- Continue Shopping

- Your Cart is Empty

We dream in water.

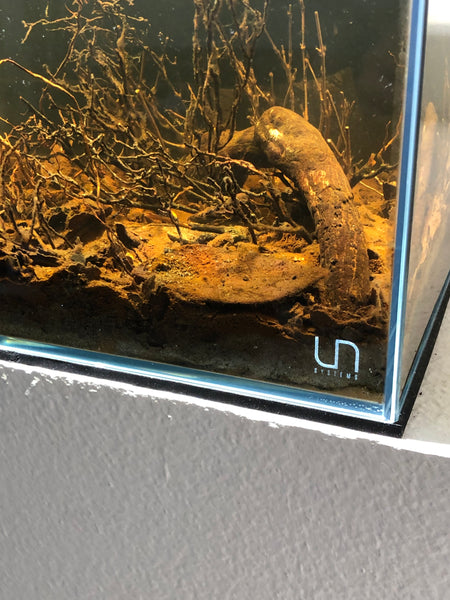

"The name “Tannin” was selected because it’s the substance derived from leaves and wood that tints the life-giving waters of tropical rivers and streams with a beautiful brown color that I find so alluring. The dark waters, tangled roots and earthy-colored leaves found off the shores of tropical “blackwater” rivers, ponds, and streams provide an irresistible subject for hobbyists to replicate in our aquariums..."- From our "About Us" page.

Even though we've been playing with this stuff commercially for about 5 years, as a hobbyist, I've been dabbling with blackwater/botanical-style aquariums for around 18 years...and the hobby itself has been "doing" blackwater tanks for many years. It always amuses me when someone tells us that we "didn't invent this idea.." As if we ever claimed that we did!

Gotta love our hobby culture, huh?

Nature was the "inventor." We just play with her. Follow her lead. Her inspiration.

We dream in water.

Now, I will claim that- perhaps- we "elevated" the art just a little bit; perhaps brought it out of the "darkness" (literally), but we did not invent it.

Regardless of who pioneered blackwater/botanical-style aquariums and when, there are still lots of questions surrounding this stuff. There are still many unknowns, misconceptions, and perhaps even a bit of confusion...We're doing our best to dispel many of these misconceptions, yet it takes time (and hundreds of blog posts and podcasts!) and a global community of active hobbyists to really get the word out more that this is cool stuff!

Often, when I'm asked to speak at a club or event, I'm asked to describe the benefits of the types of aquariums we all love...and that's something you no doubt will receive now and then, so I thought it might make some sense to share with you the summary of the main points I bring up in such situations...

And of course, as you might expect, one of the fundamental questions we receive often here at Tannin is, "What are the advantages of a blackwater-type aquarium, and why would I want to try one?"

It's a really broad, but very logical question, which I can attempt to answer in broad, hopefully logical terms!

In no particular order, here are some of the many reasons why you might want to embrace "The Tint" in your next aquarium:

1) It's different.- Okay, this is probably the most fucking vapid reason for this, but, whatever. But hey...You asked.

Well, anyone can set up a planted tank with clear water, colorful fishes, and natural gravel. It takes an adventurous aquarist to try something truly different- brown water, decomposing leaves, detritus, biofilms...just like in nature! A totally different aesthetic experience than we're used to, which requires definite "mental shifts" in order to embrace and be comfortable with.

It's not just about the aesthetics, of course- but they play a huge role in this stuff.

It's really different.

I remember, during my tenure as co-owner of the coral propagation/import/retail company, Unique Corals, the amusing (to me, anyways) comments I'd get from reefers and marine aquarium experts who came into my office (which, with it's earth tones and wood, looked nothing like what you'd expect from a reef guy, btw) and checked out the "high concept" 20 gallon blackwater tank I had there ( it was no biotope, trust me). Literally, a typical comment was like, "Umm, I think you need to change the water in there...kinda dirty, huh?"

Priceless shit.

Yeah, it's different- and of course, that doesn't define the whole concept, but it does describe it fairly accurately!

2) Many fishes come from "blackwater" habitats, and this a more appropriate environment for them.- Although many fishes, such as Tetras, cichlids, Rasbora, and Discus (a few that come to mind) are bred in typically harder, alkaline "tap water" captive conditions, I personally have yet to see one of these species which doesn't seem to look better, be healthier, and act more naturally in a blackwater environment. We've talked about this idea before, and I still believe it.

Yes, in a tremendous tinge of irony, you need to acclimate these fishes, which have traditionally been kept in more "tap water" conditions in aquairums, to softer, more acidic blackwater conditions slowly, and yes, you need to apply common sense, but I believe that the benefits for your animals will become very evident over time.

There have been some studies, which we've discussed over the years here, which indicated that materials such as catappa leaves do indeed provide some potential anti fungal/antimicrobial benefits because of the compounds they contain, but I would certainly not use this "disease prevention" thing as the sole justification for utilizing botanicals and creating blackwater systems. That is a whole lot of marketing bullshit, IMHO.

Rather, I'd make the argument that, when coupled with good overall husbandry, a well-managed blackwater aquarium can provide environment which is more consistent with that which many of the fishes we keep have evolved to live in over eons, and that this is a generally healthy way to keep them. Humic substances and other compounds released by botanicals are thought by scientists to be essential for the health of many fishes, and in blackwater aquariums, there are significant concentrations of these compounds present at all times.

Our blackwater/botanical-style aquariums cannot be called the "the best option" for many fishes- just a really good option- one worth investigating more!

3) A planted blackwater environment embraces different elements than a traditional planted aquarium does.- We get a lot of interest from hardcore planted aquarium enthusiasts! Over the past year, planted blackwater aquariums are really starting to become a "thing", and that's great! We are seeing more and more amazing planted blackwater aquariums, ranging from artistic to biotope style systems. Obviously, our style of aquarium is a bit different than the typical type of system we'd maintain plants under.

Yeah, you're not able to keep every type of aquatic plant in a blackwater tank. You'd want to research which plants specifically hail from these environments and can adapt and thrive under these conditions. The usual suspects, like Bucephalandra, Cryptocoryne, and various Swords.

There are many others, too.

4) Blackwater tanks lend themselves to amazing hardscapes.- Oh, we're back to the superficial stuff again! But hey, this IS a hobby- and it's supposed to be fun and enjoyable...and this is cool! By virtue of their unique physical attributes, botanical materials such as seed pods, leaves, and stems, can help to create some very interesting aesthetics.

Sure, you can combine them with more "traditional" materials, like wood and stones to create a really unique aesthetic experience for many hobbyists. The ability to express yourself creatively with different elements cannot be overlooked by avid aquascapers!

And, you don't HAVE to keep the water brown, you know!

There are other "intangibles" of experimenting with blackwater/botanical-style aquariums.

First off, a greater understanding of the relationship between fishes and their aquatic environment- both chemically and physically. When you're using materials which are highly "interactive" with their aquatic surroundings, like leaves and botanicals, you can use them to your advantage, and give fishes more of what we like to call "functionally aesthetic" habitats.

You'll want to research this stuff.

And speaking of environments- these types of aquariums will often make you do some research before you set one up...You know, like looking at an actual natural habitat instead of last month's "Tank of The Month"-a process that opens up your imagination- and increases your awareness about the wild habitats of our fishes, how they evolved, where they are, and the threats they face to their existence.

"Big picture" stuff... The biotope aquarium crowd knows this already; it's good that more people come to the party.

It's a big world out there...and not necessarily one that looks the way we might expect.

There are endless possibilities to research.

5) Blackwater/botanical-style aquariums almost force us to deploy patience.- This is a huge thing, as we discussed yesterday. Good stuff in aquariums never happens quickly- especially in botanical-influenced systems, where the seed pods, leaves, and other materials break down over time.

They are almost "ephemeral" in existence, gradually imparting organics, tannins, and other compounds into the water. It requires time, patience, monitoring, and attention to allow one of these systems to "evolve" to its full potential.

