- Continue Shopping

- Your Cart is Empty

Killifish and their terrestrial connections- Questioning convention, and lessons from Nature

Annual killifishes are beyond fascinating for us. Not only is their life cycle amazing, the fact that they are so intimately tied into their environment more than almost any fishes we've worked with in the hobby is an amazing 'unlock" for so many things we want to do as hobbyists.

These fishes are commonly found in the African Savannah, an ecosystem which essentially is a large tropical grassland, which receives its highest amount of seasonal rainfall during the summer. Savannah vegetation consists primarily of grasses and small, widely dispersed trees that don't create a closed canopy like you'd find in the rain forests, which allows large amounts of sunlight to reach the ground.

Literally, the soils and sediments of these habitats where annual fishes are found is of such importance, that it impacts every aspect of their existence- and it all starts with how it impacts the development of their embryos.These fishes inhabit (often temporary) pools, which are of very specific composition. Because of the way rain falls in these habitats, many of these habitats fill and empty with the weather seasonally.

And the very composition of the the substrate of these pools has profound influence on the life cycle of these killifishes.

Certain alkaline clay minerals, known as smectites, are necessary to provide suitable environmental conditions during the embryonic development phase of Nothobranchius in the substrates of desiccated Savannah pools. The muddy layer in these pools has a low degree of permeability, which enables water to remain in the pools after the surrounding water table has receded.

Without this essentially impermeable mud layer, such pools will quickly desiccate. Appearance-wise, this substrate material is dark brown to black in color, and typically forms a thick layer of soft mud on the bottom of these pools. A layer of organic material aggregates (typically dead aquatic and terrestrial vegetation) accumulates on the bottom of these pools.

However, it doesn't cover the entire bottom. Typically, you'll see a lot of open bottom without these vegetation. Interestingly, even with all of this rapidly decaying material, the water in these pools remains alkaline because of the high buffering capacity of the alkaline clay in the sediment.

Interesting. And here's something that I find even more compelling:

Nothobranchius almost never inhabit pools consisting only of those visually orange-colored laterite-rich soils. You'll find these pools all over the African savannah, especially after periods of intense rain, their substrates are generally composed of kaolinitic clay minerals, and as a result, they are slightly acidic.

Researchers have determined that these substrates are not suitable for Nothobranchius embryos to develop and survive during the dry periods.

As we've discussed many times, it's amazing how the characteristics of the aquatic habitats in which our fishes are found influence their life cycles. And of course, it's not limited to the annual killifishes of Africa. We find similar relationships between other types of African killiishes and their aquatic habitats.

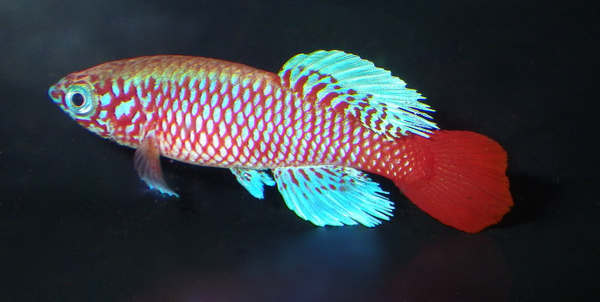

Such a case came to my attention when I was visiting a killifish forum on Facebook. One of the participants was discussing some new fishes he obtained, and one was from a rare genus called Episemion. Weird, because it is a fish that falls genetically halfway between Epiplatys and Aphyosemion.

Even more interesting to me was the discussion that it's notoriously difficult to spawn, and that it is only found in a couple of places in The Congo. In fact, the type description of E. krystallinoron, one of just a handful of identified Episemion species, is described as, "...a large river (~ 5 - 6 m) up to 1 m deep. The river near Medouneu at locality G 02 / 156 (= BBS 99 / 22) is also large (~ 4 - 5 m) and about 80 cm deep. At both localities the water is fast flowing, with sandy bottom and no aquatic vegetation. Episemion specimens were found amongst overhanging terrestrial vegetation..."

Good stuff... Reading through these type papers often gives you some good info on the ecology of the ecosystems from which our fishes come from! It's really interesting stuff!

And even more interesting to me was that it is in a region known for high levels of selenium (Se) in the soil...And that's VERY interesting. Selenium is known to be nutritionally beneficial to animals and humans at a concentration of 0.05-0.10ppm. It's an essential component of many enzymes and proteins, and deficiencies are known to cause diseases. One of it's known health benefits for animals is that it plays a key role in immunity and reproductive functions!

Boom! 💥

Okay, that helps with the "difficult to breed" part, right?

Selenium occurs in soil associated with sulfide minerals. And it's found in plants at varying concentrations which are dictated by the pH, moisture content, and other factors. As you might guess, higher concentrations of selenium are found in in the plants which occur in these regions.

Interesting...

So, I"m doubtful that we know the specific concentrations of selenium in many of the planted aquarium substrates out on the market, and most hobbyists aren't just throwing in that "readily available tropical Congo soil" - the one that you can pick up at any LFS- into their tanks, right? 😜

Oh, there isn't one...that's right.

So, how would we get more selenium into our tanks for our killies?

Botanicals could be one way.

Like, The Brazil nut...

And the Brazil nut is kind of known to us, isn't it? The "Monkey Pot" has something to do with this, right?

And, yes- it's technically a fruit capsule, produced from the abundant tree, Lecythis pisonis, native to South America -most notably, the Amazonian region. Astute, particularly geeky readers of "The Tint" will recognize the name as a derivative of the family Lecythidaceae, which just happens to be the family in which the genus Cariniana is located...you know, the "Cariniana Pod."

Yeah...this family has a number of botanical-producing trees in it, right?

(Our fave tree in all its jungle glory! Image by mauroguanandi, used under CC BY 2.0)

Yes. It DOES.

Hmm...Lecythidae...

Ahh...it's also known as the taxonomic family which contains the genus Bertholletia- the genus which contains the tree, Bertholletia excelsa- the bearer of the "Brazil Nut." You know, the one that comes in the can of "mixed nuts" that no one really likes? The one that, if you buy it in the shell, you need a freakin' sledge hammer to crack?

Yeah. That one.

Okay, I went off on a big old tangent, but imagine for just a minute...

Would it be possible to somehow utilize the "Monkey Pot" in a tank with these fishes to perhaps impart some additional selenium into the water? Okay, this begs additional questions? How much? How rapidly? In what form? Wouldn't it be easier to just grind up some Brazil nuts and toss 'em in? Or would the fruit capsule itself have a greater concentration of selenium? Would it even leach into the water? Or, could you just add some Selenium into the water?

Where the fuck am I going with this exercise?

I'm just sort of taking you out on the ledge here; demonstrating how the idea of utilizing botanicals to provide "functional aesthetics" is, at the every least, a possibility to help solve some potential challenges in the hobby.

It's one of many interesting things that one could contemplate in the aquarium hobby.

I was mussing once again about the difficulties that some hobbyists have had over the years incubating annual and other killie eggs in peat moss, and I couldn't help but reflect back on the idea that more acidic substrates tend to inhibit development of Nothobranchius embryos, according to some researchers... So, perhaps incubating Nothos eggs in other materials, like the aforementioned smectite and perhaps mud, would yield more consistent, reliable results?

Perhaps the (frustrating to many hobbyists) process of diapause could be overcome by incubating eggs in a material which more closely resembles the substrate in which they are found in Nature? Maybe?

Okay, maybe I'm heading off into territory which I'm not really qualified nor knowledgeable enough to comment on, and many serious killie keepers are likely rolling their eyes at me(or worse) right now- but it DOES make you wonder a bit, right? I mean, could there be some merit to questioning this stuff?

Why question a technique and the use of a material which experienced killifish fanciers have been utilizing for the better part of the century, with pretty damn good results, right?

Well, I can't help but at least wonder why peat has been used as the incubation media of choice for annual killies for so long ("...'cause it works, you fucking moron!")? I mean, is it because its physical moisture retention characteristics resemble, at least superficially, those of the substrates in which annual killie eggs are found? Could it be because it's cheap and readily available? Because it works "well enough" and that consistent results may really duplicated by the widest variety of hobbyists?

Well, likely all of the above. However...

Can we use something that works even better? IS there something that works better? I mean, peat is pretty acidic, right? (like, pH 4.4), and we've already seen scientific work which indicated that many Nothos are not found in ponds with highly acidic substrates, so...

"Do the work, Fellman."

Of course, I need to.

Only further research -by self-appointed prognosticators like me- and other, far more talented/experienced hobbyists than I will tell. Now, I suppose I need to at least explain my rationale for looking at stuff like this more critically..

I often think about my predication for questioning stuff that's long been held dear in the hobby, and wonder why I think the way I do. I mean, it's not like I'm some well-informed genius or something. I'm not trying to be a hell-raiser (well, occasionally...😆).

I just tend to look at Nature and ponder how we can more literally interpret Her characteristics in our aquarium hobby experiences. We've done this with blackwater aquariums, brackish aquariums, and the idea of facilitating and embracing stuff like biofilms, fungal growth, and detritus in our tanks.

And there is merit to so much of it, as we've all seen. We just need to open our minds to the idea of re-thinking all sorts of stuff that we've held dear for so long. Because that's how the hobby advances...as uncomfortable as the questioning of "conventional" ideas in the hobby might be to us.

Killifish are particularly fascinating to me, because, as we've mentioned already, they are so intimately tied to their environments, unlike so many other fishes are. And the connections between them and their environments- and the things we can learn from these relationships- are compelling and potentially game-changing in some instances.

And I'm confident enough- and humble enough- to open myself up to criticism from those who are far more knowledgeable than I. It's okay to accept that we might be way off...Because the humility and open-mindedness that we express when discussing what might be viewed as controversial ideas is a good thing that helps everyone.

That may be the best lesson from Nature that we can receive!

Stay open-minded. Stay inquisitive. Stay resourceful. Stay bold. Stay diligent...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Scott Fellman

Author