- Continue Shopping

- Your Cart is Empty

Oak: The "one-stop-shop!"

I'm often asked what my fave all-time botanical is for our aquariums.

Now, you'd think that I'd likely reference some exotic seed pod, leaf, or root, right? The reality is that my all-time favorite botanical to use in our botanical-method tanks is oak twigs, branches and leaves.

Yeah, the humble, decidedly "non-exotic" Oak tree is sort of a "one-stop-shop" for the botanical method aquarium enthusiast.

Why Oak?

These are some of the best materials to use because, IMHO, they not only contribute to the physical structure of your tank- they also impact the ecology and water chemistry in significant ways as well. They are all surprisingly durable, long-lasting, and aesthetically pleasing, too!

Oak twigs and branches absorb water and begin to impart tannins, lignins, and other compounds into the water. Not only will you notice a visible "tint" to the water when you utilize oak branches and twigs, you'll have a perfect "substrate" upon which biofilms and fungal growths can colonize.

The other beauty of oak is that you can collect these materials yourself, if you have a source of them nearby!

Oak belongs to the genus Quercus, of the beech family (Fagaceae), with almost 500 species. A large and diverse genus, which, according to Wikipedia "is native to the Northern Hemisphere, and includes deciduous and evergreen species extending from cool temperate to tropical latitudes in the Americas, Asia, Europe, and North Africa. North America has the largest number of oak species, with approximately 160 species in Mexico of which 109 are endemic and about 90 in the United States. The second greatest area of oak diversity is China, with approximately 100 species."

So, in plain English, Oak is found across a broad swath of the planet, making it one of the most readily available and accessible botanical resources for hobbyists worldwide. The fact that you can collect them yourself if you can source them is a huge plus!

(Image by Jurgen Eissink -CC-by S.A. 4.0 )

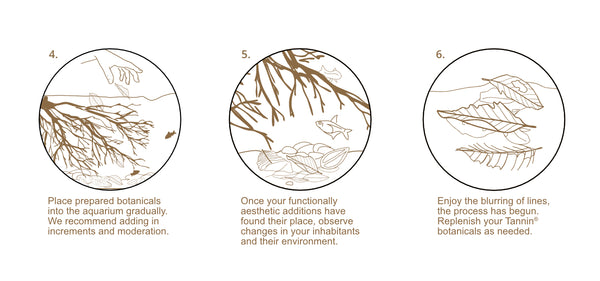

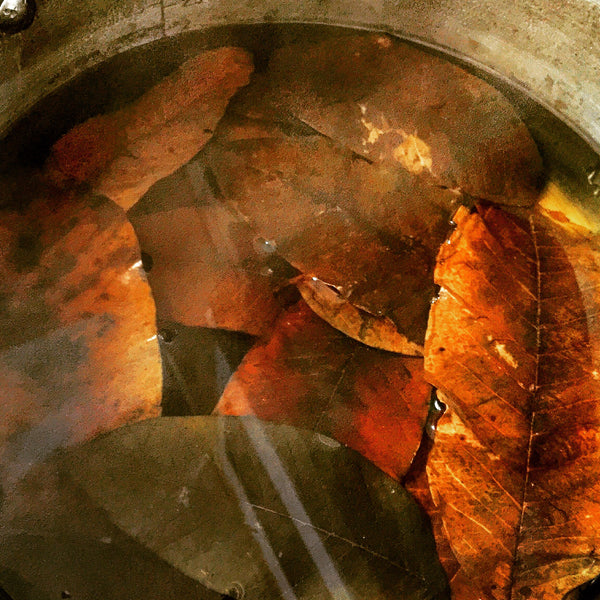

Now, like any botanical, sourcing and preparation are important considerations with oak-derived materials. If you collect them yourself, or purchase them from a well-regarded vendor like, I dunno- say...Tannin Aquatics- you're going to be working with materials that are essentially clean and non-polluted. Which means that preparation is going to consist of steeping or boiling leaves, and steeping or (if you have a big enough pot or vat) boiling of twigs/branches.

Yeah, let's digress a bit...The old question about why we prepare stuff comes back yet again:

You see it on our packaging, hear it discussed on "The Tint" podcast, and read about it in articles we publish here and elsewhere. Yet, there appears to be some confusion about what exactly we mean by "preparation."

Yeah, it's not a secret that, before you throw those seed pods and leaves into your aquarium, you need to do some preparation.