You can't rush it. Mind set shifts are essential.

6) You'll be in on the ground floor of a "New Botanical" movement.- Sure, people have played with seed pods, wood and leaves before, but I don't think with the mindset that we've seen lately. In other words, hobbyists who incorporate botanicals and such into their aquarium nowadays are looking at things more "holistically', embracing the natural processes, such as the breakdown of materials, accumulation of biofilms, and even the occasional spot of algae, as part of the environment to be studied and enjoyed, rather than to be loathed, feared and removed.

You'll want to experiment with the idea of volving systems to represent seasonal dynamics, niche habitats, etc. Stuff that pushes the boundaries of what is normally done in the hobby.

We're learning more about the interactions between our fishes and these unique environments, and the opportunities to share this new knowledge are endless! New types of environmental simulation are possible, with new secrets to learn!

I could probably go on for hours (I HAVE, by the way!) talking up the key "takeaways" from blackwater/botanical-style aquariums...and more natural aquariums in general. However, I think the "benefits" can best be understood by simply creating one and enjoying it; learning from Nature in an unedited manner. Watching it evolve, as it's done for eons, without over-extending our management based on "hobby-standard"purely aesthetic considerations.

We'll continue our mission of inspiring, educating, and prodding you when necessary, to take the plunge and move into new directions.

At Tannin, we've done our best to aggregate many different natural materials for you to work with to create unique biotope-inspired displays. We're constantly researching, refining, and tweaking our offering to help you enjoy different aquatic experiences!

Okay, that's the most cursory, quick list of some of the reasons why blackwater, botanical-style systems are something we feel you should be playing with in an aquarium.

Since so many of you are new here, it seems like as good a time as any to cover this stuff today!

Hopefully, this will be enough to kick you over the edge to get started...or to use as a "track" to run on to inspire others!

The endless opportunities for experimentation, creativity, expression, and education are just a few of the wonderful benefits that we will enjoy as we continue to open our eyes- and minds- to a new and very different approach to aquarium keeping.

Yeah, we dream in water.

Join us.

Stay inspired. Stay creative. Stay open-minded. Stay observant. Stay patient. Stay enthralled!

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

"Extended operations...."

Hard to believe, but we're closing in on 5 years of operations here at Tannin Aquatics! Five years of sharing our vision of the botanical-style natural aquarium. Five years of talking about unusual ways to replicate the form and function of Nature in our tanks...Many of you have been with us right from the beginning. And quite a few of you were experimenting with botanicals and such in aquariums even before we emerged as a company!

Like us, you've been drawn to this alluring world of tinted water, decomposing leaves, and biological complexity...

The practice has begun to emerge from the shadows, shaking the stigma of "side show"; with you losing your "daredevil" status as a fish geek for trying a botanical-style tank as it moves into the main stream of the hobby.

One of the questions that were starting to see more of as we evolve in the blackwater, botanical aquarium specialty is, "What are the long-term implications for maintaining such tanks?" (okay, it's not always worded that succinctly, lol). Hobbyists are interested in how these systems function in the long term, specifically in regards to nutrient control and export processes...

Now, this is an area of great interest to me, as well.

Over the many years that I've been expert,ending with and managing blackwater, botanical-style tanks, I've placed a lot of emphasis on water quality and environmental consistency. Now, on first glance, the visual impression you'd get from our practice is that these are "dirty", organic-heavy systems, with high levels of nitrates, phosphates, and dissolved organic compounds...Systems "teetering on the edge", if you will.

And I suppose that's partially because of the very appearance of these tanks- filled with decomposing leaves, seed pods, accumulating biofilms, embracing detritus, etc. Oh, and that dark brown, tannin-stained water! On the surface, the uninitiated could easily conclude that you're playing with all of the ingredients for a potential disaster.

How long do you keep your botanical-style aquariums up and running?

A few months? A year? Several years?

As self-appointed "thought leaders" of the botanical-style natural aquarium movement, we spend an enormous amount of time talking about how to select botanicals, prepare them, and utilize them in aquariums. We talk about what happens when you place these terrestrial materials in water, and how botanical-style aquariums "evolve" over time...

All well and good...

However, we've probably talked a lot less about the idea of keeping these aquariums over the very long term.

And, I'd define "very long-term" as a year or more.

I mean, this makes a lot of sense, because botanical-style tanks, in my opinion, don't even really hit their "stride" for at least 3-6 months. Yet, in the content-driven, Instagram-fueled, postmodern aquarium world, I know that we tend to show new looks fairly often, to give you lots of ideas and inspiration to embark on your own journeys.

And I suppose, that's a very cool thing. Yet, it's likely a "double-edged sword."

Like so many things in the social media representation of today's aquarium world likely gives the (incorrect) impression that these tanks are sort of "pop-ups", set up for a photography session and broken down quickly. We are, regrettably, likely contributors to some of this misconception.

I think we, as those "thought leaders", need to do more to share the process of establishing, evolving, and maintaining a botanical-style aquarium over the long term. To that end, we're going to do a lot more documentation of the entire process in months to come- documenting the journey from "new" to "mature"-sharing the ups, downs, and processes along the way.

Regrettably, the way this work is often presented on social media, it likely enables us to project our human impatience and desire or instant gratification on living creatures, which, in my opinion, is sort of the opposite of Nature's "timetable." She does things in a time and manner that are best suited for the creatures who reside in the natural world. There is no need or reason to conform to our timetable to get the aquarium cycled and stable "this weekend."

Besides, if the goal is to keep an aquarium functioning for the longest period of time, what's the rush to get it stabilized?

Patience, as always, is the key ingredient here.

Like with most types of aquariums, I don't think that there is an "upper limit" to how long you can keep a botanical-style aquarium up and running. It's predicated upon our ability to stick to a mindset...

The longest I've personally maintained such a system continuously has been about 5.5 years, and the only reason I broke down that aquarium was because of a home remodel that required the removal of everything from the space in which the aquarium was located. I set it up again shortly after the work was completed, keeping the substrate intact during the "move."

The reality, though, is that I could have kept this system going indefinitely.

And the interesting thing about these tanks is that they run very, very well for extended periods of time, with simple, time-honored husbandry practices and mindsets.

As most of you who work with these aquariums know, the key to long-term success with them is to go slowly, deploying massive amounts of patience, common-sense husbandry, monitoring of environmental parameters, and careful stocking management. Not really much different from what you'd need to do to successfully maintain ANY type of aquarium for the long haul.

As we've discussed many times, for the longest time, there seemed to have been a perception among the mainstream aquarium hobby that botanical-style blackwater aquariums were delicate, tricky-to-maintain systems, fraught with potential disaster; a soft-water, acidic environment which could slip precipitously into some sort of environmental "free fall" without warning.

A scary and undeserved attribute ascribed to these tanks.

Most of us who have played with these types of aquariums have seen the exact opposite: Minimal, if any- detectible nitrates, phosphate, and remarkably stable pH values.

The reality is that, one the tank is "set"- that is, once you're done with the initial adding of lots of botanicals, and wood, and leaves and such...Like any tank, these tanks seem to "find" some sort of equilibrium. I've said it many times and I think that it needs repeating: In my opinion, blackwater, botanical-style aquariums are no more difficult or "dangerous" to maintain than any other type of aquarium we work with. They simply have different "operating parameters", which, one you learn, create stable, long-term viable systems.

There are always "warnings" that we receive from hobbyists about the "dangers" of flirting with materials which can lower the pH of our tanks under certain conditions. The so-called pH "crashes"- which I personally, in over 23 years of playing with this type of tank- have never seen. I just haven't. I know that's a big concern for a lot of people- and I won't downplay it or dismiss it. However, the reality is that I personally- nor none of my close friends who play with these kinds of systems- have ever experienced this.

Are we lucky?

Maybe.

Do we practice overall good aquarium husbandry?

Yes.

That means we do water exchanges. Like, 10% or more weekly. Every damn week. With the same kind of water (RO/DI). We clean/replace filter socks, pads, or any other media that we use. We don't feed recklessly. We don't overstock. We monitor basic water parameters weekly. We properly prepare and replace botanicals gradually and regularly.

Put is in for medals, right?

I mean, just because we do it with relatives ease and success doesn't mean that this is a piece of cake or anything. I get that. My point was not to "humble brag" or anything. Rather, it was to remind you that if a guy like me can be successful with this stuff, hobbyists with serious skill like you can REALLY be successful!

However, it should give you some comfort knowing that, in addition to just myself an a few friends, hobbyists worldwide are playing with botanical-laden systems without "anomalous" crashes and disasters. Can bad stuff happen? Sure. The most common "disasters" we've seen have been by adding too many botanicals too quickly, resulting in excessive bacterial respiration- which, in turn, likely lowered the water's dissolved oxygen and increased CO2 levels rapidly to a dangerous rate. These effects happen at the same time and can lead to fishes gasping for oxygen at the surface- or worse.

But that's the extent of the "bad" that I've seen.

The idea of a pH "crash" is possible, I am sure...but I think it's largely avoidable, much like the CO2 increase. A pH "crash" is when the pH suddenly (and unintentionally) drops because of the release of acid into water with little or no buffering capacity...this can be dramatic and quick...But I think, once again, it would be caused because of our own actions- intentional or otherwise...Not something that is inherently "on standby" in a blackwater, botanical-style aquarium. Sure, we work with materials that can affect the pH..but it's not a ticking time bomb, if you add materials logically and slowly.

Observation and patience are keys.

Now, I am not a chemist, and I'll be the first to admit that what I'm using to justify my position is largely anecdotal, based largely on my operating many such systems over the years. I have not done rigorous controlled experiments on this stuff. That being said, I'd welcome those with the interest and knowledge to conduct some cool experiments to see what we can learn! I am really of the opinion that WE as hobbyists are the causative factor of many of these "anomalous" events in our aquariums. They can almost always be traced back to some action which triggered the event...

If your continuously adding materials which drive down the pH in your tank, and if it has insufficient buffering capacity- the pH will drop. How rapidly? Well, I couldn't' tell you. But I believe such "crashes" are quick, immediate responses to some causative factors. And I think they can be remedied equally as quickly. There is a lot of this stuff on hobby forums about working with pH, and quite frankly, I find it a bit too complex and tedious to understand and explain, so I recommend doing a "deep dive" on this stuff if it is a concern. There is great information by well-qualified hobbyist/scientists on this stuff. Look for it.

It's out there!

What happens over time?

Well, typically, as most of you who've played with this stuff know, the botanicals will begin to soften and break down over a period of several weeks. Botanical materials are the very definition of the word "ephemeral." Nothing lasts forever, and botanicals are no exception! Pretty much everything we utilize- from Guava leaves to Melostoma roots- starts to soften and break down over time. Most of these materials should be viewed as"consumables"- meaning that you'll need to replace them over time to keep the desired results consistent.

Oh, and sure, botanicals will go through that "biofilm phase" before ultimately breaking down, and you'll have many opportunities to remove them...Or, in the case of most hobbyists these days- add new materials as the old ones break down...completely analogous to natural "leaf drop" which occurs in streams, rivers, and flooded forests throughout the tropical world.

And of course, this always prompts the next question: "Do I leave my botanicals in the tank until they completely break down, or do I remove them?"

My advice: Leave 'em in.

I personally have never had any negative side effects that we could attribute to leaving botanicals to completely break down in an otherwise healthy, well-managed aquarium. Yeah, it will produce pieces broken-down botanical materials and...detritus.

Well, you know how I feel about detritus.

Many, many users (present company included) see no detectable increases in nitrate or phosphate as a result of this practice. Of course, this has prompted me to postulate that perhaps they form a sort of natural "biological filtration media" and actually foster some dentritifcation, etc. I have no scientific evidence to back up this theory, of course (like most of my theories, lol), other than my results, but I think there might be a grain of truth here!

I believe that the "microbiome" of a botanical-style tank, complete with fungal growths, biofilms, and decomposing leaves, is extremely diverse, and potentially quite beneficial for the resident fishes as a supplemental food production "facility" as well. My experiments with abstaining from feeding a leaf-litter-dominant tank for many months validated this.

Now, of course, you are dealing with a tank filled with decomposing botanical materials, so you need to stay on top of stuff. Our embrace of natural processes aren't about simply abandoning all well-established aquarium husbandry practices. Botanical-style aquariums aren't just "set and forget." Good overall husbandry is necessary to keep your tank stable and healthy- and that includes the dreaded (by many, that is) regular water exchanges.

I know, I keep going back to this.

As we pointed out, at the very least, you'll likely be cleaning and/or replacing pre filter media as part of your routine, and that's typically a weekly-to bi-weekly thing. Part of the art and science of botanical-style aquarium-keeping is the idea of developing consistency, and understanding what to expect over the long term, as outlined above.

And yes- one of the most important behavioral characteristics I think we can have in this hobby, besides patience, is consistency.

Just sort of "goes with the territory" here.

This is where those who don't understand these types of aquariums get it all wrong and really "short-sell" this stuff... It's about understanding and processing what's happening in the little aquatic ecosystem you've created. It's about asking questions, modifying technique, and, yeah, playing hunches- all skills that we as hobbyists have practiced for generations.

When you distill it all- we're still just "keeping an aquarium"- yet, one that I feel is a far more natural, dynamic, and potentially game-changing style for the hobby.

One that we need no longer be afraid of.

One that's perfectly equipped for "extended operations."

Stay engaged. Stay thoughtful. Stay patient! Stay focused. Stay curious. Stay dedicated...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

The never-ending nuances of niches!

Like all of you, I must have a thousand aquarium ideas at any one time; 950 of which I'll never get to. Yet, that's kind of part of the fun of all of this...scheming and thinking...and ultimately, doing!

And one of the things I've played with a lot in recent years is the art of "nuance" in my tanks...

In other words, going deeper than just the superficial or "big picture" of aquarium configuration. I like the idea of creating "niche micro-habitats" within aquariums; locales based around a specific feature within the system, which add an entirely new set of physical parameters to the overall tank.

As someone who's kept so-called "community tanks" forever, I can certainly appreciate the challenge and the allure of keeping multiple fish species together in one aquarium. And I know most of you can, too.

It's interesting to me that in the last decade or so, the hobby concept of a "community aquarium" has sort of evolved from, "A collection of different kinds of cool fishes I like from all over the world, living in one tank"- you know, a "buffet" of fishy favorites, to more of a "curated" collection of fishes that might be found in the same general habitat and location...or even in the exact location...or more specific than that! Stuff as finely nuanced as "wet" or "dry" season!

The idea of playing with niche habitats is nothing new, really. I think the shift really started with the rise in popularity of African Rift Lake cichlids. I mean, sure you could keep fishes from different lakes together, but when we collectively learned that each lake not only harbors different fish species, but offers unique environmental parameters and niches that the resident fishes have evolved to live in (like Lake Tanganyikan shell-dwellers, for example), it became more obvious that some degree of specialization was required.

And then we began in earnest to keep species like Rainbowfishes and killifishes, which had distinct genetic "races" or populations from various locales that would hybridize if mixed, throwing the already muddled taxonomy and genetics of these fishes into an even greater morass of confusion was definitely something to avoid.

And then there are the Apistogramma...Yeah, the South American "version" of African killies...Just plain trouble, from a speciation standpoint, if you mix males and female of different varieties in the same tank. Again, a situation that requires a certain degree of discipline on our part, right?

Sure, there are like a thousand more examples we could beat the shit out of to make our case, but I think you're getting the idea: Our idea of a "community tank" has sort of evolved with our knowledge of fishes- and I think that's a good thing.

Nowadays, althogh you have "South American"-themed community tanks, "Asian"-themed community tanks, etc., they're more nuanced...Typically centered around regional fishes found in a specific habitat or environmental niche...It's not just, "Hey, that fish is from Thailand...So is THAT one! And THAT ONE, too!"

A shift.

What's most profound about this shift, in my humble opinion, is that it's enabled us to study more closely- and replicate more closely- the unique environments from which our fave fishes hail. And that leads to a greater understanding of both the fishes and their habitats.

And this is where my interest comes in...

It's entirely realistic, comfortable, and simply "normal" for many of the fishes we play with in aquariums to be kept in close quarters with other species. In one field study of forest streams in the Rio Negro in Brazil (you knew I'd go back there, right?), it was noted that there were up to 20 different species present, all living in close proximity to each other, within distinct niches within the habitat. The population density was an astounding 100 individuals per cubic meter!

That's a lot of fishes! And, with a bunch of niches for them to inhabit- a lot of possibilities...

And the takeaway here isn't that you should pack the hell out of your community tank because some stream in the jungle has a lot of fishes living in a small area of space.

No.

The real takeaway is the fact that the study indicated a significant number of species in that relatively small space, living in different niches within the habitat!

This is where things get real interesting, in my opinion, because even in my beloved blackwater streams, you have multiple niches in which fishes live their entire lives, obtain nutrition, protection, and find spawning locations.

The implications for our botanical-style aquariums are manifold...

In our own aquariums, we've seen fishes like Plecos and other catfishes inhabiting and interacting with all sorts of botanical materials, much like they do in the wild.

Taking advantage of physical spaces within the greater habitat.

We've seen fishes like Badis, loaches, even wild Betta species living under a canopy of leaves and other botanicals. A variety of fishes living in all sorts of little niches within the botanical scape, exploiting the cover and foraging opportunities that they offer.

This is very cool.

This is profound.

In our aquariums set up in a more natural style (in both form and function) the fishes are "sorting things out for themselves" and inhabiting the little niches that they would in the wild. We have great information about these environments, photos of the physical structures found within them, and detailed studies on populations inhabiting these niches.

With terrific access to incredible natural materials and a greater understanding the overall chemical and structural makeup of these habitats, we are able to replicate them as never before!

We're creating aquariums that deliberately foster the development of smaller environmental niches within the greater aquarium structure.

I've spoken with hobbyists attempting to create deep leaf litter beds for specialized catfishes and so-called "Darter Characins", tanks with varied, rich substrate composition to accommodate loaches, tangles of roots for Tetras, etc.

Perhaps most exciting, we're developing more modern interpretations of the "community aquarium", intentionally layering, populating, and optimizing several "microhabitats" within the same tank.

Huge.

What new understanding will we gain by creating these deliberate configurations within our aquariums? What newfound successes will we have with previously temperamental fishes? What reproductive secrets will we unlock- all by providing more faithful representations of the communities and micro niches from which they come?

The mind boggles!

In today's hobby, it's no longer "good enough" for many specialty fish enthusiasts to simply toss in a PVC pipe section for a "cave", or a "Texas Holy Rock" as a hiding or spawning locale for that Pleco or cichlid. For the first time, we are seeing hobbyists really utilize botanical materials from specific geographical regions.

Not simply to satisfy a judge in some snobby aquascaping contest, but to determine if there are advantages for our fishes that may be gained by using the actual materials that are found in a specific region!

For many, the idea of replicating more realistically the environmental niches that these fishes inhabit in the wild is more compelling, fascinating, and proving to be more successful than ever before.

We're at a very special time in the aquatic hobby.

A time when information, technology, technique, communication, and creativity are all intersecting, equipping us with all of the tools- both metaphorically and physically-that we need to create aquariums that may surpass anything we've done in the past, in both form and function.

By studying and sharing information and experiences about the unique niche habitats that many of our fishes come from, we're accelerating the pace of these breakthroughs and discoveries, and maybe- just maybe- further reducing our reliance on wild-collection of some species from their fragile ecosystems, preserving them for future generations to enjoy.

Yeah, there are still great "community tanks" to be made! And there are nuances, niches, and ideas to test and explore...These will drive many of the next innovations in the hobby.

Stay thoughtful. Stay innovative. Stay creative. Stay resourceful. Stay observant...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics.

We make stuff complicated...

After a lifetime in the aquarium hobby, I think I've reached a conclusion:

As fish geeks, we go to great lengths to make stuff more complex, more comprehensive- more difficult than it has to be.

I think I might be like a lot of aquarists…I tend to dwell on really obscure minutiae. I mean, stuff that really, in the grand scheme of things, may not be that important.

And I make simple stuff really complicated.

Details.

Although my lack of ability (or desire) to do really detailed work has always been a sort of "problem" for me in some parts of my life, in the aquarium world, for some reason details are like, really important to me!

What a strange contrast with my working life!

I recall back in college, I was fortunate enough to land an internship in one of the hottest advertising agencies in Los Angeles- or the world, for that matter, at the time. As an intern, I spent time in a few different departments, even though I was “hired” for my alleged copywriting skills.

One of the departments I was relegated to during my internship was called the “Traffic” department (yeah, even the name sounded challenging), where all of the media buying, scheduling, and seemingly mundane (to a wannabe young copywriter, anyways) and intricately detailed work was done.

Translation- boring shit. I remember “serving my time" in that department (yeah, that’s what my fellow interns and I called it) under a pretty crochety old advertising exec, who sort of loved and hated me at once. Loved my New Wave styling, but thought I was a bit "out there" in the idea department...She’d dispense the occasional nugget of old-school ad-biz wisdom, followed by a verbal “bitch slap” for failing to follow her byzantine manual record-keeping system.

Yet, one of the best pieces of advice I'd ever received in the industry was from her: “Don’t ever work in this department..you tend to get lost in the details…It's not you.”

I never forgot that, BTW. I never do ridiculously detailed work...at least not well. And it was a true summation of me as an aquatic hobbyist, too! Who would have known?

Fast forward some decades...

A couple of years back, I was working on what was probably the simplest reef tank I’ve ever worked on, my Innovative Marine “Fusion Lagoon 50”- an "all-in-one" tank- my “Everyman’s Reef Tank…”

It's turnkey. Off the shelf. All in one. Simple. Unbox it. Fill it up. Plug it in. Easy.

I love this tank.

Yet, I am a reefer at heart. And reefers love to fuck with stuff. Just because. We can't leave "good enough" alone. We have to modify.

Not wanting to keep it totally “stock”, and being the ridiculous aquarium dork that I am, I decided to change out the more-than-capable, yet generic main system pump on this all-in-one tank for a sexy, high-end DC pump..Yeah, when you have friends like I do challenging you daily- you’re simply enabled to tweak stuff…These guys, like most aquarists, myself included- operate on two basic premises:

1) Why keep it stock when you can modify the shit out of something "just because?"

2) You should be able to put something together and get it working without referring to the instructions.

So, carrying on the time honored aquarium-keeping tradition of making the simple ridiculous, and being susceptible to manipulation by my reef-keeping buddies- I plotted and schemed...

I remember thinking to myself, "This should be easy..."

That was the first sign of trouble, familiar though it was.

And of course, the connections on the return were totally different than those on the outlet to the pump, and I don’t want to start drilling out bulkheads and such..so I needed to get some more plumbing parts to adapt this "square peg into a round hole", as they say.

Some $40.00 in fittings, and two weeks later (because I had to order obscure parts from multiple places- a couple of times- to find the right ones), there we were- an overbuilt, needlessly complicated, decidedly ridiculous monument to fish geek absurdity!

The simple, off-the-shelf-solution. Easy. It works for 99% of consumers just fine.

The fish geek's "solution." Absurd. Complicated...Gnarly!!

And of course, I was just getting started with that stuff! After the modification, it turned out that the rubber feet on the DC pump transmitted a little noise, so I devised a way to line the bottom of the filter compartment with some kind of mousepad material…

One "simple" solution led to another "simple" problem...it went on and on.

Arrghh.

Okay, you get it. And I haven’t even talked to you about my dilemma with selecting a dosing system…

A dosing system? Me? Scott-fucking-Fellman? Mr. "Just-feed-your-corals-with-a syring-and-do-regular-water-exchanges-to-impart-trace-elements..." Why?

Yup.

It’s the fish geek's curse.

You're in this game long enough, you just want to do everything some other way, right? Possibly, even the “hard way”, right? And again, I think it’s a product of our “culture” in the hobby.

I mean, I didn't just start an aquarium supply company...no, I had to start a company that literally sells "twigs and nuts" for the expressed purpose of turning your tank water brown and manipulating the environment...And I had to create a whole "ecosystem" of technique, best practices, instructions, and infrastructure around it...I mean, couldn't I have just sold activated carbon, filter pads, and fish food and called it a day?

Yeah...

Another phenomenon which occurs a lot in our wold- and I swear every time I start a project that "this won't/can't happen to me this time"- but it does. (And I know literally a half dozen aquarists who did this): You start working on a cool system, accumulating gear, parts, and big ideas...Suddenly, three months into the project, you completely abandon it for a scaled-up, three-times-as-complicated, twice as expensive mega tank.

Sound familiar? Done this before? If not, you at least know a fish geek who has. Guaranteed.

The so-called "Aquarist's Curse", indeed.

Yet, the reality is that for some hobbyists, it’s a big part of what they love: Setting up aquarium automation, designing and building complex auto top-off systems, wavemakers, plant food dosers, etc. Yeah, a lot of people just love that stuff…And part of me totally gets that. I mean, yeah, I’m a lot more interested in watching my fish, plants, and coral and seeing them thrive and grow than I am at setting up 43 different lighting settings from my iPhone, but I really can’t really fault those who do.

I mean, where would we be in the hobby without these bold experimental types? Besides, I love trying to adapt 6 plumbing parts to do the work of 2.

Although I know my limits...I think.

I’m almost operating "at capacity" when just setting up my lighting (don’t even get me started- that’s a whole different topic for another day..). Regardless of my challenges, I’ll occasionally come up with an idea just hair-brained enough to be considered rather "intelligent" (notice I didn’t use “brilliant” in any way, shape, or form..?).

Of course, these "ideas" generally involve the unintended expenditure of large quantities of money and time.

(The best-laid aquatic plans...require $$$.)

I just find that, as hobbyists, we tend to get really into intricate detail on like…well, EVERYTHING! Like, we can’t just feed our fishes and manually fertilize our plants? We have to utilize automatic feeding and dosing systems. We can’t just put a siphon hose in the tank like our grandparents did..nope- we need to develop an automated water changing system, which makes an easy task more complicated by adding in the risk of technical failure (you think that spilling a little water on your feet with a siphon hose sucks, imagine draining your whole tank..into your garage or basement…I know at least two people who managed to accomplish this with their fancy systems…amazing insurance claims)!

You can almost hear the reptile guys taunting us: "How many fish geeks does it take to change a light bulb?"

None, you heathens- we use fully controllable LED's! Gety our asses out of the Dark Ages!

Yeah, we make stuff complicated.

Why use flex tubing, man? Pipe is so much sexier and more permanent."

It's definitely the "Aquarist's Curse."

We make stuff complicated- perhaps way more than it ever needed to be.

I've got it.

You've got it.

And, quite frankly, if you say you don't, you're lying. Because you own an aquarium, not a goldfish bowl. Yeah, by virtue of the fact that you own an aquarium, you've you've submitted yourself to this absurd condition.

So, I guess it's not really that bad.

In fact, it's actually kind of cool. It's what makes this hobby so damn fun.

I'm looking forward to sharing the many absurdities of what should be a really simple, scaled-up version of my Mangrove tank build this fall.

Simple.

Right?

Well, toss that thought out the window. I have to figure out how I'm gonna hang my lighting system now...

Time for a confession...tell me you're cursed...admit it. Embrace it.

Share your stories.

Laugh at yourself. Love yourself, your community, and what you do.

You're cursed, yeah. But you're not alone. You're an aquarist.

We make stuff complicated.

Stay focused. Stay challenged. Stay complicated...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Staying the course.

The aquarium hobby emphasizes a lot of good, solid practices. However, one of things we hear discussed the least is the mindset of acquiring patience. Yeah, good, old patience. It's the most fundamental of the fundamentals in the aquarium hobby. And perhaps the most difficult thing to acquire.

People new to our little hobby sector often ask me, "When will my tank start looking more "broken in'?", or, "When can I add more fishes?", or, "When will the tank look more established?"

My answer to these kinds of questions is always the same: It takes a while. Botanical-style tanks, like any other, require biological processes to establish and "mature" the system. This takes more than a week, or two weeks- or even a month. Honestly, if you asked me, you're talking three to four months before any aquarium- especially a botanical-style one- hits that "stride" of stability and the "look" that comes from a more mature, established system.

Three to four months.

Like, one season.

Can you handle that?

I mean, it's really not that long, right? Especially when you take into account that you can maintain a botanical-style aquarium continuously for years.

It just requires patience, a long-term vision, and a focus on the goal of establishing a healthy, naturally-functioning system over the long term. You can't rush stuff. You simply can't. And you really don't want to, anyways. Let it evolve naturally.

Stay the course.

Be patient.

One day, you'll look at your tank, and think to yourself, "THIS is what I envisioned!" And you might casually glance at the calendar and note that, sure enough- it's been about 3-4 months since you established your tank.

Not all that long, right?

It was a pretty enjoyable ride along the way, wasn't it? Yeah, when you liberate yourself from some artificially self-imposed timetable about "when" things will look/feel good, it's a lot easier.

And it all comes back to understanding and embracing the fundamentals.

I firmly believe that understanding and appreciating the fundamentals of the hobby- and the natural world- can yield the same results- or better- than tons of expensive gear and "stuff" when simply "thrown" at the situation without thought as to why..

It requires us to shift our minds to places that might be less comfortable for us...

It just is a lot less sexy than "gearing up" or blindly following someone else's "rules"- it requires us to open our minds up...It requires patience, process and personal observation. It requires eschewing more "instant" result for long-term function, stability, and benefits.

That mental shift is something, isn't it?

I think the pendulum is swinging back a bit. Not "digressing", mind you. Just switching back to a more accepting approach; taking our hands off...just a bit. Once again realizing that Nature knows best. Understanding that we can use technology and technique to work with Nature.

We're realizing that Nature has been doing this stuff for billions of years longer than we have, and She has some damn good ideas on how to run things!

Rather than fighting processes like decomposition, formation of detritus, and biological diversity, we seem to be spending much more energy setting the stage for natural processes to occur.

And our fishes and other aquatic animals are really benefiting from this. Fish health, appearance, overall vivaciousness, and spawning activity are being positively impacted by the concept of working with Nature in this manner.

Once again, just as aquarists did since the dawn of the modern age of fish keeping, we've been thinking of an aquarium as a place to grow stuff- and we're looking at the whole aquarium as a "microcosm" of Nature.

A living, breathing, growing entity.

"Growing."

I saw a sort of "compressed" version of this century-long evolution of freshwater aquaristics during the rise of the reef aquarium hobby, which really started to take off in the mid 1980's. My mind has been on this "side of the fence" quite a bit lately, as I'm going to be speaking at a reef club in a few weeks. It got me reflecting about this stuff...

For the longest time, in the reef hobby, we were happy to just keep a box full of fishes and maybe a few tough invertebrates alive. Then, we evolved up to trying to house them long term, and propagate them.

Experiments with new technology and technique resulted in the birth of the modern reef system, with robust filtration, lighting, and studious analysis of water chemistry. The emphasis was on providing a great environment for the corals and inverts, so that they can thrive and reproduce.

And the learning never stops. The techniques and philosophies continue to evolve...

Within the past 10 years in the reef hobby alone, we've went from a doctrine of "You should have undectable nitrates and phosphates in your reef aquarium because natural reefs are virtual nutrient deserts!" to "You need to have a balance between too much and too little."

We've come to understand that reef aquariums- like any type of aquarium- are truly biological "microcosms", which encompass a vast array of life forms, including not just fishes, corals, and invertebrates, but macro algae, benthic animals (like worms, copepods, and amphipods), planktonic life, and more.

Reefers came to understand- as freshwater pioneers did generations before- that just because a reef has "undetectable" levels of phosphates and nitrates in the waters surrounding it, our aquariums don't have to run that way. The "optimum" environment for our animals might not be exactly what we think it may be on the surface.

The reality in the reef keeping wold is that corals need nutrients and food, and an aquarium is not a natural reef; an open system with uncounted millions of gallons of water passing through it hourly.

We discovered this reality in the coral propagation business, where the long-held aquarium mindset that you need a "nutrient poor" system in order for corals to thrive was not really the whole story. Particularly when we were trying to mass-culture corals on a commercial level.

They needed to eat. Polishing out everything from the water with lots of gear and such was actually detrimental. We allowed some detritus to accumulate in our systems; didn't fear feeding our corals...and they grew.

Like mad.

Reliance on some aspects of Nature is a good thing.

And patience. In droves.

Yet in recent years, with the explosion of gadgets and internet-enabled "hacks", reefkeeping as a hobby has sort of gone a bit the other way- heading into that "technology can do everything" phase that the freshwater world did decades ago, in my opinion. Somehow "saving time" has surpassed applying patience as the underlying "mantra" of that hobby sector.

Yet, I think it's finally starting to break just a bit again. Recently, I've seen some well-known reef keepers having some rather spectacular failures, and I can't help but wonder if at least part of the underlying causes were the hobbyist getting a bit too far away from Nature, and a bit too "cozy" with tech instead! Eschewing patience and measured progress for the promise of instant, tech-provided gratification!

They'll never admit it. However, I think they know better...

Needlessly (IMHO) complicating things in order to foster the same results that can be achieved by embracing natural processes- with a bit less "certainty", though- seems a bit odd to me. ... Positive, even predictable results generally take longer than if you apply all the gadgets, additives, and tech to the process- but Nature will find the way to get where she wants to go- with or without all the gadgets we employ.

We've sort of figured this out in our sector of the hobby.

It just takes patience. And good equipment. In balance.

And patience is often more economical than gear... And the results far more interesting, IMHO!

In these uncertain, unprecedented times in our world history, there is much uncertainty; much concern about when things will get better, and how to make them that way.

The path to success is to apply common sense, with an equal dose of patience and yeah, a certain degree of faith.

Be patient.

Stay strong. Stay

Abandoning "best practices?" Or, embracing a technique?

NEWS FLASH: Not everyone likes the stuff that we do.

I suppose that there are occasional smirks and giggles from some corners of the hobby when they initially see our tanks, with some thinking, "Really? They toss in a few leaves and they think that the resulting sloppiness is "natural", or some evolved aquascaping technique or something?"

Funny thing is that, in reality, it IS a sort of an evolution, isn't it? A little advancement from where we are in the hobby before.

I mean, sure, on the surface, this doesn't seem like much: "Toss botanical materials in aquariums. See what happens." It's not like no one ever did this before. And to make it seem more complicated than it is- to develop or quantify "technique" for it (a true act of human nature, I suppose) is probably a bit humorous.

Yeah, I guess I can see that...

On the other hand, the idea behind this practice is not just to create a cool-looking tank...And, we DO have some "technique" behind this stuff...

And it's not about making excuses for abandoning aquarium "best practices" as some justification for allowing our tanks to look like they do.

We don't embrace the aesthetic of dark water, a bottom covered in decomposing leaves, and the appearance of biofilms and algae on driftwood because it allows us to be more "relaxed" in the care of our tanks, or because we think we're so much smarter than the underwater-diorama-loving, hype-mongering competition aquascaping crowd.

Well, maybe we are? 😆 (I promise to keep dissing these people until they put their vast skills to better use in the hobby...Sorry, lovers of underwater beach seems and "Hobbit forests..".)

I mean, we're doing this stuff for a reason: To create more authentic-looking, natural-functioning aquatic displays for our fishes. To understand and acknowledge that our fishes- and their very existence- is influenced by the habitats in which they have evolved.

We've mentioned ad nauseum here that wild tropical aquatic habitats are influenced greatly by the surrounding geography and flora of their region, which in turn, have considerable influence upon the population of fishes which inhabit them, as well as their life cycle. The simple fact of the matter is, when we add botanical materials to an aquarium and accept what occurs as a result-regardless of wether our intent is just to create a different aesthetic, or perhaps something more- we are to a very real extent replicating the processes and influences that occur in wild aquatic habitats in Nature.

The presence of botanical materials such as leaves in these aquatic habitats is foundational to their existence.

And, understanding why leaves fall, and what happens to the environment when they do, is really important.

In the tropical species of trees, the phenomenon of "leaf drop" is hugely important to the surrounding forest environment. Vital nutrients are typically bound up in the leaves, so a regular release of leaves by the trees helps replenish the minerals and nutrients in the soils which are typically depleted from eons of leaching into the surrounding forests.

And the rapid nutrient depletion, by the way, is why it's not healthy to burn tropical forests- the release of nutrients as a result of fire is so rapid, that the habitat cannot process it, and in essence, the nutrients are lost forever.

Now, interestingly enough, most tropical forest trees are classified as "evergreens", and don't have a specific seasonal leaf drop like the "deciduous" trees than many of us are more familiar with do...Rather, they replace their leaves gradually throughout the year as the leaves age and subsequently fall off the trees.

So, what's the implication here?

There is a more-or-less continuous "supply" of leaves falling off into the jungles and waterways in these habitats, which is why you'll see leaves at varying stages of decomposition in tropical streams. It's also why many leaf litter banks may be almost "permanent" structures within some of these bodies of water!

And, for the fishes and other organisms which live in, around, and above the litter beds, there is a lot of potential food, which varies somewhat between the "wet" and "dry" seasons and their accompanying water levels. The fishes tend to utilize the abundant mud, detritus, and epiphytic materials which accumulate in the leaf litter as food. During the dry seasons, when water levels are lower, this organic layer compensates for the shortage in other food resources.

During the higher water periods, there is a much greater amount of allochthonous input (remember that shit?) from the surrounding terrestrial environment in the form of insects, fruits, and other plant material. I suppose that, in our aquariums, it's pretty much always the "wet season", right? We tend to top off and replace decomposing leaves and botanical more-or-less continuously.

We see leaves as a sort of "consumable" in our hobby sector- materials that you need to replace regularly- much like carbon, food, or filter pads.

Now, of course, where is where I get into what I will call "speculative environmental biology!"

What if we stopped replacing leaves and even lowered water levels or decreased water exchanges in our tanks to correspond to, for example, the Amazonian "dry season" (June to December)? What impacts on the environmental parameters of our tanks would this have? And if you consider that many fishes tend to spawn in the "dry" season, concentrating in the shallow waters, could this have implications for stimulating breeding?

Could this be a re-thinking or re-imagining of how we spawn and rear some of our fishes?

Could all of this playing around with leaves and twigs be more of a "technique" than the hobby has previously thought?

I'm thinking so!

Stay thoughtful. Stay bold. Stay diligent. Stay experimental. Stay curious...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Question everything?

We straddle a line in the botanical-style aquarium world. It involves tradeoffs, understanding, and accepting different ideas than we've previously done.

And, as I've discussed many times here, it's about making those mental shifts to accept both the benefits and beauty of some of the processes which Nature utilizes to manage its ecosystems. Like decomposition, additions of materials, and exchanges of water.

It's about questioning why some things in the hobby are "taboo", and others aren't.

Some of the processes and products of the processes, specifically, have been, IMHO, unfairly vilified by the hobby for many years.

Like our old friend, detritus.

I think detritus has been so maligned as a “bad” thing in the hobby, that we have collectively overlooked its benefits to the organisms and overall closed ecosystems we create.

We need to question our attitude about this stuff.

And of course, we have those age-old "rules" of the aquarium hobby; guidelines and "best practices" passed on by our hobby forefathers. Time-honored traditions of aquarium management.

Conduct regular water exchanges. Stock your aquarium carefully. Feed precisely. Observe. Be habitual about these things. They're hammered into our heads from day one.

Now, these are not necessarily bad things at all.

In fact, they're concepts which form the fundamentals of our hobby practices. Over the years, we've seen lots of hobbyists trying to develop workarounds to try to avoid stuff like water exchanges, etc., clearly trying to defy Nature- and we don't question these things all that much, right?

I think that rather than just trying to avoid the "rules" of aquarium keeping, we should question why they exist, what factors make them important, and how we can embrace some of the things Nature already does to accomplish them same things we work so hard to do- or avoid- by other means.

And further, we almost never see discussions about how Nature, if allowed to do some of its own "work", will help us manage and evolve systems with tremendous success.

It's fine line that we need to walk. A line that straddles pushing against some natural processes while embracing others.

Why doesn't it seem almost like an act of insurrection when we question stuff in the hobby that we've taken as "gospel" for generations?

Maybe it's because we haven't really thought much about this stuff, in terms of how it is actually beneficial, as opposed to detrimental. And how, despite it not being the most attractive thing in the world, that some of these things are beautiful, natural, and incredibly important to the function of our closed systems if we give them a chance.

It seems that we spend so much time resisting the appearance of some of this stuff based on how it looks, that it's not given a chance to display its "good side" for us. For those of us who play with botanical-style aquariums, resistance, as they say, is futile.

Let's face it:

As everyone knows, when you put terrestrial materials in water, one of four things seems to happen:

1) Nothing.

2) It starts to break down and decompose.

3) It gets covered in a gooey slime of algae, fungal growth, and "biofilm."

4) Both 2 and 3

Why is the appearance of this stuff "bad?" What has caused the mainstream of the hobby to freak out about these things for so long?

Yeah, seriously. We need to step back and question why.

Like biofilms, fungal growth, aufwuchs, and decomposition- is this stuff that is inevitable, natural- perhaps even beneficial in our aquariums? Is it something that we should learn to embrace and appreciate? All part of a natural process and yes- aesthetic- that we have to understand to appreciate? Have you ever tried rearing fry in a tank filled with decomposing leaves and biofilms?

Try it. Question it. Work with it. But try it. Don't just dismiss these things outright. Ask yourself why it works...search for answers. There is a lot there.

Let's think more on our "number one" mental shift subject: Biofilms.

Biofilms form when bacteria adhere to surfaces in some form of watery environment and begin to excrete a slimy, gluelike substance, consisting of sugars and other substances, that can stick to all kinds of materials, such as- well- in our case, botanicals.

It starts with a few bacteria, taking advantage of the abundant and comfy surface area that leaves, seed pods, and even driftwood offer. The "early adapters" put out the "welcome mat" for other bacteria by providing more diverse adhesion sites, such as a matrix of sugars that holds the biofilm together.

Since some bacteria species are incapable of attaching to a surface on their own, they often anchor themselves to the matrix, or directly to their friends who arrived at the party first.

Sorta sounds like Facebook, huh?

(The above graphic from a scholarly article illustrates just how these guys roll.)

And we could go on and on all day telling you that this is a completely natural occurrence; bacteria and other microorganisms taking advantage of a perfect substrate upon which to grow and reproduce, just like in the wild. Freshly added botanicals offer a "mother load"of organic material for these biofilms to propagate, and that's occasionally what happens - just like in Nature.

Yet it does, so we will! :)

The real positive takeaway here: Biofilms are really a sign that things are working right in your aquarium! A "visual indicator" that natural processes are at work.

Yet, understandably, it may not make some of you feel good.

However, it should.

Push yourself...read. Research. There is a shockingly large amount of scholarly information out there on these very topics...way more, and way more detailed than what we provide here in "The Tint." It's a bit harder to digest, I admit...but the information is there for the gleaning, if you want to.

And I believe that, once you ask these questions, and make those mental shifts to accepting stuff that formerly frightened or repulsed you- it opens you up to a world of possibilities in this hobby.

The botanical-style aquarium that we play with is perhaps the first of it's kind in the hobby to really say, "Hey, this is just like Nature! It's not that bad!" And to make us think, "Perhaps there is a benefit to all of this?"

I think we're starting to see a new emergence of a more "holistic" approach to aquarium keeping...a realization that we've done amazing things so far, keeping fishes and plants in a glass or acrylic box with applied technique and superior husbandry...but that there is always room to experiment and push the boundaries even further, by understanding and applying our knowledge of what happens in the natural environment.

You're making mental shifts...replicating Nature in our aquariums by achieving a greater understanding of Nature...

Keep making them.

You're laying down the groundwork for the next great phase of aquatic husbandry innovation and breakthrough.

Keep innovating.

And all starts with questioning...everything.

Stay curious. Stay innovative. Stay bold. Stay observant...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

"You know you're a hardcore aquarist when________________________"

Ever think about what separates you from the "typical" person who keeps aquariums? You know, those casual, "I-have-an-aquarium-but-I'd-just-as-soon-have-a-hamster" types?

Yeah, you know what I'm talking about.

Aquarium hobbyists, like everyone else in life, tend to follow certain behaviors, fall into certain stereotypes, and like certain things. To an outsider, it’s very tempting to heap us into that broad category of “fish geek”, and leave it at that. I suppose, to some extent, that’s a fair, although rather broad, classification. Yet, unlike the classic “fish geek”, I’d hazard a guess that we’re not just obsessed with the animals themselves. Nope, we are into an amazing amount of other, related stuff, right?

In my mind, there are lots of hobbyists. Then there are hardcore hobbyists. They are easy to pick out from the basic “fish geek”, IMHO.

Yeah, there are plenty of classic "fish geeks", who just love looking at pretty fishes and plants interact in their tank. If you’re one of those people, chances are you have this insanely aquascaped tank, with some beautiful specimen plants, crazy driftwood, and a collection of very nice fishes. Most likely, you purchase your fishes from a variety of sources, making sure that each specimen fits into the theme as part of a greater “whole”.

Then you get the more extreme hobbyists, a distinct variation of the classic fish geek, who’s tank is a bit more prominent in the household. These people are often the owners of larger aquariums, and they like to shop at the local fish store, or may even have a favorite online livestock vendor or two that they work with. They will not miss a sale if there is a chance to add to their collection, probably did a lot of the work on their tank build themselves, and are likely to have more than one aquarium.

Next comes the “hardcore hobbyist”, the classification many of us fall into. Here is the basis for today’s discussion.

Not only is the “Hardcore” dedicated to his/her hobby on a very serious level- he or she has made aquariums the number one obsession/hobby. Enter the custom made tanks, valves for almost everything, and freezers and refrigerators full of frozen foods and live cultures. These people have extreme brand loyalty to foods, lighting manufacturers, and even activated carbon brands.

“Hardcores” are all about the system, the animals, and the lifestyle that goes with it. They have morning rituals, evening tasks, and “aquarium weekends”, where the goal this week is to “re-route my Co2 system to a reactor” or some other equally arcane thing. They are frequent shoppers at Home Depot, and know their way around the plumbing department. This group is very likely to choose sides in the "Dutch Style"-versus-"Nature Aquarium Style" rivalry. Auctions, conferences, and fish club meetings are just part of the lifestyle for these folks. They’ve been the recipient of multiple BAP recognitions, and have probably bred and reared dozens of varieties of fishes.

They frequent multiple forums, are known by their “usernames” in the aquarium keeping community, check Aquatic Plant Central or Cichlids.com daily for the latest information, are extremely brand-loyal to one or more livestock vendor, yet are always looking for the edge to acquire that dream fish or plant. These are the best people to trade with, as they seem to have accumulated just about everything during their hobby “career”, and are more than happy to reach into their tank at a moment’s notice to snap you off a segment of that rare Sword, or net you a few fry of that cool Fundulopanchax gardneri "Nsukka" that you said you liked.

Generous often to a fault!

Hardcore hobbyists know and interact with the “celebrity” aquarium crowd with a remarkable ease. They love dropping names: “I asked George (Farmer) about that ‘scape he did last week at the AGA Convention” or “Well, Heiko (Bleher) said that this cichlid was collected from deep water off of the Rio Lago Batata…” They will often cite writings and YouTube videos almost from memory, like a scholar recites Shakespeare: “And Rachel O'Leary said that your tank needs to have more rocks if….” A hardcore will often use their favorite celebrity to back up their position in a disagreement: “Well, Oliver (Lucanus) states clearly that the L46 is way hardier than the L52 Pleco.”

“Hardcores” have an extensive aquarist vocabulary, and use terms like “morphology”, “allelopathy”, and “infusoria” with complete ease. Things like “Potassium”, “ Ferts” and “Grindal Worm Culture” are simply part of the territory. Using a CO2 system and pH probe (properly calibrated, of course) is a given. and a controller is pretty much like having a Home Theater or Satellite TV for these people (“So, what’s the big deal? Doesn’t everyone have that stuff?"). Automatic top-off systems, refugiums, fancy lighting arrays, and complex fish room electrical panels are just part of the game for these types.

Many have “fish rooms” built along with their system, and the basement or garage in their home is dominated by makeup water tanks, food culture stations, or even more tanks. These are the best hobbyists to visit! Fish food buckets, old equipment, and parts are never thrown away.

Rather, they are treasured, organized (well, sometimes!), loosely classified, and made available to other hardcore hobbyists who are in a pinch (You need an impeller from a 2004 Eheim pump? Which pump do you have- a 1206 or a modded 1224?”, or “I have a spare suction cup for an ADA Pollen Glass you can use…”). This crowd knows the merits of CO2 Proof tubing, Starphire glass, and lots of electrical outlets near their tank. And they have a shitload of aquariums!

Hardcores will take into account their need for storage, electrical modifications, and reinforced floors to support their tank when looking for a new place to live. Imagine a hardcore aquarist on one of those cable TV real estate shows. I can see it now: “The first place had a really nice walk-out basement, but not enough room for my Discus breeding system. The other place was close to three great fish stores…The third place has a fantastic walk-in closet behind the family room where I can locate the inline heater…" As a hardcore aquarium hobbyist, it’s a given that many real estate considerations are based on having room for present-and future- dream systems.

Even important life decisions are based around the reef lifestyle: “If we get pregnant this month, I’ll be coming to term right around the AKA Convention…Or MACNA, if the baby is late. No way!” or “We can’t take vacation that week, I’ll have three batches of Corys that will be weaning off live baby brine” or “Let’s postpone the root canal until after the tank is delivered…” Yeah- much of your life revolves around the aquarium game.

Scary to an outsider- par for the course for us!

Hardcore aquarium hobbyists speak a different language, with terms like “Pleco”, “Cory”, “Subwassertang”, “Amazonia”, and “Wabi Kusa” bandied about. And we know and use all of the crazy pedigree names without reflection, “That’s definitely an Fp. bivitattum RPC 234”, or, "Dude, that L86 Pleco is away nicer than your Farowella…” You get the idea, right? Go to a fish convention/auction and it will very much remind you of the famous “cantina scene” from “Star Wars”, with tons of different dialogues going on in seemingly an alien language. It’s "all Greek" to the hardcore aquarium hobbyist, though!

Have you noticed that many hardcore hobbyists are also “techies” to some extent? Not only can they fix up a mean home theater system, but they are really into equally tech-heavy hobbies like photography, SCUBA diving, custom A/V systems, and whole-house automation. All are loved, but not revered like aquarium keeping. And you’ll find little signs of the influence of the lifestyle all over the house. Look into their kitchen cabinets and you’re likely to see ACA shot glasses, “crazybettas.com” bottle openers, maybe a Tannin throw blanket- and stuff like that.

A good chunk of many a hardcore hobbyist's casual wardrobe is tee shirts acquired at vendor booths at conferences and auctions. Note to my fellow vendors: As vendors, we have an obligation to provide shirts to hardcore hobbyists at conferences…I mean, how else would they be able to dress themselves? Please factor shirts into your promo budget this year…

Look, I love just about anyone that’s into the hobby. However, you hardcore aquarists- and you know who you are- hold a very special place in my heart. You get it. You understand what it’s like to wake up at 2:30 in the morning for a glass of water, walk by your tank, and see that this one piece of driftwood is askew.

So you’ll casually start adjusting it- and still be into what has now morphed into a major remodeling project at 7 AM, when the rest of the household is just waking up- and you’ll no doubt be working on it throughout the day, calling in sick to work to get this done!

That’s part of being hardcore.

I’ve thrown out just a few examples here…No doubt you have dozens more based on your own experiences, or experiences with other hardcore aquarists…Let’s hear ‘em! Get them out in the open, so that we can accumulate the definitive reference on hardcore aquarium hobbyists. This will help those who wish to live with us, exist with us, or even join us in our geeky obsession!

“You know you’re hardcore aquarist when___________” is just scratching the surface!

As always, thanks for stopping by, sharing, and interacting!

Stay unique. Stay diligent. Stay dedicated. Stay involved. Stay...hardcore!

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Deep dives, black water, and rocks...

The beauty of the aquarium hobby is that we can find no shortage of inspiration from the natural world. You don't have to look all that hard to find it.

And, if we look really hard, we can find combinations of various, seemingly incongruent components that we might not have ever considered using together before. And we can apply them to our aquarium practice and be entirely consistent with Nature!

As we delve deeper into the world of botanical-style, blackwater aquariums, I think it becomes more and more important for us to understand the wild blackwater habitats of the world.

Specifically, how they form, and what their physical characteristics are. It's easy for us to just go the "cliche' route" and say that blackwater is water, "...which has a low pH caused by dissolved organic materials and looks the color of tea." You could just leave it at that. You know, the standard line used for decades.

Not untrue, but not really all that helpful in understanding exactly what it is, IMHO.

And more important, understanding why it has these characteristics.

And there are some things which contribute to the overall habitat of blackwater environments- specifically, how they form.

Well, it starts with the study of rocks...Yeah, Geology.

Hey, don't start yawning on me...

I should first start of by freely admitting that I sort of- well, dozed through the limited number of geology classes I took in high school and college, and never knew that the time I spent in those classes drawing pictures on the back of my notebooks would ever come back to haunt me decades later, when I'd have to re-familiarize myself with all of this stuff!

So, my understanding is admittedly quite limited, but I'll convey what I DO know to you here...And just how it relates to our area of interest.

Blackwaters in areas like Amazonia (one of our fave locales, of course!) drain from an area known to geologists as the "Precambrian Guiana Shield", which is comprised of sediments include quartz, sandstone, shales, and conglomerates, stemming from the formation of the earth some 4.6 billion years ago. As a result of lots of geological activity over the eons, a soil type, consisting of whitish sands called podzol is formed.

Podzols typically derive from quartz-rich sands, sandstone, and other sedimentary materials in areas of high precipitation. (Hmm, like The Amazon!). Typically, Podzols are kind of well, shitty for growing stuff, because they are sandy, have little moisture, and even less nutrients!

A process called podzolization (of course, right? WTF else would you call it?) occurs where decomposition of organic matter is inhibited. Numerous microbes and plants consume some of the nitrogen, and while eaten by other organisms, convey what's left to the even lower-lying forest habitats.

The Amazonian blackwater rivers are largely depleted in nutrients, having passed through the lowland forest soils as groundwater, from which weathering has already occurred. As a result, layers of acidic organics build up. With these rather acidic conditions, a deficiency of nutrients further slows down the decomposition of organics. So, yeah- lousy soil for growing stuff...But guess, what? They form the basis of the substrate in many Amazonian aquatic habitats!