- Continue Shopping

- Your Cart is Empty

Botanical movements, breakdowns- and mental shifts...

As lovers of natural, botanical-style aquariums, it seems like we've made great strides in fostering a mental shift in the hobby. This has the benefit of allowing us to let go of some long-held beliefs, ways of doing things, and ideas, in favor of looking at what really happens in Nature and in our aquariums. Rather than avoid something different, simply because "its always been done a certain way" and we don't want to rock the boat, we're opening our minds and going for it!

Even the aesthetics that we embrace in our natural aquariums are a complete shift in what we've accepted in the past. One of he many things that we enjoy about leaves, twigs, seed pods and other botanical materials that we love so much around here is that they are extremely versatile (which we've discussed ad infinitum, of course), including simply how they "fall" in our aquascapes, and the impact which they have on our fishes while they're physically present in our aquariums.

If you think about it, the fact that we are understanding of the transience and structure of our botanicals opens us up to some unique aesthetic experiences in our aquariums. Think about this: When you accidentally "redistribute" botanicals in your aquariums during maintenance, unique new "microhabitats" for your fishes are created. A simple thought- but profoundly important, really. And readily apparent to all who play with leaves and botanicals.

This concept also correlates very nicely with my personal experiences, and a number of studies on streams which I've read over the years. I love this topic (and fortunately, hobbyists like you are as geeked-out as I am about it, too!) because it's one of those things that most of us don't even think of vis-a-vis aquariums, and it's only now becoming a "thing" as more of us play with these materials!

In many topical streams, the water depth, and intensity of the flow changes during periods of rain and runoff, creating significant re-distribution of the materials which accumulate on the bottom, such as leaves, seed pods, and the like. Larger, more "hefty" materials, such as submerged logs, etc., will tend to move less frequently, and in many instances, they'll remain stationary, providing a physical diversion for water as substrate materials accumulate around them.

A natural "dam", of sorts, if you will.

Yet, most of the small stuff tends to move around quite a bit... One might say that the "material changes" created by this movement of materials can have significant implications for fishes. In the case of our aquariums, this "redistribution" of material can create interesting opportunities to not only switch up the aesthetics of our tanks, but to provide new and unique little physical areas for many of the fishes we keep.

The benthic microfauna which our fishes tend to feed on also are affected by this phenomenon, and as we know, the fishes tend to "follow the food", making this a case of the fishes learning (?) to adapt to a changing environment. And perhaps...maybe...the idea of fishes sort of having to constantly adjust to a changing physical (note I didn't say "chemical") environment could be some sort of "trigger", hidden deep in their genetic code, that perhaps stimulates overall health, immunity or spawning?

Something in their "programing" that says, "Your at home..." Triggering specific adaptive behaviors?

Maybe?

I find this possibility fascinating, because we can learn more about our fishes' behaviors, and create really interesting habitats for them simply by adding botanicals to our aquariums and allowing them to "do their own thing"- to break apart as they decompose, move about as we change water or conduct maintenance activities, or add new pieces from time to time.

By accepting and embracing these changes and little "evolutions", we're helping to create really great captive representations of the compelling wild systems we love so much!

Leaf litter beds, in particular, tend to evolve the most, as leaves are among the most "ephemeral" or transient of botanical materials we use in our aquariums. This is true in Nature, as well, as materials break down or are moved by currents, the structural dynamics of the features change.

We have to adapt a new mindset when aquascaping with leaves- that being, the 'scape will "evolve" on its own and change constantly...Other than our most basic hardscape aspects- rocks and driftwood- the leaves and such will not remain exactly where we place them.

To the "artistic perfectionist"-type of aquascaper, this will be maddening.

To the aquarist who makes the mental shift and accepts this "wabi-sabi" idea (yeah, I'm channeling Amano here...) the experience will be fascinating and enjoyable, with an ever-changing aquascape that will be far, far more "natural" than anything we could ever hope to conceive completely by ourselves.

Yeah, those "mental shifts" again.

It's all about understanding what happens in Nature, and appreciating how it also occurs- on a miniature scale- in our aquariums. I believe that the "material changes" which occur so often in our botanical-style natural aquariums provide us with fascinating and precious opportunities to witness the lifestyles and behaviors of our fishes in ways we have previously not seen, or perhaps appreciated-before.

Social behaviors, feeding, and even spawning events are affected as much by the spatial-physical environments in which our fishes reside as they are by the chemical aspects of the water. And the internal mechanisms and instincts which our fishes utilize to exist in their environment are as much a part of their existence as the very water which comprises their world.

Keep that in mind the next time your carefully-arranged botanical bed gets "redistributed" by an influx of new water during an exchange, or a haphazard pass of the algae scraper...or even by the errant whims of those damn cichlids!

It's not something to freak out about.

Rather, it's something to celebrate! Life, in all of it's diversity and beauty, still needs a stage upon which to perform...and you're helping provide it, even with this "remodeling" of your aquascape taking place daily. Stuff gets moved. Stuff gets covered in biofilm.

Stuff breaks down. In our aquairums, and in Nature.

Embrace whatever moves your scape forward...

Kind of neat when you look at it from that angle, huh?

Stay thoughtful. Stay fascinated. Stay curious. Stay creative. Stay engaged. Stay chill...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Not my cup of tea...But it might be yours.

One of the weird (but cool) things about being in the natural, botanical-style aquarium game is that you are frequently exposed to a lot of interesting information shared by hobbyists and vendors worldwide. Every once in a while, I'll have a friend contact me about something that I'm "missing out on" or some new "thing" that will "change the game" and provide an "existential threat" to Tannin Aquatics. I certainly appreciate that, but it's okay.

And of course, I DO take note and check out the "thing" and see what it's all about. And, to be honest, 9 times out of 10, it's usually a forum discussion about people collecting their own botanicals (which I've encouraged from day one of our existence and still do...), or using some "extract" or "solution" to create "blackwater" easily as an alternative to leaves or what not.

Of course, these "extracts" almost always tend to be things we've done for a generation or two in the hobby, and are no better-or worse- than the idea of tossing leaves and botanicals in the aquarium, in terms of what they appear to do on the surface.

And it almost always seems to me that these "solutions" are simply an alternative of sorts; generally one which requires less effort or process to get some desired result. Of course, they also play into one of the great hobby "truisms" of the 21st century:

Like, waiting for stuff. We love "hacks" and shortcuts. We're impatient.

Impatience is, I suppose, part of being human, but in the aquarium hobby, it occasionally drives us to do things that, although are probably no big deal- can become a sort of "barometer" for other things which might be of questionable value or risk. ("Well, nothing bad happened when I did THAT, so...") Or, they can cumulatively become a "big deal", to the detriment of our tanks. Others are simply alternatives, and are no better or worse than what we're doing with botanicals, at least upon initial investigation.

Now, for a lot of reasons, I f---ing hate most "hacks" that we use.

To many, "hacking" it implies a sort of "inside way" of doing stuff...a "work-around" of sorts. A term brought about by the internet age to justify doing things quickly and to eliminate impatience because we're all so busy. I think it's a sort of sad commentary on the prevailing mindset of many people.

We all need stuff quickly...We want a "shortcut. "Personally, I call it "cheating."

Yes. With what we do, a "hack" really is trying to cheat nature. Speed stuff up. Make nature work on OUR schedules.

Bad idea, if you ask me.

Of course, there are some hacks, like the one we're about to discuss, which aren't necessarily "bad" or harmful- just different. There is absolutely nothing wrong with doing them. Yet, they deny us some pleasures and opportunities to learn more about the way Nature works. And we can't fool ourselves into believing that they are some panacea, either.

The one that seems to come up at least a few times a year in discussion, and is often preferred to me as rendering the botanical-style aquarium "obsolete" is the use of...tea.

If you haven't heard of it before, there is this stuff called Rooibos tea, which, in addition to bing kind of tasty, has been a favored "tint hack" of many hobbyists for years. Without getting into all of the boring details, Rooibos tea is derived from the Aspalathus linearis plant, also known as "Red Bush" in South Africa and other parts of the world.

(Rooibos, Aspalathus linearis. Image by R.Dahlgr- used under CC-BY S.A. 2.5)

It's been used by fish people for a long time as a sort of instant "blackwater extract", and has a lot going for it for this purpose, I suppose. Rooibos tea does not contain caffeine, and and has low levels of tannin compared to black or green tea. And, like catappa leaves and other botnaicals, it contains polyphenols, like flavones, flavanols, aspalathin, etc.

Hobbyists will simply steep it in their aquariums and get the color that they want, and impart some of these substances into their tank water. I mean, it's an easy process. Of course, like any other thing you add to your aquarium, it's never a bad idea to know the impact of what you're adding.

Like using botanicals, utilizing tea bags in your aquarium requires some thinking, that's all.

The things that I personally dislike about using tea or so-called "blackwater extracts" are that you are simply going for an effect, without getting to embrace the functional aesthetics imparted by adding leaves, seed pods, etc. to your aquarium as part of its physical structure, and that there is no real way to determine how much you need to add to achieve______.

Obviously, the same could be said of botanicals, but we're not utilizing botanicals simply to create brown water or specific pH parameters, etc.

Yet, with tea or extracts, you sort of miss out on replicating a little slice of Nature in your aquarium. And of course, it's fine if your goal is just to color the water, I suppose. And I understand that some people, like fish breeders who need bare bottom tanks or whatever- like to condition water without all of the leaves and twigs and nuts we love.

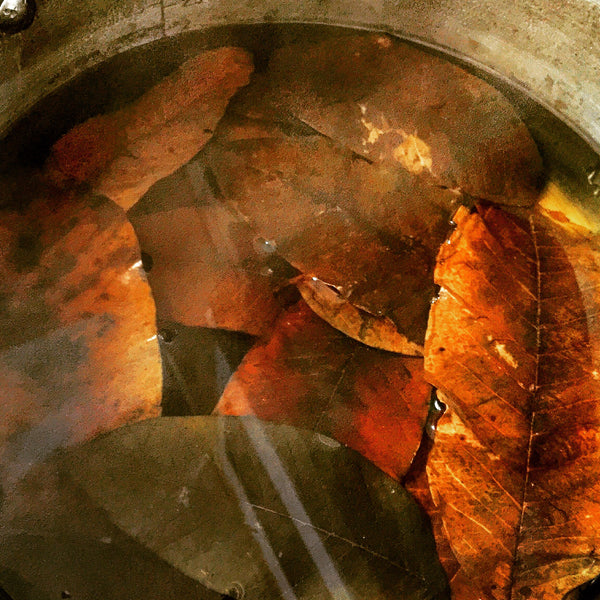

On the other hand, if you're trying to replicate the look and function (and maybe some of the parameters) of THIS:

You won't achieve it by using THIS:

It's simply a shortcut.

And look, I understand that we are all looking for the occasional shortcuts and easier ways to do stuff. And I realize that none of what we proffer here at Tannin is a n absolute science. It's an art at this point. There is no current way available to the hobby to test for "x" types or amounts of tannins (of which there are hundreds) in aquariums. I have not found a study thus far which analyzed wild habitats (say, Amazonia) for tannin concentrations and specific types, so we have no real model to go on.

The best we can do is create a reasonable facsimile of Nature.

We have to understand that there are limitations to the impacts of botanicals, tea, wood, etc. on water chemistry. Adding liter upon liter of "extract" to your aquarium will have minimal pH impact if your water is super hard. When you're serious about trying to create more natural blackwater conditions, you really need an RO/DI unit to achieve "base water" with no carbonate hardness that's more "malleable" to environmental manipulation. Tea, twigs, leaves- none will do much unless you understand that.

I'm not trying to throw a wet blanket on any ideas we might have. I'm not feeling particularly defensive about using tea or other "extracts" because I sell botanical materials for a living. It's sort of apples and oranges, really.

And hey, the whole idea of utilizing concentrated extracts of stuff is something I've looked on with caution for a long time, and we've discussed here before. I'm an "equal opportunity critic"- I'll jump on our community for stuff we do, too! 🤬

One of the things that I have an issue with in our little hobby sector is the desire by many "tinters" to make use of the water in which the initial preparation of our botanicals takes place in as a form of "blackwater tea" or "blackwater extract."

Now, while on the surface, there is nothing inherently "wrong" with the idea, I think that in our case, we need to consider exactly why we boil/soak our botanicals before using them in the aquarium to begin with.

I discard the "tea" that results from the initial preparation of botanicals- and I recommend that you do, too.

Here's why:

As I have mentioned many times before, the purpose of the initial "boil and soak" is to release some of the pollutants (dust, dirt, etc.) bound up in the outer tissues of the botanicals. It's also to "soften" the leaves/botanicals that you're using to help them absorb water and sink more easily. As a result, a lot of organic materials, in addition tannins and humic substances are released.

So, why would you want a concentrated "tea" of dirt, surface pollutants, and other organics in your aquarium as a "blackwater extract?" And (dredging top a similar question asked above) how much do you need? I mean, what is the "concentration" of desirable materials in the tea relative to the water? I mean, it's not an easy, quick, clean thing to figure, right?

There is so much we don't know.

A lot of hobbyists tell me they are concerned about "wasting" the concentrated tannins from the prep water. Trust me, the leaves and botanicals will continue to release the tannins and humic substances (with much less pollutants!) throughout their "useful lifetimes" when submerged, so you need not worry about discarding the initial water that they were prepared in.

It's kind analogous to adding the "skimmate" (the nasty concentrated organics removed by your protein skimmer via foam fractionation in your marine aquarium) back into your aquarium because you don't want to lose the tiny amount of valuable salt or some trace elements that are removed via this process.

Is it worth polluting your aquarium for this?

I certainly don't think so!

Do a lot of hobbyists do this and get away with this? Sure. Am I being overly conservative? No doubt. In Nature, don't leaves, wood, and seed pods just fall into the water? Of course.

However, in most cases, nature has the benefit of dissolution from thousands of gallons/litres of water, right? It's an open system, for the most part, with important and export processes far superior and efficient to anything we can hope to do in the confines of our aquariums!

Okay, I think I beat that horse up pretty good!

If you want to use the water from the "secondary soak", I'd feel a lot better about that..The bulk of the surface pollutants will have been released at that point. Better yet is the process of adding some (prepared) leaves/botanicals to the containers holding the makeup water that you use in your water exchanges. The materials will steep over time, adding tannins and humic substances to the water.

How much to use?

Well, that's the million dollar question.

Who knows?

It all gets back to the (IMHO) absurd "recommendations" that have been proffered by vendors over the years recommending using "x" number of leaves, for example, per gallon/liter of water. There are simply far, far too many variables- ranging from starting water chem to pH to alkalinity, and dozens of others- which can affect the "equation" and make specific numbers unreliable at best.

You need to kind of go with your instinct. Go slowly. Evaluate the appearance of your water, the behaviors of the fishes...the pH, alkalinity, TDS, nitrate, phosphate, or other parameters that you like to test for. It's really a matter of experimentation.

I'm a much bigger fan of "tinting" the water based on the materials in the aquarium. The botanicals will release their "contents" at a pace dictated by their environment. And, when they're "in situ", you have a sort of "on board" continuous release of tannins and mic substances based upon the decomposition rate of the materials you're using, the water chemistry, etc.

Of course, you can still add too many, too fast, as we've mentioned numerous times. It's all about developing your own practices based on what works for you.. In other words, incorporating them in your tank and evaluating their impact on your specific situation. It's hardly an exact science. Much more of an "art" or "best guess" thing than a science..at least right now.

That being said, I think that our entire botanical-style aquarium approach needs to be viewed as just that- an approach. A way to use a set of materials, techniques, and concepts to achieve desired results consistently over time. A way that tends to eschew short-term "fixes" in favor of long-term technique.

In my opinion, this type of "short-term, instant-result" mindset has made the reef aquarium hobby of late more about adding that extra piece of gear or specialized chemical additive as means to get some quick, short term result than it is a way of taking an approach that embraces learning about the entire ecosystem we are trying to recreate in our tanks and facilitating long-term success.

Yeah, once again- the "problem" with Rooibos or blackwater extracts as I see it is that they encourage a "Hey, my water is getting more clear, time to add another tea bag or a teaspoon of extract..." mindset, instead of fostering a mindset that looks at what the best way to achieve and maintain the desired results naturally on a continuous basis is. A sort of symbolic manifestation of encouraging a short-term fix to a long-term concern.

Again, there is no "right or wrong" in this context- it's just that we need to ask ourselves why we are utilizing these products, and to ask ourselves how they fit into the "big picture" of what we're trying to accomplish. And we shouldn't fool ourselves into believing that you simply add a drop of something- or even throw in some Alder Cones or Catappa leaves- and that will solve all of our problems. Are we fixated on aesthetics, or are we considering the long-term impacts on our closed system environments?

Sure, I can feel cynicism towards my mindset here. I understand that.

However, if we look at the use of extracts and additives, and additional botanicals- for that matter- as part of a "holistic approach" to achieving continuous and consistent results in our aquariums, that's a different story altogether.

It makes a lot more sense to learn a bit more about how natural materials influence the wild blackwater habitats of the world, and to understand that they are being replenished on a more or less continuous basis, then considering how best to replicate this in our aquariums consistently and safely.

So, enjoy your tea. Prep your botanicals. Replace your leaves. Observe, study, inquire. Read. Share.

Remember, it's a hobby. A marathon, not a sprint. And to truly understand what goes on in Nature, it's never a bad idea to replicate Nature to the best extent possible- even if it's not a "hack" sometimes.

Stay diligent. Stay patient. Stay bold. Stay curious. Stay excited. Stay engaged...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

The alluring case for Cryptocoryne...

I think I've always had this "romanticized" view of the aquarium hobby. I'm not sure what the exact reason for this is, but I think that there are a number of possibilities.

Maybe it's because I grew up in a household where my dad was a fish geek, and when most kids were perusing comic books, I was reading some of my Dad's fish book collection, which included what are now classics, like Innes' "Exotic Aquarium Fishes" and Axelrod's "Atlas of Tropical Fish", and host of guppy books from the "Golden Age" of aquarium keeping (the 1960's).

Perhaps it's because there was something enigmatic that the aquarium hobby represented...A window into an exotic and fascinating world unlike any other. Maybe it was because the fish names, the stories, and the habitats from which they hailed...

Regardless, I was hooked at an early age, and aquatic plants were- and are- a part of this romantic allure. I remember the first truly "exotic" aquarium plant I ever had was Cryptocoryne. It was the ultimate "cool plant"- something that grew in those earthy, tinted habitats that I find so irresistible. There are so many reasons why Crypts are the ultimate plant that the natural-style, blackwater aquarium enthusiast should be into! Oh, and they are under-appreciated in many instances, too...yet another reason to love them!

Now, to give a little context, I know that lot of you ask why I don't go on and on and on about aquarium plants in general. I mean, they're the darlings of the aquascaping world and are perhaps the ultimate "functionally aesthetic" aquarium accent. They not only enhance the aquarium environment- they help create it.

Now, I guess I like taking a sort of "outsider" view of plants. I have to admit, I sort of "hate" on the way they are elevated like "set pieces" in the frothy competition aquascaping world; sort of turned into the freshwater equivalent of coral frags. You know, "named cultivars", specific "roles" for plants, weird "fanboy" adulation for bizarre reasons, etc.

Don't get me wrong- aquatic plants are cool. I really like them, and I'm starting to use them more and more in my own aquariums. Now, unlike a lot of "scapers" out there, I'm not into selecting a plant to represent those found in a specific habitat. Rather, I look at them as a means to represent a specific habitat. A more literal interpretation, I suppose. Specifically, I like plants which come from rich, earthy, moderately-illuminated blackwater habitats.

And that's where "Crypts" really shine.

Hailing from India, New Guinea, and other parts of Southeast Asia, these plants tend to grow in areas of rich soil, moderate to minimal water movement, and seasonally inundated pools and marginal stream areas. Some are even found in brackish habitats! Oh, and they flower. Ever seen that? I mean, this is cool, right?

And the habitats that Cryptocoryne are found in...wow! Those habitats are exactly in our "wheelhouse", as the expression goes. I suppose the reef hobbyist in me likes them because they remind me a lot of corals, in terms of variety, range, and hardiness.

There are many unique growth forms and variations in this family, all of which have their place in the aquarium.

Crypts are well known for thriving in lower light, richer substrates, and emersed conditions. They like being placed...and left the hell alone. How can I not respect that? They can survive under acidic or alkaline pH levels, depending upon the origin of the species you're playing with. And you don't have to use CO2 to make 'em thrive, although it can help. Iron-rich and nutritive substrates are ideal for them.They tend to grow slowly. Now, they also have a reputation for being somewhat temperamental!

Yes, as we all have likely heard, they can be surprisingly sensitive to environmental changes, such as water temperatures and nutrient levels. They will often fall to what is known commonly as "Cryptocoryne melt"- essentially a series of maladies such as holes in their leaves, disintegrating stems, and just turning to mush...Sort of the freshwater aquarium equivalent of the coral horror known as "RTN" (rapid tissue necrosis).

Now, the cool thing about this malady is that it responds welt two of my favorite aquarium hobby "constants"- time and patience. A little patience with affected plants will be rewarded by allowing them to simply regenerate new leaves from the roots, which are typically unharmed. It's really easy to panic and pull the plants when this happens. I'm a big fan of letting them be and seeing how they come back.

So, yeah, these cool plants play right into all of the elements which I truly love.

And of course, this little piece is absolutely not intended to be an authoritative guide to the Cryptocoryne. I admit that when it comes to aquatic plants, my knowledge is pretty...shitty, really. Now, although my knowledge of these plants- and aquatic plants in general- may not be vast, it is based on personal experiences- not "regurgitated" hobby info- and shows you that even a person who "dabbles" in plants can enjoy them and have success with them.

My earnest hope is that hobbyists in our "sector" will continue to experiment with plants, and especially make use of some of the species that are known to do well in blackwater conditions. I'm excited about simply inspiring you to take another look- perhaps a closer look- at the idea of incorporating speciality plants in our natural, botanical-style systems.

So yeah, whatever it is that motivates you to look into some plants for our style of aquariums is the goal here. Let's see some interesting work with plants, for the benefit of all who play in this tinted, somewhat dirty world we play in. Crypts, in particular, are plants which cans be alternately touchy, hardy, challenging to our patience, and altogether interesting...That's my case for Cryptocoryne.

Stay inquisitive. Stay experimental. Stay excited. Stay diligent. Stay patient. Stay open-minded...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Clearing up some stuff...

As enthusiasts of natural-style botanical-influenced aquariums, we are super-attuned to the color of our water. Most of us are into the dark-brown, tannin-stained water that characterizes so many wild habitats in the aquatic ecosystems of the world.

As you likely know by now, there are a number of factors which contribute to the color of the water in your blackwater aquariums; specifically tannins released by the leaves, wood, and other botanicals you have in your tank. As we have discussed now like, 327 times (okay, maybe less...)- in many situations, leaves and other botanicals will have little to no influence on pH (unless your utilizing a water source, such as reverse osmosis, which yields product water with extremely low mineral content and is more "amicable" to pH reduction...).

However, they will affect the color and in some instances the visual clarity of the water.

And color generally has absolutely nothing to do with the pH of the water, really.

Oh, and clarity...I know we've talked about the difference between clarity and color before, but let's hit on it one more time. I really want to see less of those, "I added a bunch of catappa leaves and seed pods from that vendor on eBay, and my water is a dark brown color, but the pH is still 7.6! What gives?" sort of questions that populate online forums worldwide.

It's a question that needs analysis from several factors, starting with the impact that botanical materials have on water chemistry (which we've addressed a bunch of times here), and encompassing their impact on quality, color and clarity.

And, much to the confusion of the aquarium world, they're all sort of interrelated.

We do have a sort of "historical bias" of just what aquarium water should look like. As aquarists, we were pretty much indoctrinated from the start that our tanks should have "crystal clear, blue-white water", and that this is one of the benchmarks of a healthy aquarium.

And of course, I won't disagree that "clear" water is nice. I like it, too...However, I would make the case that "crystal clear" water is: a) not always solely indicative of "healthy" or "optimum" , and b) not always what fishes encounter in nature.

The point is, we as fish geeks seem to associate color in water with overall "cleanliness", or clarity. The reality is, in many cases, that the color and clarity of the water can be indicative of some sort of issue, but color seems to draw an immediate "There is something wrong!" from the uninitiated!

And it's kind of funny- if you talk to ecologists familiar with blackwater habitats, particularly those in the Amazonian region which many of us love so much- they are often considered some of the most "impoverished" waters around, at least from a mineral and nutrient standpoint.

In the aquarium, the general hobby at large doesn't think about "impoverished." We just see colored water and think..."that shit's dirty!"

And of course, this is where we need to attempt to separate the two factors:

Cloudiness and "color" are generally separate issues for most hobbyists, but they both seem to cause concern. Cloudiness, in particular, may be a "tip off" to some other issues in the aquarium. And, as we all know, cloudiness can usually be caused by a few factors:

1) Improperly cleaned substrate or decorative materials, such as driftwood, etc. (creating a "haze" of micro-sized dust particles, which float in the water column).

2) Bacterial blooms (typically caused by a heavy bioload in a system not capable of handling it. Ie; a new tank with a filter that is not fully established and a full compliment of livestock).

3) Algae blooms which can both cloud AND color the water (usually caused by excessive nutrients and too much light for a given system).

4) Poor husbandry, which results in heavy decomposition, and more bacterial blooms and biological waste affecting water clarity. This is, of course, a rather urgent matter to be attended to, as there are possible serious consequences to the life in your system.

And, curiously enough, the "remedy" for cloudy water in virtually every situation is similar: Water changes, use of chemical filtration media (activated carbon, etc.), reduced light (in the case of algal blooms), improved husbandry techniques (i.e.; better feeding practices and more frequent maintenance), and, perhaps most important- the passage of time.

So, yeah, clarity of the water is directly related to the physical dissolution of "stuff" in the water, and is influenced-and mitigated by- a wide-range of factors. And, don't forget that the botanical materials will impact the clarity of the water as they begin to decompose and impart the lignin, tannins, and other compounds from their physical structure into the water in our aquariums.

And in many cases, the water will not be "crystal clear" in botanical-influenced aquariums. It will have some "turbidity"-or as one of my friends likes to call it, "flavor."

Remember, just because the water in a botanical-influenced aquarium system is brownish, and even slightly hazy, it doesn't mean that it's of low quality, or "dirty", as we're inclined to say. It simply means that tannins, humic acids, and other substances are leaching into the water, creating a characteristic color that some of us geeks find rather attractive. If you're still concerned, monitor the water quality...perform a nitrate or phosphate test; look at the health of your animals. These factors will tell the true story.

You need to ask yourself, "What's happening in there?"

I believe that a lot of what we perceive to be "normal" in aquarium keeping is based upon artificial "standards" that we've imposed on ourselves over a century of modern aquarium keeping. Everyone expects water to be as clear and colorless as air, so any deviation from this "norm" is cause for concern among many hobbyists.

I can think of at least one or two other things that are influenced by the same processes, which we accept without question in our everyday lives...

People ask me a lot if botanicals can create "cloudy water" in their aquariums, and I have to give the responsible answer- yes.

Of course they can!

If you place a large quantity of just about anything that can decompose in water, the potential for cloudy water caused by a bloom of bacteria, or even simple "dirt" exists. The reality is, if you don't add 3 pounds of botanicals to your 20 gallon tank, you're not likely to see such a bloom. It's about logic, common sense, and going slowly.

A bit of cloudiness from time to time is actually normal in the botanical-style aquarium.

And, of course, what we label as "normal" in our botanical-style aquarium world has always been a bit different from the hobby at large.

In my home aquariums, and in many of the really great natural-looking blackwater aquariums I see from other hobbyists, the water is dark, almost turbid or "soupy" as one of my fellow blackwater/botanical-style aquarium geeks refers to it. You might see the faintest hint of "stuff" in the water...perhaps a bit of fines from leaves breaking down, some dislodged biofilms, pieces of leaves, etc. Just like in nature. Chemically, it has undetectable nitrate and phosphate..."clean" by aquarium standards.

Sure, by municipal drinking water standards, color and clarity are important, and can indicate a number of potential issues...But we're not talking about drinking water here, are we?

"Turbidity." Sounds like something we want to avoid, right? Sounds dangerous...

On the other hand, "turbidity", as it's typically defined, leaves open the possibility that it's not a negative thing:

"...the cloudiness or haziness of a fluid caused by large numbers of individual particles that are generally invisible to the naked eye, similar to smoke in air..."

What am I getting at?

Well, think about a body of water like the Rio Negro, as pictured above in the photo by Mike Tuccinardi. This water is of course, "tinted" because of the dissolved tannins and humic substances that are present due to decaying botanical materials.

That's different from "cloudy" or "turbid", however.

It's a distinction that neophytes to our world should make note of. The "rap" on blackwater aquariums for some time was that they look "dirty"- and this was largely based on our bias towards what we are familiar with. And, of course, in the wild, there might be some turbidity because of the runoff of soils from the surrounding forests, incompletely decomposed leaves, current, rain, etc. etc.

in the wild, there might be some turbidity because of the runoff of soils from the surrounding forests, incompletely decomposed leaves, current, rain, etc. etc.

None of the possible causes of turbidity mentioned above in these natural watercourses represent a threat to the "quality", per se. Rather, they are the visual sign of an influx of dissolved materials that contribute to the "richness" of the environment. It's what's "normal" for this habitat. It's the arena in which we play in our blackwater, botanical-style aquariums, as well.

Mental shift required.

Obviously, in the closed environment that is an aquarium, "stuff" dissolving into the water may have significant impact on the overall quality. Even though it may be "normal" in a blackwater environment to have all of those dissolved leaves and botanicals, this could be problematic in the closed confines of the aquarium if nitrate, phosphate, and other DOC's contribute to a higher bioload, bacteria count, etc.

Again, though, I think we need to contemplate the difference between water "quality" as expressed by the measure of compounds like nitrate and phosphate, and visual clarity.

So...we have to separate out the way our water tests from the way it looks.

My hypothesis:

Our aesthetic "upbringing" in the hobby seems to push us towards "crystal clear" water, regardless of whether or not it's "tinted" or not. And we associate clarity with quality.

A definite "clear water bias!"

And that's okay.

However, I think it's important to consider these factors in context. Particularly, in the context of the natural systems that we want to replicate in the aquarium.

And, yeah- it makes sense to consider the roles of botanicals in this process, too.

As we've discussed before, the soils, plants, and surrounding geography of an aquatic habitat play an important and intricate role in the composition of the aquatic environment. They influence not only the chemical characteristics of the water (like pH, TDS, alkalinity), but the color (yeah- tannins!), turbidity, and other characteristics, like the water flow. Large concentrations become physical structures in the course of a stream or river that affect the course of the water.

And of course, they also have important impact on the diet of fishes...Remember allochthonous input form the land surrounding aquatic habitats? And the impact of humic substances?

I can't help but wonder what sorts of specific environmental variations we can create in our aquarium habitats; that is to say, "variations" of the chemical composition of the water in our aquarium habitats- by employing various different types and combinations of botanicals and aquatic soils.

I mean, on the surface, this is not a revolutionary idea...We've been doing stuff like this in the hobby for a while- more crudely in the fish-breeding realm (adding peat to water, for example...), or with aragonite substrates in Africa Rift Lake cichlid tanks, or with mineral additions to shrimp habitats, etc.

In the planted aquarium world, it's long been known that soil types/additives, ie; clay-based aquatic soils, for example, will obviously impact the water chemistry of the aquarium far differently than say, iron-based soils. And thusly, their effect on the plants, fishes, and, as a perhaps unintended) side consequence, the overall aquatic environment will differ significantly as a result.

This is an area that I think we'll see much more work being done on in coming months/years. It really pushes us to think a bit differently and to apply unconventional solutions to our aquarium work.

Letting go of some long-held ideas and mindsets, and looking at Nature as an inspiration in both form AND function, as opposed to just looking at "the other guy's tank" for ideas, will pave the way for a new generation of natural-style biotope aquariums that will evolve and change the state of the art of our hobby for many years to come.

I think that, with a greater understanding of the types of environments our animals come from, that this "clinical sterility standard" for water and overall aesthetics of our systems will change. The movement towards biotopes and more naturally-appearing- and functioning- systems has opened the eyes of many aquarists to the amazing possibilities that exist when we move beyond our previously self-imposed limitations.

There's a lot of work to do here.

Stay resourceful. Stay open-minded. Stay curious. Stay creative...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

"Weather"...or not?

No force in the natural habitats of our fishes contributes more to their emergence, growth, and reproduction as the weather. It influences almost every aspect of their environment, from water chemistry to temperature, to light intensity.

So, think about weather for just a second, and then contemplate it's potential role in our aquariums. In our aquariums, we model so many aspects of the natural habitats that we are intrigued with, yet one of the most "in our face", yet seldom-considered is the impact that seasonal changes-driven by weather- have on the biotopes we are interested in.

Yeah...you know, the "wet season" and the "dry season." Both create profoundly different circumstances which affect the habitat, the conditions, and the fishes themselves. What an interesting element to consider when creating or managing an aquarium, right?

In the Amazon, the wettest part of the wet season occurs between December and May. During the wet season, the Amazon rainforest receives as much as 6 to 12 feet of rain (1.98- 3.6m), which can cause rivers like the Amazon to rise as much as 40 feet (12m), flooding the surrounding forest areas! The fishes adapt by moving into these areas that were previously barren and dry, foraging among the now-submerged trees, grasses, and plants.

We know this, and we spend a great deal of time in our community attempting to replicate this dynamic season in our aquariums. It's one of the types of habitats I think we love duplicating the most around here, for sure.

What about the "dry season?" When the water level is lower, the nutrient levels might be a bit higher. What happens in nature that we might be able to duplicate in our aquariums, and what dynamics can we bring to our closed systems as a result?

For one thing, recent studies have shown that rainforest trees and plants actually "flush" (grow new leaves) shortly before the arrival of the dry season. It's postulated that there is something in their "genetic programming" that allows them to prepare for the onset of the relatively "light-rich" dry season, to get them ready for enhanced photosynthetic activity.

"light rich..."

So, the takeaway here for aquarists who want to replicate the "dry season?" I'm thinking more leaves and botanicals in the water...brighter lighting. Yeah, even the dry season could be replicated in an interesting manner in our aquariums...Perhaps ( I can hear the alternating moans and cheers from different corners now!) less frequent water exchanges, higher light intensities (yes, ANOTHER reason to utilize LEDs in your tank!), and maybe even less frequent feedings...

These are just a few small "edits" we can make to the configuration and management of our natural, biotope-inspired aquariums. "Edits" which aim to recreate a very different part of the ecosystem than we typically will tackle as aquarists.

Simple modifications to our operating practices which can create potentially profound and significant breakthroughs as we learn more and more about our fishes and the environments from which they come.

And these "seasonal changes" are just a few of the many, many different ways to replicate natural process in our aquariums!

What's next? How can we utilize this interesting replication of Nature for our fishes' advantage in our setups? What secrets can be unlocked when we look to replicate weather on some level?

Stay studious. Stay fascinated. Stay intrigued. Stay creative. Stay inspired. Stay unique...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Philosophy, tint, and transience...

With our aquarium work, we marry art, science, and, yeah- philosophy. An important mix, really.

In its most simplistic and literal form, the Japanese philosophy of "Wabi Sabi" is an acceptance and contemplation of the imperfection, constant flux and impermanence of all things.

This philosophy was been embraced in aquascaping circles by none other than the late, great, Takashi Amano, who proffered that a planted aquarium aquascape is in constant flux, and that one needs to contemplate, embrace, and enjoy the sweet sadness of the transience of life.

This is a fascinating and meaningful philosophy, IMHO.

Many of Amano's greatest works embraced this philosophy, and evolved over time as various plants would emerge, thrive, spread and decline, re-working and reconfiguring the aquascape with minimal human intervention. Each phase of the aquascape's existence brought new beauty and joy to those would observe them.

This philosophy of "meeting Nature where it is" is the perfect encapsulation of what happens in an aquarium..specifically, the botanical-style systems we love. If someone pressed me to name the single most important thing you need to understand and embrace to be successful when working in this arena, this concept would be it.

Yet, in today's "contest-scape-driven", "break-down-the-tank-after the show" world, this philosophy of appreciating change by nature over time seems to have been tossed aside as we move on to the next 'scape. Emphasis has been placed on the production of a "product" or "finished work" in a relatively short period of time, versus allowing something to evolve. And yeah, the three-month "pre contest period" before you take pics and submit is NOT allowing your tank to evolve. It's just a start.

It goes for any tank, IMHO. These things take time. Patience. Observation. Appreciation. Changes caused by Nature are often subtle, maybe barely perceptible- but they're happening. We need to train ourselves to be attuned to them.

When we use natural botanical materials in our aquatic hardscape, such as leaves and softer botanicals, which begin to degrade after a few weeks submerged, one can really understand the practicalities of this philosophy. It could be argued, that the use of botanicals in an aquarium and embracing the progression is the very essence of what "Wabi Sabi" is about.

I love that the mainstream aquarium wold is looking at this stuff more seriously. However, with hobbyists worldwide getting interested in blackwater, botanical-style tanks, and more and more aquatics vendors starting to offer "botanicals" sections on their web sites, I think that we have to ask ourselves, "Why are we doing this?"

Is it because this is suddenly "cool?" Because it's a way to have a "hip and trendy-looking" tank? Is it because somebody told us to do it? Or is it perhaps something else?

Are we as a hobby understanding that this type of tank goes way, way beyond the "typical" purely aesthetic-driven scapes that have been "the thing" for the last couple of decades? The "functional aesthetic" concept that we embrace here is really the cornerstone of this "movement" in the hobby.

It starts with the way we "configure" our aquascapes. How we "set them up" to follow Nature's course, rather than fight it.

I've always personally felt that, in a botanical-style aquarium, a hardscape should have some more-or-less "permanent" materials, like driftwood, complemented by some of the more durable botanicals, like Cariniana pods or Sterculia pods, and enhanced by more "degradable" items, like as the "softer" seed pods and such, and finally, complimented by the use of leaves- which are perhaps the most "ephemeral" component of the botanical-style aquarium, and need replenishment/replacement over time.

As we know, natural botanical materials not only offer very unique natural aesthetics- they offer literal "enrichment" of the aquatic habitat through their release of tannins, humic acids, vitamins, etc. as they decompose- just as they do in nature.

This is a pretty amazing thing.

Much like flowers in a garden, leaves will have a period of time where they are in all their glory, followed by the gradual, inevitable encroachment of biological decay. At this phase, you may opt to leave them in the aquarium to enrich the environment further (providing food for fungi, bacteria, and other fauna), and offer a different aesthetic, or you can remove and replace them with fresh leaves and botanicals.

This very much replicates the process which occur in nature, doesn't it?

With the publishing of photos and videos of leave-influenced 'scapes in the past few years, there has been much interest and more questions by hobbyists who have not really considered these items in an aquascape before. This is really cool, because new people with new ideas and approaches are actively experimenting. And, perhaps most important of all- we're looking at nature as never before. We're celebrating the real diversity and appearance of natural habitats as they really are...

Some hobbyists have commented that, as their leaves and botanicals break down and the scape as initially presented changes significantly over time. Weather they know it or not, they are grasping "Wabi-Sabi"...Well, sort of. One must appreciate the beauty at various phases to really grasp the concept and appreciate it. To find little vignettes- little moments- of fleeting beauty that need not be permanent to enjoy.

And of course, there are always some people who just "don't get it", and proffer that this is simply sloppy, not thought-out, and seemingly random approach to aquarium keeping. I recall vividly one critic on a Facebook forum, who, observing a botanical-inspired aquascape created by another hobbyist, commented that the 'scape looked like "...someone just threw in some pods and leaves in a random fashion.."

Yeah, this guy actually did superficially describe the aesthetic to a certain (although very unsophisticated) degree...but he couldn't get past the superficial assessment of the look, which was in conflict with his personal taste, and therefore concluded it was, "...haphazard, sloppy, and not thought out."

Had he ever actually been to, or seen pictures of, a natural aquatic habitat? I couldn't help but wonder. The lack of ability to get out of this head space that "natural" = sloppy, poorly thought out, and unsophisticated.

Ouch.

But on the other hand, that sort of random, almost "deconstructed" look was the charm and beauty of the tank in question. The seemingly transient nature of such an aquascape, with leaves deposited as in nature by currents, tidal flows, etc., settling in unlikely areas within the hardscape is beautiful.

Not everyone likes this nor appreciates it. Or understands it. And that's perfectly fine. Not everyone finds brown water, decomposing leaves, biofilms, and detritus beautiful. A lot of aquarists just sort of shrug. Some even laugh. Some love to criticize.

It's not the "best" way to run a tank. Just "a way."

Some want "rules." Order. Guidelines from experts.

We offer no "rules."

We can only offer an assessment of what Nature does to an aquarium when it's set up a certain way. We can only point out the way Nature looks and study how it functions, and perhaps offer some hints on how to embrace the processes which it utilizes.

There are no real "rules" when creating a blackwater/botanical-style aquarium, other than the biological aspects of decomposition and water chemistry, which are the real factors that dictate just how your aquascape will ultimately evolve.

Accepting this inevitable change and imperfection is the very essence- and beauty- of the "Wabi-Sabi" principle, IMHO.

It's about observation. Dedication. Imagination. Individuality. And the mindset of meeting Nature where it is.

Stay contemplative. Stay observant. Stay curious. Stay inquisitive. Stay patient. Stay unique...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Putting the "botanical puzzle" together...

It's been an interesting journey in the first four years of our existence here at Tannin. With your support and enthusiasm, we've recruited a global community of natural-style botanical aquarium enthusiasts who are pushing the boundaries of the science and art of aquarium keeping.

We've started with some simple ideas, inspired by Nature, and have slowly refined our skills as a community, moving on towards more and more complex and boundary-pushing ideas. Once tentative about using seed pods, leaves, and twigs to influence the environmental parameters of our tanks, we're now using them to more realistically recreate natural habitats than ever before.

Confidence is high, boosted by experience and success- and replicable results.

It's like we're slowly but surely accumulating the experience and knowledge to put various pieces of this compelling puzzle together- and hopefully, having lot of fun and inspiring others as we do so!

Inspiration and fun are the keys. Education and experience are the lovely by-products of our efforts as a community.

As a group, we're elevating the use of natural materials- not just to create an aesthetic- but to foster natural behaviors in our fishes and function in our aquariums. These aspects have driven many of us to look at Nature as a source of true inspiration for many aspects of this work.

We're "editing" previously long-held assumptions and ways of doing things to evolve our practices to be much more like what Nature is, as opposed to simply replicating the look of last year's aquascaping contest winner.

And the results are both functional and attractive! And educational, as well!

And there are as many questions as answers. Among the most common? They're about plants.

Specifically, how to use them in our specialized aquariums.

We get a lot of questions about the types of plants that exist in the igapo (blackwater flooded forest) and varzea ("white-water" flooded forest) habitats that we obsess over so much- what species would work in our aquariums, etc. The interesting thing is that a high percentage of species which occur in this habitat are NOT true aquatics:

"Among the 388 herbaceous species identified in the floodplain areas of Rio Amazonas 330 species (85%) were classified as terrestrial plants, 34 (9%) aquatic plants and the 22 remaining (6%) as intermediary species." (Junk and Piedade, 1993a)

So, yeah, if you want to truly replicate the igapo, you're going to have to utilize some terrestrial plants- mainly grasses, which form dominant, monospecific stands, such as Echinochloa polystachya, Paspalum fasciculatum, and Paspalum repens.

Now, these are the exact species...one could find representative species from these genera available as seeds. And, you could plant them, and...well. It takes a LOT of patience and time...

Oh, and there are true aquatic plants which are found in some of these flooded igapo habitats. Species which we might have some hobby familiarity with. In fact, common species found at the igapós of rio Negro are: Oryza perennis, Nymphaea rudgeana, Polygonum sp., Utricularia foliosa, and- wait for it...our old friend, Cabomba aquatica!

Yeah, so there are true aquatic plants in some of these habitats, although the bulk of what we see in many of those breathtaking underwater shots are terrestrial grasses and shrubs which can withstand inundation. Think on that just a bit.

Much still to learn and practice and perfect as we solve this great "puzzle!"

I kind of like where we're going in our botanical aquarium habitat-replication journey, and where we've already been. So far, we've "proof- of-concepted" a 100% leaf-litter habitat with tremendous success. It works fantastically, is a completely different aesthetic than anything we've done before, and has enormous potential.

We've also played with the idea of replicating a tangle of roots, as one sees in the igapo and varies habitats. The web of life that exists in this habitat is awe-inspiring!

This has also proven to be an amazing "look" and has a functional aspect to it that we're still working with. My (now 6 month old) "Tucano Tangle" featuring roots and the enigmatic Tucanoichthys tucano is still teaching me new lessons on the "functional aesthetic" aspect of this habitat in the aquarium.

Next, it's on to incorporating all that we've played with...Leaves, wood, sediments, roots, and immersion-tolerant terrestrial plants.

Much to be learned. Much to be inspired by.

Keep looking to Nature for inspiration. I know that I am!

Stay unique. Stay challenged. Stay bold. Stay observant. Stay resourceful...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Cooking with botanicals: The art of botanical preparation- Part 236...

Why do we boil stuff that we add to our aquariums in the first place?

Yeah, it's THE single most common question that we're asked here at Tannin, and has been the starting point for I-don't-know-how-many discussions over the years! So, let's touch on it again!

Why, Scott? Why do we boil this stuff?

Well, to begin with, consider that boiling water is used as a method of making water potable by killing microbes that may be present. Most nasty microbes "check out" at temperatures greater than 60 °C (140 °F). For a high percentage of microbes, if water is maintained at 70 °C (158 °F) for ten minutes, many organisms are killed, but some are more resistant to heat and require one minute at the boiling point of water. (FYI the boiling point of water is 100 °C, or 212 °F)...But for the most part, most of the nasty bacteria that we don't want in either our tanks or our stomachs are eliminated by this simple process.

Ten minutes of boiling is "golden", IMHO. Of course, we boil for other reasons, as we'll touch on in a bit.

For one reason, we boil botanicals to kill any possible microorganisms which might be present on them. Leaves, seed pods, etc. have been exposed to rain and dust and all sorts of things in the natural environment which, in the confines of an aquarium, could introduce unwanted organisms and contribute to the degradation of the water quality.

The surfaces and textures of many botanical items, such as leaves and seed pods lend themselves to retaining dirt, soot, dust, and other atmospheric pollutants that, although likely harmless in the grand scheme of things, are not stuff you want to start our with in your tank.

So, we give all of our botanicals a good rinse.

Then we boil.

Boiling also serves to soften botanicals.

If you remember your high school Botany, leaves, for example, are surprisingly complex structures, with multiple layers designed to reject pollutants, facilitate gas exchange, drive photosynthesis, and store sugars for the benefit of the plant on which they're found. As such, it's important to get them to release some of the materials which might be bund up in the epidermis (outer layers) of the leaf. As we get deeper into the structure of a leaf, we find the mesophyll, a layer of tissue in which much of photosynthesis takes place.

We use only dried leaves in our botanical style aquariums, because these leaves from deciduous trees, which naturally fall off the trees in seasons of inclement weather, have lost most of their chlorophyll and sugars contained within the leaf structures. This is important, because having these compounds present, as in living leaves, contributes excessively to the bioload of the aquarium when submerged...

Are there variations on this theme?

Well, sure.

Many hobbyists rinse, then steep their leaves rather than a prolonged boil, for the simple fact that exposure to the newly-boiled water will accomplish the potential "kill" of unwanted organisms, which at the same time softening the leaves by permeating the outer tissues. This way, not only will the "softened" leaves "go to work" right away, releasing the beneficial tannins and humic substances bound up in their tissues, they will sink, too!

And of course, I know many who simply "rinse and drop", and that works for them, too! And, I have even played with "microwave boiling" some stuff (an idea forwarded on to me by Cory Hopkins!). It does work, and it makes your house smell pretty nice, too!

It's not a perfect science- this leaf preparation "thing."

However, over the years, aquarists have developed simple approaches to leaf prep that work with a high degree of reliability. Now, there are some leaves, such as Magnolia, which take a longer time to saturate and sink because of their thick waxy cuticle layer. And there are others, like Loquat, which can be undeniably "crispy", yet when steeped begin to soften and work just fine.

So why do we soak after boiling?

Well, it's really a personal preference thing.I suppose one could say that I'm excessively conservative, really.

I feel that it releases any remaining pollutants and undesirable organics that might have been bound up in the leaf tissues and released by boiling, which is certainly arguable, but is also, IMHO, a valid point. And since we're a company dedicated to giving our customers the best possible outcomes- we recommend being conservative and employing the post-boil soak.

The soak could be for an hour or two, or overnight...no real "science" to it. Some aquarists would argue that you're wasting all of those valuable tannins and humic substances when you soak the leaves overnight after boiling. My response has always been that you might lose some, but since the leaves have a "lifespan" of weeks, even months, and since you'll see tangible results from them (i.e.; tinting of the water) for much of this "operational lifespan, an overnight soak is no big deal in the grand scheme of things.

Do what's most comfortable for you- and okay for your fishes.

When it comes to to other botanicals, such as seed pods, the preparation is very similar. Again, most seed pods have tougher exterior features, and require prolonged boiling and soaking periods to release any surface dirt and contaminants, and to saturate their tissues to get them to sink when submerged!

And quite simply, each botanical item "behaves" just a bit differently, and many will require slight variations on the theme of "boil and soak", some testing your patience as they may require multiple "boils" or prolonged soaking in order to get them to saturate and sink.

Yeah, those damn things can be a pain!

However, I think the effort is worthwhile.

Now, sure, I hear tons of arguments which essentially state that "...these are natural materials, and that in Nature, stuff doesn't get boiled and soaked before it falls into a stream or river." Well, damn, how can I argue with that? The only counterargument I have is that these are open systems, with far more water volume and throughput than our tanks, right? Nature might have more efficient, evolved systems to handle some forms of nutrient excesses and even pollution. It's a delicate balance, of course.

In the end, preparation techniques for aquatic botanicals are as much about prevention as they are about "preparation." By taking the time to properly prepare your botanical additions for use in the aquarium, you're doing all that you can to exclude unwanted bacteria and microorganisms, surface pollutants, excess of sugars and other unwelcome compounds, etc. from entering into your aquarium.

Like so many things in our evolving "practice" of perfecting the blackwater, botanical-style aquarium, developing, testing, and following some basic "protocols" is never a bad thing. And understanding some of the "hows and whys" of the process- and the reasons for embracing it-will hopefully instill into our community the necessity- and pleasures- of going slow, taking the time, observing, tweaking, and evolving our "craft"- for the benefit of the entire aquarium community.

The practice of botanical-style aquariums is still very much "open source"- we're all still writing the "best practices"- and everyone is invited to contribute!

Stay engaged. Stay fascinated. Stay observant. Stay excited. Stay involved...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

"Wood" you believe this?

As an aquarist who derives great pleasure from seeing his fishes "live off the land" and consume foods from the aquarium environment in which they reside, I really find some of the underlying feeding strategies fascinating. One of the best examples is the consumption of wood by various species of fishes.

We read a lot about fishes which eat wood and wood-like materials. Of course, the ones that come immediately to mind are the Loricariidae, specifically, Panaque species. Now, I admittedly am the last guy who should be authoritatively discussing the care of catfishes, but I do understand a little bit about their diets and the idea of utilizing wood- and botanical materials- in the aquarium for the purpose of supplementing their diets!

And of course, I'm fascinated by the world of biofilms, decomposition, microorganism growth and detritus...And this stuff plays right into that!

Now, the idea of xylophagy (the consumption and digestion of wood) is of course, a pretty cool and interesting adaptation to the environment from which these fishes come from. And as you'd suspect, the way that wood is consumed and digested is equally cool and fascinating!

It's thought that the scraping teeth and highly angled jaws of the Loricariidae are a perfect adaptation to this feeding habit of scraping wood. And of course, it's even argued among scientists that these fishes may or may not actually digest the wood they consume! While scientists have identified a symbiotic bacteria which is found in the gut of these fishes that helps break down wood components, it's been argued by some the the fishes don't actually digest and metabolize the wood; indeed deriving very little energy from the wood they consume!

In fact, a lab study by Donovan P. German was described in the November, 2009 Journal of Comparative Physiology, in which several species were fed wood and found to actually digest it quite poorly:

"...in laboratory feeding trials, (P. cf. nigrolineatus and Hypostomus pyrineusi) lost weight when consuming wood, and passed stained wood through their digestive tracts in less than 4 hours. Furthermore, no selective retention of small particles was observed in either species in any region of the gut. Collectively, these results corroborate digestive enzyme activity profiles and gastrointestinal fermentation levels in the fishes’ GI tracts, suggesting that the wood-eating catfishes are not true xylivores such as beavers and termites, but rather, are detritivores like so many other fishes from the family Loricariidae."

Did you see that? Detritioves.

Hmm...

And this little nugget from the same study: "...The fishes consumed 2–5% of their body mass (on a wet weight basis) in wood per day, but were not thriving on it, as P. nigrolineatus lost 1.8 ± 0.15% of their body mass over the course of the experiment, and Pt. disjunctivus lost 8.4 ± 0.81% of their body mass."

Yet, anatomical studies of these fishes showed that the "wood-eating catfishes" had what physiologists refer to as "body size-corrected intestinal lengths" that were 35% shorter than the detritivore species. What does this mean? Could they have perhaps had at one time- and subsequently lost- their ability to digest wood?

Maybe?

Arrgh!

To the point of the argument that they are primarily detritivores, consuming a matrix of biofilm, algal growth, microorganisms, and (for want of a better word) "dirt"- what does this mean? In fact, many species in the Loricariidae are known to be detritivores, and this has made them remarkably adaptable fishes in the aquarium.

Now, my personal experience with Loricariidae is nothing like many of yours, and an observation I made not too long ago is at best anecdotal- but interesting:

If you follow "The Tint", you know I've had an almost two year love affair with my Peckolotia compta aka "L134 Leopard Frog"- a beautiful little fish that is filled with charms. Well, my specimen seemed to have vanished into the ether following a re-configuration/rescape of my home blackwater/botnanical-style aquarium. I thought somehow I either lost the fish during the escape, or it died and subsequently decayed without my detecting it...

For almost three months, the fish was M.I.A., just....gone.

And then one, day- there she was, poking out from the "Spider Wood"thicket that forms the basis of my newer hardscape! To say I was overjoyed was a bit of an understatement, of course! And after her re-appearance, she was been out every day. She looked just as fat and happy as when I last saw her in the other 'scape...which begs the question (besides my curiosity about how she evaded detection)- What the @#$% was she feeding on during this time?

Well, I suppose it's possible that some bits of frozen food (I feed frozen almost exclusively) got away from my population of hungry characins and fell to the bottom...However, I'm pretty fastidious- and the other fishes (characins) were voracious! I think it was more likely the biofilm, fungal growth, and perhaps some of the surface tissues of the "Spider Wood" I used in the hardscape that she was feeding on.

This stuff does recruit some biological growth on it's surfaces, and curiously, in this tank, I noticed during the first few months that the wood seemed to never accumulate as much of this stuff as I had seen it do in past tanks which incorporated it.

I attributed this to perhaps some feeding by a population of Nanostomus eques, which have shown repeatedly in the past to feed on the biofilm or "aufwuchs" accumulating on the wood.

And as an interesting side observation, this wood (so-called "Blonde" Spider Wood) actually darkens and develops a sort of "patina" of biofilms and such over time, which probably facilitates the feeding, right?

There was also a layer of Live Oak leaves distributed throughout the booth of the wood matrix, which, although they break down very slowly compared to other leaves we use, DO ultimately soften over time and break down over time.

Interestingly, in this tank, I was finding little tiny amounts of very broken-down leaves, which I attributed to decomposition, but thinking back on it, looks more like the end product of "digestion" by someone!

I must admit, I don't think I've ever seen my L134 consuming prepared food. I've always seen her rasping away at the wood surfaces and on botanicals...That's all the proof I needed to confirm my theory that she's pretty much 100% detritivorous, and that the botanical-style aquariums she's resided in provide a sufficient amount of this material for her to consume.

SO, back the the whole "xylophore thing"...I think that in the aquarium, as well as in the wild, much of what we think is actually "consumption" of the wood is simply incidental, as in, the fishes are trying to eat the biocover and detritus on the surface tissues of the wood, but do a pretty good job (with their specialized mouthparts) of rasping away the surface tissues as well.

Some of the wood may pass through the digestive tract of the catfishes, but it's passed without metabolizing much from it...perhaps like the way chickens consume gravel, or whatever (don't they? City boy here!)...or the way some marine Centropyge angelfishes "nibble" on corals in their pursuit of algae, detritus, and biofilms.

Again, my perusal of German's scientific paper seems to support this theory:

"Catfishes supplement their wood diet with protein-rich detritus, or even some animal material to meet their nitrogen requirements. Although I did not observe animal material in the wood-eating catfish guts, Pt. disjunctivus did consume some animal material (including insects parts, molluscs, and worms), and all three species consumed detritus."

And finally, the "clincher", IMHO: "The low wood fiber assimilation efficiencies in the catfishes are highly indicative that they cannot subsist on a wood only diet."

Boom.

I mean, it's just one paper, but when he's talking about isotopic tracing of materials not consistent with digestion of wood in the guts of Loricariids, I think that pretty much puts the "eats wood" thing to bed, right? His further mention that, although some cellulose and lignin (a component of wood and our beloved botanicals!) was detected in the fish's fecal material, it was likely an artifact of the analysis method as opposed to proof that the fishes derived significant nutrition from it.

So what does all of this stuff mean to us?

Detritus/biofilm/fungal growths = good. Don't loathe them. Love them.

I think it means that, as hobbyists probably knew, theorized, and discussed for a long time- that the Loricariids consume detritus, biofilms, and prepared foods when available. This is not exactly earth-shattering or new. However, I think understanding that our botanical-style aquariums can- and do- provide a large amount of materials from which which these and other fishes can derive significant nutrition furthers my assertion that this type of system is perfect for rearing and maintain a lot of specialized feeders.

Materials like the harder-"shelled" botanicals (ie; Cariniana pods, Mokha pods, Sterculia pods, Catappa bark, etc.) tend to recruit significant biofilms and accumulate detritus in and on their surfaces. And of course, as they soften, some fishes apparently rasp and consume some of them directly, likely passing most of it though their digestive systems as outlined in the cited study, extracting whatever nutrition is available to them as a result. This is likely the case with leaves and softer botanicals as well.

Incidental.

The softer materials might also be directly consumed by many fishes, although the nutrition may or may not be significant. However, the detritus, fungal, and microorganism growth as a result of their decomposition is a significant source of nutrition for many fishes and shrimps.

Detritivores (of which the amount of species in the trade is legion), have always done very well in botanical-style aquariums, and the accumulation of biofilms and microbial growth is something that we've discussed for a long time. By their very nature, the decomposition and accumulation of botanical materials make the "functional aesthetics" of our aquariums an important way to accommodate the natural feeding behaviors of our fishes.

So, the answer to the question (literally!), "Who has the (literal) guts for this stuff?" is quite possibly, "everyone!"

I mean, what aquarist doesn't love the grazers, detritovres, and opportunistic omnivores?

Stay studious. Stay curious. Stay observant. Stay engaged. Stay resourceful...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Letting go...for a little while, anyways.

If you are like oh, 80% of the hobbyists out there, you tend to work pretty damn hard to make sure that you're doing all that you can for your fishes to keep them healthy and their environment stable. Of course, on occasion, life gets busy, and you might have stretches of times where you're simply not able to take care of your aquarium(s) as perfectly as possible.

Life happens.

With our botanical-focused natural aquariums, what happens when say, we skip a water exchange or two, a filter media replacement, or if we can't feed as often as we used to, or..?

Is it a big problem?

I mean, you have a tank filled with a significant amount of slowly decomposing leaves, botanicals, etc., which contribute the the bioload of the aquarium. That amount of material has to have some impact on water quality, right?

It does, but not always in the way you might think.

It's hardly scientific; it's more like a "common sense thing"- but if you're careful about how much botanical material you add in the first place, and how quickly you add it, the impact of all of this material is more of a positive, IMHO.

All additions of botanicals to an existing aquarium need to be measured, deliberate, slow, and considerate. You need to observe your fishes' reactions, monitor water chemistry, and stay alert to the changes and demands that botanicals will place on your aquarium. And they will. There's no mystery here. Adding a ton of stuff into any established aquarium creates environmental changes and impacts that cannot be ignored.

Are all of these impacts necessarily bad?

No, I don't think so.

If you think about it, these materials also function as a substrate- a "fuel", of sorts, for the growth of beneficial bacteria, biofilms, and other microorganisms within the aquarium. In my opinion and experience, when added gradually and methodically, you can look at all of this stuff as the biological "power station" for your tank, supporting a population of organisms which serve to break down more toxic compounds and substances via the nitrogen cycle.

I think it's sort of analogous to the use of live rock in a reef aquarium. Live rock is considered an essential component of a reef aquarium, because it serves as that aforementioned "biological filtration substrate" for the colonization of billions of gentrifying bacteria. This is something I'd like to see some more serious research on, because I think that there's "something" there.

So, what are the implications for us if our husbandry should slip now and then?

Will all of the botanical material continue to break down, keeping the water "tinted?" Will biofilms continue to colonize open surfaces? Will water chemistry swing wildly? Will phosphate and nitrate accumulate rapidly? Will the aquarium descend into chaos?

Or, will it simply continue to function as usual?

It's my belief that it will.

I mean, when you think about it, the natural, botanical-style blackwater aquarium is sort of set up to replicate a habitat where all of this stuff is taking place already. Leaves, seed pods, etc. are more-or-less ephemeral in nature, and are constantly breaking down in these environments. Decomposition, accumulation of epiphytic growth, and colonization of various life forms is continuous. Now, I realize that an aquarium is NOT an open system, but for the sake of this little section of the habitat- the substrate, there are many functional analogies if you study it carefully.

How much more will things change by simply delaying water exchanges for several weeks? By not siphoning detritus at all? Will this really become some sort of problem? Or, will the bacteria, fungal growths, and other microorganisms and crustacean life living in our botanical substrates continue to do what they do- break down organic waste and reproduce?

I think they will.