, and a host of other factors- all of which could make planning your next aquarium even more interesting if you take them into consideration!

And there is the whole dynamic of water movement. Like, what role does the flow of water determine the ecology of a given stream, and how it will "recruit" life forms to reside in it?

Well, for one thing, it's helpful to go back the substrate again, and to consider it's relationship to water movement. It's important to note that the volume of water entering the stream, and the depth of the channels it carves out, helps in part determine the amount and size of sediment particles that can be carried along, and thus comprise the substrate.

And of course, the composition of bottom materials and the depth of the channel are always changing in response to the flow in a given stream, affecting the composition and ecology in many ways.

For example, some leaf litter beds form in what stream ecologists call "meanders", which are stream structures that form when moving water in a stream erodes the outer banks and widens its "valley", and the inner part of the river has less energy and deposits silt- or in our instance, leaves.

Materials which fall from the surrounding trees and other vegetation accumulate in these "meanders", creating interesting ecological features which are compelling themes for your next biotope aquarium!

There is a whole, fascinating science to river and stream structure, and with so many implications for understanding how these structures and mechanisms affect fish population, occurrence, behavior, and ecology, it's well worth studying for aquarium interpretation! Did you get that part where I mentioned that the lower-energy parts of the water courses tend to accumulate leaves and sediments and stuff?

Likely you did!

I mean, that's the really fascinating part, to me.

Permanent streams will often have different volume and material composition (usually finely-packed sands and gravels, with lots of smooth stones) than more intermittent streams, which are the result of inundation caused by rain, etc.

So-called "ephemeral" streams, typically occur only immediately after rain events (which means they usually don't have fish in them unless they are washed into them from more permanent watercourses). The latter two stream types are typically more affected by leaves, botanical debris, branches, and other materials.

In the Amazon region (you knew I was sort of headed back that way, right?), it sort of works both ways, with the streams influencing the surrounding land...and then the land "giving" some of the materials back to the streams...the extensive lowland areas bordering the river and its tributaries, known as varzeas (“floodplains”), are subject to annual flooding, which helps foster enrichment of the aquatic environment.

You might even say that rivers and streams act like Nature's "sediment sorting machines", as they move debris, geologic materials, and botanicals along their courses. And along the way, varying ecological communities are assembled, with all sorts of different fishes being attracted to different niches.

Although many streams derive their food base from leaves and organic matter, there is a lot of other material present that contributes to its structure. Think along those lines when scheming your next aquarium!

It is known by science that the leaf litter and the community of aquatic animals that it hosts is, according to one study, "... of great importance in assimilating energy from forest primary production into the blackwater aquatic system."

It also functions as a means to preserve the nutrients that would be lost to the forests which would inevitably occur if all the material which fell into the streams was simply washed downstream. The fishes, crustaceans, and insects that live in the leaf litter and feed on the fungi, detritus, and decomposing leaves themselves are very important to the overall habitat.

As we've talked about before briefly, another interesting thing about leaf litter beds is that they actually have "structure" and even longevity. In several studies I read on the subject, the accumulations of leaves in various streams are documented to have existed in the same locations for years- to the point where scientists actually have studied the same ones for extended periods of time.

Of course, I think we need to look beyond just the cool looks of the natural habitats from where our fishes hail, and focus on the attributes which comprise their function. We need to understand why fishes are attracted to certain habitats, and apply these lessons into our aquariums.

The streams of the world are just a starting point for us to explore in our quest to create more realistic, functionally aesthetic aquairums that will provide enjoyment, education, and inspiration for others.

Who's down with the idea of focusing on this habitat?

Stay inspired. Stay excited. Stay creative. Stay resourceful...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Love, life...leaf litter...

Okay, the title of this piece is kind of ridiculous, but the point of it is really simple: We love the idea of using leaf liter in aquariums. Pretty much everything that we work with in the botanical-style aquarium world is based on leaf litter!

So, like, what's the big deal?

What are the implications for leaf litter in our aquariums? They're as functional as they are "aesthetic" in our world. Decomposing leaves recruit biofilms, serve as "fuel" for the growth of fungi and microorganisms...which, in turn, provide supplemental food for our fishes.

And of course, we have to consider the impact of these materials on water quality

Dead, dried leaves such as those we favor don’t have nearly the impact on water quality, in terms of nitrate, as fresh leaves would. I’ve routinely seen undetectable nitrate levels in aquariums loaded with botanicals. This is largely because dead, dried leaves have depleted the vast majority of stored sugars and other compounds which lead to the production of nitrogenous substances in the confines of the aquarium.

To understand this more fully, let’s look at what happens when a leaf dies and falls into the water in the first place.

At some point, the leaves of deciduous trees (trees which shed leaves annually) stop photosynthesizing in their structures, and other metabolic processes within the leaves themselves begin to shut down, which triggers a process in which the leaves essentially “pass off” valuable nitrogen and other compounds to storage tissues throughout the tree for utilization. Ultimately, the dying leaves “seal” themselves off from the tree with a layer of spongy tissue at the base of the stalk, and the dry skeleton falls off the tree.

As we know by now, when these leaves fall into the water, or are immersed following the seasonal rains, they form a valuable substrate for fungi to break down the remaining intact leaf structures. And the fungi population helps contribute to the bacterial population which creates the now-famous biofilms, which consist of sugars, vitamins, and various proteins which many fishes in both their juvenile and adult phases utilize for supplemental nutrition.

And of course, as the fishes eliminate their waste in metabolic products, this contributes further to the aquatic food chain. And yeah, it all starts with a dried up leaf!

Hence, leaving leaves in to fully decay in your aquarium likely reaches a point when the detritus is essentially inert, consisting of the skeletonize sections of leaf tissue which can decay no further. Dead leaves contain largely inert forms of polysaccharides, and are reach in structures like lignin and cellulose, all of which are utilized by various microorganisms and fungi within the "food chain."

Utilizing leaf litter in our aquariums opens up all sorts of possibilities for interesting experiments. You can go with just a few leaves- or really go crazy with a deep bed of leaf litter in your tank!

I periodically discuss the idea of creating a really deep litter bed in an aquarium, to more accurately replicate some of the litter beds found in South America, Asia, Africa, and elsewhere. By "deep", I'm talking 6"- 12" (15.24cm-30.48cm). Yes, there are deeper litter beds in these areas (several feet in depth); however, for practical aquarium display purposes, I think the rational "upper limit" is likely more like the 12" (30.48cm) range.

Or, is it?

Now, there is certainly a difference between the "theoretical" and the "practical", but I can't help but think that there is something beneficial about such a deep leaf litter bed...perhaps stuff we haven't imagined, because we're too busy talking about all of the possible "downsides" of the idea.

And it's intriguing for me to contemplate how to make such an idea work. I mean, it isn't really all that much different than what many of us do now...the main difference being that we'd use MORE of the same materials.

In researching the idea of executing such a deep litter bed, I thought about what would be the main considerations when attempting to create one in an aquarium. In no particular order, here are just a few of the main concerns I have:

-The ratio of "leaves to water" in a given aquarium could be quite significant. I mean, what size aquarium do I go with? I'm also curious about the impact on the water quality and oxygen levels with that much decomposing materials "in play."

On the other hand, starting from scratch with a new system and cycling it with "bacteria in a bottle" products and/or "seeded" substrate materials would no doubt at least "kick start" the biological filtration before fishes ever enter the equation.

And, although the mass of leaves would be considered "bioload", I can't help but wonder if it would also function as a "nutrient processing" facility, much in the same way a deep sand bed does in a reef aquarium? I mean, with that much "media" surface area, could this be the case? Like, denitrification by "deep leaf litter bed!"

Maybe?

And what about the impact on pH- something aquarists debate constantly?

There have been researchers of natural leaf-litter banks who contemplate that processes which produce the low pH levels associated with these beds (sometimes down to 2.8-3.5pH!) are not caused entirely by humic acids which are frequently assumed to be the major contributor -and are not strong enough acids to produce such a low pH.

A possibility suggested by researchers is that fermentation deep within the litter banks is releasing strong organic acids such as acetic acid...Could this happen in the confines of a closed aquarium?

I'm honestly not sure, but I suppose anything is possible, right? On the other hand, as we've talked about repeatedly, even in water with little to no carbonate hardness, pH impact is likely not strong enough to drop pH into those crazy low ranges. And, with substrates present in most tanks, there is probably some degree of buffering which occurs as well.

So, what about the "biology part?"

Well, let's contemplate, for a few minutes, the role leaf litter plays in natural aquatic ecosystems.

Suffice it to say, the leaf litter bed is a surprisingly dynamic, and one might even say "rich" little benthic biotope, contained within the otherwise "impoverished" waters. And, as we've discussed before on these pages, it should come as no surprise that a large and surprisingly diverse assemblage of fishes make their homes within and closely adjacent to, these litter beds. These are little "food oasis" in areas otherwise relatively devoid of food.

The fishes are not there just to look at the pretty leaves!

Many blackwater rivers are often called "impoverished" by scientists, in terms of plankton production. They show little seasonal fluctuations in algal and bacterial populations. This is a fact borne out by many years of study by science. However, "impoverished" doesn't mean "devoid" of life. And in many cases, these populations of food organisms do vary from time to time- and the fish along with them.

As we’ve discussed repeatedly over the past couple of years, there are so many benefits to painting leaf litter in the aquarium in some capacity. Wether it’s for water conditioning, supplemental food, a home for speciality fishes, or simply for a cool-looking display. Simply overcoming our ingrained aesthetic preferences and accepting the decomposing leaves as a natural, transitory, and altogether unique habitat to cherish in the aquarium opens up so many incredible possibilities!

Stay thoughtful. Stay creative. Stay open-mined. Stay unique. Stay curious...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Back to the varzea

As you are no doubt aware, we're obsessed with obscure (well, to the hobby, anyways...) aquatic habitats. And we've spent a lot of time observing, researching and studying these habitats and how to replicate them- functionally and aesthetically- in our tanks.

Among our absolute favorites are the flooded forests of South America- the igapo and the varzea. These unique habitats are fascinating, dynamic, and highly diverse ecosystems, which exist in both terrestrial and aquatic phases- both of which we can replicate in our own aquariums.

We've spent a ton of time talking about them- mostly about the igapo. However, the varzea habitats are equally dynamic and fascinating- well worthy of recreating them in our tanks. So, let's focus on the varzea today.

Varzea, the “whitewater”-inundated forest of South America, is very similar in structure to the terra firme forests (composed of layers of alluvial soil that were deposited as much as 2.5 million years ago). Such alluvial soils are rich in dead organic matter, which quickly decays and is recycled. When the nearby "whitewater" rivers overflow, these areas become aquatic habitats for weeks or months at a time.

The trees of the varzea tend to be significantly buttressed (which is likely an adaptation for the tree to remain anchored in the moist clay-rich soil), and typically have seeds with special water flotation mechanisms that enable them to be widely dispersed when the rivers of this region overflow seasonally- a valuable adaptation to such extreme environmental fluctuations.

And of course- in both igapo and varzea, there is a significant diversity of fishes!

In a comparative study of Amazonian fish diversity and density conducted by Henderson and Crampton in 1994, in nutrient poor blackwater igapó and richer whitewater várzea habitats in Brazil, the whitewater sampling sites were characterized by high turbidity and conductivity, and a pH of 6.6-6.9. By comparison, the blackwater sites had low turbidity, a very low conductivity, and a pH of 5.3-6.0.

The flooding often lasts for weeks and often, months- and the trees possess special biochemical adaptations to be able to survive the lack of oxygen in the substrate where their roots penetrate.

Of course, some trees do topple in torrential currents, or their branches fall into the water, are swept downstream, and accumulate in pockets, creating useful underwater habitats for fishes.

The formerly terrestrial environment is now transformed into an earthy, twisted, incredibly rich aquatic habitat, which fishes have evolved over eons to live in and utilize for food, protection, and spawning areas.

All of the botanical material-shrubs, grass, seeds, etc. become part of this aquatic milieu, too! Many of the species found in varzea have evolved survival strategies to endure this inundation period.

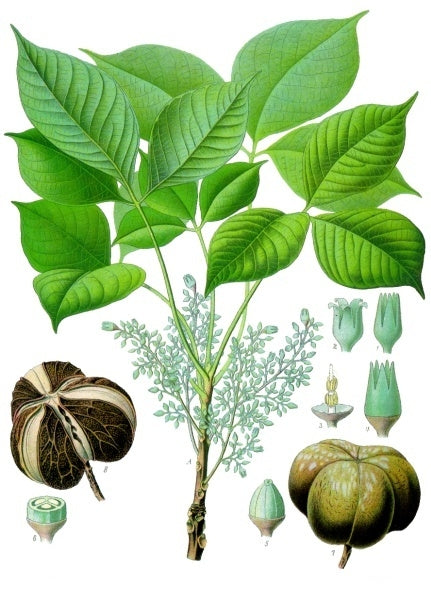

Trees such as the Rubber Tree (Hevea brazilensis) is a perfect example of a species which is clearly adapted to the varzea habitat, possessing seeds which can float for up to two months, and which form a significant part of the diet of certain larger fish of the region.

The seeds, along with fruit for the trees, after being consumed by fishes, are passed along throughout the forest. In fact, it is postulated by scientists that many of these seeds are required to pass through the gut of a fish before they will germinate!

As in the igapo, there is regular input of nutrient-rich sediment into the varzea, which is beneficial to the many low-lying shrubs found on the forest floors. This “understory layer”, as ecologists call it, is particularly lush, and quite rich in species of such plants as Gingers (Zingiberaceae) and Heliconias (Scitaminae). Hmm…something to think about when populating your varzea in its “dry” phase, huh?

Another interesting thing about Amazonian streams and flooded forest areas in general is that there is no significant "in situ" (in place) primary production, and that the fish populations that reside in them depend on what is known as "allochthonous input" (material that is imported into an ecosystem from outside of it) from materials like seed pods, fruits, blossoms, leaves, and dead wood from the surrounding forest.

So, how would you replicate this dynamic habitat in the aquarium?

Well, this is worthy of an entire podcast/blog post/video (and we are working on all of them as I write this!), but let's touch on the most basic of the details here- just to get you started...

For a várzea-themed aquarium, we'd say to start with a quality substrate, which represents the rich soils common to these forests. Like Nature Base "Varzea" by Tannin Aquatics! Yes, the long, LONG delayed "Nature Base" substrates will be debuting very soon (I know, we've said it before a few hundred times- we're really trying to get production smoothed-out and optimized prior to releasing them).

Just an aside: As we've learned, going "next level" and doing things other than just "slinging seed pods" is not so easy. Sourcing raw materials, formulation, testing, re-testing, and packaging are way more complicated! And we're developing several diverse, exotic new products at once...So we've been pretty busy around here! Thanks for your patience- they'll be well worth the wait, we promise!

Okay, commercial plug finished...

You should omit some of the more heavily "tint-producing" botanicals, and go with stuff like the more "durable" seed pods, like Mokha pods, Monkey Pots, etc. These not only impart less tannins into the water than leaves and such, many of them, such as Dysoxylum pods and the like, represent the fruits and such that accumulate in these waters. Your fishes will forage on and among them as they would with such materials in Nature.

A good chemical filtration media will counteract any tint imparted into the water by these materials, as well as the nutrients released by them. I mean, don't be fooled-you're gonna get some "tint" in the water, but not as much as if you're using lots of leaves and stuff like Catappa bark, etc.

It's about experimentation; studying, observing, and replicating a natural process in the aquarium...to the best of our capabilities. "Artistic liberties" are not only possible- they're welcome! So many iterations, interpretations, and experiments are possible here.

I'd use some nice pieces of wood to represent the buttressed roots of the trees found in these habitats.And of course, you can "plant" some terrestrial grasses and even some aquatic plants, creating the look and function in a more realistic manner.

Of course, you could also use riparian-type plants, like Sedges and such, which can tolerate- or even require immersion and very moist soils for long-term health and growth. Some species of these plants are indeed found in such temporal environments in Nature, so it goes without saying that you should experiment with them in the aquarium, too!

A lot to do here.

We cluster the idea of replicating these varzea habitats into our "umbrella" concept of the "Urban Igapo"- a fun way to play with these niche ecosystems in our aquariums...

The ongoing experimentation, the mental shifts that we've asked you to make, the "norms" of botanical-style aquarium "practice" that we've pushed here for a few years- all will come together to make the "Urban Igapo"experiment unique and enjoyable to a wide variety of hobbyists!

I really hope that today's brief review of the unique varzea habitat has given you a few ideas to help get started. Remember, the diversity of aquatic environments is legion, and there is virtually no limit to what you- the creative hobbyist- can achieve with some time, effort, and imagination!

Stay creative. Stay resourceful. Stay excited. Stay studious...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics