- Continue Shopping

- Your Cart is Empty

The web of life...and food. And botanicals.

After almost two decades of playing with botanical-style aquariums, I've come to a conclusion that likely will not surprise any of you:

These systems are biologically diverse, and, if given the chance, are more than capable of meeting some of the nutritional needs of the resident fishes.

"Biologically diverse." That's the key.

There is a web of life out there, ready for us to embrace in our aquariums.

If you've followed us for any length of time, you're well aware that we are not just pushing you to play with natural, botanical-style aquariums only for the pretty aesthetics. I mean, yeah, they look awesome, but there is so much more to it than that. We are almost as obsessed with the function of these aquariums and the wild habitats which they attempt to represent!

And one of the most important functions of many botanically-influenced wild habitats is the support of food webs. As we've discussed before in this blog, the leaf litter zones in tropical waters are home to a remarkable diversity of life, ranging from microbial to fungal, as well as crustaceans and insects...oh, and fishes, too! These life forms are the basis of complex and dynamic food webs, which are one key to the productivity of these habitats.

By researching, developing, and managing our own botanically-infleunced aquaria, particularly those with leaf litter beds, we may be on the cusp of finding new ways to create "nurseries" for the rearing of many fishes!

At least upon superficial examination, our aquarium leaf litter/botanical beds seem to function much like their wild counterparts, creating an extremely rich "microhabitat" within our aquariums. And initial reports form those of you who breed and rear fishes in your intentionally "botanically-stocked" aquariums are that you're seeing great color, more regularity in spawns, and higher survival rates from some species.

We're just beginning here, bit the future is wild open for huge hobby-level contributions that can lead to some serious breakthroughs!

Let's consider some of the types of food sources that our fishes might utilize in the wild habitats that we try so hard to replicate in our aquariums, and perhaps develop a greater appreciation for them when they appear in our tanks. Perhaps we will even attempt to foster and utilize them to our fishes' benefits in unique ways?

Maybe we will finally overcome generations of fear over detritus and fungi and biofilms- the life-forms which power the aquatic ecosystems we strive to duplicate in our aquariums. Maybe, rather than attempting to "erase" these thing which go against our "Instagram-influenced aesthetics" of how we think that Nature SHOULD look, we might want to meet Nature where she is and work with her.

And then, we might see the real beauty- and benefits- of unedited Nature.

One of the important food resources in natural aquatic systems are what are known as macrophytes- aquatic plants which grow in and around the water, emerged, submerged, floating, etc. Not only do macrophytes contribute to the physical structure and spatial organization of the water bodies they inhabit, they are primary contributors to the overall biological stability of the habitat, conditioning the physical parameters of the water. Of course, anyone who keeps a planted aquarium could attest to that, right?

One of the interesting things about macrophytes is that, although there are a lot of fishes which feed directly upon them, in this context, the plants themselves are perhaps most valuable as a microhabitat for algae, zooplankton, and other organisms which fishes feed on. Small aquatic crustaceans seek out the shelter of plants for both the food resources they provide (i.e.; zooplankton, diatoms) and for protection from predators (yeah, the fishes!).

I have personally set up a couple of systems recently to play with this idea- botanical-influenced planted aquariums, and have experimented with going extended periods of time without feeding my fishes who lived in these tanks- and they have remained as fat and happy as when they were added to the tanks...

Something is there- literally!

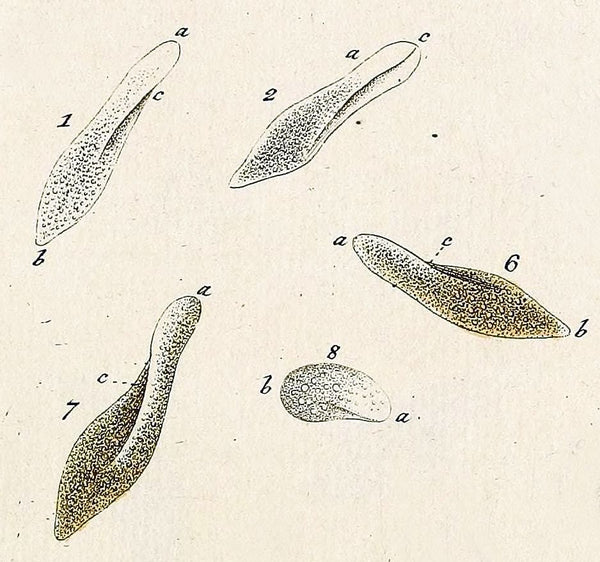

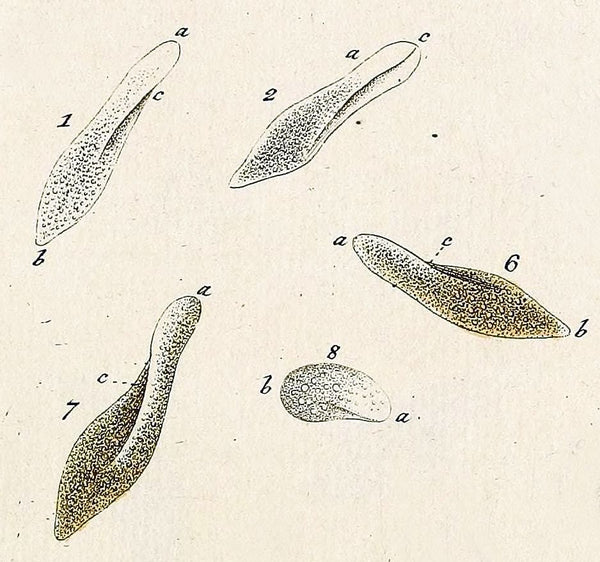

Perhaps most interesting to us blackwater/botanical-style aquarium people are epiphytes. These are organisms which grow on the surface of plants or other substrates and derive their nutrients from the surrounding environment. They are important in the nutrient cycling and uptake in both nature and the aquarium, adding to the biodiversity, and serving as an important food source for many species of fishes.

In the case of our aquatic habitats, like streams, ponds, and inundated forests, epiphytes are abundant, and many fishes will spend large amounts of time foraging the biocover on tree trunks, branches, leaves, and other botanical materials. Although most animals use leaves and tree branches for shelter and not directly as a food item, grazing on this epiphytic growth is very important.

Some organisms, such as nematodes and chironomids ("Bloodworms!") will dig into the leaf structures and feed on the tissues themselves, as well as the fungi and bacteria found in and among them. These organisms, in turn, become part of the diet for many fishes.

And the resulting detritus produced by the "processed" and decomposing pant matter is considered by many aquatic ecologists to be an extremely significant food source for many fishes, especially in areas such as Amazonia and Southeast Asia, where the detritus is considered an essential factor in the food webs of these habitats. And of course, if you observe the behavior of many of your fishes in the aquarium, such as characins, cyprinids, Loricarids, and others, you'll see that in between feedings, they'll spend an awful lot of time picking at "stuff" on the bottom of the tank. In a botanical style aquarium, this is a pretty common occurrence, and I believe an important benefit of this type of system.

I am of the opinion that a botanical-style aquarium, complete with its decomposing leaves and seed pods, can serve as a sort of "buffet" for many fishes- even those who's primary food sources are known to be things like insects and worms and such. Detritus and the organisms within it can provide an excellent supplemental food source for our fishes!

Just like in Nature.

It's well known that in many habitats, like inundated forest floors, etc., fishes will adjust their feeding strategies to utilize the available food sources at different times of the year, such as the "dry season", etc. And it's also known that many fish fry feed actively on bacteria and fungi in these habitats...so I suggest once again that a blackwater/botanical-style aquarium could be an excellent sort of "nursery" for many fish species!

You'll often hear the term "periphyton" mentioned in a similar context, and I think that, for our purposes, we can essentially consider it in the same manner as we do "epiphytic matter." Periphyton is essentially a "catch all" term for a mixture of cyanobacteria, algae, various microbes, and of course- detritus, which is found attached or in extremely close proximity to various submerged surfaces. Again, fishes will graze on this stuff constantly.

And then, of course, there's the "allochthonous input" that we've talked about so much here: Foods from the surrounding environment, such as flowers, fruits, terrestrial insects, etc. These are extremely important foods for many fish species that live in these habitats. We mimic this process when we feed our fishes prepared foods, as stuff literally "rains from the sky!" Now, I think that what we feed to our fishes directly in this fashion is equally as important as how it's fed.

I'd like to see much more experimentation with foods like live ants, fruit flies, and other winged insects. Of course, I can hear the protests already: "Not in MY house, Fellman!" I get it. I mean, who wants a plague of winged insects getting loose in their suburban home because of some aquarium feeding experiment gone awry, right?

That being said, I would encourage some experimentation with ants and the already fairly common wingless fruit flies. Can you imagine one day recommending an "Ant Farm" as a piece of essential aquarium food culturing equipment?

Why not, right?

And of course, easier yet- we can also foster the growth of potential food sources that don't fly or crawl around- they just arise when botanicals and wood and stuff meet water...We just need to not snuff them out as soon as they appear!

As many of you may know, I've often been sort of amused by the panic that many non-botanical-style-aquarium-loving hobbyists express when a new piece of driftwood is submerged in the aquarium, often resulting in an accumulation of fungi, algal growth and biofilm.

I realize this stuff can look pretty shitty to many of you, particularly when you're trying to set up a super-cool, "sterile high-concept" aquascaped tank.

That being said, I think we need to let ourselves embrace this stuff and celebrate it for what it is: Life. Sustenance. Diversity. Foraging. I think that those of us who maintain blackwater. botanical-style aquariums have made the "mental shift" to understand, accept, and even appreciate the appearance of this stuff.

We look at Nature.

Natural habitats are absolutely filled with this stuff...in every nook and cranny. It's like the whole game here- an explosion of life-giving materials, free for the taking...

A true gift from Nature.

Yet, for a century or so in the hobby, our first instinct is to reach for the algae scraper or siphon hose, and lament our misfortune with our friends.

It need not be this way. Its appearance in our tanks is a blessing.

Really.

You call it "mess." I call it "food."

Another "mental shift", I suppose...one which many of you have already made, no doubt. Or, I hope you have..or can.

I certainly look forward to seeing many examples of us utilizing "what we've got" to the advantage of our fishes! AGAIN:

A truly "natural" aquarium is not sterile. It encourages the accumulation of organic materials and other nutrients- not in excess, of course. Biofilms, fungi, algae...detritus...all have their place in the aquarium. Not as an excuse for lousy or lazy husbandry- no- but as supplemental food sources to power the life in our tanks.

Real gifts from Nature...that you can benefit from simply by "working the web" of life which arises without our intervention as soon as leaves, wood, and water mix.

Keep making those mental shifts. Meet Nature where it is. She won't let you down. I promise.

Stay brave. Stay inquisitive. Stay open-minded. Stay grateful. Stay methodical...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Bringing up the biome...

There is a certain allure- a fascination...even obsession about considering our aquariums as little closed ecosystems, reacting to both internal and external inputs, stimuli, and environmental pressures.

When you think of aquariums in this manner, they become a whole lot less of a "pet holding container" and a lot more of a little slice of Nature that you're recreating in your home. And of course, the botanical-style aquarium is an expression of this thinking. A microcosm fully dependent upon botanical materials to impact fully effect the environment.

One of the aspects of utilizing botanicals in our aquariums that we discuss, but can't think about enough, is their importance to the "microbiome" of the aquarium environment.

A "microbiome", by definition, is defined as "...a community of microorganisms (such as bacteria, fungi, and viruses) that inhabit a particular environment." (according to Merriam-Webster)

Now, sure, every aquarium has a microbiome to a certain extent:

We have the beneficial bacteria which facilitate the nitrogen cycle, and play an indespensible role in the function of our little worlds. The botanical-style aquarium is no different; in fact, this is where I start wondering...It's the place where my basic high school and college elective-course biology falls away, and you get into more complex aspects of aquatic ecology in aquariums.

Yet, it's important to at least understand this concept as it can relate to aquariums. It's worth doing a bit of research and pondering. It'll educate you, challenge you, and make you a better overall aquarist. In this little blog, we can't possibly cover every aspect of this- but we can touch on a few points that are really fascinating and impactful.

An interesting place to start is to simply review a bit about the very composition of the materials that we play with, like seed pods and leaves and such, and how they interact with the aquatic environments that we've created.

Many seed pods and similar botanicals contain a substance known as lignin. Lignin is defined as a group of organic polymers which are essentially the structural materials which support the tissues of vascular plants. They are common in bark, wood, and yeah- seed pods, providing protection from rotting and structural rigidity.

In other words, they make seed pods kinda tough.

That being said, they are typically broken down by fungi and bacteria in aquatic environments. Inputs of terrestrial materials like leaf litter and seed pods into aquatic habitats can leach dissolved organic carbon (DOC), rich in lignin and cellulose. Factors like light intensity, mineral hardness, and the composition of the aforementioned bacterial /fungal community all affect the degree to which this material is broken down into its constituent parts in this environment.

Hmm...something we've kind of known for a while, right?

So, lignin is a major component of the "stuff" that's leached into our aquatic environments, along with that other big "player"- tannin.

Tannins, according to chemists, are a group of "astringent biomolecules" that bind to and precipitate proteins and other organic compounds. They're in almost every plant around, and are thought to play a role in protecting the plants from predation and potentially aid in their growth. As you might imagine, they are super-abundant in...leaves. In fact, it's thought that tannins comprise as much as 50% of the dry weight of leaves!

Whoa!

And of course, tannins in leaves, wood, soils, and plant materials tend to be highly water soluble, creating our beloved blackwater as they decompose. As the tannins leach into the water, they create that transparent, yet darkly-stained water we love so much!

In simplified terms, blackwater tends to occur when the rate of "carbon fixation" (photosynthesis) and its partial decay to soluble organic acids exceeds its rate of complete decay to carbon dioxide (oxidation).

Chew on that for a bit...Try to really wrap your head around it...

And sometimes, the research you do on these topics can unlock some interesting tangential information which can be applied to our work in aquairums...

Interesting tidbit of information from science: For those of you weirdos who like using wood, leaves and such in your aquariums, but hate the brown water (yeah, there are a few of you)- you can add baking soda to the water that you soak your wood and such in to accelerate the leaching process, as more alkaline solutions tend to draw out tannic acid from wood than pH neutral or acidic water does. Or you can simply keep using your 8.4 pH tap water!

"ARMCHAIR SPECULATION": This might be a good answer to why some people can't get the super dark tint they want for the long term...Based upon that model, if you have more alkaline water, those tannins are more quickly pulled out. So you might get an initial burst, but the color won't last all that long...

Interesting stuff, and all part of the little "stew" we make when we set up a botanical-style aquarium, right?

I think just having a bit more than a superficial understanding of the way botanicals and other materials interact with the aquatic environment, and how we can embrace and replicate these systems in our own aquariums is really important to the hobby. The real message here is to not be afraid of learning about seemingly complex chemical and biological nuances of blackwater systems, and to apply some of this knowledge to our aquatic practice.

Okay, let's think about the biology of these ecosystems for a bit, and contemplate how some aspects of their composition and function can be applied to our aquariums.

During the rainy season in the tropics, overflowing streams flood the rainforest floor, accumulating materials which the fish communities utilize for food and shelter. And materials which fall from the surrounding trees and banks are major contributors to the productivity of this ecosystem. As the waters recede somewhat, temporary streams flow through these areas.

They become rich, complex ecosystems, bristling with life.

Interestingly, scientists have found that these streams have very little internal production of food sources for their resident fishes. Rather the food sources come from materials such as plants, fruits, leaves, and pieces of wood which come from the surrounding terrestrial environment.

Oh, and insects.

Lots of insects from the surrounding trees and "shorelines", which fall into the water.

These materials and organisms are known as "allochthonous inputs" in ecology- materials imported into an ecosystem from outside of it. This is rather interesting point. Essentially, it means that these areas, rich habitats that they are, are almost completely influenced by outside materials....

And, as one might expect- as more materials fall from the trees and surrounding dry areas, the greater the abundance of fishes and other aquatic animals which utilize them is found.

And materials will continue to fall into the water and accumulate throughout the periods of inundation, maintaining the richness of the habitat as others decompose or are acted on by the organisms residing in the water.

Not unlike an aquarium, right?

I mean, we need to get it in our heads that botanicals are "consumable" items, which need to be regularly replaced as they decompose, in order to maintain environmental consistency.

Yeah, it's the "jumping off point" for one of my favorite speculative areas in our little hobby speciality:

With botanicals breaking down in the aquarium as a result of the growth of fungi and microorganisms, I can't help but wonder if they perform, to some extent, a role in the management-or enhancement-of the nitrogen cycle.

In other words, does having a bunch of leaves and other botanical materials in the aquarium foster a larger population of these valuable organisms, capable of processing organics- thus creating a more stable, robust biological filtration capacity in the aquarium?

With a matrix of materials present, the bacteria (and their biofilms, as we've discussed a number of times here) have not only a "substrate" upon which to attach and colonize, but an "on board" food source which they can utilize as needed? Facultative bacteria, adaptable organisms which can use either dissolved oxygen or oxygen obtained from food materials such as sulfate or nitrate ions, would also be capable of switching to fermentation or anaerobic respiration if oxygen is absent.

Hmm...fermentation.

We've talked about that before, right? And I'm not talking about this in regards to making kambocha, either! Botanical "layers"- particularly, leaf litter beds- in the wild, offer an interesting study in nutrient processing and food production for the surrounding aquatic ecosystems. And, although botanicals accumulate to significant depth in some areas, the processes which we are fascinated with even occur at surprisingly shallow depths...

One study of wild leaf litter beds in Amazonia indicated that the majority of the aerobic decomposition probably occurs in the upper 10 cm of the leaf litter bed, as lower material is more tightly packed, reducing O2 diffusion, and is generally older and already well decomposed. It is also thought that fermentation processes release acids (specifically, acetic acid), which help reduce the pH substantially within these beds.

So, we have biological processes occurring in botanical/leaf litter beds which a)facilitate nutrient processing in the habitat, b)contribute to the food chain, and c)potentially influence the chemical parameters of the water.

That's just like what happens in the wild habitats, isn't it?

Obviously, there is some analogous processes and benefits which occur when leaves and botanicals create a similar bed in a closed aquarium...What exactly they are is still a subject of ongoing investigation for us as aquarists.

MICRO RANT: With so much emphasis placed on the appearance of our aquariums by some of the new vendors on the scene, it's important to remind ourselves from time to time that there are functional benefits of utilizing botanicals that go far beyond the pretty look.

We as vendors can't merely talk up the impact of "tannins" that botanicals impart from an aesthetic standpoint, and "how extreme the color" they give off, without at least sharing information about some of the important environmental impact they can have on the aquarium. We do that- and our fellow vendors shouldn't, either. Step it up, guys. We're fostering a movement here.

Now, no discussion of botanical "benefits" would be complete without the usual caveats to be responsible, prepare thoroughly, move slowly, and observe and test your water. Fishes like Apistos can be notoriously finicky and even delicate if they're subjected to rapid environmental changes.

Blackwater is not a "miracle tonic" that will make every fish thrive, but it can provide some very interesting benefits if applied with common sense. When switching over your existing, inhabited aquarium to a botanical-style blackwater aquarium with a lower ph and alkalinity, you are making significant environmental changes that can impact the health of your fishes, and the need to move slowly and carefully is mandatory.

Okay, there's a whole lot there to unpack- drawing from a variety of scientific fields, such as biology, chemistry, and ecology, as well as from our everyday practices as aquarists. Yeah, we still don't know exactly which tannins are imparted to the water by a specific botanical. And for that matter, we don't know which tannins provide what specific effects on fishes or their aquatic environment, and what concentrations are found in their natural habitats.

And again, it's not necessarily that we are creating a new "thing"- we're simply seeing a correlation to the processes that we are fostering in our aquariums and what occurs in nature, and realizing that we can embrace, study, and benefit from them in our aquarium work.

I think that there are so many different things that we can play with- and so many nuances that we can investigate and manipulate in our aquariums to influence fish health and spawning behavior. changing botanical concentrations and such during various times of the year- creating ephemeral aquatic systems and other unique environmental-themed displays.

I think that this could even add a new nuance to a typical biotope aquarium, such as creating an aquarium which simulates the "Preto da Eva River in Brazil in October", or whatever...with appropriate environmental conditions, such as water level, amounts of allochthonous material, etc.

Not just an aesthetic representation designed to mimic the look of the habitat- but a "functionally aesthetic" representation of a natural habitat, intended to operate like one..Full time.

And it starts with understanding what's going on in Nature, and how we can replicate it on a more realistic level in the aquarium. Like no other time in the aquarium hobby, the information, equipment, materials, and techniques are starting to converge and create a very interesting opportunity for all sorts of hobbyists to advance the state of the art of the hobby.

Nuances. Micro-influences. Subtle steps.

All part of "bringing up the biome", right?

Studying the influences of Nature on aquatic environments, and how to replicate and incorporate these influences into our aquariums is the key. Building a specialized aquatic microcosm in our tanks will unlock so many secrets and lead to amazing breakthroughs with our fishes- and a greater understanding of the precious natural habitats from which they come.

Stay involved. Stay excited. Stay inquisitive. Stay diligent. Stay resourceful. Stay informed...

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Algal praise?

As aquarium hobbyists, we're sort of "programmed" to freak out about the appearance of algae in our systems, aren't we? It's like the "default" to go "ape-shit crazy" when algae appears in our tanks.

I haven't touched on one of the more interesting "benefits" of a botanical-style blackwater aquarium that many of us have experienced: The fact that the occurrence of nuisance algae outbreaks seem to be relatively uncommon in these systems. Not a rarity- just not all that common.

Or, is it?

While it would be intellectually dishonest (and just plain untrue) for me to assert that blackwater/botanical aquariums aren't susceptible to algae outbreaks, it is sort of remarkable that we simply don't have massive algae issues in these types of aquarium on a regular basis. At least, none that anyone talks about!

I have to admit, that I have never had one of those nightmare algal blooms in a blackwater aquarium...unless my goal was to intentionally create one. And of course, in the interest of pushing the state of the art of our practice- I have succeeded at creating some algal blooms!

Yea, I did. And, as you'd imagine, it's not all that difficult. Blast the damn thing with light, and, well, yeah. Algae farm.

I mean, algae likes "fuel", right?

Our tanks feature a lot of botanicals and their associated materials decomposing on a near-constant basis. As we know, some of this material is utilized by fishes for supplemental food. Some of it is processed my crustaceans, bacteria, fungi, and other microorganisms. And yeah, some of the compounds produced by it as it decomposes (nitrates, phosphates, trace elements) is utilized by algae.

I rather fancy the stuff, actually.

Damn.

And the simple fact is- algae will bloom and proliferate wherever and whenever the proper conditions- nutrients, light, flow, and lack of heavy consumers- combine in the aquarium environment. And quite honestly, it's not that amazing, right? We know this.

Yet, when we have darkly tinted water and maybe not a ton of lighting over our tanks, it seems just a bit less common- usually!

And of course, Nature provides the example.

I read a study from the University of Georgia, which tested the idea of algae growth in blackwater streams, to determine if the limiting factor was chemical (nutrient) or light driven...and lo and behold, the study concluded that it wasn't necessarily some magic stuff in tannins and blackwater, as much as it was light limitation! Light-limiting effects of the blackwater itself were discovered to inhibit algal growth in coastal plain streams. As light penetrates the water, high DOC concentrations and suspended solids can scatter and absorb light, impacting algal growth significantly.

Okay, sounds like a bummer if you want to believe blackwater is "magic", but the study also concluded that blackwater systems were somewhat nutrient-limited, which also affected the growth of algae- although this was not concluded to be the primary factor which inhibited algae growth.

In fact, another study I perused about the Rio Negro concluded that it was found that there is a relatively small difference in "respiration rates" between "whitewater" and "blackwater" rivers, and that the presumption that blackwater systems are more "sterile" is sort of...overstated.

Interestingly, the study also concluded that higher incidence of algal growth occurred in areas in Amazonia where water movement was minimal, or even stagnant, suggesting that, all things being equal, light limitation and water movement are possibly more significant than just higher nutrient concentrations alone!

And that makes sense, if you consider the long-held belief within the aquarium hobby that most plants don't do well in blackwater aquariums "because they don't get enough light!"

Yikes!

So the long-held aquarium attitude about blackwater having some algal-inhibiting properties is really based on the fact that it's...darker? I mean, every blackwater tank I have ever owned does have some algae present. Although, being a reef guy at heart, every aquarium I own has good water movement.

I know that in leaf-litter-dominated aquariums, which I love, I still keep a good amount of flow going. You'll often hear that depressed CO2 levels are instrumental in creating algal outbreaks, like the dreaded "black beard" algae.

Good flow is important. You don't have to have a wicked, jacuzzi-like flow. Just good, steady, movement and a bit of surface agitation.

This whole thing about even being able to limit nuisance algae in our tanks is interesting, because you'd think a tank dominated by decomposing leaf litter would be an algae farm, right?

And yet, I've experienced no more occurrence of algae in the leaf litter/twig substrate tanks than I have in other setups. On the other hand, regardless of what type of system I work with, I'm fanatical about husbandry and nutrient control/export...obviously, another key factor.

And since a lot of blackwater/botanical-style tanks are "hardscape only", with little or no plants, the lighting we are employing is typically strictly "aesthetic", right? So, you're not blasting a tank with decomposing pods and no plants with 14 hours of full spectrum light...Well, that certainly can be part of the reason why this type of tank often "magically" has essentially little to no nuisance algae despite all of the leaves and stuff, huh? We pin both the praise and the blame for algae on the wrong suspects, I think!

Man, this deserves more study...a lot of it.

And with more and more hobbyists playing with planted blackwater tanks, we'll have a greater "body of work" from which to draw. For that matter, more botanical, blackwater tanks in general means more material to analyze!

An here is another thing: As we've beaten into your head relentlessly, in our truly "natural style" tanks, we don't really care if there is some algae in there. We've made that "mental shift" that says it's okay to have some decomposing botanicals, brown water, biofilms, and yeah...algae. Because natural habitats do, too. So it's not so bad, right?

Let's think about algae in the aquarium to begin with...No, not the boring old "This is how algae problems happen in our aquariums..." lecture that you've read on every website known to man since the internet sprung to life. Yes, it smothers plants, which sucks if you like plants. You can find all of that that stuff everywhere. Rather, let's think about how we, as a group, mentally are opposed to the stuff in our tanks.

I mean, yeah, I know of no one that really enjoys a tank smothered in algae. It looks like crap, and is a "trophy" for incompetence, in the eyes of most aquarists. In fact, I remember reading once that more people quite the aquarium hobby over algae problems than almost anything else.

Yuck!

Well, sure- algae problems caused by obvious lapses in care or attention to normal maintenance, like overfeeding, lack of water changes, gross overstocking, etc. are signs of...incompetence. The occasional algae outbreaks that many hobbyists suffer through have all sorts of other potential causes, and can often be traced to a combination of small things that went unchecked, and are typically controlled in a relatively short amount of time once the causative factors are identified.

Yet, as a group, us hobbyists freak out about algae in our tanks. I can show you a hundred pics of algae and biofilm matrixes in the Amazon and the Rio Negro and say, "See it happens here too! Natural!" and the typical hobbyist will still be rendered speechless with horror.

And I can't even tell you what it would do to one of those "natural aquascaping" contest freaks or judges! People might die. You could be charged as an accessory to murder!

Do you want that on your conscience? 😆

So, not everyone gets it. Just like brown water.

Algae is the foundation of life, blah, blah, blah. Yet, it's also the foundation for a "cottage industry" of devices, chemicals, and treatment regimens designed to eradicate it.

I say, we can embrace it and understand why and how it forms and proliferates...and even embrace it for being an elegant- if aesthetically under appreciated- part of the botanical-style aquarium.

So, the round-about conclusion here is that:

1) Although there are many beneficial substances in blackwater, such as humic substances, tannins, etc., it's inconclusive if they alone are the reason (or even part of the reason) why we seem to have less incidence of algae in our blackwater aquariums. Some research suggests otherwise.

2) The light penetration limitation imposed by blackwater definitely has been shown to decrease algal growth.

3) Proper nutrient control and export mechanisms employed by the hobbyist can go a long way towards controlling excessive algal growths in the aquarium.

Okay, maybe not altogether earth-shattering revelations...Yet, important points to consider.

Yeah, we have a lot of work to do when it comes to understanding all of the dynamics of the "algae equation" in botanical-style aquariums.

Stay curious. Stay diligent. Stay engaged. Stay thoughtful...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Answering Nature's call. Talking points for the "botanical beginner..."

Our world of botanical-style aquariums has been, for want of a better world- evolving- and rapidly.

We have experienced a large influx of hobbyists into our specialty niche in the hobby- a remarkable trend that has started to bring out the idea of botanical-style aquariums from the shadows and into the mainstream.

And we receive lots and lots of questions from hobbyists new to our world; our way of thinking...And, as a proponent of the botanical-style aquarium approach, I think we still need to communicate our philosophies, the practices...the expectations to those interested in playing with this stuff.

Perhaps you- our regular reader/listener- doesn't need this "pep talk"; however, maybe someone you know is considering venturing into this area, and you want to give them a little dose of "reality" before they take the plunge?

There's still a lot of confusing and, quite frankly- outdated- information out there.

Hopefully, this little piece (in addition to referring them to our hundreds of blog posts on every aspect of this stuff! 😆) will give you a sort of "track" to run on when discussing botanical-style aquarium keeping with a fellow hobbyist who's contemplating such an aquarium.

And to you, the hobbyist considering who's jumping in to the "tinted" world, and who hasn't quite "pulled the trigger"- there is a starting point:

It starts with questions for yourself!

I suppose, if I were asked- and I am- the question about whether or not a hobbyist should try a botanical-style aquarium, I'd basically start with a single question:

Are you up to the task?

I know, it seriously sounds weird; even challenging or "off-putting." Kind of like I'm being an asshole, huh? That's certainly not the intent here.

However, it's an important question-a fundamental question to ask ourselves when contemplating setting up a botanical-style aquarium.

Why?

Because, when you start adding botanical materials to your aquarium, not only are you sort of "buying in" to a very different approach to aquarium-keeping than what you've been exposed to in the past- you're "signing up" to accept a completely different aesthetic than we are traditionally accustomed to as well.

Yeah, we are "opting in" to techniques which are somewhat contrary to what you've likely embraced before. You're accepting an aesthetic which deviates strongly from the traditional aquarium "look" that we have been accustomed to for generations. And it doesn't stop with the looks of the tank...

It starts with the way we look at Nature.

Once we visit, or look at a photo or video of a natural underwater habitat where tropical fishes live, and remove our hobby-contrived preconceptions of what it should look like from the equation and simply observe it as it is- we have to ask ourselves if this is how we want our tank to look...

That's the first mental shift.

Like, can you handle this stuff?

It's the ultimate "essence" of our philosophy. A way of capturing aspects of Nature in our aquarium in a manner that accepts it as it is, rather than how we want it to be.

And if we say "Yes" to the question, we then need to ask ourselves if we're okay accepting the rather unorthodox thinking and practices that are required of us to get an aquarium to that place.

You know, like adding seed pods, leaves, soils, etc. to an aquarium in an effort to capture the form and function of these natural habitats. To facilitate and embrace biofilms, fungal growth, detritus, and decomposition...To adopt a philosophy that says, "It's time to take inspiration from the reality of Nature, not just its essence."

It's about accepting the appearance of biofilms, murky water, algae, decomposing botanical materials, and acknowledging that these things occur in our aquariums, too, and can be managed to take advantage of their benefits. You know- to provide supplemental food sources, "nurseries" for fry, and as interesting little ways to impart beneficial humic substances and dissolved organic compounds into the water.

Just like in Nature.

Realizing that the very act of adding natural materials like seed pods and leaves fosters the development of biofilms, less-than-crystal-clear water, and detritus...

And that this is what you actually WANT.

Another mental shift.

Understanding once and for all accept that things are not aesthetically "perfect" in Nature, in the sense of being neat and orderly from a "design" aspect.

Understanding that, yeah, in nature, you have branches, rocks and botanical materials scattered about on the bottom of streams in a seemingly random, disorderly pattern. Or..are they? Could it be that current, weather events, and the processes of physical decomposition distribute materials the way they do for a reason?

Could we benefit from replicating this dynamic in our aquariums?

And, is there not incredible beauty in that apparent "randomness?"

I think so.

Do you?

On a practical level, there are some things that you need to accept:

-You have to prepare all of the botanical materials you intend to add to your aquarium.

-You need to add them slowly, gauging the impact of their additions as you go.

-Your water may have a slight "haze" to it. This is likely caused by "fines" from the surface tissues of the botanicals after submersion, and possibly- from a "bloom" of bacteria resulting from their addition to the aquarium.

-The botanicals and leaves will start to develop stringy biofilms of bacteria on their surfaces. These will be present for much of the time that they are in the aquarium.

-The water will tint up slowly, and to a degree determined by the type and quantity of materials you add, as well as a number of other factors.

-You must be very patient as the aquarium breaks in.

-The materials that you added to the aquarium will begin to soften and break down after a few weeks, ultimately decomposing slowly. They should be replenished regularly.

-Detritus will begin to accumulate in your aquarium as the botanicals break down. You might want to keep it in your system.

-You need to accept a different definition of what a "clean" aquarium is, aesthetic-wise.

-The look of your aquarium will evolve over time as the botanical materials break down and are moved about by the fishes in the aquarium.

Can you handle all of that?

Yeah, it's different.

Well, a lot of it is, anyways. But not all of it.

Although botanical-style aquariums are not "set-and-forget" systems, they don't require maintenance or husbandry practices that are so much complex than what we do with any other systems. It's about water exchanges, cleaning and replacing filter media, monitoring water parameters, and observation.

The nitrogen cycle is the nitrogen cycle. No escaping that. And yes, our aquariums are not "open" natural systems- but they do respond and adapt to many of the same changes and inputs and influences that natural habitats do.

Some of this IS stuff we all know how to do and work with already.

It's a matter of marrying this stuff with a new mindset.

Yes, most of the adjustments and shifts we have to make are mental ones. The techniques we use are simply contextually-adapted versions of the same stuff we've been doing for generations in the aquarium hobby.

Ceding some of the "heavy lifting" to Nature is an uncomfortable, perhaps even scary thing for many hobbyists. It's not what we've been taught to do over generations in the aquarium hobby. We're taught to manage, control, dictate- not to accept.

As we've discussed before, a botanical-style aquarium has a “cadence” of its own, which we can set up- but we must let Nature dictate the timing and sequencing after that.

You kind of know the sequence here already, right? The sensory expectations and processes...

It starts with an empty tank. Then, there's lush fragrance exuded by crisp botanicals during preparation. The excitement of the initial “placement" of the botanicals within the tank. Taking it all in. The gradual “tinting” of the aquarium water.

The softening of the botanicals.

The gradual development of biofilms and algae “patinas.” Perhaps, even a bit of cloudiness from time to time because of microbial growth.

Ultimately, there's the decomposition.

All part of a process which can’t be “hacked” or rushed. We can change some of the physical aspects of our tanks (equipment, hardscape, etc.), but Mother Nature is in control of the "big picture stuff."

She "calls the shots" here.

And I think that's perhaps the most important lesson that we can learn from our aquariums. As aquarists, we can do a lot- we can change the equipment, correct initial mistakes or shortcomings the system might have had from the beginning. Stuff like that.

However, it's all about creating conditions for optimized function and evolution in our aquariums...

We "set the stage", so to speak.

Nature does the rest.

Much of the success and enjoyment that you will derive from a botanical-style aquarium is based on accepting and allowing Nature to do what She does, and continuing to embrace and appreciate her work in your tank.

Yeah, mental shifts abound in this hobby specialty; they're "foundational"- they're a huge part of what we need to accept in order to be successful with it. It's not "difficult" to create one of these tanks...once you've made those mental shifts.

If you're about to decide on creating a botanical-style aquarium, ask yourself the most basic question:

Are you up to the challenge? Will you answer Nature's call?

Still interested?

I hope that you are. We certainly could use you in our world.

Stay open-minded. Stay curious. Stay diligent. Stay creative. Stay observant. Stay undaunted...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Manfiesto 2.0: The experience...

Someone just had to do it.

Someone asked me about the underlying philosophy and "concept" behind Tannin and my interpretation of the place that the natural, botanical-style aquarium occupies in the aquarium hobby.

So, I took the bait. Here's the answer, J.C. It's sounding a lot more like a "manifesto" of sorts, but I suppose it's what I'm feeling today, lol.

Because you asked. 😆:

There is something very pure and evocative-even a bit "uncomfortable" about utilizing botanical materials in the aquarium. Selecting, preparing, and utilizing them is more than just a practice- it's an experience. A journey. One which we can all take- and all benefit from.

Right along with our fishes, of course.

The energy and creativity that you bring with you on the journey tends to become amplified during the experience. We don’t want everyone walking away feeling the same thing, quite the opposite actually.

That uniqueness is a large part of the experience.

The experience is largely about discovery.

I believe that all aquarists are wildly curious about the natural world, but that they tend to "overcomplicate" what is unknown, not well understood, or outside of the lines of "conventional aquarium aesthetics and practices"-and literally "polish out" the true beauty of Nature in the process-often ascribing "rules" and "standards" for how our interpretations of Nature must look.

Such rules, in my opinion, not only stifle the creative process- they serve to deny Nature the opportunity to do as She's done for eons- to seek a path via evolution and change to forge a successful ecosystem for its inhabitants. When we seek to "edit" Nature because the "look" of Her process doesn't comport with our sense of aesthetics, we are, in my opinion, no longer attempting to replicate Nature as it is.

Suffice it to say, there are NO rules in rediscovering the unfiltered art beneath the surface. Our "movement" believes in representing Nature as it exists in both form and function, without removing the very attributes of randomness and resulting function that make it so amazing.

We are utterly inspired by this.

The only "rules" that should be embraced are those which Nature has laid down over the millennia. Rules that govern the function of the natural aquatic environments of the world. "Rules" that dictate how biological processes work.

We are about the preservation of biofilms, decomposition, and that "patina" of biocover that exists when terrestrial materials contact water. The change in water color and chemistry as tannins and humic substances from leaves and botanicals work their way into the milieu.

Understanding that these materials physically break down and influence the environment...and that this process doesn't always conform to our hobby interpretation of what is "beautiful" leads to a greater appreciation of the ephemeral, the transitional.

#blurthelines

It's a sexy hashtag that we've embraced over the years for Tannin- it sounds cool. Yet, it's one which, in my opinion, captures the ultimate "essence" of our philosophy. A way of capturing aspects of nature in our aquarium in a manner that accepts it as it is, rather than how we want it to be. Understanding that, by allowing Nature to do what she does, we are truly blurring the lines between the wild aquatic habitats of the world and our aquariums.

Indeed, fostering a true slice of the natural world in our homes- in all of its splendor.

Simplicity. Complexity. Creativity. Transience. "Randomness."

We receive so many PM's, emails, phone calls, and other inquiries from hobbyists when we run pieces featuring pics and discussions about natural environments as topics for modeling our aquaria, excited about the details, and how they can be replicated in an aquarium.

This is a really cool thing.

Yet, sometimes, someone will pose a question like, "How does what you talk about differ from the concept of the "biotope aquarium" idea that you see so often in the hobby?"

It's a good one.

The answer is, it doesn't differ all that much, with the exception being that biotope aquariums, even though they seek to replicate much of the look and environmental conditions of a given habitat, yet seem to eschew some of the "functional" aspects. Like, they'll often incorporate some of the same materials that we do. They can nail the look and the pH and flow and light and such.

Yeah, many use leaves and botanicals beautifully. However, they're typically used more for the appearance-sort of like "props"- as opposed to facilitating decomposition, the growth of biofilms, microorganisms, fungal growths, etc. It's a bit less "functional" and a bit more "aesthetic", IMHO.

The difference between what they do and what we do us subtle. It's in the management; the nuance.

Although we might also make "geographic transgressions" and incorporate materials from different parts of the world to recreate the aesthetic part without apologies. We won't obsess over making sure that every twig, leaf, and seed pod is the exact type found in a given region. "Generic tropical" is okay by us when it comes to materials we use. Because we're about creating the function as much as-if not more than- the form. We're all about the overall picture. "Inspired by..." is our mantra.

We're seeing a greater understanding for the random beauty of Nature- in bother wild habitat images we study and the aquariums that we create.

And the cool thing that we've noticed is that every aquarium pic that is shared by our community, which incorporates botanical materials and other elements of nature in a similar matter is studied, elevated..often celebrated- as a representation of the genius of nature in all of its random glory.

It makes sense.

We've made a collective "mental shift" as a community.

In my own rebellious way, I can't help but think that part of this enthusiasm which our community has for this stuff is that aquarium hobbyists in general have a bit of a "rebellious streak", too, and that maybe, just maybe- we're a bit well, "over" the idea of the "rule-centric", mono-stylistic, overly dogmatic thinking that has dominated the aquascaping and biotope aquarium world for the better part of a decade or two.

Again, my encouragement to you:

Maybe it's time to look at nature as an inspiration again- but to look at nature as it exists- not trying to sanitize it; clean it up to meet our expectations of what an aquarium is "supposed to look like."

And by the same token, understanding that not every hobbyist wants to-or can-go to the other extreme-trying to validate every twig, rock, and plant in a given habitat, as if we're being "scored" by some higher power- a universal "quality assurance team"- which must certify that each and every rock and branch is, indeed from the Rio Manacapuru, for example, or your work is just some sort of travesty.

I find that a bit too restricting for my taste.

Not that there is anything "wrong" with this pursuit, or that I take any issue with talented hobbyists who enjoy that route. I identify with them far more than the "high concept aquascaping" crowd for sure! I simply believe that there is a "middle ground" of sorts, where the celebration of the function of Nature is the primary influence, and accepting it and its function, while attempting to replicate it "as it is" -becomes the goal.

It's at the delta- the intersection of science and art.

It's where we play.

It's where we're most comfortable.

Not everyone is.

And, if you want to get really "meta" about this shit, think about it this way: The botanicals themselves already have a certain "feeling" and an "energy" to them. Everything we’ve done with them in our aquariums has been in response to using the botanicals as both the "armature" and "conduit" of the experience.

What happens next is in the hands of...Nature.

I'm pretty comfortable with that.

I suspect that many of you might be, too.

Stay brave. Stay proud. Stay open. Stay diligent. Stay observant. Stay humble...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

More love for Mangroves...

Yeah, time to talk about that salty stuff again...

When we launched "Estuary by Tannin Aquatics", our foray into the "botanical-style brackish aquarium", it was driven by an obsession with the functional and aesthetic aspects of this unique ecosystem. With a heavy emphasis on substrate, decomposition, and all of the good stuff that us "Tinters" seem to love, this more "honest" interpretation of the brackish water aquarium is proving irresistible to many of you!

It's something we're all sort of familiar with- yet it's all kind of new.

And it's starting to catch on...

Of course, when we are talking about brackish aquariums, we'd be completely remiss if we didn't mention the "stars" of this habitat, the Mangrove trees! In our practice , we'll focus on the readily available, reasonably hardy "Red Mangrove", Rhizophora mangle.

Hardly what you'd call an "aquarium plant"- I mean it's a tree.

That being said, the Mangrove is an amazing tree that certainly has applications for aquariums- specifically, brackish aquariums. Now, without going into a long, long, recap of what mangroves are and how they function (You can Google this stuff and get hundreds of hits with more information than you could ever want), let's just say that mangroves are a group of trees and shrubs which live in the coastal intertidal zone, in areas of warm, muddy, and salty conditions that would simply kill most plants.

They possess specialized organs within their branches, roots, and leaves which allow them to filter out sodium, absorb atmospheric air through their bark, and generally dominate their habitats because of these and other remarkable adaptations.

There are about 100-plus different species, all of which are found between tropical and subtropical latitudes near the equator, as they are intolerant of cold temperatures. Mangroves put down extensive "prop roots" into the mud and silt in which they grow, giving them the appearance of "walking on water." These root tangles help them withstand the daily rising/falling tides, and slow the movement of the water, allowing sediments to settle out and build up the bottom contours of the local ecosystem.

And of course, the intricate root system not only protects coastlines from erosion, it plays host to a huge variety of organisms, from oysters to fungi to bacteria to fishes. The fishes use mangrove habitats as a feeding ground, nursery area, and a place to shelter from predators.

Okay, you get it. But how do we use these trees in the aquarium. And wait a minute, you're talking about a tree? WTF?

I have no illusions about using live Mangrove plants (available as "propagules") to serve as "nutrient export" mechanisms as they do in nature. You've seen this touted in the hobby over the years, and it's kind of silly, if you ask me. They just grow too damn slow and achieve sizes far beyond anything we could ever hope to accommodate in our home aquarium displays as full-grown plants with large-scale nutrient export capabilities. We've played with this idea in saltwater tanks for decades and it's really more of a novelty than a legit impactful nutrient export mechanism.

Mangroves can and will, however, reach a couple of feet or so in an aquarium over a number of years, and they may be "pruned" to some extent to keep them at a "manageable" size, similar to a "bonsai" in some respects.

Oh, and before you start going off on me about their unsuitability for aquariums or some ethical implications for their "removal" from the wild, let's talk for a second about how we acquire them and how they grow. First off, removing a growing mangrove tree or seedling from the natural environment is damaging, unethical, illegal in most areas, and essentially idiotic.

NO one should even consider doing that. Period. Propagules are readily, legally available, easy to sprout, and should be utilized by any hobbyist who is contemplating playing with these trees.

And of course, part of the attraction of mangroves is the biome in which they occur.

Mangrove communities tend to accumulate nutrients, such as nitrogen and phosphorus, as well as some heavy metals and trace elements which become deposited into estuarine waters from terrestrial sources. These communities become sort of "nutrient sinks” for these materials.

And of course, Nature has a plan for this stuff: Mangrove roots, and the epiphytic algae often found on and among them, as well as bacteria, microorganisms, and a wide variety of invertebrates that reside there, take up and store the nutrients in their tissues.

Mangroves also function as continuous sources of carbon, nitrogen, and other elements, as their living material (i.e.; leaves and epiphytic organisms and plants) die and are decomposed. Tidal flushing assists in distributing this material to areas where other organisms may utilize it.

And here's the other cool thing:

Leaf litter is extremely important in a Mangrove ecosystem! Other materials, including twigs, branches, and other botanical items, is a major nutrient source to many creatures which function as "consumers" in these ecosystems. A study conducted in the 1970's by Pool et al, showed that the leaf litter in brackish Mangrove ecosystems is composed of "...approximately 68 – 86 % leaves, 3 – 15 % twigs, and 8 – 21 % "miscellaneous" material."

Thanks for the leaf litter "recipe", scientist friends! I mean, could we ask for more?

Now, let's be clear- Mangroves are different types of leaves than we are currently using in our blackwater tanks, but the concept is entirely familiar to us, right? (Oh, and by the way, it's totally okay to use mangrove leaves in your freshwater botanical-style blackwater aquarium!)

Once fallen, leaves and twigs decompose fairly rapidly in these habitats. As you might imagine, areas which have high tidal flushing rates, or which are flooded frequently, have faster rates of decomposition and export than other areas. Studies also found that decomposition of red mangrove litter proceeds faster under brackish conditions than under fresh water conditions.

Oh, and as the researchers so eloquently stated, some of these habitats have "brownish-colored water, resulting from organic matter leaching from the mangroves."

Algal growth, biofilms, brown water...at 1.005 specific gravity. Does it get any better?

So, let's think of this for just a minute, in terms of "that thing we do"- botanical-style aquariums. Just change up the "media" from "blackwater" to "brackish water", with a specific gravity of 1.005-1.010. We collectively as a community have a lot of experience managing higher-nutrient blackwater botanical systems, containing large numbers of leaves and other botanicals, right? Can this experience be applied to the brackish game?

Of course it can!

Like our "conventional" (Shit, that's funny to say, huh?) botanical-style systems, the brackish system embraces the same use of decomposing leaves, wood, and botanicals, with the added variables of a rich, "sediment-centric" substrate and the dynamic of specific gravity to contend with.

Interestingly, however, this type of system runs much like the blackwater, botanical-style systems that we are used to, with the exception that it is far more "nutrient rich" than the blackwater tanks. The dynamics of decomposition and the ephemeral nature of leaves and such in the water are analogous in many respects, as well.

Fungi and bacteria in brackish and saltwater mangrove ecosystems help facilitate the decomposition of mangrove material, just like in their pure freshwater counterparts. Interestingly, in scientific surveys, it's been determined that bacterial counts are generally higher on attached mangrove leaves than they are on freshly-fallen leaf litter, and this is kind of interesting, because ecologists feel that attached, undamaged mangroves leaves don't release much tannin, which, as we know might have some "anti-bacterial" properties. However, it's also been found that materials like humic acid, which are abundant in the mangroves, stimulate phytoplankton growth there.

Interesting, right?

Well, to me it is, lol.

The leaves of mangroves, as they break down, become subject to both leaching of the compounds in their tissues, as well as microbial breakdown. Compounds like potassium and carbohydrates are commonly leached quickly, followed by...tannins! Fungi are the "first responders" to leaf drop in mangrove communities, followed by bacteria, which serve to break down the leaves further.

So, in summary, you have a very active microbial community in a brackish water aquarium!

And yeah, the water in a brackish system "configured" in this manner is decidedly tinted- largely a function of the mangrove branches and roots, which, as they break down, release a significant amount of color-producing tannins from their tissues.

It's hardly a secret that mangrove wood, leaves, and bark are loaded with these tannins! In fact, Red Mangrove bark is one of our favorite "secret weapons" for producing incredibly deep tint in all types of botanical-style aquariums!

Now, the management of a botanical-style brackish tank is really surprisingly similar to that of a typical blackwater aquarium. The biggest difference is the salt and perhaps a greater interest in a deep, very rich substrate. Now, one parameter I changed since the system began was to increase the specific gravity from 1.004 to 1.010 This was done because it is a sort of "sweet spot" that many of the fishes which I am interested in (gobies, rainbow fishes, chromides, mollies, etc.) seem to fare quite well at this slightly higher S.G.

Also, I've made no secret about a desire at some future point to do a brackish system where I slowly push things all the way up to like 1.021 (on the low end of natural seawater specific gravity) and incorporate corals and macro algae into the display, along with marine fishes! And, if I do execute this, the "creep" towards this higher S.G. will be made over a very long period of time (close to a year), so it will be advantageous for the resident fishes to adapt to full-strength marine water slowly.

So, yeah, you're playing with salt...And, small concentrations of salt. Accuracy in measurement is essential.

HOT TIP: Get a digital refractometer. Pay real money and don't get a piece of shit toy. Consider it an essential tool to your hobby that you'd be foolish not to own.

Do it. You won't regret it at all. Seriously.

And sure, managing a system that "floats" between two realms (freshwater and marine) seems like a bit of a balancing act, I know..because it is. However, it's not difficult. You simply apply the lessons you've learned playing with all of this crazy botanical-style blackwater stuff we talk about all the time.

Yes, you might kill some stuff, because you may not be used to managing a higher-nutrient brackish water system. You have a number of variables, ranging from the specific gravity to the bioload, to take into consideration. Your skills will be challenged, but the lessons learned in the blackwater, botanical-style aquariums that we're more familiar with will provide you a huge "experience base" that will assist you in navigating the "tinted" brackish water, botanical-style aquarium.

Now, this IS a different type of approach to brackish aquariums.

However, it's likely not "ground-breaking", in that it's never, ever before been done like this before.

I just don't think that t's never been embraced like this before: Met head-on for what it is- what it can be, instead of how we wanted to make it (bright white sand, crystal-clear water, and a few light-colored rocks and seashells...A perfect example of Nature "edited" to our aesthetic "standards"). Rather, it's an evolution- a step forward out of the artificially-induced restraints of "this is how it's always been done"- another exploration into what the natural environment is REALLY like- and understanding, embracing and appreciating its aesthetics, functionality, and richness.

In my opinion, the key to our "evolved" brackish-water aquarium approach is looking at the substrate- and the other materials which accumulate on the bottom of the aquarium- as an essential and highly important component of the system.

The bottom of this type of habitat is covered with a thin layer of mangrove leaf litter- and of course, that's part of the attraction here! This will not only provide an aesthetically interesting substrate- it will offer functional benefits as well- imparting minerals, trace elements, and organic acids to the water.

Mangrove leaf litter, like its freshwater counterpart, is the literal "base" for developing our brackish-water aquarium "food chain", from which microbial, fungal, and crustacean growth will benefit. And of course, these leaves will impart some tannins into the water, just as any of our other leaves will!

And you can play with many different types of substrate materials, ranging from sand to mud and everything in between. The richer the better, as far as I'm concerned.

Again, a different approach, fro ma different angle.

The biggest headache. Fishes.

And of course, no brackish water aquarium is complete without brackish-water fishes...And traditionally, that has been a bit of a challenge, in terms of finding some "different" fishes than we've previously associated with brackish aquariums. I think that this will continue to be a bit of a challenge, because some of the fishes that we want are still elusive in the hobby.

New brackish-water fishes will become more readily available when the market demand is there. In the mean time, we can focus on some of the cool fishes from these habitats which are currently available to us.

I think that the key, as always- is more and more hobbyists getting involved in this unique hobby specialty area.

I'm proud to have pushed this type of approach, and even prouder that many of you have been inspired to try it as well! Keep pushing outwards. Keep trying new approaches to things that might have been a bit "under-served" in years past...

Our work is cut out for us in the brackish world, for sure.

Yet, this is so damn fun.

Stay fascinated. Stay bold. Stay diligent. Stay creative. Stay observant...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Startup and beyond...

There is something exciting about the earliest days of an aquarium, isn't there? After the initial "construction" work is done, there is that time when you sort of look back and allow the "dust to settle..."

And that's just the very beginning...

The "startup phase" is NOT those first hours after you fire up the tank. Nope- it's a much longer affair...Like, maybe the first 6 weeks or so of the aquarium's existence. Yeah, these are the critical parts of the "startup" of an aquarium.

I mean, there is a LOT of change that happens in a brand new tank over the first six weeks of its existence!

That's not to say that the very first moments of a new tank aren't the most exciting and even challenging, of course. There are problems to solve, adjustments to make, and observations to note.

I find the most "stressful" part of setting up a new aquarium to be those initial 24 hours after you set it up. You know, that time when the focus is on making sure that everything is up and running fine. It's also an "educational" time for you as a hobbyist, when you can sort of familiarize yourself with the way your aquarium operates.

It's a time when you learn to "read" your new tank...to recognize every sound the tank makes...to know what is a "normal" sound versus one that you don't want to hear. It's a time to make sure that the operating level of the water is optimal. A time to "dial in" your heater, pumps, etc.

And we tend to obsess over our tanks at this time, don't we?

Okay, at least I know that I do!

You know, making sure everything is running correctly- that tank isn't leaking...A time to make sure that the plumbing connections are tight, light and heater settings are correct, etc.

But that's just the "mechanics" of your aquarium.

Getting those things buttoned up is important...And then the fun really begins.

You know, making the tank come alive.

Bringing it from a clean, dry,"static display" to a living, breathing microcosm, filled with life. This, to me is the most exciting part!

And how do we usually do it? I mean, for many hobbyists, we've been more or less indoctrinated to clean the sand, age water, add wood, arrange plants, and add fishes. And that works, of course. It's the basic "formula" we've used for over a century.

And it works...

Yet, I'm surprised how we as a hobby have managed to turn what to me is one of the most inspiring, fascinating, and important parts of our aquarium hobby journey into what is more-or-less a "checklist" to be run through- an "obstacle", really- to our ultimate enjoyment of our aquarium.

When you think about it, setting the stage for life in our aquariums is the SINGLE most important thing that we do. If we utilize a different mind set, and deploy a lot more patience for the process, we start to look at it a bit differently.

I mean, sure, you want to rinse sand as clean as possible. You want make sure that you have a piece of wood that's been soaked for a while, and..

Wait, DO you?

I mean, sure, if you don't rinse your sand carefully, you'll get some cloudy water for weeks...no argument there.

And if you don't clean your driftwood carefully, you're liable to have some soil or other "dirt" get into your system, and more tannins being released, which leads to...well, what does it lead to?

I mean, an aquarium is not a "sterile" habitat.

The natural aquatic habits, although comprised of many millions times the volumes of water that we have in our tanks- are typically not "pristine"- right? I mean, soils from terrestrial geologic activity carry with them decomposing matter, leaves, etc, all of which impact the chemistry, oxygen-carrying capacity, biological activity, and of course, the visual appearance of the water.

And that's kind of what our whole botanical-style aquarium adventure is all about- utilizing the "imperfect" nature of the materials at our disposal, and fostering and appreciating the natural interactions which take place in aquatic habitats. Understanding that descriptors such as "crystal clear" and "pristine" only apply to some aquatic habitats, and that there is real beauty in all types of aquatic habitats.

Indeed, the real "magic", in many instances, occurs in the more murky, turbid, not-so-crystal-clear waters of the world. And if we understand and accept this, we're likely to start our aquariums with a bit less concern over absolute sterile perfection.

We can embrace the mindset that every leaf, every piece of wood, every bit of substrate in our aquariums is actually a sort of "catalyst" for sparking biodiversity and yes- a new view of aesthetics in our aquariums.

I'm not saying that we should NOT rinse sand, or soak wood before adding it to our tanks. What I AM suggesting is that we don't "lose our shit" if our water gets a little bit turbid or there is a bit of botanical detritus accumulating on the substrate. And guess what? We don't have to start a tank with brand new, right-from-the-bag substrate.

Of course not.

We can utilize some old substrate from another tank (we have done this as a hobby for years for the purpose of "jump starting bacterial growth) for the purpose of providing a different aesthetic as well.

And, you can/should take it further: Use that slightly algal-covered piece of driftwood or rock in our brand new tank...This gives a more "broken-in look", and helps foster a habitat more favorable to the growth of the microorganisms, fungi, and other creatures which comprise an important part of our closed aquarium ecosystems.

In fact, in a botanical-style aquarium, facilitating the rapid growth of such biotia is foundational.

It's okay for your tank to look a bit "worn" right from the start.

In fact, I think most of us actually would prefer that! It's okay to embrace this. From a functional AND aesthetic standpoint. Employ good husbandry, careful observation, and common sense when starting and managing your new aquarium.

But don't obsess over "pristine." Especially in those first hours.

The aquarium still has to clear a few metaphorical "hurdles" in order to be a stable environment for life to thrive.

I am operating on the assumption (gulp) that most of us have a basic understanding of the nitrogen cycle and how it impacts our aquariums. However, maybe we don’t all have that understanding. My ramblings have been labeled as “moronic” by at least one “critic” before, however, so it’s no biggie for me as said “moron” to give a very over-simplified review of the “cycling” process in an aquarium, so let’s touch on that for just a moment!

During the "cycling" process, ammonia levels will build and then suddenly decline as the nitrite-forming bacteria multiply in the system. Because nitrate-forming bacteria don't appear until nitrite is available in sufficient quantities to sustain them, nitrite levels climb dramatically as the ammonia is converted, and keep rising as the constantly-available ammonia is converted to nitrite.

Once the nitrate-forming bacteria multiply in sufficient numbers, nitrite levels decrease dramatically, nitrate levels rise, and the tank is considered “fully cycled.”

So, in summary, I suppose that you could correctly label your system “fully cycled” as soon as nitrates are detectible, and when ammonia and nitrite levels are undetectable.

This usually takes anywhere from 10 days to as many as 4-6 weeks, depending on a number of factors. In my experience, there are certainly some “cheats” you can use to speed up the process, such as the addition of some filter media or sand from a healthy, “mature” aquarium, or even utilizing one of the many commercially available “bacteria in a bottle” products to help build populations of beneficial bacterial populations. I hate cheating...but I kind of like some shortcuts on occasion!

So we have at least, for purposes of this discussion, established what we mean in aquarium vernacular by the term “fully cycled.”

With a stabilized nitrogen cycle in place, the real evolution of the aquarium begins. This process is constant, and the actions of Nature in our aquariums facilitate changes.

And our botanical-style systems change constantly.

They change over time in very noticeable ways, as the leaves and botanicals break down and change shape and form. The water will darken. Often, there may be an almost "patina" or haziness to the water along with the tint- the result of dissolving botanical material and perhaps a "bloom" of microorganisms which consume them.

This is perfectly analogous to what you see in the natural habitats of the fishes that we love so much. As the materials present in the flooded forests, ponds, and streams break down, they alter it biologically, chemically, and even physically.

It's something that we as aquarists have to accept in our tanks, which is not always easy for us, right?Decomposition, detritus, biofilms- all that stuff looks, well- different than what we've been told over the years is "proper" for an aquarium. And, it's as much a perception issue as it is a husbandry one. I mean, we're talking about materials from decomposing botanicals and wood, as opposed to uneaten food, fish waste, and such.

What's really cool about this is that, in our community, we aren't seeing hobbyists freak out over some of the aesthetics previously associated with "dirty!"

It's fundamental.

And it's not like we've told ourselves that it's acceptable to not change water, siphon detritus, overstock, or overfeed. Nope. We can still perform excellent regular husbandry routines on botanical-style aquariums. We're still diligent aquarists. And we still might have so-called "dirty" looking water!

And, that's kind of what Nature wants, right?

Always remember that Nature plays by her own rules, developed over eons. When we accept Her rules, embrace Her aesthetics...and make a mental shift to something that the rest of the world might call messy- we can truly appreciate its real beauty.

We have made a collective mental shift. We've evolved, right along with our aquariums.

And it all begins right at the startup.

Stay patient. Stay ambitious. Stay curious. Stay excited. Stay diligent...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Adding to the "knowledge base"

In the aquarium hobby, we see progress in many ways. Sometimes, it's a straight-up breakthrough- like the spawning of a fish once thought impossible. Or, perhaps it's something incrementally more subtle- like figuring out a way to re-create a natural habitat previously ignored by the hobby. Maybe it's even more subtle than that...

The other day, I took a longer-than-usual amount of time to sift through my Instagram feed, which of course, is littered with aquarium people, specifically, those who do aquascaping, biotope aquariums, etc.- stuff that's "right up my alley", as they say.

As I looked at the posts, I saw many amazing things, ranging from the most base ("Buy our product! It's great!") to the work of amazing aquascaper-phlilosopher-types showing a pic of a single rock or twig in a cube-shaped tank, pondering "What's next?"

And it got me thinking.

What IS next?

What's the next thing we're going to do in the hobby?

What's the next "big breakthrough" that will be made? Will it be breeding that previously "impossible" fish? Will it be the creation of a new aquascape that inspires a generation? Or will it simply be a steady progression of many things that make the hobby easier for all of us?

If you look at the "high concept" aquascaping world, it becomes obvious that the "next big thing" is definitely some evolution of the layout of an aquarium. Some different way of arranging rock, wood, and plants in a way that captures both our aesthetic sensibilities and our need to create living art in a way not previously attempted. A way to distill nature into something abstract, yet pragmatic. Perhaps still under Amano's shadow, but searching for its own identity, the aquascaping world moves ever forward.