Why?

And why are we talking about this again?

Well, seriously, I still receive about 3-4 emails every single week from customers of ours (and from others, apparently!) asking what to do with botanicals after they receive them...So, it's obvious to me that some people just aren't seeing this stuff, hearing it, reading our instructional cards, social media posts, etc., or not getting advice from the people they purchased their leaves, or whatever from. (Isn't EBay great! What a resource for serious hobbyists!)

Really?

Yup.

I know, it's starting to sound a bit repetitive...

However, with the world botanical-style aquariums growing at an exponential rate, and more and more hobbyists entering into the fray- many of whom are enamored by the beautiful aesthetics of these tanks, it's important-well, actually essential- to revisit this stuff again and again.

And really, because most of the new vendors into our market space simply appropriate much of the information we put out to help the community, and use it to push their products, let's at least give those lazy-ass motherf---ers something useful to share (and since they're not bothering to provide this information, themselves...)!

Okay, mini-hate-rant over. For now.

"So, you're really into boiling and steeping botanical, huh?

Yes. I am. That's my thing.

"Why do you do that?"

Consider that boiling water is used as a method of making water potable by killing microbes that may be present. Most nasty microbes essentially "check out" at temperatures greater than 60 °C (140 °F). For a high percentage of microbes, if water is maintained at 70 °C (158 °F) for ten minutes, many organisms are killed, but some are more resistant to heat and require one minute at the boiling point of water. (FYI the boiling point of water is 100 °C, or 212 °F)...But for the most part, most of the nasty bacteria that we don't want in either our tanks or our stomachs are eliminated by this simple process.

So, wouldn't it make sense to boil, or at least steep, our botanicals before we dump them into our aquariums?

Yeah, it would.

Ten minutes of boiling is "golden" to assure a "good kill", IMHO. Of course, we boil for other reasons, too-as we'll touch on in a bit.

The most important reason that we boil botanicals is to kill any possible microorganisms which might be present on them. Leaves, seed pods, etc. have been exposed to rain and dust and all sorts of things in the natural environment which, in the confines of an aquarium, could introduce unwanted organisms and contribute to the degradation of the water quality.

And, the surfaces and textures of many botanical items, such as leaves and seed pods lend themselves to retaining dirt, soot, dust, and other atmospheric pollutants that, although quite likely harmless in the grand scheme of things, are not stuff you want to start our with in your tank!

So, we give all of our botanicals a good rinse with fresh water.

Then we boil them.

Boiling also serves to soften botanicals. This is important to do for a number of reasons...

Well, the most obvious to us is thats it helps saturate the tissues of the botanicals and make them sink. I mean, who wants a bunch of floating seed pods and leaves in their aquairum? Wait, don't tempt me here...

If you remember your high school Botany (I actually do!), leaves, for example, are surprisingly complex structures, with multiple layers designed to reject pollutants, facilitate gas exchange, drive photosynthesis, and store sugars for the benefit of the plant on which they're found. As such, it's important to get them to release some of the materials which might be bund up in the epidermis (outer layers) of the leaf. As we get deeper into the structure of a leaf, we find the mesophyll, a layer of tissue in which much of photosynthesis takes place.

We use only dried leaves in our botanical style aquariums, because these leaves from deciduous trees, which naturally fall off the trees in seasons of inclement weather, have lost most of their chlorophyll and sugars contained within the leaf structures. This is important, because having these compounds present, as in living leaves, contributes excessively to the bioload of the aquarium when submerged...

Personally, I feel that we have enough bioload going into our tanks, so why add to it by using freshly-fallen leaves with their sugars and such still largely present, right? I mean, it's definitely something worth experimenting with in controlled circumstances, but for most of us botanical method aquarium geeks, naturally fallen, dried leaves are the way to go.

I'm still going to recommend that, like I do- that you embrace a preparation process for every botanical item that you add to your aquariums.

Now, with twigs and branches, the idea of practicality comes in. Most of us simply don't have freaking cauldron or big-ass kettle- let alone, a "stove" large enough upon which to boil a bunch of branches, right?

So, compromise is in order.

Soaking is not a bad thing.

I've touched on the idea of "in situ" preparation of wood, and it really does make sense with oak branches (largely because of the size issue)- and consider this:

It's pretty obvious that at least part of the reason we see a burst of new algae growth and biofilm in wood recently added to an aquarium is that there is so much "stuff" bound up in it. "Organics", like sugars, lignins, and compounds found in soils, etc. Algal and fungal spores can literally "bloom" during the initial period after submersion. It's exactly what happens in the wild aquatic habitats of the world when tree trunks and branches are covered by water.

I get it- a lot of hobbyists simply don't want to see this stuff in their display tank.

On the other hand, the adventurous aquarist in me can't help but wonder if we should just give the wood a thorough washing, and let this whole process play out in the aquarium, to foster this amazing biodiversity within the aquarium itself.

Again, this is an example of setting up an aquarium from the start to replicate both the form and function of Nature.

Why NOT do this? Especially with "self-collected" stuff like oak branches.

What would the "downsides" be? I've done this many times with no issues. However, the experience IS a bit different.

It's starts with what you see.

Yeah, you'll see a lot more biofilm, fungal growth, detritus, and perhaps even slightly hazy water. You'll have to carefully monitor the nitrogen cycle, and manage nutrient accumulations with good husbandry...

You'll have to employ a lot of patience, and yeah, I'd recommend testing during the "break-in"process. Testing for what? Well, I'd likely do ammonia and nitrite, for starters. "Have you done all of this testing when you tried this, Scott?"

Not always, I admit. Why? For one thing , it's because I'm in no rush to add fishes to brand-new tanks. Because I let my tanks develop biologically for a long time before I add them. I did out of sheer curiosity, of course! And the "cycle"time was really nothing extraordinary at all.

Really, the biggest difference between this "in-tank-curing" and using an external container was that any of the stuff that emerged from the wood itself would leach into, and "accumulate" in the display tank, and impact the water appearance, and chemistry. Although I admit, I didn't notice a significant difference in nitrate or even phosphate in new tanks where the "curing" process was undertaken internally.

Remember, I'm a water exchange fanatic; I perform 10% water exchanges in every tank I maintain- every week, without fail. So there was some dilution of whatever organics were found in the water.

The biggest difference determined by testing was often TDS. And of course, because TDS represents the "total concentration of dissolved substances" in water it can include both inorganic salts, as well as a small amount of organic matter. To me, "TDS" is always a bit of a vague thing; I mean, it can be so many different things. Regardless, when I cured "in situ", TDS readings were higher than in tanks where this process wasn't employed.

Do some of the other materials leached out of wood have implications for the healthy break-in and operation of your aquarium? Can you even test for everything that leaches out of newly submerged wood, other than simply labeling these compounds as "organics?"

Likely NOT, in the hobby world.

Well, lignin is one substance that you might find leaching out of wood. And there are actually lignin test kits out there for scientific work; I suppose it would be interesting and informative to test for them to see what the concentration was, although I'm not really sure what function it would perform, other than just kind of "knowing."

Just like with testing for tannins, Interpreting what is "baseline" or even "okay" for lignin is something we have never really done in the hobby, right? Another supposition would be that lignin concentration might be different in a filtered aquarium than it would be in some big container of water without a filter that you might cure wood in.

The point is, there are some things that we just don't know. We assume. I Mean, whenever we "cure" wood externally, we almost always see lots of that yucky biofilm and fungal growth on the surface tissues. That's "par for the course" when terrestrial materials are submerged. The real issue that makes "in situ" curing a bit unusual is the possible "gross pollutants" that may leach out of the wood. I suppose that would be stuff like dust, dirt, maybe some small amounts of sap, etc., bound up in or on the surface tissues of the wood.

I did a lot of research on this in the online forums, articles, etc, and the reasons why it's recommended that wood be "cured" outside of the display tank are always listed as (in no particular order):"to leach out impurities","to leach out tannins", to "let the fungal growth subside", and "to waterlog and sink."

Now, other than "waterlog and sink" process, which you can accomplish in the display tank by simply placing a few rocks on the wood, IMHO none of the other reasons given for external curing of wood are really "non-starters" here.

It's occasionally stated that boiling wood or extended soaking helps eliminate potential parasites that might be present in/on the wood. I'd hazard a guess that most wood used in aquariums doesn't have significant populations of parasites that could harm fishes, either. And again, even if there are such parasites present, if you're taking your time to add fishes (essentially keeping your tank "fallow" for a period of time) you're essentially denying any parasites that are present their "hosts", right?

Am I missing something here?

I don't really think so. It's just that I don't see the "stuff" that happens during the curing process as a problem.

"In situ" curing isn't a perfect, guaranteed route to accomplishing everything you want to easily, but it works. And the process and its impacts on the ecology of your aquarium is not all that different than what occurs in Nature, when you think about it.

In Nature, it is not uncommon at all for small (and large) trees to fall in the rain forest, with punishing rain and saturated ground conspiring to easily knock over anything that's not firmly rooted!

When these trees fall over, they often fall into small streams, or in the case of the varzea or igapo environments in The Amazon ( the ones that I'm totally obsessed with), they fall and are ultimately submerged in the inundated forest floor when the waters return.

And of course, they immediately impact their (now) aquatic environment, fulfilling several functions.

Fallen trees provide a physical barrier or separation from currents, perhaps creating a little "dam", which accumulates leaves, sediments, and detritus- all important as food sources to a huge number of aquatic organisms.

They also provide a "substrate" for algae and biofilms to multiply on, and providing places for fishes forage among, and hide in. Many fishes, like small cichlids, will reproduce and raise their fry among these fallen tree trunks.

An entire community of aquatic life forms uses the fallen tree for many purposes. And the tree trunks, branches, and other parts of the tree will last for many years, fulfilling this important role in the aquatic ecosystems they now reside in each time the waters return.

So, all of this talk of prep is important...but the idea of "prep" can encompass many things. It's one of those things that we as hobbysits know to do, but we always sort of second guess ourselves about HOW to do it.

The fact is, we need to embrace SOME sort of preparation protocol for any natural materials that we add to our aquariums.

Okay, that was a huge detour, but a necessary one.

I love creating tanks in which the "hardscape" consists mainly of twigs and small branches. Oak is the perfect "provider" of these materials, BTW. It keeps things simple and easy.

The beautiful thing about this idea is that you don't necessarily have to use 12 different varieties of branches and such to create a remarkably complex and interesting scape. Just oak!

Oak twigs and branches, and oak leaves are pretty much all you need for a sweet botanical-method aquarium, IMHO.

It's not just about then aesthetic, of course.

The idea is that you're creating a matrix of these materials to impart a very natural and interesting look to the aquarium. These aggregations provide fishes with hiding places, foraging areas, and spawning sites, just like they do in Nature.

We're talking mainly about twigs and roots...nto big branches here.

Now, such root/branch tangles DO take up some physical space in the confines of the aquarium, and you need to take this into account when stocking, equipping, and maintaining such systems. Access, water capacity, and filter intakes/outputs need to be considered when you move in a project like this...but that's half the fun, anyways- right?

At the end of the day, the use of twigs, roots, and branches, the organisms which take advantage of them is one of the most stunning aspects of Nature that we can see in our own aquariums, provided we don't "edit" them out of our tanks.

Like any dynamic habitat, the "twig and root" microhabitat relies on a variety of organisms to do the job of processing nutrients. A diverse assemblage of organisms dwelling in this layer, ranging from bacteria to fungi, to worms and small crustaceans- comprise what we call the "infauna." Essentially, the infauna is a collective of organisms which do most of the work in keeping a botanical-method aquarium functional and healthy.

Be kind to these organisms, and they'll no doubt be kind to you, too.

And of course, this habitat is perfectly analogous to what you see in Nature, isn't it?

In Nature, we see leaves and other materials accumulate in these root tangles and aggregations of fallen branches, so recreating this in nature is kind of a "no brainer!"

When assembled in conjunction with a nice aggregation of leaves, this configuration provides a remarkably interesting aquarium with a different sort of aesthetic.

Looks, function, versatility...That's what makes Oak literally a "one-stop" shop for your botanical-method aquarium needs!

Stay creative. Stay inspired. Stay engaged. Stay observant...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

4 Responses

John Fraley

Yeah, I’m hooked. Your writing mirrors what it’s like inside my head. The detours and rants are perfectly placed (at least for me). I’ve read other writers and by the time I’m done, I have 15 other tabs open for my detours. Nope, you did it for me. Thanks

Russell Sniady

Yours is the most practical, informative, and fun site I’ve seen, and I’ve seen many. Hat’s off!

Fishyfreeonz

Inspiring as always! Now I want to do a shallow tank!

X

Man, are you still alive?

Scott Fellman

Author