- Continue Shopping

- Your Cart is Empty

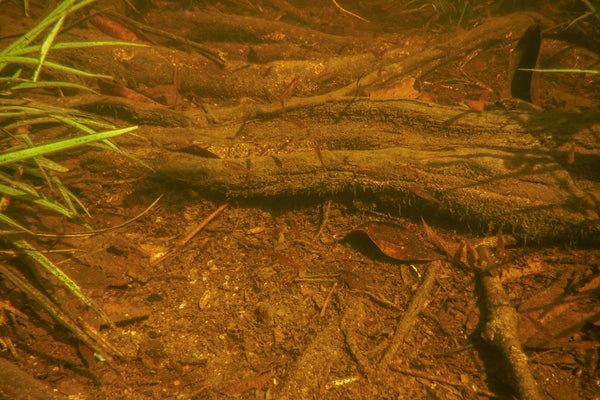

Underwater influences...

II think we can't talk too much about how the physical structures of aquatic habitats influence well- EVERYTHING! I mean, water flows through all sorts of submerged physical structures, ranging from tree trunks to leaf litter assemblages- and that has a huge physiological-chemical influence on the habitat overall as well.

It's very easy to overlook this simple fact in our quest to create cool-looking tanks!

You could take your aquarium design vis-a-vis hardscape further and manipulate water flow patterns and such to allow botanical materials to accumulate in certain areas, or allow stands of certain types of plants to grow in specific locations within the aquarium. Understanding (or at least, observing) how physical barriers, like wood and rocks are oriented by water currents, local geology, and even weather, and also impact the movement of water in a given area, could help you create some interesting scapes.

Lately, it's been all the rage among competitive 'scapers to "break the waterline" with wood. And it's cool. I like it. It has a neat look. Yet, I have to admit, albeit a bit sheepishly- that after seeing several hundred pics of tanks with driftwood heading out of the water (and having done some myself), I can't help but think it's become too much of a "formula": "Assemble group of rare aquascaping rocks, insert manzanita branches in vertical orientation with respect to 'Golden Ratio' and break water line. Done."

Yawn.

Or I Might even say, "vomit"...'cause you know I won't hold back on how I feel about this stuff. How can we save this from becoming another "Scott-hates-the-'social-media- aquascaping-world'-and-sounds-like -an-asshole" rant?

What about approaching this from the standpoint of how and why this would happen in Nature?

I mean, ask yourself under what circumstances would a piece of wood break the waterline? If you study streams and other bodies of water, the reasons are relatively few, but fairly apparent. Likely, one of a few scenarios: 1) A big branch falls into shallow water, with part of it sticking up out of the water. 2) A fallen branch, limb, trunk, or entire tree is covered by water when seasonal inundation submerges the forest floor 3) A tree or shrub growing along an actively-flowing river or stream becomes partially submerged by a large seasonal influx of rain or tidal increase.

It's the same for rocks, and the distribution of substrate materials, botanicals, and leaves. If we ask ourselves how and why these materials accumulate the way they do in nature, the answers create many interesting and inspiring situations for aquascaping. Making the study of natural structures in aquatic habitats part of our inspiration "lookbook" and incorporating them into our "tradecraft" has, IMHO, always yielded more interesting, long term functional aquariums.

In addition to these purely artistic interpretations, (which are beautiful for the most part-I'll give you that) even more amazing, more functionally aesthetic and realistic aquariums can be created by simply looking at what caused these habitats to form in nature, and assembling and placing the components you're using based upon that.

The idea of simulating fallen tree trunks and logs and branches in aquariums is as old as the art of aquarium keeping itself. However, I think the approach of looking at them not just as "set pieces"- but as the foundational cornerstone of a biological and physical habitat gives new context to the practice. Rather than just, "Woah, that peice of wood is a great place for my cichlids to hide!", perhaps we could think about how the wood provides foraging or a corralling feature for leaf litter, soil, etc.

Everything from driftwood to twigs to roots has an important place in simulating the function and look fo the aquatic habitats we love so much. Simply looking at this stuff from a purely aesthetic standpoint sell it short, IMHO.

Combinations of these materials (contained in various ways) could create an interesting functional AND aesthetic terrestrial component that could influence the water chemistry and ecological diversity of our systems.

Asalways, the big opportunity here is not only to create a realistic, compelling display- it's to further unlock some of the secrets of nature and study the interactions between land and water. It's about incorporating function into our displays, and appreciating the aesthetics which accompany it!

Stay inspired. Stay creative. Stay observant. Stay diligent. Stay open-minded...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Active, compelling...changing...

It's certainly no stretch to call our use of botanicals as a form of "active substrate", much like the use of clays, mineral additives, soils, etc. in planted aquariums. Although our emphasis is on creating specific water conditions, fostering the growth of microorganisms and fungi, as well as creating unique aesthetics, versus the "more traditional" substrate materials fostering conditions specifically for plant growth.

And these substrates change over time, in both composition and appearance. What are the implications of this in a botanical-style aquarium?

With the publishing of photos and videos of leave-influenced 'scapes in the past few years, there has been much interest and more questions by hobbyists who have not really considered these items in an aquascape before. This is really cool, because new people with new ideas and approaches are experimenting. And we're looking at nature as never before.

We're celebrating the real diversity and appearance of natural habitats as they really are...

Some hobbyists have commented that, as their leaves and botanicals break down and the scape as initially presented changes significantly over time. They know it or not, they are grasping the Japanese philosophy of "Wabi-Sabi"...sort of. One must appreciate the beauty at various phases to really grasp the concept and appreciate it. To find little vignettes- little moments- of fleeting beauty that need not be permanent to enjoy.

Is the substrate that we create- and which evolves over time as botanicals break down an example of this philosophy?

Absolutely.

Enjoy your aquarium at every phase. Don't like the way it's looking today? No worries, it'll be different tomorrow!

Stay patient. Stay observant. Stay intrigued. Stay curious...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Nature. Undedited.

Traditionally, when you're creating an aquarium, doesn't it seem like you find yourself adding a little of this or a bit of that until you get the right "look?" You spend a lot of time positioning this piece of wood, or bit of rock, or whatever, to get it just right.

And it's a process that involves pleasing our aesthetic "palette", so to speak. And that is an important part of the creative process.

We "edit."

Equally important, when we are talking about creating natural-looking and functioning aquariums, is to make that "mental leap" and remind ourselves constantly that Nature is simply not really a spotless, geometrically organized place.

I'm not implying that Nature is "dirty" in the sense that it's polluted...although sadly, in some parts of the world, it most definitely is. Rather, in the context of this piece, we're referring to the term "dirty" as an aesthetic descriptor of the earthy, brown, seemingly disorganized place that Nature actually is.

Even though it sounds rather harsh, I cringe when I see the words "Natural" or "Nature" used to describe an aquarium that is a spotless, "diorama-esque" art piece, with bears as much resemblance of the natural habitats of our fishes as a potted plant does to a tropical jungle.

We need to be comfortable simply calling them what they are: Aquascaped aquariums. There is absolutely nothing wrong with that term. These aquariums are often breathtaking; executed with style and grace by talented hobbyists worldwide. They incorporate some natural materials, like plants, rocks, and wood- yet they are presented in such a way as to essentially "cleanse" most of what some would see as "aesthetically unacceptable" parts of Nature.

If there's one thing that I'd like our work here at Tannin Aquatics to elevate, it's the unfiltered beauty of Nature. An appreciation for the way Nature is- not the way our preconceived aesthetic notions want it to be.

Nature, unedited.

And that is something that we understand is not appealing to everyone. And sort of "sticking it in everyone's face" and suggesting that a truly "natural" aquarium requires the acceptance of a very polarizing aesthetic certainly can turn off some people.

I do get it.

However, I see little downside to studying Nature as it is.

It's very important, IMHO, to at least have a cursory understanding of how these habitats have come to be; what function they perform for the piscine inhabitants who reside there, and why they look the way they do. Even if you simply despise the types of aquariums we love here!

Why?

Because in the process of learning about Nature as it is, and the uniqueness and fragility of the habitats we love, we become more attuned to the way aquatic ecosystems function, and the threats these wild systems face. And when we have a greater understanding of the habitats themselves, we have a greater understanding of how to replicate their form and function in the aquarium.

Simply copying exactly every beautiful aquarium you see here, or elsewhere online deprives us of the amazing opportunity to study and be inspired by the wonders of Nature as it is.

Nature. Unedited.

A confluence of terrestrial and aquatic elements, working together to create a unique and inspiring habitat. By selecting to replicate, at least on some level, an "unedited" interpretation of these habitats, we open up new aesthetic possibilities, foster breakthroughs in aquatic husbandry, and further the state of the art of the aquarium hobby.

Stay curious. Stay observant. Stay excited. Stay inspired...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

(Amazing pics for this piece were furnished by Thomas Minessi, Tai Strietman, Cory Hopkins, and Johnny Ciotti)

In the clear...or the "turbid", or...

For most of my life as an aquarist, I've read dozens and dozens of articles about the idea of keeping your aquarium water "crystal clear."

Now, I certainly won't disagree that clear water is nice.

I like it, too...However, I would make the case that "crystal clear" water is: a) not always solely indicative of "healthy" or "optimum" , and b) not always what fishes encounter in nature.

Of course, in the aquarium, "cloudy" water is often seen as indicative of some sort of trouble- typically, bacterial blooms, algal blooms, incompletely washed substrate, etc, so we correctly make the initial assessment that something might be amiss when water suddenly becomes cloudy or 'murky", or just shows turbidity.

On the other hand, "turbidity", as it's typically defined, leaves open the possibility that it's not necessarily a negative thing:

"...the cloudiness or haziness of a fluid caused by large numbers of individual particles that are generally invisible to the naked eye, similar to smoke in air..."

What am I getting at?

Well, think for a second about a body of water like the Rio Negro. This water is of course, "tinted" because of the dissolved tannins and humic substances that are present due to decaying botanical materials. We know all about that, right?

Yet, that's quite a bit different from being cloudy or turbid, however.

And, of course, there might be some turbidity because of the runoff of soils from the surrounding forests, incompletely decomposed leaves, current, rain, etc. etc. All are "by-products" of the surrounding environment.

And really, none of the possible causes of turbidity mentioned above in these natural watercourses represent a threat to the "quality", per se. Rather, they are the visual sign of an influx of dissolved materials that contribute to what I call the "richness" of the environment.

It's what's "normal" for this habitat.

A habitat that is influenced by the surrounding terrestrial environment.

Obviously, in the closed environment that is an aquarium, "stuff" dissolving into the water may have significant impact on the overall quality. Even though it may be "normal" in a blackwater environment to have all of those dissolved leaves and botanicals, this could be problematic in the aquarium if nitrate, phosphate, and other DOC's contribute to a higher bioload, bacteria count, etc. than we are equipped to export.

Again, though, I think we need to contemplate the difference between water "quality" as expressed by the measure of compounds like nitrate and phosphate, and visual clarity.

Our aesthetic "upbringing" in the hobby seems to push us towards "crystal clear water", regardless of whether or not it's "tinted" or not. And think about it: You can have absolutely horrifically toxic levels of ammonia, dissolved heavy metals, etc. in water that is "invisible", and have perfectly beautiful parameters in water that is heavily tinted and even a bit turbid!

That's why the aquarium "mythology" which suggested that blackwater tanks were somehow "dirtier" than "blue water" tanks drives me crazy.

Color alone is not indicative of water quality for aquarium purposes, nor is "turbidity." Sure, by municipal drinking water standards, color and clarity are important, and can indicate a number of potential issues...But we're not talking about drinking water here, are we?

I've seen plenty of botanical-influenced blackwater aquariums which have a visual "thickness" to them-you know, a sort of look- with small amounts of particulate present in the water column- yet still have spot-on water conditions from a chemical perspective, with undetectable nitrate, phosphate, and of course, no ammonia or nitrite present.

It's important, when passing judgement on, or evaluating the concept of botanicals in aquariums, to remember this. Sure, crystal clear water is absolutely desirable for 98% of all aquariums out there- but not always "realistic", in terms of how closely the tank replicates the natural environment.

And of course, by the same token, a healthy botanical- influenced tank may typically not be turbid, but that doesn't mean that it's not "functioning properly." Again, this realization and willingness to understand and embrace the aesthetic for what it is becomes a large part of that "mental shift" that we talk about so often here on these pages.

And the beauty of an aquarium is that you can either remove or contribute to the color and clarity characteristics of your water if you don't like 'em, by simply utilizing technique- ie; mechanical and chemical filtration, water changes, etc.

It's that simple.

And it's all our choice.

Stay diligent. Stay observant. Stay curious. Stay open-minded. Stay creative...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

The "lemonade theory..."

As your botanical aquarium breaks in, you almost always encounter our friend (or nemesis, depending upon how you look at it), biofilm. Now, we've discussed the ins and outs of biofilms in our botanical-style aquariums, and how they arise and propagate in our tanks many times in this blog.

To many, the biofilms are a source of consternation, frustration, and out-and-out horror. They look kind of- well, yucky to many. Although by no means harmful, they're simply not everyone's idea of high-quality aesthetics. Of course, biofilms have one extraordinary characteristic that makes them even more important for some in our community: They're a rich and important food source for many fishes and invertebrates.

This is one of the most interesting aspects of a botanical-style aquarium: We have the opportunity to create an aquatic microcosm which provides not only unique aesthetics- it provides self-generating nutritional value on a more-or-less continuous basis. True "functional aesthetics", indeed!

I feel a great affinity for my friends who keep dwarf shrimp, like Caridina, Halocaridina, etc. These hobbyists understand and appreciate the value of botanicals and the biofilms which colonize them as a food source, and put forth a lot of effort to propagate them in their aquariums.

Some fishes, such as gobies of the genus Stiphodon (Sicydiines) are near-exclusive consumers of biofilms in the wild. Most reside in relatively fast-flowing, well-oxygenated streams which are filled with scattered jumbles of boulders and rocks, filled in with leaf litter. The boulders and rocks are covered in biofilms of various densities and composition.

Granted, the bulk of the biofilms in these habitats is on rocks, but the leaf litter which accumulates in pockets in the habitat is also a substrate upon which they propagate. And in many aquatic habitats, submerged branches and logs and such also recruit these biofilms.

And biofilms are interesting, in and of themselves. Understanding the reasons they arise and how they propagate can really help us to appreciate them!

It starts with a few bacteria, taking advantage of the abundant and comfy surface area that leaves, seed pods, and even driftwood offer. The "early adapters" put out the "welcome mat" for other bacteria by providing more diverse adhesion sites, such as a matrix of sugars that holds the biofilm together. Since some bacteria species are incapable of attaching to a surface on their own, they often anchor themselves to the matrix or directly to their friends who arrived at the party first.

And we could go on and on all day telling you that this is a completely natural occurrence; bacteria and other microorganisms taking advantage of a perfect substrate upon which to grow and reproduce, just like in the wild. Freshly added botanicals offer a "mother load"of organic material for these biofilms to propagate, and that's occasionally what happens - just like in nature.

And biofilms seem to go hand-in-hand with fungi.

Fungi reproduce by releasing tiny spores that then germinate on new and hospitable surfaces (ie, pretty muchanywhere they damn well please!). These aquatic fungi are involved in the decay of wood and leafy material. And of course, when you submerge terrestrial materials in water, growths of fungi tend to arise. Anyone who's ever "cured" a piece of aquatic wood for your aquarium can attest to this!

Fungi tend to colonize wood because it offers them a lot of surface area to thrive and live out their life cycle. And cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, the major components of wood and botanical materials, are degraded by fungi which posses enzymes that can digest these materials! Fungi are regarded by biologists to be the dominant organisms associated with decaying leaves in streams, so this gives you some idea as to why we see them in our aquariums, right?

And of course, fishes and invertebrates which live amongst and feed directly upon the fungi and decomposing leaves and botanicals contribute to the breakdown of these materials as well! Aquatic fungi can break down the leaf matrix and make the energy available to feeding animals in these habitats. And look at this little gem I found in my research:

"There is evidence that detritivores selectively feed on conditioned leaves, i.e. those previously colonized by fungi (Suberkropp, 1992; Graca, 1993). Fungi can alter the food quality and palatability of leaf detritus, aecting shredder growth rates. Animals that feed on a diet rich in fungi have higher growth rates and fecundity than those fed on poorly colonized leaves. Some shredders prefer to feed on leaves that are colonized by fungi, whereas others consume fungal mycelium selectively..."

"Conditioned" leaves, in this context, are those which have been previously colonized by fungi! They make the energy within the leaves and botanicals more available to higher organisms like fishes and invertebrates!

It's easy to get scared by this stuff...and surprisingly, it's even easier to exploit it as a food source for your animals!

We just have to make that mental shift... As the expression goes, "when life gives you lemons, make lemonade!"

Stay the course. Don't be afraid. Open your mind. Study what is happening. Draw parallels to the natural aquatic ecosystems of the world. Look at this "evolution" process with wonder, awe, and courage. And know that the pile of decomposing goo that you're looking at now is just a steppingstone on the journey to an aquarium which embrace nature in every conceivable way.

Stay calm. Stay curious. Stay bold. Stay resourceful...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Can it wait?

There are things in this hobby which we never really understand, but that predictably drive us crazy. And there are those things that arise, which we have to handle, that annoy, disturb- even scare us.

Examples?

The motor in your canister filter is making that familiar chattering sound- you know, the one that means the impeller needs to be taken out and cleaned. And of course, that means shutting it down, removing it, cleaning it, reinstalling it, and getting it primed again. You sort of located it in the part of the aquarium stand that's hardest to access...And you remember from the last time what a pain in the ass it was to do this...

Can it wait a bit longer? Is the chattering noise that bad?

I mean, you're not loosing any circulation or anything...it's just that the sound is a bit...annoying...and...

Some stuff that you need to face with your tank is more than just a pain in the rear- it's the kind of thing that disrupts the entire fish population until it's completed. That overgrown stand of Cryptocoryne wendtii really needs to be thinned out before it takes over the whole right rear of your tank!

And it's badly encroaching on that rare Red Crypt from Borneo. And of course, it's growing behind that insanely cool stack of driftwood that you finally got to hold position after 2 hours of frustrating effort, and the 'scape has been just perfect ever since that day! Thinning out this group of plants will not only risk the wood stack tumbling down, it'll just be a disruptive mess that will no doubt aggravate all of the fishes, including that skittish pair of Betta coccina that are finally starting to come out after weeks of timid appearances.

Can it wait a bit longer? Does the plant grouping really need to be thinned out now?

The aquascape really doesn't look that bad, right? And that rare red Crypt; is it REALLY that cool? I Mean, it WAS pricy, but...

Sometimes, it's about doing stuff that's simply annoying. Maybe it's messy. It's always disruptive, to some extent...And occasionally, it's about decisions which affect the harmony of the tank.

And then, there are those other times...the so-called "911" moments. The ones that result from rolling the dice and making a decision that could have went either really good or really bad...and it went really bad this time. The need to act is pretty much a given...Adding that extra male Ram to the small group you had in play created a big blowup in the social order; this new guy is being chased all over the tank by the dominant fish.

All of the other fishes are sort of freaked out by the aggressiveness, hiding or acting weird; this calculation was wrong on this occasion, and the consequences threaten the life of the new fish, and the overall harmony of the tank. It's obvious that the new guy needs to come out- and fast. And of course, this the beautifully planted, intricately-scape tank that you've been sharing all over Instagram, and moving the wood and those rocks to get the one beleaguered Ram out is going to pretty much destroy the scape. Oh, and did I mention, he looks like all of the stress may have caused him to contract some sort of disease...Why is he scratching?

And this time, the "can it wait?" calculus is not really in play. Nature- and the fishes- have made the decision easy for you..Well, "easy" is relative, of course. More like-binary. The consequences of waiting- on this occasion- are pretty obvious. Leaving this fish in means he dies, and possibly spreads disease to the rest of the inhabitants. Those "micro-calculations" you occasionally make about "...the needs of the many being more important than the needs of the few or the one..." (to borrow a famous Star Trek phrase) are of now out of the question.

Time to "rip off the Band Aid" and act.

It can't wait.

The most humbling, if not educational hobby moments often come from the simple set of decisions that we have to make- decisions that were set in motion by other decisions, perhaps weeks or months before. Yet decisions which have both short and long-term implications for your aquarium.

And always, hopefully- you learn and grow as a result of both the experience and the decision.

As the old expression goes, “Good decisions come from experience, and experience comes from bad decisions.”

That pretty much sums it up, right?

Besides, that chattering noise the pump is making really IS annoying, huh?

Stay decisive. Stay observant. Stay diligent. Stay grounded...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

The philosophy...

I know that I seem to spend an inordinate amount of time dwelling on obscure and arcane topics in the aquarium hobby- I mean, someone has to, right?

We try to do lots of interesting little projects here at Tannin which not only are fun, but help us work through the basic philosophies that we operate by. Stuff like trying out different ideas and either "crashing and burning" or succeeding wildly, right in front of you guys- no "safety net" required. It's foundational. We have to push ourselves to do things a bit differently than we have done before- in both theory and practice. It's what drives us as hobbyists, and Tannin as a company, to "move the needle", if ever so slightly, of the hobby's state of the art.

It seems like no tank that I've presented in the last year or so has generated so much "buzz" in our community as the one that I created for my Tucano Tetras. I mean, I felt it, too. Something about this tank- this idea- that is clicking. Not exactly sure what exactly it is about this one, but I've received so many emails, DM's, and questions about it that it made me reflect even more about the simple philosophy which guides everything we do here. I'm thinking it's at least in part because it absolutely reflects our philosophy in a tangible way.

I think that it's important to look at the work that we do as hobbyists- specifically, the tanks we create- as little "microcosms" that are essentially our fishes' entire universe. That's not too much of a stretch, but it's a really important "cornerstone philosophy"- one that separates the "natural style" aquarium enthusiast from say, the pure aesthetic aquascaper, breeder, or casual fish keeper.

Even at the hobby's most "basic" levels, you as the aquarist create the physical environment for your fishes, and are more or less in control of every facet of its existence. You control the appearance, environmental parameters, population, input and export of nutrients- like, everything. And the health and lives of each and every organism which resides in the aquarium are completely in your hands.

Like, 100%.

Kind of an awesome responsibility, when you think about it that way, huh?

It is.

And, while our fishes go about their daily existence likely not comprehending all of that, and likely behaving in your aquarium in much the manner that their wild ancestors have for untold millions of years, what they DO know is that this is their world. The physical structures you've created, the water parameters, the competing population of fishes, availability of food resources, and the quality of the water are just a few of the things they contend with like they would if they were swimming about in the wild.

I mean, that's our hope, anyways...right?

This is one of the reasons why I have had a near-obsession with attempting to recreate, to some extent, as many of the physical/environmental characteristics of their wild habitats as possible for the fishes under my care. All the while, realizing that, although they will be residing in a closed system with many physio-chemical characteristics similar to what they have evolved to live under, it's not a perfect replication, much though I might want it to be, and being of the opinion that replicating "some"of these characteristics is likely better than replicating "none" of them. I have no illusions about this- and there is a far cry between recreate the "look" and mimicking the function of the habitat.

An arrogant assumption on my part, I suppose. I mean, like every one of you, I'm fully responsible for the animals which I keep, and I take a certain degree of pride in that. I want the best for them.

That being said, I'm personally not in that mindset of having to be absolutely "hardcore" about being 100% accurate biotopically, in terms of making sure that every leaf, every twig, every botanical is from the specific habitat of the fishes which I keep. I do respect aquarists who do, however. But that's not me. Rather, I place the emphasis on providing a reasonably realistic representation of the habitat form which they come, with aquascaping materials, layout, and environmental parameters as close as possible to the parameters in the wild.

You can be a very responsible owner, pushing the state of the art of the hobby forward, without obsessing over making every micro-semion of conductivity, or every ppm of phosphate in your tank match that of your fishes' wild habitat. I'm pretty confident about that.

Your fishes likely don't know that, having been captive-bred for a few generations, or collected from their natural habitat and being subjected to varying environmental differences along the chain of custody from stream to store. The likely don't even care. They're likely just happy to be somewhere stable by the time they arrive in your home aquarium!

Our fishes being genetically "programmed" by evolution to live under certain environmental parameters for millennia can't likely be replaced by a few dozen generations of captive breeding. You know, just substitute a line or two of "code", and presto! However, being able to acclimate and thrive-even reproduce- in conditions significantly different from what they evolved under does indicate some good adaptability on the part of our fishes, doesn't it?

And as an aquarist, we benefit from this, even though our hearts may tell us it would be a cool idea to try to be 100% faithful to nature in this regard, despite the difficulties involved.

Of course, all the while being fully aware that, for example, achieving and managing a 4.3 pH similar to the floating leaf littler banks of the Aliança Stream (a tributary of Branco River in Brazil), for example, is beyond the level of detail that I want to go into! It would be very cool to do, but it's just not what I'd want to do at the moment.

I suppose my attitude towards those factors would "disqualify" me personally from being a very hardcore biotope aquarist- at least one who would try to compete in a contest!

The Tucano Tetras I keep, of course, don't know this.

Nor do they seem to care.

None of the fishes I keep do.

Rather, they're preoccupied with finding their next meal, socialization, and other more mundane aspects of their daily existence. As long as they are physically comfortable and free from high levels of stress as a result of evading predators and exploiting very limited food resources, I don't think one could make an argument that they do care...

And just because you're content with your aquariums being "biotope-inspired" as opposed to 100% faithful to replicating the aesthetics or physical characteristics of the natural habitat you're into doesn't mean you don't care, aren't doing a good job, or aren't dedicated to your craft.

What every fish under your care does know is that they are living in a stable, stress-limited environment that they can easily adapt to and live out their lives in.

And that's worth considering the next time you set up an aquarium, isn't it?

I think so.

Stay curious. Stay open-minded. Stay observant. Stay enthusiastic. Stay creative...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

The stuff we're afraid of...And a plea for honesty, patience, and humility. A rant.

All of you who know me personally know that I'm about as geeky and traditionally-raised aquarist as they come. I was brought up in a world of fancy guppies, killifishes, and Neon Tetras. I had my first legit aquarium when I was about 5 years old...after having maintained goldfish bowls since I was around 3. Aquarium keeping was in my blood, just as it was in my father's before me.

I've been fortunate enough to have grown as a hobbyist, tried all sorts of different stuff; travelled the world studying aquariums, speaking, and starting and managing two successful companies in the aquatics space. It's been a good ride so far!

Yet, like many of you, for a long time, I harbored some fears about stuff in the hobby. Yeah, I was afraid for a long time to walk outside of the well-trodden path worn by our hobby forefathers. I tried all sorts of fishes and aquariums, but seldom, if ever, deviated from what would be seen as decidedly mainstream. To do so not only meant facing the scorn of the hobby community, it meant potentially failing or doing something that had no pre-conceived rules or guidelines...

And that can be scary.

About 15 years ago, I simply decided never to be scared again in the hobby. I started experimenting with all of those ideas and approaches that were in my head for so many years...And most important, I decided that I couldn't give two &*^*&%^^%$ about what anyone thought about the stuff I tried.

It's been really healthy. And very quiet in my head...

Although on some days, I want to yell...

Unfortunately for you guys, today is such a day.

We have a lot of fears that we may not want to admit to, IMHO.

One of the things that drives me crazy is this innate fear of "detritus", "dirt", and "decomposition" that seems to have been beaten into the head of every hobbyist since time immemorial...A fear; a warning that tells the hobbyist that anything decomposing in the aquarium will degrade water quality, unleash horrific algal blooms, and kill your fishes...

The admonition for decades has been to siphon up every gram of detritus each time we change the water in our aquariums. The prevailing thought in the hobby is that this stuff is only bad news:

"detritus is dead particulate organic matter. It typically includes the bodies or fragments of dead organisms, as well as fecal material. Detritus is typically colonized by communities of microorganisms which act to decompose or remineralize the material." (Source: The Aquarium Wiki)

Woah!

It's one of our most commonly used aquarium terms...and one which, well, quite frankly, sends shivers down the spine of many aquarium hobbyists. And judging from that definition, it sounds like something you absolutely want to avoid having in your system at all costs. I mean, "dead organisms" and "fecal material" is not everyone's idea of a good time, ya know?

Yet, when you really think about it, "detritus" is an important part of the aquatic ecosystem, providing "fuel" for microorganisms and fungi at the base of the food chain in tropical streams. In fact, in natural blackwater systems, the food inputs into the water are channeled by decomposers, like fungi, which act upon leaves and other organic materials in the water to break them down.

Now, sure- the stuff just doesn't look that nice to most of us, and that's partially why the recommendation for a good part of the century or so we've kept aquariums is to siphon it the hell out! And that's good advice from an aesthetic standpoint- and for that matter, from a husbandry standpoint, as well. Excessive amounts of accumulating waste materials can lead to increased phosphate, nitrate, and other problems, including blooms of nuisance algae. Emphasis on the word "excessive" here...(which begs the question, "What is "excessive" in this context, anyways?)

However, with the importance of detritus in creating food webs in wild leaf litter communities, which we are now replicating in aquariums, could there actually be some benefit to allowing a little of this stuff to accumulate? Or at least, not "freaking out" and removing every single microgram of detritus as soon as it appears?

I think so. Really.

Is this another one of those long-held "aquarium truisms" that, for 90% of what we do is absolutely the correct way to manage our tanks, but which, for a small percentage of aquarists with the means, curiosity and inclination to experiment, could actually prove detrimental in some way?

I think so.

Another thing that absolutely drives me crazy, and goes hand-in-hand with the fear of detritus and decomposition is a stunning lack of patience that I have seen in the hobby for years now.

We're afraid to wait. TO let things happen. To evolve. We want it done...NOW.

I am going to beat that impatience out of you if it's the last thing we do here. And

I'm going to call us all out:

I absolutely, 100% blame this on the "hardcore aquascaping world" who feature these instant "masterpiece scapes" and make little to no mention whatsoever about the time required for an aquarium to cycle, to process nutrients. To go through not-so-attractive phases. For plants to establish and grow. To go through the phases where things aren't established. THE TIME. It takes weeks or months to get a tank truly "established", regardless of what approach we take, or what type of tank we're setting up.

Don't be afraid. And yes, not everyone hides the process.

Only about 95% of us.

What we've done collectively by only illustrating the perfectly manicured "finished product "is give our brothers and sisters the impression that all you do is choose some rock, wood, and plants or whatever , do some high concept scape, and Bam! Instant masterpiece. Yes, there are PLENTY of people who actually think that...WHY are we so f- ing scared to show an empty tank, one with the "not-so-finished" hardscape or plant arrangement? The period of time when the wood may not be covered in moss, or when the rock has a film of algae on it? One that has perhaps an algae bloom, a bunch of wood that needs to be rearranged, etc.

That's reality. That is what fellow hobbyists need to see. It's important for us to share the progress- the process- of establishing a beautiful tank- with all of its ugliness along the way.

This does severe long-term damage to the "culture" of our hobby. It's sends a dumbed-down message that a perfect tank is the only acceptable kind.

I freaking HATE that.

Stop being so goddam afraid of showing stuff when it's not "perfect." You don't need anyone's approval. Period.

To all of us...an appeal: PLEASE STOP doing this.

At least, without taking some time to describe and share the process and explain the passage of time required to really arrive at one of these great works. Share the pics of your tank evolving through its early, "honest" phases. That's the magic...the amazing, inspiring, aspirational part EVERY bit as much as the finished contest entry pic.

Wanna help the hobby? Do that.

Patience. The passage of time. Allowing Nature to do her work...These are things that we as humans seem so afraid to let happen. We seem to feel that the time required to establish a truly healthy, beautiful tank naturally is somehow "wasted" or uninteresting. As if it's devoid of value until the tank is "ready for Instagram" or whatever. We're afraid to share anything that's not perfect.

Nothing could be further from the truth. That's the whole game! The beauty of watching a tank evolve- at whatever speed it does- from a disorganized "mess" to a beautiful microcosm of life in all its forms- is a gift from the Universe.

The types of aquariums we do in our little niche absolutely should be documented in all of their phases. The turbid water, the tint. The biofilms. The "patina" of growth on wood...All of these are beautiful things that change over time, and need to be shared so that the world understands exactly how these tanks come into being.

Successes , challenges, and indeed, our failures should be shared...so we can all learn, and understand that Nature is as much a "process" as it is a "thing." And that there is beauty everywhere if we shift our minds to accept it.

Yes. Tannin will organize a contest one day soon. And yes, it will have lots of pretty inspiring tanks. But HELL YES- all entrants will be required to show the raw, unfinished beauty of the evolution of the display as part of the deal. The goal is to show that an aquarium, like Nature itself, is a dynamic, constantly evolving system. Things like algal films, biofilms, decomposing botanicals, pockets of sediment and detritus are every bit as compelling, beautiful, and awe-inspiring to look at as any ultra-manicured "finished" show tank.

Nature unedited.

Patience. A lack of it will simply wreck your hobby experience.

FACT: If you add all of the contents of your "Enigma Pack" to an established aquarium that has been stable for some time, you will likely kill everything in your tank. Think about the logic here. You can't add a shitload of biological material to any established system and expect there to be no impact on the aquarium environment. The bacterial population as to adjust to the new influx of materials.

And guess what? That takes time. And time is really boring to a lot of people. The very, very few emails I receive from people who wipe out their aquariums after adding botanicals are almost always caused by human error. Adding too much too fast. Not preparing materials. Not thinking.

DON'T BE AFRAID TO BE PATIENT.

Yeah, you may stare at an aquarium full of pods, leaf litter, mud, and detritus for a few weeks or more before it's safe to add fishes. Or, you may add your botanicals just a few at a time over the course of weeks.

Oh well. It takes time. Enjoy the slow process. Enjoy your aquarium at every phase.

Along the way, you'll gain a tremendous appreciation for how Nature works. And a sense of patience, pride, humidly...And ultimately, the realization that an aquarium is never truly "finished."

It's a journey. Frought with peril if we make it that way. Filled with wonder, beauty, and amazement if we accept it.

A journey that we can't be afraid to take.

Until next time...

Stay bold. Stay observant. Stay methodical. Stay patient...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Microcosms, representations, functionality, and education...Positive mental shifts from the "botanical revolution..."

It's kind of neat to hear from many of you in our community discussing your aquariums in terms of "microcosms" of life. This is something that, while not exactly "new,' is gaining greater prominence. Making that mindset shift back towards that old aquarium hobby adage that an aquarium is essentially little closed ecosystem, subject to the influences of Nature on a small scale.

An acceptance of both the function and appearance of Nature is, surprisingly, a big leap for many hobbyists to make. This is profoundly different than the more popular point of view that a "natural" aquarium is a highly contrived, aesthetics-first elegantly aquascaped aquarium dominated by aquatic plants. A realization that there is more to the concept of a functional aquarium than just plants. Other natural materials are equally important.

And of course, the idea of aquariums inspired by, or representing Nature doesn't mean that every single plant, twig, rock, etc. found in a given habitat you're recreating must be included in order to complete your aquarium. That type of ultra-hardcore authenticity is the realm of the serious biotope aquarium enthusiasts- the guys who enter those contests where they model very specific biotope. You know, like the ones that they name: "Shallow stream off of the Tano River, 3 km north of Sunyani, Ghana." Stuff like that.

Nothing wrong with that, of course. However, I can't help but laugh at the criticisms levied by contest judges against biotope aquariums in these contests because they're using "the wrong grade of sand" or whatever, to properly represent that environment, when the substrate is clearly dominated by European Beech leaves or Alder Cones from North America, or whatever. It's just a bit...well, amusing to me.

I'm personally more interested in the overall "look" and atmosphere (and "functionality") of the habitat from an aquarium perspective, and that's what we've built Tannin around. I realize that there are specialized habitats where the "authentic" materials, like rocks or substrates, can make a difference in the function (like African Rift Lakes, Peat Swamps, Soda Lakes, etc.), but for the bulk of our replications, I think that having materials which represent those found in the habitats we're interested is a more than adequate approach.

Key word here being "represent"- and perhaps more thoughtfully or faithfully than we've done in the past, with as much emphasis on function as on the aesthetics.

Many of the items we use in aquairums, for example, Catappa leaves, may not be found in the specific habitat we're trying to replicate, but they effectively represent the leaves found in the streams and rivers we're interested in modeling our aquariums after. (The irony is that the Indian Almond tree has been transplanted to tropical regions worldwide, for better or for worse-so it actually may end up being more "biotopically correct" than you might think in some areas!)

Replication versus Representation...

One of the things we enjoy most here at Tannin is offering materials that help you recreate your own representations of all sorts of aquatic habitats. We have worked hard to source materials which help you create some cool looks and some of the "functionality' of wild aquatic habitats. I know that many of you have asked for leaves and pods and such from specific regions, and we hear you. We've been on that for a few years now; never as easy as it seems to be!

We're working our global suppliers constantly to find "real deal" materials from various tropical regions of the world, consistent with sustainability, economic viability for our suppliers, and import regulations. It's a slow process, fraught with challenges, but kind of fun! Some items are heavily regulated for export by their native countries, and getting them out is next to impossible (as it should be!). There may be ecological impacts from removing some of these materials from the natural environment, even though they are "fallen and dead"-and we must respect that.

Many times, we've had to get creative.

In the case of Estuary, for example, some the items we sourced were recommendations from aquatic biologists who specialize in brackish water ecology. They gave me some tips about what (more readily available) materials would serve as suitable representations of some of the things found in these habitats, because, once again, they are typically not available in any type of quantity or frequency.

Sometimes, however, unexpected circumstances led to us getting exactly what we wanted! In at least a couple of cases (stories to follow at a later time), we were told by government officials that we were actually doing them and the local environment a favor taking some of these items out of their territory, as they were invasive in nature and they didn't want them there! Talk about a "win-win" situation!

And when you think about it, even the most ardent biotope fanatics "push it" just a bit. I mean, how do you know 100% that the rock or wood that you're using is actually from that specific river proximate to Yasuni National Park in Peru? Can you even obtain it from there? Likely not. Do the judges of these contests really know that? Probably. Isn't there some leeway in judging this based on the understanding that some of this stuff simply isn't available (you can't collect from a national park, right?), and that "facsimile" materials have to be used?

I think so.

I think all of these people get it.

However, to the hardcore hobbyists who ply their trade in the world of 99.999% authenticity- you people amaze me. As someone who is dedicating his life and business to helping offer materials for hobbyists to replicate the natural environment, you have my complete respect. If you get excited because you actually found a twig from, say, the Apoquitaua River in Brazil- much RESPECT! I get you.

I think the fact that we're seeing more and more hobbyists making efforts to learn about the natural habitats of our fishes on a "macro" level is amazing. A real game changer, IMHO. Understanding the surrounding environment of the aquatic habitats that we want to replicate is hugely important, not only to our knowledge base as aquarists, but to understand the uniqueness of these habitats and the urgent need to protect and preserve them.

With more and more attention being paid the overall environments from which our fishes come-not just the water, but the surrounding areas of the habitat, we as hobbyists will be able to call even more attention to the need to learn about and protect them when we create aquariums based on more specific habitats.

The old adage about "we protect what we love" is definitely true here!

Creativity, energy, and ingenuity are all necessary "equipment" for the lover of biotope-style (notice I said "style?") aquariums. It's a fascinating, lifelong pursuit, and the rewards of educating others, learning for ourselves, and sharing what we know are amazingly satisfying.

And, if somewhere along the way, we end up breeding a few fishes, developing some new techniques, and "moving the needle" of aquarium keeping forward just a bit, it doesn't get any better than that!

Until next time...

Stay excited. Stay enthusiastic. Stay fascinated. Stay inspired. Stay diligent...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

The land of the Tucanos: A case study of a good, but not perfect philosophy

One of the best things about writing your own blog every day is that you develop- well, for want of a better word- fans. And fans not only consume your content; they analyze it, discuss it, criticize it, and request more of it!

One of the many questions I received lately was about how my philosophy of creating a tank works. Now, at first, I had to laugh a bit...I was like, "Umm, you buy a tank, fill it with water, and..." Of course, that WASN'T the gist of the question. What the questioner really wanted to know was how I decide what to include and how to configure my aquariums; what guides these decisions.

It's a pretty good question!

The summarized answer? It's all about the habitat.

Now, I don't profess to be some sort of "guru" on the philosophy of aquarium design and such. However, I do have some definite opinions about what drives my designs.

First off, I am a keen observer and student of wild aquatic habitats and ecological niches in the tropical world. I have found that I am drawn to certain types of habitats; typically, those in which terrestrial materials, like soil, leaves, seed pods, and the like influence the ecological characteristics of the water, and the fishes which live there.

That being said, I will not only observe the aesthetics of the habitat which I want to replicate- I spend a ridiculous amount of time trying to replicate, as faithfully as possible, the function of the habitat as well. The whole tagline for Tannin, "Leaves. Wood. Water. Life" sums up beautifully my mindset: That the aquatic environment strongly influences the health and sustainability of the fishes I keep, and that it's as important to curate and utilize natural materials in such a way as to mimic the habitat as it is to select great specimens.

I have long believed that, despite the fact that many fishes, like Discus, Tetras, etc. are kept and bred successfully in hard, alkaline "tap water" conditions- and have been for generations in the hobby/industry- there is almost always something to be gained by "repatriating" our fishes to conditions that are similar to those which they have evolved to live in for eons.

I just don't believe that a few dozen generations of captive breeding under dramatically different environmental conditions (ie; hard and alkaline water) than their wild environments have eclipsed or erased the evolutionary adaptations to specific conditions. I mean, sure, just because fishes are adaptable to radically different environmental parameters than they evolved to thrive under doesn't meant that it's "better" for them.

I think we can and should do things a bit differently.

We have to draw a distinction between what's best for the fishes and what's easiest for us as hobbyists to create and maintain. And arguably, if we don't bother to study, understand, and appreciate the wild aquatic habitats from which our fishes hail, how can we understand their fragility and the dramatic impacts of humans on them? Your fishes may "come from a hatchery"... But that's not where fishes come from. Make sense?

I think so.

So, to summarize- my philosophy is to study and understand the environments from which our fishes come, and to replicate them in function and form as best as possible. It doesn't always mean exactly- but it's definitely NOT forcing them to adapt to our "local tap water "conditions without any attempt to modify them.

I have a very current "case study" of my own that sort of reflects the execution of my philosophy.

As many of you know, I've had a long obsession with the idea of root tangles and submerged accumulations of leaves, branches, and seed pods. I love the silty, sedimented substrates and the intricate interplay of terrestrial plant roots with the aquatic environment.

I was doing a geeky "deep dive" into this type of habitat in Amazonia, and stumbled upon this gem from a scientific paper by J. Gery and U. Romer in 1997:

"The brook, 80-200cm wide, 50-100 cm deep near the end of the dry season (the level was still dropping at the rate of 20cm a day), runs rather swiftly in a dense forest, with Ficus trees and Leopoldina palms...in the water as dominant plants. Dead wood. mostly prickly trunks of palms, are lying in the water, usually covered with Ficus leaves, which also cover the bottom with a layer 50-100cm thick. No submerse plants. Only the branches and roots of emerge plants provide shelter for aquatic organisms.

The following data were gathered by the Junior author Feb 21, 1994 at 11:00AM: Clear with blackwater influence, extremely acid. Current 0.5-1 mv/sec. Temp.: Air 29C, water 24C at more than 50cm depth... The fish fauna seems quite poor in species. Only 6 species were collected I the brook, including Tucanoichthys tucano: Two cichlids, Nannacara adoketa, and Crenicichla sp., one catfish, a doradid Amblydoras sp.; and an as yet unidentified Rivulus, abundant; the only other characoid, probably syncopic, was Poecilocharax weitzmani."

Yeah, it turned out to be the ichthyological description of the little "Tucano Tetra", and was a treasure trove of data on both the fish and its habitat. I was taken by the decidedly "aquarium reproducible" characteristics of the habitat, both in terms of its physical size and its structure.

Boom! I was hooked.

I needed to replicate this habitat! And how could I not love this little fish? I even had a little aquarium that I had been dying to work with for a while.

It must have been "ordained" by the universe, right?

Now, I admit, I wasn't interested in, or able to safely lower the pH down to 4.3 ( which was one of the readings taken at the locale), and hold it there, but I could get the "low sixes" nailed easily! Sure, one could logically call me a sort of hypocrite, because I'm immediately conceding that I won't do 4.3, and I suppose that could be warranted...

However, there is a far cry between creating 6.2pH for my tank, which is easy to obtain and maintain for me, and "force-fitting" fishes to adapt to our 8.4pH Los Angeles tap water!

So, even the "create the proper conditions for the fish instead of forcing them to adapt to what's easiest for us" philosophy can be nuanced! And it should! I don't want to mess with strong acids at this time. It's doable...a number of hobbyists have successfully. However, for the purposes of my experiment, I decided to abstain for now, lol.

And without flogging a dead horse, as the horrible expression goes, I think I nailed many of the physical attributes of the habitat of this fish. By utilizing natural materials, such as roots, which are representative of those found in the fish's habitat, as well as the use of Ficus and other small leaves as the "litter" in the tank, I think I'm well on the way to creating a cool biotope-inspired display for these little guys!

That's one example of this philosophy in action. Again, it's NOT perfect. It's certainly something that can- and should- be improved upon. The pH thing, for example. But the physical environment; the biological nuances...the long-term function of this type of aquarium microcosm...I think we are well on our way to building a lot of "best practice" stuff here.

I'm still not satisfied yet...

However, I think it's a good start.

I think it also requires the usual caveats- a "mindset shift" that embraces the fact that the natural habitats we love don't always meet our "acculturated" aesthetic expectations. We need to understand that Nature does her own thing, regardless of whether we "approve" of it or not!

Keep striving.

Stay bold. Stay studious. Stay curious. Stay diligent. Stay open-minded. Stay methodical...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics