- Continue Shopping

- Your Cart is Empty

Doubling down on YOU: My case study.

Ever have one of those personal breakthroughs in the hobby? Perhaps it's just an epiphany, or maybe a development that gets you where you wanted to be after a long period of trying to figure it out?

Yeah,I had one of those recently; I'll share it with you later.

However, that "big picture" of self-awareness within the hobby is something I frequently discuss with fellow hobbyists.

One of the best things I've learned in the aquarium hobby is to be realistic about what I can and can't do well. The hobby challenges you and humbles you that way. And that's perfectly okay. Because, like with any endeavor, you can always improve at the craft. You can get good by simply trying, failing, learning, and persevering. It's pretty cool.

You CAN learn to breed fishes. Rear fry. Culture live foods. Plumb your reef tank. Test water. Build a dream company...

Etc.

Anyone can do those things well with time and dedication.

Although some things are a lot more difficult to "improve" at, IMHO. Some stuff requires that you have some skills that (I Know behaviorists out there will argue) you have to be born with...LIke the art of aquascaping, for example. I mean, sure, we ALL have some creative ability and art is really subjective. However, I the aquarium world, there are many hobbyists who seem to have that "X factor" nailed.

They are fabulous aquascapers. They could take the same branches and rocks that I have and create something universally appealing 99 times out of 100. That's amazing to me. You may not always like the style of their execution, but you can't argue with their skills.

I must admit, as I have many times- I'm not a very good "technical" aquascaper.

I couldn't properly arrange an "Iwagumi" rockscape to save my life. I'm about as bad at tying mosses to wood as they come. "Dutch Style"? C'mon! I can't even do "Benign Neglect Style" well! "Golden Ratio?" Heard of it. Diorama Style? Awed by the skills required; yet would rather keep hamsters than be good at that "style..." (okay, I AM opinionated, at the very least...)

Yeah, so anyways...

I know what my limits and skills are (the limits are many and the skills are few)...and I'm perfectly okay with that. Rather than try to mimic the 1,000 splashy 'scapes I see on my Instagram feed each morning, I do what moves me.

And I do it well.

And so do you.

Rather than try to mimic what someone else does so well, I've chosen to direct my aquascaping energies to what I love. I've doubled down on ME.

What I am is an "aquatic habitat interpreter" of sorts.

Yup. That's me.

I can look at an image of an aquatic habitat and try to recreate aspects of it in an aquarium. Not a stylized version, mind you. I can't do that well. Rather, an unfiltered interpretation of it. A version for the aquarium.

Now, part of the "interpretation" of natural habitats for an aquarium involves the "mental shifts" that I've told you about many times here. An acceptance that Nature is a perfectly imperfect place. A dirty, seemingly random, earthy place that, when one opens his/her mind to it, is filled with more beauty than 10,000 top Instagram feeds!

Patience, perseverance, and the willingness to try a few iterations to achieve what you're working on are super important.

And it helps to have some of the materials and tools to do the job! That's where we come in, and this personal story plays out.

As you all know by now, I have a strange obsession with the Igapo flooded forests of the Amazon. The tantalizing random mix of soils, leaves, roots, and botanical materials in water speaks to me. I have spent years gawking at these habitats, learning about them, and trying to figure out ways to represent them both aesthetically and functionally in the aquarium.

It's a habitat that has driven many of my aesthetic choices and aquarium environment experiments over the years. I've sourced materials, scoured scientific papers, and played with many dozens of aquariums over the decades trying to achieve that "functional aesthetic" balance, and to recreate, on some levels, the habitats I love so much.

I've played with various iterations of this habitat in various aquariums for quite a while. I feel like I really have a handle on some of the dynamics of this habitat and how to recreate a functional representation of it.

For some time, we have offered a material called "Senggani Root" as part of our "Twigs and Branches" selection. It's a rather unique material, with a thick little "trunk" and a delicate "filagree" of roots. It has a lot of potential for use in 'scapes, with its intricate matrix of space for fishes to forage amongst, microorganisms to reproduce in, and mosses to attach to.

It's awesome stuff.

When my supplier in Borneo approached me about carrying this stuff, there was no hesitation at all. It was love at first sight. However, it's also one of those materials that you can think about how to use, yet when it comes to executing, it's a bit trickier than you might think to get it right. The old adage about "listening" to the wood and it'll tell you how to use it rings true with this stuff.

I played with it for a while. We utilized it in several concept scapes, to great effect.

Yet, I knew that there was a different way I could use it.

For the longest time, I've had this vision of a root tangle on the floor of a flooded forest, reaching down among larger root structures towards an earthy, leaf-strewn substrate. I'd seen pics of this sort of thing in Nature and the temptation to do a representation of it haunted me. I have this little tank in my office that I've been dying to execute this in...

I started with a layout featuring a matrix of thicker nano-sized "Spider Wood" pieces as the "superstructure" for the scape. Of course, it needed some detail. It needed the more intricate, delicate look that only actual roots could provide.

What could I use? I needed something delicate, yet sturdy enough to last.

Aha! Finally, an opportunity for the Senggani root to play a part!

I figured that there was a way to work these more delicate, light-colored roots into the structure to create that sort of tangle.

With a little positioning and shuffling, three pieces of this branch were starting to give me the effect I was looking for all these years! A breakthrough of sorts! And the solution was right there in my facility all of these months...

You know when you just "feel it?" Yeah, that was me. I knew that I was finally moving in the direction I needed to be headed.

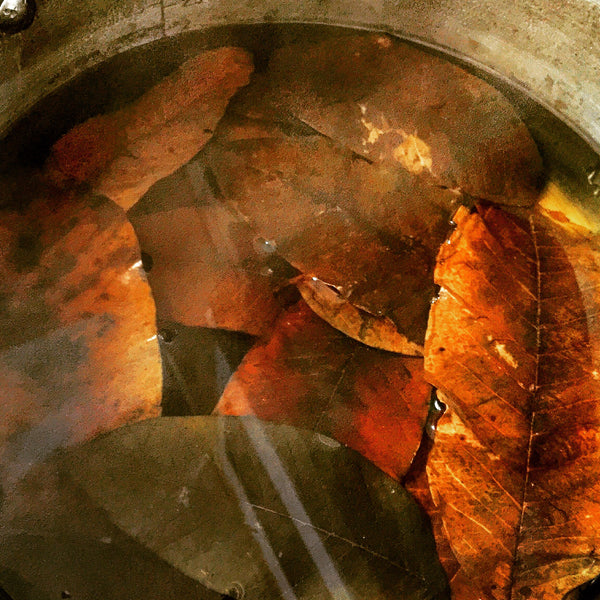

After a couple of days submerged, the addition of more soil, leaves, and bits of botanicals, and my "igapo root tangle habitat" began to emerge!

Those details- more leaves and botanicals, bits of Pygmy Date Palm fronds, crushed aquatic soil (I used Ultum Nature Systems "Control Soil"), and the passage of time, have yielded the look and hopefully, the function, which I've sought to achieve for so long. Once more of a "patina" emerges on the roots, and the biocover and "sediment" settle in on the Spider Wood and the slowly-decomposing matrix of botanicals on the substrate- I think I'll have what I came for!

The next steps will be done by Nature. She's in control from here. Decomposition, fungal growth, and the reproduction of microbial life in the aquarium will not only dictate how the microcosm functions, but how it looks as the tank matures.

My simple story here is nothing more than one of the many examples of why it's so important to "speak to your truth" and do what YOU love. If you try to do what "the crowd" thinks is cool or "it", you'll miss out on YOU. You'll never get to experience the joy of creating and sharing what you love.

Always double down on YOU.

Stay unique. Stay creative. Stay undaunted. Stay observant. Stay diligent...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Fascinating features; seldom replicated...until now.

It's interesting to me to contemplate ways to replicate unique ecological niches that we haven't played with all that much in the hobby. I mean, there is a lot of ground-breaking aquascaping work being done from the artistic perspective, and some amazing biotope aquariums replicating various locales and such, but some of the more odd or unusual microhabitats are seldom replicated, and I think it's sort of a shame, given the global talent pool, availability of materials, and interest.

I for one, would love to see more of these amazingly talented "artistic" 'scapers riffing on some of these interesting ecological niches.

As you probably know by now, we're big fans of habitats like leaf litter beds and flooded forest floors. Not just for the unique aesthetics that they present, but for the potential "functionality" these habitats bring to the aquarium. I think that these habitats, which host a huge variety of fishes, can be "foundational" for unlocking some new secrets of aquatic husbandry.

And by doing a bit of research on natural leaf litter habitats, you can glean some interesting tidbits of information that can be applied to aquarium design. And of course, you get perspective on the threats and challenges facing these habitats. Here's an example of one aspect of these habitats I learned about from a scientific study- the relationship between water depth and leaf litter depth- and how it can be applied to our aquarium designs:

In an area where the water depth was a maximum of 6ft/2 meters, the leaf litter depth was only about 8 inches/20cm. In a very shallow side tributary, the litter depth was about 4 inches/10cm, with the water level above it only about 12 inches/30cm!

That's like "aquarium depth", right? Yeah.

Now, these are just a few of many different areas affected by seasonal inundation, and there are numerous areas that are several meters deep during peak months. However, on the average, many of the little Igarape that I found information on were at best a meter or two deep, with correspondingly deep leaf litter beds.

Obviously, most of us aren't going to use an aquarium that is much more than a meter in depth, but we can always utilize the ratio of water to leaf litter/substrate and play with whatever dimensions excite us. Nonetheless, I'm a big fan of shallow/wide, because if you do build up a nice botanical/leaf litter layer, you don't have a huge column of water above, and can really focus on some of the bottom-dwelling fishes which make these areas home.

I think an ideal tank dimension for a leaf-litter biotope-style aquarium would be something like 48"x 18"x 16" /121.92cm x 45.72cm x 40.64cm (about 60 gallons/227.12 L)...shallow and wide, indeed! With these kinds of dimensions, you could create a leaf litter bed over a thin covering of fine, white sand, with a depth of about (4 inches/10cm) and a water column of about 12 inches/30cm above it. This proportion is a very good simulation of this type of habitat.

With a relatively low profile tank, you're not likely to feature "vertically-oriented" fishes, such as Angelfishes, in this tank! Rather, you'd focus on fishes like characins, including the leaf-litter dwelling "Darter Characins" like Aphyocharax, Elachocarax, Crenuchus, and Poecilocharax. For interest, you could introduce some biotipically appropriate Hoplias and Otocinculus catfishes, too. For the "upper" water columns, you could play with specimens of various Hatchetfishes and Pyrrhulina, killies like Rivulus, and cichlids, such as specimens of Apistogramma, Aequidens, and Crencichla.

Obviously, this is just a guide based on some studies of these areas, and you can create your own species mixes and even specialize in one or two featured species found in these habitats (that would be VERY cool!). The important thing, in my opinion, would be that you are attempting to create a few different aspects of these unique habitats. Filtration could be provided by either a canister filter or an outside power filter, with flow directed towards the surface.

Water temperature, based on studies, would be perfect if you could keep it at about 26 degrees C/78 degrees F. Now, the pH of many of these habitats that were surveyed averaged around 3.5-4.2- extremely acidic water with no real ionic content, that, as we've discussed previously, is something that is challenging to achieve, and equally as interesting to maintain (notice I said "interesting", because it's not impossible...just challenging). My little shallow leaf litter bed tank was able to maintain a pH of about 6.2-6.3. A far cry from the aforementioned 4.2, but not bad, from an aquarium standpoint!

Thusly, a modest-sized aquarium operated at low pH would be a great "testbed" for various types of research into the maintenance of these types of biotopes. Likely, you could "scale up" once you've mastered achieving your desired pH in a small tank.

Just one of many fascinating features of Nature, seldom faithfully replicated...until now. Let's see more of these unique ideas and replications!

Stay creative. Stay curious. Stay observant. Stay bold. Stay diligent...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Flooded forests, sunken grasses...emerging ideas?

I'll be the first to tell you that I'm not an aquatic plant expert. In fact, I know very little about them! However, I'd be inclined

The reality is that many of the (South American) habitats which we play with simply don't have much in the way of true aquatic plants in them. For example, the igapo flooded forests and small streams usually just don't have much more than epiphytic algae and submerged terrestrial plants in them.

However, you can grow plants in your "version", of course. I think it's more of a matter of trying various plants which tend to come from lower ph, blackwater habitats, and applying these ideas to their care. My list is ridiculously superficial, of course- so you hardcore plant people will have to take the flag and run with this!

(The Red Howler Monkey knows a thing or two about Amazonian plants and trees! Image by Gordon E Robertson, used under CC BY-SA 3.0)

Now, my other "challenge' to plant lovers in general: Let's figure out which terrestrial plants can tolerate/grow/thrive under submerged or partially submerged (blackwater) conditions. Perhaps a more "realistic" (not in the hardcore "biotope aquarium contest" context, of course) avenue to explore in this regard?

I've got one tree for you to research...the dominant terrestrial plant in this habitat is Eugenia inundata... Don't think I'm not well underway in my (somewhat futile) efforts to see if we can secure fallen leaves of THIS plant! You'll also find Iriartea setigera, Socratea exorrhiza, Mauritiella aculeata palms in these areas..

(Mauritiella aculeata - Image by pixel too used under CC BY 2.0)

Like so many things from the Amazon, it's not easy (read that, damn near impossible) to secure botanical material from this region, so the proverbial "Don't hold your breath waiting for this" comes to mind! Oh, and the submerged grasses we see and drool over in those underwater pics from Mike Tucc and Ivan Mikolji of these habitats?

They're typically Paspalum repens and Oryza perennis.

Paspalum is found in North America, too...possibly a species you could obtain?

(Paspalum. Image by Keisyoto. Used under GFDL)

Perhaps you could, right? And it's that kind of stuff that keeps us working away.

Simple idea for today...

Stay curious. Stay excited. Stay engaged. Stay diligent...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Accumulating detritus, "mulm", or whatever you call it- moving minds.

Remember from your hobby history (or for some, from your personal experience) those charming aquarium books from the late 1950's/1960's, arguably the hobby's "Golden Age?"

One word I remember seeing in many of these books was "mulm." It was a funny word. A sort of 1950's-60's-style catch-all expression for "stuff" that accumulates at the bottom of an aquarium.

Charming, even.

It was- is- quite appropriate and descriptive!

"Mulm" is similar to the catch-all term of "detritus", which is used in the hobby extensively to describe the solid material that accumulates at the bottom of an aquarium as the end product of biological filtration.

"Mulm", however, is a bit more...

I think mulm is also that "matrix" of stringy algae, biofilms, and fine particles of "stuff" that tends to accumulate here and there in healthy aquariums, What's cool about this stuff is that, not only do you see it in aquariums- you see it extensively in natural ecosystems, such as tropical streams, flooded forest floors, and ponds.

In the case of a botanical-style aquarium, "mulm" is also the broken-down leaves and botanicals. It's a part of what we love to call "substrate enrichment" in our aquariums. Stuff that physically comprises the bottom of the tank! As botanicals break down- just like in nature, they create a diverse matrix of partially decomposing plant materials, pieces of bark, bits of algae, and some strings of biofilm.

I mean, I suppose if you want to get all technical and geeky about it, you could refer to a solid definition of "detritus" and work from there:

"detritus is dead particulate organic matter. It typically includes the bodies or fragments of dead organisms, as well as fecal material. Detritus is typically colonized by communities of microorganisms which act to decompose or remineralize the material." (Source: The Aquarium Wiki)

Woah!

Okay, that sounds pretty "official..." I mean, it's one of our most commonly-used aquarium terms...and one which, well, quite frankly, sends shivers down the spine of many aquarium hobbyists, and just flat-out scares the shit out of others! And judging from that definition, it sounds like something you absolutely want to avoid having in your system at all costs. I mean, "dead organisms" and "fecal material" is not everyone's idea of a good time, ya know?

Yet, when you really think about it, "detritus" or "mulm", if you want to differentiate- are an important part of the aquatic ecosystem, providing "fuel" for microorganisms and fungi at the base of the food chain in tropical streams. In fact, in natural blackwater systems, the food inputs into the water are channeled by decomposers, like fungi, which act upon leaves and other organic materials in the water to break them down.

In years past, as well as today, those of us who favore "sterile-looking" aquaria will be horrified to see this stuff accumulating on the bottom, or among the driftwood. Upon discovering it in our tanks, for many hobbyists, it takes nanoseconds to lunge for the siphon hose to get this stuff out ASAP!

In our case, we embrace this stuff for what it is: A rich, diverse, and beneficial part of our microcosm. It provides foraging, "aquatic plant "mulch", supplemental food production, a physical place for fry to shelter, and it's a vital, fascinating part of the natural environment we are working to foster in our tanks.

It is certainly a new way of thinking when we espouse not only accepting the presence of this stuff in our aquaria, but actually encouraging it and rejoicing in its presence! Why? Well, it's not because we are thinking, "Wow, this is an excuse for being lazy and maintaining a dirty-looking aquarium!"

No.

We rejoice- because our little closed microcosms are mimicking exactly what happens in the natural environments that we strive so hard to replicate. Granted, in a closed system, you must pay attention to water quality, but accepting decomposing leaves and botanicals as a dynamic part of a healthy, closed ecosystem is embracing the very processes that we have tried to nurture for many years by removing every drop of the stuff!

Sure, it's a very different aesthetic: Brown water, leaves, stringy algae films, and botanical debris. We may not want to have an entire bottom filled with this stuff...or, maybe we might!

I think that there is a serious distinction between the idea of letting some natural processes play out in the aquarium, and not rushing to remove every gram of detritus from our tanks immediately, and allowing some of it to fuel beneficial biological processes.

I'll admit that, to most modern aquarium hobbyists, the stuff just doesn't look that nice, and that's at least partially why the recommendation for a good part of the century or so we've kept aquariums has been to siphon it the hell out! And that's good advice from an aesthetic standpoint- and for that matter, from a husbandry standpoint, as well. Well, typically. If it creates good habits and encourages observation and diligence in tank management...On the other hand, why are we so militant about removing the stuff at first sight?

I mean, is this material causing a problem for your fishes? Or does it just look yucky?

How do you know if this stuff is really a "problem" in your aquarium?

Well, first, get back to the basics. Is your "detritus" or "mum" a matrix of uneaten food, or a less-menacing mix of botanical "fines", fish waste, and biofilms? If it's uneaten fish food, well- feed less...right? That's not "detritus accumulation"- it's overfeeding. Straight-up.

Check your water parameters.

Are you seeing surging nitrate or phosphate levels? Excessive growths of algae? Do you have any detectible ammonia or nitrite? Are the fishes healthy, relaxed, eating, and active? If the answer to the first two questions is "no", and the last is "yes"- then perhaps it's time to simply enjoy whats happening in your aquarium! To accept and understand that the aesthetic of a heavily botanical-influenced system is simply different than what we've come to perceive as "acceptable" in the general aquarium sense.

It's not for everyone.

It's not something that we are used to seeing. I totally get this.

And yeah- if you're experiencing issues with your aquariums and the health of your fishes under these circumstances, it's time to review those basics yet again. Think about an aquarium as a sort of "balancing act"- trying to not have too much or too little of anything.

It's a challenge for some of us to achieve that "balance", as it's been known as.

However, the feedback we've been getting from you- our customers- regarding the systems you've set up in this fashion is that they have created an entirely new perception and understanding of a freshwater aquarium. They've enabled us all to try a completely different aesthetic experience, and more important- to understand and encourage processes that occur naturally, which are of great benefit to the fishes we keep- despite long-held beliefs or aesthetic assumptions about what is "good."

Since we've started Tannin, we've heard a lot of stories from hobbyists of successful spawning and rearing of fishes that have proven challenging in the past. We've hear of hobbyists being extremely skeptical and, well- even a bit turned off by what was happening in their water- and then waking up one day and noticing that their fishes have never looked better- never acted more "naturally"- and that visitors to the fish room are fascinated by the "brown tank" that was recently set up...drawn to it.

I've seen this before many times, myself.

I'm not sure why..I don't know if it's simply because these types of tanks are such a radical aesthetic departure from what we're used to, or if it's something more?

Perhaps, we're somehow drawn to their earthy, "organic" vibe?

Perhaps there is something "liberating" about allowing our aquariums to look and work as Nature intends them to; to embrace form and function- rather than to wage war with anything that challenges our ingrained "aesthetic sensibilities?"

I'm not sure.

But I am sure that I'm enjoying my tanks, and so are many of you who have tried this approach. You're having a lot of fun- even with "mulm" in your tanks. Or "detritus"- or...whatever the hell you want to call it.

And fun is what it's all about!

Stay open-minded. Stay curious. Stay studious. Stay bold. Stay diligent. Stay observant...

And Stay Wet.

Scot Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Botanical "expectations": Mindset shifts. Discoveries...and Evolutions.

The world of botanical-style aquariums is really starting to gain wider exposure and acceptance in the aquarium world. Although, as we've said for years, it's not something that is necessarily "new", or was "invented" by any one hobbyist or company. No one can "claim" the "idea" that Nature has perfected over eons. However, I think it's a concept that is getting a fresh- or even a first- look by many hobbyists.

And yes, it's a "concept"- or really, a "methodology", with its own set of practices, techniques, and expectations. And it's important to go beyond just looking at the use of botanicals as "hardscape pieces" to accent our aquascapes. what we have come to call "functional aesthetics" looms large in the world we operate in.

If you've started working with botanicals in your aquariums over the past few months, you've probably gained an awareness that, although these are unique and aesthetically beautiful aquariums, like any other methodology, they are not "set and forget" systems. Because of the very nature of botanicals and how they interact with their environment, you need to regularly observe, evaluate, "scrub", or even replace them as needed. You'll need to understand the progression of things that happen as your tank establishes itself. And, perhaps most important, you'll need to make some mental "adjustments" to accept and appreciate this different aesthetic.

We've talked on numerous occasions about the various "stages" through which a botanical-style (somewhere along the line, I referred to them as "New Botanical-style" aquairums) aquarium progresses as it matures and settles in, which includes recruitment of biofilm, algae, and the physical "softening" and eventual breakdown of the botanicals themselves. We have all come to understand that the materials will interact the aquatic environment directly, imparting tannins, humic substances, and other organics into the water. We like to characterize botanicals as "dynamic" materials, as they are hardly "static" or "inert" in nature!

All of this adds up to a system that requires observation and management...Which, really, is no different, no more challenging, and probably even less mentally taxing than say, a "high tech" planted system or a specialized breeding setup for fishes like Discus or Angelfish. Like any system, the botanical-style aquarium requires some specific observation and maintenance practices in order to keep it performing at an optimum level for its inhabitants.

Is there a real "timetable" for how one of these tanks progresses? Well, more or less. At the very least, there is a somewhat predictable set of expectations we can work with, and practices to engage in:

Startup-first 3 weeks: Observe botanicals to make sure that they are remaining "negatively buoyant" (i.e.; waterlogged!). Remove any which appear to be floating or present a putrid, "rotten egg-like" smell. (yeah, some will on occasion). Depending upon your water chemistry, the quantity of botanicals being used, and the filtration media employed, you'll start to see the water "tint" after a few days, reaching its maximum after about 2-3 weeks. Now, despite our love of the color, it's important to perform regular water changes and other maintenance like you would on any other aquarium during this time.

One month- two months: This is when you'll likely see the maximum growth of biofilms and fungal growth on the botanicals. This is a part of the "game" where we can separate the hobbyists who understand this process and those who have not done their homework, so to speak. As we've discussed numerous times, biofilms are a completely natural and expected part of utilizing dried botanical materials in an aquarium. The "aesthetics" of this process is not everyone's idea of "beautiful"- and that's understandable.

However, it's a normal, natural, part of the game.

Biofilms will always be present to some extent during the lifetime of your botanical-style aquarium. We need to accept this. During the initial phases, you have several options. You can physically scrub the biofilms off of the botanicals as needed (accepting the fact that they will likely reappear), or employ "biological controls" (such as ornamental shrimp, snails, or even Otocinculus catfish) to help with this process. In fact, many fishes will forage upon biofilms as part of their diet. Although they are efficient, you shouldn't expect the animals to get everything. You can assist with the removal of any offensive materials or...wait it out.

Two months-four months: By this time, your aquarium has no doubt settled into a comfortable, stable situation, and hopefully you've come to appreciate the more natural appearance of your system. Some of the softer, more "transient" botanicals, such as leaves, will likely have broken down significantly at this point, and no doubt need replacement. That's another point...as in Nature, to keep a consistent environment, you'll need to replenish leaves and botanicals as they decompose.

You need to employ regular maintenance practices, such as water exchanges, filter cleaning/media replacement, etc., and monitor water chemistry parameters like you would in any other tank. By this time, you'll come to recognize what is "normal" for your system, and any deviations from the norm will become more obvious to you.

As a "side note" on maintenance- you can "condition" your replacement water for water changes by soaking some prepared Catappa leaves in the storage containers for several days prior to use. This creates a certain degree of consistency, and of course, adds that "tint" to the water.

Evaluate your tank periodically and decide if you want to exchange or simply add some new botanicals to your system. There is no exact "science" to this; like with so many things we do in aquariums, it will require you to "go with your gut" and make decisions based upon what your goals are, and what by now you consider "normal" for your system.

After a few months, it's likely that you'll either just love this style of aquarium, or you'll decide it's not for you. Perhaps the tinted water, decomposing materials, and earthy appearance are something that speaks to you...I hope so!

Obviously, this is not a comprehensive treatise on the management of a botanical-style system. It is, however, meant to serve as a very rough guide as to what typically happens during the early life, and what to expect with such an aquarium. Your experience may vary slightly, but these observations were made based upon my own experiences and others who have worked with these types of aquariums for years.

It's intended to serve as a "cue card" for you to understand the various phases of your aquarium, and what may be expected. Depending upon many factors, such as your base water chemistry, maintenance practices, filtration, etc., the timeline may be longer or shorter, but the "markers" are typically the same.

In the end, one conclusion you can draw from this brief review is that these types of aquariums are by no means difficult to create or maintain; and in fact, once established and stable, may prove to be some of the more simple systems you've worked with! You just need to learn the "rules" as Nature has established them, and to manage expectations based on this knowledge.

Probably the biggest adjustments you need to make are mental ones. You need to accept that this type of tank will look and function fundamentally different than other types of systems you've maintained. Obviously, the tint of the water is the most obvious. This can be managed, to a certain degree, by employing activated carbon, Purigen, or other chemical filtration to remove some or all of the "tint" as desired.

Also, you'll have to get used to a certain amount of material decomposing in your tank. It's natural, and part of the aesthetic. Accepting the fact that you'll see biofilms and even some algae in your system is something that many aquarists have a difficult time with.

This is not an excuse to develop or accept lax maintenance practices. It's simply a "call to awareness" that there is probably nothing wrong with your system when you see this stuff. It's quite contrary to the way we've been "acculturated" to evaluate the aesthetics of a typical aquarium.

Observe underwater videos and photos of environments such as the Amazonian region, etc. and you'll see that your tank is a much closer aesthetic approximation of nature than almost any other system you've worked with before! And, to your comfort, you'll find that these systems are as "chemically clean" as any other if you follow regular maintenance and common sense.

The realization that it's perfectly natural and entirely consistent with the nature of these environments to have some of this stuff present is likely little comfort to you if you just can't handle looking at a field of "yuck" on your botanicals. I can't stress enough the need to make that "mental shift." As we discussed, management of this stuff is entirely up to you and what you can tolerate. Generally, the biofilms and algae are self-limiting, ultimately disappearing over time as the compounds that fuel them diminish or attain levels that are not sufficient for their growth, or as a result of animals consuming them- or a combination of both.

The decomposition of "transient" materials like leaves and softer pods, etc. is simply part of the natural dynamic, and will continue as long as you choose to employ these materials in your aquascape. If you observe carefully, you may note spawning and other "grazing" behaviors in your fishes, and note that they are spending significant time foraging though the broken-down matter, much like in nature.

Ultimately, the decision to create a "botanical-style aquarium is as much a philosophical one as it is a practical one. To accept nature, rather than to fight it, is a bit at odds with the mindset many of us have with regards to aquarium keeping. As you begin to understand and evaluate your own aquarium, you'll gain a greater appreciation for the wonders of nature, and the processes that have occurred for eons.

Stay open-minded. Stay adventurous. Stay curious. Stay diligent...

And stay wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

"Like Nature in Form and Function..."

I was playing with a small tank the other day, in a rare moment of fish geek "free time" I created, and I was playing with (of course) some leaf litter, within a "bramble" (for want of a better word) of wood. And setting in the leaves, which is pretty much a theme of mine in every tank, I recalled the studies I've done on how botanical materials distribute themselves in natural aquatic habitats.

And this is something to consider in aquarium keeping, particularly for those of us who embrace the idea of creating simulations of these wild habitats. There are a few considerations, believe it or not-including simply how they "fall" in our aquascapes, and the impact which they have on our fishes while they're physically present in our aquariums.

And it's important to recognize the fact that a bed of leaves and botanicals on the bottom of your tank is not just a "static" part of the aquarium. Fish movement, current, and the random movement that occurs when you accidentally redistribute botanicals in your aquariums during maintenance, you create unique new "microhabitats" for your fishes. And that's exactly like what occurs in Nature.

A simple thought- but profoundly important, really. And readily apparent to all who play with leaves and botanicals. Something to think about and consider.

I love this topic (and fortunately, a lot of hobbyists like you are as geeked-out as I am about it, too!) because it's one of those things that most of us don't even think of in terms of our aquariums, and it's only now becoming a "thing" as more of us play with these materials! The idea of actual "beds" of leaf litter and such on the bottom of our aquariums, although not some quantum leap in aquarium keeping, hasn't been discussed all that much over the years.

When you think about how materials "get around" in the wild aquatic habitats, there are a few factors which influence both the accumulation and distribution of them. In many topical streams, the water depth and intensity of the flow changes during periods of rain and runoff, creating significant re-distribution of the materials which accumulate on the bottom, such as leaves, seed pods, and the like.

Larger, more "hefty" materials, such as submerged logs, etc., will tend to move less frequently, and in many instances, they'll remain stationary, providing a physical diversion for water as substrate materials accumulate around them.

A "dam", of sorts, if you will. And this creates known structures within streams in areas like Amazonia, which are known to have existed for many years. Semi-permanent aquatic features within the streams, which influence not only the physical and chemical environment, but the very habits and abundance of the fishes which reside there.

Most of the small stuff tends to move around quite a bit... One might say that the "material changes" created by this movement of materials can have significant implications for fishes. In the wild, they follow the food, often existing in, and subsisting off of what they can find in these areas.

the case of our aquariums, this "redistribution" of material can create interesting opportunities to not only switch up the aesthetics of our tanks, but to provide new and unique little physical areas for many of the fishes we keep.

The benthic microfauna which our fishes tend to feed on also are affected by this phenomenon, and as mentioned above, the fishes tend to "follow the food", making this a case of the fishes learning (?) to adapt to a changing environment. And perhaps...maybe...the idea of fishes sort of having to constantly adjust to a changing physical (note I didn't say "chemical") environment could be some sort of "trigger", hidden deep in their genetic code, that perhaps stimulates overall health, immunity or spawning?

Something in their "programing" that says, "You're at home..." Triggering specific adaptive behaviors?

I find this possibility fascinating, because we can learn more about our fishes' behaviors, and create really interesting habitats for them simply by adding botanicals to our aquariums and allowing them to "do their own thing"- to break apart as they decompose, move about as we change water or conduct maintenance activities, or add new pieces from time to time.

Again, much like Nature.

Like any environment, leaf litter beds have their own "rhythm", fostering substantial communities of fishes. The dynamic behind this biotope can best be summarized in this interesting excerpt from an academic paper on Blackwater leaf-litter communities by biologist Peter Alan Henderson, that is useful for those of us attempting to replicate these communities in our aquaria:

"..life within the litter is not a crowded, chaotic scramble for space and food. Each species occupies a sub-region defined by physical variables such as flow and oxygen content, water depth, litter depth and particle size…

...this subtle subdivision of space is the key to understanding the maintenance of diversity. While subdivision of time is also evident with, for example, gymnotids hunting by night and cichlids hunting by day, this is only possible when each species has its space within which to hide.”

In other words, different species inhabit different sections of the leaf litter, and we should consider this when creating and stocking our aquariums. It makes sense, right?

The big takeaway: A leaf litter bed is a physical structure, temporal though it may be- which functions just like a hardscape of wood, a reef, rocks, or other features in the benthic environment, although perhaps "looser" and more dynamic.

I think that's the best way to look leaves, IMHO.

Much like in Nature-in both form and function.

Stay curious. Stay resourceful. Stay diligent...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Trend spotting...Scheming, and inspiring...

The other day, I saw a leaf fall off one of the mangroves in my brackish water aquarium, and it landed perfectly on the substrate, right near a mangrove root and a little pile of decomposed mangrove leaves. You know, "detritus." And, rather than freak out (which I'm NOT prone to doing about such things, btw), I thought to myself, "Damn, that looks pretty natural! And gorgeous"

I wonder how many other people consider something like that beautiful. Or even "tolerable."

As someone who considers himself a fan of unique aquairums, and aficionado of fishes, and a consumer of aquascaping content, I am always eager to see the work being done by hobbyists worldwide. It's neat to see the amazing creativity that is applied towards creating unique aquarium displays.

Let's be honest, "trends" (yuck, I really hate that word, but it applies) emerge over time. Example? The latest one is for pieces of wood to break the waterline of the aquarium. I mean, this is not exactly a revolutionary idea, but it's just sort of become a "thing" of late in the aquascaping world. I mean, it's not like it's something we saw quite a few years ago- at least not all that often.

And when I see tank after tank after tank on Instagram or wherever, with the driftwood boldly projecting out above the waterline, looking for all the world like a deer's antlers ('cause that's how people seem to arrange their wood these days), I start wondering how stuff like this becomes "a thing" in the first place? I mean, one guy does it, people freak, and it's on "The 'Gram"...and next thing you know, three other people feel that they have "premission" to try it because the famous guy did, and...well...Yeah.

We're liberated from the "waterline limitation.."

Next trend...all "rock and rubble scapes."

I see it. I'm calling it here. More rock. Just you watch. Seriously. I see the signs. Give it three months. Four, tops.

If I'm wrong, you can scold me then.

And look, the executions are brilliant in most cases. Really artistic. Really well done. And...well...entirely imitative of each other. After you've seen the first 47 of them, the other 163 just sort of look...well- the same.

Yep.

Nothing wrong with that. It's just interesting to me what catches the eye of the aquarium world nowadays. What the inspirations are.

How about Nature?

Outside of the super-hardcore biotope aquarium crowd, we see virtually no incorporation of what a natural aquatic habitat really looks like in the world of "trendy aquascaping" (Now I"m just calling it as I see it.). Arranging rocks like the Grand Canyon or whatever is NOT incorporating the natural aquatic habitat into the 'scape. Let's not fool ourselves. Being inspired by a mountain range or alpine forest, and modeling the 'scape after these "scenes"- gorgeous though they are- cannot really be called a representation of a natural aquatic habitat.

And that's okay. Again, it's art. It's interpretation. And it's typically beautiful.

But it's not the "beauty of Nature" that we see in these scapes. Or, more properly- the beauty of a natural aquatic habitat. And in a world that seems to be constantly searching for the next big thing to inspire, there seems to be an almost blatant disregard for the very thing that is the ULTIMATE source of great ideas: Nature, and the aquatic habitats she creates.

Why is this?

What is it that makes these hyper-talented artists- cause that's what they are- resistant or, as one of my friends says, afraid- to simply look at a stream, a pond, a flooded forest, a vernal pool- whatever- and just replicate or draw inspiration from that?

Is it because "it's already been done" (by Nature, lol)?

I wish I knew.

If I had 1/100th of the talent of some of these people, I'd be causing an aquascaping revolution. Seriously. Or at the very least, I'd be pissing off a lot of contest fanatics! I'd be replicating shit like vernal pools, tracks in the African rain forest, marginal rainforest streams in Borneo, Congolese river banks, Igarape in Brazil, rice paddies in Myanmar, etc., etc., etc.

Yeah.

I mean, I try, but I admit, I simply don't have the artistic talent of some of these guys. ("jealous much, Fellman?").

I do have an eye for the function and aesthetics of these habitats, and a fascination to do more than just create a static natural scene. I want to replicate the actual habitat, in all of its "natural-ness"- that means, with tinted water, turbidity, detritus, decomposing leaves, root tangles, muddy substrates, etc.

And I think that a lot fo you do, too. I've seen some works that merge art and Nature beautifully, and in an inspiring way.

And it doesn't have to be pretentious, either. You know- the whole "biotope contest- this has-to-be-100%-precise-to-be-cool" thing: "The Japurá River- late Spring, 32km from Manaus at low water level.." You've seen that stuff. It's cool, but it's specific enough to turn a lot of people off, scare casual hobbyists away, or just make others laugh a bit.

It just has to be inspired by the natural habitats in form and function.

I just think that would be so cool! Imagine if we merge the obsession of the biotopes with the artistic passion of the competition aquascaper, and the diligence of a breeder.

Hey, it's possible. I mean, that's you guys, right?

What if we simply looked at the millions of possibilities that Nature provides if we look at the amazing scenes that are effortlessly created by her processes. Wouldn't attempting to replicate the form and function of such a system in the aquarium be at least as challenging, beautiful, and satisfying as creating an underwater "beach theme" or sunken "Grand Canyon?"

Yes.

After the initial "Ohmigod, the sand isn't perfectly white!" and, "Isn't that...a decomposing leaf?" or..."Holy #$%&! Those are random twigs covered in biofilm..what the f----?"- would there be an effort to consider why these things were present in the 'scape, and how they truly represent Nature as she exists? Any desire to research the wild habitat that the tank was purported to replicate, and understand the complex interactions between the fishes and their environment?

Maybe? Hopefully?

Imagine what it would do to one of those pretentious contests if someone entered an aquarium that was a functional and aesthetic representation of a muddy African vernal pool or Pantanal watercourse, choked with marginal vegetation, clays, and an appropriate mix of fishes. One that has been up and functioning for a few months or longer.

One that might have had some challenges beyond "that one rock that keeps slipping out of place..." One that requires us to utilize natural materials in a manner which affects their biological function and influences the environment in ways not previously considered. One that the aquarist doesn't have to hold up a blow dryer over the tank to make ripples for "special effects." One that shows a functional represntation of a specialized aquatic habitat- with all of it's delightful "imperfection" that makes it so...perfect!

Isn't that what a "natural aquarium" is? Isn't that what even the great Takashi Amano himself talked about for so long, all those years ago? An idea seminal to his approach, yet an idea that was somehow lost in the mists of time, and in the frenzied race for the perfect "Middle Earth" diorama scape?

Yeah.

Imagine aquaecapes inspired exclusively by the natural aquatic habitats of the world, instead of last month's "tank of the month." One that has it's aesthetics dictated as much by how it functions as it does by the way the materials are arranged.

Nature provides quite the "look book", with an agenda and challenge all her own. One that forces us to go beyond just the superficial "look" and to see how to create function and let go of some of the preconceived notions we have about what we think things should be like...one that forces us to accept how they are.

And to be awed. And inspired in a different way.

A promise to you: At Tannin, we're going to double down on Nature this year.

With more inspiration, more materials, and more ideas to help you create the functional aesthetics of the earth's unique natural aquatic habitats. Sure, there may be some cool 'scapes to inspire you. There will definitely be more imagery of the natural habitats. And there will definitely be some challenges to move past what passes as a mere trend.

Here's to Nature.

And to YOU.

Stay inspired. Stay creative. Stay resourceful. Stay diligent. Stay awed...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

The things within our control...

I was talking with a friend the other day, who had a "mysterious" set of deaths in one of her tanks...After the usual fish geek analysis of the tank and the procedures used to maintain it, she realized that she had a heater go bonkers and cook her fishes, then fail completely. We concluded that it was a circumstance that was likely beyond her control.

Tough blow...but one of the many things we can't do much about in the hobby, right?

When you think about it, the aquarium hobby has a lot of things in it which are within our ability to control, many things which are a matter of "luck", and a bunch of stuff that were pretty much have no say in whatsoever, right?

I mean, we CAN control stuff like the size of the tank we use, the number of fishes we add, how we equip and manage our tanks, and what we feed them. We can control the environment...like, to the point where there is little excuse for mass fish "extinctions" except human error.

We choose not to quarantine. We choose not to make that water change, add that one more fish, skip the filter cleaning this week, etc. The good (or bad) results that arise out of these decisions are completely on us, right?

Disease outbreaks from adding that ONE fish you skip quarantine on are totally your fault.

Ouch.

Now, some stuff is not completely on us:

We can't control stuff like how our fishes were handled on the chain of custody between the collector to the LFS. We can't control the decomposition rate of botanicals within our aquarium. We cannot control how our fishes will respond to environmental changes.

However...

We CAN control where we purchase our fishes, and make the effort to understand who their suppliers are and the quality control efforts taken to assure that our specimens arrive in the best possible condition, given the rigors of transport. We CAN control how many botanicals we add into our aquarium at once. We can control the environmental changes that affect the well-being of our fishes...

The moral of this short and relatively simple discussion:

Do the best you can to control the stuff that you CAN control in your aquariums, and do the best you can to find out why something that was beyond your control failed.

And by the same token, it's always great to figure out why you're having that spectacular success! And usually, a lot more obvious, too! And fun!

Today's absurdly simple thought.

Stay curious. Stay diligent. Stay engaged. Stay obsessed...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Brown and Brown and...brown. Approaches, techniques...and the implications of shortcuts...

We sure exist in a funny world, huh?

One of the things I read about from time to time in various hobby social media discussions is the dislike many people have for the tint that wood and such impart into the water.

In fact, some of the posts we see on social media or aquascaping/plant forums are literally pleas for help...stuff like, "When will this brown tint go away?"

I see that kind of stuff and- jerk that I am- kind of laugh.

And that is pretty mean of me, I know.

Sure, I get it. Not everyone appreciates, likes, or even has the remotest interest in the earthy brown water that we obsess over around these parts! Yet, it was these unfortunate souls who made me realize the fastest, easiest way to "jump start" the tinted look in your tanks is to simply put partially cured driftwood in them!

Of course, there is the strange dichotomy that exists:

In stark contrast to the desperate calls for suggestions of hapless planted tank enthusiasts about when their damn piece of driftwood will stop leaching, I'll literally get emails and pm's from hobbyists who are upset because they can't get their tanks "dark" enough.

That's how far we've come, lol. I'm pretty convinced that we as a hobby are weird.

And that's okay.

Now, a lot of you have asked about the use of commercial "blackwater extracts" and Rooibos tea for these purposes, and if we plan on carrying them.

Short answer: We don't. We won't.

Why?

It's NOT because these are not "cool" or because they "accomplish the same things as the leaves we sell" or whatever...

It's because I feel that they are "shortcuts" which hobbyists tend to use in place of a "system", "approach", or methodology to accomplish the same thing on a continuous basis. As you know, I tend to look at "hacks" or whatever you call them, when used in place of other procedures, as a "band aid" of sorts- used to quickly provide a desired result, without a long-term approach to managing your aquarium ("C'mon, Scott, you just brew another cup of tea...").

Now, as a long-time reef aquarist, I'll tell you that there absolutely is a value to use of appropriate additives and such which, when used in conjunction with an integrated approach, can consistent, give long-term results. And sure, we may offer products which are intended to integrate with our approach and help facilitate results..key word here being "integrate"- not "substitute." You can't just add a "drop of this" or a "pinch of that" to create optimum environmental conditions for your fishes and call it a day.

It's different than say, using an RO/DI unit to pre-treat your tap water obtain optimum "base water" conditions from which you can modify them with natural materials and such. That's an example of a vehicle to help us create the environment we seek on a consistent basis...not a "shortcut" or fix that overlooks the big picture.

That being said, I think that our entire botanical-style aquarium approach needs to be viewed as just that- an approach. A way to use a set of materials, techniques, and concepts to achieve desired results consistently over time. A way that tends to eschew short-term "fixes" in favor of long-term technique. In my opinion, this type of "short-term, instant-result" mindset has made the reef aquarium hobby of late more about adding that extra piece of gear or specialized chemical additive as means to get some quick, short term result than it is a way of taking an approach that embraces learning about the entire ecosystem we are trying to recreate in our tanks and facilitating long-term success.

Yeah, once again- the "problem" with Rooibos or blackwater extracts as I see it is that they encourage a "Hey, my water is getting more clear, time to add another tea bag or a teaspoon of extract..." mindset, instead of fostering a mindset that looks at what the best way to achieve and maintain the desired results naturally on a continuous basis is. A sort of symbolic manifestation of encouraging a short-term fix to a long-term concern.

Again, there is no "right or wrong" in this context- it's just that we need to ask ourselves why we are utilizing these products, and to ask ourselves how they fit into the "big picture" of what we're trying to accomplish. And we shouldn't fool ourselves into believing that you simply add a drop of something- or even throw in some Alder Cones or Catappa leaves- and that will solve all of our problems. Are we fixated on aesthetics, or are we considering the long-term impacts on our closed system environments.

Sure, I can feel cynicism towards my mindset here. I understand that.

However, if we look at the use of extracts and additives, and additional botanicals- for that matter- as part of a holistic approach to achieving continuous and consistent results in our aquariums, that's a different story altogether.

It makes a lot more sense to learn a bit more about how natural materials influence the wild blackwater habitats of the world, and to understand that they are being replenished on a more or less continuous basis, then considering how best to replicate this in our aquariums consistently and safely.

Again, lest you think I'm simply taking this mindset to "sell more of my stuff" instead of seeing hobbyists buy teabags or tonics, let me set you straight one more time: Remember, botanical materials not only add tannins, humic substances, and other valuable organic compounds- they create a "structural" part of the habitat. A place for fishes to hide, spawn, forage. And they encourage the growth of beneficial biofilms, fungal growths, and crustaceans- just like they do in nature. And yeah, they look interesting, too. That whole "functional aesthetic" idea again.

I don't think that a tea bag or an "elixir" can do that on its own.

Stay curious. Stay attentive. Stay open-minded. Stay considerate...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

When the waters return..

If you play with botanicals, it's practically a "given" that you love the idea of tangled masses of roots and driftwood, too. Not simply a few artfully arranged peices, mind you.

No, I'm talking about representations of literal "tangles" of twigs and roots, which tend to accumulate on the forest floor, only to be engulfed by water as the rainy season commences, flooding swollen streams and rivers. It's such an irresistible subject for us, right?

Think about what happens when a tree, or its branches, are submerged in water...

Shortly after submersion, fungi and other microorganisms act to colonize the surfaces, and biofilms populate the bark and exposed surfaces of the branches. Over time, the bark and wood from the branches will impart many chemical substances, (humic acids, tannins, sugars, etc.) into the water, adding to the unique "brew" of life-bearing compounds.

The trees-or their parts- literally bring new life to the waters.

The materials that comprise the tree are known in ecology as "allochthonous material"- something imported into an ecosystem from outside of it. (extra points if you can pronounce the word on the first try...) And of course, in the case of trees, this also includes includes leaves, fruits and seed pods that fall or are washed into the water along with the branches and trunks that topple into the stream.

These materials are known to ecologists as “coarse particulate organic matter”, and in the waters of these inundated forest floors there is a lot of CPOM, and the community of aquatic organisms (typically the aforementioned aquatic insects and crustaceans) has a high proportion of “shredders”, which feed on the CPOM and break it up into tinier bits called (wait for it...) "fine particulate organic matter."

Some of these "shredders" and their larvae are a direct source of food for fishes, providing a nutritious food source for growing populations in these waters.

And of course, some fishes directly consume fallen fruits and seeds themselves as part of their diet as well, aiding in the "refinement" of the CPOM. Think about the Pacu, for example, which has specialized mouthparts suited to crushing hard-shelled fruits and seeds. Other organisms make use of the fine particulate matter by filtering it from the water or accessing it in the sediments that result. These allochthonous materials support a diverse food chain that's almost entirely based on our old friend, detritus!

Yes, detritus. Sworn enemy of the traditional aquarium hobby...misunderstood bearer of life to the aquatic habitat.

And, although the forest floor receives substantially less sunlight than open rivers, the nutrients and available light are utilized by algae, which may colonize the surfaces facing up into the sun. True aquatic plants are essentially non-existent in the flooded forests. Rather, the presence of terrestrial grasses and plants, which can tolerate periods of submersion, are the most common plants here.

And of course, branches, bark, and ultimately, the tree itself, will gradually decompose over long periods of time. Hollowed-out sections will be inhabited by fishes and exploited for the shelter they offer. Other fishes utilize these "microhabitats" as spawning areas, and provide defensible spaces to rear their fry.

And interestingly, when you think about it, fish movement, species "richness," and the size of the fish population are affected by the physical and biological influences of fallen trees! How interesting that the lives of aquatic animals are so inexorably linked to the terrestrial environment!

And the deep beds of leaves and plant parts that may be "corralled" by fallen trees- a sort of natural "dam"- will affect the types of fishes which reside there. Some fish species, which cannot tolerate the lower oxygen concentrations found in these areas of deep leaf litter, will reside elsewhere, allowing a sort of natural "resource partitioning" that lets more tolerant species (such as knifefishes, catfishes, etc.) take advantage of the food sources in these deep beds.

Other fishes take advantage of the physical barrier that a fallen tree presents to shelter from predatory species. Numerous behavioral and even physiological adaptations have taken place over eons to allow fishes to exploit these changes in their environment caused by fallen trees!

It's pretty hardcore stuff.

And it's all part of the reason that I spend so damn much time pleading with you- my fellow fish geeks- to study, admire, and ultimately replicate natural aquatic habitats as much as you do the big aquascaping contest winners' works. In fact, if every hobbyist spent just a little time studying some of these unique natural habitats, I think the hobby would be radically different.

I think that there would also be hobby success on a different level with a variety of fishes that are perhaps considered elusive and challenging to keep. Success based on providing them with the conditions which they evolved to live in over the millennia, not a "forced fit" its what works for us.

More awareness of both the aesthetics and the function of fascinating ecological niches, such as the aforementioned flooded forests, would drive the acceptance and appreciation of Nature as it is- not as we like to "edit" and "sanitize" it.

The result would be greater appreciation for these precious, diverse, and often threatened ecological treasures, and an accompanying "mental shift" which recognizes the true beauty that exists when the waters return to the forest floors.

Until next time...

Stay observant. Stay studious. Stay creative. Stay engaged. Stay...awed...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics