- Continue Shopping

- Your Cart is Empty

Supplemental? Primary? Or both?

Among the many interesting ideas floating around in the botanical-style aquarium world is the idea that use of botanical materials can help provide supplemental (or primary, in some instances) food sources for our fishes. We have touched on this idea for years now, and the more we play with these aquariums, the more I'm convinced that yet another collateral benefit of them is food production.

It's hardly a stretch to propose this, right? I mean, just like in Nature, a typical botanical-style aquarium has an accumulation of organic materials, a healthy population of organisms to process them, and supports a large amount of life at many "trophic levels."

What is also studied by science, but a little more "esoteric" in the hobby (IMHO) is the use of botanical materials as supplemental food for our fishes and shrimps.

Now, it's known that most plant materials have at least some nutritional value; or rather, they contain nutrients, vitamins, etc. which are known to be beneficial to aquatic organisms. Which ones are the best for use as "supplemental foods?"

Or, are they all pretty good?

Maybe?

Well, here's the thing...

The thing that makes me curious is that most leaves and botanicals contain vitamins, amino acids, micronutrients, and other "bioavailable compounds." The real question I have is exactly how "available" they are to our fishes and shrimp from a nutritional standpoint. And how "nutrient dense" these leaves and botanicals are? Do our fishes and shrimp easily assimilate all they need in every bite, or do they have to eat tons of the stuff to derive any of nutritional benefits?

Big questions, right?

I mean, we as hobbyists sort of tend to make this (gulp) assumption that if these things are present in the botanicals, then our animals get a dose of them in every bite, right? And, it begs the question: Are they really directly consuming stuff like Casuarina cones, or feeding on something else on their surfaces (more on this later)?

I think it's "yes" on both.

And the nutrition that they derive from consuming them?

Well, that's the part where I say, I don't know for sure.

I mean, it seems to make a lot of sense to me...However, is there some definitive scientific information out there to prove this hypothesis?

A lot of the "botanicals for food thing" in the hobby (no, seriously- it's a "thing!") comes from the world of shrimp keepers. They've been touting this stuff in the hobby for a long time. A lot of it is based upon the presence of materials like leaves and such in the wild habitats where shrimp are found. I did some research online (that internet thing- I think it just might catch on...) and learned that in aquaculture of food shrimp, a tremendous variety of vegetables, fruits, etc. are utilized, and many offer good nutritional profiles for shrimp, in terms of protein, amino acids, etc.

They're all pretty good. Our friend Rachel O'Leary did a great job touching on the benefits of botanicals for shrimp in her video last Fall.

So, which one is the best? Is there one? Does it matter? In fact, other than sorting through mind-numbing numbers ( .08664, etc) on various amino acid concentrations in say, Mulberry leaves, versus say, Sugar Beets, or whatever, there are not huge differences making any one food superior to all others, at least from my very cursory, non-scientific hobby examination!

Leaves like Guava, Mulberry, etc. ARE ravenously consumed directly by shrimp and some fishes. It's known by scientific analysis that they do contain compounds like Vitamins B1, B2, B6, and Vitamin C, as well as carbohydrates, fiber, amino acids, and elements such as Magnesium, Potassium, Zinc, Iron, and Calcium...all important for many organisms, including shrimp. Guava leaves are particularly good, according to some of the materials I read. Apparently, the bulk of the nutrients they contain are more "readily available" to animals than other leaves.

Well, that's pretty important, isn't it?

I think so!

Now, it may be coincidental that these much-loved (by the shrimp, anyways) leaves happen to have such a good amount of nutritional availability, but it certainly doesn't hurt, right?

Other leaves, such as Jackfruit, contain phytonutrients, such as lignins, isoflavones, and saponins that have health benefits that are wide ranging for humans. There is some conflicting data regarding Jackfruit's alleged antifungal properties. However, the leaves are thought to exhibit a broad spectrum of antibacterial activity. In traditional medicine, these leaves are used to help heal wounds as well.

In humans.

Do these properties transfer over to our fishes and shrimp?

Here's the straight answer: We are not aware of any scientific studies that have been completed to correlate one way or another. That being said, they seem to flock to these leaves and graze on them- and on the biofilms which accumulate on their surface tissues.

The "shrimp side" of the hobby reminds me in some ways of the coral part of the reef keeping hobby where I spent considerable time (both personally and professionally) working and interacting with the community. There are some incredibly talented shrimp people out there; many doing amazing work and sharing their expertise and experience with the hobby, to everyone's benefit!

Now, there are also a lot of people out there in that world -vendors, specifically- who make some (and this is just my opinion...), well - "stretches"- about products and such, and what they can do and why they are supposedly great for shrimp. I see a lot of this in the "food" sector of that hobby specialty, where manufacturers of various foods extoll the virtues of different products and natural materials because they have certain nutritional attributes, such as vitamins and amino acids and such, valuable to human nutrition, which are also known to be beneficial to shrimp in some manner.

I mean, do shrimp really derive benefits from stuff like nettles? Well, perhaps they contain micronutrients or other compounds which are known to be beneficial to organisms. And that's fine, but where it gets a bit anecdotal, or - let's call it like I see it- "sketchy"- is when read the descriptions about stuff like leaves and such on vendors' websites which cater to these animals making very broad and expansive claims about their benefits, based simply on the fact that shrimp seem to eat them, and that they contain substances and compounds known to be beneficial from a "generic" nutritional standpoint- you know, like in humans.

All well-meaning, not intended to do harm to consumers. I'm sure...but perhaps occasionally, just a bit of a stretch, IMHO.

I just wonder if we stretch and assert too much sometimes?

I'm not saying that it's "bad" to make inferences (we do it all the time with various topics- but we qualify them with stuff like, "it could be possible that.." or "I wonder if..."), but I can't stand when absolute assertions are made without any qualification that, just because this leaf has some compound which is part of a family of compounds that are thought to be useful to shrimp, or that shrimp devour them...that it's a "perfect" food for them.

It's just a food- one of many possibilities out there.

Of course, I hope I'm not out there adding to the confusion! We try to hold ourselves to higher standards on this topic; yet, like so many things we talk about in the world of botanicals, there are no absolutes here.

What is fact is that some botanical/plant-derived materials, such as various seeds, root vegetables, etc., do have different levels of elements such as calcium and phosphorous, and widely varying crude protein. Stuff that's known to be beneficial to shrimp, of course. These things are known by science. Yet, I have no idea what some of the seed pods we offer as botanicals contain in terms of proteins or amino acids, and make no assertions about this aspect of them, above and beyond what I can find in scientific literature.

However, I suppose that one can make some huge over-generalizations that one seedpod/fruit capsule is somewhat similar to others, in terms of their "profile" of basic amino acids, vitamins, trace elements, etc. (gulp). We can certainly assume that some of this stuff, known to have nutritional value, can possibly make these materials potentially useful as a supplemental food source for fishes and shrimps.

Yet, IMHO that's really the best that we can do until more specific, scientifically rigid studies are conducted.

Now, we may not know which seed pods and such in and of themselves are more nutritious to fishes and shrimp than others, but we DO know from simple observation that some are better at "recruiting" materials on their surfaces which serve as food sources for aquatic organisms!

There is little disagreement on this topic.

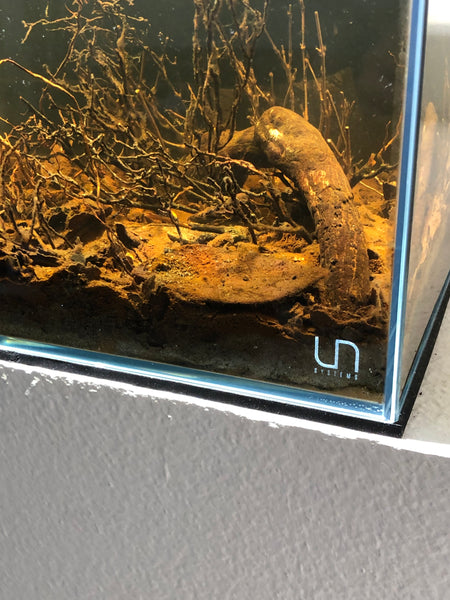

Yeah, I'm talking about the biofilms and fungal growth, which make their appearance on our botanicals, leaves, and wood after a few weeks of submersion...

As we've talked about ad nauseam here, biofilms are not only typically harmless in aquariums, they are utilized as a supplemental food source by a huge variety of fishes and shrimps in both Nature and the aquarium. They are a rich source of sugars and other nutrients, and could prove to be an interesting addition to a "nursery tank" for raising fry if kept in control. Like, add a bunch of leaves and botanicals, let them do their thing, and allow your fry to graze on them!

Don't believe me?

Ask almost any shrimp keeper-they'll "sing the praises" of biofilm for the "grazing" aspect!

And of course, it's long been known from field studies that as leaves and other plant materials break down, they serve as "fuel" for the growth of biofilm, fungi and microorganisms...which, in turn, provide supplemental food for our fishes. I've seen a bunch of videos of shrimps and fishes in the wild "grazing" over fields of decomposing leaves and the biofilms they foster.

And we know from years of personal experience and observation in the aquarium that fishes and shrimp will consume them directly, removing them from virtually any surface they form on.

And some materials are likely better than others at recruiting and accumulating biofilm growth. The "biofilm-friendly" botanical items seem to fall into several distinct categories: Botanicals with hard, relatively impermeable surfaces, softer, more ephemeral botanical materials which break down easily, and hard-skinned botanicals with soft interiors, and...

Okay, wait- that kind of covers like, everything, lol.

Yeah.

What that tells ME, the over-caffeinated, perhaps somewhat under-educated armchair "aquatic ecologist-wannabe", is that most of the botanicals we play with- in addition to being potentially consumed directly by aquatic organisms- likely also have some capability of recruiting biofilms.

And the idea of biofilms and such being an excellent supplemental food source for shrimp-and fishes- is not revolutionary...it's just something that we're finally getting around to agreeing about with our little friends! (And with the shrimp people, too)

And don't get me started about fungal growths...

Fungal growth in aquatic environments is absolutely essential for the function of the ecosystem. Scientists have determined that as much as 15% of the decomposing leaf biomass in many aquatic habitats is "processed" by fungi, according to one study I found.

Yes, fungi. Again.

Fungi tend to colonize wood and botanical materials, because they offer them a lot of surface area to thrive and live out their life cycle. And cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin- the major components of wood and botanical materials- are degraded by fungi which posses enzymes that can digest these materials! Fungi are regarded by biologists to be the dominant organisms associated with decaying leaves in streams, so this gives you some idea as to why we see them in our aquariums, right?

In aquairum work, we see fungal colonization on wood and leaves all the time. Most hobbyists will look on in sheer horror if they saw the extensive amount of fungal growth which occurs in the wild on their carefully selected, artistically arranged wood pieces! Yet, it's one of the most common, elegant, and beneficial processes that occurs in Nature!

And fungi are absolutely food for a huge variety of aquatic organisms- including fishes and shrimp.

Like, everyone.

Like, everyone.

Biofilms and fungi just don't appear out of thin air, though.

Most of these life forms enter into aquatic "food webs" in the form of...wait for it...detritus! Yup, both fine and course particular organic matter are a main source of these materials. I suppose this explains why heavy accumulations of detritus and algal growth in aquaria go hand in hand, right? Detritus is "fuel" for life forms of many kinds.

Think about this when you set up your next botanical-style aquairum:

Incorporating botanical materials in our aquariums for the purpose of creating the foundation for biological activity is the starting point. Leaves, seed pods, twigs and the like are not only "attachment points" for bacterial biofilms and fungal growths to colonize, they are physical location for the sequestration of the resulting detritus, which serves as a food source for many organisms, including our fishes.

Consider: Every botanical, every leaf, every piece of wood, every substrate material that we utilize in our aquariums is a potential component of... food production!

The initial setup of your botanical-style aquarium will rather easily accomplish the task of facilitating the colonization of said biofilms and fungal growths. There isn't all that much we have to do as aquarists to facilitate this but to simply add these materials to our tanks, and allow the appearance of these organisms to happen.

And we shouldn't obsess over removing every single bit of detritus, fungi, uneaten food etc. Yeah, to facilitate these aquarium "food webs", we need to avoid going crazy with the siphon hose! Simple as that, really! When you remove some of this stuff, you're literally stealing food from someone's "mouth" (or hyphae, if your a fungi!)

Yeah, the idea of embracing the production of natural food sources in our aquariums is elegant, remarkable, and really not all that surprising. They will virtually spontaneously arise in botanical-style aquariums almost as a matter of course, with us not having to do too much to facilitate it.

What about fry?

Can't the botanical-style aquarium, replete with its compliment of leaves, botanicals, and their resulting biofilms and fugal growths feed batches of fish fry easily?I think so. Our tanks seem like they could be the ultimate "nursery" for fry!

Everyone who breeds fishes has their own style of fry rearing.

Some hobbyists like bare bottom tanks, some prefer densely planted tanks, etc. I'm proposing the idea of rearing young fishes in a botanical-style aquarium filled with leaves, some seed pods, and maybe some plants as well. They physically and "functionally" mimics, at least to some extent, the habitats in which many young fishes grow up in.

My thinking is that decomposing leaves will not only provide material for the fishes to feed on and among, they will foster the aforementioned biofilms and fungal growths, and provide a natural "shelter" for them as well, potentially eliminating or reducing stresses. In Nature, many fry which do not receive parental care tend to hide in the leaves or other "biocover" in their environment, and providing such natural conditions will certainly accommodate this behavior.

Decomposing leaves can stimulate a certain amount of microbial growth, with "infusoria" and even forms of bacteria becoming potential food sources for fry. I've read a few studies where phototrophic bacteria were added to the diet of larval fishes, producing measurably higher growth rates. Now, I'm not suggesting that your fry will gorge on beneficial bacteria "cultured" in situ in your blackwater nursery and grow exponentially faster.

However, I am suggesting that it might provide some beneficial supplemental nutrition at no cost to you!

I've experimented with the idea of "onboard food culturing" in several aquariums systems over the past few years, which were stocked heavily with leaves, twigs, and other botanical materials for the sole purpose of "culturing" (maybe a better term is "recruiting) biofilms, small crustaceans, etc. via decomposition. I have kept a few species of small characins in these systems with no supplemental feeding whatsoever and have seen these guys as fat and happy as any I have kept.

And it's the same with that beloved aquarium "catch all" of "infusoria" we just talked about...These organisms are likely to arise whenever plant matter decomposes in water, and in an aquarium with significant leaves and such, there is likely a higher population density of these ubiquitous organisms available to the young fishes, right?

Now, I'm not fooling myself into believing that a large bed of decomposing leaves and botanicals in your aquarium will satisfy the total nutritional needs of a batch of characins, but it might provide the support for some supplemental feeding! On the other hand, I've been playing with this recently in my "varzea" setup, stocked with a rich "compost" of soil and decomposing leaves, rearing the annual killifish Notholebias minimus with great success.

It's essentially an "evolved" version of the "jungle tanks" I reared killies in when I was a teen. A different sort of look- and function! The so-called "permanent setup"- in which the adults and fry typically co-exist, with the fry finding food amongst the natural substrate and other materials present in the tank. Or, of course, you could remove the parents after breeding- the choice is yours. I admit that it's not the most "efficient" way to rear frying large numbers, but it's a cool experiment!

I'd take the concept even a bit further by "seeding" the tank with some Daphnia, Cyclops and perhaps some of the other commonly available live freshwater crustaceans and copepods, and letting them "do their thing" before the fry arrive. This way, you've got sort of the makings a little bit of a "food web" going on- the small crustaceans helping to feed off of some of the available nutrients and lower life forms, and the fish at the top of it all.

Now, granted, I'm totally romancing this and perhaps even over-simplifying it a bit. However, I think that there is a compelling case to be made for creating a rearing tank that supports a biologically diverse set of inhabitants for food sources.

The basis of it all would be leaves and some of the botanicals which seem to do a better job at recruiting biofilms- the "harder shelled/surfaced" stuff, like Jackfruit leaves, Yellow Mangrove leaves, Guava Leaves, Carinaina Pods, Dysoxylum pods, etc...I think these would be interesting items to include in a "nursery tank." And of course, they provide shelter and foraging areas and impart some tannins into the water...the "usual stuff."

It's fun to play with new ideas- or evolve old ones such as this. Obviously, this isn't be the "ultimate" fry-rearing technique; however, it's just another one of those ideas to have in our "arsenal" of skills that would be fun for serious-or casual- fish breeder to experiment more with.

I think it's one we have seriously legit basis for playing with more and more!

Nothing is wasted in Nature, right?

In the wild aquatic habitats we love so much, food webs are vital to the organisms which live in them. They are an absolute model for ecological interdependencies and processes which encompass the relationship between the terrestrial and aquatic environments.

We should embrace this in our aquarium work, and do our best to facilitate the processes which can lead to the development of "food webs" in our tanks, for fishes at all stages of life. The botanical style aquarium is literally "optimized" to provide benefits such as food production, by the very existence of its "operating system"- decomposing botanical materials!

Let's take advantage of this!

Let's try not to make too many assumptions and assertions- at least, not without doing some of our own research and "field work."

As hobbyists, let's continue to experiment, observe, learn from, and share our experiences and observations with others.

We all win from that.

In fact, that's likely the one absolute assertion I will make!

Stay curious. Stay disciplined. Stay objective. Stay experimental. Stay creative...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Scott Fellman

Author