- Continue Shopping

- Your Cart is Empty

"Environmental Intimacy" and the Case for Killifishes...

Killifishes are beyond fascinating for us. Not only is their life cycle amazing, the fact that they are so closely connected to their environments perhaps more than almost any fishes we've worked with in the hobby is an amazing 'unlock" for so many things we want to do as hobbyists.

And the annual varieties, in particular, are really interesting, because of what I like to call "environmental intimacy"- the ecology and life cycle of the fishes are influenced profoundly by the environments in which they are found.

Literally, the composition of the soils and sediments of these habitats where annual fishes are found are of such importance, that they impact virtually every aspect of their existence- and it all starts with how it impacts the development of their embryos.These fishes inhabit (often temporary) pools, which are of very specific composition. Because of the way rain falls in these habitats, many of these habitats fill and empty with the weather seasonally.

Yeah- the substrate of these pools has profound influence on the life cycle of these killifishes.

Certain alkaline clay minerals, known to geologists as smectites, are necessary to provide suitable environmental conditions during the embryonic development phase of Nothobranchius in the substrates of desiccated Savannah pools. The muddy layer in these pools has a low degree of permeability, which enables water to remain in the pools after the surrounding water table has receded.

Without this essentially impermeable mud layer, such pools will quickly desiccate. Appearance-wise, this substrate material is dark brown to black in color, and typically forms a thick layer of soft mud on the bottom of these pools. A layer of organic material aggregates (typically dead aquatic and terrestrial vegetation) accumulates on the bottom of these pools.

However, it doesn't cover the entire bottom. Typically, you'll see a lot of open bottom without this vegetation. Interestingly, even with all of this rapidly decaying material, the water in these pools remains alkaline because of the high buffering capacity of the alkaline clay in the sediment.

Interesting. And here's something that I find even more compelling:

Nothobranchius almost never inhabit pools consisting only of those visually orange-colored, highly acidic, laterite-rich soils. You'll find these pools all over the African savannah, especially after periods of intense rain, and their substrates are generally composed of kaolinitic clay minerals, and as a result, they are slightly acidic.

Researchers have determined that these moderately acidic to alkaline substrates are what makes the habitats suitable for Nothobranchius embryos to develop and survive during the dry periods.

As we've discussed many times, it's amazing how the characteristics of the aquatic habitats in which our fishes are found influence their life cycles so significantly. And of course, it's not limited to the annual killifishes of Africa, but they are a sterling example of this "environmental intimacy," aren't they?

So, why keep them in a bare-bottomed plastic shoebox with a tray of peat? I mean, it's likely a function of practicality and utility, but is there a way that might more closely replicate the habitats from which they come?

Why not something different, like a "substrate-centric" filterless tank: Okay, this is not exactly earth shattering, but it's something we see less and less of today. Consider a small (2-5 gal/7.57-18.93l) aquarium, perhaps only partially filled, with a rich substrate, such as our NatureBase "Varzea" or "Igapo", with a small amount of leaf litter and some more diminutive seed pods (like, Parviflora, broken Fishtail Palmstems, etc.) and/or bark, crushed up and mixed in. Maybe add some oak twigs, or even small branches (Melastoma or Bantigue Wood).

Add some hardy plants, like our fave, Acorus, if you want call it a day. Dose initially and several times a week with PNS bacteria to help establish and maintain the microbiome. For fishes, I'm thinking of species like Epiplatys, Fundulopanchax, or Aphyosemium. And of course, you could try Nothos or South American Annuals, just ditch the plants, because they will be uprooted due to their substrate-spawning habits. Change about 20 percent of the water weekly, and that's about it. No heater required. No "filter" necessary.

Does it get any easier? It's essentially a more "permanent" play on the way killies have been set up and managed in aquariums for generations. The main difference is that the aquairum in this instance is likely a more faithful representation of the natural habitats from which these fishes come. As we have discussed before, you can "operate" these tanks by slowly draining out water to simulate a "dry" season.

The beauty is that the level of care required for many of these fishes is not that great. Keeping them in such a system helps reinforce many of the fundamental aspects of our botanical-style aquarium practice, including a greater understanding of the relationship between the fishes and their habitats.

Killies are perfect for these types of setups, because they offer us the opportunity to rear the resulting fry in a habitat which is perfect for supplying them with initial natural foods, such as Paramecium, Euglenids, etc. And even adding Cyclops, Daphnia etc. as well is cool, too. "In situ" food culture is a real advantage of this type of setup. Being able to leave the eggs/fry in place and removing the parents is an easy thing to do.

