- Continue Shopping

- Your Cart is Empty

The "startup" phase and its natural analogies...

It's largely for "business purposes", but it seems like I've set up more aquairums in the past year than I have in the previous 2-3 years. Seems like every month I have something new going up- or about to!

And of course, being a fish geek- even when its for "business" purposes (ie; sharing some new and inspirational ideas)- it's still incredibly fun and educational. I get new insights about aquariums- and the natural habitats which inspire them- every time I set one up!

When you think about it sort of analytically, one of the neat things about setting up a new aquarium is that, like it or not- you go through the time-honored traditions of stuff as mundane as washing sand, setting in heaters and lights, cleaning and preparing wood and other hardscape materials, etc. You can't escape most of those tasks.

Nor should you want to.

I mean, unless you're using "live" material from an existing tank or pond, you pretty much have to rinse sand...whatever technique you use, it's almost unavoidable. And that often creates lingering cloudiness that simply takes a bit of waiting to resolve. And then there is what I like to call "the settling period", also jokingly referred to by us patient types as the "calm before the storm"- that period of a few days when you let everything sort of "sit" for a bit- allowing the water to clear, any bubbles to be mitigated, etc.

I actually love this period of time, because it's the last point in my tank's existence that it's "sterile"- before we begin preparing the "biological" part of the system.

You know, getting the wood and stones positioned right, making sure that the basic water parameters (alkalinity, pH, TDS, etc.) are where you want them before you start "seeding" the system with bacteria, or whatever your technique is to make your tank "come alive." This is an exciting time-a time to really make sure that things are running how you'd like them, to assure yourself that the basic hardscape is positioned how you think it should be, and that the system is "mechanically" running reliably.

It's a very exciting time. And, when viewed with the correct mindset, it's as gratifying, fascinating, and enjoyable as any other period of time in the life of your tank.

I recently considered all of these thoughts as I went through this period right now in my new home blackwater aquarium, and it's a very "contemplative" time, too- if you make it that way...and of course, I always tend to, lol.

I find myself viewing this time as a real chance to "get things right"- that time to deploy a lot of patience and ask myself those honest questions, like, "Is this EXACTY how you want those pieces of wood positioned?" or ,"Do you want to use those rocks in those positions?" OR, "Do I even WANT to use rocks..?" Like, I hate "editing" my hardscape as I go, so to me, once I start "going biological" with a tank, the "honeymoon" is over...

Those pieces of wood and rock are staying in those exact positions until either I knock them out of position during maintenance (that never happens, right?) or I break down the tank. Yeah, I'm pretty hardcore about it!

Of course, it's also a time when I tell myself, "Okay Fellman- no turning back..." Sort of like when an airplane is committed to "rotate" for takeoff...I guess I commit to a hardscape like I run my business: Conceive. Tweak. Execute. Manage (insert- "fix disasters..." here, lol). I think that it's a lot like how Nature works...Well, sort of?

Once a tree falls, it typically moves very little, unless water movement or subsidence from the substrate alters how it's settled. And "stuff" (leaves, twigs, seed pods, etc.) accumulates around it, further "cementing" its position in the habitat.

Yes, I have a weird way of looking at stuff.

And I suppose that it's correct to acknowledge that, despite my labeling this period of time as a "sterile" period, it's really the first step of creating a "biologically active" system. I mean, wood contains all sorts of "stuff", including organic materials and probably even good old fashioned terrestrial "dirt", which fuels the growth of bacteria...despite our best efforts at "cleaning" or otherwise "preparing" it for aquarium use.

And the tannins which wood often gives off once submerged?

I mean, that's like nature's little "gift" for the "tinter!"

While the rest of the aquarium world pouts, agonizes, and generally freaks the f--- out about "the tannins 'discoloring' my water"- we see this as one of the rare "hacks"- a gift from Mother Nature to help us speed up the process of getting that visual "tint" to our water that we love so much!

Don't believe me about how the rest of the hobby reacts to this? Search like any aquatic hobby forum and look at the frantic posts from hobbyists looking for anything to help remove this dreaded "scourge" of tint from their aquariums. I know, I shouldn't be so callous and unsympathetic to their "plight"- but if these heathens only knew what they were missing...

I mean, I get frantic emails from customers wondering how to make their tanks darker!

Shit, this is weird, huh?

So, yeah. We take our victories where we can get them, right?

Let's talk about that "biological phase", as I call it- just for s second...

Pretty much anything that we add to the aquarium contains some biological material (ie. bacteria, fungal or algal spores, etc.), right? And when they hit the water, it begins a process of growth, colonization, and proliferation that won't stop. These processes are so beneficial and important to our systems...

When we have these materials in place, the "microfaunal ecosystem" begins to "ignite" and grow. We often talk about the large influx of "nutrients" present in a new aquarium, and "immature" nutrient export systems in place to handle it. I mean, the tank plays a sort of biological "catch up" during this time, as the bacterial and fungal growths proliferate among the abundant nutrients. We might rely a bit more on mechanical and chemical filtration during this period. However, ultimately, these natural "nutrient export mechanisms" will take over.

It just takes time.

And a mindset where you're not totally obsessed with removing every bit of "dirt" or material which looks offensive. Allowing the the nitrogen cycle to really establish itself, and natural processes develop, will really "set the tone" for our botanical-style aquariums, IMHO. We shouldn't let some of the initial visual clues, like "cloudiness", biofilms, etc. compel us to whip out the siphon hose and remove every bit of the "offensive"-looking material from our tanks. Otherwise, we end up working agains the very processes that we're trying to foster in a botanical-style aquarium!

It takes patience, understanding, observation- and a vision.

And we're patient. And determined. And we understand that a botanical-style aquarium truly must "evolve" and take time to begin to blossom into a functioning little ecosystem. And we enjoy each and every stage of the "startup" process for what it is: An analog to the processes which occur in the natural habitats we want so badly to emulate. I think one of the mental "games" I've always played with myself during this process is to draw parallels between what I'm doing to prepare my tank and what happens in nature.

It kind of goes something like this:

A tree falls in the (dry) forest (Really, Fellman's riffing about trees AGAIN? Well, yeah...). Wind and gravity determine its initial resting place (you play around with positioning your wood pieces until you get 'em where you want, and in a position that holds!). A little rain falls (we spray down our hardscapes...), moistening the dry materials that abound in the substrate.

Next, other materials, such as leaves and perhaps a few rocks become entrapped around the fallen tree or its branches (we set a few "anchor" pieces of hardscaping material into the tank). Detritus settles (you know, that damn "sediment" that you get in newly setup tanks...) Then, the heavier rain comes; streams overflow, and the once-dry forest floor becomes inundated (we fill the aquarium with water).

The action of water and rain help "set" the final position of the tree/branches, and wash more materials into the area influenced by the tree (we place more pieces of botanicals, rocks, leaves, etc. into place). The area settles a bit, with occasional influxes of new water from the initial rainfall (we make water chemistry tweaks and maybe a top-off or two, as needed).

Fungi, bacteria, and insects begin to act upon the wood and botanicals which have collected in the water (kind of like what happens in our tanks, huh? Yes- biofilms are beautiful...). Gradually, the first fishes begin to follow the food and populate the area (we add our first fish selections based on our stocking plan...). It continues from there. Get the picture? Sure, I could go on and on attempting to painfully draw parallels to every little nuance of tank startup, but I think you know where I'm going with this stuff...

And the thing we must deploy at all times in this process is patience.

And an appreciation for each and every step in the process, and how it will influence the overall "tempo" and ultimate success of the aquarium we are creating. When we take the view that we are not just creating an "aquatic display", but a habitat for a variety of aquatic life forms, we tend to look at it as much more of an evolving process than a step-by-step "procedure" for getting somewhere.

Do some reading on the "bioactive" processes our frog and herp friends strive to create in their beautiful vivariums and enclosures- there are many analogous and educational takeaways there!

Creating such a habitat, and fostering stuff like the development of a basic kind of "food web" is really an amazing process and is filled with potential breakthroughs for aquariums. And I think that, even if we don't consider the concept, we as hobbyists sort of have been helping develop some aspects of these "food webs" for some time now in almost every type of aquarium that we've set up...

An interesting thing to contemplate, right?

Taking the time to consider, study, and savor each phase is such an amazing thing, and I'd like to think that, as students of this most compelling aquarium hobby niche, that we can appreciate the evolution as much as the "finished product" (if there ever is such a thing in the aquarium world).

It all starts with an idea...and a little bit of a "waiting game..." and a belief in Nature; a trust in allowing the natural processes which have guided our planet and its life forms for eons to develop to the extent that they can in our aquariums.

The appreciation of this process is a victory in and of itself, isn't it?

I think it is.

And the "startup phase" of our aquariums is the key component to fostering the process. Enjoy it. Understand it. Appreciate it for what it really is...A beginning of a closed ecological system.

Stay motivated. Stay excited. Stay obsessed. Stay observant. Stay appreciative...Stay patient...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Botanical nuances...Keys to replicating wild habitats on a deeper level? Or just good guesses?

One of the best things about traveling to aquarium clubs around the world is getting to meet all sorts of interesting hobbyists. And one of the things that I'm struck by- besides the sheer number of unusual things that my fellow fish geeks are into- is a tremendous fascination with the ecosystems from which many of these fishes that we play with come from. This comes up again and again! I was speaking at a club this weekend in Washington D.C.- a club with tremendously experienced hobbyists, and the open-mindedness and fascination with this "botanical-style-aquarium-thing" was really exciting and stimulating.

One of the topics which kept coming up during and after our ensuing conversations was thinking on a deeper level about how to more faithfully replicate the natural habitats of many of the fishes that we love so much. And of course, the the idea that there are all sorts of interesting influences on these natural habitats created by the surrounding terrestrial environment and the microbial associations which occur in the substrates, leaves, wood, and other materials which comprise them.

The relationship between terrestrial habitats and the aquatic environment is becoming increasingly apparent- particularly in areas in which blackwater is found. And, the lack of suspended sediments, which create a "nutrient poor" condition in these habitats, doesn't do much to facilitate "in situ" production of aquatic food sources; rather, it places the emphasis on external factors.

Many blackwater systems are simply too poor in nutrients to offer alternative food sources to fishes.The importance of the relationship between the fishes and their surrounding terrestrial habitat (i.e.; the forests which are inundated seasonally) is therefore obvious. That likely explains the significant amount of insects and other terrestrial food sources that ichthyologists find during gut content analysis of many fishes found in these habitats.

And, as we've hinted on previously- the availability of food at different times of the year in these waters also contribute to the composition of the fish community, which varies from season to season based on the relative abundance of these resources.

Another example of these unique interdependencies between land and water are when trees fall.

It’s not uncommon for a tree to fall in the rain forest, with punishing rain and saturated ground conspiring to easily knock over anything that's not firmly rooted. When these trees fall over, they often fall into small streams, or in the case of the varzea or igapo environments in The Amazon that I'm totally obsessed with, they fall and are submerged in the inundated forest floor when the waters return.

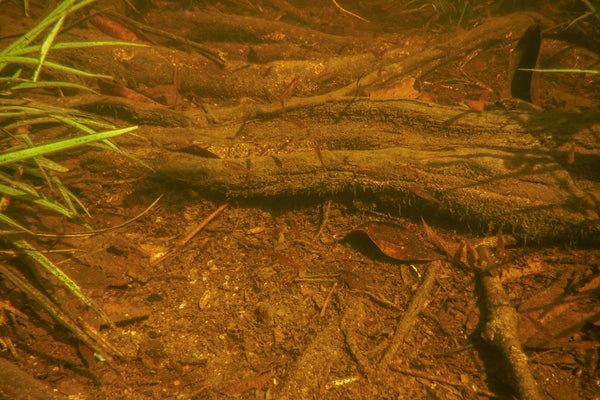

And of course, they immediately impact their (now) aquatic environment, fulfilling several functions: Providing a physical barrier or separation from currents, offering territories for fishes to spawn in, providing a substrate for algae and biofilms to multiply on, and providing places for fishes forage among, and hide in. An entire community of aquatic life forms uses the fallen tree for many purposes. And the tree trunks and parts will last for many years, fulfilling this important role in the aquatic ecosystems they now reside in each time the waters return.

In nature, as we've discussed many times-leaf litter zones comprise one of the richest and most diverse biotopes in the tropical aquatic ecosystem, yet until recently, they have seldom been replicated in the aquarium. I think this has been due, in large part- to the lack of continuous availability of products for the hobbyist to work with, and a lack of real understanding about what this biotope is all about- not to mention, the understanding of the practicality of creating one in the aquarium.

Long-held fears and concerns, such as overwhelming our systems with biological materials, and the overall "look" of decomposing leaves and botanicals in our tanks, have understandably led to this idea being relegated to "sideshow status" for many years. It's only been recently that we've started looking at them more objectively as ecological niches worth replicating in aquariums.

The function of this habitat can best be summarized in this interesting except from an academic paper on Amazonian Blackwater leaf-litter communities by biologist Peter Alan Henderson, one that is useful for those of us attempting to replicate these communities in our aquaria:

"..life within the litter is not a crowded, chaotic scramble for space and food. Each species occupies a sub-region defined by physical variables such as flow and oxygen content, water depth, litter depth and particle size…

...this subtle subdivision of space is the key to understanding the maintenance of diversity. While subdivision of time is also evident with, for example, gymnotids hunting by night and cichlids hunting by day, this is only possible when each species has its space within which to hide.”

In other words, different species inhabit different sections of the leaf litter, and we should consider this when creating and stocking our biotope systems...Neat stuff!

So, beyond just creating an aggregation of material which imparts tannins and humic substances into the water in our tanks, we're creating a little habitat, every bit as interesting, diverse, and complex as any other we attempt to replicate. In the aquarium, you need to consider both practicality AND aesthetics when replicating this biotope.

A biotope that deserves your attention and study, indeed.

And of course, if you wanted to split hairs and really parse this stuff out, you'd probably wonder which specific leaves, seed pods, etc. are found in the habitat of the fish you[re interested in keeping. This makes perfect sense...You're likely thinking, "If I use the exact materials found in the habitats where my fishes come from, I'll likely be imparting the same compounds in the same ratios found in Nature!" (Seriously, I bet that's exactly what you're thinking!) I've spent years trying to track down some of the plants found in these locales.

And of course, there is a little problem with that. Many are simply not available outside of their native haunts. And you could literally drive yourself crazy trying to find them! We've made a great effort trying to source leaves and other botanical materials from tropical habitats around the world, with this very premise in mind. However, we've typically had to settle for "surrogates"- leaves and such which come from plants found in the regions where our fishes come from.

This returns us to the interesting question about exactly what compounds are found in what ratios from what materials in a given aquatic habitat. And even if we could source the exact leaves or seed pods or whatever- we'd at best be guessing as to how much of what they are imparting to the water. Like, will a catappa leaf collected in February from Malaysia have the same ration of tannins, humic substances and other compounds as a catappa leaf collected in India in July under slightly different circumstances? Does it matter?

Yeah, you COULD pretty much go crazy trying to do the mental gymnastics around this stuff. The reality is that the best we can likely hope for, until some incredibly detailed analysis of the water conditions in our fave habitats is done- is to simply do our best.

Yeah, really.

Frustrating, I know. However, I suppose that, until more information is unlocked, the best thing that we can do is to utilize the materials that we have available in a quantity and variety which "feels right" to us, and seems to have a positive impact on our fishes.

And to take note of our findings; our discoveries.

These kinds of interesting little ideas can occupy the imagination of hobbyists for decades! And the fact is that most of what we are doing in our little botanical-infused world is simply a "best guess" in many cases...a true work in progress. Yet, a "work in progress" which may have some profound impact on the hobby for decades.

Isn't it exciting to be on the aquarium hobby's "bleeding edge?"

Yeah, it is.

Stay devoted. Stay curious. Stay diligent. Stay excited. Stay observant...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Starting at the bottom...

It's pretty funny to see how our world has changed a bit over the years. What was once considered completely crazy is now only seen as a bit.."odd."

Hey- progress, right? Yeah, we'll take it.

Since the inception of our company, we've been encouraging everyone to experiment with utilizing botanical materials for a variety of purposes in our blackwater/botanical-style aquariums. And one of the things we've been playing with has been the practice of mixing various botanical materials into the substrate directly.

Now, this isn't exactly a revolutionary, earth-shattering practice. However, it is something which we believe hasn't been played with outside of the "dirted tank" concept in planted aquariums. Of course, the whole idea of planted blackwater aquariums is absolutely a "thing"- something that we feel will simply be a type of aquarium that aquatic plant enthusiasts set up in the near future as a matter of practice. We've done a lot of experimenting with this as a group and I think it's more and more common all the time!

However, the idea of creating rich, diverse botanical-influenced substrates for the purpose of infusing tannins, humic substances, and other compounds- as well as creating a "matrix" for the growth and propagation of beneficial micro and microfauna. Yeah, using a botanically-infused substrate to create a unique, ecologically diverse, functional, and aesthetically interesting affect on the aquarium- even one that doesn't have aquatic plants in it- is a sort of different approach.

First off, the question of why you would do this looms large.

Well, you could start with Nature again...

If you really think about it, the "traditional" aquarium substrates of sand and gravel are essentially biologically "inert" materials, typically devoid of anything except minerals and carbonate ions that are of use to the aquarium. The real "magic" comes when we introduce life forms- or, in our practice- the materials which encourage and support biological function and diversity.

And of course, when you're talking about creating a rich substrate, consisting of decomposing organic materials (leaves, coco-fiber, and other botanicals containing lignin, etc.), that creates a matrix that may eventually consist of- and perhaps accumulate- what we'd collectively call "detritus."

Oh, my God. NOT DETRITUS!

So the ^**&%$ what? 😆

Is "detritus", or other finely processed organic material the "doomsday machine" that will destroy your aquarium?

I don't think so.

I know-we all know- that uneaten food and fish poop, accumulating in a closed system can be problematic if overall husbandry issues are not attended to. I know that it can decompose, overwhelm the biological filtration capacity of the tank if left unchecked. And that can lead to a smelly, dirty-looking system with diminished water quality. I know that. You know that. In fact, pretty much everyone in the hobby knows that.

Yet, we've sort of heaped detritus into this "catch-all" descriptor which has an overall "bad" connotation to it. Like, anything which is allowed to break down in the tank and accumulate is "bad."

We're not talking about a substrate composed entirely of uneaten food and fish poop here.

The definition as accepted in the aquarium hobby is admittedly kind of sketchy in this regard; not flattering, at the very least:

"detritus is dead particulate organic matter. It typically includes the bodies or fragments of dead organisms, as well as fecal material. Detritus is typically colonized by communities of microorganisms which act to decompose or remineralize the material." (Source: The Aquarium Wiki)

That being said, everyone thinks that it is so bad.

I'm not buying it.

Why is this necessarily a "bad" thing?

In nature, the leaf litter "community" of fishes, insects, fungi, and microorganisms is really important to the overall tropical environment, as it assimilates terrestrial material into the blackwater aquatic system, and acts to reduce the loss of nutrients to the forest which would inevitably occur if all the material which fell into the streams was washed downstream!

The key point: These materials foster the development of life forms which process these materials. Stuff is being used by life forms.

And finely-grained botanical materials not only provide a substrate upon which these organisms can grow and multiply- they provide a sort of "on board nutrient processing center" within the aquarium. In my experience, based on literally a lifetime of playing with all sorts of combinations of materials in my aquariums' substrates ('cause I've always been into that stuff!), I cannot attribute a single environmental lapse, let alone, a "tank crash", as a result of such additions.

A well-managed substrate, in which uneaten food and fish feces are not allowed to accumulate to excess, and in which regular nutrient export processes are embraced, it's not an issue, IMHO. When other good practices of aquarium husbandry (ie; not overcrowding, overfeeding, etc.) are empIoyed, a botanically-"enriched" substrate can enhance- not inhibit- the nutrient processing within your aquarium and maintain water quality for extended periods of time.

Like many of you, I have always been a firm believer in some forms of nutrient export being employed in every single tank I maintain. Typically, it's regular water exchanges. Not "when I think about it', or "periodically", mind you.

Nope, it's weekly.

Now I'm not saying that you can essentially disobey all the common sense husbandry practices we've come to know and love in the hobby (like not overcrowding/overfeeding, etc.) and just change the water weekly and everything's good. And I'm not suggesting that the only way to succeed with adding botanical materials to the substrate is to employ massive effort at nutrient export; the system otherwise teetering on a knife's edge, with disaster on one side and success on the other.

Our aquariums are more resilient than that. If we set them up to be.

There is a lot of science to sift through about natural river/stream/pond substrates and how they function in the wild, and much of this can be applied to what we do in our closed aquariums. Of course, an aquarium is NOT a stream, river, etc. However, the same processes and "rules" imposed by Nature that govern the function of these wild ecosystems apply to our little glass and acrylic boxes. It's a matter of nuance and understanding how they work.

I'd love to keep us in the mindset of thinking about our aquariums as little "microcosms", not just "aquatic dioramas."

And of course, the whole idea of a substrate enriched with botanical materials is completely in line with the practices of a "dirted" planted aquarium. In our case, not only will there be an abundance of trace elements and essential plant nutrients be present in such a substrate, there will be the addition of tannins and humic substances which provide many known benefits for fishes as well. The best of both worlds, I think.

It's about creating an entire ecosystem.

Embracing and fostering not just the look, but the very processes and functions which take place in natural aquatic systems. Is it as simple as crushing some leaves, adding some coconut-based material, covering it up with sand and you have an instant tropical stream? No, of course not. You need to look at things sort of "holistically"- with an eye towards nutrient export and long-term maintenance.

Like so many things we discuss here, I admit that simply don't have all the answers.

In fact, I admit that I probably have more questions than answers. My experience at enriching substrates with all sorts of materials has been very positive- most recently, with my "tinted" brackish water mangrove aquarium. This tank features an abundance of different substrate materials, including decomposing mangrove leaf litter and other botanical materials.

It's been so biologically stable from almost day one as to be sort of "boring..." Phosphate and nitrate (the traditional biological "yardsticks" for analyzing aquarium water quality) have remained virtually undetectable on our hobby-grade test kits. This despite what is arguably one of the "dirtiest" (in traditional aquarium parlance, at least!) substrates I've ever created.

However, we need more experimentation.

What is the takeaway here?

I think the big takeaway is that we should not be afraid to experiment with the idea of mixing various botanical materials into our substrates, particularly if we continue to embrace solid aquarium husbandry practices.

In my opinion, richer, botanically-enhanced substrate provides greater biological diversity and stability for the closed system aquarium.

Is it for everyone?

Not for those not willing to experiment and be diligent about monitoring and maintaining water quality. Not for those who are superficially interested, or just in it for the unique aesthetics it affords.

However, for those of you who are adventurous, experimental, diligent, and otherwise engaged with managing and observing your aquariums, I think it offers amazing possibilities. Not only will you gain some fascinating insights and the benefits of "on-board" nutrient export/environmental "enrichment"- you will also get the aesthetics of a more natural-looking substrate as well.

Another week. Another challenge. Another set of questions. And another opportunity for us to provide some of the answers.

Jump in there...

Stay excited. Stay diligent. Stay methodical. Stay open-minded. Stay curious...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

"Indoor field work..."

Have you ever noticed how what is "normal" practice to us is a bit- well, "unconventional"- even "crazy" to others in the hobby?

Yeah...

When I describe our little hobby niche to other hobbyists who have different areas of interest, it's interesting that I'm usually met with looks of disbelief, and the occasional inquiry as to why we do what we do with our aquariums.

