- Continue Shopping

- Your Cart is Empty

Normal in our world...

Funny how your perspectives on the hobby change over time.

You know what's weird to me? When I realize that I'm so far down the rabbit hole of natural, botanical-style aquariums that a so-called "typical" aquarium, with clear water, spotless sand, perfectly-ratioed wood, and crisp green plants seems sort of "odd" to me.

Yeah, that's when I know I've kind of definitely changed as an aquarist!

I'll be the first to admit- the aesthetics of a botanical-style aquarium are just fundamentally different than what we've come to expect from other types of aquariums we play with in the hobby. We've talked about this at least 300 times here over they years, right? And this "difference" often comes up when it's time to share our work with others!

Periodically, we do photography on the tanks here in the office, and I'm fortunate enough to have the incredibly talented Johnny Ciotti practice his craft. Typically, a day or two before he comes to do the pics, Johnny will call me and tell me stuff like, "Remember to clean the waterline..."

And of course, that's where I start getting stressed, lol.

Have you ever noticed that our botanical style aquariums, with all of their leaves and seed pods and such, when they break down, seem to leave behind a sort of "protein film" on the water's surface.Or at least against the glass.

I almost always see this stuff in my tanks...do you? And I suck at removing the stuff...And when I apologize for Johnny having to do one more "wipe down" of the waterline before he photographs my tanks, he'll often joke that, "No one in the aquascaping world ever accused your tanks of being too clean-looking..."

And I have to laugh when he says that, because it's once again, a matter of perception, right?

Now, it's typical of the "visuals" and aestheics that I have come to expect from botanical style aquariums. And of course, it's just one of them..there are quite a few, really.

If you're sort of at a loss for words trying to explain the "aesthetic differences" of our tanks and those most hobbyists have become more familiar with, I figured it might be good to touch on them now and again to give you a little "air cover" when you're showing your tank to others.

Here are a few:

Biofilms and fungal growths will accumulate on "undefended" surfaces (ie; leaves, seed pods, bark, etc.). We know this from years and years of working with this stuff, right? Particularly when terrestrial materials are submerged in water, they tend to be very attractive "attachment points" for bacterial growth and the "construction" of biofilms. The appearance and proliferation of biofilms are almost a "right of passage" to botanical-style aquarium enthusiasts.

They look awful to those who are not accustomed to seeing them in aquariums. I get it- they are sort of "contrary" to everything we take as "normal" in aquarium keeping. They look like shit to many hobbyists, but they are absolutely natural and normal.

When you make that mental shift which understands that biofilms are a key part of the habitat, and perform a vital role in the sequestering and processing of nutrients in Nature, providing supplementary food for other organisms, and contributing to the formation of food webs, they become desirable, elegant...perhaps- maybe...beautiful?

Decomposition of botanicals is another absolute "given" for botanical-style aquariums, right? Pretty much the minute that you add botanical materials to water, they start to physically disintegrate; the speed and extent to which each breaks down influenced by numerous factors, such as the specific "structure" of the botanical itself, the water chemistry, temperature, and other physical influences, such as water movement, the presence of xylophores, or fishes which disturb or "graze" on the botanicals.

There is a difference between "color" and "clarity." The color of the water in botanical-style aquariums is, as you know, a product of tannins leaching into the water from wood, substrate materials, and botanicals, and typically is not "cloudy." It's actually one of the most natural-looking water conditions around, as water influenced by soils, woods, leaves, etc. is ubiquitous around the world. Other than having that undeniable color, there is little that differentiates this water from so-called "crystal clear" water to the naked eye.

Of course, the water may have a lower pH and general hardness, but these factors have no bearing on the visual clarity of the water.

I'm gonna "riff" on this a bit, because it's both "foundational" to our work, and often misunderstood...

And of course, I won't disagree that "clear" water is nice. I like it, too...However, I would make the case that "crystal clear" water is: a) not always solely indicative of "healthy" or "optimum" , and b) not always what fishes encounter in Nature.

The point is, we as fish geeks seem to associate color in water with overall "cleanliness", or clarity. The reality is, in many cases, that the color and clarity of the water can be indicative of some sort of "issue" in many aquariums, but color seems to draw an immediate "There is something wrong!" from the uninitiated!

And it's kind of funny- if you talk to ecologists familiar with blackwater habitats, they are often considered some of the most "impoverished" waters around, at least from a mineral and nutrient standpoint.

In the context of the aquarium, of course, the general hobby at large doesn't think about "impoverished." Many just see colored water and think..."dirty."

And of course, this is where we need to separate two factors:

Cloudiness and "color" are generally separate issues for most hobbyists, but they both seem to cause concern. Cloudiness, in particular, may be a "tip off" to some other issues in the aquarium. And, as we all know, cloudiness can usually be caused by a few factors:

1) Improperly cleaned substrate or decorative materials, such as driftwood, etc. (creating a "haze" of micro-sized dust particles, which float in the water column).

2) Bacterial blooms (typically caused by a heavy bioload in a system not capable of handling it. Ie; a new tank with a filter that is not fully established and a full compliment of livestock).

3) Algae blooms which can both cloud AND color the water (usually caused by excessive nutrients and too much light for a given system).

4) Poor husbandry, which results in heavy decomposition, and more bacterial blooms and biological waste affecting water clarity. This is, of course, a rather urgent matter to be attended to, as there are possible serious consequences to the life in your system.

Remember, just because the water in a botanical-influenced aquarium system is brownish, it doesn't mean that it's of low quality, or "dirty", as we're inclined to say. It simply means that tannins, humic acids, and other substances are leaching into the water, creating a characteristic color that some of us geeks find rather attractive. If you're still concerned, monitor the water quality...perform a nitrate test; look at the health of your animals.

What's happening in there?

People ask me a lot if botanicals can create "cloudy water" in their aquariums, and I have to give the responsible answer- yes. Of course they can! If you place a large quantity of just about anything that can decompose in water, the potential for cloudy water caused by fine particulate matter from the materials, and a bloom of bacteria resulting from their presence exists.

In my home aquariums, and in many of the really great natural-looking blackwater aquariums I see the water is dark, almost turbid or "soupy" as one of my fellow blackwater/botanical-style aquarium geeks refers to it. You might see the faintest hint of "stuff" in the water...perhaps a bit of fines from leaves breaking down, some dislodged biofilms, pieces of leaves, etc. Just like in nature. Chemically, it has undetectable nitrate and phosphate..."clean" by aquarium standards.

Sure, by municipal drinking water standards, color and clarity are important, and can indicate a number of potential issues...But we're not talking about drinking water here, are we?

"Turbidity." Sounds like something we want to avoid, right? Sounds "dangerous" somehow...

On the other hand, "turbidity", as it's typically defined, leaves open the possibility that it's not a negative thing:

"...the cloudiness or haziness of a fluid caused by large numbers of individual particles that are generally invisible to the naked eye, similar to smoke in air..."

What the HELL am I getting at?

Well, think about a body of water like an igapo adjacent to the Rio Negro, as pictured above in the photo by Mike Tuccinardi. This water is of course, "tinted" because of the dissolved tannins and humic substances that are present due to decaying botanical materials. And it's also a bit "turbid" because of the fine particulate matter from these materials, too.

I would argue that these conditions are not "unhealthy" to fishes, right?

Okay, we've beaten the living shit out of that, haven't we?

Yeah.

The substrates that we utilize influence both the aquarium's appearance and its chemistry. This is, of course, essentially what happens in Nature. In the flooded forests of South America and elsewhere terrestrial materials, such as botanicals, roots, branches, leaves, and soil play a role in shaping the aquatic ecosystem which arises following the seasonal inundation.

The mix of materials which comprise these unique habitats has definitely been an inspiration for me to create quite a few different aquariums over the years! There is so much we can learn from studying these systems that we can apply in our hobby work!

To show you how geeky I am about this stuff, I have spent hours pouring over pics and video screen shots of some of these igapo habitats over the years, and literally counted the number of leaves versus other botanical items in the shots, to get a sort of leaf to botanical "ratio" that is common in these systems. Although different areas would obviously vary, based on the pics I've "analyzed", it works out to about 70% leaves to 30% "other botanical items."

The trees-or their parts- literally bring new life to the waters. Some are present when the waters begin rising. Others continue to arrive after the area is flooded, falling off of forests trees or tumbling down from the "banks" of the stream by wind or rain. Terrestrial trees also play a role in removing, utilizing, and returning nutrients to the aquatic habitat. They remove some nutrient from the submerged soils, and return some in the form of leaf drop. Terrestrial materials like this become part of the "active substrate" in our aquariums.

And of course, there's the soils...

Now, I think one of the most "liberating" things we've seen in the blackwater, botanical-style aquarium niche is our practice of utilizing the substrate itself to become a feature aesthetic point in our aquariums, as well as a functional mechanism for the inhabitants.

In other words, in a strictly aesthetic sense, the bottom itself becomes a big part of the aesthetic focus of the aquarium, with the botanicals placed upon the substrate- or, in some cases, becoming the substrate! These materials form an attractive, texturally varied "micro-scape" of their own, creating color, interest, and functions that we are just starting to appreciate.

In fact, I dare say that one of the next "frontiers" in our niche would be an aquarium which is just substrate materials, without any "vertical relief" provide by wood or rocks.

I've executed a few aquariums based on this idea (specifically, with leaves), and I've been extremely happy with their long-term performance! Oh, and they kind of looked cool, too...

Nature provides no shortage of habitats with unusual substrate composition for inspiration. If we look at them in context of the surrounding terrestrial ecosystem, there are a lot of possible "functional takeaways" that we as hobbyists can apply to our aquarium work.

And the interesting thing about these features, from an aesthetic standpoint, is that they create an incredibly alluring look with a minimum of "design" required on the hobbyists part. Remember, you can to put together a substrate with a perfect aesthetic mix of colors and textures, but that's about it.

We have to "cede" some of the "work" to nature at that point!

And we've talked about the idea not only of creating more "functionally aesthetic" substrates, but the idea of incorporating botanicals into them, as well. One of our favorite "edits" is to include a significant amount of leaf litter into the substrate, as you'd find in the sedimented, leaf-litter-rich, and silt-laden substrates of wild tropical environments.

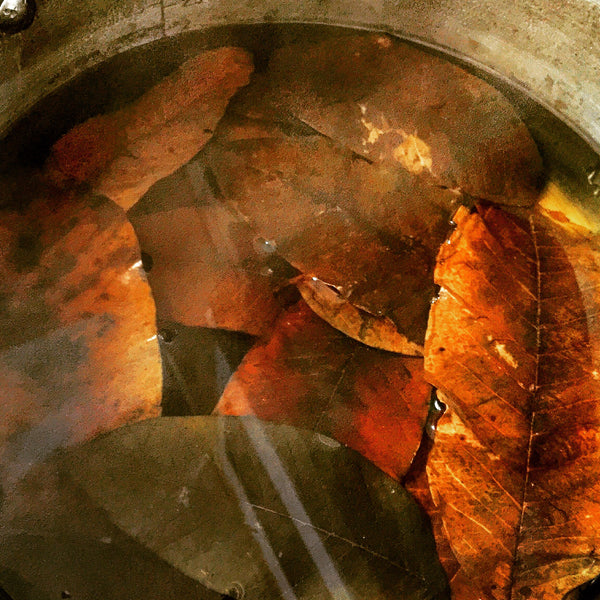

How would you replicate the form and function in the aquarium? We accomplish this with either the small, yet durable Texas Live Oak leaf litter, or with our "Mixed Leaf Media" product, which is essentially a graded mix of crushed Catappa, Guava, Jackfruit, and Bamboo leaves. When steeped or boiled, the stuff goes right to the bottom, and is easily mixed into the substrate material that you're using in your system.

The result, when well mixed in, is a composition which looks and functions much like a real tropical stream or flooded forest floor substrate. The idea that not only will you create an interesting appearing substrate, you'll end upon with one which can impart tannins and humid substances, while serving as a biological support for the production of biofilms and fungal growth.

Functionally aesthetic.

It's definitely contrarian, at least. Is it rebellious, even?

Maybe.

Our original mission at Tannin was to share our passion for the reality of "unedited" Nature, in all of its murky, brown, algae-patina-enhanced glory. And I started to realize that a while back, we were starting to fall dangerously into that noisy, (IMHO) absurd, mainstream aquascaping world. Pressing our dirty faces against the pristine glass, we were sort of outsiders looking in...the awkward, different new kid on the block, wanting to play with the others.

Then, the realization hit that we never really wanted to play like that. It's not who we are.

We are not going to play there.

We're going to "double down" in our dirty, tinted, turbid, decomposing, inspired-by Nature world. Sure, our materials can and should be utilized by all sorts of hobbyists for all sorts of applications. However, if you were worried about your favorite little quirky supplier of twigs and nuts becoming yet another "player" in the world of homogenized, prepackaged, generic blah, let me assure you now that it will not be happening.

We're all-in on the "preservation of the patina." Biofilms. Detritus. Decomposing leaves... Letting Nature do her thing and not "sanitizing it."

All that stuff.

So, it's of utmost import that we periodically publish some "position pieces" about expectations, processes, practices, and ideas. And it's also vital for us to share our ideas, experiences, and inspirations.

Thanks for being a part of this exciting, ever-evolving, tinted world!

Stay level-headed. Stay creative. Stay engaged. Stay excited. Stay studious. Stay rebellious!

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

From idea to microcosm

That pretty much comes up the idea of a botanical-style aquarium, doesn't it? I think that it does. I've been obsessed with the idea of an aquarium as a microcosm for almost as long as I can remember. Fresh, salt, whatever- it's guided almost every tank of built for decades.

Even my earliest iterations of leaf-litter dominated aquariums adhered to the "aquarium as a microcosm" philosophy.

Now, when you ask me about the pic which really steeled my obsession with the idea of deep leaf litter beds and flooded forests, it would have to be this one from Mike Tuccinardi from the Amazon region.

This one image is literally why I took a "sabbatical" from the reef keeping world, sold my interest in my coral business, and went on to launch Tannin Aquatics. A classic igapo habitat- a flooded forest, replete with leaves, branches, seed pods, and terrestrial plants growing underwater. And the tinted, slightly turbid water...Perhaps the absolute perfect essence of what we're all about here.

I find endless inspiration in this one shot!

It pretty much sealed my fate as a lover of the igapo habitat and to learn all I could about replicating it in form and function in the aquarium.

And, every time I look at this pic (which I do a lot, let me tell you!), I'm reminded that there is a point in every botanical-style aquarium when you can sort of tell which way it's going. A point when you can see it transforming from an idea to a microcosm.

A "jumping-off" stage, where our initial work is done, and Nature takes over for a while, breaking down the botanicals, allowing a "patina" of biocover and biofilm to cover some of the surfaces, removing the crisp, harsh, "new" feeling. This is where Amano's concept of embracing the Japanese philosophy of wabi-sabi takes over. Accepting the transient nature of things and enjoying the beauty of the changes that occur over time.

And of course, once stuff starts "softening" or breaking down, it doesn't mean that your job is done, or that you're just an observer from that point on. Nope. It means that you're now in a cool phase of "actively managing" (and by "managing", I am emphasizing observation more than "intervening!") the aquarium.

Sure, when you embrace this mindset, you're making minor "tweaks" as necessary to keep the aquarium healthy and moving in the direction-aesthetically, functionally, and otherwise- that you want it to. Yet, at some point early in the process- you find yourself just letting go and allowing the tank to do what Nature intends it to do on it's evolutionary path...

A lot of people may disagree, but I personally feel that THIS phase is the most exciting and rewarding part of the whole process! And perhaps- one of the most natural...if we allow it to be.

A phase when you interact with your aquarium on a very different level; a place where you get to play a role in the direction your 'scape is going, without constantly interrupting the natural progression taking place within the little microcosm you created!

And of course, the natural "analog" of this phase is when those initial rains arrive and inundate formerly dry habitats, flooding forests and grasslands, transforming them into aquatic habitats once again. Life begins to make a transition- an adaptation to a different environment. Microorganisms flourish and multiply, aquatic insects emerge. Fishes return to forage and reproduce.

When the rains subside somewhat after the initial inundation, the sort of "pause" between storms gives life a chance to make those adjustments necessary during the transformation.

It's a wonderful time in the life cycle of these habitats.

And it happens in an almost identical manner in the aquarium.

As botanical materials break down, more and more compounds (tannins, humic substances, lignin, bound-up organic matter) begin leaching into the water column in your aquarium, influencing the water chemistry and overall environment. Some botanicals, like leaves, break down within weeks, needing replacement if you wish to maintain the "consistency" of the habitat you've started to achieve in your aquarium.

Others, like bark, branches, and more robust seed pods last a much longer time. They not only serve to enrich the aquatic environment- they become "attachment points" for fungal growth, biofilms, and algal mats- just like in Nature.

Many hobbyists tend to want to rush through this phase, where all of the biofilms and decomposition begins and accelerates- as if it is some sort of "obstacle" we need to overcome to get to some ultimate destination with our aquarium. Understanding that it's NOT- and that, in fact, it's the whole game- changes your perspective entirely.

Yet, a lot of people want to see the aquarium move on from this point rather quickly.

I feel sad for them. They need to enjoy it. Savor it. Why do we as aquarists not embrace this part of our aquariums' evolutions a little more wholeheartedly? Why do we dedicate some much energy to resisting Nature's work than we do enjoying it?

I was wondering if it has to do with some inherent impatience that we have as aquarists- or perhaps as humans in general-a desire to see the "finished product" as soon as possible; something like that. And there is nothing at all wrong with that, I suppose. I just kind of wonder what the big rush is?

I guess, when we view an aquarium in the same context as a home improvement project, meal preparation, or algebra test, I can see how reaching some semblance of "finished" would take on a greater significance! Those earlier, in-between-sort of moments are not nearly as exciting as some perceived destination or outcome we have in mind for our tank.

We have an idea in our head of HOW it's" supposed" to look, and to many, anything that falls short of that is just a "phase", I suppose.

On the other hand, if you look at an aquarium as you would a garden- an organic, living, evolving, growing entity- then the need to see the thing "finished" becomes much less important. Suddenly, much like a "road trip", the destination becomes less important than the journey. It's about the experiences gleaned along the way. Enjoyment of the developments, the process.

In the botanical-style aquarium, it's truly about a dynamic and ever-changing system. An evolution. A process. Started by us, assisted by Nature.

Every stage holds fascination.

Just like it does in the wild habitats that we covet so deeply.

To not allow an aquarium to evolve- to not trust Nature to help take it from an idea to a microcosm- is to not allow oneself the opportunity to witness firsthand the wonders of the natural world, and the incredible promise, tenacity, and beauty of life underwater.

Be kind to yourself and your aquarium. Be patient and enjoy the journey.

All of it.

Stay calm. Stay engrossed. Stay observant. Stay persistent. Stay brave...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

The how's and why's of botanical prep- revisited...again!

Let's face it- one of the fundamental "skills" we have to learn as lovers of botanical-style aquariums is the preparation of the materials that we use. It's pretty much a given that we employ some prep before adding botanicals to our aquariums.

And it's an important practice which sets the stage for a successful natural aquarium experience. And we're all about seeing you succeed, so let's review this stuff again!

The idea is to get your dried botanical materials into a condition where they are both reasonably clean, and with their tissues saturated sufficiently to cause them to sink. This usually involves some simple, yet possibly time-consuming tasks, as we've all come to know.

There are basically three ways to prepare most botanical materials for use in the aquarium:

1) Boil them/steep them in boiling water

2) An overnight (or longer) soak in room temperature water

3) A combination of both.

Always rinse any of our botanicals in clean fresh water before use, even after boiling or soaking. This will rinse away any loose dirt or organic material that has adhered to their surface tissues. Just sort of a "best practice", IMHO.

We start with boiling.

For the vast majority of botanicals, you'll need to boil them in a clean pot for at least 30-40 minutes; many "stubborn" ones (ie; really buoyant botanicals) may take more than an hour of continuous boiling! I'm thinking of Sterculia pods, Afzelia pods, and Carinaina pods here...

The boiling process not only saturates the tissues of many botanicals, it breaks them down a bit, and helps release any surface dirt that might be remaining (like dust, pollen, spider webs, etc.). The boiling serves the dual purpose of helping release pollutants and getting them to absorb water to sink. (No one likes a floating pod)

Consider that boiling water is used as a method of making water potable by killing microbes that may be present. Most nasty microbes "check out" at temperatures greater than 60 °C (140 °F). For a high percentage of microbes, if water is maintained at 70 °C (158 °F) for ten minutes, many organisms are killed, but some are more resistant to heat and require one minute at the boiling point of water. (FYI the boiling point of water is 100 °C, or 212 °F)...However, for the most part, most of the nasty bacteria that we don't want in either our tanks or our stomachs are eliminated by this simple process.

A minimum of ten minutes of boiling is "golden", IMHO. The boiling process not only saturates the tissues of many botanicals, it breaks them down a bit, and helps release any surface dirt that might be remaining (like dust, pollen, spider webs, etc.). The boiling serves the dual purpose of helping release pollutants and getting them to absorb water to sink. (No one likes a floating seed pod...well, maybe some of us do, but...)

And of course, we boil botanicals to kill any possible microorganisms which might be present on them. Leaves, seed pods, etc. have been exposed to rain and dust and all sorts of things in the natural environment which, in the confines of an aquarium, could introduce unwanted organisms and contribute to the degradation of the water quality.

Makes sense, right?

Boiling also serves to soften and saturate the tissues of the botanicals.

Most seed pods have tougher exterior features, and require prolonged boiling and soaking periods to release any surface dirt and contaminants, and to saturate their tissues to get them to sink when submerged!

There is no "absolute" in this, either.

Each botanical item "behaves" just a bit differently, and many will require slight variations on the theme of "boil and soak", some testing your patience as they may require multiple "boils" or prolonged soaking in order to get them to saturate and sink.

Yeah, some of those damn things can be a pain!

However, I think the effort is worthwhile.

Now, sure, I hear tons of arguments which essentially state that "...these are natural materials, and that in Nature, stuff doesn't get boiled and soaked before it falls into a stream or river." Well, damn, how can I argue with that? The only counterargument I have is that these are open systems, with far more water volume and throughput than our tanks, right? Nature might have more efficient, evolved systems to handle some forms of nutrient excesses and even pollution. It's a delicate balance, of course.

If you remember your high school Botany, leaves, for example, are surprisingly complex structures, with multiple layers designed to reject pollutants, facilitate gas exchange, drive photosynthesis, and store sugars for the benefit of the plant on which they're found.

As such, it's important to get them to release some of the materials which might be bund up in the epidermis (outer layers) of the leaf. As we get deeper into the structure of a leaf, we find the mesophyll, a layer of tissue in which much of photosynthesis takes place.

We use only dried leaves in our botanical style aquariums, because these leaves from deciduous trees, which naturally fall off the trees in seasons of inclement weather, have lost most of their chlorophyll and sugars contained within the leaf structures. This is important, because having these compounds present, as in living leaves, contributes excessively to the bioload of the aquarium when submerged...

Rest assured, we are researching the use of more "fresh" tropical leaves in our systems; I'll get back to you on that one soon!

Are there variations on this preparation regimen?

Well, sure.

Many hobbyists rinse, then steep their leaves rather than a prolonged boil, for the simple fact that exposure to the newly-boiled water will accomplish the potential "kill" of unwanted organisms, which at the same time softening the leaves by permeating the outer tissues. This way, not only will the "softened" leaves "go to work" right away, releasing the beneficial tannins and humic substances bound up in their tissues, they will sink, too!

And materials like oak twigs often need a prolonged boil and soak to get them to sink reliably. It's a sort of "adapt as you go" thing, really.

And of course, I know many who simply "rinse and drop", and that works for them, too!

So why do we soak after boiling?

Well, it's really a personal preference thing. I suppose one could say that I'm excessively conservative, really.

I feel that it releases any remaining pollutants and undesirable organics that might have been bound up in the leaf tissues and released by boiling, which is certainly arguable, but is also, IMHO, a valid point. And since we're a company dedicated to giving our customers the best possible outcomes- we recommend being conservative and employing the post-boil soak before adding your botanicals and leaves to your aquarium.

So, how long do you soak your botanicals?

The soak could be for an hour or two, or overnight...no real "science" to it. Some aquarists would argue that you're wasting all of those valuable tannins and humic substances when you soak the leaves overnight after boiling. My response has always been that you might lose some, but since the leaves have a "lifespan" of weeks, even months, and since you'll see tangible results from them (i.e.; tinting of the water) for much of this "operational lifespan, an overnight soak is no big deal in the grand scheme of things.

Do what's most comfortable for you- and okay for your fishes.

Like so many things in our evolving "practice" of perfecting the blackwater, botanical-style aquarium, developing, testing, and following some basic "protocols" is never a bad thing. And understanding some of the "hows and whys" of the process- and the reasons for embracing it-will hopefully instill into our community the necessity- and pleasures- of going slow, taking the time, observing, tweaking, and evolving our "craft"- for the benefit of the entire aquarium community.

Stay diligent. Stay observant. Stay studious. Stay curious...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Beyond the tint: Clearing the waters about botanical-style aquariums...

With the explosion of interest in botanical-style aquariums, there has been a tremendous influx of aquarists who have never worked with stuff like leaves, seed pods, and twigs in their tanks before. It makes a lot of sense; we've been told for a generation that these things can create environmental conditions in our aquariums which might challenge our abilities to manage them safely.

Now, I've spent the better part of the last two decades doing all sorts of crazy experiments with botanicals, and all of the past 5 or so years evolving Tannin Aquatics and advancing the "state of the art" of the botanical-style aquarium approach in general. It's been a very gratifying several years.

Yeah, I love the natural, botanical-style blackwater/brackish aquarium. I'm totally obsessed with utilizing botanicals in all sorts of cool aquariums! They look amazing, create a functional ecosystem for all sorts of fishes- and are utterly incapable of doing everything that we seem to want them to do!

Yep. That's correct.

With all of the cool tanks we're seeing coming up, and a growing global interest in blackwater, botanical-style aquariums, we're seeing a lot of discussion about the "functional" aspects of botanicals. Perhaps most astonishingly, we see self-proclaimed, yet likely well-intentioned "experts" (many of whom simply have not worked with these types of systems before personally) ascribing all sorts of characteristics to them, and alternatively proferring unsubstantiated claims about the benefits they can provide, as well as unfounded warnings about their "dangers."

It can be a head-scratching experience perusing forums sometimes! The spread of misinformation (unintentional or otherwise) is something we have- and will continue to- work very hard to clear up. It's not simply because we sell botanicals. It's because we are on the cusp of an aquarium movement and are helping foster the development of technique for these aquariums, hoping to dispel many years of misunderstanding and mystery- for the benefit of the entire aquarium hobby.

I consider it as much of an honor as it is our responsibility.

And with all of the discussion and "armchair experts" comes more than just a little confusion, a lot of opinion, and some occasional misconceptions about what botanicals can and cannot do for our aquariums.

Yeah. Confusing.

In this little blog piece, I'd like to focus on what botanicals cannot do!

Yeah, you heard me correctly.

Maybe I should clarify: Let's talk about what they can't do as completely as many hobbyists tend to assume that they can! We're just gonna look at four things- but these are topics which seem to come up again and again and again, so I feel there definitely worthy of a closer look!

IMOH, it's very important to clear up lingering (or emerging) misconceptions about the use of botanical materials in aquariums. Since our self-proclaimed "competitors" seem more intent on selling stuff than sharing information about it, we'll take the reins on this one yet again.

As in so many areas of the hobby, the more people become involved in the process of utilizing botanical materials in their aquariums, the more we break through and clear up some of the confusions about them...Now, it's not like anyone was intentionally trying to mislead people over the years- I think it was more of a matter of us just making lots of assumptions and drawing conclusions from widely varying sources- often with questionable validity, experience, or accuracy, or "regurgitating" second or third hand information from tangential topics.

Not a great way to help foster a hobby movement, right?

So, let's get down to it!

In no particular order, here are some concepts that I think we need to address:

1) Botanicals cannot soften your water! If I had a dollar for every question I've fielded on this topic.... Perhaps this is the most misunderstood thing of all about botanicals? Maybe. I think it's easy to see how this one got started and tends to hang around a bit in forums and such: Most botanical materials contain tannins and humic substances, which can drive down the pH in water with little to no carbonate hardness.

And of course, the tinted, soft acidic water in many natural habitats often has an abundance of leaves and botanicals present. I think that this gave a lot of hobbyists the impression that you could simply add some of these materials (leaves, etc.) into your tap water and create "Rio Negro-like" conditions easily!

Now sure, humic substances, tannins, and other compounds which color the water will be imparted to it when you add botanicals...

Yet, that's really only half of the story.

Botanicals cannot reduce the hardness of the water. This can only be accomplished with reverse osmosis or ion exchange ( a process in which calcium and magnesium ions are "exchanged" for sodium or potassium ions.)

Reverse osmosis is a water treatment process which relies on a membrane which has pores large enough to admit water molecules, yet "hardness ions" such as Ca2+ and Mg2+ remain behind and are flushed away by excess water. The resulting product water is thus called "soft water"-free of hardness ions without any other ions being added.

There is no botanical, leaf, or substance you can add- natural or otherwise- directly to your water to soften it.

And just because you toss in a bunch of catappa leaves, Alder cones, or whatever into your aquarium filled with un-altered tap water, it doesn't mean that the pH will plummet to Amazonian levels. The impact of these materials on pH is limited in water with significant carbonate hardness.

And this dovetails nicely with our next topic:

2) Tinted water is not necessarily acidic. Once again, another assumption that no doubt arose from the aesthetics of blackwater itself. And it is easy to see how it got started...Much like the misconception that botanicals soften the water, it was often assumed by hobbyists that the brownish tint imparted to the water by leaves and botanicals somehow implied that it is "soft and acidic." I mean, "If it looks like the Rio Negro, it must be just like the Rio Negro! Right? Um, nope.

Yes, once again, there is more than meets the eye.

Botanical materials contain substances that can reduce the pH in water with low to negligible carbonate hardness. However, the tannins, which are the substances which tint the water, cannot "overcome" the Calcium and Magnesium ions, and drive down the pH significantly in water with high levels of these carbonate hardness present. It simply is putting more materials into the water (which are often detectible by TDS meters in aquariums).

Color is simply not a reliable indicator of the pH and other characteristics of the water. And, as we've discussed before, there are natural aquatic habitats, such as the Tapajos, which have essentially clear water, yet are rather soft and acidic.

FINAL THOUGHT ON THIS TOPIC: If you want to create soft, acidic blackwater conditions with botanicals, you need to invest in a reverse osmosis/deionization unit, or use RO/DI water in your aquarium.

Okay, moving on to our final common misconception...

3) Catappa leaves can "cure" fish diseases. Well, this is one of the favorites which has been perpetuated for years (often by people who sell leaves online and elsewhere -hey, I'm in that group, huh?)- and it actually has some degree of validity to it. However, it's not a damn "cure all"- please get that out of your head once and for all.

It has been known for many years by science that botanicals like catappa leaves (and others) have substances in their tissues which do have some potential medicinal functions, like saponins phytosterols, punicalagins, etc. Fancy names that sound really cool- and these are often bounced around on hobby sites as the "magic elixir" for a variety of fish ailments and maladies.

Now, I can't entirely beat the shit out of this idea, as these compounds are known to provide certain health benefits- in humans. and for a long time, it was anecdotically assumed that they did the same for fishes. And believe it or not, there have been scientific studies that show benefits to fishes imparted by substances in catappa and other leaves.

I stumbled across a University study conducted in Thailand with Tilapia which concluded that Catappa extract was useful at eradicating the nasty exoparasite, Trichodina, and the growth of a couple of strains of Aeromonas hydrophila was also inhibited by dosing Catappa leaf extract at a concentration of 0.5 mg/ml and up. In addition, this solution was shown to reduce the fungal infection in Tilapia eggs!

And it is now widely accepted by science that humic substances (such as those present in Catappa leaves and other botanicals) are thought to have a wide range of health benefits for fishes in all types of habitats. We've covered this before in a great guest blog by Vince Dollar, and the implications for the hobby and industry are profound. Although they are not the "cure all" that many vendors have touted them as, leaves and other botanicals do possess a wide range of substances which can have significantly beneficial impact on fish health.

It's long been known that fishes from many blackwater environments seem to have relatively little resistance to many diseases present in aquariums when first imported. Anecdotally, a lot of fish importers and breeders report better acclimation periods and fewer losses of "blackwater-origin" fishes when held in aquariums which utilize catappa leaves and other botanical materials.

Coincidence? I don't think so. "Cure-all?" Definitely not.

Now, I would definitely say that utilizing botanicals and leaves in your aquarium can offer some potential health benefits to your fishes. However, once again, I'd stop well short of presenting them as some sort of "magic elixir" that can cure fish diseases with the reliability of a round of antibiotics, or whatever.

Rather, I think that there are some possible prophylactic health benefits for your fishes by utilizing these materials in the aquarium. I would not, however, utilize leaves and botanicals in aquariums as the sole means of curing or preventing fish diseases. However, in my opinion, when fishes are kept in a botanical-style aquarium in which other basic components of aquarium husbandry (ie; regular water exchanges, careful stocking, and good overall maintenance) are employed, they could provide a more healthy overall environment for many species of fishes.

4) Botanical-style aquariums are difficult to manage. As botanical materials decompose in the aquarium, they degrade the water quality. This is another popularly-embraced idea which I can't entirely brush off, because there is some validity to it, and it would be itotally rresponsible of me to dismiss it outright. This sort of goes hand-in-hand with our first "myth", but it deserves a bit of its own discussion.

Let's face it- when you have materials of any type breaking down in the aquarium, they are part of the bioload- and that requires an appropriately-sized population of beneficial bacteria and fungi to break down these materials without adversely affecting water quality.

This is not some abstract concept, unique to our area of interest. It's a "universal constant" in aquarium keeping.

We've written about this idea many, many times here in "The Tint", and talked about the "ecosystem" aspect of working with this type of aquarium quite a bit. In addition to husbandry, part of the game is accepting- indeed, encouraging- the idea of having these "natural partners" in maintaining a healthy aquarium.

Now, that being said, it would be utterly irresponsible of us to say that you can simply add tons of stuff to an aquarium- specifically one that has been in a stable existence for some time- and not be concerned about any impact on water quality. That's part of the reason why we repeatedly plead with you to go slowly when adding these materials to an established tank, and to test and gauge the impact on your water quality.

Going slowly not only allows you time to react- it gives your bacterial and fungal population the opportunity to grow and adjust to the increased bioload. These organisms can go a long way towards creating a stable, healthy botanical aquarium environment...But they can't work miracles- and they can't do it alone. And of course, common sense husbandry procedures, like regular water exchanges, use of chemical filtration media (activated carbon, PolyFilter, etc.) give you an added layer of "insurance." A healthy dose of common sense and judgement goes a long way towards a successful outcome!

Now, I'll be the first to state it. In fact, I will guarantee (something I rarely do) that you will kill every fish in your tank if you throw large quantities of botanicals into an existing aquarium without due regard for what they can do, how they function, and what is required of you to manage such a system. Basic understanding of the habitat your trying to replicate, the nitrogen cycle, pH, and aquarium management practice are all essential.

Don't f---k with Nature. She'll kick your ass.

Simple as that. Not pretty. But I think we can all understand that. If you're not up to the pleasurable effort of reading up on this stuff before you attempt a botanical-style aquarium, you have no one to blame but yourself when you fail.

So, pushing back against some of those long-held misconceptions about the botanical-style aquarium will hopefully encourage the uninitiated to give this whole "twigs and nuts" thing some due consideration. We as lovers of this type of system need to do our best to share the realities that we understand from personal experience, and to encourage others to give them a shot.

I can't help but reiterate once again that blackwater, botanical-style aquariums are no more difficult to set up and maintain than any other type of aquarium.

They do require understanding of what's going on and what is involved, observation, and upkeep...And, if you're not careful about following good common sense procedures, you can occasionally have a bad outcome. Shit happens- and it's not always good. That's part of the game. It's the reality of forging into new territory, but it contributes to the body of knowledge that is the aquarium hobby.

Okay, so that's my top four misconceptions about botanicals and botanical-style aquariums.

Of course, there are many others which arise from time to time- but those are "the big four" that we seem to hear about a lot. And, as we've seen, these are not entirely erroneous. However, it's important NOT to make assumptions about botancial materials, and to assume that they are "miraculous things" we can add to our tanks to do achieve smashing success.

The fact is, we still don't fully understand all of he affects- mostly good- but some possibly not so good- about the use of botanicals in aquariums. We have seen a LOT of instances of seemingly "spontaneous" (or at least, rather rapid) spawnings of fishes which have otherwise eluded the aquarists' efforts- shortly after introducing botanicals to their tanks.

Is this a result of some "substances" present in the botanicals? Is it a lowering of the pH in a softer-water aquarium? IS it those humic substances? Shock or some type of stress response? (!) Or could it be just a coincidence? It could be all of the above- however, I must admit that the number of times we've seen and heard this happen to us and others leads me to believe that there literally IS "something in the water!" Exactly what, of course- and how it influences these events is yet to be fully determined!

And isn't that just the kind of stuff that keeps hobbyists coming back for more...searching, experimenting, tweaking?

Yeah, it is.

And with more "technique" than ever before starting to replace the "dump and pray" method of using botanicals in aquariums, we're seeing more and more interesting results that simply go beyond just enjoying the unique aesthetics offered by blackwater, botanical-style aquariums. We're starting to see some interesting effects on the health and well-being of many species of fishes. We're learning about the value of replicating (to some extent) the natural conditions which our fishes have evolved under for eons.

And perhaps most important- we're taking a good, long look at many aspects of these precious- and often endangered- natural habitats. This search for knowledge and appreciation of nature will not only benefit the hobby, but quite possibly the ecosystem of our home planet, as we gain a better understanding of the dynamics of blackwater habitats and the need to preserve and protect them as havens of life.

Wow.

Oh, and we're having some FUN, too!

We're learning...together.

Breaking through the barrier of assumptions, hyperbole, misconceptions, and fluff that has often clouded this tinted world before we all came together and made a real effort to understand the function as well as the aesthetics of this dynamic, engrossing environmental niche.

Keep sharing your experiences- both good and bad.

Stay studious. Stay excited. Stay open-minded. Stay skeptical. Stay resourceful. Stay careful...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Another place and time...

As I think about the next aquariums I'm going to create, I find myself most interested not so much in a specific locale, as I am a "time." In other words, the season.

And all of the unique environmental dynamics and aesthetics which accompany it.

An aquarium which represents a time as much as it does a place. And evolves from there over an extended period of time.

When you think about it, this type of approach is quite interesting. Consider the differences in forest floors, grasslands, and even streams themselves at different times of the year. Varying water levels, chemical composition, temperatures, and even the types and quantities of terrestrial materials, plants, sediments, and rocks present will have a huge impact on the aquatic environment.

With such dynamic habitats to replicate in our aquarium, it seems to me that we should spend a lot more time exploring the way these habitats look and function at various times of the year. With influxes of terrestrial materials and pulses of water, there are a lot of variables in the environmental conditions from season to season, and the impact on the life forms which inhabit these niches is significant and interesting.

We should be recreating the conditions and the "function" of these habitats in our aquariums, to the best of our capabilities, as there is no doubt so much to learn from them.

Even the most basic variations in an aquarium habitat, such as the water level or temperature, are known to trigger reactions and behaviors such as spawning in many fishes. We've known this for some time, and breeders have done this sort of manipulation in controlled breeding tanks for generations. What are we not incorporating these changes- or at least, setting up aquariums to replicate various seasons- as a regular part of our hobby?

Well, some hobbyists are trying to capture the look, which they often do splendidly- but I wonder if they are actually attempting to recreate some of the dynamic conditions- the function- of these habitats- and managing them long-term in their aquariums. I hear very little of this, to be honest. And, with such a growing interest in biotope aquariums, and talented aquarists attempting them, it often leaves me scratching my head as to why this is not so.

The environmental data from many of the wild habitats we obsess over is readily available if you depart from the usual hobby articles and deep dive into research papers which are abundant online (Google Scholar, Research Gate, and many other places, for example). Sure, it might be more esoteric, "dry" reading- but once you get into this stuff, you'll find a treasure trove of information you can assimilate into your hobby. Most of these papers give not only location date, but the time of year, and detailed environmental conditions such as redox, light intensity (as PAR) and water movement that go beyond just pH and water temp.

The sort of genesis of this piece was based on a DM discussion I had with a member of our community, who questioned why I don't seem to speak more highly of, and (in particular) embrace the "culture" of some of those biotope aquarium contests. He felt that they were "right up my alley", and that it would be a natural for me to essentially sing their praises...and it was accompanied with some "constructive criticism" about why he thinks we should be more active with them than we are.

And he had some interesting points, but overlooked some fundamental ones that have sort of helped me formulate my position on such contests. Like, I'll just come out and say it...The attitude surrounding many of these contests just makes me want to vomit. Really. The work is great. Most of the people who enter and run them are wonderful and talented. Yet, there is a weird vibe, IMHO, which permeates them and simply turns me off. There. I said it. That's why I'm not running into the arms of these contests 24/7. I'm simply being brutally honest with you, as I have so many times here.

And sure, there is much good that comes out of these contests...but I think that there is substantial room for improvement.

Now, I realize that some of the biotope aquarium contests have entries which will be titled "Rio______, small tributary in November", or what not. And they are typically fabulous work, done with care and talent. They look great! And the aquarium is typically a nice representation of the habitat in question, accompanied by a tortuously detailed description of the wild habitat (written in that same "obligatory" fashion as those college term papers I used to dread...) And the 'scape is supposed to conform to some strict classification for the type of biotope the aquarium is purported to represent, which I suppose is cool.

I guess.

Hey, maybe that's another reason why I don't like these contests? They're like a flashback to everything I hated about school, lol.

All of this effort is great, and shows tremendous research and dedication. I applaud anyone who enters one of these draconian contests (yeah, I'm in full-on rant mode now) because they certainly do emphasize a bit of understanding of the habitats our fishes come from. I praise the contest organizers for that. Yet, for all of the emphasis on "XYZ River in October", does the aquarium represent just the look, or is there an attempt to represent the function of the habitat?

To really get down and dirty and sort out the fact that said river or tributary might have more turbidity in October, due to runoff from it's mother stream, or from a rivulet running through the forest. And this results in more algal growth, lower pH, or whatever. Stuff that not only influences the wild habitat, but has an impact on the creation and management of the aquarium as well. Over the longer term.

That's where the real magic lies, IMHO.

I mean, for all of the pretentiousness of the judging and accompanying criticism entrants receive (yeah, I think there is some), many of these contests simply fall back on the look of the biotope. You almost never hear about why there is more turbidity in the water in that habitat in certain times of the year, why the substrate has more silt or soil in it during the Summer, or whatever. And even less about how the aquarist actually manages said aquarium over the long haul.

Damn, I keep saying that, huh?

Okay, so I'm being a bit hard on the contest culture, I know. And almost any time anyone offers a personal opinion on this stuff, the defenders and haters come "a-callin'. This little "side rant" isn't really about hate or jealousy or what not. That's not the intent. You asked, and I'm explaining why I feel the way I do about soem of this stuff. And offering alternatives and suggestions. I don't "hate" them. The reality is that I greatly admire what they do-the talented work of the entrants, the efforts of the organizers, and more important, the emphasis on education they try to bring to the table. That's hugely important and cannot be understated.

Calling attention to the wonders of Nature is a big deal.

I suppose my problem with them is (liek so many things in the hobby), a dislike for attitudes.

As usual, I have great disdain for the pretentiousness and attitudes that often accompany these things, because I feel that they actually discourage some talented people from sharing their work with the world. And I think that so much effort is spent explaining why an entrant has to fall its on a specific category and such that we tend to see these become (again, in MY opinion) little more than very highly researched, well-presented aquascaping contests, with a tremendous attention to the look and conformity to some rules above all else.

Nothing wrong with that, if you represent it as such. Or, if you're into that sort of stuff.

I'd simply like to see more emphasis placed on maintaining and managing of these systems over a longer period of time- not just that they have the correct twigs and rocks when the photo is taken or the video is made. How about a more detailed description of how the system runs, the challenges of representing it,etc.?

Functional aesthetics.

Yes. here I go again, right?

Okay, I'm done "critiquing" these contests. They're cool...just not for me, I guess.

Rather than to unproductively trash contests, I just want to push us as hobbyists in general to go a little further to study the real dynamics of the wild habitats. To see them as more than simple "snapshots" in time, and more of a dynamic, ever-evolving system which can be managed over a long period of time, reflecting seasonal variations I the environment.

Yeah, I feel that we, as aquarists, can do a lot more to study and interpret the seasonal changes and variations which occur in wild aquatic habitats, in our tanks. We have the means to research, the equipment to use, and the fishes and natural materials to work with.

I think that part of the reason why we haven't seen a lot of these types of aquariums in the past is that they not only defy the pervasive sense of aquarium "aesthetic", but their "form and function" go against the grain in terms of what has been proffered as the "correct and healthy" way to run an aquarium for most of the century. And actively managing a tank like this is more difficult than "diorama- ing" it.

I mean, a lot of botanical materials decaying in an aquarium creates water quality management challenges that we as aquarists have to accept and meet. It's more than just a look. The art of maintaining a dynamic system over the long term, embracing, replicating, and managing the seasonal environmental variations is to me, a fascinating and challenging hobby endeavor. There is so much we really don't know about this, vis a vis aquariums- simply because we haven't approached it liek this very much over the years.

I've learned a ton from playing with my "Urban Igapo" tanks- enjoying the "seasonal" changes, environmental changes, and biological diversity that they bring.

And yeah- they look cool, too.

We can, and should do more in this area. Rather than just managing our tanks as "static" representations of an aquatic habitat, it might be a lot more interesting to run your aquarium on a more dynamic level- truly taking it to another place and time.

And if you want to enter it in a contest? Do it. Crush it.