In fact, I have reared many species of killies in these types of setups a number of times from fry all the way to young adults, with almost no supplemental feeding during the first two to three months of their lives, and a growth rate comparable to fry that I've reared in dedicated "nursery" tanks with a lot of food.

Yeah, this is just an evolved, reimagined version of the "jungle tanks" of my youth, only instead of ridiculously dense plant growth, we have less emphasis on plants, and more liberal use of rich substrates and botanical materials.

The main "theme" of the killifish hobby, at least in my opinion as a sort of "peripheral" killie keeper, has been simply to breed them and maintain captive populations of them.

A super noble goal, of course, yet rather "one dimensional", in my opinion. The "formula" is straightforward: Keep them in small aquariums filled with spawning mops, containers of peat moss, and maybe a few floating plants. Useful, efficient, highly functional, and..well...boring.

The idea of controlled breeding in peat-filled containers is just one way to approach their care. Imagine the interesting types of "permanent setups" you could create by looking more closely at the actual physical/chemical/environmental aspects of their natural habitats and attempting to replicate them in the aquarium.

Yeah. As I've mentioned before, the habitats themselves are the key, IMHO, to unlocking more interest in these amazing fishes!

"Environmental Intimacy" is a very interesting phenomenon...And I think it can pull killies out of the hobby "backwaters" they inhabit. I think that it's the "shot in the arm" that the hobby needs to make 'em more popular!

Not convinced, you old-school killie people?

Hear me out...

Arguments abound online in killifish forums with hobbyists preferring all sorts of ways to popularize these rather under-appreciated fishes, and what many call a "moribund" sector of the aquarium hobby, seemingly lacking a significant influx of new hobbyists. So, why not solve this "problem" by working on "the whole picture" of killifish care?

The inspiration is right in front of us. The information about them is abundant.

Many killifish enthusiasts have visited the wild habitats of killies and documented information about the ecosystems in which they are found, so why not use this data to replicate this most interesting, yet remarkably under-represented aspect of the killie realm?

Think of what our community, which has a tremendous amount of experience with unique aspects of habitat replication, can bring to the table here!

I've already started doing some of this type of work with South American annual killifishes, keeping them in my "Urban Igapo" habitat replications in "wet/dry" cycles, and the results have been really interesting! Spawning annual fishes in an aquarium environment which more realistically and accurately represents the natural habitats from which they have evolved in over eons is truly exciting!

And of course, a vast variety of killifish species inhabit leaf-strewn, sediment-laden bodies of water.

Bodies of water which offer habitat "enrichment", physical structure, and chemical influence. Bodies of water which our community is quite "fluent" at replicating in the aquarium. Leaves, botanical materials, and sediments are right up our proverbial "alley", right?

Sediments and substrates and leaves...again!

Yeah, I suspect that we would do well to work with sediments, particularly sediments mixed with finely-crushed botanical materials like leaves. These materials will, of course, not only visually tint the water snd add some turbidity, they'll very accurately represent some of the chemical aspects of the natural habitats, too.

And of course, Africa has some other very compelling environments that would be equally fascinating to replicate in our aquaria. Environments seldom replicated in the hobby:

Tiny jungle streams, vernal pools, and... MUD PUDDLES!

Yes, mud puddles! Now, would it be possible to recreate a mud puddle in an aquarium to any degree? I think so! We've more-or-less done this already, right?

And what better fishes to use as "subjects" for this unique biotope-inspired work than killifishes?

I mean, for the hardcore biotope enthusiast, messing around with aquariums simulating the various habitats in which killies alone are found could be a lifelong obsession!

Imagine how cool it would be to delve into the world of killies...By working with "the whole picture" of their world?

To me, the reasons above and many others have kept them "top of mind" for me over the years, even though I may not always have kept them consistently.Their relative difficulty to obtain has sort of added to the "mystique" for me. That and the fact that they typically will not have "common names", and are generally referred to by their scientific name, followed by a geographic locale and some other numbers makes them all the more alluring to me!

Hmm...and "geographic locales" never scared anyone...They're like clues-keys to treasure troves of information that can unlock many secrets, right?

Yet, I digress... these arcane names don't help in the splashy, superficial "Insta world" of social media that we've created in the 21st century, I admit. When I see discussions on killie forums lamenting the fact that these fishes aren't more popular to newer hobbyists these days, it's kind of easy to see wyt, right?

I mean, shit- there's like 0.000034% chance that a fish with a name like "Austrolebias arachan, UYRT 2015-04" is EVER gonna knock off the Cardinal Tetra or Angelfish and crack the "Hot 1,000" list of the most popular aquarium fishes, right?

