- Continue Shopping

- Your Cart is Empty

What would YOU do? (When the @#$% hits the fan)

Like many people "in the business" of aquariums, I field a lot of PM's, emails, etc. from customers who have issues with aquariums, fishes equipment, etc.- 99% of it is totally unrelated to our specific niche, but it's "fish stuff", and I'm a "fish guy", so, when we're not tearing our hair out getting your orders filled, it's our honor to respond the best that we can.

Part of the game. Yeah, we're fish geeks.

As fish geeks, we love to talk about "stuff" like "how-to's", tank selection, and which fish to get. And even problems. As a culture, fish geeks talk to other fish geeks and try to mutually figure out what went wrong and how to fix the problems. Which made me think...How would I- and you -handle certain things that crop up in our own tanks? What types of reactions do you make? Do you make quick, decisive ones- regardless of possible outcomes? Do you freak out and make "knee jerk" ones? Do you research and implement solutions slowly?

As someone who's "knee deep" in the fish world 24/7, I guess it's a pretty good exercise to periodically imagine certain situations with my fish stuff and think how I'd react/respond. And not a bad exercise for you, either. I mean, you're pretty much "24/7", too, right?

How would you respond to a couple these sorts of common fish-keeping scenarios?

1) You just purchased some new awesome fish from, well- whoever...You acclimated them carefully, dipped them, and placed them in your display tank. You know in your heart that you should have quarantined them, like every new purchase..but you're not feeling badly about your odds for success. That is, until a week or so later, when a couple of the fishes start "scratching" on rocks and wood in your tank, twitching around a bit, acting strangely...Could it be ich? so other disease? Stress? Something else? And to make matters worse, you nice similar behaviors from the other fishes in the tank. Yet, no physical outward signs of disease other than those..

Do you: /Freak out and dump medication- any medication- right into the display tank? /Launch a nasty accusation campaign against the vendor on social media, accusing him of selling you a sick or infected fish? /Dip and isolate, and inspect each fish? /Observe to see if the behavior continues? /Get all the fish out of your tank for an extended period?

Here's one for my reefer "homies":

2) Your water testing indicates that there is some trace of copper in your water. (For those of you who are FW "lifers", copper is to marine inverts and corals what kryptonite is to Superman"- toxic, and very bad news!) You have noticed that your corals haven't quite looked their best recently, so this is not entirely surprising. Of course, it's COPPER! What to do?

Do you: /Do a 100% water change?/ Go crazy on Poly Filter, Cuprisorb, and other removal media?/ Systematically look for all possible sources of the contamination?

Okay, I could go on and on and we can play 30 rounds of "What would you do...?" and you'd get the picture after the first go around. The bottom line is this: DO you take a more thoughtful, reserved, analytical approach to problems with your tank, or do you tend to be a bit more emotional, dramatic and panicked (okay, my fish friends tell me that I'm a bit of a "drama queen" at times, lol)?

There's no shame in being emotional about our aquariums...I mean, they're living things, and we have a lot of time, energy, and cold, hard cash tied up in them...They are, in many cases, a reflection of our personalities, and extension of our essence- just like the home we live in, our clothing, our cars, etc. (Okay, that sounds really "L.A.", but I AM a product of my environment, okay?).

The point is that, to us-our tanks are not just a piece of furniture to set and forget...

Which is why we tend to get so emotional about them. I've seen genuine online knock-down-drag-out fights about various fish-keeping subjects played out in bloody full color on online forums over the years...and they're sometimes less than entertaining- and occasionally, actually scary.

Perhaps we take stuff too seriously?

Or maybe, not seriously enough? Or…

I dunno, but I enjoy analyzing useless things, as you know. Seeing how people react to problems in their aquariums always makes me realize that I might be more "sane" than I think I am! Of course, this remains to be seen once the fishes start jumping, the corals start melting, and the plumbing seals start leaking in my own tanks!

As summer winds down and the start of "aquarium season" looms ahead in a month or so- and like millions of fish geeks worldwide, I will find myself spending excessively large amounts of my free time playing with my tanks again, I cannot help but think about the way I’m going to react now to the inevitable things that will go wrong…(“Arrghhhh…the siphon hose should be in the bucket, right? Oops.”)

You know- reality. Having a coral warehouse with concrete floors and floor drains was the ultimate fish geek luxury…I mean, when you spill some water, it’s like no biggie, right? Or in the office...okay- it's part of a fish business. Goes with the territory. Of course, at home- totally different ball game…Pricy hardwood floors, quality furniture, and the usual obstacles…Oh, and my wife.

Fortunately, my wife, who is the ultimate neat freak, bless her heart- totally gets the ins and outs of aquarium-keeping, including the calamities and emergencies that go with it- and knows my tendency to- you know- spill a 'little bit" of saltwater on the floors now and then.

That’s why we have lots of really good towels. And tarps.

Yup.

And of course, she knows me and my aquarium "urges" well.

I was "green lighted”, as they say in Hollywood, by my wife for yet another home tank…a new reef this time. And a revised blackwater tank with some different stuff. My current status: A bit out of practice…A billion ideas in my head…access to all sorts of cool stuff- and way to many enabling fish friends.

This is gonna be a fun year. And expensive. I can tell. Fasten your seat belts, please!

Stay calm. Stay cool. Stay collected.

And Stay Wet- er, DRY…

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Falling leaves and rising interest in leaf litter beds!

This comes as no surprise to you, I'll bet, but we have a fair amount of discussion in our botanical-minded blackwater community about the merits of leaving decomposing leaves in your tank versus taking them out. In fact, the last I’ve checked, over the years there have been a bout a dozen-plus discussion threads on our social media outlets, and perhaps 15 or so articles here in the tint which touched on this issue! Tongue in cheek, but this definitely represents the definitive "body of work" on the joys of decaying leaves in the aquarium. I defy you to find a hobby site which has discussed, analyzed, and- well- beaten the shit- out of this topic as much as we have over the past couple of years!

So, in the finest Tannin Aquatics tradition, let’s add one more piece to the discussion on decomposing leaves! Today, however, let’s think about how leaf litter “behaves” in the wild, and how we could emulate it in our aquariums. With perhaps a few new twists and insights that we haven't shared before.

DOWN GO THE LEAVES...

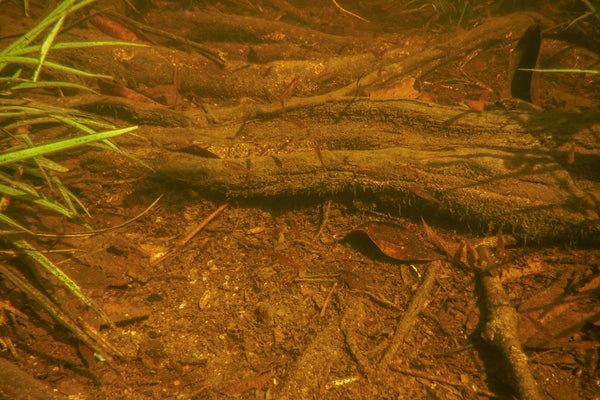

First off, leaf litter comes fro ma variety of trees in the rainforests of the tropical world. There is a near constant leaf drop occurring, which continuously “refreshes” the supply. In monsoonal climates, large quantities of leaves will drop during the dry season, and many will find their way into streams which run through the rain forest. In other habitats, such as the igapo forests of Amazonia,, the leaves fall onto the forest floor and accumulate, and are seasonally-inundated during the rainy season, creating an extremely diverse and compelling environment that we love so much around here!

The leaf litter in an igapo when inundated can be as much as 3 feet (1 meter) or more deep, with a huge amount of surface area available to bacteria (which create biofilms) and are often home to surprisingly large populations of fishes like Apistogramma, which use the shelter and “on-board” food offered by these habitats- to their advantage. And they’re vital to some of the small Elacocharax and other “Darter Tetras” which live almost exclusively in these niche habitats. Oh, and shrimp, too!

One interesting observation I’ve made over the years concerning adding leaves to the aquarium and letting them decay: Dead, dried leaves such as those we favor don’t have nearly the impact on water quality, in terms of nitrate, as fresh leaves would. I’ve routinely seen undetectable nitrate levels in aquariums loaded with botanicals. This is largely because dead, dried leaves have depleted the vast majority of stored sugars and other compounds which lead to the production of nitrogenous substances in the confines of the aquarium. Hence, leaving leaves in to fully decay likely reaches a point when the detritus is essentially inert, consisting of the skeletonize sections of leaf tissue which can decay no further. Dead leaves contain largely inert forms of polysaccharides, and are reach in structures like lignin and cellulose. Oh, and doing regular water changes can’t hurt.

AFTER THE FALL: WHAT HAPPENS NEXT?

To understand this more fully, let’s look at what happens when a leaf dies and falls into the water in the first place. At some point, the leaves of deciduous trees (trees which shed leaves annually) stop photosynthesizing in their structures, and other metabolic processes within the leaves themselves begin to shut down, which triggers a process in which the leaves essentially “pass off” valuable nitrogen and other compounds to storage tissues throughout the tree for utilization. Ultimately, the dying leaves “seal” themselves off from the tree with a layer of spongy tissue at the base of the stalk, and the dry skeleton falls off the tree.

As we know by now, when these leaves fall into the water, or are immersed following the seasonal rains, they form a valuable substrate for fungi to break down the remaining intact leaf structures. And the fungi population helps contribute to the bacterial population which creates the now-famous biofilms, which consist of sugars, vitamins, and various proteins which many fishes in both their juvenile and adult phases utilize for supplemental nutrition. And of course, as the fishes eliminate their waste in metabolic products, this contributes further to the aquatic food chain. And yeah, it all starts with a dried up leaf!

Interesting semi-anecdotal observations from my friends in the know, suggest that the biofilms for decaying leaves form a valuable secondary food for the fry of fishes such as Discus, Uaru, (after they’re done feeding on their parent’s exuded slime coat) and even Loricariid catfishes. And of course, all sorts of other grazing fishes, like some characins and even Cyprinids, can derive some nutrition from the fungi, bacteria, and small crustaceans which live in, on, and among the leaf litter bed. I’ve seen fishes such as Pencilfish (specifically, but not limited to N. marginatus ) spend large amounts of time during the day picking at leaf litter and the surfaces of decomposing botanicals, and maintaining girth during periods when I’ve been traveling or what not, which leads me to believe they are deriving at least part of their nutrition from the leaf litter/botanical bed in the aquarium.

AND, IN THE AQUARIUM?

In the aquarium, much like in the natural habitat, the layer of decomposing leaves and botanical matter, colonized by so many organisms, ranging from bacteria to macro invertebrates and insects, is a prime spot for fishes! The most common fishes associated with leaf litter in the wild are species of characins, catfishes and electric knife fishes, followed by our buddies the Cichlids (particularly Apistogramma, Crenicichla, and Mesonauta species)! Some species of RIvulus killies are also commonly associated with leaf litter zones, even though they are primarily top-dwelling fishes. Leaf litter beds are so important for fishes, as they become a refuge for fish providing shelter and food from associated invertebrates.

So, other applications in the aquarium for a leaf litter bed?

Well, let’s say you love the idea, don’t mind the tint, but simply don’t want any damn decomposing leaves in your hardscape (or whatever) aquarium? How about a leaf litter refugiium! Yup, a dedicated in-line vessel (usually an aquarium or commercially-available unit) which receives rich downstream flow from the display aquarium. You could stock it with leaves to your hearts’s content, and make sure that the returns are sufficiently screened off to keep the decomposing botanical materials from clogging the pump(s) or getting shot back into the display in significant quantities.

In a leaf litter refugium, you’d be able to place small fry, or fishes which require specialized feeding surfaces (like “Darter Tetras”) that only leaf litter can provide. It can form the basis of a “nursery”, breeding tank for Apistos and such, or simply be a supplemental display of some unique fishes which would otherwise be overlooked or out competed by the inhabitants of the main aquairum, while giving the display the benefits of tannins and humic substances. Besides, a refugium is an easy way to study and control this fascinating and dynamic niche environment in the aquarium! Win-win.

As we’ve discussed repeatedly over the past couple of years, there are so many benefits to painting leaf litter in the aquarium in some capacity. Wether it’s for water conditioning, supplemental food, speciality fishes, or simply for a cool-looking display, overcoming our ingrained aesthetic preferences and accepting the decomposing leaves as a natural, transitory, and altogether unique habitat to cherish in the aquarium is a decision that each one of us in “Tint Nation” has to make- but if you look at it from a functional aesthetic perspecitve, it’s pretty easy to appreciate the “beauty”, in my (very biased!) opinion!

And we've barely scratched the surfaces about leaves in brackish and saltwater habitats!

Stay creative. Stay open minded. Stay dedicated.

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

The way things go...

One of the coolest things about our hobby is the amazing progression over the years in both the state of the art and the technology that we embrace. Improvements that have enabled us to do things previously thought incredibly difficult or even, impossible, unfold daily on social media. And the progression seems to be accelerating constantly. What an awesome time to be a fish geek!

I was talking with a really pessimistic guy the other day, who basically trashed or dismissed every single development or change in the hobby over the last decade or so. According to him, nothing new or significant has happened, and pretty much everything new in the hobby is a "ripoff" of something that was “around before”… I think maybe he was jealous or something, but it was an attitude I’ve seen before in the hobby. Kind of a stupid attitude, really. After reading about and discussing some new product or evolved technique, you’ll often see these pessimists unleash comments on forums and other social media outlets like “That’s nothing new, really. ___________ had something like that a few years ago.” or “All that guy did was add______. It’s not really new.” Reminds me of when people boast that they, “thought of the idea for Facebook” or whatever, years ago; just never got around to building it. Right.

Attitude. Jealousy, maybe?

Comments and attitudes like this seem to overlook a few simple facts, and the workings of aquarium hobby progress is kind of interesting, so let’s look at this a bit closer. Did you ever think about how the technology and practices we routinely utilize in the hobby even came into being? Much of it is built upon achievements and developments from the past. This is not high-concept..I mean, it all started with a goldfish bowl, right? Sure, there are brand new technologies that trickle into the hobby all the time, yet many of the hottest new products and techniques of today arose as a result of someone looking at something that was already in existence and saying, “I can do better than that.” It’s the “better mousetrap” theory. Things evolve over time, often borrowing from existing technology or technique.

“Oh, he’s using that term “evolve” again…Sheesh, what is it with this guy?”

We don’t need to look too far back into the aquarium hobby’s past to see a prime example of this evolution, either:

Remember the “trickle filter?” Derived from sewage treatment technology, this venerable invention powered the reef systems of the mid eighties, placing the promise of the “miniature reef” into the grasp of almost every marine hobbyist. George Smit’s landmark series of articles in FAMA magazine in 1986, extolling this technology, literally helped launch the modern mass-market reef aquarium craze as we know it. By 1988, it seemed like the marine sector of the hobby exploded in popularity, with dozens of new filter manufacturers arriving on the scene almost monthly.

As the decade wore on, however, hobbyists and manufacturers saw fit to improve the trickle filters that were available at the time, creating new models with features like greater media capacity, more baffles to break up flow, and compartments to hold equipment like protein skimmers and reactors. Little improvements that provided increased performance. Nothing revolutionary, mind you- just “tweaks.” Yet, “tweaks” that represented significant improvements in performance from earlier iterations, promising better results for hobbyists. Eventually, it was determined that trickle filters were great at removing ammonia and nitrite, yet tended to allow nitrate to accumulate rapidly. In the nineties, many reefers embraced the belief that any accumulating nitrate could be a potential detriment to coral growth and long-term fish health, and almost overnight,“conventional” trickle filtration began to fall out of favor. Hobbyists everywhere began yanking the plastic filter media (bioballs, etc.) from their trickle filters.

With this little adjustment, he “trickle filter” became the “sump”, and was primarily the nexus for water treatment (mechanical and chemical) for the aquarium. (would have sucked to be in the plastic filter media manufacturing business about that time, huh? A definite candidate for the proverbial “buggy whip” of the 20th century, for sure!)

With no use for biological “towers” within this new school of thought, this feature began to disappear from filters. Calcium hydroxide (“Kalkwasser”) dosing was utilized to increase alkalinity and calcium and to precipitate phosphates… The “Berlin Method” of reef keeping had arrived, and a variation of this method has been more-or-less the state of the art ever since, with some adjustments and tweaks here and there. Once again, existing technology had “morphed” to accommodate the prevailing school of thought. The state of the art evolved, and so did the equipment. An idea from the past improved upon to accommodate the needs of the present.

In my opinion, some of us in the hobby are often too quick to chide such evolutionary steps as “copying” or “ripping off” existing ideas, when in reality, they are simply improving and building upon what was already there. This is the necessary progression of things in many cases. We didn’t make the leap from under-gravel filters to high-capacity sumps and hyper-efficient protein skimmers with electronic DC pumps, or from normal output fluorescent to programmable LED lighting, overnight. Hobbyists, manufacturers, and product designers looked at the prevailing technology of the day, assessed the needs of the hobby, and attempted to improve upon these existing technologies. Remember, many of these improvements are done to gain a market advantage over competitors. For example, if I make an easier to maintain filter, hobbyists are more likely to purchase my product. Further refinements take place all the time. Sometimes, aftermarket businesses spring up around improvements to existing mass-market products. Technology like 3D printing will further “democratize” this process, making it possible for small businesses to offer incremental improvements to established equipment…This is cool! This is how the hobby progresses.

It’s not just limited to the aquarium hobby, obviously. Think about everyday technologies, such as telephones. When the cord on the phone was cut, it changed the way we communicate as a species. Improvements in technology revolutionized the way we could quickly interact with others and gave us the “smart phones” that pretty much run our lives. They allow us to talk, write, text, send photos, stream video and shop effortlessly and instantaneously with others, creating true global communication once though impossible. We take it for granted.

Need more proof that change and progression in our hobby are often the result of evolution? Look no further than one of my longstanding favorite hobby topics- reef aquarium aquascaping! Those of you familiar with my rants from the saltwater world know that I am no lover of the ever pervasive “wall of rock”, which is essentially a large quantity of live rock, more or less stacked end-to-end in the aquarium. It’s been utilized as the “default” aquascaping configuration since the beginning of the reef aquarium hobby. In my opinion, it’s outdated, uninspired, functionally detrimental- and just unnecessary. I feel so strongly about this because, among other reasons, I understand its history.

Back in the 80’s, “live rock” was a breakthrough in aquarium management. Biological “filtration” and diversity of life were considered revolutionary concepts in aquaria. It was widely believed that you needed “x” number of pound per gallon of aquarium capacity to achieve these results, so when we set up our tanks, we dutifully dumped tons (literally, in some cases) of rock into them! Even though water capacity, swimming area, and flow were often compromised with this configuration, it was a widely held that the benefits were far greater than any potential downside.

Over the years, however, it was discovered that we really don’t need all that rock for biological filtration, and that you could utilize other techniques (use of refugia, protein skimming, macroalgae) to help efficiently process nutrients in our aquaria. Hobbyists began to experiment by creating systems with less rock. With the better understanding of biological processes and their affect on husbandry that we developed over the years, water volume and movement have taken on greater significance, and hobbyists began to utilize far less rock in their aquascapes, unless their design called for it. The “rock wall” was no longer considered the “only way” to run a reef system, and the concept of reef aquascaping has evolved dramatically, experiencing a real renaissance of sorts.

Oh, and there’s pretty cool artificial live rock now, too. Another “evolution!”

Inspiration is an “open source”, and innovation is for anyone to embrace. It can come from anywhere, at any time. Some aquarium technologies, such as lighting, borrow from other industries or fields of endeavor, whereas others, such as the development of new food products, arise out of knowledge and experience gained within the fields of marine science and aquaculture-and good old hobbyist experience as well. Ideas, technologies, and technique “cross-pollinate” between fields, and the changes benefit us all. Looking to change the hobby? Look at the world around you!

There is no great “hobby hegemony” that seeks to keep ideas and progression in the hands of some chosen few. These days, anyone with an idea and determination can forge a new path for the hobby. Think about this for a while: As a fan of the blackwater/botanical-style aquarium “movement”, you’re actually a participant in the progression in the hobby! You’ve got a front row seat to the revolution, and your comments and questions do not go unnoticed by manufacturers, fellow hobbyists, and industry people. You can make the change happen! You are doing it now!

So, the next time you might be tempted to criticize someone’s new hobby idea or product because it seemingly ”borrows” from something already in existence, realize that you’re merely seeing the evolution of the hobby at its flash point. Don’t just chide the development because part of it seems derived from something familiar. Embrace it, enjoy it, and utilize it…. improve it.

Stay creative. Stay progressive. Stay forward-thinking.

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Those most common of mistakes...and how to fix them! Advice for advisors...

(The last installment- I promise- of what has been a sort of "preachy" series of "dissertations" of late on the hobby of late! Had to get some stuff out of my system, I suppose!)

I've had the good fortune to be in this hobby my entire life, and to work with a lot of incredibly talented people during that time- most more talented than I could ever hope to be. Over the years, I've seen countless hobbyists find incredible levels of success, while others have found nothing but continuous failure. Seriously. Now, I have a hunch that there are things we can do to avoid failures in the hobby. Among those who had the most difficulties in the hobby, I've found a few "commonalities", if you will- some things that those who struggle repeatedly seem to do. Many of these are things that can be prevented or avoided, creating happier outcomes for everyone!

Obviously, most of you reading this won't need this advice personally (I hope). However, many of you find yourselves in a position, now and again (or more often) as "mentors" or "Admins" on forums and in clubs, to advise other hobbyists...And sometimes, it's nice to have some additional viewpoints to draw upon in order to be a better helper...So, I offer these to you for that purpose!

Here are 4 of what I feel are some of the most common "fatal" aquarium-keeping mistakes and how you can help others avoid/fix them! (Sort of written from the context of advising YOU, but apply appropriately to those you counsel, of course...)

1) Not trusting your instincts- or "If they say it's supposed to be done this way than I better do it that way or else!"- Sure, starting an aquarium can be a bit duanting- we all know it can be expensive! It's super easy to second guess yourself as the challenges mount, but it's really important to "go with your gut" on some things and just forge ahead if you believe in what you're doing. Just because "they" say it's supposed to be done this way doesn't mean that a variation or slightly different take on "it" won't work. I mean- look at us here...I'm just sayin'... Obviously, being arrogant is not a good thing, but you need to be confident in your skills and beliefs. As long as your idea isn't completely absurd (like using a radioactive isotope to heat your system), environmentally wasteful/morally distasteful (stocking a display of large predatory cichlids with expensive, small Tetras), or downright dangerous (keeping an Electric Eel touch tank in a preschool classroom aquarium), then I say take a chance and go for it! You might just be able to show others a new way of thinking...Don't accept the status quo "just because..."

2) Biting off "more than you can chew.."- It’s awesome to start a new tank loaded with the latest gear, advanced lighting, crazy plants, and uber-rare fishes. That being said, I’ve seen a lot of well-heeled, well-intentioned, but totally unprepared hobbyists crash and burn spectacularly with mega-priced setups that they simply did not have the experience to operate on a sustainable basis. These were often accompanied by amazing “build thread” and displays of expensive equipment along the way (which I touched on in yesterday's blog about patience...). Once things get underway, the reality is that a newbie hobbyists may not have the fundamentals to operate a 500 gallon mega tank, or hyper-sophisticated smaller tank, particularly if he or she has had little experience with a much smaller. less sophisticated system.

Look, I’m not discouraging mega-dream tanks, build threads and such…What I AM discouraging is jumping headlong into mega-pricy, highly complex systems that you simply cannot effectively operate long term. You gotta dream big! However, think of this somewhat sobering reality: If you can’t deal with hair algae and environmental stability in your 50 gallon tank, there’s no way you’ll be able to deal with them in your 500 gallon tank…trust me. Sure, you can learn...but in the mean time, at the very least, hire a competent aquarium service company to assist you if you’re simply not experienced enough to manage such a behemoth or technically-challenging system. Enough said.

3) Not soliciting advice from others- Okay, almost the antithesis of #1, but really, I’m talking about interaction and camaraderie. We can certainly impress upon our friends who are struggling that, in this vast, internet-enabled hobby of ours, it’s very unlikely that there isn’t someone out there who has experienced the same thing they are during his/her startup. There are so many innovative and bold hobbyists out there that it’s quite likely someone has been in his/her shoes before, and can offer some great, solid advice based on experience- not regurgitation of some old third hand information. May be it's YOU! Get out there on the forums and chat it up with other geeked-out hobbyists! You might just make some friends- or worse yet- learn a few things you may not have known! Yikes!

4) Expecting stuff to be "easy"- Wow, I sound like a buzzkill, but the reality is that the hobby is complex. I mean, not only are you dealing with plumbing, hardware, and construction- you have the other variable of live animals and their needs, reactions, and issues. You know, living things. Nature. Unpredictability. A lot of "moving parts" in an aquarium- literally! You can easily be tripped up by something as simple as adding the wrong animal, or misreading a test kit and making an ill-fated “correction” to you water chemistry…A lot of stuff can go wrong quickly.

That being said, it’s not all doom and gloom, and we need to preach this to neophytes- but the reality is that creating a great aquarium isn't ridiculously easy- and it’s not always cheap, either. (My industry people readers finally have something to be happy with me for!). To do it right involves research, effort, planing, observation, patience, and skill building- things that aren’t just handed to you. It’s part of the delightful "learning curve" of the hobby. Trust me, an avoidable ich outbreak or hair algae infestation in your planted dream tank is about as awful as it gets- but the skills you’ll acquire while combatting it will help you to be a solid resource for other hobbyists; a grizzled veteran of the aquarium universe that can make life better for a lot of other hobbyists.

Nothing’s ever wasted in the aquarium hobby, really.

Okay, there are doubtless countless other potentially “fatal” mistakes in aquarium keeping, but these are a few that I see all the time, as you no doubt do, as well…If we make it appoint to learn from our mistakes, and to share our hard-won knowledge with other hobbyists in a gentle, but supportive way- the hobby will continue to be an amazing place where we get to live our our dreams every day!

See you soon..Stay happy, stay educated..Stay patient with newbies...

And Stay Wet!

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Celebrating patience. Embracing the evolution. Taking the time.

I think that we- as a hobby, are not doing a good enough job celebrating the process of creating aquariums, and enjoying them at every stage.

I think we celebrate the “finished product” and fail to celebrate the joy, the heartache, the time- and the patience- the journey-which go into an aquarium. I think we create an "urgency" to get to some destination. And further, I don't think we as a hobby do enough to recognize the telltale signs of hobbyists going too fast..

If you spend time on forums, you’ll see evidence of this all over the place.

You see this in aquarium “build threads” (which are pretty cool, I admit), but many of them seem to exude an underlying feeling of “impatience”- a sense that there is a “destination” to get to- and that the person posting wants to get there really quickly! I see these in reef keeping forums constantly, and they follow a very predictable path. They start out innocently and exciting enough- the tank concept is highlighted, the acquisition of (usually expensive) equipment is documented, and the build begins. The pace quickens. The urgency to “get the livestock in the tank asap” is palpable. Soon, pretty large chunks of change are dropped on some of the most trendy, expensive coral frags- or worse yet- colonies- available.

Everyone “oohs and ahhs” over the additions. Those who understand the processes involved- and really think about it- begin to realize that this is going too fast…that the process is being rushed…that shortcuts and “hacks” are cherished more than the natural processes required for success. Sure enough, within a month or so, frantic social media and forum posts are written by the builder, asking for help to figure out what his/her expensive corals are “struggling”, despite the amount spent on high-tech equipment and said corals from reputable vendors.

When suggestions are offered by members of the community, usually they’re about correcting some aspect of the nitrogen cycle or other critical biological function that was bypassed or downplayed by the aquarist. Usually, the “fixes” involve “doubling back” and spending more time to “re-boot” and do things more slowly. To let the system sort of evolve (oh- THAT word!) The “yeah, I know, but..” type of responses- the ones that deflect responsibility- start piling up from the hobbyist. Often, the tank owner will apply some misplaced blame to the equipment manufacturer, the livestock vendor, the LFS employee…almost anyone but himself/herself. And soon after, the next post is in the forum’s “For Sale” section, selling off components of a once-ambitious aquarium. Another hobbyist lost to lack of patience.

Patience.

We can speed up some processes- adding bacterial additives to our new aquariums to “jump start” the nitrogen cycle. We can utilize nutritive soils and additives to help give plants the nutrition they need from day one. We can densely plant. All of these things and more are ways we have developed to speed up the natural processes which occur in our aquariums over time. They are band aids, props- quick starts…”hacks”, if you will. But they are not the key to establishing a successful long-term-viable aquarium. Ultimately, nature, the ultimate "editor"- has to “approve” and work with any of the “boosts” we offer. Nature dictates the pace.

It’s a hobby "cultural" problem, IMHO.

It doesn’t apply to everyone- it’s not always a devastating ending. However, it happens often enough to affect the hobby as a whole, especially when someone drops out because they went in with unrealistic expectations brought about by the observations they make every time they open up their iPad. We can correct this, relatively easily, I think.

The problem is, we as a hobby love to highlight the finished product. We document and celebrate the beauty of the IAPLC champion’s ‘scape. But we minimally document the process that it took to get there. The reality is that the journey to the so-called “finished product” is really every bit as interesting as the finished product itself! It’s where the magic lies. The process. The journey. The time. The evolution. The patience.

Sure, these aspects don’t make for the best “optics”, as they say in politics. You can’t show an empty, cloudy aquarium on Instagram or Facebook and get 400 “likes” on the pic. Sadly, acceptance from others of how cool our tanks are is a big deal for many, so sharing an “under construction” tank is not as exciting for a lot of people, because we as a hobby celebrate that “finished product” (whatever it is) more than the process of getting there.

We simply need to celebrate patience, the journey, and the “evolution” of our aquariums more. After a lifetime in the hobby it’s pretty easy for a guy like me to see when things are going in a direction that may not give the happy outcome my fellow hobbyists want. I see this just as much in the freshwater world as I do in the reef world. Lets savor the journey more!

I’ve laws found it somewhat odd to see those amazing high-concept planted tanks broken down i their prime by the owner, to start a new one. I guess it’s part of the culture of that niche…a sort of self-imposed “termination” when something new is desired. The “process” is about hitting certain benchmarks and moving on, I suppose. (and if you only have one tank and 500 ideas, and the goal is to enter it into a new contest, it makes sense) And we have to respect that. But we also have a duty to explain this to newcomers. We have to let people know that, even in one of those seemingly “temporary” displays, patience and the passage of time are required.

Part of the reason why we celebrate the “evolution” of blackwater, botanical-style aquariums here at Tannin Aquatics is because the very act of working with one of these tanks IS an evolution. A process. A celebration of sensory delights. An aquarium has a “cadence” of its own, which we can set up- but we must let nature dictate the timing and sequencing. It starts with an empty tank. Then, the lush fragrance exuded by crisp botanicals during preparation. The excitement of the initial “placement of the botanicals within the tank. The gradual “tinting” of the aquarium water. The softening of the botanicals. The gradual development of biofilms and algae “patinas”. Ultimately, the decomposition. All part of a process which can’t be “hacked” or rushed. Mother Nature is in control.

And, yes- we see impatience here, too. We need to stress the process as much as the “finished product” (whatever that might be in this instance). We constantly talk about this.

We see that people come in with some expectations based on the tanks they see. Human nature. Yet, we stress the aesthetics of the tank during the “evolution” as part of the function, too. We celebrate biofilms, brown water, and decomposition. It’s the very essence of Amano’s interpretation of Wabi-Sabi- the celebration of the transient nature of existence. And I get it. Not everyone appreciates the zen-like mindset required to truly enjoy a blackwater, botanical-style aquarium. Not everyone finds the decomposing pods and tinted water alluring. The fact that it closely replicates the natural Amazonian igarape or an Asian blackwater stream is of little consequence for the hobbyist who dislikes decomposing leaves and such, and wants a more “artistic” look.

And, the when the reality sets in that, in order to keep the tank looking exactly like it did when it was new, with crisp leaves and sparkling botanicals, it requires a constant amount of care and replacement of materials, the appeal could be lost to some. The “evolution” aspect of this type of tank, and the aesthetic and mind set hat goes with it, are not for everyone.

And that’s okay.

We celebrate the process. The evolution. Savor the time it takes to see a tank mature in this fashion. We love new tanks, just starting the journey, because we know how they progress if they are left to do what nature wants them to do. We understand as a community that it takes time. It takes patience. And that the evolution is the part of the experience that we can savor most of all…because it’s continuous.

As a hobby in general, we need to document and celebrate the process. We need to have faith in nature, and relish the constant change, slow and indifferent to our needs though it may be. We need to emphasis to new and old aquarists alike that, in this 24/7/365 intent-enabled world we’re in- that patience, time, and evolution are all part of the enjoyment of the aquarium hobby. The smell of a brand new tank. The delight at the first new growth of a plant. The addition of the first fishes. All are experiences on a road -a journey- which will forever continue. As long as we allow the processes which enable it to do so.

Be kind to yourself. Document. Share. Savor.

Stay patient. Stay generous. Stay honest. Stay curious.

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Along the (grassy) shoreline...

I'm becoming more and more obsessed with the habitats where land and water meet. I mean, I always was, because there is something extraordinarily compelling about them to me. Now, more than ever, I'd love to start playing with this concept in some tanks.

With the launch of "Estuary", we've seen more and more interest in the mangrove thicket habitats, which encompass both the aquatic and terrestrial component.

I'm equally fascinated by Asian and Amazonian streams and marginal areas, specifically the areas where land meets the water. Okay, so ripariums...or paludariums...However, with much greater emphasis on the aquariums, not necessarily 50/50 land to water, ya know? Would that simply be a "lower water level aquarium display?" Whatever. You can call it what you want to, but the idea of replicating shorelines is compelling to me.

Why?

*The soils and plants of the terrestrial environment have a direct and significant impact on the aquatic environment. Consider the igarape and igapo habitats- essentially flooded forest floors.

*The plants which grow along the waterline in these habitats provide shade, protection from aerial predators, and the occasional fruit or seed pod, which fishes utilize for food, shelter, or foraging.

*Terrestrial insects inhabit these plants and grasses, often falling into the water, providing a food source for many different small fishes. With some of their larvae often having an "aquatic phase", this makes some of these insects a sort of "on-site" supplemental food production source!

Now, I'm thinking a lot about the amazing work that some of our friends in the vivarium world do. Specifically, the use of tree fern "mats", lichen, Sphagnum and other mosses and such to create a sort of "rainforest" background for their work. These are spectacular, especially when planted with bromeliads, orchids, etc. What cues can we take from them? I think utilizing these materials on the "topside"- even in "almost full" aquariums, would really reinforce the water/land relationship and create a dramatic aesthetic. Who has had long-term experience with some of these materials (specifically, the dried lichens and mosses) when partially submerged?

I realize some may gradually (or perhaps, NOT so gradually) break down in an aquatic environment...they will definitely add some sort of "tint" to the water...I know this from playing with them in the past in displays.

When we talk about plants, it certainly doesn't have to be as high concept as what our frog and vivarium friends do in their displays.

I'm thinking that just having some plants like Philodenron, etc. "rooting" in the water, with their extensive root tangles, creates the sort of vibe we're talking about, while providing "functional" benefits of nutrient absorption, etc. for the aquarium. We could utilize some of the commercially available riparium planters, or simply let them "dangle" in our tanks, to create a cool look.

The idea of using terrestrial soils in aquariums in our substrates is something we've touched on several times. Our planted tank friends have much experience with this. I'd like to see us utilize these soil mixes to accent the "above and below" of our displays. Combinations of these materials (contained in various ways) could create an interesting functional AND aesthetic terrestrial component that could influence the water chemistry and ecological diversity of our systems.

Our vivarium friends commonly cultivate insects such as "Springtails" in their natural displays to provide supplemental food sources for their frogs and other animals living in their displays. We can take some cues here, and "inoculate" our "land/water matrix" with some insects, such as wingless fruitlfiles, worms, etc. to create an "onsite" supplemental food source.

Of course, we could use a refugium in line to accomplish this as well, but for this discussion, the idea of using a "terrestrial" component in our systems is kind of cool, IMHO! I mean, some of you may not like the look of creepy, crawly insects around your aquarium (and your "significant other" may not, either!), so the "out of site" refugium may be a better call for many of us!

Replicating the interaction of the land and water in a display is by no means revolutionary or new. However, the idea of doing this in a "full" or "near full" aquarium is a little twist on the paludarium theme, and creates some new challenges AND benefits for the aquarist. We'll have to think about how to contain soils, mosses, etc. in a relatively "full" display, and the absolute interaction between both environments is part of the game.

The opportunity here is not only to create a realistic, compelling display- it's to further unlock some of the secrets of nature and study the interactions between land and water. What cool ideas have you thought of, and how would you incorporate some of them into your display?

Stay studious. Stay innovative. Stay creative.

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

The other direction...

As I've evolved as an aquarist, I seem to have taken a more easygoing approach. Okay, I have an opinion on like everything, but I am overall pretty laid back.

Like, I've found things that work for me, and I've developed an increasing level of disdain for "rules" and dogma in the hobby. I mean, I agree that some hobby things need discipline and detail. However, I think we take it a bit too far in the other direction sometimes. And we've gotten so used to this that I think we might even make assumptions about assumptions!

Case in point...

I was talking to someone last week who was entering his aquarium in a biotope aquarium contest. He was very concerned about having materials that were from a specific habitat in his display. I totally understand, and in the interest of full disclosure, I explained to him that Catappa, Guava, and most definitely Magnolia leaves would not be found in the specific South American biotope he was trying to represent. He proceeded to tell me how this put him in a real quandary, because the leaves might disqualify him if he uses them. Of course, I told him not to use the leaves in his display (I mean, what else could I tell the guy, right?).

He then asked about a couple of different seed pods, one of which does hail from South America, but is also found in other tropical locales around the world. And he felt it would be too "risky" to include them, as well. This painful process went on an on for a while, as he proceeded to analyze every piece he thought would look great in this biotope, only to have to reject one after the other because they were not actual materials found in the precise habitat he was trying to represent in his entry. Good discipline on his part.

Respect.

After our conversation ended, I reflected a bit. I mean, it was an interesting one. He had to fit a certain set of guidelines for a biotope aquarium, in which authenticity is of paramount importance. I get it. On the other hand, I started thinking about some of his concerns and I kind of had to laugh to myself. I mean, sure, Catappa, Guava, and Magnolia leaves are NOT found in the habitat he was replicating...No argument there. However, once these start to break down a bit and become covered in biofilm, I'm thinking that no one but the most observant botanist or scientifically-trained river traveler would be able to discern exactly what variety they were. One leaf could represent another or another, right?

And further, I was thinking, "Does it truly matter?" I mean, you can't possibly tell me that the judges will know every species of tree which could possibly drop a leaf or seed pod in this Venezuelan stream you're thinking of representing- and discern that these decomposing pieces are NOT them...Oh, and how DOES one legally obtain supplies of fallen leaves from specific Amazonian jungle locales?" (And if you know, let me know, because I've been working on this for years now..!)

Just so you know, my bad attitude had absolutely nothing to do with him spending time chatting and not purchasing $20 worth of stuff from me. Stuff like that doesn't bother me, Mr. "I-look-at -the-long-term-on-everything." mindset. No. Rather, I think it stemmed from my irritation that this guy gave the impression that people are putting out some serious dogma that is not only inhibiting some creative work, but it's seemingly inconsistent. I've seen this before in other "disciplines" within the hobby, and it gave me similar feelings. Endless, tedious "rules" that seemed almost impossibly hard to comply with.. And I was thinking to myself, "how can that be fun?"

I suppose I was missing the point. And who was I to question someone else's contest. But the whole thing seemed a bit "off" to me. Some hobbyists are weird, I know- but this seemed just a bit too weird. I started looking at this and, despite the huge, huge respect I have for serious biotope aquarium enthusiasts, I think some of these people might be taking things in the opposite direction, and becoming too militant about minutiae to the point where they're giving off the wrong impression about what they deem appropriate. I mean, it's important to provide an accurate representation of the habitat you're into. I get that. You want to populate the tank with the correct wild versions of the exact fish species found in the habitat. No problem there. Yet, many who tread in these waters are under the impression that they need to use the exact biotic materials found in the habitat. I don't think that's what they mean. It's a PR problem. A communication issue, IMHO.

I think my friend might be taking this too far. I think that the idea is to use materials which provide an appropriate and representative assemblage of biotic materials (i.e.; leaves, wood, etc.). I don't think it's to provide the EXACT seed pods, leaves, and soil. I mean, if you can use this stuff, kudos to you. However, I think it's more important to get the fish associations, water conditions, and appropriate habitat representation accurate.

I mean, I could have been wrong, but I was thinking that this is what was intended. Okay, I was HOPING that this is what was intended. Otherwise, the contest entrants will be limited to the 2 or 3 aquarium-keeping locals who reside on a tributary of the lower Atabapo River, or wherever, and who can grab the right leaves, stones, and substrate materials... Know what I mean?

To my relief, this was confirmed when I joined one of those super hardcore biotope groups right here on Facebook. They are as hardcore as any fish group on the planet, and dead serious about doing things right. I mean, your aquarium pics have to be approved before you can post. I'm sure that they would understand what is REALLY meant by some of these contest guidelines. Yeah, these people are seriously vigilant about getting the fish mix right, the correct water chemistry/type (i.e.; clearwater/blackwater, etc.), and proper representation of the biotic factors...meaning, if the area you're representing has a bottom covered in leaves and botanical materials, your tank needs to have a substrate covered in leaves and botanical materials! But that's IT. No explicit "rule" saying that a biotope aquarium has to have every leaf, twig, and speck of sand be a variety of, or hail from materials found in the exact locale. These people get it. It just needs to utilize materials in a way that is representative of the the habitat and locale being represented.

Now, THAT is fun. THAT is challenging. That will help educate and inspire the public while furthering the hobby. That should be an important goal of contests, IMHO.

And THAT is achievable!

So, I love the dedication and enthusiasm, and I think everyone should enjoy the hobby in a manner that pleases them. However, outright dogma in the hobby...sucks. Be disciplined, have guidelines in contests, whatever. Just don't let it cloud your thinking too much. I think the "bigger picture" is as important, if not more so, than the minutiae. Details matter, but so does the mindset.

Don't go too far in the "other direction", okay?

We need you.

Stay bold. Stay earnest. Stay enthusiastic.

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

P.S.- Speaking of contests, some major discussion and announcement FINALLY coming on the 2017 Igapo Challenge!!!!!! ( remember?) Stay tuned!

"Nature's Game": Reconciling what our fishes need against what we want to provide...Some thoughts for discussion...

The following "rant" has a lot of ideas and points. There are some that you might agree with, or violently disagree with! This is good. Remember, it's my opinion, offered up on a topic I"m passionate about, and it's intended to be an "ice breaker" or mind opener to facilitate further discussion. I don't have all of the answers or even a lot of them. I have some thoughts, as I hope you do, too. It should be discussed, debated. Healthy debate is good.

When it comes to blackwater aquariums, a few fishes come to mind immediately for many of us- Cardinal Tetras, Wild Bettas, Rasbora, etc. Yet, every day, we field emails and PM's from "Tinters" who are asking for suggestions on some "cool fish" for their blackwater, botanical-style aquariums. And of course, these are really subjective questions. I mean, it's like asking a teenager who is the top Instagram star, or what the hottest Kanye West song is, or...well, you get it. Opinions are many and varied.

Fishes are a bit different than rappers, Instagram influencers, and fashion, but they all have their fans and detractors. There are many cool fishes that you can keep that not only will challenge you a bit- they'll provide a pleasant diversion from the "cool kids" (like Apistos and flashy Gouramis) that seem to be "it fishes" in blackwater tanks sometimes. Some are obscure.

However there are a few that, although we're well aware of them, we seem to pass over in favor of flashier, larger, and maybe even sexier fishes. And fewer still that everyone sort of "knows about", but not everyone really knows. Our friend the Checkerboard Cichlid, Dicrossus filamentosus, is one of these fishes- one which is perfect for the tannin-stained worlds we love to create. One which we should work with a lot more, for lots of reasons!

Although only known to science since the late 1950's (like, 1958 to be exact), this fish has become a sort of poster child for "Understated, cool cichlid..." and deserves more of our attention! Hailing from the Amazon region (like you didn't expect that, right?) of Columbia, Venezuela, and Brazil ( specifically the Orinoco and the Rio Negro areas), these small fishes are a bit shy, occasionally fussy, and altogether endearing! They inhabit sluggish low-pH/hardness streams and tributaries, where abundant roots, leaves, and other botanical materials provide cover. Obviously, if you're a botanical-style blackwater enthusiast (I have a hunch that you are...), these fishes are perfect for our displays!

An ideal situation would be to set up a modest-sized (40 gallons/160L) or less tank with a small group of them, some abundant hiding places, and lots of leaves on the bottom, and they can develop a hierarchy and social structure on their own. So, you could set up a tank with a lot of wood oriented vertically, to simulate root tangles, and have a thick layer of leaves on the bottom (choose your favorites) for a simple, easy-to maintain hardscape that's a surprisingly faithful representation of their natural habitats.

While not flashy at all, these diminutive cichlids have a certain cool, earthy look which lends itself so well to a botanical-style tank. Their "checkerboard" color pattern and lyre-shaped tails (in the males) stands out against the dark botanicals in a sort of non-flashy way. And the fact that they are a true "specimen fish" even at this late stage in the hobby tells you that there is a lot more work to be done with them! Sure they have been bred numerous times, but they have a reputation for being "challenging", even "touchy." Something about needing soft, acidic water and benefitting from humic substances...Oh, hang a tick...WE offer that as part of our "regularly scheduled environmental programming", right? Yeah.

Which brings me to a quick general digression...or maybe the whole point of this rambling rant:

I think a lot of the so-called "challenging" or "troublesome" fishes in the hobby (specifically ones which come from more specialized habitats like blackwater, etc.) have earned their reputations for sensitivity over the years because the vast majority of the hobby is insistent upon "adapting them" to conditions that are inconsistent with those they have adapted to over eons of evolution. Hobby literature will cite how "adaptable" that fish from soft, acidic water is when it spawns in hard, alkaline city water. And this has emboldened us, compelled us to use this "adaptability" to our advantage to make keeping and breeding said fish easier for us. Yet, when "strange" health issues start occurring over time, or the fishes take on less-than-stellar coloration, vigor and growth, we're quick to search for other answers like food, husbandry, etc.

I think we as a hobby may have created this problem.

Now, don't get me wrong- the aforementioned factors are valid points and good items to investigate under any circumstances where "fish troubles" occur...yet part of me can't help but wonder how much better off many of these so-called "specialty fishes" would be if WE adapted to THEIR needs, rather than vice-versa? Like, us learning how to provide conditions that the fishes evolved under.

The idea of "repatriating" some of these fishes which come from soft, acidic blackwater habitats from our "tap water" conditions back into the water in which they have evolved, and learning how to manage the overall captive environment is by no means new or revolutionary. It's just that we've sort of taken a mindset of "it's easier/quicker for US" to adapt them to the conditions we can most easily offer them. Just because they can "acclimate" to wildly different conditions than they have evolved to live under doesn't mean that they should. I mean, it's not about us. Right? The consistently successful serious breeders have, and we all should, IMHO. As we've shown, it's not at all impossible to provide such conditions as a matter of practice...

And in our own community, we've seen time and time again hobbyists providing "blackwater origin" fishes with the conditions they've evolved to thrive under for eons and seeing them display vigorous growth, intense coloration, and spawning behaviors. Initially, I wanted to say it was all a coincidence. Just timing. But we hear these stories so often now that I think it's more about us doing things right!

Yet, I'm sure many are still skeptical about the idea of "reverse accommodation" being a good one, or even necessary. I can understand, but I think it warrants further discussion.

Need some examples of this concept? Well, look at the reef community, or the planted tank enthusiasts. Once these hobbyists devoted their energies to providing fishes/corals/inverts/plants the conditions that these organisms required to thrive, rather than the conditions that were "easiest" for the hobbyists to provide, these specialty areas exploded, with successes beyond our wildest dreams available to everyone who learns the rules of the game.

And yes, technology and products eventually showed up on the market to enable this process of more easily providing what the organisms need. NOT to adapt them to more easily/conveniently-provided "tap water" conditions, low light, low flow, etc. Rather, it was to make it easier for the largest number of hobbyists to provide the natural conditions which make it possible for these organisms require to thrive. As much as we would have liked to be able to keep thriving reefs full of corals in table-salted tap water, or high-light-loving plants in dim conditions without C02 or nutritive substrates, nature won't let us play that way.

We have to play nature's game.

This concept works.

It's not a coincidence.

Now, a lot of people will argue that having soft water fishes adapt to our hard, alkaline tap water enables tropical fishes to be available to a wide variety of people who might not be interested in keeping them if they had to provide specialized conditions for them to thrive, and that even providing "additives", equipment, or whatever to mimic these conditions is an expense and economic hinderance to thousands. Hard one to argue, I suppose.

As a dog or cat owner, you have to purchase dog food, kitty litter, tick and flea meds, right? An expense. A barrier to entry of sorts? Weak argument? Maybe...

A good part of why I've been so passionate about us as a hobby specialty elevating, researching, and perfecting blackwater aquariums (and next, brackish), is for the very reason argued above. I think once we develop a body of work, experience, best practices, whatever for creating and managing these specialty environments, that the idea of "adapting" fishes to the conditions that are easiest for us to supply may be looked at as a laughable practice someday, much as it is with marine fishes and invertebrates now.

And, as I've cited before- attempting to understand these habitats has also given us a greater appreciation for how precious they are, and how important it is for us to safeguard and protect them and the creatures which have evolved in them. And everyone wins. The fishes. The hobby. Ourselves. The planet.

So, yeah, I think that the Checkerboards which started this rant are just one example of this dichotomy. Like many other fishes, I personally feel that historically, we've "force fit" them into conditions which may simply not be the best for them in the long term. That's a good part of why they're considered "challenging", I'll wager. Now, I know there is an entire Discus "culture"/industry out there which will disagree and cite generations of strong captive bred fishes, developed by people who have forgotten more about fish care than I'll ever know. However, I still can't help but wonder. I mean, despite incredible care and indisputable strain development for decades in captivity, have we really managed to "reprogram" the physiological preferences of a fish that's evolved for hundreds of thousands of generations under significantly different conditions than we provide in captivity? A tough one to argue, but I guess my point again is looking at it from the perspective of "us versus them", in terms of who is accommodating whom!

I think it's also important for us to ask and expect more of our fish suppliers. It's important for us to know where the fish that we're purchasing has come from, particularly if it's a wild specimen. In my opinion, if we are to take the idea of providing our fishes what THEY need, WE need to know this information, research the best that we can, and provide the closest facsimile to their wild conditions possible. It's not always easy. It doesn't always have to be. I mean, could we argue that keeping incredibly rare fishes from precious and endangered habitats is a privilege, and if you can't pay the price of admission (i.e.; providing the correct conditions), maybe you should be playing different game?

Perhaps. I mean, it doesn't have to be militant, exclusionary, or whatever. Yet, I think we need to scrutinize ourselves and our mind set just a bit more closely sometimes.

Something to ponder. Something to debate. Something to work on.

Stay bold. Stay curious. Stay passionate. Stay brutally honest.

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics.

This "neat little niche"

An exceptionally busy Monday, with lots of shipments going out, so today's edition of "The Tint" is, by necessity, a bit shorter...touching on something that was on my mind over the weekend. It's a good way to ease into a new week. We have an in-depth look at something kind of cool for tomorrow!

I recall a podcast I heard not too long ago, in which a well known aquascaper talked about blackwater aquariums being this "neat little niche" in the hobby, and I remember thinking to myself, "You got THAT right!" It IS definitely a niche, with a distinctive, enthusiastic sort of "culture" starting to emerge around it. One of the things we're enjoying seeing here at Tannin Aquatics is the work that our customers are doing on their aquariums with botanicals.

And perhaps the most pleasant surprise is that we're not experiencing a "thing" where every tank starts looking the same.

Yeah, we love this!

Because the blackwater, botanical-style aquarium "thing" lends itself to creativity and interpretation of nature how it really exists, we're not seeing a forced "style", with, for example, "rules" for placement of various botanicals in certain locations or orientations within the aquarium, etc.

Nature itself seems to be the largest source of inspiration for us, not just some "iconic" aquarium someone did. One of the advantages of a relatively new niche!

Each aquarium features an arrangement of botanicals in a way that pleases the individual hobbyist. And what's really fun to me is to watch not only the "evolution" of the aquarium (seeing it darken and the botanicals "soften" a bit)- it seeing the "evolution" of the hobbyist him/herself- the excitement and enthusiasm, the tentative embracing of a new "medium", followed by a sense of growing confidence and a desire to use the botanicals in a manner consistent with some vision he/she has.

I love how the "mindset shift" we touch on constantly has taken a strong hold in our community. It used to be, upon the initial appearance of biofilms or decomposition of botanical items, we're be besieged by hobbyists freaking out, "What have I done? Everyone was right...this stuff doesn't work! I have a tank full of ..goo!". That kind of stuff. And now, it's like, "Sweet- biofilms are appearing and my leaves are softening! My tank is EVOLVING!!!"

Just like in nature, huh?

And the fact that we see aquarists coming from multiple "disciplines" within the aquatic hobby, ranging from hardcore 'scapers to frog lovers, to aquatic plant enthusiasts, to breeders- each bringing elements of their philosophies, needs, and aesthetic to the table, really serves to celebrate the diversity of possibilities using botanicals in blackwater and other aquatic setups.

No dogmatic "requirements" are given. No "application" of specific materials or ideas in a certain way is expected. No admonishment that you're not doing it the way (whoever) would do it...

And there is the... "culture" that has developed...

And YOU- a supportive community- have fostered a sort of "culture" which is supportive, instructive, nurturing- and even awe-inspired by the work of others.

The only "attitude" I think we've ever experienced is the occasional person who stops by for the first time and makes some kind of (well, "ignorant" ) comment about the use of botanicals "not being anything new" (Well..duh-we didn't say that we invented the concept!) or that these tanks are "unstable" (...and you know this because..?). Provocative stuff...And even then, no one jumps on them. (Although I admit I must bite my tonge, os to speak, at times.). Rather, a civilized discussion typically ensues.

Our community really never seems to "attack" other members, which has been, I think, instrumental in the development of this unique niche. Especially in an area of the hobby which has been so obscure, so filled with suppositions, assumptions, lack of solid information, and successful examples to refer to. We don't discourage experimentation and even the concerns of those perhaps having issues with the process of establishing one of these crazy aquariums!

Rather, we offer support where requested, critiques when asked, and share our experiences- good and bad- freely. It's very nice to see. We're all sort of learning, tweaking, and perfecting this stuff together.

Keep doing that.

Stay driven. Stay creative. Stay open. Stay nurturing.

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Chatter about...Cholla!

Ever use Cholla wood in an aquarium?

We've had a lot of interest in this wood, particularly from catfish and shrimp enthusiasts. It's understandable- this is a really useful, lightweight, and attractive wood to use for a variety of purposes. As we've mentioned before, it's super easy to use.

It’s soft enough that fishes like Plecos can rasp at it for supplemental nutrition, and shrimp will graze on the "biofilm" that tend to accumulate on this wood. It does leach a small amount of tannins into the water, and can give it “The Tint” that we love so much here! It’s super easy to attach aquatic ferns and mosses to, as it has lots of cool holes that make securing these plants a snap!

These branches are derived from the dried root of the Cholla cactus in the genus Cylindropuntia, and are native to the Southwestern U.S.

What makes our wood different from the other Cholla you can find out there? Well, first off- we know our source quite well, and they are a family business, and are fully aware of the environmental impact on the areas in which they collect. They are harvested in the Southwestern U.S. on public lands in a sustainable, legal manner by experienced, collectors who hold the permits to do this.

The collectors only take "downed", dead skeletons and pay special attention not to harm or disturb any live plant or animal in the area. This ethos is an important, often overlooked aspect of the acquisition of this unique product. We vetted quite a few suppliers before we became acquainted and comfortable with the quality outfit that we work with.

Cholla is pretty easy to use, and you’ll notice that we offer a pretty consistent “nano sized” version. We offer them as little "branches" and as "chunks" in assorted sizes. Our branches are carefully hand selected for shape and size, brushed cleaned in fresh water, packaged for sale! And, unlike the boring little “logs” you might find elsewhere, many of ours have cool little shapes that offer interesting shaping possibilities. Each one is unique in both size and shape, which makes them even more fun to work with!

Preparation for use is important, and it’s also quite straightforward, actually. It does tend to float a bit when you first immerse it, which is kind of annoying! You have a couple of options to prepare it for aquarium use. First, you could simply soak it in room temperature freshwater for as long as it takes to sink (that could take a week or more, FYI).

It tends to cloud the water when you soak it, so you need to rinse it periodically at first. The nice thing about the "RTS" procedure is that you can rinse it and change the water repeatedly and water your garden with it. Alternatively, you could boil in a large pot for about 45 minute or so, followed by an overnight soak in room temperature freshwater. This is nice because you can get the wood to saturate, while simultaneously forcing some of the organic materials within the wood to release.

Either way, the extra care you put into preparation of this unique wood is well worth it, for it's utility and aesthetic advantages.

Not bad for a dead piece of cactus, huh?

Stay excited. Stay creative. Stay innovative...

And Stay Wet,

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics