- Continue Shopping

- Your Cart is Empty

Learning curve.

One of the most interesting things about aquariums is that each one is different-just like its creator. Every aquarium has its own vibe, "operational cadence", characteristics...a "personality" of sorts, if you will. Have you ever noticed that it seems to take a few weeks to really "learn" about a new tank?

I've been setting up a few new tanks lately, so it's fun to go through this process and sort of hit those "mental checkmarks" on the journey.

You go through those various stages- Conceptual planning, equipment selection, the build-out process, adding the hardscape, water, and ultimately, fishes. You think by then, you'd really know your aquarium. I mean, you do...to a certain extent.

Even after an aquarium has water in it for several weeks or so, it takes a while to get a good "feel" for the tank. Does that make sense to you? A new tank is like a new relationship. Ever think about it in those terms?

It makes a lot of sense.

Yeah- you go through that period of initial excitement, anticipation, trying to not make mistakes; sometimes, there is a little awkwardness or nervousness associated with it until, ultimately, you realize that it's an enjoyable thing and you just do what comes naturally, making the best decisions possible to keep things happy and healthy. Then, you are very comfortable, while never taking it for granted or becoming complacent.

Good analogy, right? Maybe?

With a new aquarium, the first few weeks are really all about a "shakedown" of critical systems- making sure, first of all, that the damn thing holds water without leaking all over your hardwood floor! Then, the little things like the sounds the tank makes will become evident. Learning the water level that the tank seems to run at, figuring out the best access points for maintenance- "ergonomic" stuff like that. Things you like, dislike, and want to tweak. Early on, you get a "feel" for the tank, much as a driver gets a feel for a new car and all of its quirks.

And of course, there are the inevitable things that occur along the way in this process to throw you for a loop or two: The water won't clear, the system pump is a bit noisy, you can't seem to get the heater to the exact temperature setting you want, lighting timers are awry, that piece of wood won't stay in place where you like it- the usual shit that, although can be annoying, is all part of the game when you're setting up a new aquarium!

You also understand that your tank looks "stark" and "sterile"- maybe still a bit cloudy in this early phase, and you tell yourself that it's just getting underway...

Then comes the "tweaking" phase: "Edits", as I like to call them. You know, that rock needs to be tilted to the left ever-so-slightly, the wood needs adjustment...Maybe, a few less rocks and seed pods..yeah, more "negative" space. Or more leaves...Stuff which sets the stage for the evolution of the aquarium.

Stuff like that. Part of the "process", if you will.

And then, after all of the anticipation, planning, and execution, there is that day when you tell yourself, "Yeah, this thing is really starting to come together!"

Usually, for me, this is around the second water exchange. By that time, you'll have learned a lot of the quirks and eccentricities of your new aquarium. You'll have seen the way it rebounds from maintenance procedures, and how it functions in daily operation. I always get a lump in my throat the first time I shut off the main system pump for maintenance. "Will it start right back up? Did I miscalculate the 'drain-down' capacity of the sump? Will this pump lose siphon?"

And so what the fuck if it DOES? You simply...fix the problem. That's what fish geeks do. Chill.

Namaste.

Yet, I know some of these things DO bother me.

That's my personal worry with a new tank, crazy though it might be. The reality, is that in decades of aquarium-keeping, I've NEVER had a pump not start right back up, or overflowed a sump after shutting down the pump...but I still watch, and worry...and don't feel good until that fateful moment after the first water change when I fire up the pump again, to the reassuring whir of the motor and the lovely gurgle of water once again circulating through my tank.

Okay, perhaps I'm a bit weird, but I'm being totally honest here- and I'm not entirely convinced that I'm the only one who has some of these hangups when dealing with a new tank! I've seen a lot of crazy hobbyists who go into a near depression when something goes wrong with their tanks, so this sort of behavior is really not that unusual, right?

In a botanical-style aquarium, you need to think more holistically. You need to realize that these extremely early days are the beginning of an evolution- the start of a living microcosm, which will embrace a variety of natural processes. Bacteria and other microorganisms, nurtured by the abundant botanical materials, will grow and multiply. As leaves begin to soften, organisms such as fungi colonize their surfaces. Lignins, tannin, humic substances, and other organic compounds will begin to leach into the water.

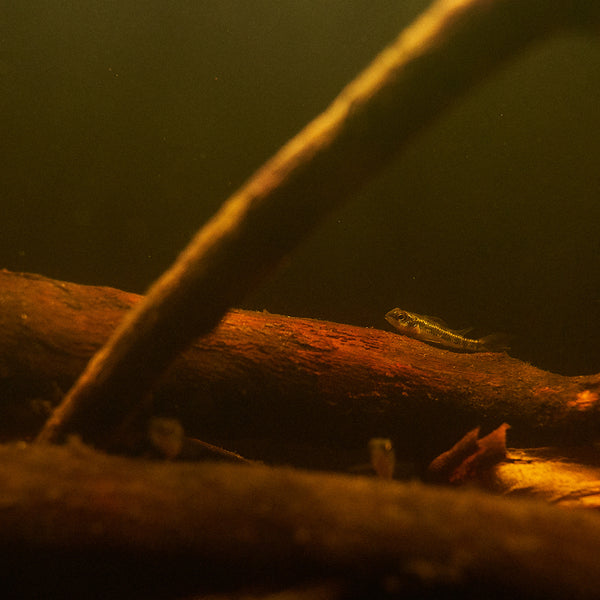

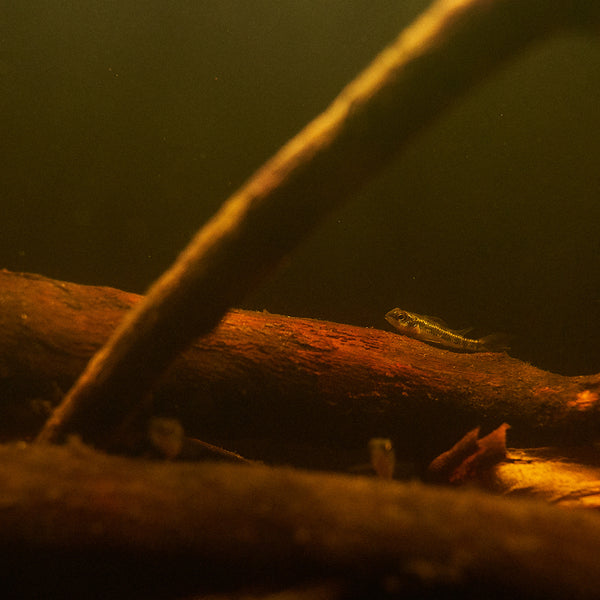

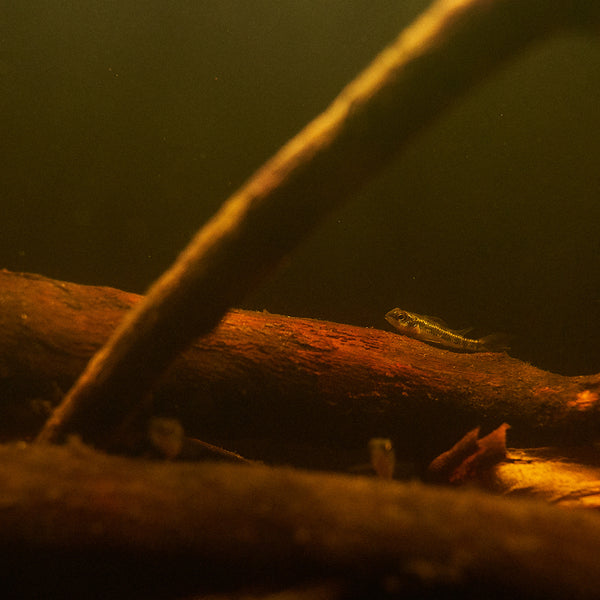

And then, seemingly out of the blue, you look at your tank one day and you know things are even better than they were last week; somehow, much different: The fish are beautiful and relaxed, the hardscape materials don't look so sterile and crisp. Plants, if present, are no longer "shocked"- they're growing. Biofilms and fungal growths are present, but not overwhelming. The water might have a slight turbidity to it- a definite tint, and there is a characteristic "patina" to all of the materials in the aquarium.

You're seeing a more "broken-in" system that doesn't seem so "clean", has that wonderful pleasant, earthy smell, and you realize that your system is healthy, biologically stable, and functioning as Nature would intend it to. If you don't intervene, or interfere- your system will continue to evolve on a beautiful, natural path.

It's that moment- and the many similar moments that will come later, which makes you remember exactly why you got into the aquarium hobby in the first place: That awesome sense of wonder, awe, excitement, frustration, exasperation, realization, and ultimately, triumph, which are all part of the journey- the personal, deeply emotional journey- towards a successful aquarium- that only a real aquarist understands.

Those are the moments that make the hobby so engrossing and so enjoyable. Those are the moments which make all of the other stuff we do so worthwhile. As you're going through the process of setting up a new tank, be sure to stop and savor each and every moment of the magic of aquarium keeping.

The familiarization itself is wonderful. SO is the learning curve.

Remind yourself at every stage that this is an incredible process..Savor each and every step on what is really as much of a journey as it is anything else. Create, observe, learn, and enjoy.

Stay committed. Stay excited. Stay engrossed...

And stay wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

LISTEN TO THIS EPISODE ON "THE TINT" PODCAST!

A brackish water trip...Deviation, or a journey into some familiar territory?

I had a rather interesting discussion the other day with Tannin's Creative Director and fellow hardcore aquarist, Johnny Ciotti, about a range of topics related to the establishment and management of botanical-style aquariums. One of the things we discussed was the idea of botanicals breaking down in the substrate and serving as a sort of "mulch" which supports biological activities, including microbial growth and plant growth.

I personally have experienced the benefits of allowing materials to accumulate in the substrate. My recent brackish, botanical-style aquarium has borne this out in spades!

One of the first decisions I made with this aquarium was to NOT siphon out the "organic debris/detritus" (total "catch-all" phrase, huh?) that accumulate during the normal course of existence of any aquarium. My rationale was that, the bulk of this material was fish waste and broken down leaves and botanicals, as opposed to uneaten food and such.

My whole point of the brackish water Mangrove aquarium "exercise " was to create a simulation of the organic-heavy, exceedingly rich substrates in which they are found, while still creating a manageable closed system that didn't turn into a cesspool!

I kind of figured that I don't overfeed. I don't over-stock, and I perform regular water exchanges on a weekly basis. I employ practices which assure as much environmental consistency as possible. And yeah, the physical environment has a very slight amount of fine organic debris/detritus on the substate. I've purposely siphoned the stuff out before, and by crude estimation, I'd say that well over 80% of what there actually is there, accumulating on the substrate, is the aforementioned botanicals and leaves In a decomposed state.

A sort of "mulch", if you will. I do see Nerites snails and some fo the fishes foraging in this material from time to time... but it's not all that noticeable unless you look really carefully.

I think these replicate, to some extent, the types of rich substrates in which mangroves grow and thrive. If you recall from my previous ramblings about this tank, we decided to utilize a variety of fairly rich substrate materials, including some commercial "marine biodsediment" additives, aquatic plant soil, sand, and a fracted clay gravel for the "top-dressing.

The reason for this section of "rich" substrate materials was twofold:

First, I wanted to create a functional mud-like substrate that would facilitate both denitrification and the ability to provide a habitat for minute life forms. I felt that this would also be a more natural setting for a brackish water aquarium. My original intent was to plant some Cryptocoryne ciliata, a species well-known for its ability to adapt to a low salinity brackish-water environment. This plan was ultimately abandoned when I decided to increase the specific gravity of the aquarium to 1.010, considerably higher than the documented SG at which this plant is known to survive (typically 1.002-1.005).

The second reason for employing such a rich substrate in a "non-planted" aquarium such as this was to set up the system for the point when the mangrove propagules, which I anchored to the upper part of a dead mangrove root/branch "structure", would put down prop roots and ultimately touch down and penetrate the substrate layer. I knew this process would take many months, of course, given the depth of the tank.

I also added some dried Malaysian Yellow Mangrove leaves to the surface, with the intention of letting them do their thing and decompose on the substrate and "do their thing" to help enrich the habitat with tannins and humic substances. A crew of Olive Nerites snails was added to the system as a means to control the algae and "work over" the decomposing leaves, and they are remarkable for their ability to do both.

So, what we have seen over the first six or so months of this aquarium's existence has been the development of a remarkably stable, biologically active, and rich habitat. The mangroves did what I thought they'd do: They put down prop roots, and grow many leaves, some of which do dry up and fall...and of course, we do allow the leaves to accumulate on the bottom, just like in the natural habitats we are attempting to replicate to a certain extent.

Mangrove ecosystems are remarkably complex, diverse systems which process nutrients by decomposing and utilizing organic matter. Many organisms, like fungi, bacteria- even sponges, work together to utilize the vast food resources produced in these habitats. And larger creatures, like crabs, amphipods, etc., break apart leaf bits, providing a "gross dismantling" service that contributes to decomposition of these materials, leading to detritus.

Yeah, if you want to move beyond the absurd, hyper-santized hobby version of a brackish water aquarium, you need to understand how these ecosystems work, make some mental shifts to accept the appearance, the challenges, and the obligation to observe, test, and maintain these systems over the long haul.

You can do this. Easily.

Now, in the confines of an aquarium, we can't likely keep every single type of life form that we'd encounter in wild mangrove habitats- but we can incorporate some of them to perform some of the same functions-particularly the microfauna, fungi, and small crustaceans.It's a real "dance", with multiple components in play. I find this both challenging and compelling! Again, it's sort of that "functional aesthetics" thing that we talk about so much...coupled with my ability to tolerate the brown water, decomposing leaves, etc. that are essential by-products of this environment.

In wild mangrove habitats a significant amount of detritus is readily consumed by a group of specialized animals and fishes before it is being rematerialized completely in to inorganic nutrient form. And production and accumulation of detritus in these systems has been correlated by scientists to increased growth of the mangroves themselves.

Now, interestingly enough, as I've experienced with my blackwater, botanical-style aquariums, I've seen a remarkable stability in terms of the environmental parameters, and a definite solid growth in the mangrove seedlings, which was especially impressive once the roots began "touching down" and penetrating into the substrate layer.

What I'm seeing- and what I planned on seeing- is the substrate playing a very important role in the overall setup...With the mangroves growing at a significant pace, laying down thicker and thicker root structures. I have been diligent about not overfeeding the tank, but I do little to no siphoning of the substrate. Even the nutrient-rich fecal pellets of the snails are allowed to accumulate...Yeah, this is a far, far different approach than I've ever taken with any aquarium!

And I'm okay with that.

Although it seems very weird simply stating, "I'm not siphoning the bottom of my aquarium and allowing the detritus produced by decomposing leaves and such to accumulate." - I have no particular feelings of negativity attributed to this practice. I'm quite okay with it, because it's a well-managed aquarium, with the other basics of aquarium husbandry attended to.

And the idea is that I'm trying to work with the micro and microfauna which reside on the substrate, and to deprive them of their food source is, well, problematic if that's the end game, right?

This type of brackish water aquarium is truly one of the most stable, easy-to-maintain systems I've ever kept. And really, everything has been remarkably predictable! The biggest surprise was the very rapid establishment of the mangroves- in particular, the robust development of the leaves.

Now, I attribute this to multiple factors: The depth of the aquarium, which forced the roots to grow downward significantly to establish themselves, the lighting, which I believe is excellent, and the environmental parameters, which are stable and well-suited for mangrove growth.

And finally- certainly NOT the least important factor- is the rich substrate they encounter once the roots touched down. Allowing leaf drop and subsequent decomposition is mimicking exactly what happens in the natural environment. I believe that the lack of disturbance of the substrate has been and will be a continued factor in the overall "performance" of the closed brackish-water aquarium system.

It's been a grand experiment, the tinted water and rich substrate...both of which have run somewhat contrary to the vision and execution of the majority of brackish water aquariums I've seen in the hobby in recent years. There is so much more to be learned from this aquarium approach over the long term...

Perhaps the best lesson is the confidence that you can gain from executing on an idea- no matter how unconventional it might seem- if you have a fairly solid understanding of what to expect. The mangrove habitat is surprisingly well studied by science, and there is a ton of research literature out their on the ecology of these unique plants and the role that they play in their habitats. And of course, a lot of information about the habitats themselves.

Why haven't we seen more brackish water aquariums that, well- look like brackish water ecosystems? Let alone, attempt to replicate some of their function? Allow me to piss some people off again.

We need to get over ourselves. White sand and a bunch of grey rocks and salt in the water is certainly "brackish", but it doesn't really represent the ecosystem all that well, does it?

I think that it's an example of the aquarium hobby creating a stylized interpretation of this habitat for many years, as opposed to putting a bit of confidence in the environment itself, and using that as an inspiration for an aquarium setup! I heard a lot of pushback when I started playing with my brackish systems in this manner.

"It won't work in a brackish tank! It will create anaerobic conditions! Too much nutrient! Ionic imbalance...Tinted water means dirty!"

Man, this sounds so familiar...

It's about husbandry. Management. Observation. Diligence. Challenge. Occasional failure.

Yes, you might kill some stuff, because you may not be used to managing a higher-nutrient brackish water system. You have a number of variables, ranging from the specific gravity to the bioload, to take into consideration. Your skills will be challenged, but the lessons learned in the blackwater, botanical-style aquariums that we're more familiar with will provide you a huge "experience base" that will assist you in navigating the "tinted" brackish water, botanical-style aquarium.

It's not "ground-breaking", in that it's never, ever before been done like this before. However, I'm confident in stating that it's never been embraced like this before...met head-on for what it is- what it can be, instead of how we wanted to make it (bright white sand, crystal-clear water, and a few rocks and shells...).

Rather, it's an evolution- a step forward out of the artificially-induced restraints of "this is how it's always been done"- another exploration into what the natural environment is REALLY like- and understanding, embracing and appreciating its aesthetics, functionality, and richness. Figuring out how to bring this into our aquariums.

I long ago removed that certain hesitancy many have about utilizing decomposing leaves and such in our aquariums.

And I'm not alone, of course. Five plus years into our botanical-style aquarium "revolution", the global "tint" community is gaining confidence in utilizing leaves, botanicals, and other natural materials to not only achieve a certain look- but (more importantly) to replicate as much as possible the function of these impressive and alluring natural ecosystems.

We're learning that stuff like detritus is not necessarily a bad thing, and that letting it accumulate under the right circumstances shouldn't be cause for fear- particularly when it's affiliated with a closed ecosystem which an process and utilize it much in the way Nature does in the mangrove estuaries of the tropical world...

Something worth replicating, huh?

I think so.

Put together all of the elements that we have worked with in other aspects of the botanical-style aquarium, and you'll be surprised at where it can take you. We'll evolve brackish water systems from "partially-functional" simulations to a more ecologically-diverse system as we learn more and more about the variety of plants and animals that can be incorporated into such microcosms.

It's an evolving process.

Patience. Open-mindedness. Creativity. Risk. You know the drill here.

Start exploring. Stock up on some salt. Let's take a brackish trip together in 2021!

Stay bold. Stay excited. Stay grounded...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Embracing the few. And the influential.

Okay, the title of this piece sounds like a political treatise, right?

Nah, it's all about my approach botanical-style aquariums.

There is something I’ve come to embrace since I’ve been playing with botanical-style aquariums:

I like to limit elements.

Huh?

Yeah, despite having access to an incredible array of botanicals, I have found over the years that it’s more appealing to my personal taste to utilize a less diverse selection of materials in a given aquarium. And it’s not just the aesthetic thing that motivates me to do this- it’s based upon some of the environments I’ve studied.

In many of the habitats we’ve studied, you will find multiple botanical elements, like leaves, seed pods, and twigs. However, the density and combination is profoundly influenced by a number of things.

- The terrestrial environment surrounding the aquatic habitat. In a dense jungle or rain forest, you’re likely to see a significant diversity of materials. In a flooded savannah or vernal pool, you might see less materials overall, as the density of materials is influenced primarily by what’s “on the ground” already when the water returns.

- The season. During certain times of the year in many locales, there is a greater density of materials falling into the water, because various trees are shedding leaves and seed pods. Or, you’ll see more botanicals in a given body of water because the water level is lower, and these materials are concentrated.

There’s like a whole area of science devoted to this study of underwater “topography.”

To show you just how geeked-out I am about this stuff, I have literally spent hours pouring over pics and video screen shots of some of these igapo habitats over the years, and literally counted the number of leaves versus other botanical items in the shots, to get a sort of leaf to botanical "ratio" that is common in these systems.

Geeked out.

Although different areas would obviously vary, based on the pics I've "analyzed" visually, it works out to about 70% leaves to 30% "other botanical items."

The trees-or more specifically, their parts- literally bring new life to the waters. Some are present when the waters begin rising. Others continue to arrive after the area is flooded, falling off of forests trees or tumbling down from the "banks" of the stream by wind or rain.

Terrestrial trees also play a role in removing, utilizing, and returning nutrients to the aquatic habitat. They remove some nutrient from the submerged soils, and return some in the form of leaf drop.

Interestingly, studies show that about 70% of the leaf drop from the surrounding trees in the igapo habitats occurs when the area is submerged, but the bulk of that is shedded at the end of the inundation period.

The falling leaves gradually decompose and become part of the detritus in the food web, which is essential for many species of fishes. This "late-inundation leaf drop" also sets things up for the "next round" - providing a "starter" set of nutrients, doesn't it?

The materials that comprise the tree are known in ecology as "allochthonous material"- something imported into an ecosystem from outside of it. (extra points if you can pronounce the word on the first try...) And of course, in the case of trees, this also includes includes leaves, fruits and seed pods that fall or are washed into the water along with the branches and trunks that topple into the stream.

You know, the stuff we obsess over around here! In fact, everything that we add to our aquariums is, in essence, allochthonous material.

These allochthonous materials support a diverse food chain that's almost entirely based on our old friend, detritus!

Yes, detritus. Sworn enemy of the traditional aquarium hobby...misunderstood bearer of life to the aquatic habitat.

Yeah, the detritus forms not only a part of the food chain in these systems- a very important part in the diet of many of our beloved fishes...it's a literal physical structure that provides an area for fishes to forage, hide, and in some instances, spawn among.

A combination of elements- terrestrial and aquatic. All working together.

Many other fishes which reside in these flooded forest areas feed mainly on insects; specifically, small ones, such as beetles, spiders, and ants from the forest canopy. These insects are likely dislodged from the overhanging trees by wind and rain, and the opportunistic fishes are always ready for a quick meal!

Interestingly, it's been postulated that the reason the Amazon has so many small fishes is that they evolved as a response to the opportunities to feed on insects served up by the flooded forests in which they reside! The little guys do a better job at eating small insects which fall into the water than the larger, clumsier guys who are more adapted to snapping up nuts and fruits with their big, gnarly mouths!

And yes, some species of fishes specialize in detritus.

Yeah, detritus again. If we as aquarium hobbyists study the natural habitats of our fishes as diligently as some do the results of last year’s aquascaping contest, it’s easy see that not only is the word “natural” as we use it in the aquarium world really a perversion of the term, you’ll realize that natural aquatic habitats rarely look like what we think they do- and often rely on functions, processes, and materials which we tend to the nk of more as a nuisance than anything else.

Like detritus. And sediments.

We need to get over our hobby-acculturated fear of these things. In well-managed, well-thought-out aquariums, these elements are as important and functional as they are in the natural habitats we model them after. They power an entire community of organisms which influence the stability, formation, and health of fish communities.

The seasonal shift from terrestrial to aquatic is a remarkable dynamic, with amazing processes that are well worth studying- and replicating- in our aquariums!

As we have discussed more times than you likely care to remember, decomposing leaves are the basis of the food chain, and the they produce forms an extremely important part of the food chain for many, many species of fishes. Some have even adapted morphologically to feed on detritus produced in these habitats, by developing bristle-like teeth to remove it from branches, tree trunks, plant stems, and leaf litter beds.

Of course, it's not just the fishes which derive benefits from the terrestrial materials which find their way into the water. Bacteria, fungi, and algae also act upon the nutrients released into the water by the decomposing organic material from these plants.

Plants (known collectively to science as macrophytes) grow in or near water and are either emergent, submerged, or floating, and play a role in "filtering" these flooded habitats in Nature.

Many are simply terrestrial grasses which have adapted to survival under water for extended periods of time. This adds to the diversity of materials- both living and dead- in these compelling habitats.

A most interesting combination of elements, indeed.

A most compelling model.

A most fascinating example of a "functionally aesthetic" environment that you can duplicate in your home aquarium. Think about the environment, its external influences, the conditions, and the life forms that make use of it the next time you're conjuring up ideas for a new tank...It just might help you create one of the most amazing aquariums you've ever built!

In my experience, this utilization of a few elements, allowed to accumulate, decompose, and function as they do in Nature, do incredible things. For example, my several experiments with botanical-style, "self-feeding" aquariums.

Just a few botanical elements, slowly decomposing and recruiting fungal growths, biofilms, and detritus, have helped me create some very different-looking, yet smooth-functioning closed aquatic ecosystems.

Like many of the ideas we discuss here, we all have the amazing opportunity to contribute to the growing body of knowledge about this stuff!

Don't be afraid. Be motivated and inspired!

Stay part of this! Stay intrigued. Stay curious. Stay thoughtful. Stay diligent...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Out of the woods...

Okay, so I admit, I'm no expert on the use of wood in aquariums. At least, I'm no expert on what's "hot", and what the sexiest way to arrange it is.

However, as you know- I'm pretty opinionated on stuff, and I'm happy to share my thoughts, despite the peril they occasionally place me in!

My philosophy on what wood type to utilize in your aquarium is, as you might expect from me- a combination of personal aesthetic tastes and functional attributes of a given specimen.

Yeah, I think it starts out with the most simple question: What type of wood appeals to you? Sure, you can address this angle by asking yourself what type of habitat or ecological niche you're trying to recreate in your tank, and what "configuration" would be most appropriate to do the job? That's kind of my starting place.

Example?

Well, let's say you're trying to recreate the look of a tree stump or fallen tree section. You'd likely want to select a piece or pieces of wood that are thicker, "heavier-looking", and larger in size and stature to recreate such a feature. If you're trying to recreate the land/water interface of a flooded forest, and want to represent roots, then you'd likely select specimens of wood which are thinner, perhaps more twisted and gnarled in shape.

Okay, time for a little detour into a rant!

Ironically, our hobby's most popular wood type- Manzanita, is- in my opinion, probably the least "realistic" wood you can use, in terms of how it looks/works when placed in an aquarium to represent a natural scene. (I have to say it...I really hate Manzanita. IMHO, the way most people employ it, Manzanita rarely looks like something you'd see underwater in Nature..I know, bring on the hate mail 🤬)

Seriously.

Maybe it's the way we place the stuff. I mean, we typically place the piece of wood on it's side, surround it with rocks and plants, and that's that. So, it's cool...but does it represent how a piece of wood would typically look/occur in a wide flooded forest, steam, or lake?

Maybe that's it.

I'm sure plenty of people with talent do incredible stuff with Manzanita. Maybe I am just not a big fan of the stuff anymore.

Yeah, THAT'S it.

Micro hate rant over.

So, back to wood in general.

There's a fair amount of misconceptions and misinformation out there about what can work and what is not safe, etc.

And a lot of misunderstanding about where and how wood in the aquarium fits into the whole "equation" of creating a functionally aesthetic aquarium habitat...

At the risk of adding to the confusion, I'll try to clear up some stuff here.

Believe it or not, if properly prepared, almost (I say…ALMOST- don't go overboard, here) any type of dried wood can be utilized in aquariums. The important thing is that the wood must be…well, DRY! It can’t be “live”, or have any "greenwood" or sap present, as these may have toxic affects on fishes when submerged. And it can't be of a variety know to be toxic to fishes or other animals. That's pretty obvious, right?

So...sap.

Sap can be toxic to fishes, even when dry, so if you see a piece of wood- even dry- that’s displaying some sap- it might be a good idea to remove the section where the sap is coming from, or to simply take a pass. And avoid wood with lots of sap, or that is known to contain stuff like that (Like, pine- which is a non-starter, right?)

In general, when it comes to wood, in our experience, it’s a better idea to purchase/collect your wood from sources known to offer “aquarium safe” wood, and not worry about suitability, toxic concerns, etc.

"Driftwood" is a nome de guerre I the hobby; a sort of a generic term for wood that has been dried over time, generally free of bark, (which, other than containing tannins and polyphenols, that are largely non-toxic in reasonable concentrations- is not that problematic, actually) and "greenwood" as outlined above. In most trees, the real chemically active substances are found in the leaves, live “greenwood”, and the sap.

So, a dry, largely bark-stripped piece of wood, free from sap, dried or otherwise, is generally pretty good to go, and is relatively stable and neutral.

Now, a lot of people ask me how we arrive at the selection of wood that we do, and why we don't offer certain types, yet offer others...

When it comes to the types of wood we offer, it's pretty straightforward.

I select stuff that I think is cool.

You might fucking hate everything I offer. I understand. And that's okay, because there are plenty of vendors out there who offer everything you could want, wood-wise. I just offer stuff I think would work with the kinds of aquariums we play with.

It seems to me that, on any given day, such-and-such a wood type is the "IT" variety, and everyone wants it. Some guy does a tank with this scraggly shit emerging from the water, posts a few sexy pics on his Instagram feed, and the next thing you know...trend. Everyone wants it. Now.

As someone who offers natural aquascaping materials for use in specialized aquariums, I long ago realized that I needed to stop chasing every hot type of wood that shows up on the market. I am generally clueless on "what's hot" in the aquascaping wood world, nor do I really care, to be perfectly honest.

"Scott, that's not very customer-centric. You claim to be so consumer focused, but it sounds like you couldn't care less what the market wants when it comes to wood!"

Yeah, confession. You're correct.

Because I'd go crazy trying to chase after all the "trendy" stuff all the time...And I'd be selling myself out offering stuff that I wouldn't want to use in my own tanks.

We'll continue to offer types of wood that we enjoy using in our own 'scapes. Some will just happen to be ones that are popular and relatively common- or even "trendy" at the moment. Some will be types which fell out of favor with the mainstream 'scaping world. Some will be obscure, niche-specific stuff. We will constantly introduce new varieties as we encounter them.

The majority, however, will simply be stuff that we think works.

That answers that, I hope?

Of course, that also means I'm really the last guy who should be discussing what wood to use in your aquascapes. Why am I talking about this topic at all? Well, there are plenty of vendors who write "authoritative" articles on botanicals who are more clueless than I am about wood, so...

(ohh, had your coffee today, Fellman?)

Let's lighten this up a bit.

Instead, lets have a brief discussion on what happens at that magical moment when we place wood in water...

It starts by considering the source of the wood.

Well, shit- it comes from (wait for it...) trees.

BOOM! Minds blown, I know!

For the sake of this discussion, let's just assume that you're working with wood that's been properly collected and is suitable for aquarium use.

When you first submerge wood, a lot of the dirt from the atmosphere and surrounding environment comes off, along with tannins, lignin, and all sorts of other "stuff" from the exterior surfaces and all of those nooks and crannies that we love so much. And a piece of wood initially emersed in water typically floats, much to our chagrin, right?

And of course, there are the tannins.

Now, I don't know about you, but I'm always amused (it's not that hard, actually) by the frantic posts on aquarium forums from hobbyists that their water is turning brown after adding a piece of driftwood. I mean- what's the big deal?

Oh, yeah, not everyone likes it...I forgot. 😂

The reality, as you probably have surmised, is that driftwood will continue to leach tannins pretty much for as long as it's submerged. As a "tinter", I see this as a great advantage in helping establish and maintain the blackwater look, and to impart the humic substances that are known to have health benefits for fishes.

Some wood types, like Mangrove, tend to release more tannins than others over long periods of time. Other types, like "Spider Wood", will release their tannins relatively quickly, in a big burst. Some, such as mangrove wood, seem to be really "dirty", and release a lot of materials over long periods of time.

And it's a unique aesthetic, too, as we rant on and on about here!

What I'm more concerned about are the impurities- the trapped dirt and such contained within the wood. As you probably know, that's also why I'm a staunch advocate of the overly conservative "boil and soak approach" to the preparation of botanicals as well. A lot of material gets bound up in the dermal layer of the tree where the wood comes from. Atmospheric dust, pollutants, bird droppings, insects, etc. None of this is stuff you want in your tank, right?

Generally, no. I suppose, however, some could take the view that this stuff is "fuel" for microorganism growth and run with it.

What other sort of stuff is in wood?

The bulk of the dry mass of the xylem (the "network" within the tree which transports water and soluble mineral nutrients from the roots throughout the plant, and comprises what we know as "wood.") is cellulose, a polysaccharide, and most of the remainder is lignin, which is a sort of complex polymer.

Why the botany lesson?

Well, because when you have some idea of what you're putting into your tank, you'll better understand why it behaves the way it does when submerged! In a given piece of driftwood, there is going to be some material bound up in these structures, and it will be released (gradually or otherwise) into the water that surrounds it, with a big "burst" happening on initial submersion. This is why, during the first couple of weeks after you submerge wood, that the water often becomes dark- and even cloudy.

There is a lot of "stuff" in there!

It's far better, in my opinion, for most hobbyists to take the time to start the "curing" process in a separate container apart from the display aquarium. This is not rocket science, nor some wisdom only the enlightened aquarists attain.

We all know this, right?

It's common sense, and a practice we all need to simply view as necessary with terrestrial materials like wood and botanicals. You may love the tannins as much as I do, but I'm confident that your tank could do without those polyscaccharides and other impurities from the outer layers of the wood. The potential affects on water quality are significant!

It's pretty plain to see that at least part of the reason we see a burst of new algae growth and biofilm in wood recently added to an aquarium is that there is so much stuff bound up in it. That "stuff" is essentially "algae fuel" when added to water. Algal and fungal sports can literally "bloom" during the initial period after submersion, and this alone is great reason to take the long, slow approach to wood prep.

Interestingly, the same "process" of "curing" happens naturally when tree trunks and branches fall into wild aquatic habitats.

It's not necessarily a "quick" process in Nature, either. So, we need not feel too bad about playing a "waiting game" when it comes to curing wood for aquariums

Could you boil wood and speed up the process?

Well, sure- if you have a cauldron or something large enough. SO, most of us just soak.

And we've talked about "in situ" curing of wood. You CAN do that. Absolutely, as we've discussed. I've done this a lot. However, it means a large amount of stuff being released into the water. It means levels of possible impurities that would demand significant water exchanges and aggressive use of chemical filtration...and there is NO way you'd want to add fishes for some time.

So, yeah- If you're patient, understand the need to maintain water quality, and can handle just looking at an empty tank with wood and botanicals in it...Have at it.

Suffice it to say, that wood, when being submerged in an aquarium, will likely leach tannins into the water. It'll make the water dark...So, you "know the drill"- use activated carbon in quantity if you don't want this tint in your aquarium.

And biofilms and fungi, which we've written about dozens of times in this very blog- will likely make their appearance at some point. We've talked ad nauseam how to deal with this stuff...

Yeah...that's like a whole different discussion we could have.

Bottom line here?

Choose the wood you like, which you feel best represents the habitat that you're trying to recreate. Understand that it will require preparation (soaking, etc.) before its really "set for use"- and that ideally, this should occur in a operate container instead of the aquarium it's ultimately destined for. Realize tannins and biofilms happen. While most wood types have their own "behavior" in the water, they all are comprised of the same substances, so there are generalities that make one type as good as any other.

Be creative with how you use wood.

Combine it with other materials- or blend different wood types. Be original.

Kick some aquascaping ass.

Rant over.

Stay creative. Stay excited. Stay thoughtful. Stay bold...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Surface film and other annoyances...

Someone asked what's the thing that I hate the most about botanical-style aquariums. I had to give it a lot of thought, but I think I found it.

I hate surface film.

What exactly is "surface film", and why is Scott so obsessed about the stuff?

Surface film is a sort of "aquarium vernacular" for "surface active compounds"- a scum of organics, microorganisms, proteins, and good old fashioned "dirt", among other things- which accumulates on the surface of the aquarium. Large organic molecules are not generally very soluble. They tend to adhere to all sorts of surfaces- the water/air interface being one such place that is immediately "in our faces" and is rather objectionable in appearance!

In some instances ,it's unavoidable- you know, like my ultra-small "urban Igapo" tanks, which typically run without any filters.

However, in larger, lightly-filtered tanks, this stuff becomes more of an issue to me.

The air/water interface is the "boundary" (technically called the "surface micro layer" by scientists) where all exchange occurs between the atmosphere and the aquatic environment. Interestingly, the The chemical, physical, and biological properties of the SML can differ significantly from the water just a few centimeters beneath the surface!

In Nature, the concentration of these surface compounds depends on the source of the nutrients, as well as weather, like rain and wind. These organic compounds on the surface impact the the very physical and light admittance properties on the air/water interface.

As aquarists, the biggest concern is that the surface film can interfere with gas exchange. Oh, and it looks like shit, right?

Yeah, always seems to come back to aesthetics over almost everything, huh?

Well, maybe...

You see this stuff in almost every aquarium with a varying degree of annoyance, and it's just something that we "deal with", right? Yeah, pretty much. And the reality is that it's likely not a huge deal for many hobbyists or their tanks. I mean, it's been something we've seen in tanks for over a century...and in the days before aquarium filters arrived, it was not an issue we heard mice about. And when we had goldfish in bowls as kids, it never seemed to bother us (so many other things about a goldfish in a bowl should have, right?)

Yet it's there. And to some of us, it's really ugly!

How do you deal with it?

Well, there are a few ways.

First, you can employ an aquarium which incorporates an overflow weir, which pulls water from the surface into the filter or filter chamber. That's what I am a huge fan of reef-ready aquariums, or many of the so-called "all-in-one" tanks, which draw water from the surface into the filter. This is a convenient way of pulling the most organic-rich water in the aquarium right into the filter.

The other alternative is to employ a surface skimming device.

Without me embarrassing myself while attempting to describe the way these things work, let's just say that they a device which employs an intake at the water surface, a small body, with an internal pump to draw in the water. These little gadgets do a remarkably good job at removing the aforementioned surface film. Now, I admit, they kind of look, well- shitty- but they are relatively easy to hide in most tanks, and get the job done!

If you're like me, and you hate looking at mechanical devices in your tanks, you either: 1) learn to live with it and appreciate the nice clean water surface, 2) hide the damn thing with clever hardscape, or 3) deal with the fucking surface film.

Oh, before I wrap up this short, but epic treatise on one of my personal aquarium "pet peeves", I'd be remiss if I didn't mention my fave of the bunch..

The "Porsche" of surface skimmers, the Tunze Comline 3161. A beast of a device, it's a little thing, too (4.5” x 2.4” x 6.9”), and fits nicely into most small tanks, including the aggravating ADA 60F (which is only like 7" tall).

Like everything Tunze makes, it's seriously engineered, with innovative features and a powerful silent pump. Tunze makes reef-keeping gear, which means that it's designed for harsh environments and doesn't suck. So yeah, it's more expensive than the inexpensive knock of crap you find on Amazon or whatever, but it actually works. A good trade-off IMHO. This thing could easily serve as the sole filter/surface skimmer in a nano-sized tank, perhaps even one approaching 15 U.S. gallons (60L).

If you can hide it, it's worth every penny.

Again, the idea of surface film is just something that we have to deal with in the botanical-style aquarium. And to many of you, it's no biggie. A non-issue, really. However, with a lot of decomposing leaves, botanicals, and other materials, it's probable that at some point, you're going to encounter stuff like this. Sure, you can deal with the stuff with good surface agitation, too...But it always seems to accumulate in some far corner of the tank.

Yeah, surface agitation. Good!

So, you asked...I'm sharing. That's my aggravation...served up for your consideration!

Stay unfazed. Stay calm. Stay happy. Stay innovative. Stay resourceful...

And Stay Wet.

Shrimp and "Anecdotal Nutrition?"

As botanical-style aquarists, we are keenly aware of the benefits of utilizing botanicals and leaves in our aquariums, so we're kind of used to the idea of them impacting our animals and aquarium habitats in a variety of ways. We are keenly aware that leaves and botanicals contain numerous compounds, ranging from humic substances and tannins, to stuff like lignin, cellulose, and even minerals.

We've seen what some of this stuff can do for our aquariums.

We've seen it with our own eyes; gauged the results for for ourselves.

And there are still more questions than answers.

We have them. We receive a lot of them.

We receive a lot of questions from shrimp keepers, asking about the various merits of utilizing botanicals for environmental enrichment and nutrition for their animals. I love shrimp keepers, because they remind me a lot of reefers- absolutely obsessed with the well-being of their animals, with a heavy focus on finding materials or approaches which will benefit the shrimp.

And, like reefers, shrimpkeepers are bombarded by a lot of marketing, inflated claims of benefits, anecdotal assumptions, and out right falsehoods. And, like reefers, many have a built-in "bullshit meter" to look at some of these claims with a skeptical eye.

And they should. There is a LOT of stuff said about botanical materials and their use as food for shrimps- and some of it IS outright BS. Some of it is not, but it's pretty anecdotal, and if taken without question, might create the incorrect impression that these materials are more beneficial to shrimp than they really are.

The problem is that we know "a little" about the potential nutritional value of botanicals for shrimp- and that might spur a lot of speculation.

Huh? Well, let's look at what we DO know about this topic. It's safe to say that most leaves and botanicals contain vitamins, amino acids, micronutrients, and other bioavailable compounds.

The real question I have is exactly how "available" they are to our shrimp from a nutritional standpoint. And how "nutrient dense" these leaves and botanicals are? Do our fishes and shrimp easily assimilate all they need in every bite, or do they have to eat tons of the stuff to derive any of these benefits?

Big questions, right?

I mean, we as hobbyists sort of assume that if these things are present in the botanicals, then our animals get a nice dose of 'em in every bite, right? And, it begs the question: Are they really directly consuming stuff like Casuarina cones, or feeding on something else on their surfaces (more on this later)?

I think it's "yes" on both.

And the nutrition that they derive from consuming them?

Well, that's the part where I say, I don't know.

I mean, it seems to make a lot of sense to me...However, is there some definitive scientific information out there to prove this hypothesis?

A lot of the "botanicals for food thing" in the hobby (no, really- it's a "thing!") comes from the world of shrimp keepers. This isn't new stuff to them. They've been touting this stuff in the hobby for a long time. A lot of it is based upon the presence of materials like leaves and such in the wild habitats where shrimp are found. I did some research online (that internet thing- I think it just might catch on...) and learned that in aquaculture of food shrimp, a tremendous variety of vegetables, fruits, etc. are utilized, and many offer good nutritional profiles for shrimp, in terms of protein, amino acids, etc.

They're all pretty good. Our friend Rachel O'Leary did a great job touching on the benefits of botanicals for shrimp in her video last Fall.

So, which one is the best? Is there one? Does it matter? In fact, other than sorting through mind-numbing numbers ( .08664, etc) on various amino acid concentrations in say, Mulberry leaves, versus say, Sugar Beets, or White Nettle, or whatever, there are not huge differences making any one food vastly superior to all others, at least from my very cursory, non-scientific hobby examination!

Now, leaves like Guava, Mulberry, etc. ARE ravenously consumed by shrimp and some fishes. It's known by scientific analysis that they do contain compounds like Vitamins B1, B2, B6, and Vitamin C, as well as carbohydrates, fiber, amino acids, and elements such as Magnesium, Potassium, Zinc, Iron, and Calcium...all important for many organisms, including shrimp. Guava leaves are particularly good, according to some of the studies I read because, apparently, the bulk of the nutrients they contain are more "readily available" to animals than other leaves.

Well, that's pretty important, isn't it?

I think so!

Now, it may be coincidental that these much-loved (by the shrimp, anyways) leaves happen to have such a good amount of nutritional availability, but it certainly doesn't hurt, right?

Other leaves, such as Jackfruit, contain "phytonutrients", such as lignans, isoflavones, and saponins that have health benefits that are wide ranging for humans. There is some conflicting data regarding Jackfruit's alleged antifungal capability However, the leaves are thought to exhibit a broad spectrum of antibacterial activity in humans. In traditional medicine, these leaves are used to help heal wounds as well.

Do these properties transfer over to our fishes and shrimp?

We are not aware of any scientific studies that have been completed to correlate one way or another. That being said, they seem to flock to these leaves and graze on them directly- and on the biofilms which accumulate on their surface tissues.

Oh, the biofilms again!

As I mentioned before, the "shrimp side" of the hobby reminds me in some ways of the coral part of the reef keeping hobby where I spent considerable time (both personally and professionally) working and interacting with the community. There are some incredibly talented shrimp people out there; many doing amazing work and sharing their expertise and experience with the hobby, to everyone's benefit!

Now, there are also a lot of people out there in that world -vendors, specifically- who make some (and this is just my opinion...), well - "stretches"- about products and such, and what they can do and why they are supposedly great for shrimp. I see a lot of this in the "food" sector of that hobby specialty, where manufacturers of various foods extoll the virtues of different products and natural materials because they have certain nutritional attributes, such as vitamins and amino acids and such, valuable to human nutrition, which are also known to be beneficial to shrimp in some manner.

And that's fine, but where it gets a bit anecdotal, or - let's call it like I see it- "sketchy"- is when read the descriptions about stuff like leaves and such on vendors' websites which cater to these animals making very broad and expansive claims about their benefits, based simply on the fact that shrimp seem to eat them, and that they contain substances and compounds known to be beneficial from a "generic" nutritional standpoint- you know, like in humans.

All well-meaning, not intended to do harm to consumers, I'm sure...but perhaps occasionally, it's just a bit of a stretch.

I just wonder if we stretch and assert too much sometimes?

Now, I'm not saying that it's "bad" to make inferences (we do it all the time with various topics- but we qualify them with stuff like, "it could be possible that.." or "I wonder if..."), but I can't stand when absolute assertions are made without any qualification that, just because this leaf has some compound which is part of a family of compounds that are thought to be useful to shrimp, or that shrimp devour them...that it's a "perfect" food for them, with enormous benefits.

It's just a food- one of many possibilities out there. That's how I think we need to look at things.

Of course, I hope I'm not out there adding to the confusion! We try to hold ourselves to higher standards on this topic; yet, like so many things we talk about in the world of botanicals, there are no absolutes here.

What is fact is that some botanical/plant-derived materials, such as various seeds, root vegetables, etc., do have different levels of elements such as calcium and phosphorous, and widely varying crude protein. Stuff that's known to be beneficial to shrimp, of course. These things are known by science, largely through studies down on shrimp farmed for human consumption.

Yet, I have no idea what some of the seed pods we offer as botanicals contain in terms of proteins or amino acids, and make no assertions about this aspect of them, above and beyond what I can find in scientific literature.

No one else does, either.

However, I suppose that one can make some huge over-generalizations that one seedpod/fruit capsule is somewhat similar to others, in terms of their "profile" of basic amino acids, vitamins, trace elements, etc. (gulp). We can certainly assume that some of this stuff, known to have nutritional value, can make these materials potentially useful as a supplemental food source for fishes and shrimps.

Yet, IMHO that's really the best that we can do until more specific, scientifically rigid studies are conducted. And we can feed a wide variety of stuff to our shrimp- sort of the equivalent of throwing a bunch of spaghetti on the wall to see what sticks!

Now, we may not know which seed pods and such in and of themselves are more nutritious to fishes and shrimp than others, but we DO know from simple observation that some are better at "recruiting" materials on their surfaces which serve as food sources for aquatic organisms!

Yeah, I'm talking about the biofilms and fungal growth, which make their appearance on our botanicals, leaves, and wood after a few weeks of submersion...

We know that shrimp seem to love grazing on biofilms, and that the nutritional benefits of biofilms are pretty well established. They are a rich source of sugars and other nutrients, and could even prove to be an interesting addition to a "nursery tank" for raising fry and larval shrimp. Like, add a bunch of leaves and botanicals, let them do their thing, and allow your fry to graze on them!

And of course, it's long been known from field studies that as leaves and other plant materials break down, they serve as "fuel" for the growth of biofilm, fungi and microorganisms...which, in turn, provide supplemental food for fishes and shrimps. I've seen a bunch of videos of shrimps and fishes in the wild "grazing" over fields of decomposing leaves and the biofilms they foster.

Ahh, biofilms again.

Refresher for you:

Biofilms form when bacteria adhere to surfaces in some form of watery environment and begin to excrete a slimy, gluelike substance, consisting of sugars and other substances, that can stick to all kinds of materials, such as- well- in our case, botanicals.

Biofilms on decomposing leaves are pretty much the foundation for the food webs in rivers and streams throughout the world. They are of fundamental importance to aquatic life.

It starts with a few bacteria, taking advantage of the abundant and comfy surface area that leaves, seed pods, and even driftwood offer. The "early adapters" put out the "welcome mat" for other bacteria by providing more diverse adhesion sites, such as a matrix of sugars that holds the biofilm together. Since some bacteria species are incapable of attaching to a surface on their own, they often anchor themselves to the matrix or directly to their friends who arrived at the party first.

Hmm, sounds sort of like Instagram, huh?

(The above graphic from a scholarly article illustrates just how these guys roll.)

And we know from years of personal experience and observation in the aquarium that fishes and shrimp will consume them directly, removing them from virtually any surface they form on.

And some materials are likely better than others at recruiting and accumulating biofilm growth. The "biofilm-friendly" botanical items seem to fall into several distinct categories: Botanicals with hard, relatively impermeable surfaces, softer, more ephemeral botanical materials which break down easily, and hard-skinned botanicals with soft interiors, and...

Okay, wait- that kind of covers like, everything, lol.

Yeah.

There are a few that really stand out, like the Dysoxylum pod.

Dysoxylum binectariferum, which is found in the forests of tropical India, but ranges as far afield as Vietnam. It's found in in alluvial soil conditions (clay and sand) and along rivers and streams...right up our proverbial "alley", huh?

In India, it is also known by many other names such as, "Indian White Cedar", "Bili devdari", "Bombay White Cedar", "Velley Agil", "Porapa", "Vella agil", and "Devagarige."

The tree is an important component of tropical rain forests, typically from India, but found in other regions.

The tree grows to height of 120feet/40 m height, has bark which is greyish-yellow in color, with inner bark a creamy yellow color. The fruits that ripen during June–July are capsules. In India, apart from its economic importance for building and furniture making, it is an important ingredient in traditional medicine. The fruit has a chemical composition known by the name “ashtagandha”, which means "fragrant smell", and is used for making incense sticks that are commonly used for worship.

Interestingly, compounds derived from the tree itself are also known by modern medical researchers to have extremely valuable medicinal properties...

Notice, we said, "the tree itself?"

Dysoxylum binectariferum bark was identified as an alternative source of CPT, through a process of bioassay-guided isolation. Camptothecin ( known to clinical researchers as "CPT 1") is a potent anticancer product, which led to the discovery of two other clinically used anticancer drugs, Topotecan and Irinotecan.

Rohitukine is another compound that accumulates in a significant amount in seeds, trunk bark, leaves, twigs, and fruits of D. binectariferum. Rohitukine is an important precursor for the synthesis of other potential anticancer drugs

Wow!

And all I wanted was some seed pods to feed shrimp! With all of those medicinal uses, has anyone ever used them before in aquariums before we started playing with them for this purpose?

I'm doubtful, but you never know...

And why did I just go on a tangent about this tree and it's seed pod?

Because it's an example of the kind of information that you can extrapolate from areas of study outside of aquariums. And half of the benefits ascribed to Dysosxylum are based on its bark and leaves, neither of which we work with.

You can make all sorts of inferences and assumptions about their benefits, and how they might apply to shrimp, solely based on this kind of stuff.

Don't do that.

Don't assume that, because the tree and its other parts have compounds which are known to provide certain benefits, that it's 100% certain that the seed pods do, too.

Yeah, we utilize the seed pod. Not the bark, the branches, or the leaves. We know that our shrimp eagerly graze on its soft interior, and the biofilms which are recruited on the pod as it breaks down.

Research, experiment, and draw your own conclusions, based on the performance you experience with your shrimp. Don't rely on anecdotal assumptions. Don't assume that because the tree can do all of these things, that the leaves or seed pods can do them, too...and that they can impart such benefits to shrimps!

"Anecdotal nutrition" is something we shouldn't accept without some skepticism.

It's a lot to take in- and I see how this might be a bit disappointing to some. The reality is that this is exciting- it's invigorating, because sorting through the sea of anecdotal assumptions and hypothesis, in an effort to benefit our animals, is incredibly exciting!

Stay informed. Stay bold. Stay curious. Stay excited. Stay resourceful...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

The start of the journey...And the direction it takes us...

It seems incredible to me that the world of blackwater, botanical-style aquariums is still “finding its tribe”, with lots of hobbyists trying this approach for the first time. And as the techniques evolve, the processes become more refined..or even more unusual.... I was thinking about this today when I was playing with a new tank I'm starting up in my office.

I utilized some mangrove wood which was not really "cured"- something I've done before with this wood, and the inevitable cloudiness and tint came quickly. And it got me thinking...

When you add botanicals to an aquarium, particularly a brand new one, there is almost always some sort of cloudiness initially. This is caused by several factors, ranging from good old “dirt” coming off of their surfaces, to dissolving lignin, cellulose, and of course, tannins. It’s a complex organic “brew”, which is released into the water as the materials begin to break down.

Of course, all of this material dissolving into the aquarium can create cloudiness.That's probably your first sign that "things" are happening! We often see such cloudiness in aquariums when we may not have fully prepared our botanicals, or wood.

Will it go away on its own, without our intervention?

In my experience, it will...eventually. And of course, "eventually" can be days, weeks...or longer. No guarantees. And "without our intervention" is a sort of vague thing. You can let Nature sort it out, as she's done for eons. I mean, you could...could- even "cure" wood and botanicals "in situ." I've done it before. I wouldn't recommend it, however.

"Well, shit, Scott- you said you 'could'- so how would you?"

Damn, I did. And I can run the risk of being pretty irresponsible here, I know. Let me elaborate further.

Well, there are a few approaches you can take to managing this stuff.

You can employ some chemical filtration media, such as activated carbon, to help clear up the cloudiness and perhaps remove some of the organics. You could perform water exchanges, with the knowledge that this may disrupt or slow the development of a significant population of beneficial bacteria.

You can do this. You won't be adding fishes for a while, but you can do this. You can add bacteria, however. In fact, this is where our bacterial inoculant, "Culture", can excel. It is comprised of the hardy, incredibly versatile Purple Non-Sulphur Bacteria (PNSB), Rhodopseudomonas palustris.

Like nitrifying bacteria, PNSB metabolize ammonium and nitrite and nitrate. And they're not just important to the nitrogen cycle. They're also capable of aerobic organoheterotrophy - a process of removing dissolved organics from the water column- just like other microbes!

PNSB are useful for their ability to carry out a particularly unusual mode of metabolism: anaerobic photoheterotrophy. In this process, they consume organic wastes while inhabiting moderately illuminated and poorly oxygenated microhabitats (patches of detritus, leaf litter beds, shallow depths of substrate, deeper pores of expanded clay media, etc.).

By competing with other anaerobes such as methanogenic archaeans (more about them later) and sulfate-reducing bacteria for food, these voracious "sludge-eaters" significantly reduce the production of toxic byproducts such as methane and hydrogen sulfide!

It’s important to understand that your best allies in the cause of establishing a new aquarium are bacteria and fungi, as we’ve talked about repeatedly.

Bacteria will arrive in your aquarium through a number of means- on leaves and seed pods, in substrate (particularly if you’re using material from an established one), wood, etc. The nitrifying bacteria that we admire so much are present in almost every aquatic system- even a brand new aquarium. However, there simply aren’t enough of them in a new aquarium to process the waste produced by a significant fish population. And of course, to grow the population of these beneficial bacteria, you need to supply then with their major energy source- ammonia.

Without re-hashing the whole well-trodden nitrogen cycle stuff, we know by now that these bacteria will oxidize the ammonia and convert it to nitrite, which a second group of bacteria process and convert to less harmful compounds, specifically, nitrate. When both of these types of bacteria reach a population sufficient to process the available energy sources, you’ve got an aquarium that’s “cycled.”

"Aquarium Keeping 101", right?

Yeah, it should be.

Of course, with the pH in blackwater aquariums generally falling into the range of 6.0-6.8, you’ll see a slower processing of ammonia and nitrite. And when you get really low pH, as we’ve talked about before (like 5.5pH or lower), these organisms essentially shut down, and a new class of organism, Archaens, take over. Now, that;’s a whole different thing for a different blog, but suffice it to say, the lower pH, botanical-style/blackwater aquarium is a different animal altogether!

I think that the real key ingredient to managing a low pH system (like any system) is our old friend, patience! It takes longer to hit an equilibrium and/or safe, reliable operating zone. Populations of the organisms we depend upon to cycle waste will take more time to multiply and reach levels sufficient to handle the bioload in a low-pH, closed system containing lots of fishes and botanicals and such.

This certainly gives the bacterial populations more time to adjust to the increase in bioload, and for the dissolved oxygen levels to stabilize in response to the addition of the materials added-especially in an existing aquarium. Going slowly when adding are botanicals to ANY aquarium is always the right move, IMHO.

And at those extremely low pH levels?

Archaens.

They sound kind of exotic and even creepy, huh?

Well, they could be our friends. We might not even be aware of their presence in our systems...If they are there at all.

Are they making an appearance in our low pH tanks? I'm not 100% certain...but I think they might be. Okay, I hope that they might be.

Refresher:

Archaeans include inhabitants of some of the most extreme environments on the planet. Some live near vents in the deep ocean at temperatures well over 100 degrees Centigrade! true "extremophiles!" Others reside in hot springs, or in extremely alkaline or acid waters. They have even been found thriving inside the digestive tracts of cows, termites, and marine life where they produce methane (no comment here) They live in the anoxic muds of marshes (ohhh!!), and even thrive in petroleum deposits deep underground.

.

(Image used under CC 4.0)

Yeah, these are pretty crazy-adaptable organisms. The old cliche of, "If these were six feet tall, they'd be ruling the world..." sort of comes to mind, huh?

Yeah, they’re fucking beasts….literally.

Could it be that some of the challenges in cycling what we define as lower ph aquariums are a by-product of that sort of "no man's land" where the pH is too low to support a large enough population of functioning Nitrosomanas and Nitrobacter, but not low enough for significant populations of Archaea to make their appearance?

I'm totally speculating here. I could be so off-base that it's not even funny, and some first year biology major (who happens to be a fish geek) could be reading this and just laughing…

I still can't help but wonder- is this a possible explanation for some of the difficulties hobbyists have encountered in the lower pH arena over the years? Part of the reason why the mystique of low pH systems being difficult to manage has been so strong?

Could it be that we just need to go a LOT slower when stocking low pH systems?

Yeah, we should go slower.

And yes, you can "cure" everything in situ, fi you understand what's happening, what the potential downsides are, and how to manage this process. You need to just be patient.

Right after the initial "break in" and "cycling" process comes the next phase-

Decomposition.

Decomposition of plant matter-leaves and botanicals- occurs in several stages.

It starts with leaching -soluble carbon compounds are liberated during this process. Another early process is physical breakup or fragmentation of the plant material into smaller pieces, which have greater surface area for colonization by microbes.

And of course, the ultimate "state" to which leaves and other botanical materials "evolve" to is our old friend...detritus.

And of course, that very word- as we've mentioned many times here- has frightened and motivated many hobbyists over the years into removing as much of the stuff as possible from their aquariums whenever and wherever it appears.

Siphoning detritus is a sort of "thing" that we are asked about near constantly. This makes perfect sense, of course, because our aquariums- by virtue of the materials they utilize- produce substantial amounts of this stuff.

Now, the idea of "detritus" takes on different meanings in our botanical-style aquariums...Our "aquarium definition" of "detritus" is typically agreed to be dead particulate matter, including fecal material, dead organisms, mucous, etc.

And bacteria and other microorganisms will colonize this stuff and decompose/remineralize it, essentially "completing" the cycle.

Decomposition is so fundamental to our "game" that it deserves mentioning again and again here!

Now, a lot of people may disagree, but I personally feel that THIS phase, when stuff starts to break down, is the most exciting and rewarding part of the whole process!

And perhaps- one of the most natural...

How we start our systems- the approach that we take, the way we react and adjust- are fundamental parts of the equation. And yeah, there ARE a lot of different ways you can go. Some will raise a few eyebrows. Some will make fellow hobbyists think that you're crazy. But you CAN take different routes.

And you should at least think about them now and then.

Stay creative. Stay studious. Stay engaged. Stay excited...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Water with "flavor", and the distinctions between color and clarity...

One of the interesting "side effects" of being called "Tannin Aquatics" is that you give everyone the impression that all you specialize in is creating aquariums with lots of leaves and stuff and golden-brown, tinted water.

Makes sense, for sure. And yeah, we like to think of ourselves as big fans and supporter of the blackwater, botanical-style aquarium. However, I think it's okay to mention that it's also okay NOT to tint. It's okay to embrace all sorts of different looks.

Huh? Why are you even discussing this?

Well, it's because so many people ask me questions about this stuff, and what defines a botanical-style aquarium, and what makes "blackwater", and...

Somewhere along the line, some hobbyists seem to feel that the the idea of a botanical-style aquarium is only one that has golden-brown water. It must have a certain look.

Ridiculous, I say. Where this kind of crap comes from, I'm not sure.

Yeah, I'm saying it here: You can use botanicals and other natural materials in aquariums that are essentially clear water. It's not uncommon to find leaves, twigs, and other botanical materials in wild habitats which have essentially clear water.

And of course, you can do the same in the aquarium.

Let's just reinforce this by sharing a bit of information about some of my favorite habitats in South America, the Orinoco flood plains. As always, it seems to go back to geology.

In the Orinoco, you have blackwater and "white water" areas. The"white water" habitats, although not deeply tinted, nor crystal clear, are often a bit turbid. The seasonal turbidity of these “white waters” can be significant, and can actually help support some benthic algal growth.

These "white waters" contain large amounts of dissolved and suspended solids, which are produced by weathering of the soils and rocks high in the Andes. This rapid "weathering" produces the seasonal turbidity we're talking about here. Examples of "white water" rivers would be the main course of the Amazon, as well as the Japura and Jurua rivers.

By contrast, black waters flow primarily through the Guayana Shield, which has been weathered so extensively over the eons that it contributes only small amounts of suspended and dissolved solids into the water. We've talked about this many times before.

More confusing (or interesting, actually): Because it receives both whitewater and blackwater tributaries, the Orinoco is a mixture of water types with of strongly contrasting physical, chemical, and biological characteristics. A most interesting mix!

And then, there are rivers like the Tapajos or the Xingu, which have an almost greenish tint to them, although ecologists classify it as a "clearwater" river. They flow from the geologic structure known as the "Central Brazilian Archaic shield", and have low amounts of sediments and dissolved solids. These waters feature a lot of wood and fine, sandy substrates.

So, the point of all of this geological meandering to illustrate that the world of water is every bit as complex as any other aspect of the natural world.

And if it has you a bit confused, don't be. The point that I'm trying to make here is that the color of the waters which we obsess over are an amalgamation of a variety of factors, many of which we can replicate, to some extent, in the aquarium.

When we add materials such as leaves, wood, and seed pods to water, they impart tannins, humid substances, and other materials into the water. This is similar to what happens in Nature, however, it's only part of the process, as we've discussed before.

And of course, you have the whole issue of turbidity and clarity.

we as fish geeks seem to associate color in water with overall "cleanliness", or clarity. The reality is, in many cases, that the color and clarity of the water can be indicative of some sort of issue, but color seems to draw an immediate "There is something wrong!" from the uninitiated!

And it's kind of funny- if you talk to ecologists familiar with blackwater habitats, they are often considered some of the most "impoverished" waters around, at least from a mineral and nutrient standpoint.

In the aquarium, the general hobby at large doesn't think about "impoverished." We just see colored water and think..."dirty."

And of course, this is where we need to separate two factors:

Cloudiness and "color" are generally separate issues for most hobbyists, but they both seem to cause concern. Cloudiness, in particular, may be a "tip off" to some other issues in the aquarium. And, as we all know, cloudiness can usually be caused by a few factors:

1) Improperly cleaned substrate or decorative materials, such as driftwood, etc. (creating a "haze" of micro-sized dust particles, which float in the water column).

2) Bacterial blooms (typically caused by a heavy bioload in a system not capable of handling it. Ie; a new tank with a filter that is not fully established and a full compliment of livestock).

3) Algae blooms which can both cloud AND color the water (usually caused by excessive nutrients and too much light for a given system).

4) Poor husbandry, which results in heavy decomposition, and more bacterial blooms and biological waste affecting water clarity. This is, of course, a rather urgent matter to be attended to, as there are possible serious consequences to the life in your system.