- Continue Shopping

- Your Cart is Empty

Food production: The ultimate "collateral benefit" of the botanical-style aquarium?

We are receiving a lot of really interesting inquiries from so many hobbyists in our community regarding the "collateral" benefits of utilizing botanicals in our aquariums.

Among the most interesting and exciting one of these collateral benefits is the potential for supplemental internal food production as a result of cultivating a "bed" of leaves and other botanicals in our aquariums.

Yeah, food production.

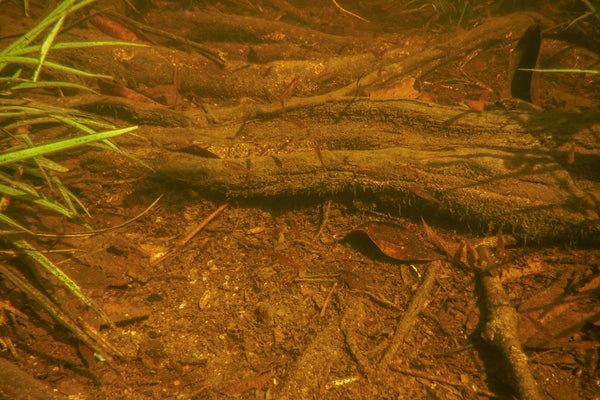

As always, the inspiration- and "archetype" for this food production process is Nature, Herself. And one of the more fascinating habitats where food production occurs in the wild is the flooded forest floors of South America.

Now, we've talked extensively in several blog posts over the past couple of years about the idea of allochthonous input (literally, "food from the sky", lol) and how it impacts the feeding habits of many fishes, as well as their social and behavioral habits, and what could loosely be referred to as their "migratory patterns."

It's long been known that fishes which inhabit the flooded forest floors (igapo) of Amazonia, for example, tend to literally "follow the food" and move into new areas where greater feeding opportunities exist, and will even adjust their dietary preferences seasonally to accommodate the available foods.

In this instance, it typically means areas of the forest where overhanging vegetation offers falling peices of fruit, seeds, nuts, plant parts, and the occasional clumsy insect, like an ant, which falls from the branches of said vegetation. So, here is where the idea gets interesting to me: Wouldn't it make a lot of sense to create a botanical-style aquarium which not only represents the appearance of the habitat, but also replicates, to a certain extent, the function of it?

Of course it would! (Surely, you wouldn't have expected any other answer from me, right?)

Many other fishes which reside in these flooded forest areas feed mainly on insects; specifically, small ones, such as beetles, spiders, and ants from the forest canopy. These insects are likely dislodged from the overhanging trees by wind and rain, and the opportunistic fishes are always ready for a quick meal!

Interestingly, it's been postulated that the reason the Amazon has so many small fishes is that they evolved as a response to the opportunities to feed on insects served up by the flooded forests in which they reside! The little guys do a better job at eating small insects which fall into the water than the larger, clumsier guys who snap up nuts and fruits with their huge mouths!

And, yes, many species of fishes specialize in consuming detritus. More on that later!

As we know by now, decomposing leaves are the basis of the food chain, and the detritus they produce forms an extremely important part of the food chain for many, many species of fishes. Some have even adapted morphologically to feed on detritus produced in these habitats, by developing bristle-like teeth to remove it from branches,tree trunks, plant stems, and leaf litter beds.

Of course, it's not just the fishes which derive benefits from the terrestrial materials which find their way into the water. Bacteria, fungi, and algae also act upon the nutrients released into the water by the decomposing organic material from these plants. Aquatic plants (known collectively to science as macrophytes) grow in or near water and are either emergent, submergent, or floating, and play a role in "filtering" these flooded habitats in nature.

Terrestrial trees also play a role in removing, utilizing, and returning nutrients to the aquatic habitat. They remove some nutrient from the submerged soils, and return some in the form of leaf drop.

Interestingly, studies show that about 70% of the leaf drop from the surrounding trees in the igapo habitats occurs when the area is submerged, but the bulk of it is shedded by the trees at the end of the inundation period. The falling leaves gradually decompose and become part of the detritus in the food web, which is essential for many species of fishes. This "late-inundation leaf drop" also sets things up for the "next round" - providing a "starter" of nutrients !

Our ability to mimic this aspect of the flooded forest habitats is a real source of benefits for the fishes that we keep- and a key to unlocking the secrets to long-term maintenance and husbandry of botanically-influenced aquariums.

The transformation of dry forest floors into aquatic habitats provides a tremendous amount if inspiration AND biological diversity and activity for both the natural environment and our aquariums. There are many takeaways for hobbyists that can be had by studying these habitats.

Flood pulses in these habitats easily enable large-scale "transfers" of nutrients and food items between the terrestrial and aquatic environment. This is of huge importance to the ecosystem. As we've touched on before, aquatic food webs in the Amazon area (and in other tropical ecosystems) are very strongly influenced by the input of terrestrial materials, and this is really an important point for those of us interested in creating more natural aquatic displays and microcosms for the fishes we wish to keep.

Creating an aquascape utilizing a matrix of leaves, roots, and other botanical materials, is one of my favorite "aesthetic interpretations" of this habitat...and it happens to be supremely functional as an aquarium, as well! I think it's a "prototype" for many of us to follow, merging looks and function together adeptly and beautifully.

And with the ability to provide live foods such as small insects (I'm thinking wingless fruit flies and ants)- and to potentially "cultivate" some worms (Bloodworms, for sure) "in situ"- there are lots of compelling possibilities for creating really comfortable, natural-appearing (and functioning) biotope/biotype aquariums for fishes.

And of course, when you're talking about creating a rich bed of botanicals, consisting of decomposing organic materials (leaves, coco-fiber, and other botanicals containing lignin, etc.), that creates a matrix that may eventually consist of- and perhaps accumulate- what we'd collectively call "detritus."

Oh, my God. NOT DETRITUS! Here we go again...

So think about it for a second before you go all berserk:

Is "detritus", or other finely processed organic material the "doomsday machine" that many "experts" have long predicted will destroy your aquarium?

I don't think so.

I know-we all know- that uneaten food and fish poop, accumulating in a closed system can be problematic if overall husbandry issues are not attended to. I know that it can decompose, overwhelm the biological filtration capacity of the tank if left unchecked. And that can lead to a smelly, dirty-looking system with diminished water quality. I know that. You know that. In fact, pretty much everyone in the hobby knows that.

Yet, we've sort of heaped detritus into this "catch-all" descriptor which has an overall "bad" connotation to it. Like, anything which is allowed to break down in the tank and accumulate is "bad."

We're not talking about a substrate composed entirely of uneaten food and fish poop here. That's a different issue and a different problem. Now, I agree, it requires a lot of understanding and a real mental shift to embrace the idea of loving detritus in your tank.

The definition as accepted in the aquarium hobby is admittedly kind of sketchy in this regard; not flattering, at the very least:

"detritus is dead particulate organic matter. It typically includes the bodies or fragments of dead organisms, as well as fecal material. Detritus is typically colonized by communities of microorganisms which act to decompose or remineralize the material." (Source: The Aquarium Wiki)

That being said, everyone thinks that it is so bad.

I'm just not buying it.

Why is this necessarily a "bad" thing?

It's not.

In Nature, the leaf litter "community" of fishes, insects, fungi, and microorganisms is really important to the overall tropical environment, as it assimilates terrestrial material into the aquatic system, produces and consumes detritus, and acts to reduce the loss of nutrients to the forest which would inevitably occur if all the material which fell into the streams was washed downstream!

The key point: These materials and their resulting detritus foster the development of life forms which process these materials. Stuff is being used by life forms.

It goes without saying that the same processes which occur in Nature occur in our tanks- if we let them.

And botanical materials not only provide a "substrate" upon which these organisms can grow and multiply- they provide a sort of "on board nutrient processing center" within the aquarium. In my experience, based on literally a lifetime of playing with all sorts of combinations of materials in my aquariums' substrates ('cause I've always been into that weird shit!), I cannot attribute a single environmental lapse, let alone, a "tank crash", as a result of such additions or their resulting breakdown in otherwise well-managed aquairums.

I am of the opinion that a botanical-style aquarium, complete with its decomposing leaves and seed pods, can serve as a sort of "buffet" for many fishes- even those who's primary food sources are known to be things like insects and worms and such. Detritus and the organisms within it can provide an excellent supplemental food source for our fishes!

They give our fishes "options" to supplement their diets!

It's well known that in many wild habitats, like inundated forests, etc., fishes will adjust their feeding strategies to utilize the available food sources at different times of the year, such as the "dry season", etc. And it's also known that many fish fry feed actively on bacteria and fungi in these habitats...so I suggest once again that a blackwater/botanical-style aquarium could be an excellent sort of "nursery" for many fish species!

You'll often hear the term "periphyton" mentioned in a similar context, and I think that, for our purposes, we can essentially consider it in the same manner as we do "epiphytic matter." Periphyton is essentially a "catch all" term for a mixture of cyanobacteria, algae, various microbes, and of course- detritus, which is found attached or in extremely close proximity to various submerged surfaces. Again, fishes will graze on this stuff constantly.

Of course, anyone who keeps a planted aquarium could attest to that, right?

I firmly believe that the idea of embracing the construction (or nurturing) of a "food web" within our aquariums goes hand-in-hand with the concept of the botanical-style, blackwater (and brackish!) aquarium. With the abundance of leaves and other botanical materials now available to "fuel" the fungal and microbial growth, and the diligent husbandry and intellectual curiosity of the typical "tinter" (that's YOU!), the practical execution of such a concept is not too difficult to create, understand...and embrace!

We are truly positioned well to explore and further develop the concept of a "food web" in our own systems, and the potential benefits are enticing!

Appetizing?

We think so!

Stay curious. Stay resourceful. Stay excited. Stay creative...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

U-Turns, detours, and changes in direction...

If you've been in the aquarium hobby for any appreciable length of time, you likely try all sorts of things; Some are as simple as trying a different type of fish, a planted aquarium, or a new technique. This is what keeps our hobby so amazing; so vital and engrossing. There are endless possibilities. Even after decades, I'm constantly finding new avenues to explore.

Of course, "detours" can also be edits and changes we make to our existing ideas. For example, I'll often start out with an idea or a "theme" for one of my tanks, only to get it up and running and ultimately reach a point where I am compelled to make changes.

Detouring.

Then again, what's wrong with epiphanies, edits on the fly, and wholesale changes to our best-laid plans?

Nothing at all. In fact, they can often lead to our best work. It's great to take the those little "side trips" in the hobby!

I know that I've done this before.

"Iterating" stuff to the point of obliterating my original concept. Changing things to such a great extent as to be completely different from what I originally intended to do. I remember in my early reef keeping days, this would happen a lot. It still happens today.

Move that one piece of wood, or switch out that one coral colony for the purpose of "creating flow" or "making room for growth", or whatever- only to realize that a seemingly well-intentioned, simple change did not stand alone. Rather, it required me to move two other pieces of wood; re-position one other coral colony...all of which resulted in completely different look and feel than I originally envisioned!

I think such "detours" are often beautiful- often leading to new ideas, new discoveries, new aesthetics, and inspiration for others. Things happening in unexpected ways are what can propel the hobby forward.

Everything doesn't have to follow a plan.

A detour can be amazing.

However, if your looking for a specific result and go too far in a different direction, it's often a recipe for frustration for those of us not prepared of it. Sure, many of us can simply "go with the flow" and accept the changes we made as part of the process, but the aquarist with a very pure vision and course will work through such self-created deviations until he or she gets to the destination. Many find this completely frustrating. Others find this a compelling part of the creative process.

Open your mind.

All of it is part of the journey.

Detours and "edits" or whatever you want to label them help us perfect our craft, hone our skills, challenge our minds...and, if we're really lucky-they help create outcomes we never even imagined.

And the process usually starts with one rock. One piece of wood...One thought.

Occasionally, I'll have what seems like a great idea for a tank in my head. Except, when I start executing on it, I'll find out that it's not really what I wanted to do. Maybe my heart wasn't it it? Not sure. It just doesn't feel right- and I can't enjoy it. Strange, right? However, I'm sure some of you can relate?

Recently, I had an idea for a tank- a tangle of lots of wood, with terrestrial plants poking through above the waterline. It was based on some images I'd seen of wild habitats, and it seemed like a good idea. I had an aquarium with the right footprint to work with, and I started to play with it.

And it was kind of interesting. Except for the fact that I never quite got it the way I liked below the waterline. It just didn't feel right.

I just felt like I could do better with it somehow. Of course, I ended up being my own worst enemy on this one. I questioned my own idea, got contaminated by seeing similar concepts, executed differently and perhaps far better than mine, in terms of the plant life, and I just sort of lost interest in it.

I mean, it wasn't "bad"- it just wasn't right somehow. Not right for me, anyways.

It was like my heart just told me that perhaps it wasn't what I really wanted to do. Like, it felt forced- overly influenced by what I was seeing online and elsewhere...and just felt bad. "Unauthentic." Not me. Like, I was feeling navigating into an area that I really wasn't into. Perhaps for the wrong reasons. It was weird. And it wasn't like I was impatient with it...I just didn't like what I was doing with it.

Ever feel that?

And I was feeling the call of my beloved mangroves.

I knew from experience that these guys would really grow well and look great in a shallow, wide aquarium. I'd had my current batch of seedlings in various small containers for anywhere from 2 to 5 years, and they really needed to be given a more permanent home.

And I'd been playing with my NatureBase substrates, with the upcoming release of my brackish substrate called "Mangal", and it seemed as good a time as any to put it through its paces in this tank! And besides, it was time for another proper brackish tank! One that could tide me over for a few years until it was time for a bigger one!

So, down came the "weird" concept and up came a more comfortable, yet more "honest" (for me) idea.

Now, it's always good to try new things. Sometimes it's even better to push yourself to get out of your comfort zone a bit. Other times, it's just best to do what you love.

Because you love it.

Yeah.

Detours can take you into some new and very exciting areas!

A detour can be amazing.

Open your mind.

Elevate your experience by doing what moves you.

Keep trying new stuff. Get out of your comfort zone. Push out the boundaries...look at your work from a different perspective. Draw as much inspiration from the work of Nature as is possible. If this kind of stuff calls to you..compells you..moves you in some way- please enjoy this...and share it with the world.

Stay unique. Stay bold. Stay curious. Stay inspired. Stay educated. Stay creative...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquati

The same old song- The "universality" and "reliability" of botanical materials

One of the most amazing things about our practice of adding leaves, twigs, seed pods, snd other botanical materials to our aquariums is that they can be almost "relied on" to perform in a fairly predictable manner in our aquariums.

The same natural processes which affect the decomposition of an Alder Cone from Europe impact the Sterculia pod from Southeast Asia, the oak twig from North America, the Jackfruit leaf from Malaysia, or the Banana Stem from Thailand. Colonization by biofilms, fungal growths, and the resulting decomposition which occurs are the same all over the planet.

And they're the same processes which govern what happens in our aquariums.

Think about that for just a second.

We receive a LOT of questions from our community, asking what botanical is suitable for a tank intended to represent a specific environmental niche or geographic area. The answer isn't always as simple as "use this leaf" or whatever.

The reality is more nuanced, really.

We should understand the overall idea that the way Nature functions is the same, regardless of what materials you're using to do the job. I know, I'm being redundant here.

It's a really important point, specifically for those of you who are just hell-bent on assuring yourself that every leaf, twig, and seed pod in your Southeast Asian-themed aquarium is, indeed from Southeast Asia! NEWS FLASH: It doesn't have to be. Yeah, unless you live in the area that you're trying to represent in your tank, or are really dialed in to a good supply of whatever botanicals are native to that region, you're going to have to use stuff that's largely representative of what comes from there. And that's just fine.

Often, I'll come up with an idea for the aquarium representation of a unique niche habitat, and will spend a lot of time researching the ecology and, more important to me- the function of the habitat, before embarking on my project.

And yeah, more often than not, I'll find that the plants, wood, leaves, or whatever that I need to really nail the project in a a full-on "biotopic manner" are simply not available to me.

And guess what? That's okay. I don't "get stuck."

I just don't get stressed-out about it.

You shouldn't, either.

I receive a lot of emails from fellow hobbyists who are "stuck" because they can't find that exact plant...And so they dramatically change, or even abandon their projects.

A real shame.

A suggestion, if I may?

Look for some sort of analog.

Now, sure, I can make dozens of arguments for why a serious biotope aquarium should have only stuff from the given region, but I'd be lying to myself. Practicality has to reign sometimes. You simply can't get every single leaf or seed pod that is found in any given geographic area, for all sorts of reasons. I mean, you certainly should try- we do...and it's a kind of fun pastime for some of us!

The reality is that most of the stuff you can use in your Southeast Asia-themed tank looks very similar to the actual materials found in the region. I mean, as I've often said, I challenge virtually any judge in contest to determine if the decomposing Guava leaf from Borneo in your Amazon-themed display is really a Hevea brasiliensis, from the Amazon region.

And even more important, the same processes of Nature which impact the leaves when they fall into the water in the Amazon occur in your home in suburban Los Angeles, Paris, or Tokyo, for that matter.

Nature doesn't care.

Sure, there are subtle chemical, mineral, and other physical variations in the tap water in different parts of the world, which, if I'm being intellectually honest, could make some difference-but the ecological processes which decompose leaves are the same.

It's pretty remarkable, when you think about it!

When viewed as a "whole", the macro view of a botanical-style aquarium is that it challenges us to look at the big picture- to not get too caught up in any one aspect of creating or managing our aquarium...and to appreciate all of the process by which Nature does its work. And to make a "mental shift" to understand that everything we see in the aquarium is exactly what Nature intends.

I think we're starting to see a new emergence of a more "holistic" approach to aquarium keeping...a realization that we've done amazing things so far, keeping fishes and plants in a glass or acrylic box with applied technique and superior husbandry...but that there is tons of room to experiment and push the boundaries even further, by understanding and applying our knowledge of what happens in the real natural environment.

You're making mental shifts...replicating Nature in our aquariums by achieving a greater understanding of Nature.

The possibilities are endless, and the potential gains in knowledge and understanding of the wild habitats- and experience with replicating them in the aquarium- are incalculable. What secrets will we unlock? What practices will yield benefits and advantages that we never even considered?

There are no "flaws" in Nature's work, because Nature doesn't seek to satisfy observers. It seeks to evolve and change and grow. It looks the way it does because it's the sum total of the processes which occur to foster life and evolution.

We as hobbyists need to evolve and change and grow, ourselves.

We need to let go of our long-held beliefs about what truly is considered "beautiful." We need to study and understand the elegant way Nature does things- and just why natural aquatic habitats look the way they do. To look at things in context. To understand what kinds of outside influences, pressures, and threats these habitats face.

It's entirely possible to accept the appearance of biofilms, "murky" water, algae, decomposing botanical materials, and how systems embracing them can be managed to take advantage of their benefits. You know, accepting them as supplemental food sources, "nurseries" for fry, and as interesting little ways to impart beneficial humic substances and dissolved organics into the water.

It starts by looking at Nature as an overall inspiration.

Wondering why the aquatic habitats we're looking at appear the way they do, and what processes create them. And rather than editing out the "undesirable" (by mainstream aquarium hobby standards) elements, we embrace as many of the elements as possible, try to figure out what benefits they bring, and how we can recreate them functionally in our closed aquarium systems.

The "different aesthetics" simply come along as "part of the package"- both in Nature and in the aquarium.

And the functions. Well, they're the same, regardless of what your aquarium looks like.

Stay true to yourself. Stay curious. Stay enthralled. Stay brave. Stay thoughtful. Stay diligent...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Too much is never enough...Or, is it?

IN the botanical-style aquarium world, our work is largely predicated on the complimentary work that Nature does. She's our ally, our partner. The idea that. an aquarium filled with leaves, twigs, and other botanical materials is not some "alternative" to our "standard practices"- it IS our standard practice!

One of the questions thatr we receive all the time is, "How much of this stuff should I add to my tank? Is there such a thing as too much?"

Well, that's a really good question. Keep in mind that this question, typically- and the context of today's piece, is in regards to converting an existing aquarium to a botanical-style one. If you're starting from scratch, without fishes, you can do things a bit differently, as we have mentioned previously.

And I think that it starts with understanding how to develop a cadence for your tank.

Huh?

ˈkādns/ noun- The flow or rhythm of events, especially the pattern in which something is experienced.

Remember, anything you add into an aquarium- wood, sand, botanicals, and of course- livestock- is part of the "bioload", and will impact the function and environment of your aquarium. It's about understanding a balance, a quantity, a "cadence" for adding stuff, so that the closed environment of your aquarium can assimilate the new materials, and the bacteria, fungi, and other organisms which serve to break them down can adjust.

Adding botanicals to your tank is as much about how fast as it is about how much.

Rapid, dramatic environmental shifts are never a good thing for any type of aquarium, and a system like we run, with lots of organic material present, is just as susceptible to insults from big moves as any other- perhaps even more.

You certainly can wipe out your aquarium by going to fast and too hard. I've seen it before. In fact, typically, the only "problems" that our customers have reported over the years when using botanicals were caused by violating Nature's "speed limit"- adding too many botanicals to an established aquairum in too short of a length of time.

A recipe for trouble. Or worse.

Again, the key here is that "cadence"- understanding that the material we add needs to be added-and replaced- on a pace that makes sense for your specific system. Those of us who have been maintaining these types of tanks for some time now really get this, and have a great "feel" for how our tanks run in this fashion.

You need to deploy patientence.

Patience.

The single most important thing you need for a successful raquairum (well, except maybe cash!)- and the thing we celebrate the least, IMHO. And we should celebrate it a lot more.

Because you really can’t skip the process…

There is no "plug and play" formula to follow- only procedure. Only recommendations for how to approach things. We sound a bit like the proverbial "broken record"; however, like so many things in aquarium-keeping, our "best practices" are few, simple and need to be repeated until they simply become habit:

1) Prepare all botanicals prior to adding them to your aquarium.

2) Add botanical materials slowly and gradually, assessing the impact on your aquarium environments and inhabitants.

3) Either remove botanical materials as they break down (if that's your aesthetic preference), or replace them when they reach a point where they are no longer providing the aesthetic and environmental conditions that you desire.

This is pretty logical stuff, right?

If you noticed, the first practice is simply logical. You need to employ it...if there were ever a "hard and fast rule in the botanical/blackwater game, this would be it. We've covered it so many times here that it likely needs little repeating.

Number 2 is all about the cadence...the "secret", if you will, which sort of sets up everything else. By observing and assessing, you'll get a real feel for how botanicals work in your aquarium. What impact they are having on your fishes- and on the environment as a whole.

And Number 3 is the real "finesse" part of the equation...the nuance, the subtle, yet noticeable adjustments and corrections we make to keep things moving along nominally- sort of like pruning in a planted tank, or weeding a garden...it's a process.

This idea of process, cadence, observation, and timing is not something unique to botanical-style aquairums. Nor is it a sort of "recommendation." Rather- it's foundational.

In fact, the entire experience of a botanical-style aquarium boils down to a process and a pace that helps foster the gradual, yet inexorable "evolution" of the aquarium. And let there be no doubt- a botanical-style aquarium does "evolve" over time, regularly and steadily changing and progressing.

As we've mentioned before, it might just be the perfect expression of the Japanese concept of "wabi-sabi", popularized by Takashi Amano, which is the acceptance of transience and imperfection in all things.

It's a dance. A story.

And it's all held together by you- the aquarist, applying as much emotion as you do procedure- all done in the proper time...at the right cadence.

Of course, when you start adding botanical materials to your aquarium, not only are you sort of "buying in" to a different approach to aquarium-keeping- you're "signing up" to accept a completely different look than we are traditionally accustomed to. Yeah, we are "opting in" to techniques which are somewhat contrary to what you've likely embraced before. You're accepting an aesthetic which deviates strongly from the traditional aquarium "look" that we have been accustomed to for generations. And it doesn't stop with the looks of the tank...

It starts with the way we look at Nature.

Once we visit, or look at a photo or video of a natural underwater habitat where tropical fishes live, and remove our hobby-contrived preconceptions of what it should look like from the equation and simply observe it as it is- we have to ask ourselves if this is how we want our tank to look...

That's the first mental shift.

Like, can you handle this stuff?

It's the ultimate "essence" of our philosophy. A way of capturing aspects of Nature in our aquarium in a manner that accepts it as it is, rather than how we want it to be.

And if we say "Yes" to the question, we then need to ask ourselves if we're okay accepting the rather unorthodox thinking and practices that are required of us to get an aquarium to that place.

You know, like adding seed pods, leaves, soils, etc. to an aquarium in an effort to capture the form and function of these natural habitats. To adopt a philosophy that says, "It's time to take inspiration from the reality of Nature, not just its essence."

Accepting the appearance of biofilms, murky water, algae, decomposing botanical materials, and that these things occur in our aquariums, too, and can be managed to take advantage of their benefits. You know, as supplemental food sources, "nurseries" for fry, and as interesting little ways to impart beneficial humic substances and dissolved organics into the water.

Realizing that the very act of adding natural materials like seed pods and leaves fosters the development of biofilms, less-than-crystal-clear water, and detritus...And that this is what you actually WANT.

Another mental shift.

Understanding once and for all and accepting that things are not aesthetically "perfect" in Nature, in the sense of being neat and orderly from a "design" aspect. Understanding that, yeah, in nature, you have branches, rocks and botanical materials scattered about on the bottom of streams in a seemingly random, disorderly pattern. Or..are they? Could it be that current, weather events, and the processes of physical decomposition distribute materials the way they do for a reason?

Yeah.

Now, circling back to the question of if it's possible to add too much botanical materials to your aquarium:

Obviously, the question here is "how much stuff do I start with?" And of course, my answer is...I have no idea. Yeah, what a shocker, right? I realize that's the least satisfying, possibly least helpful answer I could give to this question. Or is it? I mean, taking into account all of the possible variables, ranging from the type of water your starting with, to what kind of substrate material you're using, it would be a shot in the dark, at best.

The best advice is to adapt a more generalized mantra:

Consider the environmental impact of the stuff you add to your established tank.

My advice is to start with conservatively small quantities of stuff...like, maybe a half a dozen leaves for every 15 US gallons (56.78L) of water, and a corresponding amount of seed pods, etc. If you're using water with little to no carbonate hardness, you could see a decrease in pH after adding botanicals. At first, you might not even notice any difference..or you might see a .2 reduction in pH...You have to test.

I recommend a digital pH meter for best accuracy.

If you're getting a sort of feeling that this is hardly a scientific, highly-choreographed, one-size-fits-all process....you're totally right. It's really a matter of (as the great hobbyist/author John Tullock once wrote) "Test and tweak." In other words, see what the hell is going on before making adjustments. Logical and time-tested aquarium procedure for ANY type of tank!

And then you have to consider the biological impact of these additions on your aquarium.

Adding to much botanical material to your tank too quickly could overwhelm the existing bacterial populations in your aquarium, and their ability to handle organics. This could result in an ammonia or nitrite "spike."

Now, there is some good news here amidst all of the cautions!

Pretty much anything that we add to the aquarium contains some biological material (ie. bacteria, fungal or algal spores, etc.), right? And when they hit the water, it begins a process of growth, colonization, and proliferation that won't stop. These processes are so beneficial and important to our systems...

When we have these materials in place, the "microfaunal ecosystem" begins to "ignite" and grow. We often talk about the large influx of "nutrients" present in a new aquarium, and "immature" nutrient export systems in place to handle it. I mean, the tank plays a sort of biological "catch up" during this time, as the bacterial and fungal growths proliferate among the abundant nutrients.

We might rely a bit more on mechanical and chemical filtration during this period. However, ultimately, these natural "nutrient export mechanisms" will take over.

It just takes time.

And a mindset where you're not totally obsessed with removing every bit of "dirt" or material which looks offensive. Allowing the the nitrogen cycle to really establish itself, and natural processes develop, will really "set the tone" for our botanical-style aquariums, IMHO. We shouldn't let some of the initial visual clues, like "cloudiness", biofilms, etc. compel us to whip out the siphon hose and remove every bit of the "offensive"-looking material from our tanks. Otherwise, we end up working agains the very processes that we're trying to foster in a botanical-style aquarium!

It takes patience, understanding, observation- and a vision.

And we are patient.

And determined.

And we understand that a botanical-style aquarium truly must "evolve" and take time to begin to blossom into a functioning little ecosystem. And we enjoy each and every stage of the "startup" process for what it is: An analog to the processes which occur in the natural habitats we want so badly to emulate. I think one of the mental "games" I've always played with myself during this process is to draw parallels between what I'm doing to prepare my tank and what happens in Nature.

It kind of goes something like this:

A tree falls in the (dry) forest (Really, Fellman's riffing about trees AGAIN? Well, yeah...). Wind and gravity determine its initial resting place (you play around with positioning your wood pieces until you get 'em where you want, and in a position that holds!). A little rain falls (we spray down our hardscapes...), moistening the dry materials that abound in the substrate.

Next, other materials, such as leaves and perhaps a few rocks become entrapped around the fallen tree or its branches (we set a few "anchor" pieces of hardscaping material into the tank). Detritus settles (you know, that damn "sediment" that you get in newly setup tanks...) Then, the heavier rain comes; streams overflow, and the once-dry forest floor becomes inundated (we fill the aquarium with water).

The action of water and rain help "set" the final position of the tree/branches, and wash more materials into the area influenced by the tree (we place more pieces of botanicals, rocks, leaves, etc. into place). The area settles a bit, with occasional influxes of new water from the initial rainfall (we make water chemistry tweaks and maybe a top-off or two, as needed).

Fungi, bacteria, and insects begin to act upon the wood and botanicals which have collected in the water (kind of like what happens in our tanks, huh? Yes- biofilms are beautiful...). Gradually, the first fishes begin to follow the food and populate the area (we add our first fish selections based on our stocking plan...). It continues from there.

Get the picture? Sure, I could go on and on attempting to painfully draw parallels to every little nuance of tank startup and evolution, but I think you know where I'm going with this stuff...

And the thing we must deploy at all times in this process is patience.

And an appreciation for each and every step in the process, and how it will influence the overall "tempo" and ultimate success of the aquarium we are creating. When we take the view that we are not just creating an "aquatic display", but a habitat for a variety of aquatic life forms, we tend to look at it as much more of an evolving process than a step-by-step "procedure" for getting somewhere.

We need to stop looking for shortcuts and cheap ways to do everything in this hobby. I'm not saying just spend tons of money and do everything the hard way. I AM saying that we occasionally have to do things in a more roundabout, more costly way, simply because these are sometimes the best ways to do it. We need to always place the welfare of our animals ahead of our desire to get what we want as quickly and inexpensively as possible.

We must always, ALWAYS preach patience. We need to continue to demonstrate and discuss that these types of aquariums are the result of embracing patience, process, diligence, and self-education.

Go slowly. Don't add too much stuff too your established aquarium too quickly.

Too much IS likely too much!

Stay patient. Stay cautious. Stay observant. Stay determined. Stay curious. Stay grounded..

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Edits, iterations, and big moves: evolving an aquarium over time.

Over the years, I know that I've learned a few things about managing my aquariums over the long term. The most interesting lesson to me is that you can always make changes, evolutions, and iterations...without completely breaking down the tank as you do them.

You can make seemingly dramatic changes to your aquariums, and yet still leave considerable parts of them intact and functional.

The idea of leaving the substrate and leaf litter/botanical "bed" intact as you "remodel" isn't exactly a crazy one. And conceptually, it's sort of replicates what occurs in Nature, doesn't it? Materials accumulate on top of other materials, facilitating new biological growth, continued foraging for resident fishes, and a more or less uninterrupted ecology.

Yeah, think about this for just a second.

As we almost constantly discuss, habitats like flooded forests (Igapo and Varzea), meadows, vernal pools, igarape, and swollen streams tend to encompass terrestrial habitats, or go through phases where they are terrestrial habitats- for a good part of the year.

In these wild habitats, the leaves, branches, soils, and other botanical materials remain in place, or are added to by dynamic, seasonal processes. For the most part, the soil, branches, and a fair amount of the more "durable" seed pods and such remain present during both phases.

The formerly terrestrial physical environment is now transformed into an earthy, twisted, incredibly rich aquatic habitat, which fishes have evolved over eons to live in and utilize for food, protection, and complex, protected spawning areas.

All of the botanical material-shrubs, grasses, fallen leaves, branches, seed pods, and such, is suddenly submerged; often, currents re-distribute the leaves and seed pods and branches into little pockets and "stands", affecting the (now underwater) "topography" of the landscape.

Leaves begin to accumulate. Detritus settles.

Soils dissolve their chemical constituents- tannins, and humic acids- into the water, enriching it. Fungi and micororganisms begin to feed on and break down the materials. Biofilms form, crustaceans multiply rapidly. Fishes are able to find new food sources; new hiding places..new areas to spawn.

Life flourishes.

Sooo...

When you remove much of the hardscape, plants, etc. from the aquarium as you "evolve" it to something else, yet leave the substrate, some of the hardscape, leaves, etc. intact, you're essentially mimicking this process in a most realistic way.

Sure, a "makeover" of an aquarium can be a seriously disruptive event (for both YOU and your fishes!).

On the other hand, if you take the mindset that this is a "transformation" of sorts, and act accordingly, it becomes more of an evolutionary process.

This is something I've done for many years- like a lot of you have, and it not only makes your life a bit easier- it can create pretty good outcomes for the fishes we keep.

The "Urban Igapo" idea that I've been touting for a good part of the year is a very deliberate execution of this iterative process, and it's taught me quite a bit about how these habitats function in Nature, and what kinds of benefits they bring to the aquarium.

We've talked about the idea of "flooding" an aquarium setup designed to replicate an Amazonian forest before. You know, sort of attempting to simulate some of the processes which happen seasonally in Nature. With the technology, materials, and information available to us today, the capability of creating a true "year-round" habitat simulation in the confines of an aquarium/vivarium setup has never been more attainable.

The time to play with this concept is now!

We've been playing with the idea for a long time, and spent a long time formulating our "NatureBase" soils, which attempt to replicate some of the attributes of those found in these habitats during the "dry" season. When flooded, you get an effect that's similar to what happens in the igapo.

Sure, the water gets cloudy for a bit. The water is tinted, turbid, and sediment-laden. Eventually, it settles out. If you planted grasses and plants which are able to tolerate submersion for some period off their life cycle, they'll "hang on" for a while- until the waters recede.

Just like in Nature.

And you can go through multiple "wet and dry seasonal cycles" with the same substrate and perhaps only a slight addition of materials to replenish those which have broken down, but the result is a "continuous aquarium"- one which can stay more-or-less intact over a long period of time and iterations.

This can work in all types of aquariums- large and small.

No one said the hobby is easy, but it’s not difficult, either- as long as you have a basic understanding of the environmental processes and conditions within your aquarium. You can be fairly aggressive at "remodeling" your tank without fear of the tank "cycling" again, in my experience.

And the idea of leaving essential biological components of your aquarium more-or-less "intact" for an indefinite period of time is really compelling.

Of course, an aquarium which utilizes botanicals as a good part of its hardscape follows a set of phases, too. And I've found that once a botanical-style aquarium (blackwater or brackish) hits that sort of "stable mode", it's just that- stable. You won't see wildly fluctuating pH leaves, nitrates, phosphates, etc. To a certain degree, the aquarium has achieved some sort of "biological equilibrium."

Of course, the thing that's unique about the botanical-style approach is that we tend to accept the idea of decomposing materials accumulating in our systems. We understand that they act, to a certain extent, as "fuel" for the micro and macrofauna which reside in the aquarium. The idea of leaving this material in place over the long-term is a crucial component of this approach, IMHO.

As we've discussed repeatedly, just like in Nature, they'll also form the basis of a complex "food chain", which includes bacterial biofilms, fungi, and minute crustaceans. Each one of these life forms supporting, to some extent, those above...including our fishes.

So, when you're contemplating and executing your "evolutions" I have long believed that if you decide to let the botanicals remain in your aquarium to break down and decompose completely, you shouldn't change course by suddenly removing the material all at once...Particularly if you're going to a new version of an existing aquarium.

Why?

Well, I think my theory is steeped in the mindset that you've created a little ecosystem, and if you start removing a significant source of someone's food (or for that matter, their home!), there is bound to be a net loss of biota...and this could lead to a disruption of the very biological processes that we aim to foster.

Okay, it's a theory...But I think I might be on to something, maybe? So, like here is my theory in more detail:

Simply look at the botanical-style aquarium (like any aquarium, of course) as a little "microcosm", with processes and life forms dependent upon each other for food, shelter, and other aspects of their existence. And, I really believe that the environment of this type of aquarium, because it relies on botanical materials (leaves, seed pods, etc.), is more signficantly influenced by the amount and composition of said material to "operate" successfully over time.

Just like in natural aquatic ecosystems...

The botanical materials are a real "base" for the little microcosm we create.

And of course, by virtue of the fact that they contain other compounds, like tannins, humic substances, lignin, etc., they also serve to influence the water chemistry of the aquarium, the extent to which is dictated by a number of other things, including the "starting point" of the source water used to fill the tank.

So, in short- I think the presence of botanicals in our aquariums is multi-faceted, highly influential, and of extreme importance for the stability, ecological balance, and efficiency of the tank.

Okay, I might just be torturing this simple idea to death- I admit this point that I'm probably not adding much more to the "recipe" here; likely simply being redundant and even a bit vague- and "multi-faceted" sounds liek a poor way of saying, "They do a lot!"...However, I think we need to think about how interesting this simple practice is.

And yeah, I'll concede that we probably don't have every answer on the processes which govern this stuff. In fact, we barely have any, really...

For example:

The most common question I get when it comes to taking out a fair amount of this material and then "continuing" the tank is, "Will it cycle again?"

And the answer is...It could.

On the other hand, here is my personal experience: Remember, I keep a sort of diary of most of my aquarium work. I have for over three decades (gulp...). Just random scanning my "diary", I see that I have executed this practice dozens of times in all types of aquariums, ranging from simple planted aquariums to hardscape-only tanks, to botanical-style, blackwater and brackish aquariums, to reef tanks.

Not once- as in never- have I personally experienced any increase in ammonia and nitrite, indicative of a new "cycle."

Now, this doesn't mean that I guarantee a perfect, "cycle-free" process for you. On the other hand, by leaving the bulk of the substrate material intact, and continuing to provide "fuel" for the extant biotia by leaving in and adding to the botanicals present in the aquarium, this is entirely possible, as my experiences have shown me.

Some of you have asked why I'm so confident in my ability to iterate tank in this rather aggressive fashion. No, it's not because I'm some brilliant pioneer who knows something others don't.

Nope.

It's because I-like many of you- have adopted a special mindset.

A mindset- and consistent husbandry practices that assure success with this process.

Ridiculously consistent.

I am a fanatical observer of my aquariums, particularly the botanical-style ones I run (oh, all of them...), and I do the same things over and over and over again; specifically, weekly small water exchanges. I don't overcrowd my tanks. I don't add tons of fishes at one time. I don't overfeed my fishes. I don't add a large batch of botanicals at one time to "remodeled" or existing aquariums. I'm annoyingly patient. I don't freak out over things taking a while.

I embrace "detritus" ( at least the kind that is caused by mineralization of botanical materials) as "fuel" for the biological "operating system"- not as something to be afraid of.

And, like many of you, I don't see a need to rush to some version of "finished."

Personally, I don't think that botanical-style aquariums are ever "finished." They simply continue to evolve over extended periods of time, just like the wild habitats that we attempt to replicate in our tanks do...

And the botanicals in the aquarium? Well. they'll keep breaking down, "enriching" the aquarium habitat. Imparting humic substances, lignin, etc. Compounds which have a material impact on the ecology, biology, and chemistry of the aquarium.

Understand and facilitate these natural processes into your aquariums. Keep that in mind when you "iterate" an aquarium.

If you're months into a tank, and simple don't like the look or performance or whatever- you can easily change it. It's a lot like catching a continuously-running commuter train or subway line, right? There's always an opportunity to go somewhere new. You just have to jump on.

Part of the beauty of the botanical-style aquarium is that you can sort of "pick it up where you are" and "ride it" out for a while, or change the "routing" as you desire! Started your tank as an Amazonian habitat but you're suddenly enamored with a more "Asian" look?

Keep the "operating system" intact, but change out some elements. Don't feel compelled to "siphon out all of the detritus" or whatever the B.S. that you hear regurgitated when people talk about tank makeovers. Unless you're tearing apart the tank because it's a smelly, stinky, mismanaged, toxic pile of shit that's killing your fishes, keep the biological "fuel" intact for your new iteration! (and vow to take better care of your tank this time!)

Super easy, right?

It is. If you let it be that way.

Evolution in our aquariums is not only fun to watch, it's a lot of fun to manage as well. And it's even more fun to have the option to do either!

Our aquariums can operate continuously for indefinite periods of time if we allow them to do so. It's a compelling, fascinating idea and process.

Enjoy it.

Look out below! The alluring world of "alternative substrate materials!"

When it comes to freshwater aquariums in general, and botanical-style aquariums, specifically, the substrate has always been sort of an "afterthought." A component of the overall aquarium that has been largely viewed as, well- a component and little more. Something that you pour on the bottom of the tank, smooth it out, and move on to more "exciting" stuff...

And that's kind of a shame, right?

I mean, the substrate is more than just something to cover the bottom of the aquarium with. Rather, it's an important part of the overall miniature ecosystem that we create in our tanks. In fact, it's sort of an ecosystem in and of itself- a fascinating and compelling part of our aquariums!

If you're a regular consumer of our content, you know of my obsession with varying substrate compositions and what I call "enhancement" of the substrate- you know, adding mixes of various materials to create different aesthetics and function.

I'm fascinated with this stuff partly because substrates and the materials which comprise them are so intimately tied to the overall ecology of the aquatic environments in which they are found. Terrestrial materials, like soils, leaves, and bits of decomposing botanical materials become an important component of the substrate, and add to the biological function and diversity.

Now, there is a whole science around aquatic substrates and their morphology, formation, and accumulation- I don't pretend to know an iota about it other than skimming Marine biology/hydrology books and papers from time to time. However, merely exploring the information available on the tropical aquatic habitats we love so much- even just looking long and hard at some good underwater pics of them- can give us some good ideas!

How do these materials find their way into aquatic ecosystems?

In some areas- particularly streams which run through rain forests and such, the substrates are often simply a soil of some sort. A finer, darker-colored sediment or soil is not uncommon. These materials can profoundly influence water chemistry, based on the ionic, mineral, and physical concentrations of materials that are dissolved into the water. And it varies based on water velocities and such.

Meandering lowland rivers maintain their sediment loads by continually re-suspending and depositing materials within their channels- a key point when we consider how these materials arrive-and stay- in the aquatic ecosystems.

Okay, I could go on and on with my amateur, highly un-scientific review of substrates in Amazonia and elsewhere, but you get the point: There is more to the substrate materials found in Nature than just "sand." That's the biggest takeaway here. So, as hobbyists, we have more options and inspiration to to draw on to create more compelling substrates in our aquariums!

We talk about the concept of "substrate enhancement" or "enrichment" a lot in the context of botanicals (we tend to use the two terms interchangeably) around here. Now, we're not talking about "enrichment" in the same context as say, planted aquarium people, with materials put into the substrate specifically for the benefit of plants.

Rather, "enrichment" in our context refers to the addition of botanical materials for creating a more natural-appearing, natural-functioning substrate- one which provides a haven for microbial life, as well as for small crustaceans, biofilms, and even algae, to serve as a foraging area for our fishes and invertebrates. There is something oddly compelling to me when I look at both aquariums and natural biotopes with a diverse, interesting bottom structure.

There are a lot of interesting materials which you can experiment with in your substrate. Let's look at a few.

Leaves and botanical materials: You can utilize a bed of leaves on the bottom of your aquarium to not only form a substrate which will impart tannins and humic substances into the water- it will provide "fuel" for an entire population of microorganisms which drive the biological processes in our aquariums. As they decompose, leaves serve as food for this microcosm.

We've talked so much about leaf litter in the wild and in the aquarium over the years that it almost barely warrants discussion here; suffice it to say that utilizing leaf litter in our tanks is a fundamental part of the botanical-style aquarium approach.

Interesting semi-anecdotal observations from my friends in the know suggest that the biofilms for decaying leaves form a valuable secondary food for the fry of fishes such as Discus, Uaru, (after they’re done feeding on their parent’s exuded slime coat) and even Loricariid catfishes. And of course, all sorts of other grazing fishes, like some characins and even Cyprinids, can derive some nutrition from the fungi, bacteria, and small crustaceans which live in, on, and among the leaf litter bed.

I’ve seen fishes such as Pencilfish (specifically, but not limited to N. marginatus ) spend large amounts of time during the day picking at leaf litter and the surfaces of decomposing botanicals, and maintaining girth during periods when I’ve been traveling or what not, which leads me to believe they are deriving at least part of their nutrition from the leaf litter/botanical bed in the aquarium.

As I've obsessively reported to you, I set up a small tank in my office awhile back for the sole purpose of doing damn near the entire substrate with leaves and twigs- sort of like in Nature. There was less than approximately 0.25"/0.635cm of sand in there. I went from throwing in wood to make it look "cool", to ultimately yanking out everything but the leaves and just a few small twigs on the bottom. That's the whole "scape." What we in the reef world call a "no scape."

Leaves and a shoal of Parachierdon simulans.

Nothing else.

And the interesting thing about that tank is that it was one of the most chemically stable, low-maintenance tanks I've ever worked with. It held a TDS of 12 and a pH of 6.2 pretty much from day one of it's operation. It cycled in about 5-6 days. Ammonia was barely detectible. Nitrite peaked at about 0.25mg/L in approximately 3 days.

Now, the point is not to drop a big old "humble brag" about some cool tank I started. The point is to show what I think is an interesting "thing" I've noticed about this type of"leaf litter only" tank. Stability and ease of function.

I was quite astounded how a new tank could go from dry to "broken in" in a week or so. And not just "broken in" (ie; "cycled")- like, stable. I don't usually do this, but I tested all basic parameters every day for the first 3 weeks of the tank's existence, just to kind of see what would happen.

The "power" of these botanical-derived substrates comes from the organisms which reside in- and even consume- them!

Twigs: Have you ever thought of creating a substrate for your aquarium consisting entirely of twigs? I think that twigs are truly amazing materials to use for substrates for a variety of reasons. First, a "structure" of twigs offers an interesting "physical" structure within the aquarium, which provides bottom-dwelling fishes with a place to hide, forage, and spawn.

Second, like any other botanical material, twigs will impart tannins and humic substances into the water columns they decompose. One might call them an "active" substrate material!

Finally, twigs, by virtue of their abundant surface area, will provide a colonization substrate for fungi, biofilms, and other microbial growth. This is a huge thing and shouldn't be overlooked. In fact, the interstitial spaces created when you sort of "stack" (okay...more like, "toss") the twigs into place are really useful for all sorts of fishes and shrimp to inhabit!

Let's circle back again to some familiar themes.

We talk about the concept of "substrate enhancement" or "enrichment" a lot in the context of aquatic botanicals (we tend to use the two terms interchangeably). Again, we're not talking about "enrichment" in the same context as say, planted aquarium guys, with materials put into the substrate specifically for the benefit of plants. However, the addition of botanical and other materials CAN create a sort of organic "mulch" which benefits many aquatic plants!

Rather, "enrichment" in our context refers to the addition of botanical materials for creating a more natural-appearing, natural-functioning substrate- one which provides a haven for microbial life, as well as for small crustaceans, biofilms, and even algae, to serve as a foraging area for our fishes and invertebrates.

We've found over the years of playing with botanical materials that substrates can be really dynamic places, and benefit from the addition of leaves and other materials. For many years, substrates in aquarium were really just sands and gravels. With the popularity of planted aquariums, new materials, like soils and mineral additives, entered into the fray. With the botanical-style aquarium starting to gain in popularity, now you're seeing larger materials added on and in the substrate...for different reasons of course.

We've been offering various materials to add into your substrate for almost 5 years now...Stuff like the coconut-based "Fundo Tropical" and the smaller "Substrate Fino", or Coco Palm Bracts- materials which, in both look and feel- are far different from what is typically utilized in aquarium work.

You might say that, to some extent, an "enriched" or "enhanced" substrate functions as sort of a "refugium", providing protection for many beneficial creatures to grow and multiply. Many offer services like nutrient processing and scavenging of uneaten food, making this not only an aesthetically pleasing area within your aquarium- but a highly functional one, as well!

Now, there is way more than I could touch on in this brief blog, but the idea of "alternative substrate materials" is something that we should be exploring a lot in our botanical-style aquariums. I hope to talk about this a lot more in coming installments of "The Tint", and I'm sure we'll be discussing ideas for alternative substrates elsewhere as well!

Stay creative. Stay curious. Stay excited. Stay diligent. Stay observant...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

What's so funny about peace, love and tinted water? The "mental shifts" we make...

We ask everyone who plays in the botanical-style world to be open-minded about accepting all sorts of unusual things. Things which, in our previous hobby experience freaked us out to no end.

It's a lot to ask, I'm sure. I mean, the idea of embracing an aquarium which looks and functions in a manner which is essentially contrary to virtually everything you've been brought up to believe in the hobby requires a certain leap of faith, doesn't it?

Yeah, it does.

And we- and Nature- appreciate you making the leap!

What are some of the mental shifts we've asked you to make?

Tinted Water: Okay, this isn't the most difficult demand that this hobby specialty makes of you. However, it's certainly the most immediately obvious one, isn't it?

The color is, as you know, a product of tannins and other substances leaching into the water from wood, soils, and botanicals. It's actually one of the most natural-looking water conditions around, as water influenced by soils, woods, leaves, etc. is ubiquitous around the world. Other than having that undeniable color, there is little that differentiates this water visually from so-called "crystal clear" water to the naked eye.

Of course, the water may have a lower pH and general hardness, but these factors have no bearing on the color of the water. It's entirely possible to have deeply tinted water and a high pH and hardness. Yes, it's about aesthetics...but it's also about the beautiful function of botanical materials and soils which influence the chemical environment of the aquarium- just like they do in Nature.

Biofilms: Of all the mental shifts asked of those who play in this arena, accepting the formation of biofilms is likely the biggest "ask" of all! Their very appearance- although indicative of a properly functioning ecosystem, simply looks like something that we as hobbyists should loathe.

Biofilms form when bacteria adhere to surfaces in some form of watery environment and begin to excrete a slimy, gluelike substance, consisting of sugars and other substances, that can stick to all kinds of materials, such as- well- in our case, botanicals.

And we could go on and on all day telling you that this is a completely natural occurrence; bacteria and other microorganisms taking advantage of a perfect substrate upon which to grow and reproduce, just like in the wild. Freshly added botanicals offer a "mother load"of organic material for these biofilms to propagate, and that's occasionally what happens - just like in Nature.

Yet it does, so we will! :)

Biofilms on decomposing leaves are pretty much the foundation for the food webs in rivers and streams throughout the world. They are of fundamental importance to aquatic life.

Fungal Growth: Another one of those life forms which is a fundamental part of the botanical-style aquarium’s “behavior”, fungal growths perform vital and highly beneficial functions within aquatic ecosystems.

Fungi tend to colonize wood and botanical materials, because they offer them a lot of surface area to thrive and live out their life cycle. And cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin- the major components of wood and botanical materials- are degraded by fungi which posses enzymes that can digest these materials!

Fungi are regarded by biologists to be the dominant organisms associated with decaying leaves in streams, so this gives you some idea as to why we see them in our aquariums, right?

Yup.

In aquarium work, we see fungal colonization on wood and leaves all the time. Most hobbyists will look on in sheer horror if they saw this extensive amount of fungal growth on their carefully selected, artistically arranged wood pieces! Yet, it's one of the most common, elegant, and beneficial processes that occurs in Nature!

Decomposition: Another one of the things that we've previously loathed based simply on its outward appearance, the process of decomposition is an amazing process by which Nature processes materials for use by the greater ecosystem.

It's the first part of the recycling of nutrients that were used by the plant from which the botanical material came from. When a botanical decays, it is broken down and converted into more simple organic forms, which become food for all kinds of organisms at the base of the ecosystem.

Six primary breakdown products are considered in the decomposition process: bacterial, fungal and shredder biomass; dissolved organic matter; fine-particulate organic matter; and inorganic mineralization products such as CO2, NH4+ and PO43-. In tropical streams, a high decomposition rate has been related to high fungal activity...they accomplish a LOT!

Of all the processes which we foster and observe in our botanical-style aquariums, none is more fundamental than the decomposition of the leaves, seed pods, and bark that we play with in our practice. And the most amazing thing is that the very processes that we see in our aquariums have been occurring in Nature for eons.

Detritus: The definition of this stuff, as accepted in the aquarium hobby, is kind of sketchy in this regard; not flattering at the very least:

"detritus is dead particulate organic matter. It typically includes the bodies or fragments of dead organisms, as well as fecal material. Detritus is typically colonized by communities of microorganisms which act to decompose or remineralize the material." (Source: The Aquarium Wiki)

Yeah, doesn't sound great.

But really, IS it that bad?

I mean, even in the above the definition, there is the part about being "colonized by communities of microorganisms which act to decompose or remineralize..."

It's being processed. Utilized. What do these microorganisms do? They eat it...They render it inert. And in the process, they contribute to the biological diversity and arguably even the stability of the system. Some of them are utilized as food by other creatures. Important in a closed system, I should think.

This is really important. It's part of the biological "operating system" of our aquariums.

So....IS detritus a "nutrient trap?"

Or is it a place for fishes to forage among? A place for biodiversity to arise.

A place for larval fishes to seek refuge and sustenance in? Kind of like they do in Nature, and have done so for eons?

Yes, I know, we're talking about a closed ecosystem here, which doesn't have all of the millions of minute inputs and exports and nuances that Nature does, but structurally and functionally, we have some of them at the highest levels (ie; water going in and coming out, food sources being added, stuff being exported, etc.).

There is so much more to this stuff than to simply buy in unflinchingly to overly-generalized statements like, "detritus is bad."

Is there ever a situation, a place, or a circumstance where leaving the detritus "in play" is actually a benefit, as opposed to a problem?

I think so.

Think about the potential benefits of allowing some of this stuff to remain.

Think about the organisms which feed upon it, their impact on the water quality, and on the organisms which fed on them. Then, think about the fishes and how they utilize not only the material itself, but the organisms which consume it.

Consider its role in the overall ecosystem...

And that's another shift we ask you to make...To consider your aquarium as an ecosystem, subject to the same influences- and challenges- as Nature.

I'm utterly fascinated by the idea of an aquarium as a habitat, which contains a wide variety of plants and animals. Not only do these life forms constitute a source of ecological balance and environmental stability- they are a source of supplemental food for the resident fishes.

The point is, our aquariums, much like the wild habitats we strive to replicate, are constantly evolving, accumulating new materials, and creating new physical habitats for fishes to forage among. New food sources and chemical/energy inputs are important to the biological diversity and continuity of the flooded forests and streams of the tropics, and they play a similar role in our aquariums.

This is one of the most interesting aspects of a botanical-style aquarium: We have the opportunity to create an aquatic microcosm which provides not only unique aesthetics- it provides some supplemental nutritional value for our fishes, and perhaps most important- nutrient processing- a self-generating population of creatures that compliment, indeed, create the biodiversity in our systems on a more-or-less continuous basis.

This, to me, is extremely exciting.

And it's really as much of a mental shift as it is anything else- like so much of what we do with botanical-style aquarium systems. The willingness of us to really look to Nature as more than just an inspiration for making cool-looking aquariums. Rather, an approach which understands that our botanical-style aquariums require us to step back and observe what happens in wild aquatic habitats, and realizing that the same processes occur in our aquariums.

Natural materials, submerged in water, processed by a huge diversity of organisms, working together. A microbiome. A tiny, functional ecosystem. All of these things are beautiful, natural, and incredibly important in our closed systems- if we give them a chance.

It seems that we spend so much time resisting the appearance of some of this stuff and focusing on it's removal, that it's not given a chance to present its "good side" -which there most definitely is. And, the fact is that these life forms and processes appear in wild environments for a reason.

The botanical-style aquarium that we play with is perhaps the first of it's kind in the hobby to really say, "Hey, this is just like Nature! It's not that bad!" And to make us think, "Perhaps there is a benefit to all of this."

There is.

Aquarium hobbyists have (by and large) collectively spent the better part of the century trying to create "workarounds" or "hacks", or to work on ways to circumvent what we perceive as "unattractive", "uninteresting", or "detrimental." And I have a theory that many of these things- these processes- that we try to "edit", "polish", or skip altogether, are often the most important and foundational aspects of botanical-style aquarium keeping!

It's why we literally pound it into your head over and over here that you not only shouldn't try to circumvent these processes and occurrences- you should embrace them and attempt to understand exactly what they mean for the fishes that we keep. They're a key part of the functionality.

Look to Nature. And be bold.

Stay open minded. Stay observant. Stay creative. Stay studious. Stay excited...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

The sheer audacity of it all...Good, bad, and otherwise.

We keep live tropical fishes in glass boxes filled with water.

Isn't that crazy?

I mean, ensconced in their little homes, our fishes live out their entire lives in the worlds that we construct and maintain for them. It's not only an awe-inspiring concept when you think about it- it's an awesome responsibility that we as aquarists take on.

There is something remarkable about planning, constructing, and managing an aquarium intended to replicate the function of Nature.

Many of us consider this practice- this journey- to be an almost solemn responsibility to our animals.

It takes a certain audacity to do this, doesn't it?

Even though we've been playing with this stuff commercially for about 5 years, as a hobbyist, I've been dabbling with blackwater/botanical-style aquariums for around 19 years...and the hobby itself has been "doing" blackwater tanks for many years. Like, generations. So, it's weird when people within the hobby use the sharing of our experience in this area as an occasion to make strange insinuations about myself, Tannin, our the community which has flourished around it. Periodically, someone will "remind us" that we "didn't invent this idea.." As if we ever claimed that we did! Who would make claims like that?

Nature "invented" this "idea."

Gotta love our hobby culture, huh? How do ideas like that get started?

Yeah, Nature was the "inventor." We- all of us- just play with Her. We follow Her lead. We absorb Her inspiration.

We dream in water.

Now, I will claim that- perhaps- we "elevated" the art and science just a little bit; perhaps brought it out of the "darkness" (literally), but we did not invent it.

Regardless of who pioneered blackwater/botanical-style aquariums and when, there are still lots of questions surrounding this stuff. There are still many unknowns, misconceptions, misinformation, and perhaps even a bit of confusion...

We're doing our best to dispel many of these misconceptions, yet it takes time (and hundreds of blog posts and podcasts!) and a global community of active hobbyists to really get the word out more that this is cool stuff- and that there is no single "recipe" for success with botanical-style aquairums. It's good to see many hobbyists, authors, influencers, and YouTube-ers sharing their personal experiences and ideas in this sector.

If we as humans have the sheer audacity to try to capture a part of Nature in our home aquariums, it's important that we understand how She works with the materials and ideas that we incorporate in the process.

As we know, natural botanical materials not only offer very unique natural aesthetics- they offer literal "enrichment" of the aquatic habitat through their release of tannins, humic acids, vitamins, etc. as they decompose- just as they do in Nature.

This is a pretty amazing thing. And it's something that we can embrace.

Much like flowers in a garden, leaves will have a period of time where they are in all their glory, followed by the gradual, inevitable encroachment of biological decay. At this phase, you may opt to leave them in the aquarium to enrich the environment further (providing food for fungi, bacteria, and other fauna), and offer a different aesthetic, or you can remove and replace them with fresh leaves and botanicals.

This very much replicates the process which occur in nature, doesn't it?

With the publishing of photos and videos of leaf-influenced aquariums in the past few years, there has been much interest- and more questions by hobbyists who have not really considered incorporating these items in an aquarium before. This is really cool, because new people with new ideas and approaches are actively experimenting. And, perhaps most important of all- we're looking at Nature as never before. We're celebrating the real diversity and appearance of natural habitats as they really are...

Not everyone likes this nor appreciates it. Or understands it. And that's perfectly fine. Not everyone finds brown water, decomposing leaves, biofilms, and detritus beautiful. A lot of aquarists just sort of shrug. Some even laugh. Some love to criticize.

It's not the "best" way to run a tank. Just "a way."

Some want "rules." Order. Guidelines from experts.

We at Tannin offer no "rules."

We can only offer an assessment of what Nature does to an aquarium when it's set up a certain way. We can only point out the way Nature looks and study how it functions, and perhaps offer some hints on how to embrace the processes which it utilizes.

There are no real "rules" when creating a blackwater/botanical-style aquarium, other than the biological aspects of decomposition and water chemistry, which are the real factors that dictate just how your aquarium microcosm will ultimately evolve.

The initial skepticism and resistance to the idea of an aquarium filled with biofilms, decomposition, and tinted water has given way to enormous creativity and discovery. Our community has (rather easily, I might add!) accepted the idea that Nature will follow a certain "path"- parts of which are aesthetically different than anything we've allowed to occur in our tanks before- and rather than attempting to mitigate, edit, or thwart it, we're celebrating it!