- Continue Shopping

- Your Cart is Empty

Life continues...painfully at times. But it does.

Rivers flow. Rains fall. Water surge, then recede. Life evolves, grows, and ends...and from endings, come new beginnings. New seasons, new sources of energy, new generations of life.

Today, I was sad to hear of the passing of our dear friend, James Sheen of Blackwater UK. It was a devastating shock and to say it created a void is to make a ridiculous understatement, for sure. James was an instrumental part of the botanical aquarium method movement. He was a passionate, devoted hobbyist, inspirational entrepreneur, devoted father...and all-around great human being.

James was literally one of the first hobbyists who reached out to me when I started Tannin in 2015. He was so excited, so passionate, and so in to this amazing world. He and I used to share a lot of ridiculous ides, theories, and thoughts about the hobby. God knows, the poor bloke had to listen to my ramblings about everything in the hobby. We'd commiserate about just about everything in the hobby and business sector that he helped to create.

James tirelessly devoted himself to growing the hobby in The UK...and grow it he did. He helped shape our little sector from circus side show status into full-blown hobby speciality. And he did it all with class, style, and incredible patience. He wore his heart on his sleeve and was never afraid to speak his mind- even if he took an unpopular position. I think that's what I'll miss most about him. He was a loyal friend, a funny guy, and kindred spirit. A bright spot in this dark, tinted world.

And I think I can take some solace from our love of Nature, and the lessons it teaches us...such as the fact that life arises anew, often at times and in places which seem somehow hopelessly inhospitable.

Life endures in different, evolving forms. A legacy from what was. The promise of what will be.

James and Ben (from Betta Botanicals)and I have been chatting a lot in recent weeks, as the two tried to coax me out of this self-imposed "sabatical" I placed myself in. And, yeah, I'm back...I'm ready.

I'm sad. I'm devastated. But I'm back.But this isn't about me...we can talk about that later. Right now, let's take a few moments to celebrate James and all he did for the hobby.

He leaves behind a loving wife, children...and a great legacy.

We can best honor him by simply doing what we do best- enjoying this amazing hobby that we all love so much.

James would like that, I'd think.

Hug your loved ones. Stay passionate. Stay true to yourself. Take care of yourself.

And to you, James...

Stay Wet, buddy.

I'll catch up with the rest of you later on. I need to cry this out a bit.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Tannin Aquatics

Continuity.

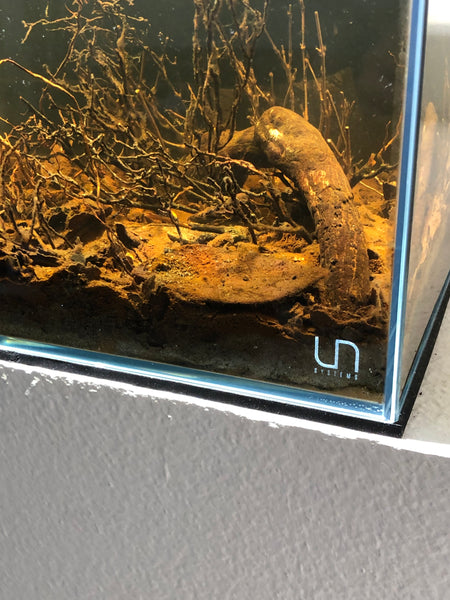

I've embarked on some "remodels" of some of the aquariums in my home office, and it's been a most interesting experience- as it always is. I've taken a slightly different approach to these "makeovers" over time. Specifically, one of the things I've done in recent years is to keep the substrate layers from the existing tanks and "build on them."

In other words, I'm taking advantage of the well-established substrate layers, complete with their sediments, decomposing leaves and bits of botanicals, and simply building upon them with some additional substrate and leaves. I've done this many times over the years- it's hardly a "game-changing" practice, but it's something not everyone recommends or does.

I believe that preserving and building upon an existing substrate layer provides not only some biological stability (ie; the nitrogen cycle), but it has the added benefit of maintaining some of the ecological diversity and richness created by the beneficial fuana and the materials present within the substrate. I know many 'hobby old timers" might question the safety- or the merits-of this practice, mentioning things like "disturbing" the bacterial activity" or "releasing toxic gasses", etc. I simply have never experienced any issues of this nature from this practice. Well maintained systems generally are robust and capable of evolving from such disturbances.

I see way more benefits to this practice than I do any potential issues.

Since I tend to manage the water quality of my aquariums well, I have never had any issues, such as ammonia or nitrite spikes, by doing this- in fresh or saltwater systems. It's a way of maintaining stability- even in an arguably disruptive and destabilizing time!

This idea of "perpetual substrate"- keeping the same substrate layer "going" in successive aquarium iterations- is just one of those things we can do to replicate Nature in an additional way. Huh? Well, think about it for just a second...

In Nature, the substrate layer in rivers, streams, and yeah, flooded forests and pools tends to not completely wash away during wet/dry or seasonal cycles.

Oh sure, some of the material comprising the substrate layer may get carried away by currents or other weather dynamics, but for the most part, a good percentage of the material- and the life forms within it- remains.

So, by preserving the substrate and "refreshing" it a bit with some new materials (ie; sand, sediment, gravel, leaves, and botanicals), you're essentially mimicking some aspects of the way Nature functions in these wild habitats. And, from an aquarium management perspective, consider the substrate layer a living organism (or "collective" of living organisms, as it were), and you're sure to look at things a bit differently next time you re-do a tank!

It's hardly "radical" in it's departure- you've likely done a version of this hundreds of times during your aquarium hobby career: It's the idea of keeping your aquarium more-or-less "intact" while moving on to a new iteration.

In other words, let's say that you're kind of over your Southeast Asian Cryptocoryne biotope, and ready to head to South America. So, rather than tearing up the entire tank, removing all of the plants, the hardscape, the leaves and botanicals, and the substrate, you opt to remove say, only the plants, some botanicals, and the hardscape materials from the tank; exchange a good quantity of the water.

Woooah! Crazy! You fucking rebel...

I know. I know. This isn't exactly earth-shattering.

On the other hand, it IS a bit of a departure, at least on a philosophical level, from the idea of just "starting over from scratch" that is the more common approach in our hobby.

And, in the world of the botanical-method aquarium, the idea of leaving the substrate and leaf litter/botanical "bed" intact as you "remodel" isn't exactly a crazy one. And conceptually, it's sort of replicates what occurs in Nature, doesn't it?

Yeah, think about this for just a second.

As we almost constantly discuss, habitats like flooded forests, meadows, vernal pools, igarape, and swollen streams tend to encompass terrestrial habitats, or go through phases where they are terrestrial habitats for a good part of the year.

In these wild habitats, the leaves, branches, soils, and other botanical materials remain in place, or are added to by dynamic, seasonal processes. For the most part, the soil, branches, and a fair amount of the more "durable" seed pods and such remain present during both phases.

The formerly terrestrial physical environment is now transformed into an earthy, twisted, incredibly rich aquatic habitat, which fishes have evolved over eons to live in and utilize for food, protection, and complex, protected spawning areas.

All of the botanical material-shrubs, grasses, fallen leaves, branches, seed pods, and such, is suddenly submerged; often, currents re-distribute the leaves and seed pods and branches into little pockets and "stands", affecting the (now underwater) "topography" of the landscape.

Leaves begin to accumulate. Detritus settles...

Soils dissolve their chemical constituents- tannins, and humic acids- into the water, enriching it. Fungi and micororganisms begin to feed on and break down the materials. Biofilms form, crustaceans multiply rapidly. Fishes are able to find new food sources; new hiding places..new areas to spawn.

Continuity.

It's a concept that we should think about more when managing and evolving our tanks: The idea that Nature doesn't just "break down" a habitat and start from scratch. Rather, it simply evolves and reacts to changes in the environment.

That should be our model. That should be our process.

You can change up an aquarium without tearing it completely apart and starting entirely from scratch. You can leave substrate intact, and keep a fair amount of the botanical material that's already in the tank "in play."

IMHO, like 90% of the battle in establishing successful botanical method aquariums (or any type of system, really) is to introduce and manage a biome of life forms which will help the tank flourish over the long term.

If you approach things with the mindset that detritus is food for someone, you won't feel the sense of urgency to siphon it all out when re-working your tank. Rather, you'll understand that keeping it in the aquarium substrate is beneficial; it literally helps "power" the ecology of the aquarium. They key, of course, is not to have it sitting in there in excess.

Keeping the ecological "engine" which powers your tank alive during these transitions is the key to a "continuous" aquarium- one which can endure multiple "thematic" changes over it's (possibly indefinite) service lifetime.

It's all about ecology. Bringing up a biome. Creating a living system within the confines of an aquarium. Understanding that some of the things that we've taken for granted, or even things that we've been afraid of, are among the most important things that we can do for our tanks.

The idea of keeping a tank going indefinitely in many permutations is nothing new or novel in the aquarium hobby, really. However, thinking about it holistically, and executing a plan to keep it going is a different thing altogether.

Perhaps it is most important to look at biology over almost any other aspect of aquarium keeping. In other words, to accept that the biological interactions and the establishment of a biome within the aquarium are the keys to pretty much everything that we do.

Keeping a tank over the long term is not all that challenging, once we accept the fact that creating and maintaining the biome of the system is of utmost importance, the actual processes and techniques are really secondary. And botanical materials in the aquarium helps create a long term habitat for the biome- a collection. of microorganisms and other life forms- to thrive and multiply.

Yeas, one of the underlying "core principles" of the botanical method aquarium is that having a bunch of leaves and other botanical materials present in the aquarium fosters a larger, more diverse population of these valuable organisms, capable of offering supplemental food sources to fishes and processing organics, thus creating a more stable, robust ecology in the aquarium.

With a matrix of materials present, the bacteria (and their biofilms- as we've discussed a number of times here) have not only a "substrate" upon which to attach and colonize, but an "on board" food source which they can utilize as needed.

Facultative bacteria, adaptable organisms which can use either dissolved oxygen or oxygen obtained from food materials such as sulfate or nitrate ions, would also be capable of switching to fermentation or anaerobic respiration if oxygen is absent.

Hmm...fermentation.

Well, that's likely another topic for another time. Something we've hinted at in the past, but haven't really analyzed much in the aquarium context. We'll revisit it. For now, let's focus on some of the other more "practical" aspects of this "biome" thing.

Like...food production for our fishes.

In the case of our fave aquatic habitats, like streams, ponds, and inundated forests, epiphytes, like biofilms and fungal mats are abundant, and many fishes will spend large amounts of time foraging the "biocover" on tree trunks, branches, leaves, and other botanical materials.

The biocover consists of stuff like algae, biofilms, and fungi. It provides sustenance for a large number of fishes all types.

And of course, what happens in Nature also happens the aquarium- if we allow it to, right? And it can function in much the same way?

Yeah.

I have long felt that a botanical-method aquarium, complete with its decomposing leaves and seed pods, can serve as a sort of "buffet" for many fishes- even those who's primary food sources are known to be things like insects and worms and such. Detritus and the microorganisms within it can provide an excellent supplemental food source for our fishes!

Sustenence...from the microbiome.

It's well known that in many habitats, like inundated forests, etc., fishes will adjust their feeding strategies to utilize the available food sources at different times of the year, such as the "dry season", etc.

And it's also known that many fish fry feed actively on bacteria and fungi in these habitats...So I suggest once again that a botanical-style aquarium could be an excellent sort of "nursery" for many fish and shrimp species!

Again, it's that idea about the "functional aesthetics" of the, botanical-style aquariums. The idea which acknowledges the fact that the botanicals we use not only look cool, but they provide an important function (supplemental food production) as well. As we repeat constantly, the "look" is a collateral benefit of thef unction.

This is a profoundly important idea.

Perhaps arcane to some- but certainly not insignificant.

And who we do a tank "makeover", I feel that there is little sense in siphoning out the detritus and decomposed botanical materials which may have accumulated in the tank. Because this stuff will continue to provide an ecological "foundation" for your "makeover" aquarium. Just "build" upon it, like Nature does.

Nature doesn't waste anything- and neither should we.

And of course, we've talked before about the "botanical nursery" concept- creating an aquarium for fish fry that has a large quantity of decomposing botanicals and leaves to foster the production of these materials, which serve as supplemental food for your fish fry.

I have done this before myself and can attest to its viability. You fishes will have a constant supply of "natural" foods to supplement what you are feeding them in the early phases of their life.

Learn to make peace with your detritus! As always, look to the wild aquatic habitats of the world for an example of how this food source functions within the greater biome.

I'm fascinated by the "mental adjustments" that we need to make to accept the aesthetic and the processes of natural decay, fungal growth, the appearance of biofilms, and how these affect what's occurring in the aquarium. It's all a complex synergy of life and aesthetic, and once we grasp what's happening in our tanks, we can truly understand how important it all is.

And realizing that this accumulation of biological material can all provide a certain something- in this case, ecological continuity- for your aquarium in many iterations and phases of its existence is of profound importance. This is an invaluable asset provided to us free of charge by Nature, ready for use...if we allow it to remain in our tanks.

Our entire approach is about creating a biome- a little closed ecosystem, which requires us to support the organisms which comprise it- at every level.

Just like what Nature has been doing for eons.

Stay consistent. Stay observant. Stay curious. Stay diligent. Stay patient...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Streaming along...

There is a whole, fascinating science to river and stream structure, and with so many implications for understanding how these structures and mechanisms affect fish population, occurrence, behavior, and ecology, it's well worth studying for aquarium interpretation!

Leaf litter beds form in what stream ecologists call "meanders", which are stream structures that form when moving water in a stream erodes the outer banks and widens its "valley", and the inner part of the river has less energy and deposits silt- or in our instance, leaves.

Did you get that part where I mentioned that the lower-energy parts of the water courses tend to accumulate leaves and sediments and stuff?

It's logical, right? And it's also interesting, because, as we know, fishes and their food items tend to aggregate in these areas, and embracing the "theme" of a litter/botanical bed or even wood placement, in the context of a stream structure in the aquarium is kind of cool!

You could build upon, structure, and replace leaves and botanicals in this "framework"- like, indefinitely...sort of like what happens in the "meanders in streams!"

In Nature, the rain and winds also effect the depth and flow rates of many of the waters in this region, with the associated impacts mentioned above, as well as their influence on stream structures, like submerged logs, sandbars, rocks, etc.

Stuff gets redistributed constantly.

Is there an aquarium "analog" for these processes?

Sure!

We might move a few things around now and again during maintenance, or perhaps current or the fishes themselves act to redistribute and aggregate botanicals and leaves in different spots in our aquairums.

And how we structure the more "permanent" hardscape features in our tanks has a profound influence on how botanical materials can aggregate.

So, rather than covering the whole bottom of your tank with leaves, would it be cool to create some sort of hardscape structure- with driftwood, etc., to retain or keep these items in one place..to create a "framework" for a long-term, organized, specifically-placed litter bed.

The composition of bottom materials and the depth of the channel are always changing in response to the flow in a given stream, affecting the composition and ecology in many ways. I'll probably state this idea more than once in this piece, because it's really important:

Every stream is unique. Although there are standard structural or functional elements common to many streams, each stream is essentially a "custom response" to local ecological, topographical, meteorological, and biological factors.

Permanent streams will often have different volume and material composition (usually finely-packed sands and gravels, with lots of smooth stones) than more intermittent streams, which are the result of inundation caused by rain, etc., or even so-called "ephemeral" streams, often packed with leaves and lighter sediments, which typically occur only immediately after rain events (which means they usually don't have fish in them unless they are washed into them from more permanent watercourses).

The latter two stream types are typically more affected by leaves, botanical debris, branches, and other materials. Like the igarapes ("canoe ways") of Brazil...little channels and rivulets which come and go with the seasonal rains. And then, there's those flooded Igapo forests we obsess over.

In the overall Amazon region (you knew I was sort of headed back that way, right?), it sort of works both ways, with the rivers influencing the surrounding land...and then the land "giving" some of the materials back to the rivers...the extensive lowland areas bordering the river and its tributaries, known as varzeas (“floodplains”), are subject to annual flooding, which helps foster enrichment of the aquatic environment.

Much of them come from trees.

Yeah, trees.

The materials that comprise the tree are known in ecology as "allochthonous material"- something imported into an ecosystem from outside of it. (extra points if you can pronounce the word on the first try...) And of course, in the case of trees, this also includes includes leaves, fruits and seed pods that fall or are washed into the water along with the branches and trunks that topple into the stream.

You know, the stuff we obsess over around here!

Although many streams derive their food base from leaves and organic matter, there is a lot of other material present that contributes to its structure. Think along those lines when scheming your next aquarium. Ask yourself what factors would contribute to the bottom composition of the area you're taking inspiration from.

There seems to be a pervasive mindset within the botanical method aquarium hobby that you need to incorporate a wide variety of botanicals into every aquarium. I would like to go on record right now to state that this is simply untrue. You can use as little or as much diversity of materials as you'd like;

Nature doesn't have a "standard" for this!

It's a "guideline" which I believe vendors have placed into the collective consciousness of the hobby for reasons that are not entirely altruistic. Personally, I will only use a one or two types of botanical materials in a given aquarium. Maybe three, but that's typically it. This mindset was forged by both my aesthetic preferences and my studying of the characteristics of many of the natural habitats which we model our aquariums after.

They simply don't have an unlimited variety of materials present. Rather, the composition of the accumulated materials in most wild aquatic habitats is limited- often based upon the plants in the immediate vicinity, as well as other factors, like currents (when present) and winds. During storms, materials can be re-distributed from outside of the immediate environment, adding to the diversity of accumulation.

In general, one of the ecological roles of streams are to distribute materials throughout the greater ecosystem. Streams have interesting morphologies. It's interesting to consider the structural components of a stream, to get a better picture of how it forms and functions. What are the key components of streams?

Well, there is the top end of a stream, where its flow begins..essentially, its source. The "bottom end" of a stream is known as its "mouth." In between, the stream flows through its main course, also known as a "trunk." Streams gain their water through runoff, the combined input of water from the surface and subsurface.

Streams which flow over stony, open bottoms, free from natural obstacles like tree trunks and such, tend to develop a rich algal turf on their surfaces.

While not something a lot of hobbyists like to see in their tanks (with the exception of Mbuna guys and weirdos like me), algae-covered stones and rocks are entirely natural and appropriate for the bottom of many aquariums! (enter a tank with THAT in the next international aquascaping contest and watch the ensuing judge "freak-out" it causes! )

Grazing fishes, of course, will feed extensively on or among these algal films, and would be logical choices for a stony-bottom-themed aquarium. Like Labeo ("Sharks"), Darter characins, and barbs. When we think about the way natural fish communities are assembled in rivers and streams, it's almost always as a result of adaptations to the physical environment and food resources.

Now, not everyone wants to have algae-covered stones or a mass of decomposing leaves on the bottom of their aquarium. I totally get THAT! However, I think that considering the role that these materials play in the composition of streams and the lives of the fishes which inhabit them is important, and entirely consistent with our goal of creating the most natural, effective aquariums for the animals which we keep.

As a hobbyist, you can employ elements of these natural systems in a variety of aquariums, using any number of readily-available materials to do the job. And, let's face it; pretty much no matter how we 'scape a tank- no matter how much- or how little- thought and effort we put into it, our fishes will ultimately adapt to it.

They'll find the places they are comfortable hiding in. The places they like to forage, sleep and spawn. It doesn't matter if your 'scape consists of carefully selected roots, seed pods, rocks, plants, and driftwood, or simply a couple of clay flower pots and a few pieces of egg crate- your fishes will "make it work."

As aquarists, observing, studying, and understanding the specifics of streams is a fascinating and compelling part of the hobby, because it can give us inspiration to replicate the form and more important- the function- of them in our tanks!

Now, you're also likely aware of the fact that we're crazy about small, shallow bodies of water, right? I mean, almost every fish geek is like "genetically programmed" to find virtually any random body of water irresistible!

Especially little rivulets, pools, creeks, and the aforementioned forest streams. The kinds which have an accumulation of leaves and botanical materials on the bottom. Darker water, submerged branches- all of that stuff...

You know- the kind where you'll find fishes!

Happily, such habitats exist all over the world, leaving us no shortage of inspiring places to attempt to replicate. Like, everywhere you look!

In Africa for example, many of these little streams and pools are home to some of my fave fishes, killifish! This group of fishes is ecologically adapted to life in a variety of unusual habitats, ranging from puddles to small streams to mud holes. However, many varieties occur in those streams in the jungles of Africa.

And many of these little jungle streams are really shallow, cutting gently through accumulations of leaves and forest debris. Many are seasonal. The great killie documenter/collector, Col. Jorgen Scheel, precisely described the water conditions found in their habitat as "...rather hot, shallow, usually stagnant & probably soft & acid."

Ah-ah! We know this territory pretty well, right?

I think we do...and understanding this type of habitat has lots of implications for creating very cool biotope-inspired aquariums.

And why not make 'em for killifish?

So, yeah- we keep talking about "very shallow jungle streams." How shallow? Well, reports I've seen have stated that they're as shallow as 2 inches (5.08cm). That's really shallow. Seriously shallow! And, quite frankly, I'd call that more of a "rivulet" than a stream!

"Virtually still, with a barely perceptible current..." was one description. That kind of makes my case!

What does that mean for those of us who keep small aquariums?

Well, it gives us some inspiration, huh? Ideas for tanks that attempt to replicate and study these compelling shallow environments...

Now, I don't expect you to set up a tank with a water level that's 2 inches deep..And, although it would be pretty cool, for more of us, perhaps a 3.5"-4" (8.89-10.16cm) of depth is something that can work? Yeah. Totally doable. There are some pretty small commercial aquariums that aren't much deeper than 6"-8" (20.32cm).

We could do this with some of the very interesting South American or Asian habitats, too...Shallow tanks, deep leaf litter, and even some botanicals for good measure.

How about a long, low aquarium, like the ADA "60F", which has dimensions of 24"x12"x7" (60x30x18cm)? You would only fill this tank to a depth of around 5 inches ( 12.7cm) at the most. But you'd use a lot of leaves to cover the bottom...

Yeah, to me, one of the most compelling aquatic scenes in Nature is the sight of a stream meandering into the forest.

There is something that calls to me- beckons me to explore, to take not of its intricate details- and to replicate some of its features in an aquarium- sometimes literally, or sometimes,. just taking components that I find compelling and utilizing them.

An important consideration when contemplating such a replication in our tanks is to consider just how these little forests streams form. Typically, they are either a small tributary of a larger stream, with the path carved out by rain or erosion over time. In other situations, they may simply be the result of an overflowing tributary during the rainy season, and as the waters recede later in the year, they evolve into smaller streams meandering through vegetation.

Those little streams fascinate me.

In Brazil, they are known as igarape, derived from the native Brazilian Tupi language. This descriptor incorporates the words "ygara" (canoe) and "ape"(way, passage, or road) which literally translates into "canoe way"- a small body of water which forms a route navigable by canoes.

A literal path through the forest!

These interesting little tributaries areare shaded by trees at the margins, and often cut for many kilometers through dense rain forest. The bottoms of these tributaries- formerly forest floor- are often covered with seed pods, twigs, leaves, and other botanical materials from the vegetation above and surrounding them.

Although igapó forests are characterized by sandy acidic soils that have a low nutrient content, the tributaries that feed them are often found over a fine-grained, whitish sand, so as an aquarist, you a a lot of options for substrate!

In this world of decomposing leaves, submerged logs, twigs, and seed pods, there is a surprising diversity of life forms which call this milieu home. And each one of these organisms has managed to eke out an existence and thrive.

A lot of hobbyists not familiar with our aesthetic tastes will ask what the fascination is with throwing palm fronds and seed pods into our tanks, and I tell them that it's a direct inspiration from Nature! Sure, the look is quite different than what has been proffered as "natural" in recent years- but I'd guarantee that, if you donned a snorkel and waded into one of these habitats, you'd understand exactly what we are trying to represent in our aquariums in seconds!

Streams, rivulets...whatever they're called- they beckon us. Compel us. And challenge us to understand and interpret Nature in exciting new ways in our aquariums.

I think we're starting to see a new emergence of a more "holistic" approach to aquarium keeping...a realization that we've done amazing things so far, keeping fishes and plants in a glass or acrylic box with applied technique and superior husbandry...but that there is room to experiment and push the boundaries even further, by understanding and applying our knowledge of what happens in the real natural environment.

Think differently. Expand your horizons.

Stay curious. Stay creative. Stay brave. Stay studious...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Big Thoughts on a Tiny Tetra- and the "difficulty" of working with some fishes...

After a lifetime in the hobby, I tend to find myself continuously drawn to fishes which, at first glance, aren't all that rare, or even "challenging" to keep...yet, somehow are seldom kept in conditions which they have adapted to live under for eons.

Here's a favorite example:

Everyone knows the Neon Tetra, Paracheirodon inessi. It's a strong candidate for the title of "Official fish of the Aquarium Hobby!" This fish is inescapable...almost universally recognized by even non-aquarium-hobbyists.

Of course, there other members of the genus Paracheirodon which hobbyists have become enamored with, such as the diminutive, yet equally alluring P. simulans, the "Green Neon Tetra." Topping out at around 3/4" (about 2cm) in length, it's certainly deserving of the hobby moniker of "nano fish!"

You know, a little fish that you could keep in groups in a relatively small tank. Or, for that matter- a LARGE group in a LARGER aquarium!

You can keep these little guys in nice -sized aggregations...I wouldn't necessarily call them "schools", because, as our friend Ivan Mikolji beautifully observes, "In an aquarium P. simulans seem to be all over the place, each one going wherever it pleases and turning greener than when they are in the wild."

This cool little fish is one of my fave of what I call "Petit Tetras." Hailing from remote regions in the Upper Rio Negro and Orinoco regions of Brazil and Colombia, this little fish is a real showstopper who it's in peak health! According to ichthyologist Jacques Gery, the type locality of this fish is the Rio Jufaris, a small tributary of the Rio Negro in Amazonas State.

One of the rather cool highlights of this fish is that it is found exclusively in blackwater habitats.

Specifically, they are known to occur in habitats called "Palm Swamps"( locally known as "campos") in the middle Rio Negro. These are pretty cool shallow water environments! Interestingly, P. simulans doesn't migrate out of these shallow water habitats (less romantically called "woody herbaceous campinas" by aquatic ecologists) like the Neon Tetra (P. axelrodi) does. It stays to these habitats for its entire lifespan.

These "campo" habitats are essentially large depressions which do not drain easily because of the elevated water table and the presence of a soil structure, created by our fave soil, hydromorphic podzol! "Hydromorphic" refers to s soil having characteristics that are developed when there is excess water present all or part of the time.

(Image by G. Durigan)

Are you thinking what I'm thinking?

Yeah, the potential exists to create a really realistic functional representation of these habitats (a' la "Urban Igapo") with soils, plants, and a little bit of research.

So, if you really want to get hardcore about recreating this habitat, you'd use immersion-tolerant terrestrial plants, such as Spathanthus unilateralis, Everardia montana, Scleria microcarpa, and small patches of shrubs such as Macairea viscosa, Tococa sp. and Macrosamanea simabifoli. And grasses, like Trachypogon.

Of course, our fave palm, Mauritia flexuosa and its common companion, Bactris campestris round out the native vegetation. Now, the big question is, can you find any of these plants? Perhaps...More likely, you could find substitutes.

I can think of a few already.

Just Google that shit! Tons to learn about those plants!

These habitats are typically choked with roots and plant parts, and the bottom is covered with leaves and fallen palm fronds...This is right up our alley, right? We've been workin g with these materials for years!

Of course, if you really want to be a full-on "baller" and replicate the natural habitat of these fishes as accurately as possible, it helps to have some information to go on! So, here are the environmental parameters from these "campo" habitats based on a couple of studies I found:

The dissolved oxygen levels average around 2.1 mg/l, and a pH ranging from 4.7-4.3. KH values are typically less than 20mg/L, and the GH generally less than 10mg/L. The conductivity is pretty low.

The water depth in these habitats, based on one study I encountered, ranged from as shallow as about 6 inches (15cm) to about 27 inches (67cm) on the deeper range. The average depth in the study was about 15" (38cm). We're talking aquarium-type depth! This is pretty cool for us hobbyists, right? Shallow! I mean, we can utilize all sorts of aquariums and accurately recreate the depth of the habitats which P. simulans comes from!

We often read in aquarium literature that P. simulans needs fairly high water temperatures, and the field studies I found for this fish do confirm this.

Average daily minimum water temperature of P. simulans habitats in the middle Rio Negro was about 79.7 F (26.5 C) between September and February (the end of the rainy season and part of the dry season). The average daily maximum water temperature during the same period averaged about 81 degrees F (27.7 C). Temperatures as low as 76 degrees' (24.6 C) and as high as 95 degrees F (35.2 C) were tolerated by P. simulanswith no mortality noted by the researchers.

Bottom line, you biotope purists? Keep the temperature between 79-81 degrees F (approx. 26 C-27C).

Researchers have postulated that a thermal tolerance to high water temperatures may have developed in P. simulans as these shallow "campos" became its only real aquatic habitat.

The fish preys upon that beloved catchall of "micro crustaceans" and insect larvae as its exclusive diet. Specifically, small aquatic annelids, such as larvae of Chironomidae (hey, that's the "Blood Worm!") which are also found among the substratum, the leaves and branches.

Now, if you're wondering what would be good foods to represent this fish's natural diet, you can't go wrong with stuff like Daphnia and other copepods. Small stuff makes the most sense, because of the small size of the fish and its mouthparts.

This fish would be a great candidate for an "Urban Igapo" style aquarium, in which rich soil, reminiscent of the podzolic soils found in this habitat, along with terrestrial vegetation. You could do a pretty functionally accurate representation of this habitat utilizing these techniques and substrates, and simply forgoing the wet/dry "seasonal cycles" in your management of the system.

There are a lot of possibilities here.

One of the most enjoyable and effective approaches I've taken to keeping this fish was a "leaf litter only" system (which we've written about extensively here. Not only did it provide many of the characteristics of the wild habitat (leaves, warm water temperatures, minimal water movement, and soft, acidic water)- it looked pretty cool, too!

And kind of forged some new hobby ground, at least aesthetically speaking, with a defacto "minimalist" aquascape!

A few general thoughts...

So, maybe you've noticed a pattern to my love of certain fishes...so much is based upon the habitats that they come from. My love for many fishes is amplified when I study and learn more about the unique habitats from which fishes come. The idea of recreating various aspects of the habitat as the basis for working with fishes is irresistible to me!

It becomes obvious to me, when I really start looking at things analytically, that my favorite fish choices seem to reflect a preference for specific habitats or ecological niches. Almost all of my faves tend to come from smaller tributaries and streams, with moderate to minimal current or water movement. These habitats are typically filled with leaf litter, branches, and submerged root systems.

Many of my favorite fishes come from flooded forests (no surprise there..), or other seasonally-inundated habitats, and have specialized feeding, spawning, and foraging habits as an adaptation to these environments. Most are dimly lit, devoid of aquatic plants, with deeply-tinted water and lots of overhanging terrestrial vegetation.

Most of them feed on allochthonous inputs (stuff that comes from outside the aquatic environment) like insects, small fruits, and flowers. Some display unusual dietary preferences, such as eating detritus, fungal growths, or lignin from submerged wood and roots. Pretty much all of them spend large amounts of time foraging.

Another common denominator of these fave fishes is that they are intimately tied to their environments. They move within, or migrate among similar habitats throughout most of their lives. As aquarium fishes, they categorically seem to do better long term when kept in tanks which replicate, to some degree, the function and form of their natural habitats. These aquatic habitats are profoundly influenced by the terrestrial habitats which surround them.

As a botanical method aquarium enthusiast, you'll get to take a good, serious look at the elegance and function of these amazing natural ecological niches, which often go unnoticed by all but the most astute observers in the wild...right from the dry comfort of you own home.

A pivotal lesson- one that made me fundamentally reconsider how to create aquariums, manage them, and work with all sorts of fishes came from studying the habitats from which our fishes come.

And after studying these habitats, I've sort of came to a simple conclusion- one that makes keeping all sorts of fishes much easier than we have commonly believed:

Meet their needs. Not yours.

It's pretty straightforward.

Despite all of this, and after a lifetime in the hobby, I say, somewhat confidently that there are no "difficult" fish.

Here's why:

It's not that a fish is inherently difficult...It simply means that we as hobbyists, if we want to be successful with a species, need to meet its needs. We need to make the effort to study its specific requirements, the habitat from which it comes from, it's nutritional needs, and its life cycle.

We need to find out how to obtain the fish from sources which have properly handled it along the chain of custody from stream to store. We have to do a little research- and that sometimes means bypassing the fish-world drivel (like this blog!) and slugging it out on Google scholar, Fishbase, ResearchGate, and other academic sources.

To many hobbyists, that's difficult.

The fish, however, is not.

Difficult tasks, like, I don't know, landing a man on the fucking moon, require us to solve literally thousands of problems and challenges, accumulate resources, and to create hardware, practices, and procedures to accomplish the goal.

And as we know, even landing man on the moon isn't impossible, right?

We landed a man on the moon back in 1969 because we decided that we wanted to do it, broke it down into a series tasks and stages (projects Mercury, Gemini, Apollo), put the effort in, overcame our mistakes and failures...and went for it.

So, while trying to keep and breed, say, Indostomus paradoxus might seem like a real problem, is there a problem here, really? Sure, on the surface, it seems like a "poster child" for "difficult", right? It's a tough to obtain, small, relatively timid fish with a tiny mouth and "specialized" feeding requirements.

Yet, break it down for a second:

It's hard to find, because there isn't a ton of demand for it. Yet, lots of people have kept and bred them over the years...Want some? Hound your suppliers, leave posts on the forums, hit up Google. DO the work. You'll find SOME, trust me. It might take a while, but you WILL find them.

The fish comes from swamps and places with muddy, soft clay-filled substrates filled with decaying leaf litter and such. Well, shit, we make a damn good soft, clay-filled muddy substrate, right?

Check.

So, there are ALWAYS things you can try- avenues you can take- to attempt to accommodate a so-called "difficult" fish, right?

You just have to WANT to.

To me, "difficulty" in the aquarium context simply means "how much do you want it?"

How much do you want it?

How many challenges do you want to meet? How patient are you? How far will you push?

Are you up for the challenge?

Ask yourself.

Stay persistent. Stay diligent. Stay tenacious. Stay patient...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Changing course.

What's wrong with doing something a bit differently than you've done it in the past?

Of course, absolutely nothing.

People ask me all the time if or how I stick with a project that seems to be going nowhere; moving in a direction contrary to what I wanted it to go in. And the reality is that, despite my enormous patience for aquairum stuff, I won't hesitate to kill something if it just doesn't ring true.

Recently, I had this idea for a different kind of aquarium. It was one of those ideas that you just kind of "see"in your head...you've assembled the materials, got it sort of together...

You add water.

Then, you walk in the room one day, look at it and- you simply HATE it.

Like, you're done with it. Like, no re-hab on the design. No "tweaking" of the wood or whatever...You're just over the thing. Ever felt that?

What do you do?

Well, I had this idea for a nano tank I while back. It seemed good in my head...I had it up for a nanosecond.

I thought that the tank would be a sort of "blank canvas" for an idea I had...I liked the idea, in principle.

But I didn't see a way forward with this one. I even took the extraordinary step of removing one element of the tank (the wood) altogether, in the hope of perhaps just doing my "leaf only scape V3.0"- but I wasn't feeling it.

Nope.

A stillborn idea. A tank not capable of evolving to anything that interested me at this time.

So...I killed it.

Yeah, made away with it. Shut it down. Terminated it...

Whatever you want to call it.

That's really a kind of extraordinary step for me. I mean, I'm sort of the eternal optimist. I try to make almost everything work if I can...

Not this time, however.

I killed it.

It was super "growthful" for me.

Because I had the courage to stop it.

What made me do it?

I think it centered around two things that I simply can't handle in aquariums anymore.

Don't laugh:

1) I absolutely can't stand aquariums which don't have some sort of background- be it opaque window tint, photo paper, or paint. This tank had no background. You could see the window behind it, and the trees outside on the street, and...yeah.

2) I disdain seeing filters or other equipment in my freshwater aquariums. Like, I hate it more than you can ever even imagine. Now, in reef tanks- oddly- seeing a pump here and there doesn't bother me. I have no idea why...guess to me that's a part of the "aesthetic" in some weird way...

Like, I hate seeing filters and stuff. Its only in recent years that I've been able to tolerate seeing filter returns in my all-in-one tanks...and just barely. Now, this nano had a little hang-on-the-back outside power filter...Which I not only saw from the top, but from behind...because-you got it- I didn't have a goddam background on the tank, yes.

I mean, am I that much of a primadonna that I can't handle that? I mean, maybe, but I like to think of it as a situation where I have simply developed an aesthetic sense that just can't tolerate some stuff anymore. I have good ideas, and then I get to the equipment...and it sort of "stifles" them a bit at times.

This is weird.

But it's a very honest reason...I mean, this stuff bothers me!

And I think there is a really good lesson there:

Do stuff that doesn't bother you.

Or,

Find ways to do things that bother you in way that they won't.

Sometimes- often- that involves compromises.

Ditch really bad ideas…quickly.

Yup, kind of like the reputed Facebook corporate mantra of “move fast and break things”, I think it’s time we all let stuff go that doesn’t work. Life it too short. I am not saying to disregard patience (Lord knows, I’ve written a ton about that over the past few years right in this forum).

All I’m saying is that you need to let go of ideas that simply aren’t working out, taxing time, energy, money, space, and “mind power.” Better to have tried and failed than not to have tried at all…but better to let something that was failing die a quick death than to have it function as a “black hole” of your hobby energy (and budget!). Harsh words coming from me, but they’re true. If it doesn’t work- Kill it.

KILL IT!

(It didn't work. Move on. Next...)

Seek advice and counsel from other hobbyists if you must, but don’t take anyone’s word as THE ultimate. Because the reality is, there is plenty to learn in this hobby from a lot of people. And from yourself, as well! There are people out there in Fish Keeping Land doing stuff you never even heard of, and maybe they are having great results.

Does that mean you should listen to everything they say and try to replicate their efforts to the last detail, or embrace all of their philosophies? Of course not. No way. Take everything- from everyone in this hobby- with a grain of salt. Learn to evaluate aquarium keeping strategies in the context of “Will this work for ME?” Far better than to just blindly follow ANYONE.

Do you.

One of the things I've found it hardest to do as an aquarist who owns a company in recent years is to speed up the creation of new aquariums. The reality is that my whole aquarium "career" has been geared towards being able to s-l-o-w d-o-w-n and establish aquariums over long periods of time, allowing them to evolve.

This doesn't always square well with the "get more ideas out there YESTERDAY!" mindset that you seem to need to have in today's social media fueled hobby. I watch some YouTubers just crashing through every barrier in a frantic pace to get to the next project as quickly as possible. It's like, "Can't stand still for a second, or..!"

Or what, exactly?

Do "creators" really think that they're going to lose a substantial percentage of their followers just because it's Wednesday, they're still stabilizing their African river tank, and they didn't get to the 240-gallon Pirahna tank just yet?

Really?

I mean, it's kind of crazy. However, I DO understand the mindset behind it to a certain extent.

Yeah. Like, when you see part of your responsibility being to inspire others through your ideas and work, you want to show as much as possible, as frequently as possible. But, does that mean constantly creating some new setup to follow whatever the hot thing is at the moment? It gets ridiculous after a while ("If it's Thursday, it's time for the Rainbowfish biotope tank...Or was it the macro algae tank? Or maybe it's the Swordtail tank...")

Again, I suppose part of me understands.

"Creators" feel that they need to...create. But why does it always have to be a new tank? Why not produce content focusing on evolving and perfecting the existing tanks? Why not discuss the current challenges, status, and progress on the tank you just started? Some creators do this, and it's great content! Now, I understand, some professionals can show new tanks every week because that's what they do!

But hobbyists shouldn't feel that there is some "pressure" to constantly feature new stuff. Because there isn't. But the pressure is there, sure.

I could have easily succumbed to this perceived urgent "need" to crank out a rapid succession of tanks. After all, it's been almost 18 months since I was able to have a meaningful home aquarium, I've got a ton of ideas, my wife is all for it, and I feel good about all of the projects I've got planned...Full speed ahead, right?

Where's the fun in THAT?

Yeah, I've purposely kept myself on a "hobbyist footing", and am trying to simply play with each tank and work on the challenges that arise with them in a manageable, logical pace. I want to fully ENJOY each one for what it is. And I've been sharing what's been going on with them. Maybe it's not as exciting as me setting up two more cool new tanks, but it feels much more "honest" to me.

And again, you don't HAVE to kill ideas when they're not working out. I've ridden out plenty that eventually turned in to something I loved.

Perhaps this scenario sounds familiar to you:

You set up a tank that started with the best of intentions: It's a really cool idea. You had the right materials to do the job. You even used the correct aquarium for the work. You set the tank up- exactly how you envisioned it..

Yet, after a few weeks of operation, perhaps the tank just isn't where you want it. You find yourself "nitpicking" a lot of stuff about it. Maybe you're not seeing the aquarium reach a state where you expected it would be at this point...

Been there?

I'll be that you have.

I've had this sort of thing happen many times over my aquarium "career." What do I do when I run into a situation like this with one of my tanks?

You'd think I'd be inclined to just kill it. To tear it down, start over, or do something else.

You'd think that.

Instead, I stay calm.

It's seriously cool and quiet in my head when it comes to this stuff. I'm usually not going to do anything about it...except to wait. I've been down this road hundreds of times. I know enough to understand a fundamental truth about botanical-method aquariums:

The way the tank is looking right now is NOT how it will look in a few weeks, or months.

I play a really long game. One which acknowledges that the fact that our botanical-method aquariums evolve over very long periods fo time, not reaching the state that we perhaps envisioned for many months. My actions reflect this mindset. Unless there is some major emergency (which I have yet to encounter, btw), about the only thing that I might do is to add a few more botanicals.

Just sort of "evolving" the aquarium a bit; making up for stuff that might break down.

Minor, small moves, if any.

All the while, I'm keeping in mind that the system will change on its own without any intervention on my part. It will "get where it's going" on its own time. Adding a few botanicals or leaves along the way is simply what you do to keep the process going. And it's extremely analogous to what happens in Nature, as new materials fall into waterways throughout the year, while existing materials are carried off by currents or decompose completely.

Yeah, just like Nature.

The processes of evolution, change and disruption which occur in natural aquatic habitats- and in our aquariums- are important on many levels. They encourage ecological diversity, create new niches, and revitalize the biome. Changes can be viewed as frightening, damaging events...Or, we can consider them necessary processes which contribute to the very survival of aquatic ecosystems.

Change and variation is inevitable and important in the hobby. Being open minded about things is vital.

Think about that the next time you hesitate to experiment with that new idea, or play a hunch that you might have. Remember that there is always a bit of discomfort, trepidation, and risk when you make changes or conduct bold experiments.

Goes with the territory, really.

However, once you get out of that comfort zone, you're really living...and the fear will give way to exhilaration and maybe even triumph! Because in the aquarium hobby, the bleeding edge is when you're constantly changing, and patiently evolving.

Stay Brave. Stay persistent. Stay curious. Stay thoughtful. Stay creative...

And Stay Wet.

Tanks...a LOT!

(Oh, before we begin today's piece, let me preface it by warning you that it contains the usual compliment of profanity. obnoxious sentiments, occasional backhanded comments, and a lot of "opinion" which some may find utterly offensive. I feel you...but you have been warned and you can go back to lower stakes media like Tik Tok or whatever and get your" rah-rah drivel quotient" there, okay? Scott)

Like every hobbyist, I spend a lot of time dreaming and scheming about new aquarium setups. And one of the beautiful things about this kind of "imagineering" ( to coin a Disney term) is that I can venture into all sorts of areas in the hobby- including ones which I might have relatively little- or even no- experience with. You know, stuff you wouldn't expect from "Mr. Tinted Water Guy", like Mbuna tanks, Stiphodon goby habitats, livebearer tanks ,etc.

The beauty of doing these mental "feasibility studies" is that I can imagine, design, "shop" and scheme without spending a dime, spilling a drop of water, or sourcing the equipment I need to use!

Yet, I get really distracted easily, when it comes to aquarium stuff!

The goal is not to get into a loop of "analysis paralysis" and never make a move simply because I'm "still planning..." Yeah. I've seen guys do that and the tank sits empty and collects dust and cobwebs while they are "contemplating."

Yuck.

You see, like many of you, my imagination, appetite, and enthusiasm are often larger than my ability, time, or means to get the job done. I've concluded that to do all of my crazy concept tanks, I'd probably need like 17 aquariums of all shapes and sizes, many with technologies and components that would carry a breathtaking price tag- if they exist at all...

And, this is AFTER I've eliminated some of the early front runners, like the intertidal Pipefish Mangrove tank, the Amazonian waterfall tank, the monospecific Acropora microcaldos tank, the "Nothobranchius Temporal Pool" concept tank (ask me about the "mud hole" idea I've been playing with sometime), and others that are earmarked for some "indefinite future date...."

So, I kind of have this personal thought about "ideas."

They're worthless.

Really.

Okay, that sounded a bit harsh. Let me clarify a bt.

I mean, if you're not going to do anything with them, they're sort of just "nice things" to have- maybe inspiring-but you need to act on them or they are just...theoretical, right?

Worthless.

I don't want to keep "theoretical" tanks.

And, I realize that there are limitations that we all have- Space, time, money, etc.- and that these temper many of ideas from being executed. I suppose that is part of the reason why I've changed my thinking about so-called "nano"-sized tanks over the past few years. Because their smaller size and ease of use helps you rapidly iterate from idea to completed system quickly and easily! I've had a lot of fun with them lately.

One of the best things about my business is getting to help fuel the dreams of other hobbyists. It gives me great pleasure to see you guys enjoying the hobby, and motivates me to do more.

And of course, when it comes time to do my own tank, I have to weed through all of these crazy ideas- some of which challenge me in ways I hadn't even considered. Some are just fun to play with.

Others launch me and Tannin into entirely new directions- those are the best ideas!

Okay, so maybe not ALL ideas are worthless.

What are some of my personal tank ideas that are going through my mind lately?

Well, here are a few:

An "old fashioned" Guppy Aquairum

Yeah, seriously. Lately, I am having this flashback to my childhood, when I spent hours and hours looking at my dad's guppy tanks (he was really into 'em). I'm sort of obsessed with the whole idea of clear water, "number 3 grade" aquairum gravel, and water sprite. Oh, and some cool guppies...Likely a mix of strains and color varieties that would cause any serious guppy breeder to run screaming into the night!

I have no idea why I'm longing for this. No "wild Guppy biotope" bullshit...No "high concept Guppy Tank" crap...Just a simple tank filled with a jungle of Water Sprite, a couple of pieces of petrified wood, gravel, and guppies. Total throwback tank! Maybe a modern twist would be to include some planted aquarium substrate underneath the essentially sterile gravel, but that's it.

Yeah, clear water, crisp white 7000k LED light, and all! I love the idea. Although I admittedly pause and wonder how long I could enjoy this tank before I'd become bored with it?

Wild Livebearer Aquairum

Okay, this is sort of sounding closer to the type of thing you might expect from me. Perhaps a tank set up to replicate some of the South American habitats in which you'd find wild livebearers...Maybe a mixed bed substrate, with sand, silt, and some gravel-sized materials, a few small stones, and perhaps some plants like Sagittariusaor whatever. Not an exact biotope (F that!)- but more of my "biotope inspired" approach.

What livebearers? Well, Maybe Swordtails or perhaps Endless (although I've done an Endler's tank recently and it got boring after a while...). What about OG black Mollies, a little bit of salt ( I am a reefer, for goodness sakes), and a few tolerant plants? I dunno. That could be cool for a while, I suppose.

Maybe even something more unusual, like Poecilia picta, or some sort of other less common ones, like the "Tiger Teddy" (Neoheterandria elegant) ; yeah, WTF kind of common name is THAT? Though it's tiny and can tolerate soft water better than most livebearers! Or maybe, the "Porthole Livebearer" (Pocilopsus gracious)- about as dull-looking a fish as you can imagine (part of its appeal to me!)?

Mbuna..Just because they're colorful and live around rocks

Yeah, okay. This idea has been floating around in my head for a long time. We're not talking about "Shellies" (shell dwelling cichlids from the rift lake down the road, so to speak)- even though I'm obsessed with their habitat and all, the fish themselves are pretty boring looking, if you ask me. Faint grey stripes on a silver fish in a tank with white sand, grey rocks, and tan shells is too monochromatic even for me.

So yeah, smaller Malawi species like Pseudotropheus saulosi, Pseudotropheus sp. "acei", and the much-loved Labidochromis caeruleus would be nice. I'm thinking a group of a few males of each, to get maximum color and minimal aggression. Maybe like 4 or 5 male specimens of those three species in a 50 gallon tank.

Crowded but not "overly crowded?"

I'd just water change the shit out of it every week, and employ some reef gear (like AI Nero or EcoMarine Vortech electronic pumps) for water movement? We have naturally hard, alkaline water here in Los Angeles, so keeping a high pH would be a snap! I've had friends do this type of tank, and it was gorgeous. Really colorful fishes over a background of aragonite sand and grayish rocks.

Yeah, I can get behind THIS idea!

Marine Macroalgae tank with Mandarin Dragonets and Pipefishes?

Oh, I've loved that idea for decades...Did it in 2005 and loved it. Played with it again in 2021. Spoke about Macroalage and Seagrasses at MACNA way back in 2009... Was probably a bit too early. Unfortunately, the idea of sterile-looking, "high concept macrolagae tanks" (a la Nature Aquairum "style" b.s.) is becoming "trendy" in that vomit-inducing way that I hate...so Fuck this idea for a while, lol. I think I'll wait to play with this idea again until after people start ignoring these kinds of tanks again.

I know, my attitude sucks. It's just that I hate doing stuff and sharing it and then having people tell me, "Oh, did you see ________ tanks on Instagram? They're so incredible!" (You know, the drivel-esque, polar opposite interpretation of what I'd do) "You should try one like HIM!" (at which time I most definitely want to vomit. What, my rather eco diverse, natural-looking version isn't any good? LOL

Regardless, I still have a long-running healthy obsession with seagrasses and macroalage. I love the calcareous macroalage, Halimeda; perhaps the least "trendy" of the macroalage in this new dumbed-down "high concept artistic macroalage tank renaissance" which we find ourselves in.

Maybe it's time to do another off-trend tank to piss off everyone? Yeah, maybe. I know that a few fellow old crusty, treacherous reefers like me might appreciate me dropping a tank like that to shit on this "scene" before it gets to be too awful. to tolerate

God, I've become a complete asshole in recent years!

Oh, and since I'm at it: If you ever put your nano tank on a little turntable, please don't ever talk to me again. That's the freaking stupidest thing I've EVER seen in aquaruum keeping, hands down.

Oh, there IS a guy doing it right in the macrolagae space . A guy in Japan who goes by the handle "-ichistarium". His work is amazing. Oh, and our friends inland_reef and afishionado are positively crushing it with their own natural interpretations of macroalage/mangrove habitats. Check them out and give them the love they deserve!

Okay, deep breath....

Rocks...just, like...rocks..

Not sure what it is...maybe it's the reefer in me again... I have a big desire to do a tank with just rocks. No plants, wood, leaves. Nada. Just rock. What's the reason for this newfound fascination for rocks? Like, perhaps it's the angst built up in me after 18 years of playing with just leaves and twigs and botanicals and sediments that makes the idea of a tank with just rocks fascinating to me again.

And what kinds of fishes would I put in a "rock tank?"

Well, sure, Mbuna for one. But there are other fishes, like gobies, Danios, perhaps some loaches and barbs? For that matter, Swordtails or some kind of Geophagus or Central American cichlids? A tank meant to replicate some version of a rocky pool, stream, or even river could be super cool, and just different for me. Maybe I could toss a few token branches in there? Maybe not.

Yeah, Ditched selling rocks here back in 2020, citing the (fact) that rocks are generally not associated with the types of habitats that we play with here. Their reality, however, is that when I started Tannin. in 2015, I wanted to embrace "natural aquariums", and that concept can embrace multiple genres and multiple materials...including rocks, right?

Yeah.

Danios...Again.

I've been talking about this idea for years. A tank created to replicate the wild habitat of the Zebra Danio. Yes, the humble fish of my childhood. Yet, one which I feel gets no respect. Now, I'll be the first to admit that dedicating an entire aquarium to this little fish is a bit "different", right? Yet, there is something about the idea that find super compelling nonetheless. a conventional square or rectangle-shaped tank is not what would really work here. Rather, I feel that a long, low aquarium would be best. To really help facilitate their swimming and their activities, such a tank would really work well.

Yet, could I devote and entire 50 gallon tank just to them? I'll be honest, I'm not sure. it might be a bit of a challenge mentally, lol. Part of the charm of this fish is its fast swimming and schooling behavior, and to facilitate that, a long, shallow tank would be best, IMHO. Can you imagine a 4 or 5 foot long, 16" (40 cm) high tank for these fishes? Maybe nice and wide. Yeah! A bottom of mixed sediments and gravels, some smooth stones, perhaps some Rice plants or Acorus..perhaps a scattering of random leaves and twigs..That would be a simple and cool display.

A substrate-only display?

Imagine a tank which has absolutely no rock, no plants, or no driftwood. Just a bunch of sand or other substrate. Perhaps an interesting, mixed-grade substrate...but only substrate nonetheless! I've done leaf litter only, botanicals-only, and twigs-only substrates before...but only sand or other substrate materials? Not yet.

Talk about "negative space!" This would require a very focused, mentally-shifted (or "twisted"), highly dedicated aquarist to pull it off. I mean, we're talking about the only "relief" in the tank would come from the fishes themselves. The key would be coming up with an interesting mix of materials and grades and colors to really make it work. Oh, and a more shallow, longer tank again, IMHO.

What kinds of fishes would you keep?

Well, I would imagine that you could keep bottom-dwelling fishes like Corydoras, or gobies and bennies...perhaps even Eels and loaches. I suppose some schooling fishes would work, too> Would you go with relatively dull, monochromatic ones, or super colorful ones? I wonder how the fishes would react to being "out in the open" all the time. Would this be "cruel?" Would it result in a more "protective" swimming behavior like tight shoaling?

Or, would this facilitate natural behaviors among fishes which swim in open waters. I wonder, though, are there fishes which preferentially inhabit open water areas over vast stretches sand? There must be, right? If so, they're likely fishes that are either really fast swimmers, or predators, I would suppose.

Or, am I simply overthinking this? I mean, it's essentially like a bare bottom breeding tank; an idea that's been used in the trade for decades. It's just that this is a permanent, allegedly decorative setup, right?

The fishes would absolutely be the focus here.

And there are those geographic replications, too.

When I contemplate "turning east" to Africa, I get pretty damn excited at the possibilities. Of course, The blackwater habitats and fishes of Southeast Asia beckon. However, with the setups I've done with brackish, I'm already "riffing" on those locales.

And so part of my mindset tells me, "Well, dude, you're sort of already there...just stick to your South American thing...You love it. It's you..."

...And then my mind flashes to Kribs. The first cichlid I ever bred..when I was like 13! In a 2.5 gallon tank, no less!

Never forgot that...

And of course, the African characins...

...and the idea of killies in a community-type setting dances through my mind.

And those Ctenopoma. Always the Ctenopoma...

And yet, the lure of the Amazon is almost too great to resist. Like, it's just the freshwater region I identify with the most. Everything about it.

It just "works" for me, I guess..

We need to act on our crazy (and not-so crazy) ideas whenever we can. Because it's hard to allow one of your ideas to shrivel up and die without ever being executed because you were afraid of criticism.

For those of you taking on your new ideas, and pushing out into new territories- new frontiers:

Move forward. Bravely.

Take comfort in the fact that you are trying. Take comfort in the fact that your work may inspire others...and in it's own little way, perhaps change the aquarium hobby.

You're not foolish.

And your ideas aren't, either.

Everything we do helps advance the state of the art in the aquarium hobby. Each new tank- no matter how awesome we or the world think it is-gives us experience, ideas, and inspiration to do other tanks that perhaps bring us closer to the idea that we had in mind. And it can influence other hobbyists to do the same.

I can't tell you how many times I've done a "thing" or "things" which were based on some idea, some inspiration, or some thought that I had about how to execute an aquarium, which may not have gotten me "there" right from the start, but taught me all sorts of things along the way too ultimately arriving where I wanted to be.

It often starts with a concept..an idea.

...Until it gradually emerges into a more "polished" configuration.

.

Now, often an idea will start based on something we see in Nature. Perhaps an element of a habitat that we like. Perhaps, it will dovetail with some sort of hypothesis we have, and lead to other executions to prove out the concept.

Often, it's simply a way to see if we can work out a concept. A way to push things forward.

One of the things I enjoy most about Tannin- is to look at things the way they are in the hobby-the way they've been practiced for generations- and to question WHY.

Not for the sake of being an arrogant jerk- but in the spirit of questioning why we do stuff the way we do. Is it because it's the BEST way? Or is it because that's what worked well with the prevailing skill set/knowledge/equipment available at the time the idea was presented to the hobby, and we've just accepted it as "the way" ever since, even though all of the "back story" which lead to this unwavering acceptance of the practice has long since changed?

A practice or idea that may have been appropriate and optimum 30 years ago may be woefully outdated now. I mean, it still "works", but there are better ways now...

Accepting ideas, practices, and techniques in the hobby "...just because we've done it that way forever" is, in my opinion, a way to stagnate.

And in all fairness, an admonition to change things "just because" is equally as detrimental. Rather, it's better to simply look honestly and boldly at how/why we do something, and ask ourselves, "Is this really the best way? Is it really necessary?"

Is it a practice we should keep embracing?

Or is it time to "rewrite the code?"

I think so.

Simple thought. Powerful implications.

Every observation we make on all sorts of these aspects of the botanical-method aquarium s helps us move the needle a bit. With a growing number of hobbyists experimenting with botanical materials in all sorts of aquariums and enjoying improving fish health, spawning, etc., it's getting more and more difficult to call it a "novelty" or "fad."

I mean, Nature isn't exactly a "fad" or trend-follower, right? She's been doing this stuff for eons. We're just sort of "catching up"- and beginning to study, contemplate, and appreciate what happens when form meets function in the aquarium.

And that's pretty exciting, isn't it?

Stay engaged. Stay curious. Stay dedicated. Stay observant. Stay open-minded...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Where the magic lies...

The botanical method aquarium niche is a bit weird, isn't it? Collectively, companies in our space tend to speculate a lot.

We make claims.

And we make recommendations..

And at best, they’re subjective guesses. Based upon our personal experince and perhaps the experiences of others.

Yet, wherever you turn in the botanical method aquarium world, speculation and generalizations are, well- rampant. How much tannin or other compounds are in a given botanical is, without very specific bioassays and highly specialized equipment- simply a guess on our part.

There is absolutely no proof or quantification of these assertions that is grounded in hard facts or rigorous, scientific research. I think about it a lot..For us to make recommendations based on concentrations of various compounds in a given botanical is simply irresponsible and not grounded in fact.

There is a lot of speculation. So-called "experts" in our area of specialization have, in all likelihood, done little beyond use the materials avialbel to us in aquairums. I'm not aware of anyone in our niche who runs a lab, or has performed disciplined scientific analysis on any of the materials that we as a hobby use every day.

This is not an "indictment" or secret reveal about our industry...it's just the way things are.

One of the things that we assert the most is "how much tannins" are in a given material. Okay...What is this based upon?

Generally, it's based upon the admittedly superficial observations that we make as hobbyists and "power users" of botanical materials. There are not awhole lot of other, more insightful observations that we CAN make, right?

Sure, we could tell you that, based upon our experience, a given wood type or seed pod will color the water a darker color than another.. but what does that mean, really?

Not that much.

I mean color of the water is absolutely not an indication of anything- other than the fact that tint producing types of tannins are present. It doesn’t tell you what the pH, dKH, or TDS of the water.. let alone, how much of what tannins are present…

Now, sure, it’s arguably correct that “tannins” are present in many botanical materials. However, the degree to which the tannins present in a given botanical or leaf can influence water chemistry is really speculative. Quite honestly, other than staining the water a distinctive brown color, it’s actually not entirely known by science what other influences that specific tannins impart to water.

So, to be quite honest, when we make general statements like “contains a lot of tannins” or “can lower pH”, many times we’re simply “spitballing…” Guessing. Assuming.

Now, don't get me wrong. I'm not trying to trash the many responsible, experienced vendors in our space. I am, however, attempting to make the point that a large part of what we assert about the materials we work with and sell is, well- speculative.

We make claims.

And we make recommendations..

I think the main thing which keeps the idea from really developing more in the hobby- knowing exactly how much of what to add to our tanks, specifically to achieve "x" effect- is that we as hobbyists simply don't have the means to test for many of the compounds which may affect the aquarium habitat.

At this point, it's really as much of an "art" as it is a "science", and more superficial observation- at least in our aquariums- is probably almost ("almost...") as useful as laboratory testing is in the wild. Even simply observing the effects upon our fishes caused by environmental changes, etc. is useful to some extent.

At least at the present time, we're largely limited to making these sort of "superficial" observations about stuff like the color a specific botanical can impart into the water, etc. It's a good start, I suppose.

Of course, not everything we can gain from this is superficial...some botanical materials actually do have scientifically confirmed impacts on the aquarium environment.

In the case of catappa leaves, for example, we can at least infer that there are some substances (flavonoids, like kaempferol and quercetin, a number of tannins, like punicalin and punicalagin, as well as a suite of saponins and phytosterols) imparted into the water from the leaves- which do have scientifically documented affects on fish health and vitality.

So, there's that.

The one area that we are not speculating or guessing is the ecology part. How botanical materials interact with the aquatic environment to form an ecosystem of organisms. And the most fundamental, most important "driver" of the whole thing is the process of decomposition.

Decomposition is how Nature processes botanical materials for use by the greater aquatic ecosystem. It's the first part of the recycling of nutrients that were used by the plant from which the botanical material came from. When a botanical decays, it is broken down and converted into more simple organic forms, which become food for all kinds of organisms at the base of the ecosystem.

In aquatic ecosystems, much of the initial breakdown of botanical materials is conducted by detritivores- specifically, fishes, aquatic insects and invertebrates, which serve to begin the process by feeding upon the tissues of the seed pod or leaf, while other species utilize the "waste products" which are produced during this process for their nutrition.

In these habitats, such as streams and flooded forests, a variety of species work in tandem with each other, with various organisms carrying out different stages of the decomposition process.

And it all is broken down into three distinct phases identified by ecologists.

It goes something like this:

A leaf falls into the water.

After it's submerged, some of the "solutes" (substances which dissolve in liquids- in this instance, sugars, carbohydrates, tannins, etc.) in the leaf tissues rather quickly. Interestingly, this "leaching stage" is known by science to be more of an artifact of lab work (or, in our case, aquarium work!) which utilizes dried leaves, as opposed to fresh ones.