- Continue Shopping

- Your Cart is Empty

The "self-feeding aquarium?" A grand experiment, or a form of benign neglect?

Like most of you, I'm a borderline obsessive aquarist...

Like, I constantly observe, test, or tweak each and every tank, every day. That being said, I have learned over the years that a well thought-out aquarium doesn't need endless doting attention on a non-stop basis.

In fact, because of a busy travel schedule, "company building", and just life in general over the last few years, I even might have missed a water exchange or feeding or two..or three...or...

Yeah, I'm not proud of it- but I won't deny it, either.

In my world, missing water exchanges and feedings and such were, for many years, a sort of "scarlet letter" that you ended up wearing for all to see (well, even if no one else knew...you just felt, I dunno...guilty!).

Now, curiously, I always seemed to havereefing friends who were obsessed with- even proud of- their "ability" to run a "successful" system without water exchanges and such. Maybe rebellious types are somehow attracted to me or something? They'd actually use a sort of "reverse mentality", in which you'd hear them proudly brag about stuff like, "I never run a protein skimmer on my reef." Or, "I haven't done a water change in like a year!" I mean, that was stuff that would make my head explode... I was like, "If you're gonna be a loser aquarist- don't brag about it!"

I take a dim view of some stuff (shocker, I know...)!

Successful tanks require effort and care.

Yeah, I was/am all about continuous, regular maintenance and dedicated husbandry practices-particularly water exchanges, for which there is simply no substitute for, or no valid reason NOT to execute, IMHO. However, there is one "basic" aspect of aquarium keeping that I have always employed a bit of an "intentional avoidance" of:

Feeding.

"WTF, Fellman. Skip a goddam water change...But feeding? Really?"

Yes. Really.

But before you totally trash me for being hypocritical or even lazy, attempting to brazenly flaunt convention, or simply being guilty of a form of "benign neglect"- hear me out. It's not really about being lazy. It's an intentional thing. I plan for it. In fact, you do too, even though you may not think about it.

And it might be a "sort of" deliberate attempt to flaunt convention...in a nice way, of course.

However, this "practice" is part of a larger thesis which I have about botanical-style aquariums and their management, operation, and benefits:

Of all of the things we do in our blackwater/botanical-style aquariums, one of the few "basic practices" that I think we can actually allow Nature to do some of the work on is to provide some sustenance for our fishes.

Think about it: We load up our systems with large quantities of leaves and botanicals, which serve as direct food for some species, such as shrimp, and perhaps Barbs and Loaches.

These materials famously recruit biofilm and fungal growths, which we have discussed ad nasueum here over the years. These are nutritious, natural food sources for most fishes and invertebrates. And of course, there are the associated microorganisms which feed on the decomposing botanicals and leaves and their resulting detritus.

Having some decomposing leaves, botanicals, and detritus helps foster supplemental food sources.

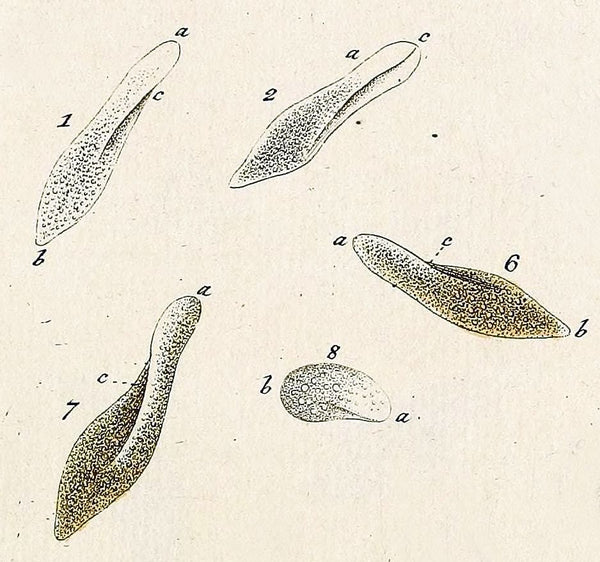

Now, we have briefly talked about how decomposing leaf litter does support population of "infusoria"- a collective term used to describe minute aquatic creatures such as ciliates, euglenoids, protozoa, unicellular algae and small invertebrates that exist in freshwater ecosystems.

Yet, there is much to explore on this topic. It's no secret, or surprise- to most aquarists who've played with botanicals, that a tank with a healthy leaf litter component is a pretty good place for the rearing of fry of species associated with blackwater environments!

It's been observed by many aquarists, particularly those who breed loricariids, that the fry have significantly higher survival rates when reared in systems with leaves present. This is significant...I'm sure some success from this could be attributed to the population of infusoria, etc. present within the system as the leaves break down.

Biofilms, as we've discussed many times before, contain a complex mix of sugars, bacteria, and other materials, all of which are relatively nutritious for animals which feed on them.

It therefore would make a lot of sense that a botanical-influenced aquarium with a respectable growth of biofilm would be a great place to rear fry! Maybe not the most attractive place, from an aesthetic standpoint- but a system where the little guys are essentially "knee deep" in supplemental natural food at any given time is a beautiful thing to the busy fish breeder!

And yeah, my experience indicates it performs a similar role for adults fishes.

In the wild, creatures like hydracarines (mites), insects, like chironomids (hello, blood worms!), and copepods, like Daphnia, are the dominant fauna that fishes tend to feed on in these waters. There's a lot of cool information that you can uncover when you deep dive into scientific information on our fishes- particularly gut content analysis of wild fishes.

Gut content analysis of fishes which inhabit leaf litter habitats reveals a lot of interesting things about what our fishes consume.

In addition to the above-referenced organisms, organic detritus and "undefined plant materials" are not uncommon in the diets of all sorts of fishes. This is interesting to contemplate when we consider what to feed our fishes in aquariums, isn't it?

It is.

Anyways, these life forms, both planktonic and insect, tend to feed off of the leaf litter itself, as well as fungi and bacteria present in them as they decompose. The leaf litter bed is a surprisingly dynamic, and one might even say "rich" little benthic biotope, contained within the otherwise "impoverished" waters. I find this not only fascinating- but a fact that we as aquarists can embrace to create aquariums capable of supplementing- or even sustaining-our fishes via the nutrition they can provide.

And, as we've discussed before on these pages, it should come as no surprise that a large and surprisingly diverse assemblage of fishes make their homes within and closely adjacent to, these litter beds. These are little "food oases" in areas otherwise relatively devoid of food. The fishes are not there just to look at the pretty leaves!

They're there to feed and take advantage of the abundant and easy-to-access food resources.

And of course, it goes without saying that Nature works (if allowed to do so) in a similar manner in the aquarium!

The leaves and botanicals we add to our tanks do what they've done in Nature for eons: They support the basis for a surprisingly rich and diverse "food web", which enables many of the resident life forms- from bacteria, to insects...right up to our fishes- to derive some, if not all of their sustenance from this milieu.

Confession time?

Okay.

I've created botanical tanks for years with part of the intention being to see if I can support the resident fishes with minimal external food inputs.

That felt better.

My rationale was that, not only will the leaves and botanicals help foster or sustain such "food webs" as they do in Nature, but that the lower amount of external food inputs by the aquarist helps foster a cleaner system, which is especially important when one takes into account the large amount of bioload decomposing leaves and botanicals account for in the aquarium!

And guess what? It works.

Just fine.

I've done this about 8 times in the past two years, with great results.

A beautiful case in point is one of my recent little office aquariums; a "nano" tank which was "scaped" only with Texas Live Oak Leaf Litter, Yellow Mangrove Leaves, and Oak Twigs. (I know, we're currently awaiting a re-supply of Mangrove leaves any day now!)

Now I know that this tank isn't everyone's idea of aesthetic perfection..I mean, it's essentially a pile of fucking leaves...However, to the fishes and other life forms which reside in the tank, it's their world; their food source.

And it's reminiscent of the wild habitats from which they come.

In that tank, I maintained a shoal of 25 "Green Neon Tetras", Parachierdon simulans, in this tank. This tank was up and ran about 8 months without a single external food input since the fish were added to the tank. They were subsisting entirely on the epiphytic matter and microorganisms found in the leaves...Nothing else.

And they were as active, fat, and happy as any Green Neons I've ever seen.

In fact, they more than doubled in size since I first obtained them. Some of the fishes were shockingly emaciated and weak upon arrival, were rehabilitated somewhat in quarantine, but weren't "100%" when released into the display (yeah, I know- NOT a "best practice", but it was intentional for this experiment).

After a few weeks, this point, I couldn't tell them apart from the rest of their tankmates!

Oh, and they spawned twice!

Perhaps just luck...but weakened, malnourished fishes generally don't reproduce in our aquariums, so I think that something good was going on there!

Now sure, this was a relatively small population of little fishes in a small tank. The environment itself was carefully monitored. Regular water exchanges and testing were employed.

All of the "usual stuff" we do in an aquarium...except feeding.

Of course, I don't think that such a success could be replicated with fishes like cichlids or other larger, more predatory type fishes, like Knife Fishes- unless you utilized a large aquarium with a significant "pre-stocked" population of crustaceans, insects, and maybe even (gulp) "feeder-type" fishes.

I mean, I suppose that you could do this...

However, it is really a more successful approach with fishes like characins, Rasbora, Danios, some catfishes, Loaches, etc.-Especially the little guys.

So yeah, I believe that this concept is entirely replicable, and can be successful with many fishes.It's not some "miracle", or an excise in "giving hobby convention the middle finger"- it's simply a way to set the stage for an aquarium to provide for its inhabitants' nutritional needs.

By stocking your new aquarium with a healthy allotment of leaves and botanicals, perhaps "seeding" it with beneficial bacteria, worms, micro crustaceans, Paramcium, etc., and letting the tank "run in" for a few weeks prior to adding your fishes, you're doing just that.

That's the hardest part of this whole idea. Letting Nature do some of the work.

It requires patience, observation, and some planning. Yet, it's entirely possible snd not hard to execute. It may require creating tanks which embrace a completely different aesthetic AND function. Stuff like detritus, turbidity, decomposition, and biofilms will be things that you find not only interesting, but helpful and desirable, too.

To some extent, it's certainly a bit "contrarian" as compared to standard aquarium practice, I suppose. However, it's not all that "radical" a concept, right? I mean, it's essentially allowing Nature to do what she does best- cultivate an ecosystem...which she will do, if given the "impetus" and left to her own devices.

And it's not really "benign neglect", is it?

It's the facilitating of a process which has been going on in Nature for eons...a validation of what we experiment with on a daily basis in our "tinted" world. It's that "functionally aesthetic" thing again, right?

I think that, as we evolve into the next "era" of botanical-style aquarium practice, we'll see more and more interesting collateral benefits and analogs to the functions of natural aquatic ecosystems. We need to explore these characteristics and benefits as we develop our next generation of aquariums.

We invite you to experiment for yourself with this fascinating and compelling topic!

Stay inspired. Stay thoughtful. Stay curious. Stay patient. Stay skeptical. Stay observant..

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Considering the seasons...

The botanical-style aquarium challenges us.

It forces us to look at things a bit differently. To accept a different look, a different function, and to embrace Nature in a more intimate way in our aquariums that we typically do.

And, in order to make sense of it all, we spend a great deal of time examining the processes which occur when leaves and other botanicals are added to the aquarium.

And this is important, not only from an aesthetic standpoint, but from a functional/operational standpoint.

It definitely differs from our hobby practice in decades past, where the idea of throwing in materials that affect the water quality/composition was strictly a practice reserved for speciality hobbyists, like killifish breeders, Dwarf Cichlid keepers, etc., who wanted to create special conditions for breeding.

Nowadays, we're advocating the addition of such materials to our aquariums as a matter of course, for the everyday purpose of replicating natural processes for our fishes. We understand- or are attempting to understand- the impact on both our aquariums' ecology and the husbandry involved.

Yeah, sort of a different approach.

We add a lot of biological material to our tanks in the form of leaves and botanicals- perfectly analogous to the process of allochonous input- material is something imported into an ecosystem from outside of it. Exactly what happens in the tropical streams and rivers that some of us obsess over!

There's been a fair amount of research and speculation by both scientists and hobbyists about the processes which occur when terrestrial materials like leaves and botanical items enter aquatic environments, and most of it is based upon field observations.

As hobbyists, we have a unique opportunity to observe firsthand the impact and affects of this material in our own aquariums! I love this aspect of our "practice", as it creates really interesting possibilities to embrace and create more naturally-functioning systems, while possibly even "validating" the field work done by scientists!

And of course, there are a lot of interesting bits of information that we can interpret from Nature when planning, creating, and operating our aquariums.

It goes without saying that there are implications for both the biology and chemistry of the aquatic habitats when leaves and other botanical materials enter them. Many of these are things that we as hobbyists observe every day in our aquariums!

Example?

A lab study I came upon found out that, when leaves are saturated in water, biofilm is at it's peak when other nutrients (i.e.; nitrate, phosphate, etc.) tested at their lowest limits. This is interesting to me, because it seems that, in our botanical-style, blackwater aquariums, biofilms tend to occur early on, when one would assume that these compounds are at their highest concentrations, right? And biofilms are essentially the byproduct of bacterial colonization, meaning that there must be a lot of "food" for the bacteria at some point if there is a lot of biofilm, right?

More questions...

Does this imply that the biofilms arrive on the scene and peak out really quickly; an indication that there is actually less nutrient in the water? Is the nutrient bound up in the biofilms? And when our fishes and other animals consume them, does this provide a significant source of sustenance for them?

Hmm...?

Oh, and here is another interesting observation:

When leaves fall into streams, field studies have shown that their nitrogen content typically will increase. Why is this important? Scientists see this as evidence of microbial colonization, which is correlated by a measured increase in oxygen consumption. This is interesting to me, because the rare "disasters" that we see in our tanks (when we do see them, of course, which fortunately isn't very often at all)- are usually caused by the hobbyist adding a really large quantity of leaves at once, resulting in the fishes gasping at the surface- a sign of...oxygen depletion?

Makes sense, right?

These are interesting clues about the process of decomposition of leaves when they enter into our aquatic ecosystems. They have implications for our use of botanicals and the way we manage our aquariums. I think that the simple fact that pH and oxygen tend to go down quickly when leaves are initially submerged in pure water during lab tests gives us an idea as to what to expect.

A lot of the initial environmental changes will happen rather rapidly, and then stabilize over time. Which of course, leads me to conclude that the development of sufficient populations of organisms to process the incoming botanical load is a critical part of the establishment of our botanical-style aquariums.

Fungal populations are as important in the process of breaking down leaves and botanical materials in water as are higher organisms, like insects and crustaceans, which function as "shredders." So the “shredders” – the animals which feed upon the materials that fall into the streams, process this stuff into what scientists call “fine particulate organic matter.”

And that's where fungi and other microorganisms make use of the leaves and materials, processing them into fine sediments. Allochthonous material can also include dissolved organic matter (DOM) carried into streams and re-distributed by water movement.

And the process happens surprisingly quickly.

In experiments carried out in tropical rainforests in Venezuela, decomposition rates were really fast, with 50% of leaf mass lost in less than 10 days! Interesting, but is it tremendously surprising to us as botanical-style aquarium enthusiasts? I mean, we see leaves begin to soften and break down in a matter of a couple of weeks- with complete breakdown happening typically in a month or so for many leaves. And biofilms, fungi, and algae are still found in our aquariums in significant quantities throughout the process.

So, what's this all mean? What are the implications for aquariums?

I think it means that we need to continue to foster the biological diversity of animals in our aquariums- embracing life at all levels- from bacteria to fungi to crustaceans to worms, and ultimately, our fishes...All forming the basis of a closed ecosystem, and perhaps a "food web" of sorts for our little aquatic microcosms. It's a very interesting concept- a fascinating field for research for aquarists, and we all have the opportunity to participate in this on a most intimate level by simply observing what's happening in our aquariums every day!

Diversity is interesting enough, but when you factor in seasonal changes and cycles, it becomes an almost "foundational" component for a new way of running our botanical-style aquariums.

Consider this:

The wet season in The Amazon runs from November to June. And it rains almost every day.

And what's really interesting is that the surrounding Amazon rain forest is estimated by some scientists to create as much as 50% of its own precipitation! It does this via the humidity present in the forest itself, from the water vapor present on plant leaves- which contributes to the formation of rain clouds.

Yeah, trees in the Amazon release enough moisture through photosynthesis to create low-level clouds and literally generate rain, according to a recent study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (U.S.)!

That's crazy.

But it makes a lot of sense, right?

Okay, that's a cool "cocktail party sound bite" and all, but what happens to the (aquatic) environment in which our fishes live in when it rains?

Well, for one thing, rain performs the dual function of diluting organics, while transporting more nutrient and materials across the ecosystem. What happens in many of the regions of Amazonia - and likewise, in many tropical locales worldwide-is the evolution of our most compelling environmental niches...

The water levels in the rivers rise significantly- often several meters, and the once dry forest floor fills with water from the torrential rain and overflowing rivers and streams. In Amazonia, it means one thing:

The Igapos are formed.

All of the botanical material- fallen leaves, branches, seed pods, and such, is suddenly submerged. And of course, currents re-distribute this material into little pockets and "stands", affecting the (now underwater) "topography" of the landscape. Leaves begin to accumulate. Tree branches tumble along the substrate Soils dissolve their chemical constituents, tannins, and humic acids into the water, enriching it. Fungi and micororganisms begin to multiply, feed on and break down the materials. Biofilms form, crustaceans reproduce rapidly. Fishes are able to find new food sources; new hiding places..new areas to spawn.

Life flourishes.

So, yeah, the rains have a huge impact on tropical aquatic ecosystems. And it's important to think of the relationship between the terrestrial habitat and the aquatic one when visualizing the possibilities of replicating nature in your aquarium in this context.

This is huge, important stuff that any real "natural aquascaping" enthusiast needs to get his/her head around.

It's an intimate, interrelated, and perhaps even "codependent" sort of arrangement!

And of course, I think we can work with this stuff to our fishes' advantage!

We've talked about the idea of "flooding" a vivarium-type setup designed to replicate an Amazonian forest before. You know, sort of attempting to simulate some of the processes which happen seasonally in Nature. With the technology, materials, and information available to us today, the capability of creating a true "year-round" habitat simulation in the confines of an aquarium/vivarium setup has never been more attainable.

The time to play with this concept is now!

Sure, you'd need to create a technical means or set of procedures to gradually flood your "rainforest floor" in your tank, which could be accomplished manually, by simply pouring water into the vivarium over a series of days; or automatically, with solenoids controlling valves from a reservoir beneath the setup, or perhaps employing the "rain heads" that frog and herp people use in their systems. This is all very achievable, even for hobbyists like me with limited "DIY" skills.

You just have to innovate, and be willing to do a little work and experimentation.

And, you have to accept some new and very different aesthetics. You have to understand that when you flood a soil/clay/sediment-based substrate with water, it's going to be turbid. It's going to not be crystal clear and "aquarium culture perfect" in appearance.

When you make the mental shifts, you can just ponder the possibilities here! It's crazy!

As the display "floods", the materials in the formerly "terrestrial" environment become submerged- just like in Nature- releasing nutrients, humic substances, and tannins, creating a rich, dynamic habitat for fishes, offering many of the same benefits as you'd expect from the wild environment.

Recreating a "365 dynamic" environment in an aquatic feature would perhaps be the ultimate expression of an operational biotope-inspired aquarium- Truly mimicking the composition, aesthetics- and function of the natural habitat. A truly realistic representation of the wild, on a level previously not possible.

No more of that "diorama" bullshit.

Of course, I have no illusions about this being a rather labor-intensive process, fraught with a few technical challenges- but it's not necessary to make it complicated or difficult.

You'll have to be patient and make smaller, slower, incremental moves...I mean, you're starting out with a "dry" aquarium- a representation of a forest floor or grassland, letting it thrive- and then flooding it.

It does require some "active management", planning, and diligence- but on the surface, executing seems no more difficult than with some of the other aquatic systems we dabble with, right?

The transformation of dry forest floors into aquatic habitats provides a tremendous amount if inspiration AND biological diversity and activity for both the natural environment and our aquariums.

As always, it's best to look to Nature for your inspiration. You simply won't find much in the way of aquariums created to replicate these habitats and processes just yet.

And, man- Nature provides some really incredible inspiration for this stuff, doesn't it?

Flood pulses in these habitats easily enable large-scale "transfers" of nutrients and food items between the terrestrial and aquatic environment. This is of huge importance to the ecosystem. As we've touched on before, aquatic food webs in the Amazon area (and in other tropical ecosystems) are very strongly influenced by the input of terrestrial materials, and this is really an important point for those of us interested in creating more natural aquatic displays and microcosms for the fishes we wish to keep.

Characins, catfishes, dwarf cichlids, annual killifish- all have unique relationships with these habitats, which we can replicate, study, and interpret. They respond to the seasonal changes almost predictably.

And the seasonality in these wild aquatic habitats is perhaps the one feature that we as aquarists have yet to fully embrace and study. It's fascinating, intriguing...and dramatic, in many cases!

What can we learn from these seasonal inundations?

Well, for one thing, we can observe the diets of our fishes.

In general, fish, detritus and insects form the most important food resources supporting the fish communities in both wet and dry seasons, but the proportions of invertebrates fruits, and fish are reduced during the low water season. Individual fish species exhibit diet changes between high water and low water seasons in these areas...an interesting adaptation and possible application for hobbyists?

Well, think about the results from one study of gut-content analysis form some herbivorous Amazonian fishes in both the wet and dry seasons: The consumption of fruits in Mylossoma and Colossoma species was significantly less during the low water periods, and their diet was changed, with these materials substituted by plant parts and invertebrates, which were more abundant.

Fruit-eating is significantly reduced during the low water period when the fruit sources in the forests are not readily accessible to the fish. During these periods of time, fruit eating fishes ("frugivores") consume more seeds than fruits, and supplement their diets with foods like as leaves, detritus, and plankton. Interestingly, even the known "gazers", like Leporinus, were found to consume a greater proportion of materials like seeds during the low water season.

Mud and algal growth on plants, rocks, submerged trees, etc. is quite abundant in these waters at various times of the year. Mud and detritus are transported via the overflowing rivers into flooded areas, and contribute to the forest leaf litter and other botanical materials, coming nutrient sources which contribute to the growth of this epiphytic algae.

During the lower water periods, this "organic layer" helps compensate for the shortage of other food sources. When the water is at a high period and the forests are inundated, many terrestrial insects fall into the water and are consumed by fishes. In general, insects- both terrestrial and aquatic, support a large community of fishes.

So, it goes without saying that the importance of insects and fruits- which are essentially derived from the flooded forests, are reduced during the dry season when fishes are confined to open water and feed on different materials.

So I wonder...is part of the key to successfully conditioning and breeding some of the fishes found in these habitats altering their diets to mimic the seasonal importance/scarcity of various food items? In other words, feeding more insects at one time of the year, and perhaps allowing fishes to graze on detritus and biocover at other times?

Is the concept of creating a seasonally-influenced, "food-producing" aquarium, complete with detritus, natural mud, and an abundance of decomposing botanical materials, a key to creating a more true realistic feeding dynamic, as well as an "aesthetically functional" aquarium?

I'm fairly certain that this idea will make me even less popular with some in the so-called "Nature Aquarium" crowd, which, in my opinion, has sort of appropriated the descriptor while really embracing only one aspect of nature (i.e.; plants)...Hey, I love the look of many of those tanks as much as anyone...but let's face it, a truly "natural" aquarium needs to embrace stuff like detritus, mud, decomposing botanical materials, varying water tint and clarity, etc.

If you are intrigued by that, and not frightened of the looks and operational considerations, you'll love NatureBase "Igapo" substrate. After over a year of testing, it's now weeks away from release...It'll challenge you. It'll create turbidity. It'll color the water. It'll grow terrestrial grasses. It will foster biofilm formation. It'll get your creative juices flowing.

And we think it will reinforce the idea of what we mean by "functional aesthetics."

The aesthetics might not be everyone's cup of tea, but the possibilities for creating more self-sustaining, ecologically sound microcosms are numerous, and the potential benefits for fishes are many. Creating aquariums based on specific natural functions and benefits is something that I can't resist.

And, since a few of you asked...THAT is where Tannin is headed in the second half of 2020 and into next year. A new approach. A different look, products that might have you scratching your head in sheer terror AND delight! We're going to do a lot more pushing out into the margins of what is considered "normal" in the hobby.

And that's just where we like to be.

Stay excited. Stay focused. Stay inspired. Stay creative. Stay tuned...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

The impact of the land...the concept of terroir-and the nuances of Nature.

To me, perhaps one of the most elegant and compelling aspects of Nature is how the aquatic environments we love are so profoundly influenced by the terrestrial habitats which surround them.

There is a remarkable similarity between this intimate land/water relationship, and the world that we can create in our aquariums.

Every aquarium that we assemble is not only a unique expression of our interests and skills- it's a complex, ecologically functional microcosm, which is impacted by not only the way we assemble the life forms, but how we utilize them.

And of course, being the self-appointed "World's most prolific aquarium hobby philosopher," I have spent a fair amount of time ruminating on the idea, attempting to grasp the concept.

I think it simply starts with the materials that we use in our aquairums.

It is perfectly logical to imply that botanicals, wood, and other materials which we ultiize in our aquascapes not only have an aesthetic impact, but a consequential physical-chemical impact on the overall aquatic environment, as well.

We know this, because we see their impact on natural aquatic systems all the time, don't we? Every flooded forest, inundated Terre Firme grassland, every overflowing stream- provides a perfect example for us to study.

The land influences the water.

Each component of the terrestrial habitat has some unique impact on the aquatic habitat. Not really difficult to grasp, when you think about it in the context of stuff we know and love in other areas of life.

Wine, for example, has "terroir"- the environmental conditions, especially soil and climate, in which grapes are grown and that give a wine its unique flavor and aroma... Coffee also acquires traits that are similar: Tangible effects and characteristics, which impact the experience we get from them.

And of course, I can't help but wonder if this same idea applies to our botanicals?

It must!

Sure, it does.

I mean, leaves come from specific trees, imparting not only tannins and humic substances into the water, but likely falling in heavier concentrations, or accumulating in various parts of rain forest streams or inundated forest floors at particular times of the year, or in specific physical locales with in a stream or river. And of course, they provide the fishes which reside in that given area a specific set of physical/chemical conditions, which they have adapted to over time.

Is this not the very definition of "terroir?"

Yeah, sort of...right?

Actually, the idea makes perfect sense.

As we've discussed before, the soils, plants, and surrounding geography of an aquatic habitat play an important and intricate role in the composition of the aquatic environment. They influence not only the chemical characteristics of the water (like pH, TDS, alkalinity), but the color (yeah- tannins!), turbidity, and other characteristics, like the water flow. Large concentrations become physical structures in the course of a stream or river that affect the course of the water.

And of course, they also have important impact on the diet of fishes...Remember allochthonous input form the land surrounding aquatic habitats? And the impact of humic substances?

I can't help but wonder what sorts of specific environmental variations we can create in our aquarium habitats; that is to say, "variations" of the chemical composition of the water in our aquarium habitats- by employing various different types and combinations of botanicals and aquatic soils.

I mean, on the surface, this is not a revolutionary idea...We've been doing stuff like this in the hobby for a while- more crudely in the fish-breeding realm (adding peat to water, for example...), or with aragonite substrates in Africa Rift Lake cichlid tanks, or with mineral additions to shrimp habitats, etc.

In the planted aquarium world, it's long been known that soil types/additives, ie; clay-based aquatic soils, for example, will obviously impact the water chemistry of the aquarium far differently than say, iron-based soils, and thusly, their effect on the plants, fishes, and, as a perhaps unintended) side consequence, the overall aquatic environment will differ significantly as a result.

So, it pretty much goes without saying that the idea that utilizing different types of botanical materials in the aquarium can likely yield different effects on the water chemistry, and thus impact the lives of the fishes and plants that reside there- is not that big of a "stretch", right? I can't help but wonder what the possible impacts of different leaves, or possibly even seed pods from different geographic areas can have on the water and overall aquarium environment.

I mean, sure, pH and such are affected in certain circumstances - but what about the compounds and substances we don't- or simply can't- test for in the aquarium? What impacts do they have? Subtle things, like combinations of various amino acids, antioxidant compounds, obscure trace elements- even hormones, for that matter...Could utilizing different combinations of botanicals in aquariums potentially yield different results? You know- scenarios like, "Add this if you want fishes to color up. Add a combination of THIS if you want the fishes to commence spawning behavior", etc.

It sounds a bit exotic, a bit gimmicky, even, but is it really all that far-fetched an idea?

Absolutely not, IMHO.

I think the main thing which keeps the idea from really developing more in the hobby- knowing exactly how much of what to add to our tanks, specifically to achieve "x" effect- is that we as hobbyists simply don't have the means to test for many of the compounds which may affect the aquarium habitat.

At this point, it's really as much of an "art" as it is a "science", and more superficial observation- at least in our aquariums- is probably almost ("almost...") as useful as laboratory testing is in the wild. Even simply observing the effects upon our fishes caused by environmental changes, etc. is useful to some extent.

At least at the present time, we're largely limited to making these sort of "superficial" observations about stuff like the color a specific botanical can impart into the water, etc. It's a good start.

Of course, not everything we can gain from this is superficial...some botanical materials actually do have scientifically confirmed impacts on the aquarium environment.

In the case of catappa leaves, for example, we can at least infer that there are some substances (flavonoids, like kaempferol and quercetin, a number of tannins, like punicalin and punicalagin, as well as a suite of saponins and phytosterols) imparted into the water from the leaves- which do have scientifically documented affects on fish health and vitality.

When we first started Tannin, I came up with the term "habitat enrichment" to describe the way various botanicals can impact the aquarium environment. I mused on the idea a lot. (I know that doesn't surprise many of you, lol...)

Now, I freely admit that this term may be interpreted as much more of a form of "marketing hyperbole" as it is a useful description. However, I believe that the idea sort of resonates, when we think of the aquarium as an analog for the wild aquatic habitats, and how the surrounding environment- the terroir- impacts the aquatic environment, right?

And we hear the interesting stories from fellow hobbyists about dramatic color changes, positive behavioral changes, rehabilitated fishes, and those "spontaneous" spawning events, which seem to occur after a few weeks of utilizing various botanicals in aquariums which formerly did not employ them.

Sure, a good number of these interesting events and effects could likely be written off as mere "coincidences"- but when it happens over and over and over again in this context, I think it at least warrants some consideration!

We're slowly beginning to figure this stuff out.

Yeah, we’re artists.

Mad scientists.

Fish geeks.

Dreamers.

Yeah, artists.

And this stuff is really as much of an “art” as it is a “science”, IMHO.

There is so much we don’t know yet. Or, more specifically, so much we don’t know in the context of keeping fishes. We need to tie a few loose ends together to get a really good read on this stuff…until we get to the "Dial-a-River” additive stage ("Just add a little of this and a bit of that, and...".)

But we're getting there...At least in terms of understanding some of the tangible benefits of botanical use, besides just the aesthetics.

And it all starts with understanding the impact of...the terroir, right?

I think so.

I think that really sums up how much amazing stuff there is to extrapolate from observing the nuances of Nature.

Stay resourceful. Stay observant. Stay curious. Stay resourceful. Stay open-minded...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Don't even think about it...

I have some strong words and opinions about stuff I the aquarium world. And I am not afraid to share them with you on many days.

Today is one of those days. I needed to clarify, explain, and share some ideas.

Someone asked me the other day, rather innocently, I might add- how we "invented the idea of using botanicals in the aquarium." And, as I often do, after I cringed, I strongly and immediately corrected her, and explained that there is no single hobbyist or vendor who "invented" the idea. As long as people have been playing with aquariums, they've been throwing twigs and leaves and such into them- for various reasons and with various goals.

Nevertheless, it's not some "new practice" that Tannin Aquatics "invented."

I don't know why we as hobbyists need to assign a "creator" or "inventor" to everything. It's a bit weird. Now, if you want to give us "credit" for something, you can consider this:

The term "botanicals" didn't even exist as a contextual descriptor for this stuff in aquariums until about, oh, say 2015...when started Tannin and used the term to describe them. I appropriated this term, because the hobby needed a good descriptor of what this stuff was- especially if- as was my goal- we intended to make the practice of using them to create specific environmental effects in our tanks more "mainstream" in the hobby. I don't claim many things in the aquarium hobby, but I will claim this one.

Developing terminology and process are important parts of elevating hobby practices.Yeah, I suppose I'm acting rather boorishly about this because hobby "history" is important to me, and I want to set the history straight, because the "botanical-style" aquarium is still evolving, and we need to understand the difference between a more disciplined approach, and simply tossing some seed pods and such into a tank (as hobbyists HAVE been doing for many years.).

I'll say it again- WE DID NOT INVENT THE IDEA. No one did.

"Well, if you didn't "invent" the stuff, what the hell DID you do?" (as if it really even matters, BTW)

What we did do was to source, test, research, and refine the practices involved in utilizing botanical materials safely and more predictably in aquariums. And taking this stuff to a more serious level required not only the aforementioned work- it required some descriptors and definitions.

And of course, while we're on the subject of definitions: Botanicals are simply natural plant materials (generally leaves, bark, wood, and seed pods) that are used for both decorative and environmental enrichment purposes in our aquariums. "Scott, you sell twigs and nuts!" as one of my reef-keeping friends profoundly declared! I suppose he wasn't too far off, although I think that was a bit over-generalized, lol.

Now, the interesting thing is that, as hobbyists often do, we had to fight off the most "superficial" aspects of the description of our practice. We had to overcome the perception that utilizing botanicals was just some form of "aquascaping." I mean, sure, there is a large and significant aesthetic component to what we do. However, the most important aspect of utilizing botanicals in the aquarium is that they have the ability to influence the closed environment of the aquarium in a number of ways.

Many fishes (particularly South American fishes like Tetras, Cichlids and catfishes), as well as numerous African and Southeast Asian species (Gouramis, Bettas, etc.) benefit from the tannic acids and humic substances released by these materials into the water.

It has long been understood that there are actually some antifungal and possibly even antibacterial benefits to the properties inherent to "blackwater", resulting in healthier fishes and more viable spawns. And of course, botanical materials can help us recreate, to some extent, these conditions in the aquarium. And of course, it's not just environmental benefits that we see: Some animals, such as Plecos and even ornamental shrimp, derive supplemental nutrition from grazing on these materials.

And there are the expectations of what happens when we put these botanical materials into aquariums. We HAVE to consider these things. Not only because they impact our fishes' lives- but because they require us as hobbyists to make mental shifts to accept the function and appearance of these aquariums. This is perhaps different than almost any other aquarium approach out there at the moment. This is what we've spent a decade prior to starting Tannin, and the five years since we commenced business helping to flesh out, define, and explain.

Do you want a perfectly predictable sequence of occurrences and expectations for your botanical-style aquarium? Don't waste your time...Don't even think about it. Perfect predictability is just not a "thing" with these tanks. That being said, over the decades, we have noticed a specific group of phenomenon that occur with some regularity in botanical-style aquariums. Our experience positions us perfectly to help disseminate this information.

And THAT is the crux of why we spend SO much time and space discussing this stuff. We want expectations and experiences to be realistic and appropriate. That's our contribution to this game.

One of the things that we all experience with these types of systems is an initial burst of tannins, which likely will provide a significant amount of visible color to the water. If you're not using activated carbon or some other filtration media, this tint will be more pronounced and likely last longer than if you're actively removing it with these materials!

You might also experience a bit of initial "cloudiness" in your water. This could either be physical dust or other materials released from the tissues botanicals, or even a burst of bacteria/microorganisms. Not really sure, but it usually passes quickly with minimal, if any intervention on your part. Oh, and interestingly enough- not everyone experiences this...often this is a phenomenon which seems to happen in brand new tanks...so it might not even be directly attributable to the presence of the botanicals (well, at least not 100%). It might be other materials. It could be the sand, or dust/dirt from the other hardscape materials or the tank itself.

Of course, for those of you who will experiment with our NatureBase "Varzea" and "Igapo" substrates when they debut, you WILL experience cloudiness, turbidity, and tint as just part of the game. You'll either love it or hate it. But you will experience it! How much of a mental shift can you make to accept this as "normal" for your aquarium? That's the big question.

If you can't, our recommendation is that you don't even THINK about purchasing these substrates. Just don't.

As with so many things in our practice of botanical-style aquarium keeping, we need to turn to Nature for a "prototype" of how these habitats are SUPPOSED to look and function.

This is aquarium keeping at its most raw, elemental, and yeah- natural. In a strange way, it's actually "cutting edge"- and that means that the "expectation set" is new, different, and unlike anything we've been indoctrinated to accept in the hobby before. It will challenge you. Test you. Perhaps it'll even piss you off- because it's not "Nature Aquarium" sterile artistic beauty. It's hard for many hobbyists to accept. And that's understandable and okay.

If this shit bothers you...just don't even think about setting up one of these types of tanks.

Ouch.

So, that being said...what happens next in a typical botanical-style aquarium as it evolves?

Well, typically, as most of you who've played with this stuff know, the botanicals will begin to soften and break down over a period of several weeks. As we've discussed ad nauseum, you have the option to leave 'em in as they break down, or remove them (whatever your aesthetic sensibilities tell you to do!). Many "Tinters" have been leaving their botanicals in until completely decomposed, utilizing them as almost some sort of botanical "mulch", particularly in planted aquariums, and have reported excellent results.

Sure, the stuff will go through that biofilm phase before ultimately breaking down, and you'll have many opportunities to remove it...or in the case of most hobbyists these days- enjoy it for the food and biodiversity it brings to your system. And you will likely add new materials as the old ones break down...completely analogous to "leaf drop" which occurs in the wild aquatic habitats we seek to replicate.

I have never had any negative side effects that we could attribute to leaving botanicals to completely break down in an otherwise healthy aquarium. Many, many users (present company included) see no detectable increases in nitrate or phosphate as a result of this process. Of course, this has prompted me to postulate that perhaps they form a sort of natural biological filtration media and actually foster some dentritifcation, etc. I have no scientific evidence to back up this theory, of course (like most of my theories, lol), but I think there might be a grain of truth here!

We're going to introduce some products later in the Summer/Fall which will address the biological "operating system" of botanical-style aquariums in ways not previously done. Suffice it to say, they'll require not only mental shifts on your part, but some observation, experimentation, education, and dedication. Not into that? Don't even think about trying them. Really. It's okay.

Oh, speaking of expectations- one of the "givens" of botanical aquarium keeping is that you will likely have to clean/replace prefilters, micron socks, and filter pads more frequently. Just like in Nature, as the botanicals (leaves, in particular) begin to break down, you'll see some of the material suspended in the water column from time to time, and the bits and pieces which get pulled into your filter will definitely slow down the flow over time. Stuff breaks down, and you can't stop it. Well, not unless you're standing by with a siphon hose by your tank 24/7/365.

The best solution, IMHO, is to simply change prefilters frequently and clean pumps/powerheads regularly as part of your weekly maintenance regimen.

Not into that? Well, you know what I'm going to say...

And of course...this is the elegant segue into the part about your "weekly maintenance regimen", right?

Well, here's my simple thoughts on this: Do "whatever floats your boat", as they say. If you're a bi-weekly-type of tank maintenance person, do that. If you're a once-a-month kind of person...Well, you might want to re-examine that! LOL. Botanical-style blackwater tanks, although remarkably stable and easy-going once up and running, really aren't true "set-and-forget" systems, IMHO.

You want to at least take a weekly or bi-weekly assessment on their performance and overall condition. Now, far be it from me to tell YOU- the experienced aquarist-how to run your tanks. However, I'm just sort of giving you a broad-based recommendation based upon my experiences, and those of many others over the years with these types of systems. You need to decide what works best for you and your animals, of course...

Now, remember, you're dealing with a tank filled with decomposing botanical materials. I mean, what do you THINK is going to be "normal" for a tank like this? Good overall husbandry is necessary to keep your tank stable and healthy- and that includes the dreaded (by many, that is) regular water exchanges. As we pointed out, at the very least, you'll likely be cleaning and/or replacing pre filter media as part of your routine, and that's typically a weekly-to bi-weekly thing.

Just sort of goes with the territory here. Because, ya' know- leaves.

Oh, and during water exchanges, I typically will siphon out any debris which have lodged where I don't want 'em (like on the leaves of that nice Amazon Sword Plant right up front, or whatever). However, for the most part, I'm merely siphoning water from down low in the water column.

I'm a sort of "leave 'em alone as they decompose" kind of guy. And I'm not going to go into all the nuances of water preparation, etc. You have your ways and they work for you. If you want to hear my way some time, just DM me on Facebook or Instagram or whatever and we can discuss. It's not really rocket science or anything, but everyone has their own techniques.

And of course, regular water testing is important.

So, your testing regimen should include things like pH, TDS, alkalinity, and if you're so inclined, nitrate and phosphate. Logging this information over time will give us all some good data upon which to develop our expectations and best practices for water quality management.

Not just for the information you'll gain about your own aquarium and it's trends. It's important because we as proponents of the botanical-style aquarium movement need to log and share information about our systems, so we can develop a model for baseline performance of these systems, and continue to develop and refine "standards" for techniques, practices, and expectations about these tanks. You're a pioneer of sorts, regardless of if you perceive yourself to be one or not!

Don't like that aspect? Well, don't even think about setting up one of these tanks.

Ouch. I'm hitting hard this morning!

I am, because you need to understand that playing with botanical-style aquariums is more than just a "style" of aquascaping. It's not just about then look. In fact, the function- the very nature of what we do and want to achieve with these tanks is what dictates the "look." It's about process.

"Setting the stage" for the process to take its course is only the beginning. Then comes the part about letting goa bit. Allowing Nature to evolve our work. We can look on in awe, and take delight in what is happening.

To find little vignettes- little moments- of fleeting beauty that need not be permanent to enjoy.

And the changes...those earthy, perhaps inevitable changes which occur when terrestrial materials are submerged in water for an extended period of time? They're elegant- yet untamed...and not everyone's idea of "beautiful." Why? Largely because we don't control every aspect of the process; because we don't impose excessive amounts of order or influence to it.

We cede some of it to Nature...And that includes accepting the "look" as well.

It's hard.

Really hard for many.

Some people just "don't get it", and proffer that this is simply sloppy, not thought-out, and seemingly random. I recall vividly one critic on a Facebook forum, who, observing a recent botanical-inspired aquascape created by another hobbyist, commented that the 'scape looked like "...someone just threw in some pods and leaves in a random fashion.."

Yeah, this guy actually described the aesthetic to a certain (although unsophisticated) degree...but he couldn't get past the look, and therefore concluded it was, "...haphazard, sloppy, and not thought out."

A shame.

I think if he glanced at a natural habitat and then looked at the tank again, he'd gain a new appreciation. Or at least, a sort of understanding.

But on the other hand, that was the charm and beauty of such a conceptual work. The seemingly random, transient nature of such an aquascape, with leaves deposited as in Nature by currents, tidal flows, etc., settling in unlikely areas within the hardscape.

Allowing Her some of that control.

Not everyone likes this nor appreciates it. And that's perfectly fine. It's not the "best" way to run a tank. Just "a way."

With so many people worldwide starting to play seriously with blackwater, botanical-style tanks, we're seeing more and more common trends, questions, ideas, issues, and ways to manage them...a necessary evolution, and one which we can all contribute to!

Yet, if you're not into this...If you think setting up one of these tanks is just gonna be a cool "look" for your fish room, requiring little effort. If you're just trying to jump on someone sort of "trend"...Please- I beg you...Don't even think about it.

Help evolve the hobby.

Stay bold. Stay strong. Stay observant. Stay thoughtful. Stay diligent. Stay open-minded. Stay adventurous...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

"Any old log..."

Some of the most compelling things in natural aquatic habitats- and in the aquariums which we create to represent them- are large branches, fallen trees, and logs. The result of a tree, branch, or root system which finds its way into the water is a physical, environmental, and water-flow-dynamic-changing feature in the habitat.

I love fallen trees and branches.

I love what they can do. What they can bring to an aquatic environment.

I love how they inspire us.

I love the idea of doing an aquarium in which the primary feature is a big old piece of wood, covered in biofilm, algae, and other life forms.

Notice I didn't say "aquatic moss?" Why? Well, besides the fact that it's sort of an aquascaping contest cliche by now, I don't think it looks all that "authentic." Although I like the look of these features, personally, I have yet to see a moss-covered log in the Amazon region, or in an Asian blackwater swamp, and we need to accept- not fight- some of what really happens in Nature, and readjust our aesthetic sensibilities to understand what is really natural beauty.

It's not all neat and orderly and crisp green on brown.

It's just not.

As we've mentioned numerous times here, Nature is not exactly a neat and tidy, perfectly-ratioed place. Rather it's often a world of chaos, randomness, detritus, biofilms, and fungal growth.

I think we have to sort of "desensitize" ourselves from the stigma of "biocover" on our wood. Now, I know, this idea undermines a century of aquarium-keeping/aquascaping dogma, which suggests that wood in the aquarium must be pristine, and without anything going on it (outside of the aforementioned mosses, in the last decade or so).

And of course, that's really sort of antithetical to what happens in Nature!

When terrestrial materials fall into the water, opportunistic life forms, ranging from algae to fungi to bacteria- even sponges-will colonize the available space, eking out a living as they compete for resources. In addition to helping to break down some of these terrestrial materials, the life forms that inhabit submerged tree branches and such reproduce rapidly, providing forage for insects and aquatic crustaceans, which, in turn are preyed upon by fishes. Yeah, a food chain...started by a piece of tree that fell in the forested was covered by water during periods of inundation.

If you look at the way the "biocover" (such a generic term, wouldn't you say?) grows on these materials, it's obvious that it does so in a manner which helps it absorb light, dissolved oxygen, and nutrients from the water column. The largest, broadest surfaces are covered.

These mats of what many hobbyists would characterize as "unsightly growth" are some of Nature's most beautiful and elegant systems, optimized to exploit the dynamic environment in which they are situated. An enormous abundance of life is present, if we just take a few minutes to look for it.

Now, as a hobbyist, I do get it.

We like things orderly. We like to see things looking "pristine" and well-kept...and I understand that well. For decades I was the guy who you wouldn't see a speck of algae in his tanks...Like, none. My reef tanks were so clean looking that one of my friends jokingly suggested that "you could give birth in there..."

But guess what? "sterile" is not natural.

At least, not in most aquatic habitats.

I see how planted tank people take great care to optimize the environment for the plants, eliminating any algae they can find, in favor of lush plant growth. And that makes sense in that context. However, when I see systems comprised of perfectly "ratio-obeying" rocks, covered in mosses, with neat "lawns" of low-cut, perfectly manicured grass on the substrate, the word "natural" doesn't immediately come to mind.

Rather, I find them stunningly beautiful, much in the same manner as a finely-kept garden or planter box. A piece of art. Respect the enormous effort and talent that went in to planning, executing, and maintaining the tank. I take exception with the moniker of "natural-looking" ascribed to many such tanks. Natural, perhaps in the sense that plants and aquatic life forms are growing there...but that's about it, IMHO.

Nature is simply not neat and orderly. Not in the "design" sense. Nature does not correspond to our need to index and arrange color, growth forms, leaf shapes in their proper place, according to some artificial ratios and rules.

Nope.

Nature is based on a sort of chaos. Or, being able to take advantage of chaos, anyways.

It's based on living things fighting to survive in a world which is not forgiving of life forms that cannot adapt to their environment. And as such, it has a compelling, almost relaxing beauty all of its own.

This viewpoint and willingness to embrace this more functionally-aesthetic interpretation of Nature does not make me popular with some people, especially some in the aquascaping community, who feel that we are pushing the idea of "lax maintenance", "low concept" design, and "shoddy execution" (all actual words used by self-appointed "critics" to describe blackwater, botanical-style aquariums at one time or another over the years!).

I hate conflict, and have nothing but respect for most of these talented people, yet it seems we always receive some serious "rancor" from a few parties regarding our aesthetic. And frankly, I would rather spend more time on "The Tint" executing and creating content on some cool new ideas, but there is a valuable- and timely lesson to be learned here.

It's about acceptance, tolerance, and understanding.

I would imagine that the initial appearance of a botanical-style, blackwater aquarium makes it an easy target for those who are dogmatic, narrow minded and haven't got a clue on how these systems operate.

And let's be honest, I've never worked with a customer who created a botanical-style blackwater tank aquascape by just "tossing stuff in at random" (although that would be cool!). There IS a LOT of thought an planning involved I the execution of these systems. Remember, we're not strictly about aesthetics. We're about fostering natural function, and the aesthetics are just a part of the whole equation.

The aesthetics often become far more enhanced after the aquarium has operated a period of time, resulting in a look that is often a bit different than we might have originally expected!

Botanical-style systems are different. They allow Nature to do a fair amount of the work, unobstructed by our regular intervention. This frightens some people. Yet, it's the ultimate expression of the concept of wabi-sabi, which Takashi Amano admired so much and urged us to embrace for so long. IMHO, it's the most critical- and most disregarded lesson he ever taught. Please Google it.

Yeah, these systems force us to look at Nature as it is...not simply as we want it to look.

These systems are so contrary to the hyper-dogmatic, homogenized, rule-driven lane that many of these "critics" operate in, that they simply cannot comprehend why people create such aquariums! If it weren't indicative of a problem, it would be funny.

Plenty of thought, skill, and effort goes into creating one of blackwater, botanical-style aquariums. You people are damn good!

There is a reason why the idea of creating these types of aquariums is literally exploding worldwide. They offer huge opportunities to express creativity, and to learn and contribute to an important body of knowledge within this speciality. They aren't that much different than what are touted as "high concept" aquariums by some, requiring plenty of planning, understanding, and talent to create and manage.

The opportunity to look at a feature one sees in a natural habitat and recreate the look and function of it is more enticing than ever before, given this mental shift. We just need to look at these natural features, consider how and why they formed, and what advantages they offer the aquatic life forms which resides in the. A more "wholistic" approach, indeed.

And then, we simply need to execute, unencumbered by artificial "rules" imposed by hobby dogma. A huge mental shift.

It's what comes after the tank is set up that really starts to differ from more "conventional" aquascaping and aquarium management.

The acceptance of natural processes, regardless of their appearance is key. Making the effort to understand what is happening in our tanks, why it happens, and how these processes, if left "unedited", are exactly what happen in the wild aquatic habitats of the world.

A common "criticism" I hear from some people is that botanical tanks, with their brown water, biofilms, and decaying leaves, are a "cover" for "lack of technique" or "poor maintenance." To which I often respond, "Leave your 'scape alone for three weeks without touching anything on it, and I'll do the same with mine...lets see how much our tanks change."

Of course, there are never any takers among these critics, because they know that their tanks will "devolve" into what they would call "chaos" if they're not tending to it constantly. Some plants will overgrow others. Some will die back. The perfectly organized planting groups will fall by the wayside as the more dominant plants exploit the available resources. The botanical-style aquarium, which functions in a very natural manner, simply...continues to evolve. Leaves and pods decompose, fungal or biofilm growths wax and wane. Occasional strands of algae might pop up on a branch somewhere. Plants grow in the direction of light and nutrients. Just like in Nature, perhaps?

Fighting back nature does not make a tank "natural", IMHO.

Accepting it does.

And that requires talent, knowledge, and understanding on the part of the hobbyist.

And, just like accepting Nature, the hobby also needs to accept the fact that not everyone buys into everyone else's concept of what looks good, what's "cool", and what constitutes "natural" or whatever. Ironically, the highly talented people who unfairly criticize this style of aquarium are possibly ones who could contribute the most towards evolving them!

Why some people love to bash the efforts and interests of others is beyond me. No one "owns" the idea of aquascaping. There is no "right or wrong" here; criticisms of things we haven't even tried before are not helpful.

They frighten off some individuals from even trying new things; questioning new ideas. How is that helpful? To what end is this necessary? Now, in all fairness, it's a very small percentage of people who level such criticisms, but they are so vocal and venomous in their assertions that to not consider what they're saying and respond to them would be irresponsible on my part. We have received so much positive input, enthusiasm, and encouragement (not to mention, some awesome aquascapes!) from some of the world's most highly regarded aquascapers, that it's almost funny to hear such negativity...but, "people are people", right?

Guess the eternal optimist in me keeps thinking I can reach some of these people...not trying to convince them to create a blackwater/botanical aquarium; rather, to get them to simply understand that there is more than one methodology that can be used to create an amazing aquarium. To look to Nature not as just a "muse"- but as a teacher.

It's not that difficult a concept.

Enough divisiveness already! We're all aquarium hobbyists.

And we as hobbyists all need to really understand that the precious natural habitats that we ALL love so much offer a beauty, "order", and resilience all of their own, and that they evolved over time as the forces which act upon them except greater influence upon them.

Some of these forces are artificial and detrimental, like deforestations, siltation, runoff, and pollution. By making the effort to really understand how these habitats function in their un-adulterated state, we are gaining insights and appreciation that may help us do a better job at protecting them for future generations to enjoy.

Let's do a better job in the hobby of understanding each other. Let's do a better job of looking at Nature and appreciating the job it does, despite our predilection for wanting to do things OUR way. Let's do a better job of being more open-minded, more creative within the context of what Nature does. Let's do a better job in the hobby of understanding each other. We're all better off together, working with each other to push the boundaries of this wonderful hobby.

And it all starts by looking at what happens to an aquatic habitat when any old log, branch, or root falls into it. To see, study, and understand that the aquatic environment is influenced by so many unique factors- many of which we can interpret and foster in our own aquariums, is the key. To give Nature the space to "breathe" within our tanks will take us to entirely new places in the hobby.

It's not only interesting...It's transformational!

We just need to accept it.

Stay creative. Stay honest. Stay open-minded. Stay studious. Stay together. Stay inspired...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

After a rocky start, it's back to the bottom for us!

Well, if you've noticed lately, we're really starting to phase out rock on our website! It's pretty obvious...We've been blowing the stuff out at ahem, "rock bottom" prices lately to get rid of it! Surely you noticed, because we've never sold so much rock so quickly! Weren't aware? Well, you'd have to be "sleeping under a rock" to- okay, that's enough already!

Seriously, though, I'm finished with rock...at least, finished with selling the stuff on our site. (although we'll keep our "River Stones" and River Pebbles", 'cause I like them and they make sense!). Is this a sudden backlash against rock or something? Not really. I just don't like handling, sourcing, shipping, and selecting the stuff. It's a pain in the ass: expensive to ship, highly subjective to select, and difficult to get a good mix of sizes from our suppliers...so I'm done.

It also reminds me of things I hated about the coral trade...too many stupid names to keep up on, a lot of hype about any rock that some superstar 'scape uses, and a sort of lack of "romance" to me.

Oh, and the best reason?

It really isn't all that applicable to what we do.

As we delve deeper into the world of blackwater, botanical-style aquariums, I think it becomes more and more important for us to understand the wild blackwater habitats of the world. Specifically, how they form, and what their physical characteristics are. It's easy for us to just go the "cliche' route" and say that blackwater is water, "...which has a low pH caused by dissolved organic materials and looks the color of tea." You could just leave it at that. You know, the standard line used for decades.

Not untrue, but not really all that helpful in understanding exactly what it is, IMHO.

And more important, not helpful in understanding why it has these characteristics.

And there are some things which contribute to the overall habitat of blackwater environments- specifically, how they form.

Well,interstingly, it does sort of start with the study of rocks...Geology.

Hey, don't start yawning on me...

I should first start of by freely admitting that I sort of- well, dozed through the limited number of geology classes I took in high school and college, and never knew that the time I spent in those classes drawing pictures on the back of my notebooks and trying to figure out where to get the stuff I needed for that weekend's party would ever come back to haunt me decades later, when I'd have to re-familiarize myself with all of this stuff!

So, my understanding is limited, but I'll convey what I DO know to you here...And how it relates to our area of interest.

Blackwaters in areas like Amazonia (one of our fave locales, of course!) drain from an area known to geologists as the "Precambrian Guiana Shield", which is comprised of sediments include quartz, sandstone, shales, and conglomerates, stemming from the formation of the earth some 4.6 billion years ago. As a result of lots of geological activity over the eons, a soil type, consisting of whitish sands called podzol is formed.

Podzols typically derive from quartz-rich sands, sandstone, and other sedimentary materials in areas of high precipitation. (Hmm, like The Amazon!). Typically, Podzols are kind of shitty for growing stuff, because they are sandy, have little moisture, and even less nutrients!

A process called podzolization (of course, right? What the fuck else would you call it?) occurs where decomposition of organic matter is inhibited. Numerous microbes and plants consume some of the nitrogen, and while eaten by other organisms, convey what's left to the even lower-lying forest habitats.

The Amazonian blackwater rivers are largely depleted in nutrients, having passed through the lowland forest soils as groundwater, from which weathering has already occurred. As a result, layers of acidic organics build up. With these rather acidic conditions, a deficiency of nutrients further slows down the decomposition of organics. So, yeah- lousy soil for growing stuff...But guess, what? They form the basis of the substrate in many Amazonian aquatic habitats!

And the water which flows over this soil is what we call "blackwater", which achieves it's unique color from a really high content of dissolved humic substances- poor in nutrients and electrolytes. It's characterized by having sodium as one of its major cations (ions with fewer electrons than protons, giving them a positive charge), which means it has low alkalinity. Typically, the pH and electrical conductivity values are less than 5.0 and 25 μS cm–1, respectively (pretty freakin' low!).

So, to make a very long and intimidating story short, the physical characteristics of blackwater habitats are influenced as much by the geology as anything else!

That is to say, all of the dissolved humic substances which give these bodies of water their unique look are "enabled" by the geological properties of the region. And from the "trace element perspective" (the reefer in me), only Fe, B, Sr, Pb and Se present consistent concentration variabilities sufficient to influence the chemistry of these waters...Like, this water has very low concentrations of trace elements.

That's why you'll often see simple fine, white silica-type sands on the bottoms of so many Amazonian streams and rivers. They originate up in the Andes mountains and are transported by various means into the lowland areas. I mean, there is way more to this process than I can convey here- but it's a study in the relationship between seemingly unrelated elements and how they come together.

Now, I admit that this is probably more than you will ever care to know about how sand works in your fave blackwater habitats, but I think it's important to understand that it's all kind of related. In fact, it makes it a lot easier to understand how blackwater systems came to exist and function when you consider this "big picture" stuff!

And of course, we're a hell of a lot more interested in the "decaying vegetation" (you know, the leaves, twigs, seed pods...stuff like that!) which influences the waters.

So, using a quality substrate material which doesn't impact the pH or buffering capacity of the water to any great extent is important...The reality is that just having an awareness of what goes on in the natural aquatic habitats we love gives us a nice "leg up" on this stuff. You're obviously not going to use a strongly buffering substrate like aragonite or whatever to do the job in your low pH and alkalinity blackwater aquarium, right?

And then there is that question about utilizing rocks in your "igapo" aquascape...

Like, why don't you find rocks in these habitats?

As you know from my long-winded description above, I'm no expert-or even a novice- on geology or geochemistry, or anything in that subject area, for that matter....However, based on my research into this stuff, as related above, it goes without saying that these are hardly conditions under which rocks as we know them could form.

Oh, sure, you might find the random rock in the igapo that was washed down from the Andes or some other high-country locale in these forests, but it's a pretty safe bet that it did not evolve there. This also helps to explain why the blackwater habitats are generally low in inorganic nutrients and minerals, right?

So...if you're really, really hardcore into replicating an igapo, you'd probably want to exclude rocks- especially if you're entering one of those biotope aquarium contests, astute judges would (rightfully) nail you on scoring for falling back on your natural inclinations as an aquascaper and tossing some in.

I personally, of course, would be a bit more forgiving, but you won't find rocks in my igapo tanks!

Besides, there is something far more compelling and romantic about leaves, seed pods, and wood than there is about a bunch of rock, right?

Maybe?

Okay, don't answer that...

Yeah- you WON'T find any rocks in my "igapo" tanks...

Nope.

I just can't say that I]m really into them.

Rather, we choose to concentrate on the more "ephemeral" components of the habitat, and rightfully so!

Our ability to mimic this aspect of the flooded forest habitats is a real source of benefits for the fishes that we keep- and a key to unlocking the secrets to long-term maintenance and husbandry of botanically-influenced aquariums.

The transformation of dry forest floors into aquatic habitats provides a tremendous amount if inspiration AND biological diversity and activity for both the natural environment and our aquariums.

Flood pulses in these habitats easily enable large-scale "transfers" of nutrients and food items between the terrestrial and aquatic environment. This is of huge importance to the ecosystem. As we've touched on before, aquatic food webs in the Amazon area (and in other tropical ecosystems) are very strongly influenced by the input of terrestrial materials, and this is really an important point for those of us interested in creating more natural aquatic displays and microcosms for the fishes we wish to keep.

Creating an aquascape utilizing a matrix of leaves, roots, and other materials, is one of my favorite aesthetic interpretations of this habitat...and it happens to be supremely functional as an aquarium, as well! I think it's a "prototype" for many of us to follow, merging looks and function together adeptly and beautifully.

Way sexier snd more interesting to me than any "Iwagumi" layout everyone drools about...Far more compelling than some "new" rock with a stupid name that people get all emotional about.

I like roots, twigs, seed pods, leaves, wood, and soils