Yet, as I just mentioned, the precise Latin descriptors and type localities bely a secret to those who do the work...they give us information of incalculable value about the specific biotope/habitat from where the fish hails from. And to those of us who strive to replicate- on many levels- the wild habitats from which our fishes come from, this stuff is pure GOLD!

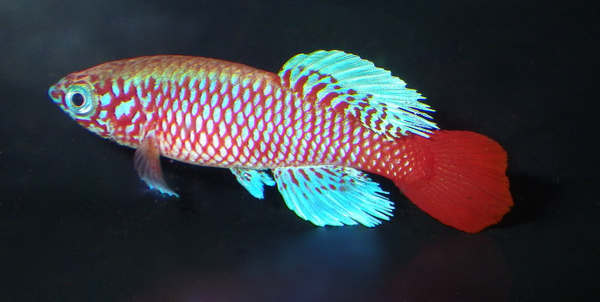

(Chromaphyosemion bivittatum, pic by Mike PA Calnun)

And of course, one of the things I like best about killifishes is that many come from habitats that would be perfect for us to replicate with our skills and interest.

Yes, they've been kept by avid enthusiasts for a century or more, but there are still so many secrets to unlock, practices to perfect. I think that the killifish hobby is really great at what they do, but it's a classic case of "not seeing the forest for the trees!" The answer to getting these amazing fishes more into the mainstream of the hobby AND bringing in new enthusiasts at the same time is right in front of our eyes!

And there ARE problems that even the hardcore "elders" of this fascinating niche deal with. Problems that could maybe use a dose of this "new thinking."

I was reading about the difficulties that some hobbyists have had over the years incubating annual and other killie eggs in peat moss, and I couldn't help but reflect back on the idea that more acidic substrates tend to inhibit development of Nothobranchius embryos, according to some researchers... So, perhaps incubating Nothos eggs in other materials, like the aforementioned smectite and perhaps mud, would yield more consistent, reliable results?

Perhaps the (frustrating to many hobbyists) process of diapause could be overcome by incubating eggs in a material which more closely resembles the substrate in which they are found in Nature? Maybe?

Okay, maybe I'm heading off into territory which I'm not really qualified nor knowledgeable enough to comment on, and many serious killie keepers are likely rolling their eyes at me(or worse) right now- but it DOES make you wonder a bit, right? I mean, could there be some merit to questioning this stuff?

Why question a technique and the use of a material which experienced killifish fanciers have been utilizing for the better part of the century, with pretty damn good results, right?

Well, I can't help but at least wonder why peat has been used as the incubation media of choice for annual killies for so long ("...'cause it works, you fucking moron!")? I mean, is it because its physical moisture retention characteristics resemble, at least superficially, those of the substrates in which annual killie eggs are found? Could it be because it's cheap and readily available? Because it works "well enough" and that consistent results may really duplicated by the widest variety of hobbyists?

Well, likely all of the above. However...

Can we use something that works even better? IS there something that works better? I mean, peat is pretty acidic, right? (like, pH 4.4), and we've already seen scientific work which indicated that many Nothos are not found in ponds with highly acidic substrates, so...

"Do the work, Fellman."

Of course, I need to. I will.

Only further research -by self-appointed prognosticators like me- and other, far more talented/experienced/qualified hobbyists than I will determine if this is a good idea. Now, I suppose I need to at least explain my rationale for looking at stuff like this more critically..

I often think about my predilection for questioning stuff that's long been held dear in the hobby, and wonder why I think the way I do. I mean, it's not like I'm some well-informed genius or something. I'm not trying to be a hell-raiser (well, occasionally...😆).

Creating aquariums that specifically aim to replicate the function of particular habitats of some of these species is simply beyond just an "under-served" area of the hobby. It's one which YOU could make very useful contributions to with a little research and some cool documented work!

I couldn't think of a better way to increase awareness within the hobby and outside of it about an amazing group of fishes, and the awe-inspiring natural habitats from which they come. Habitats which are increasingly endangered by mankind's encroachments and activities.

Habitats which happen to need our protection more than ever!

Habitats for which we can create a greater appreciation and understanding of by attempting to replicate them in the aquarium in function and form!

What better outcome for the fishes, the hobby, and the planet-could there be than that?

And of course, the case for working with killifishes is made easily when we talk about things in this context. Yet, a whole world of possibilities awaits with the total array of tropical fishes- and information about them- now at our disposal.

Yeah, studying the idea of "environmental intimacy" is something that I think could really impact the hobby in a positive way. It's one of the concepts that ties in so well with what we do in the natural botanical-style aquairum world. And the hobby has never been in a better position to explore ideas like this than it is now...

Let's get cracking!

Stay enthusiastic. Stay brave. Stay curious. Stay dedicated...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Scott Fellman

Author