- Continue Shopping

- Your Cart is Empty

Pools, ponds, riffles, rain, and current...

Those of you who regularly read this column know that I like to reflect frequently on the "process" of evolving and changing aquariums over time. I view every interaction with our tanks as an opportunity to reflect, observe, and manage the long-term evolution of them. And if you're like me- there are LOTS of interactions with your tanks!

Thursdays are water exchange days for my aquariums. And, rather than look at it as some task on a checklist of stuff to do, some necessary evil" chore- we regard them as... opportunities.

Yup, opportuntiies!

A water exchange represents an opportunity to refresh, reinvigorate, and interact with the aquarium on a much more detailed, intimate level. We've pointed out many times before that, in a blackwater/botanical-style aquarium, the regular water exchanges we conduct on our aquariums are, in many ways, very much a mimicry of what happens in the wild streams and rivers of the tropical world during the rainy season: New water is added to the environment, old botanical materials and leaves are swept away from their current locations, and a new set of materials are deposited in their place.

More so than perhaps other types of aquariums- the practice of replacing botanicals and leaves along with new water is a significant "weekly evolution" of the environment in this style of system.

Beyond a simple "editing ritual" or an aesthetic "refresh", this is a very dynamic process, yet one which also provides longer-term benefits for the ecosystem. Why? Because, as these newer materials are deposited, they not only help "reinforce" the matrix of botanicals already in place, they provide new physical "structure", new foraging areas, new chemical inputs (like tannins and other organics), and provide fresh material for the continued development of food webs.

Yeah, food webs- starting with microbial life and fungi, to algae, and on up to insects and crustaceans, which form the "backbone" of the diet of many of our fishes which hail from these habitats.

In nature, the rain also effects the depth and flow rates of many of the waters in this region, with the associated impacts mentioned above, as well as their influence on stream structures, like submerged logs, sandbars, rocks, etc. Much in the way we might move a few things around now and again during maintenance!

Ever think about it like that? Yeah, it's truly amazing how we can sort of replicate these processes, simply by doing the stuff we do to maintain our aquariums!

And stuff certainly gets moved around, re-distributed, and otherwise affected in the wild as a result of rain!

Like, a LOT!

For example, seasonal water levels can rise up to 20 meters (65 feet) in the middle Amazon region! That's a lot of water! Towards the mouth of the Amazon, the yearly change becomes less and less, but even near the Rio Xingu, it can still be as much as 4 meters (12 feet).

This seasonal deluge has huge impact on not only the physical structure of the associated rivers, streams, and their surrounding forest terrain, but on the fishes and other creatures which reside in them.

At the very least, I think it important to continue looking at our water exchanges and botanical additions/removals in the context of how natural bodies of water actually function.

Return of the Archaens?

Okay, that literally sounds like the title of a Star Trek episode, but it's pretty good for our discussion today, I think!

"Beam me up, Scotty!"

(Okay., I had to...)

Every once in a while, I get an email asking about some of the more esoteric aspects of managing a blackwater, botanical-style aquarium, and it makes me realize that a) there is so much we have to discover as a community, and b) there is even more stuff that I personally am completely clueless about!

And that's okay!

In fact, it's awesome, because it means we are going beyond just tossing seed pods, leaves, and stuff into our tank and admiring the pretty brown water and cool aesthetics...we are thinking about the environment itself, and the interactions and processes which occur in our systems as they operate in this realm.

We're sort of "maturing" in this game.

The other day, a hobbyist contacted me about the process of nitrogen cycle management in the lower pH aquarium; how it works and how we could get a cycle going...And of course, it made me once again kick myself in the ass for sleepwalking through biology class in colleges...but it also got me thinking. Specifically, he was concerned that the "bacteria in a bottle" products that are available commercially for the purpose of kick-starting the nitrogen cycle in our tanks typically don't function at lower pH levels.

It got me thinking about the nitrogen cycle and how it works in our blackwater, botanical-style tanks, and the importance of going slowly, observing and testing, and understanding where the potential pitfalls can be which can (rarely) cause bad outcomes.

I mean, we all should have at least a rudimentary working knowledge about the nitrogen cycle and how it works in our aquariums. There are numerous articles written about that in hobby literature by people who have forgotten more about it than I'll ever know, so I'll assume you have that down..

Back to the "bad outcomes" parts:

It's incredibly rare, however, I think that the occasional bad outcomes we have had over the last few years (I can literally count the reports on the fingers of one hand..) are a result of misunderstanding or miscalculating the effects of identification and such in our lower pH, botanical-style blackwater aquariums.

I think it starts by pushing things too hard and too fast when we are dealing with very low pH aquariums- particularly new and/or biologically "immature" ones. What a lot of aquarists who run very low pH systems report is that the "cycling process" takes longer to complete.

This is an interesting observation, huh?

I know some pretty experienced hobbyists who don't even own an ammonia or nitrite test kit, and have long ago felt that the "need" to measure ammonia or nitrite has been eclipsed by their experience, so they have no way of correlating this to the (admittedly rare) "disasters" which befall their low-pH systems...tsk, tsk.

And the longer "cycle time?"

This definitely correlates with my personal findings, although I've personally never managed a system with a pH much below 5.5 pH; this is where the "outer limits" of low pH aquariums starts for most, and this is likely the realm of Archaea, as the Nitrosomanas and Nitrobacter barely function at that point. We've seen advanced aquarists depend upon chemical filtration media to manage organics at these extremes.

And once again, I think that the real key ingredient to managing a low pH system (like any system) is our old friend, patience! It takes longer to hit an equilibrium and/or safe, reliable operating zone. Populations of the organisms we depend upon to cycle waste will take more time to multiply and reach levels sufficient to handle the bioload in a low-pH, closed system containing lots of fishes and botanicals and such.

This certainly gives the bacterial populations more time to adjust to the increase in bioload, and for the dissolved oxygen levels to stabilize in response to the addition of the materials added-especially in an existing aquarium. Going slowly when adding are botanicals to ANY aquarium is always the right move, IMHO.

And at those extremely low pH levels?

Archaens. They sound kind of exotic and even creepy, huh?

Well, they could be our friends. We might not even be aware of their presence in our systems...If they are there at all.

Are they making an appearance in our low pH tanks? I'm not 100% certain...but I think they might be. Okay, I hope that they might be.

Refresher:

Archaeans include inhabitants of some of the most extreme environments on the planet. Some live near vents in the deep ocean at temperatures well over 100 degrees Centigrade! true "extremophiles!" Others reside in hot springs, or in extremely alkaline or acid waters. They have even been found thriving inside the digestive tracts of cows, termites, and marine life where they produce methane (no comment here) They live in the anoxic muds of marshes (ohhh!!), and even thrive in petroleum deposits deep underground.

(Image used under CC 4.0)

Yeah, these are pretty crazy-adaptable organisms. The old sayings that "If these were six feet tall, they'd be ruling the world..." sort of comes to mind, huh?

