- Continue Shopping

- Your Cart is Empty

The complexity of "nuances..."

Yeah, what we do is some strange stuff, I admit.

When I describe our little hobby niche to other hobbyists who have different areas of interest, it's interesting that I'm usually met with looks of curiosity, and the occasional inquiry as to why we do what we do with our aquariums.

I totally get it, too.

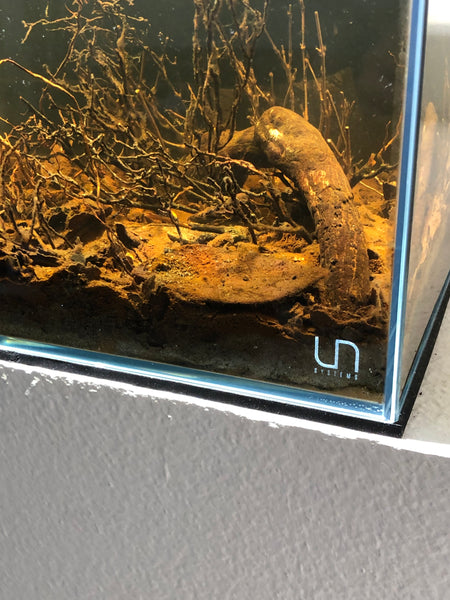

I mean, to the unindoctrinated, it does seem a bit odd that we take a "perfectly clean" aquarium and throw in a large amount of leaves and seed pods and stuff to...decompose on the bottom! This sort of goes "against the grain" of mainstream aquarium thinking!

Yet, we'd be hard-pressed to argue that the process goes against Nature!

We do add a lot of biological material to our tanks in the form of leaves and botanicals- and this is perfectly analogous to the process of allochonous input- material imported into an ecosystem from outside of it. Yeah, it's exactly what happens in the tropical streams and rivers that some of us obsess over!

There's been a fair amount of research and speculation by both scientists and hobbyists about the processes which occur when terrestrial materials like leaves and botanical items enter aquatic environments, and most of it is based upon field observations.

As hobbyists, we have a rather unique opportunity to observe firsthand the impact and affects of this material in our own aquariums! I love this aspect of our "practice", as it creates really interesting possibilities to embrace and create more naturally-functioning systems, while possibly even "validating" the field work done by scientists!

It goes without saying that there are implications for both the biology and chemistry of the aquatic habitats when leaves and other botanical materials enter them. Many of these are things that we as hobbyists also observe every day in our aquariums! We see firsthand how leaves and botanical materials impact the life of our fishes and other aquatic organisms in these closed systems.

Phenomenon such as the appearance of biofilms- long a topic that simply never came up in the hobby outside of dedicated shrimp keepers- are now simply "part of the equation" in a properly-established botanical-style aquarium. We're seeing them for the benefits they provide for our systems, rather than freaking out and panicking at their first appearance!

A lab study I came upon found out that, when leaves are saturated in water, biofilm is at it's peak when other nutrients (i.e.; nitrate, phosphate, etc.) tested at their lowest limits. This is interesting to me, because it seems that, in our botanical-style, blackwater aquariums, biofilms tend to occur early on, when one would assume that these compounds are at their highest concentrations, right? And biofilms are essentially the byproduct of bacterial colonization, meaning that there must be a lot of "food" for the bacteria at some point if there is a lot of biofilm, right?

More questions...

Does this imply that the biofilms arrive on the scene and "peak out" really quickly; an indication that there is actually less nutrient in the water? Is the nutrient bound up in the biofilms? And when our fishes and other animals consume them, does this provide a significant source of sustenance for them?

Hmm...?

Oh, and here is another interesting observation:

When leaves fall into streams, field studies have shown that their nitrogen content typically will increase. Why is this important? Scientists see this as evidence of microbial colonization, which is correlated by a measured increase in oxygen consumption. This is interesting to me, because the rare "disasters" that we see in our tanks (when we do see them, of course, which fortunately isn't very often at all)- are usually caused by the hobbyist adding a really large quantity of leaves at once, resulting in the fishes gasping at the surface- a sign of...oxygen depletion?

Makes sense, right?

As I've said repeatedly, if we don't make the effort to understand the "how's and why's", and attempt to skirt Nature's processes- she can and will kick our asses!

These are interesting clues about the process of decomposition of leaves when they enter into our aquatic ecosystems. They have implications for our use of botanicals and the way we manage our aquariums. I think that the simple fact that pH and oxygen tend to go down quickly when leaves are initially submerged in pure water during lab tests gives us an idea as to what to expect.

A lot of the initial environmental changes will happen rather rapidly, and then stabilize over time. Which of course, leads me to conclude that the development of sufficient populations of organisms to process the incoming botanical load is a critical part of the establishment of our botanical-style aquariums.

Here's a thought to consider: Inputs of terrestrial materials like leaf litter and seed pods can leach dissolved organic carbon, rich in lignin and cellulose. Factors like light, mineral hardness, and the bacterial community affect the degree to which this material is broken down into its constituent parts in this environment.

Hmm...something we've kind of known for a while, right?

So, lignin is a major component of the stuff that's leached into our aquatic environments, along with that other big "player"- tannin.

Tannins, according to chemists, are a group of astringent biomolecules that bind to and precipitate proteins and other organic compounds. They're in almost every plant around, and are thought to play a role in protecting the plants from predation and potentially aid in their growth. As you might imagine, they are super-abundant in leaves. In fact, it's thought that tannins comprise as much as 50% of the dry weight of leaves!

And of course, tannins in leaves, wood, and plant materials tend to be highly water soluble, creating our beloved blackwater as they decompose. As the tannins leach into the water, they create that transparent, yet darkly-stained water we love so much! In simplified terms, blackwater tends to occur when the rate of "carbon fixation" (photosynthesis) and its partial decay to soluble organic acids exceeds its rate of complete decay to carbon dioxide (oxidation).

And it just goes to show you that some of the things we could do in our aquariums (such as utilizing alternative substrate materials, botanicals, and perhaps even submersion-tolerant terrestrial plants) are strongly reminiscent of what happens in the wild. Sure, we typically don't maintain completely "open" systems, but I wonder just how much of the ecology of these fascinating habitats we can replicate in our tanks-and what potential benefits may be realized?

Yes, I think just having a bit more than a superficial understanding of the way botanicals and other materials interact with the aquatic environment, and how we can embrace and replicate these systems in our own aquariums. The real message here is to not be afraid of learning about seemingly complex chemical and biological nuances of blackwater systems.

As our practices evolve, it's important to take a more holistic approach. One that takes into account the ionic content of the source water, the careful addition of substrate, botanical materials, wood, and the other aspects of our unique aquariums which will make them some of the most realistic representations of Nature yet attempted.

It's going to get very fun...

Stay curious. Stay bold. Stay observant. Stay thoughtful. Stay diligent...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Scott Fellman

Author