And really emphasize the art of aquarium keeping, too- and how you manage your tank during these "seasonal changes." Not only will you educate fellow hobbyists (which has always been a great thing about these contests)- you'll challenge them to approach the art of aquarium keeping from a slightly different angle.

THAT seems like a winner to me.

Stay bold. Stay unique. Stay studious. Stay rebellious. Stay considerate. Stay collegial...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Botanical discoveries from our community...

After over 5 years of evolving Tannin Aquatics, decades of playing with leaves and twigs, and (hopefully), being one of the more vocal proponents of botanical-style aquariums, I've definitely learned a bunch of stuff, right along with all of you!

As a result of this, we've been able to determine some characteristics and "behaviors" associated with their use as dynamic hardscape materials. We may sound absurdly repetitive at times, but you -our customers and fans- want to know all of the ins and outs of this stuff, and we're happy to oblige! And thanks to your inout, we have a lot of good information to share!

We've been able to really "drill down" on a few things and I thought I'd share some of our "pearls of wisdom" based on my personal, and our community's observations on use of these materials in our aquariums:

1) Botanicals are not "forever" aquascaping materials.- We consider them ephemeral in nature. They will soften, break down, and otherwise decompose over time. Some materials, like leaves- particularly Catappa and Guava, will break down more rapidly than others, and if you like the look of intact levels versus partially decomposed ones, you'll want to replace them more frequently; typically on the order of every three weeks or so, in order to have more-or-less "intact" leaves in your tank.

On the other hand, if you're like me, and enjoy the more natural look that occurs as the leaves break down, keep 'em in. You may need to remove some materials if you find fungal growth, biofilm, or other growth unsightly or otherwise untenable.

Botanicals like the really hard seed pods (Sterculia Pods", "Cariniana Pods", "Afzelia Pods"), etc., can last for many, many months, and generally will soften on their interiors long before any decomposition occurs on the exterior "shell" of he botanical. In fact, they'll Miley recruit biofilms, which almost seem to serve as a sort of "protective cover" that preserves them.

Often times, fishes like Plecos, Otocinculus catfish, and other bottom-dwellers, will rasp or pick at the decomposing botanicals, further speeding up the process. Others, like ornamental shrimp, Apistos, and others, will pick at biofilms covering the interior and exterior of various botanicals, as well as at the microfauna which live among them, just as they do in Nature.

2) Virtually all botanical materials will impact the color of the water. -You'll find, as we have, that different materials will impart different colors into the water. It will typically be clear, but with a golden, brownish, or reddish tint. The degree of tint imparted will be determined by various factors, such as how much of the materials you use in your tank, how long they were boiled and soaked during the preparation process, and how much water movement is in your system.

Unfortunately, since these are natural materials, there is no set "X pods per ___ gallons of aquarium capacity", and you'll have to use your judgement as to how much is too much! It's as much of an "art" as it is a "science!"

3) If you really dislike the "tint", but love the look of the botanicals- You can mitigate some of this by employing a longer "post-boil" soaking period- like over a week. Keep changing the water in your soaking container daily, which will help eliminate some of the accumulating organics, as well as to help you to determine the length of time that you need to keep soaking the botanicals to minimize the tint.

Of course, it's far easier to simply employ chemical filtration media, such as activated carbon, and/or synthetic adsorbents such as Seachem Purigen, to help eliminate a good portion of the excess discoloration within the display aquarium where the botanicals will ultimately "reside."

4) You'll notice over time that many of the botanicals will "redistribute" throughout the aquarium- Yeah, they're being moved around by both current and the activities of fishes, as well as during our maintenance activities, etc. This is, not surprisingly, very similar to what occurs in Nature, where various events carry materials like seed pods, branches, leaves, etc. to various locales within a given body of water. In our opinion, this movement of materials, along with the natural and "assisted" decomposition that occurs, will contribute to a surprisingly dynamic environment!

5) Your aquarium water may appear turbid at various times- As bacteria act to break down botanical materials, they may impart a bit of "cloudiness" into the the water. Also, materials such as lignin and good old terrestrial soils/silt find their way into our tanks at times. One of my good friends, and a botanical-style aquarium freak, calls this "flavor"- and we see it as an ultimate expression of a truly natural-looking aquarium.

Yeah, the water itself becomes part of the attraction. The color, the "texture", and the clarity of the water are as engrossing and fascinating as the materials which affect it.

Need a bit more convincing to embrace the charm of the water itself in botanical-style aquariums? Simply look at a natural underwater habitat, such as an igapo or flooded varzea grassland, and see for yourself the allure of these dynamic habitats, and how they're ripe for replication in the aquarium. You'll understand how the terrestrial materials impact the now aquatic environment- fundamental to the philosophy of the botanical-style aquarium.

6) Just like in nature, if new botanicals are added into the aquarium as others break down, you'll have continuous influx of materials to help provide enrichment to the aquarium environment. - As hinted above, this type of "renewal" creates a very dynamic, ever-changing physical environment, while helping keep chemical changes to a minimum.

The fishes in your system may ultimately display many interesting behaviors, such as foraging activities, territorial defense, and even spawning, as a result of this regular influx of "fresh" aquatic botanicals. You could even get pretty creative, and attempt to replicate seasonal "wet" and "dry" times by adding new materials at specified times throughout the year...The possibilities here are as diverse and interesting as the range of materials that we have to play with!

The whole idea of using botanical materials in aquariums is not entirely new, as it has long been known that these natural materials provide various chemical benefits to the aquarium inhabitants.

However, the idea that these materials can help form the basis of a functionally aesthetic aquarium environment- one in which they form a direct influence on the chemical, physical, and aesthetic environment of the tank- is fundamental to our "practice."

A less rigidly aesthetically-controlled, perhaps less "high-concept" approach in the eyes of some- setting the stage for...Nature- to do what she's done for eons without doing as much to "help it along." Rather, the mindset here is to allow nature to take it's course, and to embrace the breakdown of materials, the biofilms, the decay...and rejoice in the ever-changing aesthetic and functional aspects of a natural aquatic system-and how they can positively affect our fishes.

We're seeing that not only do leaves, botanicals, and alternative substrate materials look interesting- they provide a physiological basis for creating unique environmental conditions for our fishes and plants. We're seeing fish graze on the life forms which live in and among the decomposing botanicals, as well as the botanicals themselves- just like in Nature...And we are seeing the influence- aesthetically and chemically- which these materials assert on the aquarium's environmental parameters.

With more and more hobbyists playing with botanicals and experimenting with as a foundational part of the aquatic environment, we're excited to see what kinds of creative ideas arise out of the botanical-style aquarium movement!

We look forward to seeing what you come up with! Embrace "the tint!"

Stay creative. Stay motivated.

And stay wet!

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Substrate confidential...Another look at the "stuff on the bottom..."

If you're a regular consumer of our content, you know of my obsession with varying substrate compositions and what I call "enhancement" of the substrate- you know, adding mixes of various materials to create different aesthetics and function.

You've likely seen my recent work with with different materials, like leaves, botanicals, clays, and sediments that I've shared with you here and elsewhere. It's an idea that I just can't get away from! In fact, it's something I'm borderline obsessed with!

Studies have shown that particle sizes tend to decrease the further downstream from the source they are found. Large rivers, such as the Amazon, have beds of shifting sands, slowly transported with the currents. Typically, the larger the item (pebble, rock, or boulder, the longer it tends to stay in one place. So, in a more powerful flow, you're more likely to find larger-sized materials.

The first recorded observations of bed material of the Amazon River were made in 1843 by Lt William Lewis Herndon of the US Navy, when he travelled the river from its headwaters to its mouth, sounding its depths, and noting the nature of particles caught in a heavy grease smeared to the bottom of his sounding weight.

He reported the bed material of the river to be mostly sand and fine gravel. Oltman and Ames took samples at a few locations in 1963 and 1964, and reported the bed material at Óbidos, Brazil, to be fine sands, with median diameters ranging from 0.15 to 0.25 mm.

There is a LOT to the science of naturally "graded" materials, and you'll have to do some research on the subject. In the end, science can tell you a lot; however, creativity and your aesthetic taste are typically the "guidelines" that you'll embrace to assemble your "slice of the bottom."

However, the physical composition of the substrate materials is but one aspect of these interesting aquatic systems...

The other, and perhaps equally fascinating part of the equation is the story of how the materials reach these streams and are distributed there. Yeah- no pice on the substrate composition of these habitats would be complete without a quick review of the streams themselves and how they arise and function within the broader ecology of a region.

Stream and river bottom composition is affected by a wide range of things, like regional weather, current, geology, the surrounding dry lands, and a host of other factors- all of which could make planning your next aquarium even more interesting if you take them into consideration!

If we focus on streams, it's important to note that the volume of water entering the stream, and the depth of the channels it carves out, helps in part determine the amount and size of sediment particles that can be carried along, and thus comprise the substrate.

And of course, the composition of bottom materials and the depth of the channel are always changing in response to the flow in a given stream, affecting the composition and ecology in many ways. Lighter materials, such as leaves, sediments, and twigs, will of course be redistributed by current and other factors. And of course, leaf litter beds, as we've discussed numerous times here, are one of the underwater world's most productive habitats- host to numerous life forms, ranging from fishes to fungi.

Some leaf litter beds form in what stream ecologists call "meanders", which are stream structures that form when moving water in a stream erodes the outer banks and widens its "valley", and the inner part of the river has less energy and deposits silt- or in our instance, leaves.

There is a whole, fascinating science to river and stream structure, and with so many implications for understanding how these structures and mechanisms affect fish population, occurrence, behavior, and ecology, it's well worth studying for aquarium interpretation! Did you get that part where I mentioned that the lower-energy parts of the water courses tend to accumulate leaves and sediments and stuff?

Likely you did! I mean, I'm pretty certain that you did!

The lower-energy parts of streams are often where the greater population of fishes and food items are found; and, they happen to be relatively simple to replicate in the confines of the aquarium. And the coolest part about this is that you can derive many of the same benefits from these litter beds in the aquarium as are found in Nature!

Permanent streams will often have different volume and material composition (usually finely-packed sands and gravels, with lots of smooth stones) than more intermittent streams, which are the result of inundation caused by rain, etc.

So-called "ephemeral" streams, typically occur only immediately after rain events (which means they usually don't have fish in them unless they are washed into them from more permanent watercourses). This is, of course, just another example of how weather and seasonal events affect not only the composition- but the very formation- of streams.

The latter two stream types are typically more affected by leaves, botanical debris, branches, and other materials. The substrates are typically littered with these materials, which are constantly being redistributed as water flows into and out of them.

In the Amazon region (you knew I was sort of headed back that way, right?), it sort of works both ways, with the rivers influencing the surrounding land...and then the land "giving" some of the materials back to the rivers...the extensive lowland areas bordering the river and its tributaries, known as varzeas (“floodplains”), are subject to annual flooding, which helps foster enrichment of the aquatic environment.

Although many streams derive their food base from leaves and organic matter, there is a lot of other material present that contributes to its structure. Think along those lines when scheming your next aquarium. Ask yourself what factors would contribute to the bottom composition of the area you're taking inspiration from.

You'll see a variety of bottom compositions in Amazonian and other streams, ranging from the aforementioned leaves and detritus in stream margins, to sand and silt over "cobbles", to boulders covered in algae, to fine patch gravels, root tangles, and even just silt.

You might even say that rivers and streams act like nature's "sediment sorting machines", as they move debris, geologic materials, and botanicals along their courses. And along the way, varying ecological communities are assembled, with all sorts of different fishes being attracted to different niches.

Interestingly, in most streams, the primary producers of the food webs that attract our fishes are algae and diatoms, which are typically found on rocks and wood wherever light and nutrients create optimum conditions for their growth. Organic material that enters streams via leaf fall is acted upon by small organisms, which help break it down.

It is probably no surprise, then, that bacteria (especially in biofilms!) and fungi are the initial consumers of the organic materials that accumulate on the bottom. Like, the stuff many of us loathe. These, in turn, are extremely vital to fishes as a food source. Hence, one of the things I love so much about utilizing a leaf litter bed as a big part of your substrate composition in an aquarium!

Streams which flow over stony, open bottoms, free from natural obstacles like tree trunks and such, tend to develop a rich algal turf on their surfaces.

While not something a lot of hobbyists like to see in their tanks (with the exception of Mbuna guys, some shrimp keepers, and a few true weirdos like me), algae-covered stones and rocks are entirely natural and appropriate for the bottom of many aquariums! Enter a tank with THAT in the next snobby, pretentious international "natural" aquascaping contest and watch the ensuing judge "freak-out" it causes! Oh, hell YES!!!

Grazing fishes, of course, will feed on and among these algal films, and would be logical choices for a stony-bottom-themed aquarium. When we think about the way natural fish communities are assembled in rivers and streams, it's almost always as a result of adaptations to the physical environment and food sources.

Now, not everyone wants to have algae-covered stones or a mass of decomposing leaves on the bottom of their aquarium. However, I think that considering the role that these materials play in the composition of streams and the lives of the fishes which inhabit them is important, and entirely consistent with our goal of creating the most natural, effective aquariums for the animals which we keep.

So, we've barely scratched the surface of the very bottom...However, I hope that I've helped click on the lightbulb in your head to consider that what goes on "down there" is every bit as important as any other part of the aquarium! There is plenty of scholarly research out there to draw on for inspiration and information to help you divise a plan.

Let's pay a little more attention to the "stuff on the bottom" in both our tanks and in Nature...because there's so much cool stuff to learn!

Stay curious. Stay creative. Stay excited. Stay inspired...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Moving beyond "realism": The next great hobby evolution

One of the things that sort of catches my attention lately is the increasing interest in what is being labeled as "realism" among the "high concept" aquascaping world. Like, taking some cues from natural habitats to incorporate in aquariums. Okay, this is huge, right?

Part of me is totally celebrating the move away from the strange "fantasy 'scape" crap that has dominated aquascaping for years now.

It's an interesting shift. An encouragung one.

However, the natural-style aquarium lover in me is still wishing we could prod them along a bit more. While it's an interesting and encouraging development, I can't help but observe some nuances in the "movement" which leave me wishing they'd go a bit further. Because the emphasis seems to be on only half of the equation.

Yeah, the interest seems to focus mainly on the look, as opposed to the whole picture; the function.

And yet, there is a push to make their "mountain/canyon 'scapes" more "realistic." Huh? WTF does that mean? I see tons of discussions on this "technique"- a lot of ideas about gluing rock together and gluing wood to rock to create unusual "canyons" and such..urghh!!! And of course, it begs the question to me...Are underwater mountain scenes "realistic" in tropical fish habitats to begin with?

Umm...

Can't these guys ever just look at a stream or something that tropical fishes actually reside in, and try to just kill it replicating that? Does it always have to be a photo of Olympus Mons on Mars, or K2 in the Himalayas, or something ridiculously non-aquatic that inspires them. So much talent working on- well, you get my point. Sheesh!

Chill, Fellman. Chill.

I mean, "baby steps", I suppose- but man, going just a bit further could yield so much more...

I guess it seems like nothing ever satisfies me, right? And who the fuck am I, right?

However...

I sometimes fear that this burgeoning interest in aquariums intended to replicate some aspects of Nature at a "contest level" will result in a renewed interest in the same sort of "diorama effect" we've seen in planted aquarium contests. In other words, just focusing on the "look" -or "a look" (which is cool, don't get me wrong) yet summarily overlooking the function- the reason why the damn habitat looks the way it does and how fishes have adapted to it...and considering how we can utilize this for their husbandry, spawning, etc.- is only a marginal improvement over where we've been "stuck" for a while now.