Yeah, they're beasts....literally.

Could it be that some of the challenges in cycling what we define as lower ph aquariums are a by-product of that sort of "no man's land" where the pH is too low to support a large enough population of functioning Nitrosomanas and Nitrobacter, but not low enough for significant populations of Archaea to make their appearance?

I'm totally speculating here. I could be so off-base that it's not even funny, and some first year biology major (who happens to be a fish geek) could be reading this and just laughing...

I still can't help but wonder- is this a possible explanation for some of the difficulties hobbyists have encountered in the lower pH arena over the years? Part of the reason why the mystique of low pH systems being difficult to manage has been so strong?

Could it be that we just need to go a LOT slower when stocking low pH systems?

Perhaps. Yeah, probably.

And then- you think about the pH levels in some natural, well-populated (by fishes!) blackwater habitats falling into the 2.8-3.5 range, you have to wonder what it is that makes life so adaptable to this environment. You have to wonder if this same process can- and indeed does -take place in our aquariums. And you have to wonder if we simply aren't working with these tanks in a correct manner.

Particularly, when they fall into what we'd call "extreme" pH ranges. I wonder if the "crashes" and fears and all sorts of bad stuff we've talked about in the hobby for decades were simply the result of not quite understanding the "operating system?"

Things just work differently at those lower pH levels- in nature, and in our aquariums.

I think the secret is out there somewhere.

And I can't help but speculate if the key to success with these low pH systems lies in understanding the functions of...

The Archaens.

Stay curious. Stay bold. Stay resourceful. Stay engaged...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

The blackwater/botanical-style aquarium...a freshwater "reef" system? Sort of?

As someone who has kept many different types of aquariums over they years, I find myself making comparisons between systems, techniques, and function of various types of approaches. One of the most interesting analogies that I find myself making (at least in my head...) is the similarities between reef aquariums and these "BWBS" systems.

Now, on the surface, I can understand the assertions by many who think these tanks couldn't be more divergent from each other, beyond the obvious fresh/salt comparison.

However, I think when you look at them from both a functional and operational standpoint, it becomes remarkably clear that these two types of tanks have interesting similarities.

Now, this begs the question: "Why should we care, Scott?"

Well, I'm asking it for you! Here's the reason: Because the reef aquarium is probably one of the ultimate examples of a captive system that requires us- the hobbyists- to maintain the environment in a manner which supports "layers" of life forms, from bacteria to infaunal organisms, to fishes. And in doing so, we are supporting a "chain of life forms" with interdependencies and relationships. The techniques which we incorporate to accomplish this are transferable to both disciplines.

More than just for the purpose of providing "aquatic cross-training", this similarity is important because we are starting to see the blackwater, botanical-style aquarium as a microcosm.

Planted aquarium enthusiasts get this, to a certain extent...especially those who play with "dirted" substrates and such.

However, as botanical-style, blackwater aquarist fans, we're in a very unique position to really embrace and expand on this concept.

We as serious freshwater hobbyists need to look carefully at some of the ideas our reef keeping brothers and sisters are playing with, and embracing some of the ideas reefers incorporate into their systems about "holistic" microcosms.

In our case, wood, leaves, water...and the life forms that reside in them all work together to create a functional, aesthetically unique microcosm...one in which our fishes may display extremely natural behaviors. One in which we might be able to unlock some secrets of their life functions, and gain a greater understanding of their precious and fascinating natural habitats.

Win-win.

A simple idea for a Sunday.

Stay intrigued. Stay enthusiastic. Stay open-minded.

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Revisiting the art and science of botanical preparation.

Over the years, we've developed a lot of "technique" for doing "stuff" with our blackwater/botanical-style aquariums. One of the most fundamental tasks associated with our tanks is the preparation of botanicals for aquarium use. It's as much an "art" as it is a "science"- in fact, it's not really a "science."

The idea is to get your dried botanical materials into a condition where they are both reasonably clean, and with their tissues saturated sufficiently to cause them to sink. This usually involves some simple, yet possibly time-consuming tasks, as we've all come to know.

There are basically three ways to prepare most botanicals for use in the aquarium:

1) Boil them/steep them in boiling water

2) An overnight (or longer) soak in room temperature water

3) A combination of both.

Always rinse any of our aquatic botanicals in clean fresh water before use, even after boiling or soaking. This will rinse away any loose dirt or organic material that has adhered to their surface tissues. Just sort of a "best practice", IMHO.

THE ART OF THE BOIL

For the vast majority of botanicals, you'll need to boil them in a clean pot for at least 30-40 minutes; many stubborn ones (ie' really buoyant botanicals) may take more than an hour of continuous boiling!

The boiling process not only saturates the tissues of many botanicals, it breaks them down a bit, and helps release any surface dirt that might be remaining (like dust, pollen, spider webs, etc.). The boiling serves the dual purpose of helping release pollutants and getting them to absorb water to sink. (No one likes a floating pod)

Materials like leaves don't necessarily need to be boiled; you might elect to simply "steep" them in boiling water for a period of time (like 20 minutes or more) to help soften them and get them to sink. This process works fine for leaves like Catappa, Loquat, and Guava- a bit less so for the more "durable leaves, like Magnolia, Mangrove, and Jackfruit.

During the boiling/steeping process, many of you have remarked how wonderful the resulting "tea" smells, and we can't argue with that! It sort of creates a total sensory experience! A lot of you ask if you can use the water that the botanicals were boiled in as a sort of homemade "blackwater tonic." Now, on the surface, it seems like a pretty good idea. I mean, you're adding this botanical stuff into your aquarium, so what's the harm in adding the water they were boiled in as well? There's all those beautiful tannins they released...

...and the surface dirt, bound-up organics, sugars, dust, etc. as well- sort of concentrated. Would you really want to add THAT stuff into your tank? I know I wouldn't. The closest analogy I can think of is the idea of adding nasty stuff that your protein skimmer removes from the water in your reef tank back into the tank. Once you see and smell that crap, you wouldn't even consider it!

Now, our little "tea" isn't nearly as nasty as protein skimmer effluent, but it is still la sort of concentrated "cocktail" of stuff that I'm hesitant to add to the cozy confines of my aquarium. It waters my garden.

That being said, plenty of you DO add this stuff without incident.

The oft-cited reason being that you, "don't want to waste all of those wonderful tannins!" Trust me, there are more when're that came from- don't worry. Even well-aged and prepared botanicals will, in my experience, continue to leach water-tinting tannins for extended periods of time.

However, it's your call here, of course...

Following the boil, you can give the botanicals a quick rinse, and either add them to your aquarium, or (and I like this idea better), place them in some clean, room temperature water overnight, or longer. If you want, you could even throw in some chemical filtration media (activated carbon, Purigen, etc.) passively to adsorb any remaining pollutants which might be released following the boil. And of course, soaking the botanicals also serves to fully saturate them and make sure that they stay down!

THE SOAK

Can you avoid the boiling process altogether?

Sure, it's possible...conditionally.

With some botanicals, such as leaves, it might take a few days, but soaking them in room temperature freshwater can help saturate their tissues and get them to stay down, while releasing some of the aforementioned pollutants bound up in their surface tissues.

With the more "durable" botanicals, like "Jungle Pods", "Savu Pods", "Ceu Fruta", etc.- it's pretty challenging, because they have that hard exterior which makes saturation of the tissues to the point where they'll sink very difficult and time-consuming. Boiling is a better choice, because it breaks down some of the surface tissues, better preparing them to absorb water.

And of course, you can just place them in the tank and let them soak there and performing a water exchange before continuing with the "startup process." "In situ" preparation works fine, in my experience when you executed it in this manner.

THE "BAD" STUFF?

Really?

Sure.

Like anything we do in the aquarium world, botanicals have good and bad stuff associated with their preparation and use.

An annoying thing about botanicals is that there are many that simply won't sink, even after an hour or more of boiling. You can continue to leave them "steeping" in water for as long as it takes to "get 'em down", or you could put them in a mesh filter bag and keep them in your canister or outside power filter to continuously pass water over them. I even played around with a coffee "French Press" technique that worked..All of these tricks can help!

And of course, there are always caveats...

The simple truth about using botanicals is that you're adding natural terrestrial materials that, when acted upon by bacteria, break down in your aquarium, increasing the bioload of the system. We've said it thousands of times over the past few years, and we'll say it again here- you need to add botanical materials to your aquarium slowly, over a period of days or weeks. You have to be careful. You have to observe, test, and adjust.

Think about it: It's not really a revelation. Adding large quantities of ANYTHING in a short period of time into your established aquarium could cause some issues. And it starts with our friends, the bacteria, and the biofilms which they create.

Biofilms form when bacteria adhere to surfaces in some form of watery environment and begin to excrete a slimy, gluelike substance, consisting of sugars and other substances, that can stick to all kinds of materials, such as- well- in our case, botanicals.

Biofilms are THE foundation of life in most streams and rivers. Other major components of biofilms are bacteria, fungi, archaea, and protozoa. They are an important part of the aquatic environment- even a food source for many organisms.

However, in an extremely overcrowded aquarium (or a very small one) with marginal husbandry and filtration, with a huge amount of biofilm (relative to tank volume) caused by an equally huge influx of freshly-added botanicals, there is always the possibility excessive respiration by biofilm bacteria could lower the water’s dissolved oxygen and increase CO2, asphyxiating your animals and the important aerobic nitrifying bacteria.

YIKES! That's sort of a doom and gloom scenario, huh?

Well, yeah- it can be if you're not careful.

Which is why we've continuously emphasize going slow and steady when adding botanicals to your aquarium. However, use of botanicals need not be scary, problematic- or even mystifying. You just need to deploy observation, patience, and a healthy dose of common sense.

No more exotic or complicated than the effort extended to maintain any sort of aquarium, really.

It's a growing worldwide practice, a genuine "movement" within the aquarium hobby, with hobbyists creating amazing, stable, functional aquariums with these unique materials.

So the real "secrets" of the botanical preparation process? Prepare carefully. Add slowly. Observe, test, and tweak as necessary.

Simple, if you make it that way.

Keep it simple. Be responsible and vigilant. And...enjoy the process.

Stay excited. Stay involved. Stay intrigued...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Sifting through science...

A lot of you who are into this blackwater/botanical-style aquarium stuff are sort of like me- looking for some more detailed information than what is commonly available in the hobby literature.

As it turns out, there is some pretty good information out there on this stuff, but you have to ferret it out from scientific papers and other information. In our super-fast, "I need instant concise info now!" age, it's not so easy to find stuff that can spur greater understanding of our beloved topic by simply looking through hobby literature.

It's just not there.

Yet.

With so many of you now experimenting with blackwater aquariums, the "working knowledge" of our craft is evolving rapidly. Practical applications for botanicals are being discovered, improved upon, and shared daily throughout the world!

Now, I could write blogs simply regurgitating the same watered-down topic materials that's been shared in hobby circles for decades, or I can deep-dive into areas (often well over MY head!) which might provide further insights into just how and why these habitats occur in nature, and what the implications are for aquarists, in the hope that we can glean more from this stuff.

I choose to get in over my head!

Nice.

That being said, I can present the stuff I've found to be of relevance to our work (at the risk of "watering it down" myself), but, as I repeat ad nauseam, I am not a scientist, so we're going to collectively have to absorb and interpret the bits and pieces we find to see how they can relate to our aquarium obsession.

Now, I'm lucky, because I have a friend who is really into all things science; he literally collects scientific papers and literature on all manner of "stuff", and upon learning of my obsession with blackwater ecology and the desire to find out more, and, over the years, has provided me with enough related, relevant scientific papers on these topics to keep me busy until the sun goes supernova!

So there IS a lot out there on the topic of humic substances and tannin in water, and on the composition of blackwater habitats. It's actually very well studied by science; it simply hasn't "trickled down" to the hobby level to any practical extent (until, oh...maybe...NOW!). And much of it involves understanding the physical environment in which blackwater systems are found in nature.

For example, one of the most important influences on blackwater rivers is the soil and sedimentation of the surrounding areas. It starts with the soils. Blackwater rivers, like the Rio Negro, for example, originate in areas which are characterized by the presence of white sands known as "podzols." (note that, biotope-oriented aquascapers!)

Podzols are soils with whitish-grey color, bleached by organic acids. They typically occur in humid areas like the Rio Negro and in the northern upper Amazon Basin. And the Rio Negro and other blackwater rivers, which drain the pre-Cambrian "Guiana and Brazilian shields" of geology, can in part attribute the dark color of their waters to high concentrations of dissolved humic and fulvic acids! Although they are the most infertile soils in Amazonia, much of the nutrients are extracted from the abundant plant growth that takes place in the very top soil layers, as virtually no plant roots are observed in the mineral soil itself.

One study concluded that the Rio Negro is a blackwater river in large part because the very low nutrient concentrations of the soils that drain into it have arisen as a result of "several cycles of weathering, erosion, and sedimentation." In other words, there's not a whole lot of minerals and nutrients left in the soils to dissolve into the water to any meaningful extent!

Perhaps...another reason (besides the previously cited limitation of light penetration) why aquatic plants are rather scare in these waters? It would appear that the bulk of the nutrients found in these blackwaters are likely dissolved into the aquatic environment by decomposing botanical materials, such as leaves, branches, etc.

Why does that sound familiar?

Besides the color, of course, one of the defining characteristics of blackwater rivers is pH values in the range of 4-5, and low electrical conductivity. Dissolved minerals, such as Ca, Mg, K, and Na are negligible. And with these low amounts of dissolved minerals come unique challenges for the animals who reside in these systems.

How do fishes survive and thrive in these rather extreme habitats?

It's long been known that fishes are well adapted to their natural habitats, particularly the more extreme ones. And this was borne out in a recent study of the Cardinal Tetra. Lab results suggest that humic substances protect cardinal tetras in the soft, acidic water in which they resides by preventing excessive sodium loss and stimulating calcium uptake to ensure proper homeostasis.

This is pretty extraordinary, as the humic substances found i the water actually enable the fishes to survive in this highly acidic water which is devoid of much mineral content typically needed for fishes to survive!

Oh, and this juicy finding in a study on humic substances in ornamental fish aquaculture: "Humic substances are not real alternatives to strong traditional therapeutics. However, they show different advantages in repairing secondary, stress induced damages in fish."

Something in those leaves and botanicals, right?

And this goes far beyond just the cool aesthetics they impart, too!

Yeah, there is a lot of cool stuff out there. It's just not the easiest thing to dig through. But there is a lot of information out there if we're up for the challenge.

And we should be up for the challenge!

I'm reminded of a passage from a speech by the late Neil Armstrong, the first astronaut- the first human- to walk on the moon:

"There are great ideas undiscovered, breakthroughs available to those who can remove one of the truth’s protective layers. There are places to go beyond belief..."

Keep peeling back those protective layers. Keep looking under the stones. Keep digging.

Stay bold. Stay curious. Stay imaginative. Stay earnest. Stay enthusiastic...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Color, contrast, and function: Replicating the flooded forests of South America

We're at a cool phase in our journey into the blackwater/botanical-style aquarium world. We're beyond just creating generic, "proof of concept" aquariums- we're now actively constructing systems which replicate- at least in part, specific natural habitats which encompass an influx of natural terrestrial materials.

It's interesting to study some of the niche environments that exist in nature, which are heavy influenced by terrestrial life. A prime example of this are the South American forests and swamp forests, which are seasonally inundated with freshwater. These forests are perhaps nature's finest example of the interaction between land and water, and how diverse and surprisiingly productive aquatic environments arise in these habitats. The two types of inundated forest areas are blackwater systems known as igapó, and the counterpart "whitewater" systems called várzea.

The igapó is characterized by seasonal inundation caused by a large amount of rainfall, and thus, in some areas, trees can be submerged for up to 6 months of the year. We've touched on the idea of replicating this habitat in "The Tint" some time ago. These forests have sandy, rather acidic soils with a very low nutrient content. The rainwater combines with the humic substances and tannins contained in the soils and the forest floor materials that are found on them. The acidity from the water corresponds to the acidic soils of these forests. They are the more nutrient poor than a comparable várzea forest, carrying less inorganic elements, yet higher concentrations of dissolved organics, like humic and fulvic acids.

Amazonian várzea forests are flooded by nutrient rich sediments, and thus are very productive environments- some of the most productive in Amazonia. They are flooded by whitewater rivers, which inundate fertile alluvial soils within várzea forests, which helps explain some of the higher nutrient concentrations found in these waters, as opposed to the nutrient-poor blackwater which inundates and characterizes the igapó areas.

Some of the most popular aquarium species, such as Tetras, Apistogramma, and Loricariid catfishes, reside in these systems during the periods of inundation, and studies have revealed a surprisingly high population density within them.

In a comparative study of Amazonian fish diversity and density conducted by Henderson and Crampton in 1994, in nutrient poor blackwater igapó and richer whitewater várzea habitats in Brazil, the whitewater sampling sites were characterized by high turbidity and conductivity, and a pH of 6.6-6.9. By comparison, the blackwater sites had low turbidity, a very low conductivity, and a pH of 5.3-6.0.

Both whitewater and blackwater sites held high diversity fish communities with many species in common. Whitewater habitats were more diverse, yielding 108 species, compared with 68 from blackwater. However, each habitat has some characteristics which shape the population composition and density, and it bears noting when thinking about stocking our aquariums, doesn't it?

I think it does!

Várzea have a characteristic which makes them very hospitable to fishes: During the flooding season, the more static várzea whitewaters, which develop low oxygen levels, lack predatory species such as Eels and Knifefishes, which are more typically abundant blackwater. There is a lower overall density of other predators, which have migrated or are confined to smaller, dryer areas, and the resident fishes use this time to spawn! The productivity of the varzea generates large amounts of detritus, particularly when the water level falls, which supports the fishes that feed on this material.

On the contrary, detritivorous fishes are less abundant in the igapó, where far less of this material is found. Fishes in these areas tend to consume greater quantities of insects, wood/leaves (as in the case of some catfishes), and of course, each other!

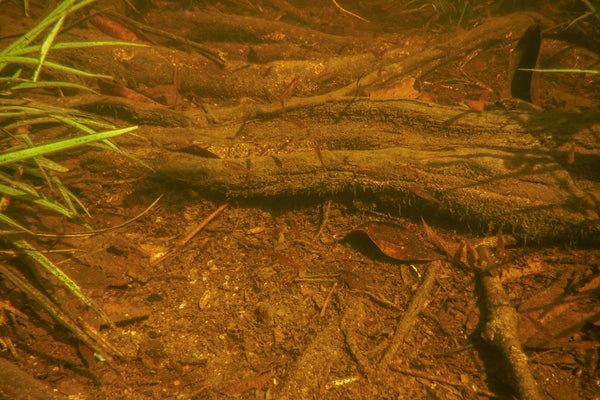

Another interesting thing about Amazonian streams and flooded forest areas in general is that there is no significant "in situ" (in place) primary production, and that the fish populations that reside in them depend on what is known as "allochthonous input" (material that is imported into an ecosystem from outside of it) from materials like seed pods, fruits, blossoms, leaves, and dead wood from the surrounding forest.

This is why leaf litter beds are so important in blackwater, as they serve as sort of "aggregators" of terrestrial material, and foster decay and biological processes which support what aquatic ecologists call "food webs." Most of the aquatic life forms which reside in these waters are aggregated in submerged litter.

You would simply run chemical filtration, such as activated carbon, Poly Filter, Purigen, etc., etc. in your filter to negate the tint, something we have discussed and experimented with on our own systems a couple of years back, as a sort of demonstration that you can do this.

For those of us who love blackwater, just omit the chemical filtration media and you're golden- literally...

For a várzea-themed aquarium, we'd say to omit some of the more heavily "tint-producing" botanicals, and go with stuff like the more "durable" seed pods, like "Lampada Pods", "Savu Pods", "Concha Pods", "Flor Rio Pods", etc. These not only impart less tannins into the water than leaves and such, many of them, such as "Flor Rio" and "Concha" represent the fruits and such that accumulate in these waters.As mentioned above, a good chemical filtration media should counteract any tint imparted into the water by these materials, as well as the nutrients released by them.

For the igapó-themed tank, it's "game on," and you can use just about any botanical items you'd want, particularly, leaves. Since blackwater is your thing, you need not concern yourself about "tint limitation" in your botanical choices. I'd lean towards items like Coco Curls, "Rio Fruta", Catappa and Magnolia leaves as some of your primary "botanical stars" in such a setup.

One thing that I haven't really put much thought into when developing either concept in the past, yet am interested in now, has been the application of proper substrate materials in these aquariums. I'm considering the use of acidic soils in the igapó tank, versus more "alluvial" materials in the várzea aquarium. This is where some of the more specialized aquatic soils that are used in planted aquaria, for example, may come in handy. Some of you intrepid hobbyist with knowledge of planted aquarium substrates need to do some research on this stuff! Interesting, and perhaps just a bit ironic, that our work as natural botanical-style, "hardscape-first" aquarium hobbyists could be aided by aquatic soils created for planted tanks....

Aquascaping in general for these aquariums is fun.

Since you are simulating a flooded forest, the idea of using large, vertically-oriented pieces of wood to simulate submerged trees and shrubs is immediately appealing. Projecting wood out of the water would be perfectly acceptable in such a tank. I'm stealing a pic from our friend Adam Till, who, in addition to being a serious researcher of botanical substrates, just happened to have created an aquarium that demonstrates an interesting "above and below", sort of palludarium-like display a while back, that would really work for this situation!

As you can see, there is so much more to the "concept-aquarium" world besides underwater mountain ranges, beach scenes, and "Middle Earth Fantasy 'Scapes." And you don't necessarily have to go full-on, 100% hardcore "biotope", either. Rather, you can "riff" off of these unique and important habitats and create truly amazing aquariums.

For those aquarists who are not only interested in the aesthetics of these unique habitats, but the execution of incredible functional systems as well, there is so much work to be done.

So many potential discoveries and breakthroughs to be made. Certainly worth devoting some talent, energy, enthusiasm, and tank space to!

Until next time- Stay engaged. Stay creative. Stay curious. Stay original.

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Patience. Impulsiveness. The "long game." And everything in between.

Are you one of those people who loves to have stuff right now? The kind of person who just wants your aquarium "finished"- or do you relish in the journey of establishing and evolving your little microcosm?

I'm not sure exactly what it is, but when it comes to the aquarium hobby...I find myself playing what is called in many endeavors (like business, sports, etc.) a "long game."

I'm not looking for instant gratification. I know that good stuff often takes time to happen. I'm certainly not afraid to wait for results. Well, not just sit around in the literal sense, mind you. However, I'm not expecting instant results from stuff. Rather, I am okay with doing the necessary groundwork, nurturing the project along, and seeing the results happen over time.

A "long game."

If you're into tropical fish keeping, it's almost a necessity to have this sort of patience, isn't it? I mean, sure, some of us are anxious to get that aquascape done, get the fishes in there, fire up the plumbing in the fish room, etc. However, we all seem to understand that to get good results- try satisfying, legitimate results- things just take time. Yeah, I'd love it if some "annual" killifish eggs hatched in one month instead of 7-9 months.

I wouldn't complain, but I do understand that there is the world the way it is; and the world the way we'd like it to be!

I've learned in the many years that I've been playing with blackwater tanks that the tank just doesn't get where you want it overnight. Initially, you'll see that burst of tint in the water, a tone, and see some of the materials you place in the tank breaking down, but for a while, your carefully conceived aquascape just looks like some wood with some leaves and seed pods thrown on the bottom, doesn't it? Perhaps almost "clinical" in appearance; not quite "there" just yet, huh?

We can scape well. We can manage the tank effectively; engage in best practices to keep it functioning and progressing in a healthy manner...But we cannot rush nature, right?

It simply takes time. Time for the bacterial and fungal populations to grow and soften the botanicals in your aquarium. Time for the water chemistry to stabilize. Time for the aquascape to take on a more "mature", established look.

It's not really 100% in our control.

Which is kind of cool, actually. There is that certain "randomness" about a blackwater, botanical-style aquarium- or ANY aquarium, for that matter- which makes the whole process just that more engrossing, if you ask me.

We just supply the patience.

Some of us are impatient, however..which begs the question:

Are you an “impatient fish geek?”

Be honest.

I ask that not to get some secret marketing data I can use to exploit your psychological weaknesses for my own nefarious purposes (hmm..but that does sound like an interesting idea..). Rather, I’m curious because, as I asserted above, I think that most hobbyists are not.

Usually. Okay, maybe- sometimes…

As aquarists, we’re taught that nothing good ever happens quickly in a fish tank, and I’d tend to agree with that. Most of us don't make really rash decisions, and go crazily into some tangent at the first sign of an anomaly (as we discussed yesterday..)

However, as consumers, I think us fish geeks do sometimes make things happen quickly with last-minute purchasing decisions! We tend to deviate just a bit from our normal patient attitude and "long game", and often go "off plan."

We get a bit...impulsive!

When I co-owned Unique Corals, I dealt with lots of hobbyists every day who were buying corals and fishes, and I was often surprised at the rather odd additional purchases that people make to “fill out” their orders- you know, to hit free shipping, get an extra piece of coral to share with a friend, or just to “scratch that itch” to try a new species…It happened just often enough to make me think that fish geeks are not necessarily impulsive, but that we are "strategic."

In other words, the purchase may not be something we would start our order with, but it "justifies" purchasing at the end in order to hit that free shipping number, etc.

Logical, on the surface, right?

Yeah.

However, being a lifelong fish geek and student of the "culture" of aquarium keeping, I think many of the reefers I dealt with really wanted that extra piece in the first place. A lot of times, they’d mention, in passing, at the end of an order or other conversation, “So, are those Montipora really that hard to keep in good color?” I got a sneaking feeling that they intended buy the coral anyways, and maybe just needed some "assurance" that it was a cool piece, or within their skill set to maintain, or something like that. The "impulse buy" was almost always something totally unrelated to their primary order (for example, 5 zoanthids, and then an Acropora added at the last second)!

So very like us fish geeks, isn’t it?

You see this at fish club raffles all the time- when the hobbyist who's bred like 300 species of fishes and swears that she's done trying new ones- ends up feverishly bidding for some obscure cichlid or characin in the heat of the moment- always done under the pretext of "helping the club out"-seemingly casting aside her "mandate" NOT to get any more fish!

And then, of course, there are those of us like me, who are the polar opposite of this:

I recall driving my LFS employees crazy when I was younger, because I’d spend literally hours in the store, scrutinizing every aspect of a fish before I’d pull the trigger…or not (that must be why I drove ‘em crazy!). I would look at every fin ray, every gill movement…I’d look at every "twitch" and "scratch" the fish performed and correlate it with known disease symptoms versus regular behaviors for the said species…

I would sometimes even bring my reference material (like Axelreod’s or Baensch's books and maybe the early Albert Thiel stuff after the dawn of the “reef” age, notes from Bob Fenner’s books in my hand later on), and would just geek out.

Yeah. Weird.

Of course, I would second guess everything the LFS guy said because “the books” said otherwise, even though the employees worked with these animals every day of their lives. My first brush with aquarium-keeping “dogma”, I suppose.

I was a complete dork!

My, how things change! (well, the "dogma" part...I'm still a dork, I think...)

I knew at an early age that I’d never be an “impulsive fish geek."

I learned patience right away.

I think that in my case, it might have come about because, when you’re a kid, you have a 10 gallon tank and $5.67 in change that you’ve painstakingly saved for months to spend. You need to be absolutely sure of your purchases.

I was very thorough!

Even as an adult, with a 225-gallon tank, and much more money to spend, I still found myself doing the same thing (okay, maybe with my iPhone in tow, instead of some well-worn reference book).

It could take me like a year to stock a 50 gallon tank fully...

You should see me when I go to the wholesalers here in L.A….it could take me half a day to pick like 5 fish. At Unique Corals, we worked with a lot of collectors and mariculturists overseas..However, we had built up personal relationships to the point where these guys more or less knew our tastes, and would often throw the fishes in the boxes with corals, so that was actually easier than going to the wholesaler’s facility! (well, better than sending ME there, anyways!)

This "anti-impulsive" thing isn't just limited to fishes, in my case...

Equipment choices are even more subject to analysis and absurd scrutiny, because hey- how often do you purchase a heater or a lighting system? ( OK, wait- don’t answer that). But seriously, when you’re sending the big bucks on a critical piece of life-support equipment, you want to get it right! One of the things I love most about the internet is that most sites will analyze the shit out of almost anything, from an algae magnet to a new aquarium controller. Useful stuff for many of us- essential for anal-retentive fish geeks like myself.

Of course, impulsiveness can permeate every aspect of being a fish geek, including setup and configuration of your tank. I may not be overly impulsive in terms of additions and purchases, but I CAN be "spur-of-the-moment" on tank decisions.

What exactly do I mean by “tank decisions?”

For example, I’ll be scraping algae or some other mundane maintenance chore in my tank and suddenly, I’ll notice a rock or driftwood branch that seems “not right” somehow…”Hmm, what if I move this guy over here…?” Of course, this almost always leads to a spontaneous “refreshing” of the aquascape, often taking hours to complete. Somehow, I find this relaxing. Weird. So it’s entirely possible to be analytical and calculating on some aspects of aquarium keeping, and spontaneous on others.

I believe that this dichotomy actually applies to many of us.

And of course, there are aquarists who are entirely impulsive, which is why you see entire 200-gallon tanks full of every fish imaginable, with selections from all over the world poking out from every nook and cranny. (Or, as one of my hardcore "freshwater-only" friends asserted, "That's why there are reef tanks..." Ouch! ) Of course, I cannot, in all honesty, say anything truly negative about impulsive hobbyists because some of these types keep many of us in business, lol!

The "long game" is familiar to many of us...and of course, so is the love of the "impulse buy" or "quick-reconfigure." And of course, I couldn't resist analyzing the hell out of a seemingly arcane topic like this. After all, I am your "morning coffee" or "afternoon tea", as I've been told- right?

So, stay impulsive, while staying patient simultaneously...Stay crazy, motivated, fun-loving, adventurous, and just a bit weird.

Stay curious. Stay patient. Stay diligent...

And of course,

Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Reading between the lines...but not too much.

Have you ever noticed how easy it is to over-analyze and overreact to stuff?

To read too far between the lines?

Case in point: I have a friend who has the opinion that every time you sneeze, cough, or have a headache, or display any overt "symptom" which could somehow be tied to a cold, flu, or other malady- that you've acquired said illness, and that you're headed for a week of bed rest, chicken soup, and Netflix.

Super paranoid. Drives me crazy.

Yet, I see this mindset in other areas of our lives....

Like...our aquarium hobby!

I sometimes wonder if we as hobbyists tend to become just a little more paranoid than we need to be?

Like, have you noticed that, when you're looking at your aquarium, any sound, any behavioral change in your fishes, any minor appearance difference- can send you into a veritable frenzy of cross-checking, water testing, examination, etc?

Oh, you may not admit to it; you might think that you're immune to the concerns, etc.

But you're not.

Let's face it, we are all sort of paranoid- and I mean that in the nicest way possible. We're damn concerned about the well-being of our fishes, the safe operation of our aquariums, and the overall health of the system. That's a good thing, unless we take it too far.

And some hobbyists do.

For some of us, any little apparent "anomaly" which deviates even slightly from what we know and are familiar with makes us at the very least, cautious and alert...Perhaps, uncomfortable, and at the worst- panicked.I know a lot of hobbyists like this. It's like a full-scale "disaster" when something different appears to be going on with their tanks. On more than one occasion, I've been at an out-of-town hobby conference when a friend cut short his/her weekend and flew home the same day because their spouse told them that. "The big coral colony...wasn't open this morning like it usually is."

That's too far, IMHO. That's not "dedication..." It's sort of- well...I think it's sort of crazy, really.

Don't panic. Don't be uncomfortable.

I mean, I get it. You have a lot of money and effort tied up in your tank. You care about your fishes. And it's always a good idea to check out anything that seems out of the ordinary with your tank...but to launch on a wholesale, dose-the-prophylactic medication-to-every-tank frenzy is just an extreme that you really don't want to do...such actions often lead to a real problem- far worse than whatever perceived one existed (if it did at all).

Just be...concerned.

Check it out.

See what's really going on. Keep a level head while doing this. Correct only if needed, and get on with your day. Maybe you'll catch a real problem. More likely, you'll have just suddenly realized that the weird humming sound coming from your canister filter is simply the normal sound it makes during operation, or the one that tells you that it's time for a cleaning.

Nothing signaling a pending disaster for your tank...

Yep.

Don't make this hobby more difficult than it is by "connecting the dots" and inventing problems that aren't there. Look, it's great to be aware, alert, vigilant about your aquariums. It's important to know exactly what "normal" is for them. It's important to intervene at the first signs of disease. It's important to check out that little trickle of water...

But you need to relax, for the most part. Maintain an "even keel."

Because, just like every sneeze doesn't mean you're sick, every new sound that you hear in your aquarium-every different behavior in your fishes- every different turn your Cryptocoryne takes- doesn't necessarily mean that disaster is lurking around the corner...

An ultra simple, yet hopefully useful thought fir this Sunday...

Now, if you'll excuse me- I have to go check out why my tank is making that strange "gurgling" sound... Maybe it's... Ahh, never mind.

Stay alert. Stay Active. Stay positive. Stay calm.

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Form and function in the botanical-style brackish water aquarium

With the uptick in interest in "Estuary by Tannin Aquatics", we've begun to see some interesting experiments, have had some great discussions, and of course, receive a fair number of questions about the whole idea of botanical-style, brackish water aquariums. And curiously, one of the top questions we receive is how we arrived at the name "Estuary" for our line.

Well, let me explain!

An estuary is the areas of water and shoreline where a freshwater stream or river merges with the ocean. Estuaries can be partially enclosed bodies of water (such as bays and lagoons) where two different bodies of water meet and mix. Hence the whole "brackish" thing. Salinity varies in these habitats, often depending upon tidal influences. And these regions are very ecologically "productive," because of the nutrients brought in by rivers. Many of the fishes and invertebrates that inhabit these brackish water communities migrated from the ocean or freshwater habitats.

Although aquarists have been playing with brackish tanks for decades, in my opinion, what's been missing is a focus on the actual habitat and how it functions. Just like what the hobby was doing in the blackwater area for years, I think we've been collectively focusing on the wrong part of the equation for a long time- in this instance, just "salt" and basic aesthetics.

As we've done with Tannin, we're focusing a lot of energy on the functional AND ( far different) aesthetic aspects of the brackish environment than has been embraced before. Our approach to brackish is a little different than the "throw in a couple of rocks and white sand, a few teaspoons of salt per gallon, add some Monos and Mollies, and you're good to go!" concept that you've seen for a long time in hobby literature. It's not quite as sterile and pristine as the world we've played with before in this sector of the hobby...

To be quite honest, I think that the current "version" of brackish water aquariums is a good part of why they've remained relatively obscure for so long...they are, well...kind of monochromatic, shockingly unrealistic, and dare I say, boring! Sure, there are always exceptions, but the majority of brackish tanks I've seen set up in that manner have, IMHO, left little to generate more than an occasional acknowledgment from the aquarium world at large.

I think we can/will do better.

Our focus is on trying to replicate and understand the complex web of life that occurs in brackish water habitats, and we'll evolve the practice and appreciation of this unique niche just like we've all done with blackwater. In fact, the approach that we take to brackish is unlike what has previously been taken before, but one that is incredibly familiar to you as "tint enthusiasts."

And of course, there are a few components which, in our opinion, "power" the brackish water, botanical-style system: Mud, leaf litter...and mangroves.

Mangroves are woody plants which grow at the interface between land and water in tropical and sub-tropical regions. Mangroves are what botanists call "halophytes"- plants that thrive under salty conditions. And they LOVE high-nutrient substrates! In many brackish-water estuaries in the tropics, rivers deposit silt and mud, which generates nutrients, algae, and fosters the development of other small organisms that form the base of the food chain. This "food chain" is very similar to what we've been talking about in our botanical-style blackwater aquariums.

The nutrients the mangroves seek lie near the surface of the mud, deposited by the tides. Since there is essentially no oxygen available in the mud, there is no point in the mangroves sending down really deep roots. Instead, they send out what are called "aerial roots" (that's what gives them their cool appearance, BTW), sort of "hanging on" in the mud, which also gives the mangroves the appearance of "walking on water."

And of course, the leaves which mangroves regularly drop form not only an interesting aesthetic and "structural" component of the habitat (and therefore, the aquarium!)- they contribute to the overall biological diversity and "richness" of the habitat.

Fungi and bacteria in brackish and saltwater mangrove ecosystems help facilitate the decomposition of mangrove material, just like in their pure freshwater counterparts. Interestingly, in scientific surveys, it's been determined that bacterial counts are generally higher on attached mangrove leaves than they are on freshly-fallen leaf litter, and this is kind of interesting, because ecologists feel that attached, undamaged mangroves leaves don't release much tannin, which, as we know might have some ate-bacterial properties. However, it's also been found that materials like humic acid, which are abundant in the mangroves, stimulate phytoplankton growth there.

Interesting, right?

The leaves of mangroves, as they break down, become subject to both leaching of the compounds in their tissues, as well as microbial breakdown. Compounds like potassium and carbohydrates are commonly leached quickly, followed by tannins. Fungi are the "first responders" to leaf drop in mangrove communities, followed by bacteria, which serve to break don't the leaves further.

So yeah, we love the idea of creating your brackish water ecosystem around leaves and mangroves (either alive, or just utilizing the roots/branches to simulate the appearance of the mangrove root system).

I'm really excited about seeing how we develop our brackish water systems, vis a vis the function of the microcosms we foster. I think that the lessons we've learned from our blackwater work will translate very nicely into this slightly salty realm!

Stay curious. Stay experimental. Stay observant...Stay salty...

And Stay Wet!

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

The water turns brown...

One of the things I've greatly enjoyed over the years (and one that has made me a consistent pain in the ass for the hobby in general), is my love of questioning stuff that we seem to take as "hobby gospel" for generations. For example, the idea that an aquarium needs to be an immaculate, sparkling clear system without any materials or organics accumulating on the bottom or elsewhere in the system.

Even now, some three years since the launch of Tannin Aquatics- well into a more "everyday" approach to creating and maintaining blackwater, botanical-style aquariums, we still occasionally hear the admonition that we're doing things in a "reckless, dangerous manner" that can create disastrous consequences for our fishes. The implication is that somehow we're going sort of "contrary" to the way people have kept aquariums successfully for generations, and that this is simply reckless.

Well, yeah. It's contrary. Of course.

But "reckless?" I think not.

And guess what? A mismanaged "classic" freshwater community tank can spell disaster for its inhabitants if you don't maintain it properly.

You can't ignore the way nature functions and expect a success in a glass box.

News flash.

And yes, aquariums with high quantities of organic materials breaking down in the water column add to the biological load of the tank, requiring diligent management. This is not shocking news. Frankly, I find it rather amusing when someone tells me that what we do as a community is "reckless", and that our tanks look "dirty." As if we don't see that or understand why...

Now, when you think about it, the botanical-style aquarium sort of falls into that category, huh? Leaves and botanicals certainly add to the organic load, and are most definitely materials which accumulate within the tank, right? And they look very different than what we are used to seeing.

The water turns brown.

We've rehashed that like 4,000,000 times here.

Is this a negative?

If you look at a lot of the underwater photos and videos taken in the natural habitats of our fishes that, thankfully, are becoming more and more popular and abundant than ever, you see a lot of "stuff" in the water column, on the bottom, etc. And the water is not always crystal-clear blue white, right? It's...well, brown. Natural streams are not always the pristine-looking "nature aquarium" subjects of our dreams, are they?

No, not really.

Rather, many of the environments from which the fishes we love hail are anything but "pristine" assemblages of rock, wood, and plants. They have a lot of "stuff" in them, ranging from clumps of algae to seed pods, palm fronds, etc, up to submerged logs.

Now, in many of the photos and videos that I've poured over in recent years, the most common items you see on the bottom are...wait for it- leaves! Yeah, they're everywhere...in almost every aquatic environment you see, ranging from ponds to slow moving jungle streams, to larger rivers. Sure, in some swift-current scenarios, you're less likely to see large beds of leaves, but you still see them.

Which is why, when I first started playing with leaves, that I was so astounded that more hobbyists haven't incorporated them into their displays.

Oh, sure, you'd see them in the tanks of a few biotope freaks, which were seen largely as "fringe-dwelling" novelties- and maybe in some setups of dedicated cichlid and betta breeders- but that was really the extent of it. Once I got over my "reefkeeping" mindset of not adding all sorts of stuff to a tank, I was able to look at it objectively.

As we've discussed ad naseum here, I think one of the biggest initial reason was that the look was utterly "alien" to our aquarium aesthetic sensibilities. I mean, "Clutter" on the bottom? Brown water?

How is that "natural?"

And, perhaps even more important, the idea of throwing things like leaves and seed pods into a tank- a carefully managed artificial world, seemed like simply "polluting" what was long suggested should be as pristine a system as possible. And that brown water= "dirty", right?

Yeah. A lot of aquarists still equate tannin-stained water with "dirt."

I hear this a lot when I speak at clubs, showing hobbyists the wonders of the blackwater aquarium world. It's still kind of hard for many to get their heads around, despite us showing videos and pics up the ass of all sorts of blackwater habitats.

I know, I know- an aquarium is not an open, natural system, yet if well-managed, it can function beautifully for years and years, right?

So there are really two huge factors that have been touted as the reason for not doing what we are doing over the years: One is based on the prevailing mindset of what the hobby thinks a tank should look like, and the is other based on a perception that there is a negative the environmental impact on a "carefully constructed aquarium environment." Both are valid points, I suppose- although the comical part to me is the automatic assumption that we're not working with "carefully constructed aquatic environments" here.

Why? Because the water is...brown?

After years of experimenting with leaves, botanicals, and other natural materials in aquariums, and with a growing global community of hobbyists doing the same daily, the mental roadblocks to this approach are starting to fall. We're seeing all sorts of tanks being created by all sorts of hobbyists, which in years past would garner far more hushed whispers and criticisms than gasps of envy.

It's taken a while, but the pockets of resistance are fewer and farther in between than in years past, at least from where I sit!

So, it's still necessary to address this stuff from time to time, as there are still many unanswered questions from those not familiar with our game here.

And, with the above historic concerns in mind, what exactly is the impact of a bunch of stuff on the bottom in your tank?

Well, on the most superficial of levels, the water turns brown. We know that.

And, if your water has a lower general hardness, it shifts towards an acidic pH. Again, something we already know. So what are the other impacts? Well, for one thing, decomposing material of plant origin probably contains stuff like sugars, lignin, and all sorts of organic compounds. Some of these substances are utilized by various organisms, like bacteria and fungi, which work to break it down. Algae, and plants (if present) will utilize some of them as well, such as phosphates, nitrates, etc.

Now, the "organics" that we have used as a red flag to discourage throwing this stuff into tanks in years past can accumulate and even be problematic- if you don't have necessary control and export processes in place to deal with them. What would these processes be? Well, to start with- Decent water movement and filtration, to physically remove any debris. Use of some chemical filtration media, such as organic scavenger resins, which tend not to remove the "tint", but act upon specific compounds, like nitrate, phosphate, etc.

And of course, water exchanges. Yeah, the centuries old, tried-and-true process of exchanging water is probably the single most important aspect of nutrient control and export for any system, traditional, botanical, etc. There is no substitute for diluting organic impurities through regularly-scheduled water changes, IMHO.

This isn't some revelation.

And those are only some of the most obvious aspects of nutrient control and export, really. It even gets down to stuff like not overstocking and overfeeding your tank. Carefully removing uneaten food.

Nothing that is really out of the ordinary, right?

I can tell you from experience in every botanical-style tank that I have set up since 2012, that I have never experienced more than barely detectible levels of nitrate (like, less than 5ppm, if at all) and phosphate (like 0.05ppm or less). This despite large amounts of leaves, seed pods, etc. being present. I don't have some "magic touch."

Sound, time-tested husbandry techniques will make managing a heavily-botanical-laden aquarium as easily manageable as any other aquarium system, in my experience.

Certainly as forgiving as any Mbuna tank, "high tech planted tank", or "SPS" reef system that I've played with over the years! We just utilize a slightly different "operating system" to do what hobbyists have done forever.

When people see things like biofilms, fungi, and possibly even a little algae forming on botanicals and wood in an aquarium for the first time, the initial reaction for many would be to freak out and immediately submit to the "I told you so's" offered up by the "armchair experts" who've never ran a botanical-style tank, yet feel compelled to offer "advice" on how to "rehab" it. As a newcomer to this tinted world, you might be rattled enough to "take corrective action!"

Before running off and tearing your tank apart- examine it.

Look at the water chemistry. Look at the fishes.

Take another look at some underwater pics and videos of natural habitats and realize that this is exactly what to expect in a system where these materials are present. And take comfort in knowing that, in an aquarium, these biofilms are part of the normal natural function of systems with materials like leaves and botanicals, and the heaviest concentrations will typically subside once the aquarium establishes itself (great news if you just can' get over that). A "mental shift", patience, and the passage of time are the main "corrective measures" you need to employ here.

Oh, and a desire to understand what's happening...

Now again, I'm speaking from my personal experience with many tanks set up in this fashion. I'm not a scientist, having completed a huge number of water quality experiments of every conceivable type on my tanks. And I'll tell you categorically that if you approach the management of a botanical-style blackwater aquarium in a nonchalant, irresponsible manner, you'll be in for a humbling experience.

I'll say it yet again: In my experience, there is nothing inherently more challenging or more dangerous about these types of tanks than there is with any other speciality system. The fact that the water is brown doesn't mean that a well-managed tank is any closer to disaster than any well-managed clear water system.

I think that I do a pretty good job of managing the water quality in my aquariums. There's no magic here. Like many of you, I do the work necessary to keep my aquariums operating in a healthy state. In my opinion, NO aquarium of ANY type is "set and forget", and you'll be in for a rude awakening with a blackwater, botanical-style tank- or any tank- if you take that approach.

And, with the scientifically-validated benefits to fish from humic substances present in blackwater, the "upside" to what was long popularly perceived as dirty tanks is becoming more and more obvious. And the aesthetics, dynamics, and interest created in your aquarium by "that brown water" can become a fascinating, obsessive new passion for you within the aquarium hobby if you're not careful!

For those of us who "feel it", this is a real enlightenment...a compulsion. An obsession!

So, to those of you who face the occasional "tease" from your clear-water-loving brethren, keep applying skill and common sense to your aquariums. Delight in the difference.

Yeah, the water turns brown.

We get that.

Stay focused on husbandry. Stay engaged with the community. Lead by example. Experiment. Educate. Enlighten.

Share what you've learned.

Stay excited. Stay fascinated.Stay on top of this stuff...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics