- Continue Shopping

- Your Cart is Empty

Excuse our dust...er, not! The "Sedimented Substrate" thing!

"Some sediment and sand meet in a river, and..."

Okay, weird opening, but it's time to launch NatureBase!

Wow, sometimes, you start realizing that what you've been obsessing about for so long might actually be interesting to other people, too! Lately, I started talking a bit more specifically about the specialized substrates that I've been working on for the past couple of years- and the response has been nothing short of crazy...And it taught me some things- well, reinforced some things- which I believe in. specifically:

1)There is a hunger for new and unique aquarium substrates.

2) Aquarists are ready for something new, that is not just about the "look", and are willing to be a bit adventurous...

3) Those of us in the industry have been doing a sort of lackluster job on creating exciting new products for aquarists.

And I'm not trying to sound like an arrogant jerk here. I'm making some observations and sort of confirming my "thesis" about this stuff. And I think we're starting to deliver on our idea of innovative and hopefully exciting new products to go with our botanical-style aquairum obsession!

Since it's finally "time", let's look a bit more at the first releases of our new "NatureBase" range of substrates!

Now, first off, a bit of background.

I started playing with substrates a few years back, mainly because I couldn't find exactly what I was looking for on the market. This is not some indictment of the major substrate manufacturers out there...I LOVE most of them and use and happily recommend ones that I like.

That being said, I realized that the specialized world which we operate in embraces some different ideas, unusual aesthetics, and is fascinated by the function of the environments we strive to replicate. These are important distinctions between what we are doing in substrates at Tannin, and the rest of the aquarium hobby is doing.

Our NatureBase line is not intended to supersede or replace the more commonly available products out there as your "standard" aquarium substrate because: a) they're more expensive, b) they're not specifically "aesthetic enhancements", c) they are not intended to be planted aquarium substrates d) because of their composition, they'll add some turbidity and tint to the aquarium water, at least initially (not everyone could handle THAT!)

So, right there, those factors have significantly segmented our target market...I mean, we're not trying to be the aquarium world's "standard substrate", we're not marketing them just for the cool looks, and we can't emphasize enough that they will make your water a bit turbid when first submerged. Those factors alone will take us out of contention for large segments of the market!

This is important.

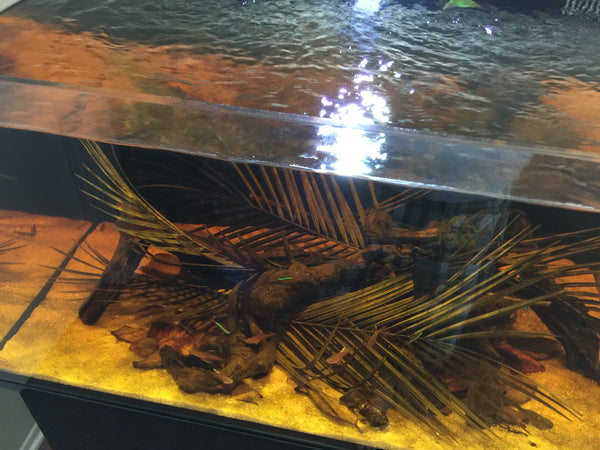

I mean, these are intended to be used in more natural, botanical-style/biotope-inspired aquariums. Our first two releases, "Igapo" and "Varzea", are specific to the creation odf a type of "cyclical" terrestrial/aquatic feature. They do exactly what I wanted them to do, and some of them are specifically intended for use in specialized set ups, like the "Urban Igapo" idea we've been talking about for a long time here, brackish water mangrove environments, etc.

Let's touch on the "aesthetic" part for a minute.

Most of our NatureBase substrates have a significant percentage of clays and sediments in their formulations. These materials have typically been something that aquarists have avoided, because they will cloud the water for a while, and often impart a bit of color. We also have some botanical components in a few of our substrates, because they are intended to be "terrestrial" substrates for a while before being flooded...and when this stuff is first wetted, some of it will float. And that means that you're going to have to net it out, or let your filter take it out. You simply won't have that "issue" with your typical bag of aquarium sand!

Remember, these are intended for a very specific purpose: To replicate the terrestrial soils which are seasonally inundated in the wild. As such, these products simply won't look or act like your typical aquarium substrate materials!

Scared yet? I hope not.

Why sediments and clays?

Well, for one thing, sediments are an integral part of the natural substrates in the habitats from which our fishes come. So, theyre integral to our line. In fact, I suppose you'd best classify NatureBase products as "sedimented substrates."

Many of our favorite habitats are forest floors and meadows which undergo periodic flooding cycles in the Amazon, which results in the creation of aquatic habitats for a remarkable diversity of fish species.

Depending on the type of water that flows from the surrounding rivers, the characteristics of the flooded areas may vary. Another important impact is the geology of the substrates over which the rivers pass. This results in differences in the physical-chemical properties of the water. In the Amazon, areas flooded by rivers of black or clear waters, with acid pH and low sediment load in addition to being nutritionally poor, are called “igapó."

The flooding often lasts for several weeks or even several months, and the plants and trees need special biochemical adaptations to be able to survive the lack of oxygen around their roots. During the inundation period, many of the forest trees drop their fruits into the water, where they are eaten by fish. As an interesting side note, ecologists have noted that some of these trees and plants are strongly dependent on the fishes to disperse their seeds through the forest, requiring that the seeds pass through the gut of a fish before it will germinate.

Crazy!

Forest floor soils in tropical areas are known by soil geologists as "oxisols", and have varying amounts of clay, sediments, minerals like quartz and silica, and various types of organic matter. So it makes sense that when flooded, these "ingredients" will have significant impact on the aquatic environment. This "recipe" is not only compositionally different than typical "off-the-shelf" aquarium sands and substrates- it looks and functions differently, too.

And that's where a lot of people will metaphorically "leave the room."

So, yeah, you'll have to make a mental shift to appreciate a different look and function. And many hobbyists simply can't handle that. We're being up front with this stuff, to ward off the, "I added NatureBase to my tank and it looks like a cloudy mess! This stuff is SHIT!" type of emails that inevitably come when people don't read up first before they purchase the stuff.

The igapo and varzea substrates are intended to be "terrestrial" for a period of time, to get the grasses and plants going, and then inundated. You DON'T RINSE THEM BEFORE USE! You CAN fill them with water right off the bat; however, you should be ready for some cloudy water for a week or more!

This is not unlike what occurs in the wild habitats...newly inundated forest floors have a lot of leaf litter, seed pods, etc., and will be quite turbid for some time. If you understand the context for which they are intended, and the habitats which they help to replicate, this is perfectly acceptable and logical...Of course, you need to make that "mental shift", right?

Although these substrates can grow both terrestrial and aquatic plants well, they were not intended to be generic planted tank substrate, specifically. We're not trying to compete with the many fantastic specialized planted aquarium substrates out there. This is not some "Tannin is coming for you!" B.S. Rather, these are modeled after relatively nutrient-poor soils, which will grow plants, but not as well as the fancy clay pellets and such that are intended specifically to grow aquatic plants.

Yeah, our Igapo and Varzea mixes can grow plants like grasses and marginals pretty well. You're just not going to be doing your next "Dutch-style" aquascape or "Iwagumi" with our products. And, because of their price, you simply aren't likely to do a 50 or 100 gallon tank with them!

Our Igapo and Varzea substrates mimic sandy acidic soils that have a low nutrient content. And, as you know, the color and acidity of the floodwater is due to the acidic organic humic substances (tannins) that dissolve into it. The acidity from the water translates into acidic soils, which makes sense, right?

Now, I admit, I am NOT a geologist, and I"m not expert in soil science. I know enough to realize that, in order to replicate the types of habitats I am fascinated with required different materials. If you ask me, "Will this fish do well with this materials?" or, "Can I grow "Cryptocoryne in this?", or "Does this make a good substrate for shrimp tanks?" I likely won't have a good answer. Sorry.

I'll be the first to tell you that, while I have experimented with many species of plants, averts, and fishes with these substrates, I can't tell you that every single fish or plant will like them. I'd be full of shit at best, and a total liar at the worst- neither which I'd want!

Rather, I can tell you that these are some of the most unusual materials I've seen for specialized aquariums, and that they are wide open for experimentation in various kinds of systems! And that's part of the key: These substrates, even though they've been used by myself, my staff, and some close friends for a while now, are really "experimental" in nature.

Because you can do all sorts of cool stuff with them. Hell, you can even mix them with commercial, off-the-shelf substrates to make cool, functionally aesthetic "custom" mixes of your own!

We want you to use leaves, botanicals, and other materials with these unique substrates. "Spike" them with our PNS bacterial inoculants, "Culture" and "Nurture", to really kick start your biome! They're intended to help foster the growth of beneficial bacteria, biofilms, fungal growth, and micro crustaceans, to help build up a functional, diverse benthic habitat in botanical-style aquariums. They will help form the literal "base" of your botanical-style aquarium system (hence the name of the product line, "NatureBase").

Even though I have a near-obsessive love for the flooded forest substrates, I'm equally as excited to share the upcoming NatureBase "Mangal" with you- it's our specialized brackish-water mangrove habitat substrate- one that represents the culmination of a 4-year journey of researching, sourcing, mixing, and testing! As far as we know, there has not been a dedicated brackish water substrate offered before in the hobby, and we think it's yet another element for our "Estuary" line that will help revitalize and elevate this unique and oft-neglected hobby sector! It'll be coming soon!

Regardless of how you use these new substrates, we hope that you understand the "why" part as much as you do the aesthetics that they bring.

And yeah, they are rather pricy, as compared to a typical bag of aquarium sand. I'd compare their pricing to the more "high-end" aquatic plant speciality substrates. These are literally hand-mixed substrates, with the components sourced from suppliers throughout the world.

These aren't some mass-produced, re-purposed construction material or something. Rather, they are well-thought-out, carefully compounded natural materials, mixed expressly for the purpose of using in botanical-style aquariums.

We went through a lot of iterations before arriving at our final versions!

The prices will come down ultimately, once we get a read on the demand. I promise we'll try to adjust.And we have like 6-7 different "flavors" that will come out. We're going to release them, at least initially, much liek a coffee roaster does- limited releases, with a few "standards" always available. At least, until we guage demand!

We use all of them extensively in our own tanks. We love the results that we're getting...

And we hope that you will, too!

We'll have much, much more to say about these cool substrates as we get them launched; more to come! So stay tuned for more! Lots of information already out terse, if you read back on this blog- and much more to come!

Stay creative. Stay studious. Stay curious. Stay adventurous...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

The little Tetra that can..A deeper dive.

One of the things I enjoy most in the aquarium hobby is studying the ecology of the natural habitats of our fishes. I've found over the years that you can find out so much about the fish by understanding a bit about where it comes from.

When it comes to characins, there are few more widely known and loved in the hobby than the Neon Tetra, Paracheirodon inessi. This little fish has been the "gateway drug" for generations of tropical fish hobbyists, providing a colorful, exotic look into Nature's magnificent creations.

Of course, there other members of the genus Paracheirodon which hobbyists have become enamored with, such as the diminutive, yet equally alluring P. simulans, the "Green Neon Tetra." Topping out at around 3/4" (about 2cm) in length, it's certainly deserving of the hobby label of "nano fish!"

You can keep these little guys in nice -sized aggregations..I wouldn't necessarily call them "schools", because, as our friend Ivan Mikolji beautifully observes, "In an aquarium P. simulans seem to be all over the place, each one going wherever it pleases and turning greener than when they are in the wild."

This cool little fish is one of my fave of what I call "Petit Tetras." Hailing from remote regions in the Upper Rio Negro and Orinoco regions of Brazil and Colombia, this fish is a real showstopper! According to ichthyologist Jacques Gery, the type locality of this fish is the Rio Jufaris, a small tributary of the Rio Negro in Amazonas State.

One of the rather cool highlights of this fish is that it is found exclusively in blackwater habitats. Specifically, they are known to occur in habitats called "Palm Swamps"( locally known as "campos") in the middle Rio Negro. These are pretty cool shallow water environments. Interestingly, P. simulans doesn't migrate out of these shallow water habitats ( also called "woody herbaceous campinas" by aquatic ecologists) like the Neon Tetra (P. axelrodi) does. It stays to these habitats for its entire lifespan.

These "campo" habitats are essentially large depressions which do not drain easily because of the elevated water table and the presence of a soil structure, created by our fave soil, hydromorphic podzol! "Hydromorphic" refers to s soil having characteristics that are developed when there is excess water all or part of the time.

(Image by G. Durigan)

So, if you really want to get hardcore in recreating this habitat, you'd use immersion-tolerant terrestrial plants, such as Spathanthus unilateralis, Everardia montana, Scleria microcarpa, and small patches of shrubs such as Macairea viscosa, Tococa sp. and Macrosamanea simabifoli. And grasses, like Trachypogon.

Of course, our fave palm, Mauritia flexuosa and its common companion, Bactris campestris round out the native vegetation. Now, the big question is, can you find any of these plants? Perhaps...More likely, you could find substitutes.

Just Google that shit! Tons to learn about those plants!

These habitats are typically choked with roots and plant parts, and the bottom is covered with leaves...This is right up our alley, right?

Of course, if you really want to be a "baller" and replicate the natural habitat of these fishes as accurately as possible, it helps to have some information to go on! So, here are the environmental parameters from these "campo" habitats based on a couple of studies I found:

The dissolved oxygen levels average around 2.1 mg/l, and a pH ranging from 4.7-4.3. KH values are typically less than 20mg/L, and the GH generally less than 10mg/L. The conductivity is pretty low. T

he water depth in these habitats, based on one study I encountered, ranged from as shallow as about 6 inches (15cm) to about 27 inches (67cm) on the deeper range. The average depth in the study was about 15" (38cm). This is pretty cool for us hobbyists, right? I mean, we can utilize all sorts of aquariums and accurately recreate the depth of the habitats which P. simulans comes from!

Now, as aquarists, we often hear that P. simulans needs fairly high water temperatures, and the field studies I found for this fish this confirm this.

Average daily minimum water temperature of P. simulans habitats in the middle Rio Negro was about 79.7 F (26.5 C) between September and February (the end of the rainy season and part of the dry season). The average daily maximum water temperature during the same period averaged about 81 degrees F (27.7 C). Temperatures as low as 76 degrees' (24.6 C) and as high as 95 degrees F (35.2 C) were tolerated by P. simulans with no mortality noted by the researchers.

Bottom line, you biotope purists? Keep the temperature between 79-81 degrees F (approx. 26 C-27C).

Researchers have postulated that a thermal tolerance to high water temperatures may have developed in P. simulans as these shallow "campos" became its only real aquatic habitat.

The fish preys upon that beloved catchall of "micro crustaceans" and insect larvae as its exclusive diet. Specifically, small aquatic annelids, such as larvae of Chironomidae (hey, that's the "Blood Worm!") which are also found among the substratum, the leaves and branches.

Now, if you're wondering what would be good foods to represent this fish's natural diet, you can't go wrong with stuff like Daphnia and other copepods. Small stuff makes the most sense, because of the small size of the fish and its mouthparts.

This fish would be a great candidate for an "Urban Igapo" style aquarium, in which rich soil, reminiscent of the podzols found in this habitat is use, along with terrestrial vegetation. You could do a pretty accurate representation of this habitat utilizing these techniques and substrates, and simply forgoing the wet/dry "seasonal cycles" in your management of the system.

There are a lot of possibilities here.

One of the most enjoyable and effective approaches I've taken to keeping this fish was a "leaf litter only" system (which we've written about extensively here. Not only did it provide many of the characteristics of the wild habitat (leaves, warm water temperatures, minimal water movement, and soft, acidic water).

I'm preparing for a second run at replicating this fish's habitat, this time with a different substrate and a "root tangle" approach using Melastoma Root and "Borneo Root". I am really looking forward to seeing if there are any behavioral differences with a more densely packed hardscape configuration, as opposed to the completely open "no scape" that the previous version offered.

Now, the pH issue is something we all have to think about and experiment with if we really want to go as accurately as possible.

I know of few hobbyists who have ventured into the "sub 5" range with pH, so that's a real interesting challenge and approach; not for the feint of heart. It can be done, it simply requires a greater understanding of water chemistry and the techniques and materials designed to get you there.

This is currently the realm of super-experienced, highly experimental hobbyists, who are perhaps trying to unlock secrets of very demanding fishes, such as Altum Angels and others, which are known to come from and thrive in pH levels below 5.0. And, to achieve and maintain such pH levels, we're learning that the careful administration of acids, and the application of other exotic and scary-sounding techniques is required.

And the management of low pH systems, with the additional benefit of humic substances provided by botanicals, is a real "frontier" in the hobby. Even in the greater context of the blackwater aquarium world, it's seen as such. It can be challenging. But it's not the frightening sideshow it once was.

I mean, it sounds a bit scary, right? What exactly is the challenge here, besides getting the water to your desired target pH?

Understanding water quality management and the way in which denitrification occurs in closed systems in very low pH is challenging. On the surface, it seems really scary and daunting. I can't help but believe that- like so many things in the aquarium hobby-it's more of a function of the fact that we haven't done much with this in the past, and we simply don't have a "path" to follow just yet. We need to understand a different class of organisms which "run the cycle" in this environment, and how to manage them.

I do know that "Culture", our Purple Non Sulphur bacteria innoculant (a colony of Rhodopseudomonas palustris) is perfect for the management of the nitrogen cycle in low pH aquairums, even competing with Archaens in this environment. Real "extremophiles" which can help with part of the equation here!

Pushing the limits a bit...trying different techniques, enriched by our understanding of the wild habitats of our fishes. Helping the hobby advance. Is't this a delicious challenge?

This is one of the reasons why I have had a near-obsession with attempting to recreate, to some extent, as many of the physical/environmental characteristics of their wild habitats as possible for the fishes under my care. All the while, realizing that, although they will be residing in a closed system with many physio-chemical characteristics similar to what they have evolved to live under, it's not a perfect replication, much though I might want it to be, and being of the opinion that replicating "some"of these characteristics is likely better than replicating "none" of them, I say "Go for it!"

An arrogant assumption on my part, I suppose. I mean, like every one of you, I'm fully responsible for the animals which I keep. And I take a certain degree of pride in that. I want the best for them.

That being said, I'm personally not in that mindset of having to be absolutely "hardcore" about being 100% accurate biotopically, in terms of making sure that every leaf, every twig, every botanical is from the specific habitat of the fishes which I keep. I do respect aquarists who do, however.

But that's not me. Rather, I place the emphasis on providing a reasonably realistic, "functionally aesthetic" representation of the habitat form which they come, with aquascaping materials, layout, and environmental parameters configured to match, as close as possible to the parameters in the wild. It's not a perfect science. It's a challenge sometimes, too.

A big challenge- and a fun one- from such a little fish! The rewards are many for those who meet the challenge.

Stay resourceful. Stay creative. Stay studious. Stay inspired. Stay diligent.

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Life with botanicals...

There is something very pure and evocative-even a bit "uncomfortable" about utilizing botanical materials in the aquarium. Selecting, preparing, and utilizing them is more than just a practice- it's an experience. A journey.One which we can all take- and all benefit from.

Right along with our fishes, of course!

The energy and creativity that you bring with you on the journey tends to become amplified during the experience. We don’t want everyone walking away feeling the same thing, quite the opposite actually.

That uniqueness is a large part of the experience.

The experience is largely about discovery. And today's piece is a bit about some of the interesting discoveries- expectations, and revelations that we've learned along the way during our "life with botanicals!"

Our aquariums evolve, as do the materials within them.

If we think of an aquarium as we do a natural aquatic ecosystem, it's certainly realistic to assume that some of the materials in the ecosystem will change, re-distribute, or completely decompose over time.

Botanicals are not "forever" aquascaping materials. We consider them ephemeral in nature. They will soften, break down, and otherwise decompose over time. Some materials, like leaves- particularly Catappa and Guava, will break down more rapidly than others, and if you're like our friend Jeff Senske of Aquaiuim Design Group, and like the look of intact leaves versus partially decomposed ones, you'll want to replace them more frequently; typically on the order of every three weeks or so, in order to have more-or-less "intact" leaves in your tank.

On the other hand, if you're like me, and enjoy the more natural look that occurs as the leaves break down, just keep 'em in. You may need to remove some materials if you find fungal growth, biofilm, or other growth unsightly or otherwise untenable. However, if you've made that "mental shift" and can tolerate the stuff, just let them be and enjoy!

Botanicals like the really hard seed pods (Sterculia Pods", "Cariniana Pods", "Afzelia Pods"), etc., can last for many, many months, and generally will soften on their interiors long before any decomposition occurs on the exterior "shell" of he botanical. In fact, they'll typically recruit biofilms, which almost seem to serve as a sort of "protective cover" that preserves them.

Often times, fishes like Plecos, Otocinculus catfish, loaches, Headstanders, and bottom-dwelling fishes will rasp or pick at the decomposing botanicals, which further speeds up the process. Others, like Caridina shrimp, Apistos, characins, and others, will pick at biofilms covering the interior and exterior of various botanicals, as well as at the microfauna which live among them, just as they do in Nature.

We receive a lot of questions about which botanicals will "tint the water the darkest" or whatever. Cool questions. Well, here's the deal: Virtually all botanical materials will impact the color of the water. You'll find, as we have, that different materials will impart different colors into the water. It will typically be clear, but with a golden, brownish, or reddish tint.

The degree of tint imparted will be determined by various factors, such as how much of the materials you use in your tank, how long they were boiled and soaked during the preparation process, and how much water movement is in your system.However, rest assured, almost any botanical materials you submerge in your tank will impart some color to the water.

Unfortunately, since these are natural materials, there is no set "X number of leaves/pods per ___ gallons of aquarium capacity", and you'll have to use your judgement as to how much is too much! It's as much of an "art" as it is a "science!"

Now, If you really dislike the "tint", but love the look of the botanicals you can mitigate some of this by employing a lmuch onger "post-boil" soaking period- like over a week. Keep changing the water in your soaking container daily, which will help eliminate some of the accumulating organics, as well as to help you to determine the length of time that you need to keep soaking the botanicals to minimize the tint.

Of course, it's far easier to simply employ chemical filtration media, such as activated carbon, and/or synthetic adsorbents such as Seachem Purigen, to help eliminate a good portion of the excess discoloration within the display aquarium where the botanicals will ultimately "reside."

Another interesting phenomenon about "living with your botanicals" is that they will "redistribute" throughout the aquarium. They're being moved around by both current and the activities of fishes, as well as during our maintenance activities, etc. This is, not surprisingly, very similar to what occurs in Nature, where various events carry materials like seed pods, branches, leaves, etc. to various locales within a given body of water. In our opinion, this movement of materials, along with the natural and "assisted" decomposition that occurs, will contribute to a surprisingly dynamic environment!

Your aquarium water may appear turbid at various times. We are pretty comfortable with this idea; however, some of you may not be. As bacteria act to break down botanical materials, they may impart a bit of "cloudiness" into the the water. Also, materials such as lignin and good old terrestrial soils/silt find their way into our tanks at times.

Some of these inputs, such as soils- are intentional! Others are the unintended by-product of the materials we use, The look is definitely different than what we as aquarists have been indoctrinated to accept as "normal." One of my good friends, and a botanical-style aquarium freak, calls this phenomenon "flavor"- and we see it as an ultimate expression of a truly natural-looking aquarium.

Yeah, the water itself becomes part of the attraction. The color, the "texture", and the clarity of the water are as engrossing and fascinating as the materials which affect it.

Need a bit more convincing to embrace the charm of the water itself in botanical-style aquariums?

Simply look at a natural underwater habitat, such as an igapo or flooded varzea grassland, and see for yourself the allure of these dynamic habitats, and how they're ripe for replication in the aquarium. You'll understand how the terrestrial materials impact the now aquatic environment- fundamental to the philosophy of the botanical-style aquarium.

Speaking of the impact of terrestrial materials on the aquatic habitat- remember, too, that just like in Nature, if new botanicals are added into the aquarium as others break down, you'll have more-or-less continuous influx of materials to help provide enrichment to the aquarium environment. This type of "renewal" creates a very dynamic, ever-changing physical environment, while helping keep water chemistry changes to a minimum.

The fishes in your system may ultimately display many interesting behaviors, such as foraging activities, territorial defense, and even spawning, as a result of this regular influx of "fresh" aquatic botanicals. You could even get pretty creative, and attempt to replicate seasonal "wet" and "dry" times by adding new materials at specified times throughout the year...The possibilities here are as diverse and interesting as the range of materials that we have to play with!

It's all a part of your "life with botanicals"- an ever-changing, always interesting dynamic that can impact your fishes in so many beneficial ways.

Stay dedicated. Stay excited. Stay engaged. Stay resourceful...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

A bit of a problem...And how we're doing our part to fix it.

The aquarium hobby is certainly one of those endeavors which pulls in all sorts of people, with widely diverse experience, interests, and abilities. And, because of this "wide net" that the hobby casts, we have a huge assortment of possibilities for success.

If you've been in the hobby for some time, as I have (like, all my life), you start noticing trends, or more specifically, changes in practices, attitudes, and interest levels. I've noticed a troubling one lately.

In a world where people are supposedly not able to retain more than 280 characters of information, and where there is a apparently a "hack" for pretty much everything, I wonder if have we simply have lost the ability to absorb information on things that are not considered “relevant” to our immediate goal. I say this not in a sarcastic manner, but in a thoughtful, measured one. I'm baffled by hobbyists who want to try something new and simply do next to no research or self-education prior to trying it.

Like, WTF?

When you read some of the posts on Facebook or other sites, where a hobbyist asks a question which makes it obvious that they failed to grasp even the most fundamental aspects of their "area of interest", yet jumped in head-first into this "new thing", it just makes you wonder! I mean, if the immediate goal is to have "a great looking tank", it seems to me that some hobbyists apparently don’t want to take the time to learn the groundwork that it takes to get there and to sustain the system on a long-term basis. I suppose that it’s far more interesting- and apparently, immediately gratifying- for some hobbyists to learn about what gadgets or products can get us where we want, and what fishes are available to complete the project quickly.

This is a bit of a problem.

We perpetuate this by well- dumbing everything down. We feature the superficial aspects of the hobby- how cool the tanks look, the overly-stylized images of aquascaping contest winners, etc., while failing to get people to grasp the basics. We often see these threads that emphasize the equipment or various brands of stuff used, complete with all of the appropriate hashtags for discoverability.

I mean, I get that part. Society has shifted, and discovering content is important. It's just sort of interesting to me to see this elevated in importance over stuff like, oh- I don't know- a discussion of how the damn system works, what the inspiration for it was, etc., etc.

Just an emphasis on too much of the "finished product" and a complete absence of information about how to get there. We need to address this.

Then there are those “build threads” you see on various forums (it's especially "rampant" in the reef side of the hobby). In many of these threads, you’ll see a detailed run down of the equipment, shots of the assembly, the “solutions” to the problems encountered along the way (usually more expensive equipment purchases). You’ll see pics of the finished tanks…But not much of the more "interesting" phases of their existence.

All very interesting and helpful, but the “weirdness” starts when, in the middle of the threads, you’ll see the “builder” asking about why he’s experiencing a massive algae outbreak, or why all of the Apistogramma, plants or coral frags he just added are dying in this brand new, state-of-the-art tank. Questions and ensuing discussions that are so "Aquarium 101" that they make you wonder why this ill-informed, yet apparently well-healed individual went off on a 5-figure “joyride”, building a dream tank with an apparent complete ignorance of many of the hobby fundamentals. And sadly, the hobbyist sometimes just...quits.

I’m often dumbfounded at the incredible lack of hobby basics many of these people show. Just because you’re a great DIY guy, and have disposable income to buy everything you see advertised on line for your 400-gallon tank, it doesn’t make you a knowledgeable or experienced aquarist. It just doesn’t.

Okay, I’m sounding very cynical. And perhaps I am. But the evidence is out there in abundance…and it’s kind of discouraging at times.

Look, I’m not trying to be the self-appointed "guardian of the hobby." I’m not calling us out. I’m simply asking for us to look at this stuff realistically, however. To question our habits. No one has a right to tell anyone that what they are doing is not the right way, but we do have to instill upon the newbie the importance of understanding the basics.

Like many other vendors, I offer products to people and don’t educate them on every single aspect of aquatic husbandry. I spend scant little time discussing the most basic aspects of the aquarium hobby. I have to make the assumption that an aquarists jumping in to the botanical-style aquarium game at least has some prior hobby experience and a grasp of the fundamentals. Perhaps it's too much of an assumption?

Personally, I'm not interested in re-hashing "Aquarium Keeping 101"- there are plenty of amazing hobby resources out there for that stuff. I prefer to share and disseminate information as it pertains to our unique hobby speciality. Quite frankly, I think we've done a pretty good job of it over the past 5 years or so, too.

Educating and informing is every bit as important as "selling" and inspiring fellow hobbyists on this stuff. When we started Tannin, I knew that we were heading onto an area of the hobby that was replete with speculation, myths, and downright misinformation- if you could find anything about it out there at all. So, we started out from day one, sharing all sorts of information about our little hobby speciality.

It’s hard to do that. I do write lots of blogs and articles, and lecture all over the world, so I know I’m doing something to reach some people…but not enough. I need to do better. I probably need to write more about basic sort of stuff than I do about whatever the heck is on my mind? Dunno. I do know that we all need to tell hobbyists like it is, without sugar coating everything. There WILL be decomposition. There WILL be biofilms! Shit like that. We have to keep talking about all aspects of this stuff.

Sometimes, it's controversial. Other times, it's speculative. Sometimes, we simply don't have the answers- we just have the observations based upon our experience, so we share those. We hypothesize when we feel comfortable. We've grown along with our community, sharing our ideas and experiences in as unfiltered a manner as possible. Our ideas and information has become more sophisticated and useful as we've evolved, and as global feedback has come in.

Thanks to YOU- our community, we've all created a movement in the hobby.

I remember when I started Tannin Aquatics, I was determined to share my passion for using all sorts of botanicals and leaves to create what I feel are a profoundly different type of "natural aquarium" than the sanitized, polished, aquarium-as-a-canvas model that's been preferred to us over the past decade or so as the shit. I knew that there would be aquarists who didn't "get it"- aquarists who would focus on the perceived "negatives", like decomposition, issues, maintenance, having to prepare everything before use, etc. Stuff that is actually the important, positive fundamental "cannon" of what we do.

I KNEW that there would be people who might kill their fishes by adding lots of botanicals to their established systems without reading and following the instructions concerning preparation, cadence, and what to expect. I knew there would be people who would criticize the idea, "edit" the processes or recommended "best practices", talk negatively about the approach and generally scoff and downplay what they didn't know, understand, or do.

It's human nature whenever you give people something a bit different to play with...They want to go from 0-100 in like one day. And I knew that some of these people would go out on social media and attempt to trash the whole idea after they failed. This, despite all of our instructions, information, and pleas to follow the guidelines we suggested.

That's how it goes in the hobby sometimes. When you're trying new things, some people are really eager to get into them...but not all are eager to "look before they leap." That's why reef aquariums seem to be so challenging...even mysterious- to some people. It seems like the rewards are so great- so cool...they want in. Now. And there are all of these cool gadgets and chemicals and stuff that make it super easy!

Regrettably, many manufacturers and vendors over the years have fed this narrative by over-hyping their products and conveniently glossing over the potential pitfalls of using them.

We don't. We share it all.

I guess this is why I get pissed off as fuck when I see someone out there in forums or wherever jump to some speculative "conclusion" without the obvious firsthand experience about what we do and try to heap us into the "fluff marketing/PR" category of brands which make generic, seemingly spectacular claims about their products and ideas.

WE DON'T. We never have. We never will. Search all 600 or so of our blogs, the dozen or so hobby magazine articles we've written on this idea, and try to find a word of marketing hyperbole or outrageous claims about our products or this idea of botanical-style aquariums. You won't. It's not in our "DNA."

Now, of course, it goes with the territory- the skepticism, constructive criticisms, and outright accusations. We have to swallow our pride sometimes and just listen, and decide if we're going to respond in some direct way...or to just keep our heads down and do what we do. I guess this very blog is another "marker" we're laying down to counteract that sort of thing.

It's a continuous process that we as aquarium hobby proponents and brands need to do. We need to address all of this stuff. Good and bad.

Because NOT sharing the potential negatives is a bad thing. I'm super-proud that we've consistently elevated realistic discussions about unpopular topics related to our hobby sector. Yeah, we literally have blog and podcast titles like, "How to Avoid Screwing Up Your Tank and Killing all of Your Fishes with Botanicals" , or "There Will be Decomposition", or "Celebrating The Slimy Stuff."

We continuously use all of our products- often deliberately, in ways we'd never, ever recommend you try. We've literally set up systems to see how far we can push it, and to see what kind of consequences could happen from misusing them.

We're going to keep doing that. Because, when you're pushing unusual and exotic ideas, many of which have no precedent or "settled science" behind them, you need to continuously document experiences and share discoveries- the good, the bad- and the ugly. It's how we will continue to do our share to advance this hobby speciality and push beyond what's currently accepted.

This is my call to all of the members of our global community- Hobbyists, authors, vendors, manufacturers:

Go beyond the superficial, "Insta-ready" splash, and have thoughtful, realistic, and frank discussions with your fellow hobbyists about all aspects of what we do. Stress fundamentals, the process...the journey.

We owe it to the hobby, our fellow fish geeks...and most important- the plants and animals that we love so much.

Stay honest. Stay strong. Stay bold. Stay thoughtful...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

"The Pasta Sauce Analogy" and Aquatic Substrates...

We talk about soem weird things around here, don't we?

I admit, we have some rather "unorthodox" approaches to stuff. However, I think. a lot of what we are doing here is becoming more "mainstream" all the time..Or, at least, a lot of this stuff is getting more consideration than it has in the past!

Back in 2015, we talked about the idea of "substrate enrichment" in botanical-style aquariums. In other words, adding botanical materials to the more traditional substrates of sand, etc. Now, at first glance, this idea seems rather "normal" in many respects. I mean, planted aquarium enthusiasts have been adding various supplements to their substrates for decades, with the intention of providing beneficial trace elements and nutrients for plants.

Yet, we're talking about enriching the substrate for the purpose of providing tannins, humic substances, and nutrition- for microbial and crustacean life forms that could reside in the substrate. Not primarily for aquatic plants.

When you examine the substrates found in many natural habitats, they often appear to be a mixture of a variety of materials, including sands, sediments, muds, clays, and botanical materials. These materials not only look different- they function in unique ways, not only influencing the water chemistry, but the biology and ecology of the aquatic systems as well.

Now, in Nature, there are numerous factors which contribute to the composition of substrates in wild aquatic habitats, including geology, the flow velocities of the body of water, the surrounding topography, the seasonal variations in water level (ie; inundation/dessication cycles), and accumulation of materials from the surrounding terrestrial environment.

Nature utilizes almost everything at her disposal in order to create and maintain aquatic ecosystems. So, why do we as hobbyists, who want to create the most realistic approximations of wild habitats possible, just sort of "mail it in" when it comes to substrate? I mean, just open a bag of _____________ sand or whatever, and call it a day and move on to he more "exciting" parts of our tank?

I think we just rely on the commercially available stuff and that's that.

Now, in defense of the manufacturers of sands and gravels for aquarium use- I love what they do, and what they have available. These items are of generally excellent quality, provide a wide range of choices for a variety of applications, and are readily available.

However, IMHO, they are a great "starting point" for creating more dynamic substrates for our aquariums. Kind of like tomato puree is to pasta sauce...a beginning! Sure, you can use just the puree and enjoy it as your sauce, but isn't it always better to add a bit of "this and that" and build on the "base"to create something better?

Totally.

(Damn, it's 7:00AM here in L.A., and now I'm craving Penne...WTF?)

That, in a nutshell, is my theory of aquarium substrates.

We can do a bit better.

We will do better with the imminent first release of our "NatureBase" substrate line!

Okay, back to the wild for a second...Let's look at how natural substrates form.

Now, in many of the tropical regions we admire, the basic substrate is often referred to simply as "fine, white sand" in most scientific papers- typically, but not necessarily a silica of some sort. And of course, other locations have slightly larger grain sizes of other pulverized stones and such. Still others are comprised of sediments which wash down from higher elevations during seasonal rains.

Deep rivers will typically have different substrate compositions than say, marginal streams or floodplain lakes, or even flooded forests. In the Amazon region, a huge percentage of the sediment and materials which comprise the substrates are from the Andes mountains, where they are transported down into the lower elevations by water flow.

This has huge foundational impact on the chemistry of the waters in the region. This process builds the fertile floodplain soils along Andean tributaries and the main stem of The Amazon.

There is a whole science around aquatic substrates and their morphology, formation, and accumulation- I don't pretend to know an iota about it other than skimming Marine biology/hydrology books and papers from time to time.

However, merely exploring the information available on the tropical aquatic habitats we love so much- even just looking long and hard at some good underwater pics of them- can give us some good ideas!

First off, in some areas- particularly streams which run through rain forests and such, the substrates are often simply a terrestrial soil of some sort. A finer, darker-colored sediment or soil is not uncommon. The water chemistry- indeed, "blackwater" itself, is based on the ionic, mineral, and physical concentrations of terrestrial materials that are dissolved into the water. And the degree to which these materials disperse into the aquatic environments vary based on water velocities, time of year, and other factors, as touched on above.

Meandering lowland rivers maintain their sediment loads by continually re-suspending and depositing materials within their channels- a key point when we consider how these materials remain in the aquatic ecosystems.

Okay, I could go on and on with my amateur, highly un-scientific review of substrates in Amazonia and elsewhere, but you get the point!

There is more to the substrate materials found in Nature than just "sand." That's the biggest takeaway here! So, as hobbyists, we have more options and inspiration to to draw on to create more compelling functional substrates in our aquariums!

What that means to us is (taking into account the "pasta sauce analogy", of course) is that we should consider mixing other materials into our basic aquarium sands. For example, you could mix aquatic plant soils into you sand. You could experiment with materials such as clay, or other mineral/plant-based components of varying particle sizes.

Obviously, your substrate will look a lot different than the "typical" aquarium substrate when you start mixing materials. Your overall aquarium will, too. And that's a good thing, IMHO. I played around with this a lot in my office brackish water Mangrove aquarium, where the substrate played an integral functional role in the aquarium, as well as an aesthetic one...

If you start with one of our "sedimented" substrates, which already is intended to mimic the look and characteristics of natural aquatic substrates, you're already a little ahead of the curve. However, you can apply this idea to just about any type of aquarium substrate,

A combination of finely crushed leaves, bits of botanicals, small twigs, etc. can form the basis for a more "biologically active" and even productive substrate. As these materials break down, they are colonized by fungi and biofilms, and impart tannins, lignin, and other sources of carbon into the water to fuel a variety of microbial growth.

And of course, larger crustaceans and even fishes will consume the organisms which live in this "matrix", as well as possibly consuming some of the detritus from the decomposing leaves themselves.

Its a very different looking- and functioning- substrate, for sure. At the risk of sounding too commercial here, suffice it to say, we have a whole damn section on our site called "Substrate Additives" for the very purpose of facilitating such geeky experiments!

This stuff is THAT interesting to me...It's wide open for lots of experimentations, evolutions, and evenbreakthroughs.

Look to Nature, again.

Now, of course, you're running an aquarium, not managing a stretch of open wild river or stream. Duh. The dynamics of closed systems are a bit different! However, the forces of Nature and Her "laws" will always apply. It's up to us as aquarists to make the effort to understand them and work with them, instead of against them.

You could create a bit of a mess if you're not too fastidious about the overall husbandry. You obviously can't overstock, overfeed, etc. Basic aquarium husbandry stuff. Yeah, it's entirely possible to create a smelly, anaerobic pile of shit on the bottom of your aquarium if you're lazy!

I've maintained these types of substrates over very long periods of time without any issues. Period. Sure, there is always the remote chance that you may nuke your entire fucking tank, of course, if you're not careful- but I think it highly unlikely if you follow basic tenants of aquarium husbandry, otherwise! I've played with this idea for almost 16 years without a single issue.

"Gee Scott- thanks! Another way to kill my fishes, courtesy of your weird ideas!"

Okay, it's not that weird. And really, not that dangerous.

I just don't want some flat-out beginner, heading home from the LFS with a brand new nano-sized aquarium, complete with a "Sponge Bob" bubbling ornament, purple gravel, and 20 Neon Tetras to go online, find our site, see some pics, and dump 12 ounces of crushed leaves, 3 ounces of "Substrate Fino", and a bag of oak twigs into the gravel and expect some sort of miracles, you know?

You need to move forward with caution. However, you needn't be afraid. You simply need to observe very carefully, have reasonable expectations about what will happen, and you have to accept an entirely different look that accompanies the function.

Typically, when "enriching" your substrate with botanical materials, you'll see an initial "surge" of the aforementioned biofilms and such, ultimately subsiding to a sort of "baseline" of a little bit of stuff in and among the substrate. WARNING: It will NEVER look "pristine" or "competition sterile." Get that idea out of your head immediately. That's only one "standard" for assessing what a "healthy" substrate is.

Your system WILL look much, MUCH more natural, dynamic, and altogether unique. Consider once again that, when you're incorporate decomposing botanical materials, not only are you adding to the biological load of the aquarium, you will be fostering the growth of beneficial microorganisms, like bacteria...Could this lead to enhanced denitrification or even "fermentation" in deeper substrates, which enhance the overall water quality? And what about it's potential as a "mulch" of sorts for aquatic plant growth?

It's interesting, exciting, and potentially game-changing to utilize varying materials to "enrich" your substrate in a variety of ways. And it's all big, fun, incredible experiment. It all starts with a few basic materials...and can become as rich and diverse as you care to make it.

Pasta sauce, indeed.

Stay creative. Stay excited. Stay curious. Stay diligent. Stay thoughtful...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Approaches, observations, management...and algae!

We focus a whole lot about the practices involved in setting up botanical-style aquariums, the nuances in their evolution, and the "best practices" involved in managing them. However one of the things that we're overdue for another discussion on is the long term expectations of what happens in such a system.

Specifically, what happens in an aquarium where we have this enormous amount of botanical materials breaking down?

First off, let's clarify some stuff. Despite the seemingly laissez-faire style of "a whole lotta stuff" accumulating in the aquarium, it's not just, "Drop in leaves and forget." There is a fair amount of technique there. Technique, married with long-utilized common-sense aquarium husbandry practices.

I am a big believer in stability, and deploying patience, using time-honored nutrient control/export techniques, and applying a healthy dose of observation and common sense all contribute to the ultimate stability and success of our blackwater/botanical-style aquariums- just as they would to any other type of system.

One of the things that we all experience with these types of systems is an initial burst of tint-producing tannins, which likely will provide a significant amount of "visible tint" to the water. If you're not using activated carbon or some other filtration media, tis tint will be more pronounced and likely last longer than if you're actively removing it with these materials!

You might also experience a bit of initial cloudiness...this could either be physical dust or other materials released from the tissues botanicals, or even a burst of bacteria/microorganisms. Not really sure why, but it usually passes quickly with minimal, if any intervention on your part. Oh, and not everyone experiences this...often this is a phenomenon which seems to happen in brand new tanks...so it might not even be directly attributable to the presence of the botanicals (well, at least not 100%). Could be the sand, or other dust/dirt from the other hardscape materials or the tank itself.

And of course, as we've discussed, it's perfectly normal for the water in botanical-style aquariums to have a little bit of "texture" to it- a sort of normal by-product of the breakdown of the materials we use.

While we're on the subject of new tanks, one of the things I've noticed about my botanical-style/blackwater aquariums is that they "cycle" very quickly. Like, often in less than a week. Why? I think it's got something to do with a large influx of botanical materials in a new system. The same factors that would endanger an established system might simply contribute to a rapid growth of bacteria.

Interestingly, over the years, I've also found that nitrate accumulation tends to be almost nonexistent in my botanical-style aquairums. Now, I don't know if that's something which you've noticed, too? I simply have never seen a nitrate accumulation more than 0.2mg/L!

Despite what I hypothesized would happen in my early years of playing with this style of aquarium, when I really got into blackwater, botanical-style aquariums, I found that they almost always produce little to no detectible nitrate, despite utilizing a lot of botanical material within the tank that was breaking down. I would have thought, at least on the surface, that there would be some detectible elevated nitrate. Now, this is interesting, but I'm not the only one who has reported this. Many of you have.

My hypothesis is that, yes, the material is breaking down, and contributing to the biological "load" of the system- but with an abundance of microorganisms living in, on, and among the botanical materials in the aquarium, and with regular frequent water changes, there is a very efficient processing of nutrients occurring.

This is purely speculation on my part, but I think it's as good a guess as any, based on the repeated similar results I've achieved in pretty much every single blackwater/botanical-style aquarium I've kept for the last 7 or 8 years!

I'm sure that a more sophisticated explanation, revolving around the presence of "on- board carbon sources" and other biological processes is the reason. I think that we're sort of looking at a freshwater equivalent of a reef aquarium in many respects, where, instead of "live rock", a lot of the microbial population and biological processes occur within and upon the surfaces of the botanicals themselves.

Almost like "biopellets" in a reef tank, perhaps the botanicals are not only a carbon source for beneficial bacteria- they're also a sort of biological filtration "substrate" for them to colonize on. Again, speculative, and needing some more rigorous scientific investigation to verify one way or another, but it's been my "working hypothesis" for several years.

In my opinion, once they get through the initial startup phase, blackwater/botanical-style systems seem to run incredibly smoothly and in a very stable manner. If you adhere to a regular, yet simple maintenance schedule, obey the long-established common-sense "rules" of aquarium husbandry, and don't go crazy with radical overstocking or trying to speed up things too much by dumping tons of botanicals into your established, stable tank in a brief span of time, these systems run almost predictably, IMHO.

And speaking of "maintenance"- I'll concede that one of the "bummers" of botanical-style aquarium keeping is that you will likely have to clean/replace prefilters, micron socks, and filter pads more frequently. Just like in Nature, as the botanicals (leaves, in particular) begin to break down, you'll see some of the material suspended in the water column from time to time, and the bits and pieces which get pulled into your filter will definitely slow down the flow over time.

The best solution, IMHO, is to simply change prefilters frequently and clean pumps/powerheads regularly as part of your weekly maintenance regimen.

Remember, you're dealing with a tank filled with decomposing botanical materials. Good overall husbandry is necessary to keep your tank stable and healthy- and that includes regular water exchanges. At the very least, you'll likely be cleaning and/or replacing pre filter media as part of your routine, and that's typically a weekly-to bi-weekly thing.

Let's talk about the most dreaded of all aquarium occurrences: The appearance of microalgae.

While it would be intellectually dishonest (and just plain untrue) for me to assert that blackwater/botanical aquariums aren't susceptible to algae outbreaks, it is sort of remarkable that we simply don't have massive algae issues in these types of aquarium on a regular basis. I have to admit, that I have never had one of those nightmare algal blooms in a blackwater aquarium...and although it sounds like tannins or some other "substances" in the blackwater would be the obvious "x factor", I'll tell you that I've never had an outbreak in a clearwater aquarium, either.

So, from personal standpoint, I can shout, "My blackwater tanks don't have algae issues!" On the other had, none of my other tanks have had them, either. And I'll wager that neither have many of yours, as well!

Shit. Not helpful, huh?

I read a study from the University of Georgia, which tested the idea of algae growth in blackwater streams, to determine if the limiting factor was chemical (nutrient) or light driven...and lo and behold, the study concluded that it wasn't necessarily some magic stuff in tannins and blackwater, as much as it was light limitation!

Yes, you heard me correctly.

Light-limiting effects of the blackwater itself were discovered to inhibit algal growth in coastal plain streams. As light penetrates the water, high DOC concentrations and suspended solids can scatter and absorb light, impacting algal growth significantly.

Okay, sounds like a bummer if you want to believe blackwater is "magic", but the study also concluded that blackwater systems were somewhat nutrient-limited, which also affected the growth of algae- although this was not concluded to be the primary factor which inhibited algae growth. In fact, another study I perused about the Rio Negro concluded that it was found that there is a relatively small difference in "respiration rates" between "whitewater" and "blackwater" rivers, and that the presumption that blackwater systems are more "sterile" is sort of overstated.

Interestingly, the study also concluded that higher incidence of algal growth occurred in areas in Amazonia where water movement was minimal, or even stagnant, suggesting that, all things being equal, light limitation and water movement are possibly more significant than just higher nutrient concentrations alone!

And that makes sense, if you consider the long-held belief within the aquarium hobby that most plants don't do well in blackwater aquariums "because they don't get enough light!"

Yikes!

So the long-held aquarium attitude about blackwater having some algal-inhibiting properties is really based on the fact that it's...darker? I mean, every blackwater tank I have ever owned does have some algae present. Although, being a reef guy at heart, every aquarium I own has good water movement. I know that in leaf-litter-dominated aquariums, which I love, I still keep a good amount of flow going.

This is interesting, because you'd think a tank dominated by decomposing leaf litter would be a freaking "algae farm", right? And yet, I've experienced no more occurrence of algae in the leaf litter tanks than I have in other setups. On the other hand, regardless of what type of system I work with, I'm fanatical about husbandry and nutrient control/export...obviously, another key factor.

Interesting stuff, huh? And since a lot of blackwater/botanical-style tanks are hardscape, with little or no plants, the lighting we are employing is strictly aesthetic, right? So, you're not hitting a tank with decomposing pods and no plants with 14 hours of full spectrum light...Personally, I use LED, and I keep my intensity levels very low (as low as 15% on the low end to 20%-25% on the higher end). Aesthetics.

Well, that certainly can be part of the reason why this tank magically has essentially little to no nuisance algae, huh? We pin both the praise and the blame for algae on the wrong suspects, I think!

Man, this deserves more study...a lot of it.

Let's think about algae in the aquarium to begin with...No, not the boring old "This is how algae problems happen in our aquariums..." bullshit lecture that you've read on every website known to man since the internet sprung to life. You can find that stuff everywhere. Rather, let's think about how we, as a group, mentally are opposed to the stuff in our tanks.

I mean, yeah, I know of no one that really enjoys a tank smothered in algae. It looks like shit, and is a "trophy" for incompetence, in the eyes of most aquarists. In fact, I remember reading once that more people quite the aquarium hobby over algae problems than almost anything else.

Yuck!

Well, sure- algae problems caused by obvious lapses in care or attention to normal maintenance, like overfeeding, lack of water changes, gross overstocking, etc. are signs of...incompetence. The occasional algae outbreaks that many hobbyists suffer through have all sorts of other potential causes, and can often be traced to a combination of small things that went unchecked, and are typically controlled in a relatively short amount of time once the causative factors are identified.

Yet, as a group, us hobbyists freak out about algae in our tanks. I can show you a hundred pics of algae and biofilm covered logs in the Amazon and the Rio Negro and say, "See it happens here too! Natural!" and the typical hobbyist will still be rendered speechless with horror at the thought of the shit appearing in her tank!

And I can't even tell you what it would do to one of those "natural aquascaping" contest freaks or judges! People might die. You could be charged as an accessory to murder! Seriously.

So, not everyone gets it. Just like brown water.

Algae is the foundation of life, blah, blah, blah. Yet, it's also the foundation for a "cottage industry" of devices, chemicals, and treatment regimens designed to eradicate it.

Regardless of what approach we take, natural processes that have evolved over the eons will continue to occur in your aquarium. You can fight them, attempt to stave them off with elaborate "countermeasures" and labor...or you can embrace them and learn how to moderate and live with them via understanding the processes by which they appear.

And the algae?

It'll always be there. It's just a matter of how "prominent" we allow it to be.

Back to the water exchanges, and what you should/could do during these sessions.

During my water exchanges, I'm merely siphoning water from down low in the water column. I typically do not remove the broken-down leaf and botanical material, unless it's becoming a bit of a nuisance, blowing into places I don't want it. I don't remove leaves and botanicals as they break down. I'm a sort of "leave 'em alone as they decompose" kind of guy.

And I'm not going to go into all the nuances of replacement water preparation, etc. You have your ways and they work for you. It's not really "rocket science" or anything, but everyone has their own techniques. The one "constant" is to perform regular water exchanges in your botanical-style aquariums. Just do them.

Like almost any aquarium, botanical-style blackwater/brackish aquariums require attention, management, and maintenance. Water exchanges are important, like they are in any aquarium, providing the same benefits. Water testing is important, particularly in situations where you're starting out with soft, acidic water, as the impact of botanicals is far more significant in this environment.

For many hobbyists, water testing is a periodic thing, done on an "as I feel it" basis. Personally, I think the benefits of a more regular testing schedule yields a lot of good benefits for us.

Your testing regimen should include things like pH, TDS, alkalinity, and if you're so inclined, nitrate and phosphate. Logging this information over time will give us all some good data upon which to develop our expectations and "best practices" for water quality management. It's important for the hobby overall to document as much information as possible about how our botanical-style/blackwater aquariums establish and operate. This gives the widest variety of hobbyists the most reasonable set of expectations about these systems.

Remember, it isn't just about a new aesthetic approach. It's about a more holistic natural approach and methodology.

Algae, and the fears which accompany it, are not entirely unfamiliar to us. However, I think that if we take a more "holistic" mindset about it, we'll be in a batter position to deal with it.

So, before you siphon out that algae patch, pull that group of weeds, or blast that Aiptaisa anemone with kalkwasser (for you reefers out there), pause for a second to consider why and how the "offending" life form came to be in that location.

And reflect upon how we can benefit by designing our aquariums to provide the optimum environment for each and every fish and plant that we treasure to grow and thrive. To give them every opportunity to do so is our challenge, and our obligation.

Stay patient. Stay diligent. Stay creative. Stay proactive. Stay consistent...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

First things first.

A bunch of you had asked me further about the idea I brought up recently in our piece on Kuhli loaches, about pre-stocking" an aquarium with food for your fishes before you add them. You wanted more specifics.

Okay, cool. Happy to accommodate. Of course, I need you to do a little exercise, first:

You're a fish.

Seriously. Make yourself a fish...for a second. (I think I'd be a Black Ghost Knife, FYI. What, you thought I'd be a Cardinal Tetra or something? Really? Sheesh!)

Would you like to move into a house which didn’t have a refrigerator full of food? I wouldn’t, for sure. Unlike humans, fishes seem to have not lost their "genetic programming" for grazing and hunting for food. Let’s face it—most of the waking hours of aquatic animals are devoted to acquiring food and reproducing. They need to have some food sources available to "hunt and graze" for.

That’s reality.

So why not help accommodate our your animals’ needs by supplementing their prepared diet with some “pre-stocked” natural foods in their new home? You know, slow down, get things "going" a bit, and then add the fishes?

I’m not talking about tossing in a few frozen brine shrimp hours before the first fishes go in the tank—I’m talking about a deliberate, systematic attempt to cultivate some living food sources within the system before a fish ever hits the water! Imagine a “new” system offering numerous foraging opportunities for it’s new inhabitants!

in our world, that might mean allowing some breakdown of the botanicals, or time for wood or other botanicals to recruit some biofilms, fungi- even turf algae on their surfaces before adding the fishes to the aquarium.

“Scott. You’re being impractical here! It could take months to accomplish this. I’ve just spent tons of money and time setting up this tank and you want me to deliberately keep this tank devoid of fishes while the biofilms form and Daphnia reproduce?”

Yes. Seriously.

I am a bit crazy. I’ll give you that.

Yet, with my last few systems, this is exactly what I did.

Why?

Well, for one thing, it creates a habitat for sighs which is uniquely suited to their needs in a different way.

Think abut the way most fishes live. They spend a large part of their existence foraging for food. Even in the cozy, comfortable confines of the aquarium.

So, why not create conditions for them which help accommodate this instinctive behavior, and provide opportunities for supplemental (or primary!) nutrition to be available to them by foraging.

Now, I have no illusions about this idea of "pre-stocking" being a bit challenging to execute.

I’m no genius, trust me. I don’t have half the skills many of you do but I have succeeded with many delicate “hard-to-feed” fishes over my hobby “career.”

Any "secret" to this?

None at all. I'm simply really fucking patient.

Success in this arena is simply a result of deploying..."radical patience." The practice of just moving really slowly and carefully when adding fishes to new tanks.

A really simple concept.

I mean, to some extent, we already deploy this practice with our blackwater/brackish, botanical-style tanks, right? The very process of creating a botanical-style aquarium lends itself to this "on board supplemental food production" concept. A sort of "food web" that's pretty analogous to those found in Nature, right?

And one of the most important functions of many botanically-influenced wild habitats is the support of food webs. As we've discussed before in this blog, the leaf litter zones in tropical waters are home to a remarkable diversity of life, ranging from microbial to fungal, as well as crustaceans and insects...oh, and fishes, too! These life forms are the basis of complex and dynamic food webs, which are one key to the productivity of these habitats.

You can do this. You can foster such a "food web"- or the basis for one- in your aquarium!

Wait a minimum of three weeks—and even up to a month or two if you can stand it, and you will have a surprisingly large population of micro and macro fauna upon which your fishes can forage between feedings.

Having a “pre-stocked” system helps reduce a considerable amount of stress for new inhabitants, particularly for wild fishes, or fishes that have reputations as “delicate” feeders.

And think about it for a second.

This is really a natural analog of sorts. Fishes that live in inundated forest floors (yeah, the igapo again!) return to these areas to "follow the food" once they flood. In fact, other than the physical flooding itself, this pursuit of food sources is the key factor in the migration of fishes into these habitats.

In the aquarium, it's not all that different. Our systems are built on the process of decomposition and fostering microbial growth. It's a foundation of the botanical-style aquarium approach. Far different than the "typical" approach to starting an aquarium, which is really more reliant on filtration, external food inputs (from us!), and the execution of consistent maintenance to get it through the "startup" period, when a typical system is almost "sterile" compared to our botanical-style ones.

And the "waiting period" isn't all that long.

It just takes a few weeks, really. You’ll see fungal growth. You'll see some breakdown of the botanicals brought on by bacterial action or the feeding habits of small crustaceans and fungi. If you "pre-stock", you might even see the emergence of a significant population of copepods, amphipods, and other creatures crawling about, free from fishy predators, foraging on algae and detritus, and happily reproducing in your tank.

We kind of know this already, though- right?

This is really analogous to the tried-and-true practice of cultivating some turf algae on rocks either in or from outside your tank before adding herbivorous, grazing fishes, to give them some "grazing material."

Radical patience yields impressive results.

I realize that it takes a certain patience- and a certain leap of faith-to do this. I’ve been doing it for a while and I can tell you it works.

If you like delicate or difficult-to-feed fishes, or even if you simply want to try something a bit different "just because", it’s a technique that could help you succeed where you might have failed in the past with some species.

The point of this practice is pretty simple. Embrassingly so, actually: To help develop—or I should say—to encourage the development and accumulation of some supplemental natural food sources in the system before they are quickly devastated by your fishes.

It's kind of the "refugium" concept yet again.

And it's not all decomposing leaves and twigs and stuff that helps accomplish this- in Nature and I the aquaruum.

One of the important food resources in natural aquatic systems are what are known as macrophytes- aquatic plants which grow in and around the water, emerged, submerged, floating, etc. Not only do macrophytes contribute to the physical structure and spatial organization of the water bodies they inhabit, they are primary contributors to the overall biological stability of the habitat, conditioning the physical parameters of the water.

Of course, anyone who keeps a planted aquarium could attest to that, right?

One of the interesting things about macrophytes is that, although there are a lot of fishes which feed directlyupon them, in this context, the plants themselves are perhaps most valuable as a microhabitat for algae, zooplankton, and other organisms which fishes feed on. Small aquatic crustaceans seek out the shelter of plants for both the food resources they provide (i.e.; zooplankton, diatoms) and for protection from predators (yeah, the fishes!).

Of course, leaves are a huge and important component in the construction of a food web.

Decomposing leaves will not only provide material for the fishes to feed on and among, they will provide a natural "shelter" for them as well, potentially eliminating or reducing stresses.

And the possible benefits to fish fry are interesting Gand important, IMHO.

In Nature, many fry which do not receive parental care tend to hide in the leaves or other biocover in their environment, and providing such natural conditions will certainly accommodate this behavior.

Decomposing leaves can stimulate a certain amount of microbial growth, with infusoria and even forms of bacteria becoming potential food sources for fry. I've read a few studies where phototrophic bacteria were added to the diet of larval fishes, producing measurably higher growth rates. Now, I'm not suggesting that your fry will gorge on beneficial bacteria "cultured" in situ in your blackwater nursery and grow exponentially faster.

However, I am suggesting that it might provide some beneficial supplemental nutrition at no cost to you!

I've experimented with the idea of "onboard food culturing" in several aquariums systems over the past few years, which were stocked heavily with leaves, twigs, and other botanical materials for the sole purpose of "culturing" (maybe a better term is "recruiting) biofilms, small crustaceans, etc. via decomposition. I have kept a few species of small characins in these systems with no supplemental feeding whatsoever and have seen these guys as fat and happy as any I have kept.

And it's the same with that beloved aquarium "catch all" of infusoria we just talked about...These organisms are likely to arise whenever plant matter decomposes in water, and in an aquarium with significant leaves and such, there is likely a higher population density of these ubiquitous organisms available to the young fishes, right?

Now, I'm not fooling myself into believing that a large bed of decomposing leaves and botanicals in your aquarium will satisfy the total nutritional needs of a batch of characins, but it might provide the support for some supplemental feeding! On the other hand, I've been playing with this recently in my "varzea" setup, stocked with a rich "compost" of soil and decomposing leaves, rearing the annual killifish Notholebias minimuswith great success.