- Continue Shopping

- Your Cart is Empty

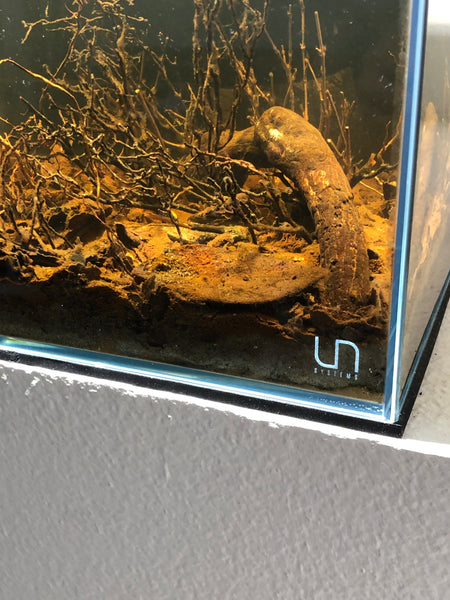

The game. Revisted.

When it cones to our hobby work, I believe that we have two choices:

We can resist Nature’s advances, and attempt to circumvent or thwart Her processes of decomposition, growth, and evolution. We can scrape away unsightly biofilms, we can remove detritus and algae. We can trim our plants to look neat and orderly.

Or, we can accept Her seemingly random, relentless march.

We can make a conscious decision to embrace the biofilms, fungal growth, decomposing leaves, and tinted water. We start this by accepting the look, and continue from there.

It should come as no surprise that botanical method aquariums simply appear unusual. We fans celebrate aquariums modeled after Nature as it really is, in form and function; filled with randomness, intricacy and yeah, even a bit of mystery.

It's the "game."

That may sound dramatic, but those of us who play with this stuff have come to realize that botanical method aquariums simply have different "operating parameters" compared to pretty much any other type of system you’ve ever kept. Like any aquarium, you need to understand, appreciate, and enjoy the characteristics, phases, and nuances of this type of approach.

The sheer variety and the appearance of botanical materials is astounding.

Beyond aesthetics

One of the most important things you need to do when contemplating the creation of a botanical method aquarium is to adopt some different ways of looking at things...we call them mental shifts.

The biggest mental shift required is the understanding that botanical materials break down as they impart tannins and other substances into the water. A well-manicured botanical method aquarium will be reshaped by Nature as the leaves, seed pods, and other botanical materials are subject to biological degradation.

This is strange for us as hobbyists, who live to control everything- yet it’s something that our fishes are completely familiar with. They’ve adapted over eons to co-exist with and utilize these naturally-occurring materials as hiding places, areas to forage, and sites to spawn, as a part of their daily existence.

Thought about from such a standpoint, you can contemplate a more basic question about our hobby: “What is the purpose of an 'aquascape' in the aquarium, besides just aesthetics?”

Well, it’s to provide fishes with a comfortable environment that makes them feel at home, right? The botanical-method aquarium embraces this idea thoroughly on several fronts.

We call the idea "functional aesthetics."

Botanicals as "acidifiers"- The great misconception...

Many hobbyists ask us about utilizing leaves and other botanicals to lower the pH in their aquariums, and this opens up the proverbial "can of worms!"

There seems to be a fair amount of misconception about what botanicals can and cannot do to the pH of the water in your aquarium.

I field a lot of questions like, “How many leaves do I need to lower the pH and hardness in my Betta tank?” If only it were so simple! In reality, Nature offers few ‘plug and play’ solutions.

Many botanicals do release acids that can lower the pH, but only if the water already has a low enough carbonate hardness (KH). Most botanicals won’t do much to significantly reduce the pH if you start with hard, alkaline water, as the KH will act as a buffer, preventing the acids from reducing the pH.

So, the reality is that the impact of botanical materials on the pH of the aquarium in most circumstances is surprisingly minimal.

In general, it’s fairly safe to state that soft water is usually acidic, and hard water is usually alkaline. However, that's about the only generalization I'd care to make about water, lol.

And then there's an assumption many hobbyists make about the color of the water in botanical method aquariums: "If it's brown, the pH must be acidic!"

Note that the color of water — even the tint from leaves — is no real indication of pH or hardness. This is a misconception that we need to dispense with once and for all. Color is NOT AN INDICATION of the pH or hardness of water. Period. End of story!

If you really want to create soft, acidic water with botanicals, use RO or deionized water — your botanicals will have a lot more ‘play’ in terms of how they can affect the pH. Also note that, in general, botanicals alone will NOT affect KH.

All that they do bring...

One of the things you’ll experience when first adding botanicals is an initial burst of tannins, which provide a visible tint to the water. If you’re not using activated carbon or some other filtration media, this tint will be considerably more pronounced.

You might also experience some initial cloudiness. This could be dust, or lignin and other compounds released from the tissues botanicals. It may even be a bloom of bacteria and microorganisms. It usually passes quickly with minimal, if any intervention, and not everyone experiences this.

But one thing that unites owners of botanical-style aquaria is the appearance of that gooey, slimy, stringy stuff known as ‘biofilm.’

Biofilm. Even the word conjures up an image of something that you really don’t want in your tank. Something dirty, nasty, and potentially detrimental.

To be candid, the dictionary definition is not going to win over many ‘haters’: bi·o·film (noun) — a thin, slimy and usually resistant film of bacteria that adheres to a surface.

Commonly-encountered examples of biofilm include the plaque that forms on teeth, and the slime that forms on surfaces in water. But it’s not all doom and gloom.

Biofilm is a completely natural occurrence; bacteria and other microorganisms taking advantage of a perfect substrate upon which to grow and reproduce, just like they would in the wild. Freshly added botanicals offer a mother lode of organic material and surface area

for these biofilms to propagate, and that’s what happens — just like in Nature. Many fishes and shrimp will feed directly on these biofilms.

The surge of biofilm growth is typically a passing phase, and can take anywhere from a few days to several weeks before it subsides on its own. It will never fully ‘go away’ in a botanical-style tank, but then you don’t want it to. Its benefits are numerous, and to be welcomed!

Understand that biofilms are present in every aquarium, to some degree. Furthermore, they often go hand-in-hand with the appearance of fungi. Not the ones that we vilify for attacking our fish or their eggs, though. It’s easy to just heap them in with the ‘bad guys’ and the nasty implications they have.

Fungi reproduce by releasing tiny spores that then germinate on new and hospitable surfaces.

These aquatic fungi are intimately involved in the decay of wood and leafy material.

Fungus is nothing to fear here.

And, of course, when you submerge terrestrial materials in water, growths of fungi tend to arise. Anyone who has ever soaked a new piece of aquatic wood for an aquarium can attest to this.

Fungi colonize wood because it offers them a lot of surface area to thrive and live out their life cycle. And cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin — the major components of wood and botanical materials — are degraded by fungi, which possess enzymes that can digest these materials.

Fungi are regarded by biologists to be the dominant organisms associated with decaying leaves in streams. Fishes and invertebrates that live amongst and feed directly upon the fungi and decomposing leaves, and botanicals contribute to the breakdown of these materials as well. In fact, if you research gut content analysis of many species of fishes, fungi is a significant component of it!

And, for the environment in general, aquatic fungi (aka "aquatic hyphomycytes") can break down the leaf matrix and make the energy locked up inside it available to feeding animals in these habitats.

While not attractive looking to many, fungi are incredibly useful, and they play along with a surprisingly large number of aquatic life forms to create substantial food webs. Natural habitats are absolutely filled with this stuff.

Botanicals can be beautiful or ugly, pending your own views.

The long game...

Typically, botanicals will begin to soften and break down over a period of several weeks or months. As an aquarist, you have the option to leave them in as they degrade, or remove them — whatever your aesthetic sensibilities tell you to do!

Many of us leave our botanicals in our tanks until they have completely decomposed, utilizing them as almost some sort of botanical mulch, which serves as a sort of supplemental food resource, especially for fry.

So, what are the implications for managing this type of system?

Remember, you’re dealing with a tank filled with decomposing botanical materials. Good overall husbandry is necessary to keep your tank stable and healthy, and that includes regular water changes.

During water changes, I typically siphon out any debris that has moved where I don’t want it, but for the most part, I’m merely siphoning water from down low in the water column. Removing too much of the decomposing material and the resulting detritus can damage the microbiome of organisms which you're trying to foster.

What’s a good water-exchanging regimen?

I’d love to see you employ 10% per week...It’s what I’ve done for decades, and it’s served me- and my animals- very well! Regardless of how frequently you exchange your water, or how much of it you exchange- just do them consistently. And of course, as previously discussed, don't go crazy siphoning every bit of detritus out during the process.

Remember, that in an aquarium which encourages the growth of bacteria, fungi, copepods, etc., the organic material contained in detritus becomes part of the "food web." And everybody up the food chain can benefit from the stuff.

So, by going "full ham" and siphoning every last speck of detritus in your tank, you're essentially breaking this chain, and denying organisms at multiple levels the chance to benefit from it! Yeah, over-zealously siphoning this material from your tank effectively destroys an established community of microorganisms which serve to maintain high water quality in the closed environment of an aquarium!

This is a super-important point to remember!

In an ironic twist, I believe that it's far more common for those "anomalous" ammonia spikes and such that aquarists report periodically, to have their origin in over-zealous cleaning of aquariums and filter media, as opposed to the accumulation of detritus itself. So, yeah-taking out all of the "fish shit" is actually removing a complex microbiome that's keeping your tank healthy!

Even something as seemingly "mundane" as the way we maintain our botanical-method aquariums requires us to make some "mental shifts" to appreciate our methodology more thoroughly, doesn't it?

It's all part of the game...

Stay curious. Stay excited. Stay observant. Stay patient...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Scott Fellman

Author