I totally get it, too.

I mean, to the hobbyist unfamiliar with our little niche, it does seem a bit odd that we take a "perfectly clean" aquarium and throw in a large amount of leaves and seed pods and stuff to...decompose on the bottom! This sort of goes against the grain of mainstream aquarium thinking!

We do add a lot of biological material to our tanks in the form of leaves and botanicals- and this is perfectly analogous to the process of allochonous input- material imported into an ecosystem from outside of it. Yeah, it's exactly what happens in the flooded forests, meadows, tropical streams, and rivers that some of us obsess over!

There's been a fair amount of research and speculation by both scientists and hobbyists about the processes which occur when terrestrial materials like leaves and botanical items enter aquatic environments, and most of it is based upon field observations.

As hobbyists, we have a rather unique opportunity to observe firsthand the impact and affects of this material in our own aquariums! I love this aspect of our "practice", as it creates really interesting possibilities to embrace and create more naturally-functioning systems, while possibly even "validating" the field work done by scientists!

It goes without saying that there are implications for both the biology and chemistry of the aquatic habitats when leaves and other botanical materials enter them. Many of these are things that we as hobbyists also observe every day in our aquariums! We see firsthand how leaves and botanical materials impact the life of our fishes and other aquatic organisms in these closed systems.

"Indoor fieldwork", if you will!

That's what we do...

Phenomenon such as the appearance of biofilms- long a topic that simply never came up in the hobby outside of dedicated shrimp keepers- are now simply "part of the equation" in a properly-established botanical-style aquarium. We understand that they appear as a normal part of the process when terrestrial materials become submerged under water. We're seeing them for the benefits they provide for our systems, rather than freaking out and panicking at their first appearance!

This is a fairly profound shift in the hobby, if you ask me!

A lab study I came upon found out that, when leaves are saturated in water, biofilm is at its peak when other nutrients (i.e.; nitrate, phosphate, etc.) tested at their lowest limits. This is interesting to me, because it seems that, in our botanical-style, blackwater aquariums, biofilms tend to occur early on, when one would assume that these compounds are at their highest concentrations, right? And biofilms are essentially the byproduct of bacterial colonization, meaning that there must be a lot of "food" for the bacteria at some point if there is a lot of biofilm, right?

More questions...

Does this imply that the biofilms arrive on the scene and peak out really quickly; an indication that there is actually less nutrient in the water? Is the nutrient bound up in the biofilms themselves? And when our fishes and other animals consume them, does this provide a significant source of sustenance for them?

Hmm...?

Oh, and here is another interesting observation:

When leaves fall into streams, field studies have shown that their nitrogen content typically will increase. Why is this important? Scientists see this as evidence of microbial colonization, which is correlated by a measured increase in oxygen consumption. This is interesting to me, because the rare "disasters" that we see in our tanks (when we do see them, of course, which fortunately isn't very often at all)- are usually caused by the hobbyist adding a really large quantity of leaves at once, resulting in the fishes gasping at the surface- a sign of...oxygen depletion?

Makes sense, right?

As I've said repeatedly, if we don't make the effort to try to understand the "how's and why's" of Nature, and attempt to skirt Her processes- she can and will kick our asses!

These are interesting clues about the process of decomposition of leaves when they enter into our aquatic ecosystems. They have implications for our use of botanicals and the way we manage our aquariums. I think that the simple fact that pH and oxygen tend to go down quickly when leaves are initially submerged in pure water during lab tests gives us an idea as to what to expect.

And a sort of "set of expectations" is always nice to have when you're pursuing unusual approaches in aquarium jeeping, right?

A lot of the initial environmental changes in our aquariums will happen rather rapidly, and then stabilize over time. Which of course, leads me to conclude that the development of sufficient populations of organisms to process the incoming botanical load is a critical part of the establishment of our botanical-style aquariums.

Here's another thing to consider: Inputs of terrestrial materials like leaf litter and seed pods can leach dissolved organic carbon, rich in lignin and cellulose. Factors like light, mineral hardness, and the bacterial community affect the degree to which this material is broken down into its constituent parts in this environment. Or, if the resulting breakdown creates some "algae fuel"- right?

Hmm...something we've kind of known for a while, right?

Lignin is a major component of the stuff that's leached into our aquatic environments, along with that other big "player"- tannin. What benefits does lignin provide in the aquarium context? I mean, does it provide any benefits?

Of course, we're sort of into tannins, right?

Tannins, according to chemists, are a group of astringent biomolecules that bind to and precipitate proteins and other organic compounds. They're in almost every plant around, and are thought to play a role in protecting the plants from predation and potentially aid in their growth. As you might imagine, they are super-abundant in leaves. In fact, it's thought that tannins comprise as much as 50% of the dry weight of leaves!

Holy @#$%!

And of course, tannins in leaves, wood, and plant materials tend to be highly water soluble, helping to create our beloved blackwater as they decompose. As the tannins leach into the water, they create that transparent, yet darkly-stained water we love so much! In simplified terms, blackwater tends to occur when the rate of "carbon fixation" (photosynthesis) and its partial decay to soluble organic acids exceeds its rate of complete decay to carbon dioxide (oxidation).

And it just goes to show you that some of the things we could do in our aquariums (such as utilizing alternative substrate materials, botanicals, and perhaps even submersion-tolerant terrestrial plants) are strongly reminiscent of what happens in the wild. Sure, we typically don't maintain completely "open" systems, but I wonder just how much of the ecology of these fascinating habitats we can replicate in our tanks-and what potential benefits may be realized?

Yes, I think just having a bit more than a superficial understanding of the way botanicals and other materials interact with the aquatic environment, and how we can embrace and replicate these systems in our own aquariums would be a huge advantage for us.

The real message here is to not be afraid about learning about seemingly complex chemical and biological nuances of blackwater systems. At least, on the level that we need to have a basic understanding of what to expect in our aquariums. Nature offers many clues, nuances, and ideas for us to run with.

As our practices evolve, I think that it's important to take a more "holistic" approach. One that takes into account the ionic content of the source water, the careful addition of substrate, botanical materials, wood, and the other aspects of our unique aquariums which will make them some of the most realistic representations of Nature yet attempted.

Observation, experimentation, and iteration are all important parts of the puzzle here.

Time for more "indoor field work."

Who's in?

Until next time,

Stay resourceful. Stay curious. Stay motivated. Stay creative. Stay thoughtful. Stay excited...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

That certain "something..."

Yesterday's blog/podcast about "realism" seems to have struck a responsive chord in many of you. There is something about the way we interpret Nature that gets everyone thinking. It has taken us several years to get to this point, but the emerging philosophy within our community reflects a more nuanced position.

Aesthetic-wise, our aquariums have never been more beautiful. The sheer talent out there is amazing.

However, many hobbyists who I correspond with regularly have communicated to me that something has been was lacking in many scapes in recent years. I mean, every aquarium is beautiful in its own way. Every aquarium has attributes that we can all agree are awesome. Yet, a smaller fraction of aquascapes just have a certain "it" factor that evokes something...

Regardless of how they are conceived and set up- "artistic", "high concept", or "natural" style- certain tanks have that "something" about them that seems hard to quantify.

Yet others fall short by miles.

For many years, I couldn't quite place it. What could it be? I had to really contemplate this...I mean, there's a lot of great work out there.

What makes a great aquascape well, "great"- is not just the materials it uses.

Sure, they can help. However, they're only part of the story.

We see a lot of talk online about excitement over some "new" type of rock or wood (really, there's "new" rock or wood? Who the f--k is "making" it?), and there is a certain percentage of the aquarium world that thinks that THIS is key to creating bold new work. Using the "new" rock to create the same old "iwagumi" or "diorama scape" is not really "new", right? I personally don't feel that it's advancing the hobby, really.

We all know how to advance the hobby...

It's about applying the philosophy, the idea, talent, and the execution.

It's NOT simply the materials making the 'scape. Utilizing specific materials may give you an "edge"- perhaps it will evoke something...Yet, they're just "materials" if not used in a unique way. I think that the majority of hobbyists know this, yet the idea of "THIS rock/wood/botanical/etc. will be the key to a great scape" lingers...

However, I think that there is something that we can apply to our work-a philosophy which doesn't really care what materials you utilize in your scape.

I think I know what it is. Really.

It's a concept which is truly inspired by Nature.

It's "Wabi-Sabi" again. Something that's been on my mind a lot lately.

Remember this philosophy?

In its most simplistic and literal form, the Japanese philosophy of "Wabi Sabi" is an acceptance and contemplation of the imperfection, constant flux and impermanence of all things.

This philosophy absolutely is applicable to the art and science of aquarium keeping.

Indeed, I think it's foundational.

This is a very interesting philosophy, one which has been embraced in aquascaping circles by none other than the late, great, Takashi Amano, who suggested that an aquarium is in constant flux, and that one needs to contemplate, embrace, and enjoy the sweet sadness of the transience of life.

It's about accepting the changes which occur in aquariums over time; enjoying each phase.

Many of Amano's greatest works embraced this philosophy, and evolved over time as various plants would alternately thrive, spread and decline, re-working and reconfiguring the aquascape with minimal human intervention. Each phase of the aquascape's existence brought new beauty and joy to those would observe them.

Did you get the part about "minimal human intervention?" I mean, it implies that an aquarium has to be left set up long enough for plants to thrive, decline, etc. In other words, you set it up for the long run.

Yet, in today's contest-scape driven, Instagram-fueled, "break-down-the-tank-after- the-show" world, this philosophy of appreciating change by Nature over time seems to have been tossed aside as we move on to the next 'scape. It's all about "sketch it out, set it up, photograph it, edit it, share it...break it the f---- down- and move on to the next one..."

Sure, it might be a product of our current social media-fueled environment, and that's an easy thing to "blame" it on-but I think it's deeper than just that. I think it's a reflection of the lack of patience which has crept into the "craft" part of the aquarium hobby. The desire to achieve immediate gratification for our work- which, in reality denies us the opportunity to see it really evolve into something truly special.

And that is almost tragic, IMHO.

In fact, I can't help but wonder if Mr. Amano would feel the same.

Many of the beautiful aquariums you see splashed all over the internet aren't even typically left up long enough for Nature to really "do her thing." It's not about a few weeks- or even a few months..It's about allowing processes which take many months-or even years- to arise and evolve aquascapes over long periods of time.

And not all of these processes are "Insta-beautiful", right? They often take time to go from what would be perceived as not so attractive to "evolved" and intricate.

Just like in Nature.

I mean, sure, you can do things like wrap wood or rocks with moss to get a kind of "mature look" in some aspects of the scape, but you can't rush the formation of "patinas" of biofilms and such- or in our case- the softening and breakdown of botanical materials- stuff that really takes time to occur.

I suppose the time frame aspect makes it hard for many to appreciate wabi-sabi in many ways...As a hobby, we're simply not used to looking at things in our aquariums changing over long periods of time, the way Nature organizes, evolves, and operates. We have our own hopes, needs, and desires for our aquariums, and how they "should" look. We haven't traditionally seen things like decomposition, biofilms, algae, etc. as "attractive" in the context of our aquariums.

Yet, they are all integral components of the "something" that is "wabi-sabi."

Something which requires us to have more faith in Nature than many of us have had in recent years.

Now, when we talk about the use of natural materials in our aquatic hardscape, such as leaves and softer aquatic botanicals, which begin to degrade after a few weeks submerged, one can really understand the practicalities of this philosophy. It could be argued, perhaps, that the use of botanicals in the aquariums, by virtue of these attributes is the very essence of what "wabi-sabi" is about.

I think we can learn to appreciate this transient aspect, and I think in order to do that, a slightly different approach to aquascaping is warranted. An approach that allows hobbyists to experience this in a slightly faster time frame...patience still is huge- but the lessons are learned more quickly, perhaps.

Yes, we do it with botanicals.

Sure, a carefully constructed hardscape, IMHO, will almost always have some more or less "permanent" things, like rocks and driftwood. Yet, these should be complemented and enhanced by "degradable" items, such as leaves, as well as the "softer" seed pods and such, which not only offer enhanced aesthetics- they offer enrichment of the aquatic habitat through their release of tannins, humic acids, vitamins, etc. as they decompose- just as they do in Nature.

Leaves and such are simply not permanent additions to our 'scapes, and if we wish to enjoy them in their more "intact" forms, we will need to replace them as they start to break down.

This is not a bad thing.

It is simply how to use them to create a specific aesthetic in a permanent aquarium display. Much like flowers in a garden, leaves will have a period of time where they are in all their glory, crisp and "fresh-looking", followed by the gradual, inevitable encroachment of biological decay. At this phase, you may opt to leave them in the aquarium to enrich the environment further and offer a new aesthetic, or you can remove and replace them with fresh leaves and botanicals.

This very much replicates the process which occur in Nature, doesn't it?

Decomposition, addition, renewal, change....

This is absolutely the crux of wabi-sabi.

With the publishing of photos and videos of leaf-influenced 'scapes in the past few years, there has been much interest and more questions by hobbyists who have not really considered these items in an aquascape before. This is really cool, because new people with new ideas and approaches are experimenting. We're trying all sorts of interesting things...

And we are looking at Nature as never before.

We're celebrating the real diversity and appearance of natural habitats as they really are...Diverse, rich, often turbid and decidedly "messy"- and there is real beauty in them that is both compelling and obvious when we observe them objectively.

Nature "unedited" and "unfiltered."

Some hobbyists have commented that, as their leaves and botanicals break down, the scape as initially presented changes significantly over time. Wether they know it or not, they are grasping wabi-sabi...sort of. One must appreciate- rather than simply "observe"- the beauty at various phases to really grasp the concept and appreciate it.

To find little vignettes- little moments- of fleeting beauty that need not be permanent to enjoy.

Yeah, it's not just observing a certain "something" in our aquarium- it's a way of appreciating and embracing the processes by which Nature evolves the world.

Yeah, it's a definite "mental shift", as we talk about so much here. A good one. An important "unlock" which may help you appreciate the hobby- and Nature- as never before. An affirmation that yes- there is a certain "something" to aquariums which accept and adopt Nature's processes and aesthetics in an "unflitered", "unedited" manner.

A certain "something" that will advance the hobby. Something many of you are already doing- each and every day.

Stay bold. Stay diligent. Stay creative. Stay engaged. Stay excited. Stay thoughtful...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

A tale of...Tucanos...

Some of the biggest ideas start with the smallest executions.

That's a good philosophy and attitude, IMHO. And more economical, too!

We've talked many times about the idea of using so-called "nano aquariums" as a sort of "testbed" for ideas and concepts. The idea that it's easier to try some of these exotic experiments on a small scale than it is to go right to the "big time" is top of mind.

Not long ago, you followed us on such a journey with a simple, but well-thought-out Ultum Nature Systems 45A all-in-one aquarium, set up for a very specific little fish.

It was a great example of this "big idea/small execution" philosophy.

I had been "mentally testing" my concept of what came to be called the "Tucano Tangle"- a biotope inspired aquarium to replicate aspects of the habitat of the Tucanoichthys tucano, a small characin found only in one area, the Rio Uaupes- specifically, "...a brook emptying into the igarape Yavuari"...like, that's pretty damn specific, right?

Damn, those little bodies of water in the jungle again...

It was time to really get past just the hobby literature for this one- and that meant a voyage into more scholarly writings. I was doing a geeky "deep dive" into this type of habitat in Amazonia, and stumbled upon this gem from a scientific paper by J. Gery and U. Romer in 1997:

"The brook, 80-200cm wide, 50-100 cm deep near the end of the dry season (the level was still dropping at the rate of 20cm a day), runs rather swiftly in a dense forest, with Ficus trees and Leopoldina palms...in the water as dominant plants. Dead wood. mostly prickly trunks of palms, are lying in the water, usually covered with Ficus leaves, which also cover the bottom with a layer 50-100cm thick. No submerse plants. Only the branches and roots of emerge plants provide shelter for aquatic organisms.

The following data were gathered by the Junior author Feb 21, 1994 at 11:00AM: Clear with blackwater influence, extremely acid. Current 0.5-1 mv/sec. Temp.: Air 29C, water 24C at more than 50cm depth... The fish fauna seems quite poor in species. Only 6 species were collected I the brook, including Tucanoichthys tucano: Two cichlids, Nannacara adoketa, and Crenicichla sp., one catfish, a doradid Amblydoras sp.; and an as yet unidentified Rivulus, abundant; the only other characoid, probably syncopic, was Poecilocharax weitzmani."

Yeah, it turned out to be the ichthyological description of the little "Tucano Tetra", and was a literal treasure trove of data on both the fish and its habitat. I was taken by the decidedly "aquarium reproducible" characteristics of the habitat, both in terms of its physical size and its structure.

Boom! I was hooked.

Now, I admit, I wasn't interested in, or able to safely lower the pH down to 4.3 (which was one of the readings taken at the locale), and hold it there, but I could get the "low sixes" nailed easily! Sure, one could logically call me a sort of hypocrite, because I'm immediately conceding that I won't do 4.3, and I suppose that could be warranted...

However, there is a far cry between creating 6.2pH for my tank, which is easy to obtain and maintain for me, and "force-fitting" fishes to adapt to our 8.4pH Los Angeles tap water!

And of course, with me essentially trashing the idea of executing a hardcore 100% replication of such a specific locale, the idea was essentially to mimic the appearance and function of such an igarape habitat, replete with lots of roots and leaf litter.

And the idea of executing it in a nano-sized aquarium made the entire project more immediately attainable and a bit less daunting. I wanted to see if I could pull off a compelling biotope-inspired setup on a small scale.

That's where my real interest was.

So, even the "create the proper conditions for the fish instead of forcing them to adapt to what's easiest for us" philosophy can be nuanced! And it should! I don't want to mess with strong acids at this time. It's doable...a number of hobbyists have successfully. However, for the purposes of my experiment, I decided to happily abstain for now, lol.

And without flogging a dead horse, as the horrible expression goes, I think I nailed many of the physical attributes of the habitat of this fish. By utilizing natural materials, such as roots, which are representative of those found in the fish's habitat, as well as the use of Ficus and other small leaves as the "litter" in the tank, I think we created a cool biotope-inspired display for these little guys!

And man, I love this tank.

Being able to pull off many aspects of the look, feel and function of the natural habitat of the fish was a really rewarding experience.

That's one example of this philosophy in action. Again, it's NOT perfect. It's certainly something that can- and should- be improved upon. The pH thing, for example. But the physical environment; the biological nuances...the long-term function of this type of aquarium microcosm...I think we are well on our way to building a lot of "best practice" stuff here.

I'm still not satisfied yet...

However, I think it's a good start.

I think it also requires the usual caveats- a "mindset shift" that embraces the fact that the natural habitats we love don't always meet our "acculturated" aesthetic expectations. We need to understand that Nature does her own thing, regardless of whether we "approve" of it or not!

Like, I love it more than any other "biotope-inspired" tank I've ever set up.

And, people have asked why I didn't do it in a larger tank. Well, it's pretty simple: I tried it on a small scale because of the tiny size (and breath-taking price!) of the Tucanos; I figured they'd be utterly lost in a larger (like 50 US gallons) aquarium. Not to mention, that I'd have to take out a second mortgage on my home to acquire a population significant enough to make it look like there were any fish in the tank!

So, here I am.

Of course, I love the physical appearance of the aquarium so much that I totally want to scale this baby up! That's a total fist-geek mindset, for sure. Now, the idea of populating a significantly larger tank entirely with the little Tucanos- although tempting from a conceptual standpoint, is really an economically impractical approach. I suppose I could do that...but at $12USD each, to get a school justifiably large enough to place in a 50-gallon tank would be pretty damn pricy!

Would I add some other fishes to this tank?

My original plan was to sort of stay reasonably monospecific, with just the Tucanos. However, reaserch showed that some fishes are found sympatrically with the Tucanos- specifically, the cute little cichlid, Ivanacara adoketa, some Amblydoras catfishes, Rivulus (yeah, killies- but the f- ing things jump like mad...and in my open-top tank...), and the coolest of all- the equally tiny and somewhat pricy Poecilocharax weitzmani- a fish that looks a lot like the Tucano, but dwells in the leaf litter!

How could I resist doing this? Why wouldn't I want to go bigger?

I don't know if I can for much longer, lol.

So, picture a scaled-up version of the little tank...The main thing I'd do differently would be to slope up the substrate towards the rear of the tank, and really make sure that the Melastoma roots that I use are placed more towards the rear, giving the impression of a bunch of roots from marginal vegetation (species of Ficus and Leopoldina species are the dominant jungle plants in the habitat I'm interested in replicating), perhaps in a bit of an "arc", which will provide a lot of "front and center" swimming area- and a "basin" of sorts for leaf litter to accumulate.

I'm just scheming.

I did add some Corydoras pygmaeus to the mix, to create a little interest and some action (Yeah, the Tucanos are not the most active swimmers, lol).

The scale of a larger tank will allow me to create the more open, yet still complex 'scape that I am envisioning here.

Oh, I'm liking this idea even more now. I can fully visualize this.

However, can I AFFORD it?

Hmmm...

So, my little exercise in scaling up will cost me a lot of money, a little bit of enjoyable time, and provide unlimited awesomeness...

I think.

Yeah, it will.

Right? Maybe? Yeah.

Damn it. Stop me.

Or maybe not...enable me, then. Yeah!

Yet, never forget that you can pull off a "big idea" on a small scale, and fall in love with it just the same!

That's the biggest takeaway from the "Tale of the Tucanos..."

Stay innovative. Stay creative. Stay restless. Stay bold. Stay motivated. Stay studious.

Stay just a little...weird...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

On the hunt...

We're certainly in what is arguably one of the most engaging, educating, and obsession-inducing hobbies there is! Many of us have devoted a lifetime to this fishy world we love so much.

Have you ever considered that a surprisingly large part of the aquarium hobby is the pursuit of stuff. The pursuit of the perfect aquascape...The pursuit of the ultimate Pleco specimen. The pursuit of the perfectly stable aquarium. The pursuit of that fancy filter, etc.

Pursuit.

It can be anything hobby related, really...We spend a big part of our time in search of___________________ . Now, like most of you who have grown up in the aquarium hobby, I've spent a lifetime scouring local fish stores, club meetings, shows, and wholesalers looking for the fishes of my dreams. It's part of the experience of being a real hobbyist. We Study. We dream. We ponder. We plan.

We search.

Continuously.

We share experiences. We learn from each other. We tell stories.

And we've all heard this one before: The so-called "Urban Aquarium Myth." You know- the reefer that spotted an obscenely rare, juevenile Centropyge interruptus at Petco, mismarked as a "Yellow Tail Damsel" for $3.00, or the the guy who scored the Aulonocara hansbaenchi from the "Assorted African Cichlids- $5.00 each" tank at the LFS..Or a huge, rare Bucephelandra colony mislabeled as Anubias nana "Petite"- the list goes on and on...

("Really, it was listed as an "Assorted African Cichlid...")

Stuff like that.

Some of it is utter bullshit. Some might have a kernel of truth...and some- well...maybe some guy DID score a juvenile Centropyge interruptus at Petco!

Maybe?

(The real deal- not from Petco...Image by Jake Adams)

Stories like those keep many of us "lifers" in the hobby moving, talking, and inspiring us in a strange way.

The keep us on the hunt.

Much like the stories you hear about the winning $250,000,000 lottery ticket bought at the local convenience store, or the college kid at the laundromat, casually spitting lyrics while folding his jeans, who gets discovered and signed by Drake or something and becomes the next hip hop superstar- such tales have motivated countless fish geeks over the years to keep looking, keep digging in the local fish stores and petshops around the world- searching for that elusive, as yet unappreciated-by-the-masses rarity that is staring everyone right in the face!

Much like the bold ichthyologists of a century before, who, braving Malaria, insects, predatory reptiles, and revolutionary, gun-toting guerrillas, searched tiny tributaries of The Amazon, the nameless streams of The Congo, or the stinky peat bogs of Southeast Asia, we relentlessly do our fish searches of the local aquarium stores and pet shops in our cities...

Of course, it's from the air-conditioned comfort of our luxury SUV, with the only real "perils" we face being traffic, expired parking meters, lack of a convenient ATM, and spilled coffee from our commuter mug. But that doesn't make it any easier or less fraught with danger, in our minds. Nope. It's there. It's real.

Our embarkation point might be the neighborhood Starbucks, and our "hunting ground" is that obscure tank in the back corner of the local fish store. Yet, that doesn't make the quest any less exciting, exotic, or alluring to us.

Maybe it IS in the store...somewhere. Perhaps a random fish in a display tank. Or perhaps, the "New Arrivals" tank...Or my personal fave, the "Any fish in this tank $2.00" one. You know, the tank that holds the "one offs", or the fishes that leaped from the bag during a busy day of unpacking new fishes from the wholesaler, and simply was placed in the tank in a hurried manner, without a positive ID, by the LFS staff member who had 38 boxes of fishes to unload.

It happens, right?

So, we continue.

We strategize. We dedicate. We persevere...

We search.

We're on the hunt...

Now, we're certainly NOT looking to "beat the system." (At least, none of us would confess to this..), but we ARE often looking for that one fish that stands out somehow. It might be the one you just read about in a magazine or online blog. Or, perhaps it's simply one YOU have never kept before, which hasn't been available for a while. The one you've been trying to find for the last 4 years. Just rare, but unexciting to most...But not to you- the obsessed hunter.

Or, maybe it's a rather sad, unrecognizable specimen of a rare and ultimately beautiful fish that just needs a nice tank and a little TLC to shine. Or it's the "ugly duckling" juvenile of a fish that blossoms as an adult.

Maybe it's the regional "variation" of a more common species that only the most dedicated enthusiast (you) would recognize and appreciate. Often, it's a fish that was brought in as "bycatch" in a shipment of "Mixed Rasbora" or whatever, and sort of slipped through the cracks at the importer, wholesaler, and now the store.

They didn't know what they were looking at.

But to YOU- the educated, patient "Indiana Jones of the fish stores"...it's a true "score!"

The one you've been waiting for.

The one that, for whatever reason- haunts your dreams; sparks your obsessions.

And, of course, you know how it feels to score something like that, too, right?

You experience a mixture of emotions: Excitement, elation, guilt...Especially if it's a fish you feel should cost more. After your discovery in a tankful of other fishes, you compose yourself, disguise all overt symptoms of euphoria, then nonchalantly ask the LFS employee to grab it from the tank and bag it up for you ("Can you just snag me that little grey one that's hiding in the Sword Plant?"), all the while pretending to stifle a yawn, as if indifferent to the whole thing.

You even go so far as to casually add a can of flake food to your purchase, just to sort of serve as a "distraction" for the guy at the counter, lest he identify your score. And, of course, inside your head, all that your'e thinking is, "Please, don't let my buddies from the local club show up right now!"

You know that they'll be the first ones to loudly say, "WOW! $12.99! Isn't that an 'L090 Pleco?' How much are you paying for that? That's like a $90.00 fish! You didn't get it from the "Assorted Catfish" tank, did you? That MUST have been a mistake! They totally screwed up!"

"You scored, man!"

No, no no!

"Don't blow this for me, guys!"

And in all likelihood, the LFS employee is thinking to herself, "OMG, the guy has such shitty taste in fishes. I can't believe he bought the ugliest damn fish in the tank- and paid $12.99 for it! Hell, I would have just given it to him...No one would ever buy that thing..!"

RIght?

Well, you've convinced yourself that you've "dodged the bullet" this time, right? You're convinced that you made the ultimate "score."

Then comes the most nerve-wracking part of your whole adventure: The "getaway."

Yeah, you've found the aquatic equivalent of a real Luis Vuitton wallet in a sea of fakes- and are getting away with it. The one genuine diamond in a pile of cubic zirconia...Tensions are high...It's all about composure at this point.

Don't blow it.

You've come this far...

Out the door you go, trying to walk as slowly as possible to your car, without gesturing, excessively smiling, or behaving in any other manner that would betray your emotions.

Inside, your heart is pounding...perhaps a bead of sweat trickles down your forehead...

A good day. A very good day, indeed.

You rush home with your new found acquisition, all the while praying to yourself that you're not somehow being followed by the LFS manager, who suddenly realized his/her employee's mistake. Like a spy evading her pursuers, you even vary the route back home, going way out of the way... just in case there is someone from the LFS tailing you.

And you won't visit that store again for a month or more. You go "underground." Yeah, you've watched all of the "Bourne" movies. You know what to do...

After you get home and get your prize acclimated, you race online, and confirm what you already knew: You WERE right. It WAS the one...That was a SCORE!

At that point an odd mixture of elation, guilt- and...contentment fills your mind, right? Later that night, you toast to yourself with a glass of your favorite wine, and sigh happily...

I venture to guess that we've all had this guilty pleasure- or some variation of it- before.

And to some of us-it comes with this...this...moral quandary.

The exhilaration, dashed with just a tinge of guilt at having "beaten the system." Of course, you rationalize that it's better that the fish ends up in the hands of the person best suited for its care- YOU! You're the aquarist who truly appreciates its subtle beauty, scarcity, and elusiveness. And- you have had a real run of bad luck lately, when all of those Headstanders jumped, and the batch of Apisto fry died in week 8, and...So you're "due", right?

Yeah.

The "aquarium gods" owe you one, huh? Perhaps?

Yet for many of us, there's still a little biting guilt, right? The price we pay for "scoring." Even if the guilt is only in our own mind...which it usually is.

Hmm... The realities of the "Urban Aquarium Myth", right?

So, time for your confessions. Who has had such a score? What did you score? And how did things work out? Did you feel any guilt?

Confess your guilt, if any, and feel better about it...maybe.

But never give up the pursuit.

The hunt.

Stay alert. Stay diligent. Stay observant. Stay patient. Stay undaunted...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Getting away with it?

There are amazing life lessons that we can learn just from playing with this hobby.

Have you ever made one of those stupid mistakes in fishkeeping? You know, a really stupid one...A mistake that you should "know better" than to have made at this stage in your "aquarium career?"

You know, something basic- like not quarantining a new fish and getting your whole tank sick. Or using some sort of additive (like algicide or something) that you knew would have some kind of long-term (potentially detrimental) effect on your tank? You know- a shortcut. An ill-advised move. A lapse in judgement, protocol, procedure.

One of those things that, perhaps in a moment of indecisiveness, frustration- or even mild panic- that you "pulled the trigger" on and just did?

I'll digress a bit here...

I have a friend who brags about his flagrant "violation" of the fundamental principles of aquarium practice. He proudly shirks every guideline that's been offered up over the years. Happily disregards all of the common "best practices" of the aquarium hobby.

And gets away with it. Most of the time, anyways.

Or so it seems...

I mean, I suppose we all have gotten away with stuff that we shouldn't have...maybe once or twice?

I suppose that it's human nature to get a bit "complacent", relaxed, or just over-confident. Call it whatever you want.

I know I've made that bad judgement call before: "Oh, that fish looks fine, and there were no sick fish in the tank at the store- I'll chance it and just add him." Or, "I don't know why they say that fish is supposed to be so aggressive. He hasn't even chased anyone...yet."

You think you're getting away with something that no one else has...

Everything is just fine. What's the big deal?

Yeah, you've gotten away with it!

Or, have you?

I mean, as "advanced" aquarists, I wonder if we sometimes think that we've "paid our dues" to the "aquarium gods", and that, even in moments of irrational decision making, we'll get away with it because we're, well- "advanced?"

I think so.

I know that I've made really lazy, impulsive decisions before, even when I knew that I shouldn't have. Like taking on some fish I won at the club auction when I really didn't have the space. Or using aged tap water to fill a new aquarium in a hurry when I should have just waited the extra few days until the replacement RO/DI cartridges arrived. Maybe I should have rinsed that sand first...

Sometimes, I'd get away with it.

Other times, I wouldn't be so lucky, and fate would bite me on the ass and teach me a lesson.

The "lesson" isn't really even not to do the specific action that you did to cause the problem. It's not the feeding of the contaminated food, or the failure to remove the eggs from that batch of Discus with a reputation for eating them, or whatever...

It's the decision to proceed when that little voice inside your head tells you- well- SCREAMS at you- to "stop, drop, and cover!"

It's not falling back on the hard-won experience that you've accumulated during years of fish keeping.

Even as a beginner, you can "trust" what "they" say online, in books, at clubs etc., and do things the (often) slower, more tedious way- or you can tempt fate and take the shortcut.

And, of course, the problem with taking the shortcut is that you might be one of those people for whom it works. For a while.

And you'll convince yourself and others that "they" are full of shit.

Everyone is making too big a deal out of it- because you've done it this way for years without any of the nasty results that "they" warned you about. You're like, "immune" or something from the fate that befalls most everyone else who flaunts the rules...

And, before you know it...this becomes "normal" to you. The bad habits become a routine part of your repertoire.

Yikes.

It's been said that the "fail safe" of human endeavour is failure, so why play into that? Why go against the grain on everything? I mean, trying something different than everyone else is doing is cool. However, when I am talking about this idea, we're talking about stuff like breaking the "rules" of aquascaping, designing a different type of breeding setup, etc.

We're NOT talking about immediately adding 100 Cardinal Tetras to a brand spanking new 40 gallon tank- shit like that.

That's trying to break the laws of Nature...Assuming that stuff as mundane as the nitrogen cycle doesn't apply to YOU.

That's just stupid.

Think about the so-called "fundamentals" for a moment, and why they exist in the hobby.

"Fundamental guidelines based on natural processes" are what they are because, well- they're fundamentals!

Nature runs based on them.

She's done it pretty damn well for billions of years, too...

We can't just "edit" and pick and choose what basic laws of nature we want to adhere to. Oh, we can, but the payback- which WILL come inevitably, eventually- is a bitch! Why gamble with the lives of helpless animals for our own arrogant means?

One that I would hear all the time in the reefkeeping world is, "I haven't done a water change on my tank in over a year, and my fishes are just fine."

Okay, good for you. Why are you doing that? What benefit does this provide your fishes?

Are you doing it to prove a point or whatever? What's the "end game" by doing that?

It makes no sense to me.

We can change.

And my friend? The guy who constantly takes pride in how he defies the "laws" of aquarium keeping?

Well, his beautiful and long-established 300-gallon African Cichlid tank, the pride of his fish collection- is now a breeding ground for at least 3 different fatal diseases, all of which would have been prevented if he would have quarantined.

Did he finally learn his (expensive and painful) lesson and mend his ways?

He said no, he'll keep doing things his way. He felt that this was just a fluke. An aberration. An unusual occurrence.

Of course, the battery of 11 gallon quarantine tanks in his garage fish room tells a different story!

So, perhaps you can teach an old fish new tricks?

He's just to fucking proud to admit it, that's all.

He learned!

"Getting away with it" has its price. And it's usually quite high.

Regardless of your level of experience, don't give in to the temptations. take the long way home, and be great.

Stay thoughtful. Stay careful. Stay humble. Stay bold. Stay decisive. Stay patient.

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Water quality and the botanical-style aquarium: Practices, potential, and speculation...

When it comes to managing a botanical-style aquarium, you are already at a sort of "disadvantage" when it comes to running a "spotlessly clean" aquarium. I mean, you've already committed to a tank which contains large quantities of materials, most of which are in the process of breaking down at any given time.

Correction...ALL of them!

What is the implication of all this "stuff" breaking down in our tanks?

There must be a thousand ways to set up an aquarium and operate it. In fact, its probably several times that amount. And no one can ever seem to agree what the "best" way to go is. And that's okay. There are a lot of cool approaches you can try. So, while we might disagree on the best approach or style, we all seem to have a common goal:

Providing the best possible environment for our fishes.

Pretty much every really serious aquarium hobbyist can agree on one thing: It's important to have information about what's going on in his or her aquariums. Observation, collection of data, and interpretation of the information gathered have been keys to our success in so many areas of endeavor in the hobby.

And our botanical-style aquariums are a bit of an enigma.

I mean, we have tanks with all of this stuff decomposing in the water, yet manage to maintain high water quality and stability for extended periods of time without any real "magic", in terms of procedure or equipment.

What gives?

And of course, not being a scientist makes it kind of challenging for me to make all kinds of assertions about water quality and chemistry, so I will at least try to focus on what we want to achieve, water quality-wise, and how botanical-style aquariums seem to be able to "pull it off" given their vast quantities of leaves, seed pods, etc.

Now, we kind of have a pretty good "handle" on which tests make the most sense for our pursuits. It's a given that ammonia, nitrite, pH and DKH are the key indicators which most hobbyist will want to know about.

And then, there are the tests which give us information on the quality of the environment we've created- nitrate and phosphate. Nitrate (NO3) is not necessarily considered "toxic" at a specific level, although a typical rule of thumb is to keep readings under 50 mg/l- or better still, 20mg/l or less, for most fishes at various stages of their life cycle.

Although there is no "lethal dose", as indicated above, and many fishes can tolerate prolonged exposure to up to 500 mg/l of nitrate, studies have revealed that prolonged exposure to elevated levels of nitrate may reduce fishes' immunity, affecting their internal functions and resistance to disease.

Many fishes can adapt- to a certain extent- to a gradual increase in nitrate over time, although long-term physiological damage can occur. And of course, some fishes are much more sensitive to nitrate than others, displaying deteriorating overall health or other symptoms at much lower levels..

One of the interesting things about nitrate is that it can and will accumulate and rise over time in the aquarium if insufficient export mechanisms (ie; water exchanges, lack of chemical or biological filtration capacity exist within the aquarium. This, of course, gives the impression that fishes are "doing okay" when the reality is that they are exposed to a long-term stressor.

The presence of plants, known for their utilization of nitrate as a growth factor, is also considered a viable way to reduce/export nitrates, along with overall good husbandry (ie; stable fish population, proper feeding technique, etc.)

In our botanical-filled, natural-style aquariums, I have personally never observed/measured high level of nitrate. In fact, with a good husbandry regime in place, undetectable (on a hobbyist-grade test kit, at least) levels of nitrate have been the norm for my systems. I think that the highest nitrate reading I've personally recorded in a botanical-style system which I maintained was around 10 mg/l.

Why is this?

Well, I personally feel that well-maintained systems, including our heavily botanically-influenced ones, offer a significant "medium" for the growth and proliferation of beneficial bacteria species, such as Nitrospira. I have a totally ungrounded "theory" that the presence of botanicals, although in itself a contributor to the the biological load on the aquarium, also is a form of "fuel" to power the identification process- a carbon source, if you will, to elevate levels of biological activity in an otherwise well-maintained system.

Okay, sounds like a lot of cobbled-together "mumbo jumbo", but I think there is something to this. I mean, when you think about it, a botanically-rich aquarium, with leaves and other materials, fosters bacteria, fungi, biofilms, and supports crustaceans and other organisms which can consume the botanicals as they breakdown, along with fish wastes and other organics. A sort of "on board" biological filtration system, if you will, with the added benefit that fishes will consume some of these organisms. Perhaps, (and I'm reaching here a bit) even the basis for a sort of "food web", something that we know exists in all natural aquatic ecosystems.

Something to think about!